User login

The power of mentorship

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Commentary: CGRP medications, COVID-19, and menopause in patients with migraine, June 2023

The field of headache medicine has changed significantly since 2018 with the advent of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)–targeted medications. Although many patients improve after their first injection, and there is even a significant portion of "super responders" who can revert to nearly zero headache days per month, the majority of patients have a moderate response. Many patients who have not had a significant decrease in the frequency and severity of migraine attacks over 12 weeks wonder whether they will eventually achieve this on a CGRP medication. Barbanti and colleagues looked specifically at the subpopulation of late responders to CGRP treatments.

This was a multicenter, prospective study lasting 24 weeks, defining the differences in responders to CGRP treatments. Participants in this study had failed three or more prior preventive medications and had high-frequency, episodic, or chronic migraine. Their response rate was determined as follows: "responder" patients had a more than 50% reduction in baseline monthly migraine days between weeks 9 and 12, and "late responder" patients achieved that reduction after 12 weeks. All three injectable CGRP monoclonal antibodies were included in this trial.

Nearly 66% of patients treated with a CGRP monoclonal antibody had a 50% or greater response at 12 weeks. Of the study participants, 34% were considered nonresponders at 12 weeks, and 55% of those nonresponders did become responders between 13 and 24 weeks. This subpopulation of late responders was noted to have higher body mass index (BMI), more frequent prior treatment failures, as well as other pain and psychiatric comorbidities. Allodynia and unilateral cranial autonomic symptoms were also noted to be significantly higher in this population.

This study helps better determine the length of a CGRP trial for prevention. Patients with more treatment failures and comorbidities should be given additional time for this class of medications to work, even beyond the initial 12 weeks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way of life for everyone, and this is especially true for people with chronic medical conditions. Hrytsenko and colleagues sought to quantify the effect that COVID-19 had on patients with a history of episodic or chronic migraine. They used a scale to determine "psycho-emotional state deterioration" in patients with migraine with and without a history of COVID-19.

The investigators included 133 participants with a prior diagnosis of migraine, either chronic or episodic. Of these, 95 had a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for COVID-19, indicating SARS-CoV-2 infection; 38 did not. The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) was used to assess the severity of perceived anxiety symptoms and was used to determine psycho-emotional state. The Migraine Disability Assessment test (MIDAS) was used to determine their quality of life and degree of disability related to migraine. Patients with a history of COVID-19 had an increased usage of antimigraine medications, increased frequency of attacks, and higher HARS ratings. The average MIDAS score also increased significantly.

Many of our patients who were struggling prior to the COVID-19 pandemic unfortunately have done much worse after SARS-CoV-2 infection. A number of potential explanations exist for this, including worsening neuroinflammation in the context of COVID-19, which can specifically increase the propagation of inflammatory neurotransmitters, such as CGRP. Patients with a history of migraine respond to this with heightened frequency and severity of migraine.

There is a notable growing connection between certain neurologic conditions and vasomotor symptoms. Specifically, there appears to be an increased incidence of migraine and certain hypertensive or tachycardic conditions. Migraine is well known to be a vascular risk factor and migraine with aura even more so. Faubion and colleagues sought to quantify this in a specific menopausal population.

This was a large cross-sectional study, with an older median age compared with average migraine studies: 52.8 years. Nearly 60% of participants were postmenopausal and were recruited from a Mayo Clinic menopause registry. Participants were evaluated for a history of migraine based on The International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD3), criteria. They also had their symptoms measured on a menopause rating scale (the symptoms measured included hot flashes, sleep problems, physical and mental exhaustion, joint and muscular discomfort, and mood). Additional information was cross-referenced, including BMI, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, hypertension, and menopause status.

A diagnosis of migraine was associated with hypertension. There was no association between hypertension and hot flash severity, and there was a suggestion that hot flash severity and migraine history were not associated. The presence of other pain disorders also did not correlate with any other vasomotor symptoms.

This study does again link vasomotor issues with migraines. This connection remains well-founded and relevant. Antihypertensive medications have been some of the first preventive options ever offered to people with migraine. CGRP medications may actually lead to an increase in the risk for hypertension. Disconnection remains relevant and is something to discuss with patients with migraine, especially if they are at a higher risk.

The field of headache medicine has changed significantly since 2018 with the advent of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)–targeted medications. Although many patients improve after their first injection, and there is even a significant portion of "super responders" who can revert to nearly zero headache days per month, the majority of patients have a moderate response. Many patients who have not had a significant decrease in the frequency and severity of migraine attacks over 12 weeks wonder whether they will eventually achieve this on a CGRP medication. Barbanti and colleagues looked specifically at the subpopulation of late responders to CGRP treatments.

This was a multicenter, prospective study lasting 24 weeks, defining the differences in responders to CGRP treatments. Participants in this study had failed three or more prior preventive medications and had high-frequency, episodic, or chronic migraine. Their response rate was determined as follows: "responder" patients had a more than 50% reduction in baseline monthly migraine days between weeks 9 and 12, and "late responder" patients achieved that reduction after 12 weeks. All three injectable CGRP monoclonal antibodies were included in this trial.

Nearly 66% of patients treated with a CGRP monoclonal antibody had a 50% or greater response at 12 weeks. Of the study participants, 34% were considered nonresponders at 12 weeks, and 55% of those nonresponders did become responders between 13 and 24 weeks. This subpopulation of late responders was noted to have higher body mass index (BMI), more frequent prior treatment failures, as well as other pain and psychiatric comorbidities. Allodynia and unilateral cranial autonomic symptoms were also noted to be significantly higher in this population.

This study helps better determine the length of a CGRP trial for prevention. Patients with more treatment failures and comorbidities should be given additional time for this class of medications to work, even beyond the initial 12 weeks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way of life for everyone, and this is especially true for people with chronic medical conditions. Hrytsenko and colleagues sought to quantify the effect that COVID-19 had on patients with a history of episodic or chronic migraine. They used a scale to determine "psycho-emotional state deterioration" in patients with migraine with and without a history of COVID-19.

The investigators included 133 participants with a prior diagnosis of migraine, either chronic or episodic. Of these, 95 had a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for COVID-19, indicating SARS-CoV-2 infection; 38 did not. The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) was used to assess the severity of perceived anxiety symptoms and was used to determine psycho-emotional state. The Migraine Disability Assessment test (MIDAS) was used to determine their quality of life and degree of disability related to migraine. Patients with a history of COVID-19 had an increased usage of antimigraine medications, increased frequency of attacks, and higher HARS ratings. The average MIDAS score also increased significantly.

Many of our patients who were struggling prior to the COVID-19 pandemic unfortunately have done much worse after SARS-CoV-2 infection. A number of potential explanations exist for this, including worsening neuroinflammation in the context of COVID-19, which can specifically increase the propagation of inflammatory neurotransmitters, such as CGRP. Patients with a history of migraine respond to this with heightened frequency and severity of migraine.

There is a notable growing connection between certain neurologic conditions and vasomotor symptoms. Specifically, there appears to be an increased incidence of migraine and certain hypertensive or tachycardic conditions. Migraine is well known to be a vascular risk factor and migraine with aura even more so. Faubion and colleagues sought to quantify this in a specific menopausal population.

This was a large cross-sectional study, with an older median age compared with average migraine studies: 52.8 years. Nearly 60% of participants were postmenopausal and were recruited from a Mayo Clinic menopause registry. Participants were evaluated for a history of migraine based on The International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD3), criteria. They also had their symptoms measured on a menopause rating scale (the symptoms measured included hot flashes, sleep problems, physical and mental exhaustion, joint and muscular discomfort, and mood). Additional information was cross-referenced, including BMI, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, hypertension, and menopause status.

A diagnosis of migraine was associated with hypertension. There was no association between hypertension and hot flash severity, and there was a suggestion that hot flash severity and migraine history were not associated. The presence of other pain disorders also did not correlate with any other vasomotor symptoms.

This study does again link vasomotor issues with migraines. This connection remains well-founded and relevant. Antihypertensive medications have been some of the first preventive options ever offered to people with migraine. CGRP medications may actually lead to an increase in the risk for hypertension. Disconnection remains relevant and is something to discuss with patients with migraine, especially if they are at a higher risk.

The field of headache medicine has changed significantly since 2018 with the advent of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)–targeted medications. Although many patients improve after their first injection, and there is even a significant portion of "super responders" who can revert to nearly zero headache days per month, the majority of patients have a moderate response. Many patients who have not had a significant decrease in the frequency and severity of migraine attacks over 12 weeks wonder whether they will eventually achieve this on a CGRP medication. Barbanti and colleagues looked specifically at the subpopulation of late responders to CGRP treatments.

This was a multicenter, prospective study lasting 24 weeks, defining the differences in responders to CGRP treatments. Participants in this study had failed three or more prior preventive medications and had high-frequency, episodic, or chronic migraine. Their response rate was determined as follows: "responder" patients had a more than 50% reduction in baseline monthly migraine days between weeks 9 and 12, and "late responder" patients achieved that reduction after 12 weeks. All three injectable CGRP monoclonal antibodies were included in this trial.

Nearly 66% of patients treated with a CGRP monoclonal antibody had a 50% or greater response at 12 weeks. Of the study participants, 34% were considered nonresponders at 12 weeks, and 55% of those nonresponders did become responders between 13 and 24 weeks. This subpopulation of late responders was noted to have higher body mass index (BMI), more frequent prior treatment failures, as well as other pain and psychiatric comorbidities. Allodynia and unilateral cranial autonomic symptoms were also noted to be significantly higher in this population.

This study helps better determine the length of a CGRP trial for prevention. Patients with more treatment failures and comorbidities should be given additional time for this class of medications to work, even beyond the initial 12 weeks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way of life for everyone, and this is especially true for people with chronic medical conditions. Hrytsenko and colleagues sought to quantify the effect that COVID-19 had on patients with a history of episodic or chronic migraine. They used a scale to determine "psycho-emotional state deterioration" in patients with migraine with and without a history of COVID-19.

The investigators included 133 participants with a prior diagnosis of migraine, either chronic or episodic. Of these, 95 had a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for COVID-19, indicating SARS-CoV-2 infection; 38 did not. The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) was used to assess the severity of perceived anxiety symptoms and was used to determine psycho-emotional state. The Migraine Disability Assessment test (MIDAS) was used to determine their quality of life and degree of disability related to migraine. Patients with a history of COVID-19 had an increased usage of antimigraine medications, increased frequency of attacks, and higher HARS ratings. The average MIDAS score also increased significantly.

Many of our patients who were struggling prior to the COVID-19 pandemic unfortunately have done much worse after SARS-CoV-2 infection. A number of potential explanations exist for this, including worsening neuroinflammation in the context of COVID-19, which can specifically increase the propagation of inflammatory neurotransmitters, such as CGRP. Patients with a history of migraine respond to this with heightened frequency and severity of migraine.

There is a notable growing connection between certain neurologic conditions and vasomotor symptoms. Specifically, there appears to be an increased incidence of migraine and certain hypertensive or tachycardic conditions. Migraine is well known to be a vascular risk factor and migraine with aura even more so. Faubion and colleagues sought to quantify this in a specific menopausal population.

This was a large cross-sectional study, with an older median age compared with average migraine studies: 52.8 years. Nearly 60% of participants were postmenopausal and were recruited from a Mayo Clinic menopause registry. Participants were evaluated for a history of migraine based on The International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD3), criteria. They also had their symptoms measured on a menopause rating scale (the symptoms measured included hot flashes, sleep problems, physical and mental exhaustion, joint and muscular discomfort, and mood). Additional information was cross-referenced, including BMI, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, hypertension, and menopause status.

A diagnosis of migraine was associated with hypertension. There was no association between hypertension and hot flash severity, and there was a suggestion that hot flash severity and migraine history were not associated. The presence of other pain disorders also did not correlate with any other vasomotor symptoms.

This study does again link vasomotor issues with migraines. This connection remains well-founded and relevant. Antihypertensive medications have been some of the first preventive options ever offered to people with migraine. CGRP medications may actually lead to an increase in the risk for hypertension. Disconnection remains relevant and is something to discuss with patients with migraine, especially if they are at a higher risk.

Commentary: Evolving Treatment of CLL, June 2023

Novel therapies have transformed the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) over the past decade. With the advent of new options, the optimal therapy for newly diagnosed patients has become less clear. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have led to improvement in outcomes for most patients with CLL compared with chemoimmunotherapy (CIT).1,2 Second-generation BTK inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, are also available and appear to have an improved safety profile compared with ibrutinib. Similarly, the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor venetoclax, in combination with obinutuzumab, is an effective option in first-line treatment that offers a time-limited approach.3 Studies combining BTK and BCL2 inhibitors are also promising in this setting.

Recently, the phase 3 GAIA-CLL13 study aimed to address the question of optimal time-limited first-line treatment for fit patients with CLL. Of note, patients with TP53 aberrations were excluded. Patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms: CIT (fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab or bendamustine-rituximab), venetoclax-obinutuzumab, venetoclax-rituximab, or venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinub.

At 15 months, the rate of undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD) was higher in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab group (86.5%; 97.5% CI 80.6-91.1) and the venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib group (92.2%; 97.5% CI 87.3-95.7) compared with the CIT group (52.0%; 97.5% CI 44.4-59.5; P < .001 for both comparisons). The rate of uMRD for the venetoclax-rituximab group, however, was not higher than the rate in the CIT group (57.0%; 97.5%, CI 49.5-64.2; P = .32). The 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 90.5% in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib group and 75.5% in the CIT group (hazard ratio [HR] for disease progression or death 0.32; 97.5% CI 0.19-0.54; P < .001). PFS at 3 years was also higher in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab group (87.7%; HR for disease progression or death, 0.42; 97.5% CI 0.26-0.68; P < .001), but not with venetoclax-rituximab group (80.8%; HR 0.79; 97.5% CI 0.53-1.18; P = .18). Grade 3 and grade 4 infections were more common with CIT (18.5%) and venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib (21.2%) than with venetoclax-rituximab (10.5%) or venetoclax-obinutuzumab (13.2%).

This study confirms the role of fixed-duration venetoclax-based therapy for younger, fit patients with CLL. Interestingly, this study also suggests that rates of uMRD and PFS are superior with the use of obinutuzumab rather than with rituximab. Also of note, though the uMRD and PFS were highest with the triplet combination, it was not clearly superior to venetoclax-obinutuzumab alone and was associated with greater rates of toxicity.

Another ongoing randomized trial in first-line treatment of CLL is the FLAIR trial. This study was initially designed to compare ibrutinib-rituximab with standard CIT, though it was later modified to include an arm of ibrutinib alone and ibrutinib-venetoclax. Recently, the results of the first formal interim analysis comparing fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (n = 385) to ibrutinib-rituximb (n = 386), were published. This study, like the ECOG1912 study2, demonstrated improved outcomes with a BTK inhibitor over standard CIT in fit patients with CLL. After a median follow-up of 53 months, the median PFS was not reached in patients receiving ibrutinib-rituximab and was 67 months (95% CI 63 to not reached) in those receiving fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (HR 0.44; P < .0001). A substantial number of sudden cardiac or unexplained deaths occurred, which were more frequent in the ibrutinib-rituximab group.

Though questions regarding optimal treatment remain, there are now multiple studies to suggest an advantage of novel agents over traditional CIT. Furthermore, regardless of approach, outcomes appear favorable for patients with CLL, even among higher-risk patients.

Other studies are also evaluating alternative ways to sequence therapy. A recent phase 2 study, for example, evaluated venetoclax consolidation for patients on ibrutinib. Forty-five patients with CLL and detectable disease (≥ 0.01% minimal residual disease in bone marrow [BM]) after treatment with ibrutinib for 12 or more months who had one or more high-risk feature for disease progression were included. Patients received combined treatment with ibrutinib (previously tolerated dose) and venetoclax (escalated to 400 mg once daily) for 24 or less cycles. Venetoclax was continued until patients achieved uMRD. Patients with uMRD also had the option of discontinuing ibrutinib. Adding venetoclax to ibrutinib led to a cumulative BM uMRD rate of 73%. BM uMRD was achieved by 71% of patients after venetoclax therapy completion and by 38% and 57% of patients after 6 and 12 cycles, respectively. This trial highlights the potential use of MRD to guide treatment as well as consolidation strategies to allow for time-limited treatment.

Additional References

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2517-2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812836

- Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:432-443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817073

- Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2225-2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815281

Novel therapies have transformed the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) over the past decade. With the advent of new options, the optimal therapy for newly diagnosed patients has become less clear. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have led to improvement in outcomes for most patients with CLL compared with chemoimmunotherapy (CIT).1,2 Second-generation BTK inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, are also available and appear to have an improved safety profile compared with ibrutinib. Similarly, the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor venetoclax, in combination with obinutuzumab, is an effective option in first-line treatment that offers a time-limited approach.3 Studies combining BTK and BCL2 inhibitors are also promising in this setting.

Recently, the phase 3 GAIA-CLL13 study aimed to address the question of optimal time-limited first-line treatment for fit patients with CLL. Of note, patients with TP53 aberrations were excluded. Patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms: CIT (fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab or bendamustine-rituximab), venetoclax-obinutuzumab, venetoclax-rituximab, or venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinub.

At 15 months, the rate of undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD) was higher in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab group (86.5%; 97.5% CI 80.6-91.1) and the venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib group (92.2%; 97.5% CI 87.3-95.7) compared with the CIT group (52.0%; 97.5% CI 44.4-59.5; P < .001 for both comparisons). The rate of uMRD for the venetoclax-rituximab group, however, was not higher than the rate in the CIT group (57.0%; 97.5%, CI 49.5-64.2; P = .32). The 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 90.5% in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib group and 75.5% in the CIT group (hazard ratio [HR] for disease progression or death 0.32; 97.5% CI 0.19-0.54; P < .001). PFS at 3 years was also higher in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab group (87.7%; HR for disease progression or death, 0.42; 97.5% CI 0.26-0.68; P < .001), but not with venetoclax-rituximab group (80.8%; HR 0.79; 97.5% CI 0.53-1.18; P = .18). Grade 3 and grade 4 infections were more common with CIT (18.5%) and venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib (21.2%) than with venetoclax-rituximab (10.5%) or venetoclax-obinutuzumab (13.2%).

This study confirms the role of fixed-duration venetoclax-based therapy for younger, fit patients with CLL. Interestingly, this study also suggests that rates of uMRD and PFS are superior with the use of obinutuzumab rather than with rituximab. Also of note, though the uMRD and PFS were highest with the triplet combination, it was not clearly superior to venetoclax-obinutuzumab alone and was associated with greater rates of toxicity.

Another ongoing randomized trial in first-line treatment of CLL is the FLAIR trial. This study was initially designed to compare ibrutinib-rituximab with standard CIT, though it was later modified to include an arm of ibrutinib alone and ibrutinib-venetoclax. Recently, the results of the first formal interim analysis comparing fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (n = 385) to ibrutinib-rituximb (n = 386), were published. This study, like the ECOG1912 study2, demonstrated improved outcomes with a BTK inhibitor over standard CIT in fit patients with CLL. After a median follow-up of 53 months, the median PFS was not reached in patients receiving ibrutinib-rituximab and was 67 months (95% CI 63 to not reached) in those receiving fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (HR 0.44; P < .0001). A substantial number of sudden cardiac or unexplained deaths occurred, which were more frequent in the ibrutinib-rituximab group.

Though questions regarding optimal treatment remain, there are now multiple studies to suggest an advantage of novel agents over traditional CIT. Furthermore, regardless of approach, outcomes appear favorable for patients with CLL, even among higher-risk patients.

Other studies are also evaluating alternative ways to sequence therapy. A recent phase 2 study, for example, evaluated venetoclax consolidation for patients on ibrutinib. Forty-five patients with CLL and detectable disease (≥ 0.01% minimal residual disease in bone marrow [BM]) after treatment with ibrutinib for 12 or more months who had one or more high-risk feature for disease progression were included. Patients received combined treatment with ibrutinib (previously tolerated dose) and venetoclax (escalated to 400 mg once daily) for 24 or less cycles. Venetoclax was continued until patients achieved uMRD. Patients with uMRD also had the option of discontinuing ibrutinib. Adding venetoclax to ibrutinib led to a cumulative BM uMRD rate of 73%. BM uMRD was achieved by 71% of patients after venetoclax therapy completion and by 38% and 57% of patients after 6 and 12 cycles, respectively. This trial highlights the potential use of MRD to guide treatment as well as consolidation strategies to allow for time-limited treatment.

Additional References

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2517-2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812836

- Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:432-443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817073

- Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2225-2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815281

Novel therapies have transformed the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) over the past decade. With the advent of new options, the optimal therapy for newly diagnosed patients has become less clear. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors have led to improvement in outcomes for most patients with CLL compared with chemoimmunotherapy (CIT).1,2 Second-generation BTK inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, are also available and appear to have an improved safety profile compared with ibrutinib. Similarly, the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor venetoclax, in combination with obinutuzumab, is an effective option in first-line treatment that offers a time-limited approach.3 Studies combining BTK and BCL2 inhibitors are also promising in this setting.

Recently, the phase 3 GAIA-CLL13 study aimed to address the question of optimal time-limited first-line treatment for fit patients with CLL. Of note, patients with TP53 aberrations were excluded. Patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms: CIT (fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab or bendamustine-rituximab), venetoclax-obinutuzumab, venetoclax-rituximab, or venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinub.

At 15 months, the rate of undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD) was higher in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab group (86.5%; 97.5% CI 80.6-91.1) and the venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib group (92.2%; 97.5% CI 87.3-95.7) compared with the CIT group (52.0%; 97.5% CI 44.4-59.5; P < .001 for both comparisons). The rate of uMRD for the venetoclax-rituximab group, however, was not higher than the rate in the CIT group (57.0%; 97.5%, CI 49.5-64.2; P = .32). The 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 90.5% in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib group and 75.5% in the CIT group (hazard ratio [HR] for disease progression or death 0.32; 97.5% CI 0.19-0.54; P < .001). PFS at 3 years was also higher in the venetoclax-obinutuzumab group (87.7%; HR for disease progression or death, 0.42; 97.5% CI 0.26-0.68; P < .001), but not with venetoclax-rituximab group (80.8%; HR 0.79; 97.5% CI 0.53-1.18; P = .18). Grade 3 and grade 4 infections were more common with CIT (18.5%) and venetoclax-obinutuzumab-ibrutinib (21.2%) than with venetoclax-rituximab (10.5%) or venetoclax-obinutuzumab (13.2%).

This study confirms the role of fixed-duration venetoclax-based therapy for younger, fit patients with CLL. Interestingly, this study also suggests that rates of uMRD and PFS are superior with the use of obinutuzumab rather than with rituximab. Also of note, though the uMRD and PFS were highest with the triplet combination, it was not clearly superior to venetoclax-obinutuzumab alone and was associated with greater rates of toxicity.

Another ongoing randomized trial in first-line treatment of CLL is the FLAIR trial. This study was initially designed to compare ibrutinib-rituximab with standard CIT, though it was later modified to include an arm of ibrutinib alone and ibrutinib-venetoclax. Recently, the results of the first formal interim analysis comparing fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (n = 385) to ibrutinib-rituximb (n = 386), were published. This study, like the ECOG1912 study2, demonstrated improved outcomes with a BTK inhibitor over standard CIT in fit patients with CLL. After a median follow-up of 53 months, the median PFS was not reached in patients receiving ibrutinib-rituximab and was 67 months (95% CI 63 to not reached) in those receiving fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (HR 0.44; P < .0001). A substantial number of sudden cardiac or unexplained deaths occurred, which were more frequent in the ibrutinib-rituximab group.

Though questions regarding optimal treatment remain, there are now multiple studies to suggest an advantage of novel agents over traditional CIT. Furthermore, regardless of approach, outcomes appear favorable for patients with CLL, even among higher-risk patients.

Other studies are also evaluating alternative ways to sequence therapy. A recent phase 2 study, for example, evaluated venetoclax consolidation for patients on ibrutinib. Forty-five patients with CLL and detectable disease (≥ 0.01% minimal residual disease in bone marrow [BM]) after treatment with ibrutinib for 12 or more months who had one or more high-risk feature for disease progression were included. Patients received combined treatment with ibrutinib (previously tolerated dose) and venetoclax (escalated to 400 mg once daily) for 24 or less cycles. Venetoclax was continued until patients achieved uMRD. Patients with uMRD also had the option of discontinuing ibrutinib. Adding venetoclax to ibrutinib led to a cumulative BM uMRD rate of 73%. BM uMRD was achieved by 71% of patients after venetoclax therapy completion and by 38% and 57% of patients after 6 and 12 cycles, respectively. This trial highlights the potential use of MRD to guide treatment as well as consolidation strategies to allow for time-limited treatment.

Additional References

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2517-2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812836

- Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:432-443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817073

- Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2225-2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815281

Commentary: Ongoing therapy options in RA, June 2023

Several environmental risk factors are associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with smoking having one of the strongest associations. Exposure to airborne toxins has also been associated with development of anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Beidelschies and colleagues performed a cross-sectional analysis using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to examine a potential interaction between smoking and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) affecting the development of RA. Stored blood and urine samples of survey respondents were examined, and levels of PAH as well as other toxicants were measured. Of nearly 22,000 participants, about 1400 of whom reported a diagnosis of RA, toxicants were measured in about 7000. Higher levels of PAH and phthalate metabolites were more strongly associated with development of RA. Because cigarettes are a source of PAH, the authors postulated that PAH mediated the impact of smoking on development of RA, a plausible explanation given that smoking was not associated with RA after adjustment for PAH levels. However, given the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be determined.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been found in several surveillance studies to be associated with an increased risk for cancer and cardiovascular events. Westermann and colleagues performed an observational cohort study using Danish nationwide registries to evaluate cancer risk (other than nonmelanomatous skin cancer) in patients with RA treated with tofacitinib or baricitinib. Among 875 patients treated with JAK inhibitors vs 4247 patients treated with biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD), cancer incidence rates were similar (14.4 vs 12.9 per 1000 patient-years, respectively). Interestingly, though cancer incidence rates increased in patients > 50 and those > 65 years of age, the effect was similar between patients treated with JAK inhibitors and bDMARD. The largest difference was seen in patients up to 1 year vs > 1 year of follow-up, with hazard ratios of 1.54 vs 1.07. These findings are somewhat reassuring in light of results from the ORAL Surveillance study, suggesting increased cancer and cardiovascular risk among older patients with RA. However, as with bDMARD, increased scrutiny may be warranted among patients > 65 years, especially in the first year of treatment.

Finally, regarding withdrawal of therapy, Curtis and colleagues performed a randomized controlled study of patients with RA on combination therapy with methotrexate and etanercept and evaluated factors associated with maintenance of remission. In this study, withdrawal of methotrexate and etanercept were compared: About 250 patients whose disease was in remission, on the basis of the Simplified Disease Activity Index, were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive methotrexate monotherapy, etanercept monotherapy, or combination therapy. Prior analyses of these data have shown that continuing etanercept monotherapy showed a benefit in maintaining remission compared with continuing methotrexate monotherapy. Several baseline characteristics, including higher patient global activity at baseline and rheumatoid factor seropositivity, were associated with a lower likelihood of maintaining remission or low disease activity. Interestingly, higher serum magnesium levels seemed to negatively affect maintenance of remission, though the mechanism for this finding is not clear. In general, however, this study did not add more information to prior work in terms of shedding light on which patients may be able to stop therapy.

Several environmental risk factors are associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with smoking having one of the strongest associations. Exposure to airborne toxins has also been associated with development of anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Beidelschies and colleagues performed a cross-sectional analysis using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to examine a potential interaction between smoking and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) affecting the development of RA. Stored blood and urine samples of survey respondents were examined, and levels of PAH as well as other toxicants were measured. Of nearly 22,000 participants, about 1400 of whom reported a diagnosis of RA, toxicants were measured in about 7000. Higher levels of PAH and phthalate metabolites were more strongly associated with development of RA. Because cigarettes are a source of PAH, the authors postulated that PAH mediated the impact of smoking on development of RA, a plausible explanation given that smoking was not associated with RA after adjustment for PAH levels. However, given the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be determined.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been found in several surveillance studies to be associated with an increased risk for cancer and cardiovascular events. Westermann and colleagues performed an observational cohort study using Danish nationwide registries to evaluate cancer risk (other than nonmelanomatous skin cancer) in patients with RA treated with tofacitinib or baricitinib. Among 875 patients treated with JAK inhibitors vs 4247 patients treated with biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD), cancer incidence rates were similar (14.4 vs 12.9 per 1000 patient-years, respectively). Interestingly, though cancer incidence rates increased in patients > 50 and those > 65 years of age, the effect was similar between patients treated with JAK inhibitors and bDMARD. The largest difference was seen in patients up to 1 year vs > 1 year of follow-up, with hazard ratios of 1.54 vs 1.07. These findings are somewhat reassuring in light of results from the ORAL Surveillance study, suggesting increased cancer and cardiovascular risk among older patients with RA. However, as with bDMARD, increased scrutiny may be warranted among patients > 65 years, especially in the first year of treatment.

Finally, regarding withdrawal of therapy, Curtis and colleagues performed a randomized controlled study of patients with RA on combination therapy with methotrexate and etanercept and evaluated factors associated with maintenance of remission. In this study, withdrawal of methotrexate and etanercept were compared: About 250 patients whose disease was in remission, on the basis of the Simplified Disease Activity Index, were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive methotrexate monotherapy, etanercept monotherapy, or combination therapy. Prior analyses of these data have shown that continuing etanercept monotherapy showed a benefit in maintaining remission compared with continuing methotrexate monotherapy. Several baseline characteristics, including higher patient global activity at baseline and rheumatoid factor seropositivity, were associated with a lower likelihood of maintaining remission or low disease activity. Interestingly, higher serum magnesium levels seemed to negatively affect maintenance of remission, though the mechanism for this finding is not clear. In general, however, this study did not add more information to prior work in terms of shedding light on which patients may be able to stop therapy.

Several environmental risk factors are associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with smoking having one of the strongest associations. Exposure to airborne toxins has also been associated with development of anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Beidelschies and colleagues performed a cross-sectional analysis using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to examine a potential interaction between smoking and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) affecting the development of RA. Stored blood and urine samples of survey respondents were examined, and levels of PAH as well as other toxicants were measured. Of nearly 22,000 participants, about 1400 of whom reported a diagnosis of RA, toxicants were measured in about 7000. Higher levels of PAH and phthalate metabolites were more strongly associated with development of RA. Because cigarettes are a source of PAH, the authors postulated that PAH mediated the impact of smoking on development of RA, a plausible explanation given that smoking was not associated with RA after adjustment for PAH levels. However, given the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be determined.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been found in several surveillance studies to be associated with an increased risk for cancer and cardiovascular events. Westermann and colleagues performed an observational cohort study using Danish nationwide registries to evaluate cancer risk (other than nonmelanomatous skin cancer) in patients with RA treated with tofacitinib or baricitinib. Among 875 patients treated with JAK inhibitors vs 4247 patients treated with biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD), cancer incidence rates were similar (14.4 vs 12.9 per 1000 patient-years, respectively). Interestingly, though cancer incidence rates increased in patients > 50 and those > 65 years of age, the effect was similar between patients treated with JAK inhibitors and bDMARD. The largest difference was seen in patients up to 1 year vs > 1 year of follow-up, with hazard ratios of 1.54 vs 1.07. These findings are somewhat reassuring in light of results from the ORAL Surveillance study, suggesting increased cancer and cardiovascular risk among older patients with RA. However, as with bDMARD, increased scrutiny may be warranted among patients > 65 years, especially in the first year of treatment.

Finally, regarding withdrawal of therapy, Curtis and colleagues performed a randomized controlled study of patients with RA on combination therapy with methotrexate and etanercept and evaluated factors associated with maintenance of remission. In this study, withdrawal of methotrexate and etanercept were compared: About 250 patients whose disease was in remission, on the basis of the Simplified Disease Activity Index, were randomized in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive methotrexate monotherapy, etanercept monotherapy, or combination therapy. Prior analyses of these data have shown that continuing etanercept monotherapy showed a benefit in maintaining remission compared with continuing methotrexate monotherapy. Several baseline characteristics, including higher patient global activity at baseline and rheumatoid factor seropositivity, were associated with a lower likelihood of maintaining remission or low disease activity. Interestingly, higher serum magnesium levels seemed to negatively affect maintenance of remission, though the mechanism for this finding is not clear. In general, however, this study did not add more information to prior work in terms of shedding light on which patients may be able to stop therapy.

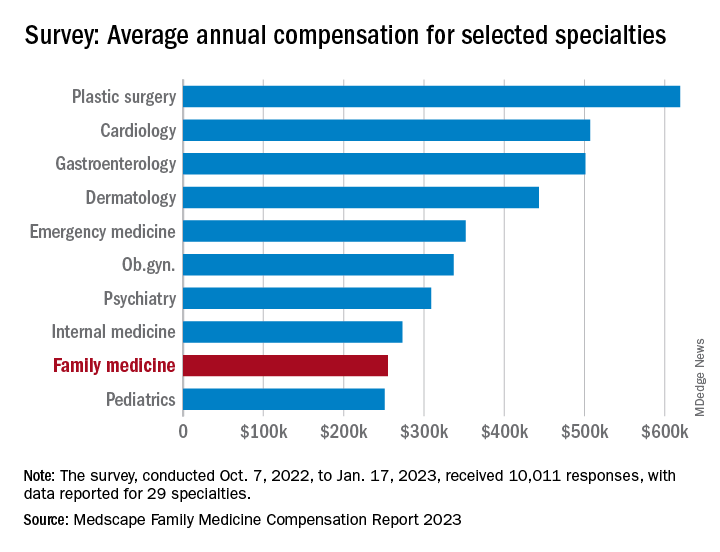

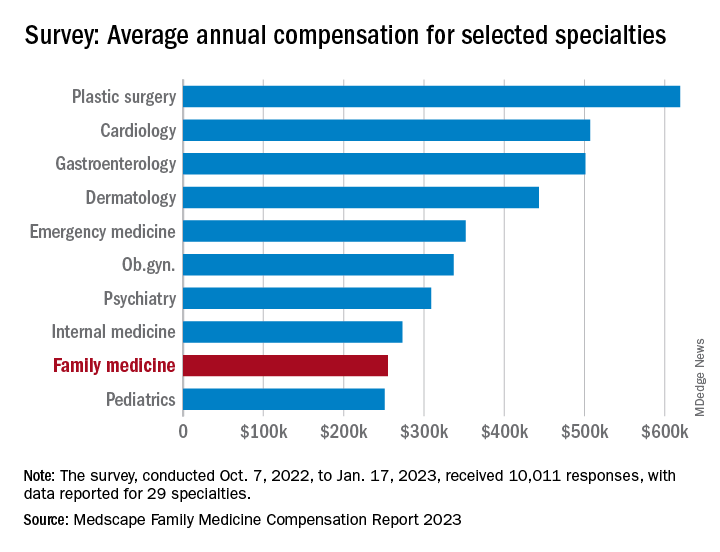

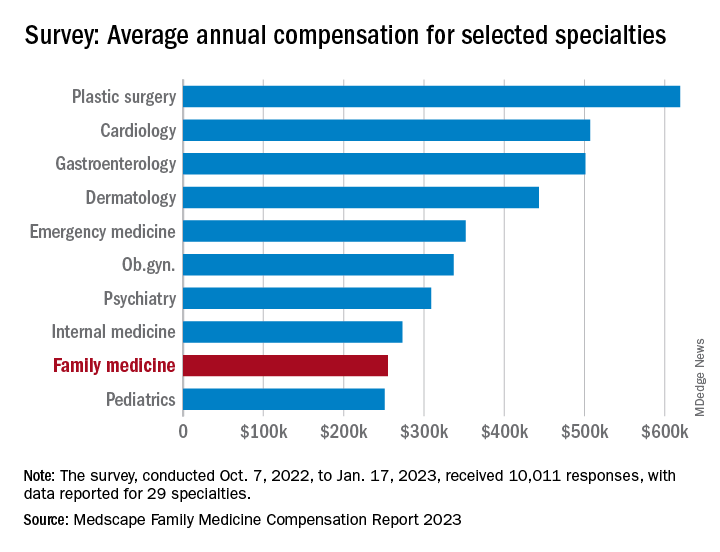

Survey: Family medicine earnings steady despite overall growth for physicians

according to the results of the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Average compensation for the specialty, which has risen by 31% since 2015, was stagnant in 2022, showing no growth from the previous year. COVID, at least, had less of an effect on earnings, as 48% of family physicians cited pandemic-related income losses, compared with 64% in 2021, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

Comments from those respondents covered several areas that were already concerning physicians before the pandemic. One wrote that “decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

Overall physician compensation in 2022 was up by about 4% from 2021. For the 12% of the 10,011 respondents who practice family medicine, the average held at $255,000, where it had been the year before. Among the other primary care specialists, internists’ earnings were up by almost 4% and pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, while ob.gyns. joined family physicians in the no-growth club, the Medscape results show.

For all physicians, average compensation in 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The lack of increase in FPs earnings among internists also included a decline of note: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 26% in 2021 to 23% in 2022. The 2022 disparity was only 16% for internists, however, even though family medicine has a considerably larger share of women (49% vs. 40%) among those surveyed, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, on the other hand, was higher among the family physicians (50%), compared with internists (43%). In 2022, 55% of family physicians said that they had been fairly paid.

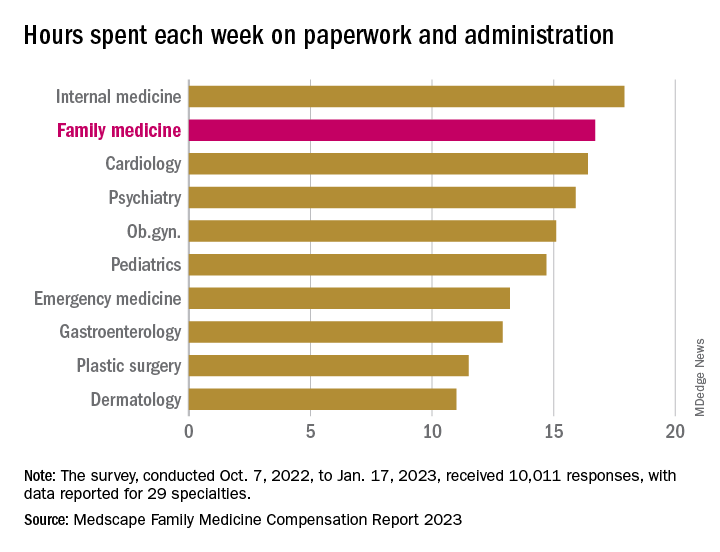

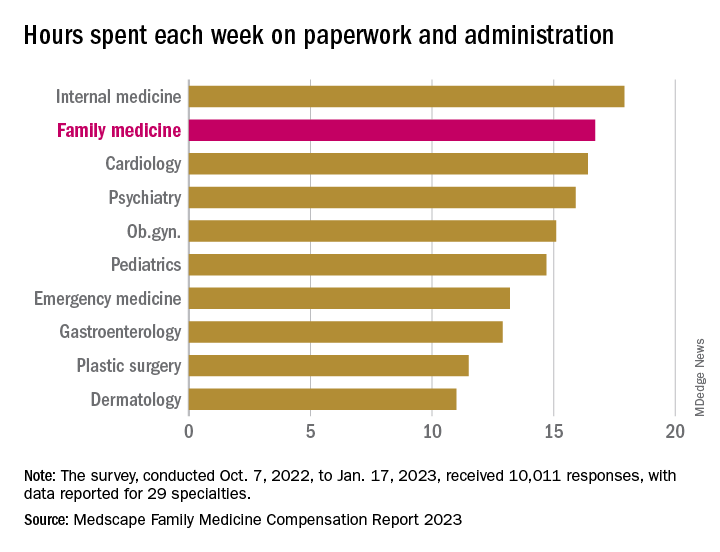

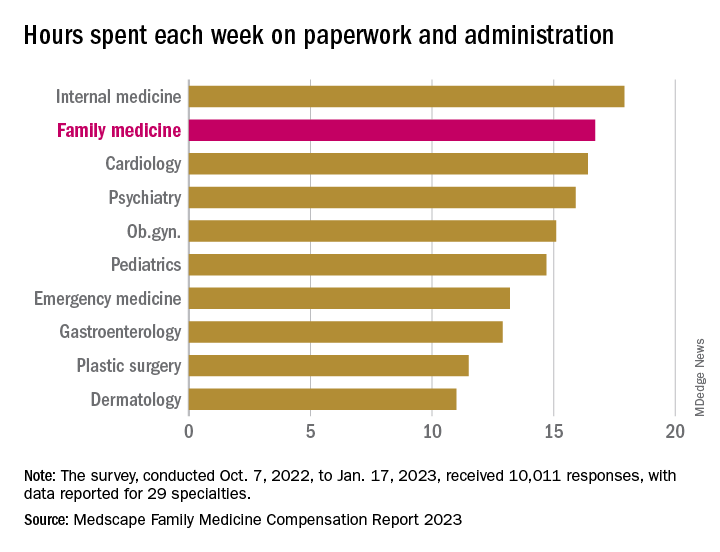

In 2022, FP respondents reported spending an average of 16.7 hours (up from 15.6 hours in 2021) each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) but well above anesthesiology, lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of family physician respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed that 66% of FPs would choose it again, putting them 28th of the 29 included specialties in their eagerness to follow the same path, above only the internists (61%), Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

according to the results of the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Average compensation for the specialty, which has risen by 31% since 2015, was stagnant in 2022, showing no growth from the previous year. COVID, at least, had less of an effect on earnings, as 48% of family physicians cited pandemic-related income losses, compared with 64% in 2021, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

Comments from those respondents covered several areas that were already concerning physicians before the pandemic. One wrote that “decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

Overall physician compensation in 2022 was up by about 4% from 2021. For the 12% of the 10,011 respondents who practice family medicine, the average held at $255,000, where it had been the year before. Among the other primary care specialists, internists’ earnings were up by almost 4% and pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, while ob.gyns. joined family physicians in the no-growth club, the Medscape results show.

For all physicians, average compensation in 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The lack of increase in FPs earnings among internists also included a decline of note: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 26% in 2021 to 23% in 2022. The 2022 disparity was only 16% for internists, however, even though family medicine has a considerably larger share of women (49% vs. 40%) among those surveyed, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, on the other hand, was higher among the family physicians (50%), compared with internists (43%). In 2022, 55% of family physicians said that they had been fairly paid.

In 2022, FP respondents reported spending an average of 16.7 hours (up from 15.6 hours in 2021) each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) but well above anesthesiology, lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of family physician respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed that 66% of FPs would choose it again, putting them 28th of the 29 included specialties in their eagerness to follow the same path, above only the internists (61%), Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

according to the results of the Medscape Family Physician Compensation Report 2023.

Average compensation for the specialty, which has risen by 31% since 2015, was stagnant in 2022, showing no growth from the previous year. COVID, at least, had less of an effect on earnings, as 48% of family physicians cited pandemic-related income losses, compared with 64% in 2021, according to those who responded to Medscape’s annual survey, which was conducted from Oct. 2, 2022, to Jan. 17, 2023.

Comments from those respondents covered several areas that were already concerning physicians before the pandemic. One wrote that “decreasing Medicare reimbursement and poor payor mix destroy our income,” and another said that “patients have become rude and come with poor information from social media.” One respondent described the situation this way: “Overwhelming burnout. I had to reduce my hours to keep myself from quitting medicine completely.”

Overall physician compensation in 2022 was up by about 4% from 2021. For the 12% of the 10,011 respondents who practice family medicine, the average held at $255,000, where it had been the year before. Among the other primary care specialists, internists’ earnings were up by almost 4% and pediatricians did almost as well with a 3% increase, while ob.gyns. joined family physicians in the no-growth club, the Medscape results show.

For all physicians, average compensation in 2022 was $352,000, an increase of almost 18% since 2018. “Supply and demand is the biggest driver,” Mike Belkin, JD, of physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, said in an interview. “Organizations understand it’s not getting any easier to get good candidates, and so for the most part, physicians are getting good offers.”

The lack of increase in FPs earnings among internists also included a decline of note: The disparity between mens’ and womens’ compensation dropped from 26% in 2021 to 23% in 2022. The 2022 disparity was only 16% for internists, however, even though family medicine has a considerably larger share of women (49% vs. 40%) among those surveyed, Medscape said.

Satisfaction with their compensation, on the other hand, was higher among the family physicians (50%), compared with internists (43%). In 2022, 55% of family physicians said that they had been fairly paid.

In 2022, FP respondents reported spending an average of 16.7 hours (up from 15.6 hours in 2021) each week on paperwork and administration, just below the survey leaders, physical medicine and rehabilitation (18.5 hours) and nephrology (18.1 hours) but well above anesthesiology, lowest of the 29 specialties at 9.0 hours, and the 2022 average of 15.5 hours for all physicians, Medscape said.

When asked if they would choose medicine again, 72% of family physician respondents and 73% of all physicians said yes, with emergency medicine (65%) and dermatology (86%) representing the two extremes. A question about specialty choice showed that 66% of FPs would choose it again, putting them 28th of the 29 included specialties in their eagerness to follow the same path, above only the internists (61%), Medscape reported.

Commenters among the survey respondents were not identified by specialty, but dissatisfaction on many fronts was a definite theme:

- “Our costs go up, and our reimbursement does not.”

- “Our practice was acquired by venture capital firms; they slashed costs.”

- “My productivity bonus should have come to $45,000. Instead I was paid only $15,000. Yet cardiologists and administrators who were working from home part of the year received their full bonus.”

- “I will no longer practice cookbook mediocrity.”

Blood cancer patient takes on bias and ‘gaslighting’

Diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2021, Ms. Ngon underwent port surgery to allow chemotherapy to be administered. Her right arm lost circulation and went numb, so she sought guidance from her blood cancer specialist. He dismissed her worries, saying that her tumors were pinching a nerve. She’d get better, he predicted, after more chemo.

“I knew in my body that something was wrong,” Ms. Ngon recalled. When the oncologist continued to downplay her concerns, she and a fellow communications specialist sat down together in the hospital lobby to draft an email to her physician. “We were trying to articulate the urgency in an email that expresses that I’m not being dramatic. We had to do it in a way that didn’t insult his intelligence: ‘Respectfully, you’re the doctor, but I know something is wrong.’ ”

In essence, Ms. Ngon was trying to be diplomatic and not trigger her oncologist’s defenses, while still convincing him to take action. Her approach to getting her doctor’s attention worked. He referred Ms. Ngon to a radiologist, who discovered that she had blood clots in her arm. Ms. Ngon then landed in the ICU for a week, as clinicians tried to break up the clots.

“I was the perfect person for this to happen to, because of my job and education. But it makes me sad because I understand I was in a fortunate position, with a background in communication. Most people don’t have that,” Ms. Ngon said.

This and other negative experiences during her medical saga inspired Ms. Ngon to partner with the Lymphoma Research Foundation in order to spread the word about unique challenges facing patients like her: people of color.

Ms. Ngon, who is Black, said her goal as a patient advocate is to “empower communities of color to speak up for themselves and hold oncologists responsible for listening and understanding differences across cultures.” And she wants to take a stand against the “gaslighting” of patients.

African Americans with hematologic disease like Ms. Ngon face a higher risk of poor outcomes than Whites, even as they are less likely than Whites to develop certain blood cancers. The reasons for this disparity aren’t clear, but researchers suspect they’re related to factors such as poverty, lack of insurance, genetics, and limited access to high-quality care.

Some researchers have blamed another factor: racism. A 2022 study sought to explain why Black and Hispanic patients with acute myeloid leukemia in urban areas have higher mortality rates than Whites, “despite more favorable genetics and younger age” (hazard ratio, 1.59, 95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.22 and HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.88-1.79). The study authors determined that “structural racism” – which they measured by examining segregation and “disadvantage” in neighborhoods where patients lived – accounted for nearly all of the disparities.

Ms. Ngon said her experiences and her awareness about poorer outcomes in medicine for African Americans – such as higher death rates for Black women during pregnancy – affect how she interacts with clinicians. “I automatically assume a barrier between me and my doctors, and it’s their responsibility to dismantle it.”

Making an connection with a physician can make a huge difference, she said. “I walked into my primary care doctor’s office and saw that she was a Latino woman. My guard went down, and I could feel her care for me as a human being. Whether that was because she was also a woman of color or not, I don’t know. But I did feel more cared for.”

However, Ms. Ngon could not find a Black oncologist to care for her in New York City, and that’s no surprise.

Ethnic and gender diversity remains an immense challenge in the hematology/oncology field. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, only about a third of oncologists are women, and the percentages identifying themselves as Black/African American and Hispanic are just 2.3% and 5.8%, respectively.

These numbers don’t seem likely to budge much any time soon. An analysis of medical students in U.S. oncology training programs from 2015-2020 found that just 3.8% identified themselves as Black/African American and 5.1% as Hispanic/Latino versus 52.15% as White and 31% as Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian.

Ms. Ngon encountered challenges on other fronts during her cancer care. When she needed a wig during chemotherapy, a list of insurer-approved shops didn’t include any that catered to African Americans. Essentially, she said, she was being told that she couldn’t “purchase a wig from a place that makes you feel comfortable and from a woman who understand your needs as a Black woman. It needs to be from these specific shops that really don’t cater to my community.”

She also found it difficult to find fellow patients who shared her unique challenges. “I remember when I was diagnosed, I was looking through the support groups on Facebook, trying to find someone Black to ask about whether braiding my hair might stop it from falling out.”

Now, Ms. Ngon is in remission. And she’s happy with her oncologist, who’s White. “He listened to me, and he promised me that I would have the most boring recovery process ever, after everything I’d experienced. That explains a lot of why I felt so comfortable with him.”

She hopes to use her partnership with the Lymphoma Research Foundation to be a resource for people of color and alert them to the support that’s available for them. “I would love to let them know how to advocate for themselves as patients, how to trust their bodies, how to push back if they feel like they’re not getting the care that they deserve.”

Ms. Ngon would also like to see more support for medical students of color. “I hope to exist in a world one day where it wouldn’t be so hard to find an oncologist who looks like me in a city as large as this one,” she said.

As for oncologists, she urged them to “go the extra mile and really, really listen to what patients are saying. It’s easier said than done because there are natural biases in this world, and it’s hard to overcome those obstacles. But to not be heard and have to push every time. It was just exhausting to do that on top of trying to beat cancer.”

Diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2021, Ms. Ngon underwent port surgery to allow chemotherapy to be administered. Her right arm lost circulation and went numb, so she sought guidance from her blood cancer specialist. He dismissed her worries, saying that her tumors were pinching a nerve. She’d get better, he predicted, after more chemo.

“I knew in my body that something was wrong,” Ms. Ngon recalled. When the oncologist continued to downplay her concerns, she and a fellow communications specialist sat down together in the hospital lobby to draft an email to her physician. “We were trying to articulate the urgency in an email that expresses that I’m not being dramatic. We had to do it in a way that didn’t insult his intelligence: ‘Respectfully, you’re the doctor, but I know something is wrong.’ ”

In essence, Ms. Ngon was trying to be diplomatic and not trigger her oncologist’s defenses, while still convincing him to take action. Her approach to getting her doctor’s attention worked. He referred Ms. Ngon to a radiologist, who discovered that she had blood clots in her arm. Ms. Ngon then landed in the ICU for a week, as clinicians tried to break up the clots.

“I was the perfect person for this to happen to, because of my job and education. But it makes me sad because I understand I was in a fortunate position, with a background in communication. Most people don’t have that,” Ms. Ngon said.

This and other negative experiences during her medical saga inspired Ms. Ngon to partner with the Lymphoma Research Foundation in order to spread the word about unique challenges facing patients like her: people of color.

Ms. Ngon, who is Black, said her goal as a patient advocate is to “empower communities of color to speak up for themselves and hold oncologists responsible for listening and understanding differences across cultures.” And she wants to take a stand against the “gaslighting” of patients.

African Americans with hematologic disease like Ms. Ngon face a higher risk of poor outcomes than Whites, even as they are less likely than Whites to develop certain blood cancers. The reasons for this disparity aren’t clear, but researchers suspect they’re related to factors such as poverty, lack of insurance, genetics, and limited access to high-quality care.

Some researchers have blamed another factor: racism. A 2022 study sought to explain why Black and Hispanic patients with acute myeloid leukemia in urban areas have higher mortality rates than Whites, “despite more favorable genetics and younger age” (hazard ratio, 1.59, 95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.22 and HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.88-1.79). The study authors determined that “structural racism” – which they measured by examining segregation and “disadvantage” in neighborhoods where patients lived – accounted for nearly all of the disparities.

Ms. Ngon said her experiences and her awareness about poorer outcomes in medicine for African Americans – such as higher death rates for Black women during pregnancy – affect how she interacts with clinicians. “I automatically assume a barrier between me and my doctors, and it’s their responsibility to dismantle it.”

Making an connection with a physician can make a huge difference, she said. “I walked into my primary care doctor’s office and saw that she was a Latino woman. My guard went down, and I could feel her care for me as a human being. Whether that was because she was also a woman of color or not, I don’t know. But I did feel more cared for.”

However, Ms. Ngon could not find a Black oncologist to care for her in New York City, and that’s no surprise.

Ethnic and gender diversity remains an immense challenge in the hematology/oncology field. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, only about a third of oncologists are women, and the percentages identifying themselves as Black/African American and Hispanic are just 2.3% and 5.8%, respectively.

These numbers don’t seem likely to budge much any time soon. An analysis of medical students in U.S. oncology training programs from 2015-2020 found that just 3.8% identified themselves as Black/African American and 5.1% as Hispanic/Latino versus 52.15% as White and 31% as Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian.

Ms. Ngon encountered challenges on other fronts during her cancer care. When she needed a wig during chemotherapy, a list of insurer-approved shops didn’t include any that catered to African Americans. Essentially, she said, she was being told that she couldn’t “purchase a wig from a place that makes you feel comfortable and from a woman who understand your needs as a Black woman. It needs to be from these specific shops that really don’t cater to my community.”

She also found it difficult to find fellow patients who shared her unique challenges. “I remember when I was diagnosed, I was looking through the support groups on Facebook, trying to find someone Black to ask about whether braiding my hair might stop it from falling out.”

Now, Ms. Ngon is in remission. And she’s happy with her oncologist, who’s White. “He listened to me, and he promised me that I would have the most boring recovery process ever, after everything I’d experienced. That explains a lot of why I felt so comfortable with him.”

She hopes to use her partnership with the Lymphoma Research Foundation to be a resource for people of color and alert them to the support that’s available for them. “I would love to let them know how to advocate for themselves as patients, how to trust their bodies, how to push back if they feel like they’re not getting the care that they deserve.”

Ms. Ngon would also like to see more support for medical students of color. “I hope to exist in a world one day where it wouldn’t be so hard to find an oncologist who looks like me in a city as large as this one,” she said.

As for oncologists, she urged them to “go the extra mile and really, really listen to what patients are saying. It’s easier said than done because there are natural biases in this world, and it’s hard to overcome those obstacles. But to not be heard and have to push every time. It was just exhausting to do that on top of trying to beat cancer.”

Diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma in 2021, Ms. Ngon underwent port surgery to allow chemotherapy to be administered. Her right arm lost circulation and went numb, so she sought guidance from her blood cancer specialist. He dismissed her worries, saying that her tumors were pinching a nerve. She’d get better, he predicted, after more chemo.

“I knew in my body that something was wrong,” Ms. Ngon recalled. When the oncologist continued to downplay her concerns, she and a fellow communications specialist sat down together in the hospital lobby to draft an email to her physician. “We were trying to articulate the urgency in an email that expresses that I’m not being dramatic. We had to do it in a way that didn’t insult his intelligence: ‘Respectfully, you’re the doctor, but I know something is wrong.’ ”

In essence, Ms. Ngon was trying to be diplomatic and not trigger her oncologist’s defenses, while still convincing him to take action. Her approach to getting her doctor’s attention worked. He referred Ms. Ngon to a radiologist, who discovered that she had blood clots in her arm. Ms. Ngon then landed in the ICU for a week, as clinicians tried to break up the clots.

“I was the perfect person for this to happen to, because of my job and education. But it makes me sad because I understand I was in a fortunate position, with a background in communication. Most people don’t have that,” Ms. Ngon said.

This and other negative experiences during her medical saga inspired Ms. Ngon to partner with the Lymphoma Research Foundation in order to spread the word about unique challenges facing patients like her: people of color.

Ms. Ngon, who is Black, said her goal as a patient advocate is to “empower communities of color to speak up for themselves and hold oncologists responsible for listening and understanding differences across cultures.” And she wants to take a stand against the “gaslighting” of patients.

African Americans with hematologic disease like Ms. Ngon face a higher risk of poor outcomes than Whites, even as they are less likely than Whites to develop certain blood cancers. The reasons for this disparity aren’t clear, but researchers suspect they’re related to factors such as poverty, lack of insurance, genetics, and limited access to high-quality care.

Some researchers have blamed another factor: racism. A 2022 study sought to explain why Black and Hispanic patients with acute myeloid leukemia in urban areas have higher mortality rates than Whites, “despite more favorable genetics and younger age” (hazard ratio, 1.59, 95% confidence interval, 1.15-2.22 and HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.88-1.79). The study authors determined that “structural racism” – which they measured by examining segregation and “disadvantage” in neighborhoods where patients lived – accounted for nearly all of the disparities.

Ms. Ngon said her experiences and her awareness about poorer outcomes in medicine for African Americans – such as higher death rates for Black women during pregnancy – affect how she interacts with clinicians. “I automatically assume a barrier between me and my doctors, and it’s their responsibility to dismantle it.”

Making an connection with a physician can make a huge difference, she said. “I walked into my primary care doctor’s office and saw that she was a Latino woman. My guard went down, and I could feel her care for me as a human being. Whether that was because she was also a woman of color or not, I don’t know. But I did feel more cared for.”

However, Ms. Ngon could not find a Black oncologist to care for her in New York City, and that’s no surprise.