User login

Teachable Moments

With World Stroke Day scheduled for Saturday, a frequent speaker for the National Stroke Association (NSA) wants to remind hospitalists to push their patients to know their risk factors.

"They have an excellent opportunity to be an educator, particularly because of that captive audience," says David Willis, MD, a primary-care physician in Ocala, Fla., who frequently holds educational events for the NSA.

Dr. Willis cites data from a 2010 survey (PDF) compiled by NSA and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals that shows while more than 75% of healthcare providers reported talking to patients about atrial fibrillation (AF) and stroke, nearly half don't recall the conversation. And just 40% of patients initiate the discussion.

Dr. Willis, who served on the steering committee that interpreted the survey results, says that hospitalists dealing with AF patients can "quarterback" care plans and help improve communication with post-discharge physicians, be they primary care or specialists.

"We may not be getting that thought across as well as we think we are," he says.

Improved communication and transitions will become more important as unnecessary readmissions related to AF or stroke financially impact physicians because the government may reduce reimbursements for repeated hospital visits. Dr. Willis suggests that hospitalists take the reins of integrating their patient education efforts into checklists, health information technology, or some formalized process.

"My experience is, if you create protocols, they usually work better than educating people at a provider level," he says.

With World Stroke Day scheduled for Saturday, a frequent speaker for the National Stroke Association (NSA) wants to remind hospitalists to push their patients to know their risk factors.

"They have an excellent opportunity to be an educator, particularly because of that captive audience," says David Willis, MD, a primary-care physician in Ocala, Fla., who frequently holds educational events for the NSA.

Dr. Willis cites data from a 2010 survey (PDF) compiled by NSA and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals that shows while more than 75% of healthcare providers reported talking to patients about atrial fibrillation (AF) and stroke, nearly half don't recall the conversation. And just 40% of patients initiate the discussion.

Dr. Willis, who served on the steering committee that interpreted the survey results, says that hospitalists dealing with AF patients can "quarterback" care plans and help improve communication with post-discharge physicians, be they primary care or specialists.

"We may not be getting that thought across as well as we think we are," he says.

Improved communication and transitions will become more important as unnecessary readmissions related to AF or stroke financially impact physicians because the government may reduce reimbursements for repeated hospital visits. Dr. Willis suggests that hospitalists take the reins of integrating their patient education efforts into checklists, health information technology, or some formalized process.

"My experience is, if you create protocols, they usually work better than educating people at a provider level," he says.

With World Stroke Day scheduled for Saturday, a frequent speaker for the National Stroke Association (NSA) wants to remind hospitalists to push their patients to know their risk factors.

"They have an excellent opportunity to be an educator, particularly because of that captive audience," says David Willis, MD, a primary-care physician in Ocala, Fla., who frequently holds educational events for the NSA.

Dr. Willis cites data from a 2010 survey (PDF) compiled by NSA and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals that shows while more than 75% of healthcare providers reported talking to patients about atrial fibrillation (AF) and stroke, nearly half don't recall the conversation. And just 40% of patients initiate the discussion.

Dr. Willis, who served on the steering committee that interpreted the survey results, says that hospitalists dealing with AF patients can "quarterback" care plans and help improve communication with post-discharge physicians, be they primary care or specialists.

"We may not be getting that thought across as well as we think we are," he says.

Improved communication and transitions will become more important as unnecessary readmissions related to AF or stroke financially impact physicians because the government may reduce reimbursements for repeated hospital visits. Dr. Willis suggests that hospitalists take the reins of integrating their patient education efforts into checklists, health information technology, or some formalized process.

"My experience is, if you create protocols, they usually work better than educating people at a provider level," he says.

Specialty Hospitalists to Meet in Vegas

Medical professionals from across the country will attend the first national meeting on the topic of specialty hospitalists Nov. 4 at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Sponsored by SHM, the American Hospital Association, the Neurohospitalist Society, and OBGynHospitalist.com, the gathering is for anyone interested in adopting a hospital-focused model of practice, including physician and nonphysician clinicians, as well as those in medical support industries, such as insurance carriers, policymakers, and healthcare media.

According to organizers, the one-day meeting will be structured to encourage networking and exchange of ideas among attendees, and will include presentations, panel discussions, and Q&A sessions.

"This is less 'Come hear from people who have this all figured out' … it's 'Come hear from people who are thinking about this a lot.' But the attendees are a big part of the knowledge base," says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist medical director at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash.

Dr. Nelson, cofounder and past president of SHM as well as the Nov. 4 meeting director, says he hopes to bring together healthcare leaders from diverse backgrounds to share their experiences and insights. Since this movement is growing organically rather than descending from a central agency, organizers expect to centralize the sharing of ideas and best practices.

Nearly 60 interested parties have pre-registered for the meeting, according to SHM. Attendees will take what they have learned back to their own hospitals or businesses, Dr. Nelson says, and continue the conversation with their colleagues.

The cost to attend the meeting is $350 and seats remain available; register by phone, 800-843-3360, or via the SHM website.

Medical professionals from across the country will attend the first national meeting on the topic of specialty hospitalists Nov. 4 at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Sponsored by SHM, the American Hospital Association, the Neurohospitalist Society, and OBGynHospitalist.com, the gathering is for anyone interested in adopting a hospital-focused model of practice, including physician and nonphysician clinicians, as well as those in medical support industries, such as insurance carriers, policymakers, and healthcare media.

According to organizers, the one-day meeting will be structured to encourage networking and exchange of ideas among attendees, and will include presentations, panel discussions, and Q&A sessions.

"This is less 'Come hear from people who have this all figured out' … it's 'Come hear from people who are thinking about this a lot.' But the attendees are a big part of the knowledge base," says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist medical director at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash.

Dr. Nelson, cofounder and past president of SHM as well as the Nov. 4 meeting director, says he hopes to bring together healthcare leaders from diverse backgrounds to share their experiences and insights. Since this movement is growing organically rather than descending from a central agency, organizers expect to centralize the sharing of ideas and best practices.

Nearly 60 interested parties have pre-registered for the meeting, according to SHM. Attendees will take what they have learned back to their own hospitals or businesses, Dr. Nelson says, and continue the conversation with their colleagues.

The cost to attend the meeting is $350 and seats remain available; register by phone, 800-843-3360, or via the SHM website.

Medical professionals from across the country will attend the first national meeting on the topic of specialty hospitalists Nov. 4 at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas. Sponsored by SHM, the American Hospital Association, the Neurohospitalist Society, and OBGynHospitalist.com, the gathering is for anyone interested in adopting a hospital-focused model of practice, including physician and nonphysician clinicians, as well as those in medical support industries, such as insurance carriers, policymakers, and healthcare media.

According to organizers, the one-day meeting will be structured to encourage networking and exchange of ideas among attendees, and will include presentations, panel discussions, and Q&A sessions.

"This is less 'Come hear from people who have this all figured out' … it's 'Come hear from people who are thinking about this a lot.' But the attendees are a big part of the knowledge base," says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist medical director at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash.

Dr. Nelson, cofounder and past president of SHM as well as the Nov. 4 meeting director, says he hopes to bring together healthcare leaders from diverse backgrounds to share their experiences and insights. Since this movement is growing organically rather than descending from a central agency, organizers expect to centralize the sharing of ideas and best practices.

Nearly 60 interested parties have pre-registered for the meeting, according to SHM. Attendees will take what they have learned back to their own hospitals or businesses, Dr. Nelson says, and continue the conversation with their colleagues.

The cost to attend the meeting is $350 and seats remain available; register by phone, 800-843-3360, or via the SHM website.

Mortality Among Elders With Pneumonia

Pneumonia occurs more commonly among older persons.1 With advancing age, the frequency of hospitalizations and mortality for pneumonia are higher.2 Among the tools developed to predict short‐term mortality is the pneumonia severity index (PSI), which is the best known among severity of illness indices for pneumonia.3 Its ability to predict short‐term mortality for CAP, particularly in identifying those at low risk was previously demonstrated.4 More recently, the extension of its utility in predicting 30‐day mortality for healthcare‐associated pneumonia (HCAP) was demonstrated.5

Severity of illness is one of several risk factors for adverse outcomes among older persons with acute illness. Besides comorbidity, other factors include functional impairment and atypical presentation. Information on physical functioning had equal importance as laboratory data in prognostication of in‐hospital mortality.6 In addition, walking impairment was 1 of 5 components of a risk adjustment index developed to predict 1‐year mortality for hospitalized older persons.7 Atypical presentations of illness, such as delirium and falls, independently predicted poor outcomes among hospitalized older patients.8

Specifically for pneumonia, functional status has also been shown to be an independent predictor of short‐term mortality among older patients hospitalized with CAP.913 Among atypical presentations, only absence of chills was an independent prognostic factor for CAP.9 Bacteremia was an independent factor related to death among adults with CAP, albeit for severe disease resulting in intensive care unit admission.14 It was also included in a severity assessment score; its higher scores were associated with early mortality.15 However, blood culture results are only available 2 to 3 days into the hospital episode. Therefore, bacteremia is a potential risk factor for mortality that is not identifiable at the start of hospitalization.

While PSI is a comprehensive collection of demographic, clinical, and investigative measures, it does not include items on functional status or atypical presentation. Neither does it account for recent hospitalization or comorbid conditions of significance to older persons, such as dementia and depression. It is plausible that at least some of these factors hold added prognostic value.

With all these in mind, we conducted a study with the following objectives: 1) to determine whether functional impairment, recent hospitalization, comorbid conditions of particular significance with advancing age, and atypical presentation are significantly associated with short‐term mortality among older patients hospitalized for CAP and HCAP, after taking into account PSI; and 2) if so, to estimate the magnitude of increased mortality risk with these factors. We tested our null hypotheses that, after adjustment for PSI class, 1) recent hospitalization, 2) pre‐morbid functional impairment, 3) dementia and depression, and 4) atypical presentation of illness have no association with 30‐day mortality for older persons hospitalized for CAP and HCAP, both combined and alone.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design and Setting

This was a retrospective cohort study that employed secondary analyses of chart and administrative data. The setting was 3 acute care public hospitals of the National Healthcare Group (NHG) cluster in Singapore. We merged data from hospital charts, the NHG Operations Data Store administrative database, and the national death registry. The local Institution Review Board (IRB) approved waiver of consent, and all other study procedures were consistent with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Patient Population

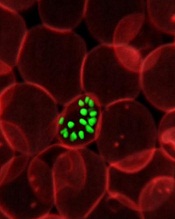

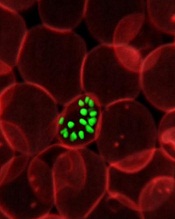

We included first hospital episodes of adults aged 65 years or older with the principal diagnosis of pneumonia in 2007. These episodes were identified by their primary International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes of 480 to 486 in the administrative data. Next, we applied our study definition of pneumonia, which required the presence of acute symptoms or signs of pneumonia at the point of hospital admission, and a chest radiograph with features consistent with pneumonia that was obtained during the period from 24 hours before, to 48 hours after, hospital admission. In doing so, we included patients with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP)16 and healthcare‐associated pneumonia (HCAP),17 but not hospital‐acquired pneumonia (HAP). We excluded patients whose charts were not accessible for review because of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and those whose charts were unavailable for other reasons. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

We assigned the diagnosis of HCAP to patients who were admitted to an acute care hospital for 2 or more days in the prior 90 days, resided in a nursing home or long‐term care facility, or received of intravenous antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, wound care, or hemodialysis in the prior 30 days.18 Remaining patients were assigned CAP.

Data Collection

Trained research nurses used an abstraction protocol to collect demographic and clinical information from the charts, and to extract laboratory results and chest radiograph reports from the computerized clinical records. Where radiological reports were equivocal with respect to features of pneumonia, we obtained the opinion of one of our respiratory physician investigators whose decision was final. A researcher with bio‐informatics expertise extracted admission‐related information from the administrative data. Chart, administrative, and mortality data were merged to assemble the study database.

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

The outcome (dependent) variable was 30‐day all‐cause mortality. The following explanatory (independent) variables were examined:

Pneumonia severity index (PSI): We used PSI class as specified in the original studies.4

Recent hospitalization: Hospitalization in the prior 90 days and 30 days were explored.

Atypical presentation of illness: Acute geriatric syndromes (falls or acute impairment of mobility), and absence of cough and purulent sputum were examined. Delirium was not one of the syndromes because PSI includes altered mental state as an item.4

Functional impairment: Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment were examined. Impairment was defined as needing assistance or being totally dependent.

Additional comorbid conditions: We selected dementia and depression, as they may have impact on mortality in older persons but were not included in PSI.

We did not include bacteremia, because its presence cannot be determined at the time of illness presentation.

From previous experience, we anticipated missing values for functional status measures in up to 5% of charts. Where values were missing, we used the simple imputation strategy of assigning no ambulation or feeding impairment.

Sample Size Calculation

With a sample size of 1400 patients and a 30‐day mortality rate of 25%, 350 cases of death were expected. Using the rule of thumb of at least 10 cases per independent variable,19 we were able to work with 35 candidate explanatory variables in logistic regression for the entire group. Assuming that the subpopulations of CAP and HCAP consist of 700 patients each, with mortality rates of 20% and 30%, respectively, then 14 could be explored for CAP and 21 candidate variables for HCAP.

Data Analyses

Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment probably represent different points along the continuum of functional impairment. During preliminary analyses when both variables were adjusted for each other in logistic regression, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment (odds ratio [OR] 4.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.79 to 6.43) was associated with 30‐day mortality, whereas pre‐morbid feeding impairment was not (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.09). As such, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment was selected as the variable to represent functional impairment. Hospitalization in the prior 30 days was more strongly associated with 30‐day mortality (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.77 to 3.21) than was hospitalization in the prior 90 days (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.41). Therefore, hospitalization in the prior 30 days was selected as the variable to reflect recent hospitalization.

We used logistic regression analysis and regressed 30‐day mortality on PSI class and other explanatory variables. OR estimates and their 95% CI were used to quantify the strength of associations of the explanatory variables with mortality, and to test their statistical significance. In addition, we explored the possibility of interactions between PSI class and the patient factors. To this end, we constructed additional regression models that included appropriate interaction terms and tested their statistical significance. As a form of sensitivity analysis, we repeated the regression analyses only for hospital episodes with complete functional data and observed the extent to which OR estimates changed. Furthermore, we performed 2‐level hierarchical modeling to account for clustering at the hospital level and re‐examined the OR and 95% CI for the patient factors. We conducted these analyses for the entire group, and repeated them separately for CAP and HCAP. Finally, to estimate the extent to which the patient factors would increase predicted 30‐day mortality, we performed marginal effects analyses for the entire group to quantify the increased risk when individual factors were present.

We used STATA version 9.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses. Hierarchical modeling was performed using the xtlogit command. STATA post‐estimation commands mfx and prvalue were employed to estimate marginal effects and predicted probabilities, respectively. The unit of analysis was patients. Statistical significance was defined by P values of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Among 1607 patients included, 890 (55.4%) had CAP and 717 (44.6%) had HCAP. Baseline patient characteristics of patients with CAP and HCAP are shown in Table 1. The 30‐day mortality rate was 28.1% for the entire group, and 20.6% and 37.4% for patients with CAP and HCAP, respectively. When stratified according to PSI classes 2, 3, 4, and 5, this rate was 0%, 8.2%, 24.4%, and 56.0%, respectively. Because there were no deaths among those with PSI class 2, this category was merged with class 3 for the regression analyses. Missing data on pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment occurred for 39 (2.4%) and 69 (4.6%) patients, respectively.

| Whole Study Population (n = 1607) | Those With CAP (n = 890) | Those With HCAP (n = 717) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 80 (7487) | 79 (7385) | 82 (7588) |

| Male, n (%) | 876 (54.5) | 477 (53.6) | 399 (55.7) |

| Median pneumonia severity index (PSI) score, (IQR) | 109 (87134) | 100 (82121) | 120 (99144) |

| PSI class: | |||

| 2 | 98 (6.1) | 84 (9.4) | 14 (2.0) |

| 3 | 353 (22.0) | 260 (29.2) | 93 (13.0) |

| 4 | 713 (44.4) | 386 (43.4) | 327 (45.6) |

| 5 | 443 (27.6) | 160 (18.0) | 283 (39.5) |

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, n (%) | 798 (49.7) | 287 (32.3) | 511 (71.3) |

| Pre‐morbid feeding impairment, n (%) | 298 (18.5) | 74 (8.3) | 224 (31.2) |

| Hospitalization in prior 30 days, n (%) | 209 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 209 (29.2) |

| Nursing home residence, n (%) | 362 (22.5) | 0 (0) | 362 (50.5) |

| Acute geriatric syndromes, n (%) | 442 (27.5) | 241 (27.1) | 201 (28.0) |

| Absence of both cough and purulent sputum, n (%) | 559 (34.8) | 226 (25.4) | 333 (46.4) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 307 (19.1) | 121 (13.6) | 178 (25.8) |

| Depression, n (%) | 165 (10.3) | 53 (6.0) | 109 (15.8) |

| Neoplastic disease, n (%) | 108 (6.7) | 33 (3.7) | 75 (10.5) |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 48 (3.0) | 25 (2.8) | 23 (3.2) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 257 (16.0) | 129 (14.5) | 128 (17.9) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 490 (30.5) | 215 (24.2) | 275 (38.4) |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 220 (13.7) | 97 (10.9) | 123 (17.2) |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 316 (19.7) | 177 (19.9) | 139 (19.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 515 (32.1) | 273 (30.7) | 242 (33.8) |

| Emergency department diagnosis of pneumonia, n (%) | 857 (53.3) | 494 (55.5) | 363 (50.6) |

For CAP and HCAP together, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment was associated with increased 30‐day mortality (339/798 [42.5%] vs 112/809 [13.8%], unadjusted OR 4.60, 95% CI 3.60 to 5.87, P < 0.01), as was hospitalization in the prior 30 days (94/209 [45.0%] vs 357/1398 [25.5%], unadjusted OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.77 to 3.21, P = 0.02). This was also the case for dementia (118/307 [38.4%] vs 333/1300 [25.6%], unadjusted OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.35, P < 0.01), acute geriatric syndromes (163/442 [36.9%] vs 288/1165 [24.7%], unadjusted OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.25, P < 0.01), and absence of cough and purulent sputum (226/559 [40.4%] vs 225/1048 [21.5%], unadjusted OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.98 to 3.11, P < 0.01). However, depression was not significantly associated with 30‐day mortality (57/165 [34.6%] vs 394/1442 [27.3%], unadjusted OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.97, P = 0.05).

Table 2 summarizes the results of logistic regression. It shows that pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, hospitalization in the prior 30 days, and absence of cough and purulent sputum were all independently associated with 30‐day mortality after adjustment for PSI score for the entire group. These associations remained statistically significant when CAP and HCAP were examined separately. Because none of those with CAP could have hospitalization in the prior 30 days, this factor was not included in the CAP model. The strength of association for the same patient factor varied across the pneumonia sub‐type. This was markedly so for pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, with the OR estimate being almost 3‐fold higher for CAP than for HCAP. Dementia, depression, and acute geriatric syndromes were not associated with 30‐day mortality. When the analyses were repeated after excluding hospital episodes with missing values for pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, the same 3 variables were significantly associated with 30‐day mortality, with trivial differences in strength of association compared to when imputation was performed. The OR estimates for pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, hospitalization in the prior 30 days, and absence of cough and purulent sputum were 2.82 (95% CI 2.12 to 3.76), 1.83 (95% CI 1.42 to 2.83), and 1.47 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.91).

| Baseline Patient Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n = 1607) | Patients With CAP (n = 890) | Patients With HCAP (n = 717) | |

| |||

| Pneumonia severity index (PSI) class (reference: PSI classes 2 and 3 combined): | |||

| 4 | 3.37* (2.20 to 5.17) | 4.02* (2.29 to 7.08) | 2.69* (1.38 to 5.26) |

| 5 | 11.19* (7.14 to 17.55) | 13.03* (7.00 to 24.24) | 9.73* (4.86 to 19.46) |

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment | 2.61* (1.98 to 3.45) | 4.56* (3.06 to 6.78) | 1.60* (1.06 to 2.42) |

| Hospitalization in the prior 30 days | 1.93* (1.38 to 2.71) | 2.13* (1.47 to 3.09) | |

| Dementia | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.37) | 0.82 (0.49 to 1.38) | 1.15 (0.78 to 1.69) |

| Depression | 0.83 (0.56 to 1.23) | 1.03 (0.48 to 2.18) | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.31) |

| Acute geriatric syndromes | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.26) | 1.26 (0.83 to 1.92) | 0.74 (0.50 to 1.08) |

| Absence of cough and purulent sputum | 1.47* (1.14 to 1.90) | 1.64* (1.08 to 2.46) | 1.45* (1.04 to 2.03) |

Two‐level hierarchical modeling to account for clustering at the hospital level obtained negligible change in OR estimates of the patient factors and their 95% CI. There were no statistically significant interactions between PSI class and the 3 patient factors (results not shown).

The model‐predicted increase in mortality risk with presence of individual patient factors for the entire group is shown in Table 3. Across the 3 factors, 30‐day mortality increased by 1.9% to 6.1% for those with PSI class 2 and 3, and by 9.0% to 23.2% for those with PSI class 5. The upper end of these ranges represented the effect of pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, while the lower end was that for absence of cough and purulent sputum. With reference to the predicted mortality rates for PSI class which are listed in the footnotes of Table 3, the adverse prognosis conferred by individual patient factors amounted to relative risk inflation of 27% to 145% depending on the specific factor and PSI class.

| Predicted Increase in 30‐Day Mortality With Presence of Single Baseline Patient Factors, % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PSI Classes 2 and 3 (n = 449) | PSI Class 4 (n = 700) | PSI Class 5 (n = 413) | |

| |||

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment | 6.1 (3.2 to 9.0) | 15.0 (10.2 to 19.7) | 23.2 (16.8 to 29.7) |

| Hospitalization in the prior 30 days | 3.6 (0.9 to 6.3) | 9.3 (3.6 to 15.1) | 15.7 (7.3 to 24.2) |

| Absence of cough and purulent sputum | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4) | 5.0 (1.4 to 8.6) | 9.0 (3.0 to 15.0) |

DISCUSSION

After accounting for PSI class, we found 3 additional patient factors that were independently associated with 30‐day mortality among older persons hospitalized for pneumonia. Firstly, our study confirms that impaired physical function reflected by pre‐morbid ambulation impairment increases mortality risk, as previously demonstrated by Torres et al.10 It is likely that impaired function reflects an underlying vulnerability for adverse outcomes that is seen across primary diagnoses.7 Secondly, recent hospitalization often indicates clinical, functional, and social complexities, as well as increased likelihood of infection by more virulent organisms commonly associated with healthcare‐related infections. Together, these 2 factors could increase mortality risk. Thirdly, atypical presentations may be associated with increased mortality, because these often occur in frail older persons who are vulnerable to adverse outcomes8 due to diseases suffered and treatment received. Atypical presentations may also result in delayed diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia.

Pilotto et al. found that a multidimensional index comprising functional status, comorbidity burden, mental status, and nutritional assessment, among others, had a higher predictive accuracy for 30‐day mortality than did PSI.20 While there was a previous attempt to combine PSI with independent predictors to identify low‐risk older patients with CAP,21 we could not find similar work on the range of patient factors examined in this study. Indeed, the most important contribution that our study brings to the growing body of literature on short‐term mortality, among older persons hospitalized for pneumonia, is the prognostic importance of these 3 additional patient factors over and above severity of illness measured by PSI. With reference to the baseline predicted risk for different PSI class categories shown in Table 3, we have demonstrated that the predicted increase in mortality risk with the presence of these 3 factors is often not trivial, particularly for those with more severe pneumonia.

These 3 patient factors retained prognostic significance after accounting for PSI class for HCAP. However, only 2 factors were associated with mortality for CAP, because by definition recent hospitalization does not occur. A relevant discussion point is whether CAP and HCAP should be grouped together or classified separately. It is pertinent to reflect that the utility of making a distinction between CAP and HCAP appears to lie largely in the domain of therapeutics regarding the initial choice of antibiotics,18, 2225 although there has been some debate on this point.26 Moreover, the major features of HCAP, namely recent hospitalization (albeit in the prior 30 days, rather than 90 days) and nursing home residence (an item in PSI) were included in our regression analyses. Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider CAP and HCAP as a single group for risk stratification at the clinical frontline. We also argue that combining CAP and HCAP for risk adjustment will result in larger sample sizes that can minimize uncertainty around treatment effect estimates, when comparing across different interventions or providers. The same approach of analyzing CAP and HCAP together was adopted in a recent study that compared US hospitals on their risk‐adjusted performance for pneumonia among Medicare beneficiaries.27

The 30‐day mortality rates in this study are higher than those in the original PSI studies, even when stratified according to PSI class. However, more recent studies also registered relatively high mortality rates ranging from 18% to 19%.12, 28 There are a number of possible reasons for the higher mortality rates observed in our study. Firstly, we included both CAP and HCAP, whereas some other studies focused only on CAP. Secondly, the original PSI studies excluded patients with previous hospitalization within 7 days of admission, while we included them. Thirdly, our study population was relatively old (median age: 80 years) and had a higher proportion from nursing homes (22%). Although age and nursing home residence are variables in the PSI, the weights assigned to these 2 items may not adequately reflect the magnitude of mortality risk they confer. Finally, our understanding is that the study population comprises a relatively high proportion of patients who have do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) instructions, though this was not measured. All these patient characteristics are likely to be associated with higher mortality risk.

The major strength of this study relates to its real world setting, where there were no major exclusion criteria except for HIV/AIDS. In addition, the clinical data at our disposal allowed selection from a relatively wide range of patient factors, beyond that commonly available in administrative data alone.

However, a few important limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the study restricted data to those routinely collected, rather than that specifically acquired for research. Important unmeasured factors include inflammatory markers such as C‐reactive protein (CRP) or procalcitonin levels which have been shown to have prognostic value.29 Others include frailty, socioeconomic status, and social support.20 Secondly, increased likelihood of measurement error associated with retrospectively collected data could result in bias with uncertain direction. Thirdly, our strategy of assuming no functional impairment in the absence of documentation raises the possibility of underidentification and consequent bias in the direction of underestimation of the strength of association between pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and mortality. If so, the true association could even be stronger. Finally, we did not capture do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) decisions because these were not consistently documented in the charts. We concede that DNR status is expected to be associated with short‐term mortality30 and therefore remains an unobserved factor that may explain a proportion of the mortality risk attributed to other factors in our study, such as pre‐morbid ambulation impairment.

Where do we proceed from here? Given our findings, further work that examines the unmeasured factors mentioned should be done. CRP and procalcitonin levels can be extracted from the laboratory results database when they are measured. However, specification of the other 3 factors is more challenging, given that these represent clinical or social constructs wherein optimal measurement is less certain. It would be important to estimate how much these factors improve the prediction of short‐term mortality beyond that achieved by PSI and the patient factors we have identified.

Nonetheless, the clinical implications of our work are clear. While PSI class is a time‐tested tool, addition of pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, hospitalization in the prior 30 days, and absence of cough and purulent sputum can further improve risk stratification for short‐term mortality, when older persons present initially with clinical and radiological features of pneumonia. Information on these factors should be available in routine clinical care and, therefore, their use in risk stratification should be considered. For more valid and credible risk adjustment, these 3 factors could be considered in addition to severity of illness indices where data availability permits.

CONCLUSION

Recent hospitalization, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, and atypical clinical presentation were independently associated with higher 30‐day mortality among older persons hospitalized for pneumonia, after adjusting for severity of illness with PSI class. These factors could be considered in addition to PSI, when performing risk stratification and adjustment in this setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Clinical Associate Professor Sin Fai Lam for his assistance in the study, and the medical board chairmen of the 3 study hospitals for their support and encouragement.

- .Community‐acquired pneumonia in the elderly.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:1066–1078.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalized community‐acquired pneumonia in the elderly—age‐ and sex‐related patterns of care and outcome in the United States.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2002;165:766–772.

- ,,,,.Validation of a pneumonia prognostic index using the MedisGroups Comparative Hospital Database.Am J Med.1993;94:153–159.

- ,,, et al.A prediction rule to identify low‐risk patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.N Engl J Med.1997;336:243–250.

- ,,, et al.Application and comparison of scoring indices to predict outcomes in patients with healthcare‐associated pneumonia.Critical Care.2011;15:R32.

- ,,,,,.Predicting in‐hospital mortality: the importance of functional status information.Med Care.1995;33:906–921.

- ,,, et al.Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments.Med Care.2003;41:70–83.

- ,,,,.Illness presentation in elderly patients.Arch Intern Med.1995;155:1060–1064.

- ,,, et al.Community‐acquired pneumonia in the elderly: Spanish multicentre study.Eur Respir J.2003;21:294–302.

- ,,, et al.Outcome predictors of pneumonia in elderly patients: importance of functional assessment.J Am Geriatr Soc.2004;52:1603–1609.

- ,.Factors influencing in‐hospital mortality in community‐acquired pneumonia: a prospective study of patients not initially admitted to the ICU.Chest.2005;127;1260–1270.

- ,,.Assessment of pneumonia in older adults: effect of functional status.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006;54:1062–1067.

- ,,, et al.Only severely limited, premorbid functional status is associated with short‐ and longterm mortality in patients with pneumonia who are critically ill: a prospective observational study.Chest.2011;139:88–94.

- ,,, et al.Severe community‐acquired pneumonia: assessment of microbial aetiology as mortality factor.Eur Respir J.2004;24:779–785.

- ,,,,,.PIRO score for community‐acquired pneumonia: a new prediction rule for assessment of severity in intensive care unit patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.Crit Care Med.2009;37:456–462.

- ,,,,,.Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:347–382.

- ,,,,,.Epidemiology and outcomes of health‐care–associated pneumonia—results from a large US database of culture‐positive pneumonia.Chest.2005;128:3854–3862.

- American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America.Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital‐acquired, ventilator‐associated, and healthcare‐associated pneumonia.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2005;171:388–416.

- ,,.Conceptual and practical issues in developing risk‐adjustment methods. In: Iezzoni LI, editor.Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes.3rd ed.Chicago, IL:Health Administration Press;2003:179–205.

- ,,, et al.The multidimensional prognostic index predicts short‐ and long‐term mortality in hospitalized geriatric patients with pneumonia.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.2009;64A:880–887.

- ,,, et al.A validation and potential modification of the pneumonia severity index in elderly patients with community‐acquired pneumonia.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006;54:1212–1219.

- ,.Health care‐associated pneumonia—a new therapeutic paradigm.Chest.2005;128:3784–3786.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated pneumonia requiring hospital admission.Arch Intern Med.2007;167:1393–1399.

- ,,, et al.Health care‐associated pneumonia (HCAP): a critical appraisal to improve identification, management, and outcomes—Proceedings of the HCAP Summit.Clin Infect Dis.2008;46(suppl 4):S296–S334.

- ,,,,;for the Study Group of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine.Outcomes of patients hospitalized with community‐acquired, health care‐associated, and hospital‐acquired pneumonia.Ann Intern Med.2009;150:19–26.

- ,.Healthcare‐associated pneumonia is a heterogeneous disease, and all patients do not need the same broad‐spectrum antibiotic therapy as complex nosocomial pneumonia.Curr Opin Infect Dis.2009;22:316–325.

- ,,, et al.The performance of US hospitals as reflected in risk‐standardized 30‐day mortality and readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries with pneumonia.J Hosp Med.2010;5:E12–E18.

- ,,, et al.Temporal trends in outcomes of older patients with pneumonia.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3385–3391.

- ,.Clinical review: the role of biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of community‐acquired pneumonia.Critical Care.2010;14:203.

- ,,, et al.Community‐acquired pneumonia and do‐not‐resuscitate orders.J Am Geriatr Soc.2002;50:290–299.

Pneumonia occurs more commonly among older persons.1 With advancing age, the frequency of hospitalizations and mortality for pneumonia are higher.2 Among the tools developed to predict short‐term mortality is the pneumonia severity index (PSI), which is the best known among severity of illness indices for pneumonia.3 Its ability to predict short‐term mortality for CAP, particularly in identifying those at low risk was previously demonstrated.4 More recently, the extension of its utility in predicting 30‐day mortality for healthcare‐associated pneumonia (HCAP) was demonstrated.5

Severity of illness is one of several risk factors for adverse outcomes among older persons with acute illness. Besides comorbidity, other factors include functional impairment and atypical presentation. Information on physical functioning had equal importance as laboratory data in prognostication of in‐hospital mortality.6 In addition, walking impairment was 1 of 5 components of a risk adjustment index developed to predict 1‐year mortality for hospitalized older persons.7 Atypical presentations of illness, such as delirium and falls, independently predicted poor outcomes among hospitalized older patients.8

Specifically for pneumonia, functional status has also been shown to be an independent predictor of short‐term mortality among older patients hospitalized with CAP.913 Among atypical presentations, only absence of chills was an independent prognostic factor for CAP.9 Bacteremia was an independent factor related to death among adults with CAP, albeit for severe disease resulting in intensive care unit admission.14 It was also included in a severity assessment score; its higher scores were associated with early mortality.15 However, blood culture results are only available 2 to 3 days into the hospital episode. Therefore, bacteremia is a potential risk factor for mortality that is not identifiable at the start of hospitalization.

While PSI is a comprehensive collection of demographic, clinical, and investigative measures, it does not include items on functional status or atypical presentation. Neither does it account for recent hospitalization or comorbid conditions of significance to older persons, such as dementia and depression. It is plausible that at least some of these factors hold added prognostic value.

With all these in mind, we conducted a study with the following objectives: 1) to determine whether functional impairment, recent hospitalization, comorbid conditions of particular significance with advancing age, and atypical presentation are significantly associated with short‐term mortality among older patients hospitalized for CAP and HCAP, after taking into account PSI; and 2) if so, to estimate the magnitude of increased mortality risk with these factors. We tested our null hypotheses that, after adjustment for PSI class, 1) recent hospitalization, 2) pre‐morbid functional impairment, 3) dementia and depression, and 4) atypical presentation of illness have no association with 30‐day mortality for older persons hospitalized for CAP and HCAP, both combined and alone.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design and Setting

This was a retrospective cohort study that employed secondary analyses of chart and administrative data. The setting was 3 acute care public hospitals of the National Healthcare Group (NHG) cluster in Singapore. We merged data from hospital charts, the NHG Operations Data Store administrative database, and the national death registry. The local Institution Review Board (IRB) approved waiver of consent, and all other study procedures were consistent with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Patient Population

We included first hospital episodes of adults aged 65 years or older with the principal diagnosis of pneumonia in 2007. These episodes were identified by their primary International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes of 480 to 486 in the administrative data. Next, we applied our study definition of pneumonia, which required the presence of acute symptoms or signs of pneumonia at the point of hospital admission, and a chest radiograph with features consistent with pneumonia that was obtained during the period from 24 hours before, to 48 hours after, hospital admission. In doing so, we included patients with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP)16 and healthcare‐associated pneumonia (HCAP),17 but not hospital‐acquired pneumonia (HAP). We excluded patients whose charts were not accessible for review because of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and those whose charts were unavailable for other reasons. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

We assigned the diagnosis of HCAP to patients who were admitted to an acute care hospital for 2 or more days in the prior 90 days, resided in a nursing home or long‐term care facility, or received of intravenous antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, wound care, or hemodialysis in the prior 30 days.18 Remaining patients were assigned CAP.

Data Collection

Trained research nurses used an abstraction protocol to collect demographic and clinical information from the charts, and to extract laboratory results and chest radiograph reports from the computerized clinical records. Where radiological reports were equivocal with respect to features of pneumonia, we obtained the opinion of one of our respiratory physician investigators whose decision was final. A researcher with bio‐informatics expertise extracted admission‐related information from the administrative data. Chart, administrative, and mortality data were merged to assemble the study database.

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

The outcome (dependent) variable was 30‐day all‐cause mortality. The following explanatory (independent) variables were examined:

Pneumonia severity index (PSI): We used PSI class as specified in the original studies.4

Recent hospitalization: Hospitalization in the prior 90 days and 30 days were explored.

Atypical presentation of illness: Acute geriatric syndromes (falls or acute impairment of mobility), and absence of cough and purulent sputum were examined. Delirium was not one of the syndromes because PSI includes altered mental state as an item.4

Functional impairment: Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment were examined. Impairment was defined as needing assistance or being totally dependent.

Additional comorbid conditions: We selected dementia and depression, as they may have impact on mortality in older persons but were not included in PSI.

We did not include bacteremia, because its presence cannot be determined at the time of illness presentation.

From previous experience, we anticipated missing values for functional status measures in up to 5% of charts. Where values were missing, we used the simple imputation strategy of assigning no ambulation or feeding impairment.

Sample Size Calculation

With a sample size of 1400 patients and a 30‐day mortality rate of 25%, 350 cases of death were expected. Using the rule of thumb of at least 10 cases per independent variable,19 we were able to work with 35 candidate explanatory variables in logistic regression for the entire group. Assuming that the subpopulations of CAP and HCAP consist of 700 patients each, with mortality rates of 20% and 30%, respectively, then 14 could be explored for CAP and 21 candidate variables for HCAP.

Data Analyses

Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment probably represent different points along the continuum of functional impairment. During preliminary analyses when both variables were adjusted for each other in logistic regression, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment (odds ratio [OR] 4.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.79 to 6.43) was associated with 30‐day mortality, whereas pre‐morbid feeding impairment was not (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.09). As such, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment was selected as the variable to represent functional impairment. Hospitalization in the prior 30 days was more strongly associated with 30‐day mortality (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.77 to 3.21) than was hospitalization in the prior 90 days (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.41). Therefore, hospitalization in the prior 30 days was selected as the variable to reflect recent hospitalization.

We used logistic regression analysis and regressed 30‐day mortality on PSI class and other explanatory variables. OR estimates and their 95% CI were used to quantify the strength of associations of the explanatory variables with mortality, and to test their statistical significance. In addition, we explored the possibility of interactions between PSI class and the patient factors. To this end, we constructed additional regression models that included appropriate interaction terms and tested their statistical significance. As a form of sensitivity analysis, we repeated the regression analyses only for hospital episodes with complete functional data and observed the extent to which OR estimates changed. Furthermore, we performed 2‐level hierarchical modeling to account for clustering at the hospital level and re‐examined the OR and 95% CI for the patient factors. We conducted these analyses for the entire group, and repeated them separately for CAP and HCAP. Finally, to estimate the extent to which the patient factors would increase predicted 30‐day mortality, we performed marginal effects analyses for the entire group to quantify the increased risk when individual factors were present.

We used STATA version 9.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses. Hierarchical modeling was performed using the xtlogit command. STATA post‐estimation commands mfx and prvalue were employed to estimate marginal effects and predicted probabilities, respectively. The unit of analysis was patients. Statistical significance was defined by P values of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Among 1607 patients included, 890 (55.4%) had CAP and 717 (44.6%) had HCAP. Baseline patient characteristics of patients with CAP and HCAP are shown in Table 1. The 30‐day mortality rate was 28.1% for the entire group, and 20.6% and 37.4% for patients with CAP and HCAP, respectively. When stratified according to PSI classes 2, 3, 4, and 5, this rate was 0%, 8.2%, 24.4%, and 56.0%, respectively. Because there were no deaths among those with PSI class 2, this category was merged with class 3 for the regression analyses. Missing data on pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment occurred for 39 (2.4%) and 69 (4.6%) patients, respectively.

| Whole Study Population (n = 1607) | Those With CAP (n = 890) | Those With HCAP (n = 717) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 80 (7487) | 79 (7385) | 82 (7588) |

| Male, n (%) | 876 (54.5) | 477 (53.6) | 399 (55.7) |

| Median pneumonia severity index (PSI) score, (IQR) | 109 (87134) | 100 (82121) | 120 (99144) |

| PSI class: | |||

| 2 | 98 (6.1) | 84 (9.4) | 14 (2.0) |

| 3 | 353 (22.0) | 260 (29.2) | 93 (13.0) |

| 4 | 713 (44.4) | 386 (43.4) | 327 (45.6) |

| 5 | 443 (27.6) | 160 (18.0) | 283 (39.5) |

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, n (%) | 798 (49.7) | 287 (32.3) | 511 (71.3) |

| Pre‐morbid feeding impairment, n (%) | 298 (18.5) | 74 (8.3) | 224 (31.2) |

| Hospitalization in prior 30 days, n (%) | 209 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 209 (29.2) |

| Nursing home residence, n (%) | 362 (22.5) | 0 (0) | 362 (50.5) |

| Acute geriatric syndromes, n (%) | 442 (27.5) | 241 (27.1) | 201 (28.0) |

| Absence of both cough and purulent sputum, n (%) | 559 (34.8) | 226 (25.4) | 333 (46.4) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 307 (19.1) | 121 (13.6) | 178 (25.8) |

| Depression, n (%) | 165 (10.3) | 53 (6.0) | 109 (15.8) |

| Neoplastic disease, n (%) | 108 (6.7) | 33 (3.7) | 75 (10.5) |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 48 (3.0) | 25 (2.8) | 23 (3.2) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 257 (16.0) | 129 (14.5) | 128 (17.9) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 490 (30.5) | 215 (24.2) | 275 (38.4) |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 220 (13.7) | 97 (10.9) | 123 (17.2) |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 316 (19.7) | 177 (19.9) | 139 (19.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 515 (32.1) | 273 (30.7) | 242 (33.8) |

| Emergency department diagnosis of pneumonia, n (%) | 857 (53.3) | 494 (55.5) | 363 (50.6) |

For CAP and HCAP together, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment was associated with increased 30‐day mortality (339/798 [42.5%] vs 112/809 [13.8%], unadjusted OR 4.60, 95% CI 3.60 to 5.87, P < 0.01), as was hospitalization in the prior 30 days (94/209 [45.0%] vs 357/1398 [25.5%], unadjusted OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.77 to 3.21, P = 0.02). This was also the case for dementia (118/307 [38.4%] vs 333/1300 [25.6%], unadjusted OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.35, P < 0.01), acute geriatric syndromes (163/442 [36.9%] vs 288/1165 [24.7%], unadjusted OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.25, P < 0.01), and absence of cough and purulent sputum (226/559 [40.4%] vs 225/1048 [21.5%], unadjusted OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.98 to 3.11, P < 0.01). However, depression was not significantly associated with 30‐day mortality (57/165 [34.6%] vs 394/1442 [27.3%], unadjusted OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.97, P = 0.05).

Table 2 summarizes the results of logistic regression. It shows that pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, hospitalization in the prior 30 days, and absence of cough and purulent sputum were all independently associated with 30‐day mortality after adjustment for PSI score for the entire group. These associations remained statistically significant when CAP and HCAP were examined separately. Because none of those with CAP could have hospitalization in the prior 30 days, this factor was not included in the CAP model. The strength of association for the same patient factor varied across the pneumonia sub‐type. This was markedly so for pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, with the OR estimate being almost 3‐fold higher for CAP than for HCAP. Dementia, depression, and acute geriatric syndromes were not associated with 30‐day mortality. When the analyses were repeated after excluding hospital episodes with missing values for pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, the same 3 variables were significantly associated with 30‐day mortality, with trivial differences in strength of association compared to when imputation was performed. The OR estimates for pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, hospitalization in the prior 30 days, and absence of cough and purulent sputum were 2.82 (95% CI 2.12 to 3.76), 1.83 (95% CI 1.42 to 2.83), and 1.47 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.91).

| Baseline Patient Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n = 1607) | Patients With CAP (n = 890) | Patients With HCAP (n = 717) | |

| |||

| Pneumonia severity index (PSI) class (reference: PSI classes 2 and 3 combined): | |||

| 4 | 3.37* (2.20 to 5.17) | 4.02* (2.29 to 7.08) | 2.69* (1.38 to 5.26) |

| 5 | 11.19* (7.14 to 17.55) | 13.03* (7.00 to 24.24) | 9.73* (4.86 to 19.46) |

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment | 2.61* (1.98 to 3.45) | 4.56* (3.06 to 6.78) | 1.60* (1.06 to 2.42) |

| Hospitalization in the prior 30 days | 1.93* (1.38 to 2.71) | 2.13* (1.47 to 3.09) | |

| Dementia | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.37) | 0.82 (0.49 to 1.38) | 1.15 (0.78 to 1.69) |

| Depression | 0.83 (0.56 to 1.23) | 1.03 (0.48 to 2.18) | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.31) |

| Acute geriatric syndromes | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.26) | 1.26 (0.83 to 1.92) | 0.74 (0.50 to 1.08) |

| Absence of cough and purulent sputum | 1.47* (1.14 to 1.90) | 1.64* (1.08 to 2.46) | 1.45* (1.04 to 2.03) |

Two‐level hierarchical modeling to account for clustering at the hospital level obtained negligible change in OR estimates of the patient factors and their 95% CI. There were no statistically significant interactions between PSI class and the 3 patient factors (results not shown).

The model‐predicted increase in mortality risk with presence of individual patient factors for the entire group is shown in Table 3. Across the 3 factors, 30‐day mortality increased by 1.9% to 6.1% for those with PSI class 2 and 3, and by 9.0% to 23.2% for those with PSI class 5. The upper end of these ranges represented the effect of pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, while the lower end was that for absence of cough and purulent sputum. With reference to the predicted mortality rates for PSI class which are listed in the footnotes of Table 3, the adverse prognosis conferred by individual patient factors amounted to relative risk inflation of 27% to 145% depending on the specific factor and PSI class.

| Predicted Increase in 30‐Day Mortality With Presence of Single Baseline Patient Factors, % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PSI Classes 2 and 3 (n = 449) | PSI Class 4 (n = 700) | PSI Class 5 (n = 413) | |

| |||

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment | 6.1 (3.2 to 9.0) | 15.0 (10.2 to 19.7) | 23.2 (16.8 to 29.7) |

| Hospitalization in the prior 30 days | 3.6 (0.9 to 6.3) | 9.3 (3.6 to 15.1) | 15.7 (7.3 to 24.2) |

| Absence of cough and purulent sputum | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4) | 5.0 (1.4 to 8.6) | 9.0 (3.0 to 15.0) |

DISCUSSION

After accounting for PSI class, we found 3 additional patient factors that were independently associated with 30‐day mortality among older persons hospitalized for pneumonia. Firstly, our study confirms that impaired physical function reflected by pre‐morbid ambulation impairment increases mortality risk, as previously demonstrated by Torres et al.10 It is likely that impaired function reflects an underlying vulnerability for adverse outcomes that is seen across primary diagnoses.7 Secondly, recent hospitalization often indicates clinical, functional, and social complexities, as well as increased likelihood of infection by more virulent organisms commonly associated with healthcare‐related infections. Together, these 2 factors could increase mortality risk. Thirdly, atypical presentations may be associated with increased mortality, because these often occur in frail older persons who are vulnerable to adverse outcomes8 due to diseases suffered and treatment received. Atypical presentations may also result in delayed diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia.

Pilotto et al. found that a multidimensional index comprising functional status, comorbidity burden, mental status, and nutritional assessment, among others, had a higher predictive accuracy for 30‐day mortality than did PSI.20 While there was a previous attempt to combine PSI with independent predictors to identify low‐risk older patients with CAP,21 we could not find similar work on the range of patient factors examined in this study. Indeed, the most important contribution that our study brings to the growing body of literature on short‐term mortality, among older persons hospitalized for pneumonia, is the prognostic importance of these 3 additional patient factors over and above severity of illness measured by PSI. With reference to the baseline predicted risk for different PSI class categories shown in Table 3, we have demonstrated that the predicted increase in mortality risk with the presence of these 3 factors is often not trivial, particularly for those with more severe pneumonia.

These 3 patient factors retained prognostic significance after accounting for PSI class for HCAP. However, only 2 factors were associated with mortality for CAP, because by definition recent hospitalization does not occur. A relevant discussion point is whether CAP and HCAP should be grouped together or classified separately. It is pertinent to reflect that the utility of making a distinction between CAP and HCAP appears to lie largely in the domain of therapeutics regarding the initial choice of antibiotics,18, 2225 although there has been some debate on this point.26 Moreover, the major features of HCAP, namely recent hospitalization (albeit in the prior 30 days, rather than 90 days) and nursing home residence (an item in PSI) were included in our regression analyses. Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider CAP and HCAP as a single group for risk stratification at the clinical frontline. We also argue that combining CAP and HCAP for risk adjustment will result in larger sample sizes that can minimize uncertainty around treatment effect estimates, when comparing across different interventions or providers. The same approach of analyzing CAP and HCAP together was adopted in a recent study that compared US hospitals on their risk‐adjusted performance for pneumonia among Medicare beneficiaries.27

The 30‐day mortality rates in this study are higher than those in the original PSI studies, even when stratified according to PSI class. However, more recent studies also registered relatively high mortality rates ranging from 18% to 19%.12, 28 There are a number of possible reasons for the higher mortality rates observed in our study. Firstly, we included both CAP and HCAP, whereas some other studies focused only on CAP. Secondly, the original PSI studies excluded patients with previous hospitalization within 7 days of admission, while we included them. Thirdly, our study population was relatively old (median age: 80 years) and had a higher proportion from nursing homes (22%). Although age and nursing home residence are variables in the PSI, the weights assigned to these 2 items may not adequately reflect the magnitude of mortality risk they confer. Finally, our understanding is that the study population comprises a relatively high proportion of patients who have do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) instructions, though this was not measured. All these patient characteristics are likely to be associated with higher mortality risk.

The major strength of this study relates to its real world setting, where there were no major exclusion criteria except for HIV/AIDS. In addition, the clinical data at our disposal allowed selection from a relatively wide range of patient factors, beyond that commonly available in administrative data alone.

However, a few important limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the study restricted data to those routinely collected, rather than that specifically acquired for research. Important unmeasured factors include inflammatory markers such as C‐reactive protein (CRP) or procalcitonin levels which have been shown to have prognostic value.29 Others include frailty, socioeconomic status, and social support.20 Secondly, increased likelihood of measurement error associated with retrospectively collected data could result in bias with uncertain direction. Thirdly, our strategy of assuming no functional impairment in the absence of documentation raises the possibility of underidentification and consequent bias in the direction of underestimation of the strength of association between pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and mortality. If so, the true association could even be stronger. Finally, we did not capture do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) decisions because these were not consistently documented in the charts. We concede that DNR status is expected to be associated with short‐term mortality30 and therefore remains an unobserved factor that may explain a proportion of the mortality risk attributed to other factors in our study, such as pre‐morbid ambulation impairment.

Where do we proceed from here? Given our findings, further work that examines the unmeasured factors mentioned should be done. CRP and procalcitonin levels can be extracted from the laboratory results database when they are measured. However, specification of the other 3 factors is more challenging, given that these represent clinical or social constructs wherein optimal measurement is less certain. It would be important to estimate how much these factors improve the prediction of short‐term mortality beyond that achieved by PSI and the patient factors we have identified.

Nonetheless, the clinical implications of our work are clear. While PSI class is a time‐tested tool, addition of pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, hospitalization in the prior 30 days, and absence of cough and purulent sputum can further improve risk stratification for short‐term mortality, when older persons present initially with clinical and radiological features of pneumonia. Information on these factors should be available in routine clinical care and, therefore, their use in risk stratification should be considered. For more valid and credible risk adjustment, these 3 factors could be considered in addition to severity of illness indices where data availability permits.

CONCLUSION

Recent hospitalization, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, and atypical clinical presentation were independently associated with higher 30‐day mortality among older persons hospitalized for pneumonia, after adjusting for severity of illness with PSI class. These factors could be considered in addition to PSI, when performing risk stratification and adjustment in this setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Clinical Associate Professor Sin Fai Lam for his assistance in the study, and the medical board chairmen of the 3 study hospitals for their support and encouragement.

Pneumonia occurs more commonly among older persons.1 With advancing age, the frequency of hospitalizations and mortality for pneumonia are higher.2 Among the tools developed to predict short‐term mortality is the pneumonia severity index (PSI), which is the best known among severity of illness indices for pneumonia.3 Its ability to predict short‐term mortality for CAP, particularly in identifying those at low risk was previously demonstrated.4 More recently, the extension of its utility in predicting 30‐day mortality for healthcare‐associated pneumonia (HCAP) was demonstrated.5

Severity of illness is one of several risk factors for adverse outcomes among older persons with acute illness. Besides comorbidity, other factors include functional impairment and atypical presentation. Information on physical functioning had equal importance as laboratory data in prognostication of in‐hospital mortality.6 In addition, walking impairment was 1 of 5 components of a risk adjustment index developed to predict 1‐year mortality for hospitalized older persons.7 Atypical presentations of illness, such as delirium and falls, independently predicted poor outcomes among hospitalized older patients.8

Specifically for pneumonia, functional status has also been shown to be an independent predictor of short‐term mortality among older patients hospitalized with CAP.913 Among atypical presentations, only absence of chills was an independent prognostic factor for CAP.9 Bacteremia was an independent factor related to death among adults with CAP, albeit for severe disease resulting in intensive care unit admission.14 It was also included in a severity assessment score; its higher scores were associated with early mortality.15 However, blood culture results are only available 2 to 3 days into the hospital episode. Therefore, bacteremia is a potential risk factor for mortality that is not identifiable at the start of hospitalization.

While PSI is a comprehensive collection of demographic, clinical, and investigative measures, it does not include items on functional status or atypical presentation. Neither does it account for recent hospitalization or comorbid conditions of significance to older persons, such as dementia and depression. It is plausible that at least some of these factors hold added prognostic value.

With all these in mind, we conducted a study with the following objectives: 1) to determine whether functional impairment, recent hospitalization, comorbid conditions of particular significance with advancing age, and atypical presentation are significantly associated with short‐term mortality among older patients hospitalized for CAP and HCAP, after taking into account PSI; and 2) if so, to estimate the magnitude of increased mortality risk with these factors. We tested our null hypotheses that, after adjustment for PSI class, 1) recent hospitalization, 2) pre‐morbid functional impairment, 3) dementia and depression, and 4) atypical presentation of illness have no association with 30‐day mortality for older persons hospitalized for CAP and HCAP, both combined and alone.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design and Setting

This was a retrospective cohort study that employed secondary analyses of chart and administrative data. The setting was 3 acute care public hospitals of the National Healthcare Group (NHG) cluster in Singapore. We merged data from hospital charts, the NHG Operations Data Store administrative database, and the national death registry. The local Institution Review Board (IRB) approved waiver of consent, and all other study procedures were consistent with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Patient Population

We included first hospital episodes of adults aged 65 years or older with the principal diagnosis of pneumonia in 2007. These episodes were identified by their primary International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes of 480 to 486 in the administrative data. Next, we applied our study definition of pneumonia, which required the presence of acute symptoms or signs of pneumonia at the point of hospital admission, and a chest radiograph with features consistent with pneumonia that was obtained during the period from 24 hours before, to 48 hours after, hospital admission. In doing so, we included patients with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP)16 and healthcare‐associated pneumonia (HCAP),17 but not hospital‐acquired pneumonia (HAP). We excluded patients whose charts were not accessible for review because of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and those whose charts were unavailable for other reasons. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

We assigned the diagnosis of HCAP to patients who were admitted to an acute care hospital for 2 or more days in the prior 90 days, resided in a nursing home or long‐term care facility, or received of intravenous antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, wound care, or hemodialysis in the prior 30 days.18 Remaining patients were assigned CAP.

Data Collection

Trained research nurses used an abstraction protocol to collect demographic and clinical information from the charts, and to extract laboratory results and chest radiograph reports from the computerized clinical records. Where radiological reports were equivocal with respect to features of pneumonia, we obtained the opinion of one of our respiratory physician investigators whose decision was final. A researcher with bio‐informatics expertise extracted admission‐related information from the administrative data. Chart, administrative, and mortality data were merged to assemble the study database.

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

The outcome (dependent) variable was 30‐day all‐cause mortality. The following explanatory (independent) variables were examined:

Pneumonia severity index (PSI): We used PSI class as specified in the original studies.4

Recent hospitalization: Hospitalization in the prior 90 days and 30 days were explored.

Atypical presentation of illness: Acute geriatric syndromes (falls or acute impairment of mobility), and absence of cough and purulent sputum were examined. Delirium was not one of the syndromes because PSI includes altered mental state as an item.4

Functional impairment: Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment were examined. Impairment was defined as needing assistance or being totally dependent.

Additional comorbid conditions: We selected dementia and depression, as they may have impact on mortality in older persons but were not included in PSI.

We did not include bacteremia, because its presence cannot be determined at the time of illness presentation.

From previous experience, we anticipated missing values for functional status measures in up to 5% of charts. Where values were missing, we used the simple imputation strategy of assigning no ambulation or feeding impairment.

Sample Size Calculation

With a sample size of 1400 patients and a 30‐day mortality rate of 25%, 350 cases of death were expected. Using the rule of thumb of at least 10 cases per independent variable,19 we were able to work with 35 candidate explanatory variables in logistic regression for the entire group. Assuming that the subpopulations of CAP and HCAP consist of 700 patients each, with mortality rates of 20% and 30%, respectively, then 14 could be explored for CAP and 21 candidate variables for HCAP.

Data Analyses

Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment probably represent different points along the continuum of functional impairment. During preliminary analyses when both variables were adjusted for each other in logistic regression, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment (odds ratio [OR] 4.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.79 to 6.43) was associated with 30‐day mortality, whereas pre‐morbid feeding impairment was not (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.09). As such, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment was selected as the variable to represent functional impairment. Hospitalization in the prior 30 days was more strongly associated with 30‐day mortality (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.77 to 3.21) than was hospitalization in the prior 90 days (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.41). Therefore, hospitalization in the prior 30 days was selected as the variable to reflect recent hospitalization.

We used logistic regression analysis and regressed 30‐day mortality on PSI class and other explanatory variables. OR estimates and their 95% CI were used to quantify the strength of associations of the explanatory variables with mortality, and to test their statistical significance. In addition, we explored the possibility of interactions between PSI class and the patient factors. To this end, we constructed additional regression models that included appropriate interaction terms and tested their statistical significance. As a form of sensitivity analysis, we repeated the regression analyses only for hospital episodes with complete functional data and observed the extent to which OR estimates changed. Furthermore, we performed 2‐level hierarchical modeling to account for clustering at the hospital level and re‐examined the OR and 95% CI for the patient factors. We conducted these analyses for the entire group, and repeated them separately for CAP and HCAP. Finally, to estimate the extent to which the patient factors would increase predicted 30‐day mortality, we performed marginal effects analyses for the entire group to quantify the increased risk when individual factors were present.

We used STATA version 9.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses. Hierarchical modeling was performed using the xtlogit command. STATA post‐estimation commands mfx and prvalue were employed to estimate marginal effects and predicted probabilities, respectively. The unit of analysis was patients. Statistical significance was defined by P values of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Among 1607 patients included, 890 (55.4%) had CAP and 717 (44.6%) had HCAP. Baseline patient characteristics of patients with CAP and HCAP are shown in Table 1. The 30‐day mortality rate was 28.1% for the entire group, and 20.6% and 37.4% for patients with CAP and HCAP, respectively. When stratified according to PSI classes 2, 3, 4, and 5, this rate was 0%, 8.2%, 24.4%, and 56.0%, respectively. Because there were no deaths among those with PSI class 2, this category was merged with class 3 for the regression analyses. Missing data on pre‐morbid ambulation impairment and feeding impairment occurred for 39 (2.4%) and 69 (4.6%) patients, respectively.

| Whole Study Population (n = 1607) | Those With CAP (n = 890) | Those With HCAP (n = 717) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 80 (7487) | 79 (7385) | 82 (7588) |

| Male, n (%) | 876 (54.5) | 477 (53.6) | 399 (55.7) |

| Median pneumonia severity index (PSI) score, (IQR) | 109 (87134) | 100 (82121) | 120 (99144) |

| PSI class: | |||

| 2 | 98 (6.1) | 84 (9.4) | 14 (2.0) |

| 3 | 353 (22.0) | 260 (29.2) | 93 (13.0) |

| 4 | 713 (44.4) | 386 (43.4) | 327 (45.6) |

| 5 | 443 (27.6) | 160 (18.0) | 283 (39.5) |

| Pre‐morbid ambulation impairment, n (%) | 798 (49.7) | 287 (32.3) | 511 (71.3) |

| Pre‐morbid feeding impairment, n (%) | 298 (18.5) | 74 (8.3) | 224 (31.2) |

| Hospitalization in prior 30 days, n (%) | 209 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 209 (29.2) |

| Nursing home residence, n (%) | 362 (22.5) | 0 (0) | 362 (50.5) |

| Acute geriatric syndromes, n (%) | 442 (27.5) | 241 (27.1) | 201 (28.0) |

| Absence of both cough and purulent sputum, n (%) | 559 (34.8) | 226 (25.4) | 333 (46.4) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 307 (19.1) | 121 (13.6) | 178 (25.8) |

| Depression, n (%) | 165 (10.3) | 53 (6.0) | 109 (15.8) |

| Neoplastic disease, n (%) | 108 (6.7) | 33 (3.7) | 75 (10.5) |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 48 (3.0) | 25 (2.8) | 23 (3.2) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 257 (16.0) | 129 (14.5) | 128 (17.9) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 490 (30.5) | 215 (24.2) | 275 (38.4) |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 220 (13.7) | 97 (10.9) | 123 (17.2) |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 316 (19.7) | 177 (19.9) | 139 (19.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 515 (32.1) | 273 (30.7) | 242 (33.8) |

| Emergency department diagnosis of pneumonia, n (%) | 857 (53.3) | 494 (55.5) | 363 (50.6) |

For CAP and HCAP together, pre‐morbid ambulation impairment was associated with increased 30‐day mortality (339/798 [42.5%] vs 112/809 [13.8%], unadjusted OR 4.60, 95% CI 3.60 to 5.87, P < 0.01), as was hospitalization in the prior 30 days (94/209 [45.0%] vs 357/1398 [25.5%], unadjusted OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.77 to 3.21, P = 0.02). This was also the case for dementia (118/307 [38.4%] vs 333/1300 [25.6%], unadjusted OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.35, P < 0.01), acute geriatric syndromes (163/442 [36.9%] vs 288/1165 [24.7%], unadjusted OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.25, P < 0.01), and absence of cough and purulent sputum (226/559 [40.4%] vs 225/1048 [21.5%], unadjusted OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.98 to 3.11, P < 0.01). However, depression was not significantly associated with 30‐day mortality (57/165 [34.6%] vs 394/1442 [27.3%], unadjusted OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.97, P = 0.05).