User login

Mothers in medicine: What can we learn when worlds collide?

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Across all industries, studies by the U.S. Department of Labor have shown that women, on average, earn 83.7 percent of what their male peers earn. While a lot has been written about the struggles women face in medicine, there have been decidedly fewer analyses that focus on women who choose to become mothers while working in medicine.

I’ve been privileged to work with medical students and residents for the last 8 years as the director of graduate and medical student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. Often, the women I see as patients speak about their struggles with the elusive goal of “having it all.” While both men and women in medicine have difficulty maintaining a work-life balance, I’ve learned, both personally and professionally, that many women face a unique set of challenges.

No matter what their professional status, our society often views a woman as the default parent. For example, the teacher often calls the mothers first. The camp nurse calls me first, not my husband, when our child scrapes a knee. After-school play dates are arranged by the mothers, not fathers.

But mothers also bring to medicine a wealth of unique experiences, ideas, and viewpoints. They learn firsthand how to foster affect regulation and frustration tolerance in their kids and become efficient at managing the constant, conflicting tug of war of demands.

Some may argue that, over time, women end up earning significantly less than their male counterparts because they leave the workforce while on maternity leave, ultimately delaying their upward career progression. It’s likely a much more complex problem. Many of my patients believe that, in our male-dominated society (and workforce), women are punished for being aggressive or stating bold opinions, while men are rewarded for the same actions. While a man may sound forceful and in charge, a women will likely be thought of as brusque and unappreciative.

Outside of work, many women may have more on their plate. A 2020 Gallup poll of more than 3,000 heterosexual couples found that women are responsible for the majority of household chores. Women continue to handle more of the emotional labor within their families, regardless of income, age, or professional status. This is sometimes called the “Mental Load’ or “Second Shift.” As our society continues to view women as the default parent for childcare, medical issues, and overarching social and emotional tasks vital to raising happy, healthy children, the struggle a female medical professional feels is palpable.

Raising kids requires a parent to consistently dole out control, predictability, and reassurance for a child to thrive. Good limit and boundary setting leads to healthy development from a young age.

Psychiatric patients (and perhaps all patients) also require control, predictability, and reassurance from their doctor. The lessons learned in being a good mother can be directly applied in patient care, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of this relationship continues to grow more powerful as a woman’s children grow and her career matures.

Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s idea of a “good enough” mother cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach. Women who self-select into the world of medicine often hold themselves to a higher standard than “good enough.” Acknowledging that the demands from both home and work will fluctuate is key to achieving success both personally and professionally, and lessons from home can and should be utilized to become a more effective physician. The notion of having it all, and the definition of success, must evolve over time.

Dr. Maymind is director of medical and graduate student mental health at Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine in Mt. Laurel, N.J. She has no relevant disclosures.

Lymphoma specialist to lead MD Anderson’s cancer medicine division

“My research uncovered a series of physicians who served as ‘clinical champions’ and dramatically sped the process of drug development,” Dr. Flowers recalled in an interview. “This early career research inspired me to become the type of clinical champion that I uncovered.”

Over his career, hematologist-oncologist Dr. Flowers has developed lifesaving therapies for lymphoma, which has transformed into a highly treatable and even curable disease. He’s listed as a coauthor of hundreds of peer-reviewed cancer studies, reports, and medical society guidelines. And he’s revealed stark disparities in blood cancer care: His research shows that non-White patients suffer from worse outcomes, regardless of factors like income and insurance coverage.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, recently named physician-scientist Dr. Flowers as division head of cancer medicine, a position he’s held on an interim basis. As of Sept. 1, he will permanently oversee 300 faculty and more than 2,000 staff members.

A running start in Seattle

For Dr. Flowers, track and field is a sport that runs in the family. His grandfather was a top runner in both high school and college, and both Dr. Flowers and his brother ran competitively in Seattle, where they grew up. But Dr. Flowers chose a career in oncology, earning a medical degree at Stanford and master’s degrees at both Stanford and the University of Washington, Seattle.

The late Kenneth Melmon, MD, a groundbreaking pharmacologist, was a major influence. “He was one of the first people that I met when I began as an undergraduate at Stanford. We grew to be long-standing friends, and he demonstrated what outstanding mentorship looks like. In our research collaboration, we investigated the work of Dr. Gertrude Elion and Dr. George Hitchings involving the translation of pharmacological data from cellular and animal models to clinically useful drugs including 6-mercaptopurine, allopurinol, azathioprine, acyclovir, and zidovudine.”

The late Oliver Press, MD, a blood cancer specialist, inspired Dr. Flower’s interest in lymphoma. “I began work with him during an internship at the University of Washington. Ollie was a great inspiration and a key leader in the development of innovative therapies for lymphoma. He embodied the role of a clinical champion translating work in radioimmunotherapy to new therapeutics for patients with lymphomas. Working with him ultimately led me to pursue a career in hematology and oncology with a focus on the care for patients with lymphomas.”

Career blooms as lymphoma care advances

Dr. Flowers went on to Emory University, Atlanta, where he served as scientific director of the Research Informatics Shared Resource and a faculty member in the department of biomedical informatics. “I applied my training in informatics and my clinical expertise to support active grants from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund for Innovation in Regulatory Science and from the National Cancer Institute to develop informatics tools for pathology image analysis and prognostic modeling.”

For 13 years, he also served the Winship Cancer Institute as director of the Emory Healthcare lymphoma program (where his patients included Kansas City Chiefs football star Eric Berry), and for 4 years as scientific director of research informatics. Meanwhile, Dr. Flowers helped develop national practice guidelines for the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Radiology. He also chaired the ASCO guideline on management of febrile neutropenia.

In 2019, MD Anderson hired Dr. Flowers as chair of the department of lymphoma/myeloma. A year later, he was appointed division head ad interim for cancer medicine.

“Chris is a unique leader who expertly combines mentorship, sponsorship, and bidirectional open, honest communication,” said Sairah Ahmed, MD, associate professor of lymphoma at MD Anderson. “He doesn’t just empower his team to reach their goals. He also inspires those around him to turn vision into reality.”

As Dr. Flowers noted, many patients with lymphoma are now able to recover and live normal lives. He himself played a direct role himself in boosting lifespans.

“I have been fortunate to play a role in the development of several treatments that have led to advances in first-line therapy for patients with aggressive lymphomas. I partnered with others at MD Anderson, including Dr. Sattva Neelapu and Dr. Jason Westin, who have developed novel therapies like chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for patients with relapse lymphomas,” he said. “Leaders in the field at MD Anderson like Dr. Michael Wang have developed new oral treatments for patients with rare lymphoma subtypes like mantle cell lymphoma. Other colleagues such as Dr. Nathan Fowler and Dr. Loretta Nastoupil have focused on the care for patients with indolent lymphomas and developed less-toxic therapies that are now in common use.”

Exposing the disparities in blood cancer care

Dr. Flowers, who’s African American, has also been a leader in health disparity research. In 2016, for example, he was coauthor of a study into non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that revealed that Blacks in the United States have dramatically lower survival rates than Whites. The 10-year survival rate for Black women with chronic lymphocytic leukemia was just 47%, for example, compared with 66% for White females. “Although incidence rates of lymphoid neoplasms are generally higher among Whites, Black men tend to have poorer survival,” Dr. Flowers and colleagues wrote.

In a 2021 report for the ASCO Educational Book, Dr. Flowers and hematologist-oncologist Demetria Smith-Graziani, MD, now with Emory University, explored disparities across blood cancers and barriers to minority enrollment in clinical trials. “Some approaches that clinicians can apply to address these disparities include increasing systems-level awareness, improving access to care, and reducing biases in clinical setting,” the authors wrote.

Luis Malpica Castillo, MD, assistant professor of lymphoma at MD Anderson Cancer Center, lauded the work of Dr. Flowers in expanding opportunities for minority patients with the disease.

“During the past years, Dr. Flowers’ work has not only had a positive impact on the Texan community, but minority populations living with cancer in the United States and abroad,” he said. “Currently, we are implementing cancer care networks aimed to increase diversity in clinical trials by enrolling a larger number of Hispanic and African American patients, who otherwise may not have benefited from novel therapies. The ultimate goal is to provide high-quality care to all patients living with cancer.”

In addition to his research work, Dr. Flowers is an advocate for diversity within the hematology community. He’s a founding member and former chair of the American Society of Hematology’s Committee on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (formerly the Committee on Promoting Diversity), and he helped develop the society’s Minority Recruitment Initiative.

What’s next for Dr. Flowers? For one, he plans to continue working as a mentor; he received the ASH Mentor Award in honor of his service in 2022. “I am strongly committed to increasing the number of tenure-track investigators trained in clinical and translational cancer research and to promote their career development.”

And he looks forward to helping develop MD Anderson’s recently announced $2.5 billion hospital in Austin. “This will extend the exceptional care that we provide as the No. 1 cancer center in the United States,” he said. “It will also create new opportunities for research and collaboration with experts at UT Austin.”

When he’s not in clinic, Dr. Flowers embraces his lifelong love of speeding through life on his own two feet. He’s even inspired his children to share his passion. “I run most days of the week,” he said. “Running provides a great opportunity to think and process new research ideas, work through leadership challenges, and sometimes just to relax and let go of the day.”

“My research uncovered a series of physicians who served as ‘clinical champions’ and dramatically sped the process of drug development,” Dr. Flowers recalled in an interview. “This early career research inspired me to become the type of clinical champion that I uncovered.”

Over his career, hematologist-oncologist Dr. Flowers has developed lifesaving therapies for lymphoma, which has transformed into a highly treatable and even curable disease. He’s listed as a coauthor of hundreds of peer-reviewed cancer studies, reports, and medical society guidelines. And he’s revealed stark disparities in blood cancer care: His research shows that non-White patients suffer from worse outcomes, regardless of factors like income and insurance coverage.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, recently named physician-scientist Dr. Flowers as division head of cancer medicine, a position he’s held on an interim basis. As of Sept. 1, he will permanently oversee 300 faculty and more than 2,000 staff members.

A running start in Seattle

For Dr. Flowers, track and field is a sport that runs in the family. His grandfather was a top runner in both high school and college, and both Dr. Flowers and his brother ran competitively in Seattle, where they grew up. But Dr. Flowers chose a career in oncology, earning a medical degree at Stanford and master’s degrees at both Stanford and the University of Washington, Seattle.

The late Kenneth Melmon, MD, a groundbreaking pharmacologist, was a major influence. “He was one of the first people that I met when I began as an undergraduate at Stanford. We grew to be long-standing friends, and he demonstrated what outstanding mentorship looks like. In our research collaboration, we investigated the work of Dr. Gertrude Elion and Dr. George Hitchings involving the translation of pharmacological data from cellular and animal models to clinically useful drugs including 6-mercaptopurine, allopurinol, azathioprine, acyclovir, and zidovudine.”

The late Oliver Press, MD, a blood cancer specialist, inspired Dr. Flower’s interest in lymphoma. “I began work with him during an internship at the University of Washington. Ollie was a great inspiration and a key leader in the development of innovative therapies for lymphoma. He embodied the role of a clinical champion translating work in radioimmunotherapy to new therapeutics for patients with lymphomas. Working with him ultimately led me to pursue a career in hematology and oncology with a focus on the care for patients with lymphomas.”

Career blooms as lymphoma care advances

Dr. Flowers went on to Emory University, Atlanta, where he served as scientific director of the Research Informatics Shared Resource and a faculty member in the department of biomedical informatics. “I applied my training in informatics and my clinical expertise to support active grants from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund for Innovation in Regulatory Science and from the National Cancer Institute to develop informatics tools for pathology image analysis and prognostic modeling.”

For 13 years, he also served the Winship Cancer Institute as director of the Emory Healthcare lymphoma program (where his patients included Kansas City Chiefs football star Eric Berry), and for 4 years as scientific director of research informatics. Meanwhile, Dr. Flowers helped develop national practice guidelines for the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Radiology. He also chaired the ASCO guideline on management of febrile neutropenia.

In 2019, MD Anderson hired Dr. Flowers as chair of the department of lymphoma/myeloma. A year later, he was appointed division head ad interim for cancer medicine.

“Chris is a unique leader who expertly combines mentorship, sponsorship, and bidirectional open, honest communication,” said Sairah Ahmed, MD, associate professor of lymphoma at MD Anderson. “He doesn’t just empower his team to reach their goals. He also inspires those around him to turn vision into reality.”

As Dr. Flowers noted, many patients with lymphoma are now able to recover and live normal lives. He himself played a direct role himself in boosting lifespans.

“I have been fortunate to play a role in the development of several treatments that have led to advances in first-line therapy for patients with aggressive lymphomas. I partnered with others at MD Anderson, including Dr. Sattva Neelapu and Dr. Jason Westin, who have developed novel therapies like chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for patients with relapse lymphomas,” he said. “Leaders in the field at MD Anderson like Dr. Michael Wang have developed new oral treatments for patients with rare lymphoma subtypes like mantle cell lymphoma. Other colleagues such as Dr. Nathan Fowler and Dr. Loretta Nastoupil have focused on the care for patients with indolent lymphomas and developed less-toxic therapies that are now in common use.”

Exposing the disparities in blood cancer care

Dr. Flowers, who’s African American, has also been a leader in health disparity research. In 2016, for example, he was coauthor of a study into non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that revealed that Blacks in the United States have dramatically lower survival rates than Whites. The 10-year survival rate for Black women with chronic lymphocytic leukemia was just 47%, for example, compared with 66% for White females. “Although incidence rates of lymphoid neoplasms are generally higher among Whites, Black men tend to have poorer survival,” Dr. Flowers and colleagues wrote.

In a 2021 report for the ASCO Educational Book, Dr. Flowers and hematologist-oncologist Demetria Smith-Graziani, MD, now with Emory University, explored disparities across blood cancers and barriers to minority enrollment in clinical trials. “Some approaches that clinicians can apply to address these disparities include increasing systems-level awareness, improving access to care, and reducing biases in clinical setting,” the authors wrote.

Luis Malpica Castillo, MD, assistant professor of lymphoma at MD Anderson Cancer Center, lauded the work of Dr. Flowers in expanding opportunities for minority patients with the disease.

“During the past years, Dr. Flowers’ work has not only had a positive impact on the Texan community, but minority populations living with cancer in the United States and abroad,” he said. “Currently, we are implementing cancer care networks aimed to increase diversity in clinical trials by enrolling a larger number of Hispanic and African American patients, who otherwise may not have benefited from novel therapies. The ultimate goal is to provide high-quality care to all patients living with cancer.”

In addition to his research work, Dr. Flowers is an advocate for diversity within the hematology community. He’s a founding member and former chair of the American Society of Hematology’s Committee on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (formerly the Committee on Promoting Diversity), and he helped develop the society’s Minority Recruitment Initiative.

What’s next for Dr. Flowers? For one, he plans to continue working as a mentor; he received the ASH Mentor Award in honor of his service in 2022. “I am strongly committed to increasing the number of tenure-track investigators trained in clinical and translational cancer research and to promote their career development.”

And he looks forward to helping develop MD Anderson’s recently announced $2.5 billion hospital in Austin. “This will extend the exceptional care that we provide as the No. 1 cancer center in the United States,” he said. “It will also create new opportunities for research and collaboration with experts at UT Austin.”

When he’s not in clinic, Dr. Flowers embraces his lifelong love of speeding through life on his own two feet. He’s even inspired his children to share his passion. “I run most days of the week,” he said. “Running provides a great opportunity to think and process new research ideas, work through leadership challenges, and sometimes just to relax and let go of the day.”

“My research uncovered a series of physicians who served as ‘clinical champions’ and dramatically sped the process of drug development,” Dr. Flowers recalled in an interview. “This early career research inspired me to become the type of clinical champion that I uncovered.”

Over his career, hematologist-oncologist Dr. Flowers has developed lifesaving therapies for lymphoma, which has transformed into a highly treatable and even curable disease. He’s listed as a coauthor of hundreds of peer-reviewed cancer studies, reports, and medical society guidelines. And he’s revealed stark disparities in blood cancer care: His research shows that non-White patients suffer from worse outcomes, regardless of factors like income and insurance coverage.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, recently named physician-scientist Dr. Flowers as division head of cancer medicine, a position he’s held on an interim basis. As of Sept. 1, he will permanently oversee 300 faculty and more than 2,000 staff members.

A running start in Seattle

For Dr. Flowers, track and field is a sport that runs in the family. His grandfather was a top runner in both high school and college, and both Dr. Flowers and his brother ran competitively in Seattle, where they grew up. But Dr. Flowers chose a career in oncology, earning a medical degree at Stanford and master’s degrees at both Stanford and the University of Washington, Seattle.

The late Kenneth Melmon, MD, a groundbreaking pharmacologist, was a major influence. “He was one of the first people that I met when I began as an undergraduate at Stanford. We grew to be long-standing friends, and he demonstrated what outstanding mentorship looks like. In our research collaboration, we investigated the work of Dr. Gertrude Elion and Dr. George Hitchings involving the translation of pharmacological data from cellular and animal models to clinically useful drugs including 6-mercaptopurine, allopurinol, azathioprine, acyclovir, and zidovudine.”

The late Oliver Press, MD, a blood cancer specialist, inspired Dr. Flower’s interest in lymphoma. “I began work with him during an internship at the University of Washington. Ollie was a great inspiration and a key leader in the development of innovative therapies for lymphoma. He embodied the role of a clinical champion translating work in radioimmunotherapy to new therapeutics for patients with lymphomas. Working with him ultimately led me to pursue a career in hematology and oncology with a focus on the care for patients with lymphomas.”

Career blooms as lymphoma care advances

Dr. Flowers went on to Emory University, Atlanta, where he served as scientific director of the Research Informatics Shared Resource and a faculty member in the department of biomedical informatics. “I applied my training in informatics and my clinical expertise to support active grants from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund for Innovation in Regulatory Science and from the National Cancer Institute to develop informatics tools for pathology image analysis and prognostic modeling.”

For 13 years, he also served the Winship Cancer Institute as director of the Emory Healthcare lymphoma program (where his patients included Kansas City Chiefs football star Eric Berry), and for 4 years as scientific director of research informatics. Meanwhile, Dr. Flowers helped develop national practice guidelines for the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Radiology. He also chaired the ASCO guideline on management of febrile neutropenia.

In 2019, MD Anderson hired Dr. Flowers as chair of the department of lymphoma/myeloma. A year later, he was appointed division head ad interim for cancer medicine.

“Chris is a unique leader who expertly combines mentorship, sponsorship, and bidirectional open, honest communication,” said Sairah Ahmed, MD, associate professor of lymphoma at MD Anderson. “He doesn’t just empower his team to reach their goals. He also inspires those around him to turn vision into reality.”

As Dr. Flowers noted, many patients with lymphoma are now able to recover and live normal lives. He himself played a direct role himself in boosting lifespans.

“I have been fortunate to play a role in the development of several treatments that have led to advances in first-line therapy for patients with aggressive lymphomas. I partnered with others at MD Anderson, including Dr. Sattva Neelapu and Dr. Jason Westin, who have developed novel therapies like chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for patients with relapse lymphomas,” he said. “Leaders in the field at MD Anderson like Dr. Michael Wang have developed new oral treatments for patients with rare lymphoma subtypes like mantle cell lymphoma. Other colleagues such as Dr. Nathan Fowler and Dr. Loretta Nastoupil have focused on the care for patients with indolent lymphomas and developed less-toxic therapies that are now in common use.”

Exposing the disparities in blood cancer care

Dr. Flowers, who’s African American, has also been a leader in health disparity research. In 2016, for example, he was coauthor of a study into non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that revealed that Blacks in the United States have dramatically lower survival rates than Whites. The 10-year survival rate for Black women with chronic lymphocytic leukemia was just 47%, for example, compared with 66% for White females. “Although incidence rates of lymphoid neoplasms are generally higher among Whites, Black men tend to have poorer survival,” Dr. Flowers and colleagues wrote.

In a 2021 report for the ASCO Educational Book, Dr. Flowers and hematologist-oncologist Demetria Smith-Graziani, MD, now with Emory University, explored disparities across blood cancers and barriers to minority enrollment in clinical trials. “Some approaches that clinicians can apply to address these disparities include increasing systems-level awareness, improving access to care, and reducing biases in clinical setting,” the authors wrote.

Luis Malpica Castillo, MD, assistant professor of lymphoma at MD Anderson Cancer Center, lauded the work of Dr. Flowers in expanding opportunities for minority patients with the disease.

“During the past years, Dr. Flowers’ work has not only had a positive impact on the Texan community, but minority populations living with cancer in the United States and abroad,” he said. “Currently, we are implementing cancer care networks aimed to increase diversity in clinical trials by enrolling a larger number of Hispanic and African American patients, who otherwise may not have benefited from novel therapies. The ultimate goal is to provide high-quality care to all patients living with cancer.”

In addition to his research work, Dr. Flowers is an advocate for diversity within the hematology community. He’s a founding member and former chair of the American Society of Hematology’s Committee on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (formerly the Committee on Promoting Diversity), and he helped develop the society’s Minority Recruitment Initiative.

What’s next for Dr. Flowers? For one, he plans to continue working as a mentor; he received the ASH Mentor Award in honor of his service in 2022. “I am strongly committed to increasing the number of tenure-track investigators trained in clinical and translational cancer research and to promote their career development.”

And he looks forward to helping develop MD Anderson’s recently announced $2.5 billion hospital in Austin. “This will extend the exceptional care that we provide as the No. 1 cancer center in the United States,” he said. “It will also create new opportunities for research and collaboration with experts at UT Austin.”

When he’s not in clinic, Dr. Flowers embraces his lifelong love of speeding through life on his own two feet. He’s even inspired his children to share his passion. “I run most days of the week,” he said. “Running provides a great opportunity to think and process new research ideas, work through leadership challenges, and sometimes just to relax and let go of the day.”

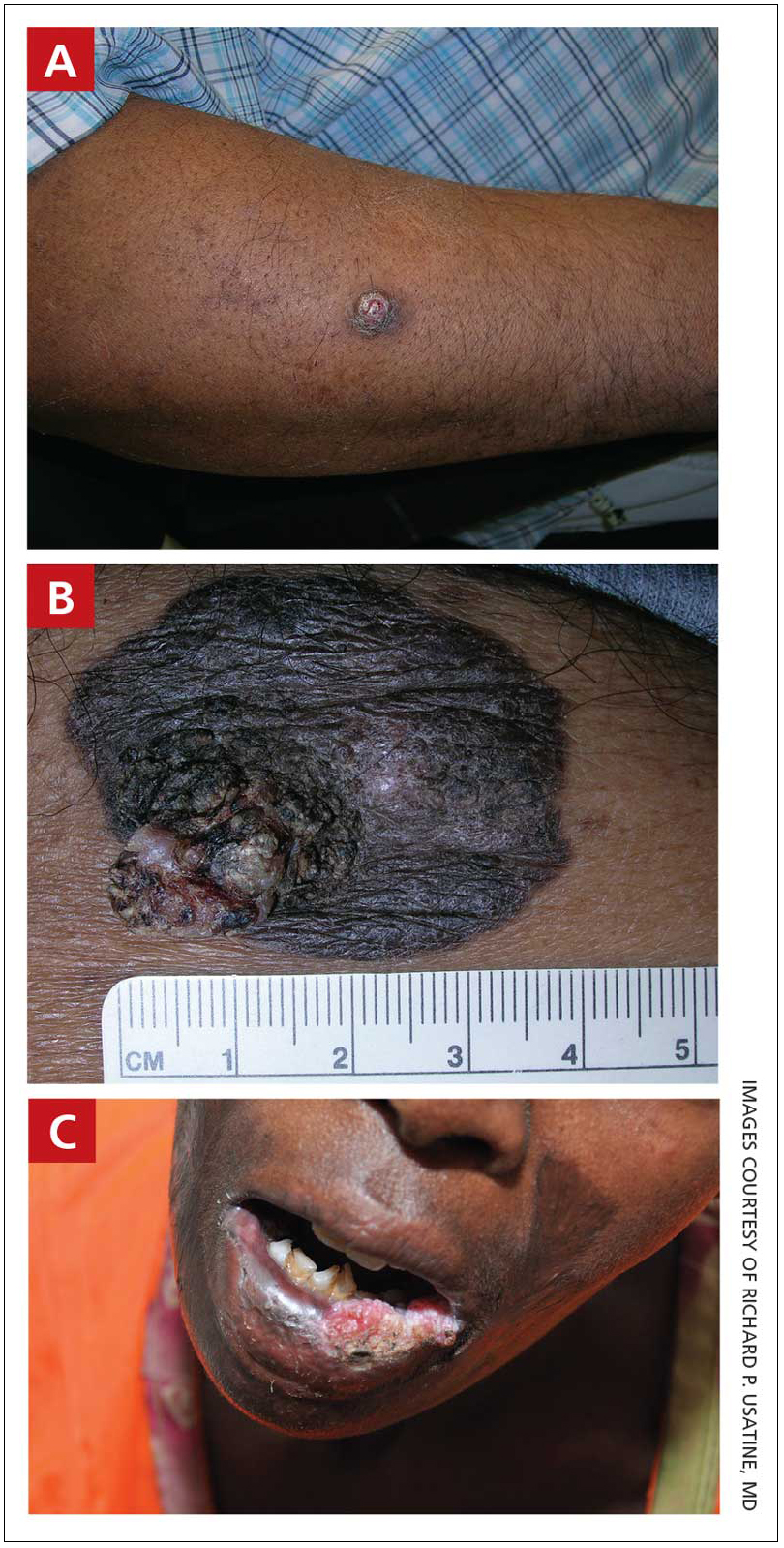

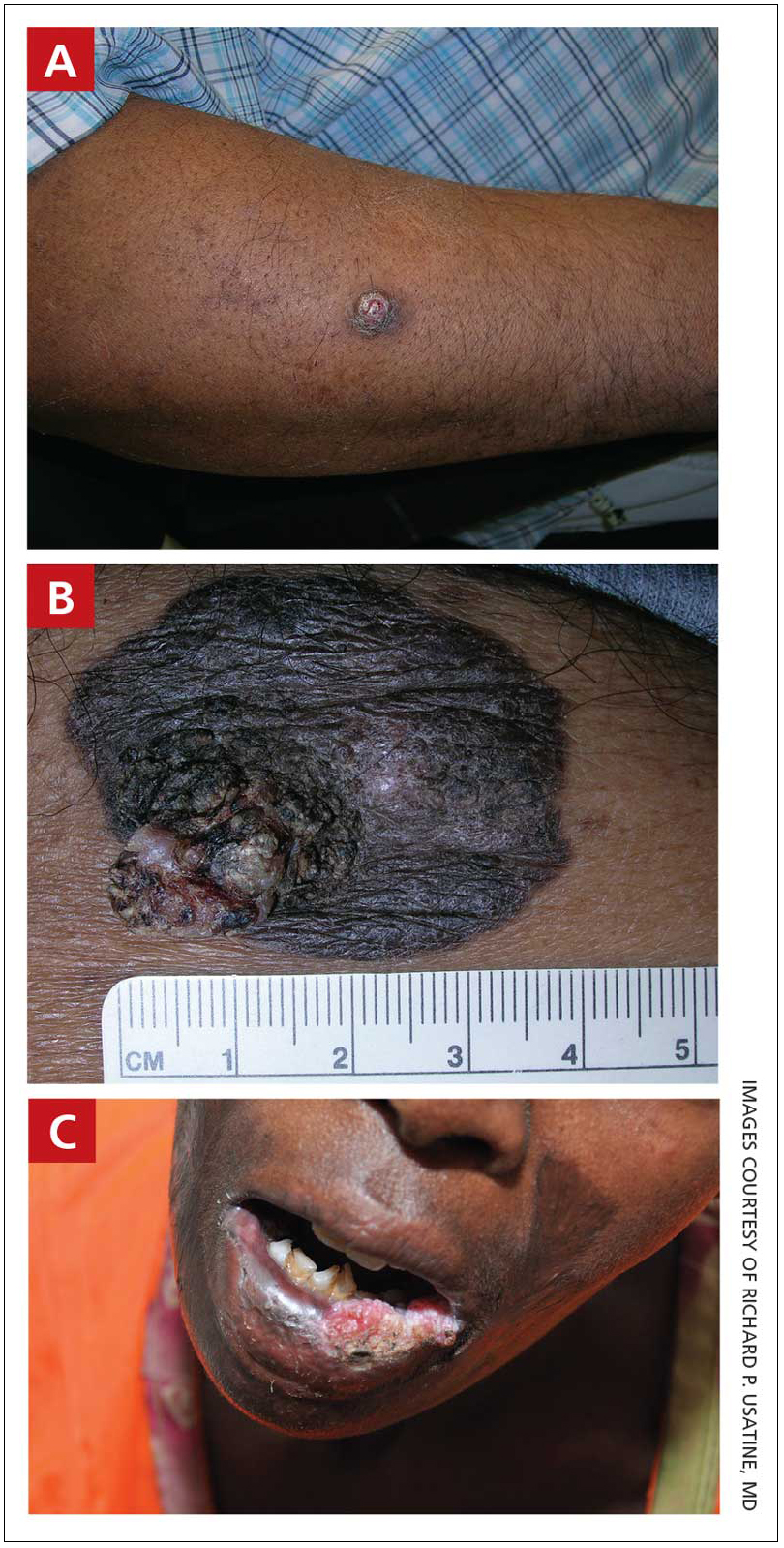

Study aims to better elucidate CCCA in men

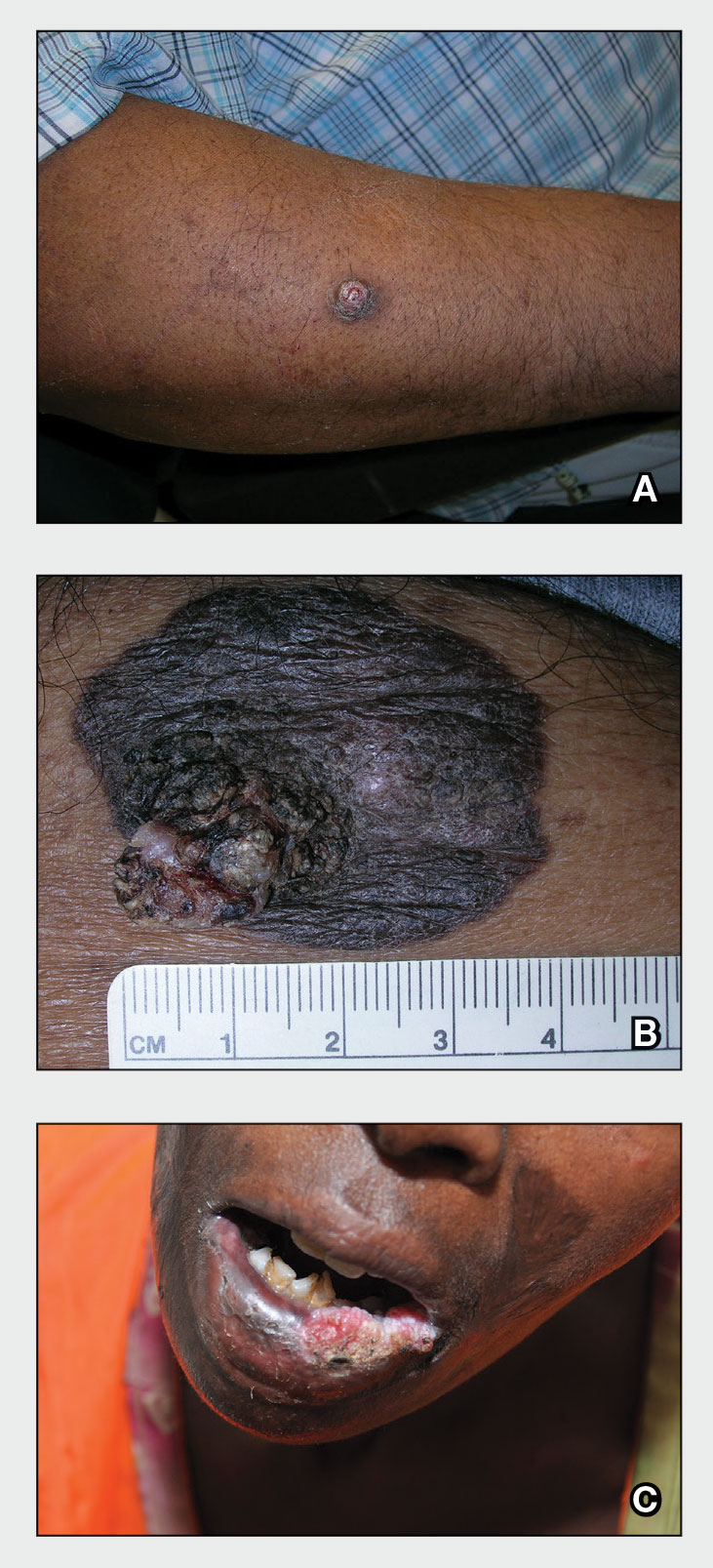

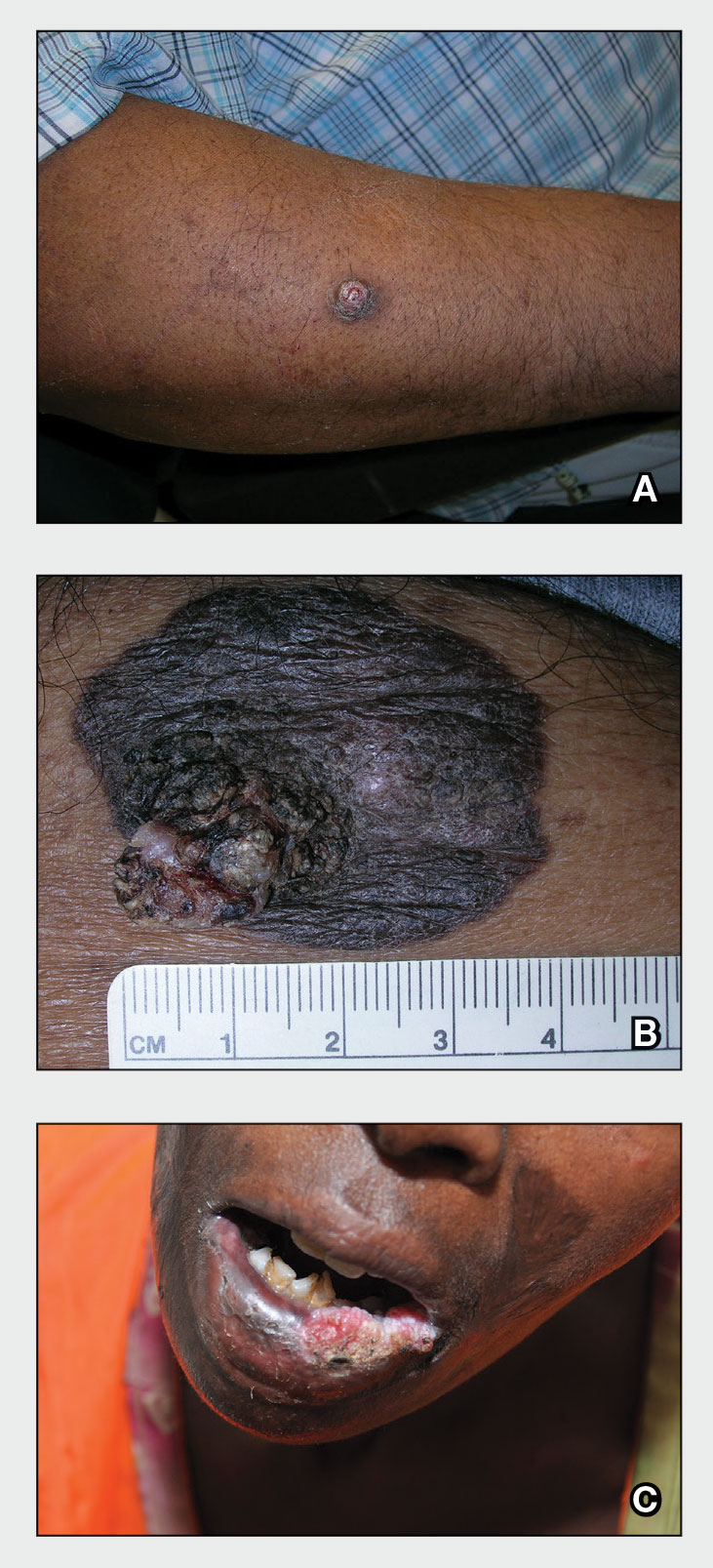

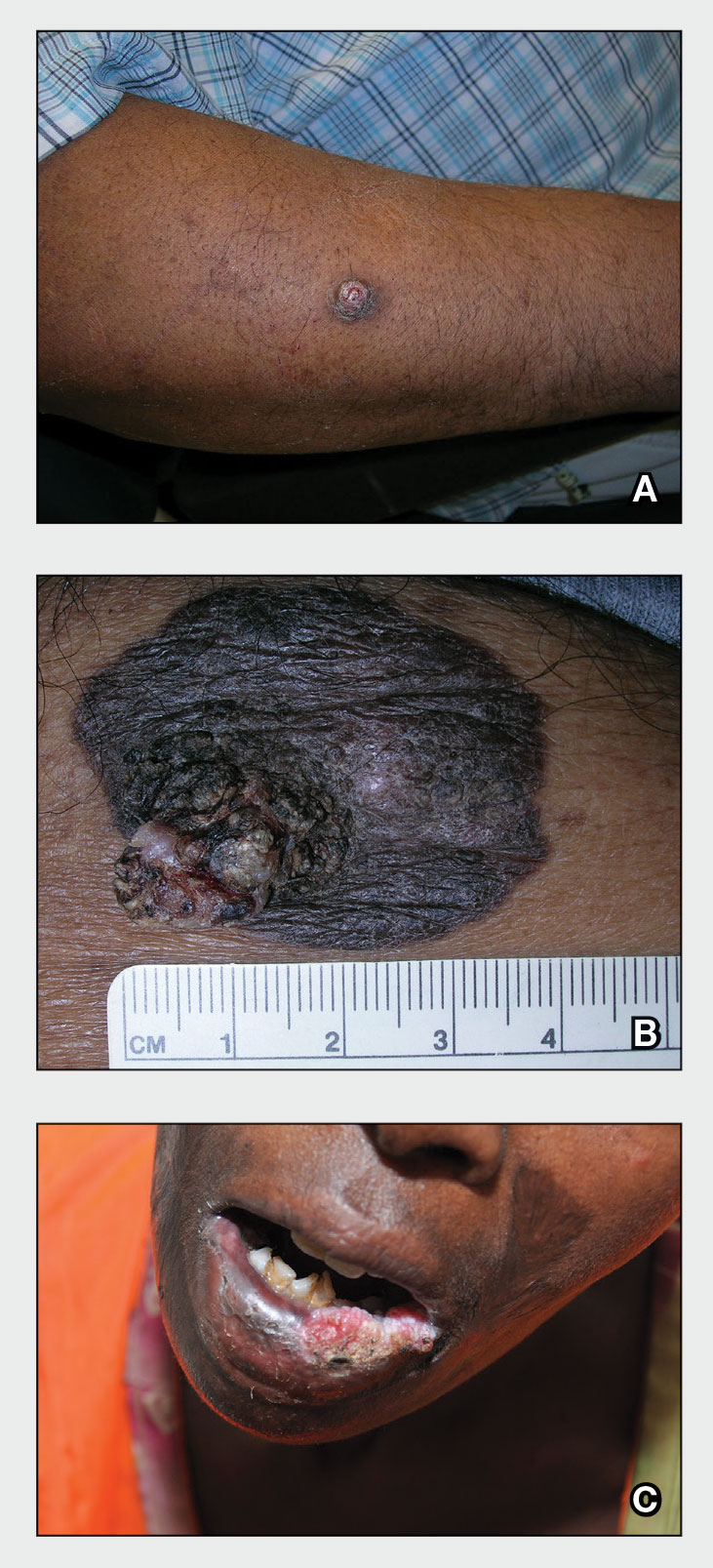

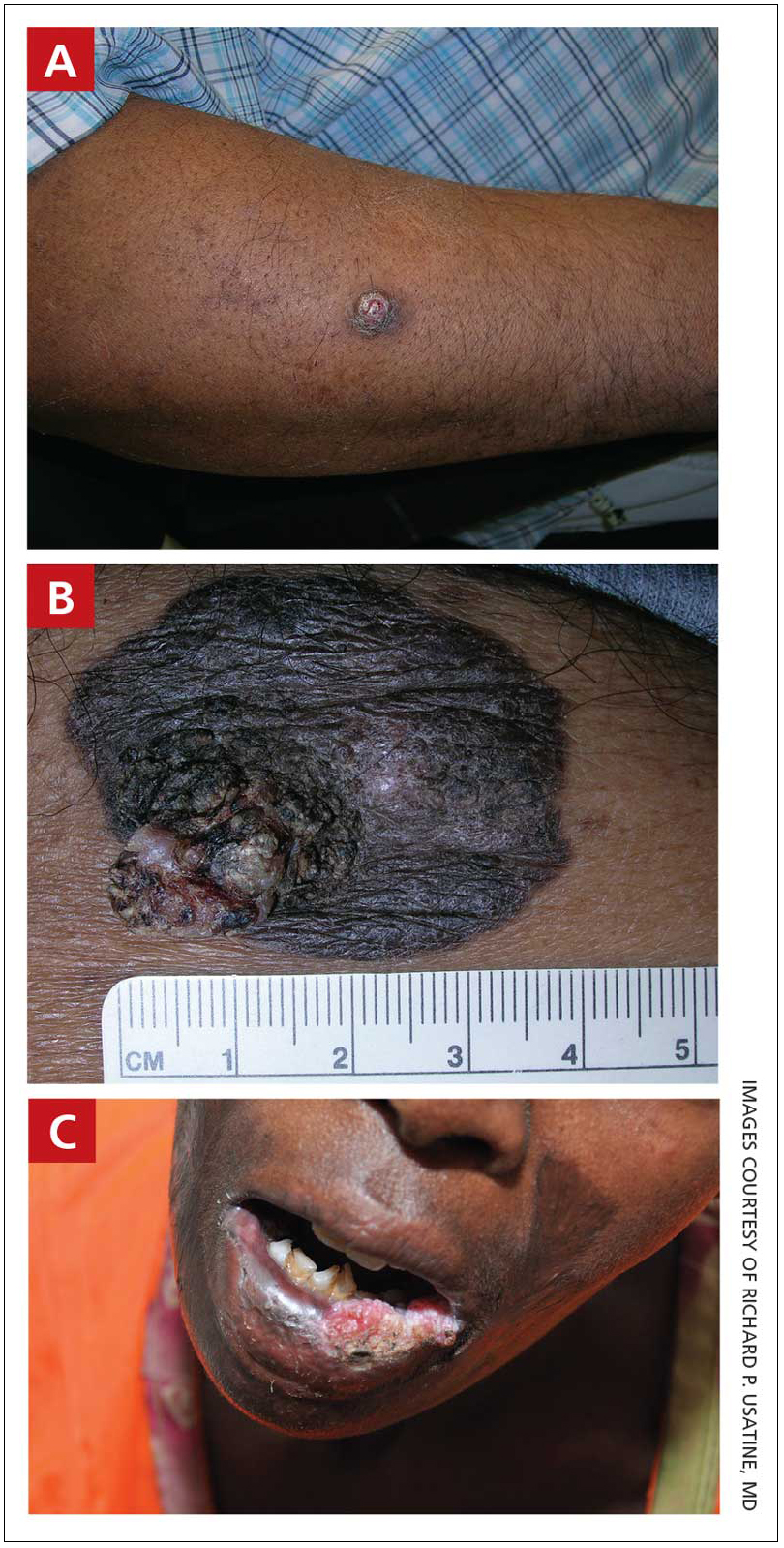

, and the most common symptom was scalp pruritus.

Researchers retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 17 male patients with a clinical diagnosis of CCCA who were seen at University of Pennsylvania outpatient clinics between 2012 and 2022. They excluded patients who had no scalp biopsy or if the scalp biopsy features limited characterization. Temitayo Ogunleye, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, led the study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

CCCA, a type of scarring alopecia, most often affects women of African descent, and published data on the demographics, clinical findings, and medical histories of CCCA in men are limited, according to the authors.

The average age of the men was 43 years and 88.2% were Black, similar to women with CCCA, who tend to be middle-aged and Black. The four most common symptoms were scalp pruritus (58.8%), lesions (29.4%), pain or tenderness (23.5%), and hair thinning (23.5%). None of the men had type 2 diabetes (considered a possible CCCA risk factor), but 47.1% had a family history of alopecia. The four most common CCCA distributions were classic (47.1%), occipital (17.6%), patchy (11.8%), and posterior vertex (11.8%).

“Larger studies are needed to fully elucidate these relationships and explore etiology in males with CCCA,” the researchers wrote. “Nonetheless, we hope the data will prompt clinicians to assess for CCCA and risk factors in adult males with scarring alopecia.”

Limitations of the study included the retrospective, single-center design, and small sample size.

The researchers reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, and the most common symptom was scalp pruritus.

Researchers retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 17 male patients with a clinical diagnosis of CCCA who were seen at University of Pennsylvania outpatient clinics between 2012 and 2022. They excluded patients who had no scalp biopsy or if the scalp biopsy features limited characterization. Temitayo Ogunleye, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, led the study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

CCCA, a type of scarring alopecia, most often affects women of African descent, and published data on the demographics, clinical findings, and medical histories of CCCA in men are limited, according to the authors.

The average age of the men was 43 years and 88.2% were Black, similar to women with CCCA, who tend to be middle-aged and Black. The four most common symptoms were scalp pruritus (58.8%), lesions (29.4%), pain or tenderness (23.5%), and hair thinning (23.5%). None of the men had type 2 diabetes (considered a possible CCCA risk factor), but 47.1% had a family history of alopecia. The four most common CCCA distributions were classic (47.1%), occipital (17.6%), patchy (11.8%), and posterior vertex (11.8%).

“Larger studies are needed to fully elucidate these relationships and explore etiology in males with CCCA,” the researchers wrote. “Nonetheless, we hope the data will prompt clinicians to assess for CCCA and risk factors in adult males with scarring alopecia.”

Limitations of the study included the retrospective, single-center design, and small sample size.

The researchers reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, and the most common symptom was scalp pruritus.

Researchers retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 17 male patients with a clinical diagnosis of CCCA who were seen at University of Pennsylvania outpatient clinics between 2012 and 2022. They excluded patients who had no scalp biopsy or if the scalp biopsy features limited characterization. Temitayo Ogunleye, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, led the study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

CCCA, a type of scarring alopecia, most often affects women of African descent, and published data on the demographics, clinical findings, and medical histories of CCCA in men are limited, according to the authors.

The average age of the men was 43 years and 88.2% were Black, similar to women with CCCA, who tend to be middle-aged and Black. The four most common symptoms were scalp pruritus (58.8%), lesions (29.4%), pain or tenderness (23.5%), and hair thinning (23.5%). None of the men had type 2 diabetes (considered a possible CCCA risk factor), but 47.1% had a family history of alopecia. The four most common CCCA distributions were classic (47.1%), occipital (17.6%), patchy (11.8%), and posterior vertex (11.8%).

“Larger studies are needed to fully elucidate these relationships and explore etiology in males with CCCA,” the researchers wrote. “Nonetheless, we hope the data will prompt clinicians to assess for CCCA and risk factors in adult males with scarring alopecia.”

Limitations of the study included the retrospective, single-center design, and small sample size.

The researchers reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Don’t skip contraception talk for women with complex health conditions

.

In an installment of the American College of Physicians’ In the Clinic series, Rachel Cannon, MD, Kelly Treder, MD, and Elisabeth J. Woodhams, MD, all of Boston Medical Center, presented an article on the complex topic of contraception for patients with chronic illness.

“Many patients with chronic illness or complex medical issues interact with a primary care provider on a frequent basis, which provides a great access point for contraceptive counseling with a provider they trust and know,” said Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder in a joint interview. “We wanted to create a ‘go to’ resource for primary care physicians to review contraceptive options and counseling best practices for all of their patients. Contraceptive care is part of overall health care and should be included in the primary care encounter.”

The authors discussed the types of contraception, as well as risks and benefits, and offered guidance for choosing a contraceptive method for medically complex patients.

“In recent years, there has been a shift in contraceptive counseling toward shared decision-making, a counseling strategy that honors the patient as the expert in their body and their life experiences and emphasizes their autonomy and values,” the authors said. “For providers, this translates to understanding that contraceptive efficacy is not the only important characteristic to patients, and that many other important factors contribute to an individual’s decision to use a particular method or not use birth control at all,” they said.

Start the conversation

Start by assessing a patient’s interest in and readiness for pregnancy, if applicable, the authors said. One example of a screen, the PATH questionnaire (Parent/Pregnancy Attitudes, Timing, and How important), is designed for patients in any demographic, and includes questions about the timing and desire for pregnancy and feelings about birth control, as well as options for patients to express uncertainty or ambivalence about pregnancy and contraception.

Some patients may derive benefits from hormonal contraceptives beyond pregnancy prevention, the authors wrote. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) may improve menorrhagia, and data suggest that CHC use also may reduce risk for some cancer types, including endometrial and ovarian cancers, they said.

Overall, contraceptive counseling should include discussions of safety, efficacy, and the patient’s lived experience.

Clinical considerations and contraindications

Medically complex patients who desire contraception may consider hormonal or nonhormonal methods based on their preferences and medical conditions, but clinicians need to consider comorbidities and contraindications, the authors wrote.

When a woman of childbearing age with any complex medical issue starts a new medication or receives a new diagnosis, contraception and pregnancy planning should be part of the discussion, the authors said. Safe and successful pregnancies are possible for women with complex medical issues when underlying health concerns are identified and addressed in advance, they added. Alternatively, for patients seeking to avoid pregnancy permanently, options for sterilization can be part of an informed discussion.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use offers clinicians detailed information about the risks of both contraceptives and pregnancy for patients with various medical conditions, according to the authors.

The CDC document lists medical conditions associated with an increased risk for adverse health events if the individual becomes pregnant. These conditions include breast cancer, complicated valvular heart disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, endometrial or ovarian cancer, epilepsy, hypertension, bariatric surgery within 2 years of the pregnancy, HIV, ischemic heart disease, severe cirrhosis, stroke, lupus, solid organ transplant within 2 years of the pregnancy, and tuberculosis. Women with these and other conditions associated with increased risk of adverse events if pregnancy occurs should be advised of the high failure rate of barrier and behavior-based contraceptive methods, and informed about options for long-acting contraceptives, according to the CDC.

Risks, benefits, and balance

“It is important to remember that the alternative to contraception for many patients is pregnancy – for many patients with complex medical conditions, pregnancy is far more dangerous than any contraceptive method,” Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder said in an interview. “This is important to consider when thinking about relative contraindications to a certain method or when thinking about ‘less effective’ contraception methods. The most effective method is a method the patient will actually continue to use,” they said.

The recent approval of the over-the-counter minipill is “a huge win for reproductive health care,” said Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder. The minipill has very few contraindications, and it is the most effective over-the-counter contraceptive now available, they said.

“An over-the-counter contraceptive pill can increase access to contraception without having to see a physician in the clinic, freeing patients from many of the challenges of navigating the health care system,” the authors added.

As for additional research, the establishment of a long-term safety record may help support other OTC contraceptive methods in the future, the authors said.

Contraceptive counseling is everyone’s specialty

In an accompanying editorial, Amy A. Sarma, MD, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, shared an example of the importance of contraceptive discussions with medically complex patients outside of an ob.gyn. setting. A young woman with a family history of myocardial infarction had neglected her own primary care until an MI of her own sent her to the hospital. While hospitalized, the patient was diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

“Her cardiology care team made every effort to optimize her cardiac care, but no one considered that she was also a woman of childbearing potential despite the teratogenic potential of several of her prescribed medications,” Dr. Sarma wrote. When the patient visited Dr. Sarma to discuss prevention of future MIs, Dr. Sarma took the opportunity to discuss the cardiovascular risks of pregnancy and the risks for this patient not only because of her recent MI, but also because of her chronic health conditions.

As it happened, the woman did not want a high-risk pregnancy and was interested in contraceptive methods. Dr. Sarma pointed out that, had the woman been engaged in routine primary care, these issues would have arisen in that setting, but like many younger women with cardiovascular disease, she did not make her own primary care a priority, and had missed out on other opportunities to discuss contraception. “Her MI opened a window of opportunity to help prevent an unintended and high-risk pregnancy,” Dr. Sarma noted.

Dr. Sarma’s patient anecdote illustrated the point of the In the Clinic review: that any clinician can discuss pregnancy and contraception with patients of childbearing age who have medical comorbidities that could affect a pregnancy. “All clinicians who care for patients of reproductive potential should become comfortable discussing pregnancy intent, preconception risk assessment, and contraceptive counseling,” Dr. Sarma said.

The research for this article was funded by the American College of Physicians. The review authors had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Sarma had no financial conflicts to disclose.

.

In an installment of the American College of Physicians’ In the Clinic series, Rachel Cannon, MD, Kelly Treder, MD, and Elisabeth J. Woodhams, MD, all of Boston Medical Center, presented an article on the complex topic of contraception for patients with chronic illness.

“Many patients with chronic illness or complex medical issues interact with a primary care provider on a frequent basis, which provides a great access point for contraceptive counseling with a provider they trust and know,” said Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder in a joint interview. “We wanted to create a ‘go to’ resource for primary care physicians to review contraceptive options and counseling best practices for all of their patients. Contraceptive care is part of overall health care and should be included in the primary care encounter.”

The authors discussed the types of contraception, as well as risks and benefits, and offered guidance for choosing a contraceptive method for medically complex patients.

“In recent years, there has been a shift in contraceptive counseling toward shared decision-making, a counseling strategy that honors the patient as the expert in their body and their life experiences and emphasizes their autonomy and values,” the authors said. “For providers, this translates to understanding that contraceptive efficacy is not the only important characteristic to patients, and that many other important factors contribute to an individual’s decision to use a particular method or not use birth control at all,” they said.

Start the conversation

Start by assessing a patient’s interest in and readiness for pregnancy, if applicable, the authors said. One example of a screen, the PATH questionnaire (Parent/Pregnancy Attitudes, Timing, and How important), is designed for patients in any demographic, and includes questions about the timing and desire for pregnancy and feelings about birth control, as well as options for patients to express uncertainty or ambivalence about pregnancy and contraception.

Some patients may derive benefits from hormonal contraceptives beyond pregnancy prevention, the authors wrote. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) may improve menorrhagia, and data suggest that CHC use also may reduce risk for some cancer types, including endometrial and ovarian cancers, they said.

Overall, contraceptive counseling should include discussions of safety, efficacy, and the patient’s lived experience.

Clinical considerations and contraindications

Medically complex patients who desire contraception may consider hormonal or nonhormonal methods based on their preferences and medical conditions, but clinicians need to consider comorbidities and contraindications, the authors wrote.

When a woman of childbearing age with any complex medical issue starts a new medication or receives a new diagnosis, contraception and pregnancy planning should be part of the discussion, the authors said. Safe and successful pregnancies are possible for women with complex medical issues when underlying health concerns are identified and addressed in advance, they added. Alternatively, for patients seeking to avoid pregnancy permanently, options for sterilization can be part of an informed discussion.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use offers clinicians detailed information about the risks of both contraceptives and pregnancy for patients with various medical conditions, according to the authors.

The CDC document lists medical conditions associated with an increased risk for adverse health events if the individual becomes pregnant. These conditions include breast cancer, complicated valvular heart disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, endometrial or ovarian cancer, epilepsy, hypertension, bariatric surgery within 2 years of the pregnancy, HIV, ischemic heart disease, severe cirrhosis, stroke, lupus, solid organ transplant within 2 years of the pregnancy, and tuberculosis. Women with these and other conditions associated with increased risk of adverse events if pregnancy occurs should be advised of the high failure rate of barrier and behavior-based contraceptive methods, and informed about options for long-acting contraceptives, according to the CDC.

Risks, benefits, and balance

“It is important to remember that the alternative to contraception for many patients is pregnancy – for many patients with complex medical conditions, pregnancy is far more dangerous than any contraceptive method,” Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder said in an interview. “This is important to consider when thinking about relative contraindications to a certain method or when thinking about ‘less effective’ contraception methods. The most effective method is a method the patient will actually continue to use,” they said.

The recent approval of the over-the-counter minipill is “a huge win for reproductive health care,” said Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder. The minipill has very few contraindications, and it is the most effective over-the-counter contraceptive now available, they said.

“An over-the-counter contraceptive pill can increase access to contraception without having to see a physician in the clinic, freeing patients from many of the challenges of navigating the health care system,” the authors added.

As for additional research, the establishment of a long-term safety record may help support other OTC contraceptive methods in the future, the authors said.

Contraceptive counseling is everyone’s specialty

In an accompanying editorial, Amy A. Sarma, MD, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, shared an example of the importance of contraceptive discussions with medically complex patients outside of an ob.gyn. setting. A young woman with a family history of myocardial infarction had neglected her own primary care until an MI of her own sent her to the hospital. While hospitalized, the patient was diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

“Her cardiology care team made every effort to optimize her cardiac care, but no one considered that she was also a woman of childbearing potential despite the teratogenic potential of several of her prescribed medications,” Dr. Sarma wrote. When the patient visited Dr. Sarma to discuss prevention of future MIs, Dr. Sarma took the opportunity to discuss the cardiovascular risks of pregnancy and the risks for this patient not only because of her recent MI, but also because of her chronic health conditions.

As it happened, the woman did not want a high-risk pregnancy and was interested in contraceptive methods. Dr. Sarma pointed out that, had the woman been engaged in routine primary care, these issues would have arisen in that setting, but like many younger women with cardiovascular disease, she did not make her own primary care a priority, and had missed out on other opportunities to discuss contraception. “Her MI opened a window of opportunity to help prevent an unintended and high-risk pregnancy,” Dr. Sarma noted.

Dr. Sarma’s patient anecdote illustrated the point of the In the Clinic review: that any clinician can discuss pregnancy and contraception with patients of childbearing age who have medical comorbidities that could affect a pregnancy. “All clinicians who care for patients of reproductive potential should become comfortable discussing pregnancy intent, preconception risk assessment, and contraceptive counseling,” Dr. Sarma said.

The research for this article was funded by the American College of Physicians. The review authors had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Sarma had no financial conflicts to disclose.

.

In an installment of the American College of Physicians’ In the Clinic series, Rachel Cannon, MD, Kelly Treder, MD, and Elisabeth J. Woodhams, MD, all of Boston Medical Center, presented an article on the complex topic of contraception for patients with chronic illness.

“Many patients with chronic illness or complex medical issues interact with a primary care provider on a frequent basis, which provides a great access point for contraceptive counseling with a provider they trust and know,” said Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder in a joint interview. “We wanted to create a ‘go to’ resource for primary care physicians to review contraceptive options and counseling best practices for all of their patients. Contraceptive care is part of overall health care and should be included in the primary care encounter.”

The authors discussed the types of contraception, as well as risks and benefits, and offered guidance for choosing a contraceptive method for medically complex patients.

“In recent years, there has been a shift in contraceptive counseling toward shared decision-making, a counseling strategy that honors the patient as the expert in their body and their life experiences and emphasizes their autonomy and values,” the authors said. “For providers, this translates to understanding that contraceptive efficacy is not the only important characteristic to patients, and that many other important factors contribute to an individual’s decision to use a particular method or not use birth control at all,” they said.

Start the conversation

Start by assessing a patient’s interest in and readiness for pregnancy, if applicable, the authors said. One example of a screen, the PATH questionnaire (Parent/Pregnancy Attitudes, Timing, and How important), is designed for patients in any demographic, and includes questions about the timing and desire for pregnancy and feelings about birth control, as well as options for patients to express uncertainty or ambivalence about pregnancy and contraception.

Some patients may derive benefits from hormonal contraceptives beyond pregnancy prevention, the authors wrote. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) may improve menorrhagia, and data suggest that CHC use also may reduce risk for some cancer types, including endometrial and ovarian cancers, they said.

Overall, contraceptive counseling should include discussions of safety, efficacy, and the patient’s lived experience.

Clinical considerations and contraindications

Medically complex patients who desire contraception may consider hormonal or nonhormonal methods based on their preferences and medical conditions, but clinicians need to consider comorbidities and contraindications, the authors wrote.

When a woman of childbearing age with any complex medical issue starts a new medication or receives a new diagnosis, contraception and pregnancy planning should be part of the discussion, the authors said. Safe and successful pregnancies are possible for women with complex medical issues when underlying health concerns are identified and addressed in advance, they added. Alternatively, for patients seeking to avoid pregnancy permanently, options for sterilization can be part of an informed discussion.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use offers clinicians detailed information about the risks of both contraceptives and pregnancy for patients with various medical conditions, according to the authors.

The CDC document lists medical conditions associated with an increased risk for adverse health events if the individual becomes pregnant. These conditions include breast cancer, complicated valvular heart disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, endometrial or ovarian cancer, epilepsy, hypertension, bariatric surgery within 2 years of the pregnancy, HIV, ischemic heart disease, severe cirrhosis, stroke, lupus, solid organ transplant within 2 years of the pregnancy, and tuberculosis. Women with these and other conditions associated with increased risk of adverse events if pregnancy occurs should be advised of the high failure rate of barrier and behavior-based contraceptive methods, and informed about options for long-acting contraceptives, according to the CDC.

Risks, benefits, and balance

“It is important to remember that the alternative to contraception for many patients is pregnancy – for many patients with complex medical conditions, pregnancy is far more dangerous than any contraceptive method,” Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder said in an interview. “This is important to consider when thinking about relative contraindications to a certain method or when thinking about ‘less effective’ contraception methods. The most effective method is a method the patient will actually continue to use,” they said.

The recent approval of the over-the-counter minipill is “a huge win for reproductive health care,” said Dr. Cannon and Dr. Treder. The minipill has very few contraindications, and it is the most effective over-the-counter contraceptive now available, they said.

“An over-the-counter contraceptive pill can increase access to contraception without having to see a physician in the clinic, freeing patients from many of the challenges of navigating the health care system,” the authors added.

As for additional research, the establishment of a long-term safety record may help support other OTC contraceptive methods in the future, the authors said.

Contraceptive counseling is everyone’s specialty

In an accompanying editorial, Amy A. Sarma, MD, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, shared an example of the importance of contraceptive discussions with medically complex patients outside of an ob.gyn. setting. A young woman with a family history of myocardial infarction had neglected her own primary care until an MI of her own sent her to the hospital. While hospitalized, the patient was diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

“Her cardiology care team made every effort to optimize her cardiac care, but no one considered that she was also a woman of childbearing potential despite the teratogenic potential of several of her prescribed medications,” Dr. Sarma wrote. When the patient visited Dr. Sarma to discuss prevention of future MIs, Dr. Sarma took the opportunity to discuss the cardiovascular risks of pregnancy and the risks for this patient not only because of her recent MI, but also because of her chronic health conditions.

As it happened, the woman did not want a high-risk pregnancy and was interested in contraceptive methods. Dr. Sarma pointed out that, had the woman been engaged in routine primary care, these issues would have arisen in that setting, but like many younger women with cardiovascular disease, she did not make her own primary care a priority, and had missed out on other opportunities to discuss contraception. “Her MI opened a window of opportunity to help prevent an unintended and high-risk pregnancy,” Dr. Sarma noted.

Dr. Sarma’s patient anecdote illustrated the point of the In the Clinic review: that any clinician can discuss pregnancy and contraception with patients of childbearing age who have medical comorbidities that could affect a pregnancy. “All clinicians who care for patients of reproductive potential should become comfortable discussing pregnancy intent, preconception risk assessment, and contraceptive counseling,” Dr. Sarma said.

The research for this article was funded by the American College of Physicians. The review authors had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Sarma had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Addressing disparities in goals-of-care conversations

Critical Care Network

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

Goals-of-care discussions are essential to management of the intensive care unit (ICU) patient. Racial inequities in end-of-life decision making have been documented for many years, with literature demonstrating that marginalized populations are less likely to have EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions and more likely to have concerns regarding clinician communication.

A recently published randomized control trial in JAMA highlights an intervention that offers promise in addressing disparities in goals-of-care conversations. Curtis, et al. studied whether priming physicians with a communication guide advising on discussion prompts and language for goals-of-care could improve the rate of documented goals-of-care discussions among hospitalized older adults with serious illness. The study found that for patients in the intervention arm, there was a significant increase in proportion of goals-of-care discussions within 30 days. Notably, the difference in documented goals-of-care discussions between arms was greater in the subgroup of patients from underserved groups (Curtis JR, et al. JAMA. 2023;329[23]:2028-37).

Nevertheless, while interventions may help increase the rate of goals-of-care discussions, it is also important to address the content of discussions themselves. You and colleagues recently published a mixed-methods study assessing the impact of race on shared decision-making behaviors during family/caregiver meetings. The authors found that while ICU physicians approached shared decision making with White and Black families similarly, Black families felt their physicians provided less validation of the family role in decision making than White families did (You H, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023 May;20[5]:759-62). These findings highlight the importance of ongoing work that focuses not only on quantity but also on quality of communication regarding goals-of-care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Divya Shankar MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Muhammad Hayat-Syed MD

Section Vice Chair

Critical Care Network

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

Goals-of-care discussions are essential to management of the intensive care unit (ICU) patient. Racial inequities in end-of-life decision making have been documented for many years, with literature demonstrating that marginalized populations are less likely to have EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions and more likely to have concerns regarding clinician communication.

A recently published randomized control trial in JAMA highlights an intervention that offers promise in addressing disparities in goals-of-care conversations. Curtis, et al. studied whether priming physicians with a communication guide advising on discussion prompts and language for goals-of-care could improve the rate of documented goals-of-care discussions among hospitalized older adults with serious illness. The study found that for patients in the intervention arm, there was a significant increase in proportion of goals-of-care discussions within 30 days. Notably, the difference in documented goals-of-care discussions between arms was greater in the subgroup of patients from underserved groups (Curtis JR, et al. JAMA. 2023;329[23]:2028-37).

Nevertheless, while interventions may help increase the rate of goals-of-care discussions, it is also important to address the content of discussions themselves. You and colleagues recently published a mixed-methods study assessing the impact of race on shared decision-making behaviors during family/caregiver meetings. The authors found that while ICU physicians approached shared decision making with White and Black families similarly, Black families felt their physicians provided less validation of the family role in decision making than White families did (You H, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023 May;20[5]:759-62). These findings highlight the importance of ongoing work that focuses not only on quantity but also on quality of communication regarding goals-of-care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Divya Shankar MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Muhammad Hayat-Syed MD

Section Vice Chair

Critical Care Network

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

Goals-of-care discussions are essential to management of the intensive care unit (ICU) patient. Racial inequities in end-of-life decision making have been documented for many years, with literature demonstrating that marginalized populations are less likely to have EHR-documented goals-of-care discussions and more likely to have concerns regarding clinician communication.

A recently published randomized control trial in JAMA highlights an intervention that offers promise in addressing disparities in goals-of-care conversations. Curtis, et al. studied whether priming physicians with a communication guide advising on discussion prompts and language for goals-of-care could improve the rate of documented goals-of-care discussions among hospitalized older adults with serious illness. The study found that for patients in the intervention arm, there was a significant increase in proportion of goals-of-care discussions within 30 days. Notably, the difference in documented goals-of-care discussions between arms was greater in the subgroup of patients from underserved groups (Curtis JR, et al. JAMA. 2023;329[23]:2028-37).

Nevertheless, while interventions may help increase the rate of goals-of-care discussions, it is also important to address the content of discussions themselves. You and colleagues recently published a mixed-methods study assessing the impact of race on shared decision-making behaviors during family/caregiver meetings. The authors found that while ICU physicians approached shared decision making with White and Black families similarly, Black families felt their physicians provided less validation of the family role in decision making than White families did (You H, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023 May;20[5]:759-62). These findings highlight the importance of ongoing work that focuses not only on quantity but also on quality of communication regarding goals-of-care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Divya Shankar MD

Section Fellow-in-Training

Muhammad Hayat-Syed MD

Section Vice Chair

Social needs case management cuts acute care usage

Hospitalizations fell by 11% in patients assigned to integrated social needs case management, a randomized controlled study conducted in California found.

The reduction in acute care use was likely because of the 3% increase in primary care visits with this approach, according to lead study author Mark D. Fleming, PhD, MS, assistant professor of health and social behavior at the University of California, Berkeley. The study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The findings provide evidence for the theory that social needs case management can decrease acute care use by facilitating access to primary care, Dr. Fleming said in an interview. “While an increasing number of studies have measured the effects of social needs case management on hospital use, the findings have been inconsistent, with some studies showing a decrease in hospital use and others showing no change.” There was no strong evidence of an effect on acute care.

A 2018 study, however, found that liaising with community care workers substantially reduced hospital days in disadvantaged patients.

Case management, a complex approach linking medical and social needs, can overcome barriers to care by facilitating access to transportation and helping patients navigate the health care system, the authors noted. It can also streamline patient access to insurance coverage and social benefits.

The study

The current data came from a secondary analysis of a randomized encouragement study in Costa County, Calif., during 2017 and 2018. That study allocated adult California Medicaid beneficiaries of diverse race and ethnicity, relatively high social needs, and high risk for acute care use to two arms: social needs case management (n = 21,422) or administrative observation (22,389 weighted). Chronic health issues ranged from arthritis, diabetes, and back conditions to heart or lung disease, and psychological disorders. About 50% in both groups were younger than age 40 and 60% were women.

Case managers assessed patient needs, created a patient-centered care plan, and facilitated community resource referrals, primary care visits, and applications for public benefits.

The professionally diverse managers included public health nurses, social workers, substance misuse counselors, and mental health clinicians, as well as homeless service specialists and community health workers. Case management was offered as in-person or remote telephonic services for 1 year.

While rates of primary care visits were significantly higher in the case management group – incidence rate 1.03 (95% confidence interval [CI],1.00-1.07) – no intergroup differences emerged in visits for specialty care, behavioral health, psychiatric emergency visits, or jail intakes.

Although the analysis could not measure a direct effect of primary care use on hospitalizations, the results suggested it would take 6.6 primary care visits to avert one hospitalization. As a limitation, the outcomes were studied for only 1 year, but further effects of case management on health and service use could take longer to appear.

Commenting on the analysis but not involved in it, Laura Gottlieb, MD, MPH, professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said a few studies have suggested several pathways through which case management might influence health and health care utilization – and not solely through access to social services.

“The current findings underscore that one of those pathways is likely via connection to health care services,” she said.

As to the cost effectiveness of social needs case management given the necessary increase in personnel costs, she added, that it is a matter of society’s priorities. “If we want to achieve equity, we need to invest dollars differently. That is not a hospital-level issue. It is a society-level issue. Hospitals need to be able to stay afloat, so health care policies need to enable them to make different decisions,” she added. Broadly implementing such an approach will obviously take investment, Dr. Gottlieb continued.

“California Medicaid is trying to enable this shift in investments, but it is hard to move existing structures.” She added that more data are needed on the interaction between social services, patient experiences of care, and self-efficacy to understand a wider array of mechanisms through which case management might affect outcomes.

This analysis was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Contra Costa Health Services. The authors disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Hospitalizations fell by 11% in patients assigned to integrated social needs case management, a randomized controlled study conducted in California found.

The reduction in acute care use was likely because of the 3% increase in primary care visits with this approach, according to lead study author Mark D. Fleming, PhD, MS, assistant professor of health and social behavior at the University of California, Berkeley. The study was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The findings provide evidence for the theory that social needs case management can decrease acute care use by facilitating access to primary care, Dr. Fleming said in an interview. “While an increasing number of studies have measured the effects of social needs case management on hospital use, the findings have been inconsistent, with some studies showing a decrease in hospital use and others showing no change.” There was no strong evidence of an effect on acute care.

A 2018 study, however, found that liaising with community care workers substantially reduced hospital days in disadvantaged patients.

Case management, a complex approach linking medical and social needs, can overcome barriers to care by facilitating access to transportation and helping patients navigate the health care system, the authors noted. It can also streamline patient access to insurance coverage and social benefits.

The study

The current data came from a secondary analysis of a randomized encouragement study in Costa County, Calif., during 2017 and 2018. That study allocated adult California Medicaid beneficiaries of diverse race and ethnicity, relatively high social needs, and high risk for acute care use to two arms: social needs case management (n = 21,422) or administrative observation (22,389 weighted). Chronic health issues ranged from arthritis, diabetes, and back conditions to heart or lung disease, and psychological disorders. About 50% in both groups were younger than age 40 and 60% were women.

Case managers assessed patient needs, created a patient-centered care plan, and facilitated community resource referrals, primary care visits, and applications for public benefits.

The professionally diverse managers included public health nurses, social workers, substance misuse counselors, and mental health clinicians, as well as homeless service specialists and community health workers. Case management was offered as in-person or remote telephonic services for 1 year.

While rates of primary care visits were significantly higher in the case management group – incidence rate 1.03 (95% confidence interval [CI],1.00-1.07) – no intergroup differences emerged in visits for specialty care, behavioral health, psychiatric emergency visits, or jail intakes.

Although the analysis could not measure a direct effect of primary care use on hospitalizations, the results suggested it would take 6.6 primary care visits to avert one hospitalization. As a limitation, the outcomes were studied for only 1 year, but further effects of case management on health and service use could take longer to appear.

Commenting on the analysis but not involved in it, Laura Gottlieb, MD, MPH, professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said a few studies have suggested several pathways through which case management might influence health and health care utilization – and not solely through access to social services.