User login

From neuroplasticity to psychoplasticity: Psilocybin may reverse personality disorders and political fanaticism

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

More on neurotransmitters

The series “Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: A hypothesis” (Part 1:

The presentation of abnormal neurotransmission may occur along a continuum. For example, extreme dopamine deficiency can present as catatonia, moderate deficiency may present with inattention, normal activity permits adaptive functioning, and excitatory delirium and sudden death may be at the extreme end of dopaminergic excess.1

The amplitude, rate of change, and location of neurotransmitter dysfunction may determine which specialty takes the primary treatment role. Fatigue, pain, sleep difficulty, and emotional distress require clinicians to understand the whole patient, which is why health care professionals need cross training in psychiatry, and psychiatry recognizes multisystem pathology.

The recognition and treatment of substance use disorders requires an understanding of neurotransmitter symptoms, in terms of both acute drug effects and withdrawal. Fallows2 provides this information in an accessible chart. Discussions of neurotransmitters also have value in managing psychotropic medication withdrawal.3

Acetylcholine is another neurotransmitter of importance; it is essential to normal motor, cognitive, and emotional function. Extreme cholinergic deficiency or anticholinergic crisis has symptoms of pupillary dilation, psychosis, and delirium.4-6 The progressive decline seen in certain dementias is related in part to cholinergic deficit. Dominance of cholinergic activity is associated with depression and biomarkers such as increased rapid eye movement (REM) density, a measure of the frequency of rapid eye movements during REM sleep.7 Cholinergic excess or cholinergic crisis may present with symptoms of salivation, lacrimation, muscle weakness, delirium, or paralysis.8

The articles alluded to the interaction of neurotransmitter systems (eg, “dopamine blockade helps with endorphin suppression”). Isolating the effects of a single neurotransmitter is useful, but covariance of neurotransmitter activity also has diagnostic and treatment implications.9-11 Abnormalities in these interactions may be part of the causal process in fundamental cognitive functions.12 If endorphin suppression is insensitive to dopamine blockade, a relative endorphin excess may create symptoms. If acetylcholine changes are normally balanced by a relative increase in dopamine and norepinephrine, then a weak catecholamine response would fit the catecholamine-cholinergic balance hypothesis of depression. Neurotransmitter interactions are well worked out in the neurology of the basal ganglia but less clear in the frontal and limbic systems.13

Quantification has been applied in some areas of clinical care. Morphine equivalents are used to express opiate potency, and there are algorithms to summarize multiple medication effects on respiratory depression/overdose risk.14,15 Chlorpromazine equivalents were used to translate a range of antipsychotic potencies in the early days of antipsychotic treatment. Adverse effects and some treatment responses partially corresponded to the level of dopamine blockade, but not without noise. There is a wide range of variance as antipsychotic potency is assessed for clinical efficacy.16 We are still working on the array of medication potency and selectivity across neurotransmitter systems.17,18 For example, paroxetine is a potent serotonin reuptake blocker but less selective than citalopram, particularly antagonizing cholinergic muscarinic receptors.

The authors noted their hypothesis needs further elaboration and quantification as psychiatry moves from impressionistic practice to firmer science. Measurement of neurotransmitter activity is an area of intense research. Biomeasures have yet to add much value to the clinical practice of psychiatry, but we hope for progress. Functional neuroimaging with sophisticated algorithms is beginning to detail neocortical activity.19 CSF measurement of dopamine and serotonin metabolites seem to correlate with severe depression and suicidal behavior. Noninvasive, wearable technologies to measure galvanic skin response, oxygenation, and neurotransmitter metabolic products may add to neuro-transmitter-based assessment and treatment.

Neurotransmitters are one aspect of brain function. Other processes, such as hormonal neuromodulation20 and ion channels, may be over- or underactive. Channelopathies are of particular interest in cardiology and neurology but are also notable in pain and emotional disorders.21-26 Voltage-gated sodium channels are thought to be involved in general anesthesia.27 Adverse effects of some psychotropic medications are best understood as ion channel dysfunction.28 Using the strategy of this hypothesis applied to activation or inactivation of sodium, potassium, and calcium channels can guide useful diagnostic and treatment ideas for further study.

Mark C. Chandler, MD

Triangle Neuropsychiatry

Durham, North Carolina

Disclosures

The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in his letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Mash DC. Excited delirium and sudden death: a syndromal disorder at the extreme end of the neuropsychiatric continuum. Front Physiol. 2016;7:435.

2. Fallows Z. MIT MedLinks. Accessed August 8, 2022. http://web.mit.edu/zakf/www/drugchart/drugchart11.html

3. Groot PC, van Os J. How user knowledge of psychotropic drug withdrawal resulted in the development of person-specific tapering medication. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320932452. doi:10.1177/2045125320932452

4. Picciotto MR, Higley MJ, Mineur YS. Acetylcholine as a neuromodulator: cholinergic signaling shapes nervous system function and behavior. Neuron. 2012;76(1):116-129.

5. Nair VP, Hunter JM. Anticholinesterases and anticholinergic drugs. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2004;4(5):164-168.

6. Dawson AH, Buckley NA. Pharmacological management of anticholinergic delirium--theory, evidence and practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(3):516-524.

7. Dulawa SC, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic regulation of mood: from basic and clinical studies to emerging therapeutics. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(5):694-709.

8. Adeyinka A, Kondamudi NP. Cholinergic Crisis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

9. El Mansari M, Guiard BP, Chernoloz O, et al. Relevance of norepinephrine-dopamine interactions in the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(3):e1-e17.

10. Esposito E. Serotonin-dopamine interaction as a focus of novel antidepressant drugs. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7(2):177-185.

11. Kringelbach ML, Cruzat J, Cabral J, et al. Dynamic coupling of whole-brain neuronal and neurotransmitter systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9566-9576.

12. Thiele A, Bellgrove MA. Neuromodulation of attention. Neuron. 2018;97(4):769-785.

13. Muñoz A, Lopez-Lopez A, Labandeira CM, et al. Interactions between the serotonergic and other neurotransmitter systems in the basal ganglia: role in Parkinson’s disease and adverse effects of L-DOPA. Front Neuroanat. 2020;14:26.

14. Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, et al. A synthesis of oral morphine equivalents (OME) for opioid utilisation studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(6):733-737.

15. Lo-Ciganic WH, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

16. Dewan MJ, Koss M. The clinical impact of reported variance in potency of antipsychotic agents. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(4):229-232.

17. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-667.

18. Hayasaka Y, Purgato M, Magni LR, et al. Dose equivalents of antidepressants: evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:179-184.

19. Hansen JY, Shafiei G, Markello RD, et al. Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex. bioRxiv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.28.466336

20. Hwang WJ, Lee TY, Kim NS, et al. The role of estrogen receptors and their signaling across psychiatric disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):373.

21. Lawrence JH, Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Ion channels: structure and function. Heart Dis Stroke. 1993;2(1):75-80.

22. Fedele F, Severino P, Bruno N, et al. Role of ion channels in coronary microcirculation: a review of the literature. Future Cardiol. 2013;9(6):897-905.

23. Kumar P, Kumar D, Jha SK, et al. Ion channels in neurological disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;103:97-136.

24. Quagliato LA, Nardi AE. The role of convergent ion channel pathways in microglial phenotypes: a systematic review of the implications for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):259.

25. Bianchi MT, Botzolakis EJ. Targeting ligand-gated ion channels in neurology and psychiatry: is pharmacological promiscuity an obstacle or an opportunity? BMC Pharmacol. 2010;10:3.

26. Imbrici P, Camerino DC, Tricarico D. Major channels involved in neuropsychiatric disorders and therapeutic perspectives. Front Genet. 2013;4:76.

27. Xiao J, Chen Z, Yu B. A potential mechanism of sodium channel mediating the general anesthesia induced by propofol. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:593050. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.593050

28. Kamei S, Sato N, Harayama Y, et al. Molecular analysis of potassium ion channel genes in sudden death cases among patients administered psychotropic drug therapy: are polymorphisms in LQT genes a potential risk factor? J Hum Genet. 2014;59(2):95-99.

The authors respond

Thank you for your thoughtful commentary. Our conceptual article was not designed to cover enough ground to be completely thorough. Everything you wrote adds to what we wanted to bring to the reader’s attention. The mechanisms of disease in psychiatry are numerous and still elusive, and the brain’s complexity is staggering. Our main goal was to point out possible correlations between specific symptoms and specific neurotransmitter activity. We had to oversimplify to make the article concise enough for publication. Neurotransmitter effects are based on their synthesis, storage, release, reuptake, and degradation. A receptor’s quantity and quality of function, inhibitors, inducers, and many other factors are involved in neurotransmitter performance. And, of course, there are additional fundamental neurotransmitters beyond the 6 we touched on. Our ability to sort through all of this is still rudimentary. You also reflect on the emerging methods to objectively measure neurotransmitter activity, which will eventually find their way to clinical practice and become invaluable. Still, we treat people, not tests or pictures, so diagnostic thinking based on clinical presentation will forever remain a cornerstone of dealing with individual patients.

We hope scientists and clinicians such as yourself will improve our concept and make it truly practical.

Dmitry M. Arbuck, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine

Indianapolis, Indiana

President and Medical Director

Indiana Polyclinic

Carmel, Indiana

José Miguel Salmerón, MD

Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Universidad del Valle School of Medicine/Hospital

Universitario del Valle

Cali, Colombia

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their response, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The series “Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: A hypothesis” (Part 1:

The presentation of abnormal neurotransmission may occur along a continuum. For example, extreme dopamine deficiency can present as catatonia, moderate deficiency may present with inattention, normal activity permits adaptive functioning, and excitatory delirium and sudden death may be at the extreme end of dopaminergic excess.1

The amplitude, rate of change, and location of neurotransmitter dysfunction may determine which specialty takes the primary treatment role. Fatigue, pain, sleep difficulty, and emotional distress require clinicians to understand the whole patient, which is why health care professionals need cross training in psychiatry, and psychiatry recognizes multisystem pathology.

The recognition and treatment of substance use disorders requires an understanding of neurotransmitter symptoms, in terms of both acute drug effects and withdrawal. Fallows2 provides this information in an accessible chart. Discussions of neurotransmitters also have value in managing psychotropic medication withdrawal.3

Acetylcholine is another neurotransmitter of importance; it is essential to normal motor, cognitive, and emotional function. Extreme cholinergic deficiency or anticholinergic crisis has symptoms of pupillary dilation, psychosis, and delirium.4-6 The progressive decline seen in certain dementias is related in part to cholinergic deficit. Dominance of cholinergic activity is associated with depression and biomarkers such as increased rapid eye movement (REM) density, a measure of the frequency of rapid eye movements during REM sleep.7 Cholinergic excess or cholinergic crisis may present with symptoms of salivation, lacrimation, muscle weakness, delirium, or paralysis.8

The articles alluded to the interaction of neurotransmitter systems (eg, “dopamine blockade helps with endorphin suppression”). Isolating the effects of a single neurotransmitter is useful, but covariance of neurotransmitter activity also has diagnostic and treatment implications.9-11 Abnormalities in these interactions may be part of the causal process in fundamental cognitive functions.12 If endorphin suppression is insensitive to dopamine blockade, a relative endorphin excess may create symptoms. If acetylcholine changes are normally balanced by a relative increase in dopamine and norepinephrine, then a weak catecholamine response would fit the catecholamine-cholinergic balance hypothesis of depression. Neurotransmitter interactions are well worked out in the neurology of the basal ganglia but less clear in the frontal and limbic systems.13

Quantification has been applied in some areas of clinical care. Morphine equivalents are used to express opiate potency, and there are algorithms to summarize multiple medication effects on respiratory depression/overdose risk.14,15 Chlorpromazine equivalents were used to translate a range of antipsychotic potencies in the early days of antipsychotic treatment. Adverse effects and some treatment responses partially corresponded to the level of dopamine blockade, but not without noise. There is a wide range of variance as antipsychotic potency is assessed for clinical efficacy.16 We are still working on the array of medication potency and selectivity across neurotransmitter systems.17,18 For example, paroxetine is a potent serotonin reuptake blocker but less selective than citalopram, particularly antagonizing cholinergic muscarinic receptors.

The authors noted their hypothesis needs further elaboration and quantification as psychiatry moves from impressionistic practice to firmer science. Measurement of neurotransmitter activity is an area of intense research. Biomeasures have yet to add much value to the clinical practice of psychiatry, but we hope for progress. Functional neuroimaging with sophisticated algorithms is beginning to detail neocortical activity.19 CSF measurement of dopamine and serotonin metabolites seem to correlate with severe depression and suicidal behavior. Noninvasive, wearable technologies to measure galvanic skin response, oxygenation, and neurotransmitter metabolic products may add to neuro-transmitter-based assessment and treatment.

Neurotransmitters are one aspect of brain function. Other processes, such as hormonal neuromodulation20 and ion channels, may be over- or underactive. Channelopathies are of particular interest in cardiology and neurology but are also notable in pain and emotional disorders.21-26 Voltage-gated sodium channels are thought to be involved in general anesthesia.27 Adverse effects of some psychotropic medications are best understood as ion channel dysfunction.28 Using the strategy of this hypothesis applied to activation or inactivation of sodium, potassium, and calcium channels can guide useful diagnostic and treatment ideas for further study.

Mark C. Chandler, MD

Triangle Neuropsychiatry

Durham, North Carolina

Disclosures

The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in his letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Mash DC. Excited delirium and sudden death: a syndromal disorder at the extreme end of the neuropsychiatric continuum. Front Physiol. 2016;7:435.

2. Fallows Z. MIT MedLinks. Accessed August 8, 2022. http://web.mit.edu/zakf/www/drugchart/drugchart11.html

3. Groot PC, van Os J. How user knowledge of psychotropic drug withdrawal resulted in the development of person-specific tapering medication. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320932452. doi:10.1177/2045125320932452

4. Picciotto MR, Higley MJ, Mineur YS. Acetylcholine as a neuromodulator: cholinergic signaling shapes nervous system function and behavior. Neuron. 2012;76(1):116-129.

5. Nair VP, Hunter JM. Anticholinesterases and anticholinergic drugs. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2004;4(5):164-168.

6. Dawson AH, Buckley NA. Pharmacological management of anticholinergic delirium--theory, evidence and practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(3):516-524.

7. Dulawa SC, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic regulation of mood: from basic and clinical studies to emerging therapeutics. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(5):694-709.

8. Adeyinka A, Kondamudi NP. Cholinergic Crisis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

9. El Mansari M, Guiard BP, Chernoloz O, et al. Relevance of norepinephrine-dopamine interactions in the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(3):e1-e17.

10. Esposito E. Serotonin-dopamine interaction as a focus of novel antidepressant drugs. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7(2):177-185.

11. Kringelbach ML, Cruzat J, Cabral J, et al. Dynamic coupling of whole-brain neuronal and neurotransmitter systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9566-9576.

12. Thiele A, Bellgrove MA. Neuromodulation of attention. Neuron. 2018;97(4):769-785.

13. Muñoz A, Lopez-Lopez A, Labandeira CM, et al. Interactions between the serotonergic and other neurotransmitter systems in the basal ganglia: role in Parkinson’s disease and adverse effects of L-DOPA. Front Neuroanat. 2020;14:26.

14. Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, et al. A synthesis of oral morphine equivalents (OME) for opioid utilisation studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(6):733-737.

15. Lo-Ciganic WH, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

16. Dewan MJ, Koss M. The clinical impact of reported variance in potency of antipsychotic agents. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(4):229-232.

17. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-667.

18. Hayasaka Y, Purgato M, Magni LR, et al. Dose equivalents of antidepressants: evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:179-184.

19. Hansen JY, Shafiei G, Markello RD, et al. Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex. bioRxiv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.28.466336

20. Hwang WJ, Lee TY, Kim NS, et al. The role of estrogen receptors and their signaling across psychiatric disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):373.

21. Lawrence JH, Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Ion channels: structure and function. Heart Dis Stroke. 1993;2(1):75-80.

22. Fedele F, Severino P, Bruno N, et al. Role of ion channels in coronary microcirculation: a review of the literature. Future Cardiol. 2013;9(6):897-905.

23. Kumar P, Kumar D, Jha SK, et al. Ion channels in neurological disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;103:97-136.

24. Quagliato LA, Nardi AE. The role of convergent ion channel pathways in microglial phenotypes: a systematic review of the implications for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):259.

25. Bianchi MT, Botzolakis EJ. Targeting ligand-gated ion channels in neurology and psychiatry: is pharmacological promiscuity an obstacle or an opportunity? BMC Pharmacol. 2010;10:3.

26. Imbrici P, Camerino DC, Tricarico D. Major channels involved in neuropsychiatric disorders and therapeutic perspectives. Front Genet. 2013;4:76.

27. Xiao J, Chen Z, Yu B. A potential mechanism of sodium channel mediating the general anesthesia induced by propofol. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:593050. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.593050

28. Kamei S, Sato N, Harayama Y, et al. Molecular analysis of potassium ion channel genes in sudden death cases among patients administered psychotropic drug therapy: are polymorphisms in LQT genes a potential risk factor? J Hum Genet. 2014;59(2):95-99.

The authors respond

Thank you for your thoughtful commentary. Our conceptual article was not designed to cover enough ground to be completely thorough. Everything you wrote adds to what we wanted to bring to the reader’s attention. The mechanisms of disease in psychiatry are numerous and still elusive, and the brain’s complexity is staggering. Our main goal was to point out possible correlations between specific symptoms and specific neurotransmitter activity. We had to oversimplify to make the article concise enough for publication. Neurotransmitter effects are based on their synthesis, storage, release, reuptake, and degradation. A receptor’s quantity and quality of function, inhibitors, inducers, and many other factors are involved in neurotransmitter performance. And, of course, there are additional fundamental neurotransmitters beyond the 6 we touched on. Our ability to sort through all of this is still rudimentary. You also reflect on the emerging methods to objectively measure neurotransmitter activity, which will eventually find their way to clinical practice and become invaluable. Still, we treat people, not tests or pictures, so diagnostic thinking based on clinical presentation will forever remain a cornerstone of dealing with individual patients.

We hope scientists and clinicians such as yourself will improve our concept and make it truly practical.

Dmitry M. Arbuck, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine

Indianapolis, Indiana

President and Medical Director

Indiana Polyclinic

Carmel, Indiana

José Miguel Salmerón, MD

Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Universidad del Valle School of Medicine/Hospital

Universitario del Valle

Cali, Colombia

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their response, or with manufacturers of competing products.

The series “Neurotransmitter-based diagnosis and treatment: A hypothesis” (Part 1:

The presentation of abnormal neurotransmission may occur along a continuum. For example, extreme dopamine deficiency can present as catatonia, moderate deficiency may present with inattention, normal activity permits adaptive functioning, and excitatory delirium and sudden death may be at the extreme end of dopaminergic excess.1

The amplitude, rate of change, and location of neurotransmitter dysfunction may determine which specialty takes the primary treatment role. Fatigue, pain, sleep difficulty, and emotional distress require clinicians to understand the whole patient, which is why health care professionals need cross training in psychiatry, and psychiatry recognizes multisystem pathology.

The recognition and treatment of substance use disorders requires an understanding of neurotransmitter symptoms, in terms of both acute drug effects and withdrawal. Fallows2 provides this information in an accessible chart. Discussions of neurotransmitters also have value in managing psychotropic medication withdrawal.3

Acetylcholine is another neurotransmitter of importance; it is essential to normal motor, cognitive, and emotional function. Extreme cholinergic deficiency or anticholinergic crisis has symptoms of pupillary dilation, psychosis, and delirium.4-6 The progressive decline seen in certain dementias is related in part to cholinergic deficit. Dominance of cholinergic activity is associated with depression and biomarkers such as increased rapid eye movement (REM) density, a measure of the frequency of rapid eye movements during REM sleep.7 Cholinergic excess or cholinergic crisis may present with symptoms of salivation, lacrimation, muscle weakness, delirium, or paralysis.8

The articles alluded to the interaction of neurotransmitter systems (eg, “dopamine blockade helps with endorphin suppression”). Isolating the effects of a single neurotransmitter is useful, but covariance of neurotransmitter activity also has diagnostic and treatment implications.9-11 Abnormalities in these interactions may be part of the causal process in fundamental cognitive functions.12 If endorphin suppression is insensitive to dopamine blockade, a relative endorphin excess may create symptoms. If acetylcholine changes are normally balanced by a relative increase in dopamine and norepinephrine, then a weak catecholamine response would fit the catecholamine-cholinergic balance hypothesis of depression. Neurotransmitter interactions are well worked out in the neurology of the basal ganglia but less clear in the frontal and limbic systems.13

Quantification has been applied in some areas of clinical care. Morphine equivalents are used to express opiate potency, and there are algorithms to summarize multiple medication effects on respiratory depression/overdose risk.14,15 Chlorpromazine equivalents were used to translate a range of antipsychotic potencies in the early days of antipsychotic treatment. Adverse effects and some treatment responses partially corresponded to the level of dopamine blockade, but not without noise. There is a wide range of variance as antipsychotic potency is assessed for clinical efficacy.16 We are still working on the array of medication potency and selectivity across neurotransmitter systems.17,18 For example, paroxetine is a potent serotonin reuptake blocker but less selective than citalopram, particularly antagonizing cholinergic muscarinic receptors.

The authors noted their hypothesis needs further elaboration and quantification as psychiatry moves from impressionistic practice to firmer science. Measurement of neurotransmitter activity is an area of intense research. Biomeasures have yet to add much value to the clinical practice of psychiatry, but we hope for progress. Functional neuroimaging with sophisticated algorithms is beginning to detail neocortical activity.19 CSF measurement of dopamine and serotonin metabolites seem to correlate with severe depression and suicidal behavior. Noninvasive, wearable technologies to measure galvanic skin response, oxygenation, and neurotransmitter metabolic products may add to neuro-transmitter-based assessment and treatment.

Neurotransmitters are one aspect of brain function. Other processes, such as hormonal neuromodulation20 and ion channels, may be over- or underactive. Channelopathies are of particular interest in cardiology and neurology but are also notable in pain and emotional disorders.21-26 Voltage-gated sodium channels are thought to be involved in general anesthesia.27 Adverse effects of some psychotropic medications are best understood as ion channel dysfunction.28 Using the strategy of this hypothesis applied to activation or inactivation of sodium, potassium, and calcium channels can guide useful diagnostic and treatment ideas for further study.

Mark C. Chandler, MD

Triangle Neuropsychiatry

Durham, North Carolina

Disclosures

The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in his letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Mash DC. Excited delirium and sudden death: a syndromal disorder at the extreme end of the neuropsychiatric continuum. Front Physiol. 2016;7:435.

2. Fallows Z. MIT MedLinks. Accessed August 8, 2022. http://web.mit.edu/zakf/www/drugchart/drugchart11.html

3. Groot PC, van Os J. How user knowledge of psychotropic drug withdrawal resulted in the development of person-specific tapering medication. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320932452. doi:10.1177/2045125320932452

4. Picciotto MR, Higley MJ, Mineur YS. Acetylcholine as a neuromodulator: cholinergic signaling shapes nervous system function and behavior. Neuron. 2012;76(1):116-129.

5. Nair VP, Hunter JM. Anticholinesterases and anticholinergic drugs. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2004;4(5):164-168.

6. Dawson AH, Buckley NA. Pharmacological management of anticholinergic delirium--theory, evidence and practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(3):516-524.

7. Dulawa SC, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic regulation of mood: from basic and clinical studies to emerging therapeutics. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(5):694-709.

8. Adeyinka A, Kondamudi NP. Cholinergic Crisis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

9. El Mansari M, Guiard BP, Chernoloz O, et al. Relevance of norepinephrine-dopamine interactions in the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(3):e1-e17.

10. Esposito E. Serotonin-dopamine interaction as a focus of novel antidepressant drugs. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7(2):177-185.

11. Kringelbach ML, Cruzat J, Cabral J, et al. Dynamic coupling of whole-brain neuronal and neurotransmitter systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9566-9576.

12. Thiele A, Bellgrove MA. Neuromodulation of attention. Neuron. 2018;97(4):769-785.

13. Muñoz A, Lopez-Lopez A, Labandeira CM, et al. Interactions between the serotonergic and other neurotransmitter systems in the basal ganglia: role in Parkinson’s disease and adverse effects of L-DOPA. Front Neuroanat. 2020;14:26.

14. Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, et al. A synthesis of oral morphine equivalents (OME) for opioid utilisation studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(6):733-737.

15. Lo-Ciganic WH, Huang JL, Zhang HH, et al. Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among Medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190968. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0968

16. Dewan MJ, Koss M. The clinical impact of reported variance in potency of antipsychotic agents. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(4):229-232.

17. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-667.

18. Hayasaka Y, Purgato M, Magni LR, et al. Dose equivalents of antidepressants: evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:179-184.

19. Hansen JY, Shafiei G, Markello RD, et al. Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex. bioRxiv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.28.466336

20. Hwang WJ, Lee TY, Kim NS, et al. The role of estrogen receptors and their signaling across psychiatric disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):373.

21. Lawrence JH, Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Ion channels: structure and function. Heart Dis Stroke. 1993;2(1):75-80.

22. Fedele F, Severino P, Bruno N, et al. Role of ion channels in coronary microcirculation: a review of the literature. Future Cardiol. 2013;9(6):897-905.

23. Kumar P, Kumar D, Jha SK, et al. Ion channels in neurological disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;103:97-136.

24. Quagliato LA, Nardi AE. The role of convergent ion channel pathways in microglial phenotypes: a systematic review of the implications for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):259.

25. Bianchi MT, Botzolakis EJ. Targeting ligand-gated ion channels in neurology and psychiatry: is pharmacological promiscuity an obstacle or an opportunity? BMC Pharmacol. 2010;10:3.

26. Imbrici P, Camerino DC, Tricarico D. Major channels involved in neuropsychiatric disorders and therapeutic perspectives. Front Genet. 2013;4:76.

27. Xiao J, Chen Z, Yu B. A potential mechanism of sodium channel mediating the general anesthesia induced by propofol. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:593050. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.593050

28. Kamei S, Sato N, Harayama Y, et al. Molecular analysis of potassium ion channel genes in sudden death cases among patients administered psychotropic drug therapy: are polymorphisms in LQT genes a potential risk factor? J Hum Genet. 2014;59(2):95-99.

The authors respond

Thank you for your thoughtful commentary. Our conceptual article was not designed to cover enough ground to be completely thorough. Everything you wrote adds to what we wanted to bring to the reader’s attention. The mechanisms of disease in psychiatry are numerous and still elusive, and the brain’s complexity is staggering. Our main goal was to point out possible correlations between specific symptoms and specific neurotransmitter activity. We had to oversimplify to make the article concise enough for publication. Neurotransmitter effects are based on their synthesis, storage, release, reuptake, and degradation. A receptor’s quantity and quality of function, inhibitors, inducers, and many other factors are involved in neurotransmitter performance. And, of course, there are additional fundamental neurotransmitters beyond the 6 we touched on. Our ability to sort through all of this is still rudimentary. You also reflect on the emerging methods to objectively measure neurotransmitter activity, which will eventually find their way to clinical practice and become invaluable. Still, we treat people, not tests or pictures, so diagnostic thinking based on clinical presentation will forever remain a cornerstone of dealing with individual patients.

We hope scientists and clinicians such as yourself will improve our concept and make it truly practical.

Dmitry M. Arbuck, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine

Indianapolis, Indiana

President and Medical Director

Indiana Polyclinic

Carmel, Indiana

José Miguel Salmerón, MD

Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Universidad del Valle School of Medicine/Hospital

Universitario del Valle

Cali, Colombia

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their response, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: Rare but serious

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

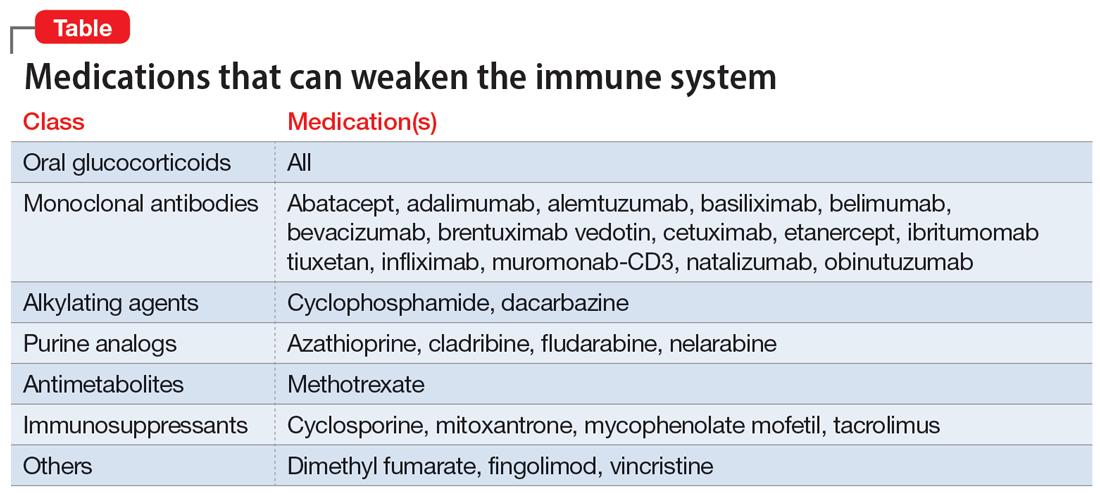

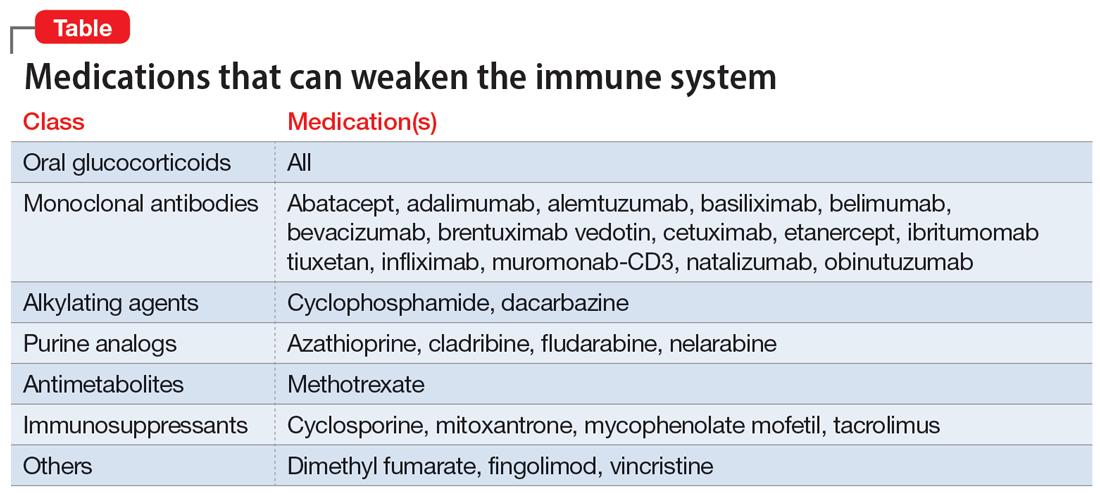

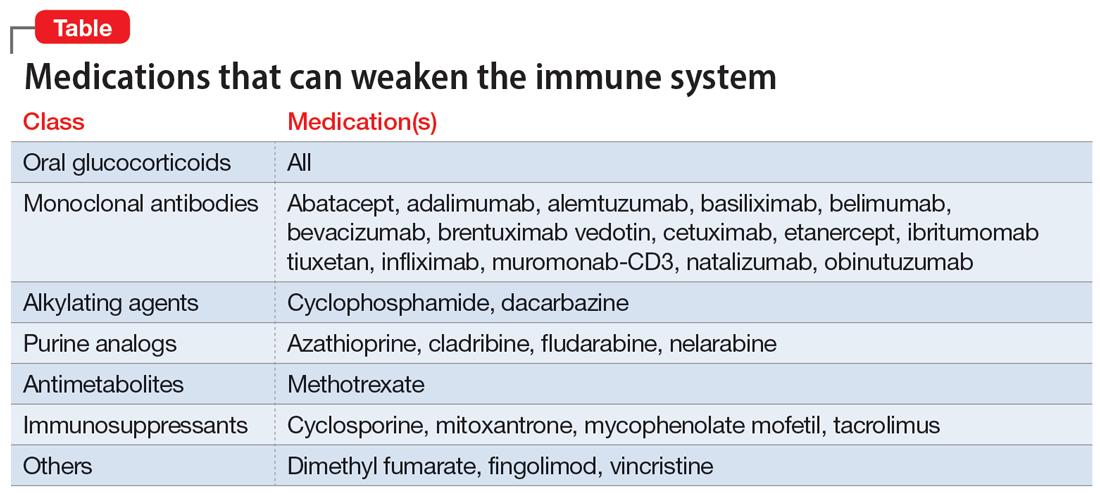

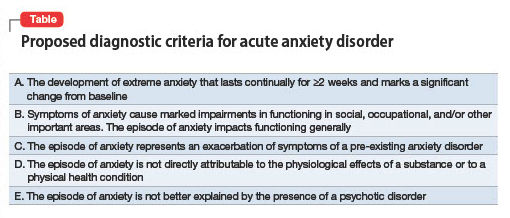

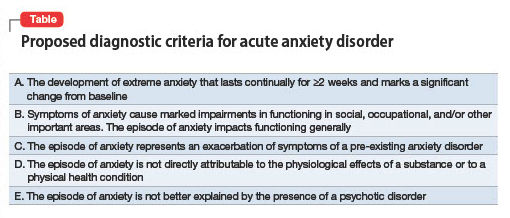

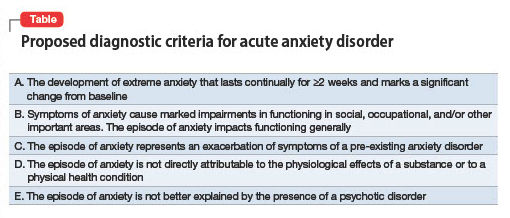

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED