User login

Smoking cessation could prevent a large proportion of MS cases

Key clinical point: At least 13% of cases of multiple sclerosis (MS) can be prevented if tobacco smoking is avoided, indicating the need for integrated programs aimed not only at smoking cessation but also at smoking prevention.

Major finding: The overall attributable fraction (AF) of MS because of smoking was 13.1% (95% CI 10.7%-15.4%), with AF being 0.6% (95% CI 0%-2%) in ex-smokers, indicating the beneficial effects of smoking cessation. Ever-smokers were at a 41% (95% CI 1.33%-1.50%) increased risk for MS than never smokers.

Study details: This was a population-based matched case-control study including 9,419 patients with MS and 9,419 matched control individuals.

Disclosures: No external funding was received for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Manouchehrinia A et al. Smoking attributable risk in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:840158 (Mar 3). Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.840158

Key clinical point: At least 13% of cases of multiple sclerosis (MS) can be prevented if tobacco smoking is avoided, indicating the need for integrated programs aimed not only at smoking cessation but also at smoking prevention.

Major finding: The overall attributable fraction (AF) of MS because of smoking was 13.1% (95% CI 10.7%-15.4%), with AF being 0.6% (95% CI 0%-2%) in ex-smokers, indicating the beneficial effects of smoking cessation. Ever-smokers were at a 41% (95% CI 1.33%-1.50%) increased risk for MS than never smokers.

Study details: This was a population-based matched case-control study including 9,419 patients with MS and 9,419 matched control individuals.

Disclosures: No external funding was received for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Manouchehrinia A et al. Smoking attributable risk in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:840158 (Mar 3). Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.840158

Key clinical point: At least 13% of cases of multiple sclerosis (MS) can be prevented if tobacco smoking is avoided, indicating the need for integrated programs aimed not only at smoking cessation but also at smoking prevention.

Major finding: The overall attributable fraction (AF) of MS because of smoking was 13.1% (95% CI 10.7%-15.4%), with AF being 0.6% (95% CI 0%-2%) in ex-smokers, indicating the beneficial effects of smoking cessation. Ever-smokers were at a 41% (95% CI 1.33%-1.50%) increased risk for MS than never smokers.

Study details: This was a population-based matched case-control study including 9,419 patients with MS and 9,419 matched control individuals.

Disclosures: No external funding was received for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Manouchehrinia A et al. Smoking attributable risk in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:840158 (Mar 3). Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.840158

RMS: Extended ofatumumab treatment presents favorable benefit-risk profile in ALITHIOS study

Key clinical point: Extended treatment with ofatumumab for up to 3.5 years was well tolerated without any new risks in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS).

Major finding: Overall, 83.8% and 9.7% of patients experienced at least 1 adverse event (AE) and serious AE, respectively. Systemic injection-related reactions, infections, and malignancies were reported in 24.8%, 54.3%, and 0.3% of patients, respectively. In most patients, the mean serum immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM levels were stable and above the lower limit of normal and the risk for serious infections was low.

Study details: Findings are from the ongoing phase 3b ALITHIOS umbrella extension trial involving 1,969 patients with RMS who completed ASCLEPIOS I/II, APLIOS, or APOLITOS trial and continued or switched to ofatumumab in ALITHIOS.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland). The authors declared receiving consultancy fees, personal compensation, travel reimbursement, research support, or serving on advisory boards for various sources including Novartis Pharma AG. Some authors declared being employees of Novartis Pharma AG.

Source: Hauser SL et al. Safety experience with continued exposure to ofatumumab in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis for up to 3.5 years. Mult Scler. 2022 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1177/13524585221079731

Key clinical point: Extended treatment with ofatumumab for up to 3.5 years was well tolerated without any new risks in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS).

Major finding: Overall, 83.8% and 9.7% of patients experienced at least 1 adverse event (AE) and serious AE, respectively. Systemic injection-related reactions, infections, and malignancies were reported in 24.8%, 54.3%, and 0.3% of patients, respectively. In most patients, the mean serum immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM levels were stable and above the lower limit of normal and the risk for serious infections was low.

Study details: Findings are from the ongoing phase 3b ALITHIOS umbrella extension trial involving 1,969 patients with RMS who completed ASCLEPIOS I/II, APLIOS, or APOLITOS trial and continued or switched to ofatumumab in ALITHIOS.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland). The authors declared receiving consultancy fees, personal compensation, travel reimbursement, research support, or serving on advisory boards for various sources including Novartis Pharma AG. Some authors declared being employees of Novartis Pharma AG.

Source: Hauser SL et al. Safety experience with continued exposure to ofatumumab in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis for up to 3.5 years. Mult Scler. 2022 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1177/13524585221079731

Key clinical point: Extended treatment with ofatumumab for up to 3.5 years was well tolerated without any new risks in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS).

Major finding: Overall, 83.8% and 9.7% of patients experienced at least 1 adverse event (AE) and serious AE, respectively. Systemic injection-related reactions, infections, and malignancies were reported in 24.8%, 54.3%, and 0.3% of patients, respectively. In most patients, the mean serum immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM levels were stable and above the lower limit of normal and the risk for serious infections was low.

Study details: Findings are from the ongoing phase 3b ALITHIOS umbrella extension trial involving 1,969 patients with RMS who completed ASCLEPIOS I/II, APLIOS, or APOLITOS trial and continued or switched to ofatumumab in ALITHIOS.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland). The authors declared receiving consultancy fees, personal compensation, travel reimbursement, research support, or serving on advisory boards for various sources including Novartis Pharma AG. Some authors declared being employees of Novartis Pharma AG.

Source: Hauser SL et al. Safety experience with continued exposure to ofatumumab in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis for up to 3.5 years. Mult Scler. 2022 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1177/13524585221079731

Multiple sclerosis: Discontinuing fingolimod improves humoral response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Key clinical point: Short-term fingolimod discontinuation until the absolute lymphocyte count increases to >1,000 cells/mm3 may improve the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-specific humoral response in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) but not the adaptive cellular response.

Major finding: Overall, 80% vs. 20% of patients in the fingolimod-discontinuation vs. fingolimod-continuation group developed a positive humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 1 month after the third vaccine dose, with a significantly higher median immunoglobulin (Ig) G titer in the fingolimod-discontinuation vs. fingolimod-continuation group (202.3 vs. 26.4 binding antibody units/mL; P = .022).

Study details: This was a prospective monocentric 3-month randomized clinical trial involving 20 patients with relapsing-remitting MS on fingolimod therapy who received the third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine after failing to develop a humoral IgG immune response to the previous 2 doses and were randomly assigned to the fingolimod-continuation or fingolimod-discontinuation group.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Sheba Multiple Sclerosis Research Grant. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Achiron A et al. Immune response to the third COVID-19 vaccine dose is related to lymphocyte count in multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod. J Neurol. 2022 (Mar 2). Doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11030-0

Key clinical point: Short-term fingolimod discontinuation until the absolute lymphocyte count increases to >1,000 cells/mm3 may improve the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-specific humoral response in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) but not the adaptive cellular response.

Major finding: Overall, 80% vs. 20% of patients in the fingolimod-discontinuation vs. fingolimod-continuation group developed a positive humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 1 month after the third vaccine dose, with a significantly higher median immunoglobulin (Ig) G titer in the fingolimod-discontinuation vs. fingolimod-continuation group (202.3 vs. 26.4 binding antibody units/mL; P = .022).

Study details: This was a prospective monocentric 3-month randomized clinical trial involving 20 patients with relapsing-remitting MS on fingolimod therapy who received the third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine after failing to develop a humoral IgG immune response to the previous 2 doses and were randomly assigned to the fingolimod-continuation or fingolimod-discontinuation group.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Sheba Multiple Sclerosis Research Grant. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Achiron A et al. Immune response to the third COVID-19 vaccine dose is related to lymphocyte count in multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod. J Neurol. 2022 (Mar 2). Doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11030-0

Key clinical point: Short-term fingolimod discontinuation until the absolute lymphocyte count increases to >1,000 cells/mm3 may improve the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-specific humoral response in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) but not the adaptive cellular response.

Major finding: Overall, 80% vs. 20% of patients in the fingolimod-discontinuation vs. fingolimod-continuation group developed a positive humoral response against SARS-CoV-2 1 month after the third vaccine dose, with a significantly higher median immunoglobulin (Ig) G titer in the fingolimod-discontinuation vs. fingolimod-continuation group (202.3 vs. 26.4 binding antibody units/mL; P = .022).

Study details: This was a prospective monocentric 3-month randomized clinical trial involving 20 patients with relapsing-remitting MS on fingolimod therapy who received the third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine after failing to develop a humoral IgG immune response to the previous 2 doses and were randomly assigned to the fingolimod-continuation or fingolimod-discontinuation group.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Sheba Multiple Sclerosis Research Grant. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Achiron A et al. Immune response to the third COVID-19 vaccine dose is related to lymphocyte count in multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod. J Neurol. 2022 (Mar 2). Doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11030-0

Flu vaccination does not increase risk for infections or relapse in MS

Key clinical point: Vaccination against influenza was well tolerated in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who mainly experienced short-term nonserious adverse events following immunization (AEFI), with the risk for MS relapse not being significantly different than those who were not vaccinated.

Major finding: Overall, 60.2% of patients did not experience any vaccine-related AEFIs, with pain at the injection site (68.1%), headache (10.6%), flu-like symptoms (17%), and fatigue (4.3%) being the major nonserious short-term AEFIs. The long-term AEFIs included flu-like symptoms, COVID-19, and MS relapse, with incidences of infection or MS relapse (P = .65) and cumulative survival rate (P = .21) not being significantly different between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.

Study details: This was a single-center, prospective, vaccination-vigilance trial including 194 patients with MS, of whom 113 patients received any of the recommended flu vaccines and 81 did not.

Disclosures: The study received no external funding. GT Maniscalco declared serving on speaking and advisory boards and receiving speaker fees from various sources. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Maniscalco GT et al. Flu vaccination in multiple sclerosis patients: A monocentric prospective vaccine-vigilance study. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022 (Feb 22). Doi: 10.1080/14740338.2022.2044787

Key clinical point: Vaccination against influenza was well tolerated in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who mainly experienced short-term nonserious adverse events following immunization (AEFI), with the risk for MS relapse not being significantly different than those who were not vaccinated.

Major finding: Overall, 60.2% of patients did not experience any vaccine-related AEFIs, with pain at the injection site (68.1%), headache (10.6%), flu-like symptoms (17%), and fatigue (4.3%) being the major nonserious short-term AEFIs. The long-term AEFIs included flu-like symptoms, COVID-19, and MS relapse, with incidences of infection or MS relapse (P = .65) and cumulative survival rate (P = .21) not being significantly different between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.

Study details: This was a single-center, prospective, vaccination-vigilance trial including 194 patients with MS, of whom 113 patients received any of the recommended flu vaccines and 81 did not.

Disclosures: The study received no external funding. GT Maniscalco declared serving on speaking and advisory boards and receiving speaker fees from various sources. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Maniscalco GT et al. Flu vaccination in multiple sclerosis patients: A monocentric prospective vaccine-vigilance study. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022 (Feb 22). Doi: 10.1080/14740338.2022.2044787

Key clinical point: Vaccination against influenza was well tolerated in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who mainly experienced short-term nonserious adverse events following immunization (AEFI), with the risk for MS relapse not being significantly different than those who were not vaccinated.

Major finding: Overall, 60.2% of patients did not experience any vaccine-related AEFIs, with pain at the injection site (68.1%), headache (10.6%), flu-like symptoms (17%), and fatigue (4.3%) being the major nonserious short-term AEFIs. The long-term AEFIs included flu-like symptoms, COVID-19, and MS relapse, with incidences of infection or MS relapse (P = .65) and cumulative survival rate (P = .21) not being significantly different between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.

Study details: This was a single-center, prospective, vaccination-vigilance trial including 194 patients with MS, of whom 113 patients received any of the recommended flu vaccines and 81 did not.

Disclosures: The study received no external funding. GT Maniscalco declared serving on speaking and advisory boards and receiving speaker fees from various sources. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Maniscalco GT et al. Flu vaccination in multiple sclerosis patients: A monocentric prospective vaccine-vigilance study. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022 (Feb 22). Doi: 10.1080/14740338.2022.2044787

Hormone therapy use and disability accrual in women with MS

Key clinical point: Over 22 years of follow-up found no association between the use of hormone therapy (HT) and the risk for disability accrual in women with multiple sclerosis (MS) treated with a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) when used for <5 years.

Major finding: Overall, current HT use vs. no use was not associated with a significantly higher risk for disability accrual; however, the risk of reaching 6-month confirmed and sustained Expanded Disability Status Scale 4 increased from 0.6 (95% CI 0.3-1.2) after <1 year of use to 1.4 (95% CI 0.9-2.2) after >5 years of HT use vs. no use.

Study details: The data come from a nationwide, population-based cohort study of 3,325 women with relapsing-remitting MS treated with DMT.

Disclosures: This study received no external funding. TI Kopp revealed his role as an adviser for Novartis and received Biogen's sponsorship for congress participation. M Magyari declared serving as an advisor and receiving honoraria for lecturing and research support for congress participation from various sources. Ø Lidegaard had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kopp TI et al. Hormone therapy and disease activity in Danish women with multiple sclerosis: A population-based cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Feb 23). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15299

Key clinical point: Over 22 years of follow-up found no association between the use of hormone therapy (HT) and the risk for disability accrual in women with multiple sclerosis (MS) treated with a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) when used for <5 years.

Major finding: Overall, current HT use vs. no use was not associated with a significantly higher risk for disability accrual; however, the risk of reaching 6-month confirmed and sustained Expanded Disability Status Scale 4 increased from 0.6 (95% CI 0.3-1.2) after <1 year of use to 1.4 (95% CI 0.9-2.2) after >5 years of HT use vs. no use.

Study details: The data come from a nationwide, population-based cohort study of 3,325 women with relapsing-remitting MS treated with DMT.

Disclosures: This study received no external funding. TI Kopp revealed his role as an adviser for Novartis and received Biogen's sponsorship for congress participation. M Magyari declared serving as an advisor and receiving honoraria for lecturing and research support for congress participation from various sources. Ø Lidegaard had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kopp TI et al. Hormone therapy and disease activity in Danish women with multiple sclerosis: A population-based cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Feb 23). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15299

Key clinical point: Over 22 years of follow-up found no association between the use of hormone therapy (HT) and the risk for disability accrual in women with multiple sclerosis (MS) treated with a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) when used for <5 years.

Major finding: Overall, current HT use vs. no use was not associated with a significantly higher risk for disability accrual; however, the risk of reaching 6-month confirmed and sustained Expanded Disability Status Scale 4 increased from 0.6 (95% CI 0.3-1.2) after <1 year of use to 1.4 (95% CI 0.9-2.2) after >5 years of HT use vs. no use.

Study details: The data come from a nationwide, population-based cohort study of 3,325 women with relapsing-remitting MS treated with DMT.

Disclosures: This study received no external funding. TI Kopp revealed his role as an adviser for Novartis and received Biogen's sponsorship for congress participation. M Magyari declared serving as an advisor and receiving honoraria for lecturing and research support for congress participation from various sources. Ø Lidegaard had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kopp TI et al. Hormone therapy and disease activity in Danish women with multiple sclerosis: A population-based cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Feb 23). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15299

Purulent Nodule on the Mandible

The Diagnosis: Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus Tract

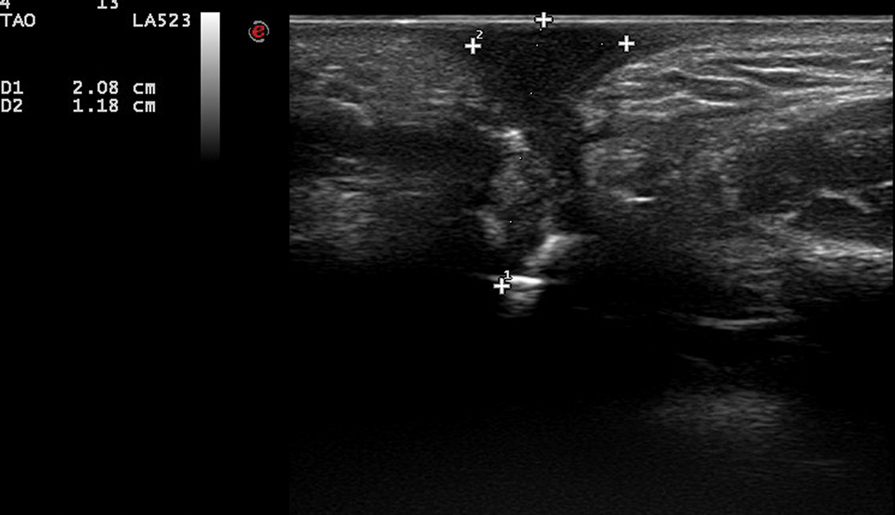

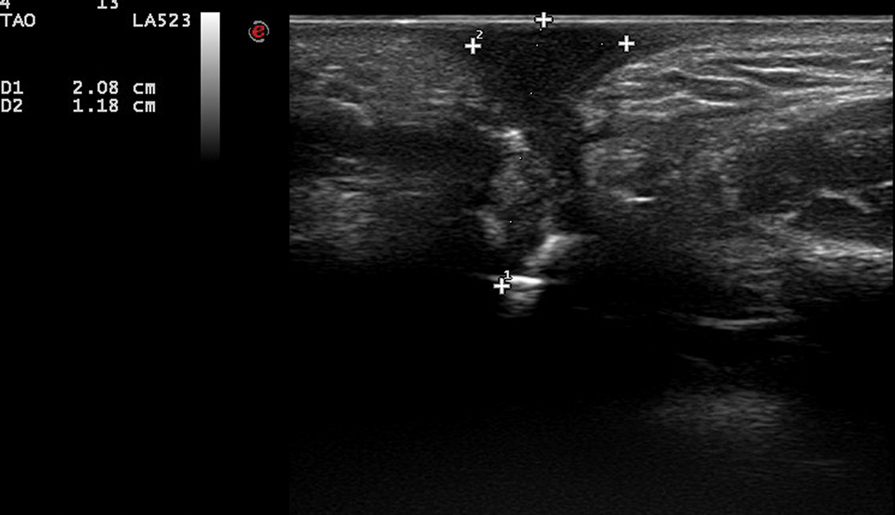

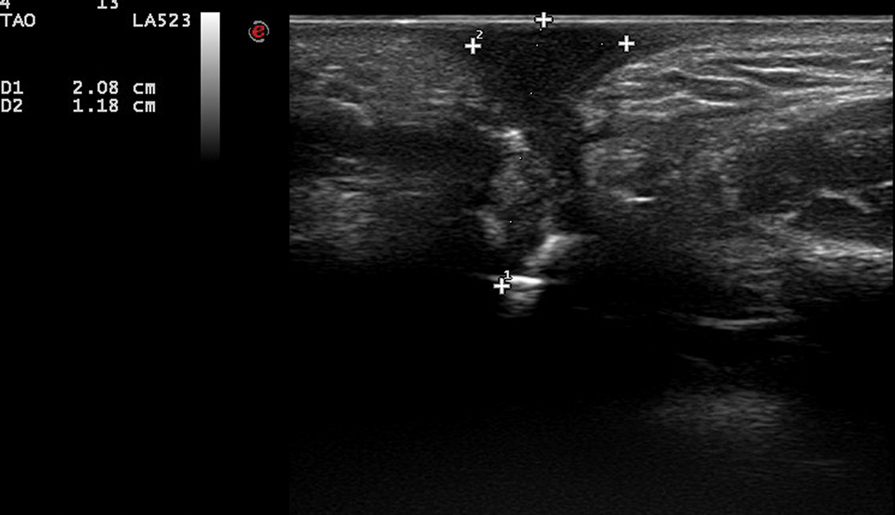

In our patient, panoramic radiography showed a radiolucency in the periapex of the mandibular first molar (Figure 1). Ultrasonography depicted a hypoechoic band that originated from the cutaneous lesion and extended through the subcutaneous tissue to the defective alveolar bone, suggesting odontogenic inflammation (Figure 2).1 The infected pulp was removed, and the purulent nodules then disappeared.

The dental etiology of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts can be confirmed by panoramic radiography and ultrasonography. The odontogenic sinus path can be clearly observed via radiography by injecting or inserting a radiopaque substance into the sinus tract.2 Effective treatment of the diseased tooth is removal of the infected pulp, performance of a root canal to eliminate infection, closure and filling of the root canal, and repair of the crown. Once the source of infection is eliminated, the sinus typically subsides within 2 weeks. When residual skin retreats or scars are present, cosmetic surgery can be performed to improve the appearance.3,4

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts usually are caused by a route of drainage from a chronic apical abscess. They follow a path of least resistance through the alveolar bone and periosteum, spreading into the surrounding soft tissues. With the formation of abscesses, sinus tracts will erupt intraorally or cutaneously, depending on the relationship of the posterior tooth apices to the mandibular attachments of the mylohyoid and buccinator muscles and the maxillary attachment of the buccinator.2,5 Clinically, cutaneous lesions present as nodules, cysts, or dimples that have attached to deep tissues through the sinus tract. Half of patients may have no dental symptoms and often are misdiagnosed with nonodontogenic lesions. Subsequent improper treatments, such as repeated use of antibiotics, multiple biopsies, surgical excision, and chemotherapy, often are repeated and ineffective.6 The most common cause of chronic cutaneous sinus tracts in the face and neck is a chronically draining dental infection.2,5 A thorough history is necessary when odontogenic cutaneous sinuses are suspected. Toothache before the development of the sinus tract is an important diagnostic clue.

Pyogenic granuloma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, osteomyelitis, infected epidermoid cyst, actinomycoses, and salivary gland fistula also should be considered in the differential diagnosis.7-10 Pyogenic granuloma (also known as lobular capillary hemangioma) is a benign overgrowth of capillaries showing a vascular phenotype that usually occurs as a response to different stimulating factors such as local stimuli, trauma, or hormonal factors. Clinically, pyogenic granuloma presents as a red, solitary, painless nodule on the face or distal extremities.11,12 Syringocystadenoma papilliferum is a benign adnexal proliferation with apocrine differentiation that usually presents as a hairless papillomatous plaque or nodule measuring 1 to 4 cm in diameter and often is first noted at birth or during early childhood.7 Osteomyelitis is progressive inflammation of the periosteum and bone marrow that rapidly breaks through the periosteum and spreads to surrounding areas. The mandible is the most susceptible bone for facial osteomyelitis.8 Epidermoid cysts are formed by the proliferation of epidermal cells within a circumscribed dermal space. Infection of the cysts is characterized by redness, swelling, heat, and pain. As the infection progresses, suppurative inflammation develops, leading to local liquefaction and abscesses.9

This case was initially misdiagnosed as infectious skin lesions by outside clinicians. Multiple surgical treatments and long-term antibiotic therapy were attempted before the correct diagnosis was made. The clinical diagnosis of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts is challenging due to the variety of affected sites and clinical signs. Ultrasonography should be performed as early as possible to identify the disease and avoid unnecessary surgery. For appropriate dental therapy, close liaison with the stomatology department is warranted.

- Shobatake C, Miyagawa F, Fukumoto T, et al. Usefulness of ultrasonography for rapidly diagnosing cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:683-687.

- Cioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:94-100.

- McWalter GM, Alexander JB, del Rio CE, et al. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:608-614.

- Spear KL, Sheridan PJ, Perry HO. Sinus tracts to the chin and jaw of dental origin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:486-492.

- Lewin-Epstein J, Taicher S, Azaz B. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1158-1161.

- Mittal N, Gupta P. Management of extraoral sinus cases: a clinical dilemma. J Endod. 2004;30:541-547.

- Alegria-Landa V, Jo-Velasco M, Santonja C, et al. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum associated with verrucous carcinoma of the skin in the same lesion: report of four cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:12-16.

- Prasad KC, Prasad SC, Mouli N, et al. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:194-205.

- Hong SH, Chung HW, Choi JY, et al. MRI findings of subcutaneous epidermal cysts: emphasis on the presence of rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:961-966.

- Gefrerer L, Popowski W, Perek JN, et al. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma around dental implants: a rare case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016;36:573-581.

- Chae JB, Park JT, Kim BR, et al. Agminated eruptive pyogenic granuloma on chin following redundant needle injections. J Dermatol. 2016;43:577-578.

- Thompson LD. Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) of the oral cavity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:240.

The Diagnosis: Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus Tract

In our patient, panoramic radiography showed a radiolucency in the periapex of the mandibular first molar (Figure 1). Ultrasonography depicted a hypoechoic band that originated from the cutaneous lesion and extended through the subcutaneous tissue to the defective alveolar bone, suggesting odontogenic inflammation (Figure 2).1 The infected pulp was removed, and the purulent nodules then disappeared.

The dental etiology of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts can be confirmed by panoramic radiography and ultrasonography. The odontogenic sinus path can be clearly observed via radiography by injecting or inserting a radiopaque substance into the sinus tract.2 Effective treatment of the diseased tooth is removal of the infected pulp, performance of a root canal to eliminate infection, closure and filling of the root canal, and repair of the crown. Once the source of infection is eliminated, the sinus typically subsides within 2 weeks. When residual skin retreats or scars are present, cosmetic surgery can be performed to improve the appearance.3,4

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts usually are caused by a route of drainage from a chronic apical abscess. They follow a path of least resistance through the alveolar bone and periosteum, spreading into the surrounding soft tissues. With the formation of abscesses, sinus tracts will erupt intraorally or cutaneously, depending on the relationship of the posterior tooth apices to the mandibular attachments of the mylohyoid and buccinator muscles and the maxillary attachment of the buccinator.2,5 Clinically, cutaneous lesions present as nodules, cysts, or dimples that have attached to deep tissues through the sinus tract. Half of patients may have no dental symptoms and often are misdiagnosed with nonodontogenic lesions. Subsequent improper treatments, such as repeated use of antibiotics, multiple biopsies, surgical excision, and chemotherapy, often are repeated and ineffective.6 The most common cause of chronic cutaneous sinus tracts in the face and neck is a chronically draining dental infection.2,5 A thorough history is necessary when odontogenic cutaneous sinuses are suspected. Toothache before the development of the sinus tract is an important diagnostic clue.

Pyogenic granuloma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, osteomyelitis, infected epidermoid cyst, actinomycoses, and salivary gland fistula also should be considered in the differential diagnosis.7-10 Pyogenic granuloma (also known as lobular capillary hemangioma) is a benign overgrowth of capillaries showing a vascular phenotype that usually occurs as a response to different stimulating factors such as local stimuli, trauma, or hormonal factors. Clinically, pyogenic granuloma presents as a red, solitary, painless nodule on the face or distal extremities.11,12 Syringocystadenoma papilliferum is a benign adnexal proliferation with apocrine differentiation that usually presents as a hairless papillomatous plaque or nodule measuring 1 to 4 cm in diameter and often is first noted at birth or during early childhood.7 Osteomyelitis is progressive inflammation of the periosteum and bone marrow that rapidly breaks through the periosteum and spreads to surrounding areas. The mandible is the most susceptible bone for facial osteomyelitis.8 Epidermoid cysts are formed by the proliferation of epidermal cells within a circumscribed dermal space. Infection of the cysts is characterized by redness, swelling, heat, and pain. As the infection progresses, suppurative inflammation develops, leading to local liquefaction and abscesses.9

This case was initially misdiagnosed as infectious skin lesions by outside clinicians. Multiple surgical treatments and long-term antibiotic therapy were attempted before the correct diagnosis was made. The clinical diagnosis of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts is challenging due to the variety of affected sites and clinical signs. Ultrasonography should be performed as early as possible to identify the disease and avoid unnecessary surgery. For appropriate dental therapy, close liaison with the stomatology department is warranted.

The Diagnosis: Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus Tract

In our patient, panoramic radiography showed a radiolucency in the periapex of the mandibular first molar (Figure 1). Ultrasonography depicted a hypoechoic band that originated from the cutaneous lesion and extended through the subcutaneous tissue to the defective alveolar bone, suggesting odontogenic inflammation (Figure 2).1 The infected pulp was removed, and the purulent nodules then disappeared.

The dental etiology of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts can be confirmed by panoramic radiography and ultrasonography. The odontogenic sinus path can be clearly observed via radiography by injecting or inserting a radiopaque substance into the sinus tract.2 Effective treatment of the diseased tooth is removal of the infected pulp, performance of a root canal to eliminate infection, closure and filling of the root canal, and repair of the crown. Once the source of infection is eliminated, the sinus typically subsides within 2 weeks. When residual skin retreats or scars are present, cosmetic surgery can be performed to improve the appearance.3,4

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts usually are caused by a route of drainage from a chronic apical abscess. They follow a path of least resistance through the alveolar bone and periosteum, spreading into the surrounding soft tissues. With the formation of abscesses, sinus tracts will erupt intraorally or cutaneously, depending on the relationship of the posterior tooth apices to the mandibular attachments of the mylohyoid and buccinator muscles and the maxillary attachment of the buccinator.2,5 Clinically, cutaneous lesions present as nodules, cysts, or dimples that have attached to deep tissues through the sinus tract. Half of patients may have no dental symptoms and often are misdiagnosed with nonodontogenic lesions. Subsequent improper treatments, such as repeated use of antibiotics, multiple biopsies, surgical excision, and chemotherapy, often are repeated and ineffective.6 The most common cause of chronic cutaneous sinus tracts in the face and neck is a chronically draining dental infection.2,5 A thorough history is necessary when odontogenic cutaneous sinuses are suspected. Toothache before the development of the sinus tract is an important diagnostic clue.

Pyogenic granuloma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, osteomyelitis, infected epidermoid cyst, actinomycoses, and salivary gland fistula also should be considered in the differential diagnosis.7-10 Pyogenic granuloma (also known as lobular capillary hemangioma) is a benign overgrowth of capillaries showing a vascular phenotype that usually occurs as a response to different stimulating factors such as local stimuli, trauma, or hormonal factors. Clinically, pyogenic granuloma presents as a red, solitary, painless nodule on the face or distal extremities.11,12 Syringocystadenoma papilliferum is a benign adnexal proliferation with apocrine differentiation that usually presents as a hairless papillomatous plaque or nodule measuring 1 to 4 cm in diameter and often is first noted at birth or during early childhood.7 Osteomyelitis is progressive inflammation of the periosteum and bone marrow that rapidly breaks through the periosteum and spreads to surrounding areas. The mandible is the most susceptible bone for facial osteomyelitis.8 Epidermoid cysts are formed by the proliferation of epidermal cells within a circumscribed dermal space. Infection of the cysts is characterized by redness, swelling, heat, and pain. As the infection progresses, suppurative inflammation develops, leading to local liquefaction and abscesses.9

This case was initially misdiagnosed as infectious skin lesions by outside clinicians. Multiple surgical treatments and long-term antibiotic therapy were attempted before the correct diagnosis was made. The clinical diagnosis of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts is challenging due to the variety of affected sites and clinical signs. Ultrasonography should be performed as early as possible to identify the disease and avoid unnecessary surgery. For appropriate dental therapy, close liaison with the stomatology department is warranted.

- Shobatake C, Miyagawa F, Fukumoto T, et al. Usefulness of ultrasonography for rapidly diagnosing cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:683-687.

- Cioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:94-100.

- McWalter GM, Alexander JB, del Rio CE, et al. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:608-614.

- Spear KL, Sheridan PJ, Perry HO. Sinus tracts to the chin and jaw of dental origin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:486-492.

- Lewin-Epstein J, Taicher S, Azaz B. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1158-1161.

- Mittal N, Gupta P. Management of extraoral sinus cases: a clinical dilemma. J Endod. 2004;30:541-547.

- Alegria-Landa V, Jo-Velasco M, Santonja C, et al. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum associated with verrucous carcinoma of the skin in the same lesion: report of four cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:12-16.

- Prasad KC, Prasad SC, Mouli N, et al. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:194-205.

- Hong SH, Chung HW, Choi JY, et al. MRI findings of subcutaneous epidermal cysts: emphasis on the presence of rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:961-966.

- Gefrerer L, Popowski W, Perek JN, et al. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma around dental implants: a rare case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016;36:573-581.

- Chae JB, Park JT, Kim BR, et al. Agminated eruptive pyogenic granuloma on chin following redundant needle injections. J Dermatol. 2016;43:577-578.

- Thompson LD. Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) of the oral cavity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:240.

- Shobatake C, Miyagawa F, Fukumoto T, et al. Usefulness of ultrasonography for rapidly diagnosing cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:683-687.

- Cioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:94-100.

- McWalter GM, Alexander JB, del Rio CE, et al. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:608-614.

- Spear KL, Sheridan PJ, Perry HO. Sinus tracts to the chin and jaw of dental origin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:486-492.

- Lewin-Epstein J, Taicher S, Azaz B. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1158-1161.

- Mittal N, Gupta P. Management of extraoral sinus cases: a clinical dilemma. J Endod. 2004;30:541-547.

- Alegria-Landa V, Jo-Velasco M, Santonja C, et al. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum associated with verrucous carcinoma of the skin in the same lesion: report of four cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:12-16.

- Prasad KC, Prasad SC, Mouli N, et al. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:194-205.

- Hong SH, Chung HW, Choi JY, et al. MRI findings of subcutaneous epidermal cysts: emphasis on the presence of rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:961-966.

- Gefrerer L, Popowski W, Perek JN, et al. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma around dental implants: a rare case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016;36:573-581.

- Chae JB, Park JT, Kim BR, et al. Agminated eruptive pyogenic granuloma on chin following redundant needle injections. J Dermatol. 2016;43:577-578.

- Thompson LD. Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) of the oral cavity. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:240.

A 27-year-old man presented with a recurrent nodule with purulent discharge on the mandible of 3 months’ duration. He underwent several surgical excisions before he was referred to our outpatient clinic, but each time the lesion recurred. The patient was otherwise healthy with no associated discomfort. He denied exposure to animals or ticks, and he did not have a family history of similar lesions. He had a root canal treatment several years prior to the current presentation. Physical examination revealed 2 contiguous nodules with purulent secretions on the left mandible.

Masitinib at 4.5 mg/kg/day shows promise in progressive forms of multiple sclerosis

Key clinical point: Masitinib at a dose of 4.5 mg/kg/day may benefit patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) or nonactive secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (nSPMS).

Major finding: The Expanded Disability Status Scale(EDSS)-based disability worsening was slower with 4.5 mg/kg/day masitinib 4.5 mg/kg/day vs. placebo (change in EDSS 0.001 vs. 0.098), with a between-group difference of −0.097 (P = .027). No new safety signals were identified.

Study details: The findings come from the 96-week, phase 3 Study AB07002 trial involving 611 patients with PPMS or nSPMS who were randomly assigned to parallel groups of either 4.5 mg/kg/day masitinib, 6 mg/kg/day uptitrated masitinib, or an equivalent placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AB Science, Paris, France. A Moussy, C Mansfield, and O Hermine reported being employees and shareholders of AB Science, and the other authors reported receiving research support and nonfinancial support or personal fees from various sources, including AB Science.

Source: Vermersch P et al, on behalf of the AB07002 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of masitinib in progressive forms of multiple sclerosis: A randomized, phase 3, clinical trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(3):e1148 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001148

Key clinical point: Masitinib at a dose of 4.5 mg/kg/day may benefit patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) or nonactive secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (nSPMS).

Major finding: The Expanded Disability Status Scale(EDSS)-based disability worsening was slower with 4.5 mg/kg/day masitinib 4.5 mg/kg/day vs. placebo (change in EDSS 0.001 vs. 0.098), with a between-group difference of −0.097 (P = .027). No new safety signals were identified.

Study details: The findings come from the 96-week, phase 3 Study AB07002 trial involving 611 patients with PPMS or nSPMS who were randomly assigned to parallel groups of either 4.5 mg/kg/day masitinib, 6 mg/kg/day uptitrated masitinib, or an equivalent placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AB Science, Paris, France. A Moussy, C Mansfield, and O Hermine reported being employees and shareholders of AB Science, and the other authors reported receiving research support and nonfinancial support or personal fees from various sources, including AB Science.

Source: Vermersch P et al, on behalf of the AB07002 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of masitinib in progressive forms of multiple sclerosis: A randomized, phase 3, clinical trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(3):e1148 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001148

Key clinical point: Masitinib at a dose of 4.5 mg/kg/day may benefit patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) or nonactive secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (nSPMS).

Major finding: The Expanded Disability Status Scale(EDSS)-based disability worsening was slower with 4.5 mg/kg/day masitinib 4.5 mg/kg/day vs. placebo (change in EDSS 0.001 vs. 0.098), with a between-group difference of −0.097 (P = .027). No new safety signals were identified.

Study details: The findings come from the 96-week, phase 3 Study AB07002 trial involving 611 patients with PPMS or nSPMS who were randomly assigned to parallel groups of either 4.5 mg/kg/day masitinib, 6 mg/kg/day uptitrated masitinib, or an equivalent placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AB Science, Paris, France. A Moussy, C Mansfield, and O Hermine reported being employees and shareholders of AB Science, and the other authors reported receiving research support and nonfinancial support or personal fees from various sources, including AB Science.

Source: Vermersch P et al, on behalf of the AB07002 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of masitinib in progressive forms of multiple sclerosis: A randomized, phase 3, clinical trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(3):e1148 (Feb 21). Doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001148

Plasma S100A12 and Apo-A1 levels in untreated RRMS patients and their at-risk family members

Key clinical point: Plasma levels of S100A12 and apolipoprotein A1 (Apo-A1) could serve as effective biomarkers for the early detection and screening of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in patients with early disease and those at high risk.

Major finding: The mean plasma S100A12 level was significantly lower in patients with new untreated RRMS (36.781 pg/mL) and their first-degree family members (15.979 pg/mL) vs. healthy control (HC) participants (42.586 pg/mL; P ≤ .05). Mean plasma Apo-A1 levels were significantly lower in the first-degree family members of patients with RRMS vs. HC participants (111.78 pg/mL vs. 205.88 pg/mL; P ≤ .05).

Study details: The study involved 35 patients with new untreated RRMS, 26 first-degree relatives of patients with RRMS, and 24 participants who formed the HC group.

Disclosure: No source of funding was declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Samangooei M et al. Evaluation of S100A12 and Apo-A1 plasma level potency in untreated new relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis patients and their family members. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2160 (Feb 9). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06322-4

Key clinical point: Plasma levels of S100A12 and apolipoprotein A1 (Apo-A1) could serve as effective biomarkers for the early detection and screening of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in patients with early disease and those at high risk.

Major finding: The mean plasma S100A12 level was significantly lower in patients with new untreated RRMS (36.781 pg/mL) and their first-degree family members (15.979 pg/mL) vs. healthy control (HC) participants (42.586 pg/mL; P ≤ .05). Mean plasma Apo-A1 levels were significantly lower in the first-degree family members of patients with RRMS vs. HC participants (111.78 pg/mL vs. 205.88 pg/mL; P ≤ .05).

Study details: The study involved 35 patients with new untreated RRMS, 26 first-degree relatives of patients with RRMS, and 24 participants who formed the HC group.

Disclosure: No source of funding was declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Samangooei M et al. Evaluation of S100A12 and Apo-A1 plasma level potency in untreated new relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis patients and their family members. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2160 (Feb 9). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06322-4

Key clinical point: Plasma levels of S100A12 and apolipoprotein A1 (Apo-A1) could serve as effective biomarkers for the early detection and screening of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in patients with early disease and those at high risk.

Major finding: The mean plasma S100A12 level was significantly lower in patients with new untreated RRMS (36.781 pg/mL) and their first-degree family members (15.979 pg/mL) vs. healthy control (HC) participants (42.586 pg/mL; P ≤ .05). Mean plasma Apo-A1 levels were significantly lower in the first-degree family members of patients with RRMS vs. HC participants (111.78 pg/mL vs. 205.88 pg/mL; P ≤ .05).

Study details: The study involved 35 patients with new untreated RRMS, 26 first-degree relatives of patients with RRMS, and 24 participants who formed the HC group.

Disclosure: No source of funding was declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Samangooei M et al. Evaluation of S100A12 and Apo-A1 plasma level potency in untreated new relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis patients and their family members. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2160 (Feb 9). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06322-4

BCG vaccination and risk for relapsing-remitting MS: Is there a link?

Key clinical point: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination had no effect on the incidence of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), but was positively associated with the incidence of MS diagnosed later in life.

Major finding: BCG vaccination was not associated with the incidence of RRMS during the entire follow-up period (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.01; 95% CI 0.85-1.20), but was positively associated with the incidence of MS diagnosed later in life (aHR 1.22; 95% CI 1.09-1.36).

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 400,563 individuals from the Quebec Birth Cohort for Immunity and Health (QBCIH) who were followed up from 1983 to 2014.

Disclosures: The establishment of QBCIH was supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation; Québec Ministry of Education, Leisure, and Sports; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé, and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Corsenac P et al. Bacillus Calmette–Guerin vaccination and multiple sclerosis: A population-based birth cohort study in Quebec, Canada. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15290

Key clinical point: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination had no effect on the incidence of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), but was positively associated with the incidence of MS diagnosed later in life.

Major finding: BCG vaccination was not associated with the incidence of RRMS during the entire follow-up period (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.01; 95% CI 0.85-1.20), but was positively associated with the incidence of MS diagnosed later in life (aHR 1.22; 95% CI 1.09-1.36).

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 400,563 individuals from the Quebec Birth Cohort for Immunity and Health (QBCIH) who were followed up from 1983 to 2014.

Disclosures: The establishment of QBCIH was supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation; Québec Ministry of Education, Leisure, and Sports; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé, and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Corsenac P et al. Bacillus Calmette–Guerin vaccination and multiple sclerosis: A population-based birth cohort study in Quebec, Canada. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15290

Key clinical point: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination had no effect on the incidence of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), but was positively associated with the incidence of MS diagnosed later in life.

Major finding: BCG vaccination was not associated with the incidence of RRMS during the entire follow-up period (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.01; 95% CI 0.85-1.20), but was positively associated with the incidence of MS diagnosed later in life (aHR 1.22; 95% CI 1.09-1.36).

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 400,563 individuals from the Quebec Birth Cohort for Immunity and Health (QBCIH) who were followed up from 1983 to 2014.

Disclosures: The establishment of QBCIH was supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation; Québec Ministry of Education, Leisure, and Sports; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé, and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Corsenac P et al. Bacillus Calmette–Guerin vaccination and multiple sclerosis: A population-based birth cohort study in Quebec, Canada. Eur J Neurol. 2022 (Feb 15). Doi: 10.1111/ene.15290

Is sNfL an effective biomarker for neuronal damage and drug response in MS?

Key clinical point: Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) could serve as an effective biomarker for identifying subclinical disease activity and monitoring drug response in multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major finding: An sNfL Z score of >1.5 indicated an increased risk for future disease activity in all patients with MS (odds ratio [OR] 3.15; P < .0001) and in patients considered stable without evidence of disease activity (OR 2.66; P = .034). The sNfL values could depict a treatment effectiveness hierarchy, with an estimated additive effect on sNfL Z score of −0.14 (P = .0018) for high efficacy monoclonal antibody therapy vs. oral therapy.

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 1,313 patients with relapsing or secondary progressive MS from a Swiss MS cohort and 5,390 individuals without evidence of central nervous system disease.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation, Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Alliance, Biogen, Celgene, Novartis, and Roche. Some authors declared receiving grants, travel compensation, speaker honoraria, and advisory board/lecture and consultancy fees from various sources including the funding sources.

Source: Benkert P et al. Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modelling and validation study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(3):246-257 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00009-6

Key clinical point: Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) could serve as an effective biomarker for identifying subclinical disease activity and monitoring drug response in multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major finding: An sNfL Z score of >1.5 indicated an increased risk for future disease activity in all patients with MS (odds ratio [OR] 3.15; P < .0001) and in patients considered stable without evidence of disease activity (OR 2.66; P = .034). The sNfL values could depict a treatment effectiveness hierarchy, with an estimated additive effect on sNfL Z score of −0.14 (P = .0018) for high efficacy monoclonal antibody therapy vs. oral therapy.

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 1,313 patients with relapsing or secondary progressive MS from a Swiss MS cohort and 5,390 individuals without evidence of central nervous system disease.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation, Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Alliance, Biogen, Celgene, Novartis, and Roche. Some authors declared receiving grants, travel compensation, speaker honoraria, and advisory board/lecture and consultancy fees from various sources including the funding sources.

Source: Benkert P et al. Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modelling and validation study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(3):246-257 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00009-6

Key clinical point: Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) could serve as an effective biomarker for identifying subclinical disease activity and monitoring drug response in multiple sclerosis (MS).

Major finding: An sNfL Z score of >1.5 indicated an increased risk for future disease activity in all patients with MS (odds ratio [OR] 3.15; P < .0001) and in patients considered stable without evidence of disease activity (OR 2.66; P = .034). The sNfL values could depict a treatment effectiveness hierarchy, with an estimated additive effect on sNfL Z score of −0.14 (P = .0018) for high efficacy monoclonal antibody therapy vs. oral therapy.

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 1,313 patients with relapsing or secondary progressive MS from a Swiss MS cohort and 5,390 individuals without evidence of central nervous system disease.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation, Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Alliance, Biogen, Celgene, Novartis, and Roche. Some authors declared receiving grants, travel compensation, speaker honoraria, and advisory board/lecture and consultancy fees from various sources including the funding sources.

Source: Benkert P et al. Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modelling and validation study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(3):246-257 (Mar 1). Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00009-6