User login

Positive top-line results for cannabinoid-based med for nerve pain

, new top-line results released by Zelira Therapeutics suggest.

“The implications of these results for patients are incredibly promising,” principal investigator Bryan Doner, DO, medical director of HealthyWays Integrated Wellness Solutions, Gibsonia, Pa., said in a news release.

“Through this rigorously designed study, we have demonstrated that ZLT-L-007 is a safe, effective, and well-tolerated alternative for patients who would typically seek a Lyrica-level of pain relief,” he added.

The observational, nonblinded trial tested the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ZLT-L-007 against pregabalin in 60 adults with diabetic nerve pain.

The study had three groups with 20 patients each (pregabalin alone, pregabalin plus ZLT-L-007, and ZLT-L-007 alone).

Top-line results show the study met its primary endpoint for change in daily pain severity as measured by the percent change from baseline at 30, 60, and 90 days on the Numerical Rating Scale.

For the pregabalin-only group, there was a reduction in symptom severity at all follow-up points, ranging from 20% to 35% (median percent change from baseline), the company said.

For the ZLT-L-007 only group, there was about a 33% reduction in symptom severity at 30 days, and 71% and 78% reduction, respectively, at 60 and 90 days, suggesting a larger improvement in symptom severity than with pregabalin alone, the company said.

For the pregabalin plus ZLT-L-007 group, there was a moderate 20% reduction in symptom severity at 30 days, but a larger reduction at 60 and 90 days (50% and 72%, respectively), which indicates substantially greater improvement in symptom severity than with pregabalin alone, the company said.

The study also met secondary endpoints, including significant decreases in daily pain severity as measured by the Visual Analog Scale and measurable changes in the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire and Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory.

Dr. Doner noted that the top-line data showed “no serious adverse events, and participants’ blood pressure and other safety vitals remained unaffected throughout. This confirms that ZLT-L-007 is a well-tolerated product that delivers statistically significant pain relief, surpassing the levels achieved by Lyrica.”

The company plans to report additional insights from the full study, as they become available, during fiscal year 2023-2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new top-line results released by Zelira Therapeutics suggest.

“The implications of these results for patients are incredibly promising,” principal investigator Bryan Doner, DO, medical director of HealthyWays Integrated Wellness Solutions, Gibsonia, Pa., said in a news release.

“Through this rigorously designed study, we have demonstrated that ZLT-L-007 is a safe, effective, and well-tolerated alternative for patients who would typically seek a Lyrica-level of pain relief,” he added.

The observational, nonblinded trial tested the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ZLT-L-007 against pregabalin in 60 adults with diabetic nerve pain.

The study had three groups with 20 patients each (pregabalin alone, pregabalin plus ZLT-L-007, and ZLT-L-007 alone).

Top-line results show the study met its primary endpoint for change in daily pain severity as measured by the percent change from baseline at 30, 60, and 90 days on the Numerical Rating Scale.

For the pregabalin-only group, there was a reduction in symptom severity at all follow-up points, ranging from 20% to 35% (median percent change from baseline), the company said.

For the ZLT-L-007 only group, there was about a 33% reduction in symptom severity at 30 days, and 71% and 78% reduction, respectively, at 60 and 90 days, suggesting a larger improvement in symptom severity than with pregabalin alone, the company said.

For the pregabalin plus ZLT-L-007 group, there was a moderate 20% reduction in symptom severity at 30 days, but a larger reduction at 60 and 90 days (50% and 72%, respectively), which indicates substantially greater improvement in symptom severity than with pregabalin alone, the company said.

The study also met secondary endpoints, including significant decreases in daily pain severity as measured by the Visual Analog Scale and measurable changes in the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire and Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory.

Dr. Doner noted that the top-line data showed “no serious adverse events, and participants’ blood pressure and other safety vitals remained unaffected throughout. This confirms that ZLT-L-007 is a well-tolerated product that delivers statistically significant pain relief, surpassing the levels achieved by Lyrica.”

The company plans to report additional insights from the full study, as they become available, during fiscal year 2023-2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new top-line results released by Zelira Therapeutics suggest.

“The implications of these results for patients are incredibly promising,” principal investigator Bryan Doner, DO, medical director of HealthyWays Integrated Wellness Solutions, Gibsonia, Pa., said in a news release.

“Through this rigorously designed study, we have demonstrated that ZLT-L-007 is a safe, effective, and well-tolerated alternative for patients who would typically seek a Lyrica-level of pain relief,” he added.

The observational, nonblinded trial tested the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ZLT-L-007 against pregabalin in 60 adults with diabetic nerve pain.

The study had three groups with 20 patients each (pregabalin alone, pregabalin plus ZLT-L-007, and ZLT-L-007 alone).

Top-line results show the study met its primary endpoint for change in daily pain severity as measured by the percent change from baseline at 30, 60, and 90 days on the Numerical Rating Scale.

For the pregabalin-only group, there was a reduction in symptom severity at all follow-up points, ranging from 20% to 35% (median percent change from baseline), the company said.

For the ZLT-L-007 only group, there was about a 33% reduction in symptom severity at 30 days, and 71% and 78% reduction, respectively, at 60 and 90 days, suggesting a larger improvement in symptom severity than with pregabalin alone, the company said.

For the pregabalin plus ZLT-L-007 group, there was a moderate 20% reduction in symptom severity at 30 days, but a larger reduction at 60 and 90 days (50% and 72%, respectively), which indicates substantially greater improvement in symptom severity than with pregabalin alone, the company said.

The study also met secondary endpoints, including significant decreases in daily pain severity as measured by the Visual Analog Scale and measurable changes in the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire and Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory.

Dr. Doner noted that the top-line data showed “no serious adverse events, and participants’ blood pressure and other safety vitals remained unaffected throughout. This confirms that ZLT-L-007 is a well-tolerated product that delivers statistically significant pain relief, surpassing the levels achieved by Lyrica.”

The company plans to report additional insights from the full study, as they become available, during fiscal year 2023-2024.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How a medical recoding may limit cancer patients’ options for breast reconstruction

On June 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services plans to reexamine how doctors are paid for a type of breast reconstruction known as DIEP flap, in which skin, fat, and blood vessels are harvested from a woman’s abdomen to create a new breast.

The procedure offers potential advantages over implants and operations that take muscle from the abdomen. But it’s also more expensive. If patients go outside an insurance network for the operation, it can cost more than $50,000. And, if insurers pay significantly less for the surgery as a result of the government’s decision, some in-network surgeons would stop offering it, a plastic surgeons group has argued.

The DIEP flap controversy, spotlighted by CBS News in January, illustrates arcane and indirect ways the federal government can influence which medical options are available – even to people with private insurance. Often, the answers come down to billing codes – which identify specific medical services on forms doctors submit for reimbursement – and the competing pleas of groups whose interests are riding on them.

Medical coding is the backbone for “how business gets done in medicine,” said Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, a physician at Washington University in St. Louis who researches health economics and policy.

CMS, the agency overseeing Medicare and Medicaid, maintains a list of codes representing thousands of medical services and products. It regularly evaluates whether to add codes or revise or remove existing ones. In 2022, it decided to eliminate a code that has enabled doctors to collect much more money for DIEP flap operations than for simpler types of breast reconstruction.

In 2006, CMS established an “S” code – S2068 – for what was then a relatively new procedure: breast reconstructions with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap). S codes temporarily fill gaps in a parallel system of billing codes known as CPT codes, which are maintained by the American Medical Association.

Codes don’t dictate the amounts private insurers pay for medical services; those reimbursements are generally worked out between insurance companies and medical providers. However, using the narrowly targeted S code, doctors and hospitals have been able to distinguish DIEP flap surgeries, which require complex microsurgical skills, from other forms of breast reconstruction that take less time to perform and generally yield lower insurance reimbursements.

CMS announced in 2022 that it planned to eliminate the S code at the end of 2024 – a move some doctors say would slash the amount surgeons are paid. (To be precise, CMS announced it would eliminate a series of three S codes for similar procedures, but some of the more outspoken critics have focused on one of them, S2068.) The agency’s decision is already changing the landscape of reconstructive surgery and creating anxiety for breast cancer patients.

Kate Getz, a single mother in Morton, Ill., learned she had cancer in January at age 30. As she grappled with her diagnosis, it was overwhelming to think about what her body would look like over the long term. She pictured herself getting married one day and wondered “how on earth I would be able to wear a wedding dress with only having one breast left,” she said.

She thought a DIEP flap was her best option and worried about having to undergo repeated surgeries if she got implants instead. Implants generally need to be replaced every 10 years or so. But after she spent more than a month trying to get answers about how her DIEP flap surgery would be covered, Ms. Getz’s insurer, Cigna, informed her it would use a lower-paying CPT code to reimburse her physician, Ms. Getz said. As far as she could see, that would have made it impossible for Ms. Getz to obtain the surgery.

Paying out of pocket was “not even an option.”

“I’m a single mom. We get by, right? But I’m not, not wealthy by any means,” she said.

Cost is not necessarily the only hurdle patients seeking DIEP flaps must overcome. Citing the complexity of the procedure, Ms. Getz said, a local plastic surgeon told her it would be difficult for him to perform. She ended up traveling from Illinois to Texas for the surgery.

The government’s plan to eliminate the three S codes was driven by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, a major lobbying organization for health insurance companies. In 2021, the group asked CMS to discontinue the codes, arguing that they were no longer needed because the AMA had updated a CPT code to explicitly include DIEP flap surgery and the related operations, according to a CMS document.

For years, the AMA advised doctors that the CPT code was appropriate for DIEP flap procedures. But after the government’s decision, at least two major insurance companies told doctors they would no longer reimburse them under the higher-paying codes, prompting a backlash.

Physicians and advocacy groups for breast cancer patients, such as the nonprofit organization Susan G. Komen, have argued that many plastic surgeons would stop providing DIEP flap procedures for women with private insurance because they wouldn’t get paid enough.

Lawmakers from both parties have asked the agency to keep the S code, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), who have had breast cancer, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.).

CMS at its June 1 meeting will consider whether to keep the three S codes or delay their expiration.

In a May 30 statement, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson Kelly Parsons reiterated the organization’s view that “there is no longer a need to keep the S codes.”

In a profit-driven health care system, there’s a tug of war over reimbursements between providers and insurance companies, often at the expense of patients, said Dr. Joynt Maddox.

“We’re in this sort of constant battle” between hospital chains and insurance companies “about who’s going to wield more power at the bargaining table,” Dr. Joynt Maddox said. “And the clinical piece of that often gets lost, because it’s not often the clinical benefit and the clinical priority and the patient centeredness that’s at the middle of these conversations.”

Elisabeth Potter, MD, a plastic surgeon who specializes in DIEP flap surgeries, decided to perform Ms. Getz’s surgery at whatever price Cigna would pay.

According to Fair Health, a nonprofit that provides information on health care costs, in Austin, Tex. – where Dr. Potter is based – an insurer might pay an in-network doctor $9,323 for the surgery when it’s billed using the CPT code and $18,037 under the S code. Those amounts are not averages; rather, Fair Health estimated that 80% of payment rates are lower than or equal to those amounts.

Dr. Potter said her Cigna reimbursement “is significantly lower.”

Weeks before her May surgery, Ms. Getz received big news – Cigna had reversed itself and would cover her surgery under the S code. It “felt like a real victory,” she said.

But she still fears for other patients.

“I’m still asking these companies to do right by women,” Ms. Getz said. “I’m still asking them to provide the procedures we need to reimburse them at rates where women have access to them regardless of their wealth.”

In a statement, Cigna spokesperson Justine Sessions said the insurer remains “committed to ensuring that our customers have affordable coverage and access to the full range of breast reconstruction procedures and to quality surgeons who perform these complex surgeries.”

Medical costs that health insurers cover generally are passed along to consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

For any type of breast reconstruction, there are benefits, risks, and trade-offs. A 2018 paper published in JAMA Surgery found that women who underwent DIEP flap surgery had higher odds of developing “reoperative complications” within 2 years than those who received artificial implants. However, DIEP flaps had lower odds of infection than implants.

Implants carry risks of additional surgery, pain, rupture, and even an uncommon type of immune system cancer.

Other flap procedures that take muscle from the abdomen can leave women with weakened abdominal walls and increase their risk of developing a hernia.

Academic research shows that insurance reimbursement affects which women can access DIEP flap breast reconstruction, creating a two-tiered system for private health insurance versus government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance generally pays physicians more than government coverage, and Medicare doesn’t use S codes.

Lynn Damitz, a physician and board vice president of health policy and advocacy for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said the group supports continuing the S code temporarily or indefinitely. If reimbursements drop, some doctors won’t perform DIEP flaps anymore.

A study published in February found that, of patients who used their own tissue for breast reconstruction, privately insured patients were more likely than publicly insured patients to receive DIEP flap reconstruction.

To Dr. Potter, that shows what will happen if private insurance payments plummet. “If you’re a Medicare provider and you’re not paid to do DIEP flaps, you never tell a patient that it’s an option. You won’t perform it,” Dr. Potter said. “If you take private insurance and all of a sudden your reimbursement rate is cut from $15,000 down to $3,500, you’re not going to do that surgery. And I’m not saying that that’s the right thing to do, but that’s what happens.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

On June 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services plans to reexamine how doctors are paid for a type of breast reconstruction known as DIEP flap, in which skin, fat, and blood vessels are harvested from a woman’s abdomen to create a new breast.

The procedure offers potential advantages over implants and operations that take muscle from the abdomen. But it’s also more expensive. If patients go outside an insurance network for the operation, it can cost more than $50,000. And, if insurers pay significantly less for the surgery as a result of the government’s decision, some in-network surgeons would stop offering it, a plastic surgeons group has argued.

The DIEP flap controversy, spotlighted by CBS News in January, illustrates arcane and indirect ways the federal government can influence which medical options are available – even to people with private insurance. Often, the answers come down to billing codes – which identify specific medical services on forms doctors submit for reimbursement – and the competing pleas of groups whose interests are riding on them.

Medical coding is the backbone for “how business gets done in medicine,” said Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, a physician at Washington University in St. Louis who researches health economics and policy.

CMS, the agency overseeing Medicare and Medicaid, maintains a list of codes representing thousands of medical services and products. It regularly evaluates whether to add codes or revise or remove existing ones. In 2022, it decided to eliminate a code that has enabled doctors to collect much more money for DIEP flap operations than for simpler types of breast reconstruction.

In 2006, CMS established an “S” code – S2068 – for what was then a relatively new procedure: breast reconstructions with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap). S codes temporarily fill gaps in a parallel system of billing codes known as CPT codes, which are maintained by the American Medical Association.

Codes don’t dictate the amounts private insurers pay for medical services; those reimbursements are generally worked out between insurance companies and medical providers. However, using the narrowly targeted S code, doctors and hospitals have been able to distinguish DIEP flap surgeries, which require complex microsurgical skills, from other forms of breast reconstruction that take less time to perform and generally yield lower insurance reimbursements.

CMS announced in 2022 that it planned to eliminate the S code at the end of 2024 – a move some doctors say would slash the amount surgeons are paid. (To be precise, CMS announced it would eliminate a series of three S codes for similar procedures, but some of the more outspoken critics have focused on one of them, S2068.) The agency’s decision is already changing the landscape of reconstructive surgery and creating anxiety for breast cancer patients.

Kate Getz, a single mother in Morton, Ill., learned she had cancer in January at age 30. As she grappled with her diagnosis, it was overwhelming to think about what her body would look like over the long term. She pictured herself getting married one day and wondered “how on earth I would be able to wear a wedding dress with only having one breast left,” she said.

She thought a DIEP flap was her best option and worried about having to undergo repeated surgeries if she got implants instead. Implants generally need to be replaced every 10 years or so. But after she spent more than a month trying to get answers about how her DIEP flap surgery would be covered, Ms. Getz’s insurer, Cigna, informed her it would use a lower-paying CPT code to reimburse her physician, Ms. Getz said. As far as she could see, that would have made it impossible for Ms. Getz to obtain the surgery.

Paying out of pocket was “not even an option.”

“I’m a single mom. We get by, right? But I’m not, not wealthy by any means,” she said.

Cost is not necessarily the only hurdle patients seeking DIEP flaps must overcome. Citing the complexity of the procedure, Ms. Getz said, a local plastic surgeon told her it would be difficult for him to perform. She ended up traveling from Illinois to Texas for the surgery.

The government’s plan to eliminate the three S codes was driven by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, a major lobbying organization for health insurance companies. In 2021, the group asked CMS to discontinue the codes, arguing that they were no longer needed because the AMA had updated a CPT code to explicitly include DIEP flap surgery and the related operations, according to a CMS document.

For years, the AMA advised doctors that the CPT code was appropriate for DIEP flap procedures. But after the government’s decision, at least two major insurance companies told doctors they would no longer reimburse them under the higher-paying codes, prompting a backlash.

Physicians and advocacy groups for breast cancer patients, such as the nonprofit organization Susan G. Komen, have argued that many plastic surgeons would stop providing DIEP flap procedures for women with private insurance because they wouldn’t get paid enough.

Lawmakers from both parties have asked the agency to keep the S code, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), who have had breast cancer, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.).

CMS at its June 1 meeting will consider whether to keep the three S codes or delay their expiration.

In a May 30 statement, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson Kelly Parsons reiterated the organization’s view that “there is no longer a need to keep the S codes.”

In a profit-driven health care system, there’s a tug of war over reimbursements between providers and insurance companies, often at the expense of patients, said Dr. Joynt Maddox.

“We’re in this sort of constant battle” between hospital chains and insurance companies “about who’s going to wield more power at the bargaining table,” Dr. Joynt Maddox said. “And the clinical piece of that often gets lost, because it’s not often the clinical benefit and the clinical priority and the patient centeredness that’s at the middle of these conversations.”

Elisabeth Potter, MD, a plastic surgeon who specializes in DIEP flap surgeries, decided to perform Ms. Getz’s surgery at whatever price Cigna would pay.

According to Fair Health, a nonprofit that provides information on health care costs, in Austin, Tex. – where Dr. Potter is based – an insurer might pay an in-network doctor $9,323 for the surgery when it’s billed using the CPT code and $18,037 under the S code. Those amounts are not averages; rather, Fair Health estimated that 80% of payment rates are lower than or equal to those amounts.

Dr. Potter said her Cigna reimbursement “is significantly lower.”

Weeks before her May surgery, Ms. Getz received big news – Cigna had reversed itself and would cover her surgery under the S code. It “felt like a real victory,” she said.

But she still fears for other patients.

“I’m still asking these companies to do right by women,” Ms. Getz said. “I’m still asking them to provide the procedures we need to reimburse them at rates where women have access to them regardless of their wealth.”

In a statement, Cigna spokesperson Justine Sessions said the insurer remains “committed to ensuring that our customers have affordable coverage and access to the full range of breast reconstruction procedures and to quality surgeons who perform these complex surgeries.”

Medical costs that health insurers cover generally are passed along to consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

For any type of breast reconstruction, there are benefits, risks, and trade-offs. A 2018 paper published in JAMA Surgery found that women who underwent DIEP flap surgery had higher odds of developing “reoperative complications” within 2 years than those who received artificial implants. However, DIEP flaps had lower odds of infection than implants.

Implants carry risks of additional surgery, pain, rupture, and even an uncommon type of immune system cancer.

Other flap procedures that take muscle from the abdomen can leave women with weakened abdominal walls and increase their risk of developing a hernia.

Academic research shows that insurance reimbursement affects which women can access DIEP flap breast reconstruction, creating a two-tiered system for private health insurance versus government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance generally pays physicians more than government coverage, and Medicare doesn’t use S codes.

Lynn Damitz, a physician and board vice president of health policy and advocacy for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said the group supports continuing the S code temporarily or indefinitely. If reimbursements drop, some doctors won’t perform DIEP flaps anymore.

A study published in February found that, of patients who used their own tissue for breast reconstruction, privately insured patients were more likely than publicly insured patients to receive DIEP flap reconstruction.

To Dr. Potter, that shows what will happen if private insurance payments plummet. “If you’re a Medicare provider and you’re not paid to do DIEP flaps, you never tell a patient that it’s an option. You won’t perform it,” Dr. Potter said. “If you take private insurance and all of a sudden your reimbursement rate is cut from $15,000 down to $3,500, you’re not going to do that surgery. And I’m not saying that that’s the right thing to do, but that’s what happens.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

On June 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services plans to reexamine how doctors are paid for a type of breast reconstruction known as DIEP flap, in which skin, fat, and blood vessels are harvested from a woman’s abdomen to create a new breast.

The procedure offers potential advantages over implants and operations that take muscle from the abdomen. But it’s also more expensive. If patients go outside an insurance network for the operation, it can cost more than $50,000. And, if insurers pay significantly less for the surgery as a result of the government’s decision, some in-network surgeons would stop offering it, a plastic surgeons group has argued.

The DIEP flap controversy, spotlighted by CBS News in January, illustrates arcane and indirect ways the federal government can influence which medical options are available – even to people with private insurance. Often, the answers come down to billing codes – which identify specific medical services on forms doctors submit for reimbursement – and the competing pleas of groups whose interests are riding on them.

Medical coding is the backbone for “how business gets done in medicine,” said Karen Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, a physician at Washington University in St. Louis who researches health economics and policy.

CMS, the agency overseeing Medicare and Medicaid, maintains a list of codes representing thousands of medical services and products. It regularly evaluates whether to add codes or revise or remove existing ones. In 2022, it decided to eliminate a code that has enabled doctors to collect much more money for DIEP flap operations than for simpler types of breast reconstruction.

In 2006, CMS established an “S” code – S2068 – for what was then a relatively new procedure: breast reconstructions with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (DIEP flap). S codes temporarily fill gaps in a parallel system of billing codes known as CPT codes, which are maintained by the American Medical Association.

Codes don’t dictate the amounts private insurers pay for medical services; those reimbursements are generally worked out between insurance companies and medical providers. However, using the narrowly targeted S code, doctors and hospitals have been able to distinguish DIEP flap surgeries, which require complex microsurgical skills, from other forms of breast reconstruction that take less time to perform and generally yield lower insurance reimbursements.

CMS announced in 2022 that it planned to eliminate the S code at the end of 2024 – a move some doctors say would slash the amount surgeons are paid. (To be precise, CMS announced it would eliminate a series of three S codes for similar procedures, but some of the more outspoken critics have focused on one of them, S2068.) The agency’s decision is already changing the landscape of reconstructive surgery and creating anxiety for breast cancer patients.

Kate Getz, a single mother in Morton, Ill., learned she had cancer in January at age 30. As she grappled with her diagnosis, it was overwhelming to think about what her body would look like over the long term. She pictured herself getting married one day and wondered “how on earth I would be able to wear a wedding dress with only having one breast left,” she said.

She thought a DIEP flap was her best option and worried about having to undergo repeated surgeries if she got implants instead. Implants generally need to be replaced every 10 years or so. But after she spent more than a month trying to get answers about how her DIEP flap surgery would be covered, Ms. Getz’s insurer, Cigna, informed her it would use a lower-paying CPT code to reimburse her physician, Ms. Getz said. As far as she could see, that would have made it impossible for Ms. Getz to obtain the surgery.

Paying out of pocket was “not even an option.”

“I’m a single mom. We get by, right? But I’m not, not wealthy by any means,” she said.

Cost is not necessarily the only hurdle patients seeking DIEP flaps must overcome. Citing the complexity of the procedure, Ms. Getz said, a local plastic surgeon told her it would be difficult for him to perform. She ended up traveling from Illinois to Texas for the surgery.

The government’s plan to eliminate the three S codes was driven by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, a major lobbying organization for health insurance companies. In 2021, the group asked CMS to discontinue the codes, arguing that they were no longer needed because the AMA had updated a CPT code to explicitly include DIEP flap surgery and the related operations, according to a CMS document.

For years, the AMA advised doctors that the CPT code was appropriate for DIEP flap procedures. But after the government’s decision, at least two major insurance companies told doctors they would no longer reimburse them under the higher-paying codes, prompting a backlash.

Physicians and advocacy groups for breast cancer patients, such as the nonprofit organization Susan G. Komen, have argued that many plastic surgeons would stop providing DIEP flap procedures for women with private insurance because they wouldn’t get paid enough.

Lawmakers from both parties have asked the agency to keep the S code, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) and Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), who have had breast cancer, and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.).

CMS at its June 1 meeting will consider whether to keep the three S codes or delay their expiration.

In a May 30 statement, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association spokesperson Kelly Parsons reiterated the organization’s view that “there is no longer a need to keep the S codes.”

In a profit-driven health care system, there’s a tug of war over reimbursements between providers and insurance companies, often at the expense of patients, said Dr. Joynt Maddox.

“We’re in this sort of constant battle” between hospital chains and insurance companies “about who’s going to wield more power at the bargaining table,” Dr. Joynt Maddox said. “And the clinical piece of that often gets lost, because it’s not often the clinical benefit and the clinical priority and the patient centeredness that’s at the middle of these conversations.”

Elisabeth Potter, MD, a plastic surgeon who specializes in DIEP flap surgeries, decided to perform Ms. Getz’s surgery at whatever price Cigna would pay.

According to Fair Health, a nonprofit that provides information on health care costs, in Austin, Tex. – where Dr. Potter is based – an insurer might pay an in-network doctor $9,323 for the surgery when it’s billed using the CPT code and $18,037 under the S code. Those amounts are not averages; rather, Fair Health estimated that 80% of payment rates are lower than or equal to those amounts.

Dr. Potter said her Cigna reimbursement “is significantly lower.”

Weeks before her May surgery, Ms. Getz received big news – Cigna had reversed itself and would cover her surgery under the S code. It “felt like a real victory,” she said.

But she still fears for other patients.

“I’m still asking these companies to do right by women,” Ms. Getz said. “I’m still asking them to provide the procedures we need to reimburse them at rates where women have access to them regardless of their wealth.”

In a statement, Cigna spokesperson Justine Sessions said the insurer remains “committed to ensuring that our customers have affordable coverage and access to the full range of breast reconstruction procedures and to quality surgeons who perform these complex surgeries.”

Medical costs that health insurers cover generally are passed along to consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

For any type of breast reconstruction, there are benefits, risks, and trade-offs. A 2018 paper published in JAMA Surgery found that women who underwent DIEP flap surgery had higher odds of developing “reoperative complications” within 2 years than those who received artificial implants. However, DIEP flaps had lower odds of infection than implants.

Implants carry risks of additional surgery, pain, rupture, and even an uncommon type of immune system cancer.

Other flap procedures that take muscle from the abdomen can leave women with weakened abdominal walls and increase their risk of developing a hernia.

Academic research shows that insurance reimbursement affects which women can access DIEP flap breast reconstruction, creating a two-tiered system for private health insurance versus government programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance generally pays physicians more than government coverage, and Medicare doesn’t use S codes.

Lynn Damitz, a physician and board vice president of health policy and advocacy for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said the group supports continuing the S code temporarily or indefinitely. If reimbursements drop, some doctors won’t perform DIEP flaps anymore.

A study published in February found that, of patients who used their own tissue for breast reconstruction, privately insured patients were more likely than publicly insured patients to receive DIEP flap reconstruction.

To Dr. Potter, that shows what will happen if private insurance payments plummet. “If you’re a Medicare provider and you’re not paid to do DIEP flaps, you never tell a patient that it’s an option. You won’t perform it,” Dr. Potter said. “If you take private insurance and all of a sudden your reimbursement rate is cut from $15,000 down to $3,500, you’re not going to do that surgery. And I’m not saying that that’s the right thing to do, but that’s what happens.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Diagnosis and Management of Recurrent and Complicated UTIs in Women: Controversies and Dilemmas

In this piece, Dr. Mickey Karram & Dr. Roger R. Dmochowski discuss how although UTIs have demonstrated widespread occurrence and significant healthcare costs, there is not yet a “gold standard” definition for complicated UTI. To avoid the overuse of antimicrobial agents and their associated issues, it is vital that clinicians evaluate test results in the context of a patient’s overall risk and history of UTIs and current clinical presentation and utilize testing that enables more informed decisions.

In this piece, Dr. Mickey Karram & Dr. Roger R. Dmochowski discuss how although UTIs have demonstrated widespread occurrence and significant healthcare costs, there is not yet a “gold standard” definition for complicated UTI. To avoid the overuse of antimicrobial agents and their associated issues, it is vital that clinicians evaluate test results in the context of a patient’s overall risk and history of UTIs and current clinical presentation and utilize testing that enables more informed decisions.

In this piece, Dr. Mickey Karram & Dr. Roger R. Dmochowski discuss how although UTIs have demonstrated widespread occurrence and significant healthcare costs, there is not yet a “gold standard” definition for complicated UTI. To avoid the overuse of antimicrobial agents and their associated issues, it is vital that clinicians evaluate test results in the context of a patient’s overall risk and history of UTIs and current clinical presentation and utilize testing that enables more informed decisions.

Family placement better for deprived kids than institutions

SAN FRANCISCO – results of a new study suggest.

The study shows that sustained recovery is possible after severe, early-life adversity, study author Kathryn L. Humphreys, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychology and human development, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview.

“Given the strong evidence from the present study, I hope physicians will play a role in promoting family placements as an alternative to institutional care for children who have been orphaned,” she said.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association and were published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Millions of children around the world experience psychosocial deprivation while living in institutions, and many more are neglected in their families of origin. In addition, about 6.7 million children lost a parent or caregiver during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In particular, Romania has a history of institutionalizing children. Through decades of repressive policies from the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, child abandonment became a national disaster. Families couldn’t afford to keep their children and were encouraged to turn them over to the state.

The current study was part of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, initiated in 2001 to examine the impact of high-quality, family-based care on development. It included 136 Romanian children (mean age, about 22 months) who were abandoned at or shortly after birth and were placed in an institution.

Researchers randomly assigned each toddler to 1 of 56 foster families or to continue living in an institution (care as usual). The researchers had to create a foster care network, because such care was extremely limited at the start of the study.

Providing stimulating care

Foster parents in the study received regular support from social workers and U.S.-based psychologists. They were encouraged to “make a commitment to treat the child as if it was their own, providing sensitive, stimulating, and nurturing care, not just in the short term but for their whole life,” said Dr. Humphreys.

Foster care programs in the United States have been criticized for focusing on short-term care, she said. “It’s really just a bed to sleep on, clothes to wear, and food to eat rather than the psychological component we think is really important for child development.”

For the study, the researchers assessed the children across multiple developmental domains at baseline and at ages 30, 42, and 54 months. They conducted additional assessments when the kids were aged 8, 12, and 16-18 years.

The primary outcomes were cognitive functioning (IQ), physical growth (height, weight, head circumference), brain electrical activity (relative electroencephalography power in the alpha frequency band), and symptoms of five types of psychopathology (disinhibited social engagement disorder, reactive attachment disorder, ADHD symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and internalizing symptoms).

From over 7,000 observations analyzed across follow-ups, the investigators found that the intervention had an overall significant effect on cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes when considered collectively across waves (beta, 0.26; 95% confidence interval, 0.07-0.46; P = .012). Compared to children who received care as usual, those in foster homes had significantly higher average IQ scores (P < .001) and physical size (P = .008).

The intervention had an overall beneficial effect in regard to psychopathology. The greatest impact involved a reduction in symptoms of reactive attachment disorder (P < .001).

“There are a few forms of psychopathology that seem to almost entirely occur after severe neglect, including reactive attachment disorder; we think of these as disorders of social relatedness that derive from aberrant or insufficient early caregiving experiences,” said Dr. Humphreys. “Being placed in a family reduced the symptoms of reactive attachment disorder to pretty much nonexistent.”

To a lesser extent, the intervention reduced symptoms of disinhibited social engagement disorder. The foster care group also had significantly fewer internalizing symptoms than did children in the care-as-usual group.

But there was no significant overall effect of the intervention on symptoms of ADHD or externalizing problems.

Positive effects persisted

For the most part, the positive effects of the intervention on children’s functioning persisted during nearly 2 decades of follow-up. The impact of the intervention “can be described as rapidly apparent by age 30 months and sustained through late adolescence,” wrote the authors.

Regarding the impact of age at the time of placement, the study found that, compared with children placed into foster care later, those who entered foster care earlier (younger than 33 months) had significantly higher IQ scores and relative alpha power, but there was no difference in physical growth.

For some outcomes, the benefits of earlier placement were apparent in early childhood but faded by adolescence. But Dr. Humphreys noted all placements were early by most definitions.

The researchers also assessed stability of foster care placements. Children were considered “stable” if they remained with their original foster family; they were considered “disrupted” if they no longer resided with the family.

Here, the study found some “striking results,” said Dr. Humphreys. The effect of placement stability was largest in adolescence, when, overall, those who had remained with their original foster family had better cognitive and physical outcomes and less severe symptoms of psychopathology compared to those who experienced placement disruptions.

As for sex differences, “it’s a mixed bag,” said Dr. Humphreys, although overall, “we didn’t see strong evidence of sex differences” in terms of outcomes.

The investigators were unable to examine trajectories of children’s functioning, which would have provided important information on aspects such as rate of growth and the shape of growth curves. Specific features of the institutional or foster care environment in Bucharest during the study may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings.

Absolutely unique project

The study examined an “absolutely unique project” and had “very exciting” results that should have “important clinical implications,” commented the American Journal of Psychiatry editor-in-chief Ned Kalin, MD, Hedberg Professor and chair, department of psychiatry, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The findings are “pretty dramatic,” added Dr. Kalin. “This is probably the study to be thinking about when considering the future of treatment and interventions in children who have suffered from this type of neglect, which is unfortunately extremely common worldwide, including in the U.S.”

In particular, the findings regarding improved psychopathology “bode well for the future,” said Dr. Kalin. “We know these types of problems are risk factors for the later development of depression and anxiety disorders. It will be really interesting to find out, but my guess is these kids will be protected as they mature further.”

The study was supported by the NIH, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Palix Foundation, and the Jacobs Foundation. Dr. Humphreys has received research funding from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Caplan Foundation, the Jacobs Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the NIH, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, and Vanderbilt University; she has received honoraria from the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Future Directions Forum, Learning Grove, the University of Iowa, the University of Texas at Austin, and ZERO TO THREE.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – results of a new study suggest.

The study shows that sustained recovery is possible after severe, early-life adversity, study author Kathryn L. Humphreys, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychology and human development, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview.

“Given the strong evidence from the present study, I hope physicians will play a role in promoting family placements as an alternative to institutional care for children who have been orphaned,” she said.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association and were published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Millions of children around the world experience psychosocial deprivation while living in institutions, and many more are neglected in their families of origin. In addition, about 6.7 million children lost a parent or caregiver during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In particular, Romania has a history of institutionalizing children. Through decades of repressive policies from the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, child abandonment became a national disaster. Families couldn’t afford to keep their children and were encouraged to turn them over to the state.

The current study was part of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, initiated in 2001 to examine the impact of high-quality, family-based care on development. It included 136 Romanian children (mean age, about 22 months) who were abandoned at or shortly after birth and were placed in an institution.

Researchers randomly assigned each toddler to 1 of 56 foster families or to continue living in an institution (care as usual). The researchers had to create a foster care network, because such care was extremely limited at the start of the study.

Providing stimulating care

Foster parents in the study received regular support from social workers and U.S.-based psychologists. They were encouraged to “make a commitment to treat the child as if it was their own, providing sensitive, stimulating, and nurturing care, not just in the short term but for their whole life,” said Dr. Humphreys.

Foster care programs in the United States have been criticized for focusing on short-term care, she said. “It’s really just a bed to sleep on, clothes to wear, and food to eat rather than the psychological component we think is really important for child development.”

For the study, the researchers assessed the children across multiple developmental domains at baseline and at ages 30, 42, and 54 months. They conducted additional assessments when the kids were aged 8, 12, and 16-18 years.

The primary outcomes were cognitive functioning (IQ), physical growth (height, weight, head circumference), brain electrical activity (relative electroencephalography power in the alpha frequency band), and symptoms of five types of psychopathology (disinhibited social engagement disorder, reactive attachment disorder, ADHD symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and internalizing symptoms).

From over 7,000 observations analyzed across follow-ups, the investigators found that the intervention had an overall significant effect on cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes when considered collectively across waves (beta, 0.26; 95% confidence interval, 0.07-0.46; P = .012). Compared to children who received care as usual, those in foster homes had significantly higher average IQ scores (P < .001) and physical size (P = .008).

The intervention had an overall beneficial effect in regard to psychopathology. The greatest impact involved a reduction in symptoms of reactive attachment disorder (P < .001).

“There are a few forms of psychopathology that seem to almost entirely occur after severe neglect, including reactive attachment disorder; we think of these as disorders of social relatedness that derive from aberrant or insufficient early caregiving experiences,” said Dr. Humphreys. “Being placed in a family reduced the symptoms of reactive attachment disorder to pretty much nonexistent.”

To a lesser extent, the intervention reduced symptoms of disinhibited social engagement disorder. The foster care group also had significantly fewer internalizing symptoms than did children in the care-as-usual group.

But there was no significant overall effect of the intervention on symptoms of ADHD or externalizing problems.

Positive effects persisted

For the most part, the positive effects of the intervention on children’s functioning persisted during nearly 2 decades of follow-up. The impact of the intervention “can be described as rapidly apparent by age 30 months and sustained through late adolescence,” wrote the authors.

Regarding the impact of age at the time of placement, the study found that, compared with children placed into foster care later, those who entered foster care earlier (younger than 33 months) had significantly higher IQ scores and relative alpha power, but there was no difference in physical growth.

For some outcomes, the benefits of earlier placement were apparent in early childhood but faded by adolescence. But Dr. Humphreys noted all placements were early by most definitions.

The researchers also assessed stability of foster care placements. Children were considered “stable” if they remained with their original foster family; they were considered “disrupted” if they no longer resided with the family.

Here, the study found some “striking results,” said Dr. Humphreys. The effect of placement stability was largest in adolescence, when, overall, those who had remained with their original foster family had better cognitive and physical outcomes and less severe symptoms of psychopathology compared to those who experienced placement disruptions.

As for sex differences, “it’s a mixed bag,” said Dr. Humphreys, although overall, “we didn’t see strong evidence of sex differences” in terms of outcomes.

The investigators were unable to examine trajectories of children’s functioning, which would have provided important information on aspects such as rate of growth and the shape of growth curves. Specific features of the institutional or foster care environment in Bucharest during the study may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings.

Absolutely unique project

The study examined an “absolutely unique project” and had “very exciting” results that should have “important clinical implications,” commented the American Journal of Psychiatry editor-in-chief Ned Kalin, MD, Hedberg Professor and chair, department of psychiatry, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The findings are “pretty dramatic,” added Dr. Kalin. “This is probably the study to be thinking about when considering the future of treatment and interventions in children who have suffered from this type of neglect, which is unfortunately extremely common worldwide, including in the U.S.”

In particular, the findings regarding improved psychopathology “bode well for the future,” said Dr. Kalin. “We know these types of problems are risk factors for the later development of depression and anxiety disorders. It will be really interesting to find out, but my guess is these kids will be protected as they mature further.”

The study was supported by the NIH, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Palix Foundation, and the Jacobs Foundation. Dr. Humphreys has received research funding from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Caplan Foundation, the Jacobs Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the NIH, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, and Vanderbilt University; she has received honoraria from the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Future Directions Forum, Learning Grove, the University of Iowa, the University of Texas at Austin, and ZERO TO THREE.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – results of a new study suggest.

The study shows that sustained recovery is possible after severe, early-life adversity, study author Kathryn L. Humphreys, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychology and human development, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview.

“Given the strong evidence from the present study, I hope physicians will play a role in promoting family placements as an alternative to institutional care for children who have been orphaned,” she said.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association and were published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Millions of children around the world experience psychosocial deprivation while living in institutions, and many more are neglected in their families of origin. In addition, about 6.7 million children lost a parent or caregiver during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In particular, Romania has a history of institutionalizing children. Through decades of repressive policies from the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, child abandonment became a national disaster. Families couldn’t afford to keep their children and were encouraged to turn them over to the state.

The current study was part of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, initiated in 2001 to examine the impact of high-quality, family-based care on development. It included 136 Romanian children (mean age, about 22 months) who were abandoned at or shortly after birth and were placed in an institution.

Researchers randomly assigned each toddler to 1 of 56 foster families or to continue living in an institution (care as usual). The researchers had to create a foster care network, because such care was extremely limited at the start of the study.

Providing stimulating care

Foster parents in the study received regular support from social workers and U.S.-based psychologists. They were encouraged to “make a commitment to treat the child as if it was their own, providing sensitive, stimulating, and nurturing care, not just in the short term but for their whole life,” said Dr. Humphreys.

Foster care programs in the United States have been criticized for focusing on short-term care, she said. “It’s really just a bed to sleep on, clothes to wear, and food to eat rather than the psychological component we think is really important for child development.”

For the study, the researchers assessed the children across multiple developmental domains at baseline and at ages 30, 42, and 54 months. They conducted additional assessments when the kids were aged 8, 12, and 16-18 years.

The primary outcomes were cognitive functioning (IQ), physical growth (height, weight, head circumference), brain electrical activity (relative electroencephalography power in the alpha frequency band), and symptoms of five types of psychopathology (disinhibited social engagement disorder, reactive attachment disorder, ADHD symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and internalizing symptoms).

From over 7,000 observations analyzed across follow-ups, the investigators found that the intervention had an overall significant effect on cognitive, physical, and neural outcomes when considered collectively across waves (beta, 0.26; 95% confidence interval, 0.07-0.46; P = .012). Compared to children who received care as usual, those in foster homes had significantly higher average IQ scores (P < .001) and physical size (P = .008).

The intervention had an overall beneficial effect in regard to psychopathology. The greatest impact involved a reduction in symptoms of reactive attachment disorder (P < .001).

“There are a few forms of psychopathology that seem to almost entirely occur after severe neglect, including reactive attachment disorder; we think of these as disorders of social relatedness that derive from aberrant or insufficient early caregiving experiences,” said Dr. Humphreys. “Being placed in a family reduced the symptoms of reactive attachment disorder to pretty much nonexistent.”

To a lesser extent, the intervention reduced symptoms of disinhibited social engagement disorder. The foster care group also had significantly fewer internalizing symptoms than did children in the care-as-usual group.

But there was no significant overall effect of the intervention on symptoms of ADHD or externalizing problems.

Positive effects persisted

For the most part, the positive effects of the intervention on children’s functioning persisted during nearly 2 decades of follow-up. The impact of the intervention “can be described as rapidly apparent by age 30 months and sustained through late adolescence,” wrote the authors.

Regarding the impact of age at the time of placement, the study found that, compared with children placed into foster care later, those who entered foster care earlier (younger than 33 months) had significantly higher IQ scores and relative alpha power, but there was no difference in physical growth.

For some outcomes, the benefits of earlier placement were apparent in early childhood but faded by adolescence. But Dr. Humphreys noted all placements were early by most definitions.

The researchers also assessed stability of foster care placements. Children were considered “stable” if they remained with their original foster family; they were considered “disrupted” if they no longer resided with the family.

Here, the study found some “striking results,” said Dr. Humphreys. The effect of placement stability was largest in adolescence, when, overall, those who had remained with their original foster family had better cognitive and physical outcomes and less severe symptoms of psychopathology compared to those who experienced placement disruptions.

As for sex differences, “it’s a mixed bag,” said Dr. Humphreys, although overall, “we didn’t see strong evidence of sex differences” in terms of outcomes.

The investigators were unable to examine trajectories of children’s functioning, which would have provided important information on aspects such as rate of growth and the shape of growth curves. Specific features of the institutional or foster care environment in Bucharest during the study may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings.

Absolutely unique project

The study examined an “absolutely unique project” and had “very exciting” results that should have “important clinical implications,” commented the American Journal of Psychiatry editor-in-chief Ned Kalin, MD, Hedberg Professor and chair, department of psychiatry, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The findings are “pretty dramatic,” added Dr. Kalin. “This is probably the study to be thinking about when considering the future of treatment and interventions in children who have suffered from this type of neglect, which is unfortunately extremely common worldwide, including in the U.S.”

In particular, the findings regarding improved psychopathology “bode well for the future,” said Dr. Kalin. “We know these types of problems are risk factors for the later development of depression and anxiety disorders. It will be really interesting to find out, but my guess is these kids will be protected as they mature further.”

The study was supported by the NIH, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Palix Foundation, and the Jacobs Foundation. Dr. Humphreys has received research funding from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Caplan Foundation, the Jacobs Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the NIH, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, and Vanderbilt University; she has received honoraria from the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Future Directions Forum, Learning Grove, the University of Iowa, the University of Texas at Austin, and ZERO TO THREE.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT APA 2023

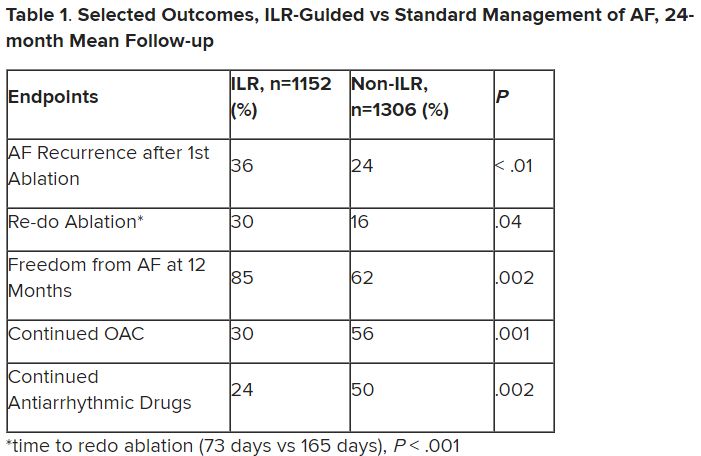

ECG implant tightens AFib management, improves outcomes in MONITOR-AF

Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

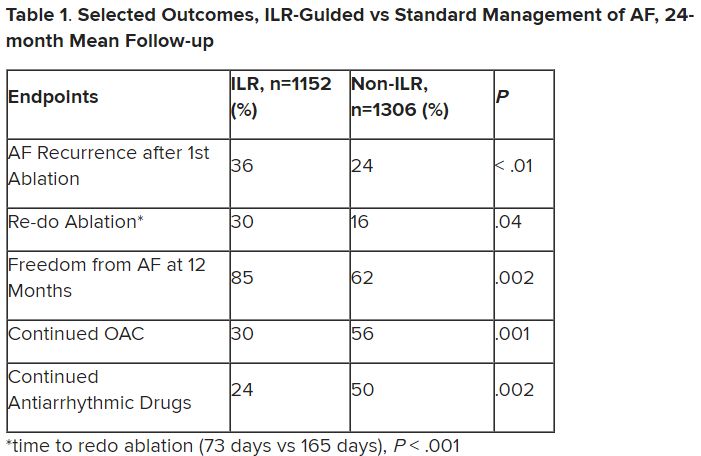

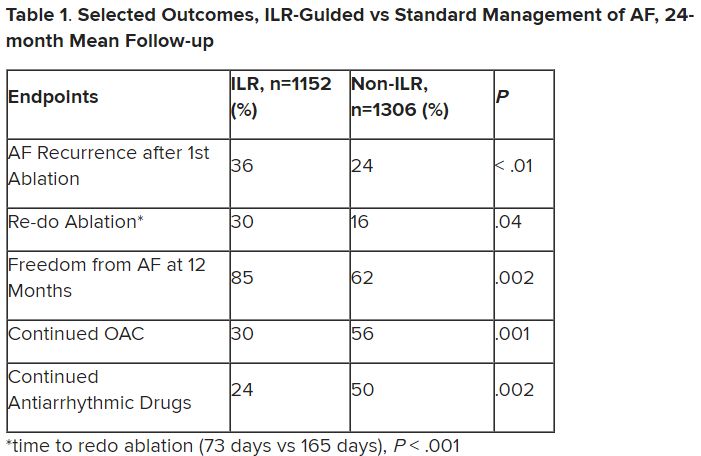

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

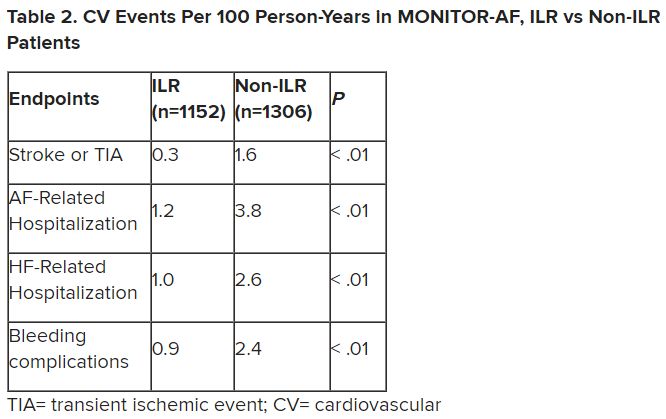

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

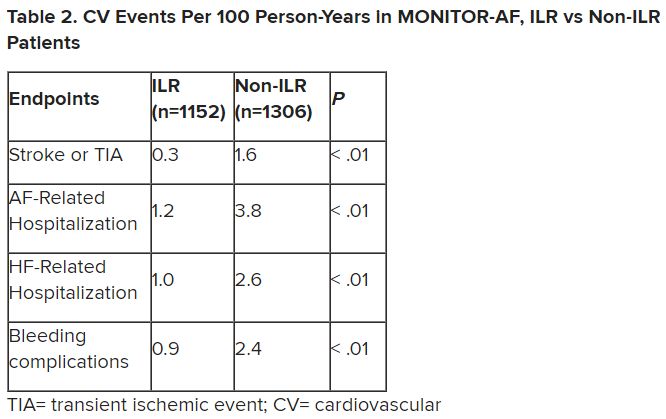

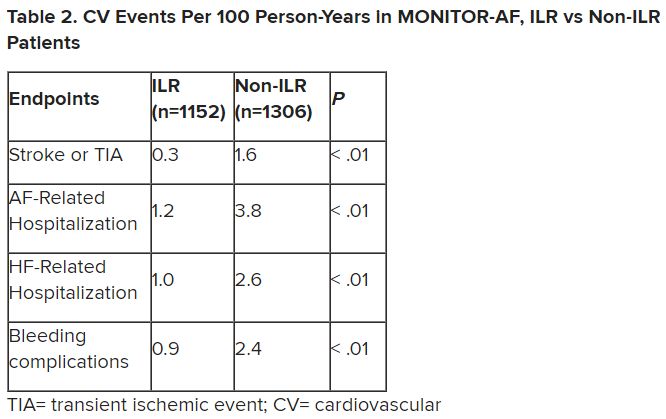

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.

MONITOR-AF included 2,458 patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who either were implanted with or did not receive an ILR from 2018 to 2021 and were followed for at least 12 months.

The two groups were similar, Dr. Lakkireddy reported, with respect to demographics and baseline history AFib, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, neurovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Lakkireddy said a subgroup analysis is forthcoming, but that he’d “intuitively” think that the 15%-20% of AFib patients who are asymptomatic would gain the most from the ILR monitoring approach. There is already evidence that such patients tend to have the worst AFib outcomes, often receiving an AFib diagnosis only after presenting with consequences such as stroke or heart failure.

Dr. Lakkireddy disclosed receiving research grants, modest honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott, Janssen, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Atricure, Northeast Scientific, and Acutus. Dr. Morin disclosed receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.

MONITOR-AF included 2,458 patients with paroxysmal or persistent AFib who either were implanted with or did not receive an ILR from 2018 to 2021 and were followed for at least 12 months.

The two groups were similar, Dr. Lakkireddy reported, with respect to demographics and baseline history AFib, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coronary disease, neurovascular events, peripheral artery disease, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Lakkireddy said a subgroup analysis is forthcoming, but that he’d “intuitively” think that the 15%-20% of AFib patients who are asymptomatic would gain the most from the ILR monitoring approach. There is already evidence that such patients tend to have the worst AFib outcomes, often receiving an AFib diagnosis only after presenting with consequences such as stroke or heart failure.

Dr. Lakkireddy disclosed receiving research grants, modest honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott, Janssen, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Atricure, Northeast Scientific, and Acutus. Dr. Morin disclosed receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from Abbott and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Zoll Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension “often require long-term care through long-term monitoring,” observed a researcher, and “we know that continuous monitoring is superior to intermittent monitoring for long-term outcomes.”

So maybe practice should rely more on continuous ECG monitoring for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib), also a chronic condition, proposed Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute, Overland Park, Kan., in presenting a new analysis at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

(ILRs), compared with standard care. The latter could include intermittent 12-lead ECG, Holter, or other intermittent monitoring at physicians’ discretion.

Patients with AFib and the ECG implants in the MONITOR-AF study, which was not randomized and therefore only suggestive, were managed “more efficiently” with greater access to electrophysiologists (P < .01) and adherence to oral anticoagulants (P = .020) and other medications.

Followed for a mean of 2 years, patients with ILRs were more likely to undergo catheter ablation, and their time to a catheter ablation “was impressively shorter, 153 days versus 426 days” (P < .001), Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The ILR group also had fewer strokes and bleeding complications and were less likely to be hospitalized for AFib-related reasons, he said, because “a lot of these patients were caught ahead of time through the remote monitoring.”

For example, ILR patients had fewer heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, likely because “you’re not allowing these patients to remain with untreated rapid ventricular rates for a long period of time. You intervene early, thereby mitigating the onset of heart failure.”

Indeed, Dr. Lakkireddy said, their cumulative rate of any cardiovascular complication was “dramatically lower” – 3.4 versus 10.4 events per 100 person-years (P < .001).

Certainly, a routine recommendation to consider AFib patients for continuous monitoring would require randomized-trial evidence, he acknowledged. “This is an observation registry and proof of concept from a very heterogeneous cohort of patients. There were no obvious set criteria for ILR implantation.”

Nonetheless, “continuous and dynamic monitoring enabled quicker decision-making and patient management,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. “Especially in those patients who may have silent atrial fibrillation, an ILR could significantly mitigate the risk of complications from stroke and heart failure exacerbations.”

Several randomized trials have supported “earlier, more aggressive treatment” for AFib, including EAST-AFNET4, EARLY-AF, and CABANA, observed Daniel Morin, MD, MPH, of Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, as the invited discussant for Dr. Lakkireddy’s presentation.

So, he continued, if the goal is to “get every single AFib patient to ablation just as soon as possible,” then maybe MONITOR-AF supports the use of ILRs in such cases.

Indeed, it is “certainly possible” that the continuous stream of data from ILRs “allows faster progression of therapy and possibly even better outcomes” as MONITOR-AF suggests, said Dr. Morin, who is director of electrophysiology research at his center.

Moreover, ILR data could potentially “support shared decision-making perhaps by convincing the patient, and maybe their insurers, that we should move forward with ablation.”

But given the study’s observational, registry-based nature, the MONITOR-AF analysis is limited by potential confounders that complicate its interpretation.

For example, Dr. Morin continued, all ILR patients but only 60% of those on standard care˙ had access to an electrophysiologist (P = .001). That means “less access to some antiarrhythmic medications and certainly far less access to ablation therapy.”

Moreover, “during shared decision-making, a patient who sees the results of their ILR monitoring may be more prone to seek out or to accept earlier, more definitive therapy via ablation,” he said. “The presence of an ILR may then be a good way to move the needle toward ablation.”

Of note, an overwhelming majority of ILR patients received ablation, 93.5%, compared with 58.6% of standard-care patients. “It’s unclear how much of that association was caused by the ILR’s presence vs. other factors, such as physician availability, physician aggressiveness, or patient willingness for intervention,” Dr. Morin noted.