User login

The 12 Dangers of Christmas

The 12 Dangers of Christmas

The carol promises partridges and pears. The reality, every December, is a predictable spike in injuries, illness, and emergency care.

Framed around the familiar “12 Days of Christmas,” this seasonal guide sets out the most common festive hazards — many of them preventable — and the practical advice clinicians can share to help patients enjoy a safer holiday.

1. Fire

Candles, open fires, and busy kitchens make December the most dangerous month for house fires. Home fires rise 10% in December and peak on Christmas Day at 53% above average, according to the National Fire Chiefs Council.

Alcohol, distraction, and festive cooking all add to the risk.

- Check for fire hazards before Christmas.

- Never leave cookers or candle unattended.

- Check Christmas lights and avoid overloading sockets.

- Ensure a working smoke alarm on each floor and keep escape routes clear.

- Remember that emollient residues on fabrics are highly flammable.

2. Christmas Trees and Decorations

Trees and trimmings bring their own risk. Christmas trees injure about 1000 people each year, according to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA).

A National Accident Helpline (NAH) survey found that 2.7% of respondents had experienced electric shock from faulty lights. Artificial trees, chosen by 76% of households, carry a sixfold higher injury risk. Real trees dry out and become highly flammable — “a giant bundle of kindling covered in electrical wires,” warned safety analysts TapRooT.

- Water live trees regularly — unplug lights first.

- Keep trees stable and at least 3 feet from heat sources.

- Switch off lights before bed or leaving the house.

- Do not hang stockings near open flames.

- Hang fragile decorations high up.

- Supervise children and pets.

3. Slips, Trips, and Falls

The third danger is underfoot. Falls, burns, and cuts send around 80,000 people to A&E each Christmas, according to RoSPA.

One in 50 people fall from their loft while retrieving decorations, the NAH warned.

- Use sturdy ladders and wear footwear with good grip.

- Keep floors clear of presents, wrapping, cables, and spills.

- Never melt ice with boiling water; refreezing can make surfaces more treacherous.

4. Food and Drug Interactions

Festive eating can interfere with medicines. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) warned that drug-food interactions are not always listed on packaging.

- Grapefruit interacts with multiple drugs.

- Cranberries can enhance warfarin's anticoagulant effect, while vitamin K-rich foods, including sprouts, may reduce it.

- Rich desserts can destabilize blood glucose.

- Tyramine-rich foods, including cheeses and dark chocolate, may trigger migraines or hypertensive crises with monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

5. Alcohol

Up to 70% of weekend A&E attendances are alcohol-related, with numbers rising over Christmas. The MHRA warned that mixing alcohol with medicines can cause drowsiness, impaired coordination, and accidents.

- Avoid drinking on an empty stomach.

- Be cautious of unfamiliar drinks.

- Alternate alcoholic and soft drinks.

- Avoid potentially aggressive intoxicated people.

6. Kitchen Calamities

The festive kitchen is a frequent source of injury. NAH data showed that 49% of people reported accidents while preparing Christmas food. Cuts accounted for 18%, and burns from hot fat 11%. In addition, the Food Standards Agency said that 46% of Christmas cooks do not check use-by dates.

- Keep children and trip hazards out of the kitchen.

- Use back hobs and turn saucepan handles inward.

- Never leave ovens or pans unattended.

- Discard out-of-date food.

- Refrigerate leftovers within 2 hours.

7. Children's Vulnerabilities

Christmas presents bring hidden dangers for children. Button batteries and magnets can inflict serious gastrointestinal damage if swallowed.

- Choose age-appropriate, well-made toys.

- Store batteries, magnets, medicines, and chemicals out of reach.

- Avoid sharp or breakable decorations.

- Place holly, mistletoe, and poinsettias well out of reach.

8. Eye Injuries

Eye injuries surge over Christmas. Champagne corks can travel at nearly 50 mph, risking globe rupture or retinal detachment.

Conifer needles, glitter, and artificial snow can all cause corneal injury.

- Point champagne bottles and party poppers away from people's faces.

- Take care when handling Christmas trees.

- Avoid hanging ornaments at children's eye level.

- Rinse glitter-contaminated eyes with sterile saline.

9. Existing Ailments

By the ninth day, routine has often collapsed. Festive excess, stress and disrupted schedules can destabilize chronic disease.

- Ensure adequate medicines and testing supplies.

- Let hosts know dietary needs in advance.

- Avoid excess salt and alcohol in cardiovascular disease, and excess potassium in kidney disease.

- Increase blood glucose monitoring in diabetes.

10. Presents

Not all gifts are benign. The Child Accident Prevention Trust warned that cheap or counterfeit products may bypass safety standards.

UK safety authorities report that counterfeit Labubu dolls have made up a large share of the roughly 259,000 counterfeit toys seized at UK borders this year, and many have failed safety tests.

- Be cautious when buying for toddlers.

- Look for recognized safety markings.

- Avoid toys with strong magnets or button batteries.

- Laser pointers can cause permanent damage to vision.

11. Stress

As Christmas approaches, pressure mounts. In an NAH survey, 12% of men and 20% of women said they felt rushed, 32% of women were stressed, and 18% overwhelmed.

- Prioritize sleep.

- Get outdoors for early morning light.

- Ask for help and delegate chores.

12. Other People

The final hazard is often the most familiar: Family tension is almost traditional. In one survey, 37% of people said Christmas "wouldn't be the same" without arguments, and 54% admitted enjoying them.

- Set boundaries and agree expectations early.

- Stick to a budget.

- Avoid known flashpoint topics, such as politics.

- Create a quiet space for time out.

- One in 9 people spend Christmas alone. Plan ahead to make it a special day.

The hazards may feel seasonal, but the outcomes are not. For clinicians, the 12 risks offer a reminder that small interventions before Christmas can prevent significant harm after it.

Dr Sheena Meredith is an established medical writer, editor, and consultant in healthcare communications, with extensive experience writing for medical professionals and the general public. She is qualified in medicine and in law and medical ethics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The carol promises partridges and pears. The reality, every December, is a predictable spike in injuries, illness, and emergency care.

Framed around the familiar “12 Days of Christmas,” this seasonal guide sets out the most common festive hazards — many of them preventable — and the practical advice clinicians can share to help patients enjoy a safer holiday.

1. Fire

Candles, open fires, and busy kitchens make December the most dangerous month for house fires. Home fires rise 10% in December and peak on Christmas Day at 53% above average, according to the National Fire Chiefs Council.

Alcohol, distraction, and festive cooking all add to the risk.

- Check for fire hazards before Christmas.

- Never leave cookers or candle unattended.

- Check Christmas lights and avoid overloading sockets.

- Ensure a working smoke alarm on each floor and keep escape routes clear.

- Remember that emollient residues on fabrics are highly flammable.

2. Christmas Trees and Decorations

Trees and trimmings bring their own risk. Christmas trees injure about 1000 people each year, according to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA).

A National Accident Helpline (NAH) survey found that 2.7% of respondents had experienced electric shock from faulty lights. Artificial trees, chosen by 76% of households, carry a sixfold higher injury risk. Real trees dry out and become highly flammable — “a giant bundle of kindling covered in electrical wires,” warned safety analysts TapRooT.

- Water live trees regularly — unplug lights first.

- Keep trees stable and at least 3 feet from heat sources.

- Switch off lights before bed or leaving the house.

- Do not hang stockings near open flames.

- Hang fragile decorations high up.

- Supervise children and pets.

3. Slips, Trips, and Falls

The third danger is underfoot. Falls, burns, and cuts send around 80,000 people to A&E each Christmas, according to RoSPA.

One in 50 people fall from their loft while retrieving decorations, the NAH warned.

- Use sturdy ladders and wear footwear with good grip.

- Keep floors clear of presents, wrapping, cables, and spills.

- Never melt ice with boiling water; refreezing can make surfaces more treacherous.

4. Food and Drug Interactions

Festive eating can interfere with medicines. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) warned that drug-food interactions are not always listed on packaging.

- Grapefruit interacts with multiple drugs.

- Cranberries can enhance warfarin's anticoagulant effect, while vitamin K-rich foods, including sprouts, may reduce it.

- Rich desserts can destabilize blood glucose.

- Tyramine-rich foods, including cheeses and dark chocolate, may trigger migraines or hypertensive crises with monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

5. Alcohol

Up to 70% of weekend A&E attendances are alcohol-related, with numbers rising over Christmas. The MHRA warned that mixing alcohol with medicines can cause drowsiness, impaired coordination, and accidents.

- Avoid drinking on an empty stomach.

- Be cautious of unfamiliar drinks.

- Alternate alcoholic and soft drinks.

- Avoid potentially aggressive intoxicated people.

6. Kitchen Calamities

The festive kitchen is a frequent source of injury. NAH data showed that 49% of people reported accidents while preparing Christmas food. Cuts accounted for 18%, and burns from hot fat 11%. In addition, the Food Standards Agency said that 46% of Christmas cooks do not check use-by dates.

- Keep children and trip hazards out of the kitchen.

- Use back hobs and turn saucepan handles inward.

- Never leave ovens or pans unattended.

- Discard out-of-date food.

- Refrigerate leftovers within 2 hours.

7. Children's Vulnerabilities

Christmas presents bring hidden dangers for children. Button batteries and magnets can inflict serious gastrointestinal damage if swallowed.

- Choose age-appropriate, well-made toys.

- Store batteries, magnets, medicines, and chemicals out of reach.

- Avoid sharp or breakable decorations.

- Place holly, mistletoe, and poinsettias well out of reach.

8. Eye Injuries

Eye injuries surge over Christmas. Champagne corks can travel at nearly 50 mph, risking globe rupture or retinal detachment.

Conifer needles, glitter, and artificial snow can all cause corneal injury.

- Point champagne bottles and party poppers away from people's faces.

- Take care when handling Christmas trees.

- Avoid hanging ornaments at children's eye level.

- Rinse glitter-contaminated eyes with sterile saline.

9. Existing Ailments

By the ninth day, routine has often collapsed. Festive excess, stress and disrupted schedules can destabilize chronic disease.

- Ensure adequate medicines and testing supplies.

- Let hosts know dietary needs in advance.

- Avoid excess salt and alcohol in cardiovascular disease, and excess potassium in kidney disease.

- Increase blood glucose monitoring in diabetes.

10. Presents

Not all gifts are benign. The Child Accident Prevention Trust warned that cheap or counterfeit products may bypass safety standards.

UK safety authorities report that counterfeit Labubu dolls have made up a large share of the roughly 259,000 counterfeit toys seized at UK borders this year, and many have failed safety tests.

- Be cautious when buying for toddlers.

- Look for recognized safety markings.

- Avoid toys with strong magnets or button batteries.

- Laser pointers can cause permanent damage to vision.

11. Stress

As Christmas approaches, pressure mounts. In an NAH survey, 12% of men and 20% of women said they felt rushed, 32% of women were stressed, and 18% overwhelmed.

- Prioritize sleep.

- Get outdoors for early morning light.

- Ask for help and delegate chores.

12. Other People

The final hazard is often the most familiar: Family tension is almost traditional. In one survey, 37% of people said Christmas "wouldn't be the same" without arguments, and 54% admitted enjoying them.

- Set boundaries and agree expectations early.

- Stick to a budget.

- Avoid known flashpoint topics, such as politics.

- Create a quiet space for time out.

- One in 9 people spend Christmas alone. Plan ahead to make it a special day.

The hazards may feel seasonal, but the outcomes are not. For clinicians, the 12 risks offer a reminder that small interventions before Christmas can prevent significant harm after it.

Dr Sheena Meredith is an established medical writer, editor, and consultant in healthcare communications, with extensive experience writing for medical professionals and the general public. She is qualified in medicine and in law and medical ethics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The carol promises partridges and pears. The reality, every December, is a predictable spike in injuries, illness, and emergency care.

Framed around the familiar “12 Days of Christmas,” this seasonal guide sets out the most common festive hazards — many of them preventable — and the practical advice clinicians can share to help patients enjoy a safer holiday.

1. Fire

Candles, open fires, and busy kitchens make December the most dangerous month for house fires. Home fires rise 10% in December and peak on Christmas Day at 53% above average, according to the National Fire Chiefs Council.

Alcohol, distraction, and festive cooking all add to the risk.

- Check for fire hazards before Christmas.

- Never leave cookers or candle unattended.

- Check Christmas lights and avoid overloading sockets.

- Ensure a working smoke alarm on each floor and keep escape routes clear.

- Remember that emollient residues on fabrics are highly flammable.

2. Christmas Trees and Decorations

Trees and trimmings bring their own risk. Christmas trees injure about 1000 people each year, according to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA).

A National Accident Helpline (NAH) survey found that 2.7% of respondents had experienced electric shock from faulty lights. Artificial trees, chosen by 76% of households, carry a sixfold higher injury risk. Real trees dry out and become highly flammable — “a giant bundle of kindling covered in electrical wires,” warned safety analysts TapRooT.

- Water live trees regularly — unplug lights first.

- Keep trees stable and at least 3 feet from heat sources.

- Switch off lights before bed or leaving the house.

- Do not hang stockings near open flames.

- Hang fragile decorations high up.

- Supervise children and pets.

3. Slips, Trips, and Falls

The third danger is underfoot. Falls, burns, and cuts send around 80,000 people to A&E each Christmas, according to RoSPA.

One in 50 people fall from their loft while retrieving decorations, the NAH warned.

- Use sturdy ladders and wear footwear with good grip.

- Keep floors clear of presents, wrapping, cables, and spills.

- Never melt ice with boiling water; refreezing can make surfaces more treacherous.

4. Food and Drug Interactions

Festive eating can interfere with medicines. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) warned that drug-food interactions are not always listed on packaging.

- Grapefruit interacts with multiple drugs.

- Cranberries can enhance warfarin's anticoagulant effect, while vitamin K-rich foods, including sprouts, may reduce it.

- Rich desserts can destabilize blood glucose.

- Tyramine-rich foods, including cheeses and dark chocolate, may trigger migraines or hypertensive crises with monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

5. Alcohol

Up to 70% of weekend A&E attendances are alcohol-related, with numbers rising over Christmas. The MHRA warned that mixing alcohol with medicines can cause drowsiness, impaired coordination, and accidents.

- Avoid drinking on an empty stomach.

- Be cautious of unfamiliar drinks.

- Alternate alcoholic and soft drinks.

- Avoid potentially aggressive intoxicated people.

6. Kitchen Calamities

The festive kitchen is a frequent source of injury. NAH data showed that 49% of people reported accidents while preparing Christmas food. Cuts accounted for 18%, and burns from hot fat 11%. In addition, the Food Standards Agency said that 46% of Christmas cooks do not check use-by dates.

- Keep children and trip hazards out of the kitchen.

- Use back hobs and turn saucepan handles inward.

- Never leave ovens or pans unattended.

- Discard out-of-date food.

- Refrigerate leftovers within 2 hours.

7. Children's Vulnerabilities

Christmas presents bring hidden dangers for children. Button batteries and magnets can inflict serious gastrointestinal damage if swallowed.

- Choose age-appropriate, well-made toys.

- Store batteries, magnets, medicines, and chemicals out of reach.

- Avoid sharp or breakable decorations.

- Place holly, mistletoe, and poinsettias well out of reach.

8. Eye Injuries

Eye injuries surge over Christmas. Champagne corks can travel at nearly 50 mph, risking globe rupture or retinal detachment.

Conifer needles, glitter, and artificial snow can all cause corneal injury.

- Point champagne bottles and party poppers away from people's faces.

- Take care when handling Christmas trees.

- Avoid hanging ornaments at children's eye level.

- Rinse glitter-contaminated eyes with sterile saline.

9. Existing Ailments

By the ninth day, routine has often collapsed. Festive excess, stress and disrupted schedules can destabilize chronic disease.

- Ensure adequate medicines and testing supplies.

- Let hosts know dietary needs in advance.

- Avoid excess salt and alcohol in cardiovascular disease, and excess potassium in kidney disease.

- Increase blood glucose monitoring in diabetes.

10. Presents

Not all gifts are benign. The Child Accident Prevention Trust warned that cheap or counterfeit products may bypass safety standards.

UK safety authorities report that counterfeit Labubu dolls have made up a large share of the roughly 259,000 counterfeit toys seized at UK borders this year, and many have failed safety tests.

- Be cautious when buying for toddlers.

- Look for recognized safety markings.

- Avoid toys with strong magnets or button batteries.

- Laser pointers can cause permanent damage to vision.

11. Stress

As Christmas approaches, pressure mounts. In an NAH survey, 12% of men and 20% of women said they felt rushed, 32% of women were stressed, and 18% overwhelmed.

- Prioritize sleep.

- Get outdoors for early morning light.

- Ask for help and delegate chores.

12. Other People

The final hazard is often the most familiar: Family tension is almost traditional. In one survey, 37% of people said Christmas "wouldn't be the same" without arguments, and 54% admitted enjoying them.

- Set boundaries and agree expectations early.

- Stick to a budget.

- Avoid known flashpoint topics, such as politics.

- Create a quiet space for time out.

- One in 9 people spend Christmas alone. Plan ahead to make it a special day.

The hazards may feel seasonal, but the outcomes are not. For clinicians, the 12 risks offer a reminder that small interventions before Christmas can prevent significant harm after it.

Dr Sheena Meredith is an established medical writer, editor, and consultant in healthcare communications, with extensive experience writing for medical professionals and the general public. She is qualified in medicine and in law and medical ethics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 12 Dangers of Christmas

The 12 Dangers of Christmas

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

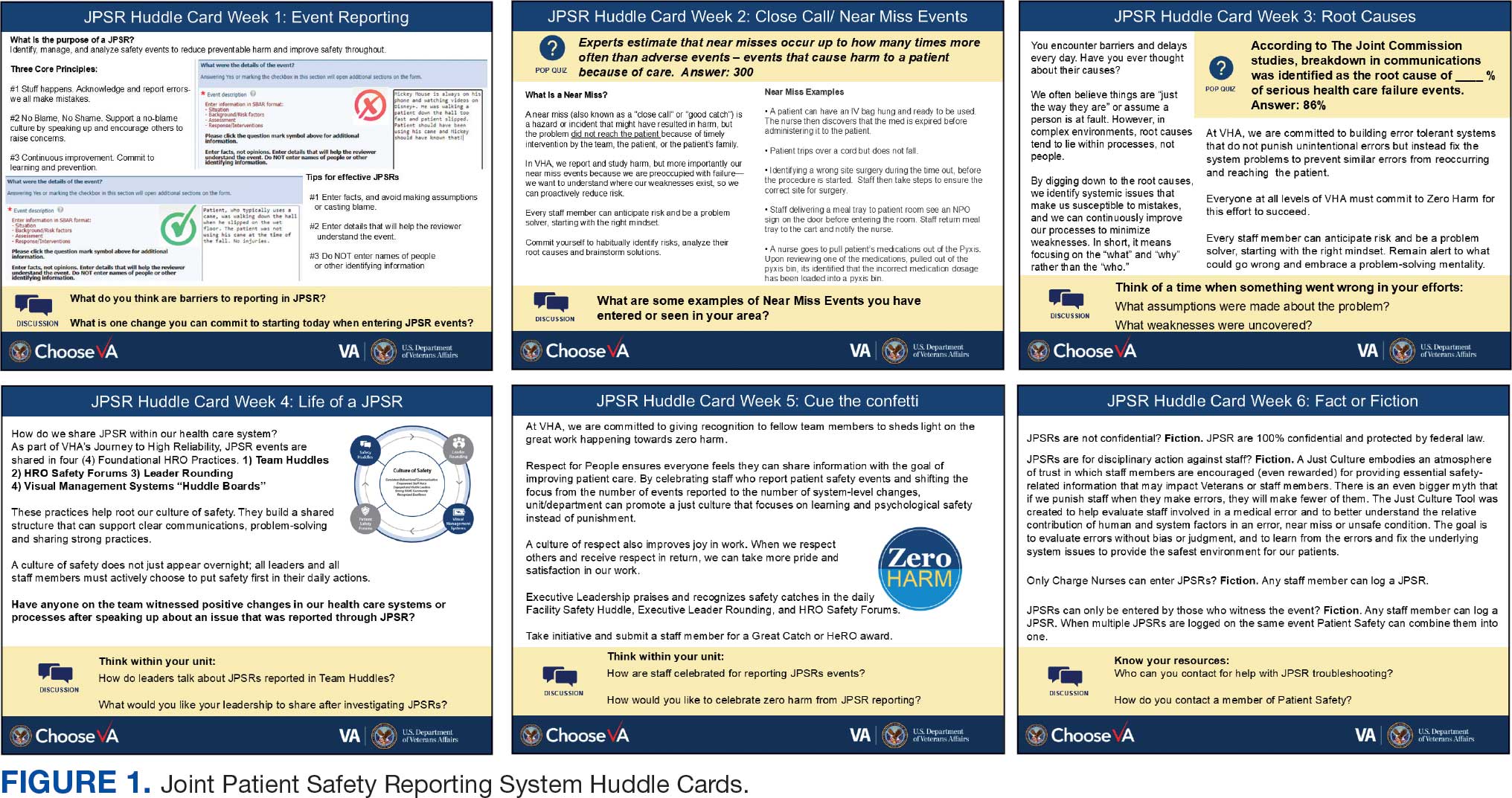

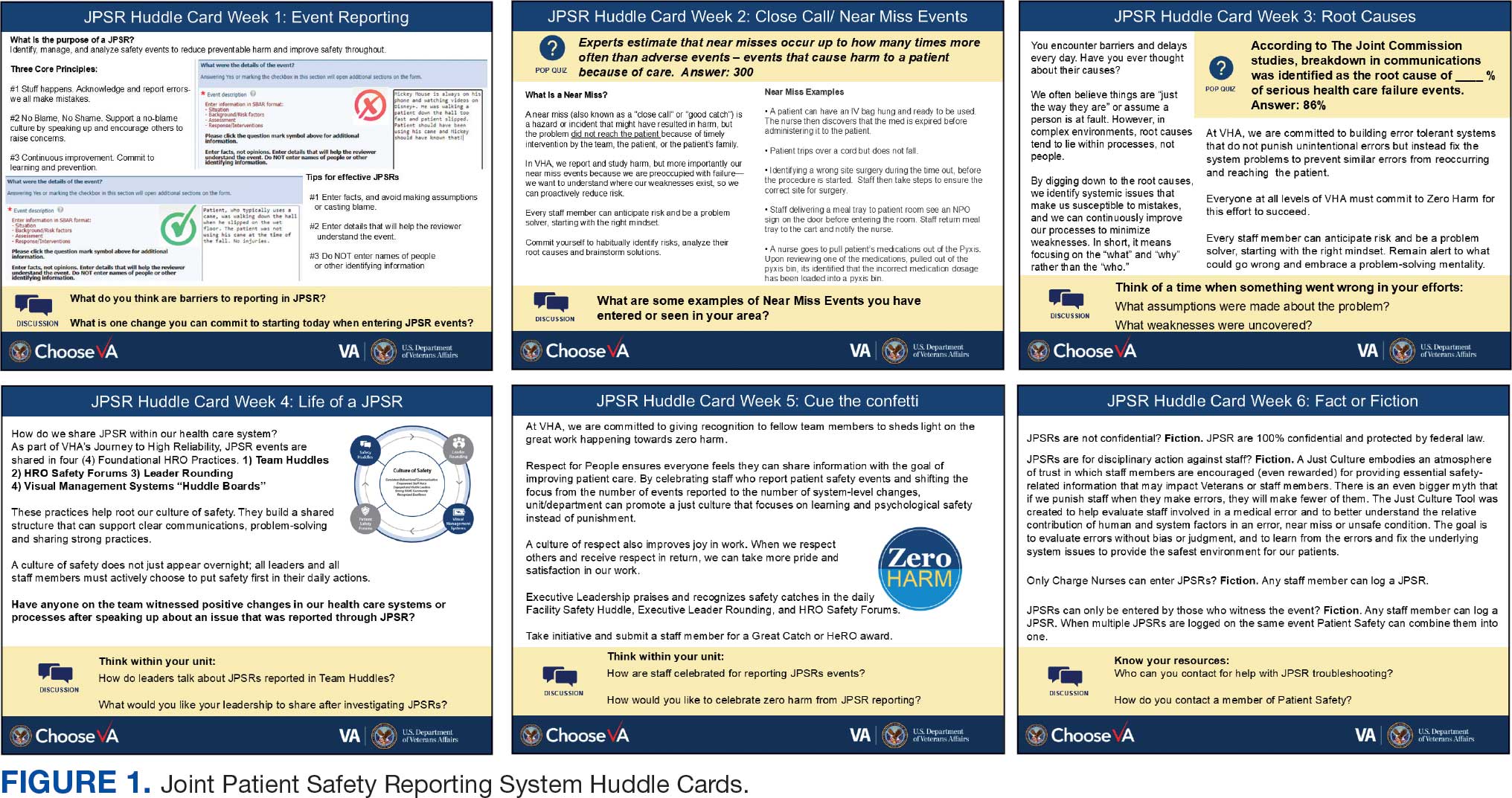

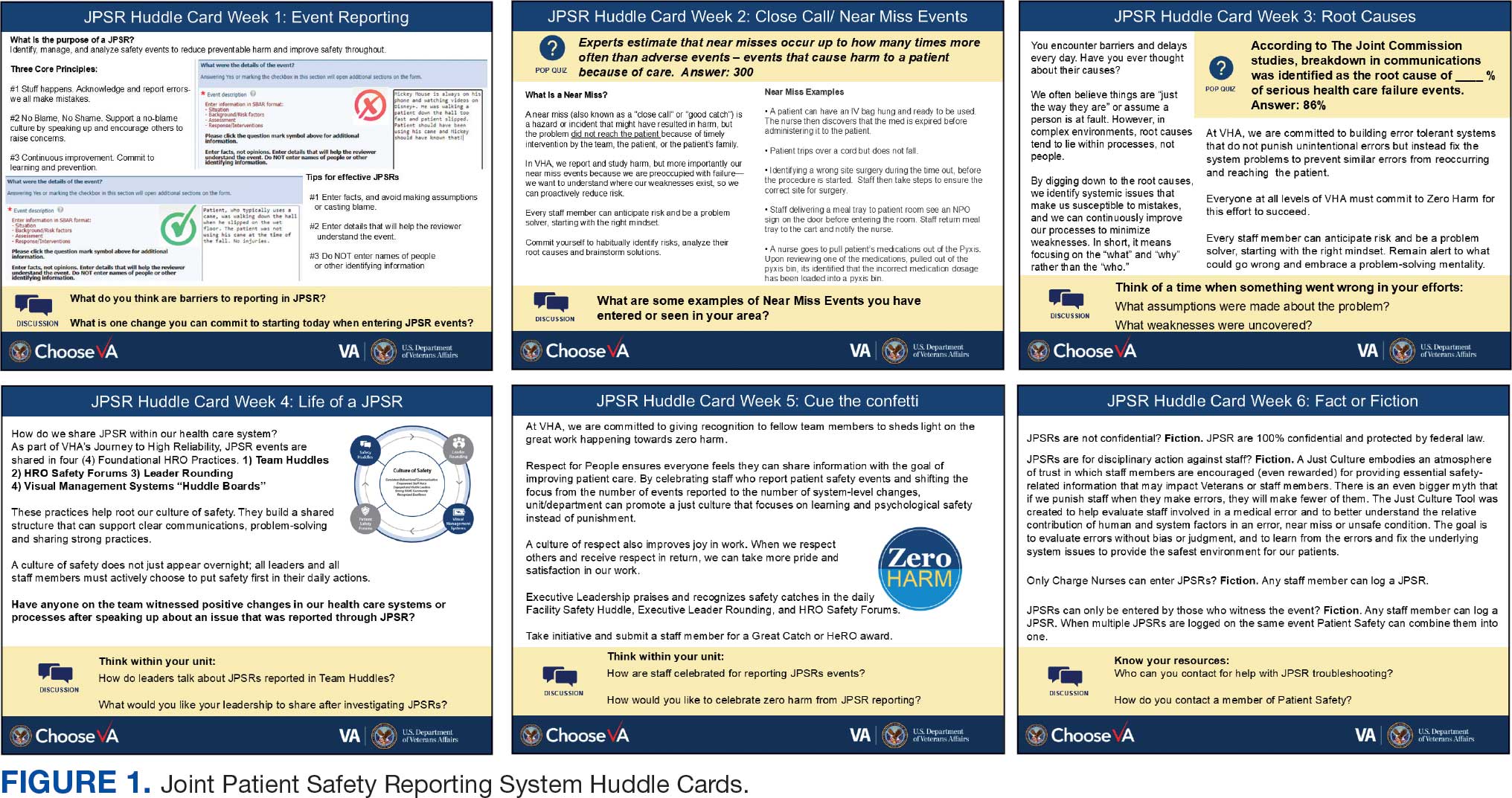

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

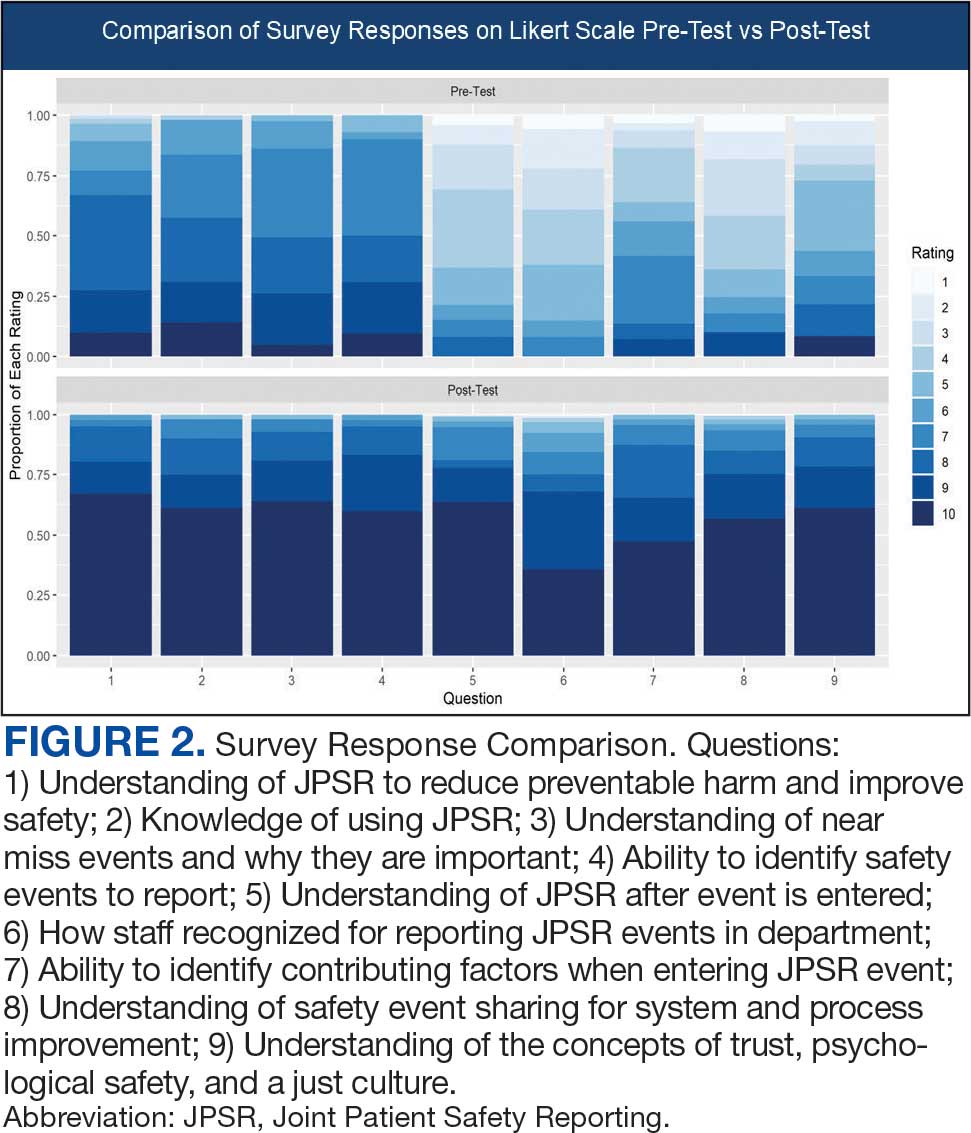

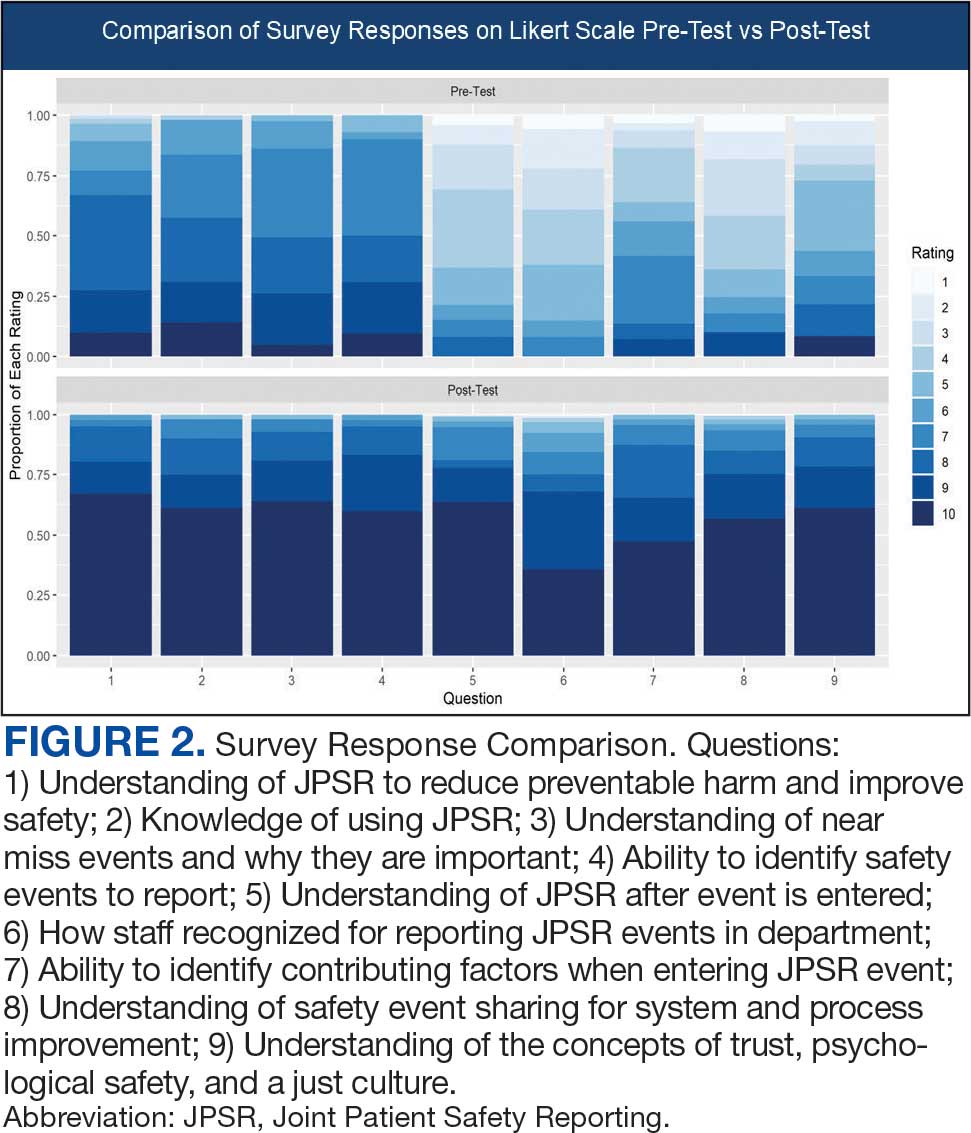

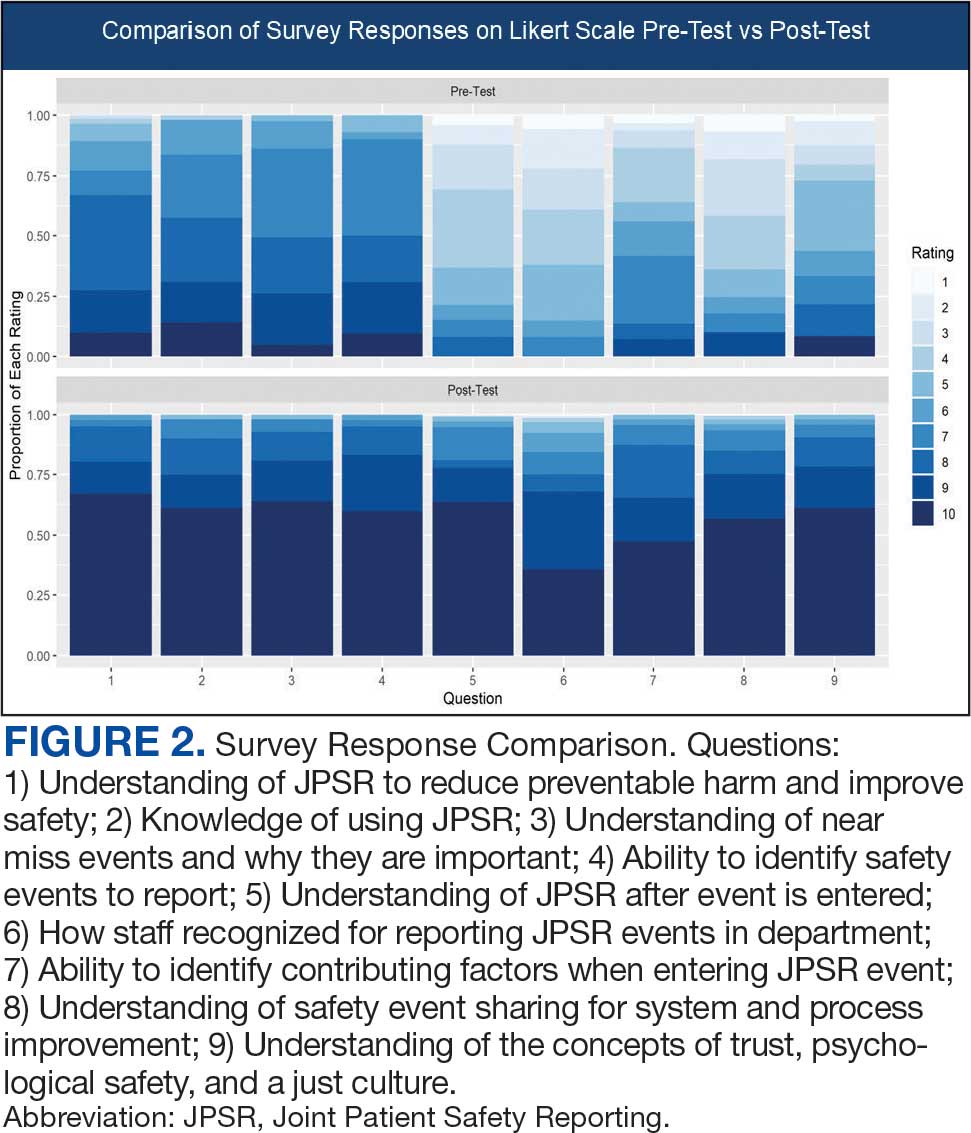

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Improved Pharmacogenomic Testing Process for Veterans in Outpatient Settings by Clinical Pharmacist Practitioners

Peer-review, evidence-based, detailed gene/drug clinical practice guidelines suggest that genetic variations can impact how individuals metabolize medications, which is sometimes included in medication prescribing information.1-3 Pharmacogenomic testing identifies genetic markers so medication selection and dosing can be tailored to each individual by identifying whether a specific medication is likely to be safe and effective prior to prescribing.4

Pharmacogenomics can be a valuable tool for personalizing medicine but has had suboptimal implementation since its discovery. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system reviewed the implementation of the Pharmacogenomic Testing for Veterans (PHASER) program. This review identified clinician barriers pre- and post-PHASER program implementation; staffing issues, competing clinical priorities, and inadequate PHASER program resources were the most frequently reported barriers to implementation of pharmacogenomic testing.5

Another evaluation of the implementation of the PHASER program that surveyed VA patients found that patients could be separated into 3 groups. Acceptors of pharmacogenomic testing emphasized potential health benefits of testing. Patients that declined testing often cited concerns for genetic information affecting insurance coverage, being misused, or being susceptible to data breach. The third group—identified as contemplators—reported the need for clinician outreach to impact their decision on whether or not to receive pharmacogenomic testing.6 These studies suggest that removing barriers by providing ample pharmacogenomics resources to clinicians, in addition to detailed training on how to offer and follow up with patients regarding pharmacogenomic testing, is crucial to successful implementation of the PHASER program.

PHASER

In 2019, the VA began working with Sanford Health to establish the PHASER program and offer pharmacogenomic testing. PHASER has since expanded to 25 VA medical centers, including the VA Central Ohio Healthcare System (VACOHCS).7,8 Pharmacogenomic testing through PHASER is conducted using a standardized laboratory panel that includes 12 different medication classes.9 The drug classes include certain anti-infective, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, cardiovascular, cholesterol, gastrointestinal, mental health, neurological, oncology, pain, transplant, and other miscellaneous medications. Medications are correlated to each class and assessed for therapeutic impacts based on gene panel results.

Clinical recommendations for medication-gene interactions can range from monitoring for increased risk of adverse effects or therapeutic failure to recommending avoiding a medication. For example, patients who test positive for the HLA-B gene have significantly increased risk of hypersensitivity to abacavir, an HIV treatment.10

Similarly, patients who cannot adequately metabolize cytochrome P450 2C19 should consider avoiding clopidogrel as they are unlikely to convert clopidogrel to its active prodrug, which reduces its effectiveness.11 Pharmacists can play a critical role educating patients about pharmacogenomic testing, especially within hematology and oncology.12 Patients can benefit from this testing even if they are not currently taking medications with known concerns as they could be prescribed in the future. The SLCO1B1 gene-drug test, for example, can identify risk for statin-associated muscle symptoms.13

Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) can increase access to genetic testing because they interact with patients in a variety of settings and can order this laboratory test.12,14 Recent research has demonstrated that most VA patients carry ≥ 1 genetic variant that may influence medication decisions and that half of veterans are prescribed a medication with known gene-drug interactions.15 CPP ordering of pharmacogenomic tests at the VACOHCS outpatient clinic was evaluated through collection of baseline data from March 8, 2023, to September 8, 2023. A goal was identified to increase orders by 50% for a patient care quality improvement initiative and use CPPs to increase access to pharmacogenomic testing. The purpose of this quality improvement initiative was to expand access to pharmacogenomic testing through process implementation and improvement within CPP-led clinic settings.

Gap Analysis

Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology was used to identify ways to increase the use of pharmacogenomic testing for veterans at VACOHCS and develop an improved process for increased ordering of pharmacogenomic testing. Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology is a stepwise approach to process improvement that helps identify gaps in efficiency, sustainable changes, and eliminate waste.16 Baseline data were collected from March 8, 2023, to September 8, 2023, to determine the frequency of CPPs ordering pharmacogenomic laboratory panels during clinic appointments. The ordering of pharmacogenomic panels was monitored by the VACOHCS PHASER coordinator.

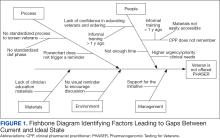

CPPs were surveyed to identify perceived barriers to PHASER implementation. A gap analysis was conducted using Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology. Gap analyses use lean tools such as a Fishbone Diagram to illustrate and identify the gap between current state and ideal state. (Figure 1).The following barriers were identified: lack of clinician education materials, lack of a standardized patient screening process, time constraints on patient education and ordering, higher priority clinical needs, forgetting to order, lack of comfort with pharmacogenomics ordering and education, lack of support for the initiative, and increased workload and burnout. Among these perceived barriers, higher priority clinical needs, forgetting to order, and time constraints ranked highest in importance among CPPs.

In line with Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology, several tests of change were used to improve pharmacogenomic testing ordering. These changes focused on increasing patient and clinician awareness, facilitating discussion, educating clinicians, and simplifying documentation to ease time constraints. Several strategies were employed postimplementation (Figure 2). Prefilled templates simplified documentation. These templates helped identify patients without pharmacogenomic testing, provided reminders, and saved documentation time during visits. CPPs also received training and materials on PHASER ordering and documentation within encounter notes. Additionally, patient-directed advertisements were displayed in CPP examination rooms to help inspire and facilitate discussion between veterans and CPPs.

Process Improvement Data

The quality improvement project goal was to increase PHASER orders by 50% after 3 months. PHASER orders increased from 87 at baseline (March 8, 2023, to September 8, 2023) to 196 during the intervention (November 16, 2023, to February 16, 2024), a 125% increase. Changes were consistent and sustained with 65 orders the first month, 67 orders the second month, and 64 orders the third month.

Discussion

Using Lean Six Sigma A3 methodology for a quality improvement process to increase PHASER orders by CPPs revealed barriers and guided potential solutions to overcome these barriers. Interventions included additional CPP training and ordering, tools for easier identification of potential patients, documentation best practices, patient-directed advertisements to facilitate conversations. These interventions required about 8 hours for preparation, distribution, development, and interpretation of surveys, education, and documentation materials. The financial impact of these interventions was already included in allotted office materials budgeted and provided. Additional funding was not needed to provide patient-directed advertisements or education materials. The VACOHCS pharmacogenomics CPP discusses PHASER test results with patients at a separate appointment.

Future directions include educating other CPPs to assist in discussing results with veterans. Overall, the changes implemented to improve the PHASER ordering process were low effort and exemplify the ease of streamlining future initiatives, allowing for sustained optimal implementation of pharmacogenomic testing.

Conclusions

A quality improvement initiative resulted in increased PHASER orders and a clearly defined process, allowing for a continued increase and sustained support. Perceived barriers were identified, and the changes implemented were often low effort but exhibited a sustained impact. The insights gleaned from this process will shape future process development initiatives and continue to sustain pharmacogenomic testing ordering by CPPs. This process will be extended to other VACOHCS clinical departments to further support increased access to pharmacogenomic testing, reduce medication trial and error, and reduce hospitalizations from adverse effects for veterans.

Cecchin E, Stocco G. Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine. Genes (Basel). 2020;11(6):679. doi:10.3390/genes11060679

Guidelines. CPIC. Accessed April 16, 2025. https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/

PharmGKB. PharmGKB. 2025. Accessed April 16, 2025. https://www.pharmgkb.org