User login

The science of clean skin care and the clean beauty movement

. I see numerous social media posts, blogs, and magazine articles about toxic skin care ingredients, while more patients are asking their dermatologists about clean beauty products. So, I decided it was time to dissect the issues and figure out what “clean” really means to me.

The problem is that no one agrees on a clean ingredient standard for beauty products. Many companies, like Target, Walgreens/Boots, Sephora, Neiman Marcus, Whole Foods, and Ulta, have their own varying clean standards. Even Allure magazine has a “Clean Best of Beauty” seal. California has Proposition 65, otherwise known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, which contains a list of banned chemicals “known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” In January 2021, Hawai‘i law prohibited the sale of oxybenzone and octinoxate in sunscreens in response to scientific studies showing that these ingredients “are toxic to corals and other marine life.” The Environmental Working Group (EWG) rates the safety of ingredients based on carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, allergenicity, and immunotoxicity. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), funded by the Personal Care Products Council, consists of a seven-member steering committee that has at least one dermatologist representing the American Academy of Dermatology and a toxicologist representing the Society of Toxicology. The CIR publishes detailed reviews of ingredients that can be easily found on PubMed and Google Scholar and closely reviews animal and human data and reports on safety and contact dermatitis risk.

Which clean beauty standard is best?

I reviewed most of the various standards, clean seals, laws, and safety reports and found significant discrepancies resulting from misunderstandings of the science, lack of depth in the scientific evaluations, lumping of ingredients into a larger category, or lack of data. The most salient cause of misinformation and confusion seems to be hyperbolic claims by the media and clean beauty advocates who do not understand the basic science.

When I conducted a survey of cosmetic chemists on my LinkedIn account, most of the chemists stated that “ ‘Clean Beauty’ is a marketing term, more than a scientific term.” None of the chemists could give an exact definition of clean beauty. However, I thought I needed a good answer for my patients and for doctors who want to use and recommend “clean skin care brands.”

A dermatologist’s approach to develop a clean beauty standard

Many of the standards combine all of the following into the “clean” designation: nontoxic to the environment (both the production process and the resulting ingredient), nontoxic to marine life and coral, cruelty-free (not tested on animals), hypoallergenic, lacking in known health risks (carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity), vegan, and gluten free. As a dermatologist, I am a splitter more than a lumper, so I prefer that “clean” be split into categories to make it easier to understand. With that in mind, I will focus on clean beauty ingredients only as they pertain to health: carcinogenicity, endocrine effects, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. This discussion will not consider environmental effects, reproductive toxicity (some ingredients may decrease fertility, which is beyond the scope of this article), ingredient sources, and sustainability, animal testing, or human rights violations during production. Those issues are important, of course, but for clarity and simplicity, we will focus on the health risks of skin care ingredients.

In this month’s column, I will focus on a few ingredients and will continue the discussion in subsequent columns. Please note that commercial standards such as Target standards are based on the product type (e.g., cleansers, sunscreens, or moisturizers). So, when I mention an ingredient not allowed by certain company standards, note that it can vary by product type. My comments pertain mostly to facial moisturizers and facial serums to try and simplify the information. The Good Face Project has a complete list of standards by product type, which I recommend as a resource if you want more detailed information.

Are ethanolamines safe or toxic in cosmetics?

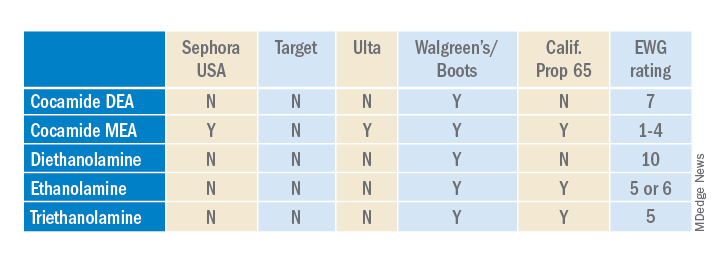

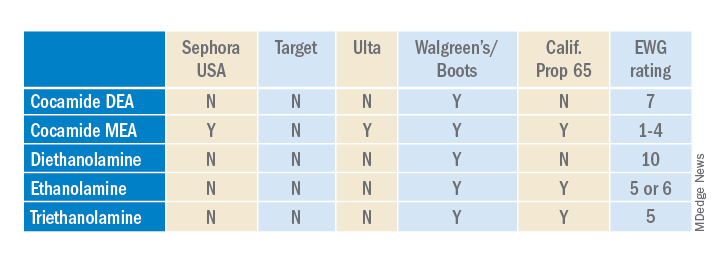

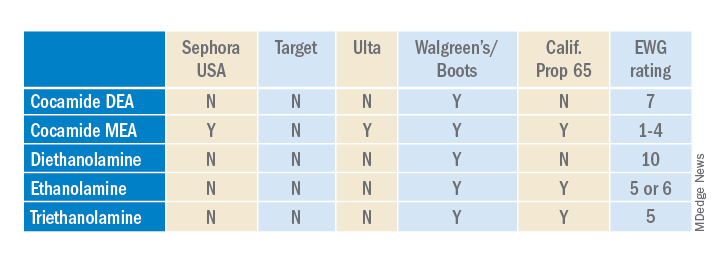

Ethanolamines are common ingredients in surfactants, fragrances, and emulsifying agents and include cocamide diethanolamine (DEA), cocamide monoethanolamine (MEA), and triethanolamine (TEA). Cocamide DEA, lauramide DEA, linoleamide DEA, and oleamide DEA are fatty acid diethanolamides that may contain 4% to 33% diethanolamine.1 A Google search of toxic ingredients in beauty products consistently identifies ethanolamines among such offending product constituents. Table 1 reveals that ethanolamines are excluded from some standards and included in others (N = not allowed or restricted by amount used and Y = allowed with no restrictions). As you can see, the standards don’t correspond to the EWG rating of the ingredients, which ranges from 1 (low hazard) to 10 (high hazard).

Why are ethanolamines sometimes considered safe and sometimes not?

Ethanolamines are reputed to be allergenic, but as we know as dermatologists, that does not mean that everyone will react to them. (In my opinion, allergenicity is a separate issue than the clean issue.) One study showed that TEA in 2.5% petrolatum had a 0.4% positive patch test rate in humans, which was thought to be related more to irritation than allergenicity.2 Cocamide DEA allergy is seen in those with hand dermatitis resulting from hand cleansers but is more commonly seen in metal workers.3 For this reason, these ethanolamines are usually found in rinse-off products to decrease exposure time. But there are many irritating ingredients not banned by Target, Sephora, and Ulta, so why does ethanolamine end up on toxic ingredient lists?

First, there is the issue of oral studies in animals. Oral forms of some ethanolamines have shown mild toxicity in rats, but topical forms have not been demonstrated to cause mutagenicity.1

For this reason, ethanolamines in their native form are considered safe.

The main issue with ethanolamines is that, when they are formulated with ingredients that break down into nitrogen, such as certain preservatives, the combination forms nitrosamines, such as N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), which are carcinogenic.4 The European Commission prohibits DEA in cosmetics based on concerns about formation of these carcinogenic nitrosamines. Some standards limit ethanolamines to rinse-off products.5 The CIR panel concluded that diethanolamine and its 16 salts are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed and that TEA and TEA-related compounds are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed.6,7 The FDA states that there is no reason for consumers to be alarmed based on the use of DEA in cosmetics.8

The safety issues surrounding the use of ethanolamines in a skin care routine illustrate an important point: Every single product in the skin care routine should be compatible with the other products in the regimen. Using ethanolamines in a rinse-off product is one solution, as is ensuring that no other products in the skin care routine contain N-nitroso compounds that can combine with ethanolamines to form nitrosamines.

Are natural products safer?

Natural products are not necessarily any safer than synthetic products. Considering ethanolamines as the example here, note that cocamide DEA is an ethanolamine derived from coconut. It is often found in “green” or “natural” skin care products.9 It can still combine with N-nitroso compounds to form carcinogenic nitrosamines.

What is the bottom line? Are ethanolamines safe in cosmetics?

For now, if a patient asks if ethanolamine is safe in skin care, my answer would be yes, so long as the following is true:

- It is in a rinse-off product.

- The patient is not allergic to it.

- They do not have hand dermatitis.

- Their skin care routine does not include nitrogen-containing compounds like N-nitrosodiethanolamine (NDELA) or NDEA.

Conclusion

This column uses ethanolamines as an example to show the disparity in clean standards in the cosmetic industry. As you can see, there are multiple factors to consider. I will begin including clean information in my cosmeceutical critique columns to address some of these issues.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Cocamide DE. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1986;5(5).

2. Lessmann H et al. Contact Dermatitis. 2009 May;60(5):243-55.

3. Aalto-Korte K et al. 2014 Mar;70(3):169-74.

4. Kraeling ME et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Oct;42(10):1553-61.

5. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2015 Sep;34(2 Suppl):84S-98S.

6. Fiume MM.. Int J Toxicol. 2017 Sep/Oct;36(5_suppl2):89S-110S.

7. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2013 May-Jun;32(3 Suppl):59S-83S.

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Diethanolamine. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/diethanolamine. Accessed Feb. 12, 2022.

9. Aryanti N et al. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 1053, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing.

. I see numerous social media posts, blogs, and magazine articles about toxic skin care ingredients, while more patients are asking their dermatologists about clean beauty products. So, I decided it was time to dissect the issues and figure out what “clean” really means to me.

The problem is that no one agrees on a clean ingredient standard for beauty products. Many companies, like Target, Walgreens/Boots, Sephora, Neiman Marcus, Whole Foods, and Ulta, have their own varying clean standards. Even Allure magazine has a “Clean Best of Beauty” seal. California has Proposition 65, otherwise known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, which contains a list of banned chemicals “known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” In January 2021, Hawai‘i law prohibited the sale of oxybenzone and octinoxate in sunscreens in response to scientific studies showing that these ingredients “are toxic to corals and other marine life.” The Environmental Working Group (EWG) rates the safety of ingredients based on carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, allergenicity, and immunotoxicity. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), funded by the Personal Care Products Council, consists of a seven-member steering committee that has at least one dermatologist representing the American Academy of Dermatology and a toxicologist representing the Society of Toxicology. The CIR publishes detailed reviews of ingredients that can be easily found on PubMed and Google Scholar and closely reviews animal and human data and reports on safety and contact dermatitis risk.

Which clean beauty standard is best?

I reviewed most of the various standards, clean seals, laws, and safety reports and found significant discrepancies resulting from misunderstandings of the science, lack of depth in the scientific evaluations, lumping of ingredients into a larger category, or lack of data. The most salient cause of misinformation and confusion seems to be hyperbolic claims by the media and clean beauty advocates who do not understand the basic science.

When I conducted a survey of cosmetic chemists on my LinkedIn account, most of the chemists stated that “ ‘Clean Beauty’ is a marketing term, more than a scientific term.” None of the chemists could give an exact definition of clean beauty. However, I thought I needed a good answer for my patients and for doctors who want to use and recommend “clean skin care brands.”

A dermatologist’s approach to develop a clean beauty standard

Many of the standards combine all of the following into the “clean” designation: nontoxic to the environment (both the production process and the resulting ingredient), nontoxic to marine life and coral, cruelty-free (not tested on animals), hypoallergenic, lacking in known health risks (carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity), vegan, and gluten free. As a dermatologist, I am a splitter more than a lumper, so I prefer that “clean” be split into categories to make it easier to understand. With that in mind, I will focus on clean beauty ingredients only as they pertain to health: carcinogenicity, endocrine effects, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. This discussion will not consider environmental effects, reproductive toxicity (some ingredients may decrease fertility, which is beyond the scope of this article), ingredient sources, and sustainability, animal testing, or human rights violations during production. Those issues are important, of course, but for clarity and simplicity, we will focus on the health risks of skin care ingredients.

In this month’s column, I will focus on a few ingredients and will continue the discussion in subsequent columns. Please note that commercial standards such as Target standards are based on the product type (e.g., cleansers, sunscreens, or moisturizers). So, when I mention an ingredient not allowed by certain company standards, note that it can vary by product type. My comments pertain mostly to facial moisturizers and facial serums to try and simplify the information. The Good Face Project has a complete list of standards by product type, which I recommend as a resource if you want more detailed information.

Are ethanolamines safe or toxic in cosmetics?

Ethanolamines are common ingredients in surfactants, fragrances, and emulsifying agents and include cocamide diethanolamine (DEA), cocamide monoethanolamine (MEA), and triethanolamine (TEA). Cocamide DEA, lauramide DEA, linoleamide DEA, and oleamide DEA are fatty acid diethanolamides that may contain 4% to 33% diethanolamine.1 A Google search of toxic ingredients in beauty products consistently identifies ethanolamines among such offending product constituents. Table 1 reveals that ethanolamines are excluded from some standards and included in others (N = not allowed or restricted by amount used and Y = allowed with no restrictions). As you can see, the standards don’t correspond to the EWG rating of the ingredients, which ranges from 1 (low hazard) to 10 (high hazard).

Why are ethanolamines sometimes considered safe and sometimes not?

Ethanolamines are reputed to be allergenic, but as we know as dermatologists, that does not mean that everyone will react to them. (In my opinion, allergenicity is a separate issue than the clean issue.) One study showed that TEA in 2.5% petrolatum had a 0.4% positive patch test rate in humans, which was thought to be related more to irritation than allergenicity.2 Cocamide DEA allergy is seen in those with hand dermatitis resulting from hand cleansers but is more commonly seen in metal workers.3 For this reason, these ethanolamines are usually found in rinse-off products to decrease exposure time. But there are many irritating ingredients not banned by Target, Sephora, and Ulta, so why does ethanolamine end up on toxic ingredient lists?

First, there is the issue of oral studies in animals. Oral forms of some ethanolamines have shown mild toxicity in rats, but topical forms have not been demonstrated to cause mutagenicity.1

For this reason, ethanolamines in their native form are considered safe.

The main issue with ethanolamines is that, when they are formulated with ingredients that break down into nitrogen, such as certain preservatives, the combination forms nitrosamines, such as N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), which are carcinogenic.4 The European Commission prohibits DEA in cosmetics based on concerns about formation of these carcinogenic nitrosamines. Some standards limit ethanolamines to rinse-off products.5 The CIR panel concluded that diethanolamine and its 16 salts are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed and that TEA and TEA-related compounds are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed.6,7 The FDA states that there is no reason for consumers to be alarmed based on the use of DEA in cosmetics.8

The safety issues surrounding the use of ethanolamines in a skin care routine illustrate an important point: Every single product in the skin care routine should be compatible with the other products in the regimen. Using ethanolamines in a rinse-off product is one solution, as is ensuring that no other products in the skin care routine contain N-nitroso compounds that can combine with ethanolamines to form nitrosamines.

Are natural products safer?

Natural products are not necessarily any safer than synthetic products. Considering ethanolamines as the example here, note that cocamide DEA is an ethanolamine derived from coconut. It is often found in “green” or “natural” skin care products.9 It can still combine with N-nitroso compounds to form carcinogenic nitrosamines.

What is the bottom line? Are ethanolamines safe in cosmetics?

For now, if a patient asks if ethanolamine is safe in skin care, my answer would be yes, so long as the following is true:

- It is in a rinse-off product.

- The patient is not allergic to it.

- They do not have hand dermatitis.

- Their skin care routine does not include nitrogen-containing compounds like N-nitrosodiethanolamine (NDELA) or NDEA.

Conclusion

This column uses ethanolamines as an example to show the disparity in clean standards in the cosmetic industry. As you can see, there are multiple factors to consider. I will begin including clean information in my cosmeceutical critique columns to address some of these issues.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Cocamide DE. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1986;5(5).

2. Lessmann H et al. Contact Dermatitis. 2009 May;60(5):243-55.

3. Aalto-Korte K et al. 2014 Mar;70(3):169-74.

4. Kraeling ME et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Oct;42(10):1553-61.

5. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2015 Sep;34(2 Suppl):84S-98S.

6. Fiume MM.. Int J Toxicol. 2017 Sep/Oct;36(5_suppl2):89S-110S.

7. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2013 May-Jun;32(3 Suppl):59S-83S.

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Diethanolamine. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/diethanolamine. Accessed Feb. 12, 2022.

9. Aryanti N et al. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 1053, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing.

. I see numerous social media posts, blogs, and magazine articles about toxic skin care ingredients, while more patients are asking their dermatologists about clean beauty products. So, I decided it was time to dissect the issues and figure out what “clean” really means to me.

The problem is that no one agrees on a clean ingredient standard for beauty products. Many companies, like Target, Walgreens/Boots, Sephora, Neiman Marcus, Whole Foods, and Ulta, have their own varying clean standards. Even Allure magazine has a “Clean Best of Beauty” seal. California has Proposition 65, otherwise known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, which contains a list of banned chemicals “known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” In January 2021, Hawai‘i law prohibited the sale of oxybenzone and octinoxate in sunscreens in response to scientific studies showing that these ingredients “are toxic to corals and other marine life.” The Environmental Working Group (EWG) rates the safety of ingredients based on carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, allergenicity, and immunotoxicity. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), funded by the Personal Care Products Council, consists of a seven-member steering committee that has at least one dermatologist representing the American Academy of Dermatology and a toxicologist representing the Society of Toxicology. The CIR publishes detailed reviews of ingredients that can be easily found on PubMed and Google Scholar and closely reviews animal and human data and reports on safety and contact dermatitis risk.

Which clean beauty standard is best?

I reviewed most of the various standards, clean seals, laws, and safety reports and found significant discrepancies resulting from misunderstandings of the science, lack of depth in the scientific evaluations, lumping of ingredients into a larger category, or lack of data. The most salient cause of misinformation and confusion seems to be hyperbolic claims by the media and clean beauty advocates who do not understand the basic science.

When I conducted a survey of cosmetic chemists on my LinkedIn account, most of the chemists stated that “ ‘Clean Beauty’ is a marketing term, more than a scientific term.” None of the chemists could give an exact definition of clean beauty. However, I thought I needed a good answer for my patients and for doctors who want to use and recommend “clean skin care brands.”

A dermatologist’s approach to develop a clean beauty standard

Many of the standards combine all of the following into the “clean” designation: nontoxic to the environment (both the production process and the resulting ingredient), nontoxic to marine life and coral, cruelty-free (not tested on animals), hypoallergenic, lacking in known health risks (carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity), vegan, and gluten free. As a dermatologist, I am a splitter more than a lumper, so I prefer that “clean” be split into categories to make it easier to understand. With that in mind, I will focus on clean beauty ingredients only as they pertain to health: carcinogenicity, endocrine effects, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. This discussion will not consider environmental effects, reproductive toxicity (some ingredients may decrease fertility, which is beyond the scope of this article), ingredient sources, and sustainability, animal testing, or human rights violations during production. Those issues are important, of course, but for clarity and simplicity, we will focus on the health risks of skin care ingredients.

In this month’s column, I will focus on a few ingredients and will continue the discussion in subsequent columns. Please note that commercial standards such as Target standards are based on the product type (e.g., cleansers, sunscreens, or moisturizers). So, when I mention an ingredient not allowed by certain company standards, note that it can vary by product type. My comments pertain mostly to facial moisturizers and facial serums to try and simplify the information. The Good Face Project has a complete list of standards by product type, which I recommend as a resource if you want more detailed information.

Are ethanolamines safe or toxic in cosmetics?

Ethanolamines are common ingredients in surfactants, fragrances, and emulsifying agents and include cocamide diethanolamine (DEA), cocamide monoethanolamine (MEA), and triethanolamine (TEA). Cocamide DEA, lauramide DEA, linoleamide DEA, and oleamide DEA are fatty acid diethanolamides that may contain 4% to 33% diethanolamine.1 A Google search of toxic ingredients in beauty products consistently identifies ethanolamines among such offending product constituents. Table 1 reveals that ethanolamines are excluded from some standards and included in others (N = not allowed or restricted by amount used and Y = allowed with no restrictions). As you can see, the standards don’t correspond to the EWG rating of the ingredients, which ranges from 1 (low hazard) to 10 (high hazard).

Why are ethanolamines sometimes considered safe and sometimes not?

Ethanolamines are reputed to be allergenic, but as we know as dermatologists, that does not mean that everyone will react to them. (In my opinion, allergenicity is a separate issue than the clean issue.) One study showed that TEA in 2.5% petrolatum had a 0.4% positive patch test rate in humans, which was thought to be related more to irritation than allergenicity.2 Cocamide DEA allergy is seen in those with hand dermatitis resulting from hand cleansers but is more commonly seen in metal workers.3 For this reason, these ethanolamines are usually found in rinse-off products to decrease exposure time. But there are many irritating ingredients not banned by Target, Sephora, and Ulta, so why does ethanolamine end up on toxic ingredient lists?

First, there is the issue of oral studies in animals. Oral forms of some ethanolamines have shown mild toxicity in rats, but topical forms have not been demonstrated to cause mutagenicity.1

For this reason, ethanolamines in their native form are considered safe.

The main issue with ethanolamines is that, when they are formulated with ingredients that break down into nitrogen, such as certain preservatives, the combination forms nitrosamines, such as N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), which are carcinogenic.4 The European Commission prohibits DEA in cosmetics based on concerns about formation of these carcinogenic nitrosamines. Some standards limit ethanolamines to rinse-off products.5 The CIR panel concluded that diethanolamine and its 16 salts are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed and that TEA and TEA-related compounds are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed.6,7 The FDA states that there is no reason for consumers to be alarmed based on the use of DEA in cosmetics.8

The safety issues surrounding the use of ethanolamines in a skin care routine illustrate an important point: Every single product in the skin care routine should be compatible with the other products in the regimen. Using ethanolamines in a rinse-off product is one solution, as is ensuring that no other products in the skin care routine contain N-nitroso compounds that can combine with ethanolamines to form nitrosamines.

Are natural products safer?

Natural products are not necessarily any safer than synthetic products. Considering ethanolamines as the example here, note that cocamide DEA is an ethanolamine derived from coconut. It is often found in “green” or “natural” skin care products.9 It can still combine with N-nitroso compounds to form carcinogenic nitrosamines.

What is the bottom line? Are ethanolamines safe in cosmetics?

For now, if a patient asks if ethanolamine is safe in skin care, my answer would be yes, so long as the following is true:

- It is in a rinse-off product.

- The patient is not allergic to it.

- They do not have hand dermatitis.

- Their skin care routine does not include nitrogen-containing compounds like N-nitrosodiethanolamine (NDELA) or NDEA.

Conclusion

This column uses ethanolamines as an example to show the disparity in clean standards in the cosmetic industry. As you can see, there are multiple factors to consider. I will begin including clean information in my cosmeceutical critique columns to address some of these issues.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Cocamide DE. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1986;5(5).

2. Lessmann H et al. Contact Dermatitis. 2009 May;60(5):243-55.

3. Aalto-Korte K et al. 2014 Mar;70(3):169-74.

4. Kraeling ME et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Oct;42(10):1553-61.

5. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2015 Sep;34(2 Suppl):84S-98S.

6. Fiume MM.. Int J Toxicol. 2017 Sep/Oct;36(5_suppl2):89S-110S.

7. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2013 May-Jun;32(3 Suppl):59S-83S.

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Diethanolamine. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/diethanolamine. Accessed Feb. 12, 2022.

9. Aryanti N et al. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 1053, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing.

Inside insulin (Part 2): Approaching a cure for type 1 diabetes?

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series commemorating the 100-year anniversary of the first use of insulin in humans. Part 1 of this series examined the rivalry behind the discovery and use of insulin.

One hundred years ago, teenager Leonard Thompson was the first patient with type 1 diabetes to be successfully treated with insulin, granting him a reprieve from what was a certain death sentence at the time.

Since then, research has gathered pace. In the century since insulin’s discovery and first use, recombinant DNA technology has allowed for the engineering of the insulin molecule, providing numerous short- and long-acting analog versions. At the same time, technological leaps in automated insulin delivery and monitoring of blood glucose ensure more time with glucose in range and fewer life-threatening complications for those with type 1 diabetes fortunate enough to have access to the technology.

In spite of these advancements, there is still scope for further evolution of disease management, with the holy grail being the transplant of stem cell–derived islet cells capable of making insulin, ideally encased in some kind of protective device so that immunosuppression is not required.

Indeed, it is not unreasonable to “hope that type 1 diabetes will be a curable disease in the next 100 years,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist who has type 1 diabetes and practices in Portland, Ore.

Type 1 diabetes: The past 100 years

The epidemiology of type 1 diabetes has shifted considerably since 1922. A century ago, given that average life expectancy in the United States was around 54 years, it was pretty much the only type of diabetes that doctors encountered. “There was some type 2 diabetes about in heavier people, but the focus was on type 1 diabetes,” noted Dr. Stephens.

Originally called juvenile diabetes because it was thought to only occur in children, “now 50% of people are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes ... over [the age of] 20,” explained Dr. Stephens.

In the United States, around 1.4 million adults 20 years and older, and 187,000 children younger than 20, have the disease, according to data from the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This total represents an increase of nearly 30% from 2017.

Over the years, theories as to the cause, or trigger, for type 1 diabetes “have included cow’s milk and [viral] infections,” said Dr. Stephens. “Most likely, there’s a genetic predisposition and some type of exposure, which creates the perfect storm to trigger disease.”

There are hints that COVID-19 might be precipitating type 1 diabetes in some people. Recently, the CDC found SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with an increased risk for diabetes (all types) among youth, but not other acute respiratory infections. And two further studies from different parts of the world have recently identified an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but the reasons remain unclear.

The global CoviDiab registry has also been established to collect data on patients with COVID-19–related diabetes.

The million-dollar question: Is COVID-19 itself is propagating type 1 diabetes or unmasking a predisposition to the disease sooner? The latter might be associated with a lower type 1 diabetes rate in the future, said Partha Kar, MBBS, OBE, national specialty advisor, diabetes, for National Health Service England.

“Right now, we don’t know the answer. Whichever way you look at it, it is likely there will be a rise in cases, and in countries where insulin is not freely available, healthcare systems need to have supply ready because insulin is lifesaving in type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Kar emphasized.

CGMs and automated insulin delivery: A ‘godsend’

A huge change has also been seen, most notably in the past 15 to 20 years, in the technological advancements that can help those with type 1 diabetes live an easier life.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated ways of delivering insulin, such as smart pens and insulin pumps, have made the daily life of a person with type 1 diabetes in the Western world considerably more comfortable.

CGMs provide a constant stream of data to an app, often wirelessly in sync with the insulin pump. However, on a global level, they are only available to a lucky few.

In England, pending National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) approval, any CGM should be available to all eligible patients with type 1 diabetes within the NHS from April 2022, Dr. Kar pointed out. In the United States, CGMs are often unaffordable and access is mostly dependent on a person’s health insurance.

Kersten Hall, PhD, a scientist and U.K.-based medical historian who recently wrote a book, “Insulin, the Crooked Timber” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2022) uncovering the lesser-known story behind the discovery of insulin, was diagnosed with adult-onset type 1 diabetes at the age of 41. Dr. Hall had always found the finger-prick blood glucose test to be a chore but now has a CGM.

“It’s a total game changer for me: a godsend. I can’t sing its praises enough,” he said. “All it involves is the swipe of the phone and this provides a reading which tells me if my glucose is too low, so I eat something, or too high, so I might [go for] a run.”

Brewing insulin at scale

As described by Dr. Hall in his book, the journey from treating Mr. Thompson in 1922 to treating the masses began when biochemist James Collip, MD, PhD, discovered a means of purifying the animal pancreas extracts used to treat the teenager.

But production at scale presented a further challenge. This was overcome in 1924 when Eli Lilly drew on a technique used in the beer brewing process – where pH guides bitterness – to purify and manufacture large amounts of insulin.

By 1936, a range of slower-acting cattle and pig-derived insulins, the first produced by Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals, were developed.

However, it took 8,000 lb (approximately 3,600 kg) of pancreas glands from 23,500 animals to make 1 lb (0.5 kg) of insulin, so a more efficient process was badly needed.

Dr. Hall, who is a molecular biologist as well as an author, explains that the use of recombinant DNA technology to produce human insulin, as done by Genentech in the late 70s, was a key development in the story of modern insulin products. Genentech then provided synthetic human insulin for Eli Lilly to conduct clinical trials.

Human insulin most closely resembles porcine insulin structure and function, differing by only one amino acid, while human insulin differs from bovine insulin by three amino acid residues. This synthetic human insulin eliminated the allergies that the animal-derived products sometimes caused.

In the early 1980s, Eli Lilly produced Humulin, the first biosynthetic (made in Escherichia coli, hence the term, “bio”) human insulin.

This technology eventually “allowed for the alteration of specific amino acids in the sequence of the insulin protein to make insulin analogs [synthetic versions grown in E. coli and genetically altered for various properties] that act faster, or more slowly, than normal human insulin. By using the slow- and fast-acting insulins in combination, a patient can control their blood sugar levels with a much greater degree of finesse and precision,” Dr. Hall explained.

Today, a whole range of insulins are available, including ultra–rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, long-acting, ultra–long-acting, and even inhaled insulin, although the latter is expensive, has been associated with side effects, and is less commonly used, according to Dr. Stephens.

Oral insulin formulations are even in the early stages of development, with candidate drugs by Generex and from the Oralis project.

“With insulin therapy, we try to reproduce the normal physiology of the healthy body and pancreas,” Dr. Stephens explained.

Insulin analogs are only made by three companies (Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi), and they are generally much more expensive than nonanalog human insulin. In the United Kingdom through the NHS, they cost twice as much.

In the United States today, one of the biggest barriers to proper care of type 1 diabetes is the cost of insulin, which can limit access. With the market controlled by these three large companies, the average cost of a unit of insulin in the United States, according to RAND research, was $98.17 in January 2021, compared with $7.52 in the United Kingdom and $12.00 in Canada.

Several U.S. states have enacted legislation capping insulin copayments to at, or under, $100 a month. But the federal Build Back Better Framework Act – which would cap copayments for insulin at $35 – currently hangs in the balance.

Alongside these moves, in 2020 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first interchangeable biosimilar insulin for type 1 diabetes (and insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes) in children and adults, called Semglee (Mylan Pharmaceuticals).

Biosimilars (essentially generic versions of branded insulins) are expected to be less expensive than branded analogs, but the indications so far are that they will only be around 20% cheaper.

“I totally fail to understand how the richest country in the world still has a debate about price caps, and we are looking at biosimilar markets to change the debate. This makes no sense to me at all,” stressed Dr. Kar. “For lifesaving drugs, they should be funded by the state.”

Insulin also remains unaffordable for many in numerous low- and middle-income countries, where most patients pay out-of-pocket for medicines. Globally, there are estimated to be around 30 million people who need insulin but cannot afford it.

How near to a cure in the coming decades?

Looking ahead to the coming years, if not the next 100, Dr. Stephens highlighted two important aspects of care.

First, the use of a CGM device in combination with an insulin pump (also known as a closed-loop system or artificial pancreas), where the CGM effectively tells the insulin pump how much insulin to automatically dispense, should revolutionize care.

A number of such closed-loop systems have recently been approved in both the United States, including systems from Medtronic and Omnipod, and Europe.

“I wear one of these and it’s been a life changer for me, but it doesn’t suit everyone because the technology can be cumbersome, but with time, hopefully things will become smaller and more accurate in insulin delivery,” Dr. Stephens added.

The second advance of interest is the development and transplantation of cells that produce insulin.

Dr. Stephens explained that someone living with type 1 diabetes has a lot to think about, not least, doing the math related to insulin requirement. “If we just had cells from a pancreas that could be transplanted and would do that for us, then it would be a total game changer.”

To date, Vertex Pharmaceuticals has successfully treated one patient – who had lived with type 1 diabetes for about 40 years and had recurrent episodes of severe hypoglycemia – with an infusion of stem cell–derived differentiated islet cells into his liver. The procedure resulted in near reversal of type 1 diabetes, with his insulin dose reduced from 34 to 3 units, and his hemoglobin A1c falling from 8.6% to 7.2%.

And although the patient, Brian Shelton, still needs to take immunosuppressive agents to prevent rejection of the stem cell–derived islets, “it’s a whole new life,” he recently told the New York Times.

Another company called ViaCyte is also working on a similar approach.

Whether this is a cure for type 1 diabetes is still debatable, said Anne Peters, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Is it true? In a word, no. But we are part of the way there, which is much closer than we were 6 months ago.”

There are also ongoing clinical trials of therapeutic interventions to prevent or delay the trajectory from presymptomatic to clinical type 1 diabetes. The most advanced is the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab (Tzield, Provention Bio), which was rejected by the FDA in July 2021, but has since been refiled. The company expects to hear from the agency by the end of March 2022 as to whether the resubmission has been accepted.

Diabetes specialist nurses/educators keep it human

Dr. Hall said he concurs with the late eminent U.K. diabetes specialist Robert Tattersall’s observation on what he considers one of the most important advances in the management and treatment of type 1 diabetes: the human touch.

Referring to Dr. Tattersall’s book, “Diabetes: A Biography,” Dr. Hall quoted: “If asked what innovation had made the most difference to their lives in the 1980s, patients with type 1 diabetes in England would unhesitatingly have chosen not human insulin, but the spread of diabetes specialist nurses ... these people (mainly women) did more in the last two decades of the 20th century to improve the standard of diabetes care than any other innovation or drug.”

In the United States, diabetes specialist nurses were called diabetes educators until recently, when the name changed to certified diabetes care and education specialist.

“Above all, they have humanized the service and given the patient a say in the otherwise unequal relationship with all-powerful doctors,” concluded Dr. Hall, again quoting Dr. Tattersall.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series commemorating the 100-year anniversary of the first use of insulin in humans. Part 1 of this series examined the rivalry behind the discovery and use of insulin.

One hundred years ago, teenager Leonard Thompson was the first patient with type 1 diabetes to be successfully treated with insulin, granting him a reprieve from what was a certain death sentence at the time.

Since then, research has gathered pace. In the century since insulin’s discovery and first use, recombinant DNA technology has allowed for the engineering of the insulin molecule, providing numerous short- and long-acting analog versions. At the same time, technological leaps in automated insulin delivery and monitoring of blood glucose ensure more time with glucose in range and fewer life-threatening complications for those with type 1 diabetes fortunate enough to have access to the technology.

In spite of these advancements, there is still scope for further evolution of disease management, with the holy grail being the transplant of stem cell–derived islet cells capable of making insulin, ideally encased in some kind of protective device so that immunosuppression is not required.

Indeed, it is not unreasonable to “hope that type 1 diabetes will be a curable disease in the next 100 years,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist who has type 1 diabetes and practices in Portland, Ore.

Type 1 diabetes: The past 100 years

The epidemiology of type 1 diabetes has shifted considerably since 1922. A century ago, given that average life expectancy in the United States was around 54 years, it was pretty much the only type of diabetes that doctors encountered. “There was some type 2 diabetes about in heavier people, but the focus was on type 1 diabetes,” noted Dr. Stephens.

Originally called juvenile diabetes because it was thought to only occur in children, “now 50% of people are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes ... over [the age of] 20,” explained Dr. Stephens.

In the United States, around 1.4 million adults 20 years and older, and 187,000 children younger than 20, have the disease, according to data from the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This total represents an increase of nearly 30% from 2017.

Over the years, theories as to the cause, or trigger, for type 1 diabetes “have included cow’s milk and [viral] infections,” said Dr. Stephens. “Most likely, there’s a genetic predisposition and some type of exposure, which creates the perfect storm to trigger disease.”

There are hints that COVID-19 might be precipitating type 1 diabetes in some people. Recently, the CDC found SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with an increased risk for diabetes (all types) among youth, but not other acute respiratory infections. And two further studies from different parts of the world have recently identified an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but the reasons remain unclear.

The global CoviDiab registry has also been established to collect data on patients with COVID-19–related diabetes.

The million-dollar question: Is COVID-19 itself is propagating type 1 diabetes or unmasking a predisposition to the disease sooner? The latter might be associated with a lower type 1 diabetes rate in the future, said Partha Kar, MBBS, OBE, national specialty advisor, diabetes, for National Health Service England.

“Right now, we don’t know the answer. Whichever way you look at it, it is likely there will be a rise in cases, and in countries where insulin is not freely available, healthcare systems need to have supply ready because insulin is lifesaving in type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Kar emphasized.

CGMs and automated insulin delivery: A ‘godsend’

A huge change has also been seen, most notably in the past 15 to 20 years, in the technological advancements that can help those with type 1 diabetes live an easier life.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated ways of delivering insulin, such as smart pens and insulin pumps, have made the daily life of a person with type 1 diabetes in the Western world considerably more comfortable.

CGMs provide a constant stream of data to an app, often wirelessly in sync with the insulin pump. However, on a global level, they are only available to a lucky few.

In England, pending National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) approval, any CGM should be available to all eligible patients with type 1 diabetes within the NHS from April 2022, Dr. Kar pointed out. In the United States, CGMs are often unaffordable and access is mostly dependent on a person’s health insurance.

Kersten Hall, PhD, a scientist and U.K.-based medical historian who recently wrote a book, “Insulin, the Crooked Timber” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2022) uncovering the lesser-known story behind the discovery of insulin, was diagnosed with adult-onset type 1 diabetes at the age of 41. Dr. Hall had always found the finger-prick blood glucose test to be a chore but now has a CGM.

“It’s a total game changer for me: a godsend. I can’t sing its praises enough,” he said. “All it involves is the swipe of the phone and this provides a reading which tells me if my glucose is too low, so I eat something, or too high, so I might [go for] a run.”

Brewing insulin at scale

As described by Dr. Hall in his book, the journey from treating Mr. Thompson in 1922 to treating the masses began when biochemist James Collip, MD, PhD, discovered a means of purifying the animal pancreas extracts used to treat the teenager.

But production at scale presented a further challenge. This was overcome in 1924 when Eli Lilly drew on a technique used in the beer brewing process – where pH guides bitterness – to purify and manufacture large amounts of insulin.

By 1936, a range of slower-acting cattle and pig-derived insulins, the first produced by Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals, were developed.

However, it took 8,000 lb (approximately 3,600 kg) of pancreas glands from 23,500 animals to make 1 lb (0.5 kg) of insulin, so a more efficient process was badly needed.

Dr. Hall, who is a molecular biologist as well as an author, explains that the use of recombinant DNA technology to produce human insulin, as done by Genentech in the late 70s, was a key development in the story of modern insulin products. Genentech then provided synthetic human insulin for Eli Lilly to conduct clinical trials.

Human insulin most closely resembles porcine insulin structure and function, differing by only one amino acid, while human insulin differs from bovine insulin by three amino acid residues. This synthetic human insulin eliminated the allergies that the animal-derived products sometimes caused.

In the early 1980s, Eli Lilly produced Humulin, the first biosynthetic (made in Escherichia coli, hence the term, “bio”) human insulin.

This technology eventually “allowed for the alteration of specific amino acids in the sequence of the insulin protein to make insulin analogs [synthetic versions grown in E. coli and genetically altered for various properties] that act faster, or more slowly, than normal human insulin. By using the slow- and fast-acting insulins in combination, a patient can control their blood sugar levels with a much greater degree of finesse and precision,” Dr. Hall explained.

Today, a whole range of insulins are available, including ultra–rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, long-acting, ultra–long-acting, and even inhaled insulin, although the latter is expensive, has been associated with side effects, and is less commonly used, according to Dr. Stephens.

Oral insulin formulations are even in the early stages of development, with candidate drugs by Generex and from the Oralis project.

“With insulin therapy, we try to reproduce the normal physiology of the healthy body and pancreas,” Dr. Stephens explained.

Insulin analogs are only made by three companies (Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi), and they are generally much more expensive than nonanalog human insulin. In the United Kingdom through the NHS, they cost twice as much.

In the United States today, one of the biggest barriers to proper care of type 1 diabetes is the cost of insulin, which can limit access. With the market controlled by these three large companies, the average cost of a unit of insulin in the United States, according to RAND research, was $98.17 in January 2021, compared with $7.52 in the United Kingdom and $12.00 in Canada.

Several U.S. states have enacted legislation capping insulin copayments to at, or under, $100 a month. But the federal Build Back Better Framework Act – which would cap copayments for insulin at $35 – currently hangs in the balance.

Alongside these moves, in 2020 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first interchangeable biosimilar insulin for type 1 diabetes (and insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes) in children and adults, called Semglee (Mylan Pharmaceuticals).

Biosimilars (essentially generic versions of branded insulins) are expected to be less expensive than branded analogs, but the indications so far are that they will only be around 20% cheaper.

“I totally fail to understand how the richest country in the world still has a debate about price caps, and we are looking at biosimilar markets to change the debate. This makes no sense to me at all,” stressed Dr. Kar. “For lifesaving drugs, they should be funded by the state.”

Insulin also remains unaffordable for many in numerous low- and middle-income countries, where most patients pay out-of-pocket for medicines. Globally, there are estimated to be around 30 million people who need insulin but cannot afford it.

How near to a cure in the coming decades?

Looking ahead to the coming years, if not the next 100, Dr. Stephens highlighted two important aspects of care.

First, the use of a CGM device in combination with an insulin pump (also known as a closed-loop system or artificial pancreas), where the CGM effectively tells the insulin pump how much insulin to automatically dispense, should revolutionize care.

A number of such closed-loop systems have recently been approved in both the United States, including systems from Medtronic and Omnipod, and Europe.

“I wear one of these and it’s been a life changer for me, but it doesn’t suit everyone because the technology can be cumbersome, but with time, hopefully things will become smaller and more accurate in insulin delivery,” Dr. Stephens added.

The second advance of interest is the development and transplantation of cells that produce insulin.

Dr. Stephens explained that someone living with type 1 diabetes has a lot to think about, not least, doing the math related to insulin requirement. “If we just had cells from a pancreas that could be transplanted and would do that for us, then it would be a total game changer.”

To date, Vertex Pharmaceuticals has successfully treated one patient – who had lived with type 1 diabetes for about 40 years and had recurrent episodes of severe hypoglycemia – with an infusion of stem cell–derived differentiated islet cells into his liver. The procedure resulted in near reversal of type 1 diabetes, with his insulin dose reduced from 34 to 3 units, and his hemoglobin A1c falling from 8.6% to 7.2%.

And although the patient, Brian Shelton, still needs to take immunosuppressive agents to prevent rejection of the stem cell–derived islets, “it’s a whole new life,” he recently told the New York Times.

Another company called ViaCyte is also working on a similar approach.

Whether this is a cure for type 1 diabetes is still debatable, said Anne Peters, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Is it true? In a word, no. But we are part of the way there, which is much closer than we were 6 months ago.”

There are also ongoing clinical trials of therapeutic interventions to prevent or delay the trajectory from presymptomatic to clinical type 1 diabetes. The most advanced is the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab (Tzield, Provention Bio), which was rejected by the FDA in July 2021, but has since been refiled. The company expects to hear from the agency by the end of March 2022 as to whether the resubmission has been accepted.

Diabetes specialist nurses/educators keep it human

Dr. Hall said he concurs with the late eminent U.K. diabetes specialist Robert Tattersall’s observation on what he considers one of the most important advances in the management and treatment of type 1 diabetes: the human touch.

Referring to Dr. Tattersall’s book, “Diabetes: A Biography,” Dr. Hall quoted: “If asked what innovation had made the most difference to their lives in the 1980s, patients with type 1 diabetes in England would unhesitatingly have chosen not human insulin, but the spread of diabetes specialist nurses ... these people (mainly women) did more in the last two decades of the 20th century to improve the standard of diabetes care than any other innovation or drug.”

In the United States, diabetes specialist nurses were called diabetes educators until recently, when the name changed to certified diabetes care and education specialist.

“Above all, they have humanized the service and given the patient a say in the otherwise unequal relationship with all-powerful doctors,” concluded Dr. Hall, again quoting Dr. Tattersall.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series commemorating the 100-year anniversary of the first use of insulin in humans. Part 1 of this series examined the rivalry behind the discovery and use of insulin.

One hundred years ago, teenager Leonard Thompson was the first patient with type 1 diabetes to be successfully treated with insulin, granting him a reprieve from what was a certain death sentence at the time.

Since then, research has gathered pace. In the century since insulin’s discovery and first use, recombinant DNA technology has allowed for the engineering of the insulin molecule, providing numerous short- and long-acting analog versions. At the same time, technological leaps in automated insulin delivery and monitoring of blood glucose ensure more time with glucose in range and fewer life-threatening complications for those with type 1 diabetes fortunate enough to have access to the technology.

In spite of these advancements, there is still scope for further evolution of disease management, with the holy grail being the transplant of stem cell–derived islet cells capable of making insulin, ideally encased in some kind of protective device so that immunosuppression is not required.

Indeed, it is not unreasonable to “hope that type 1 diabetes will be a curable disease in the next 100 years,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist who has type 1 diabetes and practices in Portland, Ore.

Type 1 diabetes: The past 100 years

The epidemiology of type 1 diabetes has shifted considerably since 1922. A century ago, given that average life expectancy in the United States was around 54 years, it was pretty much the only type of diabetes that doctors encountered. “There was some type 2 diabetes about in heavier people, but the focus was on type 1 diabetes,” noted Dr. Stephens.

Originally called juvenile diabetes because it was thought to only occur in children, “now 50% of people are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes ... over [the age of] 20,” explained Dr. Stephens.

In the United States, around 1.4 million adults 20 years and older, and 187,000 children younger than 20, have the disease, according to data from the National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This total represents an increase of nearly 30% from 2017.

Over the years, theories as to the cause, or trigger, for type 1 diabetes “have included cow’s milk and [viral] infections,” said Dr. Stephens. “Most likely, there’s a genetic predisposition and some type of exposure, which creates the perfect storm to trigger disease.”

There are hints that COVID-19 might be precipitating type 1 diabetes in some people. Recently, the CDC found SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with an increased risk for diabetes (all types) among youth, but not other acute respiratory infections. And two further studies from different parts of the world have recently identified an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but the reasons remain unclear.

The global CoviDiab registry has also been established to collect data on patients with COVID-19–related diabetes.

The million-dollar question: Is COVID-19 itself is propagating type 1 diabetes or unmasking a predisposition to the disease sooner? The latter might be associated with a lower type 1 diabetes rate in the future, said Partha Kar, MBBS, OBE, national specialty advisor, diabetes, for National Health Service England.

“Right now, we don’t know the answer. Whichever way you look at it, it is likely there will be a rise in cases, and in countries where insulin is not freely available, healthcare systems need to have supply ready because insulin is lifesaving in type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Kar emphasized.

CGMs and automated insulin delivery: A ‘godsend’

A huge change has also been seen, most notably in the past 15 to 20 years, in the technological advancements that can help those with type 1 diabetes live an easier life.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated ways of delivering insulin, such as smart pens and insulin pumps, have made the daily life of a person with type 1 diabetes in the Western world considerably more comfortable.

CGMs provide a constant stream of data to an app, often wirelessly in sync with the insulin pump. However, on a global level, they are only available to a lucky few.

In England, pending National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) approval, any CGM should be available to all eligible patients with type 1 diabetes within the NHS from April 2022, Dr. Kar pointed out. In the United States, CGMs are often unaffordable and access is mostly dependent on a person’s health insurance.

Kersten Hall, PhD, a scientist and U.K.-based medical historian who recently wrote a book, “Insulin, the Crooked Timber” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2022) uncovering the lesser-known story behind the discovery of insulin, was diagnosed with adult-onset type 1 diabetes at the age of 41. Dr. Hall had always found the finger-prick blood glucose test to be a chore but now has a CGM.

“It’s a total game changer for me: a godsend. I can’t sing its praises enough,” he said. “All it involves is the swipe of the phone and this provides a reading which tells me if my glucose is too low, so I eat something, or too high, so I might [go for] a run.”

Brewing insulin at scale

As described by Dr. Hall in his book, the journey from treating Mr. Thompson in 1922 to treating the masses began when biochemist James Collip, MD, PhD, discovered a means of purifying the animal pancreas extracts used to treat the teenager.

But production at scale presented a further challenge. This was overcome in 1924 when Eli Lilly drew on a technique used in the beer brewing process – where pH guides bitterness – to purify and manufacture large amounts of insulin.

By 1936, a range of slower-acting cattle and pig-derived insulins, the first produced by Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals, were developed.

However, it took 8,000 lb (approximately 3,600 kg) of pancreas glands from 23,500 animals to make 1 lb (0.5 kg) of insulin, so a more efficient process was badly needed.

Dr. Hall, who is a molecular biologist as well as an author, explains that the use of recombinant DNA technology to produce human insulin, as done by Genentech in the late 70s, was a key development in the story of modern insulin products. Genentech then provided synthetic human insulin for Eli Lilly to conduct clinical trials.

Human insulin most closely resembles porcine insulin structure and function, differing by only one amino acid, while human insulin differs from bovine insulin by three amino acid residues. This synthetic human insulin eliminated the allergies that the animal-derived products sometimes caused.

In the early 1980s, Eli Lilly produced Humulin, the first biosynthetic (made in Escherichia coli, hence the term, “bio”) human insulin.

This technology eventually “allowed for the alteration of specific amino acids in the sequence of the insulin protein to make insulin analogs [synthetic versions grown in E. coli and genetically altered for various properties] that act faster, or more slowly, than normal human insulin. By using the slow- and fast-acting insulins in combination, a patient can control their blood sugar levels with a much greater degree of finesse and precision,” Dr. Hall explained.

Today, a whole range of insulins are available, including ultra–rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, long-acting, ultra–long-acting, and even inhaled insulin, although the latter is expensive, has been associated with side effects, and is less commonly used, according to Dr. Stephens.

Oral insulin formulations are even in the early stages of development, with candidate drugs by Generex and from the Oralis project.

“With insulin therapy, we try to reproduce the normal physiology of the healthy body and pancreas,” Dr. Stephens explained.

Insulin analogs are only made by three companies (Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi), and they are generally much more expensive than nonanalog human insulin. In the United Kingdom through the NHS, they cost twice as much.

In the United States today, one of the biggest barriers to proper care of type 1 diabetes is the cost of insulin, which can limit access. With the market controlled by these three large companies, the average cost of a unit of insulin in the United States, according to RAND research, was $98.17 in January 2021, compared with $7.52 in the United Kingdom and $12.00 in Canada.

Several U.S. states have enacted legislation capping insulin copayments to at, or under, $100 a month. But the federal Build Back Better Framework Act – which would cap copayments for insulin at $35 – currently hangs in the balance.

Alongside these moves, in 2020 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first interchangeable biosimilar insulin for type 1 diabetes (and insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes) in children and adults, called Semglee (Mylan Pharmaceuticals).

Biosimilars (essentially generic versions of branded insulins) are expected to be less expensive than branded analogs, but the indications so far are that they will only be around 20% cheaper.

“I totally fail to understand how the richest country in the world still has a debate about price caps, and we are looking at biosimilar markets to change the debate. This makes no sense to me at all,” stressed Dr. Kar. “For lifesaving drugs, they should be funded by the state.”

Insulin also remains unaffordable for many in numerous low- and middle-income countries, where most patients pay out-of-pocket for medicines. Globally, there are estimated to be around 30 million people who need insulin but cannot afford it.

How near to a cure in the coming decades?

Looking ahead to the coming years, if not the next 100, Dr. Stephens highlighted two important aspects of care.

First, the use of a CGM device in combination with an insulin pump (also known as a closed-loop system or artificial pancreas), where the CGM effectively tells the insulin pump how much insulin to automatically dispense, should revolutionize care.

A number of such closed-loop systems have recently been approved in both the United States, including systems from Medtronic and Omnipod, and Europe.

“I wear one of these and it’s been a life changer for me, but it doesn’t suit everyone because the technology can be cumbersome, but with time, hopefully things will become smaller and more accurate in insulin delivery,” Dr. Stephens added.

The second advance of interest is the development and transplantation of cells that produce insulin.

Dr. Stephens explained that someone living with type 1 diabetes has a lot to think about, not least, doing the math related to insulin requirement. “If we just had cells from a pancreas that could be transplanted and would do that for us, then it would be a total game changer.”

To date, Vertex Pharmaceuticals has successfully treated one patient – who had lived with type 1 diabetes for about 40 years and had recurrent episodes of severe hypoglycemia – with an infusion of stem cell–derived differentiated islet cells into his liver. The procedure resulted in near reversal of type 1 diabetes, with his insulin dose reduced from 34 to 3 units, and his hemoglobin A1c falling from 8.6% to 7.2%.

And although the patient, Brian Shelton, still needs to take immunosuppressive agents to prevent rejection of the stem cell–derived islets, “it’s a whole new life,” he recently told the New York Times.

Another company called ViaCyte is also working on a similar approach.

Whether this is a cure for type 1 diabetes is still debatable, said Anne Peters, MD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “Is it true? In a word, no. But we are part of the way there, which is much closer than we were 6 months ago.”

There are also ongoing clinical trials of therapeutic interventions to prevent or delay the trajectory from presymptomatic to clinical type 1 diabetes. The most advanced is the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab (Tzield, Provention Bio), which was rejected by the FDA in July 2021, but has since been refiled. The company expects to hear from the agency by the end of March 2022 as to whether the resubmission has been accepted.

Diabetes specialist nurses/educators keep it human

Dr. Hall said he concurs with the late eminent U.K. diabetes specialist Robert Tattersall’s observation on what he considers one of the most important advances in the management and treatment of type 1 diabetes: the human touch.

Referring to Dr. Tattersall’s book, “Diabetes: A Biography,” Dr. Hall quoted: “If asked what innovation had made the most difference to their lives in the 1980s, patients with type 1 diabetes in England would unhesitatingly have chosen not human insulin, but the spread of diabetes specialist nurses ... these people (mainly women) did more in the last two decades of the 20th century to improve the standard of diabetes care than any other innovation or drug.”

In the United States, diabetes specialist nurses were called diabetes educators until recently, when the name changed to certified diabetes care and education specialist.

“Above all, they have humanized the service and given the patient a say in the otherwise unequal relationship with all-powerful doctors,” concluded Dr. Hall, again quoting Dr. Tattersall.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Death of pig heart transplant patient is more a beginning than an end

The genetically altered pig’s heart “worked like a rock star, beautifully functioning,” the surgeon who performed the pioneering Jan. 7 xenotransplant procedure said in a press statement on the death of the patient, David Bennett Sr.

“He wasn’t able to overcome what turned out to be devastating – the debilitation from his previous period of heart failure, which was extreme,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, clinical director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Representatives of the institution aren’t offering many details on the cause of Mr. Bennett’s death on March 8, 60 days after his operation, but said they will elaborate when their findings are formally published. But their comments seem to downplay the unique nature of the implanted heart itself as a culprit and instead implicate the patient’s diminished overall clinical condition and what grew into an ongoing battle with infections.

The 57-year-old Bennett, bedridden with end-stage heart failure, judged a poor candidate for a ventricular assist device, and on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), reportedly was offered the extraordinary surgery after being turned down for a conventional transplant at several major centers.

“Until day 45 or 50, he was doing very well,” Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, the xenotransplantation program’s scientific director, observed in the statement. But infections soon took advantage of his hobbled immune system.

Given his “preexisting condition and how frail his body was,” Dr. Mohiuddin said, “we were having difficulty maintaining a balance between his immunosuppression and controlling his infection.” Mr. Bennett went into multiple organ failure and “I think that resulted in his passing away.”

Beyond wildest dreams

The surgeons confidently framed Mr. Bennett’s experience as a milestone for heart xenotransplantation. “The demonstration that it was possible, beyond the wildest dreams of most people in the field, even, at this point – that we were able to take a genetically engineered organ and watch it function flawlessly for 9 weeks – is pretty positive in terms of the potential of this therapy,” Dr. Griffith said.

But enough questions linger that others were more circumspect, even as they praised the accomplishment. “There’s no question that this is a historic event,” Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, of Harvard Medical School, and director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

Still, “I don’t think we should just conclude that it was the patient’s frailty or death from infection,” Dr. Mehra said. With so few details available, “I would be very careful in prematurely concluding that the problem did not reside with the heart but with the patient. We cannot be sure.”

For example, he noted, “6 to 8 weeks is right around the time when some cardiac complications, like accelerated forms of vasculopathy, could become evident.” Immune-mediated cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a common cause of heart transplant failure.

Or, “it could as easily have been the fact that immunosuppression was modified at 6 to 7 weeks in response to potential infection, which could have led to a cardiac compromise,” Dr. Mehra said. “We just don’t know.”

“It’s really important that this be reported in a scientifically accurate way, because we will all learn from this,” Lori J. West, MD, DPhil, said in an interview.

Little seems to be known for sure about the actual cause of death, “but the fact there was not hyperacute rejection is itself a big step forward. And we know, at least from the limited information we have, that it did not occur,” observed Dr. West, who directs the Alberta Transplant Institute, Edmonton, and the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program. She is a professor of pediatrics with adjunct positions in the departments of surgery and microbiology/immunology.

Dr. West also sees Mr. Bennett’s struggle with infections and adjustments to his unique immunosuppressive regimen, at least as characterized by his care team, as in line with the experience of many heart transplant recipients facing the same threat.

“We already walk this tightrope with every transplant patient,” she said. Typically, they’re put on a somewhat standardized immunosuppressant regimen, “and then we modify it a bit, either increasing or decreasing it, depending on the posttransplant course.” The regimen can become especially intense in response to new signs of rejection, “and you know that that’s going to have an impact on susceptibility to all kinds of infections.”

Full circle

The porcine heart was protected along two fronts against assault from Mr. Bennett’s immune system and other inhospitable aspects of his physiology, either of which could also have been obstacles to success: Genetic modification (Revivicor) of the pig that provided the heart, and a singularly aggressive antirejection drug regimen for the patient.

The knockout of three genes targeting specific porcine cell-surface carbohydrates that provoke a strong human antibody response reportedly averted a hyperacute rejection response that would have caused the graft to fail almost immediately.

Other genetic manipulations, some using CRISPR technology, silenced genes encoded for porcine endogenous retroviruses. Others were aimed at controlling myocardial growth and stemming graft microangiopathy.

Mr. Bennett himself was treated with powerful immunosuppressants, including an investigational anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (KPL-404, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals) that, according to UMSOM, inhibits a well-recognized pathway critical to B-cell proliferation, T-cell activation, and antibody production.

“I suspect the patient may not have had rejection, but unfortunately, that intense immunosuppression really set him up – even if he had been half that age – for a very difficult time,” David A. Baran, MD, a cardiologist from Sentara Advanced Heart Failure Center, Norfolk, Va., who studies transplant immunology, said in an interview.

“This is in some ways like the original heart transplant in 1967, when the ability to do the surgery evolved before understanding of the immunosuppression needed. Four or 5 years later, heart transplantation almost died out, before the development of better immunosuppressants like cyclosporine and later tacrolimus,” Dr. Baran said.

“The current age, when we use less immunosuppression than ever, is based on 30 years of progressive success,” he noted. This landmark xenotransplantation “basically turns back the clock to a time when the intensity of immunosuppression by definition had to be extremely high, because we really didn’t know what to expect.”

Emerging role of xeno-organs

Xenotransplantation has been touted as potential strategy for expanding the pool of organs available for transplantation. Mr. Bennett’s “breakthrough surgery” takes the world “one step closer to solving the organ shortage crisis,” his surgeon, Dr. Griffith, announced soon after the procedure. “There are simply not enough donor human hearts available to meet the long list of potential recipients.”

But it’s not the only proposed approach. Measures could be taken, for example, to make more efficient use of the human organs that become available, partly by opening the field to additional less-than-ideal hearts and loosening regulatory mandates for projected graft survival.

“Every year, more than two-thirds of donor organs in the United States are discarded. So it’s not actually that we don’t have enough organs, it’s that we don’t have enough organs that people are willing to take,” Dr. Baran said. Still, it’s important to pursue all promising avenues, and “the genetic manipulation pathway is remarkable.”

But “honestly, organs such as kidneys probably make the most sense” for early study of xenotransplantation from pigs, he said. “The waiting list for kidneys is also very long, but if the kidney graft were to fail, the patient wouldn’t die. It would allow us to work out the immunosuppression without putting patients’ lives at risk.”