User login

High-intensity exercise vs. omega-3s for heart failure risk reduction

A year of high-intensity interval training seemed to benefit obese middle-aged adults at a high risk of heart failure, but omega-3 fatty acid supplementation didn’t have any effect on cardiac biomarkers measured in a small, single-center, prospective study.

“One year of HIIT training reduces adiposity but had no consistent effect on myocardial triglyceride content or visceral adiposity,” wrote lead author Christopher M. Hearon Jr., PhD, and colleagues in JACC: Heart Failure. “However, long-duration HIIT improves fitness and induces favorable cardiac remodeling.” Omega-3 supplementation, however, had “no independent or additive effect.” Dr. Hearon is an instructor of applied clinical research at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Investigators there and at the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas studied 80 patients aged 40-55 years classified as high risk for HF and obese, randomizing them to a year of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) with supplementation of either 1.6 g omega-3 FA or placebo daily; or to a control group split between supplementation or placebo. Fifty-six patients completed the 1-year study, with a compliance rate of 90% in the HIIT group and 92% in those assigned omega-3 FA supplementation.

Carl J. “Chip” Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans, commented that, although the study was “extremely well done from an excellent research group,” it was limited by its small population and relatively short follow-up. Future research should evaluate HIIT and moderate exercise on clinical events over a longer term as well as different doses of omega-3 “There is tremendous potential for omega-3 in heart failure prevention and treatment.”

HIIT boosts exercise capacity, more

In the study, the HIIT group showed improvement in a number of cardiac markers: around a 22% improvement in exercise capacity as measured by absolute peak and relative peak oxygen uptake (VO2), even without significant weight loss. They improved an average of 0.43 L/min (0.32-0.53; P < .0001) and 4.46 mL/kg per minute (3.18-5.56; P < .0001), respectively.

The researchers attributed the increase in peak VO2 to an increase in peak cardiac output averaging 2.15 L/min (95% confidence interval, 0.90-3.39; P = .001) and stroke volume averaging 9.46 mL (95% CI, 0.65-18.27; P = .04). A year of exercise training also resulted in changes in cardiac remodeling, including increases in left ventricle mass and LV end diastolic volume, averaging 9.4 g (95% CI, 4.36-14.44; P < .001) and 12.33 mL (95% CI, 5.61-19.05; P < .001), respectively.

The study also found that neither intervention had any appreciable impact on body weight, body mass index, body surface area or lean mass, or markers of arterial or local carotid stiffness. The exercise group had a modest decrease in fat mass, averaging 2.63 kg (95% CI,–4.81 to –0.46; P = .02), but without any effect from omega-3 supplementation.

The study acknowledged that high-dose omega-3 supplements have been found to lower triglyceride levels in people with severe hypertriglyceridemia, and hypothesized that HIIT alone or with omega-3 supplementation would improve fitness and biomarkers in people with stage A HF. “Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that one year of n-3FA [omega-3 FA] supplementation had no detectable effect on any parameter related to cardiopulmonary fitness, cardiovascular remodeling/stiffness, visceral adiposity, or myocardial triglyceride content,” Dr. Hearon and colleagues wrote.

The study “shows that obese middle-aged patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF] can markedly improve their fitness with HIIT and, generally, fitness is one of the strongest if not the strongest predictor of prognosis and survival,” said Dr. Lavie.

“Studies are needed on exercise that improves fitness in both HF with reduced ejection fraction and HFpEF, but especially HFpEF,” he said.

The study received funding from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network. Dr. Hearon and coauthors have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Lavie is a speaker and consultant for PAI Health, the Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3s and DSM Nutritional Products.

A year of high-intensity interval training seemed to benefit obese middle-aged adults at a high risk of heart failure, but omega-3 fatty acid supplementation didn’t have any effect on cardiac biomarkers measured in a small, single-center, prospective study.

“One year of HIIT training reduces adiposity but had no consistent effect on myocardial triglyceride content or visceral adiposity,” wrote lead author Christopher M. Hearon Jr., PhD, and colleagues in JACC: Heart Failure. “However, long-duration HIIT improves fitness and induces favorable cardiac remodeling.” Omega-3 supplementation, however, had “no independent or additive effect.” Dr. Hearon is an instructor of applied clinical research at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Investigators there and at the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas studied 80 patients aged 40-55 years classified as high risk for HF and obese, randomizing them to a year of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) with supplementation of either 1.6 g omega-3 FA or placebo daily; or to a control group split between supplementation or placebo. Fifty-six patients completed the 1-year study, with a compliance rate of 90% in the HIIT group and 92% in those assigned omega-3 FA supplementation.

Carl J. “Chip” Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans, commented that, although the study was “extremely well done from an excellent research group,” it was limited by its small population and relatively short follow-up. Future research should evaluate HIIT and moderate exercise on clinical events over a longer term as well as different doses of omega-3 “There is tremendous potential for omega-3 in heart failure prevention and treatment.”

HIIT boosts exercise capacity, more

In the study, the HIIT group showed improvement in a number of cardiac markers: around a 22% improvement in exercise capacity as measured by absolute peak and relative peak oxygen uptake (VO2), even without significant weight loss. They improved an average of 0.43 L/min (0.32-0.53; P < .0001) and 4.46 mL/kg per minute (3.18-5.56; P < .0001), respectively.

The researchers attributed the increase in peak VO2 to an increase in peak cardiac output averaging 2.15 L/min (95% confidence interval, 0.90-3.39; P = .001) and stroke volume averaging 9.46 mL (95% CI, 0.65-18.27; P = .04). A year of exercise training also resulted in changes in cardiac remodeling, including increases in left ventricle mass and LV end diastolic volume, averaging 9.4 g (95% CI, 4.36-14.44; P < .001) and 12.33 mL (95% CI, 5.61-19.05; P < .001), respectively.

The study also found that neither intervention had any appreciable impact on body weight, body mass index, body surface area or lean mass, or markers of arterial or local carotid stiffness. The exercise group had a modest decrease in fat mass, averaging 2.63 kg (95% CI,–4.81 to –0.46; P = .02), but without any effect from omega-3 supplementation.

The study acknowledged that high-dose omega-3 supplements have been found to lower triglyceride levels in people with severe hypertriglyceridemia, and hypothesized that HIIT alone or with omega-3 supplementation would improve fitness and biomarkers in people with stage A HF. “Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that one year of n-3FA [omega-3 FA] supplementation had no detectable effect on any parameter related to cardiopulmonary fitness, cardiovascular remodeling/stiffness, visceral adiposity, or myocardial triglyceride content,” Dr. Hearon and colleagues wrote.

The study “shows that obese middle-aged patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF] can markedly improve their fitness with HIIT and, generally, fitness is one of the strongest if not the strongest predictor of prognosis and survival,” said Dr. Lavie.

“Studies are needed on exercise that improves fitness in both HF with reduced ejection fraction and HFpEF, but especially HFpEF,” he said.

The study received funding from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network. Dr. Hearon and coauthors have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Lavie is a speaker and consultant for PAI Health, the Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3s and DSM Nutritional Products.

A year of high-intensity interval training seemed to benefit obese middle-aged adults at a high risk of heart failure, but omega-3 fatty acid supplementation didn’t have any effect on cardiac biomarkers measured in a small, single-center, prospective study.

“One year of HIIT training reduces adiposity but had no consistent effect on myocardial triglyceride content or visceral adiposity,” wrote lead author Christopher M. Hearon Jr., PhD, and colleagues in JACC: Heart Failure. “However, long-duration HIIT improves fitness and induces favorable cardiac remodeling.” Omega-3 supplementation, however, had “no independent or additive effect.” Dr. Hearon is an instructor of applied clinical research at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Investigators there and at the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas studied 80 patients aged 40-55 years classified as high risk for HF and obese, randomizing them to a year of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) with supplementation of either 1.6 g omega-3 FA or placebo daily; or to a control group split between supplementation or placebo. Fifty-six patients completed the 1-year study, with a compliance rate of 90% in the HIIT group and 92% in those assigned omega-3 FA supplementation.

Carl J. “Chip” Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans, commented that, although the study was “extremely well done from an excellent research group,” it was limited by its small population and relatively short follow-up. Future research should evaluate HIIT and moderate exercise on clinical events over a longer term as well as different doses of omega-3 “There is tremendous potential for omega-3 in heart failure prevention and treatment.”

HIIT boosts exercise capacity, more

In the study, the HIIT group showed improvement in a number of cardiac markers: around a 22% improvement in exercise capacity as measured by absolute peak and relative peak oxygen uptake (VO2), even without significant weight loss. They improved an average of 0.43 L/min (0.32-0.53; P < .0001) and 4.46 mL/kg per minute (3.18-5.56; P < .0001), respectively.

The researchers attributed the increase in peak VO2 to an increase in peak cardiac output averaging 2.15 L/min (95% confidence interval, 0.90-3.39; P = .001) and stroke volume averaging 9.46 mL (95% CI, 0.65-18.27; P = .04). A year of exercise training also resulted in changes in cardiac remodeling, including increases in left ventricle mass and LV end diastolic volume, averaging 9.4 g (95% CI, 4.36-14.44; P < .001) and 12.33 mL (95% CI, 5.61-19.05; P < .001), respectively.

The study also found that neither intervention had any appreciable impact on body weight, body mass index, body surface area or lean mass, or markers of arterial or local carotid stiffness. The exercise group had a modest decrease in fat mass, averaging 2.63 kg (95% CI,–4.81 to –0.46; P = .02), but without any effect from omega-3 supplementation.

The study acknowledged that high-dose omega-3 supplements have been found to lower triglyceride levels in people with severe hypertriglyceridemia, and hypothesized that HIIT alone or with omega-3 supplementation would improve fitness and biomarkers in people with stage A HF. “Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that one year of n-3FA [omega-3 FA] supplementation had no detectable effect on any parameter related to cardiopulmonary fitness, cardiovascular remodeling/stiffness, visceral adiposity, or myocardial triglyceride content,” Dr. Hearon and colleagues wrote.

The study “shows that obese middle-aged patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF] can markedly improve their fitness with HIIT and, generally, fitness is one of the strongest if not the strongest predictor of prognosis and survival,” said Dr. Lavie.

“Studies are needed on exercise that improves fitness in both HF with reduced ejection fraction and HFpEF, but especially HFpEF,” he said.

The study received funding from the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network. Dr. Hearon and coauthors have no relevant disclosures. Dr. Lavie is a speaker and consultant for PAI Health, the Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3s and DSM Nutritional Products.

FROM JACC: HEART FAILURE

Hematocrit, White Blood Cells, and Thrombotic Events in the Veteran Population With Polycythemia Vera

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm affecting 44 to 57 individuals per 100,000 in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in hyperproliferation of mature myeloid lineage cells.2 Sustained erythrocytosis is a hallmark of PV, although many patients also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.2,3 These patients have increased inherent thrombotic risk with arterial events reported to occur at rates of 7 to 21/1000 person-years and venous thrombotic events at 5 to 20/1000 person-years.4-7 Thrombotic and cardiovascular events are leading causes of morbidity and mortality, resulting in a reduced overall survival of patients with PV compared with the general population.3,8-10

Blood Cell Counts and Thrombotic Events in PV

Treatment strategies for patients with PV mainly aim to prevent or manage thrombotic and bleeding complications through normalization of blood counts.11 Hematocrit (Hct) control has been reported to be associated with reduced thrombotic risk in patients with PV. This was shown and popularized by the prospective, randomized Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial in which participants were randomized 1:1 to maintaining either a low (< 45%) or high (45%-50%) Hct for 5 years to examine the long-term effects of more- or less-intensive cytoreductive therapy.12 Patients in the low-Hct group were found to have a lower rate of death from cardiovascular events or major thrombosis (1.1/100 person-years in the low-Hct group vs 4.4 in the high-Hct group; hazard ratio [HR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-10.53; P = .007). Likewise, cardiovascular events occurred at a lower rate in patients in the low-Hct group compared with the high-Hct group (4.4% vs 10.9% of patients, respectively; HR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.19-6.12; P = .02).12

Leukocytosis has also been linked to elevated risk for vascular events as shown in several studies, including the real-world European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) observational study and a post hoc subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study.13,14 In a multivariate, time-dependent analysis in ECLAP, patients with white blood cell (WBC) counts > 15 × 109/L had a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis compared with those who had lower WBC counts, with higher WBC count more strongly associated with arterial than venous thromboembolism.13 In CYTO-PV, a significant correlation between elevated WBC count (≥ 11 × 109/L vs reference level of < 7 × 109/L) and time-dependent risk of major thrombosis was shown (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.24-12.3; P = .02).14 Likewise, WBC count ≥ 11 × 109/L was found to be a predictor of subsequent venous events in a separate single-center multivariate analysis of patients with PV.8

Although CYTO-PV remains one of the largest prospective landmark studies in PV demonstrating the impact of Hct control on thrombosis, it is worthwhile to note that the patients in the high-Hct group who received less frequent myelosuppressive therapy with hydroxyurea than the low-Hct group also had higher WBC counts.12,15 Work is needed to determine the relative effects of high Hct and high WBC counts on PV independent of each other.

The Veteran Population with PV

Two recently published retrospective analyses from Parasuraman and colleagues used data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, with an aim to replicate findings from CYTO-PV in a real-world population.16,17 The 2 analyses focused independently on the effects of Hct control and WBC count on the risk of a thrombotic event in patients with PV.

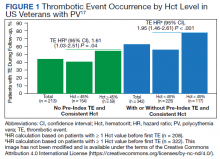

In the first retrospective analysis, 213 patients with PV and no prior thrombosis were placed into groups based on whether Hct levels were consistently either < 45% or ≥ 45% throughout the study period.17 The mean follow-up time was 2.3 years, during which 44.1% of patients experienced a thrombotic event (Figure 1). Patients with Hct levels < 45% had a lower rate of thrombotic events compared to those with levels ≥ 45% (40.3% vs 54.2%, respectively; HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51; P = .04). In a sensitivity analysis that included patients with pre-index thrombotic events (N = 342), similar results were noted (55.6% vs 76.9% between the < 45% and ≥ 45% groups, respectively; HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46-2.61; P < .001).

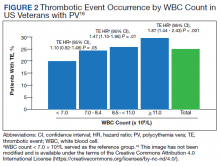

In the second analysis, the authors investigated the relationship between WBC counts and thrombotic events.16 Evaluable patients (N = 1565) were grouped into 1 of 4 cohorts based on the last WBC measurement taken during the study period before a thrombotic event or through the end of follow-up: (1) WBC < 7.0 × 109/L, (2) 7.0 to 8.4 × 109/L, (3) 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L, or (4) ≥ 11.0 × 109/L. Mean follow-up time ranged from 3.6 to 4.5 years among WBC count cohorts, during which 24.9% of patients experienced a thrombotic event. Compared with the reference cohort (WBC < 7.0 × 109/L), a significant positive association between WBC counts and thrombotic event occurrence was observed among patients with WBC counts of 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96; P < .01) and ≥ 11 × 109/L (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.44-2.43; P < .001) (Figure 2).16 When including all patients in a sensitivity analysis regardless of whether they experienced thrombotic events before the index date (N = 1876), similar results were obtained (7.0-8.4 × 109/L group: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.97-1.55; P = .0959; 8.5 - 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81; P = .0062; ≥ 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001; compared with < 7.0 × 109/L reference group). Rates of phlebotomy and cytoreductive treatments were similar across groups.16

Some limitations to these studies are attributable to their retrospective design, reliance on health records, and the VHA population characteristics, which differ from the general population. For example, in this analysis, patients with PV in the VHA population had significantly increased risk of thrombotic events, even at a lower WBC count threshold (≥ 8.5 × 109/L) compared with those reported in CYTO-PV (≥ 11 × 109/L). Furthermore, approximately one-third of patients had elevated WBC levels, compared with 25.5% in the CYTO-PV study.14,16 This is most likely due to the unique nature of the VHA patient population, who are predominantly older adult men and generally have a higher comorbidity burden. A notable pre-index comorbidity burden was reported in the VHA population in the Hct analysis, even when compared to patients with PV in the general US population (Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 1.3 vs 0.8).6,17 Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use, which are most common among the VHA population, are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events.18,19 However, whether these higher levels of comorbidities affected the type of treatments they received was not elucidated, and the effectiveness of treatments to maintain target Hct levels was not addressed in the study.

Current PV Management and Future Implications

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology in myeloproliferative neoplasms recommend maintaining Hct levels < 45% in patients with PV.11 Patients with high-risk disease (age ≥ 60 years and/or history of thrombosis) are monitored for new thrombosis or bleeding and are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, they receive low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, and are managed with pharmacologic cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy primarily consists of hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a for younger patients. Ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor, is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as second-line treatment for those with PV that is intolerant or unresponsive to hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a treatments.11,20 However, the role of cytoreductive therapy is not clear for patients with low-risk disease (age < 60 years and no history of thrombosis). These patients are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors, undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, are maintained on low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), and are monitored for indications for cytoreductive therapy, which include any new thrombosis or disease-related major bleeding, frequent or persistent need for phlebotomy with poor tolerance for the procedure, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and disease-related symptoms (eg, aquagenic pruritus, night sweats, fatigue).

Even though the current guidelines recommend maintaining a target Hct of < 45% in patients with high-risk PV, the role of Hct as the main determinant of thrombotic risk in patients with PV is still debated.21 In JAK2V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia, Hct levels are usually normal but risk of thrombosis is nevertheless still significant.22 The risk of thrombosis is significantly lower in primary familial and congenital polycythemia and much lower in secondary erythrocytosis such as cyanotic heart disease, long-term native dwellers of high altitude, and those with high-oxygen–affinity hemoglobins.21,23 In secondary erythrocytosis from hypoxia or upregulated hypoxic pathway such as hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) mutation and Chuvash erythrocytosis, the risk of thrombosis is more associated with the upregulated HIF pathway and its downstream consequences, rather than the elevated Hct level.24

However, most current literature supports the association of increased risk of thrombosis with higher Hct and high WBC count in patients with PV. In addition, the underlying mechanism of thrombogenesis still remains elusive; it is likely a complex process that involves interactions among multiple components, including elevated blood counts arising from clonal hematopoiesis, JAK2V617F allele burden, and platelet and WBC activation and their interaction with endothelial cells and inflammatory cytokines.25

Nevertheless, Hct control and aspirin use are current standard of care for patients with PV to mitigate thrombotic risk, and the results from the 2 analyses by Parasuraman and colleagues, using real-world data from the VHA, support the current practice guidelines to maintain Hct < 45% in these patients. They also provide additional support for considering WBC counts when determining patient risk and treatment plans. Although treatment response criteria from the European LeukemiaNet include achieving normal WBC levels to decrease the risk of thrombosis, current NCCN guidelines do not include WBC counts as a component for establishing patient risk or provide a target WBC count to guide patient management.11,26,27 Updates to these practice guidelines may be warranted. In addition, further study is needed to understand the mechanism of thrombogenesis in PV and other myeloproliferative disorders in order to develop novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Tania Iqbal, PhD, an employee of ICON (North Wales, PA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE).

1. Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595-600. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.813500

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

3. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1874-1881. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.163

4. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R, et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2224-2232. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062

5. Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110(3):840-846. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287

6. Goyal RK, Davis KL, Cote I, Mounedji N, Kaye JA. Increased incidence of thromboembolic event rates in patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera: results from an observational cohort study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2014;124:4840. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.4840.4840

7. Barbui T, Carobbio A, Rumi E, et al. In contemporary patients with polycythemia vera, rates of thrombosis and risk factors delineate a new clinical epidemiology. Blood. 2014;124(19):3021-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-591610 8. Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, et al. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(12):662. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6

9. Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV. Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, and emerging treatment options. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):1965-1976. doi:10.1007/s00277-014-2205-y

10. Hultcrantz M, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM-L, et al. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2995-3001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1925

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in myeloproliferative neoplasms (Version 1.2020). Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

12. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

13. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Barbui T, et al. Leukocytosis as a major thrombotic risk factor in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2007;109(6):2446-2452. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-042515

14. Barbui T, Masciulli A, Marfisi MR, et al. White blood cell counts and thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study. Blood. 2015;126(4):560-561. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-638593

15. Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Treatment target in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1555-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1301262

16. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):63-69. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010

17. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Hematocrit levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2533-2539. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03793-w

18. WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1332-e1345. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3.

19. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

20. Jakafi. Package insert. Incyte Corporation; 2020.

21. Gordeuk VR, Key NS, Prchal JT. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):653-658. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.210732

22. Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117(22):5857-5859. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-339002

23. Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87(6):1954-1959. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1954

24. Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):e87-e90. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.216267

25. Kroll MH, Michaelis LC, Verstovsek S. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in polycythemia vera. Blood Rev. 2015;29(4):215-221. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.002

26. Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057-1069. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1

27. Barosi G, Mesa R, Finazzi G, et al. Revised response criteria for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: an ELN and IWG-MRT consensus project. Blood. 2013;121(23):4778-4781. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-478891

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm affecting 44 to 57 individuals per 100,000 in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in hyperproliferation of mature myeloid lineage cells.2 Sustained erythrocytosis is a hallmark of PV, although many patients also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.2,3 These patients have increased inherent thrombotic risk with arterial events reported to occur at rates of 7 to 21/1000 person-years and venous thrombotic events at 5 to 20/1000 person-years.4-7 Thrombotic and cardiovascular events are leading causes of morbidity and mortality, resulting in a reduced overall survival of patients with PV compared with the general population.3,8-10

Blood Cell Counts and Thrombotic Events in PV

Treatment strategies for patients with PV mainly aim to prevent or manage thrombotic and bleeding complications through normalization of blood counts.11 Hematocrit (Hct) control has been reported to be associated with reduced thrombotic risk in patients with PV. This was shown and popularized by the prospective, randomized Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial in which participants were randomized 1:1 to maintaining either a low (< 45%) or high (45%-50%) Hct for 5 years to examine the long-term effects of more- or less-intensive cytoreductive therapy.12 Patients in the low-Hct group were found to have a lower rate of death from cardiovascular events or major thrombosis (1.1/100 person-years in the low-Hct group vs 4.4 in the high-Hct group; hazard ratio [HR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-10.53; P = .007). Likewise, cardiovascular events occurred at a lower rate in patients in the low-Hct group compared with the high-Hct group (4.4% vs 10.9% of patients, respectively; HR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.19-6.12; P = .02).12

Leukocytosis has also been linked to elevated risk for vascular events as shown in several studies, including the real-world European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) observational study and a post hoc subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study.13,14 In a multivariate, time-dependent analysis in ECLAP, patients with white blood cell (WBC) counts > 15 × 109/L had a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis compared with those who had lower WBC counts, with higher WBC count more strongly associated with arterial than venous thromboembolism.13 In CYTO-PV, a significant correlation between elevated WBC count (≥ 11 × 109/L vs reference level of < 7 × 109/L) and time-dependent risk of major thrombosis was shown (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.24-12.3; P = .02).14 Likewise, WBC count ≥ 11 × 109/L was found to be a predictor of subsequent venous events in a separate single-center multivariate analysis of patients with PV.8

Although CYTO-PV remains one of the largest prospective landmark studies in PV demonstrating the impact of Hct control on thrombosis, it is worthwhile to note that the patients in the high-Hct group who received less frequent myelosuppressive therapy with hydroxyurea than the low-Hct group also had higher WBC counts.12,15 Work is needed to determine the relative effects of high Hct and high WBC counts on PV independent of each other.

The Veteran Population with PV

Two recently published retrospective analyses from Parasuraman and colleagues used data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, with an aim to replicate findings from CYTO-PV in a real-world population.16,17 The 2 analyses focused independently on the effects of Hct control and WBC count on the risk of a thrombotic event in patients with PV.

In the first retrospective analysis, 213 patients with PV and no prior thrombosis were placed into groups based on whether Hct levels were consistently either < 45% or ≥ 45% throughout the study period.17 The mean follow-up time was 2.3 years, during which 44.1% of patients experienced a thrombotic event (Figure 1). Patients with Hct levels < 45% had a lower rate of thrombotic events compared to those with levels ≥ 45% (40.3% vs 54.2%, respectively; HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51; P = .04). In a sensitivity analysis that included patients with pre-index thrombotic events (N = 342), similar results were noted (55.6% vs 76.9% between the < 45% and ≥ 45% groups, respectively; HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46-2.61; P < .001).

In the second analysis, the authors investigated the relationship between WBC counts and thrombotic events.16 Evaluable patients (N = 1565) were grouped into 1 of 4 cohorts based on the last WBC measurement taken during the study period before a thrombotic event or through the end of follow-up: (1) WBC < 7.0 × 109/L, (2) 7.0 to 8.4 × 109/L, (3) 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L, or (4) ≥ 11.0 × 109/L. Mean follow-up time ranged from 3.6 to 4.5 years among WBC count cohorts, during which 24.9% of patients experienced a thrombotic event. Compared with the reference cohort (WBC < 7.0 × 109/L), a significant positive association between WBC counts and thrombotic event occurrence was observed among patients with WBC counts of 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96; P < .01) and ≥ 11 × 109/L (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.44-2.43; P < .001) (Figure 2).16 When including all patients in a sensitivity analysis regardless of whether they experienced thrombotic events before the index date (N = 1876), similar results were obtained (7.0-8.4 × 109/L group: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.97-1.55; P = .0959; 8.5 - 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81; P = .0062; ≥ 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001; compared with < 7.0 × 109/L reference group). Rates of phlebotomy and cytoreductive treatments were similar across groups.16

Some limitations to these studies are attributable to their retrospective design, reliance on health records, and the VHA population characteristics, which differ from the general population. For example, in this analysis, patients with PV in the VHA population had significantly increased risk of thrombotic events, even at a lower WBC count threshold (≥ 8.5 × 109/L) compared with those reported in CYTO-PV (≥ 11 × 109/L). Furthermore, approximately one-third of patients had elevated WBC levels, compared with 25.5% in the CYTO-PV study.14,16 This is most likely due to the unique nature of the VHA patient population, who are predominantly older adult men and generally have a higher comorbidity burden. A notable pre-index comorbidity burden was reported in the VHA population in the Hct analysis, even when compared to patients with PV in the general US population (Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 1.3 vs 0.8).6,17 Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use, which are most common among the VHA population, are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events.18,19 However, whether these higher levels of comorbidities affected the type of treatments they received was not elucidated, and the effectiveness of treatments to maintain target Hct levels was not addressed in the study.

Current PV Management and Future Implications

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology in myeloproliferative neoplasms recommend maintaining Hct levels < 45% in patients with PV.11 Patients with high-risk disease (age ≥ 60 years and/or history of thrombosis) are monitored for new thrombosis or bleeding and are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, they receive low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, and are managed with pharmacologic cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy primarily consists of hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a for younger patients. Ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor, is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as second-line treatment for those with PV that is intolerant or unresponsive to hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a treatments.11,20 However, the role of cytoreductive therapy is not clear for patients with low-risk disease (age < 60 years and no history of thrombosis). These patients are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors, undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, are maintained on low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), and are monitored for indications for cytoreductive therapy, which include any new thrombosis or disease-related major bleeding, frequent or persistent need for phlebotomy with poor tolerance for the procedure, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and disease-related symptoms (eg, aquagenic pruritus, night sweats, fatigue).

Even though the current guidelines recommend maintaining a target Hct of < 45% in patients with high-risk PV, the role of Hct as the main determinant of thrombotic risk in patients with PV is still debated.21 In JAK2V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia, Hct levels are usually normal but risk of thrombosis is nevertheless still significant.22 The risk of thrombosis is significantly lower in primary familial and congenital polycythemia and much lower in secondary erythrocytosis such as cyanotic heart disease, long-term native dwellers of high altitude, and those with high-oxygen–affinity hemoglobins.21,23 In secondary erythrocytosis from hypoxia or upregulated hypoxic pathway such as hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) mutation and Chuvash erythrocytosis, the risk of thrombosis is more associated with the upregulated HIF pathway and its downstream consequences, rather than the elevated Hct level.24

However, most current literature supports the association of increased risk of thrombosis with higher Hct and high WBC count in patients with PV. In addition, the underlying mechanism of thrombogenesis still remains elusive; it is likely a complex process that involves interactions among multiple components, including elevated blood counts arising from clonal hematopoiesis, JAK2V617F allele burden, and platelet and WBC activation and their interaction with endothelial cells and inflammatory cytokines.25

Nevertheless, Hct control and aspirin use are current standard of care for patients with PV to mitigate thrombotic risk, and the results from the 2 analyses by Parasuraman and colleagues, using real-world data from the VHA, support the current practice guidelines to maintain Hct < 45% in these patients. They also provide additional support for considering WBC counts when determining patient risk and treatment plans. Although treatment response criteria from the European LeukemiaNet include achieving normal WBC levels to decrease the risk of thrombosis, current NCCN guidelines do not include WBC counts as a component for establishing patient risk or provide a target WBC count to guide patient management.11,26,27 Updates to these practice guidelines may be warranted. In addition, further study is needed to understand the mechanism of thrombogenesis in PV and other myeloproliferative disorders in order to develop novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Tania Iqbal, PhD, an employee of ICON (North Wales, PA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE).

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare myeloproliferative neoplasm affecting 44 to 57 individuals per 100,000 in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by somatic mutations in the hematopoietic stem cell, resulting in hyperproliferation of mature myeloid lineage cells.2 Sustained erythrocytosis is a hallmark of PV, although many patients also have leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.2,3 These patients have increased inherent thrombotic risk with arterial events reported to occur at rates of 7 to 21/1000 person-years and venous thrombotic events at 5 to 20/1000 person-years.4-7 Thrombotic and cardiovascular events are leading causes of morbidity and mortality, resulting in a reduced overall survival of patients with PV compared with the general population.3,8-10

Blood Cell Counts and Thrombotic Events in PV

Treatment strategies for patients with PV mainly aim to prevent or manage thrombotic and bleeding complications through normalization of blood counts.11 Hematocrit (Hct) control has been reported to be associated with reduced thrombotic risk in patients with PV. This was shown and popularized by the prospective, randomized Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera (CYTO-PV) trial in which participants were randomized 1:1 to maintaining either a low (< 45%) or high (45%-50%) Hct for 5 years to examine the long-term effects of more- or less-intensive cytoreductive therapy.12 Patients in the low-Hct group were found to have a lower rate of death from cardiovascular events or major thrombosis (1.1/100 person-years in the low-Hct group vs 4.4 in the high-Hct group; hazard ratio [HR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-10.53; P = .007). Likewise, cardiovascular events occurred at a lower rate in patients in the low-Hct group compared with the high-Hct group (4.4% vs 10.9% of patients, respectively; HR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.19-6.12; P = .02).12

Leukocytosis has also been linked to elevated risk for vascular events as shown in several studies, including the real-world European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in PV (ECLAP) observational study and a post hoc subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study.13,14 In a multivariate, time-dependent analysis in ECLAP, patients with white blood cell (WBC) counts > 15 × 109/L had a significant increase in the risk of thrombosis compared with those who had lower WBC counts, with higher WBC count more strongly associated with arterial than venous thromboembolism.13 In CYTO-PV, a significant correlation between elevated WBC count (≥ 11 × 109/L vs reference level of < 7 × 109/L) and time-dependent risk of major thrombosis was shown (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.24-12.3; P = .02).14 Likewise, WBC count ≥ 11 × 109/L was found to be a predictor of subsequent venous events in a separate single-center multivariate analysis of patients with PV.8

Although CYTO-PV remains one of the largest prospective landmark studies in PV demonstrating the impact of Hct control on thrombosis, it is worthwhile to note that the patients in the high-Hct group who received less frequent myelosuppressive therapy with hydroxyurea than the low-Hct group also had higher WBC counts.12,15 Work is needed to determine the relative effects of high Hct and high WBC counts on PV independent of each other.

The Veteran Population with PV

Two recently published retrospective analyses from Parasuraman and colleagues used data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, with an aim to replicate findings from CYTO-PV in a real-world population.16,17 The 2 analyses focused independently on the effects of Hct control and WBC count on the risk of a thrombotic event in patients with PV.

In the first retrospective analysis, 213 patients with PV and no prior thrombosis were placed into groups based on whether Hct levels were consistently either < 45% or ≥ 45% throughout the study period.17 The mean follow-up time was 2.3 years, during which 44.1% of patients experienced a thrombotic event (Figure 1). Patients with Hct levels < 45% had a lower rate of thrombotic events compared to those with levels ≥ 45% (40.3% vs 54.2%, respectively; HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51; P = .04). In a sensitivity analysis that included patients with pre-index thrombotic events (N = 342), similar results were noted (55.6% vs 76.9% between the < 45% and ≥ 45% groups, respectively; HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.46-2.61; P < .001).

In the second analysis, the authors investigated the relationship between WBC counts and thrombotic events.16 Evaluable patients (N = 1565) were grouped into 1 of 4 cohorts based on the last WBC measurement taken during the study period before a thrombotic event or through the end of follow-up: (1) WBC < 7.0 × 109/L, (2) 7.0 to 8.4 × 109/L, (3) 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L, or (4) ≥ 11.0 × 109/L. Mean follow-up time ranged from 3.6 to 4.5 years among WBC count cohorts, during which 24.9% of patients experienced a thrombotic event. Compared with the reference cohort (WBC < 7.0 × 109/L), a significant positive association between WBC counts and thrombotic event occurrence was observed among patients with WBC counts of 8.5 to < 11.0 × 109/L (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96; P < .01) and ≥ 11 × 109/L (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.44-2.43; P < .001) (Figure 2).16 When including all patients in a sensitivity analysis regardless of whether they experienced thrombotic events before the index date (N = 1876), similar results were obtained (7.0-8.4 × 109/L group: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.97-1.55; P = .0959; 8.5 - 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10-1.81; P = .0062; ≥ 11.0 × 109/L group: HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P < .001; compared with < 7.0 × 109/L reference group). Rates of phlebotomy and cytoreductive treatments were similar across groups.16

Some limitations to these studies are attributable to their retrospective design, reliance on health records, and the VHA population characteristics, which differ from the general population. For example, in this analysis, patients with PV in the VHA population had significantly increased risk of thrombotic events, even at a lower WBC count threshold (≥ 8.5 × 109/L) compared with those reported in CYTO-PV (≥ 11 × 109/L). Furthermore, approximately one-third of patients had elevated WBC levels, compared with 25.5% in the CYTO-PV study.14,16 This is most likely due to the unique nature of the VHA patient population, who are predominantly older adult men and generally have a higher comorbidity burden. A notable pre-index comorbidity burden was reported in the VHA population in the Hct analysis, even when compared to patients with PV in the general US population (Charlson Comorbidity Index score, 1.3 vs 0.8).6,17 Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use, which are most common among the VHA population, are independently associated with higher risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events.18,19 However, whether these higher levels of comorbidities affected the type of treatments they received was not elucidated, and the effectiveness of treatments to maintain target Hct levels was not addressed in the study.

Current PV Management and Future Implications

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in oncology in myeloproliferative neoplasms recommend maintaining Hct levels < 45% in patients with PV.11 Patients with high-risk disease (age ≥ 60 years and/or history of thrombosis) are monitored for new thrombosis or bleeding and are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, they receive low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, and are managed with pharmacologic cytoreductive therapy. Cytoreductive therapy primarily consists of hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a for younger patients. Ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK1)/JAK2 inhibitor, is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as second-line treatment for those with PV that is intolerant or unresponsive to hydroxyurea or peginterferon alfa-2a treatments.11,20 However, the role of cytoreductive therapy is not clear for patients with low-risk disease (age < 60 years and no history of thrombosis). These patients are managed for their cardiovascular risk factors, undergo phlebotomy to maintain an Hct < 45%, are maintained on low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/day), and are monitored for indications for cytoreductive therapy, which include any new thrombosis or disease-related major bleeding, frequent or persistent need for phlebotomy with poor tolerance for the procedure, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and disease-related symptoms (eg, aquagenic pruritus, night sweats, fatigue).

Even though the current guidelines recommend maintaining a target Hct of < 45% in patients with high-risk PV, the role of Hct as the main determinant of thrombotic risk in patients with PV is still debated.21 In JAK2V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia, Hct levels are usually normal but risk of thrombosis is nevertheless still significant.22 The risk of thrombosis is significantly lower in primary familial and congenital polycythemia and much lower in secondary erythrocytosis such as cyanotic heart disease, long-term native dwellers of high altitude, and those with high-oxygen–affinity hemoglobins.21,23 In secondary erythrocytosis from hypoxia or upregulated hypoxic pathway such as hypoxia inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) mutation and Chuvash erythrocytosis, the risk of thrombosis is more associated with the upregulated HIF pathway and its downstream consequences, rather than the elevated Hct level.24

However, most current literature supports the association of increased risk of thrombosis with higher Hct and high WBC count in patients with PV. In addition, the underlying mechanism of thrombogenesis still remains elusive; it is likely a complex process that involves interactions among multiple components, including elevated blood counts arising from clonal hematopoiesis, JAK2V617F allele burden, and platelet and WBC activation and their interaction with endothelial cells and inflammatory cytokines.25

Nevertheless, Hct control and aspirin use are current standard of care for patients with PV to mitigate thrombotic risk, and the results from the 2 analyses by Parasuraman and colleagues, using real-world data from the VHA, support the current practice guidelines to maintain Hct < 45% in these patients. They also provide additional support for considering WBC counts when determining patient risk and treatment plans. Although treatment response criteria from the European LeukemiaNet include achieving normal WBC levels to decrease the risk of thrombosis, current NCCN guidelines do not include WBC counts as a component for establishing patient risk or provide a target WBC count to guide patient management.11,26,27 Updates to these practice guidelines may be warranted. In addition, further study is needed to understand the mechanism of thrombogenesis in PV and other myeloproliferative disorders in order to develop novel therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was provided by Tania Iqbal, PhD, an employee of ICON (North Wales, PA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE).

1. Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595-600. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.813500

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

3. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1874-1881. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.163

4. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R, et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2224-2232. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062

5. Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110(3):840-846. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287

6. Goyal RK, Davis KL, Cote I, Mounedji N, Kaye JA. Increased incidence of thromboembolic event rates in patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera: results from an observational cohort study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2014;124:4840. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.4840.4840

7. Barbui T, Carobbio A, Rumi E, et al. In contemporary patients with polycythemia vera, rates of thrombosis and risk factors delineate a new clinical epidemiology. Blood. 2014;124(19):3021-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-591610 8. Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, et al. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(12):662. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6

9. Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV. Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, and emerging treatment options. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):1965-1976. doi:10.1007/s00277-014-2205-y

10. Hultcrantz M, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM-L, et al. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2995-3001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1925

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in myeloproliferative neoplasms (Version 1.2020). Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

12. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

13. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Barbui T, et al. Leukocytosis as a major thrombotic risk factor in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2007;109(6):2446-2452. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-042515

14. Barbui T, Masciulli A, Marfisi MR, et al. White blood cell counts and thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study. Blood. 2015;126(4):560-561. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-638593

15. Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Treatment target in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1555-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1301262

16. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):63-69. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010

17. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Hematocrit levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2533-2539. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03793-w

18. WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1332-e1345. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3.

19. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

20. Jakafi. Package insert. Incyte Corporation; 2020.

21. Gordeuk VR, Key NS, Prchal JT. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):653-658. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.210732

22. Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117(22):5857-5859. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-339002

23. Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87(6):1954-1959. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1954

24. Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):e87-e90. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.216267

25. Kroll MH, Michaelis LC, Verstovsek S. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in polycythemia vera. Blood Rev. 2015;29(4):215-221. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.002

26. Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057-1069. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1

27. Barosi G, Mesa R, Finazzi G, et al. Revised response criteria for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: an ELN and IWG-MRT consensus project. Blood. 2013;121(23):4778-4781. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-478891

1. Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):595-600. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.813500

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

3. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1874-1881. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.163

4. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R, et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2224-2232. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.062

5. Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, et al. Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V>F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110(3):840-846. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287

6. Goyal RK, Davis KL, Cote I, Mounedji N, Kaye JA. Increased incidence of thromboembolic event rates in patients diagnosed with polycythemia vera: results from an observational cohort study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2014;124:4840. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.4840.4840

7. Barbui T, Carobbio A, Rumi E, et al. In contemporary patients with polycythemia vera, rates of thrombosis and risk factors delineate a new clinical epidemiology. Blood. 2014;124(19):3021-3023. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-07-591610 8. Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, et al. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(12):662. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6

9. Stein BL, Moliterno AR, Tiu RV. Polycythemia vera disease burden: contributing factors, impact on quality of life, and emerging treatment options. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):1965-1976. doi:10.1007/s00277-014-2205-y

10. Hultcrantz M, Kristinsson SY, Andersson TM-L, et al. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2995-3001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1925

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in myeloproliferative neoplasms (Version 1.2020). Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf

12. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

13. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Barbui T, et al. Leukocytosis as a major thrombotic risk factor in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood. 2007;109(6):2446-2452. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-042515

14. Barbui T, Masciulli A, Marfisi MR, et al. White blood cell counts and thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a subanalysis of the CYTO-PV study. Blood. 2015;126(4):560-561. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-638593

15. Prchal JT, Gordeuk VR. Treatment target in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1555-1556. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1301262

16. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Elevated white blood cell levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: a real-world analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):63-69. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.11.010

17. Parasuraman S, Yu J, Paranagama D, et al. Hematocrit levels and thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera: an analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2533-2539. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03793-w

18. WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1332-e1345. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3.

19. D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

20. Jakafi. Package insert. Incyte Corporation; 2020.

21. Gordeuk VR, Key NS, Prchal JT. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):653-658. doi:10.3324/haematol.2018.210732

22. Carobbio A, Thiele J, Passamonti F, et al. Risk factors for arterial and venous thrombosis in WHO-defined essential thrombocythemia: an international study of 891 patients. Blood. 2011;117(22):5857-5859. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-339002

23. Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87(6):1954-1959. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1954

24. Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105(3):e87-e90. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.216267

25. Kroll MH, Michaelis LC, Verstovsek S. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in polycythemia vera. Blood Rev. 2015;29(4):215-221. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2014.12.002

26. Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1057-1069. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0077-1

27. Barosi G, Mesa R, Finazzi G, et al. Revised response criteria for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: an ELN and IWG-MRT consensus project. Blood. 2013;121(23):4778-4781. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-478891

Characterizing Opioid Response in Older Veterans in the Post-Acute Setting

Older adults admitted to post-acute settings frequently have complex rehabilitation needs and multimorbidity, which predisposes them to pain management challenges.1,2 The prevalence of pain in post-acute and long-term care is as high as 65%, and opioid use is common among this population with 1 in 7 residents receiving long-term opioids.3,4

Opioids that do not adequately control pain represent a missed opportunity for deprescribing. There is limited evidence regarding efficacy of long-term opioid use (> 90 days) for improving pain and physical functioning.5 In addition, long-term opioid use carries significant risks, including overdose-related death, dependence, and increased emergency department visits.5 These risks are likely to be pronounced among veterans receiving post-acute care (PAC) who are older, have comorbid psychiatric disorders, are prescribed several centrally acting medications, and experience substance use disorder (SUD).6

Older adults are at increased risk for opioid toxicity because of reduced drug clearance and smaller therapeutic window.5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend frequently assessing patients for benefit in terms of sustained improvement in pain as well as physical function.5 If pain and functional improvements are minimal, opioid use and nonopioid pain management strategies should be considered. Some patients will struggle with this approach. Directly asking patients about the effectiveness of opioids is challenging. Opioid users with chronic pain frequently report problems with opioids even as they describe them as indispensable for pain management.7,8

Earlier studies have assessed patient perspectives regarding opioid difficulties as well as their helpfulness, which could introduce recall bias. Patient-level factors that contribute to a global sense of distress, in addition to the presence of painful physical conditions, also could contribute to patients requesting opioids without experiencing adequate pain relief. One study in veterans residing in PAC facilities found that individuals with depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and SUD were more likely to report pain and receive scheduled analgesics; this effect persisted in individuals with PTSD even after adjusting for demographic and functional status variables.9 The study looked only at analgesics as a class and did not examine opioids specifically. It is possible that distressed individuals, such as those with uncontrolled depression, PTSD, and SUD, might be more likely to report high pain levels and receive opioids with inadequate benefit and increased risk. Identifying the primary condition causing distress and targeting treatment to that condition (ie, depression) is preferable to escalating opioids in an attempt to treat pain in the context of nonresponse. Assessing an individual’s aggregate response to opioids rather than relying on a single self-report is a useful addition to current pain management strategies.

The goal of this study was to pilot a method of identifying opioid-nonresponsive pain using administrative data, measure its prevalence in a PAC population of veterans, and explore clinical and demographic correlates with particular attention to variates that could indicate high levels of psychological and physical distress. Identifying pain that is poorly responsive to opioids would give clinicians the opportunity to avoid or minimize opioid use and prioritize treatments that are likely to improve the resident’s pain, quality of life, and physical function while minimizing recall bias. We hypothesized that pain that responds poorly to opioids would be prevalent among veterans residing in a PAC unit. We considered that veterans with pain poorly responsive to opioids would be more likely to have factors that would place them at increased risk of adverse effects, such as comorbid psychiatric conditions, history of SUD, and multimorbidity, providing further rationale for clinical equipoise in that population.6

Methods

This was a small, retrospective cross-sectional study using administrative data and chart review. The study included veterans who were administered opioids while residing in a single US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) community living center PAC (CLC-PAC) unit during at least 1 of 4 nonconsecutive, random days in 2016 and 2017. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Ann Arbor VA Health System (#2017-1034) as part of a larger project involving models of care in vulnerable older veterans.

Inclusion criteria were the presence of at least moderate pain (≥ 4 on a 0 to 10 scale); receiving ≥ 2 opioids ordered as needed over the prespecified 24-hour observation period; and having ≥ 2 pre-and postopioid administration pain scores during the observation period. Veterans who did not meet these criteria were excluded. At the time of initial sample selection, we did not capture information related to coprescribed analgesics, including a standing order of opioids. To obtain the sample, we initially characterized all veterans on the 4 days residing in the CLC-PAC unit as those reporting at least moderate pain (≥ 4) and those who reported no or mild pain (< 4). The cut point of 4 of 10 is consistent with moderate pain based on earlier work showing higher likelihood of pain that interferes with physical function.10 We then restricted the sample to veterans who received ≥ 2 opioids ordered as needed for pain and had ≥ 2 pre- and postopioid administration numeric pain rating scores during the 24-hour observation period. This methodology was chosen to enrich our sample for those who received opioids regularly for ongoing pain. Opioids were defined as full µ-opioid receptor agonists and included hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, tramadol, and methadone.

Medication administration data were obtained from the VA corporate data warehouse, which houses all barcode medication administration data collected at the point of care. The dataset includes pain scores gathered by nursing staff before and after administering an as-needed analgesic. The corporate data warehouse records data/time of pain scores and the analgesic name, dosage, formulation, and date/time of administration. Using a standardized assessment form developed iteratively, we calculated opioid dosage in oral morphine equivalents (OME) for comparison.11,12 All abstracted data were reexamined for accuracy. Data initially were collected in an anonymized, blinded fashion. Participants were then unblinded for chart review. Initial data was captured in resident-days instead of unique residents because an individual resident might have been admitted on several observation days. We were primarily interested in how pain responded to opioids administered in response to resident request; therefore, we did not examine response to opioids that were continuously ordered (ie, scheduled). We did consider scheduled opioids when calculating total daily opioid dosage during the chart review.

Outcome of Interest

The primary outcome of interest was an individual’s response to as-needed opioids, which we defined as change in the pain score after opioid administration. The pre-opioid pain score was the score that immediately preceded administration of an as-needed opioid. The postopioid administration pain score was the first score after opioid administration if obtained within 3 hours of administration. Scores collected > 3 hours after opioid administration were excluded because they no longer accurately reflected the impact of the opioid due to the short half-lives. Observations were excluded if an opioid was administered without a recorded pain score; this occurred once for 6 individuals. Observations also were excluded if an opioid was administered but the data were captured on the following day (outside of the 24-hour window); this occurred once for 3 individuals.

We calculated a ∆ score by subtracting the postopioid pain rating score from the pre-opioid score. Individual ∆ scores were then averaged over the 24-hour period (range, 2-5 opioid doses). For example, if an individual reported a pre-opioid pain score of 10, and a postopioid pain score of 2, the ∆ was recorded as 8. If the individual’s next pre-opioid score was 10, and post-opioid score was 6, the ∆ was recorded as 4. ∆ scores over the 24-hour period were averaged together to determine that individual’s response to as-needed opioids. In the previous example, the mean ∆ score is 6. Lower mean ∆ scores reflect decreased responsiveness to opioids’ analgesic effect.

Demographic and clinical data were obtained from electronic health record review using a standardized assessment form. These data included information about medical and psychiatric comorbidities, specialist consultations, and CLC-PAC unit admission indications and diagnoses. Medications of interest were categorized as antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, hypnotics, stimulants, antiepileptic drugs/mood stabilizers (including gabapentin and pregabalin), and all adjuvant analgesics. Adjuvant analgesics were defined as medications administered for pain as documented by chart notes or those ordered as needed for pain, and analyzed as a composite variable. Antidepressants with analgesic properties (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants) were considered adjuvant analgesics. Psychiatric information collected included presence of mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders, and PTSD. SUD information was collected separately from other psychiatric disorders.

Analyses

The study population was described using tabulations for categorical data and means and standard deviations for continuous data. Responsiveness to opioids was analyzed as a continuous variable. Those with higher mean ∆ scores were considered to have pain relatively more responsive to opioids, while lower mean ∆ scores indicated pain less responsive to opioids. We constructed linear regression models controlling for average pre-opioid pain rating scores to explore associations between opioid responsiveness and variables of interest. All analyses were completed using Stata version 15. This study was not adequately powered to detect differences across the spectrum of opioid responsiveness, although the authors have reported differences in this article.

Results

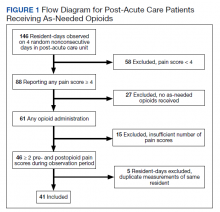

Over the 4-day observational period there were 146 resident-days. Of these, 88 (60.3%) reported at least 1 pain score of ≥ 4. Of those, 61 (41.8%) received ≥ 1 as-needed opioid for pain. We identified 46 resident-days meeting study criteria of ≥ 2 pre- and postanalgesic scores. We identified 41 unique individuals (Figure 1). Two individuals were admitted to the CLC-PAC unit on 2 of the 4 observation days, and 1 individual was admitted to the CLC-PAC unit on 3 of the 4 observation days. For individuals admitted several days, we included data only from the initial observation day.

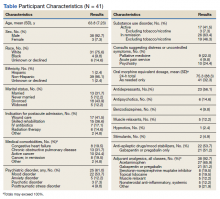

Response to opioids varied greatly in this sample. The mean (SD) ∆ pain score was 3.4 (1.6) and ranged from 0.5 to 6.3. Using linear regression, we found no relationship between admission indication, medical comorbidities (including active cancer), and opioid responsiveness (Table).

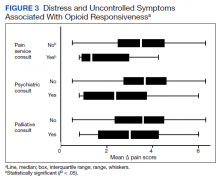

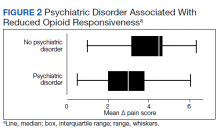

Psychiatric disorders were highly prevalent, with 25 individuals (61.0%) having ≥ 1 any psychiatric diagnosis identified on chart review. The presence of any psychiatric diagnosis was significantly associated with reduced responsiveness to opioids (β = −1.08; 95% CI, −2.04 to −0.13; P = .03). SUDs also were common, with 17 individuals (41.5%) having an active SUD; most were tobacco/nicotine. Twenty-six veterans (63.4%) had documentation of SUD in remission with 19 (46.3%) for substances other than tobacco/nicotine. There was no indication that any veteran in the sample was prescribed medication for opioid use disorder (OUD) at the time of observation. There was no relationship between opioid responsiveness and SUDs, neither active or in remission. Consults to other services that suggested distress or difficult-to-control symptoms also were frequent. Consults to the pain service were significantly associated with reduced responsiveness to opioids (β = −1.75; 95% CI, −3.33 to −0.17; P = .03). Association between psychiatry consultation and reduced opioid responsiveness trended toward significance (β = −0.95; 95% CI, −2.06 to 0.17; P = .09) (Figures 2 and 3). There was no significant association with palliative medicine consultation and opioid responsiveness.

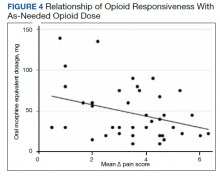

A poorer response to opioids was associated with a significantly higher as-needed opioid dosage (β = −0.02; 95% CI, −0.04 to −0.01; P = .002) as well as a trend toward higher total opioid dosage (β = −0.005; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.0003; P = .06) (Figure 4). Thirty-eight (92.7%) participants received nonopioid adjuvant analgesics for pain. More than half (56.1%) received antidepressants or gabapentinoids (51.2%), although we did not assess whether they were prescribed for pain or another indication. We did not identify a relationship between any specific psychoactive drug class and opioid responsiveness in this sample.

Discussion

This exploratory study used readily available administrative data in a CLC-PAC unit to assess responsiveness to opioids via a numeric mean ∆ score, with higher values indicating more pain relief in response to opioids. We then constructed linear regression models to characterize the relationship between the mean ∆ score and factors known to be associated with difficult-to-control pain and psychosocial distress. As expected, opioid responsiveness was highly variable among residents; some residents experienced essentially no reduction in pain, on average, despite receiving opioids. Psychiatric comorbidity, higher dosage in OMEs, and the presence of a pain service consult significantly correlated with poorer response to opioids. To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify opioid responsiveness and describe the relationship with clinical correlates in the understudied PAC population.

Earlier research has demonstrated a relationship between the presence of psychiatric disorders and increased likelihood of receiving any analgesics among veterans residing in PAC.9 Our study adds to the literature by quantifying opioid response using readily available administrative data and examining associations with psychiatric diagnoses. These findings highlight the possibility that attempting to treat high levels of pain by escalating the opioid dosage in patients with a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis should be re-addressed, particularly if there is no meaningful pain reduction at lower opioid dosages. Our sample had a variety of admission diagnoses and medical comorbidities, however, we did not identify a relationship with opioid responsiveness, including an active cancer diagnosis. Although SUDs were highly prevalent in our sample, there was no relationship with opioid responsiveness. This suggests that lack of response to opioids is not merely a matter of drug tolerance or an indication of drug-seeking behavior.

Factors Impacting Response