User login

Fungating Mass on the Abdominal Wall

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Carcinoma

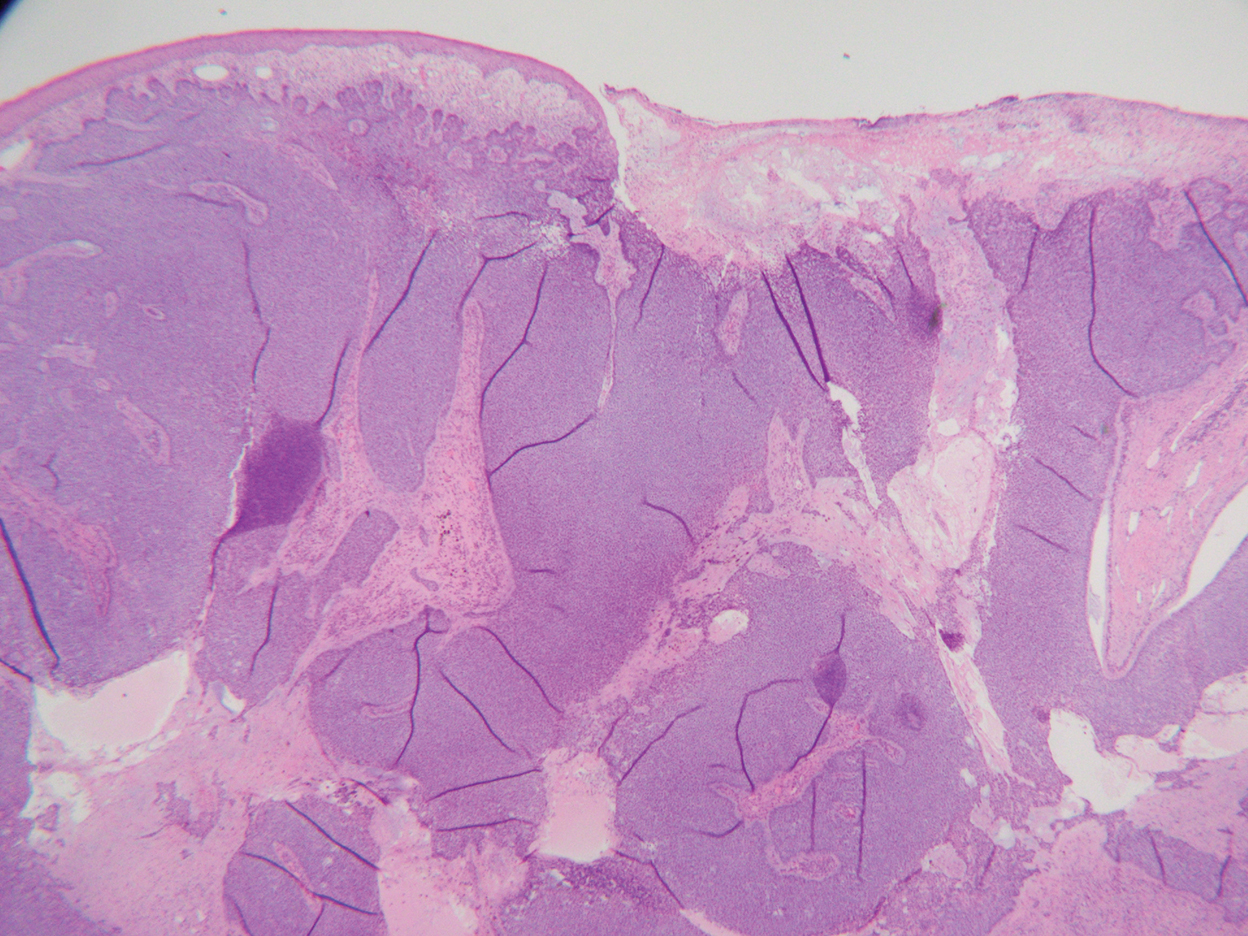

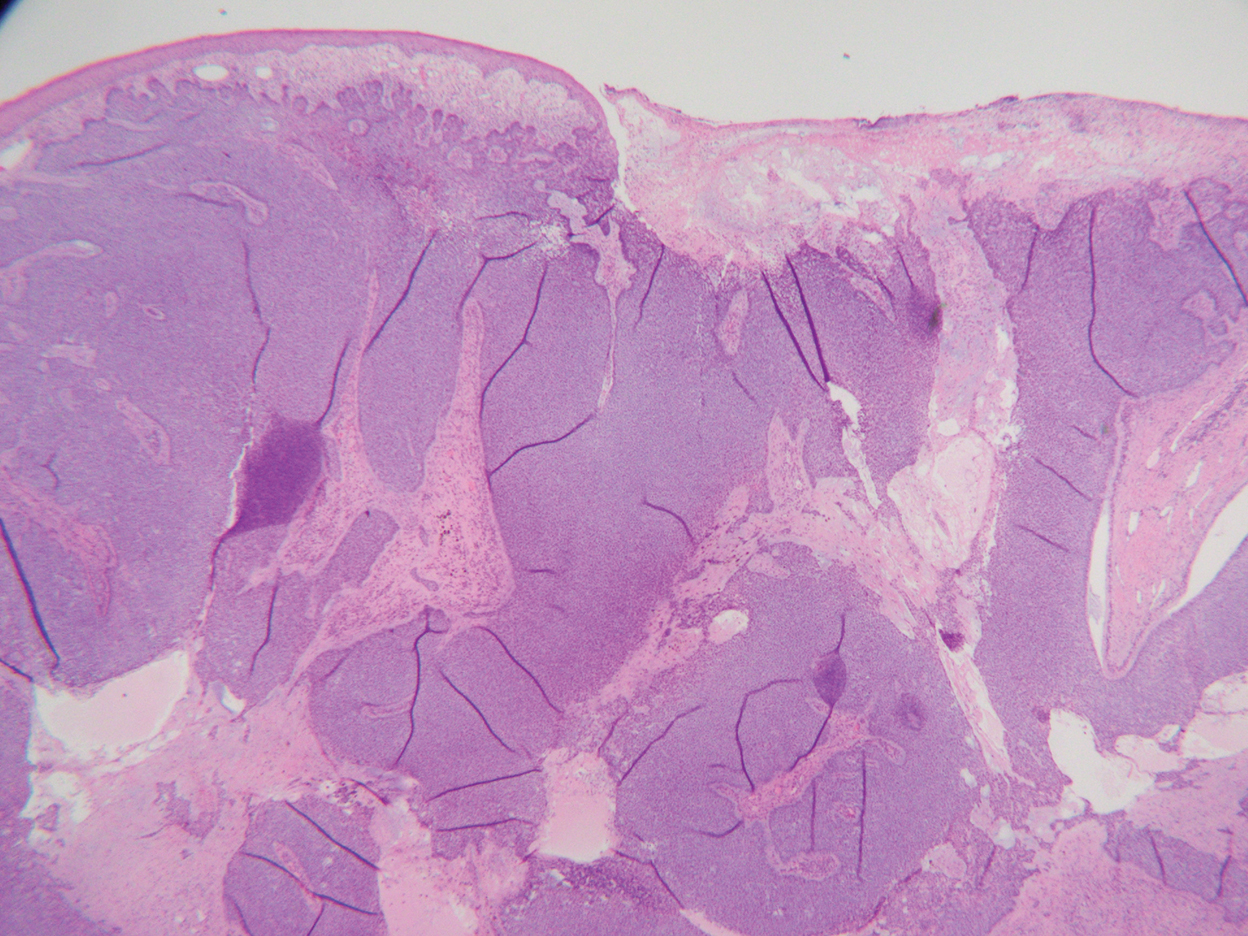

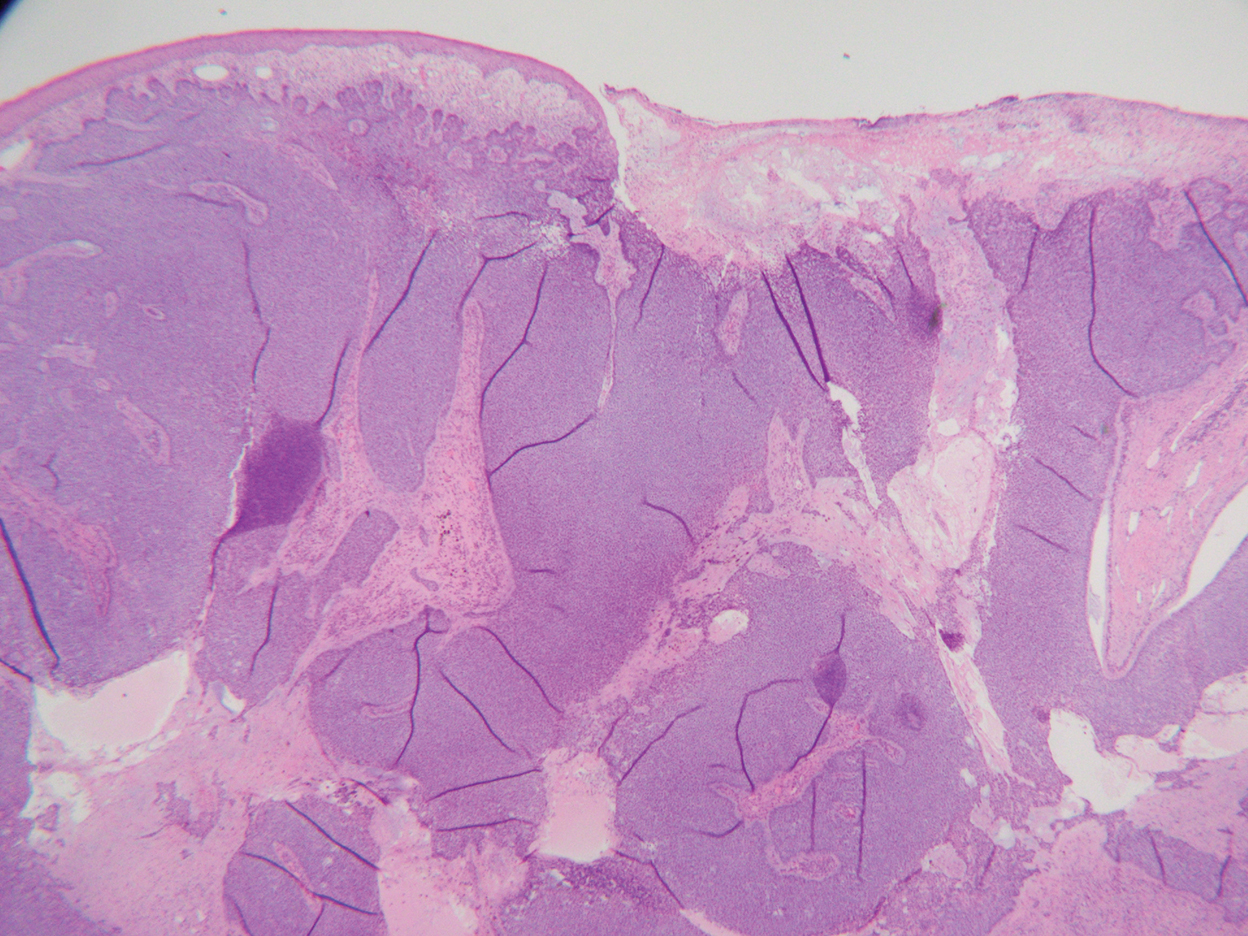

Histopathology was consistent with fungating basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The nodules were comprised of syncytial basaloid cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, numerous mitotic figures, fibromyxoid stroma, and peripheral nuclear palisading (Figure). Fortunately, no perineural or lymphovascular invasion was identified, and the margins of the specimen were negative. Despite the high-risk nature of giant BCC, the mass was solitary without notable local invasion, leaving it amendable to surgery. On follow-up, the patient has remained recurrence free, and her hemoglobin level has since stabilized.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy worldwide, and BCC accounts for more than 80% of nonmelanoma skin cancers in the United States. The incidence is on the rise due to the aging population and increasing cumulative skin exposure.1 Risk factors include both individual physical characteristics and environmental exposures. Individuals with lighter skin tones, red and blonde hair, and blue and green eyes are at an increased risk.2 UV radiation exposure is the most important cause of BCC.3 Chronic immunosuppression and exposure to arsenic, ionizing radiation, and psoralen plus UVA radiation also have been linked to the development of BCC.4-6 Basal cell carcinomas most commonly arise on sun-exposed areas such as the face, though more than 10% of cases appear on the trunk.7 Lesions characteristically remain localized, and growth rate is variable; however, when left untreated, BCCs have the potential to become locally destructive and difficult to treat.

Advanced BCCs are tumors that penetrate deeply into the skin. They often are not amenable to traditional therapy and/ or metastasize. Those that grow to a diameter greater than 5 cm, as in our patient, are known as giant BCCs. Only 0.5% to 1% of BCCs are giant BCCs8 ; they typically are more aggressive in nature with higher rates of local recurrence and metastasis. Individuals who develop giant BCCs either have had a delay in access to medical care or a history of BCC that was inadequately managed.9,10 During the COVID-19 pandemic, patient access to health care was substantially impacted during lockdowns. As in our patient, skin neoplasms and other medical conditions may present in later stages due to medical neglect.11,12 Metastasis is rare, even in advanced BCCs. A review of the literature from 1984 estimated that the incidence of metastasis of BCCs is 1 in 1000 to 35,000. Metastasis portends a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of 8 to 14 months.13 An updated review in 2013 found similar outcomes.14

The choice of management for BCCs depends on the risk for recurrence as well as individual patient factors. Characteristics such as tumor size, location, histology, whether it is a primary or recurrent lesion, and the presence of chronic skin disease determine the recurrence rate.15 The management of advanced BCCs often requires a multidisciplinary approach, as these neoplasms may not be amenable to local therapy without causing substantial morbidity. Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice for BCCs at high risk for recurrence.16 Standard surgical excision with postoperative margin assessment is acceptable when Mohs micrographic surgery is not available.17 Radiation therapy is an alternative for patients who are not candidates for surgery.18

Recently, improved understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of BCCs has led to the development of novel systemic therapies. The Hedgehog signaling pathway has been found to play a critical role in the development of most BCCs.19 Vismodegib and sonidegib are small-molecule inhibitors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway approved for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic BCCs that are not amenable to surgery or radiation. Approximately 50% of advanced BCCs respond to these therapies; however, long-term treatment may be limited by intolerable side effects and the development of resistance.20 Basal cell carcinomas that spread to lymph nodes or distant sites are treated with traditional systemic therapy. Historically, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapies, such as platinum-containing regimens, were employed with limited benefit and notable morbidity.21

The differential diagnosis for our patient included several other cutaneous neoplasms. Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common type of skin cancer. Similar to BCC, it can reach a substantial size if left untreated. Risk factors include chronic inflammation, exposure to radiation or chemical carcinogens, burns, human papillomavirus, and other chronic infections. Giant squamous cell carcinomas have high malignant potential and require imaging to assess the extent of invasion and for metastasis. Surgery typically is necessary for both staging and treatment. Adjuvant therapy also may be necessary.22,23

Internal malignant neoplasms rarely present as cutaneous metastases. Breast cancer, melanoma, and cancers of the upper respiratory tract most frequently metastasize to the skin. Although colorectal cancer (CRC) rarely metastasizes to the skin, it is an important cause of cutaneous metastasis due to its high incidence in the general population. When it does spread to the skin, CRC preferentially affects the abdominal wall. Lesions typically resemble the primary tumor but may appear anaplastic. The occurrence of cutaneous metastasis suggests latestage disease and carries a poor prognosis.24

Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma are aggressive skin cancers with high mortality rates. The former is rarer but more lethal. Merkel cell carcinomas typically occur in elderly white men on sun-exposed areas of the skin. Tumors present as asymptomatic, rapidly expanding, blue-red, firm nodules. Immunosuppression and UV light exposure are notable risk factors.25 Of the 4 major subtypes of cutaneous melanoma, superficial spreading is the most common, followed by nodular, lentigo maligna, and acral lentiginous.26 Superficial spreading melanoma characteristically presents as an expanding asymmetric macule or thin plaque with irregular borders and variation in size and color (black, brown, or red). Nodular melanoma usually presents as symmetric in shape and color (amelanotic, black, or brown). Early recognition by both the patient and clinician is essential in preventing tumor growth and progression.27

Our patient’s presentation was highly concerning for cutaneous metastasis given her history of CRC. Furthermore, the finding of severe anemia was atypical for skin cancer and more characteristic of the prior malignancy. Imaging revealed a locally confined mass with no evidence of extension, lymph node involvement, or additional lesions. The diagnosis was clinched with histopathologic examination.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Lear JT, Tan BB, Smith AG, et al. Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma in the UK: case-control study in 806 patients. J R Soc Med. 1997; 90:371-374.

- Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer: I. basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-163.

- Guo HR, Yu HS, Hu H, et al. Arsenic in drinking water and skin cancers: cell-type specificity (Taiwan, ROC). Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:909-916.

- Lichter MD, Karagas MR, Mott LA, et al; The New Hampshire Skin Cancer Study Group. Therapeutic ionizing radiation and the incidence of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1007-1011.

- Nijsten TEC, Stern RS. The increased risk of skin cancer is persistent after discontinuation of psoralen plus ultraviolet A: a cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:252-258.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Gualdi G, Monari P, Calzavara‐Pinton P, et al. When basal cell carcinomas became giant: an Italian multicenter study. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:377-382.

- Randle HW, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Giant basal cell carcinoma (T3). who is at risk? Cancer. 1993;72:1624-1630.

- Archontaki M, Stavrianos SD, Korkolis DP, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis of 51 cases and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2655-2663.

- Shifat Ahmed SAK, Ajisola M, Azeem K, et al. Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre-COVID and COVID-19 lockdown ssstakeholder engagements. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:E003042.

- Gomolin T, Cline A, Handler MZ. The danger of neglecting melanoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:444-445.

- von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma. report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043-1060.

- Wysong A, Aasi SZ, Tang JY. Update on metastatic basal cell carcinoma: a summary of published cases from 1981 through 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:615-616.

- Bøgelund FS, Philipsen PA, Gniadecki R. Factors affecting the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:330-334.

- Mosterd K, Krekels GAM, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

- Wetzig T, Woitek M, Eichhorn K, et al. Surgical excision of basal cell carcinoma with complete margin control: outcome at 5-year follow-up. Dermatology. 2010;220:363-369.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Gladstein AH, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. part 4: X-ray therapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:549-554.

- Tanese K, Emoto K, Kubota N, et al. Immunohistochemical visualization of the signature of activated Hedgehog signaling pathway in cutaneous epithelial tumors. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1181-1186.

- Basset-Séguin N, Hauschild A, Kunstfeld R, et al. Vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: primary analysis of STEVIE, an international, open-label trial. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:334-348.

- Carneiro BA, Watkin WG, Mehta UK, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: complete response to chemotherapy and associated pure red cell aplasia. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:396-400.

- Misiakos EP, Damaskou V, Koumarianou A, et al. A giant squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:136.

- Wollina U, Bayyoud Y, Krönert C, et al. Giant epithelial malignancies (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma): a series of 20 tumors from a single center. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:12-19.

- Bittencourt MJS, Imbiriba AA, Oliveira OA, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of colorectal cancer. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:884-886.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Buettner PG, Leiter U, Eigentler TK, et al. Development of prognostic factors and survival in cutaneous melanoma over 25 years: an analysis of the Central Malignant Melanoma Registry of the German Dermatological Society. Cancer. 2005;103:616-624.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 80:178-188.e3.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology was consistent with fungating basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The nodules were comprised of syncytial basaloid cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, numerous mitotic figures, fibromyxoid stroma, and peripheral nuclear palisading (Figure). Fortunately, no perineural or lymphovascular invasion was identified, and the margins of the specimen were negative. Despite the high-risk nature of giant BCC, the mass was solitary without notable local invasion, leaving it amendable to surgery. On follow-up, the patient has remained recurrence free, and her hemoglobin level has since stabilized.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy worldwide, and BCC accounts for more than 80% of nonmelanoma skin cancers in the United States. The incidence is on the rise due to the aging population and increasing cumulative skin exposure.1 Risk factors include both individual physical characteristics and environmental exposures. Individuals with lighter skin tones, red and blonde hair, and blue and green eyes are at an increased risk.2 UV radiation exposure is the most important cause of BCC.3 Chronic immunosuppression and exposure to arsenic, ionizing radiation, and psoralen plus UVA radiation also have been linked to the development of BCC.4-6 Basal cell carcinomas most commonly arise on sun-exposed areas such as the face, though more than 10% of cases appear on the trunk.7 Lesions characteristically remain localized, and growth rate is variable; however, when left untreated, BCCs have the potential to become locally destructive and difficult to treat.

Advanced BCCs are tumors that penetrate deeply into the skin. They often are not amenable to traditional therapy and/ or metastasize. Those that grow to a diameter greater than 5 cm, as in our patient, are known as giant BCCs. Only 0.5% to 1% of BCCs are giant BCCs8 ; they typically are more aggressive in nature with higher rates of local recurrence and metastasis. Individuals who develop giant BCCs either have had a delay in access to medical care or a history of BCC that was inadequately managed.9,10 During the COVID-19 pandemic, patient access to health care was substantially impacted during lockdowns. As in our patient, skin neoplasms and other medical conditions may present in later stages due to medical neglect.11,12 Metastasis is rare, even in advanced BCCs. A review of the literature from 1984 estimated that the incidence of metastasis of BCCs is 1 in 1000 to 35,000. Metastasis portends a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of 8 to 14 months.13 An updated review in 2013 found similar outcomes.14

The choice of management for BCCs depends on the risk for recurrence as well as individual patient factors. Characteristics such as tumor size, location, histology, whether it is a primary or recurrent lesion, and the presence of chronic skin disease determine the recurrence rate.15 The management of advanced BCCs often requires a multidisciplinary approach, as these neoplasms may not be amenable to local therapy without causing substantial morbidity. Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice for BCCs at high risk for recurrence.16 Standard surgical excision with postoperative margin assessment is acceptable when Mohs micrographic surgery is not available.17 Radiation therapy is an alternative for patients who are not candidates for surgery.18

Recently, improved understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of BCCs has led to the development of novel systemic therapies. The Hedgehog signaling pathway has been found to play a critical role in the development of most BCCs.19 Vismodegib and sonidegib are small-molecule inhibitors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway approved for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic BCCs that are not amenable to surgery or radiation. Approximately 50% of advanced BCCs respond to these therapies; however, long-term treatment may be limited by intolerable side effects and the development of resistance.20 Basal cell carcinomas that spread to lymph nodes or distant sites are treated with traditional systemic therapy. Historically, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapies, such as platinum-containing regimens, were employed with limited benefit and notable morbidity.21

The differential diagnosis for our patient included several other cutaneous neoplasms. Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common type of skin cancer. Similar to BCC, it can reach a substantial size if left untreated. Risk factors include chronic inflammation, exposure to radiation or chemical carcinogens, burns, human papillomavirus, and other chronic infections. Giant squamous cell carcinomas have high malignant potential and require imaging to assess the extent of invasion and for metastasis. Surgery typically is necessary for both staging and treatment. Adjuvant therapy also may be necessary.22,23

Internal malignant neoplasms rarely present as cutaneous metastases. Breast cancer, melanoma, and cancers of the upper respiratory tract most frequently metastasize to the skin. Although colorectal cancer (CRC) rarely metastasizes to the skin, it is an important cause of cutaneous metastasis due to its high incidence in the general population. When it does spread to the skin, CRC preferentially affects the abdominal wall. Lesions typically resemble the primary tumor but may appear anaplastic. The occurrence of cutaneous metastasis suggests latestage disease and carries a poor prognosis.24

Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma are aggressive skin cancers with high mortality rates. The former is rarer but more lethal. Merkel cell carcinomas typically occur in elderly white men on sun-exposed areas of the skin. Tumors present as asymptomatic, rapidly expanding, blue-red, firm nodules. Immunosuppression and UV light exposure are notable risk factors.25 Of the 4 major subtypes of cutaneous melanoma, superficial spreading is the most common, followed by nodular, lentigo maligna, and acral lentiginous.26 Superficial spreading melanoma characteristically presents as an expanding asymmetric macule or thin plaque with irregular borders and variation in size and color (black, brown, or red). Nodular melanoma usually presents as symmetric in shape and color (amelanotic, black, or brown). Early recognition by both the patient and clinician is essential in preventing tumor growth and progression.27

Our patient’s presentation was highly concerning for cutaneous metastasis given her history of CRC. Furthermore, the finding of severe anemia was atypical for skin cancer and more characteristic of the prior malignancy. Imaging revealed a locally confined mass with no evidence of extension, lymph node involvement, or additional lesions. The diagnosis was clinched with histopathologic examination.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology was consistent with fungating basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The nodules were comprised of syncytial basaloid cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, numerous mitotic figures, fibromyxoid stroma, and peripheral nuclear palisading (Figure). Fortunately, no perineural or lymphovascular invasion was identified, and the margins of the specimen were negative. Despite the high-risk nature of giant BCC, the mass was solitary without notable local invasion, leaving it amendable to surgery. On follow-up, the patient has remained recurrence free, and her hemoglobin level has since stabilized.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy worldwide, and BCC accounts for more than 80% of nonmelanoma skin cancers in the United States. The incidence is on the rise due to the aging population and increasing cumulative skin exposure.1 Risk factors include both individual physical characteristics and environmental exposures. Individuals with lighter skin tones, red and blonde hair, and blue and green eyes are at an increased risk.2 UV radiation exposure is the most important cause of BCC.3 Chronic immunosuppression and exposure to arsenic, ionizing radiation, and psoralen plus UVA radiation also have been linked to the development of BCC.4-6 Basal cell carcinomas most commonly arise on sun-exposed areas such as the face, though more than 10% of cases appear on the trunk.7 Lesions characteristically remain localized, and growth rate is variable; however, when left untreated, BCCs have the potential to become locally destructive and difficult to treat.

Advanced BCCs are tumors that penetrate deeply into the skin. They often are not amenable to traditional therapy and/ or metastasize. Those that grow to a diameter greater than 5 cm, as in our patient, are known as giant BCCs. Only 0.5% to 1% of BCCs are giant BCCs8 ; they typically are more aggressive in nature with higher rates of local recurrence and metastasis. Individuals who develop giant BCCs either have had a delay in access to medical care or a history of BCC that was inadequately managed.9,10 During the COVID-19 pandemic, patient access to health care was substantially impacted during lockdowns. As in our patient, skin neoplasms and other medical conditions may present in later stages due to medical neglect.11,12 Metastasis is rare, even in advanced BCCs. A review of the literature from 1984 estimated that the incidence of metastasis of BCCs is 1 in 1000 to 35,000. Metastasis portends a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of 8 to 14 months.13 An updated review in 2013 found similar outcomes.14

The choice of management for BCCs depends on the risk for recurrence as well as individual patient factors. Characteristics such as tumor size, location, histology, whether it is a primary or recurrent lesion, and the presence of chronic skin disease determine the recurrence rate.15 The management of advanced BCCs often requires a multidisciplinary approach, as these neoplasms may not be amenable to local therapy without causing substantial morbidity. Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice for BCCs at high risk for recurrence.16 Standard surgical excision with postoperative margin assessment is acceptable when Mohs micrographic surgery is not available.17 Radiation therapy is an alternative for patients who are not candidates for surgery.18

Recently, improved understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of BCCs has led to the development of novel systemic therapies. The Hedgehog signaling pathway has been found to play a critical role in the development of most BCCs.19 Vismodegib and sonidegib are small-molecule inhibitors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway approved for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic BCCs that are not amenable to surgery or radiation. Approximately 50% of advanced BCCs respond to these therapies; however, long-term treatment may be limited by intolerable side effects and the development of resistance.20 Basal cell carcinomas that spread to lymph nodes or distant sites are treated with traditional systemic therapy. Historically, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapies, such as platinum-containing regimens, were employed with limited benefit and notable morbidity.21

The differential diagnosis for our patient included several other cutaneous neoplasms. Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common type of skin cancer. Similar to BCC, it can reach a substantial size if left untreated. Risk factors include chronic inflammation, exposure to radiation or chemical carcinogens, burns, human papillomavirus, and other chronic infections. Giant squamous cell carcinomas have high malignant potential and require imaging to assess the extent of invasion and for metastasis. Surgery typically is necessary for both staging and treatment. Adjuvant therapy also may be necessary.22,23

Internal malignant neoplasms rarely present as cutaneous metastases. Breast cancer, melanoma, and cancers of the upper respiratory tract most frequently metastasize to the skin. Although colorectal cancer (CRC) rarely metastasizes to the skin, it is an important cause of cutaneous metastasis due to its high incidence in the general population. When it does spread to the skin, CRC preferentially affects the abdominal wall. Lesions typically resemble the primary tumor but may appear anaplastic. The occurrence of cutaneous metastasis suggests latestage disease and carries a poor prognosis.24

Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma are aggressive skin cancers with high mortality rates. The former is rarer but more lethal. Merkel cell carcinomas typically occur in elderly white men on sun-exposed areas of the skin. Tumors present as asymptomatic, rapidly expanding, blue-red, firm nodules. Immunosuppression and UV light exposure are notable risk factors.25 Of the 4 major subtypes of cutaneous melanoma, superficial spreading is the most common, followed by nodular, lentigo maligna, and acral lentiginous.26 Superficial spreading melanoma characteristically presents as an expanding asymmetric macule or thin plaque with irregular borders and variation in size and color (black, brown, or red). Nodular melanoma usually presents as symmetric in shape and color (amelanotic, black, or brown). Early recognition by both the patient and clinician is essential in preventing tumor growth and progression.27

Our patient’s presentation was highly concerning for cutaneous metastasis given her history of CRC. Furthermore, the finding of severe anemia was atypical for skin cancer and more characteristic of the prior malignancy. Imaging revealed a locally confined mass with no evidence of extension, lymph node involvement, or additional lesions. The diagnosis was clinched with histopathologic examination.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Lear JT, Tan BB, Smith AG, et al. Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma in the UK: case-control study in 806 patients. J R Soc Med. 1997; 90:371-374.

- Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer: I. basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-163.

- Guo HR, Yu HS, Hu H, et al. Arsenic in drinking water and skin cancers: cell-type specificity (Taiwan, ROC). Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:909-916.

- Lichter MD, Karagas MR, Mott LA, et al; The New Hampshire Skin Cancer Study Group. Therapeutic ionizing radiation and the incidence of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1007-1011.

- Nijsten TEC, Stern RS. The increased risk of skin cancer is persistent after discontinuation of psoralen plus ultraviolet A: a cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:252-258.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Gualdi G, Monari P, Calzavara‐Pinton P, et al. When basal cell carcinomas became giant: an Italian multicenter study. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:377-382.

- Randle HW, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Giant basal cell carcinoma (T3). who is at risk? Cancer. 1993;72:1624-1630.

- Archontaki M, Stavrianos SD, Korkolis DP, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis of 51 cases and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2655-2663.

- Shifat Ahmed SAK, Ajisola M, Azeem K, et al. Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre-COVID and COVID-19 lockdown ssstakeholder engagements. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:E003042.

- Gomolin T, Cline A, Handler MZ. The danger of neglecting melanoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:444-445.

- von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma. report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043-1060.

- Wysong A, Aasi SZ, Tang JY. Update on metastatic basal cell carcinoma: a summary of published cases from 1981 through 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:615-616.

- Bøgelund FS, Philipsen PA, Gniadecki R. Factors affecting the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:330-334.

- Mosterd K, Krekels GAM, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

- Wetzig T, Woitek M, Eichhorn K, et al. Surgical excision of basal cell carcinoma with complete margin control: outcome at 5-year follow-up. Dermatology. 2010;220:363-369.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Gladstein AH, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. part 4: X-ray therapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:549-554.

- Tanese K, Emoto K, Kubota N, et al. Immunohistochemical visualization of the signature of activated Hedgehog signaling pathway in cutaneous epithelial tumors. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1181-1186.

- Basset-Séguin N, Hauschild A, Kunstfeld R, et al. Vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: primary analysis of STEVIE, an international, open-label trial. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:334-348.

- Carneiro BA, Watkin WG, Mehta UK, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: complete response to chemotherapy and associated pure red cell aplasia. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:396-400.

- Misiakos EP, Damaskou V, Koumarianou A, et al. A giant squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:136.

- Wollina U, Bayyoud Y, Krönert C, et al. Giant epithelial malignancies (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma): a series of 20 tumors from a single center. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:12-19.

- Bittencourt MJS, Imbiriba AA, Oliveira OA, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of colorectal cancer. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:884-886.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Buettner PG, Leiter U, Eigentler TK, et al. Development of prognostic factors and survival in cutaneous melanoma over 25 years: an analysis of the Central Malignant Melanoma Registry of the German Dermatological Society. Cancer. 2005;103:616-624.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 80:178-188.e3.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Lear JT, Tan BB, Smith AG, et al. Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma in the UK: case-control study in 806 patients. J R Soc Med. 1997; 90:371-374.

- Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer: I. basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-163.

- Guo HR, Yu HS, Hu H, et al. Arsenic in drinking water and skin cancers: cell-type specificity (Taiwan, ROC). Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:909-916.

- Lichter MD, Karagas MR, Mott LA, et al; The New Hampshire Skin Cancer Study Group. Therapeutic ionizing radiation and the incidence of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1007-1011.

- Nijsten TEC, Stern RS. The increased risk of skin cancer is persistent after discontinuation of psoralen plus ultraviolet A: a cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:252-258.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Gualdi G, Monari P, Calzavara‐Pinton P, et al. When basal cell carcinomas became giant: an Italian multicenter study. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:377-382.

- Randle HW, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Giant basal cell carcinoma (T3). who is at risk? Cancer. 1993;72:1624-1630.

- Archontaki M, Stavrianos SD, Korkolis DP, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis of 51 cases and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2655-2663.

- Shifat Ahmed SAK, Ajisola M, Azeem K, et al. Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre-COVID and COVID-19 lockdown ssstakeholder engagements. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:E003042.

- Gomolin T, Cline A, Handler MZ. The danger of neglecting melanoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:444-445.

- von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma. report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043-1060.

- Wysong A, Aasi SZ, Tang JY. Update on metastatic basal cell carcinoma: a summary of published cases from 1981 through 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:615-616.

- Bøgelund FS, Philipsen PA, Gniadecki R. Factors affecting the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:330-334.

- Mosterd K, Krekels GAM, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

- Wetzig T, Woitek M, Eichhorn K, et al. Surgical excision of basal cell carcinoma with complete margin control: outcome at 5-year follow-up. Dermatology. 2010;220:363-369.

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Gladstein AH, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. part 4: X-ray therapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:549-554.

- Tanese K, Emoto K, Kubota N, et al. Immunohistochemical visualization of the signature of activated Hedgehog signaling pathway in cutaneous epithelial tumors. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1181-1186.

- Basset-Séguin N, Hauschild A, Kunstfeld R, et al. Vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: primary analysis of STEVIE, an international, open-label trial. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:334-348.

- Carneiro BA, Watkin WG, Mehta UK, et al. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: complete response to chemotherapy and associated pure red cell aplasia. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:396-400.

- Misiakos EP, Damaskou V, Koumarianou A, et al. A giant squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:136.

- Wollina U, Bayyoud Y, Krönert C, et al. Giant epithelial malignancies (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma): a series of 20 tumors from a single center. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:12-19.

- Bittencourt MJS, Imbiriba AA, Oliveira OA, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of colorectal cancer. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:884-886.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Buettner PG, Leiter U, Eigentler TK, et al. Development of prognostic factors and survival in cutaneous melanoma over 25 years: an analysis of the Central Malignant Melanoma Registry of the German Dermatological Society. Cancer. 2005;103:616-624.

- Klebanov N, Gunasekera N, Lin WM, et al. The clinical spectrum of cutaneous melanoma morphology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 80:178-188.e3.

A 77-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with anemia (hemoglobin, 5.2 g/dL [reference range, 12.0–15.5 g/dL]) and a rapidly growing abdominal wall mass. She had a history of stage IIA colon cancer (T3N0M0) that was treated 5 years prior with a partial colon resection and adjuvant chemotherapy. She initially noticed a red scaly lesion developing around a scar from a prior surgery that had been stable for years. Over the last 2 months, the lesion rapidly expanded and would intermittently bleed. Physical examination revealed a 13×10×4.5-cm, pink-red, nodular, firm mass over the patient’s right upper quadrant. Computed tomography revealed a mass limited to the skin and superficial tissue. General surgery was consulted for excision of the mass.

ILAE offers first guide to treating depression in epilepsy

The new guidance highlights the high prevalence of depression among patients with epilepsy while offering the first systematic approach to treatment, reported lead author Marco Mula, MD, PhD, of Atkinson Morley Regional Neuroscience Centre at St George’s University Hospital, London, and colleagues.

“Despite evidence that depression represents a frequently encountered comorbidity [among patients with epilepsy], data on the treatment of depression in epilepsy [are] still limited and recommendations rely mostly on individual clinical experience and expertise,” the investigators wrote in Epilepsia.

Recommendations cover first-line treatment of unipolar depression in epilepsy without other psychiatric disorders.

For patients with mild depression, the guidance supports psychological intervention without pharmacologic therapy; however, if the patient wishes to use medication, has had a positive response to medication in the past, or nonpharmacologic treatments have previously failed or are unavailable, then SSRIs should be considered first-choice therapy. For moderate to severe depression, SSRIs are the first choice, according to Dr. Mula and colleagues.

“It has to be acknowledged that there is considerable debate in the psychiatric literature about the treatment of mild depression in adults,” the investigators noted. “A patient-level meta-analysis pointed out that the magnitude of benefit of antidepressant medications compared with placebo increases with severity of depression symptoms and it may be minimal or nonexistent, on average, in patients with mild or moderate symptoms.”

If a patient does not respond to first-line therapy, then venlafaxine should be considered, according to the guidance. When a patient does respond to therapy, treatment should be continued for at least 6 months, and when residual symptoms persist, treatment should be continued until resolution.

“In people with depression it is established that around two-thirds of patients do not achieve full remission with first-line treatment,” Dr. Mula and colleagues wrote. “In people with epilepsy, current data show that up to 50% of patients do not achieve full remission from depression. For this reason, augmentation strategies are often needed. They should be adopted by psychiatrists, neuropsychiatrists, or mental health professionals familiar with such therapeutic strategies.”

Beyond these key recommendations, the guidance covers a range of additional topics, including other pharmacologic options, medication discontinuation strategies, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, exercise training, vagus nerve stimulation, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Useful advice that counters common misconceptions

According to Jacqueline A. French, MD, a professor at NYU Langone Medical Center, Dr. Mula and colleagues are “top notch,” and their recommendations “hit every nail on the head.”

Dr. French, chief medical officer of The Epilepsy Foundation, emphasized the importance of the publication, which addresses two common misconceptions within the medical community: First, that standard antidepressants are insufficient to treat depression in patients with epilepsy, and second, that antidepressants may trigger seizures.

“The first purpose [of the publication] is to say, yes, these antidepressants do work,” Dr. French said, “and no, they don’t worsen seizures, and you can use them safely, and they are appropriate to use.”

Dr. French explained that managing depression remains a practice gap among epileptologists and neurologists because it is a diagnosis that doesn’t traditionally fall into their purview, yet many patients with epilepsy forgo visiting their primary care providers, who more frequently diagnose and manage depression. Dr. French agreed with the guidance that epilepsy specialists should fill this gap.

“We need to at least be able to take people through their first antidepressant, even though we were not trained to be psychiatrists,” Dr. French said. “That’s part of the best care of our patients.”

Imad Najm, MD, director of the Charles Shor Epilepsy Center, Cleveland Clinic, said the recommendations are a step forward in the field, as they are supported by clinical data, instead of just clinical experience and expertise.

Still, Dr. Najm noted that more work is needed to stratify risk of depression in epilepsy and evaluate a possible causal relationship between epilepsy therapies and depression.

He went on to emphasizes the scale of issue at hand, and the stakes involved.

“Depression, anxiety, and psychosis affect a large number of patients with epilepsy,” Dr. Najm said. “Clinical screening and recognition of these comorbidities leads to the institution of treatment options and significant improvement in quality of life. Mental health professionals should be an integral part of any comprehensive epilepsy center.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Esai, UCB, Elsevier, and others. Dr. French is indirectly involved with multiple pharmaceutical companies developing epilepsy drugs through her role as director of The Epilepsy Study Consortium, a nonprofit organization. Dr. Najm reported no conflicts of interest.

The new guidance highlights the high prevalence of depression among patients with epilepsy while offering the first systematic approach to treatment, reported lead author Marco Mula, MD, PhD, of Atkinson Morley Regional Neuroscience Centre at St George’s University Hospital, London, and colleagues.

“Despite evidence that depression represents a frequently encountered comorbidity [among patients with epilepsy], data on the treatment of depression in epilepsy [are] still limited and recommendations rely mostly on individual clinical experience and expertise,” the investigators wrote in Epilepsia.

Recommendations cover first-line treatment of unipolar depression in epilepsy without other psychiatric disorders.

For patients with mild depression, the guidance supports psychological intervention without pharmacologic therapy; however, if the patient wishes to use medication, has had a positive response to medication in the past, or nonpharmacologic treatments have previously failed or are unavailable, then SSRIs should be considered first-choice therapy. For moderate to severe depression, SSRIs are the first choice, according to Dr. Mula and colleagues.

“It has to be acknowledged that there is considerable debate in the psychiatric literature about the treatment of mild depression in adults,” the investigators noted. “A patient-level meta-analysis pointed out that the magnitude of benefit of antidepressant medications compared with placebo increases with severity of depression symptoms and it may be minimal or nonexistent, on average, in patients with mild or moderate symptoms.”

If a patient does not respond to first-line therapy, then venlafaxine should be considered, according to the guidance. When a patient does respond to therapy, treatment should be continued for at least 6 months, and when residual symptoms persist, treatment should be continued until resolution.

“In people with depression it is established that around two-thirds of patients do not achieve full remission with first-line treatment,” Dr. Mula and colleagues wrote. “In people with epilepsy, current data show that up to 50% of patients do not achieve full remission from depression. For this reason, augmentation strategies are often needed. They should be adopted by psychiatrists, neuropsychiatrists, or mental health professionals familiar with such therapeutic strategies.”

Beyond these key recommendations, the guidance covers a range of additional topics, including other pharmacologic options, medication discontinuation strategies, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, exercise training, vagus nerve stimulation, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Useful advice that counters common misconceptions

According to Jacqueline A. French, MD, a professor at NYU Langone Medical Center, Dr. Mula and colleagues are “top notch,” and their recommendations “hit every nail on the head.”

Dr. French, chief medical officer of The Epilepsy Foundation, emphasized the importance of the publication, which addresses two common misconceptions within the medical community: First, that standard antidepressants are insufficient to treat depression in patients with epilepsy, and second, that antidepressants may trigger seizures.

“The first purpose [of the publication] is to say, yes, these antidepressants do work,” Dr. French said, “and no, they don’t worsen seizures, and you can use them safely, and they are appropriate to use.”

Dr. French explained that managing depression remains a practice gap among epileptologists and neurologists because it is a diagnosis that doesn’t traditionally fall into their purview, yet many patients with epilepsy forgo visiting their primary care providers, who more frequently diagnose and manage depression. Dr. French agreed with the guidance that epilepsy specialists should fill this gap.

“We need to at least be able to take people through their first antidepressant, even though we were not trained to be psychiatrists,” Dr. French said. “That’s part of the best care of our patients.”

Imad Najm, MD, director of the Charles Shor Epilepsy Center, Cleveland Clinic, said the recommendations are a step forward in the field, as they are supported by clinical data, instead of just clinical experience and expertise.

Still, Dr. Najm noted that more work is needed to stratify risk of depression in epilepsy and evaluate a possible causal relationship between epilepsy therapies and depression.

He went on to emphasizes the scale of issue at hand, and the stakes involved.

“Depression, anxiety, and psychosis affect a large number of patients with epilepsy,” Dr. Najm said. “Clinical screening and recognition of these comorbidities leads to the institution of treatment options and significant improvement in quality of life. Mental health professionals should be an integral part of any comprehensive epilepsy center.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Esai, UCB, Elsevier, and others. Dr. French is indirectly involved with multiple pharmaceutical companies developing epilepsy drugs through her role as director of The Epilepsy Study Consortium, a nonprofit organization. Dr. Najm reported no conflicts of interest.

The new guidance highlights the high prevalence of depression among patients with epilepsy while offering the first systematic approach to treatment, reported lead author Marco Mula, MD, PhD, of Atkinson Morley Regional Neuroscience Centre at St George’s University Hospital, London, and colleagues.

“Despite evidence that depression represents a frequently encountered comorbidity [among patients with epilepsy], data on the treatment of depression in epilepsy [are] still limited and recommendations rely mostly on individual clinical experience and expertise,” the investigators wrote in Epilepsia.

Recommendations cover first-line treatment of unipolar depression in epilepsy without other psychiatric disorders.

For patients with mild depression, the guidance supports psychological intervention without pharmacologic therapy; however, if the patient wishes to use medication, has had a positive response to medication in the past, or nonpharmacologic treatments have previously failed or are unavailable, then SSRIs should be considered first-choice therapy. For moderate to severe depression, SSRIs are the first choice, according to Dr. Mula and colleagues.

“It has to be acknowledged that there is considerable debate in the psychiatric literature about the treatment of mild depression in adults,” the investigators noted. “A patient-level meta-analysis pointed out that the magnitude of benefit of antidepressant medications compared with placebo increases with severity of depression symptoms and it may be minimal or nonexistent, on average, in patients with mild or moderate symptoms.”

If a patient does not respond to first-line therapy, then venlafaxine should be considered, according to the guidance. When a patient does respond to therapy, treatment should be continued for at least 6 months, and when residual symptoms persist, treatment should be continued until resolution.

“In people with depression it is established that around two-thirds of patients do not achieve full remission with first-line treatment,” Dr. Mula and colleagues wrote. “In people with epilepsy, current data show that up to 50% of patients do not achieve full remission from depression. For this reason, augmentation strategies are often needed. They should be adopted by psychiatrists, neuropsychiatrists, or mental health professionals familiar with such therapeutic strategies.”

Beyond these key recommendations, the guidance covers a range of additional topics, including other pharmacologic options, medication discontinuation strategies, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy, exercise training, vagus nerve stimulation, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Useful advice that counters common misconceptions

According to Jacqueline A. French, MD, a professor at NYU Langone Medical Center, Dr. Mula and colleagues are “top notch,” and their recommendations “hit every nail on the head.”

Dr. French, chief medical officer of The Epilepsy Foundation, emphasized the importance of the publication, which addresses two common misconceptions within the medical community: First, that standard antidepressants are insufficient to treat depression in patients with epilepsy, and second, that antidepressants may trigger seizures.

“The first purpose [of the publication] is to say, yes, these antidepressants do work,” Dr. French said, “and no, they don’t worsen seizures, and you can use them safely, and they are appropriate to use.”

Dr. French explained that managing depression remains a practice gap among epileptologists and neurologists because it is a diagnosis that doesn’t traditionally fall into their purview, yet many patients with epilepsy forgo visiting their primary care providers, who more frequently diagnose and manage depression. Dr. French agreed with the guidance that epilepsy specialists should fill this gap.

“We need to at least be able to take people through their first antidepressant, even though we were not trained to be psychiatrists,” Dr. French said. “That’s part of the best care of our patients.”

Imad Najm, MD, director of the Charles Shor Epilepsy Center, Cleveland Clinic, said the recommendations are a step forward in the field, as they are supported by clinical data, instead of just clinical experience and expertise.

Still, Dr. Najm noted that more work is needed to stratify risk of depression in epilepsy and evaluate a possible causal relationship between epilepsy therapies and depression.

He went on to emphasizes the scale of issue at hand, and the stakes involved.

“Depression, anxiety, and psychosis affect a large number of patients with epilepsy,” Dr. Najm said. “Clinical screening and recognition of these comorbidities leads to the institution of treatment options and significant improvement in quality of life. Mental health professionals should be an integral part of any comprehensive epilepsy center.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Esai, UCB, Elsevier, and others. Dr. French is indirectly involved with multiple pharmaceutical companies developing epilepsy drugs through her role as director of The Epilepsy Study Consortium, a nonprofit organization. Dr. Najm reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM EPILEPSIA

Malnutrition common in patients with IBD

Malnutrition is common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is associated with worse outcomes that can prolong hospitalizations and increase patients’ risk for death.

As many as 85% of inpatients with IBD may be malnourished, with the severity of malnutrition affected by disease activity, extent, and duration, said Kelly Issokson, MS, RD, CNSC, clinical nutrition coordinator in the IBD program in the division of gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“Malnutrition is a severe complication of IBD, and it should not be overlooked,” she said during an oral presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

In patients with IBD, malabsorption, enteric losses, inadequate intake, and side effects of medical therapy can all lead to malnutrition, which in turn is an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolic events, nonelective surgery, longer hospital stays, and increased mortality.

In addition, malnutrition in IBD increases risk for infection and sepsis, and for perioperative complications, and can more than double the cost of care, compared with adequately nourished IBD patients, she said.

Ms. Issokson cited a definition of malnutrition from the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition as “an acute or chronic state of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammatory activity that has led to a change in body composition and diminished function.”

Lab findings of low albumin, low prealbumin, or isolated metrics such as weight loss or change in body mass index do not constitute malnutrition and should not be used to diagnosis it, Ms. Issokson cautioned.

Patients at low risk for malnutrition have no unintentional weight loss, are eating well, have minimal or no dietary restrictions, and no wasting. In contrast, high-risk patients have unintentional weight loss, decreased appetite and/or food intake, restrict multiple foods, or show signs of wasting.

Screening

“Nutrition screening is the first step in diagnosing a patient with malnutrition. This is a process of identifying individuals who may be at nutrition risk and benefit from assessment from a registered dietitian,” Ms. Issokson said.

The Malnutrition Screening Tool is quick, easy to administer, and requires minimal training. It can be used to screen adults for malnutrition regardless of age, medical history, or setting, she said.

The two-item instrument asks, “Have you recently lost weight without trying?” with a “no” scored as 0 and a “yes” scored as 2. The second question is, “Have you been eating poorly because of decreased appetite, with a “no” equal to 0 and a “yes” equal to 1. Patients with a score of 0 or 1 are not at risk, whereas patients with scores of 2 or 3 are deemed to be at risk for malnutrition and require further assessment by a dietitian.

Assessment

Assessment for malnutrition involves a variety of factors, including anthropometric factors such as weight and BMI changes; biochemical markers such as fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins, minerals, and urinary sodium; symptoms such as decreased appetite, abdominal pain, cramping or bloating, diarrhea, or urgency or obstructive symptoms; and body composition measures such as handgrip strength, biochemical impedance analysis, skinfold thickness, bone mineral density, and muscle mass.

Other nutritional assessment tools may include 24-hour recall of nutrition intake, diet history, and questions about eating behaviors, food allergies or intolerances, and cultural or religious food preferences.

Assessing food security is also important, especially during the current pandemic, Ms. Issokson emphasized.

“Is your patient running out of food? Do they have money to purchase food? Are they able to go to the grocery store to buy food? This is essential to know when you’re developing a nutrition plan,” she said.

A nutrition-focused physical exam should include assessment of skin manifestation, secondary to malnutrition or malabsorption, such as dry skin, delayed wound healing, stomatitis, scurvy, seborrheic dermatitis, bleeding, and periorificial and acral dermatitis or alopecia.

Diagnosis

Currently available malnutrition criteria have not been validated for use in patients with IBD, and further studies are needed to affirm their applicability to this population, Ms. Issokson said.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics–American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (AND-ASPEN) malnutrition criteria require measures of weight loss, energy intake, subcutaneous fat loss, subcutaneous muscle loss, general or local fluid accumulation, and handgrip strength to determine whether a patient is moderately or severely malnourished.

Ms. Issokson said that she finds the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (ESPEN GLIM) criteria somewhat easier to use for diagnosis, as they consist of phenotypic and etiologic criteria, with patients who meet at least one of each being considered malnourished.

“When identified, document malnutrition, and of course intervene appropriately by referring to a dietitian providing education and supporting the patient to help them optimize their nutrition and improve their outcomes,” she concluded.

In a discussion following the session, panelist Neha Shah, MPH, RD, CNSC, a dietitian and health education specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, commented on the importance of malnutrition assessment in patients with IBD being considered for surgery.

Patients should be screened for malnutrition, and if they have a positive screen, “should be automatically referred to a registered dietitian specializing in IBD for a nutrition assessment,” she said.

“Certainly, a nutritional assessment, as Kelly has highlighted really well, will encompass an evaluation of various areas of health – patient history, food and nutrition history, changing anthropometrics, alterations in labs – and certainly going into further nutrition history with net food intolerance, intake from each food group, portions, access, support, culture, eating environment, skills in the kitchen, relationship with diet.”

Ms. Issokson is a board member of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and a digital advisory board member of Avant Healthcare. Ms. Shah had no disclosures.

Malnutrition is common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is associated with worse outcomes that can prolong hospitalizations and increase patients’ risk for death.

As many as 85% of inpatients with IBD may be malnourished, with the severity of malnutrition affected by disease activity, extent, and duration, said Kelly Issokson, MS, RD, CNSC, clinical nutrition coordinator in the IBD program in the division of gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“Malnutrition is a severe complication of IBD, and it should not be overlooked,” she said during an oral presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

In patients with IBD, malabsorption, enteric losses, inadequate intake, and side effects of medical therapy can all lead to malnutrition, which in turn is an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolic events, nonelective surgery, longer hospital stays, and increased mortality.

In addition, malnutrition in IBD increases risk for infection and sepsis, and for perioperative complications, and can more than double the cost of care, compared with adequately nourished IBD patients, she said.

Ms. Issokson cited a definition of malnutrition from the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition as “an acute or chronic state of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammatory activity that has led to a change in body composition and diminished function.”

Lab findings of low albumin, low prealbumin, or isolated metrics such as weight loss or change in body mass index do not constitute malnutrition and should not be used to diagnosis it, Ms. Issokson cautioned.

Patients at low risk for malnutrition have no unintentional weight loss, are eating well, have minimal or no dietary restrictions, and no wasting. In contrast, high-risk patients have unintentional weight loss, decreased appetite and/or food intake, restrict multiple foods, or show signs of wasting.

Screening

“Nutrition screening is the first step in diagnosing a patient with malnutrition. This is a process of identifying individuals who may be at nutrition risk and benefit from assessment from a registered dietitian,” Ms. Issokson said.

The Malnutrition Screening Tool is quick, easy to administer, and requires minimal training. It can be used to screen adults for malnutrition regardless of age, medical history, or setting, she said.

The two-item instrument asks, “Have you recently lost weight without trying?” with a “no” scored as 0 and a “yes” scored as 2. The second question is, “Have you been eating poorly because of decreased appetite, with a “no” equal to 0 and a “yes” equal to 1. Patients with a score of 0 or 1 are not at risk, whereas patients with scores of 2 or 3 are deemed to be at risk for malnutrition and require further assessment by a dietitian.

Assessment

Assessment for malnutrition involves a variety of factors, including anthropometric factors such as weight and BMI changes; biochemical markers such as fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins, minerals, and urinary sodium; symptoms such as decreased appetite, abdominal pain, cramping or bloating, diarrhea, or urgency or obstructive symptoms; and body composition measures such as handgrip strength, biochemical impedance analysis, skinfold thickness, bone mineral density, and muscle mass.

Other nutritional assessment tools may include 24-hour recall of nutrition intake, diet history, and questions about eating behaviors, food allergies or intolerances, and cultural or religious food preferences.

Assessing food security is also important, especially during the current pandemic, Ms. Issokson emphasized.

“Is your patient running out of food? Do they have money to purchase food? Are they able to go to the grocery store to buy food? This is essential to know when you’re developing a nutrition plan,” she said.

A nutrition-focused physical exam should include assessment of skin manifestation, secondary to malnutrition or malabsorption, such as dry skin, delayed wound healing, stomatitis, scurvy, seborrheic dermatitis, bleeding, and periorificial and acral dermatitis or alopecia.

Diagnosis

Currently available malnutrition criteria have not been validated for use in patients with IBD, and further studies are needed to affirm their applicability to this population, Ms. Issokson said.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics–American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (AND-ASPEN) malnutrition criteria require measures of weight loss, energy intake, subcutaneous fat loss, subcutaneous muscle loss, general or local fluid accumulation, and handgrip strength to determine whether a patient is moderately or severely malnourished.

Ms. Issokson said that she finds the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (ESPEN GLIM) criteria somewhat easier to use for diagnosis, as they consist of phenotypic and etiologic criteria, with patients who meet at least one of each being considered malnourished.

“When identified, document malnutrition, and of course intervene appropriately by referring to a dietitian providing education and supporting the patient to help them optimize their nutrition and improve their outcomes,” she concluded.

In a discussion following the session, panelist Neha Shah, MPH, RD, CNSC, a dietitian and health education specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, commented on the importance of malnutrition assessment in patients with IBD being considered for surgery.

Patients should be screened for malnutrition, and if they have a positive screen, “should be automatically referred to a registered dietitian specializing in IBD for a nutrition assessment,” she said.

“Certainly, a nutritional assessment, as Kelly has highlighted really well, will encompass an evaluation of various areas of health – patient history, food and nutrition history, changing anthropometrics, alterations in labs – and certainly going into further nutrition history with net food intolerance, intake from each food group, portions, access, support, culture, eating environment, skills in the kitchen, relationship with diet.”

Ms. Issokson is a board member of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and a digital advisory board member of Avant Healthcare. Ms. Shah had no disclosures.

Malnutrition is common among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is associated with worse outcomes that can prolong hospitalizations and increase patients’ risk for death.

As many as 85% of inpatients with IBD may be malnourished, with the severity of malnutrition affected by disease activity, extent, and duration, said Kelly Issokson, MS, RD, CNSC, clinical nutrition coordinator in the IBD program in the division of gastroenterology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“Malnutrition is a severe complication of IBD, and it should not be overlooked,” she said during an oral presentation at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

In patients with IBD, malabsorption, enteric losses, inadequate intake, and side effects of medical therapy can all lead to malnutrition, which in turn is an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolic events, nonelective surgery, longer hospital stays, and increased mortality.

In addition, malnutrition in IBD increases risk for infection and sepsis, and for perioperative complications, and can more than double the cost of care, compared with adequately nourished IBD patients, she said.

Ms. Issokson cited a definition of malnutrition from the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition as “an acute or chronic state of overnutrition or undernutrition with or without inflammatory activity that has led to a change in body composition and diminished function.”

Lab findings of low albumin, low prealbumin, or isolated metrics such as weight loss or change in body mass index do not constitute malnutrition and should not be used to diagnosis it, Ms. Issokson cautioned.

Patients at low risk for malnutrition have no unintentional weight loss, are eating well, have minimal or no dietary restrictions, and no wasting. In contrast, high-risk patients have unintentional weight loss, decreased appetite and/or food intake, restrict multiple foods, or show signs of wasting.

Screening

“Nutrition screening is the first step in diagnosing a patient with malnutrition. This is a process of identifying individuals who may be at nutrition risk and benefit from assessment from a registered dietitian,” Ms. Issokson said.

The Malnutrition Screening Tool is quick, easy to administer, and requires minimal training. It can be used to screen adults for malnutrition regardless of age, medical history, or setting, she said.

The two-item instrument asks, “Have you recently lost weight without trying?” with a “no” scored as 0 and a “yes” scored as 2. The second question is, “Have you been eating poorly because of decreased appetite, with a “no” equal to 0 and a “yes” equal to 1. Patients with a score of 0 or 1 are not at risk, whereas patients with scores of 2 or 3 are deemed to be at risk for malnutrition and require further assessment by a dietitian.

Assessment

Assessment for malnutrition involves a variety of factors, including anthropometric factors such as weight and BMI changes; biochemical markers such as fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins, minerals, and urinary sodium; symptoms such as decreased appetite, abdominal pain, cramping or bloating, diarrhea, or urgency or obstructive symptoms; and body composition measures such as handgrip strength, biochemical impedance analysis, skinfold thickness, bone mineral density, and muscle mass.

Other nutritional assessment tools may include 24-hour recall of nutrition intake, diet history, and questions about eating behaviors, food allergies or intolerances, and cultural or religious food preferences.

Assessing food security is also important, especially during the current pandemic, Ms. Issokson emphasized.

“Is your patient running out of food? Do they have money to purchase food? Are they able to go to the grocery store to buy food? This is essential to know when you’re developing a nutrition plan,” she said.

A nutrition-focused physical exam should include assessment of skin manifestation, secondary to malnutrition or malabsorption, such as dry skin, delayed wound healing, stomatitis, scurvy, seborrheic dermatitis, bleeding, and periorificial and acral dermatitis or alopecia.

Diagnosis

Currently available malnutrition criteria have not been validated for use in patients with IBD, and further studies are needed to affirm their applicability to this population, Ms. Issokson said.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics–American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (AND-ASPEN) malnutrition criteria require measures of weight loss, energy intake, subcutaneous fat loss, subcutaneous muscle loss, general or local fluid accumulation, and handgrip strength to determine whether a patient is moderately or severely malnourished.

Ms. Issokson said that she finds the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (ESPEN GLIM) criteria somewhat easier to use for diagnosis, as they consist of phenotypic and etiologic criteria, with patients who meet at least one of each being considered malnourished.

“When identified, document malnutrition, and of course intervene appropriately by referring to a dietitian providing education and supporting the patient to help them optimize their nutrition and improve their outcomes,” she concluded.

In a discussion following the session, panelist Neha Shah, MPH, RD, CNSC, a dietitian and health education specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, commented on the importance of malnutrition assessment in patients with IBD being considered for surgery.

Patients should be screened for malnutrition, and if they have a positive screen, “should be automatically referred to a registered dietitian specializing in IBD for a nutrition assessment,” she said.

“Certainly, a nutritional assessment, as Kelly has highlighted really well, will encompass an evaluation of various areas of health – patient history, food and nutrition history, changing anthropometrics, alterations in labs – and certainly going into further nutrition history with net food intolerance, intake from each food group, portions, access, support, culture, eating environment, skills in the kitchen, relationship with diet.”

Ms. Issokson is a board member of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and a digital advisory board member of Avant Healthcare. Ms. Shah had no disclosures.

FROM THE CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

CDC, AAP issues new guidelines to better define developmental milestones

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics recently issued revised milestone guidelines for their developmental surveillance campaign, Learn the Signs, Act Early (LTSAE).

The new guidelines, published in Pediatrics, were drafted in “easy-to-understand” language and identify the behaviors that 75% or more of children should exhibit at certain ages based on developmental resources, existing data, and clinician experience. The previous milestone checklists, developed in 2004, used 50th percentile or average-age milestones.

The CDC, in collaboration with the AAP, convened a group of eight subject matter experts in various fields of child development, including a developmental pediatrician and researcher from Kennedy Krieger Institute, to develop new and clearer guidelines.

“The goals of the group were to identify evidence-informed milestones to include in CDC checklists, clarify when most children can be expected to reach a milestone (to discourage a wait-and-see approach), and support clinical judgment regarding screening between recommended ages,” wrote lead author Jennifer M. Zubler, MD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities in Atlanta, and colleagues.

Key changes

The experts established 11 criteria for CDC surveillance milestones and tools, including milestones most children (75% or more) would be expected to reach by defined health supervision visit ages and those that are easily recognized in natural settings.

Criteria for developmental milestones and surveillance tools:

- Milestones are included at the age most (≥75%) children would be expected to demonstrate the milestone.

- Eliminate “warning signs.”

- Are easy for families of different social, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds to observe and use.

- Are able to be answered with yes, not yet, or not sure.

- Use plain language, avoiding vague terms like may, can, and begins.

- Are organized in developmental domains.

- Show progression of skills with age, when possible.

- Milestones are not repeated across checklists.

- Include open-ended questions.

- Include information for developmental promotion.

- Include information on how to act early if there are concerns.

The previous guidelines were critiqued by some clinicians as being “not helpful to individual families who had concerns about their child’s development,” and in some cases, led to delays in diagnoses as decision-makers opted for a “wait-and-see approach.”

“The earlier a child is identified with a developmental delay the better, as treatment as well as learning interventions can begin,” Paul Lipkin, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an accompanying press release. “Revising the guidelines with expertise and data from clinicians in the field accomplishes these goals.”

Additional changes included new checklists for children between the ages of 15 and 30 months, additional social and emotional milestones, as well as the removal of complex language and duplicate milestones. The experts also developed new, open-ended questions to aid discussions with families.

“Review of a child’s development with these milestones opens up a continuous dialogue between a parent and the health care provider about their child’s present and future development,” said Dr. Lipkin.

Originally pioneered in 2005, the LTSAE awareness campaign provides free resources to clinicians and families to support early detection of children with developmental delays and disabilities. After the new guidelines were drafted, they were presented to parents of various racial groups, income levels, and educational backgrounds to confirm ease of use and understandability.

“These criteria and revised checklists can be used to support developmental surveillance, clinical judgment regarding additional developmental screening, and research in developmental surveillance processes,” wrote Dr. Zubler.

Expert perspective

“These new guidelines will allow us to catch more children with developmental delays as they raise the threshold to 75% of children achieving those milestones at that particular age,” Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician in Cheshire, Conn., said in an interview.

Dr. Kinsella added that the new guidelines simplify the milestones and reduce redundancy across different developmental domains. “Most importantly, it gave me the opportunity to see just how great the CDC milestone tracker app is – I think parents would really like it.”

This project was supported by the CDC and Prevention of the Department of Health & Human Services. One author is a developer of the Ages & Stages Questionnaires and receives royalties from Brookes Publishing, the company that publishes this tool; the other authors have indicated they have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics recently issued revised milestone guidelines for their developmental surveillance campaign, Learn the Signs, Act Early (LTSAE).

The new guidelines, published in Pediatrics, were drafted in “easy-to-understand” language and identify the behaviors that 75% or more of children should exhibit at certain ages based on developmental resources, existing data, and clinician experience. The previous milestone checklists, developed in 2004, used 50th percentile or average-age milestones.

The CDC, in collaboration with the AAP, convened a group of eight subject matter experts in various fields of child development, including a developmental pediatrician and researcher from Kennedy Krieger Institute, to develop new and clearer guidelines.

“The goals of the group were to identify evidence-informed milestones to include in CDC checklists, clarify when most children can be expected to reach a milestone (to discourage a wait-and-see approach), and support clinical judgment regarding screening between recommended ages,” wrote lead author Jennifer M. Zubler, MD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities in Atlanta, and colleagues.

Key changes

The experts established 11 criteria for CDC surveillance milestones and tools, including milestones most children (75% or more) would be expected to reach by defined health supervision visit ages and those that are easily recognized in natural settings.

Criteria for developmental milestones and surveillance tools:

- Milestones are included at the age most (≥75%) children would be expected to demonstrate the milestone.

- Eliminate “warning signs.”

- Are easy for families of different social, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds to observe and use.

- Are able to be answered with yes, not yet, or not sure.

- Use plain language, avoiding vague terms like may, can, and begins.

- Are organized in developmental domains.

- Show progression of skills with age, when possible.

- Milestones are not repeated across checklists.

- Include open-ended questions.

- Include information for developmental promotion.

- Include information on how to act early if there are concerns.

The previous guidelines were critiqued by some clinicians as being “not helpful to individual families who had concerns about their child’s development,” and in some cases, led to delays in diagnoses as decision-makers opted for a “wait-and-see approach.”