User login

cfDNA screening for the common trisomies performs well in low-risk pregnancies

Key clinical point: In women at low risk for aneuploidy, single-nucleotide polymorphism-based cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 (T21, T18, T13, respectively) demonstrates similar high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) as those in high-risk women.

Main finding: In low-risk vs. high-risk women, T21 was detected with similar sensitivity (100% vs. 98.8%; P = 1.0), specificity (99.98% vs. 99.96%; P = .61), and a high PPV (85.71% vs. 97.53%; P = .06), with analogous results for T18 and T13.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, prospective, observational SMART study including 17,851 pregnant women undergoing cfDNA screening for aneuploidy and 22q11.2DS, along with DNA analysis of the fetus or newborn. Of these, 13,043 pregnancies were at low risk for aneuploidy, with the rest being high risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Natera, Inc, CA, USA. Some of the authors, including the lead author, received institutional research support from Natera. M Egbert, Z Demko, M Rabinowitz, and K Martin serve as an employee/consultant of Natera and own stocks/options. J Hyett has participated in expert consultancies for and B Jacobson reports research clinical diagnostic trials with Natera, among others.

Source: Dar P et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.019.

Key clinical point: In women at low risk for aneuploidy, single-nucleotide polymorphism-based cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 (T21, T18, T13, respectively) demonstrates similar high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) as those in high-risk women.

Main finding: In low-risk vs. high-risk women, T21 was detected with similar sensitivity (100% vs. 98.8%; P = 1.0), specificity (99.98% vs. 99.96%; P = .61), and a high PPV (85.71% vs. 97.53%; P = .06), with analogous results for T18 and T13.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, prospective, observational SMART study including 17,851 pregnant women undergoing cfDNA screening for aneuploidy and 22q11.2DS, along with DNA analysis of the fetus or newborn. Of these, 13,043 pregnancies were at low risk for aneuploidy, with the rest being high risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Natera, Inc, CA, USA. Some of the authors, including the lead author, received institutional research support from Natera. M Egbert, Z Demko, M Rabinowitz, and K Martin serve as an employee/consultant of Natera and own stocks/options. J Hyett has participated in expert consultancies for and B Jacobson reports research clinical diagnostic trials with Natera, among others.

Source: Dar P et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.019.

Key clinical point: In women at low risk for aneuploidy, single-nucleotide polymorphism-based cell-free DNA (cfDNA) screening for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 (T21, T18, T13, respectively) demonstrates similar high sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) as those in high-risk women.

Main finding: In low-risk vs. high-risk women, T21 was detected with similar sensitivity (100% vs. 98.8%; P = 1.0), specificity (99.98% vs. 99.96%; P = .61), and a high PPV (85.71% vs. 97.53%; P = .06), with analogous results for T18 and T13.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, prospective, observational SMART study including 17,851 pregnant women undergoing cfDNA screening for aneuploidy and 22q11.2DS, along with DNA analysis of the fetus or newborn. Of these, 13,043 pregnancies were at low risk for aneuploidy, with the rest being high risk.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Natera, Inc, CA, USA. Some of the authors, including the lead author, received institutional research support from Natera. M Egbert, Z Demko, M Rabinowitz, and K Martin serve as an employee/consultant of Natera and own stocks/options. J Hyett has participated in expert consultancies for and B Jacobson reports research clinical diagnostic trials with Natera, among others.

Source: Dar P et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 (Jan 24). Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.019.

Tips for connecting with your patients

It is a tough time to be a doctor. With the stresses of the pandemic, the continued unfettered rise of insurance company BS, and so many medical groups being bought up that we often don’t even know who makes the decisions, the patient can sometimes be hidden in the equation.

Be curious

When physicians are curious about why patients have symptoms, how those symptoms will affect their lives, and how worried the patient is about them, patients feel cared about.

Ascertaining how concerned patients are about their symptoms will help you make decisions on whether symptoms you are not concerned about actually need to be treated.

Limit use of EHRs when possible

Use of the electronic health record during visits is essential, but focusing on it too much can put a barrier between the physician and the patient.

Marmor and colleagues found there is an inverse relationship between time spent on the EHR by a patient’s physician and the patient’s satisfaction.1

Eye contact with the patient is important, especially when patients are sharing concerns they are scared about and upsetting experiences. There can be awkward pauses when looking things up on the EHR. Fill those pauses by explaining to the patient what you are doing, or chatting with the patient.

Consider teaching medical students

When a medical student works with you, it doubles the time the patient gets with a concerned listener. Students also can do a great job with timely follow-up and checking in with worried patients.

By having the student present in the clinic room, with the patient present, the patient can really feel heard. The student shares all the details the patient shared, and now their physician is hearing an organized, thoughtful report of the patients concerns.

In fact, I was involved in a study that showed that patients preferred in room presentations, and that they were more satisfied when students presented in the room.2

Use healing words

Some words carry loaded emotions. The word chronic, for example, has negative connotations, whereas the term persisting does not.

I will often ask patients how long they have been suffering from a symptom to imply my concern for what they are going through. The term “chief complaint” is outdated, and upsets patients when they see it in their medical record.

As a patient of mine once said to me: “I never complained about that problem, I just brought it to your attention.” No one wants to be seen as a complainer. Substituting the word concern for complaint works well.

Explain as you examine

People love to hear the term normal. When you are examining a patient, let them know when findings are normal.

I also find it helpful to explain to patients why I am doing certain physical exam maneuvers. This helps them assess how thorough we are in our thought process.

When patients feel their physicians are thorough, they have more confidence in them.

In summary

- Be curious.

- Do not overly focus on the EHR.

- Consider teaching a medical student.

- Be careful of word choice.

- “Overexplain” the physical exam.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as 3rd-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Marmor RA et al. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jan;9(1):11-4.

2. Rogers HD et al. Acad Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

It is a tough time to be a doctor. With the stresses of the pandemic, the continued unfettered rise of insurance company BS, and so many medical groups being bought up that we often don’t even know who makes the decisions, the patient can sometimes be hidden in the equation.

Be curious

When physicians are curious about why patients have symptoms, how those symptoms will affect their lives, and how worried the patient is about them, patients feel cared about.

Ascertaining how concerned patients are about their symptoms will help you make decisions on whether symptoms you are not concerned about actually need to be treated.

Limit use of EHRs when possible

Use of the electronic health record during visits is essential, but focusing on it too much can put a barrier between the physician and the patient.

Marmor and colleagues found there is an inverse relationship between time spent on the EHR by a patient’s physician and the patient’s satisfaction.1

Eye contact with the patient is important, especially when patients are sharing concerns they are scared about and upsetting experiences. There can be awkward pauses when looking things up on the EHR. Fill those pauses by explaining to the patient what you are doing, or chatting with the patient.

Consider teaching medical students

When a medical student works with you, it doubles the time the patient gets with a concerned listener. Students also can do a great job with timely follow-up and checking in with worried patients.

By having the student present in the clinic room, with the patient present, the patient can really feel heard. The student shares all the details the patient shared, and now their physician is hearing an organized, thoughtful report of the patients concerns.

In fact, I was involved in a study that showed that patients preferred in room presentations, and that they were more satisfied when students presented in the room.2

Use healing words

Some words carry loaded emotions. The word chronic, for example, has negative connotations, whereas the term persisting does not.

I will often ask patients how long they have been suffering from a symptom to imply my concern for what they are going through. The term “chief complaint” is outdated, and upsets patients when they see it in their medical record.

As a patient of mine once said to me: “I never complained about that problem, I just brought it to your attention.” No one wants to be seen as a complainer. Substituting the word concern for complaint works well.

Explain as you examine

People love to hear the term normal. When you are examining a patient, let them know when findings are normal.

I also find it helpful to explain to patients why I am doing certain physical exam maneuvers. This helps them assess how thorough we are in our thought process.

When patients feel their physicians are thorough, they have more confidence in them.

In summary

- Be curious.

- Do not overly focus on the EHR.

- Consider teaching a medical student.

- Be careful of word choice.

- “Overexplain” the physical exam.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as 3rd-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Marmor RA et al. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jan;9(1):11-4.

2. Rogers HD et al. Acad Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

It is a tough time to be a doctor. With the stresses of the pandemic, the continued unfettered rise of insurance company BS, and so many medical groups being bought up that we often don’t even know who makes the decisions, the patient can sometimes be hidden in the equation.

Be curious

When physicians are curious about why patients have symptoms, how those symptoms will affect their lives, and how worried the patient is about them, patients feel cared about.

Ascertaining how concerned patients are about their symptoms will help you make decisions on whether symptoms you are not concerned about actually need to be treated.

Limit use of EHRs when possible

Use of the electronic health record during visits is essential, but focusing on it too much can put a barrier between the physician and the patient.

Marmor and colleagues found there is an inverse relationship between time spent on the EHR by a patient’s physician and the patient’s satisfaction.1

Eye contact with the patient is important, especially when patients are sharing concerns they are scared about and upsetting experiences. There can be awkward pauses when looking things up on the EHR. Fill those pauses by explaining to the patient what you are doing, or chatting with the patient.

Consider teaching medical students

When a medical student works with you, it doubles the time the patient gets with a concerned listener. Students also can do a great job with timely follow-up and checking in with worried patients.

By having the student present in the clinic room, with the patient present, the patient can really feel heard. The student shares all the details the patient shared, and now their physician is hearing an organized, thoughtful report of the patients concerns.

In fact, I was involved in a study that showed that patients preferred in room presentations, and that they were more satisfied when students presented in the room.2

Use healing words

Some words carry loaded emotions. The word chronic, for example, has negative connotations, whereas the term persisting does not.

I will often ask patients how long they have been suffering from a symptom to imply my concern for what they are going through. The term “chief complaint” is outdated, and upsets patients when they see it in their medical record.

As a patient of mine once said to me: “I never complained about that problem, I just brought it to your attention.” No one wants to be seen as a complainer. Substituting the word concern for complaint works well.

Explain as you examine

People love to hear the term normal. When you are examining a patient, let them know when findings are normal.

I also find it helpful to explain to patients why I am doing certain physical exam maneuvers. This helps them assess how thorough we are in our thought process.

When patients feel their physicians are thorough, they have more confidence in them.

In summary

- Be curious.

- Do not overly focus on the EHR.

- Consider teaching a medical student.

- Be careful of word choice.

- “Overexplain” the physical exam.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as 3rd-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Marmor RA et al. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jan;9(1):11-4.

2. Rogers HD et al. Acad Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

Seizure phobia stands out in epilepsy patients

Anxiety and depression are known to affect quality of life in epilepsy patients, and previous studies have shown that anticipatory anxiety of epileptic seizures (AAS) was present in 53% of patients with focal epilepsy, wrote lead author Aviva Weiss of Psychiatric Hostels affiliated with Kidum Rehabilitation Projects, Jerusalem, and colleagues.

“Although recognized by the epilepsy and the psychiatric communities, seizure phobia as a distinct anxiety disorder among PWE is insufficiently described in the medical literature,” they said.

Seizure phobia has been defined as an anxiety disorder in which patients experience fear related to anticipation of seizures in certain situations.

In a study published in Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy, the researchers recruited 69 PWE who were treated at an outpatient clinic. Data were collected from interviews, questionnaires, and medical records. The average age of the participants was 36.8 years, 41 were women, and 41 were married.

Overall, 19 individuals (27.5%) were diagnosed with seizure phobia. Compared with PWE without seizure phobia, the seizure phobia patients were significantly more likely to be women (84.2% vs. 44.2%; P = .005) and to have comorbid anxiety disorders (84.2% vs. 34.9%; P = .01). Individuals with seizure phobia also were significantly more likely than those without seizure phobia to have a past major depressive episode (63.2% vs. 20.9%; P = .003), and posttraumatic stress disorder (26.3% vs. 7%; P = .05).

Seizure phobia was significantly associated with comorbid psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) (36.8% vs. 11.6%; P = .034). PNES have been significantly associated with panic attacks, and “all patients with both panic attacks and comorbid PNES were diagnosed with seizure phobia,” the researchers noted. However, no significant association was found with epilepsy-related variables, they said.

A multivariate logistic regression model to predict seizure phobia showed that anxiety and a past MDE were significant predictors; the odds of seizure phobia were 10.45 times higher if a patient reported any anxiety disorder, and 6.85 times higher if the patient had a history of MDE.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of semistructured interviews to diagnose seizure phobia, which are subject to interviewer bias, and by the small study population with a high proportion of comorbid PNES and epilepsy, the researchers noted. However, the results support seizure phobia as a distinct clinical entity worthy of management with education, psychosocial interventions, and potential medication changes, they said.

“Development of appropriate screening tools and implementation of effective treatment interventions is warranted for individual patients, combined with large-scale population-targeted psychoeducation, aimed to mitigate the risk of developing seizure phobia in PWE,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Anxiety and depression are known to affect quality of life in epilepsy patients, and previous studies have shown that anticipatory anxiety of epileptic seizures (AAS) was present in 53% of patients with focal epilepsy, wrote lead author Aviva Weiss of Psychiatric Hostels affiliated with Kidum Rehabilitation Projects, Jerusalem, and colleagues.

“Although recognized by the epilepsy and the psychiatric communities, seizure phobia as a distinct anxiety disorder among PWE is insufficiently described in the medical literature,” they said.

Seizure phobia has been defined as an anxiety disorder in which patients experience fear related to anticipation of seizures in certain situations.

In a study published in Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy, the researchers recruited 69 PWE who were treated at an outpatient clinic. Data were collected from interviews, questionnaires, and medical records. The average age of the participants was 36.8 years, 41 were women, and 41 were married.

Overall, 19 individuals (27.5%) were diagnosed with seizure phobia. Compared with PWE without seizure phobia, the seizure phobia patients were significantly more likely to be women (84.2% vs. 44.2%; P = .005) and to have comorbid anxiety disorders (84.2% vs. 34.9%; P = .01). Individuals with seizure phobia also were significantly more likely than those without seizure phobia to have a past major depressive episode (63.2% vs. 20.9%; P = .003), and posttraumatic stress disorder (26.3% vs. 7%; P = .05).

Seizure phobia was significantly associated with comorbid psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) (36.8% vs. 11.6%; P = .034). PNES have been significantly associated with panic attacks, and “all patients with both panic attacks and comorbid PNES were diagnosed with seizure phobia,” the researchers noted. However, no significant association was found with epilepsy-related variables, they said.

A multivariate logistic regression model to predict seizure phobia showed that anxiety and a past MDE were significant predictors; the odds of seizure phobia were 10.45 times higher if a patient reported any anxiety disorder, and 6.85 times higher if the patient had a history of MDE.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of semistructured interviews to diagnose seizure phobia, which are subject to interviewer bias, and by the small study population with a high proportion of comorbid PNES and epilepsy, the researchers noted. However, the results support seizure phobia as a distinct clinical entity worthy of management with education, psychosocial interventions, and potential medication changes, they said.

“Development of appropriate screening tools and implementation of effective treatment interventions is warranted for individual patients, combined with large-scale population-targeted psychoeducation, aimed to mitigate the risk of developing seizure phobia in PWE,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Anxiety and depression are known to affect quality of life in epilepsy patients, and previous studies have shown that anticipatory anxiety of epileptic seizures (AAS) was present in 53% of patients with focal epilepsy, wrote lead author Aviva Weiss of Psychiatric Hostels affiliated with Kidum Rehabilitation Projects, Jerusalem, and colleagues.

“Although recognized by the epilepsy and the psychiatric communities, seizure phobia as a distinct anxiety disorder among PWE is insufficiently described in the medical literature,” they said.

Seizure phobia has been defined as an anxiety disorder in which patients experience fear related to anticipation of seizures in certain situations.

In a study published in Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy, the researchers recruited 69 PWE who were treated at an outpatient clinic. Data were collected from interviews, questionnaires, and medical records. The average age of the participants was 36.8 years, 41 were women, and 41 were married.

Overall, 19 individuals (27.5%) were diagnosed with seizure phobia. Compared with PWE without seizure phobia, the seizure phobia patients were significantly more likely to be women (84.2% vs. 44.2%; P = .005) and to have comorbid anxiety disorders (84.2% vs. 34.9%; P = .01). Individuals with seizure phobia also were significantly more likely than those without seizure phobia to have a past major depressive episode (63.2% vs. 20.9%; P = .003), and posttraumatic stress disorder (26.3% vs. 7%; P = .05).

Seizure phobia was significantly associated with comorbid psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) (36.8% vs. 11.6%; P = .034). PNES have been significantly associated with panic attacks, and “all patients with both panic attacks and comorbid PNES were diagnosed with seizure phobia,” the researchers noted. However, no significant association was found with epilepsy-related variables, they said.

A multivariate logistic regression model to predict seizure phobia showed that anxiety and a past MDE were significant predictors; the odds of seizure phobia were 10.45 times higher if a patient reported any anxiety disorder, and 6.85 times higher if the patient had a history of MDE.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of semistructured interviews to diagnose seizure phobia, which are subject to interviewer bias, and by the small study population with a high proportion of comorbid PNES and epilepsy, the researchers noted. However, the results support seizure phobia as a distinct clinical entity worthy of management with education, psychosocial interventions, and potential medication changes, they said.

“Development of appropriate screening tools and implementation of effective treatment interventions is warranted for individual patients, combined with large-scale population-targeted psychoeducation, aimed to mitigate the risk of developing seizure phobia in PWE,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SEIZURE: EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF EPILEPSY

A 19-month-old vaccinated female with 2 days of rash

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis that typically affects children between 4 months and 2 years of age.1 Etiology is unknown but the majority of cases are preceded by infections, vaccinations, or certain medications.2

AHEI is a self-limited disease that runs a benign course with spontaneous resolution within days to 3 weeks.3 Classic presentation involves acute onset of fever, purpura, ecchymosis, and inflammatory edema. Edema is often the first sign, and may involve the face, ears, scrotum, or extremities. Hemorrhagic lesions may vary in size but often coalesce and present in a distinctive “cockade” or rosette pattern with scalloped borders. Systemic manifestations are rare, but renal and joint involvement may occur.4 Despite the dramatic and sometimes extensive appearance of the dermatologic manifestations, patients with AHEI are usually not in significant distress.

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy may show leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial small vessels with infiltrations of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis.5 In most cases, immunofluorescence is negative for perivascular IgA deposition. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease resolves spontaneously. Recurrence is uncommon but may occur, and usually occurs early.

What is on the differential?

Kawasaki disease. Similar to AHEI, patients with Kawasaki disease also may present with facial and extremity edema. However, patients with Kawasaki disease appear sicker, have associated lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, and fever longer than 5 days. The lack of elevated inflammatory markers, acute-onset, classic dermatologic lesions, and nontoxic appearance in our patient rule out Kawasaki disease and make AHEI more likely.

IgA vasculitis/Henoch-Schönlein purpura. The distinction between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura is among the most challenging. AHEI commonly afflicts younger children ranging from 4 months to 2 years, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura occurs in older children from 3 to 6 years of age. Visceral involvement is rare in AHEI, but frequently presents in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with gastrointestinal and renal complications. Although our patient had both mild renal involvement and a distribution primarily on the buttocks and lower limbs, similar to the classic distribution of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the younger age and lack of gastrointestinal and arthritic manifestations make AHEI more likely.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood, mainly affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years. Like AHEI, Gianotti-Crosti is a self-limiting condition likely triggered by viral infection or immunization. However, Gianotti-Crosti is characterized by a papular rash that may last for several weeks. Neither AHEI nor Gianotti-Crosti are pruritic, but patients with Gianotti-Crosti tend to have either inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy. Our patient’s large, coalescing dusky red patches and edematous plaques without lymphadenopathy are more consistent with AHEI.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute, immune-mediated condition characterized by distinctive target-like lesions on the skin often accompanied by erosions or bullae. Unlike AHEI, erythema multiforme can involve the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae. Erythema multiforme is rare before the age of 4 years. Although the targetoid or annular purpuric configuration of erythema multiforme may present similarly to AHEI in some cases, the young age of our patient and the lack of mucosal involvement make AHEI more likely.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Kleinman is a pediatric dermatology research associate at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Kleinman has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Savino F et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):e149-e152.

2. Carboni E et al. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771. 2019 Oct 17.

3. Fiore E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):684-95.

4. Watanabe T and Sato Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1979-81.

5. Cunha DF et al. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(3):37-41.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis that typically affects children between 4 months and 2 years of age.1 Etiology is unknown but the majority of cases are preceded by infections, vaccinations, or certain medications.2

AHEI is a self-limited disease that runs a benign course with spontaneous resolution within days to 3 weeks.3 Classic presentation involves acute onset of fever, purpura, ecchymosis, and inflammatory edema. Edema is often the first sign, and may involve the face, ears, scrotum, or extremities. Hemorrhagic lesions may vary in size but often coalesce and present in a distinctive “cockade” or rosette pattern with scalloped borders. Systemic manifestations are rare, but renal and joint involvement may occur.4 Despite the dramatic and sometimes extensive appearance of the dermatologic manifestations, patients with AHEI are usually not in significant distress.

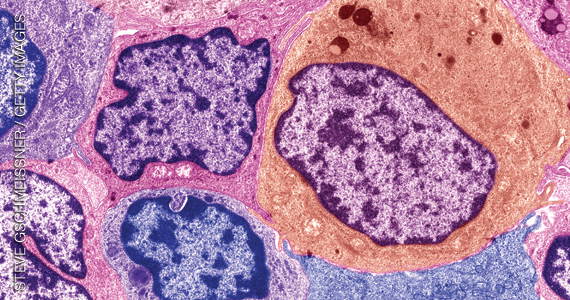

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy may show leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial small vessels with infiltrations of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis.5 In most cases, immunofluorescence is negative for perivascular IgA deposition. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease resolves spontaneously. Recurrence is uncommon but may occur, and usually occurs early.

What is on the differential?

Kawasaki disease. Similar to AHEI, patients with Kawasaki disease also may present with facial and extremity edema. However, patients with Kawasaki disease appear sicker, have associated lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, and fever longer than 5 days. The lack of elevated inflammatory markers, acute-onset, classic dermatologic lesions, and nontoxic appearance in our patient rule out Kawasaki disease and make AHEI more likely.

IgA vasculitis/Henoch-Schönlein purpura. The distinction between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura is among the most challenging. AHEI commonly afflicts younger children ranging from 4 months to 2 years, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura occurs in older children from 3 to 6 years of age. Visceral involvement is rare in AHEI, but frequently presents in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with gastrointestinal and renal complications. Although our patient had both mild renal involvement and a distribution primarily on the buttocks and lower limbs, similar to the classic distribution of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the younger age and lack of gastrointestinal and arthritic manifestations make AHEI more likely.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood, mainly affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years. Like AHEI, Gianotti-Crosti is a self-limiting condition likely triggered by viral infection or immunization. However, Gianotti-Crosti is characterized by a papular rash that may last for several weeks. Neither AHEI nor Gianotti-Crosti are pruritic, but patients with Gianotti-Crosti tend to have either inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy. Our patient’s large, coalescing dusky red patches and edematous plaques without lymphadenopathy are more consistent with AHEI.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute, immune-mediated condition characterized by distinctive target-like lesions on the skin often accompanied by erosions or bullae. Unlike AHEI, erythema multiforme can involve the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae. Erythema multiforme is rare before the age of 4 years. Although the targetoid or annular purpuric configuration of erythema multiforme may present similarly to AHEI in some cases, the young age of our patient and the lack of mucosal involvement make AHEI more likely.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Kleinman is a pediatric dermatology research associate at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Kleinman has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Savino F et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):e149-e152.

2. Carboni E et al. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771. 2019 Oct 17.

3. Fiore E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):684-95.

4. Watanabe T and Sato Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1979-81.

5. Cunha DF et al. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(3):37-41.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a leukocytoclastic vasculitis that typically affects children between 4 months and 2 years of age.1 Etiology is unknown but the majority of cases are preceded by infections, vaccinations, or certain medications.2

AHEI is a self-limited disease that runs a benign course with spontaneous resolution within days to 3 weeks.3 Classic presentation involves acute onset of fever, purpura, ecchymosis, and inflammatory edema. Edema is often the first sign, and may involve the face, ears, scrotum, or extremities. Hemorrhagic lesions may vary in size but often coalesce and present in a distinctive “cockade” or rosette pattern with scalloped borders. Systemic manifestations are rare, but renal and joint involvement may occur.4 Despite the dramatic and sometimes extensive appearance of the dermatologic manifestations, patients with AHEI are usually not in significant distress.

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy may show leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the superficial small vessels with infiltrations of neutrophils, extravasation of red blood cells, and fibrinoid necrosis.5 In most cases, immunofluorescence is negative for perivascular IgA deposition. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease resolves spontaneously. Recurrence is uncommon but may occur, and usually occurs early.

What is on the differential?

Kawasaki disease. Similar to AHEI, patients with Kawasaki disease also may present with facial and extremity edema. However, patients with Kawasaki disease appear sicker, have associated lymphadenopathy, conjunctivitis, and fever longer than 5 days. The lack of elevated inflammatory markers, acute-onset, classic dermatologic lesions, and nontoxic appearance in our patient rule out Kawasaki disease and make AHEI more likely.

IgA vasculitis/Henoch-Schönlein purpura. The distinction between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura is among the most challenging. AHEI commonly afflicts younger children ranging from 4 months to 2 years, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura occurs in older children from 3 to 6 years of age. Visceral involvement is rare in AHEI, but frequently presents in Henoch-Schönlein purpura with gastrointestinal and renal complications. Although our patient had both mild renal involvement and a distribution primarily on the buttocks and lower limbs, similar to the classic distribution of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, the younger age and lack of gastrointestinal and arthritic manifestations make AHEI more likely.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood, mainly affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years. Like AHEI, Gianotti-Crosti is a self-limiting condition likely triggered by viral infection or immunization. However, Gianotti-Crosti is characterized by a papular rash that may last for several weeks. Neither AHEI nor Gianotti-Crosti are pruritic, but patients with Gianotti-Crosti tend to have either inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy. Our patient’s large, coalescing dusky red patches and edematous plaques without lymphadenopathy are more consistent with AHEI.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute, immune-mediated condition characterized by distinctive target-like lesions on the skin often accompanied by erosions or bullae. Unlike AHEI, erythema multiforme can involve the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae. Erythema multiforme is rare before the age of 4 years. Although the targetoid or annular purpuric configuration of erythema multiforme may present similarly to AHEI in some cases, the young age of our patient and the lack of mucosal involvement make AHEI more likely.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Kleinman is a pediatric dermatology research associate at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Neither Dr. Matiz nor Ms. Kleinman has any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Savino F et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):e149-e152.

2. Carboni E et al. F1000Res. 2019;8:1771. 2019 Oct 17.

3. Fiore E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):684-95.

4. Watanabe T and Sato Y. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(11):1979-81.

5. Cunha DF et al. Autops Case Rep. 2015;5(3):37-41.

A 34-year-old male presented with 10 days of a pruritic rash

Less frequently observable infectious agents associated with EM are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Histoplasma capsulatum, and parapoxvirus (orf). Rarely, EM is triggered by drug eruption or systemic disease. Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by EM. However, it is predominantly observed in young adult patients (20-40 years of age), and there is a male predominance.

Patients typically present with the abrupt onset of symmetrical red papules that evolve into typical and atypical targetoid lesions. Lesions evolve in 48-72 hours, favoring acrofacial sites that then spread down towards the trunk. Systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia may accompany the skin lesions.1-3

Erythema multiforme is recognized in two forms: EM minor and EM major. Both forms share the same characteristic of target lesions. However, the presence of mucosal involvement distinguishes the two. Mucosal involvement is absent or mild in EM minor, while mucosal involvement in EM major is often severe.2,3 Painful bullous lesions are commonly present in the mouth, genital, and ocular mucous membranes. Severe symptoms can often result in difficulty eating and drinking.

Diagnosis is largely clinical. Further histologic study may accompany diagnoses to exclude differential diagnosis. In EM, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is negative. Histopathology reveals apoptosis of individual keratinocytes.1,2

Therapeutic treatment for painful bullous lesions in the mouth involve antiseptic rinses and anesthetic solutions. Preventive treatment for patients with HSV-associated EM recurrence includes oral acyclovir or valacyclovir.2

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. A DIF was negative, and a chest x-ray was negative. Treatment was initiated with oral acyclovir, doxycycline, and a prednisone taper. In addition, topical clobetasol propionate and magic mouthwash (Maalox/lidocaine/nystatin) was prescribed. The patient was placed on daily suppressive valacyclovir to prevent frequent recurrence of EM.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Pham, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Dr. Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Bilu-Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Hafsi W and Badri T. Erythema Multiforme, in “StatPearls [Internet].” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

3. Oakley A. Erythema Multiforme. DermNet NZ. 2015 Oct.

Less frequently observable infectious agents associated with EM are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Histoplasma capsulatum, and parapoxvirus (orf). Rarely, EM is triggered by drug eruption or systemic disease. Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by EM. However, it is predominantly observed in young adult patients (20-40 years of age), and there is a male predominance.

Patients typically present with the abrupt onset of symmetrical red papules that evolve into typical and atypical targetoid lesions. Lesions evolve in 48-72 hours, favoring acrofacial sites that then spread down towards the trunk. Systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia may accompany the skin lesions.1-3

Erythema multiforme is recognized in two forms: EM minor and EM major. Both forms share the same characteristic of target lesions. However, the presence of mucosal involvement distinguishes the two. Mucosal involvement is absent or mild in EM minor, while mucosal involvement in EM major is often severe.2,3 Painful bullous lesions are commonly present in the mouth, genital, and ocular mucous membranes. Severe symptoms can often result in difficulty eating and drinking.

Diagnosis is largely clinical. Further histologic study may accompany diagnoses to exclude differential diagnosis. In EM, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is negative. Histopathology reveals apoptosis of individual keratinocytes.1,2

Therapeutic treatment for painful bullous lesions in the mouth involve antiseptic rinses and anesthetic solutions. Preventive treatment for patients with HSV-associated EM recurrence includes oral acyclovir or valacyclovir.2

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. A DIF was negative, and a chest x-ray was negative. Treatment was initiated with oral acyclovir, doxycycline, and a prednisone taper. In addition, topical clobetasol propionate and magic mouthwash (Maalox/lidocaine/nystatin) was prescribed. The patient was placed on daily suppressive valacyclovir to prevent frequent recurrence of EM.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Pham, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Dr. Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Bilu-Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Hafsi W and Badri T. Erythema Multiforme, in “StatPearls [Internet].” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

3. Oakley A. Erythema Multiforme. DermNet NZ. 2015 Oct.

Less frequently observable infectious agents associated with EM are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Histoplasma capsulatum, and parapoxvirus (orf). Rarely, EM is triggered by drug eruption or systemic disease. Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by EM. However, it is predominantly observed in young adult patients (20-40 years of age), and there is a male predominance.

Patients typically present with the abrupt onset of symmetrical red papules that evolve into typical and atypical targetoid lesions. Lesions evolve in 48-72 hours, favoring acrofacial sites that then spread down towards the trunk. Systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia may accompany the skin lesions.1-3

Erythema multiforme is recognized in two forms: EM minor and EM major. Both forms share the same characteristic of target lesions. However, the presence of mucosal involvement distinguishes the two. Mucosal involvement is absent or mild in EM minor, while mucosal involvement in EM major is often severe.2,3 Painful bullous lesions are commonly present in the mouth, genital, and ocular mucous membranes. Severe symptoms can often result in difficulty eating and drinking.

Diagnosis is largely clinical. Further histologic study may accompany diagnoses to exclude differential diagnosis. In EM, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is negative. Histopathology reveals apoptosis of individual keratinocytes.1,2

Therapeutic treatment for painful bullous lesions in the mouth involve antiseptic rinses and anesthetic solutions. Preventive treatment for patients with HSV-associated EM recurrence includes oral acyclovir or valacyclovir.2

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. A DIF was negative, and a chest x-ray was negative. Treatment was initiated with oral acyclovir, doxycycline, and a prednisone taper. In addition, topical clobetasol propionate and magic mouthwash (Maalox/lidocaine/nystatin) was prescribed. The patient was placed on daily suppressive valacyclovir to prevent frequent recurrence of EM.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Pham, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Dr. Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Bilu-Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Hafsi W and Badri T. Erythema Multiforme, in “StatPearls [Internet].” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

3. Oakley A. Erythema Multiforme. DermNet NZ. 2015 Oct.

New hemophilia treatments: ‘Our cup runneth over’

It’s a problem many clinicians would love to have: A whole variety of new or emerging therapeutic options to use in the care of their patients.

In a session titled “Hemophilia Update: Our Cup Runneth Over,” presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, .

Factor concentrates

Prophylaxis – as opposed to episodic treatment – is the standard of care in the use of factor concentrates in patients with hemophilia, said Ming Y. Lim, MB BChir, from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“Effective prophylaxis is an ongoing collaborative effort that relies on shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician,” she told the audience.

As the complexity of therapeutic options, including gene therapy, continues to increase “it is critical that both patients and clinicians are actively involved in this collaborative process to optimize treatment and overall patient outcomes,” she added.

Historically, clinicians who treat patients with hemophilia aimed for trough levels of factor concentrates of at least 1% to prevent spontaneous joint bleeding. But as updated World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines now recommend, trough levels should be sufficient to prevent spontaneous bleeding based on the individual patient’s bleeding phenotype and activity levels, starting in the range between 3% and 5%, and going higher as necessary.

“The appropriate target trough level is that at which a person with hemophilia experiences zero bleeds while pursuing an active or sedentary lifestyle,” she said.

The choice of factor concentrates between standard and extended half-life products will depend on multiple factors, including availability, patient and provider preferences, cost, and access to assays for monitoring extended half-life products.

The prolonged action of extended half-life products translates into dosing twice per week or every 3 days for factor VIII concentrates, and every 7-14 days for factor IX concentrates.

“All available extended half-life products have been shown to be efficacious in the prevention and treatment of bleeds, with no evidence for any clinical safety issues,” Dr. Lim said.

There are theoretical concerns, however, regarding the lifelong use of PEGylated clotting factor concentrates, leading to some variations in the regulatory approval for some PEGylated product intended for bleeding prophylaxis in children with hemophilia, she noted.

The pharmacokinetics of prophylaxis with factor concentrates can vary according to age, body mass, blood type, and von Willebrand factor levels, so WFH guidelines recommend pharmacokinetic assessment of people with hemophilia for optimization of prophylaxis, she said.

Factor mimetic and rebalancing therapies

With the commercial availability of one factor mimetic for treatment of hemophilia A and with other factor mimetics and rebalancing therapies such as fitusiran in the works, it raises the question, “Is this the beginning of the end of the use of factor?” said Alice Ma, MD, FACP, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Factors that may determine the answer to that question include the convenience of subcutaneous administration of factor VIII mimetics compared with intravenous delivery of factor concentrates, relative cost of factors versus nonfactor products, and safety.

She reviewed the current state of alternatives to factor concentrates, including the factor mimetic emicizumab (Hemlibra), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for bleeding prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors, and is currently the only FDA-approved and licensed agent in its class.

Although emicizumab is widely regarded as a major advance, there are still unanswered clinical questions about its long-term use, Dr. Ma said. It is unknown, for example, whether it can prevent inhibitor development in previously untreated patients, and whether it can prevent intracranial hemorrhage in early years of life prior to the start of traditional prophylaxis.

It’s also unknown whether the factor VIII mimetic activity of emicizumab provides the same physiological benefits of coagulation factors, and the mechanism of thrombotic adverse events seen with this agent is still unclear, she added.

Other factor VIII mimetics in the pipeline include Mim8, which is being developed in Denmark by Novo Nordisk; this is a next-generation bispecific antibody with enhanced activity over emicizumab in both mouse models and in vitro hemophilia A assays. There are also two others bispecific antibodies designed to generate thrombin in preclinical development: BS-027125 (Bioverativ, U.S.) and NIBX-2101 (Takeda, Japan).

One of the most promising rebalancing factors in development is fitusiran, a small interfering RNA molecule that targets mRNA encoding antithrombin. As reported during ASH 2021, fitusiran was associated with an approximately 90% reduction in annualized bleeding rates in patients with hemophilia A and hemophilia B, both with inhibitors, in two clinical trials. It was described at the meeting “as a great leap forward” in the treatment of hemophilia.

However, during its clinical development fitusiran has been consistently associated with thrombotic complications, Dr. Ma noted.

Also in development are several drugs targeted against tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), an anticoagulant protein that inhibits early phases of the procoagulant response. These agents included marstacimab (Pfizer, U.S.) which has been reported to normalize coagulation in plasma from hemophilia patients ex vivo and is currently being evaluated in patients with hemophilia A and B. There is also MG1113 (Green Cross Corporation, South Korea), a monoclonal antibody currently being tested in healthy volunteers, and BAX499 (Takeda), an aptamer derived from recombinant human TFPI that has been shown to inhibit TFPI in vitro and in vivo. However, development of this agent is on hold due to bleeding in study subjects, Dr. Ma noted.

“It is really notable that none of the replacements of factor have been free of thrombotic side effects,” Dr. Ma said. “And so I think it shows that you mess with Mother Nature at your peril. If you poke at the hemostasis-thrombosis arm and reduce antithrombotic proteins, and something triggers bleeding and you start to treat with a therapy for hemorrhage, it’s not a surprise that the first patient treated with fitusiran had a thrombosis, and I think we were just not potentially savvy enough to predict that.”

Considerable optimism over gene therapy

“There is now repeated proof of concept success for hemophilia A and B gene therapy. I think this supports the considerable optimism that’s really driving this field,” said Lindsey A. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

She reviewed adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector and AAV-mediated gene transfer approaches for hemophilia A and B.

There are currently four clinical trials of gene therapy for patients with hemophilia B, and five for patients with hemophilia A.

Because AAV efficiently targets the liver, most safety considerations about systemic AAV-mediated gene therapy are focused around potential hepatotoxicity, Dr. George said.

“Thankfully, short-term safety in the context of hemophilia has really been quite good,” she said.

Patients who undergo gene therapy for hemophilia are typically monitored twice weekly for 3 months for evidence of a capsid-specific CD8 T cell response, also called a capsid immune response. This presents with transient transaminase elevations (primarily ALT) and a decline in factor VIII and factor IX activity.

In clinical trials for patients with hemophilia, the capsid immune response has limited the efficacy of the therapy in the short term, but has not been a major cause for safety concerns. It is typically managed with glucocorticoids or other immunomodulating agents such as mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus.

There have also been reported cases of transaminase elevations without evidence of a capsid immune response, which warrants further investigation, she added.

Regarding efficacy, she noted that across clinical trials, the observed annualized bleeding rate has been less than 1%, despite heterogeneity of vectors and dosing used.

“That’s obviously quite optimistic for the field, but it also sort of raises the point that the heterogeneity at which we’re achieving the same phenotypic observations deserves a bit of a deeper dive,” she said.

Although hemophilia B gene transfer appears to be durable, the same cannot be said as yet for hemophilia A.

In canine models for hemophilia A and B, factor VIII and factor IX expression have been demonstrated for 8-10 years post vector, and in humans factor IX expression in patients with hemophilia B has been reported for up to 8 years.

In contrast, in the three hemophilia A trials in which patients have been followed for a minimum of 2 years, there was an approximately 40% loss of transgene vector from year 1 to year 2 with two vectors, but not a third.

Potential explanations for the loss of expression seen include an unfolded protein response, promoter silence, and an ongoing undetected or unmitigated immune response to AAV or to the transgene.

Regarding the future of gene therapy, Dr. George said that “we anticipate that there will be licensed vectors in the very near future, and predicted that gene therapy “will fulfill its promise to alter the paradigm of hemophilia care.”

Dr. Lim disclosed honoraria from several companies and travel support from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Ma disclosed honoraria and research funding from Takeda. Dr. George disclosed FVIII-QQ patents and royalties, research funding from AskBio, and consulting activities/advisory board participation with others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a problem many clinicians would love to have: A whole variety of new or emerging therapeutic options to use in the care of their patients.

In a session titled “Hemophilia Update: Our Cup Runneth Over,” presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, .

Factor concentrates

Prophylaxis – as opposed to episodic treatment – is the standard of care in the use of factor concentrates in patients with hemophilia, said Ming Y. Lim, MB BChir, from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“Effective prophylaxis is an ongoing collaborative effort that relies on shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician,” she told the audience.

As the complexity of therapeutic options, including gene therapy, continues to increase “it is critical that both patients and clinicians are actively involved in this collaborative process to optimize treatment and overall patient outcomes,” she added.

Historically, clinicians who treat patients with hemophilia aimed for trough levels of factor concentrates of at least 1% to prevent spontaneous joint bleeding. But as updated World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines now recommend, trough levels should be sufficient to prevent spontaneous bleeding based on the individual patient’s bleeding phenotype and activity levels, starting in the range between 3% and 5%, and going higher as necessary.

“The appropriate target trough level is that at which a person with hemophilia experiences zero bleeds while pursuing an active or sedentary lifestyle,” she said.

The choice of factor concentrates between standard and extended half-life products will depend on multiple factors, including availability, patient and provider preferences, cost, and access to assays for monitoring extended half-life products.

The prolonged action of extended half-life products translates into dosing twice per week or every 3 days for factor VIII concentrates, and every 7-14 days for factor IX concentrates.

“All available extended half-life products have been shown to be efficacious in the prevention and treatment of bleeds, with no evidence for any clinical safety issues,” Dr. Lim said.

There are theoretical concerns, however, regarding the lifelong use of PEGylated clotting factor concentrates, leading to some variations in the regulatory approval for some PEGylated product intended for bleeding prophylaxis in children with hemophilia, she noted.

The pharmacokinetics of prophylaxis with factor concentrates can vary according to age, body mass, blood type, and von Willebrand factor levels, so WFH guidelines recommend pharmacokinetic assessment of people with hemophilia for optimization of prophylaxis, she said.

Factor mimetic and rebalancing therapies

With the commercial availability of one factor mimetic for treatment of hemophilia A and with other factor mimetics and rebalancing therapies such as fitusiran in the works, it raises the question, “Is this the beginning of the end of the use of factor?” said Alice Ma, MD, FACP, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Factors that may determine the answer to that question include the convenience of subcutaneous administration of factor VIII mimetics compared with intravenous delivery of factor concentrates, relative cost of factors versus nonfactor products, and safety.

She reviewed the current state of alternatives to factor concentrates, including the factor mimetic emicizumab (Hemlibra), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for bleeding prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors, and is currently the only FDA-approved and licensed agent in its class.

Although emicizumab is widely regarded as a major advance, there are still unanswered clinical questions about its long-term use, Dr. Ma said. It is unknown, for example, whether it can prevent inhibitor development in previously untreated patients, and whether it can prevent intracranial hemorrhage in early years of life prior to the start of traditional prophylaxis.

It’s also unknown whether the factor VIII mimetic activity of emicizumab provides the same physiological benefits of coagulation factors, and the mechanism of thrombotic adverse events seen with this agent is still unclear, she added.

Other factor VIII mimetics in the pipeline include Mim8, which is being developed in Denmark by Novo Nordisk; this is a next-generation bispecific antibody with enhanced activity over emicizumab in both mouse models and in vitro hemophilia A assays. There are also two others bispecific antibodies designed to generate thrombin in preclinical development: BS-027125 (Bioverativ, U.S.) and NIBX-2101 (Takeda, Japan).

One of the most promising rebalancing factors in development is fitusiran, a small interfering RNA molecule that targets mRNA encoding antithrombin. As reported during ASH 2021, fitusiran was associated with an approximately 90% reduction in annualized bleeding rates in patients with hemophilia A and hemophilia B, both with inhibitors, in two clinical trials. It was described at the meeting “as a great leap forward” in the treatment of hemophilia.

However, during its clinical development fitusiran has been consistently associated with thrombotic complications, Dr. Ma noted.

Also in development are several drugs targeted against tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), an anticoagulant protein that inhibits early phases of the procoagulant response. These agents included marstacimab (Pfizer, U.S.) which has been reported to normalize coagulation in plasma from hemophilia patients ex vivo and is currently being evaluated in patients with hemophilia A and B. There is also MG1113 (Green Cross Corporation, South Korea), a monoclonal antibody currently being tested in healthy volunteers, and BAX499 (Takeda), an aptamer derived from recombinant human TFPI that has been shown to inhibit TFPI in vitro and in vivo. However, development of this agent is on hold due to bleeding in study subjects, Dr. Ma noted.

“It is really notable that none of the replacements of factor have been free of thrombotic side effects,” Dr. Ma said. “And so I think it shows that you mess with Mother Nature at your peril. If you poke at the hemostasis-thrombosis arm and reduce antithrombotic proteins, and something triggers bleeding and you start to treat with a therapy for hemorrhage, it’s not a surprise that the first patient treated with fitusiran had a thrombosis, and I think we were just not potentially savvy enough to predict that.”

Considerable optimism over gene therapy

“There is now repeated proof of concept success for hemophilia A and B gene therapy. I think this supports the considerable optimism that’s really driving this field,” said Lindsey A. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

She reviewed adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector and AAV-mediated gene transfer approaches for hemophilia A and B.

There are currently four clinical trials of gene therapy for patients with hemophilia B, and five for patients with hemophilia A.

Because AAV efficiently targets the liver, most safety considerations about systemic AAV-mediated gene therapy are focused around potential hepatotoxicity, Dr. George said.

“Thankfully, short-term safety in the context of hemophilia has really been quite good,” she said.

Patients who undergo gene therapy for hemophilia are typically monitored twice weekly for 3 months for evidence of a capsid-specific CD8 T cell response, also called a capsid immune response. This presents with transient transaminase elevations (primarily ALT) and a decline in factor VIII and factor IX activity.

In clinical trials for patients with hemophilia, the capsid immune response has limited the efficacy of the therapy in the short term, but has not been a major cause for safety concerns. It is typically managed with glucocorticoids or other immunomodulating agents such as mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus.

There have also been reported cases of transaminase elevations without evidence of a capsid immune response, which warrants further investigation, she added.

Regarding efficacy, she noted that across clinical trials, the observed annualized bleeding rate has been less than 1%, despite heterogeneity of vectors and dosing used.

“That’s obviously quite optimistic for the field, but it also sort of raises the point that the heterogeneity at which we’re achieving the same phenotypic observations deserves a bit of a deeper dive,” she said.

Although hemophilia B gene transfer appears to be durable, the same cannot be said as yet for hemophilia A.

In canine models for hemophilia A and B, factor VIII and factor IX expression have been demonstrated for 8-10 years post vector, and in humans factor IX expression in patients with hemophilia B has been reported for up to 8 years.

In contrast, in the three hemophilia A trials in which patients have been followed for a minimum of 2 years, there was an approximately 40% loss of transgene vector from year 1 to year 2 with two vectors, but not a third.

Potential explanations for the loss of expression seen include an unfolded protein response, promoter silence, and an ongoing undetected or unmitigated immune response to AAV or to the transgene.

Regarding the future of gene therapy, Dr. George said that “we anticipate that there will be licensed vectors in the very near future, and predicted that gene therapy “will fulfill its promise to alter the paradigm of hemophilia care.”

Dr. Lim disclosed honoraria from several companies and travel support from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Ma disclosed honoraria and research funding from Takeda. Dr. George disclosed FVIII-QQ patents and royalties, research funding from AskBio, and consulting activities/advisory board participation with others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a problem many clinicians would love to have: A whole variety of new or emerging therapeutic options to use in the care of their patients.

In a session titled “Hemophilia Update: Our Cup Runneth Over,” presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, .

Factor concentrates

Prophylaxis – as opposed to episodic treatment – is the standard of care in the use of factor concentrates in patients with hemophilia, said Ming Y. Lim, MB BChir, from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“Effective prophylaxis is an ongoing collaborative effort that relies on shared decision-making between the patient and the clinician,” she told the audience.

As the complexity of therapeutic options, including gene therapy, continues to increase “it is critical that both patients and clinicians are actively involved in this collaborative process to optimize treatment and overall patient outcomes,” she added.

Historically, clinicians who treat patients with hemophilia aimed for trough levels of factor concentrates of at least 1% to prevent spontaneous joint bleeding. But as updated World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines now recommend, trough levels should be sufficient to prevent spontaneous bleeding based on the individual patient’s bleeding phenotype and activity levels, starting in the range between 3% and 5%, and going higher as necessary.

“The appropriate target trough level is that at which a person with hemophilia experiences zero bleeds while pursuing an active or sedentary lifestyle,” she said.

The choice of factor concentrates between standard and extended half-life products will depend on multiple factors, including availability, patient and provider preferences, cost, and access to assays for monitoring extended half-life products.

The prolonged action of extended half-life products translates into dosing twice per week or every 3 days for factor VIII concentrates, and every 7-14 days for factor IX concentrates.

“All available extended half-life products have been shown to be efficacious in the prevention and treatment of bleeds, with no evidence for any clinical safety issues,” Dr. Lim said.

There are theoretical concerns, however, regarding the lifelong use of PEGylated clotting factor concentrates, leading to some variations in the regulatory approval for some PEGylated product intended for bleeding prophylaxis in children with hemophilia, she noted.

The pharmacokinetics of prophylaxis with factor concentrates can vary according to age, body mass, blood type, and von Willebrand factor levels, so WFH guidelines recommend pharmacokinetic assessment of people with hemophilia for optimization of prophylaxis, she said.

Factor mimetic and rebalancing therapies

With the commercial availability of one factor mimetic for treatment of hemophilia A and with other factor mimetics and rebalancing therapies such as fitusiran in the works, it raises the question, “Is this the beginning of the end of the use of factor?” said Alice Ma, MD, FACP, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Factors that may determine the answer to that question include the convenience of subcutaneous administration of factor VIII mimetics compared with intravenous delivery of factor concentrates, relative cost of factors versus nonfactor products, and safety.

She reviewed the current state of alternatives to factor concentrates, including the factor mimetic emicizumab (Hemlibra), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for bleeding prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia A with inhibitors, and is currently the only FDA-approved and licensed agent in its class.

Although emicizumab is widely regarded as a major advance, there are still unanswered clinical questions about its long-term use, Dr. Ma said. It is unknown, for example, whether it can prevent inhibitor development in previously untreated patients, and whether it can prevent intracranial hemorrhage in early years of life prior to the start of traditional prophylaxis.

It’s also unknown whether the factor VIII mimetic activity of emicizumab provides the same physiological benefits of coagulation factors, and the mechanism of thrombotic adverse events seen with this agent is still unclear, she added.

Other factor VIII mimetics in the pipeline include Mim8, which is being developed in Denmark by Novo Nordisk; this is a next-generation bispecific antibody with enhanced activity over emicizumab in both mouse models and in vitro hemophilia A assays. There are also two others bispecific antibodies designed to generate thrombin in preclinical development: BS-027125 (Bioverativ, U.S.) and NIBX-2101 (Takeda, Japan).

One of the most promising rebalancing factors in development is fitusiran, a small interfering RNA molecule that targets mRNA encoding antithrombin. As reported during ASH 2021, fitusiran was associated with an approximately 90% reduction in annualized bleeding rates in patients with hemophilia A and hemophilia B, both with inhibitors, in two clinical trials. It was described at the meeting “as a great leap forward” in the treatment of hemophilia.

However, during its clinical development fitusiran has been consistently associated with thrombotic complications, Dr. Ma noted.

Also in development are several drugs targeted against tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), an anticoagulant protein that inhibits early phases of the procoagulant response. These agents included marstacimab (Pfizer, U.S.) which has been reported to normalize coagulation in plasma from hemophilia patients ex vivo and is currently being evaluated in patients with hemophilia A and B. There is also MG1113 (Green Cross Corporation, South Korea), a monoclonal antibody currently being tested in healthy volunteers, and BAX499 (Takeda), an aptamer derived from recombinant human TFPI that has been shown to inhibit TFPI in vitro and in vivo. However, development of this agent is on hold due to bleeding in study subjects, Dr. Ma noted.

“It is really notable that none of the replacements of factor have been free of thrombotic side effects,” Dr. Ma said. “And so I think it shows that you mess with Mother Nature at your peril. If you poke at the hemostasis-thrombosis arm and reduce antithrombotic proteins, and something triggers bleeding and you start to treat with a therapy for hemorrhage, it’s not a surprise that the first patient treated with fitusiran had a thrombosis, and I think we were just not potentially savvy enough to predict that.”

Considerable optimism over gene therapy

“There is now repeated proof of concept success for hemophilia A and B gene therapy. I think this supports the considerable optimism that’s really driving this field,” said Lindsey A. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

She reviewed adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector and AAV-mediated gene transfer approaches for hemophilia A and B.

There are currently four clinical trials of gene therapy for patients with hemophilia B, and five for patients with hemophilia A.

Because AAV efficiently targets the liver, most safety considerations about systemic AAV-mediated gene therapy are focused around potential hepatotoxicity, Dr. George said.

“Thankfully, short-term safety in the context of hemophilia has really been quite good,” she said.

Patients who undergo gene therapy for hemophilia are typically monitored twice weekly for 3 months for evidence of a capsid-specific CD8 T cell response, also called a capsid immune response. This presents with transient transaminase elevations (primarily ALT) and a decline in factor VIII and factor IX activity.

In clinical trials for patients with hemophilia, the capsid immune response has limited the efficacy of the therapy in the short term, but has not been a major cause for safety concerns. It is typically managed with glucocorticoids or other immunomodulating agents such as mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus.

There have also been reported cases of transaminase elevations without evidence of a capsid immune response, which warrants further investigation, she added.

Regarding efficacy, she noted that across clinical trials, the observed annualized bleeding rate has been less than 1%, despite heterogeneity of vectors and dosing used.

“That’s obviously quite optimistic for the field, but it also sort of raises the point that the heterogeneity at which we’re achieving the same phenotypic observations deserves a bit of a deeper dive,” she said.

Although hemophilia B gene transfer appears to be durable, the same cannot be said as yet for hemophilia A.

In canine models for hemophilia A and B, factor VIII and factor IX expression have been demonstrated for 8-10 years post vector, and in humans factor IX expression in patients with hemophilia B has been reported for up to 8 years.

In contrast, in the three hemophilia A trials in which patients have been followed for a minimum of 2 years, there was an approximately 40% loss of transgene vector from year 1 to year 2 with two vectors, but not a third.

Potential explanations for the loss of expression seen include an unfolded protein response, promoter silence, and an ongoing undetected or unmitigated immune response to AAV or to the transgene.

Regarding the future of gene therapy, Dr. George said that “we anticipate that there will be licensed vectors in the very near future, and predicted that gene therapy “will fulfill its promise to alter the paradigm of hemophilia care.”

Dr. Lim disclosed honoraria from several companies and travel support from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Ma disclosed honoraria and research funding from Takeda. Dr. George disclosed FVIII-QQ patents and royalties, research funding from AskBio, and consulting activities/advisory board participation with others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2021

Late-onset recurrence in breast cancer: Implications for women’s health clinicians in survivorship care

Improved treatments for breast cancer (BC) and effective screening programs have resulted in a BC mortality rate reduction of 41% since 1989.1 Because BC is the leading cause of cancer in women, these mortality improvements have resulted in more than 3 million BC survivors in the United States.2,3 With longer-term survival, there is increasing interest in late-onset recurrences.4,5 A recent study has provided an improved understanding of the risk of lateonset recurrence in women with 10 years of disease-free survival, an important finding for women’s health providers because oncologists do not typically follow survivors after 10 years of disease-free survival.4

Recent study looks at incidence of late-onset recurrence

Pederson and colleagues evaluated all patients diagnosed with BC in Denmark from 1987 through 2004.4 Those patients without evidence of recurrence at 10 years were then followed utilizing population-based linked registries to identify patients who subsequently developed a local, regional, or distant late-onset recurrence. The authors evaluated the frequency of late recurrence and identified associations with demographic and tumor characteristics.

What they found

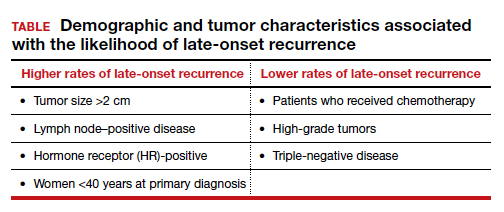

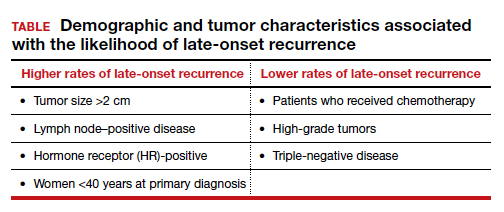

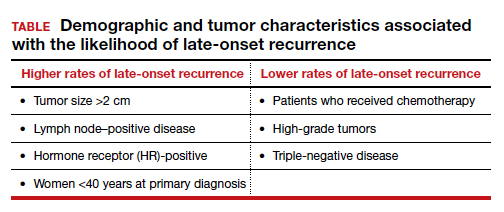

A total of 36,920 patients were diagnosed with BC in Denmark between 1987-2004, of whom 20,315 (55%) were identified as disease free for at least 10 years. Late-onset recurrence occurred in 2,595 (12.8%) with the strongest associations of recurrence seen in patients who had a tumor size >2 cm and lymph node‒positive (involving 4 or more nodes) disease (24.6%), compared with 12.7% in patients with tumors <2 cm and node-negative disease. Several other factors were associated with a higher risk of late-onset recurrence and are included in the TABLE. Half of the recurrences occurred between 10 and 15 years after the primary diagnosis.

Prior research

These findings are consistent with another recent study showing that BC patients have a 1% to 2%/year risk of recurrence after 10 disease-free years.5 Strengths of this study include:

- population-based, including all women with BC

- long-term follow-up for up to 32 years

- universal health care in Denmark, which results in robust and linked databases and very few missing data points.

There were two notable weaknesses to consider:

- Treatment regimens changed considerably during the time frame of the study (1997-2018), particularly the duration of tamoxifen use in patients with HR-positive disease. In this study nearly all patients received 5 years or less of tamoxifen. Since the mid-2010s, 10 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy has become routine in HR-positive BC, which reduces recurrences, including late-onset recurrence.6 The effect of 10 years of tamoxifen would very likely have resulted in less late-onset recurrence in the HR-positive population in this study.

- There is a lack of racial diversity in the Danish population, and the study findings may not translate to Black patients who have a higher frequency of triple-negative BC with a different risk of late-onset recurrence.7