User login

Outcomes After Prolonged ICU Stays in Postoperative Cardiac Surgery Patients

Prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, variably defined as > 48 h to > 14 days, are a known complication of cardiac surgery.1-8 Prolonged stays are associated with higher resource utilization and higher mortality.2,3,9-12 Although there are several cardiac surgery risk models that can be used preoperatively to identify patients at risk for prolonged ICU stay, factors that influence outcomes for patients who experience prolonged ICU stays are poorly understood.2,13-19 Little information is available to inform discussions between health care practitioners (HCPs) and patients throughout a prolonged ICU stay, especially those ≥ 7 days.

As cardiac surgical complexity, patient age, and preexisting comorbidities have increased over time, so has the need to provide patients and HCPs with data to inform decision making, enhance prognostication, and set realistic expectations at varying time intervals during prolonged ICU stay. The purpose of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term outcomes in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged ICU stays at relevant time intervals (7, 14, 21, and 28 days) and to determine factors that may predict a patient’s outcome after a prolonged ICU stay.

Methods

The University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent. We merged the University of Michigan Medical Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, which is updated periodically with late mortality, with elements of the electronic health record (EHR). Adult patients were included if they had cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan between January 2, 2001, and December 31, 2011. Late mortality was updated through December 1, 2014. Data are presented as frequency (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR) as appropriate. Bivariate comparisons between survivors and nonsurvivors were done with χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical data, Student t test for continuous normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous not normally distributed data. To determine factors associated with operative mortality (death within 30 days of surgery or hospital discharge, whichever occurred later), we used logistic regression with forward selection. All available factors were initially entered in the models.

Separate logistic models were created based on all data available at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Final models consisted of factors with statistically significant P values (< .05) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs that excluded 1. To determine factors associated with late mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazard model, which used data available at discharge and STS complications. As these complications did not include their timing, they could only be used in models created at discharge and not for days 7, 14, 21, and 28 models. Final models consisted of factors with P values < .05 and 95% CIs of the AORs or the hazard ratios (HRs) that excluded 1. As the EHR did not start recording data until January 2, 2004, and its capture of data remained incomplete for several years, rather than imputing these missing data or excluding these patients, we chose to create an extra categorical level for each factor to represent missing data. For continuous factors with missing data, we first converted the continuous data to terciles and the missing data became the fourth level.20,21

The discrimination of the logistic models were determined by the c-statistic and for the Cox proportional hazards model with the Harrell concordance index (C index). Time trends were assessed with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistics were calculated with SPSS versions 21-23 or SAS 9.4.

Results

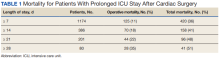

Of 8309 admissions to the ICU after cardiac surgery, 1174 (14%) had ICU stays ≥ 7 days, 386 (5%) ≥ 14 days, 201 (2%) ≥ 21 days, and 80 (0.9%) ≥ 28 days. The prolonged ICU study population was mostly male, White race, with a mean (SD) age of 62 (14) years. Patients had a variety of comorbidities, most notably 61% had hypertension and half had heart failure. Valve surgery (55%) was the most common procedure (n = 651). Twenty-nine percent required > 1 procedure (eAppendix 1).

The operative mortality

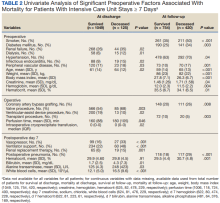

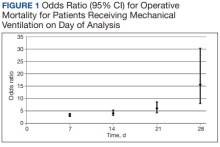

Using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for factors associated with mortality, we found that receiving mechanical ventilation on the day of analysis was associated with increased operative mortality with AOR increasing from 3.35 (95% CI, 2.82-3.98) for

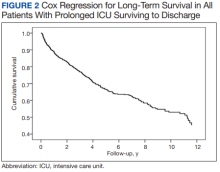

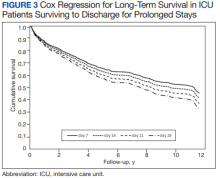

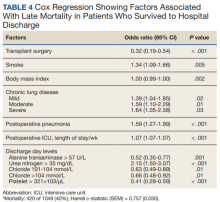

After multivariable Cox regression to adjust for confounders, we found that each postoperative week was associated with a 7% higher hazard of dying (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07-1.07; P < .001). Postoperative pneumonia was also associated with increased hazard of dying (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.27-1.99; P < .001),

Discussion

We found that operative mortality increased the longer the patient stayed in the ICU, ranging from 11% for ≥ 7 days to 35% for ≥ 28 days. We further found that in ICU survivors, median (IQR) survival was 10.7 (0.7) years. While previous studies have evaluated prolonged ICU stays, they have been limited by studying limited subpopulations, such as patients who are dependent on dialysis or octogenarians, or used a single cutoff to define prolonged ICU stays, variably defined from > 48 hours to > 14 days.2-7,9-12,22 Our study is similar to others that used ≥ 2 cutoffs.1,8 However, our study was novel by providing 4 cutoffs to improve temporal prediction of hospital outcomes. Unlike a study by Ryan and colleagues, which found no increase in mortality with longer stay (43.5% for ≥ 14 days and 45% for ≥ 28 days), our study findings are similar to those of Yu and colleagues (11.1% mortality for prolonged ICU stays of 1 to 2 weeks, 26.6% for 2 to 4 weeks, and 31% for > 4 weeks) and others (8%, 3 to 14 days; 40%, >14 days; 10%, 1 to 2 weeks; 25.7% > 2 weeks) in finding a progressively increased hospital mortality with longer ICU stays.1,4,5,8 These differences may be related to different ICU populations or to improvements in care since Ryan and colleagues study was conducted.

Fewer studies have evaluated factors associated with mortality in cardiac surgery prolonged ICU stay patients. Our study is similar to other studies that evaluated risk factors by finding associations between a variety of comorbidities and process of care associated with both operative and long-term mortality; however, comparison between these studies is limited by the varying factors analyzed.1,3,5,6,8,9,11 We found that mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality, similar to noncardiac surgery patients and cardiac surgery patients.6,23,24 While we found several processes of care, such as catecholamine use and transfusions to be associated with mortality, which is similar to other studies, notably, we did not find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.1,25 While there is an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality in ICU patients, its status in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged ICU stays is less clear.26 While Ryan and colleagues found an association between renal replacement therapy and hospital mortality in patients staying ≥ 14 days, they did not find it in patients staying ≥.

28 days.1 Other studies of prolonged ICU stays for cardiac surgery patients have also failed to find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.5,6,9 Importantly, practice that expedites liberation from mechanical ventilation, such as fast tracking, daily spontaneous breathing trials, extubation to noninvasive respiratory support, and pulmonary rehabilitation may all have potential to limit mechanical ventilation duration and improve hospital survival and deserve further study.27-29Median (IQR) survival in hospital survivors was 10.7 (0.7) years, which is generally better than previously reported, but similar to that reported by Silberman and colleagues.2,4,6,8,11,12 Differences between these studies may relate to different patient populations within the cardiac surgery ICUs, definitions of prolonged ICU stays, or eras of care. Further study is needed to clarify these discrepancies. We found that cardiac transplantation and obesity were associated with the least risk of dying, while smoking, lung disease, and postoperative pneumonia were independently associated with increased hazard of dying. The obesity paradox, where obesity is protective, has been previously observed in cardiac surgery patients.30

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This is a single center study, and our patient population and processes of care may differ from other centers, limiting its generalizability. Notably, we do fewer coronary bypass operations and more aortic reconstructions and ventricular assist device insertions than do many other centers. Second, we did not have laboratory values for about one-third of patients (preceded EHR implementation). However, we were able to compensate for this by binning values and including missing data as an extra bin.20,21

The main strength of this study is that we were able to combine disparate records to assess a large number of potential factors associated with both operative and long-term mortality. This produced models that had good to very good discrimination. By producing models at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days to predict operative mortality and a model at discharge, it may help to provide objective data to facilitate conversations with patients and their families. However, further studies to externally validate these models should be conducted.

Conclusions

We found that longer prolonged ICU stays are associated with both operative and late mortality. Receiving mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, or 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality.

1. Ryan TA, Rady MY, Bashour A, Leventhal M, Lytle B, Starr NJ. Predictors of outcome in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care stay. Chest. 1997;112(4):1035-1042. doi:10.1378/chest.112.4.1035

2. Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.077

3. Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2012;94(1):109-116. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010

4. Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.103

5. Lapar DJ, Gillen JR, Crosby IK, et al. Predictors of operative mortality in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit duration. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.028

6. Manji RA, Arora RC, Singal RK, et al. Long-term outcome and predictors of noninstitutionalized survival subsequent to prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.004

7. Augustin P, Tanaka S, Chhor V, et al. Prognosis of prolonged intensive care unit stay after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1555-1561. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.07.029

8. Yu PJ, Cassiere HA, Fishbein J, Esposito RA, Hartman AR. Outcomes of patients with prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1550-1554. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.03.145

9. Bashour CA, Yared JP, Ryan TA, et al. Long-term survival and functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3847-3853. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00018

10. Isgro F, Skuras JA, Kiessling AH, Lehmann A, Saggau W. Survival and quality of life after a long-term intensive care stay. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(2):95-99. doi:10.1055/s-2002-26693

11. Williams MR, Wellner RB, Hartnett EA, Hartnett EA, Thornton B, Kavarana MN, Mahapatra R, Oz MC Sladen R. Long-term survival and quality of life in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(5):1472-1478.

12. Lagercrantz E, Lindblom D, Sartipy U. Survival and quality of life in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged intensive care. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:490-495. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03464-1

13. Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Coronary artery bypass grafting: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):12-19. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)90358-1

14. Lawrence DR, Valencia O, Smith EE, Murday A, Treasure T. Parsonnet score is a good predictor of the duration of intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery. Heart. 2000;83(4):429-432. doi:10.1136/heart.83.4.429

15. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(2):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.005

16. Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Hoglund P, Luhrs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1528-1534. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.060

17. Ghotkar SV, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Dihmis WC, Pullan DM. Preoperative calculation of risk for prolonged intensive care unit stay following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:14. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-1-1418. Messaoudi N, Decocker J, Stockman BA, Bossaert LL, Rodrigus IE. Is EuroSCORE useful in the prediction of extended intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;36(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.007

19. Ettema RG, Peelen LM, Schuurmans MJ, Nierich AP, Kalkman CJ, Moons KG. Prediction models for prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery: systematic review and validation study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):682-689. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.926808

20. Engoren M. Does erythrocyte blood transfusion prevent acute kidney injury? Propensity-matched case control analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e181f70f56

21. UK National Centre for Research Methods. Minimising the effect of missing data. Revised July 22, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.restore.ac.uk/srme/www/fac/soc/wie/research-new/srme/modules/mod3/9/index.html.

22. Leontyev S, Davierwala PM, Gaube LM, et al. Outcomes of dialysis-dependent patients after cardiac operations in a single-center experience of 483 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1270-1276. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.07.05223. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M. Complications associated with mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):55-62. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002799

24. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Hajjar MM, et al. Years of life lost after complications of coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):1893-1899. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.048

25. Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229-1239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070403

26. Truche AS, Ragey SP, Souweine B, et al. ICU survival and need of renal replacement therapy with respect to AKI duration in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0467-6

27. Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):567-574. doi:10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004

28. McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.018

29. Hernandez G, Vaquero C, Gonzalez P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711

30. Schwann TA, Ramira PS, Engoren MC, et al. Evidence and temporality of the obesity paradox in coronary bypass surgery: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54(5):896-903. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezy207

Prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, variably defined as > 48 h to > 14 days, are a known complication of cardiac surgery.1-8 Prolonged stays are associated with higher resource utilization and higher mortality.2,3,9-12 Although there are several cardiac surgery risk models that can be used preoperatively to identify patients at risk for prolonged ICU stay, factors that influence outcomes for patients who experience prolonged ICU stays are poorly understood.2,13-19 Little information is available to inform discussions between health care practitioners (HCPs) and patients throughout a prolonged ICU stay, especially those ≥ 7 days.

As cardiac surgical complexity, patient age, and preexisting comorbidities have increased over time, so has the need to provide patients and HCPs with data to inform decision making, enhance prognostication, and set realistic expectations at varying time intervals during prolonged ICU stay. The purpose of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term outcomes in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged ICU stays at relevant time intervals (7, 14, 21, and 28 days) and to determine factors that may predict a patient’s outcome after a prolonged ICU stay.

Methods

The University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent. We merged the University of Michigan Medical Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, which is updated periodically with late mortality, with elements of the electronic health record (EHR). Adult patients were included if they had cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan between January 2, 2001, and December 31, 2011. Late mortality was updated through December 1, 2014. Data are presented as frequency (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR) as appropriate. Bivariate comparisons between survivors and nonsurvivors were done with χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical data, Student t test for continuous normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous not normally distributed data. To determine factors associated with operative mortality (death within 30 days of surgery or hospital discharge, whichever occurred later), we used logistic regression with forward selection. All available factors were initially entered in the models.

Separate logistic models were created based on all data available at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Final models consisted of factors with statistically significant P values (< .05) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs that excluded 1. To determine factors associated with late mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazard model, which used data available at discharge and STS complications. As these complications did not include their timing, they could only be used in models created at discharge and not for days 7, 14, 21, and 28 models. Final models consisted of factors with P values < .05 and 95% CIs of the AORs or the hazard ratios (HRs) that excluded 1. As the EHR did not start recording data until January 2, 2004, and its capture of data remained incomplete for several years, rather than imputing these missing data or excluding these patients, we chose to create an extra categorical level for each factor to represent missing data. For continuous factors with missing data, we first converted the continuous data to terciles and the missing data became the fourth level.20,21

The discrimination of the logistic models were determined by the c-statistic and for the Cox proportional hazards model with the Harrell concordance index (C index). Time trends were assessed with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistics were calculated with SPSS versions 21-23 or SAS 9.4.

Results

Of 8309 admissions to the ICU after cardiac surgery, 1174 (14%) had ICU stays ≥ 7 days, 386 (5%) ≥ 14 days, 201 (2%) ≥ 21 days, and 80 (0.9%) ≥ 28 days. The prolonged ICU study population was mostly male, White race, with a mean (SD) age of 62 (14) years. Patients had a variety of comorbidities, most notably 61% had hypertension and half had heart failure. Valve surgery (55%) was the most common procedure (n = 651). Twenty-nine percent required > 1 procedure (eAppendix 1).

The operative mortality

Using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for factors associated with mortality, we found that receiving mechanical ventilation on the day of analysis was associated with increased operative mortality with AOR increasing from 3.35 (95% CI, 2.82-3.98) for

After multivariable Cox regression to adjust for confounders, we found that each postoperative week was associated with a 7% higher hazard of dying (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07-1.07; P < .001). Postoperative pneumonia was also associated with increased hazard of dying (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.27-1.99; P < .001),

Discussion

We found that operative mortality increased the longer the patient stayed in the ICU, ranging from 11% for ≥ 7 days to 35% for ≥ 28 days. We further found that in ICU survivors, median (IQR) survival was 10.7 (0.7) years. While previous studies have evaluated prolonged ICU stays, they have been limited by studying limited subpopulations, such as patients who are dependent on dialysis or octogenarians, or used a single cutoff to define prolonged ICU stays, variably defined from > 48 hours to > 14 days.2-7,9-12,22 Our study is similar to others that used ≥ 2 cutoffs.1,8 However, our study was novel by providing 4 cutoffs to improve temporal prediction of hospital outcomes. Unlike a study by Ryan and colleagues, which found no increase in mortality with longer stay (43.5% for ≥ 14 days and 45% for ≥ 28 days), our study findings are similar to those of Yu and colleagues (11.1% mortality for prolonged ICU stays of 1 to 2 weeks, 26.6% for 2 to 4 weeks, and 31% for > 4 weeks) and others (8%, 3 to 14 days; 40%, >14 days; 10%, 1 to 2 weeks; 25.7% > 2 weeks) in finding a progressively increased hospital mortality with longer ICU stays.1,4,5,8 These differences may be related to different ICU populations or to improvements in care since Ryan and colleagues study was conducted.

Fewer studies have evaluated factors associated with mortality in cardiac surgery prolonged ICU stay patients. Our study is similar to other studies that evaluated risk factors by finding associations between a variety of comorbidities and process of care associated with both operative and long-term mortality; however, comparison between these studies is limited by the varying factors analyzed.1,3,5,6,8,9,11 We found that mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality, similar to noncardiac surgery patients and cardiac surgery patients.6,23,24 While we found several processes of care, such as catecholamine use and transfusions to be associated with mortality, which is similar to other studies, notably, we did not find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.1,25 While there is an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality in ICU patients, its status in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged ICU stays is less clear.26 While Ryan and colleagues found an association between renal replacement therapy and hospital mortality in patients staying ≥ 14 days, they did not find it in patients staying ≥.

28 days.1 Other studies of prolonged ICU stays for cardiac surgery patients have also failed to find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.5,6,9 Importantly, practice that expedites liberation from mechanical ventilation, such as fast tracking, daily spontaneous breathing trials, extubation to noninvasive respiratory support, and pulmonary rehabilitation may all have potential to limit mechanical ventilation duration and improve hospital survival and deserve further study.27-29Median (IQR) survival in hospital survivors was 10.7 (0.7) years, which is generally better than previously reported, but similar to that reported by Silberman and colleagues.2,4,6,8,11,12 Differences between these studies may relate to different patient populations within the cardiac surgery ICUs, definitions of prolonged ICU stays, or eras of care. Further study is needed to clarify these discrepancies. We found that cardiac transplantation and obesity were associated with the least risk of dying, while smoking, lung disease, and postoperative pneumonia were independently associated with increased hazard of dying. The obesity paradox, where obesity is protective, has been previously observed in cardiac surgery patients.30

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This is a single center study, and our patient population and processes of care may differ from other centers, limiting its generalizability. Notably, we do fewer coronary bypass operations and more aortic reconstructions and ventricular assist device insertions than do many other centers. Second, we did not have laboratory values for about one-third of patients (preceded EHR implementation). However, we were able to compensate for this by binning values and including missing data as an extra bin.20,21

The main strength of this study is that we were able to combine disparate records to assess a large number of potential factors associated with both operative and long-term mortality. This produced models that had good to very good discrimination. By producing models at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days to predict operative mortality and a model at discharge, it may help to provide objective data to facilitate conversations with patients and their families. However, further studies to externally validate these models should be conducted.

Conclusions

We found that longer prolonged ICU stays are associated with both operative and late mortality. Receiving mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, or 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality.

Prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, variably defined as > 48 h to > 14 days, are a known complication of cardiac surgery.1-8 Prolonged stays are associated with higher resource utilization and higher mortality.2,3,9-12 Although there are several cardiac surgery risk models that can be used preoperatively to identify patients at risk for prolonged ICU stay, factors that influence outcomes for patients who experience prolonged ICU stays are poorly understood.2,13-19 Little information is available to inform discussions between health care practitioners (HCPs) and patients throughout a prolonged ICU stay, especially those ≥ 7 days.

As cardiac surgical complexity, patient age, and preexisting comorbidities have increased over time, so has the need to provide patients and HCPs with data to inform decision making, enhance prognostication, and set realistic expectations at varying time intervals during prolonged ICU stay. The purpose of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term outcomes in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged ICU stays at relevant time intervals (7, 14, 21, and 28 days) and to determine factors that may predict a patient’s outcome after a prolonged ICU stay.

Methods

The University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent. We merged the University of Michigan Medical Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, which is updated periodically with late mortality, with elements of the electronic health record (EHR). Adult patients were included if they had cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan between January 2, 2001, and December 31, 2011. Late mortality was updated through December 1, 2014. Data are presented as frequency (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR) as appropriate. Bivariate comparisons between survivors and nonsurvivors were done with χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical data, Student t test for continuous normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous not normally distributed data. To determine factors associated with operative mortality (death within 30 days of surgery or hospital discharge, whichever occurred later), we used logistic regression with forward selection. All available factors were initially entered in the models.

Separate logistic models were created based on all data available at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Final models consisted of factors with statistically significant P values (< .05) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs that excluded 1. To determine factors associated with late mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazard model, which used data available at discharge and STS complications. As these complications did not include their timing, they could only be used in models created at discharge and not for days 7, 14, 21, and 28 models. Final models consisted of factors with P values < .05 and 95% CIs of the AORs or the hazard ratios (HRs) that excluded 1. As the EHR did not start recording data until January 2, 2004, and its capture of data remained incomplete for several years, rather than imputing these missing data or excluding these patients, we chose to create an extra categorical level for each factor to represent missing data. For continuous factors with missing data, we first converted the continuous data to terciles and the missing data became the fourth level.20,21

The discrimination of the logistic models were determined by the c-statistic and for the Cox proportional hazards model with the Harrell concordance index (C index). Time trends were assessed with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistics were calculated with SPSS versions 21-23 or SAS 9.4.

Results

Of 8309 admissions to the ICU after cardiac surgery, 1174 (14%) had ICU stays ≥ 7 days, 386 (5%) ≥ 14 days, 201 (2%) ≥ 21 days, and 80 (0.9%) ≥ 28 days. The prolonged ICU study population was mostly male, White race, with a mean (SD) age of 62 (14) years. Patients had a variety of comorbidities, most notably 61% had hypertension and half had heart failure. Valve surgery (55%) was the most common procedure (n = 651). Twenty-nine percent required > 1 procedure (eAppendix 1).

The operative mortality

Using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for factors associated with mortality, we found that receiving mechanical ventilation on the day of analysis was associated with increased operative mortality with AOR increasing from 3.35 (95% CI, 2.82-3.98) for

After multivariable Cox regression to adjust for confounders, we found that each postoperative week was associated with a 7% higher hazard of dying (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07-1.07; P < .001). Postoperative pneumonia was also associated with increased hazard of dying (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.27-1.99; P < .001),

Discussion

We found that operative mortality increased the longer the patient stayed in the ICU, ranging from 11% for ≥ 7 days to 35% for ≥ 28 days. We further found that in ICU survivors, median (IQR) survival was 10.7 (0.7) years. While previous studies have evaluated prolonged ICU stays, they have been limited by studying limited subpopulations, such as patients who are dependent on dialysis or octogenarians, or used a single cutoff to define prolonged ICU stays, variably defined from > 48 hours to > 14 days.2-7,9-12,22 Our study is similar to others that used ≥ 2 cutoffs.1,8 However, our study was novel by providing 4 cutoffs to improve temporal prediction of hospital outcomes. Unlike a study by Ryan and colleagues, which found no increase in mortality with longer stay (43.5% for ≥ 14 days and 45% for ≥ 28 days), our study findings are similar to those of Yu and colleagues (11.1% mortality for prolonged ICU stays of 1 to 2 weeks, 26.6% for 2 to 4 weeks, and 31% for > 4 weeks) and others (8%, 3 to 14 days; 40%, >14 days; 10%, 1 to 2 weeks; 25.7% > 2 weeks) in finding a progressively increased hospital mortality with longer ICU stays.1,4,5,8 These differences may be related to different ICU populations or to improvements in care since Ryan and colleagues study was conducted.

Fewer studies have evaluated factors associated with mortality in cardiac surgery prolonged ICU stay patients. Our study is similar to other studies that evaluated risk factors by finding associations between a variety of comorbidities and process of care associated with both operative and long-term mortality; however, comparison between these studies is limited by the varying factors analyzed.1,3,5,6,8,9,11 We found that mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality, similar to noncardiac surgery patients and cardiac surgery patients.6,23,24 While we found several processes of care, such as catecholamine use and transfusions to be associated with mortality, which is similar to other studies, notably, we did not find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.1,25 While there is an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality in ICU patients, its status in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged ICU stays is less clear.26 While Ryan and colleagues found an association between renal replacement therapy and hospital mortality in patients staying ≥ 14 days, they did not find it in patients staying ≥.

28 days.1 Other studies of prolonged ICU stays for cardiac surgery patients have also failed to find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.5,6,9 Importantly, practice that expedites liberation from mechanical ventilation, such as fast tracking, daily spontaneous breathing trials, extubation to noninvasive respiratory support, and pulmonary rehabilitation may all have potential to limit mechanical ventilation duration and improve hospital survival and deserve further study.27-29Median (IQR) survival in hospital survivors was 10.7 (0.7) years, which is generally better than previously reported, but similar to that reported by Silberman and colleagues.2,4,6,8,11,12 Differences between these studies may relate to different patient populations within the cardiac surgery ICUs, definitions of prolonged ICU stays, or eras of care. Further study is needed to clarify these discrepancies. We found that cardiac transplantation and obesity were associated with the least risk of dying, while smoking, lung disease, and postoperative pneumonia were independently associated with increased hazard of dying. The obesity paradox, where obesity is protective, has been previously observed in cardiac surgery patients.30

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This is a single center study, and our patient population and processes of care may differ from other centers, limiting its generalizability. Notably, we do fewer coronary bypass operations and more aortic reconstructions and ventricular assist device insertions than do many other centers. Second, we did not have laboratory values for about one-third of patients (preceded EHR implementation). However, we were able to compensate for this by binning values and including missing data as an extra bin.20,21

The main strength of this study is that we were able to combine disparate records to assess a large number of potential factors associated with both operative and long-term mortality. This produced models that had good to very good discrimination. By producing models at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days to predict operative mortality and a model at discharge, it may help to provide objective data to facilitate conversations with patients and their families. However, further studies to externally validate these models should be conducted.

Conclusions

We found that longer prolonged ICU stays are associated with both operative and late mortality. Receiving mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, or 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality.

1. Ryan TA, Rady MY, Bashour A, Leventhal M, Lytle B, Starr NJ. Predictors of outcome in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care stay. Chest. 1997;112(4):1035-1042. doi:10.1378/chest.112.4.1035

2. Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.077

3. Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2012;94(1):109-116. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010

4. Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.103

5. Lapar DJ, Gillen JR, Crosby IK, et al. Predictors of operative mortality in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit duration. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.028

6. Manji RA, Arora RC, Singal RK, et al. Long-term outcome and predictors of noninstitutionalized survival subsequent to prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.004

7. Augustin P, Tanaka S, Chhor V, et al. Prognosis of prolonged intensive care unit stay after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1555-1561. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.07.029

8. Yu PJ, Cassiere HA, Fishbein J, Esposito RA, Hartman AR. Outcomes of patients with prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1550-1554. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.03.145

9. Bashour CA, Yared JP, Ryan TA, et al. Long-term survival and functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3847-3853. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00018

10. Isgro F, Skuras JA, Kiessling AH, Lehmann A, Saggau W. Survival and quality of life after a long-term intensive care stay. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(2):95-99. doi:10.1055/s-2002-26693

11. Williams MR, Wellner RB, Hartnett EA, Hartnett EA, Thornton B, Kavarana MN, Mahapatra R, Oz MC Sladen R. Long-term survival and quality of life in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(5):1472-1478.

12. Lagercrantz E, Lindblom D, Sartipy U. Survival and quality of life in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged intensive care. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:490-495. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03464-1

13. Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Coronary artery bypass grafting: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):12-19. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)90358-1

14. Lawrence DR, Valencia O, Smith EE, Murday A, Treasure T. Parsonnet score is a good predictor of the duration of intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery. Heart. 2000;83(4):429-432. doi:10.1136/heart.83.4.429

15. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(2):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.005

16. Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Hoglund P, Luhrs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1528-1534. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.060

17. Ghotkar SV, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Dihmis WC, Pullan DM. Preoperative calculation of risk for prolonged intensive care unit stay following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:14. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-1-1418. Messaoudi N, Decocker J, Stockman BA, Bossaert LL, Rodrigus IE. Is EuroSCORE useful in the prediction of extended intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;36(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.007

19. Ettema RG, Peelen LM, Schuurmans MJ, Nierich AP, Kalkman CJ, Moons KG. Prediction models for prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery: systematic review and validation study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):682-689. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.926808

20. Engoren M. Does erythrocyte blood transfusion prevent acute kidney injury? Propensity-matched case control analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e181f70f56

21. UK National Centre for Research Methods. Minimising the effect of missing data. Revised July 22, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.restore.ac.uk/srme/www/fac/soc/wie/research-new/srme/modules/mod3/9/index.html.

22. Leontyev S, Davierwala PM, Gaube LM, et al. Outcomes of dialysis-dependent patients after cardiac operations in a single-center experience of 483 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1270-1276. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.07.05223. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M. Complications associated with mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):55-62. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002799

24. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Hajjar MM, et al. Years of life lost after complications of coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):1893-1899. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.048

25. Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229-1239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070403

26. Truche AS, Ragey SP, Souweine B, et al. ICU survival and need of renal replacement therapy with respect to AKI duration in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0467-6

27. Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):567-574. doi:10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004

28. McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.018

29. Hernandez G, Vaquero C, Gonzalez P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711

30. Schwann TA, Ramira PS, Engoren MC, et al. Evidence and temporality of the obesity paradox in coronary bypass surgery: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54(5):896-903. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezy207

1. Ryan TA, Rady MY, Bashour A, Leventhal M, Lytle B, Starr NJ. Predictors of outcome in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care stay. Chest. 1997;112(4):1035-1042. doi:10.1378/chest.112.4.1035

2. Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.077

3. Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2012;94(1):109-116. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010

4. Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.103

5. Lapar DJ, Gillen JR, Crosby IK, et al. Predictors of operative mortality in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit duration. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.028

6. Manji RA, Arora RC, Singal RK, et al. Long-term outcome and predictors of noninstitutionalized survival subsequent to prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.004

7. Augustin P, Tanaka S, Chhor V, et al. Prognosis of prolonged intensive care unit stay after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1555-1561. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.07.029

8. Yu PJ, Cassiere HA, Fishbein J, Esposito RA, Hartman AR. Outcomes of patients with prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1550-1554. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.03.145

9. Bashour CA, Yared JP, Ryan TA, et al. Long-term survival and functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3847-3853. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00018

10. Isgro F, Skuras JA, Kiessling AH, Lehmann A, Saggau W. Survival and quality of life after a long-term intensive care stay. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(2):95-99. doi:10.1055/s-2002-26693

11. Williams MR, Wellner RB, Hartnett EA, Hartnett EA, Thornton B, Kavarana MN, Mahapatra R, Oz MC Sladen R. Long-term survival and quality of life in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(5):1472-1478.

12. Lagercrantz E, Lindblom D, Sartipy U. Survival and quality of life in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged intensive care. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:490-495. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03464-1

13. Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Coronary artery bypass grafting: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):12-19. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)90358-1

14. Lawrence DR, Valencia O, Smith EE, Murday A, Treasure T. Parsonnet score is a good predictor of the duration of intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery. Heart. 2000;83(4):429-432. doi:10.1136/heart.83.4.429

15. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(2):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.005

16. Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Hoglund P, Luhrs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1528-1534. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.060

17. Ghotkar SV, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Dihmis WC, Pullan DM. Preoperative calculation of risk for prolonged intensive care unit stay following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:14. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-1-1418. Messaoudi N, Decocker J, Stockman BA, Bossaert LL, Rodrigus IE. Is EuroSCORE useful in the prediction of extended intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;36(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.007

19. Ettema RG, Peelen LM, Schuurmans MJ, Nierich AP, Kalkman CJ, Moons KG. Prediction models for prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery: systematic review and validation study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):682-689. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.926808

20. Engoren M. Does erythrocyte blood transfusion prevent acute kidney injury? Propensity-matched case control analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e181f70f56

21. UK National Centre for Research Methods. Minimising the effect of missing data. Revised July 22, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.restore.ac.uk/srme/www/fac/soc/wie/research-new/srme/modules/mod3/9/index.html.

22. Leontyev S, Davierwala PM, Gaube LM, et al. Outcomes of dialysis-dependent patients after cardiac operations in a single-center experience of 483 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1270-1276. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.07.05223. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M. Complications associated with mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):55-62. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002799

24. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Hajjar MM, et al. Years of life lost after complications of coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):1893-1899. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.048

25. Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229-1239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070403

26. Truche AS, Ragey SP, Souweine B, et al. ICU survival and need of renal replacement therapy with respect to AKI duration in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0467-6

27. Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):567-574. doi:10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004

28. McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.018

29. Hernandez G, Vaquero C, Gonzalez P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711

30. Schwann TA, Ramira PS, Engoren MC, et al. Evidence and temporality of the obesity paradox in coronary bypass surgery: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54(5):896-903. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezy207

NSAIDs for spondyloarthritis may affect time to conception

PHILADELPHIA – Women with spondyloarthritis (SpA) who are desiring pregnancy may want to consider decreasing use or discontinuing use (with supervision) of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before conception, new data suggest.

Researchers have found a connection between NSAID use and age and a significantly longer time to conception among women with spondyloarthritis. Sabrina Hamroun, MMed, with the rheumatology department at the University Hospital Cochin, Paris, presented the findings during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

SpA commonly affects women of childbearing age, but data are sparse regarding the effects of disease on fertility.

Patients in the study were taken from the French multicenter cohort GR2 from 2015 to June 2021.

Among the 207 patients with SpA in the cohort, 88 were selected for analysis of time to conception. Of these, 56 patients (63.6%) had a clinical pregnancy during follow-up.

Subfertility group took an average of 16 months to get pregnant

Subfertility was observed in 40 (45.4%) of the women, with an average time to conception of 16.1 months. A woman was considered subfertile if her time to conception was more than 12 months or if she did not become pregnant.

The average preconception Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index score was 2.9 (+/- 2.1), the authors noted. The average age of the participants was 32 years.

Twenty-three patients were treated with NSAIDs, eight with corticosteroids, 12 with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and 61 with biologics.

Researchers adjusted for factors including age, body mass index, disease duration and severity, smoking, form of SpA (axial, peripheral, or both), and medication in the preconception period.

They found significant associations between longer time to conception and age (hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.40; P < .001), and a much higher hazard ratio with the use of NSAIDs during preconception (HR, 3.01; 95% CI, 2.15-3.85; P = .01).

Some data unavailable

Ms. Hamroun acknowledged that no data were available on the frequency of sexual intercourse or quality of life, factors that could affect time to conception. Women were asked when they discontinued contraceptive use and actively began trying to become pregnant.

She stated that information on the dose of NSAIDs used by the patients was incomplete, noting, “We were therefore unable to adjust the results of our statistical analyses on the dose used by patients.”

Additionally, because the study participants were patients at tertiary centers in France and had more severe disease, the results may not be generalizable to all women of childbearing age. Patients with less severe SpA are often managed in outpatient settings in France, she said.

When asked about alternatives to NSAIDs, Ms. Hamroun said that anti–tumor necrosis factor agents with low placental passage may be a good alternative “if a woman with long-standing difficulties to conceive needs a regular use of NSAIDs to control disease activity, in the absence of any other cause of subfertility.”

The patient’s age must also be considered, she noted.

“A therapeutic switch may be favored in a woman over 35 years of age, for example, whose fertility is already impaired by age,” Ms. Hamroun said.

As for the mechanism that might explain the effects of NSAIDs on conception, Ms. Hamroun said that prostaglandins are essential to ovulation and embryo implantation and explained that NSAIDs may work against ovulation and result in poor implantation (miscarriage) by blocking prostaglandins.

She pointed out that her results are in line with the ACR’s recommendation to discontinue NSAID use during the preconception period in women with SpA who are having difficulty conceiving.

Control before conception is important

Sinead Maguire, MD, a clinical and research fellow in the Spondylitis Program at Toronto (Ont.) Western Hospital who was not part of the study, said the study highlights the importance of optimizing disease control before conception.

“There are a number of things rheumatologists can do to support our SpA patients when they are trying to conceive,” she told this news organization. “One of the most important issues to address is ensuring their SpA is in remission and continues to remain so. For that reason, if a woman is requiring regular NSAIDs for symptom control, the results of this study might encourage me to consider a biologic agent sooner to ensure remission.”

She urged women who want to become pregnant to discuss medications with their rheumatologist before trying to conceive.

“It is very exciting to see studies such as this so that rheumatologists can provide answers to our patients’ questions with evidence-based advice,” she said.

Ms. Hamroun and several coauthors had no disclosures. Other coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Merck/MSD, Novartis, Janssen, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and/or UCB. Dr. Maguire reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHILADELPHIA – Women with spondyloarthritis (SpA) who are desiring pregnancy may want to consider decreasing use or discontinuing use (with supervision) of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before conception, new data suggest.

Researchers have found a connection between NSAID use and age and a significantly longer time to conception among women with spondyloarthritis. Sabrina Hamroun, MMed, with the rheumatology department at the University Hospital Cochin, Paris, presented the findings during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

SpA commonly affects women of childbearing age, but data are sparse regarding the effects of disease on fertility.

Patients in the study were taken from the French multicenter cohort GR2 from 2015 to June 2021.

Among the 207 patients with SpA in the cohort, 88 were selected for analysis of time to conception. Of these, 56 patients (63.6%) had a clinical pregnancy during follow-up.

Subfertility group took an average of 16 months to get pregnant

Subfertility was observed in 40 (45.4%) of the women, with an average time to conception of 16.1 months. A woman was considered subfertile if her time to conception was more than 12 months or if she did not become pregnant.

The average preconception Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index score was 2.9 (+/- 2.1), the authors noted. The average age of the participants was 32 years.

Twenty-three patients were treated with NSAIDs, eight with corticosteroids, 12 with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and 61 with biologics.

Researchers adjusted for factors including age, body mass index, disease duration and severity, smoking, form of SpA (axial, peripheral, or both), and medication in the preconception period.

They found significant associations between longer time to conception and age (hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.40; P < .001), and a much higher hazard ratio with the use of NSAIDs during preconception (HR, 3.01; 95% CI, 2.15-3.85; P = .01).

Some data unavailable

Ms. Hamroun acknowledged that no data were available on the frequency of sexual intercourse or quality of life, factors that could affect time to conception. Women were asked when they discontinued contraceptive use and actively began trying to become pregnant.

She stated that information on the dose of NSAIDs used by the patients was incomplete, noting, “We were therefore unable to adjust the results of our statistical analyses on the dose used by patients.”

Additionally, because the study participants were patients at tertiary centers in France and had more severe disease, the results may not be generalizable to all women of childbearing age. Patients with less severe SpA are often managed in outpatient settings in France, she said.

When asked about alternatives to NSAIDs, Ms. Hamroun said that anti–tumor necrosis factor agents with low placental passage may be a good alternative “if a woman with long-standing difficulties to conceive needs a regular use of NSAIDs to control disease activity, in the absence of any other cause of subfertility.”

The patient’s age must also be considered, she noted.

“A therapeutic switch may be favored in a woman over 35 years of age, for example, whose fertility is already impaired by age,” Ms. Hamroun said.

As for the mechanism that might explain the effects of NSAIDs on conception, Ms. Hamroun said that prostaglandins are essential to ovulation and embryo implantation and explained that NSAIDs may work against ovulation and result in poor implantation (miscarriage) by blocking prostaglandins.

She pointed out that her results are in line with the ACR’s recommendation to discontinue NSAID use during the preconception period in women with SpA who are having difficulty conceiving.

Control before conception is important

Sinead Maguire, MD, a clinical and research fellow in the Spondylitis Program at Toronto (Ont.) Western Hospital who was not part of the study, said the study highlights the importance of optimizing disease control before conception.

“There are a number of things rheumatologists can do to support our SpA patients when they are trying to conceive,” she told this news organization. “One of the most important issues to address is ensuring their SpA is in remission and continues to remain so. For that reason, if a woman is requiring regular NSAIDs for symptom control, the results of this study might encourage me to consider a biologic agent sooner to ensure remission.”

She urged women who want to become pregnant to discuss medications with their rheumatologist before trying to conceive.

“It is very exciting to see studies such as this so that rheumatologists can provide answers to our patients’ questions with evidence-based advice,” she said.

Ms. Hamroun and several coauthors had no disclosures. Other coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Merck/MSD, Novartis, Janssen, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and/or UCB. Dr. Maguire reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PHILADELPHIA – Women with spondyloarthritis (SpA) who are desiring pregnancy may want to consider decreasing use or discontinuing use (with supervision) of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before conception, new data suggest.

Researchers have found a connection between NSAID use and age and a significantly longer time to conception among women with spondyloarthritis. Sabrina Hamroun, MMed, with the rheumatology department at the University Hospital Cochin, Paris, presented the findings during a press conference at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

SpA commonly affects women of childbearing age, but data are sparse regarding the effects of disease on fertility.

Patients in the study were taken from the French multicenter cohort GR2 from 2015 to June 2021.

Among the 207 patients with SpA in the cohort, 88 were selected for analysis of time to conception. Of these, 56 patients (63.6%) had a clinical pregnancy during follow-up.

Subfertility group took an average of 16 months to get pregnant

Subfertility was observed in 40 (45.4%) of the women, with an average time to conception of 16.1 months. A woman was considered subfertile if her time to conception was more than 12 months or if she did not become pregnant.

The average preconception Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index score was 2.9 (+/- 2.1), the authors noted. The average age of the participants was 32 years.

Twenty-three patients were treated with NSAIDs, eight with corticosteroids, 12 with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and 61 with biologics.

Researchers adjusted for factors including age, body mass index, disease duration and severity, smoking, form of SpA (axial, peripheral, or both), and medication in the preconception period.

They found significant associations between longer time to conception and age (hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-1.40; P < .001), and a much higher hazard ratio with the use of NSAIDs during preconception (HR, 3.01; 95% CI, 2.15-3.85; P = .01).

Some data unavailable

Ms. Hamroun acknowledged that no data were available on the frequency of sexual intercourse or quality of life, factors that could affect time to conception. Women were asked when they discontinued contraceptive use and actively began trying to become pregnant.

She stated that information on the dose of NSAIDs used by the patients was incomplete, noting, “We were therefore unable to adjust the results of our statistical analyses on the dose used by patients.”

Additionally, because the study participants were patients at tertiary centers in France and had more severe disease, the results may not be generalizable to all women of childbearing age. Patients with less severe SpA are often managed in outpatient settings in France, she said.

When asked about alternatives to NSAIDs, Ms. Hamroun said that anti–tumor necrosis factor agents with low placental passage may be a good alternative “if a woman with long-standing difficulties to conceive needs a regular use of NSAIDs to control disease activity, in the absence of any other cause of subfertility.”

The patient’s age must also be considered, she noted.

“A therapeutic switch may be favored in a woman over 35 years of age, for example, whose fertility is already impaired by age,” Ms. Hamroun said.

As for the mechanism that might explain the effects of NSAIDs on conception, Ms. Hamroun said that prostaglandins are essential to ovulation and embryo implantation and explained that NSAIDs may work against ovulation and result in poor implantation (miscarriage) by blocking prostaglandins.

She pointed out that her results are in line with the ACR’s recommendation to discontinue NSAID use during the preconception period in women with SpA who are having difficulty conceiving.

Control before conception is important

Sinead Maguire, MD, a clinical and research fellow in the Spondylitis Program at Toronto (Ont.) Western Hospital who was not part of the study, said the study highlights the importance of optimizing disease control before conception.

“There are a number of things rheumatologists can do to support our SpA patients when they are trying to conceive,” she told this news organization. “One of the most important issues to address is ensuring their SpA is in remission and continues to remain so. For that reason, if a woman is requiring regular NSAIDs for symptom control, the results of this study might encourage me to consider a biologic agent sooner to ensure remission.”

She urged women who want to become pregnant to discuss medications with their rheumatologist before trying to conceive.

“It is very exciting to see studies such as this so that rheumatologists can provide answers to our patients’ questions with evidence-based advice,” she said.

Ms. Hamroun and several coauthors had no disclosures. Other coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Merck/MSD, Novartis, Janssen, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and/or UCB. Dr. Maguire reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2022

Combination therapy shows mixed results for scleroderma-related lung disease

PHILADELPHIA – Combining the immunomodulatory agent mycophenolate with the antifibrotic pirfenidone led to more rapid improvement and showed a trend to be more effective than mycophenolate mofetil alone for treating the signs and symptoms of scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease, but the combination therapy came with an increase in side effects, according to results from the Scleroderma Lung Study III.

Dinesh Khanna, MBBS, MSc, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, presented the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. He noted some problems with the study – namely its small size, enrolling only 51 patients, about one-third of its original goal. But he also said it showed a potential signal for efficacy and that the study itself could serve as a “template” for future studies of combination mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) plus pirfenidone therapy for scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD).

“The pirfenidone patients had quite a bit more GI side effects and photosensitivity, and those are known side effects,” Dr. Khanna said in an interview. “So the combination therapy had more side effects but trends to higher efficacy.”

The design of SLS-III, a phase 2 clinical trial, was a challenge, Dr. Khanna explained. The goal was to enroll 150 SSc-ILD patients who hadn’t had any previous treatment for their disease. Finding those patients proved difficult. “In fact, if you look at the recent history, 70% of the patients with early diffuse scleroderma are on MMF,” he said in his presentation. Compounding low study enrollment was the intervening COVID-19 pandemic, he added.

Testing a faster-acting combination

Nonetheless, the trial managed to enroll 27 patients in the combination therapy group and 24 in the MMF-plus-placebo group and compared their outcomes over 18 months. Study dosing was 1,500 mg MMF twice daily and pirfenidone 801 mg three times daily, titrated to the tolerable dose.

Despite the study’s being underpowered, Dr. Khanna said, it still reported some notable outcomes that merit further investigation. “I think what was intriguing in the study was the long-term benefit in the patient-reported outcomes and the structural changes,” he said in the interview.

Among those notable outcomes was a clinically significant change in forced vital capacity (FVC) percentage for the combination vs. the placebo groups: 2.24% vs. 2.09%. He also noted that the combination group saw a somewhat more robust improvement in FVC at six months: 2.59% (± 0.98%) vs. 0.92% (± 1.1%) in the placebo group.

The combination group showed greater improvements in high-resolution computed tomography-evaluated lung involvement and lung fibrosis and patient-reported outcomes, including a statistically significant 3.67-point greater improvement in PROMIS-29 physical function score (4.42 vs. 0.75).

The patients on combination therapy had higher rates of serious adverse events (SAEs), and seven discontinued one or both study drugs early, all in the combined arm. Four combination therapy patients had six SAEs, compared to two placebo patients with three SAEs. In the combination group, SAEs included chest pain, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, nodular basal cell cancer, marginal zone B cell lymphoma, renal crisis, and dyspnea. SAEs in the placebo group were colitis, COVID-19 and hypoxic respiratory failure.

Study design challenges

Nonetheless, Dr. Khanna said the SLS-III data are consistent with the SLS-II findings, with mean improvements in FVC of 2.24% and 2.1%, respectively.

“The next study may be able to replicate what we tried to do, keeping in mind that there are really no MMF-naive patients who are walking around,” Dr. Khanna said. “So the challenge is about the feasibility of recruiting within a trial vs. trying to show a statistical difference between the drug and placebo.”

This study could serve as a foundation for future studies of MMF in patients with SSc-ILD, Robert Spiera, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, said in an interview. “There are lessons to be learned both from the study but also from prior studies looking at MMF use in the background in patients treated with other drugs in clinical trials,” he said.

Dr. Spiera noted that the study had other challenges besides the difficulty in recruiting patients who hadn’t been on MMF therapy. “A great challenge is that the benefit with regard to the impact on the lungs from MMF seems most prominent in the first 6 months to a year to even 2 years that somebody is on the drug,” he said.

The other challenge with this study is that a large proportion of patients had limited systemic disease and relatively lower levels of skin disease compared with other studies of patients on MMF, Dr. Spiera said.

“The optimal treatment of scleroderma-associated lung disease remains a very important and not-adequately met need,” he said. “Particularly, we’re looking for drugs that are tolerable in a patient population that are very prone to GI side effects in general. This study and others have taught us a lot about trial design, and I think more globally this will allow us to move this field forward.”

Dr. Khanna disclosed relationships with Actelion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Horizon Therapeutics USA, Janssen Global Services, Prometheus Biosciences, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., Genentech/Roche, Theraly, and Pfizer. Genentech provided funding for the study and pirfenidone and placebo drugs at no cost.

Dr. Spiera disclosed relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Corbus Pharmaceutical, InflaRx, AbbVie/Abbott, Sanofi, Novartis, Chemocentryx, Roche and Vera.

PHILADELPHIA – Combining the immunomodulatory agent mycophenolate with the antifibrotic pirfenidone led to more rapid improvement and showed a trend to be more effective than mycophenolate mofetil alone for treating the signs and symptoms of scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease, but the combination therapy came with an increase in side effects, according to results from the Scleroderma Lung Study III.

Dinesh Khanna, MBBS, MSc, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, presented the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. He noted some problems with the study – namely its small size, enrolling only 51 patients, about one-third of its original goal. But he also said it showed a potential signal for efficacy and that the study itself could serve as a “template” for future studies of combination mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) plus pirfenidone therapy for scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD).

“The pirfenidone patients had quite a bit more GI side effects and photosensitivity, and those are known side effects,” Dr. Khanna said in an interview. “So the combination therapy had more side effects but trends to higher efficacy.”

The design of SLS-III, a phase 2 clinical trial, was a challenge, Dr. Khanna explained. The goal was to enroll 150 SSc-ILD patients who hadn’t had any previous treatment for their disease. Finding those patients proved difficult. “In fact, if you look at the recent history, 70% of the patients with early diffuse scleroderma are on MMF,” he said in his presentation. Compounding low study enrollment was the intervening COVID-19 pandemic, he added.

Testing a faster-acting combination

Nonetheless, the trial managed to enroll 27 patients in the combination therapy group and 24 in the MMF-plus-placebo group and compared their outcomes over 18 months. Study dosing was 1,500 mg MMF twice daily and pirfenidone 801 mg three times daily, titrated to the tolerable dose.

Despite the study’s being underpowered, Dr. Khanna said, it still reported some notable outcomes that merit further investigation. “I think what was intriguing in the study was the long-term benefit in the patient-reported outcomes and the structural changes,” he said in the interview.

Among those notable outcomes was a clinically significant change in forced vital capacity (FVC) percentage for the combination vs. the placebo groups: 2.24% vs. 2.09%. He also noted that the combination group saw a somewhat more robust improvement in FVC at six months: 2.59% (± 0.98%) vs. 0.92% (± 1.1%) in the placebo group.

The combination group showed greater improvements in high-resolution computed tomography-evaluated lung involvement and lung fibrosis and patient-reported outcomes, including a statistically significant 3.67-point greater improvement in PROMIS-29 physical function score (4.42 vs. 0.75).

The patients on combination therapy had higher rates of serious adverse events (SAEs), and seven discontinued one or both study drugs early, all in the combined arm. Four combination therapy patients had six SAEs, compared to two placebo patients with three SAEs. In the combination group, SAEs included chest pain, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, nodular basal cell cancer, marginal zone B cell lymphoma, renal crisis, and dyspnea. SAEs in the placebo group were colitis, COVID-19 and hypoxic respiratory failure.

Study design challenges

Nonetheless, Dr. Khanna said the SLS-III data are consistent with the SLS-II findings, with mean improvements in FVC of 2.24% and 2.1%, respectively.

“The next study may be able to replicate what we tried to do, keeping in mind that there are really no MMF-naive patients who are walking around,” Dr. Khanna said. “So the challenge is about the feasibility of recruiting within a trial vs. trying to show a statistical difference between the drug and placebo.”

This study could serve as a foundation for future studies of MMF in patients with SSc-ILD, Robert Spiera, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, said in an interview. “There are lessons to be learned both from the study but also from prior studies looking at MMF use in the background in patients treated with other drugs in clinical trials,” he said.

Dr. Spiera noted that the study had other challenges besides the difficulty in recruiting patients who hadn’t been on MMF therapy. “A great challenge is that the benefit with regard to the impact on the lungs from MMF seems most prominent in the first 6 months to a year to even 2 years that somebody is on the drug,” he said.

The other challenge with this study is that a large proportion of patients had limited systemic disease and relatively lower levels of skin disease compared with other studies of patients on MMF, Dr. Spiera said.

“The optimal treatment of scleroderma-associated lung disease remains a very important and not-adequately met need,” he said. “Particularly, we’re looking for drugs that are tolerable in a patient population that are very prone to GI side effects in general. This study and others have taught us a lot about trial design, and I think more globally this will allow us to move this field forward.”

Dr. Khanna disclosed relationships with Actelion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Horizon Therapeutics USA, Janssen Global Services, Prometheus Biosciences, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., Genentech/Roche, Theraly, and Pfizer. Genentech provided funding for the study and pirfenidone and placebo drugs at no cost.

Dr. Spiera disclosed relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Corbus Pharmaceutical, InflaRx, AbbVie/Abbott, Sanofi, Novartis, Chemocentryx, Roche and Vera.

PHILADELPHIA – Combining the immunomodulatory agent mycophenolate with the antifibrotic pirfenidone led to more rapid improvement and showed a trend to be more effective than mycophenolate mofetil alone for treating the signs and symptoms of scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease, but the combination therapy came with an increase in side effects, according to results from the Scleroderma Lung Study III.

Dinesh Khanna, MBBS, MSc, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, presented the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. He noted some problems with the study – namely its small size, enrolling only 51 patients, about one-third of its original goal. But he also said it showed a potential signal for efficacy and that the study itself could serve as a “template” for future studies of combination mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) plus pirfenidone therapy for scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD).

“The pirfenidone patients had quite a bit more GI side effects and photosensitivity, and those are known side effects,” Dr. Khanna said in an interview. “So the combination therapy had more side effects but trends to higher efficacy.”