User login

Does giving moms cash make babies smarter?

In his first State of the Union address in early March, President Joe Biden broached a tax policy question that neuroscientists and pediatricians also see as a scientific one.

President Biden urged lawmakers to extend the Child Tax Credit “so no one has to raise a family in poverty.”

Apart from the usual political and budgetary calculus, physicians and social scientists are actively examining the ramifications that such policies could have on child development and long-term health outcomes.

To do so, they have turned to brain scans and rigorous studies to better understand the effects of being raised in poverty and whether giving families more cash makes a difference.

Initial results from an ongoing study known as Baby’s First Years suggest that providing extra money to mothers may influence brain activity in infants in ways that reflect improvements in cognitive ability.

Researchers, doctors, and advocates say the findings cement the case for policies such as the expanded Child Tax Credit. Others argue that reducing child poverty is a social good on its own, regardless of what brain scans show.

The new findings were published Jan. 24 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), as lawmakers were weighing whether to resume an expansion of the tax credit, which had temporarily provided monthly payments akin to the $333 a month looked at in the study.

The expiration of the expanded credit in December left some 3.6 million more children in poverty, bringing the total number to more than 12.5 million and pushing the child poverty rate to 17%.

Philanthropists and research teams have partnered to conduct other guaranteed income experiments around the United States, including one in New York called the Bridge Project, which is evaluating different levels of financial support for mothers with babies.

Some mothers are receiving $500 per month, others twice that amount.

Angelina Matos, 18, receives $1,000 a month, allowing her to attend college and pay for necessities like diapers, clothes, and toys for her nearly 1-year-old daughter.

As one of 600 mothers participating in the project, Ms. Matos periodically answers questions about her daughter’s progress, like whether she is eating solid foods.

Megha Agarwal, BS, executive director of the Bridge Project and its funder the Monarch Foundation, said she was thrilled to see the early results from Baby’s First Years. “We are looking for ways in which we can strengthen our future generations,” she said. “It is exciting to see that direct cash and a guaranteed income might be part of the solution.”

A scientific perspective

Growing up in poverty is well-known to increase the likelihood of lower academic achievement and chronic conditions such as asthma and obesity. Relative to higher income levels, poverty is associated with differences in the structure and function of the developing brain. But whether interventions to reduce poverty can influence how newborns develop is less clear.

“There would be plenty of people who would say, ‘Well, it’s not poverty. It’s all the things associated with poverty. It’s the choices you make that are actually leading to differences in outcomes,’” said Kimberly Noble, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at Columbia University, New York, and a coauthor of the PNAS study. Regardless of ideology, she said, the best way to address that question from a scientific perspective is through a randomized controlled trial.

“You can’t, and wouldn’t want to, randomize kids to living in poverty or not, but you can take a group of families who are unfortunately living in poverty and randomize them to receive different levels of economic support,” Dr. Noble said.

$333 per month

Baby’s First Years has done just that. Researchers gave 1,000 low-income mothers with newborns a cash gift of $333 per month or a smaller gift of $20 per month, disbursed on debit cards, starting in 2018. Participants live in four metropolitan areas – New York City, greater New Orleans, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, and Omaha – and were recruited at the time of their child’s birth. Investigators currently have funding to continue the cash support until the children turn 4 years old.

When the infants were about 1 year old, investigators measured their resting brain activity using EEG.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the ability to conduct in-person testing, so the number of children with EEG data was smaller than planned. Still, the researchers analyzed data from 251 kids in the group that received the smaller cash gift and 184 kids in the group that received the larger amount. Patterns of brain activity largely tracked those seen in earlier observational studies: more mid- and high-frequency activity (alpha-, beta-, and gamma-bands) and less low-frequency activity (theta-bands) among children in the households that received more money.

Faster brain activity is associated with better scores on measures of language, cognition, and social-emotional development. Slower activity has been linked to problems with behavior, attention, and learning.

“We predicted that our poverty reduction intervention would mitigate the neurobiological signal of poverty,” Dr. Noble said. “And that’s exactly what we report in this paper.”

The study builds on decades of work showing that poverty can harm child development, said Joan Luby, MD, with Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, who served as a peer reviewer for the PNAS paper.

More follow-up data and information about the babies’ cognitive function and behavior over time are needed, but the study shows a signal that cannot be ignored, Dr. Luby said.

Dr. Luby began exploring the effects of poverty on brain development in earnest while working on a study that was meant to focus on another variable altogether: early childhood depression. The investigators on that 2013 study found that poverty had a “very, very big effect in our sample, and we realized we had to learn more about it,” she said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics likewise has recognized poverty as an important determinant of health. A policy statement that the group published in 2016 and reaffirmed in 2021 outlines ways pediatricians and social programs can address poverty.

Benard Dreyer, MD, director of pediatrics at Bellevue Hospital, New York, was president of the AAP when it published this guidance.

One lingering question has been how much low income worsens educational outcomes, Dr. Dreyer said. Perhaps other issues, such as single motherhood, a lack of parental education, or living in neighborhoods with more crime may be the cause. If so, simply giving more money to parents might not overcome those barriers.

Natural experiments have hinted that money itself can influence child development. For example, families on an American Indian reservation in North Carolina started receiving a share of casino profits after a casino opened there.

The new infusion of funds arrived in the middle of a study in which researchers were examining the development of mental illness in children.

Among children who were no longer poor as a result of the casino payments, symptoms of conduct and oppositional defiant disorders decreased.

Guaranteeing income

How extra money affects families across different levels of income also interests researchers and policymakers.

“One of the policy debates in Washington is to what degree should it be to everyone,” Ajay Chaudry, PhD, a research scholar at New York University who is advising the Bridge Project, said.

Guaranteed income programs may need to be available to most of the population out of political necessity, even if the benefits turn out to be the most pronounced at lower income levels, added Dr. Chaudry, who served in the Obama administration as deputy assistant secretary for human services policy.

If giving moms money affects babies’ brains, Dr. Dreyer pointed to two pathways that could explain the link: more resources and less family stress.

Money helps families buy toys and books, which in turn could support a child’s cognitive development. Meanwhile, low-income mothers and fathers may experience worries about eviction, adequate food, and the loss of heat and electricity, which could detract from their ability to parent.

Of course, many ways to support a child’s development do not require money. Engaging with children in a warm and nurturing way, having conversations with them, and reading with them are all important.

If the pattern in the PNAS study holds, individual experiences and outcomes will still vary, Dr. Noble said. Many children in the group that received the smaller gift had fast-paced brain activity, whereas some babies in the group that received the larger gift showed slower brain activity. Knowing family income would not allow you to accurately predict anything about an individual child’s brain, Dr. Noble said.

“I certainly wouldn’t want the message to be that money is the only thing that matters,” Dr. Noble said. “Money is something that can be easily manipulated by policy, which is why I think this is important.”

For the 18-year-old new mom Ms. Matos, accepting assistance “makes me feel less of myself. But honestly, I feel like mothers shouldn’t be afraid to ask for help or reach out for help or apply to programs like these.”

The sources reported a variety of funders, including federal agencies and foundations and donors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In his first State of the Union address in early March, President Joe Biden broached a tax policy question that neuroscientists and pediatricians also see as a scientific one.

President Biden urged lawmakers to extend the Child Tax Credit “so no one has to raise a family in poverty.”

Apart from the usual political and budgetary calculus, physicians and social scientists are actively examining the ramifications that such policies could have on child development and long-term health outcomes.

To do so, they have turned to brain scans and rigorous studies to better understand the effects of being raised in poverty and whether giving families more cash makes a difference.

Initial results from an ongoing study known as Baby’s First Years suggest that providing extra money to mothers may influence brain activity in infants in ways that reflect improvements in cognitive ability.

Researchers, doctors, and advocates say the findings cement the case for policies such as the expanded Child Tax Credit. Others argue that reducing child poverty is a social good on its own, regardless of what brain scans show.

The new findings were published Jan. 24 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), as lawmakers were weighing whether to resume an expansion of the tax credit, which had temporarily provided monthly payments akin to the $333 a month looked at in the study.

The expiration of the expanded credit in December left some 3.6 million more children in poverty, bringing the total number to more than 12.5 million and pushing the child poverty rate to 17%.

Philanthropists and research teams have partnered to conduct other guaranteed income experiments around the United States, including one in New York called the Bridge Project, which is evaluating different levels of financial support for mothers with babies.

Some mothers are receiving $500 per month, others twice that amount.

Angelina Matos, 18, receives $1,000 a month, allowing her to attend college and pay for necessities like diapers, clothes, and toys for her nearly 1-year-old daughter.

As one of 600 mothers participating in the project, Ms. Matos periodically answers questions about her daughter’s progress, like whether she is eating solid foods.

Megha Agarwal, BS, executive director of the Bridge Project and its funder the Monarch Foundation, said she was thrilled to see the early results from Baby’s First Years. “We are looking for ways in which we can strengthen our future generations,” she said. “It is exciting to see that direct cash and a guaranteed income might be part of the solution.”

A scientific perspective

Growing up in poverty is well-known to increase the likelihood of lower academic achievement and chronic conditions such as asthma and obesity. Relative to higher income levels, poverty is associated with differences in the structure and function of the developing brain. But whether interventions to reduce poverty can influence how newborns develop is less clear.

“There would be plenty of people who would say, ‘Well, it’s not poverty. It’s all the things associated with poverty. It’s the choices you make that are actually leading to differences in outcomes,’” said Kimberly Noble, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at Columbia University, New York, and a coauthor of the PNAS study. Regardless of ideology, she said, the best way to address that question from a scientific perspective is through a randomized controlled trial.

“You can’t, and wouldn’t want to, randomize kids to living in poverty or not, but you can take a group of families who are unfortunately living in poverty and randomize them to receive different levels of economic support,” Dr. Noble said.

$333 per month

Baby’s First Years has done just that. Researchers gave 1,000 low-income mothers with newborns a cash gift of $333 per month or a smaller gift of $20 per month, disbursed on debit cards, starting in 2018. Participants live in four metropolitan areas – New York City, greater New Orleans, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, and Omaha – and were recruited at the time of their child’s birth. Investigators currently have funding to continue the cash support until the children turn 4 years old.

When the infants were about 1 year old, investigators measured their resting brain activity using EEG.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the ability to conduct in-person testing, so the number of children with EEG data was smaller than planned. Still, the researchers analyzed data from 251 kids in the group that received the smaller cash gift and 184 kids in the group that received the larger amount. Patterns of brain activity largely tracked those seen in earlier observational studies: more mid- and high-frequency activity (alpha-, beta-, and gamma-bands) and less low-frequency activity (theta-bands) among children in the households that received more money.

Faster brain activity is associated with better scores on measures of language, cognition, and social-emotional development. Slower activity has been linked to problems with behavior, attention, and learning.

“We predicted that our poverty reduction intervention would mitigate the neurobiological signal of poverty,” Dr. Noble said. “And that’s exactly what we report in this paper.”

The study builds on decades of work showing that poverty can harm child development, said Joan Luby, MD, with Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, who served as a peer reviewer for the PNAS paper.

More follow-up data and information about the babies’ cognitive function and behavior over time are needed, but the study shows a signal that cannot be ignored, Dr. Luby said.

Dr. Luby began exploring the effects of poverty on brain development in earnest while working on a study that was meant to focus on another variable altogether: early childhood depression. The investigators on that 2013 study found that poverty had a “very, very big effect in our sample, and we realized we had to learn more about it,” she said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics likewise has recognized poverty as an important determinant of health. A policy statement that the group published in 2016 and reaffirmed in 2021 outlines ways pediatricians and social programs can address poverty.

Benard Dreyer, MD, director of pediatrics at Bellevue Hospital, New York, was president of the AAP when it published this guidance.

One lingering question has been how much low income worsens educational outcomes, Dr. Dreyer said. Perhaps other issues, such as single motherhood, a lack of parental education, or living in neighborhoods with more crime may be the cause. If so, simply giving more money to parents might not overcome those barriers.

Natural experiments have hinted that money itself can influence child development. For example, families on an American Indian reservation in North Carolina started receiving a share of casino profits after a casino opened there.

The new infusion of funds arrived in the middle of a study in which researchers were examining the development of mental illness in children.

Among children who were no longer poor as a result of the casino payments, symptoms of conduct and oppositional defiant disorders decreased.

Guaranteeing income

How extra money affects families across different levels of income also interests researchers and policymakers.

“One of the policy debates in Washington is to what degree should it be to everyone,” Ajay Chaudry, PhD, a research scholar at New York University who is advising the Bridge Project, said.

Guaranteed income programs may need to be available to most of the population out of political necessity, even if the benefits turn out to be the most pronounced at lower income levels, added Dr. Chaudry, who served in the Obama administration as deputy assistant secretary for human services policy.

If giving moms money affects babies’ brains, Dr. Dreyer pointed to two pathways that could explain the link: more resources and less family stress.

Money helps families buy toys and books, which in turn could support a child’s cognitive development. Meanwhile, low-income mothers and fathers may experience worries about eviction, adequate food, and the loss of heat and electricity, which could detract from their ability to parent.

Of course, many ways to support a child’s development do not require money. Engaging with children in a warm and nurturing way, having conversations with them, and reading with them are all important.

If the pattern in the PNAS study holds, individual experiences and outcomes will still vary, Dr. Noble said. Many children in the group that received the smaller gift had fast-paced brain activity, whereas some babies in the group that received the larger gift showed slower brain activity. Knowing family income would not allow you to accurately predict anything about an individual child’s brain, Dr. Noble said.

“I certainly wouldn’t want the message to be that money is the only thing that matters,” Dr. Noble said. “Money is something that can be easily manipulated by policy, which is why I think this is important.”

For the 18-year-old new mom Ms. Matos, accepting assistance “makes me feel less of myself. But honestly, I feel like mothers shouldn’t be afraid to ask for help or reach out for help or apply to programs like these.”

The sources reported a variety of funders, including federal agencies and foundations and donors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In his first State of the Union address in early March, President Joe Biden broached a tax policy question that neuroscientists and pediatricians also see as a scientific one.

President Biden urged lawmakers to extend the Child Tax Credit “so no one has to raise a family in poverty.”

Apart from the usual political and budgetary calculus, physicians and social scientists are actively examining the ramifications that such policies could have on child development and long-term health outcomes.

To do so, they have turned to brain scans and rigorous studies to better understand the effects of being raised in poverty and whether giving families more cash makes a difference.

Initial results from an ongoing study known as Baby’s First Years suggest that providing extra money to mothers may influence brain activity in infants in ways that reflect improvements in cognitive ability.

Researchers, doctors, and advocates say the findings cement the case for policies such as the expanded Child Tax Credit. Others argue that reducing child poverty is a social good on its own, regardless of what brain scans show.

The new findings were published Jan. 24 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), as lawmakers were weighing whether to resume an expansion of the tax credit, which had temporarily provided monthly payments akin to the $333 a month looked at in the study.

The expiration of the expanded credit in December left some 3.6 million more children in poverty, bringing the total number to more than 12.5 million and pushing the child poverty rate to 17%.

Philanthropists and research teams have partnered to conduct other guaranteed income experiments around the United States, including one in New York called the Bridge Project, which is evaluating different levels of financial support for mothers with babies.

Some mothers are receiving $500 per month, others twice that amount.

Angelina Matos, 18, receives $1,000 a month, allowing her to attend college and pay for necessities like diapers, clothes, and toys for her nearly 1-year-old daughter.

As one of 600 mothers participating in the project, Ms. Matos periodically answers questions about her daughter’s progress, like whether she is eating solid foods.

Megha Agarwal, BS, executive director of the Bridge Project and its funder the Monarch Foundation, said she was thrilled to see the early results from Baby’s First Years. “We are looking for ways in which we can strengthen our future generations,” she said. “It is exciting to see that direct cash and a guaranteed income might be part of the solution.”

A scientific perspective

Growing up in poverty is well-known to increase the likelihood of lower academic achievement and chronic conditions such as asthma and obesity. Relative to higher income levels, poverty is associated with differences in the structure and function of the developing brain. But whether interventions to reduce poverty can influence how newborns develop is less clear.

“There would be plenty of people who would say, ‘Well, it’s not poverty. It’s all the things associated with poverty. It’s the choices you make that are actually leading to differences in outcomes,’” said Kimberly Noble, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at Columbia University, New York, and a coauthor of the PNAS study. Regardless of ideology, she said, the best way to address that question from a scientific perspective is through a randomized controlled trial.

“You can’t, and wouldn’t want to, randomize kids to living in poverty or not, but you can take a group of families who are unfortunately living in poverty and randomize them to receive different levels of economic support,” Dr. Noble said.

$333 per month

Baby’s First Years has done just that. Researchers gave 1,000 low-income mothers with newborns a cash gift of $333 per month or a smaller gift of $20 per month, disbursed on debit cards, starting in 2018. Participants live in four metropolitan areas – New York City, greater New Orleans, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, and Omaha – and were recruited at the time of their child’s birth. Investigators currently have funding to continue the cash support until the children turn 4 years old.

When the infants were about 1 year old, investigators measured their resting brain activity using EEG.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the ability to conduct in-person testing, so the number of children with EEG data was smaller than planned. Still, the researchers analyzed data from 251 kids in the group that received the smaller cash gift and 184 kids in the group that received the larger amount. Patterns of brain activity largely tracked those seen in earlier observational studies: more mid- and high-frequency activity (alpha-, beta-, and gamma-bands) and less low-frequency activity (theta-bands) among children in the households that received more money.

Faster brain activity is associated with better scores on measures of language, cognition, and social-emotional development. Slower activity has been linked to problems with behavior, attention, and learning.

“We predicted that our poverty reduction intervention would mitigate the neurobiological signal of poverty,” Dr. Noble said. “And that’s exactly what we report in this paper.”

The study builds on decades of work showing that poverty can harm child development, said Joan Luby, MD, with Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, who served as a peer reviewer for the PNAS paper.

More follow-up data and information about the babies’ cognitive function and behavior over time are needed, but the study shows a signal that cannot be ignored, Dr. Luby said.

Dr. Luby began exploring the effects of poverty on brain development in earnest while working on a study that was meant to focus on another variable altogether: early childhood depression. The investigators on that 2013 study found that poverty had a “very, very big effect in our sample, and we realized we had to learn more about it,” she said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics likewise has recognized poverty as an important determinant of health. A policy statement that the group published in 2016 and reaffirmed in 2021 outlines ways pediatricians and social programs can address poverty.

Benard Dreyer, MD, director of pediatrics at Bellevue Hospital, New York, was president of the AAP when it published this guidance.

One lingering question has been how much low income worsens educational outcomes, Dr. Dreyer said. Perhaps other issues, such as single motherhood, a lack of parental education, or living in neighborhoods with more crime may be the cause. If so, simply giving more money to parents might not overcome those barriers.

Natural experiments have hinted that money itself can influence child development. For example, families on an American Indian reservation in North Carolina started receiving a share of casino profits after a casino opened there.

The new infusion of funds arrived in the middle of a study in which researchers were examining the development of mental illness in children.

Among children who were no longer poor as a result of the casino payments, symptoms of conduct and oppositional defiant disorders decreased.

Guaranteeing income

How extra money affects families across different levels of income also interests researchers and policymakers.

“One of the policy debates in Washington is to what degree should it be to everyone,” Ajay Chaudry, PhD, a research scholar at New York University who is advising the Bridge Project, said.

Guaranteed income programs may need to be available to most of the population out of political necessity, even if the benefits turn out to be the most pronounced at lower income levels, added Dr. Chaudry, who served in the Obama administration as deputy assistant secretary for human services policy.

If giving moms money affects babies’ brains, Dr. Dreyer pointed to two pathways that could explain the link: more resources and less family stress.

Money helps families buy toys and books, which in turn could support a child’s cognitive development. Meanwhile, low-income mothers and fathers may experience worries about eviction, adequate food, and the loss of heat and electricity, which could detract from their ability to parent.

Of course, many ways to support a child’s development do not require money. Engaging with children in a warm and nurturing way, having conversations with them, and reading with them are all important.

If the pattern in the PNAS study holds, individual experiences and outcomes will still vary, Dr. Noble said. Many children in the group that received the smaller gift had fast-paced brain activity, whereas some babies in the group that received the larger gift showed slower brain activity. Knowing family income would not allow you to accurately predict anything about an individual child’s brain, Dr. Noble said.

“I certainly wouldn’t want the message to be that money is the only thing that matters,” Dr. Noble said. “Money is something that can be easily manipulated by policy, which is why I think this is important.”

For the 18-year-old new mom Ms. Matos, accepting assistance “makes me feel less of myself. But honestly, I feel like mothers shouldn’t be afraid to ask for help or reach out for help or apply to programs like these.”

The sources reported a variety of funders, including federal agencies and foundations and donors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What’s the future of microbiome therapies in C. diff, cancer?

WASHINGTON – Research on standardized microbiome-based therapies designed to prevent the recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is moving “with a lot of momentum,” according to one expert, and modulation of the gut microbiome may even enhance responses to immunotherapy and/or abrogate toxicity, according to another.

Several products for prevention of CDI recurrence are poised for either phase 3 trials or upcoming Food and Drug Administration approval, Sahil Khanna, MBBS, MS, professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., reported at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit.

Jennifer A. Wargo, MD, MMSc, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, described her investigations of microbiome modulation’s role in cancer treatment. “I used to say yes [we can do this] somewhat enthusiastically without data, but now we have data to support this,” she said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility. “The answer now is totally yes.”

New approaches for CDI

“Based on how the field is moving, we might be able to [offer our patients] earlier microbiome restoration” than is currently afforded with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), he said. “Right now the [Food and Drug Administration] and our clinical guidelines say we should do FMT after three or more episodes [of CDI] – that’s heartbreaking for patients.”

Several of the microbiome-based therapies under investigation – including two poised for phase 3 trials – have shown efficacy after a second episode of CDI, and one of these two has also had positive results after one episode of CDI in patients 65 at older, a group at particularly high risk of recurrence, said Dr. Khanna.

The value of standardized, mostly pill-form microbiome therapies has been heightened during the pandemic. “We’ve been doing conventional FMT for recurrent C. difficile for over a decade now, and it’s probably the most effective treatment we have,” said Colleen R. Kelly, MD, associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and moderator of the session on microbiota-based therapies.

Prepandemic “it got really hard, with issues of identifying donors, and quality control and safety ... And then when COVID hit the stool banks shut down,” she said in an interview after the meeting. With stool testing for SARS-CoV-2 now in place, some stool is again available, “but it made me realize how fragile our current system is,” Dr. Kelly said. “The fact that companies are putting these products through the FDA pipeline and investigating them in rigorous, scientific randomized controlled trials is really good for the field.”

The products vary in composition; some are live multi-strain biotherapeutics derived from donor stool, for instance, while others are defined live bacterial consortia not from stool. Most are oral formulations, given one or multiple times, that do not require any bowel preparation.

One of the products most advanced in the pipeline, RBX2660 (Rebiotix, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) is stool derived and rectally administered. In phase 3 research, 70.5% of patients who received one active enema after having had two or more CDI recurrences and standard-of-care antibiotic treatment had no additional recurrence at 8 weeks compared to 58.1% in the placebo group, Dr. Khanna said.

The other product with positive phase 3 results, SER-109 (Seres Therapeutics), is a donor stool-derived oral formulation of purified Firmicutes spores that is administered after bowel prep. In results published earlier this year, the percentage of patients with recurrence of CDI up to 8 weeks after standard antibiotic treatment was 12% in the SER-109 group and 40% in the placebo group.

Patients in this trial were required to have had three episodes of CDI, and interestingly, Dr. Khanna said, the diagnosis of CDI was made only by toxin enzyme immunoassay (EIA). Earlier phase 2 research, which allowed either toxin EIA or polymerase chain reaction testing for the diagnosis of CDI (as other trials have done), produced negative results, leading investigators to surmise that some of the included patients had been colonized with C. difficile rather than being actively infected, Dr. Khanna said.

Researchers of these trials are documenting not only resolution of CDI but what they believe are positive shifts in the gut microbiota after microbiome-based therapy, he said. For instance, a phase 1 trial he led of the product RBX7455 (Rebiotix, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) – an oral capsule of lyophilized stool-based bacteria that can be kept for several days at room temperature – showed increases in Bacteroidia and Clostridia.

And other trials’ analyses of microbiome engraftment have demonstrated that “you can restore [species] even when these bacteria aren’t [included in the therapy],” he noted. “As the milieu of the gut improves, species that were not detected start coming back up.”

Asked about rates of efficacy in the trials’ placebo arms, Dr. Khanna said that “we’ve become smarter with our antibiotic regimens ... the placebo response rate is the response to newer guideline-based therapies.”

In addition to CDI, microbiome-based therapies are being studied, mostly in phase 1 research, for indications such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, autism spectrum disorder, hepatitis B, and hepatic encephalopathy, Dr. Khanna noted.

Dr. Kelly, whose own research has focused on FMT for CDI, said she anticipates an expansion of research into other indications once products to prevent CDI recurrence are on the market. “There have been a couple of promising ulcerative colitis trials that haven’t gone anywhere clinically yet,” she said in the interview. “But will we now identify patients with UC who may be more sensitive to microbial manipulation, for whom we can use these microbial therapies along with a biologic?”

Some of her patients with IBD and CDI who are treated with FMT have not only had their CDI eradicated but have subsequently seen improvements in their IBD, she noted.

The role of traditional FMT and of stool banks will likely change in the future with new standardized oral microbiome-based therapies that can be approved and regulated by the FDA, she said. However, “we think the stool banks will still have some value,” she said, certainly for clinical research and probably for some treatment purposes as well. Regarding new therapies, “I just really hope they’re affordable,” she said.

Gut microbiome manipulation for cancer

Dr. Wargo’s research at MD Anderson has focused on metastatic breast cancer and immunotherapeutic checkpoint blockade. By sequencing microbiota samples and performing immune profiling in hundreds of patients, her team found that responders to PD-1 blockage have a greater diversity of gut bacteria and that “favorable signatures in the gut microbiome” are associated with enhanced immune responses in the tumor microenvironment.

Studies published last year in Science from investigators in Israel (2021 Feb 5;371[6529]:602-9) and Pittsburgh (2021 Feb 5;371[6529]:595-602), demonstrated that FMT promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. In one study, FMT provided clinical benefit in 6 of 15 patients whose cancer had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy, “which is pretty remarkable,” Dr. Wargo said.

Both research groups, she noted, saw favorable changes in the gut microbiome and immune cell infiltrates both at the level of the colon and the tumor.

Current research on FMT and other microbiome modulation strategies for cancer is guided in part by knowledge that tumors have microbial signatures – these signatures are now being identified across all tumor types – and by findings of “cross talk” between the gut and tumor microbiomes, she explained.

“Researchers are working hard to identify optimal consortia to enhance immune responses in the cancer setting, with promising work in preclinical models,” she said, and clinical trials are in progress. The role of diet in modulating the microbiome and enhancing anti-tumor immunity, with a focus on high dietary fiber intake, is also being investigated, she said.

Dr. Wargo reported that she serves on the advisory boards and is a paid speaker of numerous pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, and is the coinventor of a patent submitted by the Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center on modulating the microbiome to enhance response to checkpoint blockade, and another related patent. Dr. Khanna reported that he is involved in research with Ferring/Rebiotix, Finch, Seres, Pfizer and Vendata, and does consulting for Immuron and several other companies. Dr. Kelly said she serves as an unpaid adviser for OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank, and that her site has enrolled patients in two of the trials testing products for CDI.

WASHINGTON – Research on standardized microbiome-based therapies designed to prevent the recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is moving “with a lot of momentum,” according to one expert, and modulation of the gut microbiome may even enhance responses to immunotherapy and/or abrogate toxicity, according to another.

Several products for prevention of CDI recurrence are poised for either phase 3 trials or upcoming Food and Drug Administration approval, Sahil Khanna, MBBS, MS, professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., reported at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit.

Jennifer A. Wargo, MD, MMSc, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, described her investigations of microbiome modulation’s role in cancer treatment. “I used to say yes [we can do this] somewhat enthusiastically without data, but now we have data to support this,” she said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility. “The answer now is totally yes.”

New approaches for CDI

“Based on how the field is moving, we might be able to [offer our patients] earlier microbiome restoration” than is currently afforded with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), he said. “Right now the [Food and Drug Administration] and our clinical guidelines say we should do FMT after three or more episodes [of CDI] – that’s heartbreaking for patients.”

Several of the microbiome-based therapies under investigation – including two poised for phase 3 trials – have shown efficacy after a second episode of CDI, and one of these two has also had positive results after one episode of CDI in patients 65 at older, a group at particularly high risk of recurrence, said Dr. Khanna.

The value of standardized, mostly pill-form microbiome therapies has been heightened during the pandemic. “We’ve been doing conventional FMT for recurrent C. difficile for over a decade now, and it’s probably the most effective treatment we have,” said Colleen R. Kelly, MD, associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and moderator of the session on microbiota-based therapies.

Prepandemic “it got really hard, with issues of identifying donors, and quality control and safety ... And then when COVID hit the stool banks shut down,” she said in an interview after the meeting. With stool testing for SARS-CoV-2 now in place, some stool is again available, “but it made me realize how fragile our current system is,” Dr. Kelly said. “The fact that companies are putting these products through the FDA pipeline and investigating them in rigorous, scientific randomized controlled trials is really good for the field.”

The products vary in composition; some are live multi-strain biotherapeutics derived from donor stool, for instance, while others are defined live bacterial consortia not from stool. Most are oral formulations, given one or multiple times, that do not require any bowel preparation.

One of the products most advanced in the pipeline, RBX2660 (Rebiotix, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) is stool derived and rectally administered. In phase 3 research, 70.5% of patients who received one active enema after having had two or more CDI recurrences and standard-of-care antibiotic treatment had no additional recurrence at 8 weeks compared to 58.1% in the placebo group, Dr. Khanna said.

The other product with positive phase 3 results, SER-109 (Seres Therapeutics), is a donor stool-derived oral formulation of purified Firmicutes spores that is administered after bowel prep. In results published earlier this year, the percentage of patients with recurrence of CDI up to 8 weeks after standard antibiotic treatment was 12% in the SER-109 group and 40% in the placebo group.

Patients in this trial were required to have had three episodes of CDI, and interestingly, Dr. Khanna said, the diagnosis of CDI was made only by toxin enzyme immunoassay (EIA). Earlier phase 2 research, which allowed either toxin EIA or polymerase chain reaction testing for the diagnosis of CDI (as other trials have done), produced negative results, leading investigators to surmise that some of the included patients had been colonized with C. difficile rather than being actively infected, Dr. Khanna said.

Researchers of these trials are documenting not only resolution of CDI but what they believe are positive shifts in the gut microbiota after microbiome-based therapy, he said. For instance, a phase 1 trial he led of the product RBX7455 (Rebiotix, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) – an oral capsule of lyophilized stool-based bacteria that can be kept for several days at room temperature – showed increases in Bacteroidia and Clostridia.

And other trials’ analyses of microbiome engraftment have demonstrated that “you can restore [species] even when these bacteria aren’t [included in the therapy],” he noted. “As the milieu of the gut improves, species that were not detected start coming back up.”

Asked about rates of efficacy in the trials’ placebo arms, Dr. Khanna said that “we’ve become smarter with our antibiotic regimens ... the placebo response rate is the response to newer guideline-based therapies.”

In addition to CDI, microbiome-based therapies are being studied, mostly in phase 1 research, for indications such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, autism spectrum disorder, hepatitis B, and hepatic encephalopathy, Dr. Khanna noted.

Dr. Kelly, whose own research has focused on FMT for CDI, said she anticipates an expansion of research into other indications once products to prevent CDI recurrence are on the market. “There have been a couple of promising ulcerative colitis trials that haven’t gone anywhere clinically yet,” she said in the interview. “But will we now identify patients with UC who may be more sensitive to microbial manipulation, for whom we can use these microbial therapies along with a biologic?”

Some of her patients with IBD and CDI who are treated with FMT have not only had their CDI eradicated but have subsequently seen improvements in their IBD, she noted.

The role of traditional FMT and of stool banks will likely change in the future with new standardized oral microbiome-based therapies that can be approved and regulated by the FDA, she said. However, “we think the stool banks will still have some value,” she said, certainly for clinical research and probably for some treatment purposes as well. Regarding new therapies, “I just really hope they’re affordable,” she said.

Gut microbiome manipulation for cancer

Dr. Wargo’s research at MD Anderson has focused on metastatic breast cancer and immunotherapeutic checkpoint blockade. By sequencing microbiota samples and performing immune profiling in hundreds of patients, her team found that responders to PD-1 blockage have a greater diversity of gut bacteria and that “favorable signatures in the gut microbiome” are associated with enhanced immune responses in the tumor microenvironment.

Studies published last year in Science from investigators in Israel (2021 Feb 5;371[6529]:602-9) and Pittsburgh (2021 Feb 5;371[6529]:595-602), demonstrated that FMT promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. In one study, FMT provided clinical benefit in 6 of 15 patients whose cancer had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy, “which is pretty remarkable,” Dr. Wargo said.

Both research groups, she noted, saw favorable changes in the gut microbiome and immune cell infiltrates both at the level of the colon and the tumor.

Current research on FMT and other microbiome modulation strategies for cancer is guided in part by knowledge that tumors have microbial signatures – these signatures are now being identified across all tumor types – and by findings of “cross talk” between the gut and tumor microbiomes, she explained.

“Researchers are working hard to identify optimal consortia to enhance immune responses in the cancer setting, with promising work in preclinical models,” she said, and clinical trials are in progress. The role of diet in modulating the microbiome and enhancing anti-tumor immunity, with a focus on high dietary fiber intake, is also being investigated, she said.

Dr. Wargo reported that she serves on the advisory boards and is a paid speaker of numerous pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, and is the coinventor of a patent submitted by the Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center on modulating the microbiome to enhance response to checkpoint blockade, and another related patent. Dr. Khanna reported that he is involved in research with Ferring/Rebiotix, Finch, Seres, Pfizer and Vendata, and does consulting for Immuron and several other companies. Dr. Kelly said she serves as an unpaid adviser for OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank, and that her site has enrolled patients in two of the trials testing products for CDI.

WASHINGTON – Research on standardized microbiome-based therapies designed to prevent the recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is moving “with a lot of momentum,” according to one expert, and modulation of the gut microbiome may even enhance responses to immunotherapy and/or abrogate toxicity, according to another.

Several products for prevention of CDI recurrence are poised for either phase 3 trials or upcoming Food and Drug Administration approval, Sahil Khanna, MBBS, MS, professor of medicine, gastroenterology, and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., reported at the annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit.

Jennifer A. Wargo, MD, MMSc, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, described her investigations of microbiome modulation’s role in cancer treatment. “I used to say yes [we can do this] somewhat enthusiastically without data, but now we have data to support this,” she said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility. “The answer now is totally yes.”

New approaches for CDI

“Based on how the field is moving, we might be able to [offer our patients] earlier microbiome restoration” than is currently afforded with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), he said. “Right now the [Food and Drug Administration] and our clinical guidelines say we should do FMT after three or more episodes [of CDI] – that’s heartbreaking for patients.”

Several of the microbiome-based therapies under investigation – including two poised for phase 3 trials – have shown efficacy after a second episode of CDI, and one of these two has also had positive results after one episode of CDI in patients 65 at older, a group at particularly high risk of recurrence, said Dr. Khanna.

The value of standardized, mostly pill-form microbiome therapies has been heightened during the pandemic. “We’ve been doing conventional FMT for recurrent C. difficile for over a decade now, and it’s probably the most effective treatment we have,” said Colleen R. Kelly, MD, associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and moderator of the session on microbiota-based therapies.

Prepandemic “it got really hard, with issues of identifying donors, and quality control and safety ... And then when COVID hit the stool banks shut down,” she said in an interview after the meeting. With stool testing for SARS-CoV-2 now in place, some stool is again available, “but it made me realize how fragile our current system is,” Dr. Kelly said. “The fact that companies are putting these products through the FDA pipeline and investigating them in rigorous, scientific randomized controlled trials is really good for the field.”

The products vary in composition; some are live multi-strain biotherapeutics derived from donor stool, for instance, while others are defined live bacterial consortia not from stool. Most are oral formulations, given one or multiple times, that do not require any bowel preparation.

One of the products most advanced in the pipeline, RBX2660 (Rebiotix, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) is stool derived and rectally administered. In phase 3 research, 70.5% of patients who received one active enema after having had two or more CDI recurrences and standard-of-care antibiotic treatment had no additional recurrence at 8 weeks compared to 58.1% in the placebo group, Dr. Khanna said.

The other product with positive phase 3 results, SER-109 (Seres Therapeutics), is a donor stool-derived oral formulation of purified Firmicutes spores that is administered after bowel prep. In results published earlier this year, the percentage of patients with recurrence of CDI up to 8 weeks after standard antibiotic treatment was 12% in the SER-109 group and 40% in the placebo group.

Patients in this trial were required to have had three episodes of CDI, and interestingly, Dr. Khanna said, the diagnosis of CDI was made only by toxin enzyme immunoassay (EIA). Earlier phase 2 research, which allowed either toxin EIA or polymerase chain reaction testing for the diagnosis of CDI (as other trials have done), produced negative results, leading investigators to surmise that some of the included patients had been colonized with C. difficile rather than being actively infected, Dr. Khanna said.

Researchers of these trials are documenting not only resolution of CDI but what they believe are positive shifts in the gut microbiota after microbiome-based therapy, he said. For instance, a phase 1 trial he led of the product RBX7455 (Rebiotix, Ferring Pharmaceuticals) – an oral capsule of lyophilized stool-based bacteria that can be kept for several days at room temperature – showed increases in Bacteroidia and Clostridia.

And other trials’ analyses of microbiome engraftment have demonstrated that “you can restore [species] even when these bacteria aren’t [included in the therapy],” he noted. “As the milieu of the gut improves, species that were not detected start coming back up.”

Asked about rates of efficacy in the trials’ placebo arms, Dr. Khanna said that “we’ve become smarter with our antibiotic regimens ... the placebo response rate is the response to newer guideline-based therapies.”

In addition to CDI, microbiome-based therapies are being studied, mostly in phase 1 research, for indications such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, autism spectrum disorder, hepatitis B, and hepatic encephalopathy, Dr. Khanna noted.

Dr. Kelly, whose own research has focused on FMT for CDI, said she anticipates an expansion of research into other indications once products to prevent CDI recurrence are on the market. “There have been a couple of promising ulcerative colitis trials that haven’t gone anywhere clinically yet,” she said in the interview. “But will we now identify patients with UC who may be more sensitive to microbial manipulation, for whom we can use these microbial therapies along with a biologic?”

Some of her patients with IBD and CDI who are treated with FMT have not only had their CDI eradicated but have subsequently seen improvements in their IBD, she noted.

The role of traditional FMT and of stool banks will likely change in the future with new standardized oral microbiome-based therapies that can be approved and regulated by the FDA, she said. However, “we think the stool banks will still have some value,” she said, certainly for clinical research and probably for some treatment purposes as well. Regarding new therapies, “I just really hope they’re affordable,” she said.

Gut microbiome manipulation for cancer

Dr. Wargo’s research at MD Anderson has focused on metastatic breast cancer and immunotherapeutic checkpoint blockade. By sequencing microbiota samples and performing immune profiling in hundreds of patients, her team found that responders to PD-1 blockage have a greater diversity of gut bacteria and that “favorable signatures in the gut microbiome” are associated with enhanced immune responses in the tumor microenvironment.

Studies published last year in Science from investigators in Israel (2021 Feb 5;371[6529]:602-9) and Pittsburgh (2021 Feb 5;371[6529]:595-602), demonstrated that FMT promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. In one study, FMT provided clinical benefit in 6 of 15 patients whose cancer had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy, “which is pretty remarkable,” Dr. Wargo said.

Both research groups, she noted, saw favorable changes in the gut microbiome and immune cell infiltrates both at the level of the colon and the tumor.

Current research on FMT and other microbiome modulation strategies for cancer is guided in part by knowledge that tumors have microbial signatures – these signatures are now being identified across all tumor types – and by findings of “cross talk” between the gut and tumor microbiomes, she explained.

“Researchers are working hard to identify optimal consortia to enhance immune responses in the cancer setting, with promising work in preclinical models,” she said, and clinical trials are in progress. The role of diet in modulating the microbiome and enhancing anti-tumor immunity, with a focus on high dietary fiber intake, is also being investigated, she said.

Dr. Wargo reported that she serves on the advisory boards and is a paid speaker of numerous pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, and is the coinventor of a patent submitted by the Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center on modulating the microbiome to enhance response to checkpoint blockade, and another related patent. Dr. Khanna reported that he is involved in research with Ferring/Rebiotix, Finch, Seres, Pfizer and Vendata, and does consulting for Immuron and several other companies. Dr. Kelly said she serves as an unpaid adviser for OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank, and that her site has enrolled patients in two of the trials testing products for CDI.

REPORTING FROM GMFH 2022

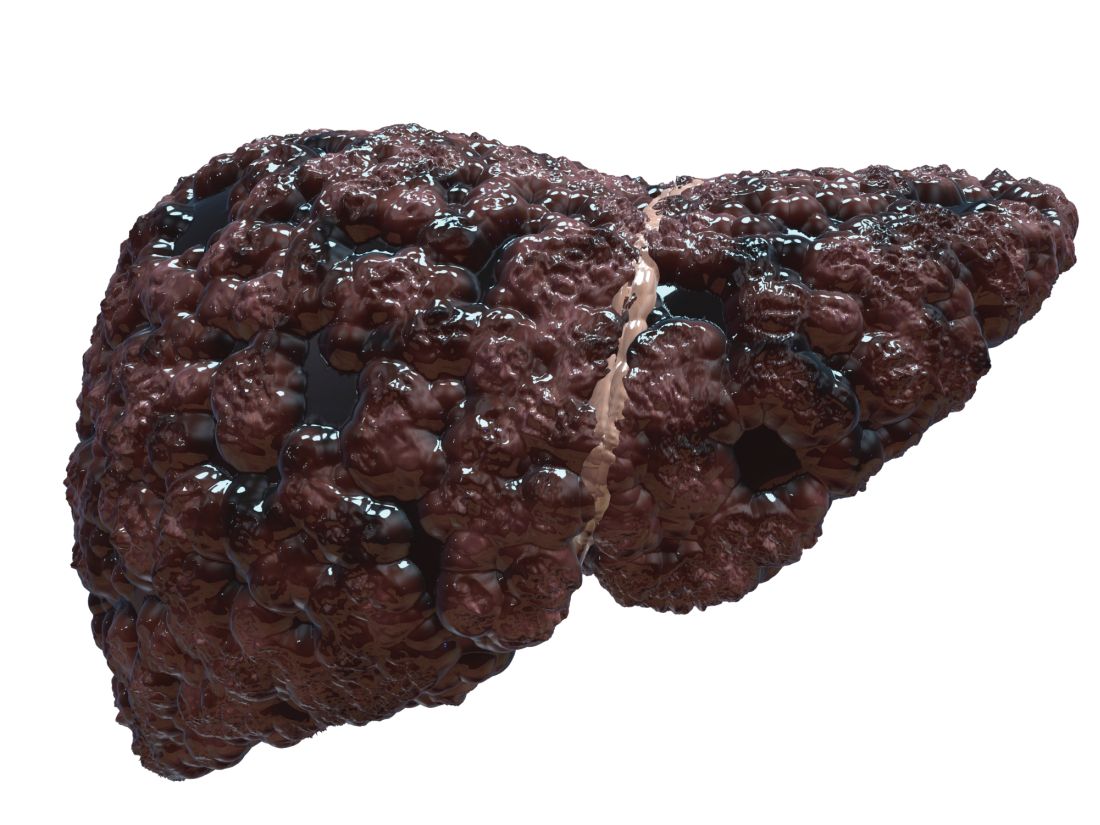

Shunt diameter predicts liver function after obliteration procedure

Patients with cirrhosis and larger spontaneous shunt diameters showed a significantly greater increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) following balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration compared to patients with smaller shunt diameters, based on data from 34 adults.

Portal hypertension remains a key source of complications that greatly impact quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, wrote Akihisa Tatsumi, MD, of the University of Yamanashi, Japan, and colleagues. These patients sometimes develop spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) to lower portal pressure, but these natural shunts are an incomplete solution – one that may contribute to liver dysfunction by reducing hepatic portal blood flow. However, the association of SPSS with liver functional reserve remains unclear, the researchers said.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is gaining popularity as a treatment for SPSS in patients with cirrhosis but determining the patients who will benefit from this procedure remains a challenge, the researchers wrote. “Apart from BRTO, some recent studies have reported the impact of the SPSS diameter on the future pathological state of the liver,” which prompted the question of whether SPSS diameter plays a role in predicting portal hypertension–related liver function at baseline and after BRTO, the researchers explained.

In their study, published in JGH Open, the researchers identified 34 cirrhotic patients with SPSS who underwent BRTO at a single center in Japan between 2006 and 2018; all of the patients were available for follow-up at least 6 months after the procedure.

The reasons for BRTO were intractable gastric varices in 18 patients and refractory hepatic encephalopathy with shunt in 16 patients; the mean observation period was 1,182 days (3.24 years). The median age of the patients was 66.5 years, and 53% were male. A majority (76%) of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis with Child-Pugh (CP) scores of B or C, and the maximum diameter of SPSS increased significantly with increased in CP scores (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Overall, at 6 months after BRTO, patients showed significant improvements in liver function from baseline. However, the improvement rate was lower in patients whose shunt diameter was 10 mm or less, and improvement was greatest when the shunt diameter was between 10 mm and 20 mm. “Because the CP score is a significant cofounding factor of the SPSS diameter, we next evaluated the changes in liver function classified by CP scores,” the researchers wrote. In this analysis, the post-BRTO changes in liver function in patients with CP scores of A or B still showed an association between improvement in liver function and larger shunt diameter, but this relationship did not extend to patients with CP scores of C, the researchers said.

A larger shunt diameter also was significantly associated with a greater increase in HVPG after balloon occlusion (P = .005).

“Considering that patients with large SPSS diameters might gain higher portal flow following elevation of HVPG after BRTO, it is natural that the larger the SPSS diameter, the greater the improvements in liver function,” the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. “However, such a clear correlation was evident only when the baseline CP scores were within A or B, and not in C, indicating that the improvement of liver function might not parallel HVPG increase in some CP C patients,” they noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the retrospective design from a single center and its small sample size, the researchers noted. Other limitations included selecting and measuring only the largest SPSS of each patient and lack of data on the impact of SPSS diameter on overall survival, they said.

However, the results suggest that SPSS diameter may serve not only as an indicator of portal hypertension involvement at baseline, but also as a useful clinical predictor of liver function after BRTO, they concluded.

Study supports potential benefits of BRTO

“While the association between SPSS and complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy have been known, data are lacking in regard to characteristics of SPSS that are most dysfunctional, and whether certain patients may benefit from BRTO to occlude these shunts,” Khashayar Farsad, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview.

“The results are in many ways expected based on anticipated impact of larger versus smaller SPSS in overall liver function,” Dr. Farsad noted. “The study, however, does show a nice correlation between several factors involved in liver function and their changes depending on shunt diameter, correlated with changes in the relative venous pressure gradient across the liver,” he said. “Furthermore, the finding that changes were most evident in those with relatively preserved liver function [Child-Turcotte-Pugh grades A and B] suggests less of a relationship between SPSS and liver function in those with more decompensated liver disease,” he added.

“The impact of the study is significantly limited by its retrospective design, small numbers with potential patient heterogeneity, and lack of a control cohort,” said Dr. Farsad. However, “The major take-home message for clinicians is a potential signal that the size of the SPSS at baseline may predict the impact of the SPSS on liver function, and therefore, the potential benefit of a procedure such as BRTO to positively influence this,” he said. “Additional research with larger cohorts and a prospective study design would be warranted, however, before this information would be meaningful in daily clinical decision making,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the Research Program on Hepatitis of the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Farsad disclosed research support from W.L. Gore & Associates, Guerbet LLC, Boston Scientific, and Exelixis; serving as a consultant for NeuWave Medical, Cook Medical, Guerbet LLC, and Eisai, and holding equity in Auxetics Inc.

Patients with cirrhosis and larger spontaneous shunt diameters showed a significantly greater increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) following balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration compared to patients with smaller shunt diameters, based on data from 34 adults.

Portal hypertension remains a key source of complications that greatly impact quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, wrote Akihisa Tatsumi, MD, of the University of Yamanashi, Japan, and colleagues. These patients sometimes develop spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) to lower portal pressure, but these natural shunts are an incomplete solution – one that may contribute to liver dysfunction by reducing hepatic portal blood flow. However, the association of SPSS with liver functional reserve remains unclear, the researchers said.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is gaining popularity as a treatment for SPSS in patients with cirrhosis but determining the patients who will benefit from this procedure remains a challenge, the researchers wrote. “Apart from BRTO, some recent studies have reported the impact of the SPSS diameter on the future pathological state of the liver,” which prompted the question of whether SPSS diameter plays a role in predicting portal hypertension–related liver function at baseline and after BRTO, the researchers explained.

In their study, published in JGH Open, the researchers identified 34 cirrhotic patients with SPSS who underwent BRTO at a single center in Japan between 2006 and 2018; all of the patients were available for follow-up at least 6 months after the procedure.

The reasons for BRTO were intractable gastric varices in 18 patients and refractory hepatic encephalopathy with shunt in 16 patients; the mean observation period was 1,182 days (3.24 years). The median age of the patients was 66.5 years, and 53% were male. A majority (76%) of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis with Child-Pugh (CP) scores of B or C, and the maximum diameter of SPSS increased significantly with increased in CP scores (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Overall, at 6 months after BRTO, patients showed significant improvements in liver function from baseline. However, the improvement rate was lower in patients whose shunt diameter was 10 mm or less, and improvement was greatest when the shunt diameter was between 10 mm and 20 mm. “Because the CP score is a significant cofounding factor of the SPSS diameter, we next evaluated the changes in liver function classified by CP scores,” the researchers wrote. In this analysis, the post-BRTO changes in liver function in patients with CP scores of A or B still showed an association between improvement in liver function and larger shunt diameter, but this relationship did not extend to patients with CP scores of C, the researchers said.

A larger shunt diameter also was significantly associated with a greater increase in HVPG after balloon occlusion (P = .005).

“Considering that patients with large SPSS diameters might gain higher portal flow following elevation of HVPG after BRTO, it is natural that the larger the SPSS diameter, the greater the improvements in liver function,” the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. “However, such a clear correlation was evident only when the baseline CP scores were within A or B, and not in C, indicating that the improvement of liver function might not parallel HVPG increase in some CP C patients,” they noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the retrospective design from a single center and its small sample size, the researchers noted. Other limitations included selecting and measuring only the largest SPSS of each patient and lack of data on the impact of SPSS diameter on overall survival, they said.

However, the results suggest that SPSS diameter may serve not only as an indicator of portal hypertension involvement at baseline, but also as a useful clinical predictor of liver function after BRTO, they concluded.

Study supports potential benefits of BRTO

“While the association between SPSS and complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy have been known, data are lacking in regard to characteristics of SPSS that are most dysfunctional, and whether certain patients may benefit from BRTO to occlude these shunts,” Khashayar Farsad, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview.

“The results are in many ways expected based on anticipated impact of larger versus smaller SPSS in overall liver function,” Dr. Farsad noted. “The study, however, does show a nice correlation between several factors involved in liver function and their changes depending on shunt diameter, correlated with changes in the relative venous pressure gradient across the liver,” he said. “Furthermore, the finding that changes were most evident in those with relatively preserved liver function [Child-Turcotte-Pugh grades A and B] suggests less of a relationship between SPSS and liver function in those with more decompensated liver disease,” he added.

“The impact of the study is significantly limited by its retrospective design, small numbers with potential patient heterogeneity, and lack of a control cohort,” said Dr. Farsad. However, “The major take-home message for clinicians is a potential signal that the size of the SPSS at baseline may predict the impact of the SPSS on liver function, and therefore, the potential benefit of a procedure such as BRTO to positively influence this,” he said. “Additional research with larger cohorts and a prospective study design would be warranted, however, before this information would be meaningful in daily clinical decision making,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the Research Program on Hepatitis of the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Farsad disclosed research support from W.L. Gore & Associates, Guerbet LLC, Boston Scientific, and Exelixis; serving as a consultant for NeuWave Medical, Cook Medical, Guerbet LLC, and Eisai, and holding equity in Auxetics Inc.

Patients with cirrhosis and larger spontaneous shunt diameters showed a significantly greater increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) following balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration compared to patients with smaller shunt diameters, based on data from 34 adults.

Portal hypertension remains a key source of complications that greatly impact quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, wrote Akihisa Tatsumi, MD, of the University of Yamanashi, Japan, and colleagues. These patients sometimes develop spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSS) to lower portal pressure, but these natural shunts are an incomplete solution – one that may contribute to liver dysfunction by reducing hepatic portal blood flow. However, the association of SPSS with liver functional reserve remains unclear, the researchers said.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is gaining popularity as a treatment for SPSS in patients with cirrhosis but determining the patients who will benefit from this procedure remains a challenge, the researchers wrote. “Apart from BRTO, some recent studies have reported the impact of the SPSS diameter on the future pathological state of the liver,” which prompted the question of whether SPSS diameter plays a role in predicting portal hypertension–related liver function at baseline and after BRTO, the researchers explained.

In their study, published in JGH Open, the researchers identified 34 cirrhotic patients with SPSS who underwent BRTO at a single center in Japan between 2006 and 2018; all of the patients were available for follow-up at least 6 months after the procedure.

The reasons for BRTO were intractable gastric varices in 18 patients and refractory hepatic encephalopathy with shunt in 16 patients; the mean observation period was 1,182 days (3.24 years). The median age of the patients was 66.5 years, and 53% were male. A majority (76%) of the patients had decompensated cirrhosis with Child-Pugh (CP) scores of B or C, and the maximum diameter of SPSS increased significantly with increased in CP scores (P < .001), the researchers noted.

Overall, at 6 months after BRTO, patients showed significant improvements in liver function from baseline. However, the improvement rate was lower in patients whose shunt diameter was 10 mm or less, and improvement was greatest when the shunt diameter was between 10 mm and 20 mm. “Because the CP score is a significant cofounding factor of the SPSS diameter, we next evaluated the changes in liver function classified by CP scores,” the researchers wrote. In this analysis, the post-BRTO changes in liver function in patients with CP scores of A or B still showed an association between improvement in liver function and larger shunt diameter, but this relationship did not extend to patients with CP scores of C, the researchers said.

A larger shunt diameter also was significantly associated with a greater increase in HVPG after balloon occlusion (P = .005).

“Considering that patients with large SPSS diameters might gain higher portal flow following elevation of HVPG after BRTO, it is natural that the larger the SPSS diameter, the greater the improvements in liver function,” the researchers wrote in their discussion of the findings. “However, such a clear correlation was evident only when the baseline CP scores were within A or B, and not in C, indicating that the improvement of liver function might not parallel HVPG increase in some CP C patients,” they noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the retrospective design from a single center and its small sample size, the researchers noted. Other limitations included selecting and measuring only the largest SPSS of each patient and lack of data on the impact of SPSS diameter on overall survival, they said.

However, the results suggest that SPSS diameter may serve not only as an indicator of portal hypertension involvement at baseline, but also as a useful clinical predictor of liver function after BRTO, they concluded.

Study supports potential benefits of BRTO

“While the association between SPSS and complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy have been known, data are lacking in regard to characteristics of SPSS that are most dysfunctional, and whether certain patients may benefit from BRTO to occlude these shunts,” Khashayar Farsad, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview.

“The results are in many ways expected based on anticipated impact of larger versus smaller SPSS in overall liver function,” Dr. Farsad noted. “The study, however, does show a nice correlation between several factors involved in liver function and their changes depending on shunt diameter, correlated with changes in the relative venous pressure gradient across the liver,” he said. “Furthermore, the finding that changes were most evident in those with relatively preserved liver function [Child-Turcotte-Pugh grades A and B] suggests less of a relationship between SPSS and liver function in those with more decompensated liver disease,” he added.

“The impact of the study is significantly limited by its retrospective design, small numbers with potential patient heterogeneity, and lack of a control cohort,” said Dr. Farsad. However, “The major take-home message for clinicians is a potential signal that the size of the SPSS at baseline may predict the impact of the SPSS on liver function, and therefore, the potential benefit of a procedure such as BRTO to positively influence this,” he said. “Additional research with larger cohorts and a prospective study design would be warranted, however, before this information would be meaningful in daily clinical decision making,” he emphasized.

The study was supported by the Research Program on Hepatitis of the Japanese Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Farsad disclosed research support from W.L. Gore & Associates, Guerbet LLC, Boston Scientific, and Exelixis; serving as a consultant for NeuWave Medical, Cook Medical, Guerbet LLC, and Eisai, and holding equity in Auxetics Inc.

FROM JGH OPEN

Kawasaki disease guideline highlights rheumatology angles

All Kawasaki disease (KD) patients should be treated first with intravenous immunoglobulin, according to an updated guideline issued jointly by the American College of Rheumatology and the Vasculitis Foundation.

KD has low mortality when treated appropriately, guideline first author Mark Gorelik, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at Columbia University, New York, and colleagues wrote.

The update is important at this time because new evidence continues to emerge in the clinical management of KD, Dr. Gorelik said in an interview.

“In addition, this guideline approaches Kawasaki disease from a perspective of acting as an adjunct to the already existing and excellent American Heart Association guidelines by adding information in areas that rheumatologists may play a role,” Dr. Gorelik said. “This is specifically regarding patients who may require additional therapy beyond standard IVIg, such as patients who may be at higher risk of morbidity from disease and patients who have refractory disease,” he explained.

The guideline, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, includes 11 recommendations, 1 good practice statement, and 1 ungraded position statement. The good practice statement emphasizes that all patients with KD should be initially treated with IVIg.

The position statement advises that either nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressive therapy or glucocorticoids may be used for patients with acute KD whose fever persists despite repeated IVIg treatment. No clinical evidence currently supports the superiority of either nonglucocorticoid immunosuppressive therapy or glucocorticoids; therefore, the authors support the use of either based on what is appropriate in any given clinical situation. Although optimal dosage and duration of glucocorticoids have yet to be determined in a U.S. population, the authors described a typical glucocorticoid dosage as starting prednisone at 2 mg/kg per day, with a maximum of 60 mg/day, and dose tapering over 15 days.

The 11 recommendations consist of 7 strong and 4 conditional recommendations. The strong recommendations focus on prompt treatment of incomplete KD, treatment with aspirin, and obtaining an echocardiogram in patients with unexplained macrophage activation syndrome or shock. The conditional recommendations support using established therapy promptly at disease onset, then identifying cases in which additional therapy is needed.

Dr. Gorelik highlighted four clinical takeaways from the guideline. First, “patients with higher risk for complications do exist in Kawasaki disease, and that these patients can be treated more aggressively,” he said. “Specifically, patients with aneurysms seen at first ultrasound, and patients who are under 6 months, are more likely to have progressive and/or refractory disease; these patients can be treated with an adjunctive short course of corticosteroids.”

Second, “the use of high-dose aspirin for patients with Kawasaki disease does not have strong basis in evidence. While aspirin itself of some dose is necessary for patients with Kawasaki disease, use of either high- or low-dose aspirin has the same outcome for patients, and a physician may choose either of these in practice,” he said.

Third, “we continue to recommend that refractory patients with Kawasaki disease be treated with a second dose of IVIg; however, there are many scenarios in which a physician may choose either corticosteroids [either a single high dose of >10 mg/kg, or a short moderate-dose course of 2 mg/kg per day for 5-7 days] or a biologic agent such as infliximab. ... These are valid choices for therapy in patients with refractory Kawasaki disease,” he emphasized.

Fourth, “physicians should discard the idea of treating before [and conversely, not treating after] 10 days of fever,” Dr. Gorelik said. “Patients with Kawasaki disease should be treated as soon as the diagnosis is made, regardless of whether this patient is on day 5, day 12, or day 20 of symptoms.”

Update incorporates emerging evidence