User login

Cost‐Related Medication Underuse

The affordability of prescription medications continues to be one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States. Many patients reduce their prescribed doses to make medications last longer or do not fill prescriptions because of cost.1 Cost‐related medication underuse affects patients with and without drug insurance coverage,2 and is likely to become even more problematic as employers scale back on drug benefits3 and drug prices continue to increase.4 The landmark Patient Protection and Affordability Act passed in March 2010 does little to address this issue.5

Existing estimates of cost‐related medication underuse come largely from surveys of ambulatory patients. For example, using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Maden et al. estimated that 11% to 15% of patients reduced medication use in the past year because of cost.6 Tseng and colleagues found very similar rates of cost‐related underuse in managed care beneficiaries with diabetes.7

Hospitalized patients, who have a high burden of disease and tend to use more medications than their ambulatory counterparts, may be particularly vulnerable to cost‐related underuse but, thus far, have been subject to little investigation. New medications, which are frequently prescribed at the time of discharge, may exacerbate these issues further and contribute to preventable readmissions. Accordingly, we surveyed a cohort of medical inpatients at a large academic medical center to estimate the prevalence and predictors of cost‐related medication underuse for hospitalized managed care patients, and to identify strategies that patients perceive as helpful to make medications more affordable.

METHODS

Study Sample

We identified consecutive patients newly admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, or oncology services at Brigham and Women's Hospital from November 2008 to December 2009. For our survey, we included only those patients who received medical benefits through 1 of 3 large insurers with whom our hospital has pay‐for‐performance contracts. Annually, there are approximately 4000 patients covered by these insurers admitted to the 3 clinical services we evaluated, We focused on patients who had a primary care physician at one of the hospital's outpatient practices because of the existence of an automated infrastructure to identify these managed care beneficiaries of these insurers who are newly hospitalized, and because patients covered by commercial insurance plans likely represent a conservative lower‐bound of cost‐related medication underuse among hospitalized patients.

Patients were surveyed on the first non‐holiday weekday after admission. We excluded patients who had been discharged prior to the daily admission list being generated, or who, on a previous admission, had completed our survey or declined to be surveyed. We also excluded several patients who were not beneficiaries of the target insurers and were erroneously included on the managed care admission roster.

Potentially eligible patients were approached on the hospital ward by 1 of 3 study care coordinators (2 nurses and 1 pharmacist) and were asked if they were willing to participate in a research project about medication use that involved a short verbally delivered in‐person (inpatient) survey, a brief postdischarge telephone call, and a review of their electronic health record. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women's Hospital approved this study.

Inpatient Survey

Our survey instrument was developed iteratively and pilot‐tested to improve face validity. Questions about cost‐related underuse were based on validated measures.8, 9 Specifically, we asked whether in the past year patients had: (1) not filled a prescription because it was too expensive, (2) skipped doses to make medicines last longer, (3) took less medicine than prescribed to make the medicine last longer, or (4) split pills to make the medication last longer.

Questions about strategies to improve medication affordability assessed whether patients thought it would be helpful to: (1) discuss medication affordability with healthcare workers (inpatient doctors, outpatient doctors, nurses, pharmacists, or social workers); (2) have their medications reviewed by a nurse or pharmacist; (3) receive information about lower cost but equally effective medication options, or about programs that provide medications at reduced costs; and/or (4) have their copayments/coinsurance lowered. Possible responses to all of these questions were binary, ie, yes or no.

In addition, patients were asked about the nature of their drug insurance coverage, the prescription medications that they currently use, whether they know their copayment levels (for generic and brand‐name medications), and, if so, what these amounts were, their annual household income, and their self‐identified race. Information on patient age, gender, and the primary reason for hospitalization was obtained from the electronic health record. This source was also used to verify the accuracy of the self‐reported preadmission medication list. When there were discrepancies between preadmission medications reported by patients and those recorded in their chart, the later was used because our hospital reconciles and records all medications at the time of hospital admission for all patients.

Postdischarge Survey

Within 3 days of discharge, patients were contacted by telephone and asked about new medications they were prescribed on discharge, if any. The discharge summary was used to verify the accuracy of the information provided by patients. The interviewers clarified any apparent discrepancies between the 2 sources of information with the patient. Patients who had been prescribed a new medication were asked whether or not they had filled their prescription. For patients who had, we asked whether: (1) they knew how much they would have to pay prior to going to the pharmacy, (2) they had discussed less expensive options with their pharmacist, and (3) they had discussed medication costs with their inpatient or outpatient physicians.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of our respondents and our overall survey results. We generated univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to identify whether prehospitalization cost‐related medication underuse was influenced by patient age, gender, income, race, and the number of medications patients used on a regular basis. For the purpose of these analyses, we classified patients as reporting cost‐related underuse if they responded yes to any of the 4 strategies described above (ie, not filling medications, skipping doses, taking less medication, or splitting pills to make medicines last longer). Patients whose incomes were above the median level in our cohort were categorized as being of high‐income. Our multivariable model had a c‐statistic of 0.75, suggesting good discriminative ability.

RESULTS

During the study period, 483 potentially‐eligible patients were admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, and oncology services. We excluded 167 because they had been discharged prior to being identified, had been surveyed or already declined participation on a prior admission, or were not managed care enrollees (see Appendix A). Of the remaining 316 subjects, 130 participated in the inpatient survey (response rate = 41%); 93 (75%) of these patients were reached by telephone after hospital discharge and completed the postdischarge survey. The baseline characteristics of our respondents are presented in Table 1. Patients had a mean age of 52 years, were 50% male and two‐thirds of white race, represented a range of household incomes, and almost all had employer‐sponsored prescription coverage. Prior to admission, patients took an average of 5 prescription medications and paid an average copayment of $10.80 and $21.60 for each generic and brand‐name prescription, respectively.

| Characteristic | N = 130 |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 52 (11.2) |

| Male, % | 65 (50.0) |

| Race/ethnicity,* n (%) | |

| Caucasian/white | 84 (67.2) |

| Black/African American | 20 (16.0) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 13 (10.4) |

| Asian | 3 (2.4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.8) |

| Other | 4 (3.2) |

| Annual household income,* n (%) | |

| <$30,000 | 15 (12.8) |

| $30,000‐$75,000 | 49 (41.9) |

| >$75,000 | 53 (45.3) |

| Insurance coverage for outpatient prescription drugs,* n (%) | |

| Employer or spouse's employer | 123 (96.0) |

| Independent | 5 (3.9) |

| Medication copayments,* mean $ (SD) | |

| Brand‐name medications | 21.6 (14.2) |

| Generic medications | 10.8 (6.0) |

| No. of medications prior to admission, mean (SD) | 5.5 (4.3) |

| Category of discharge diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 40 (30.8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 23 (17.7) |

| Pulmonary | 23 (17.7) |

| Infectious | 13 (10.0) |

| Oncology | 5 (3.8) |

| Renal | 6 (4.6) |

| Psychiatric | 3 (2.3) |

| Hematologic | 4 (3.1) |

| Neurologic | 5 (3.8) |

| Musculoskeletal | 5 (3.8) |

| Respiratory | 2 (1.5) |

| Endocrine | 1 (0.8) |

Cost‐Related Medication Underuse

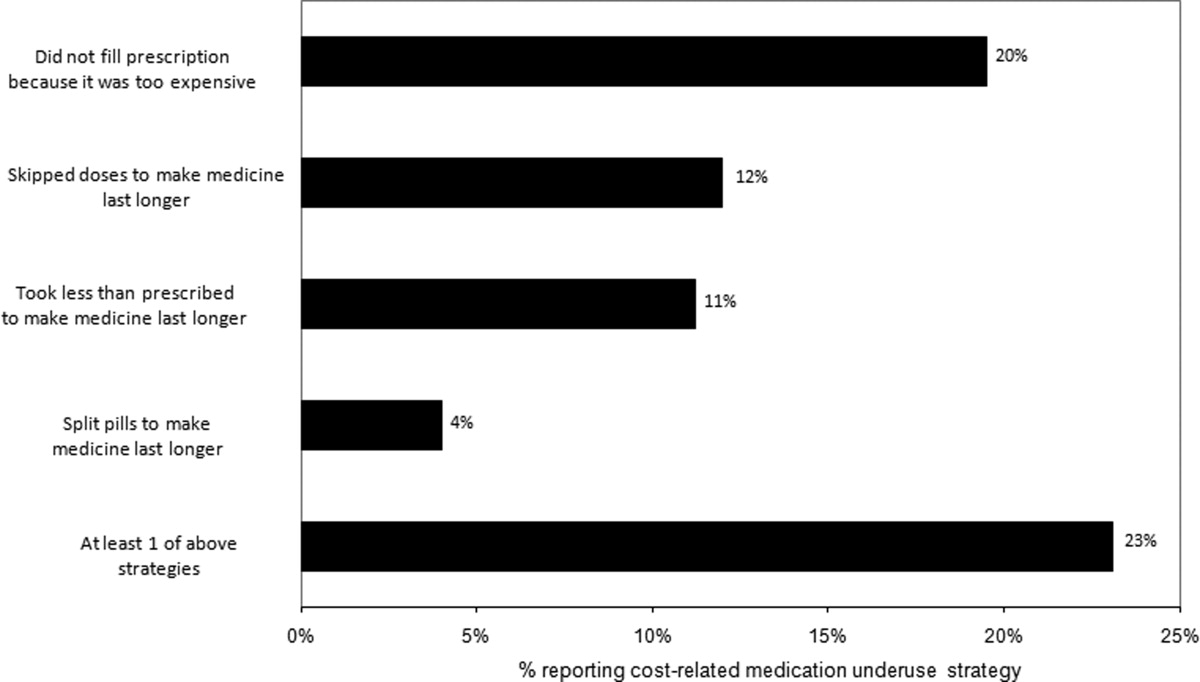

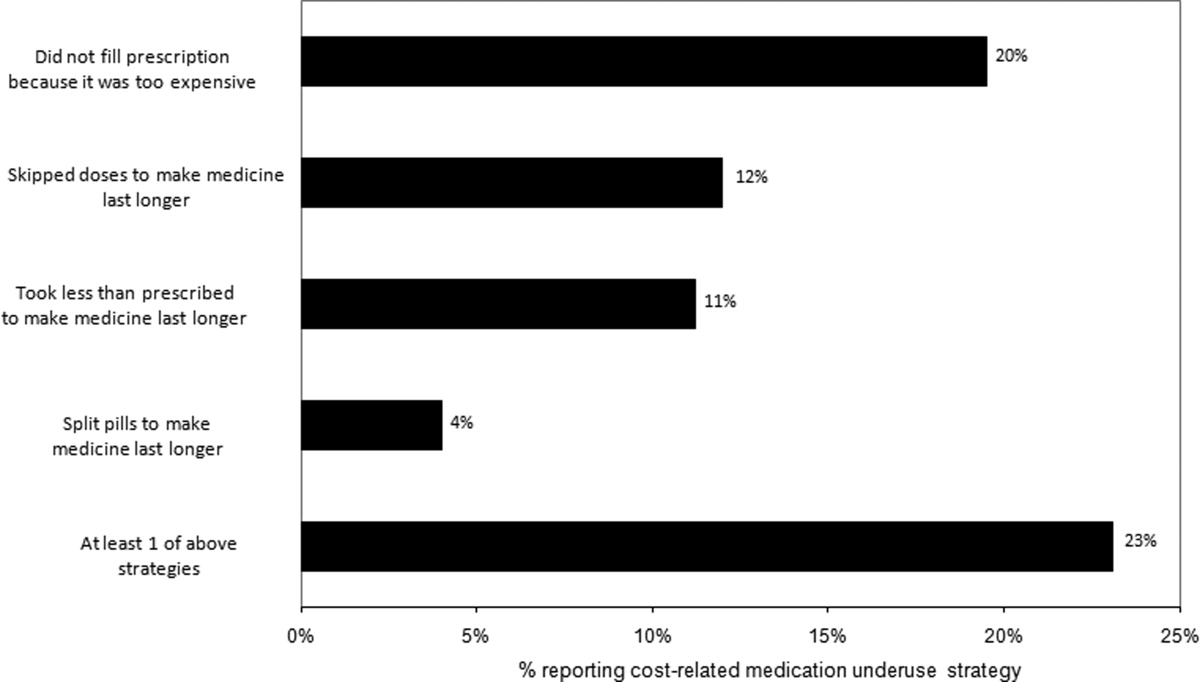

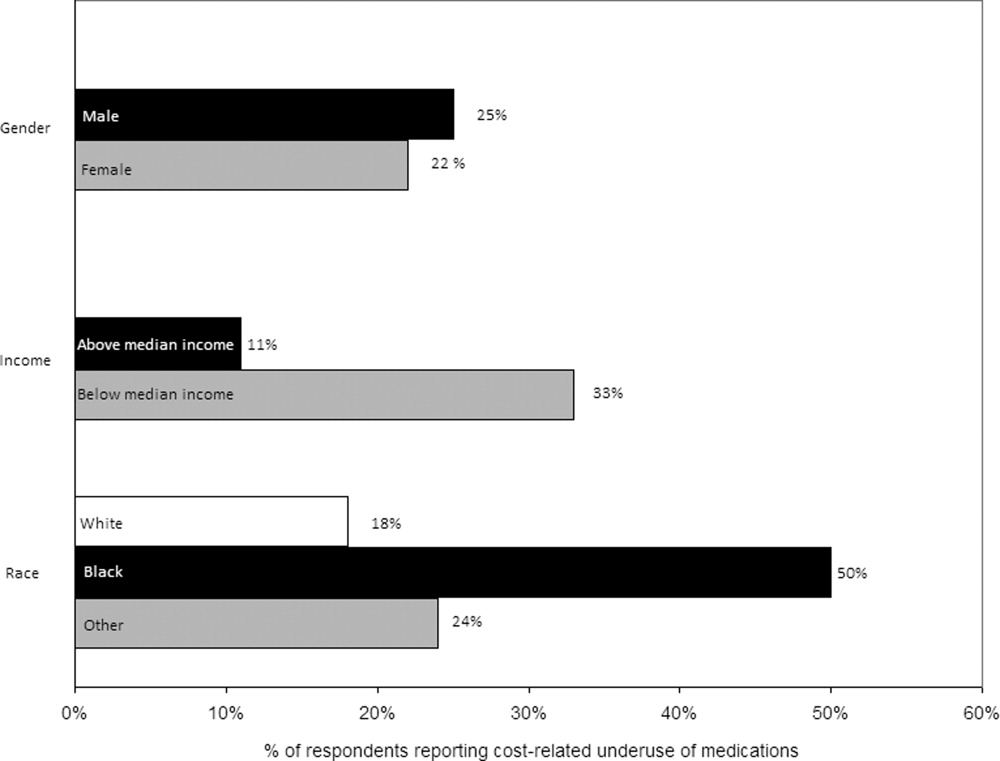

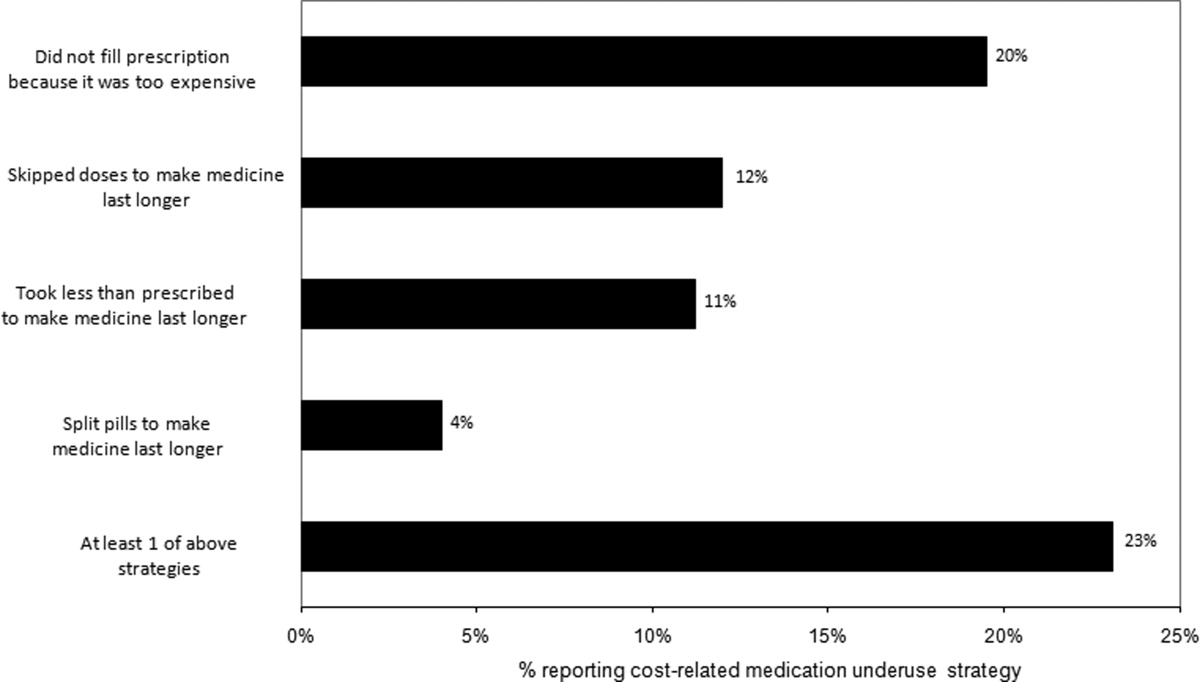

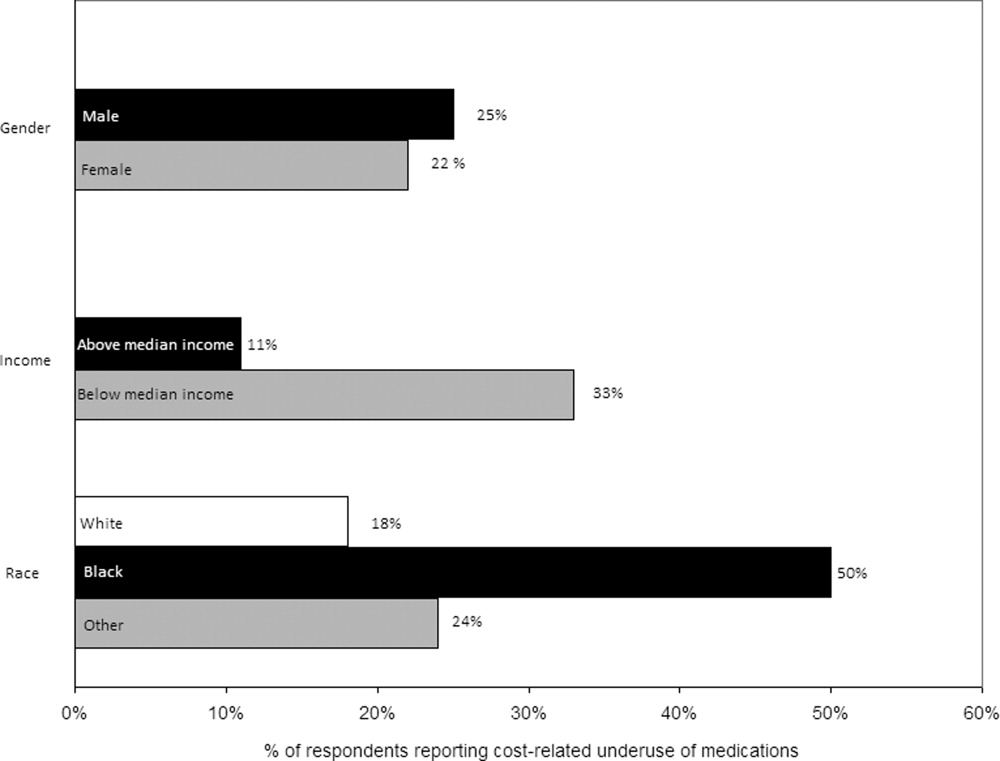

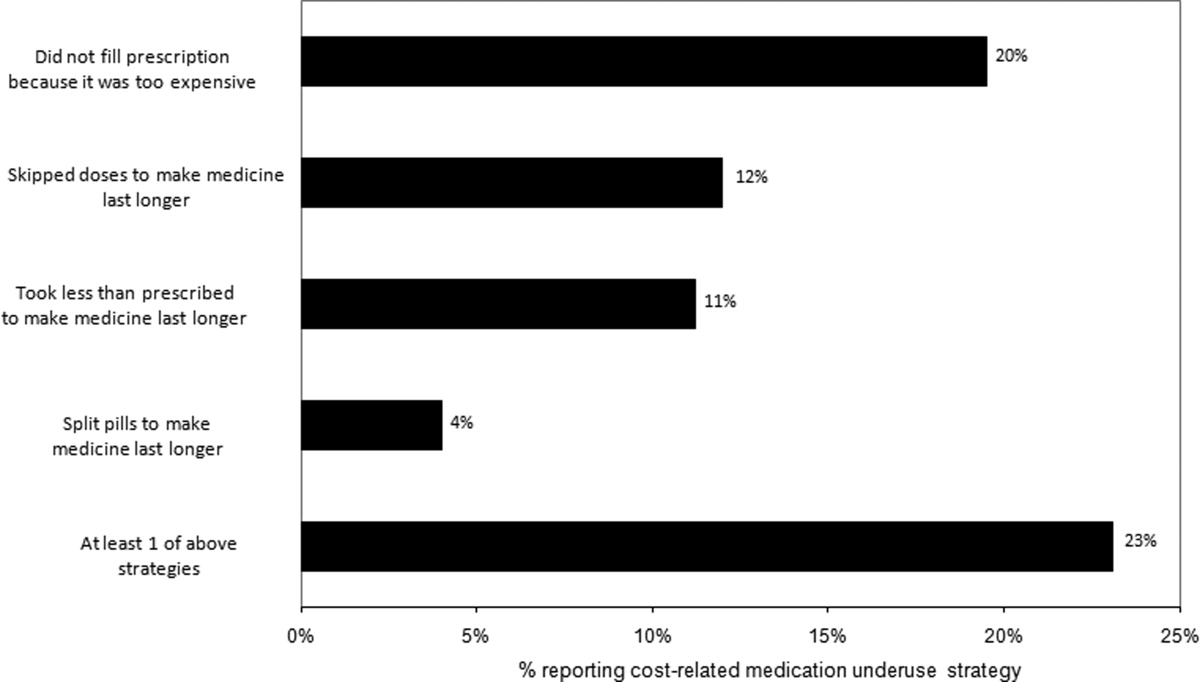

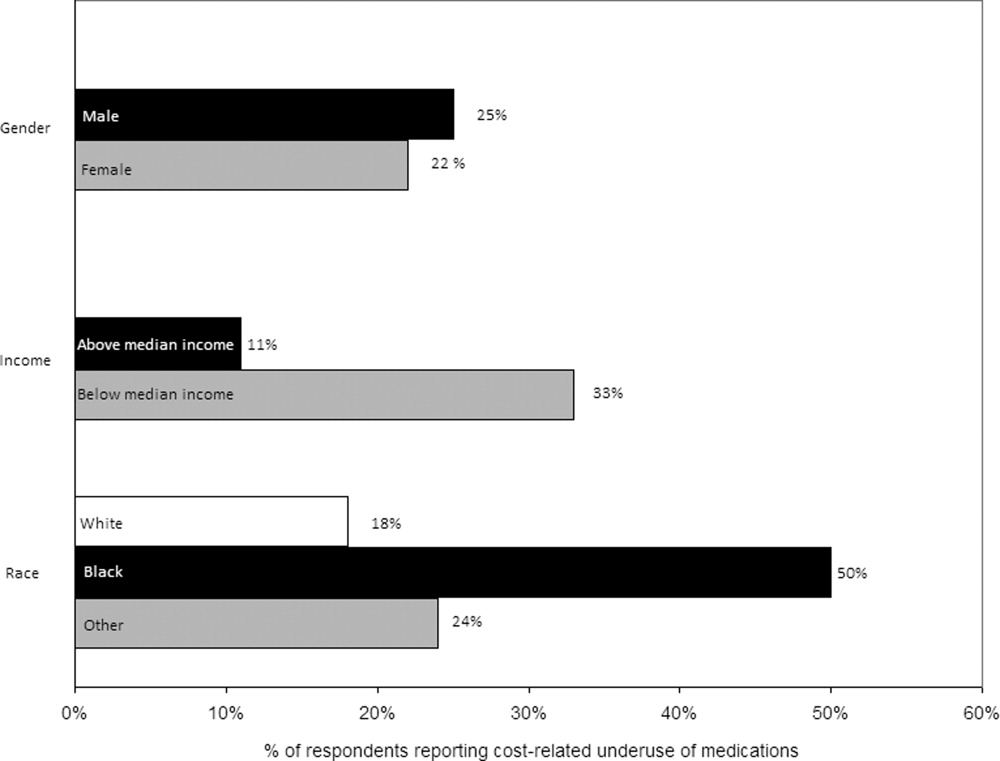

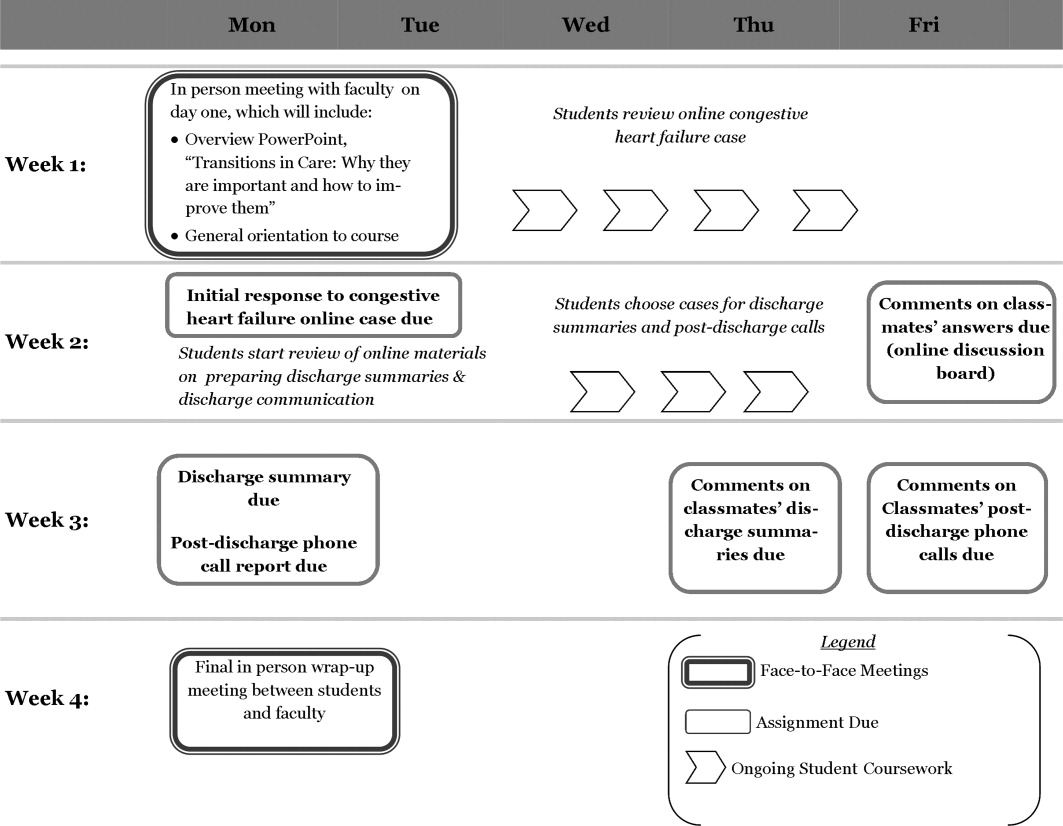

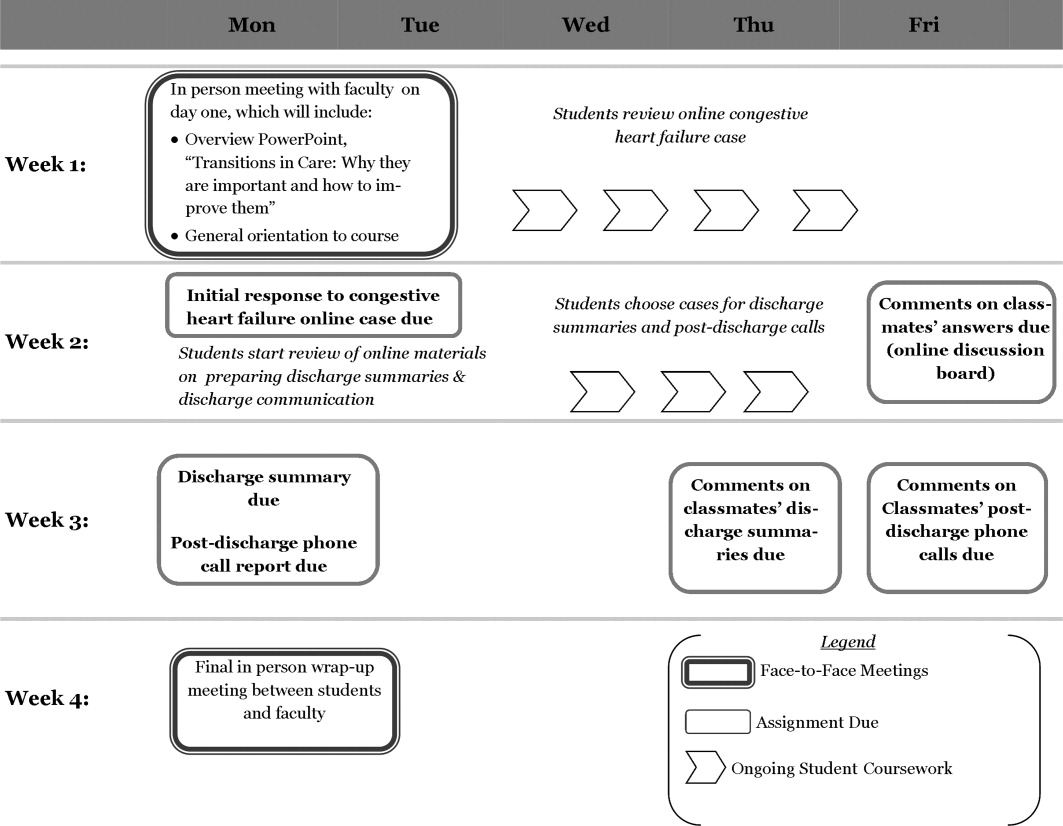

Thirty (23%) of the survey respondents reported at least 1 cost‐related medication underuse strategy in the year prior to their hospital admission (Figure 1), most commonly not filling a prescription at all because of cost (n = 26; 20%). Rates of cost‐related underuse were highest for patients of black race, low income, and women (Figure 2).

In unadjusted analyses, black respondents had 4.60 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.63 to 13.0) times the odds of reporting cost‐related underuse than non‐Hispanic white respondents (Table 2). The association of black race and cost‐related underuse appears to be confounded, in part, by income (adjusted odds ratio for black race was 4.16; 95% CI, 1.34 to 12.86) and the number of medications patients used on a regular basis (adjusted odds ratio for black race was 4.14; 95% CI, 1.44 to 11.96). After controlling for these variables, as well as age and gender, the relationship between race and cost‐related underuse remained statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio 3.39; 95% CI, 1.05 to 11.02) (Table 2).

| Predictor | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age (per additional year) | 0.98 (0.941.02) | 0.97 (0.931.01) |

| Male (vs female) | 0.84 (0.371.90) | 1.03 (0.432.48) |

| Race (vs white race) | ||

| Black | 4.60 (1.6313.0) | 3.39 (1.0511.02) |

| Other | 1.10 (0.363.37) | 0.77 (0.202.99) |

| No. of medications (per additional medication) | 1.10 (1.001.20) | 1.10 (1.001.22) |

| High income (vs low income) | 0.62 (0.271.42) | 0.71 (0.242.07) |

Strategies to Help Make Medications More Affordable

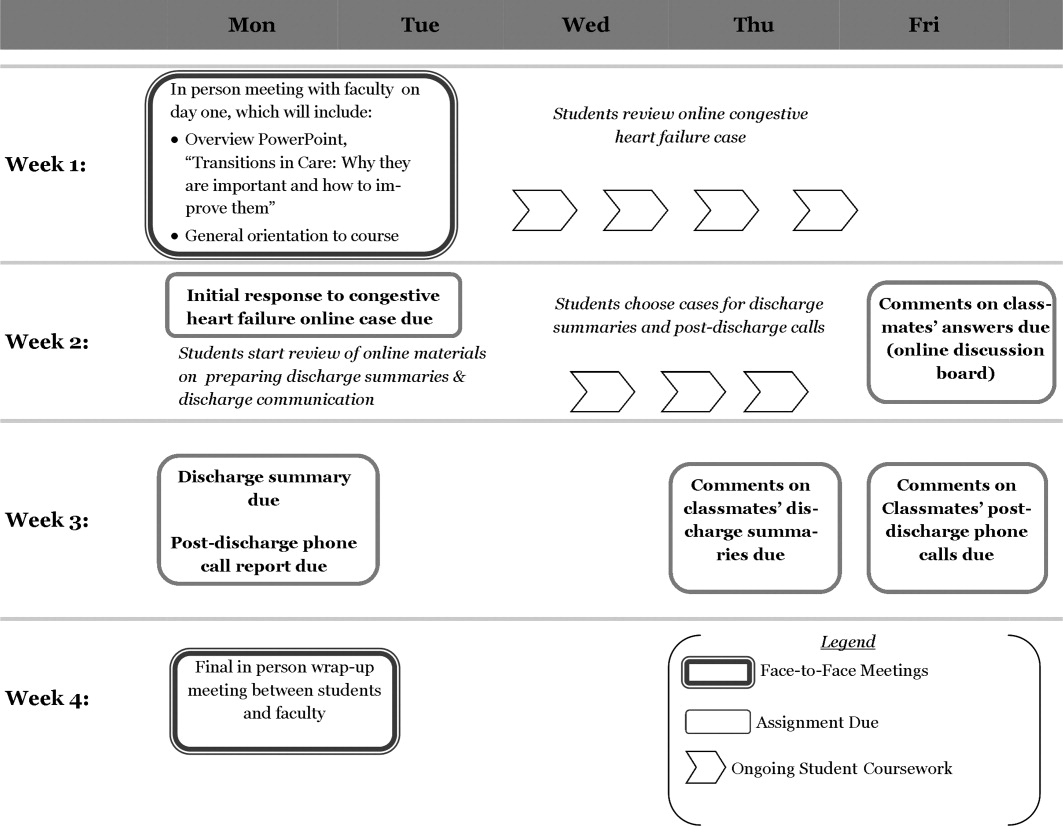

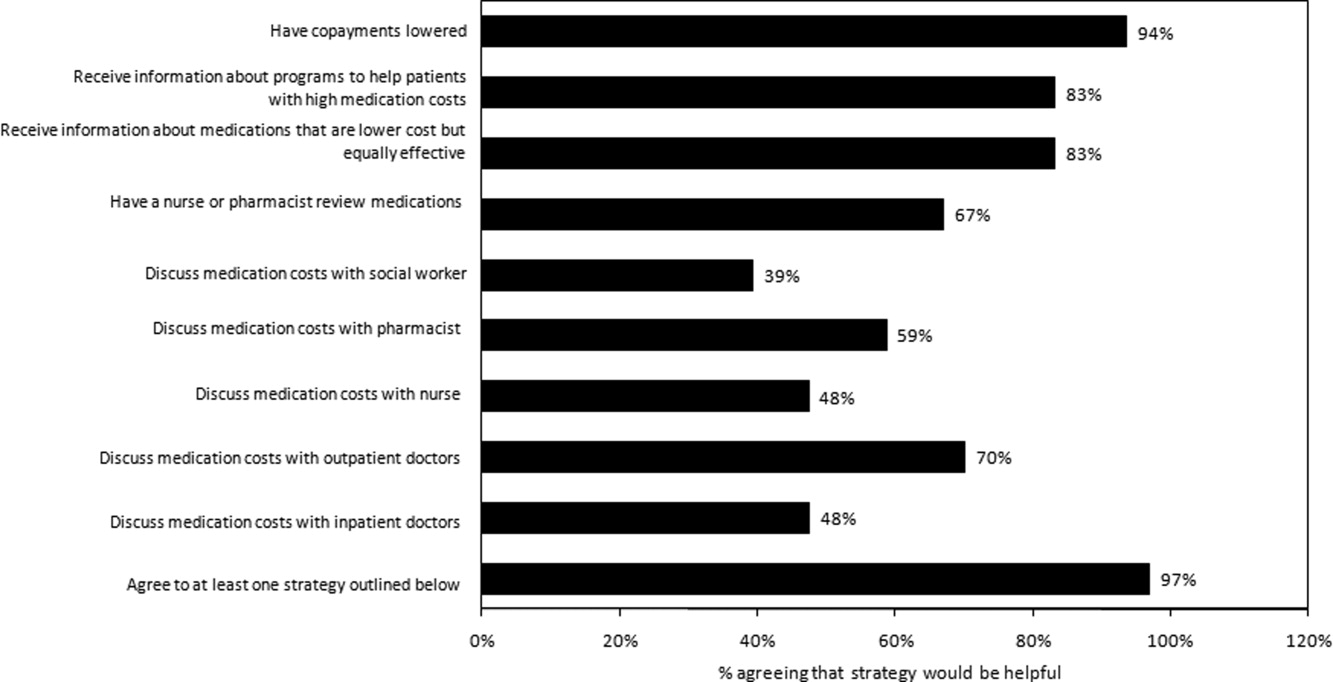

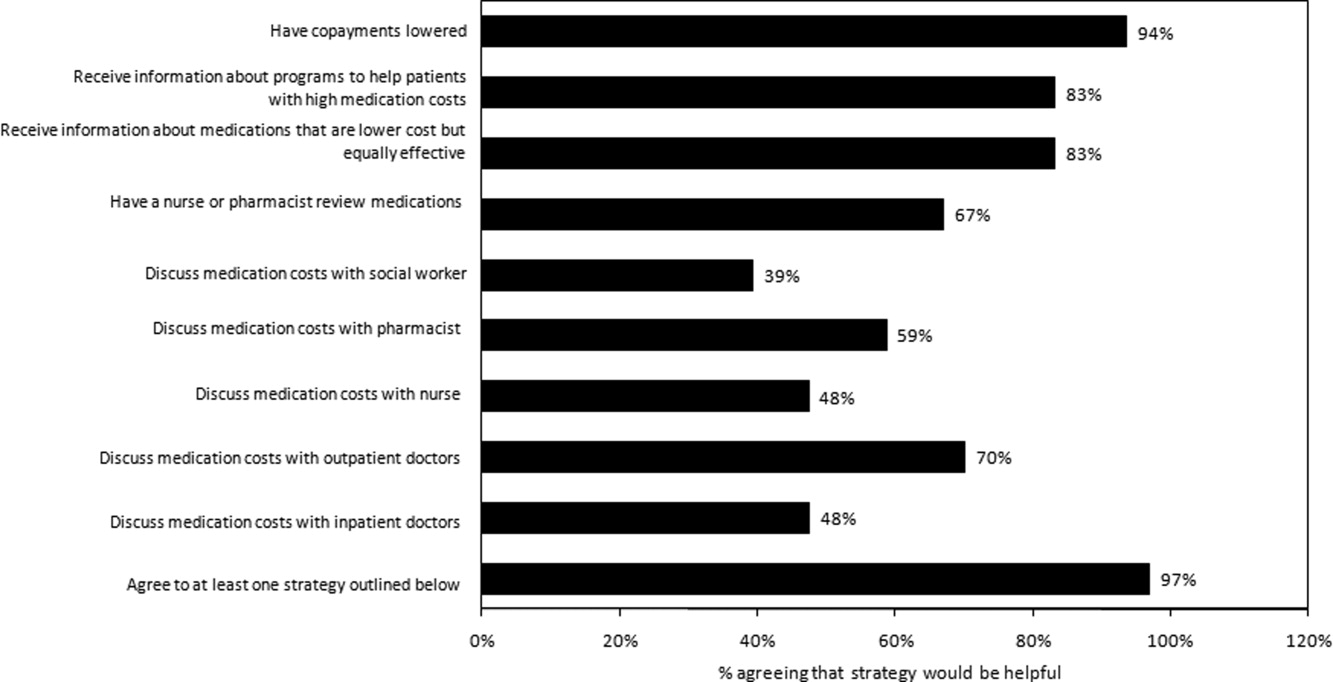

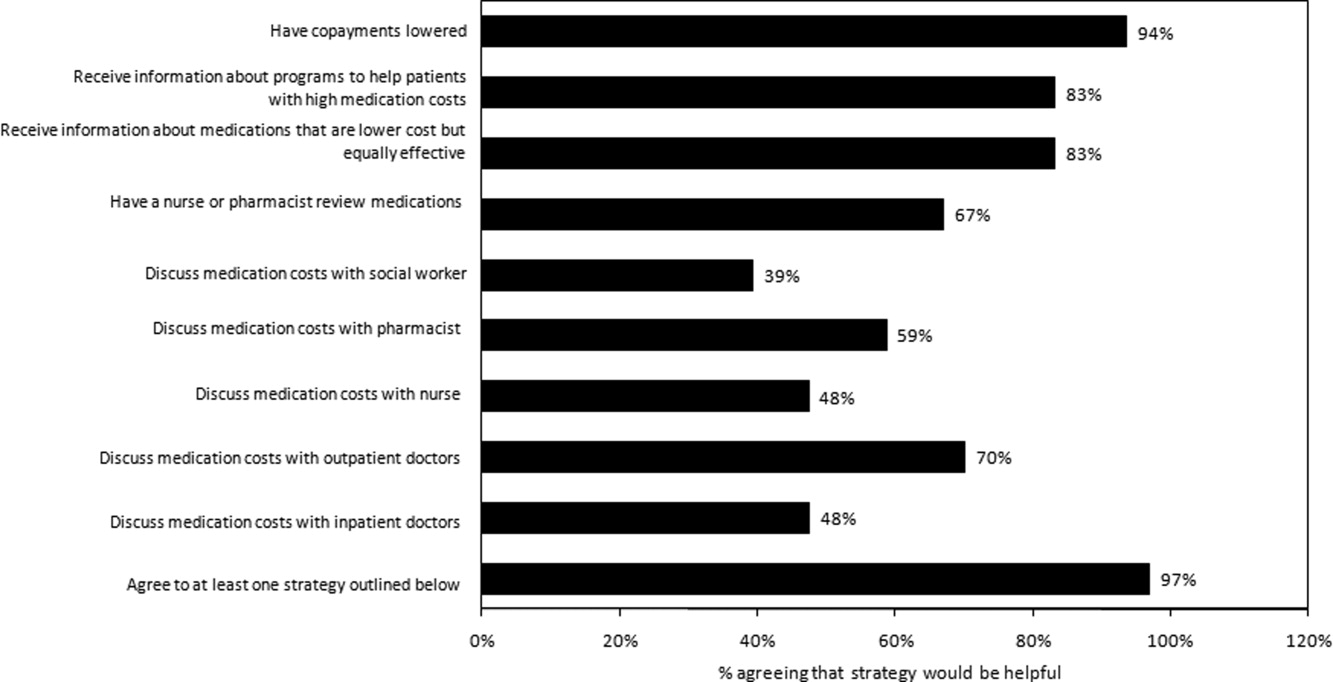

Virtually all respondents (n = 123; 95%) endorsed at least one of the proposed strategies to make medications more affordable (Figure 3). A majority felt that lowering cost sharing (94%), or receiving information about lower‐cost medication options (83%) or programs to subsidize medication costs (83%) would be helpful. Approximately 70% of patients stated that speaking to their outpatient physicians might be helpful, although only 14% reported actually speaking with their primary care provider about medication costs in the past year. Results were mixed for other strategies, including speaking with their inpatient physicians.

Postdischarge Medication Use

Seventy‐six (82%) respondents to the outpatient survey were prescribed a new medication at the time of hospital discharge, and virtually all (95%) had filled prescriptions for these medications by the time of the follow‐up survey. Patients paid an average of $27.63 (standard deviation $39.24) in out‐of‐pocket costs for these medications. Few (16%) patients knew how much they would have to pay before they had gone to the pharmacy to fill their prescription (see Appendix B). Even fewer patients asked, or were spoken to by their pharmacist, about less expensive medication options (7%), and almost none had spoken to their inpatient (4%) or outpatient providers (2%) about the cost of their newly prescribed drugs.

DISCUSSION

Almost a quarter of the medical inpatients we surveyed had not filled a medication because of cost, or had skipped doses, reduced dosages, or split pills to make their medicines last longer in the prior year. This amount is larger than that found in many prior studies, conducted in outpatient settings, in which 11% to 19% of patients report cost‐related underuse.68, 10, 11 Our results are particularly striking considering that our study cohort consisted exclusively of patients with commercial health insurance, the vast majority of whom also had employer‐sponsored drug coverage. Cost‐related medication underuse may be even more prevalent among hospitalized patients with less generous benefits, including the uninsured and perhaps even beneficiaries of Medicare Part D.

Reductions in medication use because of cost were particularly high among black patients, whose odds of reporting cost‐related underuse were more than 3 times higher than that of patients of non‐Hispanic white race. Race‐related differences in cost‐related underuse have been observed in outpatient studies,68, 12 and may be an important contributor to racial disparities in evidence‐based medication use.1315 These differences may, in part, reflect racial variations in socioeconomic status; lower income patients, who are more likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority, are more sensitive to cost sharing than higher income individuals.16 Consistent with this, the relationship between race and cost‐related underuse in our study was smaller but still highly significant in multivariable models that adjusted for income.

Not surprisingly, the underuse of effective prescription medications is associated with adverse clinical and economic consequences.17 Heisler et al. found that patients who had restricted medications because of cost were 76% more likely to report a decline in their health status than those who had not.18 The health effects of cost‐related underuse are likely to be particularly significant for hospitalized patients, given their high burden of disease and the frequency with which they are prescribed medications at discharge to treat the condition that led to their initial hospitalization. Thus, targeting efforts to address cost‐related underuse patients who are hospitalized may be an efficient method of improving patient health and reducing preventable readmissions. This is consistent with efforts that address, in the inpatient setting, other health issues that are commonly encountered in the ambulatory arena, such as immunizations and smoking cessation.19

Our survey respondents endorsed numerous strategies as being potentially helpful. Predictably, support for lowering copayments was extremely high. While this may not be practical or even desirable for some medications, lowering copayments for highly effective medications, such as statins and antihypertensives, in the context of value‐based insurance design, is an increasingly adopted strategy that has the potential to simultaneously improve clinical outcomes and reduce overall health spending.20, 21

While the majority of patients felt that talking to their outpatient physicians or pharmacists about medication costs might be helpful, the effectiveness of this strategy is unclear. Consistent with prior results,22, 23 the vast majority of the patients we surveyed had not discussed medication costs prior to their admission or after filling newly prescribed medications. Further, although physicians could help reduce drug expenditures in a variety of ways, including the increased ordering of generic drugs,24 many physicians are uncomfortable talking to their patients about costs,25 have limited knowledge about their patients' out‐of‐pocket expenditures, feel that addressing this issue is not their responsibility,26 or do not have resources, such as electronic formulary information, that could facilitate these discussions in an efficient manner.

An alternative strategy may be to provide patients with better education about medication costs. Virtually none of the patients we surveyed knew how much they would pay for their new prescriptions before visiting the pharmacy. These findings are similar to those observed in the outpatient setting,27 and suggest an opportunity to provide patients with information about the cost of their newly and previously prescribed drugs, and to facilitate discussions between patients and inpatient providers about predischarge prescribing decisions, in the same spirit as other predischarge patient education.28 Of course, issues related to transitions of care between the hospital and community setting, and coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers, must be adequately addressed for this strategy to be effective.

Our study has several notable limitations. It had a relatively small sample size and low response rate. Respondents may have differed systematically from non‐respondents, and we were unable to compare the characteristics of both populations. Further, we studied commercially insured inpatients on internal medicine services at an academic medical center, and thus our results may not be generalizable to patients hospitalized in other settings, or with different types of insurance coverage, including the uninsured. The primary outcome of our study was to determine self‐reported cost‐related underuse. While we used validated measures,8 it is possible that patients who reported reducing their medication use in response to cost may not have actually done so. We did not collect information on education or health literacy, nor did we have access to detailed information about our respondents' pharmacy benefit design structures; these important factors may have confounded our analyses, and/or may have been mediators of our observed results, and should be evaluated further in future studies. We did not have adequate statistical power to evaluate whether patients using specific classes of medications were particularly prone to cost‐related underuse.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate the impact of medication costs on use in a cohort of hospitalized individuals. The high levels of cost‐related underuse that we observed is concerning. Our results support calls for the further development of interventions to address high medication costs and for the consideration of novel approaches to assist patients around the time of hospital discharge.

APPENDICES

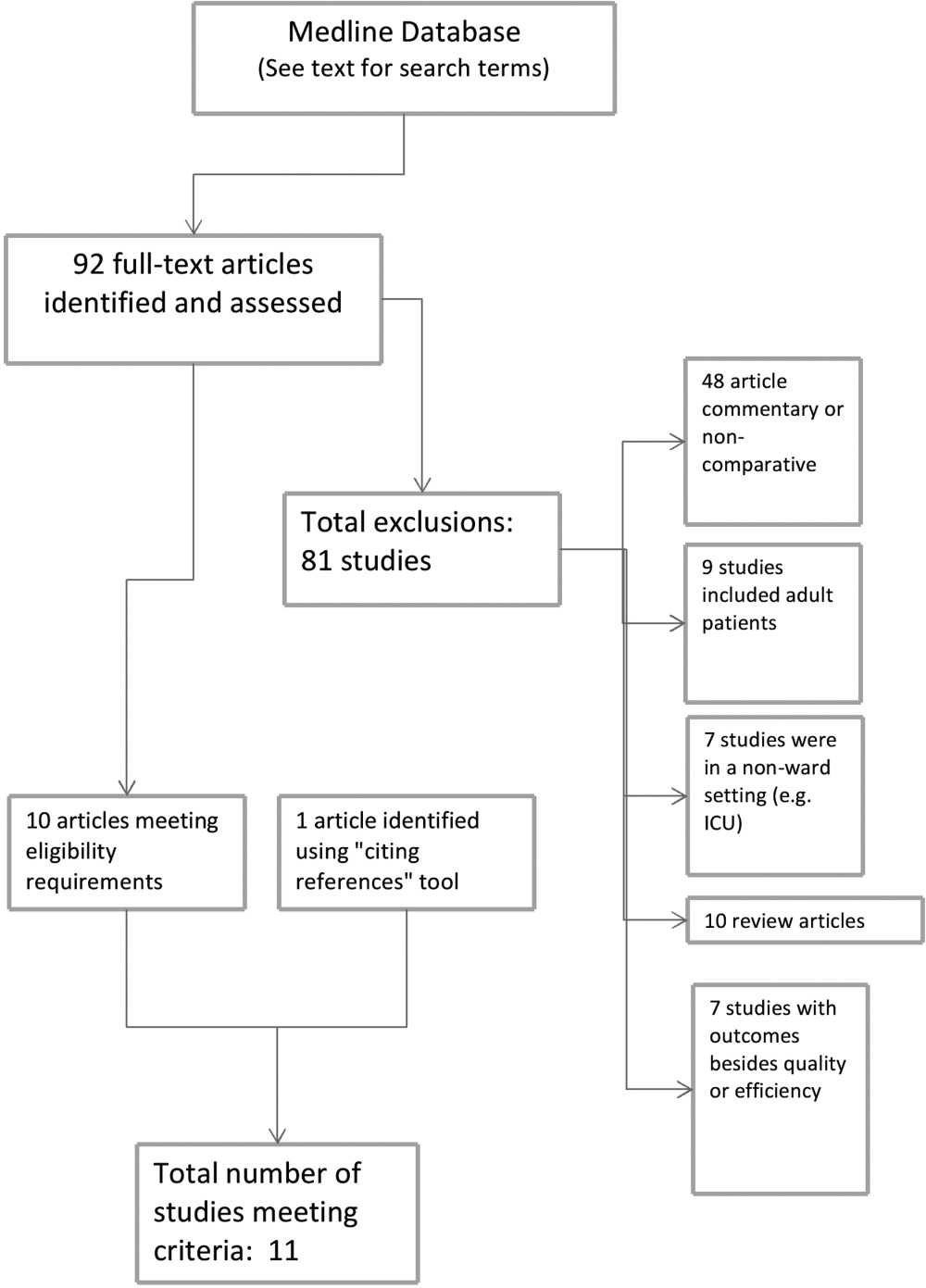

APPENDIX A. Survey response flow diagram.

APPENDIX B. Behaviors to address the cost of medications prescribed at hospital discharge.

- USA Today/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health.The Public on Prescription Drugs and Pharmaceutical Companies.2008. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/pomr030408pkg.cfm. Accessed September 5, 2008.

- ,,, et al.Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill.JAMA.2004;291(19):2344–2350.

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust.Employer Health Benefits Annual Survey,2009.year="2009"2009. Available at: http://ehbs.kff.org/pdf/2009/7936.pdf. Accessed May 5,year="2010"2010.

- Kaiser Family Foundation.Prescription Drug Trends.2007. Available at: http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/upload/3057_06.pdf. Accessed December 5,year="2007"2007.

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, H.R. 3590, Section 2713 (c).Washington, DC:111 Congress;2010.

- ,,, et al.Cost‐related medication nonadherence and spending on basic needs following implementation of Medicare Part D.JAMA.2008;299(16):1922–1928.

- ,,, et al.Race/ethnicity and economic differences in cost‐related medication underuse among insured adults with diabetes: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes Study.Diabetes Care.2008;31(2):261–266.

- ,,, et al.Cost‐related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(17):1829–1835.

- ,,, et al.Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey.Health Aff (Millwood). Jan‐Jun 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives: W5‐152‐W155‐166.

- ,,.Cost‐related medication underuse among chronically ill adults: the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk.Am J Public Health.2004;94(10):1782–1787.

- ,,.Problems paying out‐of‐pocket medication costs among older adults with diabetes.Diabetes Care.2004;27(2):384–391.

- ,,.Race/ethnicity and nonadherence to prescription medications among seniors: results of a national study.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22(11):1572–1578.

- ,,,,,.Long‐term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients.JAMA.2002;288(4):455–461.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid‐lowering therapy.Arch Intern Med.2005;165(10):1147–1152.

- ,,,.Racial disparities in the quality of medication use in older adults: baseline findings from a longitudinal study.J Gen Intern Med.2010;25(3)228–234.

- ,,,,,.Effects of increased patient cost sharing on socioeconomic disparities in health care.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(8):1131–1136.

- .Relationship between high cost sharing and adverse outcomes: a truism that's tough to prove.Am J Manag Care.2010;16(4):287–289.

- ,,,,,.The health effects of restricting prescription medication use because of cost.Med Care.2004;42(7):626–634.

- ,.Smoking cessation initiated during hospital stay for patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial.Can Med Assoc J.2009;180(13):1297–1303.

- .Copayment levels and medication adherence: less is more.Circulation.2009;119(3):365–367.

- ,,,,.Cost‐effectiveness of providing full drug coverage to increase medication adherence in post‐myocardial infarction Medicare beneficiaries.Circulation.2008;117(10):1261–1268.

- ,,.Cost‐related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors?Arch Intern Med.2004;164(16):1749–1755.

- ,,.Patient‐physician communication about out‐of‐pocket costs.JAMA.2003;290(7):953–958.

- ,,,,.Patients' perceptions of generic medications.Health Aff (Millwood).2009;28(2):546–556.

- ,,.Physician strategies to reduce patients' out‐of‐pocket prescription costs.Arch Intern Med.2005;165(6):633–636.

- ,,, et al.Physicians' perceived knowledge of and responsibility for managing patients' out‐of‐pocket costs for prescription drugs.Ann Pharmacother.2006;40(9):1534–1540.

- ,,, et al.The effect of pharmacy benefit design on patient‐physician communication about costs.J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(4):334–339.

- ,,,.Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure.Circulation.2005;111(2):179–185.

The affordability of prescription medications continues to be one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States. Many patients reduce their prescribed doses to make medications last longer or do not fill prescriptions because of cost.1 Cost‐related medication underuse affects patients with and without drug insurance coverage,2 and is likely to become even more problematic as employers scale back on drug benefits3 and drug prices continue to increase.4 The landmark Patient Protection and Affordability Act passed in March 2010 does little to address this issue.5

Existing estimates of cost‐related medication underuse come largely from surveys of ambulatory patients. For example, using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Maden et al. estimated that 11% to 15% of patients reduced medication use in the past year because of cost.6 Tseng and colleagues found very similar rates of cost‐related underuse in managed care beneficiaries with diabetes.7

Hospitalized patients, who have a high burden of disease and tend to use more medications than their ambulatory counterparts, may be particularly vulnerable to cost‐related underuse but, thus far, have been subject to little investigation. New medications, which are frequently prescribed at the time of discharge, may exacerbate these issues further and contribute to preventable readmissions. Accordingly, we surveyed a cohort of medical inpatients at a large academic medical center to estimate the prevalence and predictors of cost‐related medication underuse for hospitalized managed care patients, and to identify strategies that patients perceive as helpful to make medications more affordable.

METHODS

Study Sample

We identified consecutive patients newly admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, or oncology services at Brigham and Women's Hospital from November 2008 to December 2009. For our survey, we included only those patients who received medical benefits through 1 of 3 large insurers with whom our hospital has pay‐for‐performance contracts. Annually, there are approximately 4000 patients covered by these insurers admitted to the 3 clinical services we evaluated, We focused on patients who had a primary care physician at one of the hospital's outpatient practices because of the existence of an automated infrastructure to identify these managed care beneficiaries of these insurers who are newly hospitalized, and because patients covered by commercial insurance plans likely represent a conservative lower‐bound of cost‐related medication underuse among hospitalized patients.

Patients were surveyed on the first non‐holiday weekday after admission. We excluded patients who had been discharged prior to the daily admission list being generated, or who, on a previous admission, had completed our survey or declined to be surveyed. We also excluded several patients who were not beneficiaries of the target insurers and were erroneously included on the managed care admission roster.

Potentially eligible patients were approached on the hospital ward by 1 of 3 study care coordinators (2 nurses and 1 pharmacist) and were asked if they were willing to participate in a research project about medication use that involved a short verbally delivered in‐person (inpatient) survey, a brief postdischarge telephone call, and a review of their electronic health record. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women's Hospital approved this study.

Inpatient Survey

Our survey instrument was developed iteratively and pilot‐tested to improve face validity. Questions about cost‐related underuse were based on validated measures.8, 9 Specifically, we asked whether in the past year patients had: (1) not filled a prescription because it was too expensive, (2) skipped doses to make medicines last longer, (3) took less medicine than prescribed to make the medicine last longer, or (4) split pills to make the medication last longer.

Questions about strategies to improve medication affordability assessed whether patients thought it would be helpful to: (1) discuss medication affordability with healthcare workers (inpatient doctors, outpatient doctors, nurses, pharmacists, or social workers); (2) have their medications reviewed by a nurse or pharmacist; (3) receive information about lower cost but equally effective medication options, or about programs that provide medications at reduced costs; and/or (4) have their copayments/coinsurance lowered. Possible responses to all of these questions were binary, ie, yes or no.

In addition, patients were asked about the nature of their drug insurance coverage, the prescription medications that they currently use, whether they know their copayment levels (for generic and brand‐name medications), and, if so, what these amounts were, their annual household income, and their self‐identified race. Information on patient age, gender, and the primary reason for hospitalization was obtained from the electronic health record. This source was also used to verify the accuracy of the self‐reported preadmission medication list. When there were discrepancies between preadmission medications reported by patients and those recorded in their chart, the later was used because our hospital reconciles and records all medications at the time of hospital admission for all patients.

Postdischarge Survey

Within 3 days of discharge, patients were contacted by telephone and asked about new medications they were prescribed on discharge, if any. The discharge summary was used to verify the accuracy of the information provided by patients. The interviewers clarified any apparent discrepancies between the 2 sources of information with the patient. Patients who had been prescribed a new medication were asked whether or not they had filled their prescription. For patients who had, we asked whether: (1) they knew how much they would have to pay prior to going to the pharmacy, (2) they had discussed less expensive options with their pharmacist, and (3) they had discussed medication costs with their inpatient or outpatient physicians.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of our respondents and our overall survey results. We generated univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to identify whether prehospitalization cost‐related medication underuse was influenced by patient age, gender, income, race, and the number of medications patients used on a regular basis. For the purpose of these analyses, we classified patients as reporting cost‐related underuse if they responded yes to any of the 4 strategies described above (ie, not filling medications, skipping doses, taking less medication, or splitting pills to make medicines last longer). Patients whose incomes were above the median level in our cohort were categorized as being of high‐income. Our multivariable model had a c‐statistic of 0.75, suggesting good discriminative ability.

RESULTS

During the study period, 483 potentially‐eligible patients were admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, and oncology services. We excluded 167 because they had been discharged prior to being identified, had been surveyed or already declined participation on a prior admission, or were not managed care enrollees (see Appendix A). Of the remaining 316 subjects, 130 participated in the inpatient survey (response rate = 41%); 93 (75%) of these patients were reached by telephone after hospital discharge and completed the postdischarge survey. The baseline characteristics of our respondents are presented in Table 1. Patients had a mean age of 52 years, were 50% male and two‐thirds of white race, represented a range of household incomes, and almost all had employer‐sponsored prescription coverage. Prior to admission, patients took an average of 5 prescription medications and paid an average copayment of $10.80 and $21.60 for each generic and brand‐name prescription, respectively.

| Characteristic | N = 130 |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 52 (11.2) |

| Male, % | 65 (50.0) |

| Race/ethnicity,* n (%) | |

| Caucasian/white | 84 (67.2) |

| Black/African American | 20 (16.0) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 13 (10.4) |

| Asian | 3 (2.4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.8) |

| Other | 4 (3.2) |

| Annual household income,* n (%) | |

| <$30,000 | 15 (12.8) |

| $30,000‐$75,000 | 49 (41.9) |

| >$75,000 | 53 (45.3) |

| Insurance coverage for outpatient prescription drugs,* n (%) | |

| Employer or spouse's employer | 123 (96.0) |

| Independent | 5 (3.9) |

| Medication copayments,* mean $ (SD) | |

| Brand‐name medications | 21.6 (14.2) |

| Generic medications | 10.8 (6.0) |

| No. of medications prior to admission, mean (SD) | 5.5 (4.3) |

| Category of discharge diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 40 (30.8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 23 (17.7) |

| Pulmonary | 23 (17.7) |

| Infectious | 13 (10.0) |

| Oncology | 5 (3.8) |

| Renal | 6 (4.6) |

| Psychiatric | 3 (2.3) |

| Hematologic | 4 (3.1) |

| Neurologic | 5 (3.8) |

| Musculoskeletal | 5 (3.8) |

| Respiratory | 2 (1.5) |

| Endocrine | 1 (0.8) |

Cost‐Related Medication Underuse

Thirty (23%) of the survey respondents reported at least 1 cost‐related medication underuse strategy in the year prior to their hospital admission (Figure 1), most commonly not filling a prescription at all because of cost (n = 26; 20%). Rates of cost‐related underuse were highest for patients of black race, low income, and women (Figure 2).

In unadjusted analyses, black respondents had 4.60 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.63 to 13.0) times the odds of reporting cost‐related underuse than non‐Hispanic white respondents (Table 2). The association of black race and cost‐related underuse appears to be confounded, in part, by income (adjusted odds ratio for black race was 4.16; 95% CI, 1.34 to 12.86) and the number of medications patients used on a regular basis (adjusted odds ratio for black race was 4.14; 95% CI, 1.44 to 11.96). After controlling for these variables, as well as age and gender, the relationship between race and cost‐related underuse remained statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio 3.39; 95% CI, 1.05 to 11.02) (Table 2).

| Predictor | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age (per additional year) | 0.98 (0.941.02) | 0.97 (0.931.01) |

| Male (vs female) | 0.84 (0.371.90) | 1.03 (0.432.48) |

| Race (vs white race) | ||

| Black | 4.60 (1.6313.0) | 3.39 (1.0511.02) |

| Other | 1.10 (0.363.37) | 0.77 (0.202.99) |

| No. of medications (per additional medication) | 1.10 (1.001.20) | 1.10 (1.001.22) |

| High income (vs low income) | 0.62 (0.271.42) | 0.71 (0.242.07) |

Strategies to Help Make Medications More Affordable

Virtually all respondents (n = 123; 95%) endorsed at least one of the proposed strategies to make medications more affordable (Figure 3). A majority felt that lowering cost sharing (94%), or receiving information about lower‐cost medication options (83%) or programs to subsidize medication costs (83%) would be helpful. Approximately 70% of patients stated that speaking to their outpatient physicians might be helpful, although only 14% reported actually speaking with their primary care provider about medication costs in the past year. Results were mixed for other strategies, including speaking with their inpatient physicians.

Postdischarge Medication Use

Seventy‐six (82%) respondents to the outpatient survey were prescribed a new medication at the time of hospital discharge, and virtually all (95%) had filled prescriptions for these medications by the time of the follow‐up survey. Patients paid an average of $27.63 (standard deviation $39.24) in out‐of‐pocket costs for these medications. Few (16%) patients knew how much they would have to pay before they had gone to the pharmacy to fill their prescription (see Appendix B). Even fewer patients asked, or were spoken to by their pharmacist, about less expensive medication options (7%), and almost none had spoken to their inpatient (4%) or outpatient providers (2%) about the cost of their newly prescribed drugs.

DISCUSSION

Almost a quarter of the medical inpatients we surveyed had not filled a medication because of cost, or had skipped doses, reduced dosages, or split pills to make their medicines last longer in the prior year. This amount is larger than that found in many prior studies, conducted in outpatient settings, in which 11% to 19% of patients report cost‐related underuse.68, 10, 11 Our results are particularly striking considering that our study cohort consisted exclusively of patients with commercial health insurance, the vast majority of whom also had employer‐sponsored drug coverage. Cost‐related medication underuse may be even more prevalent among hospitalized patients with less generous benefits, including the uninsured and perhaps even beneficiaries of Medicare Part D.

Reductions in medication use because of cost were particularly high among black patients, whose odds of reporting cost‐related underuse were more than 3 times higher than that of patients of non‐Hispanic white race. Race‐related differences in cost‐related underuse have been observed in outpatient studies,68, 12 and may be an important contributor to racial disparities in evidence‐based medication use.1315 These differences may, in part, reflect racial variations in socioeconomic status; lower income patients, who are more likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority, are more sensitive to cost sharing than higher income individuals.16 Consistent with this, the relationship between race and cost‐related underuse in our study was smaller but still highly significant in multivariable models that adjusted for income.

Not surprisingly, the underuse of effective prescription medications is associated with adverse clinical and economic consequences.17 Heisler et al. found that patients who had restricted medications because of cost were 76% more likely to report a decline in their health status than those who had not.18 The health effects of cost‐related underuse are likely to be particularly significant for hospitalized patients, given their high burden of disease and the frequency with which they are prescribed medications at discharge to treat the condition that led to their initial hospitalization. Thus, targeting efforts to address cost‐related underuse patients who are hospitalized may be an efficient method of improving patient health and reducing preventable readmissions. This is consistent with efforts that address, in the inpatient setting, other health issues that are commonly encountered in the ambulatory arena, such as immunizations and smoking cessation.19

Our survey respondents endorsed numerous strategies as being potentially helpful. Predictably, support for lowering copayments was extremely high. While this may not be practical or even desirable for some medications, lowering copayments for highly effective medications, such as statins and antihypertensives, in the context of value‐based insurance design, is an increasingly adopted strategy that has the potential to simultaneously improve clinical outcomes and reduce overall health spending.20, 21

While the majority of patients felt that talking to their outpatient physicians or pharmacists about medication costs might be helpful, the effectiveness of this strategy is unclear. Consistent with prior results,22, 23 the vast majority of the patients we surveyed had not discussed medication costs prior to their admission or after filling newly prescribed medications. Further, although physicians could help reduce drug expenditures in a variety of ways, including the increased ordering of generic drugs,24 many physicians are uncomfortable talking to their patients about costs,25 have limited knowledge about their patients' out‐of‐pocket expenditures, feel that addressing this issue is not their responsibility,26 or do not have resources, such as electronic formulary information, that could facilitate these discussions in an efficient manner.

An alternative strategy may be to provide patients with better education about medication costs. Virtually none of the patients we surveyed knew how much they would pay for their new prescriptions before visiting the pharmacy. These findings are similar to those observed in the outpatient setting,27 and suggest an opportunity to provide patients with information about the cost of their newly and previously prescribed drugs, and to facilitate discussions between patients and inpatient providers about predischarge prescribing decisions, in the same spirit as other predischarge patient education.28 Of course, issues related to transitions of care between the hospital and community setting, and coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers, must be adequately addressed for this strategy to be effective.

Our study has several notable limitations. It had a relatively small sample size and low response rate. Respondents may have differed systematically from non‐respondents, and we were unable to compare the characteristics of both populations. Further, we studied commercially insured inpatients on internal medicine services at an academic medical center, and thus our results may not be generalizable to patients hospitalized in other settings, or with different types of insurance coverage, including the uninsured. The primary outcome of our study was to determine self‐reported cost‐related underuse. While we used validated measures,8 it is possible that patients who reported reducing their medication use in response to cost may not have actually done so. We did not collect information on education or health literacy, nor did we have access to detailed information about our respondents' pharmacy benefit design structures; these important factors may have confounded our analyses, and/or may have been mediators of our observed results, and should be evaluated further in future studies. We did not have adequate statistical power to evaluate whether patients using specific classes of medications were particularly prone to cost‐related underuse.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate the impact of medication costs on use in a cohort of hospitalized individuals. The high levels of cost‐related underuse that we observed is concerning. Our results support calls for the further development of interventions to address high medication costs and for the consideration of novel approaches to assist patients around the time of hospital discharge.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A. Survey response flow diagram.

APPENDIX B. Behaviors to address the cost of medications prescribed at hospital discharge.

The affordability of prescription medications continues to be one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States. Many patients reduce their prescribed doses to make medications last longer or do not fill prescriptions because of cost.1 Cost‐related medication underuse affects patients with and without drug insurance coverage,2 and is likely to become even more problematic as employers scale back on drug benefits3 and drug prices continue to increase.4 The landmark Patient Protection and Affordability Act passed in March 2010 does little to address this issue.5

Existing estimates of cost‐related medication underuse come largely from surveys of ambulatory patients. For example, using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Maden et al. estimated that 11% to 15% of patients reduced medication use in the past year because of cost.6 Tseng and colleagues found very similar rates of cost‐related underuse in managed care beneficiaries with diabetes.7

Hospitalized patients, who have a high burden of disease and tend to use more medications than their ambulatory counterparts, may be particularly vulnerable to cost‐related underuse but, thus far, have been subject to little investigation. New medications, which are frequently prescribed at the time of discharge, may exacerbate these issues further and contribute to preventable readmissions. Accordingly, we surveyed a cohort of medical inpatients at a large academic medical center to estimate the prevalence and predictors of cost‐related medication underuse for hospitalized managed care patients, and to identify strategies that patients perceive as helpful to make medications more affordable.

METHODS

Study Sample

We identified consecutive patients newly admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, or oncology services at Brigham and Women's Hospital from November 2008 to December 2009. For our survey, we included only those patients who received medical benefits through 1 of 3 large insurers with whom our hospital has pay‐for‐performance contracts. Annually, there are approximately 4000 patients covered by these insurers admitted to the 3 clinical services we evaluated, We focused on patients who had a primary care physician at one of the hospital's outpatient practices because of the existence of an automated infrastructure to identify these managed care beneficiaries of these insurers who are newly hospitalized, and because patients covered by commercial insurance plans likely represent a conservative lower‐bound of cost‐related medication underuse among hospitalized patients.

Patients were surveyed on the first non‐holiday weekday after admission. We excluded patients who had been discharged prior to the daily admission list being generated, or who, on a previous admission, had completed our survey or declined to be surveyed. We also excluded several patients who were not beneficiaries of the target insurers and were erroneously included on the managed care admission roster.

Potentially eligible patients were approached on the hospital ward by 1 of 3 study care coordinators (2 nurses and 1 pharmacist) and were asked if they were willing to participate in a research project about medication use that involved a short verbally delivered in‐person (inpatient) survey, a brief postdischarge telephone call, and a review of their electronic health record. The Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women's Hospital approved this study.

Inpatient Survey

Our survey instrument was developed iteratively and pilot‐tested to improve face validity. Questions about cost‐related underuse were based on validated measures.8, 9 Specifically, we asked whether in the past year patients had: (1) not filled a prescription because it was too expensive, (2) skipped doses to make medicines last longer, (3) took less medicine than prescribed to make the medicine last longer, or (4) split pills to make the medication last longer.

Questions about strategies to improve medication affordability assessed whether patients thought it would be helpful to: (1) discuss medication affordability with healthcare workers (inpatient doctors, outpatient doctors, nurses, pharmacists, or social workers); (2) have their medications reviewed by a nurse or pharmacist; (3) receive information about lower cost but equally effective medication options, or about programs that provide medications at reduced costs; and/or (4) have their copayments/coinsurance lowered. Possible responses to all of these questions were binary, ie, yes or no.

In addition, patients were asked about the nature of their drug insurance coverage, the prescription medications that they currently use, whether they know their copayment levels (for generic and brand‐name medications), and, if so, what these amounts were, their annual household income, and their self‐identified race. Information on patient age, gender, and the primary reason for hospitalization was obtained from the electronic health record. This source was also used to verify the accuracy of the self‐reported preadmission medication list. When there were discrepancies between preadmission medications reported by patients and those recorded in their chart, the later was used because our hospital reconciles and records all medications at the time of hospital admission for all patients.

Postdischarge Survey

Within 3 days of discharge, patients were contacted by telephone and asked about new medications they were prescribed on discharge, if any. The discharge summary was used to verify the accuracy of the information provided by patients. The interviewers clarified any apparent discrepancies between the 2 sources of information with the patient. Patients who had been prescribed a new medication were asked whether or not they had filled their prescription. For patients who had, we asked whether: (1) they knew how much they would have to pay prior to going to the pharmacy, (2) they had discussed less expensive options with their pharmacist, and (3) they had discussed medication costs with their inpatient or outpatient physicians.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of our respondents and our overall survey results. We generated univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to identify whether prehospitalization cost‐related medication underuse was influenced by patient age, gender, income, race, and the number of medications patients used on a regular basis. For the purpose of these analyses, we classified patients as reporting cost‐related underuse if they responded yes to any of the 4 strategies described above (ie, not filling medications, skipping doses, taking less medication, or splitting pills to make medicines last longer). Patients whose incomes were above the median level in our cohort were categorized as being of high‐income. Our multivariable model had a c‐statistic of 0.75, suggesting good discriminative ability.

RESULTS

During the study period, 483 potentially‐eligible patients were admitted to the general medicine, cardiology, and oncology services. We excluded 167 because they had been discharged prior to being identified, had been surveyed or already declined participation on a prior admission, or were not managed care enrollees (see Appendix A). Of the remaining 316 subjects, 130 participated in the inpatient survey (response rate = 41%); 93 (75%) of these patients were reached by telephone after hospital discharge and completed the postdischarge survey. The baseline characteristics of our respondents are presented in Table 1. Patients had a mean age of 52 years, were 50% male and two‐thirds of white race, represented a range of household incomes, and almost all had employer‐sponsored prescription coverage. Prior to admission, patients took an average of 5 prescription medications and paid an average copayment of $10.80 and $21.60 for each generic and brand‐name prescription, respectively.

| Characteristic | N = 130 |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 52 (11.2) |

| Male, % | 65 (50.0) |

| Race/ethnicity,* n (%) | |

| Caucasian/white | 84 (67.2) |

| Black/African American | 20 (16.0) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 13 (10.4) |

| Asian | 3 (2.4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.8) |

| Other | 4 (3.2) |

| Annual household income,* n (%) | |

| <$30,000 | 15 (12.8) |

| $30,000‐$75,000 | 49 (41.9) |

| >$75,000 | 53 (45.3) |

| Insurance coverage for outpatient prescription drugs,* n (%) | |

| Employer or spouse's employer | 123 (96.0) |

| Independent | 5 (3.9) |

| Medication copayments,* mean $ (SD) | |

| Brand‐name medications | 21.6 (14.2) |

| Generic medications | 10.8 (6.0) |

| No. of medications prior to admission, mean (SD) | 5.5 (4.3) |

| Category of discharge diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 40 (30.8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 23 (17.7) |

| Pulmonary | 23 (17.7) |

| Infectious | 13 (10.0) |

| Oncology | 5 (3.8) |

| Renal | 6 (4.6) |

| Psychiatric | 3 (2.3) |

| Hematologic | 4 (3.1) |

| Neurologic | 5 (3.8) |

| Musculoskeletal | 5 (3.8) |

| Respiratory | 2 (1.5) |

| Endocrine | 1 (0.8) |

Cost‐Related Medication Underuse

Thirty (23%) of the survey respondents reported at least 1 cost‐related medication underuse strategy in the year prior to their hospital admission (Figure 1), most commonly not filling a prescription at all because of cost (n = 26; 20%). Rates of cost‐related underuse were highest for patients of black race, low income, and women (Figure 2).

In unadjusted analyses, black respondents had 4.60 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.63 to 13.0) times the odds of reporting cost‐related underuse than non‐Hispanic white respondents (Table 2). The association of black race and cost‐related underuse appears to be confounded, in part, by income (adjusted odds ratio for black race was 4.16; 95% CI, 1.34 to 12.86) and the number of medications patients used on a regular basis (adjusted odds ratio for black race was 4.14; 95% CI, 1.44 to 11.96). After controlling for these variables, as well as age and gender, the relationship between race and cost‐related underuse remained statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio 3.39; 95% CI, 1.05 to 11.02) (Table 2).

| Predictor | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age (per additional year) | 0.98 (0.941.02) | 0.97 (0.931.01) |

| Male (vs female) | 0.84 (0.371.90) | 1.03 (0.432.48) |

| Race (vs white race) | ||

| Black | 4.60 (1.6313.0) | 3.39 (1.0511.02) |

| Other | 1.10 (0.363.37) | 0.77 (0.202.99) |

| No. of medications (per additional medication) | 1.10 (1.001.20) | 1.10 (1.001.22) |

| High income (vs low income) | 0.62 (0.271.42) | 0.71 (0.242.07) |

Strategies to Help Make Medications More Affordable

Virtually all respondents (n = 123; 95%) endorsed at least one of the proposed strategies to make medications more affordable (Figure 3). A majority felt that lowering cost sharing (94%), or receiving information about lower‐cost medication options (83%) or programs to subsidize medication costs (83%) would be helpful. Approximately 70% of patients stated that speaking to their outpatient physicians might be helpful, although only 14% reported actually speaking with their primary care provider about medication costs in the past year. Results were mixed for other strategies, including speaking with their inpatient physicians.

Postdischarge Medication Use

Seventy‐six (82%) respondents to the outpatient survey were prescribed a new medication at the time of hospital discharge, and virtually all (95%) had filled prescriptions for these medications by the time of the follow‐up survey. Patients paid an average of $27.63 (standard deviation $39.24) in out‐of‐pocket costs for these medications. Few (16%) patients knew how much they would have to pay before they had gone to the pharmacy to fill their prescription (see Appendix B). Even fewer patients asked, or were spoken to by their pharmacist, about less expensive medication options (7%), and almost none had spoken to their inpatient (4%) or outpatient providers (2%) about the cost of their newly prescribed drugs.

DISCUSSION

Almost a quarter of the medical inpatients we surveyed had not filled a medication because of cost, or had skipped doses, reduced dosages, or split pills to make their medicines last longer in the prior year. This amount is larger than that found in many prior studies, conducted in outpatient settings, in which 11% to 19% of patients report cost‐related underuse.68, 10, 11 Our results are particularly striking considering that our study cohort consisted exclusively of patients with commercial health insurance, the vast majority of whom also had employer‐sponsored drug coverage. Cost‐related medication underuse may be even more prevalent among hospitalized patients with less generous benefits, including the uninsured and perhaps even beneficiaries of Medicare Part D.

Reductions in medication use because of cost were particularly high among black patients, whose odds of reporting cost‐related underuse were more than 3 times higher than that of patients of non‐Hispanic white race. Race‐related differences in cost‐related underuse have been observed in outpatient studies,68, 12 and may be an important contributor to racial disparities in evidence‐based medication use.1315 These differences may, in part, reflect racial variations in socioeconomic status; lower income patients, who are more likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority, are more sensitive to cost sharing than higher income individuals.16 Consistent with this, the relationship between race and cost‐related underuse in our study was smaller but still highly significant in multivariable models that adjusted for income.

Not surprisingly, the underuse of effective prescription medications is associated with adverse clinical and economic consequences.17 Heisler et al. found that patients who had restricted medications because of cost were 76% more likely to report a decline in their health status than those who had not.18 The health effects of cost‐related underuse are likely to be particularly significant for hospitalized patients, given their high burden of disease and the frequency with which they are prescribed medications at discharge to treat the condition that led to their initial hospitalization. Thus, targeting efforts to address cost‐related underuse patients who are hospitalized may be an efficient method of improving patient health and reducing preventable readmissions. This is consistent with efforts that address, in the inpatient setting, other health issues that are commonly encountered in the ambulatory arena, such as immunizations and smoking cessation.19

Our survey respondents endorsed numerous strategies as being potentially helpful. Predictably, support for lowering copayments was extremely high. While this may not be practical or even desirable for some medications, lowering copayments for highly effective medications, such as statins and antihypertensives, in the context of value‐based insurance design, is an increasingly adopted strategy that has the potential to simultaneously improve clinical outcomes and reduce overall health spending.20, 21

While the majority of patients felt that talking to their outpatient physicians or pharmacists about medication costs might be helpful, the effectiveness of this strategy is unclear. Consistent with prior results,22, 23 the vast majority of the patients we surveyed had not discussed medication costs prior to their admission or after filling newly prescribed medications. Further, although physicians could help reduce drug expenditures in a variety of ways, including the increased ordering of generic drugs,24 many physicians are uncomfortable talking to their patients about costs,25 have limited knowledge about their patients' out‐of‐pocket expenditures, feel that addressing this issue is not their responsibility,26 or do not have resources, such as electronic formulary information, that could facilitate these discussions in an efficient manner.

An alternative strategy may be to provide patients with better education about medication costs. Virtually none of the patients we surveyed knew how much they would pay for their new prescriptions before visiting the pharmacy. These findings are similar to those observed in the outpatient setting,27 and suggest an opportunity to provide patients with information about the cost of their newly and previously prescribed drugs, and to facilitate discussions between patients and inpatient providers about predischarge prescribing decisions, in the same spirit as other predischarge patient education.28 Of course, issues related to transitions of care between the hospital and community setting, and coordination between inpatient and outpatient providers, must be adequately addressed for this strategy to be effective.

Our study has several notable limitations. It had a relatively small sample size and low response rate. Respondents may have differed systematically from non‐respondents, and we were unable to compare the characteristics of both populations. Further, we studied commercially insured inpatients on internal medicine services at an academic medical center, and thus our results may not be generalizable to patients hospitalized in other settings, or with different types of insurance coverage, including the uninsured. The primary outcome of our study was to determine self‐reported cost‐related underuse. While we used validated measures,8 it is possible that patients who reported reducing their medication use in response to cost may not have actually done so. We did not collect information on education or health literacy, nor did we have access to detailed information about our respondents' pharmacy benefit design structures; these important factors may have confounded our analyses, and/or may have been mediators of our observed results, and should be evaluated further in future studies. We did not have adequate statistical power to evaluate whether patients using specific classes of medications were particularly prone to cost‐related underuse.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to evaluate the impact of medication costs on use in a cohort of hospitalized individuals. The high levels of cost‐related underuse that we observed is concerning. Our results support calls for the further development of interventions to address high medication costs and for the consideration of novel approaches to assist patients around the time of hospital discharge.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A. Survey response flow diagram.

APPENDIX B. Behaviors to address the cost of medications prescribed at hospital discharge.

- USA Today/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health.The Public on Prescription Drugs and Pharmaceutical Companies.2008. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/pomr030408pkg.cfm. Accessed September 5, 2008.

- ,,, et al.Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill.JAMA.2004;291(19):2344–2350.

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust.Employer Health Benefits Annual Survey,2009.year="2009"2009. Available at: http://ehbs.kff.org/pdf/2009/7936.pdf. Accessed May 5,year="2010"2010.

- Kaiser Family Foundation.Prescription Drug Trends.2007. Available at: http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/upload/3057_06.pdf. Accessed December 5,year="2007"2007.

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, H.R. 3590, Section 2713 (c).Washington, DC:111 Congress;2010.

- ,,, et al.Cost‐related medication nonadherence and spending on basic needs following implementation of Medicare Part D.JAMA.2008;299(16):1922–1928.

- ,,, et al.Race/ethnicity and economic differences in cost‐related medication underuse among insured adults with diabetes: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes Study.Diabetes Care.2008;31(2):261–266.

- ,,, et al.Cost‐related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(17):1829–1835.

- ,,, et al.Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey.Health Aff (Millwood). Jan‐Jun 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives: W5‐152‐W155‐166.

- ,,.Cost‐related medication underuse among chronically ill adults: the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk.Am J Public Health.2004;94(10):1782–1787.

- ,,.Problems paying out‐of‐pocket medication costs among older adults with diabetes.Diabetes Care.2004;27(2):384–391.

- ,,.Race/ethnicity and nonadherence to prescription medications among seniors: results of a national study.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22(11):1572–1578.

- ,,,,,.Long‐term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients.JAMA.2002;288(4):455–461.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid‐lowering therapy.Arch Intern Med.2005;165(10):1147–1152.

- ,,,.Racial disparities in the quality of medication use in older adults: baseline findings from a longitudinal study.J Gen Intern Med.2010;25(3)228–234.

- ,,,,,.Effects of increased patient cost sharing on socioeconomic disparities in health care.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(8):1131–1136.

- .Relationship between high cost sharing and adverse outcomes: a truism that's tough to prove.Am J Manag Care.2010;16(4):287–289.

- ,,,,,.The health effects of restricting prescription medication use because of cost.Med Care.2004;42(7):626–634.

- ,.Smoking cessation initiated during hospital stay for patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial.Can Med Assoc J.2009;180(13):1297–1303.

- .Copayment levels and medication adherence: less is more.Circulation.2009;119(3):365–367.

- ,,,,.Cost‐effectiveness of providing full drug coverage to increase medication adherence in post‐myocardial infarction Medicare beneficiaries.Circulation.2008;117(10):1261–1268.

- ,,.Cost‐related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors?Arch Intern Med.2004;164(16):1749–1755.

- ,,.Patient‐physician communication about out‐of‐pocket costs.JAMA.2003;290(7):953–958.

- ,,,,.Patients' perceptions of generic medications.Health Aff (Millwood).2009;28(2):546–556.

- ,,.Physician strategies to reduce patients' out‐of‐pocket prescription costs.Arch Intern Med.2005;165(6):633–636.

- ,,, et al.Physicians' perceived knowledge of and responsibility for managing patients' out‐of‐pocket costs for prescription drugs.Ann Pharmacother.2006;40(9):1534–1540.

- ,,, et al.The effect of pharmacy benefit design on patient‐physician communication about costs.J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(4):334–339.

- ,,,.Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure.Circulation.2005;111(2):179–185.

- USA Today/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard School of Public Health.The Public on Prescription Drugs and Pharmaceutical Companies.2008. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/pomr030408pkg.cfm. Accessed September 5, 2008.

- ,,, et al.Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill.JAMA.2004;291(19):2344–2350.

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust.Employer Health Benefits Annual Survey,2009.year="2009"2009. Available at: http://ehbs.kff.org/pdf/2009/7936.pdf. Accessed May 5,year="2010"2010.

- Kaiser Family Foundation.Prescription Drug Trends.2007. Available at: http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/upload/3057_06.pdf. Accessed December 5,year="2007"2007.

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, H.R. 3590, Section 2713 (c).Washington, DC:111 Congress;2010.

- ,,, et al.Cost‐related medication nonadherence and spending on basic needs following implementation of Medicare Part D.JAMA.2008;299(16):1922–1928.

- ,,, et al.Race/ethnicity and economic differences in cost‐related medication underuse among insured adults with diabetes: the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes Study.Diabetes Care.2008;31(2):261–266.

- ,,, et al.Cost‐related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(17):1829–1835.

- ,,, et al.Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey.Health Aff (Millwood). Jan‐Jun 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives: W5‐152‐W155‐166.

- ,,.Cost‐related medication underuse among chronically ill adults: the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk.Am J Public Health.2004;94(10):1782–1787.

- ,,.Problems paying out‐of‐pocket medication costs among older adults with diabetes.Diabetes Care.2004;27(2):384–391.

- ,,.Race/ethnicity and nonadherence to prescription medications among seniors: results of a national study.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22(11):1572–1578.

- ,,,,,.Long‐term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients.JAMA.2002;288(4):455–461.

- ,,, et al.Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid‐lowering therapy.Arch Intern Med.2005;165(10):1147–1152.

- ,,,.Racial disparities in the quality of medication use in older adults: baseline findings from a longitudinal study.J Gen Intern Med.2010;25(3)228–234.

- ,,,,,.Effects of increased patient cost sharing on socioeconomic disparities in health care.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(8):1131–1136.

- .Relationship between high cost sharing and adverse outcomes: a truism that's tough to prove.Am J Manag Care.2010;16(4):287–289.

- ,,,,,.The health effects of restricting prescription medication use because of cost.Med Care.2004;42(7):626–634.

- ,.Smoking cessation initiated during hospital stay for patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial.Can Med Assoc J.2009;180(13):1297–1303.

- .Copayment levels and medication adherence: less is more.Circulation.2009;119(3):365–367.

- ,,,,.Cost‐effectiveness of providing full drug coverage to increase medication adherence in post‐myocardial infarction Medicare beneficiaries.Circulation.2008;117(10):1261–1268.

- ,,.Cost‐related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors?Arch Intern Med.2004;164(16):1749–1755.

- ,,.Patient‐physician communication about out‐of‐pocket costs.JAMA.2003;290(7):953–958.

- ,,,,.Patients' perceptions of generic medications.Health Aff (Millwood).2009;28(2):546–556.

- ,,.Physician strategies to reduce patients' out‐of‐pocket prescription costs.Arch Intern Med.2005;165(6):633–636.

- ,,, et al.Physicians' perceived knowledge of and responsibility for managing patients' out‐of‐pocket costs for prescription drugs.Ann Pharmacother.2006;40(9):1534–1540.

- ,,, et al.The effect of pharmacy benefit design on patient‐physician communication about costs.J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(4):334–339.

- ,,,.Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure.Circulation.2005;111(2):179–185.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist Versus Traditional Systems

In the United States, general medical inpatient care is increasingly provided by hospital‐based physicians, also called hospitalists.1 The field of pediatrics is no exception, and by 2005 there were an estimated 1000 pediatric hospitalists in the workforce.2 Current numbers are likely to be greater than 2500, as the need for pediatric hospitalists has grown considerably.

At the same time, the quality of care delivered by the United States health system has come under increased scrutiny. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine, in its report on the quality of healthcare in America, concluded that between the care we have and what we could have lies not just a gap but a chasm.3 Meanwhile, the cost of healthcare delivery continues to increase. The pressure to deliver cost‐effective, high quality care is among the more important forces driving the proliferation of hospitalists.4

Over the last decade, data supporting the role of hospitalists in improving quality of care for adult patients has continued to accumulate.58 A 2007 retrospective cohort study by Lindenaur et al.7 included nearly 77,000 adult patients and found small reductions in length of stay without adverse effects on mortality or readmission rates, and a 2009 systematic review by Peterson6 included 33 studies and concluded that in general inpatient care of general medical patients by hospitalist physicians leads to decreased hospital cost and length of stay. A 2002 study by Meltzer et al.8 is also interesting, suggesting that improvements in costs and short‐term mortality are related to the disease‐specific experience of hospitalists.

Similar data for pediatric hospitalists has been slower to emerge. A systematic review of the literature by Landrigan et al., which included studies through 2004, concluded that [R]esearch suggests that pediatric hospitalists decrease costs and length of stay . The quality of care in pediatric hospitalist systems is unclear, because rigorous metrics to evaluate quality are lacking.9 Since the publication of that review, there have been multiple studies which have sought to evaluate the quality of pediatric hospitalist systems. This review was undertaken to synthesize this new information, and to determine the effect of pediatric hospitalist systems on quality of care.

METHODS

A review of the available English language literature on the Medline database was undertaken in November of 2010 to answer the question, What are the differences in quality of care and outcomes of inpatient medical care provided by hospitalists versus non‐hospitalists in the pediatric population? Care metrics of interest were categorized according to the Society of Hospital Medicine's recommendations for measuring hospital performance.10

Search terms used (with additional medical subject headings [MeSH] terms in parenthesis) were hospital medicine (hospitalist), pediatrics (child health, child welfare), cost (cost and cost analysis), quality (quality indicators, healthcare), outcomes (outcome assessment, healthcare; outcomes and process assessment, healthcare); volume, patient satisfaction, length of stay, productivity (efficiency), provider satisfaction (attitude of health personnel, job satisfaction), mortality, and readmission rate (patient readmission). The citing articles search tool was used to identify other articles that potentially could meet criteria. Finally, references cited in the selected articles, as well as in excluded literature reviews, were searched for additional articles.

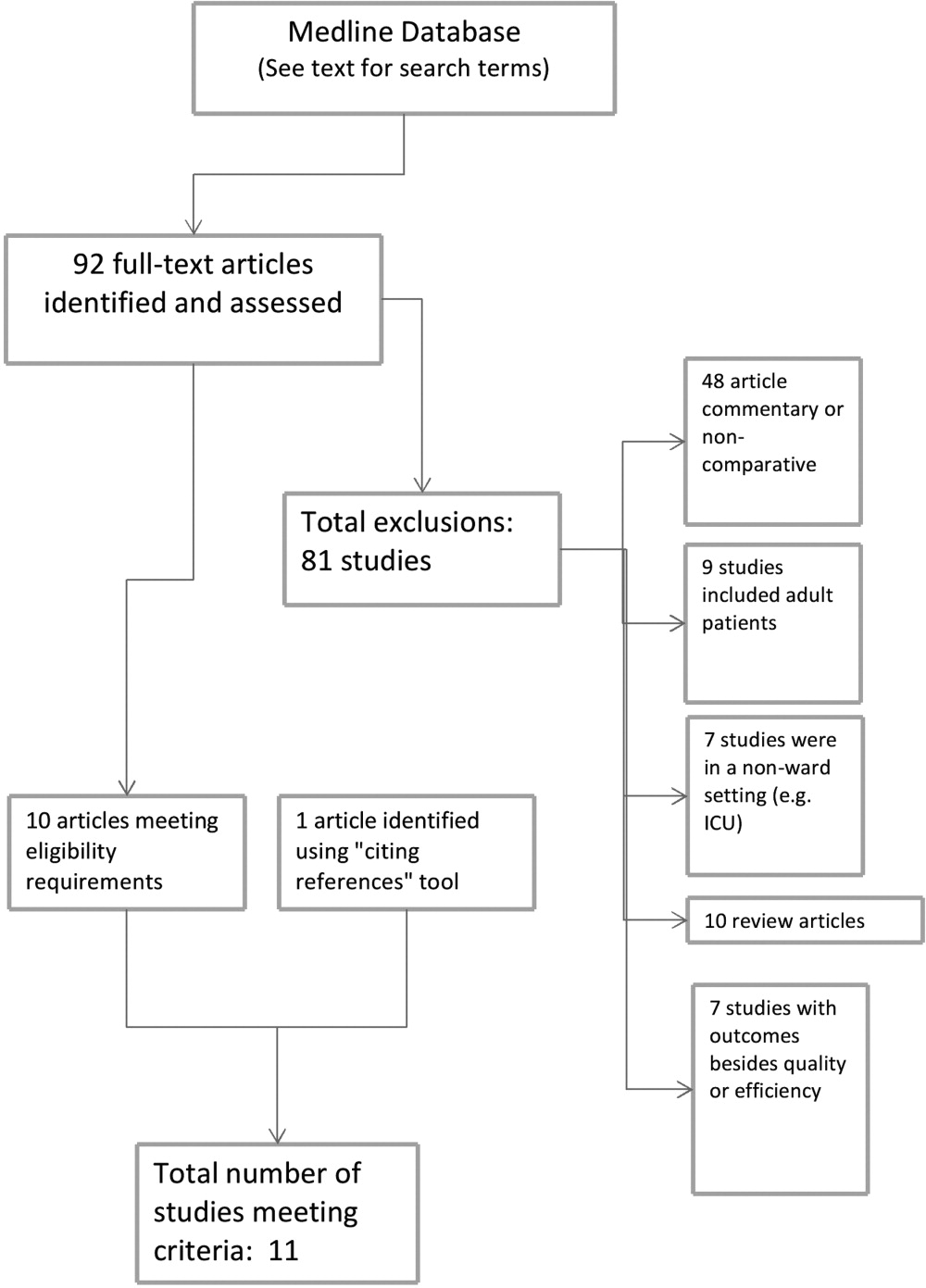

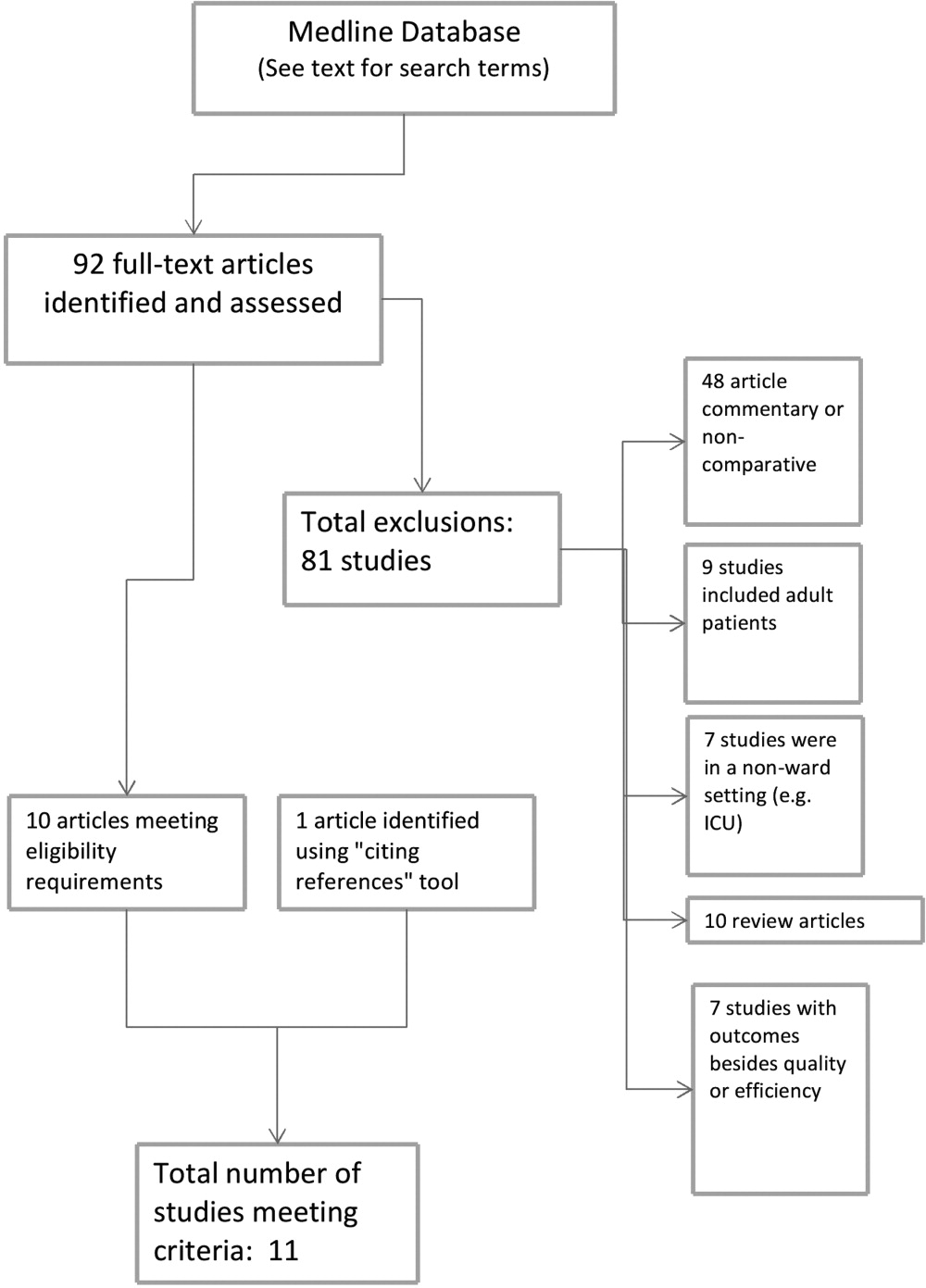

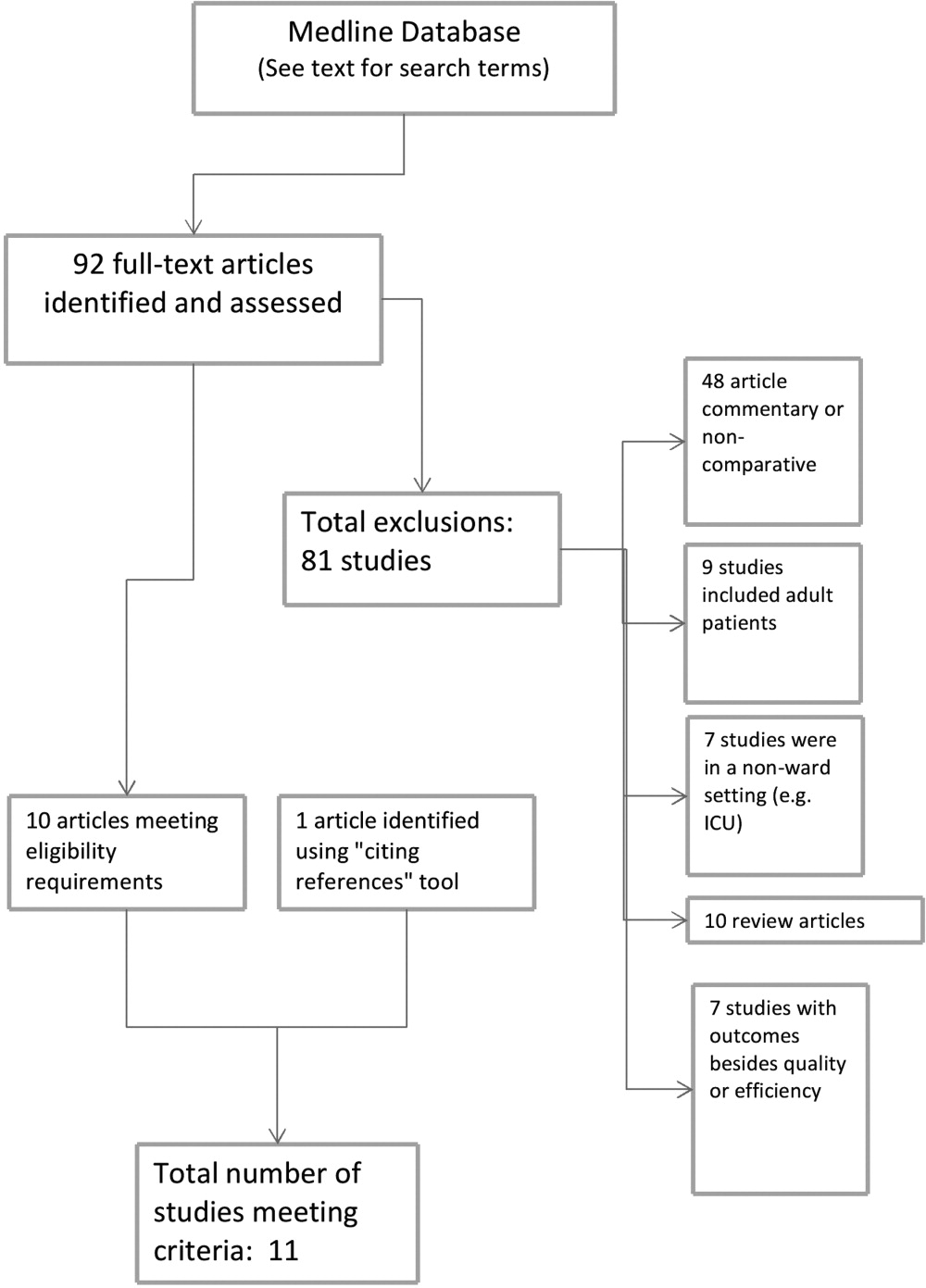

Articles were deemed eligible if they were published in a peer‐reviewed journal, if they had a comparative experimental design for hospitalists versus non‐hospitalists, and if they dealt exclusively with pediatric hospitalists. Noncomparative studies were excluded, as were studies that pertained to settings besides that of an inpatient pediatrics ward, such as pediatric intensive care units or emergency rooms. The search algorithm is diagrammed in Figure 1.

The selected articles were reviewed for the relevant outcome measures. The quality of each article was assessed using the Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine levels of evidence,11 a widely accepted standard for critical analysis of studies. Levels of evidence are assigned to studies, from 1a (systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials) to 5 (expert opinion only). Well‐conducted prospective cohort studies receive a rating of 2c; those with wide confidence intervals due to small sample size receive a minus () modifier. This system does not specifically address survey studies, which were therefore not assigned a level of evidence.

RESULTS

The screening process yielded 92 possible relevant articles, which were then reviewed individually (by G.M.M.) by title and abstract. A total of 81 articles were excluded, including 48 studies that were either noncomparative or descriptive in nature. Ten of the identified articles were reviews and did not contain primary data. Nine studies were not restricted to the pediatric population. Also excluded were 7 studies that did not have outcomes related to quality (eg, billing performance), and 7 studies of hospitalists in settings besides general pediatric wards (eg, pediatric intensive care units). Ten studies were thus identified. The cited reference tool was used to identify an additional article which met criteria, yielding 11 total articles that were included in the review.

Five of the identified studies published prior to 2005 were previously reviewed by Landrigan et al.9 Since then, 6 additional studies of similar nature have been published and were included here. Articles that met criteria but appeared in an earlier review are included in Table 1; new articles appear in Table 2. The results of all 11 articles were included for this discussion.

| Source | Site | Study Design | Outcomes Measured (Oxford Level of Evidence) | Results for Hospitalists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Bellet and Whitaker13 (2000) | Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH | 1440 general pediatric patients | LOS, costs (2c) | LOS shorter (2.4 vs 2.7 days) |

| Retrospective cohort study | Readmission rate, subspecialty consultations, mortality (2c, low power) | Costs lower ($2720 vs $3002) | ||

| Readmissions higher for hospitalists (1% vs 3%) | ||||

| No differences in consultations | ||||

| No mortality in study | ||||

| Ogershok et al.16 (2001) | West Virginia University Children's Hospitals, Morgantown, WV | 2177 general pediatric patients | LOS, cost (2c) | No difference in LOS |

| Retrospective cohort study | Readmission rate, patient satisfaction, mortality (2c, low power) | Costs lower ($1238 vs $1421) | ||

| Lab and radiology tests ordered less often | ||||

| No difference in mortality or readmission rates | ||||

| No difference in satisfaction scores | ||||

| Wells et al.15 (2001) | Valley Children's Hospital, Madera, CA | 182 general pediatric patients | LOS, cost, patient satisfaction, follow‐up rate (2c, low power) | LOS shorter (45.2 vs 66.8 hr; P = 0.01) |

| Prospective cohort study | No LOS or cost benefit for patients with bronchiolitis, gastroenteritis, or pneumonia | |||

| Costs lower ($2701 vs $4854; P = 0.005) for patients with asthma | ||||

| No difference in outpatient follow‐up rate | ||||

| Landrigan et al.14 (2002) | Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA | 17,873 general pediatric patients | LOS, cost (2c) | LOS shorter (2.2 vs 2.5 days) |

| Retrospective cohort study | Readmission rate, follow‐up rate, mortality (2c, low power) | Costs lower ($1139 vs $1356) | ||

| No difference in follow‐up rate | ||||

| No mortality in study | ||||

| Dwight et al.12 (2004) | Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada | 3807 general pediatric patients | LOS (2c) | LOS shorter (from 2.9 to 2.5 days; P = 0.04) |

| Retrospective cohort study | Subspecialty consultations, readmission rate, mortality (2c, low power) | No difference in readmission rates | ||

| No difference in mortality | ||||

| Source | Site | Study Design | Outcomes Measured (Oxford Level of Evidence) | Results for Hospitalists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Boyd et al.21 (2006) | St Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ | 1009 patients with 11 most common DRGs (3 groups) | Cost, LOS, and readmission rate (2c, low power) | LOS longer (2.6 2.0 vs 3.1 2.6 vs 2.9 2.3, mean SD) |

| Retrospective cohort study | Costs higher ($1781 $1449 (faculty) vs $1954 $1212 (hospitalist group 1) vs $1964 $1495 (hospitalist group 2) | |||

| No difference in readmission rates | ||||

| Conway et al.22 (2006) | National provider survey | 213 hospitalists and 352 community pediatrician survey responses | Self‐reported evidence‐based medicine use (descriptive study, no assignable level) | Hospitalists more likely to follow EBG for following: VCUG and RUS after first UTI, albuterol and ipratropium in first 24 hr for asthma |

| Descriptive study | Hospitalists less likely to use the following unproven therapies: levalbuterol and inhaled or oral steroids for bronchiolitis, stool culture or rotavirus testing for gastroenteritis, or ipratropium after 24 hr for asthma | |||