User login

Is the contemporary mental health crisis among youth due to DMN disruption?

The advent of unprecedented technologies drastically altering the behavior of children and adolescents, compounded by prolonged isolation from a once-in-a-century pandemic, may have negatively impacted the normal connectivity of the human brain among youth, leading to the current alarming increase of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among this population.

The human brain is comprised of multiple large-scale networks that are functionally connected and control feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. As clinical neuroscientists, psychiatrists must consider the profound impact of a massive societal shift in human behavior on the functional connectivity of brain networks in health and disease. The advent of smartphones, social media, and video game addiction may have disrupted the developing brain networks in children and adolescents, leading to the current escalating epidemic of mental disorders in youth.

The major networks in the human brain include the default mode network (DMN), the salience network, the limbic system, the dorsal attention network, the central executive network, and the visual system.1 Each network connects several brain regions. Researchers can use functional MRI to detect the connectivity of those networks. When blood flow increases concurrently across 2 or 3 networks, this indicates those networks are functionally connected.

There was an old “dogma” that brain regions use energy only when activated and being used. Hans Berger, who developed the EEG in 1929, noticed electrical activity at rest and proposed that the brain is constantly busy, but his neurology peers did not take him seriously.2 In the 1950s, Louis Sokoloff noticed that brain metabolism was the same whether a person is at rest or doing math. In the 1970s, David Ingvar discovered that the highest blood flow in the frontal lobe occurred when a person was at rest.3 Finally, in 2007, Raichle et al4 used positron emission tomography scans to confirm that the frontal lobe is most active when a person is not doing anything. He labeled this phenomenon the DMN, comprising the medial fronto-parietal cortex, the posterior cingulate gyrus, the precuneus, and the angular gyrus. Interestingly, the number of publications about the DMN has skyrocketed since 2007.

The many roles of the DMN

Ongoing research has revealed that the DMN is most active at rest, and its anatomical hubs mediate several key functions5:

- Posterior cingulate gyrus (the central core of the DMN): remembering the past and thinking about the future

- Medial prefrontal cortex: autobiographical memories, future goals and events, reflecting on one’s emotional self, and considering decisions about family members

- Dorsal medial subsystem: thinking about others, determining and inferring the purpose of other people’s actions

- Temporo-parietal junction: reflecting on the beliefs and emotions of others (known as “theory of mind”6)

- Lateral parietal junction: retrieval of social and conceptual knowledge

- Hippocampus: forming new memories, remembering the past, imagining the future

- Posterior-inferior parietal lobe: junction of auditory, visual, and somatic sensory information and attention

- Precuneus: Visual, sensory-motor, and attention.

Many terms have been used to describe the function of the DMN, including “daydreaming,” “auto-pilot,” “mind-wondering,” “reminiscing,” “contemplating,” “self-reflection,” “the neurological basis of the self,” and “seat of literary creativity.”

Psychiatric consequences of DMN deactivation

When another brain network, the attention network (which is also referred to as the task-positive network), is activated consciously and volitionally to perform a task that demands focus (such as text messaging, playing video games, or continuously interacting with social media sites), DMN activity declines.

Continue to: The DMN does not exist...

The DMN does not exist in infants, but starts to develop in childhood.7 It is enhanced by exercise, daydreaming, and sleep, activities that are common in childhood but have declined drastically with the widespread use of smartphones, video games, and social media, which for many youth occupy the bulk of their waking hours. Those tasks, which require continuous attention, deactivate the DMN. In fact, research has shown that addictive behavior decreases the connectivity of the DMN and suppresses its activity.8 Most children and adolescents can be regarded as essentially addicted to social media, text messaging, and video games. Unsurprisingly, serious psychiatric consequences follow.9

DMN dysfunction has been reported in several psychiatric conditions, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, autism, schizophrenia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance use.10-12 Impaired social interactions and communications, negative ruminations, suicidal ideas, and impaired encoding of long-term memories are some of the adverse effects of DMN dysfunction. The good news is that the DMN’s connectivity and functioning can be modulated and restored by meditation, mentalizing, exercise, psychotherapy, antidepressants, and psychedelics.13,14

The lockdown and stress of the COVID-19 pandemic added insult to injury and exacerbated mental illness in children by isolating them from each other and intensifying their technological addiction to fill the void of isolation. This crisis in youth mental health continues unabated, and calls for action to prevent grim outcomes. DMN dysfunction in youth can be reversed with treatment, but access to mental health care has become more challenging due to workforce shortages and insurance restrictions. Psychiatrists and parents must work diligently to treat psychiatrically affected youth, which has become a DaMN serious problem…

1. Yao Z, Hu B, Xie Y, et al. A review of structural and functional brain networks: small world and atlas. Brain Inform. 2015;2(1):45-52. doi:10.1007/s40708-015-0009-z

2. Raichle ME. The brain’s dark energy. Sci Am. 2010;302(3):44-49. doi:10.1038/scientific american0310-44

3. Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1-38. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011

4. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37(4):1083-1090; discussion 1097-1099. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041

5. Andrews-Hanna JR. The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(3):251-270. doi:10.1177/1073858411403316

6. Tsoukalas I. Theory of mind: towards an evolutionary theory. Evolutionary Psychological Science. 2018;4(1):38-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0112-x

7. Broyd SJ, Demanuele C, Debener S, et al. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(3):279-296. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002

8. Zhang R, Volkow ND. Brain default-mode network dysfunction in addiction. Neuroimage. 2019;200:313-331. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.036

9. Bommersbach TJ, McKean AJ, Olfson M, et al. National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among youth, 2011-2020. JAMA. 2023;329(17):1469-1477. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.4809

10. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ford JM. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:49-76. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143049

11. Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Wrocklage KM, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: a novel network-restricted topology approach. Neuroimage. 2018;176:489-498. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.005

12. Nagata JM, Chu J, Zamora G, et al. Screen time and obsessive-compulsive disorder among children 9-10 years old: a prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(3):390-396. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.10.023

13. Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, et al. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:48-73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016

14. Gattuso JJ, Perkins D, Ruffell S, et al. Default mode network modulation by psychedelics: a systematic review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26(3):155-188. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyac074

The advent of unprecedented technologies drastically altering the behavior of children and adolescents, compounded by prolonged isolation from a once-in-a-century pandemic, may have negatively impacted the normal connectivity of the human brain among youth, leading to the current alarming increase of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among this population.

The human brain is comprised of multiple large-scale networks that are functionally connected and control feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. As clinical neuroscientists, psychiatrists must consider the profound impact of a massive societal shift in human behavior on the functional connectivity of brain networks in health and disease. The advent of smartphones, social media, and video game addiction may have disrupted the developing brain networks in children and adolescents, leading to the current escalating epidemic of mental disorders in youth.

The major networks in the human brain include the default mode network (DMN), the salience network, the limbic system, the dorsal attention network, the central executive network, and the visual system.1 Each network connects several brain regions. Researchers can use functional MRI to detect the connectivity of those networks. When blood flow increases concurrently across 2 or 3 networks, this indicates those networks are functionally connected.

There was an old “dogma” that brain regions use energy only when activated and being used. Hans Berger, who developed the EEG in 1929, noticed electrical activity at rest and proposed that the brain is constantly busy, but his neurology peers did not take him seriously.2 In the 1950s, Louis Sokoloff noticed that brain metabolism was the same whether a person is at rest or doing math. In the 1970s, David Ingvar discovered that the highest blood flow in the frontal lobe occurred when a person was at rest.3 Finally, in 2007, Raichle et al4 used positron emission tomography scans to confirm that the frontal lobe is most active when a person is not doing anything. He labeled this phenomenon the DMN, comprising the medial fronto-parietal cortex, the posterior cingulate gyrus, the precuneus, and the angular gyrus. Interestingly, the number of publications about the DMN has skyrocketed since 2007.

The many roles of the DMN

Ongoing research has revealed that the DMN is most active at rest, and its anatomical hubs mediate several key functions5:

- Posterior cingulate gyrus (the central core of the DMN): remembering the past and thinking about the future

- Medial prefrontal cortex: autobiographical memories, future goals and events, reflecting on one’s emotional self, and considering decisions about family members

- Dorsal medial subsystem: thinking about others, determining and inferring the purpose of other people’s actions

- Temporo-parietal junction: reflecting on the beliefs and emotions of others (known as “theory of mind”6)

- Lateral parietal junction: retrieval of social and conceptual knowledge

- Hippocampus: forming new memories, remembering the past, imagining the future

- Posterior-inferior parietal lobe: junction of auditory, visual, and somatic sensory information and attention

- Precuneus: Visual, sensory-motor, and attention.

Many terms have been used to describe the function of the DMN, including “daydreaming,” “auto-pilot,” “mind-wondering,” “reminiscing,” “contemplating,” “self-reflection,” “the neurological basis of the self,” and “seat of literary creativity.”

Psychiatric consequences of DMN deactivation

When another brain network, the attention network (which is also referred to as the task-positive network), is activated consciously and volitionally to perform a task that demands focus (such as text messaging, playing video games, or continuously interacting with social media sites), DMN activity declines.

Continue to: The DMN does not exist...

The DMN does not exist in infants, but starts to develop in childhood.7 It is enhanced by exercise, daydreaming, and sleep, activities that are common in childhood but have declined drastically with the widespread use of smartphones, video games, and social media, which for many youth occupy the bulk of their waking hours. Those tasks, which require continuous attention, deactivate the DMN. In fact, research has shown that addictive behavior decreases the connectivity of the DMN and suppresses its activity.8 Most children and adolescents can be regarded as essentially addicted to social media, text messaging, and video games. Unsurprisingly, serious psychiatric consequences follow.9

DMN dysfunction has been reported in several psychiatric conditions, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, autism, schizophrenia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance use.10-12 Impaired social interactions and communications, negative ruminations, suicidal ideas, and impaired encoding of long-term memories are some of the adverse effects of DMN dysfunction. The good news is that the DMN’s connectivity and functioning can be modulated and restored by meditation, mentalizing, exercise, psychotherapy, antidepressants, and psychedelics.13,14

The lockdown and stress of the COVID-19 pandemic added insult to injury and exacerbated mental illness in children by isolating them from each other and intensifying their technological addiction to fill the void of isolation. This crisis in youth mental health continues unabated, and calls for action to prevent grim outcomes. DMN dysfunction in youth can be reversed with treatment, but access to mental health care has become more challenging due to workforce shortages and insurance restrictions. Psychiatrists and parents must work diligently to treat psychiatrically affected youth, which has become a DaMN serious problem…

The advent of unprecedented technologies drastically altering the behavior of children and adolescents, compounded by prolonged isolation from a once-in-a-century pandemic, may have negatively impacted the normal connectivity of the human brain among youth, leading to the current alarming increase of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among this population.

The human brain is comprised of multiple large-scale networks that are functionally connected and control feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. As clinical neuroscientists, psychiatrists must consider the profound impact of a massive societal shift in human behavior on the functional connectivity of brain networks in health and disease. The advent of smartphones, social media, and video game addiction may have disrupted the developing brain networks in children and adolescents, leading to the current escalating epidemic of mental disorders in youth.

The major networks in the human brain include the default mode network (DMN), the salience network, the limbic system, the dorsal attention network, the central executive network, and the visual system.1 Each network connects several brain regions. Researchers can use functional MRI to detect the connectivity of those networks. When blood flow increases concurrently across 2 or 3 networks, this indicates those networks are functionally connected.

There was an old “dogma” that brain regions use energy only when activated and being used. Hans Berger, who developed the EEG in 1929, noticed electrical activity at rest and proposed that the brain is constantly busy, but his neurology peers did not take him seriously.2 In the 1950s, Louis Sokoloff noticed that brain metabolism was the same whether a person is at rest or doing math. In the 1970s, David Ingvar discovered that the highest blood flow in the frontal lobe occurred when a person was at rest.3 Finally, in 2007, Raichle et al4 used positron emission tomography scans to confirm that the frontal lobe is most active when a person is not doing anything. He labeled this phenomenon the DMN, comprising the medial fronto-parietal cortex, the posterior cingulate gyrus, the precuneus, and the angular gyrus. Interestingly, the number of publications about the DMN has skyrocketed since 2007.

The many roles of the DMN

Ongoing research has revealed that the DMN is most active at rest, and its anatomical hubs mediate several key functions5:

- Posterior cingulate gyrus (the central core of the DMN): remembering the past and thinking about the future

- Medial prefrontal cortex: autobiographical memories, future goals and events, reflecting on one’s emotional self, and considering decisions about family members

- Dorsal medial subsystem: thinking about others, determining and inferring the purpose of other people’s actions

- Temporo-parietal junction: reflecting on the beliefs and emotions of others (known as “theory of mind”6)

- Lateral parietal junction: retrieval of social and conceptual knowledge

- Hippocampus: forming new memories, remembering the past, imagining the future

- Posterior-inferior parietal lobe: junction of auditory, visual, and somatic sensory information and attention

- Precuneus: Visual, sensory-motor, and attention.

Many terms have been used to describe the function of the DMN, including “daydreaming,” “auto-pilot,” “mind-wondering,” “reminiscing,” “contemplating,” “self-reflection,” “the neurological basis of the self,” and “seat of literary creativity.”

Psychiatric consequences of DMN deactivation

When another brain network, the attention network (which is also referred to as the task-positive network), is activated consciously and volitionally to perform a task that demands focus (such as text messaging, playing video games, or continuously interacting with social media sites), DMN activity declines.

Continue to: The DMN does not exist...

The DMN does not exist in infants, but starts to develop in childhood.7 It is enhanced by exercise, daydreaming, and sleep, activities that are common in childhood but have declined drastically with the widespread use of smartphones, video games, and social media, which for many youth occupy the bulk of their waking hours. Those tasks, which require continuous attention, deactivate the DMN. In fact, research has shown that addictive behavior decreases the connectivity of the DMN and suppresses its activity.8 Most children and adolescents can be regarded as essentially addicted to social media, text messaging, and video games. Unsurprisingly, serious psychiatric consequences follow.9

DMN dysfunction has been reported in several psychiatric conditions, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, autism, schizophrenia, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance use.10-12 Impaired social interactions and communications, negative ruminations, suicidal ideas, and impaired encoding of long-term memories are some of the adverse effects of DMN dysfunction. The good news is that the DMN’s connectivity and functioning can be modulated and restored by meditation, mentalizing, exercise, psychotherapy, antidepressants, and psychedelics.13,14

The lockdown and stress of the COVID-19 pandemic added insult to injury and exacerbated mental illness in children by isolating them from each other and intensifying their technological addiction to fill the void of isolation. This crisis in youth mental health continues unabated, and calls for action to prevent grim outcomes. DMN dysfunction in youth can be reversed with treatment, but access to mental health care has become more challenging due to workforce shortages and insurance restrictions. Psychiatrists and parents must work diligently to treat psychiatrically affected youth, which has become a DaMN serious problem…

1. Yao Z, Hu B, Xie Y, et al. A review of structural and functional brain networks: small world and atlas. Brain Inform. 2015;2(1):45-52. doi:10.1007/s40708-015-0009-z

2. Raichle ME. The brain’s dark energy. Sci Am. 2010;302(3):44-49. doi:10.1038/scientific american0310-44

3. Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1-38. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011

4. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37(4):1083-1090; discussion 1097-1099. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041

5. Andrews-Hanna JR. The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(3):251-270. doi:10.1177/1073858411403316

6. Tsoukalas I. Theory of mind: towards an evolutionary theory. Evolutionary Psychological Science. 2018;4(1):38-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0112-x

7. Broyd SJ, Demanuele C, Debener S, et al. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(3):279-296. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002

8. Zhang R, Volkow ND. Brain default-mode network dysfunction in addiction. Neuroimage. 2019;200:313-331. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.036

9. Bommersbach TJ, McKean AJ, Olfson M, et al. National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among youth, 2011-2020. JAMA. 2023;329(17):1469-1477. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.4809

10. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ford JM. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:49-76. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143049

11. Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Wrocklage KM, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: a novel network-restricted topology approach. Neuroimage. 2018;176:489-498. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.005

12. Nagata JM, Chu J, Zamora G, et al. Screen time and obsessive-compulsive disorder among children 9-10 years old: a prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(3):390-396. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.10.023

13. Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, et al. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:48-73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016

14. Gattuso JJ, Perkins D, Ruffell S, et al. Default mode network modulation by psychedelics: a systematic review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26(3):155-188. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyac074

1. Yao Z, Hu B, Xie Y, et al. A review of structural and functional brain networks: small world and atlas. Brain Inform. 2015;2(1):45-52. doi:10.1007/s40708-015-0009-z

2. Raichle ME. The brain’s dark energy. Sci Am. 2010;302(3):44-49. doi:10.1038/scientific american0310-44

3. Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1-38. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011

4. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37(4):1083-1090; discussion 1097-1099. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041

5. Andrews-Hanna JR. The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(3):251-270. doi:10.1177/1073858411403316

6. Tsoukalas I. Theory of mind: towards an evolutionary theory. Evolutionary Psychological Science. 2018;4(1):38-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0112-x

7. Broyd SJ, Demanuele C, Debener S, et al. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(3):279-296. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002

8. Zhang R, Volkow ND. Brain default-mode network dysfunction in addiction. Neuroimage. 2019;200:313-331. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.036

9. Bommersbach TJ, McKean AJ, Olfson M, et al. National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits among youth, 2011-2020. JAMA. 2023;329(17):1469-1477. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.4809

10. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ford JM. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:49-76. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143049

11. Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Wrocklage KM, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: a novel network-restricted topology approach. Neuroimage. 2018;176:489-498. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.005

12. Nagata JM, Chu J, Zamora G, et al. Screen time and obsessive-compulsive disorder among children 9-10 years old: a prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(3):390-396. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.10.023

13. Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, et al. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:48-73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016

14. Gattuso JJ, Perkins D, Ruffell S, et al. Default mode network modulation by psychedelics: a systematic review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26(3):155-188. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyac074

High-dose stimulants for adult ADHD

Ms. H, age 30, presents to the outpatient clinic for a follow-up visit, where she reports difficulty paying attention to conversations, starting and completing tasks, and meeting deadlines. These challenges occur at work and home. Her psychiatric history includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Approximately 10 years ago, she underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Following surgery, Ms. H’s care team prescribed liquid formulations of medications whenever possible to minimize malabsorption. Ms. H may be a rapid metabolizer; she says the effects of her prescribed stimulants only last briefly, so she has to frequently redose. As a result, she often runs out of her monthly stimulant allotment earlier than expected.

Ms. H’s current medications include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine immediate-release (IR) 30 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg/d, and escitalopram oral solution 10 mg/d. Previous unsuccessful medication trials for her ADHD include methylphenidate IR 20 mg 3 times daily and lisdexamfetamine 70 mg/d. Ms. H reports that when her responsibilities increased at work or home, she took methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily to relieve her symptoms.

In the United States, ADHD affects an estimated 4.4% of adults age 18 to 44.1 The actual rate may be higher, however, as recent research has called into question the hypothesis that approximately 50% of cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood.2 Prevalence estimates relying on DSM-IV criteria (which were designed with children in mind) can underestimate this condition in adults. Newer data suggest that up to 90% of individuals with ADHD in childhood continue to experience significant ADHD symptoms into adulthood.2

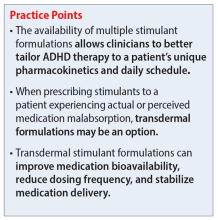

Unless contraindications are present, methylphenidate or amphetamine-based stimulants are the medications of choice for treating adult ADHD.3 Many formulations of both medications are available,4 which allows clinicians to better tailor therapy to each patient’s pharmacokinetics and daily schedule. Although there can be differences in response and tolerability, methylphenidate and amphetamine offer comparable efficacy and a similar adverse effect profile.5

Because amphetamine is more potent than methylphenidate, clinicians commonly start treatment with an amphetamine dose that is one-half to two-thirds the dose of methylphenidate.6 While both classes of stimulants inhibit the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from their storage sites in presynaptic nerve terminals.3

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 3 to 4 hours. The extended-release (XR) formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 12 hours (Table 13,7).4 The XR products usually immediately release a certain percentage of the medication, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. One methylphenidate XR product (Jornay) as well as serdexmethylphenidate/dexmethylphenidate (Azstarys) offer durations of action of 24 to 36 hours. Methylphenidate is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive metabolite ritalinic acid. Most of the medication (60% to 80%) is excreted in the urine as ritalinic acid.4 Theoretically, genetic variations in the CES1 and concomitant use of medications that compete with or alter this pathway may impact methylphenidate pharmacokinetics.8 However, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.4

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 4 to 6 hours. XR formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 13 hours (Table 23,7,9).4 One XR product, mixed salts of single amphetamine entity (Mydayis), has a duration of action of 16 hours. In XR formulations, a certain percentage of the medication is typically released immediately, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. Amphetamine is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hydroxylation and oxidative deamination. Genetic variability in amphetamine metabolism may be relevant due to CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Ultra-rapid metabolizers might need higher doses, while poor metabolizers might require smaller amounts and may be more susceptible to adverse effects.4 However, there is currently insufficient data supporting gene/medication concentration relationships. As is the case with methylphenidate, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.6

Continue to: Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Medication malabsorption following bariatric surgery is a significant concern. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Padwal et al10 found that in one-third of these studies, decreased absorption following bariatric surgery may be present in patients taking medications that have poor absorption, high lipophilicity, or enterohepatic recirculation. Childress et al11 found that methylphenidate IR and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine are both well absorbed, with bioavailability percentages of 100% and 90%, respectively. Additional research shows both stimulants have rapid absorption rates but relatively poor bioavailability.12 In one study analyzing the dissolution of common psychiatric medications, methylphenidate was shown to dissolve slightly more in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery model (80 mg) compared to controls (70 mg).13 One case indicated potential methylphenidate toxicity following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery,14 while another suggested impaired absorption following the same procedure.15 A case-control design study assessing the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on the pharmacokinetic properties of lisdexamfetamine found no significant differences between the Roux-en-Y group (n = 10) and nonsurgical controls (n = 10). The investigators concluded that while data suggest adjusting lisdexamfetamine dosing following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is unnecessary, there may be interindividual differences, and individualized dosing regimens may be needed.16

When managing patients who might be experiencing medication malabsorption, it may be helpful to use dosage forms that avoid disintegration, acidic environments, and slow dissolution. Because they are more rapidly absorbed and not susceptible to disintegration and dissolution, liquid formulations are recommended.17 For medications that are not available as a liquid, an IR formulation is recommended.18

Using nonoral routes of administration that avoid the anatomical changes of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered for patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.17 The methylphenidate transdermal patch, a medication delivery system that avoids gut and hepatic first-pass metabolism, can improve medication bioavailability, reduce dose frequency, and stabilize medication delivery. It is available in 4 sizes/dosages: 10 mg/9 hours, 15 mg/9 hours, 20 mg/9 hours, and 30 mg/9 hours. Methylphenidate is delivered at a steady rate based upon patch size. The onset of action of the patch is approximately 2 hours, and patients should wear the patch for 9 hours, then remove it. Methylphenidate will still be absorbed up to 2 to 3 hours after patch removal. Appropriate application and removal of the patch is important for optimal effectiveness and to avoid adverse effects.4

In March 2022, t

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. H emphasizes her desire to maintain functionality in all areas of life, while her care team reiterates the risks of continuing to take high-dose stimulants. Both Ms. H and her care team acknowledge that stimulant usage could be worsening her anxiety, and that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery may be a possible explanation for her dosing challenges.

Continue to: Following consultation with the pharmacist...

Following consultation with the pharmacist, the care team explains the possible pharmacokinetic benefits of using the methylphenidate transdermal patch. After completing the prior authorization paperwork, Ms. H is started on the 30 mg/d patch. This dose was selected because she previously tolerated high-dose stimulants, including methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily. At a follow-up visit 1 month after starting the patch, Ms. H reports an improvement in her ADHD symptoms and says she is not experiencing any adverse effects.

Related Resources

- DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

- Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):16-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine sulfate • Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo

Atenolol • Tenormin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin, Focalin XR

Dextroamphetamine transdermal • Xelstrym

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, Dexedrine Spansule, ProCentra, Zenzedi

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Aptensio XR, Adhansia XR, Concerta, Cotempla, Jornay PM, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Qullichew ER, Quillivant XR, Relexxii, Ritalin, Ritalin LA

Methylphenidate transdermal • Daytrana

Mixed amphetamine salts • Adderall, Adderall XR

Mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine • Mydayis

Serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate • Azstarys

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716-723. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

2. Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142-151. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

3. Cleveland KW, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Schwinghammer TL, Malone PM, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy Principles & Practice. 6th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://ppp.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3114§ionid=261474885

4. Steingard R, Taskiran S, Connor DF, et al. New formulations of stimulants: an update for clinicians. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(5):324-339. doi:10.1089/cap.2019.0043

5. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.001

6. Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamines utilized in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):678-689. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0071

7. Mullen S. Medication Table 2: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In: English C, ed. CPNP Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Review Course. 2022-2023 ed. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; 2022.

8. Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, et al. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1241-1248. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015

9. Xelstrym [package insert]. Miami, FL: Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2022.

10. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x

11. Childress AC, Komolova M, Sallee FR. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):937-974. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1675636

12. Markowitz JS, Melchert PW. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of psychostimulants. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):393-416. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.003

13. Seaman JS, Bowers SP, Dixon P, et al. Dissolution of common psychiatric medications in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass model. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):250-253. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.250

14. Ludvigsson M, Haenni A. Methylphenidate toxicity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):e55-e57. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.015

15. Azran C, Langguth P, Dahan A. Impaired oral absorption of methylphenidate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1245-1247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.003

16. Steffen KJ, Mohammad AS, Roerig JL, et al. Lisdexamfetamine pharmacokinetic comparison between patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and nonsurgical controls. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4289-4294. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04969-4

17. Buxton ILO. Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. In: Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2189§ionid=166182905

18. DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

Ms. H, age 30, presents to the outpatient clinic for a follow-up visit, where she reports difficulty paying attention to conversations, starting and completing tasks, and meeting deadlines. These challenges occur at work and home. Her psychiatric history includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Approximately 10 years ago, she underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Following surgery, Ms. H’s care team prescribed liquid formulations of medications whenever possible to minimize malabsorption. Ms. H may be a rapid metabolizer; she says the effects of her prescribed stimulants only last briefly, so she has to frequently redose. As a result, she often runs out of her monthly stimulant allotment earlier than expected.

Ms. H’s current medications include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine immediate-release (IR) 30 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg/d, and escitalopram oral solution 10 mg/d. Previous unsuccessful medication trials for her ADHD include methylphenidate IR 20 mg 3 times daily and lisdexamfetamine 70 mg/d. Ms. H reports that when her responsibilities increased at work or home, she took methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily to relieve her symptoms.

In the United States, ADHD affects an estimated 4.4% of adults age 18 to 44.1 The actual rate may be higher, however, as recent research has called into question the hypothesis that approximately 50% of cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood.2 Prevalence estimates relying on DSM-IV criteria (which were designed with children in mind) can underestimate this condition in adults. Newer data suggest that up to 90% of individuals with ADHD in childhood continue to experience significant ADHD symptoms into adulthood.2

Unless contraindications are present, methylphenidate or amphetamine-based stimulants are the medications of choice for treating adult ADHD.3 Many formulations of both medications are available,4 which allows clinicians to better tailor therapy to each patient’s pharmacokinetics and daily schedule. Although there can be differences in response and tolerability, methylphenidate and amphetamine offer comparable efficacy and a similar adverse effect profile.5

Because amphetamine is more potent than methylphenidate, clinicians commonly start treatment with an amphetamine dose that is one-half to two-thirds the dose of methylphenidate.6 While both classes of stimulants inhibit the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from their storage sites in presynaptic nerve terminals.3

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 3 to 4 hours. The extended-release (XR) formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 12 hours (Table 13,7).4 The XR products usually immediately release a certain percentage of the medication, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. One methylphenidate XR product (Jornay) as well as serdexmethylphenidate/dexmethylphenidate (Azstarys) offer durations of action of 24 to 36 hours. Methylphenidate is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive metabolite ritalinic acid. Most of the medication (60% to 80%) is excreted in the urine as ritalinic acid.4 Theoretically, genetic variations in the CES1 and concomitant use of medications that compete with or alter this pathway may impact methylphenidate pharmacokinetics.8 However, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.4

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 4 to 6 hours. XR formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 13 hours (Table 23,7,9).4 One XR product, mixed salts of single amphetamine entity (Mydayis), has a duration of action of 16 hours. In XR formulations, a certain percentage of the medication is typically released immediately, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. Amphetamine is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hydroxylation and oxidative deamination. Genetic variability in amphetamine metabolism may be relevant due to CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Ultra-rapid metabolizers might need higher doses, while poor metabolizers might require smaller amounts and may be more susceptible to adverse effects.4 However, there is currently insufficient data supporting gene/medication concentration relationships. As is the case with methylphenidate, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.6

Continue to: Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Medication malabsorption following bariatric surgery is a significant concern. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Padwal et al10 found that in one-third of these studies, decreased absorption following bariatric surgery may be present in patients taking medications that have poor absorption, high lipophilicity, or enterohepatic recirculation. Childress et al11 found that methylphenidate IR and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine are both well absorbed, with bioavailability percentages of 100% and 90%, respectively. Additional research shows both stimulants have rapid absorption rates but relatively poor bioavailability.12 In one study analyzing the dissolution of common psychiatric medications, methylphenidate was shown to dissolve slightly more in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery model (80 mg) compared to controls (70 mg).13 One case indicated potential methylphenidate toxicity following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery,14 while another suggested impaired absorption following the same procedure.15 A case-control design study assessing the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on the pharmacokinetic properties of lisdexamfetamine found no significant differences between the Roux-en-Y group (n = 10) and nonsurgical controls (n = 10). The investigators concluded that while data suggest adjusting lisdexamfetamine dosing following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is unnecessary, there may be interindividual differences, and individualized dosing regimens may be needed.16

When managing patients who might be experiencing medication malabsorption, it may be helpful to use dosage forms that avoid disintegration, acidic environments, and slow dissolution. Because they are more rapidly absorbed and not susceptible to disintegration and dissolution, liquid formulations are recommended.17 For medications that are not available as a liquid, an IR formulation is recommended.18

Using nonoral routes of administration that avoid the anatomical changes of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered for patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.17 The methylphenidate transdermal patch, a medication delivery system that avoids gut and hepatic first-pass metabolism, can improve medication bioavailability, reduce dose frequency, and stabilize medication delivery. It is available in 4 sizes/dosages: 10 mg/9 hours, 15 mg/9 hours, 20 mg/9 hours, and 30 mg/9 hours. Methylphenidate is delivered at a steady rate based upon patch size. The onset of action of the patch is approximately 2 hours, and patients should wear the patch for 9 hours, then remove it. Methylphenidate will still be absorbed up to 2 to 3 hours after patch removal. Appropriate application and removal of the patch is important for optimal effectiveness and to avoid adverse effects.4

In March 2022, t

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. H emphasizes her desire to maintain functionality in all areas of life, while her care team reiterates the risks of continuing to take high-dose stimulants. Both Ms. H and her care team acknowledge that stimulant usage could be worsening her anxiety, and that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery may be a possible explanation for her dosing challenges.

Continue to: Following consultation with the pharmacist...

Following consultation with the pharmacist, the care team explains the possible pharmacokinetic benefits of using the methylphenidate transdermal patch. After completing the prior authorization paperwork, Ms. H is started on the 30 mg/d patch. This dose was selected because she previously tolerated high-dose stimulants, including methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily. At a follow-up visit 1 month after starting the patch, Ms. H reports an improvement in her ADHD symptoms and says she is not experiencing any adverse effects.

Related Resources

- DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

- Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):16-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine sulfate • Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo

Atenolol • Tenormin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin, Focalin XR

Dextroamphetamine transdermal • Xelstrym

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, Dexedrine Spansule, ProCentra, Zenzedi

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Aptensio XR, Adhansia XR, Concerta, Cotempla, Jornay PM, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Qullichew ER, Quillivant XR, Relexxii, Ritalin, Ritalin LA

Methylphenidate transdermal • Daytrana

Mixed amphetamine salts • Adderall, Adderall XR

Mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine • Mydayis

Serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate • Azstarys

Ms. H, age 30, presents to the outpatient clinic for a follow-up visit, where she reports difficulty paying attention to conversations, starting and completing tasks, and meeting deadlines. These challenges occur at work and home. Her psychiatric history includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Approximately 10 years ago, she underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Following surgery, Ms. H’s care team prescribed liquid formulations of medications whenever possible to minimize malabsorption. Ms. H may be a rapid metabolizer; she says the effects of her prescribed stimulants only last briefly, so she has to frequently redose. As a result, she often runs out of her monthly stimulant allotment earlier than expected.

Ms. H’s current medications include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine immediate-release (IR) 30 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg/d, and escitalopram oral solution 10 mg/d. Previous unsuccessful medication trials for her ADHD include methylphenidate IR 20 mg 3 times daily and lisdexamfetamine 70 mg/d. Ms. H reports that when her responsibilities increased at work or home, she took methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily to relieve her symptoms.

In the United States, ADHD affects an estimated 4.4% of adults age 18 to 44.1 The actual rate may be higher, however, as recent research has called into question the hypothesis that approximately 50% of cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood.2 Prevalence estimates relying on DSM-IV criteria (which were designed with children in mind) can underestimate this condition in adults. Newer data suggest that up to 90% of individuals with ADHD in childhood continue to experience significant ADHD symptoms into adulthood.2

Unless contraindications are present, methylphenidate or amphetamine-based stimulants are the medications of choice for treating adult ADHD.3 Many formulations of both medications are available,4 which allows clinicians to better tailor therapy to each patient’s pharmacokinetics and daily schedule. Although there can be differences in response and tolerability, methylphenidate and amphetamine offer comparable efficacy and a similar adverse effect profile.5

Because amphetamine is more potent than methylphenidate, clinicians commonly start treatment with an amphetamine dose that is one-half to two-thirds the dose of methylphenidate.6 While both classes of stimulants inhibit the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from their storage sites in presynaptic nerve terminals.3

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 3 to 4 hours. The extended-release (XR) formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 12 hours (Table 13,7).4 The XR products usually immediately release a certain percentage of the medication, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. One methylphenidate XR product (Jornay) as well as serdexmethylphenidate/dexmethylphenidate (Azstarys) offer durations of action of 24 to 36 hours. Methylphenidate is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive metabolite ritalinic acid. Most of the medication (60% to 80%) is excreted in the urine as ritalinic acid.4 Theoretically, genetic variations in the CES1 and concomitant use of medications that compete with or alter this pathway may impact methylphenidate pharmacokinetics.8 However, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.4

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 4 to 6 hours. XR formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 13 hours (Table 23,7,9).4 One XR product, mixed salts of single amphetamine entity (Mydayis), has a duration of action of 16 hours. In XR formulations, a certain percentage of the medication is typically released immediately, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. Amphetamine is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hydroxylation and oxidative deamination. Genetic variability in amphetamine metabolism may be relevant due to CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Ultra-rapid metabolizers might need higher doses, while poor metabolizers might require smaller amounts and may be more susceptible to adverse effects.4 However, there is currently insufficient data supporting gene/medication concentration relationships. As is the case with methylphenidate, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.6

Continue to: Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Medication malabsorption following bariatric surgery is a significant concern. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Padwal et al10 found that in one-third of these studies, decreased absorption following bariatric surgery may be present in patients taking medications that have poor absorption, high lipophilicity, or enterohepatic recirculation. Childress et al11 found that methylphenidate IR and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine are both well absorbed, with bioavailability percentages of 100% and 90%, respectively. Additional research shows both stimulants have rapid absorption rates but relatively poor bioavailability.12 In one study analyzing the dissolution of common psychiatric medications, methylphenidate was shown to dissolve slightly more in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery model (80 mg) compared to controls (70 mg).13 One case indicated potential methylphenidate toxicity following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery,14 while another suggested impaired absorption following the same procedure.15 A case-control design study assessing the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on the pharmacokinetic properties of lisdexamfetamine found no significant differences between the Roux-en-Y group (n = 10) and nonsurgical controls (n = 10). The investigators concluded that while data suggest adjusting lisdexamfetamine dosing following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is unnecessary, there may be interindividual differences, and individualized dosing regimens may be needed.16

When managing patients who might be experiencing medication malabsorption, it may be helpful to use dosage forms that avoid disintegration, acidic environments, and slow dissolution. Because they are more rapidly absorbed and not susceptible to disintegration and dissolution, liquid formulations are recommended.17 For medications that are not available as a liquid, an IR formulation is recommended.18

Using nonoral routes of administration that avoid the anatomical changes of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered for patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.17 The methylphenidate transdermal patch, a medication delivery system that avoids gut and hepatic first-pass metabolism, can improve medication bioavailability, reduce dose frequency, and stabilize medication delivery. It is available in 4 sizes/dosages: 10 mg/9 hours, 15 mg/9 hours, 20 mg/9 hours, and 30 mg/9 hours. Methylphenidate is delivered at a steady rate based upon patch size. The onset of action of the patch is approximately 2 hours, and patients should wear the patch for 9 hours, then remove it. Methylphenidate will still be absorbed up to 2 to 3 hours after patch removal. Appropriate application and removal of the patch is important for optimal effectiveness and to avoid adverse effects.4

In March 2022, t

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. H emphasizes her desire to maintain functionality in all areas of life, while her care team reiterates the risks of continuing to take high-dose stimulants. Both Ms. H and her care team acknowledge that stimulant usage could be worsening her anxiety, and that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery may be a possible explanation for her dosing challenges.

Continue to: Following consultation with the pharmacist...

Following consultation with the pharmacist, the care team explains the possible pharmacokinetic benefits of using the methylphenidate transdermal patch. After completing the prior authorization paperwork, Ms. H is started on the 30 mg/d patch. This dose was selected because she previously tolerated high-dose stimulants, including methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily. At a follow-up visit 1 month after starting the patch, Ms. H reports an improvement in her ADHD symptoms and says she is not experiencing any adverse effects.

Related Resources

- DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

- Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):16-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine sulfate • Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo

Atenolol • Tenormin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin, Focalin XR

Dextroamphetamine transdermal • Xelstrym

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, Dexedrine Spansule, ProCentra, Zenzedi

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Aptensio XR, Adhansia XR, Concerta, Cotempla, Jornay PM, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Qullichew ER, Quillivant XR, Relexxii, Ritalin, Ritalin LA

Methylphenidate transdermal • Daytrana

Mixed amphetamine salts • Adderall, Adderall XR

Mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine • Mydayis

Serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate • Azstarys

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716-723. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

2. Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142-151. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

3. Cleveland KW, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Schwinghammer TL, Malone PM, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy Principles & Practice. 6th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://ppp.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3114§ionid=261474885

4. Steingard R, Taskiran S, Connor DF, et al. New formulations of stimulants: an update for clinicians. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(5):324-339. doi:10.1089/cap.2019.0043

5. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.001

6. Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamines utilized in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):678-689. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0071

7. Mullen S. Medication Table 2: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In: English C, ed. CPNP Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Review Course. 2022-2023 ed. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; 2022.

8. Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, et al. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1241-1248. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015

9. Xelstrym [package insert]. Miami, FL: Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2022.

10. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x

11. Childress AC, Komolova M, Sallee FR. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):937-974. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1675636

12. Markowitz JS, Melchert PW. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of psychostimulants. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):393-416. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.003

13. Seaman JS, Bowers SP, Dixon P, et al. Dissolution of common psychiatric medications in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass model. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):250-253. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.250

14. Ludvigsson M, Haenni A. Methylphenidate toxicity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):e55-e57. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.015

15. Azran C, Langguth P, Dahan A. Impaired oral absorption of methylphenidate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1245-1247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.003

16. Steffen KJ, Mohammad AS, Roerig JL, et al. Lisdexamfetamine pharmacokinetic comparison between patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and nonsurgical controls. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4289-4294. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04969-4

17. Buxton ILO. Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. In: Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2189§ionid=166182905

18. DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716-723. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

2. Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142-151. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

3. Cleveland KW, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Schwinghammer TL, Malone PM, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy Principles & Practice. 6th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://ppp.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3114§ionid=261474885

4. Steingard R, Taskiran S, Connor DF, et al. New formulations of stimulants: an update for clinicians. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(5):324-339. doi:10.1089/cap.2019.0043

5. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.001

6. Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamines utilized in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):678-689. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0071

7. Mullen S. Medication Table 2: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In: English C, ed. CPNP Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Review Course. 2022-2023 ed. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; 2022.

8. Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, et al. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1241-1248. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015

9. Xelstrym [package insert]. Miami, FL: Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2022.

10. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x

11. Childress AC, Komolova M, Sallee FR. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):937-974. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1675636

12. Markowitz JS, Melchert PW. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of psychostimulants. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):393-416. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.003

13. Seaman JS, Bowers SP, Dixon P, et al. Dissolution of common psychiatric medications in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass model. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):250-253. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.250

14. Ludvigsson M, Haenni A. Methylphenidate toxicity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):e55-e57. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.015

15. Azran C, Langguth P, Dahan A. Impaired oral absorption of methylphenidate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1245-1247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.003

16. Steffen KJ, Mohammad AS, Roerig JL, et al. Lisdexamfetamine pharmacokinetic comparison between patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and nonsurgical controls. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4289-4294. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04969-4

17. Buxton ILO. Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. In: Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2189§ionid=166182905

18. DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

Serious complications due to ‘huffing’

CASE A relapse and crisis

Ms. G, age 32, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by police after being found in a stupor-like state in a public restroom. The consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry team assesses her for concerns of self-harm and suicide behavior. Ms. G discloses that she “huffs” an average of 4 canisters of air dusters daily to cope with psychosocial stressors and achieve a euphoric state. She recently lost her job, which led to homelessness, financial difficulties, a relapse to aerosol use after 2 years of abstinence, and stealing aerosol cans. The latest incident follows 2 prior arrests, which led officers to bring her to the ED for medical evaluation. Ms. G has a history of bipolar disorder (BD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), insomnia, and inhalant use disorder.

HISTORY Inhalant abuse and suicide attempt

Ms. G reports a longstanding history of severe inhalant abuse, primarily with air dusters due to their accessibility and low cost. She previously underwent inpatient rehab for inhalant abuse, and received inpatient psychiatry treatment 5 years ago for a suicide attempt by overdose linked to psychosocial stressors. In addition to BD, GAD, insomnia, and inhalant use disorder, Ms. G has a history of neuropathy, seizures, and recurrent hypokalemia. She is single and does not have insurance.

[polldaddy:12318871]

The authors’ observations

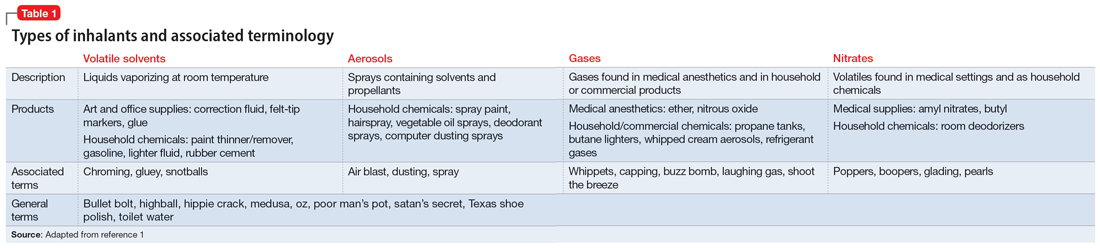

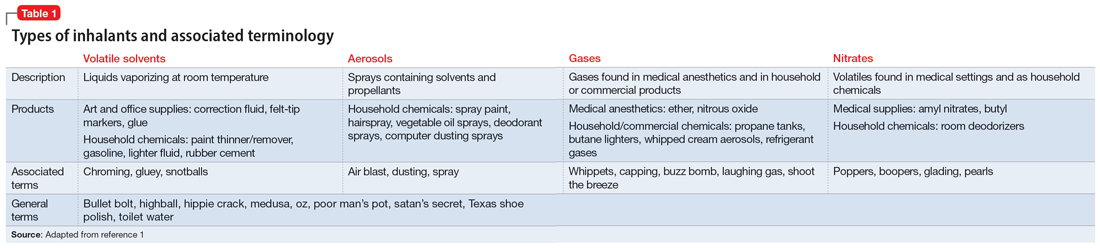

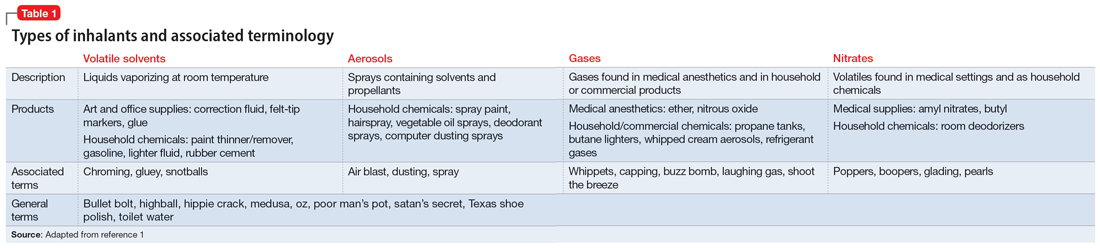

Inhalant abuse is the intentional inhalation of volatile substances to achieve an altered mental state. Inhalants are commercially available products that can produce intoxication if inhaled, such as glue, toluene, spray paint, gasoline, and lighter fluid (Table 11).

The epidemiology of inhalant abuse is difficult to accurately report due to a lack of recognition and social stigma. Due to inhalants’ ease of access and low cost, this form of substance abuse is popular among adolescents, adults of low socioeconomic status, individuals who live in rural areas, and those living in institutions. Inhalants act as reinforcers, producing a euphoric state. Rapid pulmonary absorption and lipid solubility of the substance rapidly alters the brain. Inhalant abuse can result in chemical and thermal burns, withdrawal symptoms, persistent mental illness, and catastrophic medical emergencies such as ventricular arrhythmias leading to disruptive myocardial electrical propagation. Chronic abuse can cause irreversible neurological and neuropsychological effects, cardiomyopathy, rapid airway compromise, pulmonary debilitations, renal tubular acidosis, bone marrow toxicity, reduced immunity, and peripheral neuropathy.2 Ms. G’s diagnosis of inhalant use disorder was based on her mental state and history of severe inhalant misuse, specifically with air dusters. Several additional factors further support this diagnosis, including the fact she survived a suicide attempt by overdose 5 years ago, had an inpatient rehabilitation placement for inhalant abuse, experiences insomnia, and was attempting to self-treat a depressive episode relapse with inhalants.

EVALUATION Depressed but cooperative

After being monitored in the ED for several hours, Ms. G is no longer in a stupor-like state. She has poor body habitus, appears older than her stated age, and is unkempt in appearance/attire. She is mildly distressed but relatively cooperative and engaged during the interview. Ms. G has a depressed mood and is anxious, with mood-congruent affect, and is tearful at times, especially when discussing recent stressors. She denies suicidality, homicidality, paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations. Her thought process is linear, goal-directed, and logical. She has fair insight, but relatively poor and impulsive judgment. The nursing staff expresses concerns that Ms. G was possibly responding to internal stimuli and behaving bizarrely during her initial presentation; this was not evident upon examination.

Ms. G reports having acute-on-chronic headaches, intermittent myalgias and weakness in her lower extremities (acute), and polyneuropathy (chronic). She denies a history of manic episodes or psychosis but reports previous relative hypomanic episodes that vacillated with periods of recurrent depressive episodes. Ms. G denies using illicit substances other than tobacco and inhalants. She says she had adhered to her outpatient psychiatric management services and medication regimen (duloxetine 60 mg/d at bedtime for mood/migraines, trazodone 150 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, ziprasidone 40 mg/d at bedtime for BD, carbamazepine 200 mg twice daily for neuropathy/migraines, gabapentin 400 mg 3 times daily for neuropathy migraines/anxiety, and propranolol 10 mg 3 times daily for anxiety/tremors/migraine prophylaxis) until 4 days before her current presentation to the ED, when she used inhalants and was arrested.

Ms. G’s vitals are mostly unremarkable, but her heart rate is 116 beats per minute. There are no acute findings on physical examination. She is not pregnant, and her creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, complete blood count, and thyroid-stimulating hormone are all within normal limits. Her blood sugar is high (120 mg/dL; reference range 70 to 100 mg/dL). She has slight transaminitis with high aspartate aminotransferase (93 U/L; reference range 17 to 59 U/L) and high alanine aminotransferase (69 U/L; reference range 20 to 35 U/L); chronic hypokalemia (2.4 mmol/L; reference range 3.5 to 5.2 mmol/L), which leads the primary team to initiate a potassium replacement protocol; lactic acidosis (2.2 mmol/L; normal levels <2 mmol/L); and creatine kinase (CK) 5,930 U/L.

[polldaddy:12318873]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

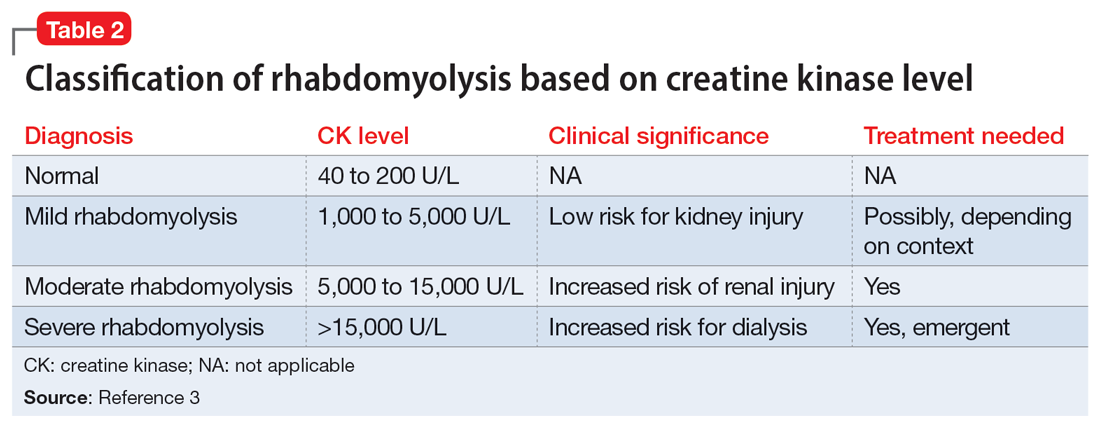

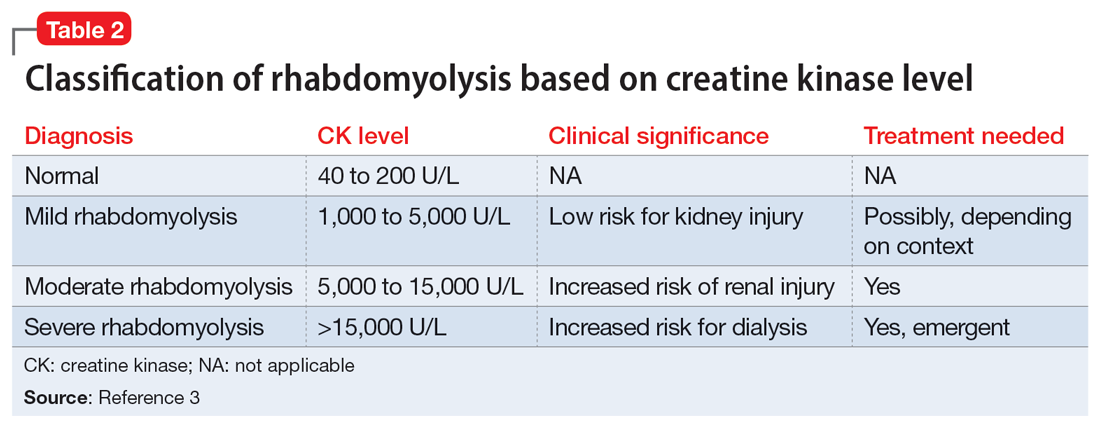

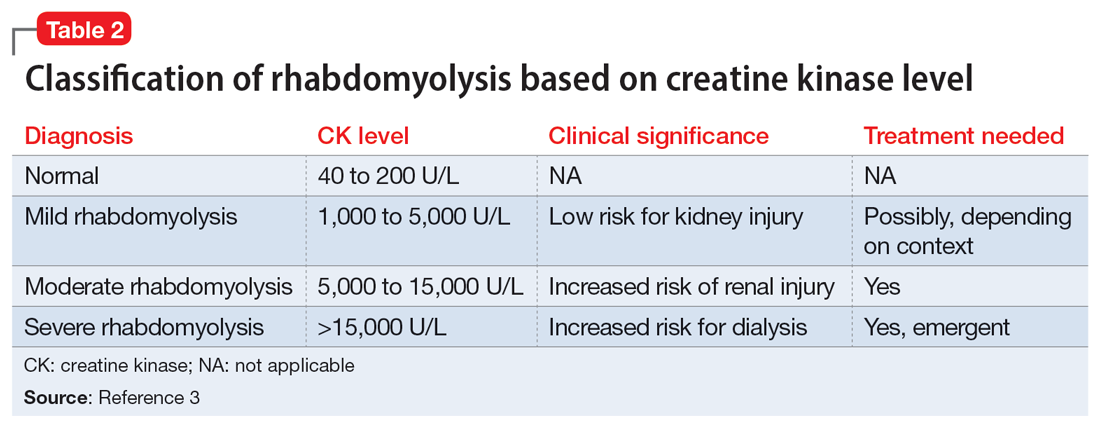

Efforts to improve the laboratory diagnosis of inhalant abuse are ongoing, but they have not yet been widely implemented. Systemic screening and assessment of inhalant use can help prevent and treat complications. For Ms. G, we considered several possible complications, including hypoglycemia. Although the classic triad of myalgia, weakness, and myoglobinuria (tea-colored urine) was not present, elevated CK levels in the context of Ms. G’s intermittent myalgia and lower extremity weakness led us to suspect she was experiencing moderate rhabdomyolysis (Table 23).

Rhabdomyolysis can be caused by several factors, including drug abuse, trauma, neuromuscular syndrome, and immobility. Treatment is mainly supportive, with a focus on preserving the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) and renal function through vigorous rehydration.4 We postulated Ms. G’s rhabdomyolysis was caused by muscle damage directly resulting from inhalant abuse and compounded by her remaining in prolonged fixed position on the ground after overdosing on inhalants.

TREATMENT Rehydration and psychotropics

The treatment team initiates IV fluid hydration of chloride 0.9% 150 mL/h and monitors Ms. G until she is stable and the trajectory of her CK levels begins to decline. On hospital Day 2, Ms. G’s CK decreases to 2,475 U/L and her lactic acid levels normalize. Ms. G restarts her regimen of duloxetine 60 mg/d, trazodone 150 mg/d, ziprasidone 40 mg/d, carbamazepine 200 mg twice daily, gabapentin 400 mg 3 times daily, and propranolol 10 mg 3 times daily. The team adds quetiapine 25 mg as needed for hallucinations, paranoia, and/or anxiety. Ms. G is closely monitored due to the potential risk of toxicity-induced or withdrawal-induced psychotic symptoms.

[polldaddy:12318869]

The authors’ observations

Presently, there are no effective treatments for acute inhalant intoxication or withdrawal, which makes supportive care and vigilant monitoring the only options.5 Although clinical research has not led to any FDA-approved treatments for chronic inhalant use disorder, a multipronged biopsychosocial treatment approach is critical in light of the negative consequences of inhalant abuse, including poor academic performance, criminal behavior, abuse of other substances, social maladjustment, low self-esteem, and suicidality.6

Ms. G had a moderate form of rhabdomyolysis, which was managed with IV fluid rehydration. Education and counseling were crucial to help Ms. G understand the unintended complications and potentially life-threatening consequences of inhalant abuse, with rehabilitation services to encourage abstinence. Ms. G had previously undergone successful inpatient rehabilitation and was willing to start such services again. She reported success with gabapentin for her polyneuropathy and migraines, which may be long-term consequences of prolonged inhalant abuse with neurological lesions. Ziprasidone may have mitigated some of the impulsivity and hypomanic symptoms of her BD that could make her more likely to engage in risky self-harm behaviors.

Continue to: After extensive discussion...

After extensive discussion on the long-term complications of inhalant abuse, Ms. G was motivated, cooperative, and sought care to return to rehabilitation services. The CL psychiatry team collaborated with the social work team to address the psychosocial components of Ms. G’s homelessness and facilitated an application for a local resource to obtain rehabilitation placement and living assistance. Her years of abstinence from inhalant use and success with rehabilitation demonstrate the need for a multimodal approach to manage and treat inhalant use disorder. Outpatient follow-up arrangements were made with local mental health resources.

OUTCOME Improved outlook and discharge

Ms. G reports improved mood and willingness to change her substance use habits. The treatment team counsels her on the acute risk of fatal arrhythmias and end-organ complications of inhalant abuse. They warn her about the potential long-term effects of mood alterations, neurological lesions, and polyneuropathy that could possibly worsen with substance abuse. Ms. G expresses appreciation for this counseling, the help associated with her aftercare, and the referral to restart the 30-day inpatient rehabilitation services. The team arranges follow-up with outpatient psychiatry and outpatient therapy services to enhance Ms. G’s coping skills and mitigate her reliance on inhalants to regulate her mood.

Bottom Line

Inhalant use is a poorly understood form of substance abuse that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations. It can lead to life-threatening medical emergencies such as rhabdomyolysis. Clinicians need to be able to identify and manage inhalant abuse and associated complications, as well as provide appropriate education and counseling to prevent further misuse.

Related Resources

- Gude J, Bisen V, Fujii K. Medication-induced rhabdomyolysis. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(2):39-40. doi:10.12788/cp.0332

- Waldman W, Kabata PM, Dines AM, et al. Rhabdomyolysis related to acute recreational drug toxicity--a Euro-DEN study. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246297. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0246297

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Propranolol • Inderal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Trazodone • Oleptro

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Ahern NR, Falsafi N. Inhalant abuse: youth at risk. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2013;51(8):19-24. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130612-02

2. Howard MO, Bowen SE, Garland EL, et al. Inhalant use and inhalant use disorders in the United States. Addict Sci Clin Prac. 2011;6(1):18-31.

3. Farkas J. Rhabdomyolysis. Internet Book of Critical Care. June 25, 2021. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://emcrit.org/ibcc/rhabdo/

4. Torres PA, Helmstetter JA, Kaye AM, et al. Rhabdomyolysis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):58-69.

5. Muller AA, Muller GF. Inhalant abuse. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32(5):447-448. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2006.05.018

6. Kozel N, Sloboda Z, De La Rosa M, eds. Epidemiology of Inhalant Abuse: An International Perspective; Nida Research Monograph 148. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1995. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://archives.nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/monograph148.pdf

CASE A relapse and crisis