User login

Pencil-core Granuloma Forming 62 Years After Initial Injury

To the Editor:

Trauma from a pencil tip can sometimes result in a fragment of lead being left embedded within the skin. Pencil lead is composed of 66% graphite carbon, 26% aluminum silicate, and 8% paraffin.1,2 While the toxicity of these individual elements is low, paraffin can cause nonallergic foreign-body reactions, aluminum silicate can induce epithelioid granulomatous reactions, and graphite has been reported to cause chronic granulomatous reactions in the lungs of those who work with graphite.2 Penetrating trauma with a pencil can result in the formation of a cutaneous granulomatous reaction that can sometimes occur years to decades after the initial injury.3,4 Several cases of pencil-core granulomas have been published, with lag times between the initial trauma and lesion growth as long as 58 years.1-10 The pencil-core granuloma may simulate malignant melanoma, as it presents clinically as a growing, darkly pigmented lesion, thus prompting biopsy. We present a case of a pencil-core granuloma that began to grow 62 years after the initial trauma.

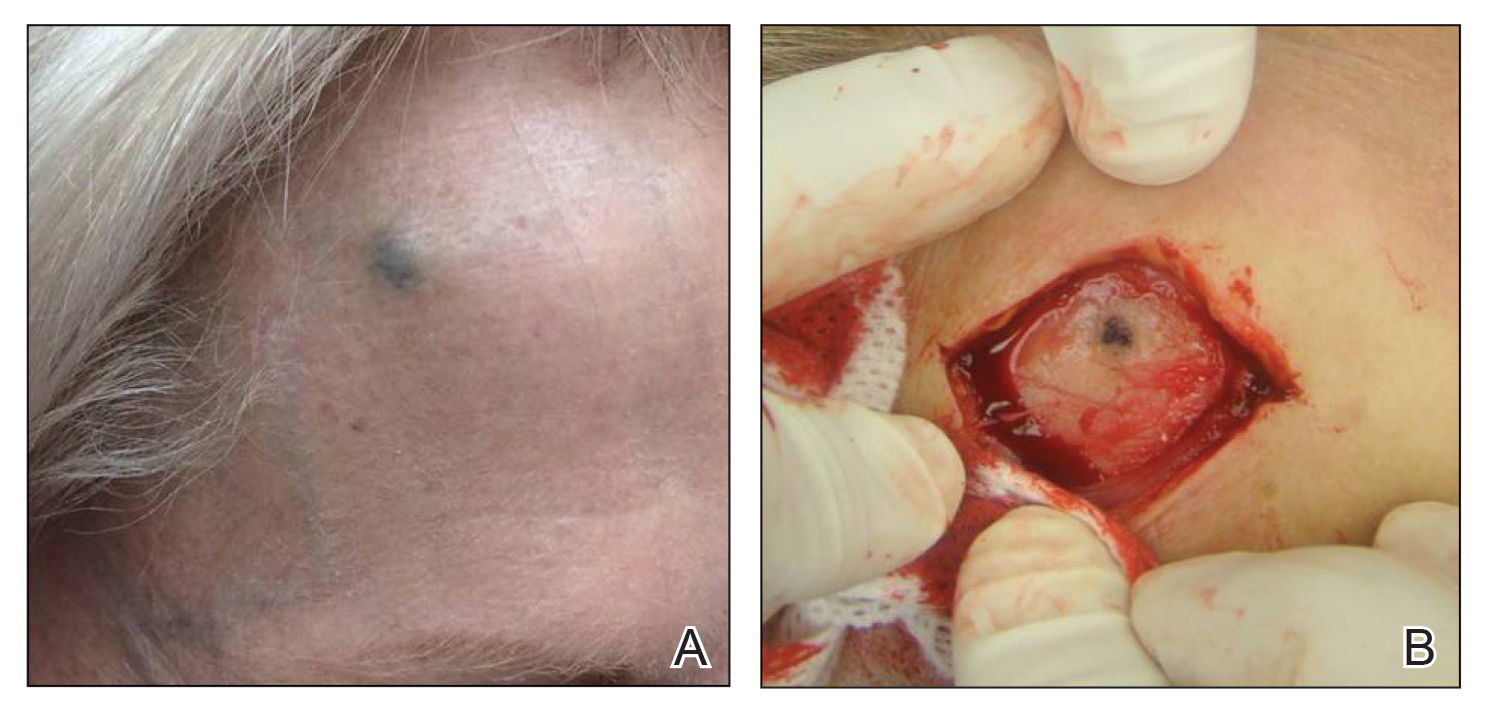

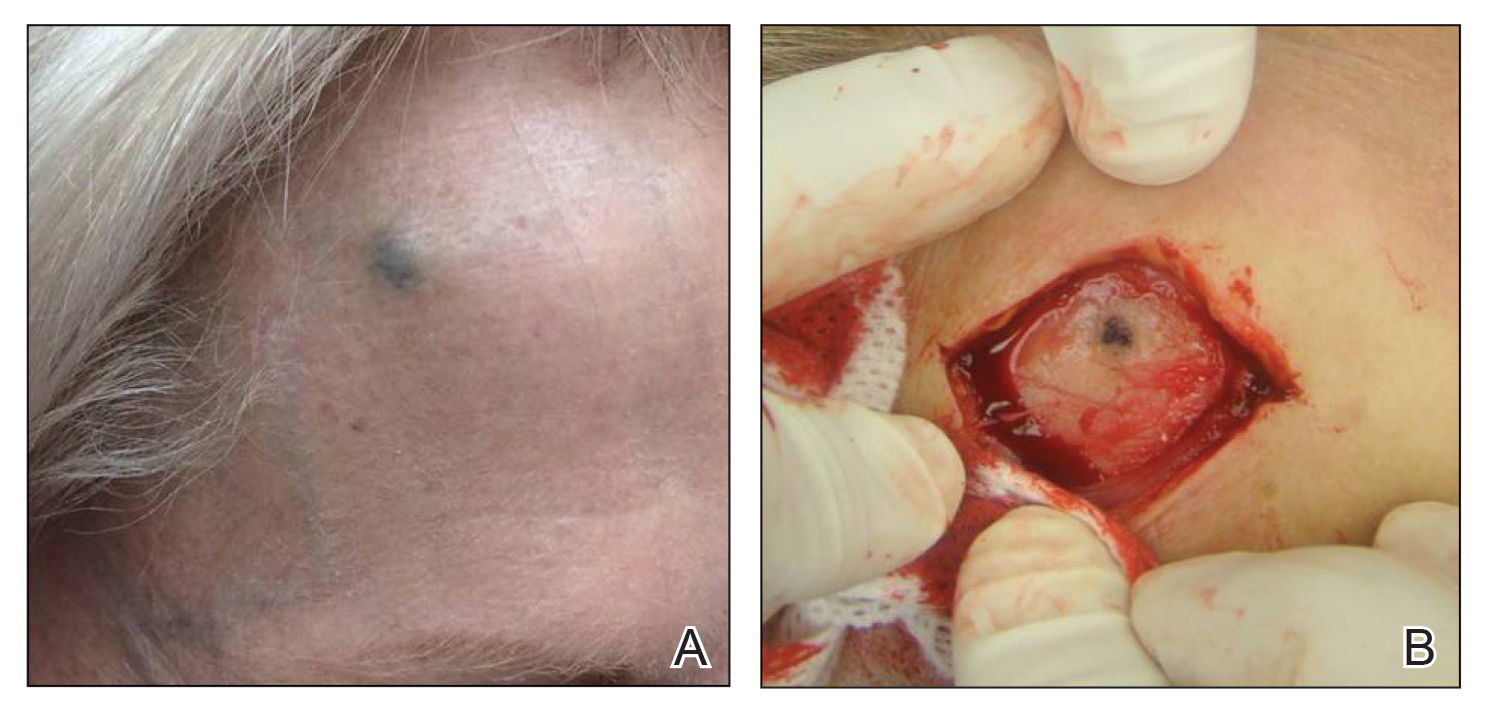

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a dark nodule on the forehead. The lesion had been present since the age of 10 years, reportedly from an accidental stabbing with a pencil. The lesion had been flat, stable, and asymptomatic since the trauma occurred; however, the patient reported that approximately 9 months prior to presentation, it had started growing and became painful. Physical examination revealed a 1.0-cm, round, bluish-black nodule on the right superior forehead (Figure 1A). No satellite lesions or local lymphadenopathy were noted on general examination.

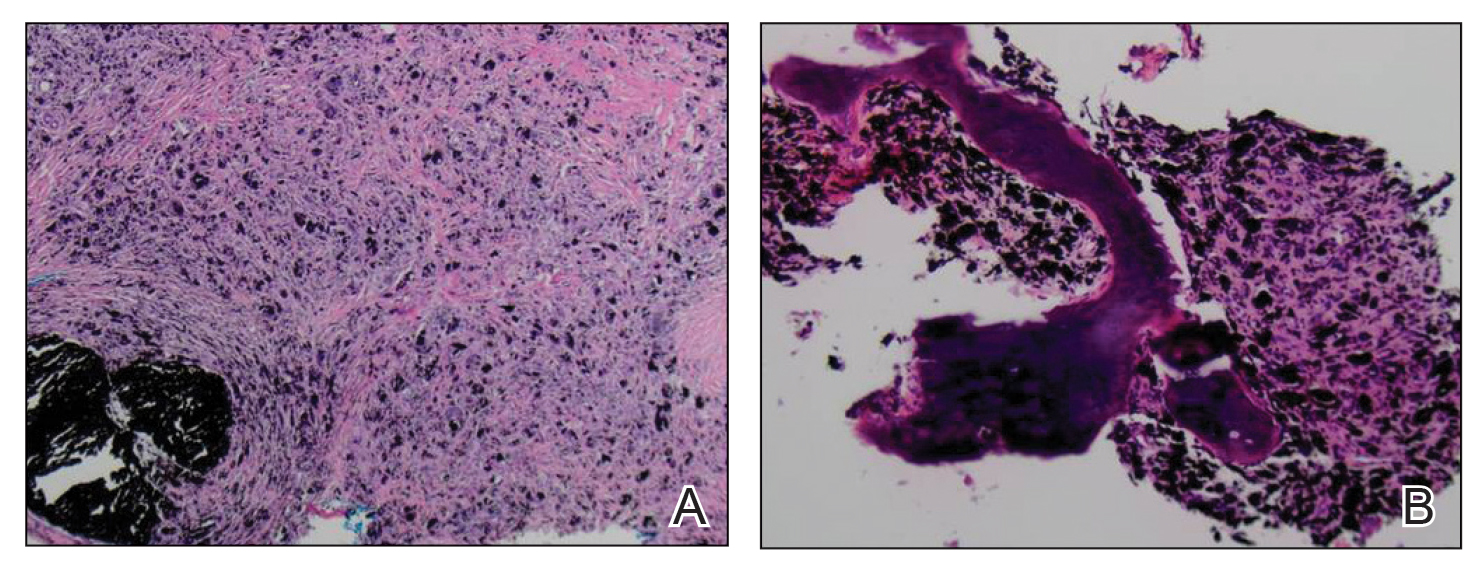

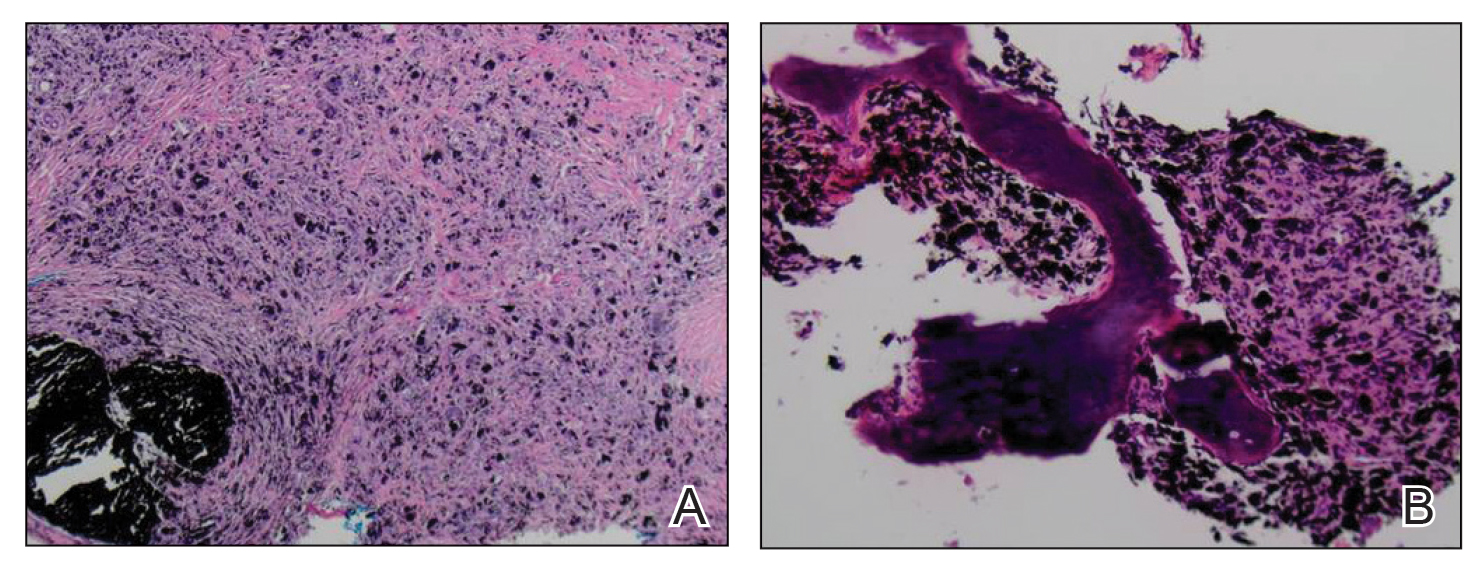

An elliptical excision of the lesion with 1-cm margins revealed a bluish-black mass extending through the dermis, through the frontalis muscle, and into the periosteum and frontal bone (Figure 1B). A No. 15 blade was then used to remove the remaining pigment from the outer table of the frontal bone. Histopathologic findings demonstrated a sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis associated with abundant, nonpolarizable, black, granular pigment consistent with carbon tattoo. This foreign material was readily identifiable in large extracellular deposits and also within histiocytes, including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2). Immunostaining for MART-1 and SOX-10 antigens failed to demonstrate a melanocytic proliferation. These findings were consistent with a sarcoidal foreign-body granulomatous reaction to carbon tattoo following traumatic graphite implantation.

Granulomatous reactions to carbon tattoo may be sarcoidal (foreign-body granulomatous dermatitis), palisading, or rarely tuberculoid (caseating). Sarcoidal granulomatous tattoo reactions may occur in patients with sarcoidosis due to koebnerization, and histology alone is not discriminatory; however, in our patient, the absence of underlying sarcoidosis or clinical or histologic findings of sarcoidosis outside of the site of the pencil-core granuloma excluded that possibility.11 Pencil-core granulomas are characterized by a delayed foreign-body reaction to retained fragments of lead often years following a penetrating trauma with a pencil. Previous reports have described various lag times from injury to lesion growth of up to 58 years.1-10 Our patient claimed to have noticed the lesion growing and becoming painful only after a 62-year lag time following the initial trauma. To our knowledge, this is the longest lag time between the initial pencil injury and induction of the foreign-body reaction reported in the literature. Clinically, the lesion appeared and behaved very similar to a melanoma, prompting further treatment and evaluation.

It has been suggested that the lag period between the initial trauma and the rapid growth of the lesion may correspond to the amount of time required for the breakdown of the pencil lead to a critical size followed by the dispersal of those particles within the interstitium, where they can induce a granulomatous reaction.1,2,9 One case described a patient who reported that the growth and clinical change of the pencil-core granuloma only started when the patient accidentally hit the area where the trauma had occurred 31 years prior.1 This additional trauma may have caused further mechanical breakdown of the lead to set off the tissue reaction. In our case, the patient did not recall any additional trauma to the head prior to the onset of growth of the nodule on the forehead.

Our case indicates that carbon tattoo may be a possible sequela of a penetrating injury from a pencil with retained pencil lead fragments; however, many of these carbon tattoos may remain stable throughout the remainder of the patient’s life.

- Gormley RH, Kovach SJ III, Zhang PJ. Role for trauma in inducing pencil “lead” granuloma in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1074-1075.

- Terasawa N, Kishimoto S, Kibe Y, et al. Graphite foreign body granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:774-776.

- Fukunaga Y, Hashimoto I, Nakanishi H, et al. Pencil-core granuloma of the face: report of two rare cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1235-1237.

- Aswani VH, Kim SL. Fifty-three years after a pencil puncture wound. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:303-305.

- Taylor B, Frumkin A, Pitha JV. Delayed reaction to “lead” pencil simulating melanoma. Cutis. 1988;42:199-201.

- Granick MS, Erickson ER, Solomon MP. Pencil-core granuloma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:136-138.

- Andreano J. Stump the experts. foreign body granuloma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:277, 343.

- Yoshitatsu S, Takagi T. A case of giant pencil-core granuloma. J Dermatol. 2000;27:329-332.

- Hatano Y, Asada Y, Komada S, et al. A case of pencil core granuloma with an unusual temporal profile. Dermatology. 2000;201:151-153.

- Seitz IA, Silva BA, Schechter LS. Unusual sequela from a pencil stab wound reveals a retained graphite foreign body. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:568-570.

- Motaparthi K. Tattoo ink. In: Cockerell CJ, Hall BJ, eds. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Amirsys; 2016: 270.

To the Editor:

Trauma from a pencil tip can sometimes result in a fragment of lead being left embedded within the skin. Pencil lead is composed of 66% graphite carbon, 26% aluminum silicate, and 8% paraffin.1,2 While the toxicity of these individual elements is low, paraffin can cause nonallergic foreign-body reactions, aluminum silicate can induce epithelioid granulomatous reactions, and graphite has been reported to cause chronic granulomatous reactions in the lungs of those who work with graphite.2 Penetrating trauma with a pencil can result in the formation of a cutaneous granulomatous reaction that can sometimes occur years to decades after the initial injury.3,4 Several cases of pencil-core granulomas have been published, with lag times between the initial trauma and lesion growth as long as 58 years.1-10 The pencil-core granuloma may simulate malignant melanoma, as it presents clinically as a growing, darkly pigmented lesion, thus prompting biopsy. We present a case of a pencil-core granuloma that began to grow 62 years after the initial trauma.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a dark nodule on the forehead. The lesion had been present since the age of 10 years, reportedly from an accidental stabbing with a pencil. The lesion had been flat, stable, and asymptomatic since the trauma occurred; however, the patient reported that approximately 9 months prior to presentation, it had started growing and became painful. Physical examination revealed a 1.0-cm, round, bluish-black nodule on the right superior forehead (Figure 1A). No satellite lesions or local lymphadenopathy were noted on general examination.

An elliptical excision of the lesion with 1-cm margins revealed a bluish-black mass extending through the dermis, through the frontalis muscle, and into the periosteum and frontal bone (Figure 1B). A No. 15 blade was then used to remove the remaining pigment from the outer table of the frontal bone. Histopathologic findings demonstrated a sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis associated with abundant, nonpolarizable, black, granular pigment consistent with carbon tattoo. This foreign material was readily identifiable in large extracellular deposits and also within histiocytes, including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2). Immunostaining for MART-1 and SOX-10 antigens failed to demonstrate a melanocytic proliferation. These findings were consistent with a sarcoidal foreign-body granulomatous reaction to carbon tattoo following traumatic graphite implantation.

Granulomatous reactions to carbon tattoo may be sarcoidal (foreign-body granulomatous dermatitis), palisading, or rarely tuberculoid (caseating). Sarcoidal granulomatous tattoo reactions may occur in patients with sarcoidosis due to koebnerization, and histology alone is not discriminatory; however, in our patient, the absence of underlying sarcoidosis or clinical or histologic findings of sarcoidosis outside of the site of the pencil-core granuloma excluded that possibility.11 Pencil-core granulomas are characterized by a delayed foreign-body reaction to retained fragments of lead often years following a penetrating trauma with a pencil. Previous reports have described various lag times from injury to lesion growth of up to 58 years.1-10 Our patient claimed to have noticed the lesion growing and becoming painful only after a 62-year lag time following the initial trauma. To our knowledge, this is the longest lag time between the initial pencil injury and induction of the foreign-body reaction reported in the literature. Clinically, the lesion appeared and behaved very similar to a melanoma, prompting further treatment and evaluation.

It has been suggested that the lag period between the initial trauma and the rapid growth of the lesion may correspond to the amount of time required for the breakdown of the pencil lead to a critical size followed by the dispersal of those particles within the interstitium, where they can induce a granulomatous reaction.1,2,9 One case described a patient who reported that the growth and clinical change of the pencil-core granuloma only started when the patient accidentally hit the area where the trauma had occurred 31 years prior.1 This additional trauma may have caused further mechanical breakdown of the lead to set off the tissue reaction. In our case, the patient did not recall any additional trauma to the head prior to the onset of growth of the nodule on the forehead.

Our case indicates that carbon tattoo may be a possible sequela of a penetrating injury from a pencil with retained pencil lead fragments; however, many of these carbon tattoos may remain stable throughout the remainder of the patient’s life.

To the Editor:

Trauma from a pencil tip can sometimes result in a fragment of lead being left embedded within the skin. Pencil lead is composed of 66% graphite carbon, 26% aluminum silicate, and 8% paraffin.1,2 While the toxicity of these individual elements is low, paraffin can cause nonallergic foreign-body reactions, aluminum silicate can induce epithelioid granulomatous reactions, and graphite has been reported to cause chronic granulomatous reactions in the lungs of those who work with graphite.2 Penetrating trauma with a pencil can result in the formation of a cutaneous granulomatous reaction that can sometimes occur years to decades after the initial injury.3,4 Several cases of pencil-core granulomas have been published, with lag times between the initial trauma and lesion growth as long as 58 years.1-10 The pencil-core granuloma may simulate malignant melanoma, as it presents clinically as a growing, darkly pigmented lesion, thus prompting biopsy. We present a case of a pencil-core granuloma that began to grow 62 years after the initial trauma.

A 72-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a dark nodule on the forehead. The lesion had been present since the age of 10 years, reportedly from an accidental stabbing with a pencil. The lesion had been flat, stable, and asymptomatic since the trauma occurred; however, the patient reported that approximately 9 months prior to presentation, it had started growing and became painful. Physical examination revealed a 1.0-cm, round, bluish-black nodule on the right superior forehead (Figure 1A). No satellite lesions or local lymphadenopathy were noted on general examination.

An elliptical excision of the lesion with 1-cm margins revealed a bluish-black mass extending through the dermis, through the frontalis muscle, and into the periosteum and frontal bone (Figure 1B). A No. 15 blade was then used to remove the remaining pigment from the outer table of the frontal bone. Histopathologic findings demonstrated a sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis associated with abundant, nonpolarizable, black, granular pigment consistent with carbon tattoo. This foreign material was readily identifiable in large extracellular deposits and also within histiocytes, including numerous multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2). Immunostaining for MART-1 and SOX-10 antigens failed to demonstrate a melanocytic proliferation. These findings were consistent with a sarcoidal foreign-body granulomatous reaction to carbon tattoo following traumatic graphite implantation.

Granulomatous reactions to carbon tattoo may be sarcoidal (foreign-body granulomatous dermatitis), palisading, or rarely tuberculoid (caseating). Sarcoidal granulomatous tattoo reactions may occur in patients with sarcoidosis due to koebnerization, and histology alone is not discriminatory; however, in our patient, the absence of underlying sarcoidosis or clinical or histologic findings of sarcoidosis outside of the site of the pencil-core granuloma excluded that possibility.11 Pencil-core granulomas are characterized by a delayed foreign-body reaction to retained fragments of lead often years following a penetrating trauma with a pencil. Previous reports have described various lag times from injury to lesion growth of up to 58 years.1-10 Our patient claimed to have noticed the lesion growing and becoming painful only after a 62-year lag time following the initial trauma. To our knowledge, this is the longest lag time between the initial pencil injury and induction of the foreign-body reaction reported in the literature. Clinically, the lesion appeared and behaved very similar to a melanoma, prompting further treatment and evaluation.

It has been suggested that the lag period between the initial trauma and the rapid growth of the lesion may correspond to the amount of time required for the breakdown of the pencil lead to a critical size followed by the dispersal of those particles within the interstitium, where they can induce a granulomatous reaction.1,2,9 One case described a patient who reported that the growth and clinical change of the pencil-core granuloma only started when the patient accidentally hit the area where the trauma had occurred 31 years prior.1 This additional trauma may have caused further mechanical breakdown of the lead to set off the tissue reaction. In our case, the patient did not recall any additional trauma to the head prior to the onset of growth of the nodule on the forehead.

Our case indicates that carbon tattoo may be a possible sequela of a penetrating injury from a pencil with retained pencil lead fragments; however, many of these carbon tattoos may remain stable throughout the remainder of the patient’s life.

- Gormley RH, Kovach SJ III, Zhang PJ. Role for trauma in inducing pencil “lead” granuloma in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1074-1075.

- Terasawa N, Kishimoto S, Kibe Y, et al. Graphite foreign body granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:774-776.

- Fukunaga Y, Hashimoto I, Nakanishi H, et al. Pencil-core granuloma of the face: report of two rare cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1235-1237.

- Aswani VH, Kim SL. Fifty-three years after a pencil puncture wound. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:303-305.

- Taylor B, Frumkin A, Pitha JV. Delayed reaction to “lead” pencil simulating melanoma. Cutis. 1988;42:199-201.

- Granick MS, Erickson ER, Solomon MP. Pencil-core granuloma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:136-138.

- Andreano J. Stump the experts. foreign body granuloma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:277, 343.

- Yoshitatsu S, Takagi T. A case of giant pencil-core granuloma. J Dermatol. 2000;27:329-332.

- Hatano Y, Asada Y, Komada S, et al. A case of pencil core granuloma with an unusual temporal profile. Dermatology. 2000;201:151-153.

- Seitz IA, Silva BA, Schechter LS. Unusual sequela from a pencil stab wound reveals a retained graphite foreign body. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:568-570.

- Motaparthi K. Tattoo ink. In: Cockerell CJ, Hall BJ, eds. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Amirsys; 2016: 270.

- Gormley RH, Kovach SJ III, Zhang PJ. Role for trauma in inducing pencil “lead” granuloma in the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1074-1075.

- Terasawa N, Kishimoto S, Kibe Y, et al. Graphite foreign body granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:774-776.

- Fukunaga Y, Hashimoto I, Nakanishi H, et al. Pencil-core granuloma of the face: report of two rare cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1235-1237.

- Aswani VH, Kim SL. Fifty-three years after a pencil puncture wound. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:303-305.

- Taylor B, Frumkin A, Pitha JV. Delayed reaction to “lead” pencil simulating melanoma. Cutis. 1988;42:199-201.

- Granick MS, Erickson ER, Solomon MP. Pencil-core granuloma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:136-138.

- Andreano J. Stump the experts. foreign body granuloma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:277, 343.

- Yoshitatsu S, Takagi T. A case of giant pencil-core granuloma. J Dermatol. 2000;27:329-332.

- Hatano Y, Asada Y, Komada S, et al. A case of pencil core granuloma with an unusual temporal profile. Dermatology. 2000;201:151-153.

- Seitz IA, Silva BA, Schechter LS. Unusual sequela from a pencil stab wound reveals a retained graphite foreign body. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:568-570.

- Motaparthi K. Tattoo ink. In: Cockerell CJ, Hall BJ, eds. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Amirsys; 2016: 270.

Practice Points

- Pencil-core granulomas can arise even decades after the lead is embedded in the skin.

- It is important to biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, as pencil-core granulomas can very closely mimic melanomas.

ARFID or reasonable food restriction? The jury is out

Problems with eating and nutrition are common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other gastrointestinal disorders, but clinicians who treat them should be careful not to automatically assume that patients have eating disorders, according to a psychologist who specializes in the psychological and social aspects of chronic digestive diseases.

On the other hand, clinicians must also be aware of the possibility that patients could have a recently identified syndrome cluster called avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), said Tiffany Taft, PsyD, a research associate professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology), medical social sciences, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, Chicago. In a recent study, she and her colleagues defined ARFID as “failure to meet one’s nutritional needs owing to sensory hypersensitivity, lack of interest in eating, or fear of aversive consequences from eating, and is associated with negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.”

ARFID “is a hot topic that we really don’t understand,” she said in an online presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common among patients with IBD, “and nutritional deficiencies themselves can lead to symptoms or side effects that can cause people to eat less,” she said.

“As our vitamin B12 goes down, our cognitive functioning starts to decline, and we might not be making clear decisions in how we’re deciding what to eat, when to eat, if we should be eating at all – just something to think about in your patients who have nutritional deficiencies,” she told the audience.

Other common nutritional deficiencies that can affect eating and food choice among patients with IBD include low folate (B9) levels associated with sore tongue and weight loss, low iron levels leading to nausea and loss of appetite, and zinc deficiency leading to loss of appetite and alterations in taste and/or smell, she said.

Newly recognized in GI

She noted that “ARFID actually originates in the pediatric psychiatric literature, mostly in children with sensory issues [such as] autism spectrum disorder, so this is not a construct that started in digestive disease, but has been adapted and applied to patients with digestive disease, including IBD.”

The DSM-5 lists four criteria for ARFID: significant weight loss, significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral nutrition or oral supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functions.

Helen Burton Murray, PhD, director of the gastrointestinal behavioral health program in the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is familiar with Dr. Taft’s work, said in an interview that inclusion of ARFID in DSM-5 has put a name to a syndrome or symptom cluster that in all likelihood already existed.

However, “the jury is still out about whether, if we do diagnose patients who have digestive diseases with ARFID, that then helps them get to a treatment that improves their relationship with food and improves nutritional issues that may have occurred as a result of a restricted food intake,” she said.

“We don’t know yet if the diagnosis will actually improve things. In our clinical practice, anecdotally, it has, both for patients with IBDs and for patients with other GI conditions, particularly GI functional motility disorders. We’re a little bit more confident about making the diagnosis of ARFID in GI functional motility disorders than we are in IBD of course,” she said.

Screening measures

To get a better sense of the prevalence of ARFID, compared with reasonable responses to digestive diseases, Dr. Taft and colleagues conducted their cross-sectional study in 289 adults with achalasia, celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, or IBD.

They found that 51.3% of the total sample met the diagnostic criteria for ARFID based on the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS), including 75.7 % of patients with achalasia. But Dr. Taft had cautions

“I can tell you, working with achalasia patients, 75% do not have ARFID,” Dr. Taft said.

She noted that the 51.3% of patients with IBD identified by NIAS or the 53% identified by the ARFID+ scale as having ARFID was also highly doubtful.

Dr. Taft and colleagues determined that nearly half of the variance in the NIAS could be accounted for by GI symptoms rather than psychosocial factors, making it less than ideal for use in the clinic or by researchers.

She also noted, however, that she received an email from one of the creators of NIAS, Hana F. Zickgraf, PhD, from the University of South Alabama, Mobile. Dr. Zickgraf agreed that the scale had drawbacks when applied to patients with GI disease, and pointed instead to the Fear of Food Questionnaire, a newly developed 18-item GI disease-specific instrument. Dr. Taft recommended the new questionnaire for research purposes, and expressed hope that a shorter version could be made available for screening patients in clinic.

Dr. Burton Murray said that while the Fear of Food Questionnaire, perhaps in combination with NIAS, has the potential to be a useful screening tool, cutoffs for it have yet to be established.

“At the end of the day, the diagnosis would be made by a clinician who is able to determine whether the life impairment or if the nutritional impairment or restricted food intake are reasonable in the realm of their digestive disease, or could a treatment for ARFID be warranted to help them to make changes to improve their quality of life and nutrition,” she said.

Check biases at the door

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ARFID, clinicians should also consider biases, Dr. Taft said.

“Eating disorders are highly stigmatized and stereotyped diagnoses,” more often attributed to young White women than to either men or to people of racial or ethnic minorities, she said.

Cultural background may contribute to food restrictions, and the risk may increase with age, with 68% of patients with later-onset IBD restricting diets to control the disease. It’s also possible that beliefs about food and “clean and healthy” eating may influence food and eating choices after a patient receives an IBD diagnosis.

Dr. Taft also pointed out that clinicians and patients may have different ideas about what constitutes significant food avoidance. Clinicians may expect patients with IBD to eat despite feeling nauseated, having abdominal pains, or diarrhea, for example, when the same food avoidance might be deemed reasonable in patients with short-term GI infections.

“Severe IBD symptoms are a significant predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and PTSD is hallmarked by avoidance behaviors,” she added.

She emphasized the need for clinicians to ask the right questions of patients to get at the roots of their nutritional deficiency or eating behavior, and to refer patients to mental health professionals with expertise in disordered eating or GI psychology.

Dr. Taft and Dr. Burton Murray reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2022.

Problems with eating and nutrition are common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other gastrointestinal disorders, but clinicians who treat them should be careful not to automatically assume that patients have eating disorders, according to a psychologist who specializes in the psychological and social aspects of chronic digestive diseases.

On the other hand, clinicians must also be aware of the possibility that patients could have a recently identified syndrome cluster called avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), said Tiffany Taft, PsyD, a research associate professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology), medical social sciences, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, Chicago. In a recent study, she and her colleagues defined ARFID as “failure to meet one’s nutritional needs owing to sensory hypersensitivity, lack of interest in eating, or fear of aversive consequences from eating, and is associated with negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.”

ARFID “is a hot topic that we really don’t understand,” she said in an online presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common among patients with IBD, “and nutritional deficiencies themselves can lead to symptoms or side effects that can cause people to eat less,” she said.

“As our vitamin B12 goes down, our cognitive functioning starts to decline, and we might not be making clear decisions in how we’re deciding what to eat, when to eat, if we should be eating at all – just something to think about in your patients who have nutritional deficiencies,” she told the audience.

Other common nutritional deficiencies that can affect eating and food choice among patients with IBD include low folate (B9) levels associated with sore tongue and weight loss, low iron levels leading to nausea and loss of appetite, and zinc deficiency leading to loss of appetite and alterations in taste and/or smell, she said.

Newly recognized in GI

She noted that “ARFID actually originates in the pediatric psychiatric literature, mostly in children with sensory issues [such as] autism spectrum disorder, so this is not a construct that started in digestive disease, but has been adapted and applied to patients with digestive disease, including IBD.”

The DSM-5 lists four criteria for ARFID: significant weight loss, significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral nutrition or oral supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functions.

Helen Burton Murray, PhD, director of the gastrointestinal behavioral health program in the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is familiar with Dr. Taft’s work, said in an interview that inclusion of ARFID in DSM-5 has put a name to a syndrome or symptom cluster that in all likelihood already existed.

However, “the jury is still out about whether, if we do diagnose patients who have digestive diseases with ARFID, that then helps them get to a treatment that improves their relationship with food and improves nutritional issues that may have occurred as a result of a restricted food intake,” she said.

“We don’t know yet if the diagnosis will actually improve things. In our clinical practice, anecdotally, it has, both for patients with IBDs and for patients with other GI conditions, particularly GI functional motility disorders. We’re a little bit more confident about making the diagnosis of ARFID in GI functional motility disorders than we are in IBD of course,” she said.

Screening measures

To get a better sense of the prevalence of ARFID, compared with reasonable responses to digestive diseases, Dr. Taft and colleagues conducted their cross-sectional study in 289 adults with achalasia, celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, or IBD.

They found that 51.3% of the total sample met the diagnostic criteria for ARFID based on the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS), including 75.7 % of patients with achalasia. But Dr. Taft had cautions

“I can tell you, working with achalasia patients, 75% do not have ARFID,” Dr. Taft said.

She noted that the 51.3% of patients with IBD identified by NIAS or the 53% identified by the ARFID+ scale as having ARFID was also highly doubtful.

Dr. Taft and colleagues determined that nearly half of the variance in the NIAS could be accounted for by GI symptoms rather than psychosocial factors, making it less than ideal for use in the clinic or by researchers.

She also noted, however, that she received an email from one of the creators of NIAS, Hana F. Zickgraf, PhD, from the University of South Alabama, Mobile. Dr. Zickgraf agreed that the scale had drawbacks when applied to patients with GI disease, and pointed instead to the Fear of Food Questionnaire, a newly developed 18-item GI disease-specific instrument. Dr. Taft recommended the new questionnaire for research purposes, and expressed hope that a shorter version could be made available for screening patients in clinic.

Dr. Burton Murray said that while the Fear of Food Questionnaire, perhaps in combination with NIAS, has the potential to be a useful screening tool, cutoffs for it have yet to be established.

“At the end of the day, the diagnosis would be made by a clinician who is able to determine whether the life impairment or if the nutritional impairment or restricted food intake are reasonable in the realm of their digestive disease, or could a treatment for ARFID be warranted to help them to make changes to improve their quality of life and nutrition,” she said.

Check biases at the door

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ARFID, clinicians should also consider biases, Dr. Taft said.

“Eating disorders are highly stigmatized and stereotyped diagnoses,” more often attributed to young White women than to either men or to people of racial or ethnic minorities, she said.

Cultural background may contribute to food restrictions, and the risk may increase with age, with 68% of patients with later-onset IBD restricting diets to control the disease. It’s also possible that beliefs about food and “clean and healthy” eating may influence food and eating choices after a patient receives an IBD diagnosis.

Dr. Taft also pointed out that clinicians and patients may have different ideas about what constitutes significant food avoidance. Clinicians may expect patients with IBD to eat despite feeling nauseated, having abdominal pains, or diarrhea, for example, when the same food avoidance might be deemed reasonable in patients with short-term GI infections.

“Severe IBD symptoms are a significant predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and PTSD is hallmarked by avoidance behaviors,” she added.

She emphasized the need for clinicians to ask the right questions of patients to get at the roots of their nutritional deficiency or eating behavior, and to refer patients to mental health professionals with expertise in disordered eating or GI psychology.

Dr. Taft and Dr. Burton Murray reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2022.

Problems with eating and nutrition are common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other gastrointestinal disorders, but clinicians who treat them should be careful not to automatically assume that patients have eating disorders, according to a psychologist who specializes in the psychological and social aspects of chronic digestive diseases.

On the other hand, clinicians must also be aware of the possibility that patients could have a recently identified syndrome cluster called avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), said Tiffany Taft, PsyD, a research associate professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology), medical social sciences, and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University, Chicago. In a recent study, she and her colleagues defined ARFID as “failure to meet one’s nutritional needs owing to sensory hypersensitivity, lack of interest in eating, or fear of aversive consequences from eating, and is associated with negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.”

ARFID “is a hot topic that we really don’t understand,” she said in an online presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutritional deficiencies are common among patients with IBD, “and nutritional deficiencies themselves can lead to symptoms or side effects that can cause people to eat less,” she said.

“As our vitamin B12 goes down, our cognitive functioning starts to decline, and we might not be making clear decisions in how we’re deciding what to eat, when to eat, if we should be eating at all – just something to think about in your patients who have nutritional deficiencies,” she told the audience.

Other common nutritional deficiencies that can affect eating and food choice among patients with IBD include low folate (B9) levels associated with sore tongue and weight loss, low iron levels leading to nausea and loss of appetite, and zinc deficiency leading to loss of appetite and alterations in taste and/or smell, she said.

Newly recognized in GI

She noted that “ARFID actually originates in the pediatric psychiatric literature, mostly in children with sensory issues [such as] autism spectrum disorder, so this is not a construct that started in digestive disease, but has been adapted and applied to patients with digestive disease, including IBD.”

The DSM-5 lists four criteria for ARFID: significant weight loss, significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral nutrition or oral supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functions.

Helen Burton Murray, PhD, director of the gastrointestinal behavioral health program in the Center for Neurointestinal Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who is familiar with Dr. Taft’s work, said in an interview that inclusion of ARFID in DSM-5 has put a name to a syndrome or symptom cluster that in all likelihood already existed.

However, “the jury is still out about whether, if we do diagnose patients who have digestive diseases with ARFID, that then helps them get to a treatment that improves their relationship with food and improves nutritional issues that may have occurred as a result of a restricted food intake,” she said.

“We don’t know yet if the diagnosis will actually improve things. In our clinical practice, anecdotally, it has, both for patients with IBDs and for patients with other GI conditions, particularly GI functional motility disorders. We’re a little bit more confident about making the diagnosis of ARFID in GI functional motility disorders than we are in IBD of course,” she said.

Screening measures

To get a better sense of the prevalence of ARFID, compared with reasonable responses to digestive diseases, Dr. Taft and colleagues conducted their cross-sectional study in 289 adults with achalasia, celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, or IBD.

They found that 51.3% of the total sample met the diagnostic criteria for ARFID based on the Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS), including 75.7 % of patients with achalasia. But Dr. Taft had cautions

“I can tell you, working with achalasia patients, 75% do not have ARFID,” Dr. Taft said.

She noted that the 51.3% of patients with IBD identified by NIAS or the 53% identified by the ARFID+ scale as having ARFID was also highly doubtful.

Dr. Taft and colleagues determined that nearly half of the variance in the NIAS could be accounted for by GI symptoms rather than psychosocial factors, making it less than ideal for use in the clinic or by researchers.

She also noted, however, that she received an email from one of the creators of NIAS, Hana F. Zickgraf, PhD, from the University of South Alabama, Mobile. Dr. Zickgraf agreed that the scale had drawbacks when applied to patients with GI disease, and pointed instead to the Fear of Food Questionnaire, a newly developed 18-item GI disease-specific instrument. Dr. Taft recommended the new questionnaire for research purposes, and expressed hope that a shorter version could be made available for screening patients in clinic.

Dr. Burton Murray said that while the Fear of Food Questionnaire, perhaps in combination with NIAS, has the potential to be a useful screening tool, cutoffs for it have yet to be established.

“At the end of the day, the diagnosis would be made by a clinician who is able to determine whether the life impairment or if the nutritional impairment or restricted food intake are reasonable in the realm of their digestive disease, or could a treatment for ARFID be warranted to help them to make changes to improve their quality of life and nutrition,” she said.

Check biases at the door

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ARFID, clinicians should also consider biases, Dr. Taft said.

“Eating disorders are highly stigmatized and stereotyped diagnoses,” more often attributed to young White women than to either men or to people of racial or ethnic minorities, she said.

Cultural background may contribute to food restrictions, and the risk may increase with age, with 68% of patients with later-onset IBD restricting diets to control the disease. It’s also possible that beliefs about food and “clean and healthy” eating may influence food and eating choices after a patient receives an IBD diagnosis.

Dr. Taft also pointed out that clinicians and patients may have different ideas about what constitutes significant food avoidance. Clinicians may expect patients with IBD to eat despite feeling nauseated, having abdominal pains, or diarrhea, for example, when the same food avoidance might be deemed reasonable in patients with short-term GI infections.

“Severe IBD symptoms are a significant predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and PTSD is hallmarked by avoidance behaviors,” she added.

She emphasized the need for clinicians to ask the right questions of patients to get at the roots of their nutritional deficiency or eating behavior, and to refer patients to mental health professionals with expertise in disordered eating or GI psychology.

Dr. Taft and Dr. Burton Murray reported having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article was updated on Feb. 4, 2022.

FROM CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

Lower Leg Hyperpigmentation in MYH9-Related Disorder

To the Editor:

MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.1 We describe a case of lower leg hyperpigmentation secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

A 31-year-old woman with a history of MYH9-related disorder and mixed connective tissue disease presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with asymptomatic brown patches on the lower legs (Figure) of 10 years’ duration. She also had epistaxis, hearing loss, renal disease, and menorrhagia secondary to MYH9-related disorder. The patient had been started on hydroxychloroquine 2 years earlier by rheumatology for mixed connective tissue disorder. A biopsy was not performed, given the risk of bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Ammonium lactate lotion was recommended for the leg patches. No further interventions were undertaken. At 6-month follow-up, hyperpigmentation on the lower legs was stable. The patient expressed no desire for cosmetic intervention.

Prior to discovery of a common gene, MYH9-related disorder was classified as 4 overlapping syndromes: May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian syndrome.2 More than 30 MYH9 mutations have been identified, all of which encode for myosin-9, a subunit of myosin IIA,1,3 that is a nonmuscle myosin needed for cell movement, shape, and cytokinesis. Although most cells use myosin IIA to IIC, certain cells, such as platelets and neutrophils, use myosin IIA exclusively.

In neutrophils of patients with MYH9-related disorder, nonfunctional myosin-9 clumps to form hallmark inclusion bodies, which are seen on the peripheral blood smear. Macrothrombocytopenia, another hallmark of MYH9-related disorder, also can be seen on the peripheral smear of all affected patients. Approximately 30%of patients develop clinical manifestations of the disorder (eg, bleeding, renal failure, hearing loss, presenile cataracts). Bleeding tendency usually is mild; epistaxis and menorrhagia are the most common hematologic manifestations.4

We attribute the lower leg hyperpigmentation in our patient to a severe phenotype of MYH9-related disorder. In addition to hyperpigmentation, our patient had menorrhagia requiring treatment with tranexamic acid, renal failure, and hearing loss, further pointing to a more severe phenotype. Furthermore, it is likely that our patient’s hyperpigmentation was made worse by hydroxychloroquine and a coexisting diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease, which led to a propensity for increased vessel fragility in the setting of thrombocytopenia.

The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder. The presence of small red blood cells (RBCs) in microcytic anemia and large platelets of MYH9-related disorder can lead to a situation in which platelets travel near the center of the lumen of blood vessels, while RBCs travel to the periphery. This decrease in the platelet-endothelium interaction increases the risk for bleeding. Our patient’s hemoglobin level was within reference range, without evidence of iron-deficiency anemia. Correction of iron-deficiency anemia, if applicable, can prevent bleeding brought on by the mechanism of decreased platelet-endothelium interaction and avoid unnecessary antiplatelet medication because of misdiagnosis based on an erroneous platelet count.

The workup of MYH9-related disorder also should include audiography, ophthalmologic examination, and renal function testing for hearing loss, cataracts, and renal disease, respectively. Referral to genetics also may be warranted.

It also is of clinical interest that automated cell counters may underestimate the count of abnormally large platelets in MYH9-related disorder, counting them as RBCs or white blood cells. The platelet count in MYH9-related disorder may be underestimated by 4-fold or greater.4-7

Treatment of leg hyperpigmentation can prove challenging, given the location of dermal hemosiderin. Topical therapy likely is ineffective. Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are treatment modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9-related disorder. There have been reports of improved cosmesis in dermal hemosiderin depositional disorders, such as venous stasis.4 Our patient was given ammonium lactate lotion to thicken collagen, possibly preventing future bleeding episodes.

- Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169-3178. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi344

- Seri M, Pecci A, Di Bari F, et al. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:203-215. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c

- Medline Plus. MYH9-related disorder. National Library of Medicine website. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/myh9-related-disorder#diagnosis

- Althaus K, Greinachar A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189-203. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220327

- Kunishima S, Hamaguchi M, Saito H. Differential expression of wild-type and mutant NMMHC-IIA polypeptides in blood cells suggests cell-specific regulation mechanisms in MYH9 disorders. Blood. 2008;111:3015-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116194

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, et al. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65-74. doi:10.1681/ASN.V13165

- Selleng K, Lubenow LE, Greinacher A, et al. Perioperative management of MYH9 hereditary macrothrombocytopenia (Fechtner syndrome). Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:263-268. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00913.x

To the Editor:

MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.1 We describe a case of lower leg hyperpigmentation secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

A 31-year-old woman with a history of MYH9-related disorder and mixed connective tissue disease presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with asymptomatic brown patches on the lower legs (Figure) of 10 years’ duration. She also had epistaxis, hearing loss, renal disease, and menorrhagia secondary to MYH9-related disorder. The patient had been started on hydroxychloroquine 2 years earlier by rheumatology for mixed connective tissue disorder. A biopsy was not performed, given the risk of bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Ammonium lactate lotion was recommended for the leg patches. No further interventions were undertaken. At 6-month follow-up, hyperpigmentation on the lower legs was stable. The patient expressed no desire for cosmetic intervention.

Prior to discovery of a common gene, MYH9-related disorder was classified as 4 overlapping syndromes: May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian syndrome.2 More than 30 MYH9 mutations have been identified, all of which encode for myosin-9, a subunit of myosin IIA,1,3 that is a nonmuscle myosin needed for cell movement, shape, and cytokinesis. Although most cells use myosin IIA to IIC, certain cells, such as platelets and neutrophils, use myosin IIA exclusively.

In neutrophils of patients with MYH9-related disorder, nonfunctional myosin-9 clumps to form hallmark inclusion bodies, which are seen on the peripheral blood smear. Macrothrombocytopenia, another hallmark of MYH9-related disorder, also can be seen on the peripheral smear of all affected patients. Approximately 30%of patients develop clinical manifestations of the disorder (eg, bleeding, renal failure, hearing loss, presenile cataracts). Bleeding tendency usually is mild; epistaxis and menorrhagia are the most common hematologic manifestations.4

We attribute the lower leg hyperpigmentation in our patient to a severe phenotype of MYH9-related disorder. In addition to hyperpigmentation, our patient had menorrhagia requiring treatment with tranexamic acid, renal failure, and hearing loss, further pointing to a more severe phenotype. Furthermore, it is likely that our patient’s hyperpigmentation was made worse by hydroxychloroquine and a coexisting diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease, which led to a propensity for increased vessel fragility in the setting of thrombocytopenia.

The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder. The presence of small red blood cells (RBCs) in microcytic anemia and large platelets of MYH9-related disorder can lead to a situation in which platelets travel near the center of the lumen of blood vessels, while RBCs travel to the periphery. This decrease in the platelet-endothelium interaction increases the risk for bleeding. Our patient’s hemoglobin level was within reference range, without evidence of iron-deficiency anemia. Correction of iron-deficiency anemia, if applicable, can prevent bleeding brought on by the mechanism of decreased platelet-endothelium interaction and avoid unnecessary antiplatelet medication because of misdiagnosis based on an erroneous platelet count.

The workup of MYH9-related disorder also should include audiography, ophthalmologic examination, and renal function testing for hearing loss, cataracts, and renal disease, respectively. Referral to genetics also may be warranted.

It also is of clinical interest that automated cell counters may underestimate the count of abnormally large platelets in MYH9-related disorder, counting them as RBCs or white blood cells. The platelet count in MYH9-related disorder may be underestimated by 4-fold or greater.4-7

Treatment of leg hyperpigmentation can prove challenging, given the location of dermal hemosiderin. Topical therapy likely is ineffective. Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are treatment modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9-related disorder. There have been reports of improved cosmesis in dermal hemosiderin depositional disorders, such as venous stasis.4 Our patient was given ammonium lactate lotion to thicken collagen, possibly preventing future bleeding episodes.

To the Editor:

MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.1 We describe a case of lower leg hyperpigmentation secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

A 31-year-old woman with a history of MYH9-related disorder and mixed connective tissue disease presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with asymptomatic brown patches on the lower legs (Figure) of 10 years’ duration. She also had epistaxis, hearing loss, renal disease, and menorrhagia secondary to MYH9-related disorder. The patient had been started on hydroxychloroquine 2 years earlier by rheumatology for mixed connective tissue disorder. A biopsy was not performed, given the risk of bleeding from thrombocytopenia. Ammonium lactate lotion was recommended for the leg patches. No further interventions were undertaken. At 6-month follow-up, hyperpigmentation on the lower legs was stable. The patient expressed no desire for cosmetic intervention.

Prior to discovery of a common gene, MYH9-related disorder was classified as 4 overlapping syndromes: May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Sebastian syndrome.2 More than 30 MYH9 mutations have been identified, all of which encode for myosin-9, a subunit of myosin IIA,1,3 that is a nonmuscle myosin needed for cell movement, shape, and cytokinesis. Although most cells use myosin IIA to IIC, certain cells, such as platelets and neutrophils, use myosin IIA exclusively.

In neutrophils of patients with MYH9-related disorder, nonfunctional myosin-9 clumps to form hallmark inclusion bodies, which are seen on the peripheral blood smear. Macrothrombocytopenia, another hallmark of MYH9-related disorder, also can be seen on the peripheral smear of all affected patients. Approximately 30%of patients develop clinical manifestations of the disorder (eg, bleeding, renal failure, hearing loss, presenile cataracts). Bleeding tendency usually is mild; epistaxis and menorrhagia are the most common hematologic manifestations.4

We attribute the lower leg hyperpigmentation in our patient to a severe phenotype of MYH9-related disorder. In addition to hyperpigmentation, our patient had menorrhagia requiring treatment with tranexamic acid, renal failure, and hearing loss, further pointing to a more severe phenotype. Furthermore, it is likely that our patient’s hyperpigmentation was made worse by hydroxychloroquine and a coexisting diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease, which led to a propensity for increased vessel fragility in the setting of thrombocytopenia.

The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder. The presence of small red blood cells (RBCs) in microcytic anemia and large platelets of MYH9-related disorder can lead to a situation in which platelets travel near the center of the lumen of blood vessels, while RBCs travel to the periphery. This decrease in the platelet-endothelium interaction increases the risk for bleeding. Our patient’s hemoglobin level was within reference range, without evidence of iron-deficiency anemia. Correction of iron-deficiency anemia, if applicable, can prevent bleeding brought on by the mechanism of decreased platelet-endothelium interaction and avoid unnecessary antiplatelet medication because of misdiagnosis based on an erroneous platelet count.

The workup of MYH9-related disorder also should include audiography, ophthalmologic examination, and renal function testing for hearing loss, cataracts, and renal disease, respectively. Referral to genetics also may be warranted.

It also is of clinical interest that automated cell counters may underestimate the count of abnormally large platelets in MYH9-related disorder, counting them as RBCs or white blood cells. The platelet count in MYH9-related disorder may be underestimated by 4-fold or greater.4-7

Treatment of leg hyperpigmentation can prove challenging, given the location of dermal hemosiderin. Topical therapy likely is ineffective. Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are treatment modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9-related disorder. There have been reports of improved cosmesis in dermal hemosiderin depositional disorders, such as venous stasis.4 Our patient was given ammonium lactate lotion to thicken collagen, possibly preventing future bleeding episodes.

- Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169-3178. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi344

- Seri M, Pecci A, Di Bari F, et al. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:203-215. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c

- Medline Plus. MYH9-related disorder. National Library of Medicine website. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/myh9-related-disorder#diagnosis

- Althaus K, Greinachar A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189-203. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220327

- Kunishima S, Hamaguchi M, Saito H. Differential expression of wild-type and mutant NMMHC-IIA polypeptides in blood cells suggests cell-specific regulation mechanisms in MYH9 disorders. Blood. 2008;111:3015-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116194

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, et al. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65-74. doi:10.1681/ASN.V13165

- Selleng K, Lubenow LE, Greinacher A, et al. Perioperative management of MYH9 hereditary macrothrombocytopenia (Fechtner syndrome). Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:263-268. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00913.x

- Pecci A, Canobbio I, Balduini A, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hematological abnormalities of patients with MYH9 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3169-3178. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi344

- Seri M, Pecci A, Di Bari F, et al. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:203-215. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c

- Medline Plus. MYH9-related disorder. National Library of Medicine website. Updated August 18, 2020. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/myh9-related-disorder#diagnosis

- Althaus K, Greinachar A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189-203. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220327

- Kunishima S, Hamaguchi M, Saito H. Differential expression of wild-type and mutant NMMHC-IIA polypeptides in blood cells suggests cell-specific regulation mechanisms in MYH9 disorders. Blood. 2008;111:3015-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-116194

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, et al. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65-74. doi:10.1681/ASN.V13165

- Selleng K, Lubenow LE, Greinacher A, et al. Perioperative management of MYH9 hereditary macrothrombocytopenia (Fechtner syndrome). Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:263-268. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00913.x

Practice Points

- MYH9-related disorder is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by macrothrombocytopenia and neutrophil inclusions secondary to defective myosin-9.

- Leg hyperpigmentation can occur secondary to hemosiderin deposition from MYH9-related disorder.

- The workup of suspected MYH9-related disorder includes exclusion of iron-deficiency anemia, which can increase bleeding in patients with the disorder.

- Lasers and intense pulsed light therapy are modalities to consider for the hyperpigmentation of MYH9- related disorder.

Topline data for aficamten positive in obstructive HCM

The investigational, next-generation cardiac myosin inhibitor aficamten (previously CK-274, Cytokinetics) continues to show promise as a potential treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Today, the company announced positive topline results from cohort 3 of the REDWOOD-HCM phase 2 clinical trial, which included 13 patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM and a resting or post-Valsalva left ventricular outflow tract pressure gradient (LVOT-G) of 50 mm Hg or greater whose background therapy included disopyramide.

Treatment with aficamten led to substantial reductions in the average resting LVOT-G, as well as the post-Valsalva LVOT-G (defined as resting gradient less than 30 mm Hg and post-Valsalva gradient less than 50 mm Hg), the company reported.

These “clinically relevant” decreases in pressure gradients were achieved with only modest decreases in average left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), the company said.

In no patient did LVEF fall below the prespecified safety threshold of 50%.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class was improved in most patients.

The safety and tolerability of aficamten in cohort 3 were consistent with previous experience in the REDWOOD-HCM trial, with no treatment interruptions and no serious treatment-related adverse events.

The pharmacokinetic data from cohort 3 are similar to those observed in REDWOOD-HCM cohorts 1 and 2, which included HCM patients taking background medications exclusive of disopyramide, as reported previously by this news organization.

“We are encouraged by the clinically relevant reductions in the LVOT gradient observed in these medically refractory patients and are pleased with the safety profile of aficamten when administered in combination with disopyramide,” Fady Malik, MD, PhD, Cytokinetics’ executive vice president of research and development, said in a news release.

“These results represent the first report of patients with obstructive HCM treated with a combination of a cardiac myosin inhibitor and disopyramide and support our plan to include this patient population in SEQUOIA-HCM, our phase 3 trial, which is important, given these patients have exhausted other available medical therapies,” Dr. Malik said.

The results from cohort 3 of the REDWOOD-HCM trial will be presented at the upcoming American College of Cardiology Annual Meeting in April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The investigational, next-generation cardiac myosin inhibitor aficamten (previously CK-274, Cytokinetics) continues to show promise as a potential treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Today, the company announced positive topline results from cohort 3 of the REDWOOD-HCM phase 2 clinical trial, which included 13 patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM and a resting or post-Valsalva left ventricular outflow tract pressure gradient (LVOT-G) of 50 mm Hg or greater whose background therapy included disopyramide.

Treatment with aficamten led to substantial reductions in the average resting LVOT-G, as well as the post-Valsalva LVOT-G (defined as resting gradient less than 30 mm Hg and post-Valsalva gradient less than 50 mm Hg), the company reported.

These “clinically relevant” decreases in pressure gradients were achieved with only modest decreases in average left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), the company said.

In no patient did LVEF fall below the prespecified safety threshold of 50%.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class was improved in most patients.

The safety and tolerability of aficamten in cohort 3 were consistent with previous experience in the REDWOOD-HCM trial, with no treatment interruptions and no serious treatment-related adverse events.

The pharmacokinetic data from cohort 3 are similar to those observed in REDWOOD-HCM cohorts 1 and 2, which included HCM patients taking background medications exclusive of disopyramide, as reported previously by this news organization.

“We are encouraged by the clinically relevant reductions in the LVOT gradient observed in these medically refractory patients and are pleased with the safety profile of aficamten when administered in combination with disopyramide,” Fady Malik, MD, PhD, Cytokinetics’ executive vice president of research and development, said in a news release.

“These results represent the first report of patients with obstructive HCM treated with a combination of a cardiac myosin inhibitor and disopyramide and support our plan to include this patient population in SEQUOIA-HCM, our phase 3 trial, which is important, given these patients have exhausted other available medical therapies,” Dr. Malik said.

The results from cohort 3 of the REDWOOD-HCM trial will be presented at the upcoming American College of Cardiology Annual Meeting in April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The investigational, next-generation cardiac myosin inhibitor aficamten (previously CK-274, Cytokinetics) continues to show promise as a potential treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Today, the company announced positive topline results from cohort 3 of the REDWOOD-HCM phase 2 clinical trial, which included 13 patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM and a resting or post-Valsalva left ventricular outflow tract pressure gradient (LVOT-G) of 50 mm Hg or greater whose background therapy included disopyramide.

Treatment with aficamten led to substantial reductions in the average resting LVOT-G, as well as the post-Valsalva LVOT-G (defined as resting gradient less than 30 mm Hg and post-Valsalva gradient less than 50 mm Hg), the company reported.

These “clinically relevant” decreases in pressure gradients were achieved with only modest decreases in average left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), the company said.

In no patient did LVEF fall below the prespecified safety threshold of 50%.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class was improved in most patients.

The safety and tolerability of aficamten in cohort 3 were consistent with previous experience in the REDWOOD-HCM trial, with no treatment interruptions and no serious treatment-related adverse events.

The pharmacokinetic data from cohort 3 are similar to those observed in REDWOOD-HCM cohorts 1 and 2, which included HCM patients taking background medications exclusive of disopyramide, as reported previously by this news organization.

“We are encouraged by the clinically relevant reductions in the LVOT gradient observed in these medically refractory patients and are pleased with the safety profile of aficamten when administered in combination with disopyramide,” Fady Malik, MD, PhD, Cytokinetics’ executive vice president of research and development, said in a news release.

“These results represent the first report of patients with obstructive HCM treated with a combination of a cardiac myosin inhibitor and disopyramide and support our plan to include this patient population in SEQUOIA-HCM, our phase 3 trial, which is important, given these patients have exhausted other available medical therapies,” Dr. Malik said.

The results from cohort 3 of the REDWOOD-HCM trial will be presented at the upcoming American College of Cardiology Annual Meeting in April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If you give a mouse a genetically engineered bitcoin wallet

The world’s most valuable mouse

You’ve heard of Mighty Mouse. Now say hello to the world’s newest mouse superhero, Crypto-Mouse! After being bitten by a radioactive cryptocurrency investor, Crypto-Mouse can tap directly into the power of the blockchain itself, allowing it to perform incredible, death-defying feats of strength!

We’re going to stop right there before Crypto-Mouse gains entry into the Marvel cinematic universe. Let’s rewind to the beginning, because that’s precisely where this crazy scheme is at. In late January, a new decentralized autonomous organization, BitMouseDAO, launched to enormous … -ly little fanfare, according to Vice. Two investors as of Jan. 31. But what they lack in money they make up for in sheer ambition.

BitMouseDAO’s $100 million dollar idea is to genetically engineer mice to carry bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency and one of the most valuable. This isn’t as crazy an idea as it sounds since DNA can be modified to store information, potentially even bitcoin information. Their plan is to create a private bitcoin wallet, which will be stored in the mouse DNA, and purchase online bitcoin to store in this wallet.

BitMouseDAO, being a “collection of artists,” plans to partner with a lab to translate its private key into a specific DNA sequence to be encoded into the mice during fertilization; or, if that doesn’t work, inject them with a harmless virus that carries the key.

Since these are artists, their ultimate plan is to use their bitcoin mice to make NFTs (scratch that off your cryptocurrency bingo card) and auction them off to people. Or, as Vice put it, BitMouseDAO essentially plans to send preserved dead mice to people. Artistic dead mice! Artistic dead mice worth millions! Maybe. Even BitMouseDAO admits bitcoin could be worthless by the time the project gets off the ground.

If this all sounds completely insane, that’s because it is. But it also sounds crazy enough to work. Now, if you’ll excuse us, we’re off to write a screenplay about a scrappy group of high-tech thieves who steal a group of genetically altered bitcoin mice to sell for millions, only to keep them as their adorable pets. Trust us Hollywood, it’ll make millions!

Alcoholic monkeys vs. the future of feces

Which is more important, the journey or the destination? Science is all about the destination, yes? Solving the problem, saving a life, expanding horizons. That’s science. Or is it? The scientific method is a process, so does that make it a journey?

For us, today’s journey begins at the University of Iowa, where investigators are trying to reduce alcohol consumption. A worthy goal, and they seem to have made some progress by targeting a liver hormone called fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). But we’re more interested in the process right now, so bring on the alcoholic monkeys. And no, that’s not a death metal/reggae fusion band. Should be, though.

“The vervet monkey population is [composed] of alcohol avoiders, moderate alcohol drinkers, and a group of heavy drinkers,” Matthew Potthoff, PhD, and associates wrote in Cell Metabolism. When this particular bunch of heavy-drinking vervets were given FGF21, they consumed 50% less alcohol than did vehicle-treated controls, so mission accomplished.

Maybe it could be a breakfast cereal. Who wouldn’t enjoy a bowl of alcoholic monkeys in the morning?

And after breakfast, you might be ready for a digitized bowel movement, courtesy of researchers at University of California, San Diego. They’re studying ulcerative colitis (UC) by examining the gut microbiome, and their “most useful biological sample is patient stool,” according to a written statement from the university.

“Once we had all the technology to digitize the stool, the question was, is this going to tell us what’s happening in these patients? The answer turned out to be yes,” co-senior author Rob Knight, PhD, said in the statement. “Digitizing fecal material is the future.” The road to UC treatment, in other words, is paved with digital stool.

About 40% of the UC patients had elevated protease levels, and their high-protease feces were then transplanted into germ-free mice, which subsequently developed colitis and were successfully treated with protease inhibitors. And that is our final destination.

As our revered founder and mentor, Josephine Lotmevich, used to say, an alcoholic monkey in the hand is worth a number 2 in the bush.

Raise a glass to delinquency

You wouldn’t think that a glass of water could lead to a life of crime, but a recent study suggests just that.

Children exposed to lead in their drinking water during their early years had a 21% higher risk of delinquency after the age of 14 years and a 38% higher risk of having a record for a serious complaint, Jackie MacDonald Gibson and associates said in a statement on Eurekalert.

Data for the study came from Wake County, N.C., which includes rural areas, wealthy exurban developments, and predominantly Black communities. The investigators compared the blood lead levels for children tested between 1998 and 2011 with juvenile delinquency reports of the same children from the N.C. Department of Public Safety.

The main culprit, they found, was well water. Blood lead levels were 11% higher in the children whose water came from private wells, compared with children using community water. About 13% of U.S. households rely on private wells, which are not regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act, for their water supply.

The researchers said there is an urgent need for better drinking-water solutions in communities that rely on well water, whether it be through subsidized home filtration or infrastructure redevelopment.

An earlier study had estimated that preventing just one child from entering the adult criminal justice system would save $1.3 to $1.5 million in 1997 dollars. That’s about $2.2 to $2.5 million dollars today!

If you do the math, it’s not hard to see what’s cheaper (and healthier) in the long run.

A ‘dirty’ scam

Another one? This is just getting sad. You’ve probably heard of muds and clays being good for the skin and maybe you’ve gone to a spa and sat in a mud bath, but would you believe it if someone told you that mud can cure all your ailments? No? Neither would we. Senatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke was definitely someone who brought this strange treatment to light, but it seems like this is something that has been going on for years, even before the pandemic.

A company called Black Oxygen Organics (BOO) was selling “magic dirt” for $110 per 4-ounce package. It claimed the dirt was high in fulvic acid and humic acid, which are good for many things. They were, however, literally getting this mud from bogs with landfills nearby, Mel magazine reported.

That doesn’t sound appealing at all, but wait, there’s more. People were eating, drinking, bathing, and feeding their families this sludge in hopes that they would be cured of their ailments. A lot of people jumped aboard the magic dirt train when the pandemic arose, but it quickly became clear that this mud was not as helpful as BOO claimed it to be.

“We began to receive inquiries and calls on our website with people having problems and issues. Ultimately, we sent the products out for independent testing, and then when that came back and showed that there were toxic heavy metals [lead, arsenic, and cadmium among them] at an unsafe level, that’s when we knew we had to act,” Atlanta-based attorney Matt Wetherington, who filed a federal lawsuit against BOO, told Mel.

After a very complicated series of events involving an expose by NBC, product recalls, extortion claims, and grassroots activism, BOO was shut down by both the Canadian and U.S. governments.

As always, please listen only to health care professionals when you wish to use natural remedies for illnesses and ailments.

The world’s most valuable mouse

You’ve heard of Mighty Mouse. Now say hello to the world’s newest mouse superhero, Crypto-Mouse! After being bitten by a radioactive cryptocurrency investor, Crypto-Mouse can tap directly into the power of the blockchain itself, allowing it to perform incredible, death-defying feats of strength!

We’re going to stop right there before Crypto-Mouse gains entry into the Marvel cinematic universe. Let’s rewind to the beginning, because that’s precisely where this crazy scheme is at. In late January, a new decentralized autonomous organization, BitMouseDAO, launched to enormous … -ly little fanfare, according to Vice. Two investors as of Jan. 31. But what they lack in money they make up for in sheer ambition.

BitMouseDAO’s $100 million dollar idea is to genetically engineer mice to carry bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency and one of the most valuable. This isn’t as crazy an idea as it sounds since DNA can be modified to store information, potentially even bitcoin information. Their plan is to create a private bitcoin wallet, which will be stored in the mouse DNA, and purchase online bitcoin to store in this wallet.

BitMouseDAO, being a “collection of artists,” plans to partner with a lab to translate its private key into a specific DNA sequence to be encoded into the mice during fertilization; or, if that doesn’t work, inject them with a harmless virus that carries the key.

Since these are artists, their ultimate plan is to use their bitcoin mice to make NFTs (scratch that off your cryptocurrency bingo card) and auction them off to people. Or, as Vice put it, BitMouseDAO essentially plans to send preserved dead mice to people. Artistic dead mice! Artistic dead mice worth millions! Maybe. Even BitMouseDAO admits bitcoin could be worthless by the time the project gets off the ground.

If this all sounds completely insane, that’s because it is. But it also sounds crazy enough to work. Now, if you’ll excuse us, we’re off to write a screenplay about a scrappy group of high-tech thieves who steal a group of genetically altered bitcoin mice to sell for millions, only to keep them as their adorable pets. Trust us Hollywood, it’ll make millions!

Alcoholic monkeys vs. the future of feces

Which is more important, the journey or the destination? Science is all about the destination, yes? Solving the problem, saving a life, expanding horizons. That’s science. Or is it? The scientific method is a process, so does that make it a journey?

For us, today’s journey begins at the University of Iowa, where investigators are trying to reduce alcohol consumption. A worthy goal, and they seem to have made some progress by targeting a liver hormone called fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). But we’re more interested in the process right now, so bring on the alcoholic monkeys. And no, that’s not a death metal/reggae fusion band. Should be, though.

“The vervet monkey population is [composed] of alcohol avoiders, moderate alcohol drinkers, and a group of heavy drinkers,” Matthew Potthoff, PhD, and associates wrote in Cell Metabolism. When this particular bunch of heavy-drinking vervets were given FGF21, they consumed 50% less alcohol than did vehicle-treated controls, so mission accomplished.

Maybe it could be a breakfast cereal. Who wouldn’t enjoy a bowl of alcoholic monkeys in the morning?

And after breakfast, you might be ready for a digitized bowel movement, courtesy of researchers at University of California, San Diego. They’re studying ulcerative colitis (UC) by examining the gut microbiome, and their “most useful biological sample is patient stool,” according to a written statement from the university.

“Once we had all the technology to digitize the stool, the question was, is this going to tell us what’s happening in these patients? The answer turned out to be yes,” co-senior author Rob Knight, PhD, said in the statement. “Digitizing fecal material is the future.” The road to UC treatment, in other words, is paved with digital stool.

About 40% of the UC patients had elevated protease levels, and their high-protease feces were then transplanted into germ-free mice, which subsequently developed colitis and were successfully treated with protease inhibitors. And that is our final destination.