User login

Early autologous fat grafting associated with increased BC recurrence risk

Key clinical point: Autologous fat grafting (AFG) in the second stage of a 2-stage prosthetic breast reconstruction was linked to a higher risk for breast cancer (BC) recurrence when performed within a year after mastectomy.

Major finding: Patients who did vs did not undergo AFG within 1 year after the primary operation had a significantly increased risk for disease recurrence (hazard ratio 5.701; 95% CI 1.164-27.927). However, delaying the fat grafting beyond 12 months after mastectomy did not affect survival outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 267 patients with unilateral invasive BC who underwent total mastectomy and immediate tissue-expander-based reconstruction, of which 203 patients underwent the second-stage operation within 12 months of mastectomy and 64 patients underwent the operation after 12 months of mastectomy.

Disclosures: This study did not report the source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee KT et al. Association of fat graft with breast cancer recurrence in implant-based reconstruction: Does the timing matter? Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;30(2):1087-1097 (Dec 10). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12389-0

Key clinical point: Autologous fat grafting (AFG) in the second stage of a 2-stage prosthetic breast reconstruction was linked to a higher risk for breast cancer (BC) recurrence when performed within a year after mastectomy.

Major finding: Patients who did vs did not undergo AFG within 1 year after the primary operation had a significantly increased risk for disease recurrence (hazard ratio 5.701; 95% CI 1.164-27.927). However, delaying the fat grafting beyond 12 months after mastectomy did not affect survival outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 267 patients with unilateral invasive BC who underwent total mastectomy and immediate tissue-expander-based reconstruction, of which 203 patients underwent the second-stage operation within 12 months of mastectomy and 64 patients underwent the operation after 12 months of mastectomy.

Disclosures: This study did not report the source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee KT et al. Association of fat graft with breast cancer recurrence in implant-based reconstruction: Does the timing matter? Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;30(2):1087-1097 (Dec 10). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12389-0

Key clinical point: Autologous fat grafting (AFG) in the second stage of a 2-stage prosthetic breast reconstruction was linked to a higher risk for breast cancer (BC) recurrence when performed within a year after mastectomy.

Major finding: Patients who did vs did not undergo AFG within 1 year after the primary operation had a significantly increased risk for disease recurrence (hazard ratio 5.701; 95% CI 1.164-27.927). However, delaying the fat grafting beyond 12 months after mastectomy did not affect survival outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 267 patients with unilateral invasive BC who underwent total mastectomy and immediate tissue-expander-based reconstruction, of which 203 patients underwent the second-stage operation within 12 months of mastectomy and 64 patients underwent the operation after 12 months of mastectomy.

Disclosures: This study did not report the source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee KT et al. Association of fat graft with breast cancer recurrence in implant-based reconstruction: Does the timing matter? Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;30(2):1087-1097 (Dec 10). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12389-0

Meta-analysis compares adjuvant chemotherapy regimens for resected early-stage TNBC

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), adding capecitabine to classic anthracycline/taxane-based adjuvant chemotherapy improved overall survival (OS) and carboplatin/paclitaxel was the most effective regimen for improving disease-free survival (DFS).

Major finding: Adjuvant chemotherapy with anthracyclines/taxanes plus capecitabine vs anthracyclines significantly improved OS outcomes (hazard ratio [HR] 0.56; 95% CI 0.36-0.87; probability for ranking the first 29%), whereas carboplatin/paclitaxel vs anthracyclines was the best regimen for improving DFS outcomes (HR 0.51; 95% CI 0.30-0.86; probability for ranking the first 41%).

Study details: Findings are from a network meta-analysis of 27 randomized phase 3 trials that compared adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in patients with resected, stage I-III TNBC.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Petrelli F et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected triple negative breast cancer patients: A network meta-analysis. Breast. 2022;67:8-13 (Dec 15). Doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.12.004

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), adding capecitabine to classic anthracycline/taxane-based adjuvant chemotherapy improved overall survival (OS) and carboplatin/paclitaxel was the most effective regimen for improving disease-free survival (DFS).

Major finding: Adjuvant chemotherapy with anthracyclines/taxanes plus capecitabine vs anthracyclines significantly improved OS outcomes (hazard ratio [HR] 0.56; 95% CI 0.36-0.87; probability for ranking the first 29%), whereas carboplatin/paclitaxel vs anthracyclines was the best regimen for improving DFS outcomes (HR 0.51; 95% CI 0.30-0.86; probability for ranking the first 41%).

Study details: Findings are from a network meta-analysis of 27 randomized phase 3 trials that compared adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in patients with resected, stage I-III TNBC.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Petrelli F et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected triple negative breast cancer patients: A network meta-analysis. Breast. 2022;67:8-13 (Dec 15). Doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.12.004

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), adding capecitabine to classic anthracycline/taxane-based adjuvant chemotherapy improved overall survival (OS) and carboplatin/paclitaxel was the most effective regimen for improving disease-free survival (DFS).

Major finding: Adjuvant chemotherapy with anthracyclines/taxanes plus capecitabine vs anthracyclines significantly improved OS outcomes (hazard ratio [HR] 0.56; 95% CI 0.36-0.87; probability for ranking the first 29%), whereas carboplatin/paclitaxel vs anthracyclines was the best regimen for improving DFS outcomes (HR 0.51; 95% CI 0.30-0.86; probability for ranking the first 41%).

Study details: Findings are from a network meta-analysis of 27 randomized phase 3 trials that compared adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in patients with resected, stage I-III TNBC.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Petrelli F et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected triple negative breast cancer patients: A network meta-analysis. Breast. 2022;67:8-13 (Dec 15). Doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.12.004

Overall survival improved with chemotherapy in ER-negative/HER2-negative, T1abN0 BC

Key clinical point: Treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival (OS) outcomes in patients with estrogen receptor-negative (ER−)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), T1abN0 breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 7.7 years, a significant improvement was observed in OS with vs without chemotherapy in the overall cohort of patients with T1abN0 BC (hazard ratio 0.35; P = .02), along with both subgroups of patients with T1a (log-rank P = .001) and T1b (P = .001) BC.

Study details: Findings are from a nationwide, retrospective cohort study including 296 patients with ER− /HER2−, T1abN0 BC, of which 79.4% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Danish Cancer Society, Denmark, and other sources. Some authors declared receiving personal fees, speaker honorarium, or research grants from various sources.

Source: Hassing CMS et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with ER-negative/HER2-negative, T1abN0 breast cancer: A nationwide study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 (Dec 28). Doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06839-2

Key clinical point: Treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival (OS) outcomes in patients with estrogen receptor-negative (ER−)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), T1abN0 breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 7.7 years, a significant improvement was observed in OS with vs without chemotherapy in the overall cohort of patients with T1abN0 BC (hazard ratio 0.35; P = .02), along with both subgroups of patients with T1a (log-rank P = .001) and T1b (P = .001) BC.

Study details: Findings are from a nationwide, retrospective cohort study including 296 patients with ER− /HER2−, T1abN0 BC, of which 79.4% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Danish Cancer Society, Denmark, and other sources. Some authors declared receiving personal fees, speaker honorarium, or research grants from various sources.

Source: Hassing CMS et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with ER-negative/HER2-negative, T1abN0 breast cancer: A nationwide study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 (Dec 28). Doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06839-2

Key clinical point: Treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival (OS) outcomes in patients with estrogen receptor-negative (ER−)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), T1abN0 breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 7.7 years, a significant improvement was observed in OS with vs without chemotherapy in the overall cohort of patients with T1abN0 BC (hazard ratio 0.35; P = .02), along with both subgroups of patients with T1a (log-rank P = .001) and T1b (P = .001) BC.

Study details: Findings are from a nationwide, retrospective cohort study including 296 patients with ER− /HER2−, T1abN0 BC, of which 79.4% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Danish Cancer Society, Denmark, and other sources. Some authors declared receiving personal fees, speaker honorarium, or research grants from various sources.

Source: Hassing CMS et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with ER-negative/HER2-negative, T1abN0 breast cancer: A nationwide study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 (Dec 28). Doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06839-2

ERBB2 mRNA expression predicts prognosis in trastuzumab emtansine-treated advanced HER2+ BC patients

Key clinical point: In patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+ or ERBB2+) breast cancer (BC) treated with trastuzumab emtansine, the pre-established levels of ERBB2 mRNA expression according to the HER2DX standardized assay served as an important prognostic biomarker in predicting survival outcomes.

Major finding: High, medium, and low levels of ERBB2 mRNA expression were associated with overall response rates of 56%, 29%, and 0%, respectively, with high ERBB2 mRNA expression being associated with both better progression-free survival (P < .001) and overall survival (P = .007) outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from a study including 87 patients with HER2+ advanced BC who received treatment with trastuzumab emtansine.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Hospital Clinic, Dipartimento di Scienze Chirurgiche, Oncologiche e Gastroenterologiche, University of Padova, Italy, and other sources. The authors declared serving as consultants; receiving advisory, lecture, or consulting fees; or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Brasó-Maristany F et al. HER2DX ERBB2 mRNA expression in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with T-DM1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022 (Dec 28). Doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac227

Key clinical point: In patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+ or ERBB2+) breast cancer (BC) treated with trastuzumab emtansine, the pre-established levels of ERBB2 mRNA expression according to the HER2DX standardized assay served as an important prognostic biomarker in predicting survival outcomes.

Major finding: High, medium, and low levels of ERBB2 mRNA expression were associated with overall response rates of 56%, 29%, and 0%, respectively, with high ERBB2 mRNA expression being associated with both better progression-free survival (P < .001) and overall survival (P = .007) outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from a study including 87 patients with HER2+ advanced BC who received treatment with trastuzumab emtansine.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Hospital Clinic, Dipartimento di Scienze Chirurgiche, Oncologiche e Gastroenterologiche, University of Padova, Italy, and other sources. The authors declared serving as consultants; receiving advisory, lecture, or consulting fees; or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Brasó-Maristany F et al. HER2DX ERBB2 mRNA expression in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with T-DM1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022 (Dec 28). Doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac227

Key clinical point: In patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+ or ERBB2+) breast cancer (BC) treated with trastuzumab emtansine, the pre-established levels of ERBB2 mRNA expression according to the HER2DX standardized assay served as an important prognostic biomarker in predicting survival outcomes.

Major finding: High, medium, and low levels of ERBB2 mRNA expression were associated with overall response rates of 56%, 29%, and 0%, respectively, with high ERBB2 mRNA expression being associated with both better progression-free survival (P < .001) and overall survival (P = .007) outcomes.

Study details: Findings are from a study including 87 patients with HER2+ advanced BC who received treatment with trastuzumab emtansine.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Hospital Clinic, Dipartimento di Scienze Chirurgiche, Oncologiche e Gastroenterologiche, University of Padova, Italy, and other sources. The authors declared serving as consultants; receiving advisory, lecture, or consulting fees; or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Brasó-Maristany F et al. HER2DX ERBB2 mRNA expression in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with T-DM1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022 (Dec 28). Doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac227

Addition of atezolizumab to carboplatin+paclitaxel improves pCR in stage II-III TNBC

Key clinical point: Addition of atezolizumab to carboplatin+paclitaxel in the neoadjuvant setting improved the pathological complete response (pCR) rate in patients with stage II-III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 6.6 months, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved pCR in the atezolizumab+chemotherapy vs chemotherapy-only group (55.6% vs 18.8%; P = .018). However, the increase in the percentage of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes was nominal and not significantly different between both groups (P = .36). Grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events were reported by 62.5% vs 57.8% of patients in the only chemotherapy vs atezolizumab+chemotherapy group, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 NCI-10013 study including 67 patients with previously untreated stage II and III TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant carboplatin+paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Some authors declared receiving research grants or having other financial or non-financial ties with several sources.

Source: Ademuyiwa FO et al. A randomized phase 2 study of neoadjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) - NCI 10013. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):134 (Dec 30). Doi: 10.1038/s41523-022-00500-3

Key clinical point: Addition of atezolizumab to carboplatin+paclitaxel in the neoadjuvant setting improved the pathological complete response (pCR) rate in patients with stage II-III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 6.6 months, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved pCR in the atezolizumab+chemotherapy vs chemotherapy-only group (55.6% vs 18.8%; P = .018). However, the increase in the percentage of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes was nominal and not significantly different between both groups (P = .36). Grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events were reported by 62.5% vs 57.8% of patients in the only chemotherapy vs atezolizumab+chemotherapy group, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 NCI-10013 study including 67 patients with previously untreated stage II and III TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant carboplatin+paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Some authors declared receiving research grants or having other financial or non-financial ties with several sources.

Source: Ademuyiwa FO et al. A randomized phase 2 study of neoadjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) - NCI 10013. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):134 (Dec 30). Doi: 10.1038/s41523-022-00500-3

Key clinical point: Addition of atezolizumab to carboplatin+paclitaxel in the neoadjuvant setting improved the pathological complete response (pCR) rate in patients with stage II-III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 6.6 months, a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved pCR in the atezolizumab+chemotherapy vs chemotherapy-only group (55.6% vs 18.8%; P = .018). However, the increase in the percentage of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes was nominal and not significantly different between both groups (P = .36). Grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events were reported by 62.5% vs 57.8% of patients in the only chemotherapy vs atezolizumab+chemotherapy group, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 NCI-10013 study including 67 patients with previously untreated stage II and III TNBC who were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant carboplatin+paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Some authors declared receiving research grants or having other financial or non-financial ties with several sources.

Source: Ademuyiwa FO et al. A randomized phase 2 study of neoadjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without atezolizumab in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) - NCI 10013. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):134 (Dec 30). Doi: 10.1038/s41523-022-00500-3

Gut enzymes fingered in some 5-ASA treatment failures

AURORA, COLO. – The therapeutic action of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), one of the most frequently prescribed drugs for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), can be defeated by enzymes that reside in the very gut that the drug is designed to treat.

“What we found is two gut microbial acetyltransferase families that were previously unknown to be participating in drug metabolism that directly inactivate the drug 5-ASA. It seems that in turn, having a subset of these microbial acetyltransferases is prospectively linked with treatment failure, and could potentially explain why some of these patients of ours fail on the drug,” Raaj S. Mehta, MD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

More than half of all patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA either lose their response to the drug or never respond to it at all, including some of his own patients, Dr. Mehta said.

There is an urgent need for a way to predict which patients will be likely to respond to 5-ASA and other drugs to treat IBD, he said.

The same old story

In the early 1990s, investigators at St. Radboud Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, studied cultured feces from patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA, and found in some patients that the drug was metabolized into N-acetyl-5-ASA. In an earlier, double-blind comparison trial in patients with idiopathic proctitis, the same investigators found N-acetyl-5-ASA to be “no better than placebo.”

“But prior to our work, we didn’t know which specific bacteria or enzymes performed this conversion ... of the drug, and we didn’t know if having these enzymes in your intestines or colon could explain why people are at risk for failing on 5-ASA,” Dr. Mehta said.

New evidence

Dr. Mehta and his colleagues first turned to the Human Microbiome Project 2, a cohort of 132 persons with IBD followed for 1 year each, with the goal of generating molecular profiles of host and microbial activity over time.

The patients provided stool samples about every 2 weeks, as well as blood and biopsy specimens, and reported details on their use of medications.

The investigators generated metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, genomic, and metabolomic profiles from the data, and then narrowed their focus to 45 participants who used 5-ASA and 34 who did not.

They found that “5-ASA has a major impact on the fecal metabolome,” with significant increases in fecal drug levels of both 5-ASA and the inactive metabolites, as well as more than 2,000 other metabolites.

Looking at the gemomics of gut microbiota, the investigators identified gene clusters in two superfamilies of enzymes, thiolases and acyl CoA N-acyltransferases. They identified 12 candidates.

To bolster their findings, they then expressed one gene from each superfamily in Escherichia coli and purified the protein. When they cocultured it with acetylCoA and 5-ASA, there was a greater than 25% conversion of the drug within 1 hour.

They also found that microbial thiolases appear to step outside of their normal roles to inactivate 5-ASA in a manner similar to that of an N-acetyltrasferase not found in persons with IBD.

Clinical relevance

To see whether their findings had clinical implications, the investigators conducted a case-cohort study nested within the Human Microbiome Project 2 cohort. They saw that, after adjusting for age, sex, IBD type, smoking, and N-acetyltransferase (NAT2) phenotype, 4 of the 12 acetyltranfserase candidates were associated with a roughly threefold increase in steroid use, suggesting that 5-ASA treatment had failed the patients.

“So then to take it one step further, we turned to the SPARC IBD cohort,” Dr. Mehta said.

SPARC IBD is an ongoing prospective cohort of patients who provide stool samples and detailed medication and symptom data.

They identified 208 cohort members who were on 5-ASA, were free of steroids at baseline, and who had fecal metabolomic data available. In this group, there were 60 cases of new corticosteroid prescriptions after about 8 months of follow-up.

The authors found that having three or four of the suspect acetyltransferases in gut microbiota was associated with a an overall odds ratio for 5-ASA treatment failure of 3.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.41-6.89).

“Taken together, I think this advances the idea of using the microbiome for personalized medicine in IBD,” Dr. Mehta said.

“Right now it’s an ideal outcome for a patient with [ulcerative colitis] to retain a robust remission on 5-ASA alone,” commented session moderator Michael J. Rosen, MD, MSCI, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., who was not involved in the study.

Asked in an interview whether the findings would be likely to change clinical practice, Dr. Rosen replied that “I think it’s fairly early stage, but I think it’s wonderful that they sort of rediscovered this older data and are modernizing it to understand why [5-ASA] may not work for some patients. It certainly seems like it might be a tractable approach to use the microbiome to personalize therapy and potentially increase the effectiveness of 5-ASA.”

The study was supported by grants from Pfizer, the National Institutes of Health, American College of Gastroenterology, and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Dr. Mehta disclosed that his team has filed a provisional patent application related to the work. Dr. Rosen reported no relevant conflict of interest.

AURORA, COLO. – The therapeutic action of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), one of the most frequently prescribed drugs for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), can be defeated by enzymes that reside in the very gut that the drug is designed to treat.

“What we found is two gut microbial acetyltransferase families that were previously unknown to be participating in drug metabolism that directly inactivate the drug 5-ASA. It seems that in turn, having a subset of these microbial acetyltransferases is prospectively linked with treatment failure, and could potentially explain why some of these patients of ours fail on the drug,” Raaj S. Mehta, MD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

More than half of all patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA either lose their response to the drug or never respond to it at all, including some of his own patients, Dr. Mehta said.

There is an urgent need for a way to predict which patients will be likely to respond to 5-ASA and other drugs to treat IBD, he said.

The same old story

In the early 1990s, investigators at St. Radboud Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, studied cultured feces from patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA, and found in some patients that the drug was metabolized into N-acetyl-5-ASA. In an earlier, double-blind comparison trial in patients with idiopathic proctitis, the same investigators found N-acetyl-5-ASA to be “no better than placebo.”

“But prior to our work, we didn’t know which specific bacteria or enzymes performed this conversion ... of the drug, and we didn’t know if having these enzymes in your intestines or colon could explain why people are at risk for failing on 5-ASA,” Dr. Mehta said.

New evidence

Dr. Mehta and his colleagues first turned to the Human Microbiome Project 2, a cohort of 132 persons with IBD followed for 1 year each, with the goal of generating molecular profiles of host and microbial activity over time.

The patients provided stool samples about every 2 weeks, as well as blood and biopsy specimens, and reported details on their use of medications.

The investigators generated metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, genomic, and metabolomic profiles from the data, and then narrowed their focus to 45 participants who used 5-ASA and 34 who did not.

They found that “5-ASA has a major impact on the fecal metabolome,” with significant increases in fecal drug levels of both 5-ASA and the inactive metabolites, as well as more than 2,000 other metabolites.

Looking at the gemomics of gut microbiota, the investigators identified gene clusters in two superfamilies of enzymes, thiolases and acyl CoA N-acyltransferases. They identified 12 candidates.

To bolster their findings, they then expressed one gene from each superfamily in Escherichia coli and purified the protein. When they cocultured it with acetylCoA and 5-ASA, there was a greater than 25% conversion of the drug within 1 hour.

They also found that microbial thiolases appear to step outside of their normal roles to inactivate 5-ASA in a manner similar to that of an N-acetyltrasferase not found in persons with IBD.

Clinical relevance

To see whether their findings had clinical implications, the investigators conducted a case-cohort study nested within the Human Microbiome Project 2 cohort. They saw that, after adjusting for age, sex, IBD type, smoking, and N-acetyltransferase (NAT2) phenotype, 4 of the 12 acetyltranfserase candidates were associated with a roughly threefold increase in steroid use, suggesting that 5-ASA treatment had failed the patients.

“So then to take it one step further, we turned to the SPARC IBD cohort,” Dr. Mehta said.

SPARC IBD is an ongoing prospective cohort of patients who provide stool samples and detailed medication and symptom data.

They identified 208 cohort members who were on 5-ASA, were free of steroids at baseline, and who had fecal metabolomic data available. In this group, there were 60 cases of new corticosteroid prescriptions after about 8 months of follow-up.

The authors found that having three or four of the suspect acetyltransferases in gut microbiota was associated with a an overall odds ratio for 5-ASA treatment failure of 3.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.41-6.89).

“Taken together, I think this advances the idea of using the microbiome for personalized medicine in IBD,” Dr. Mehta said.

“Right now it’s an ideal outcome for a patient with [ulcerative colitis] to retain a robust remission on 5-ASA alone,” commented session moderator Michael J. Rosen, MD, MSCI, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., who was not involved in the study.

Asked in an interview whether the findings would be likely to change clinical practice, Dr. Rosen replied that “I think it’s fairly early stage, but I think it’s wonderful that they sort of rediscovered this older data and are modernizing it to understand why [5-ASA] may not work for some patients. It certainly seems like it might be a tractable approach to use the microbiome to personalize therapy and potentially increase the effectiveness of 5-ASA.”

The study was supported by grants from Pfizer, the National Institutes of Health, American College of Gastroenterology, and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Dr. Mehta disclosed that his team has filed a provisional patent application related to the work. Dr. Rosen reported no relevant conflict of interest.

AURORA, COLO. – The therapeutic action of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), one of the most frequently prescribed drugs for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), can be defeated by enzymes that reside in the very gut that the drug is designed to treat.

“What we found is two gut microbial acetyltransferase families that were previously unknown to be participating in drug metabolism that directly inactivate the drug 5-ASA. It seems that in turn, having a subset of these microbial acetyltransferases is prospectively linked with treatment failure, and could potentially explain why some of these patients of ours fail on the drug,” Raaj S. Mehta, MD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

More than half of all patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA either lose their response to the drug or never respond to it at all, including some of his own patients, Dr. Mehta said.

There is an urgent need for a way to predict which patients will be likely to respond to 5-ASA and other drugs to treat IBD, he said.

The same old story

In the early 1990s, investigators at St. Radboud Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, studied cultured feces from patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA, and found in some patients that the drug was metabolized into N-acetyl-5-ASA. In an earlier, double-blind comparison trial in patients with idiopathic proctitis, the same investigators found N-acetyl-5-ASA to be “no better than placebo.”

“But prior to our work, we didn’t know which specific bacteria or enzymes performed this conversion ... of the drug, and we didn’t know if having these enzymes in your intestines or colon could explain why people are at risk for failing on 5-ASA,” Dr. Mehta said.

New evidence

Dr. Mehta and his colleagues first turned to the Human Microbiome Project 2, a cohort of 132 persons with IBD followed for 1 year each, with the goal of generating molecular profiles of host and microbial activity over time.

The patients provided stool samples about every 2 weeks, as well as blood and biopsy specimens, and reported details on their use of medications.

The investigators generated metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, genomic, and metabolomic profiles from the data, and then narrowed their focus to 45 participants who used 5-ASA and 34 who did not.

They found that “5-ASA has a major impact on the fecal metabolome,” with significant increases in fecal drug levels of both 5-ASA and the inactive metabolites, as well as more than 2,000 other metabolites.

Looking at the gemomics of gut microbiota, the investigators identified gene clusters in two superfamilies of enzymes, thiolases and acyl CoA N-acyltransferases. They identified 12 candidates.

To bolster their findings, they then expressed one gene from each superfamily in Escherichia coli and purified the protein. When they cocultured it with acetylCoA and 5-ASA, there was a greater than 25% conversion of the drug within 1 hour.

They also found that microbial thiolases appear to step outside of their normal roles to inactivate 5-ASA in a manner similar to that of an N-acetyltrasferase not found in persons with IBD.

Clinical relevance

To see whether their findings had clinical implications, the investigators conducted a case-cohort study nested within the Human Microbiome Project 2 cohort. They saw that, after adjusting for age, sex, IBD type, smoking, and N-acetyltransferase (NAT2) phenotype, 4 of the 12 acetyltranfserase candidates were associated with a roughly threefold increase in steroid use, suggesting that 5-ASA treatment had failed the patients.

“So then to take it one step further, we turned to the SPARC IBD cohort,” Dr. Mehta said.

SPARC IBD is an ongoing prospective cohort of patients who provide stool samples and detailed medication and symptom data.

They identified 208 cohort members who were on 5-ASA, were free of steroids at baseline, and who had fecal metabolomic data available. In this group, there were 60 cases of new corticosteroid prescriptions after about 8 months of follow-up.

The authors found that having three or four of the suspect acetyltransferases in gut microbiota was associated with a an overall odds ratio for 5-ASA treatment failure of 3.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.41-6.89).

“Taken together, I think this advances the idea of using the microbiome for personalized medicine in IBD,” Dr. Mehta said.

“Right now it’s an ideal outcome for a patient with [ulcerative colitis] to retain a robust remission on 5-ASA alone,” commented session moderator Michael J. Rosen, MD, MSCI, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., who was not involved in the study.

Asked in an interview whether the findings would be likely to change clinical practice, Dr. Rosen replied that “I think it’s fairly early stage, but I think it’s wonderful that they sort of rediscovered this older data and are modernizing it to understand why [5-ASA] may not work for some patients. It certainly seems like it might be a tractable approach to use the microbiome to personalize therapy and potentially increase the effectiveness of 5-ASA.”

The study was supported by grants from Pfizer, the National Institutes of Health, American College of Gastroenterology, and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Dr. Mehta disclosed that his team has filed a provisional patent application related to the work. Dr. Rosen reported no relevant conflict of interest.

AT CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

ER/PgR+ BC: Adjuvant exemestane+ovarian suppression reduces recurrence risk

Key clinical point: Exemestane plus ovarian function suppression (OFS) led to a greater reduction in recurrence risk than tamoxifen+OFS in premenopausal women with estrogen or progesterone receptor-positive (ER/PgR+) early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: There was a significant improvement in 12-year disease-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79; P < .001) and distant recurrence-free interval (HR 0.83; P = .03) with exemestane+OFS vs tamoxifen+OFS, with overall survival outcomes (90.1% vs 89.1%) being excellent in both treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from a combined analysis of the SOFT and TEXT trials including 4690 premenopausal women with ER/PgR+ early BC who were randomly assigned to receive OFS plus exemestane or tamoxifen.

Disclosures: The SOFT and TEXT are supported by ETOP IBCSG (European Thoracic Oncology Platform, International Breast Cancer Study Group) Partners Foundation, Switzerland. The authors declared serving as consultants or advisors or receiving honoraria, research funding, or travel and accommodation expenses from several sources.

Source: Pagani O, Walley BA, et al for the SOFT and TEXT Investigators and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (a division of ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation). Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer: Long-term follow-up of the combined TEXT and SOFT trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Dec 15). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01064

Key clinical point: Exemestane plus ovarian function suppression (OFS) led to a greater reduction in recurrence risk than tamoxifen+OFS in premenopausal women with estrogen or progesterone receptor-positive (ER/PgR+) early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: There was a significant improvement in 12-year disease-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79; P < .001) and distant recurrence-free interval (HR 0.83; P = .03) with exemestane+OFS vs tamoxifen+OFS, with overall survival outcomes (90.1% vs 89.1%) being excellent in both treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from a combined analysis of the SOFT and TEXT trials including 4690 premenopausal women with ER/PgR+ early BC who were randomly assigned to receive OFS plus exemestane or tamoxifen.

Disclosures: The SOFT and TEXT are supported by ETOP IBCSG (European Thoracic Oncology Platform, International Breast Cancer Study Group) Partners Foundation, Switzerland. The authors declared serving as consultants or advisors or receiving honoraria, research funding, or travel and accommodation expenses from several sources.

Source: Pagani O, Walley BA, et al for the SOFT and TEXT Investigators and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (a division of ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation). Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer: Long-term follow-up of the combined TEXT and SOFT trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Dec 15). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01064

Key clinical point: Exemestane plus ovarian function suppression (OFS) led to a greater reduction in recurrence risk than tamoxifen+OFS in premenopausal women with estrogen or progesterone receptor-positive (ER/PgR+) early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: There was a significant improvement in 12-year disease-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79; P < .001) and distant recurrence-free interval (HR 0.83; P = .03) with exemestane+OFS vs tamoxifen+OFS, with overall survival outcomes (90.1% vs 89.1%) being excellent in both treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from a combined analysis of the SOFT and TEXT trials including 4690 premenopausal women with ER/PgR+ early BC who were randomly assigned to receive OFS plus exemestane or tamoxifen.

Disclosures: The SOFT and TEXT are supported by ETOP IBCSG (European Thoracic Oncology Platform, International Breast Cancer Study Group) Partners Foundation, Switzerland. The authors declared serving as consultants or advisors or receiving honoraria, research funding, or travel and accommodation expenses from several sources.

Source: Pagani O, Walley BA, et al for the SOFT and TEXT Investigators and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (a division of ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation). Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer: Long-term follow-up of the combined TEXT and SOFT trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022 (Dec 15). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01064

Adding SBRT to sorafenib boosts survival in liver cancer

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to new findings.

The use of SBRT in this setting improved both overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS). There was no increase in adverse events with the addition of SBRT, and results trended toward a quality-of-life benefit at 6 months.

“This adds to the body of evidence for the role of external-beam radiation, bringing SBRT to the armamentarium of treatment options for patients – particularly those with locally advanced HCC and macrovascular invasion, especially if they are treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs],” said lead study author Laura A. Dawson, MD, a clinician scientist at the Cancer Clinical Research Unit, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto.

Dr. Dawson presented the findings at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023.

Approached for an outside comment, Mary Feng, MD, professor of radiation oncology at the University of California, San Francisco, said, “This study is really groundbreaking.”

She added that the investigators should be congratulated for executing this ambitious study with worldwide enrollment for a serious disease.

“There are very few studies demonstrating an overall survival benefit from radiation or any local control modality,” she told this news organization. She suggested that the survival benefit seen in this trial was “likely due to the high percentage of patients (74%) with macrovascular invasion, who stand to benefit the most from treatment.

“This study has established the standard of adding SBRT to patients who are treated with TKIs and raises the question of whether adding SBRT to immunotherapy would also result in a survival benefit. This next question must also be tested in a prospective clinical trial,” she said.

Study details

At the study’s inception, sorafenib was the standard of care for patients who were unable to undergo surgery, ablation, and/or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Dr. Dawson explained that sorafenib had been shown to improve median overall survival, although there was less benefit if macrovascular invasion was present.

“Integrating radiation strategies in HCC management has been a key question over the past few decades,” she said.

In the current study, Dr. Dawson and colleagues added SBRT to sorafenib. The cohort included 177 patients with new or recurrent HCC who were not candidates for surgery, ablation, or TACE. They were randomly assigned to receive either sorafenib 400 mg twice daily or to SBRT (27.5-50 Gy in five fractions) followed by sorafenib 200 mg twice daily; the dosage was then increased to 400 mg twice daily after 28 days.

SBRT improves outcomes

The original plan was to enroll 292 participants, but accrual closed early when the standard of care for systemic treatment of HCC changed following the results of the phase 3 IMbrave150 trial, which showed the superiority of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as frontline therapy for locally advanced or metastatic HCC. The closure of accrual was agreed upon by the investigators and the data safety monitoring committee, and their statistical analysis plan was revised accordingly. The study became time driven rather than event driven, she noted. This resulted in a decrease from 80% power to 65% power.

The median age of participants was 66 years (range, 27-84 years); 41% had hepatitis C, and 19% had hepatitis B or B/C. Additionally, 82% had Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C disease, and 74% had macrovascular invasion.

The median follow-up was 13.2 months overall and 33.7 months for living patients.

Median overall survival improved from 12.3 months with sorafenib alone to 15.8 months with the addition of SBRT to the regimen (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.77; one-sided P = .0554). A prespecified multivariable analysis showed that the combination therapy resulted in a statistically significant improvement in overall survival after adjustment for confounders (HR, 0.72; P = .042).

Similarly, median PFS also improved from 5.5 months with sorafenib alone to 9.2 months with SBRT and sorafenib (HR = 0.55; two-sided P = .0001).

With regard to safety, gastrointestinal bleeds occurred in 4% of patients in the combination arm, vs. 6% of those in the monotherapy arm. Overall, rates of treatment-related grade 3+ adverse events did not significantly differ between study arms (42% vs. 47%; P = .52). There were three grade 5 events; two in the sorafenib-only group and one in the SBRT/sorafenib group.

The researchers also evaluated quality of life (QoL). “Our hypothesis was that patients treated with SBRT and sorafenib would have improved quality of life 6 months after the start of treatment compared to sorafenib alone,” said Dr. Dawson.

About half (47%) of participants agreed to fill out QoL assessments, but baseline and 6-month data were available for only about 21% of participants. Although the numbers were considered too small to analyze statistically, substantial improvement was seen in the group that received combination therapy. A total of 10% of patients who received sorafenib reported improvement on the FACT-Hep score, vs. 35% of patients who received SBRT/sorafenib.

“As compared to sorafenib, SBRT improved overall survival and progression-free survival, with no observed increase in adverse events in patients with advanced HCC,” concluded Dr. Dawson.

Where does radiation fit?

Invited discussant Laura Goff, MD, associate professor of medicine, Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, Tenn., reiterated that SBRT given prior to sorafenib improved outcomes compared to sorafenib alone, and while not definitive, Quality and Outcomes Framework scores appeared to improve at 6 months for the combination arm. “This reassures our concerns about toxicity,” she said.

Dr. Goff pointed out that since the study closed early, owing to changes in standard of care for HCC, the question arises – where does radiation fit in the array of options now available for HCC?

“For one, sorafenib plus SBRT represents an intriguing first-line option for patients who cannot be treated with immunotherapy, such as those who experience a posttransplant recurrence,” Dr. Goff said. “There is also renewed interest in radiation therapy in liver-dominant HCC, and there is active investigation ongoing for a variety of combinations.”

Dr. Dawson reported relationships with Merck and Raysearch. Dr. Goff reported relationships with Agios, ASLAN, AstraZeneca, Basilea, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Genentech, Merck, and QED Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to new findings.

The use of SBRT in this setting improved both overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS). There was no increase in adverse events with the addition of SBRT, and results trended toward a quality-of-life benefit at 6 months.

“This adds to the body of evidence for the role of external-beam radiation, bringing SBRT to the armamentarium of treatment options for patients – particularly those with locally advanced HCC and macrovascular invasion, especially if they are treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs],” said lead study author Laura A. Dawson, MD, a clinician scientist at the Cancer Clinical Research Unit, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto.

Dr. Dawson presented the findings at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023.

Approached for an outside comment, Mary Feng, MD, professor of radiation oncology at the University of California, San Francisco, said, “This study is really groundbreaking.”

She added that the investigators should be congratulated for executing this ambitious study with worldwide enrollment for a serious disease.

“There are very few studies demonstrating an overall survival benefit from radiation or any local control modality,” she told this news organization. She suggested that the survival benefit seen in this trial was “likely due to the high percentage of patients (74%) with macrovascular invasion, who stand to benefit the most from treatment.

“This study has established the standard of adding SBRT to patients who are treated with TKIs and raises the question of whether adding SBRT to immunotherapy would also result in a survival benefit. This next question must also be tested in a prospective clinical trial,” she said.

Study details

At the study’s inception, sorafenib was the standard of care for patients who were unable to undergo surgery, ablation, and/or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Dr. Dawson explained that sorafenib had been shown to improve median overall survival, although there was less benefit if macrovascular invasion was present.

“Integrating radiation strategies in HCC management has been a key question over the past few decades,” she said.

In the current study, Dr. Dawson and colleagues added SBRT to sorafenib. The cohort included 177 patients with new or recurrent HCC who were not candidates for surgery, ablation, or TACE. They were randomly assigned to receive either sorafenib 400 mg twice daily or to SBRT (27.5-50 Gy in five fractions) followed by sorafenib 200 mg twice daily; the dosage was then increased to 400 mg twice daily after 28 days.

SBRT improves outcomes

The original plan was to enroll 292 participants, but accrual closed early when the standard of care for systemic treatment of HCC changed following the results of the phase 3 IMbrave150 trial, which showed the superiority of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as frontline therapy for locally advanced or metastatic HCC. The closure of accrual was agreed upon by the investigators and the data safety monitoring committee, and their statistical analysis plan was revised accordingly. The study became time driven rather than event driven, she noted. This resulted in a decrease from 80% power to 65% power.

The median age of participants was 66 years (range, 27-84 years); 41% had hepatitis C, and 19% had hepatitis B or B/C. Additionally, 82% had Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C disease, and 74% had macrovascular invasion.

The median follow-up was 13.2 months overall and 33.7 months for living patients.

Median overall survival improved from 12.3 months with sorafenib alone to 15.8 months with the addition of SBRT to the regimen (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.77; one-sided P = .0554). A prespecified multivariable analysis showed that the combination therapy resulted in a statistically significant improvement in overall survival after adjustment for confounders (HR, 0.72; P = .042).

Similarly, median PFS also improved from 5.5 months with sorafenib alone to 9.2 months with SBRT and sorafenib (HR = 0.55; two-sided P = .0001).

With regard to safety, gastrointestinal bleeds occurred in 4% of patients in the combination arm, vs. 6% of those in the monotherapy arm. Overall, rates of treatment-related grade 3+ adverse events did not significantly differ between study arms (42% vs. 47%; P = .52). There were three grade 5 events; two in the sorafenib-only group and one in the SBRT/sorafenib group.

The researchers also evaluated quality of life (QoL). “Our hypothesis was that patients treated with SBRT and sorafenib would have improved quality of life 6 months after the start of treatment compared to sorafenib alone,” said Dr. Dawson.

About half (47%) of participants agreed to fill out QoL assessments, but baseline and 6-month data were available for only about 21% of participants. Although the numbers were considered too small to analyze statistically, substantial improvement was seen in the group that received combination therapy. A total of 10% of patients who received sorafenib reported improvement on the FACT-Hep score, vs. 35% of patients who received SBRT/sorafenib.

“As compared to sorafenib, SBRT improved overall survival and progression-free survival, with no observed increase in adverse events in patients with advanced HCC,” concluded Dr. Dawson.

Where does radiation fit?

Invited discussant Laura Goff, MD, associate professor of medicine, Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, Tenn., reiterated that SBRT given prior to sorafenib improved outcomes compared to sorafenib alone, and while not definitive, Quality and Outcomes Framework scores appeared to improve at 6 months for the combination arm. “This reassures our concerns about toxicity,” she said.

Dr. Goff pointed out that since the study closed early, owing to changes in standard of care for HCC, the question arises – where does radiation fit in the array of options now available for HCC?

“For one, sorafenib plus SBRT represents an intriguing first-line option for patients who cannot be treated with immunotherapy, such as those who experience a posttransplant recurrence,” Dr. Goff said. “There is also renewed interest in radiation therapy in liver-dominant HCC, and there is active investigation ongoing for a variety of combinations.”

Dr. Dawson reported relationships with Merck and Raysearch. Dr. Goff reported relationships with Agios, ASLAN, AstraZeneca, Basilea, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Genentech, Merck, and QED Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to new findings.

The use of SBRT in this setting improved both overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS). There was no increase in adverse events with the addition of SBRT, and results trended toward a quality-of-life benefit at 6 months.

“This adds to the body of evidence for the role of external-beam radiation, bringing SBRT to the armamentarium of treatment options for patients – particularly those with locally advanced HCC and macrovascular invasion, especially if they are treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs],” said lead study author Laura A. Dawson, MD, a clinician scientist at the Cancer Clinical Research Unit, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto.

Dr. Dawson presented the findings at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2023.

Approached for an outside comment, Mary Feng, MD, professor of radiation oncology at the University of California, San Francisco, said, “This study is really groundbreaking.”

She added that the investigators should be congratulated for executing this ambitious study with worldwide enrollment for a serious disease.

“There are very few studies demonstrating an overall survival benefit from radiation or any local control modality,” she told this news organization. She suggested that the survival benefit seen in this trial was “likely due to the high percentage of patients (74%) with macrovascular invasion, who stand to benefit the most from treatment.

“This study has established the standard of adding SBRT to patients who are treated with TKIs and raises the question of whether adding SBRT to immunotherapy would also result in a survival benefit. This next question must also be tested in a prospective clinical trial,” she said.

Study details

At the study’s inception, sorafenib was the standard of care for patients who were unable to undergo surgery, ablation, and/or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Dr. Dawson explained that sorafenib had been shown to improve median overall survival, although there was less benefit if macrovascular invasion was present.

“Integrating radiation strategies in HCC management has been a key question over the past few decades,” she said.

In the current study, Dr. Dawson and colleagues added SBRT to sorafenib. The cohort included 177 patients with new or recurrent HCC who were not candidates for surgery, ablation, or TACE. They were randomly assigned to receive either sorafenib 400 mg twice daily or to SBRT (27.5-50 Gy in five fractions) followed by sorafenib 200 mg twice daily; the dosage was then increased to 400 mg twice daily after 28 days.

SBRT improves outcomes

The original plan was to enroll 292 participants, but accrual closed early when the standard of care for systemic treatment of HCC changed following the results of the phase 3 IMbrave150 trial, which showed the superiority of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as frontline therapy for locally advanced or metastatic HCC. The closure of accrual was agreed upon by the investigators and the data safety monitoring committee, and their statistical analysis plan was revised accordingly. The study became time driven rather than event driven, she noted. This resulted in a decrease from 80% power to 65% power.

The median age of participants was 66 years (range, 27-84 years); 41% had hepatitis C, and 19% had hepatitis B or B/C. Additionally, 82% had Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C disease, and 74% had macrovascular invasion.

The median follow-up was 13.2 months overall and 33.7 months for living patients.

Median overall survival improved from 12.3 months with sorafenib alone to 15.8 months with the addition of SBRT to the regimen (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.77; one-sided P = .0554). A prespecified multivariable analysis showed that the combination therapy resulted in a statistically significant improvement in overall survival after adjustment for confounders (HR, 0.72; P = .042).

Similarly, median PFS also improved from 5.5 months with sorafenib alone to 9.2 months with SBRT and sorafenib (HR = 0.55; two-sided P = .0001).

With regard to safety, gastrointestinal bleeds occurred in 4% of patients in the combination arm, vs. 6% of those in the monotherapy arm. Overall, rates of treatment-related grade 3+ adverse events did not significantly differ between study arms (42% vs. 47%; P = .52). There were three grade 5 events; two in the sorafenib-only group and one in the SBRT/sorafenib group.

The researchers also evaluated quality of life (QoL). “Our hypothesis was that patients treated with SBRT and sorafenib would have improved quality of life 6 months after the start of treatment compared to sorafenib alone,” said Dr. Dawson.

About half (47%) of participants agreed to fill out QoL assessments, but baseline and 6-month data were available for only about 21% of participants. Although the numbers were considered too small to analyze statistically, substantial improvement was seen in the group that received combination therapy. A total of 10% of patients who received sorafenib reported improvement on the FACT-Hep score, vs. 35% of patients who received SBRT/sorafenib.

“As compared to sorafenib, SBRT improved overall survival and progression-free survival, with no observed increase in adverse events in patients with advanced HCC,” concluded Dr. Dawson.

Where does radiation fit?

Invited discussant Laura Goff, MD, associate professor of medicine, Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, Tenn., reiterated that SBRT given prior to sorafenib improved outcomes compared to sorafenib alone, and while not definitive, Quality and Outcomes Framework scores appeared to improve at 6 months for the combination arm. “This reassures our concerns about toxicity,” she said.

Dr. Goff pointed out that since the study closed early, owing to changes in standard of care for HCC, the question arises – where does radiation fit in the array of options now available for HCC?

“For one, sorafenib plus SBRT represents an intriguing first-line option for patients who cannot be treated with immunotherapy, such as those who experience a posttransplant recurrence,” Dr. Goff said. “There is also renewed interest in radiation therapy in liver-dominant HCC, and there is active investigation ongoing for a variety of combinations.”

Dr. Dawson reported relationships with Merck and Raysearch. Dr. Goff reported relationships with Agios, ASLAN, AstraZeneca, Basilea, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Genentech, Merck, and QED Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ASCO GI 2023

Tips and tools to help you manage ADHD in children, adolescents

THE CASE

James B* is a 7-year-old Black child who presented to his primary care physician (PCP) for a well-child visit. During preventive health screening, James’ mother expressed concerns about his behavior, characterizing him as immature, aggressive, destructive, and occasionally self-loathing. She described him as physically uncoordinated, struggling to keep up with his peers in sports, and tiring after 20 minutes of activity. James slept 10 hours nightly but was often restless and snored intermittently. As a second grader, his academic achievement was not progressing, and he had become increasingly inattentive at home and at school. James’ mother offered several examples of his fighting with his siblings, noncompliance with morning routines, and avoidance of learning activities. Additionally, his mother expressed concern that James, as a Black child, might eventually be unfairly labeled as a problem child by his teachers or held back a grade level in school.

Although James did not have a family history of developmental delays or learning disorders, he had not met any milestones on time for gross or fine motor, language, cognitive, and social-emotional skills. James had a history of chronic otitis media, for which pressure equalizer tubes were inserted at age 2 years. He had not had any major physical injuries, psychological trauma, recent life transitions, or adverse childhood events. When asked, James’ mother acknowledged symptoms of maternal depression but alluded to faith-based reasons for not seeking treatment for herself.

James’ physical examination was unremarkable. His height, weight, and vitals were all within normal limits. However, he had some difficulty with verbal articulation and expression and showed signs of a possible vocal tic. Based on James’ presentation, his PCP suspected attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as neurodevelopmental delays.

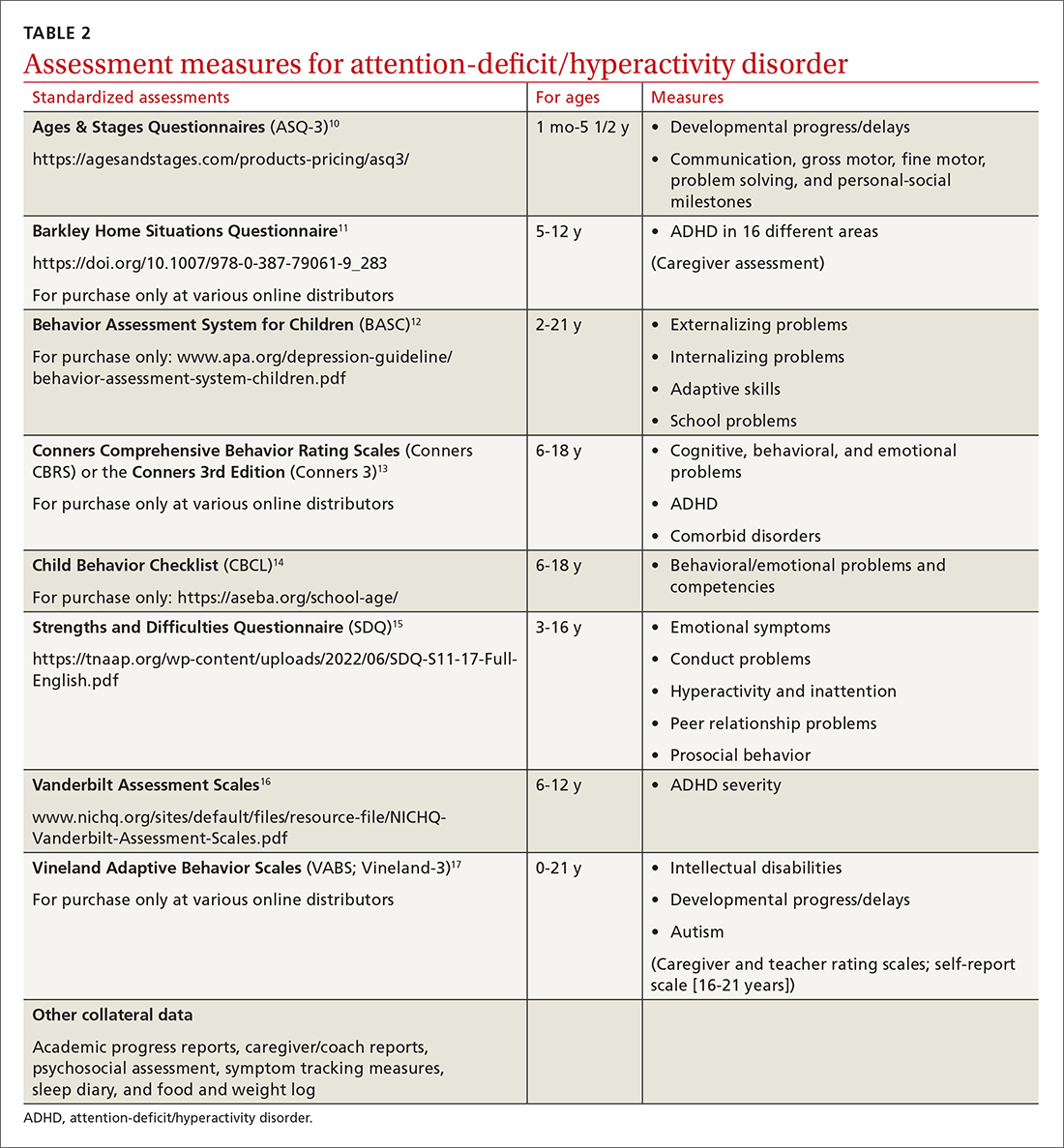

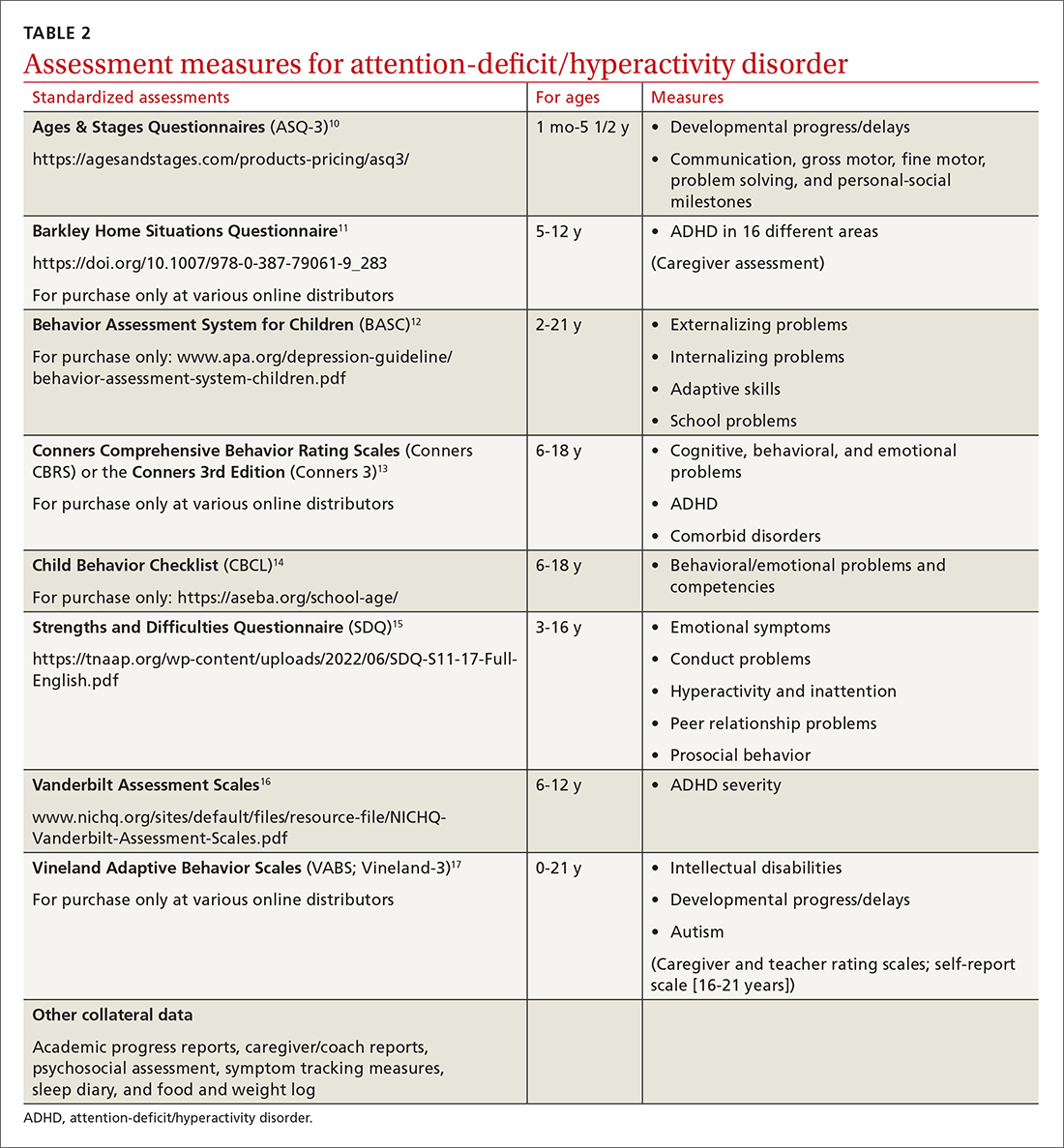

The PCP gave James’ mother the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to complete and the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for her and James’ teacher to fill out independently and return to the clinic. The PCP also instructed James’ mother on how to use a sleep diary to maintain a 1-month log of his sleep patterns and habits. The PCP consulted the integrated behavioral health clinician (IBHC; a clinical social worker embedded in the primary care clinic) and made a warm handoff for the IBHC to further assess James’ maladaptive behaviors and interactions.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

James is one of more than 6 million children, ages 3 to 17 years, in the United States who live with ADHD.1,2 ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder among children, and it affects multiple cognitive and behavioral domains throughout the lifespan.3 Children with ADHD often initially present in primary care settings; thus, PCPs are well positioned to diagnose the disorder and provide longitudinal treatment. This Behavioral Health Consult reviews clinical assessment and practice guidelines, as well as treatment recommendations applicable across different areas of influence—individual, family, community, and systems—for PCPs and IBHCs to use in managing ADHD in children.

ADHD features can vary by age and sex

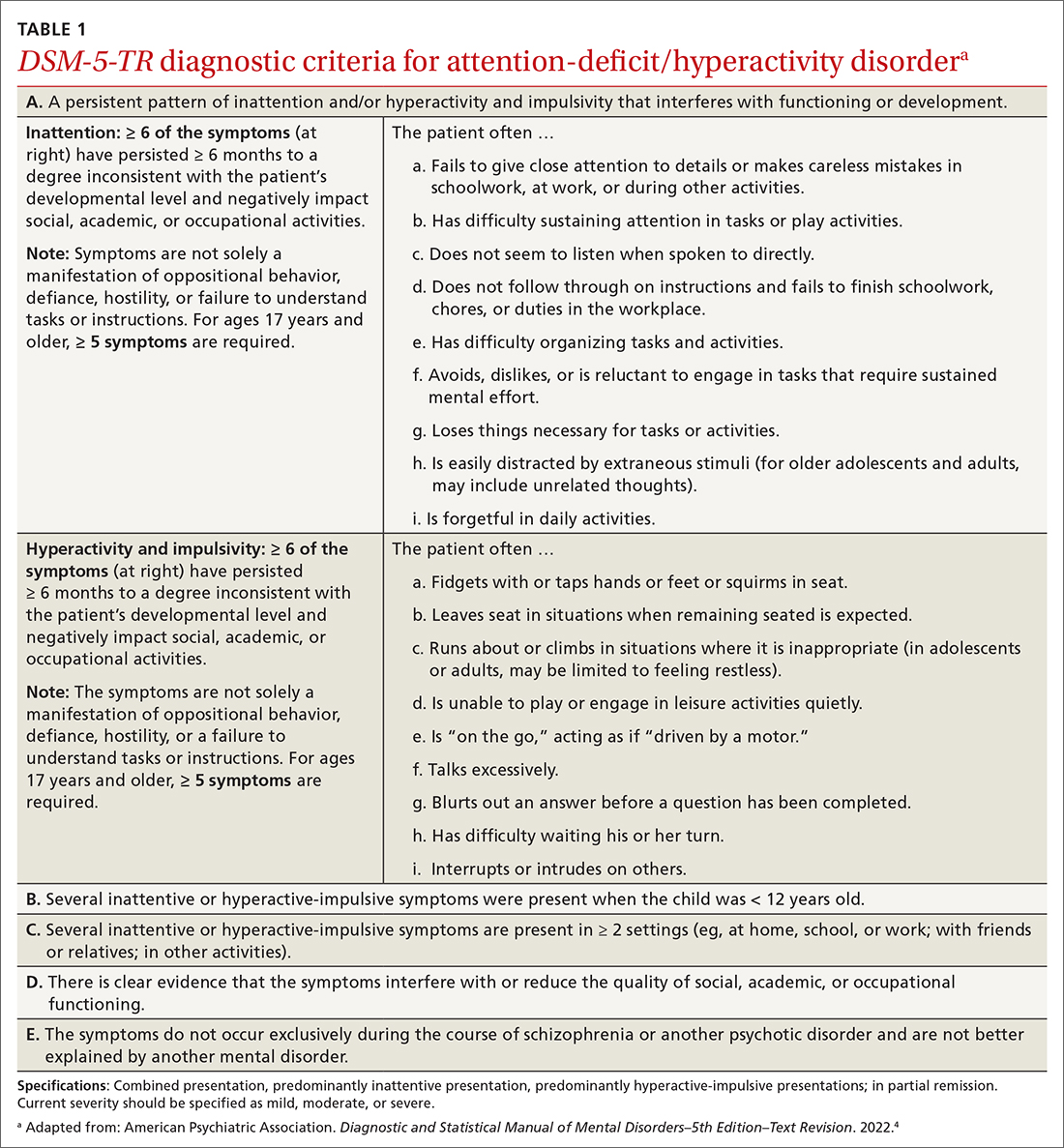

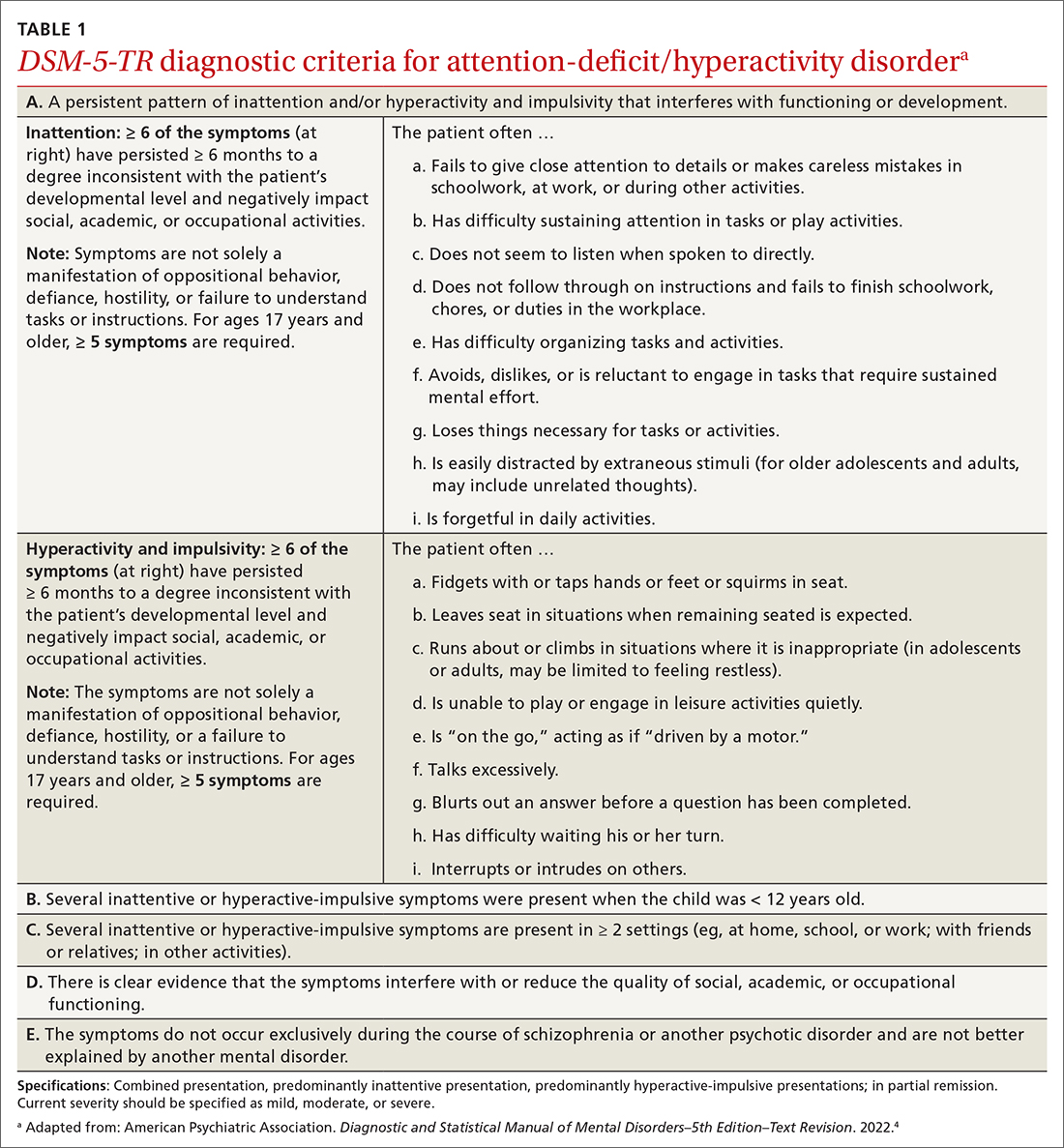

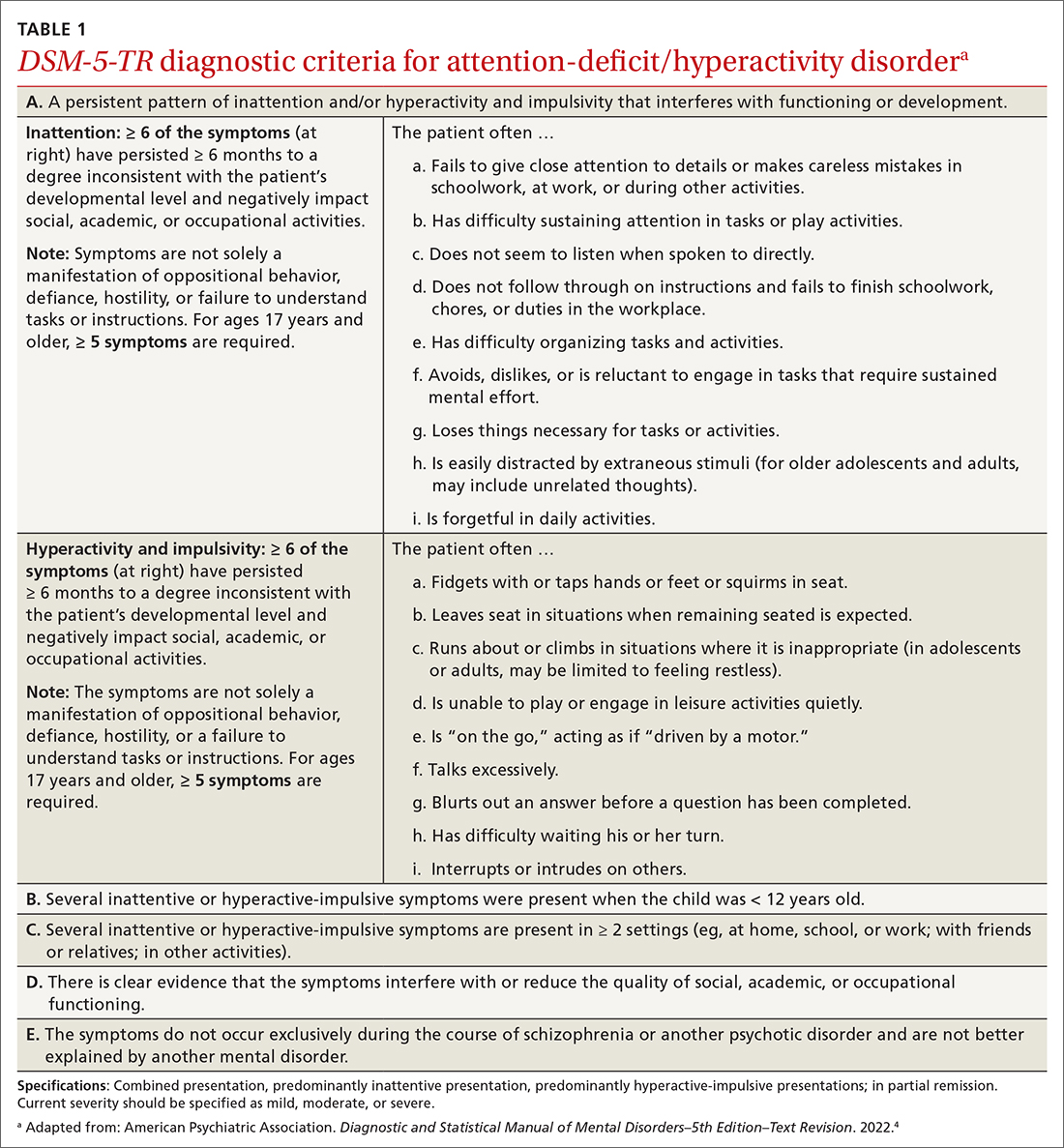

ADHD is a persistent pattern of inattention or hyperactivity and impulsivity interfering with functioning or development in childhood and functioning later in adulthood. ADHD symptoms manifest prior to age 12 years and must occur in 2 or more settings.4 Symptoms should not be better explained by another psychiatric disorder or occur exclusively during the course of another disorder (TABLE 1).4

The rate of heritability is high, with significant incidence among first-degree relatives.4 Children with ADHD show executive functioning deficits in 1 or more cognitive domains (eg, visuospatial, memory, inhibitions, decision making, and reward regulation).4,5 The prevalence of ADHD nationally is approximately 9.8% (2.2%, ages 3-5 years; 10%, ages 6-11 years; 13.2%, ages 12-17 years) in children and adolescents; worldwide prevalence is 7.2%.1,6 It persists among 2.6% to 6.8% of adults worldwide.7

Research has shown that boys ages 6 to 11 years are significantly more likely than girls to exhibit attention-getting, externalizing behaviors or conduct problems (eg, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disruption, aggression).1,6 On the other hand, girls ages 12 to 17 years tend to display internalized (eg, depressed mood, anxiety, low self-esteem) or inattentive behaviors, which clinicians and educators may assess as less severe and warranting fewer supportive measures.1

The prevalence of ADHD and its associated factors, which evolve through maturation, underscore the importance of persistent, patient-centered, and collaborative PCP and IBHC clinical management.

Continue to: Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

Begin with a screening tool, move to a clinical interview

When caregivers express concerns about their child’s behavior, focus, mood, learning, and socialization, consider initiating a multimodal evaluation for ADHD.5,8 Embarking on an ADHD assessment can require extended or multiple visits to arrive at the diagnosis, followed by still more visits to confirm a course of care and adjust medications. The integrative care approach described in the patient case and elaborated on later in this article can help facilitate assessment and treatment of ADHD.9

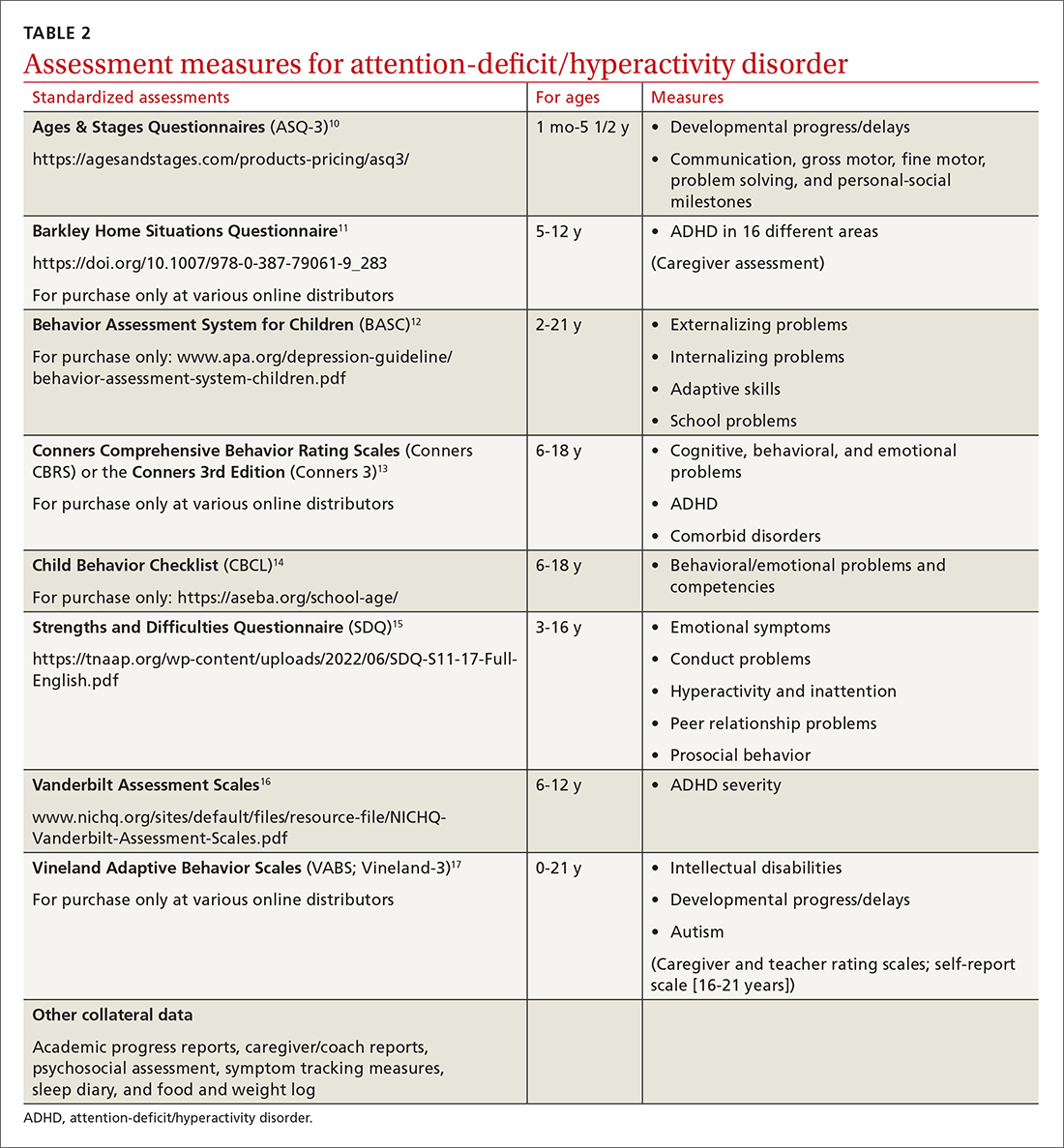

Signs of ADHD may be observed at initial screening using a tool such as the Ages & Stages Questionnaire (https://agesandstages.com/products-pricing/asq3/) to reveal indications of norm deviations or delays commensurate with ADHD.10 However, to substantiate the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision criteria for an accurate diagnosis,4 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines require a thorough clinical interview, administration of a standardized assessment tool, and review of objective reports in conjunction with a physical examination and psychosocial evaluation.6 Standardized measures of psychological, neurocognitive, and academic achievement reported by caregivers and collateral contacts (eg, teachers, counselors, coaches, care providers) are needed to maximize data objectivity and symptom accuracy across settings (TABLE 210-17). Additionally, periodic reassessment is recommended to validate changes in diagnostic subtype and treatment plans due to the chronic and dynamic nature of ADHD.

Consider comorbidities and alternate diagnoses

The diagnostic possibility of ADHD should also prompt consideration of other childhood disorders due to the high potential for comorbidities.4,6 In a 2016 study, approximately 64% of

Various medical disorders may manifest with similar signs or symptoms to ADHD, such as thyroid disorders, seizure disorders, adverse drug effects, anemia, genetic anomalies, and others.6,19

If there are behavioral concerns or developmental delays associated with tall stature for age or pubertal or testicular development anomalies, consult a geneticist and a developmental pediatrician for targeted testing and neurodevelopmental assessment, respectively. For example, ADHD is a common comorbidity among boys who also have XYY syndrome (Jacobs syndrome). However, due to the variability of symptoms and severity, XYY syndrome often goes undiagnosed, leaving a host of compounding pervasive and developmental problems untreated. Overall, more than two-thirds of patients with ADHD and a co-occurring condition are either inaccurately diagnosed or not referred for additional assessment and adjunct treatment.21

Continue to: Risks that arise over time

Risks that arise over time. As ADHD persists, adolescents are at greater risk for psychiatric comorbidities, suicidality, and functional impairments (eg, risky behaviors, occupational problems, truancy, delinquency, and poor self-esteem).4,8 Adolescents with internalized behaviors are more likely to experience comorbid depressive disorders with increased risk for self-harm.4,5,8 As adolescents age and their sense of autonomy increases, there is a tendency among those who have received a diagnosis of ADHD to minimize symptoms and decrease the frequency of routine clinic visits along with medication use and treatment compliance.3 Additionally, abuse, misuse, and misappropriation of stimulants among teens and young adults are commonplace.

Wide-scope, multidisciplinary evaluation and close clinical management reduce the potential for imprecise diagnoses, particularly at critical developmental junctures. AAP suggests that PCPs can treat mild and moderate cases of ADHD, but if the treating clinician does not have adequate training, experience, time, or clinical support to manage this condition, early referral is warranted.6

A guide to pharmacotherapy

Approximately 77% of children ages 2 to 17 years with a diagnosis of ADHD receive any form of treatment.2 Treatment for ADHD can include behavioral therapy and medication.2 AAP clinical practice guidelines caution against prescribing medications for children younger than 6 years, relying instead on caregiver-, teacher-, or clinician-administered behavioral strategies and parental training in behavioral modification. For children and adolescents between ages 6 and 18 years, first-line treatment includes pharmacotherapy balanced with behavioral therapy, academic modifications, and educational supports (eg, 504 Plan, individualized education plan [IEP]).6

Psychostimulants are preferred. These agents (eg, methylphenidate, amphetamine) remain the most efficacious class of medications to reduce hyperactivity and inattentiveness and to improve function. While long-acting psychostimulants are associated with better medication adherence and adverse-effect tolerance than are short-acting forms, the latter offer more flexibility in dosing. Start by titrating any stimulant to the lowest effective dose; reassess monthly until potential rebound effects stabilize.

Due to potential adverse effects of this class of medication, screen for any family history or personal risk for structural or electrical cardiac anomalies before starting pharmacotherapy. If any such risks exist, arrange for further cardiac evaluation before initiating medication.6 Adverse effects of stimulants include reduced appetite, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, anxiousness, parasomnia, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Continue to: Once medication is stabilized...

Once medication is stabilized, monitor treatment 2 to 3 times per year thereafter; watch for longer-term adverse effects such as weight loss, decreased growth rate, and psychiatric comorbidities including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s black box warning of increased risk for suicidality.5,6,22

Other options. The optimal duration of psychostimulant use remains debatable, as existing evidence does not support its long-term use (10 years) over other interventions, such as nonstimulants and nonmedicinal therapies.22 Although backed by less evidence, additional medications indicated for the treatment of ADHD include: (1) atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and (2) the selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, extended-release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine (third-line agent).22

Adverse effects of these FDA-approved medications are similar to those observed in stimulant medications. Evaluation of cardiac risks is recommended before starting nonstimulant medications. The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists may also be used as adjunct therapies to stimulants. Before stopping an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, taper the dosage slowly to avoid the risk for rebound hypertension.6,23 Given the wide variety of medication options and variability of effects, it may be necessary to try different medications as children grow and their symptoms and capacity to manage them change. Additional guidance on FDA-approved medications is available at www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com.

How multilevel care coordination can work

As with other chronic or developmental conditions, the treatment of ADHD requires an interdisciplinary perspective. Continuous, comprehensive case management can help patients overcome obstacles to wellness by balancing the resolution of problems with the development of resilience. Well-documented collaboration of subspecialists, educators, and other stakeholders engaged in ADHD care at multiple levels (individual, family, community, and health care system) increases the likelihood of meaningful, sustainable gains. Using a patient-centered medical home framework, IBHCs or other allied health professionals embedded in, or co-located with, primary care settings can be key to accessing evidence-based treatments that include: psycho-education and mindfulness-based stress reduction training for caregivers24,25; occupational,26 cognitive behavioral,27 or family therapies28,29; neuro-feedback; computer-based attention training; group- or community-based interventions; and academic and social supports.5,8

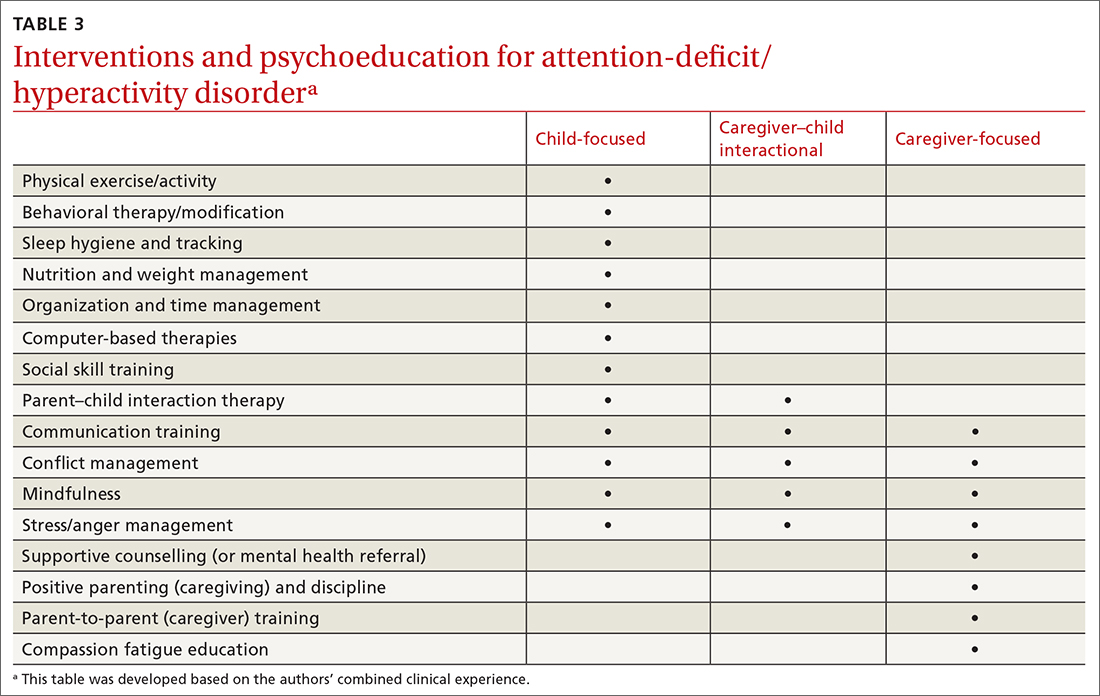

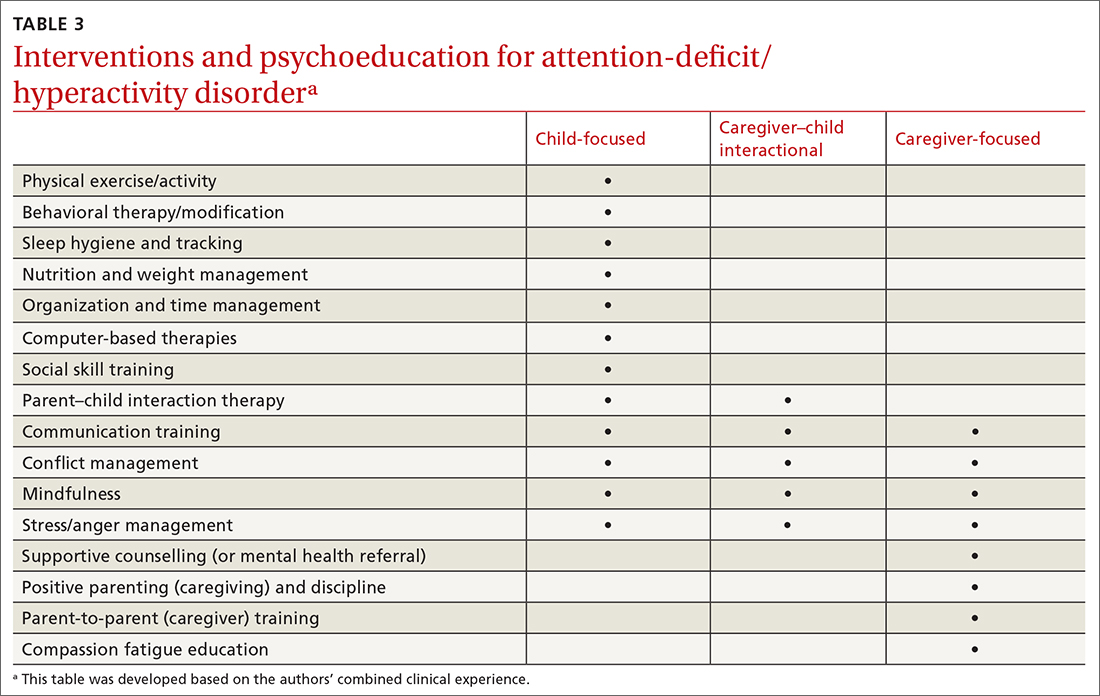

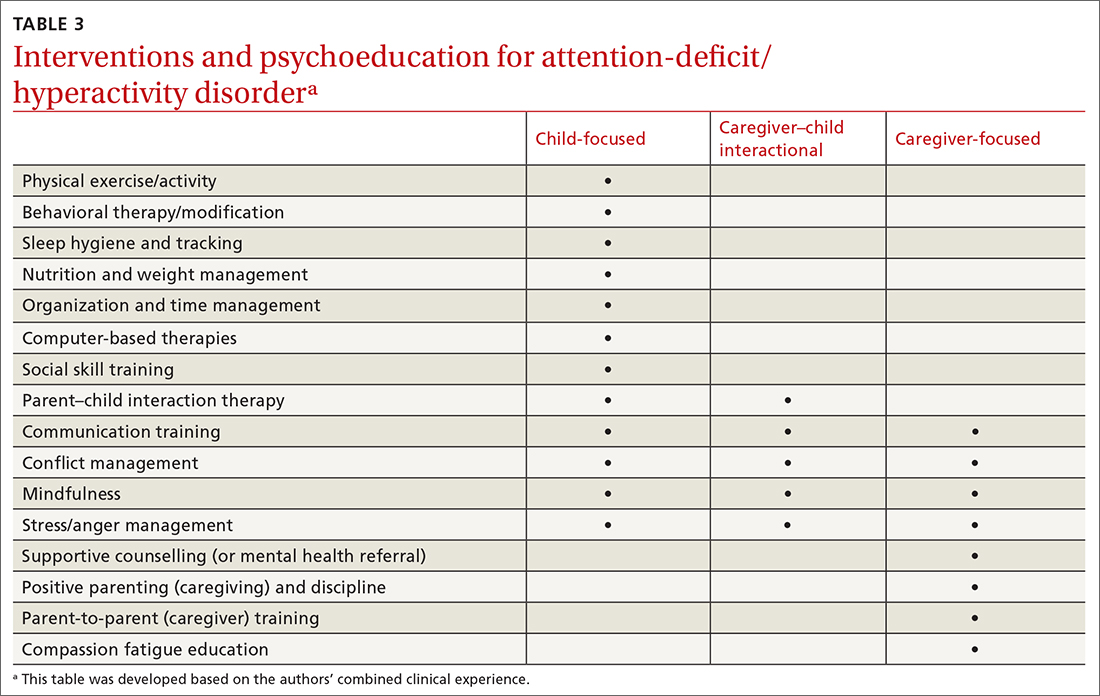

Treatment approaches that capitalize on children’s neurologic and psychological plasticity and fortify self-efficacy with developmentally appropriate tools empower them to surmount ADHD symptoms over time.23 Facilitating children’s resilience within a developmental framework and health system’s capacities with socio-culturally relevant approaches, consultation, and research can optimize outcomes and mitigate pervasiveness into adulthood. While the patient is at the center of treatment, it is important to consider the family, school, and communities in which the child lives, learns, and plays. PCPs and IBHCs together can consider a “try and track” method to follow progress, changes, and outcomes over time. With this method, the physician can employ approaches that focus on the patient, caregiver, or the caregiver–child interaction (TABLE 3).

Continue to: Assess patients' needs and the resources available

Assess patients’ needs and the resources available throughout the system of care beyond the primary care setting. Stay abreast of hospital policies, health care insurance coverage, and community- and school-based health programs, and any gaps in adequate and equitable assessment and treatment. For example, while clinical recommendations include psychiatric care, health insurance availability or limits in coverage may dissuade caregivers from seeking help or limit initial or long-term access to resources for help.30 Integrating or advocating for clinic support resources or staffing to assist patients in navigating and mitigating challenges may lessen the management burden and increase the likelihood and longevity of favorable health outcomes.

Steps to ensuring health care equity

Among children of historically marginalized and racial and ethnic minority groups or those of populations affected by health disparities, ADHD symptoms and needs are often masked by structural biases that lead to inequitable care and outcomes, as well as treatment misprioritization or delays.31 In particular, evidence has shown that recognition and diagnostic specificity of ADHD and comorbidities, not prevalence, vary more widely among minority than among nonminority populations,32 contributing to the 23% of children with ADHD who receive no treatment at all.2

Understand caregiver concerns. This diagnosis discrepancy is correlated with symptom rating sensitivities (eg, reliability, perception, accuracy) among informants and how caregivers observe, perceive, appreciate, understand, and report behaviors. This discrepancy is also related to cultural belief differences, physician–patient communication variants, and a litany of other socioeconomic determinants.2,4,31 Caregivers from some cultural, ethnic, or socioeconomic backgrounds may be doubtful of psychiatric assessment, diagnoses, treatment, or medication, and that can impact how children are engaged in clinical and educational settings from the outset.31 In the case we described, James’ mother was initially hesitant to explore psychotropic medications and was concerned about stigmatization within the school system. She also seemed to avoid psychiatric treatment for her own depressive symptoms due to cultural and religious beliefs.

Health care provider concerns. Some PCPs may hesitate to explore medications due to limited knowledge and skill in dosing and titrating based on a child’s age, stage, and symptoms, and a perceived lack of competence in managing ADHD. This, too, can indirectly perpetuate existing health disparities. Furthermore, ADHD symptoms may be deemed a secondary or tertiary concern if other complex or urgent medical or undifferentiated developmental problems manifest.

Compounding matters is the limited dissemination of empiric research articles (including randomized controlled trials with representative samples) and limited education on the effectiveness and safety of psychopharmacologic interventions across the lifespan and different cultural and ethnic groups.4 Consequently, patients who struggle with unmanaged ADHD symptoms are more likely to have chronic mental health disorders, maladaptive behaviors, and other co-occurring conditions contributing to the complexity of individual needs, health care burdens, or justice system involvement; this is particularly true for those of racial and ethnic minorities.33

Continue to: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic