User login

Seal of Approval

A report in this month's Journal of Hospital Medicine suggests that hospitals accredited by the Joint Commission outperform those that aren't when it comes to treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia.

The study, "Hospital Performance Trends on National Quality Measures and the Association with Joint Commission Accreditation," also found that over a five-year reporting period, accredited institutions improved more than their non-accredited counterparts. HM pioneer Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, was a coauthor of the study.

Joint Commission staffers and fellow coauthors Jerod Loeb, PhD, executive vice president of the Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation at the Joint Commission, and Stephen Schmaltz, MPH, PhD, associate director of the Department of Health Services Research, say that researchers were not able to compare hospitals based on accreditation and quality control until the commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted identical measures in 2004.

"We had a strong suspicion that accredited facilities would perform better, which was demonstrable in a statistically significant manner," Dr. Loeb says. "Of course, we worried that one of the questions that reviewers or others who read this might ask is, 'Sure, this is what we might expect from the Joint Commission to say that.' This is why the data is publically available, from us and CMS. Anyone can do the same type of analyses we’ve done and clearly come up with the very same conclusion.”

The next step of the research, Drs. Loeb and Schmaltz say, is to try to delineate whether the "gold seal" of accreditation is what "actually promotes improved performance or is a marker for other characteristics associated with such performance."

"There is something to this broad rubric associated with accreditation that is actually making a difference in the context of measures that matter...to clinical outcomes," Dr. Loeb adds. "This isn't the end of the game for us by any stretch of the imagination. It's clear that more research is needed."

A report in this month's Journal of Hospital Medicine suggests that hospitals accredited by the Joint Commission outperform those that aren't when it comes to treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia.

The study, "Hospital Performance Trends on National Quality Measures and the Association with Joint Commission Accreditation," also found that over a five-year reporting period, accredited institutions improved more than their non-accredited counterparts. HM pioneer Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, was a coauthor of the study.

Joint Commission staffers and fellow coauthors Jerod Loeb, PhD, executive vice president of the Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation at the Joint Commission, and Stephen Schmaltz, MPH, PhD, associate director of the Department of Health Services Research, say that researchers were not able to compare hospitals based on accreditation and quality control until the commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted identical measures in 2004.

"We had a strong suspicion that accredited facilities would perform better, which was demonstrable in a statistically significant manner," Dr. Loeb says. "Of course, we worried that one of the questions that reviewers or others who read this might ask is, 'Sure, this is what we might expect from the Joint Commission to say that.' This is why the data is publically available, from us and CMS. Anyone can do the same type of analyses we’ve done and clearly come up with the very same conclusion.”

The next step of the research, Drs. Loeb and Schmaltz say, is to try to delineate whether the "gold seal" of accreditation is what "actually promotes improved performance or is a marker for other characteristics associated with such performance."

"There is something to this broad rubric associated with accreditation that is actually making a difference in the context of measures that matter...to clinical outcomes," Dr. Loeb adds. "This isn't the end of the game for us by any stretch of the imagination. It's clear that more research is needed."

A report in this month's Journal of Hospital Medicine suggests that hospitals accredited by the Joint Commission outperform those that aren't when it comes to treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia.

The study, "Hospital Performance Trends on National Quality Measures and the Association with Joint Commission Accreditation," also found that over a five-year reporting period, accredited institutions improved more than their non-accredited counterparts. HM pioneer Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, was a coauthor of the study.

Joint Commission staffers and fellow coauthors Jerod Loeb, PhD, executive vice president of the Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation at the Joint Commission, and Stephen Schmaltz, MPH, PhD, associate director of the Department of Health Services Research, say that researchers were not able to compare hospitals based on accreditation and quality control until the commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted identical measures in 2004.

"We had a strong suspicion that accredited facilities would perform better, which was demonstrable in a statistically significant manner," Dr. Loeb says. "Of course, we worried that one of the questions that reviewers or others who read this might ask is, 'Sure, this is what we might expect from the Joint Commission to say that.' This is why the data is publically available, from us and CMS. Anyone can do the same type of analyses we’ve done and clearly come up with the very same conclusion.”

The next step of the research, Drs. Loeb and Schmaltz say, is to try to delineate whether the "gold seal" of accreditation is what "actually promotes improved performance or is a marker for other characteristics associated with such performance."

"There is something to this broad rubric associated with accreditation that is actually making a difference in the context of measures that matter...to clinical outcomes," Dr. Loeb adds. "This isn't the end of the game for us by any stretch of the imagination. It's clear that more research is needed."

QI-Focused Microsite Aims to Educate Hospitalists

Gregory Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, has high hopes for SHM's new Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. Dr. Maynard, recently appointed senior vice president of "The Center," believes The Center's tools, resources, and initiatives in QI and patient safety will advance hospitalists' understanding of the implications of healthcare reform and how recent legislative changes will directly affect their jobs.

Through its Web portal, The Center aims to bring together a wide variety of resources, not only such SHM-branded initiatives as VTE Prevention and Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), but also relevant tools from other sources.

"The Center has grown because there's a bigger demand all the time for the skills, knowledge, and leadership required for quality and patient safety," Dr. Maynard says. "We recognize that frontline hospitalists are very busy with day-to-day clinical care. On the other hand, quality and safety efforts increasingly will be tied to hospital reimbursement."

Hospital administrators are paying attention to those trends, and hospitalists are well situated to lead their response, he adds.

New quality developments at the center include:

- eQUIPS, SHM’s online toolkit for hospital QI, with a data registry and tools for comparing performance with other hospitals;

- Hospitalists and In-Hospital Resuscitation, a multidisciplinary project for standardizing resuscitation practice;

- A new initiative for atrial fibrillation and transitions of care; and

- In-hospital best practices in diabetes care for hospitalist extenders.

Dr. Maynard is director of hospital medicine and chair of the Patient Safety Committee at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). He expects to spend one week per month at SHM's Philadelphia office while retaining his leadership position at UCSD.

Gregory Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, has high hopes for SHM's new Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. Dr. Maynard, recently appointed senior vice president of "The Center," believes The Center's tools, resources, and initiatives in QI and patient safety will advance hospitalists' understanding of the implications of healthcare reform and how recent legislative changes will directly affect their jobs.

Through its Web portal, The Center aims to bring together a wide variety of resources, not only such SHM-branded initiatives as VTE Prevention and Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), but also relevant tools from other sources.

"The Center has grown because there's a bigger demand all the time for the skills, knowledge, and leadership required for quality and patient safety," Dr. Maynard says. "We recognize that frontline hospitalists are very busy with day-to-day clinical care. On the other hand, quality and safety efforts increasingly will be tied to hospital reimbursement."

Hospital administrators are paying attention to those trends, and hospitalists are well situated to lead their response, he adds.

New quality developments at the center include:

- eQUIPS, SHM’s online toolkit for hospital QI, with a data registry and tools for comparing performance with other hospitals;

- Hospitalists and In-Hospital Resuscitation, a multidisciplinary project for standardizing resuscitation practice;

- A new initiative for atrial fibrillation and transitions of care; and

- In-hospital best practices in diabetes care for hospitalist extenders.

Dr. Maynard is director of hospital medicine and chair of the Patient Safety Committee at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). He expects to spend one week per month at SHM's Philadelphia office while retaining his leadership position at UCSD.

Gregory Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, has high hopes for SHM's new Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. Dr. Maynard, recently appointed senior vice president of "The Center," believes The Center's tools, resources, and initiatives in QI and patient safety will advance hospitalists' understanding of the implications of healthcare reform and how recent legislative changes will directly affect their jobs.

Through its Web portal, The Center aims to bring together a wide variety of resources, not only such SHM-branded initiatives as VTE Prevention and Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), but also relevant tools from other sources.

"The Center has grown because there's a bigger demand all the time for the skills, knowledge, and leadership required for quality and patient safety," Dr. Maynard says. "We recognize that frontline hospitalists are very busy with day-to-day clinical care. On the other hand, quality and safety efforts increasingly will be tied to hospital reimbursement."

Hospital administrators are paying attention to those trends, and hospitalists are well situated to lead their response, he adds.

New quality developments at the center include:

- eQUIPS, SHM’s online toolkit for hospital QI, with a data registry and tools for comparing performance with other hospitals;

- Hospitalists and In-Hospital Resuscitation, a multidisciplinary project for standardizing resuscitation practice;

- A new initiative for atrial fibrillation and transitions of care; and

- In-hospital best practices in diabetes care for hospitalist extenders.

Dr. Maynard is director of hospital medicine and chair of the Patient Safety Committee at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). He expects to spend one week per month at SHM's Philadelphia office while retaining his leadership position at UCSD.

Frequent Hot Flashes? Check Lipid Levels

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. – Frequent hot flashes in menopausal women were significantly associated with higher levels of low-density lipoproteins, high-density lipoproteins, and triglycerides during a 7-year follow-up study of 3,201 women enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study.

Women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes or 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of LDL cholesterol.

Previous investigations using the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) database have shown that women with more hot flashes have an elevated risk for subclinical cardiovascular disease, said Rebecca Thurston, Ph.D., of the University of Pittsburgh. But "there is a lot we don’t know about this association, including what could possibly explain this," she said at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Dr. Thurston and colleagues examined hot flashes as they related to lipid profiles in women enrolled in SWAN. The subjects’ median age was 46 years, 48% were white, 46% were in early or perimenopause, and 26% reported hot flashes within the past two weeks.

Hot flashes were analyzed in relation to six lipid profiles, after controlling for age, race, menopausal status/cycle day, alcohol use, physical activity, smoking, anxiety, body mass index, cardiovascular disease status and medications, lipid lowering medications, and estradiol.

Compared to women who reported no hot flashes, women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes or 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, and apolipoprotein A1. For example, LDL levels among women with 6 or more days of hot flashes peaked at approximately 125 mg/dL during a 2-week period, compared with a peak of approximately 120 mg/dL among women with 1-5 days of hot flashes and a peak of approximately 118 mg/dL among women with no reported days of hot flashes.

Levels of HDL cholesterol were significantly higher in women who reported 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks, compared with those who reported no hot flashes, but HDL levels were not significantly different between women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes and those who reported no hot flashes.

By contrast, levels of lipoprotein(a) were not significantly different among women who reported no hot flashes, women who reported 1 to 5 days of hot flashes, and women who reported 6 or more days of hot flashes.

The positive relationships between hot flashes and lipoprotein(a), and between hot flashes and HDL in some women, were surprising, Dr. Thurston said. "The cardioprotective nature of HDL may depend on particle size," she noted. HDL particles become smaller as women transition through menopause, she added, which might explain the differences.

Additional studies are needed to address the findings on HDL and lipoprotein(a) and to explore how vasomotor symptoms may provide additional information about women’s vascular health, Dr. Thurston said. Future studies should be designed with improved measures of vasomotor symptoms, she added.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston had no financial conflicts to disclose.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. – Frequent hot flashes in menopausal women were significantly associated with higher levels of low-density lipoproteins, high-density lipoproteins, and triglycerides during a 7-year follow-up study of 3,201 women enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study.

Women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes or 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of LDL cholesterol.

Previous investigations using the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) database have shown that women with more hot flashes have an elevated risk for subclinical cardiovascular disease, said Rebecca Thurston, Ph.D., of the University of Pittsburgh. But "there is a lot we don’t know about this association, including what could possibly explain this," she said at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Dr. Thurston and colleagues examined hot flashes as they related to lipid profiles in women enrolled in SWAN. The subjects’ median age was 46 years, 48% were white, 46% were in early or perimenopause, and 26% reported hot flashes within the past two weeks.

Hot flashes were analyzed in relation to six lipid profiles, after controlling for age, race, menopausal status/cycle day, alcohol use, physical activity, smoking, anxiety, body mass index, cardiovascular disease status and medications, lipid lowering medications, and estradiol.

Compared to women who reported no hot flashes, women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes or 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, and apolipoprotein A1. For example, LDL levels among women with 6 or more days of hot flashes peaked at approximately 125 mg/dL during a 2-week period, compared with a peak of approximately 120 mg/dL among women with 1-5 days of hot flashes and a peak of approximately 118 mg/dL among women with no reported days of hot flashes.

Levels of HDL cholesterol were significantly higher in women who reported 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks, compared with those who reported no hot flashes, but HDL levels were not significantly different between women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes and those who reported no hot flashes.

By contrast, levels of lipoprotein(a) were not significantly different among women who reported no hot flashes, women who reported 1 to 5 days of hot flashes, and women who reported 6 or more days of hot flashes.

The positive relationships between hot flashes and lipoprotein(a), and between hot flashes and HDL in some women, were surprising, Dr. Thurston said. "The cardioprotective nature of HDL may depend on particle size," she noted. HDL particles become smaller as women transition through menopause, she added, which might explain the differences.

Additional studies are needed to address the findings on HDL and lipoprotein(a) and to explore how vasomotor symptoms may provide additional information about women’s vascular health, Dr. Thurston said. Future studies should be designed with improved measures of vasomotor symptoms, she added.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston had no financial conflicts to disclose.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. – Frequent hot flashes in menopausal women were significantly associated with higher levels of low-density lipoproteins, high-density lipoproteins, and triglycerides during a 7-year follow-up study of 3,201 women enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study.

Women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes or 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of LDL cholesterol.

Previous investigations using the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) database have shown that women with more hot flashes have an elevated risk for subclinical cardiovascular disease, said Rebecca Thurston, Ph.D., of the University of Pittsburgh. But "there is a lot we don’t know about this association, including what could possibly explain this," she said at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Dr. Thurston and colleagues examined hot flashes as they related to lipid profiles in women enrolled in SWAN. The subjects’ median age was 46 years, 48% were white, 46% were in early or perimenopause, and 26% reported hot flashes within the past two weeks.

Hot flashes were analyzed in relation to six lipid profiles, after controlling for age, race, menopausal status/cycle day, alcohol use, physical activity, smoking, anxiety, body mass index, cardiovascular disease status and medications, lipid lowering medications, and estradiol.

Compared to women who reported no hot flashes, women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes or 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks were significantly more likely to have elevated levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, and apolipoprotein A1. For example, LDL levels among women with 6 or more days of hot flashes peaked at approximately 125 mg/dL during a 2-week period, compared with a peak of approximately 120 mg/dL among women with 1-5 days of hot flashes and a peak of approximately 118 mg/dL among women with no reported days of hot flashes.

Levels of HDL cholesterol were significantly higher in women who reported 6 or more days of hot flashes during the past 2 weeks, compared with those who reported no hot flashes, but HDL levels were not significantly different between women who reported 1-5 days of hot flashes and those who reported no hot flashes.

By contrast, levels of lipoprotein(a) were not significantly different among women who reported no hot flashes, women who reported 1 to 5 days of hot flashes, and women who reported 6 or more days of hot flashes.

The positive relationships between hot flashes and lipoprotein(a), and between hot flashes and HDL in some women, were surprising, Dr. Thurston said. "The cardioprotective nature of HDL may depend on particle size," she noted. HDL particles become smaller as women transition through menopause, she added, which might explain the differences.

Additional studies are needed to address the findings on HDL and lipoprotein(a) and to explore how vasomotor symptoms may provide additional information about women’s vascular health, Dr. Thurston said. Future studies should be designed with improved measures of vasomotor symptoms, she added.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE NORTH AMERICAN MENOPAUSE SOCIETY

Major Finding: LDL levels among women with 6 or more days of hot flashes peaked at approximately 125 mg/dL during a 2-week period, compared with a peak of approximately 120 mg/dL among women with 1-5 days of hot flashes and a peak of approximately 118 mg/dL among women with no reported days of hot flashes.

Data Source: Data from 3,201 women enrolled in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN).

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Reliability of CXR for Pneumonia

The chest radiograph (CXR) is the most commonly used diagnostic imaging modality in children, and is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia. As such, physicians in developed countries rely on chest radiography to establish the diagnosis of pneumonia.13 However, there are limited data investigating the reliability of this test for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children.2, 46

Prior investigations have noted poor overall agreement by emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and pulmonary medicine physicians, and even radiologists, in their interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia.2, 5, 710 The World Health Organization (WHO) developed criteria to standardize CXR interpretation for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children for use in epidemiologic studies.11 These standardized definitions of pneumonia have been formally evaluated by the WHO6 and utilized in epidemiologic studies of vaccine efficacy,12 but the overall reliability of these radiographic criteria have not been studied outside of these forums.

We conducted this prospective case‐based study to evaluate the reliability of the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia among children presenting to a pediatric emergency department with clinical suspicion of pneumonia. We were primarily interested in assessing the overall reliability in CXR interpretation for the diagnosis of pneumonia, and identifying which radiographic features of pneumonia were consistently identified by radiologists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

We evaluated the reliability of CXR interpretation with respect to the diagnosis of pneumonia among radiologists. Six board‐certified radiologists at 2 academic children's hospitals (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA [n = 3] and Children's Hospital, Boston, Boston, MA [n = 3]) interpreted the same 110 chest radiographs in a blinded fashion. The radiologists varied with respect to the number of years practicing pediatric radiology (median 8 years, range 3‐36 years). Clinical information such as age, gender, clinical indication for obtaining the radiograph, history, and physical examination findings were not provided. Aside from the study form which stated the WHO classification scheme for radiographic pneumonia, no other information or training was provided to the radiologists as part of this study.

Radiographs were selected among a population of children presenting to the emergency department at Children's Hospital, Boston, who had a radiograph obtained for concern of pneumonia. From this cohort, we selected children who had radiographs which encompassed the spectrum of respiratory disease processes encountered in a pediatric population. The radiographs selected for review included 50 radiographs with a final reading in the medical record without suspicion for pneumonia, and 50 radiographs in which the diagnosis of pneumonia could not be excluded. In the latter group, 25 radiographs had a final reading suggestive of an alveolar infiltrate, and 25 radiographs had a final reading suggestive of an interstitial infiltrate. Ten duplicate radiographs were included to permit assessment of intra‐rater reliability.

Radiograph Interpretation

Radiologists at both sites interpreted the identical 110 radiographs (both anteroposterior [AP] and lateral views for each subject). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) images were downloaded from a registry at Children's Hospital, Boston, and were copied to DVDs which were provided to each radiologist. Standardized radiographic imaging software (eFilm Lite [Mississauga, Canada]) was used by each radiologist to view and interpret the radiographs.

Each radiologist completed a study questionnaire for each radiograph interpreted (see Supporting Appendix A in the online version of this article). The questionnaire utilized radiographic descriptors of primary end‐point pneumonia described by the WHO which were procured to standardize the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia.11, 12 The main outcome of interest was the presence or absence of an infiltrate. Among radiographs in which an infiltrate was identified, radiologists selected whether there was an alveolar infiltrate, interstitial infiltrate, or both. An alveolar infiltrate was defined as a dense or fluffy opacity that occupies a portion or whole of a lobe, or of the entire lung, that may or may not contain air bronchograms.11, 12 An interstitial infiltrate was defined by a lacy pattern involving both lungs, featuring peribronchial thickening and multiple areas of atelectasis.11, 12 It also included minor patchy infiltrates that were not of sufficient magnitude to constitute consolidation, and small areas of atelectasis that in children may be difficult to distinguish from consolidation. Among interstitial infiltrates, radiologists were asked to distinguish infiltrate from atelectasis. A radiograph classified as having either an alveolar infiltrate or interstitial infiltrate (not atelectasis) was considered to have any infiltrate. Additional findings including air bronchograms, hilar adenopathy, pleural effusion, and location of abnormalities were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Inter‐rater reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic to determine the overall agreement between the 6 radiologists for each binary outcome (ie, presence or absence of alveolar infiltrate). To calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for kappa statistics with more than 2 raters, we employed a bootstrapping method with 1000 replications of samples equal in size to the study sample, using the kapci program as implemented by STATA software (version 10.1, STATA Corp, College Station, TX). Also, intra‐rater reliability was evaluated by examining the agreement within each radiologist upon review of 10 duplicate radiographs that had been randomly inserted into the case‐mix. We used the benchmarks proposed by Landis and Koch to classify the strength of agreement measured by the kappa statistic, as follows: poor (<0.0); slight (0‐0.20); fair (0.21‐0.40); moderate (0.41‐0.60); substantial (0.61‐0.80); almost perfect (0.81‐1.0).13

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Children's Hospital, Boston and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

RESULTS

Patient Sample

The sample of 110 radiographs was obtained from 100 children presenting to the emergency department at Children's Hospital, Boston, with concern of pneumonia. These patients ranged in age from 1 week to 19 years (median, 3.5 years; interquartile range [IQR], 1.6‐6.0 years). Fifty (50%) of these patients were male. As stated above, the sample comprised 50 radiographs with a final reading in the medical record without suspicion for pneumonia, and 50 radiographs in which the diagnosis of pneumonia could not be excluded. The 10 duplicate radiographs encompassed a similar spectrum of findings.

Inter‐Rater Reliability

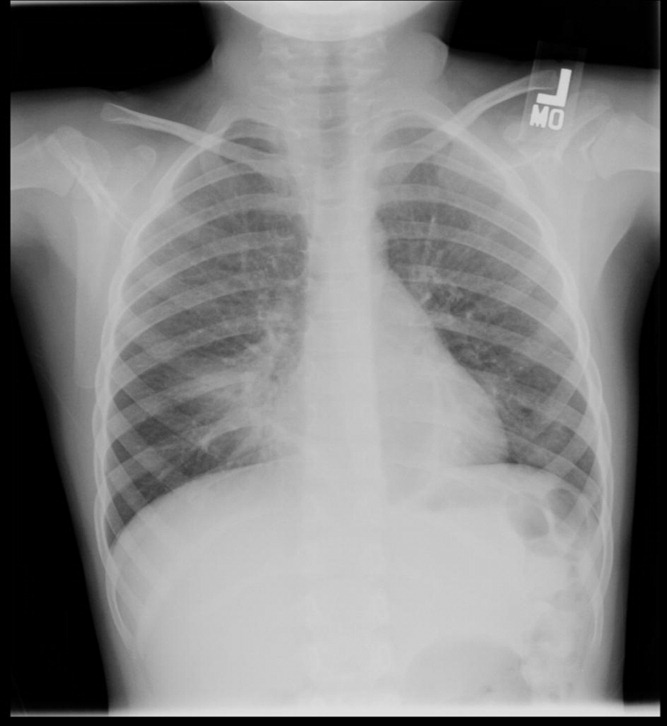

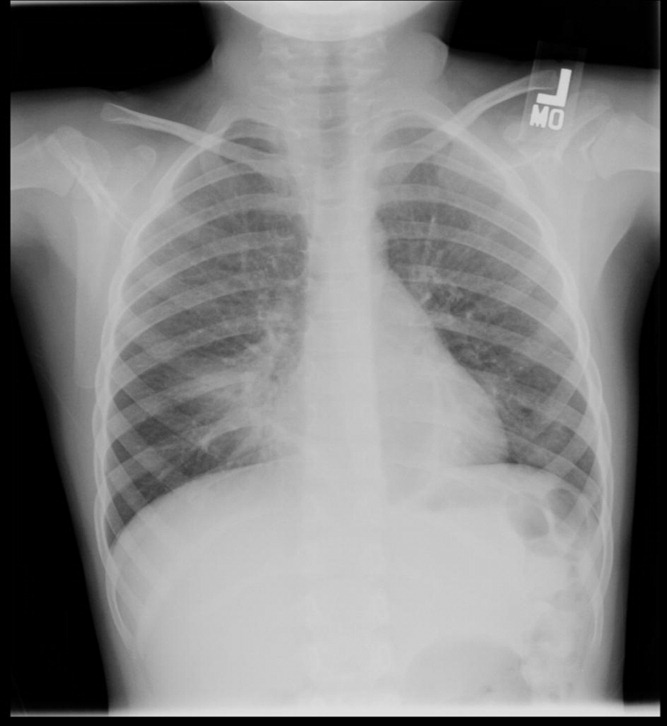

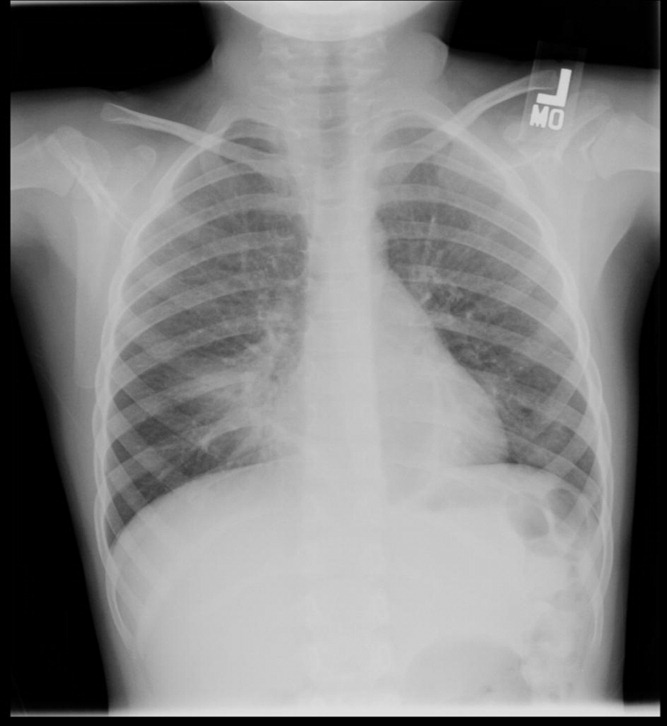

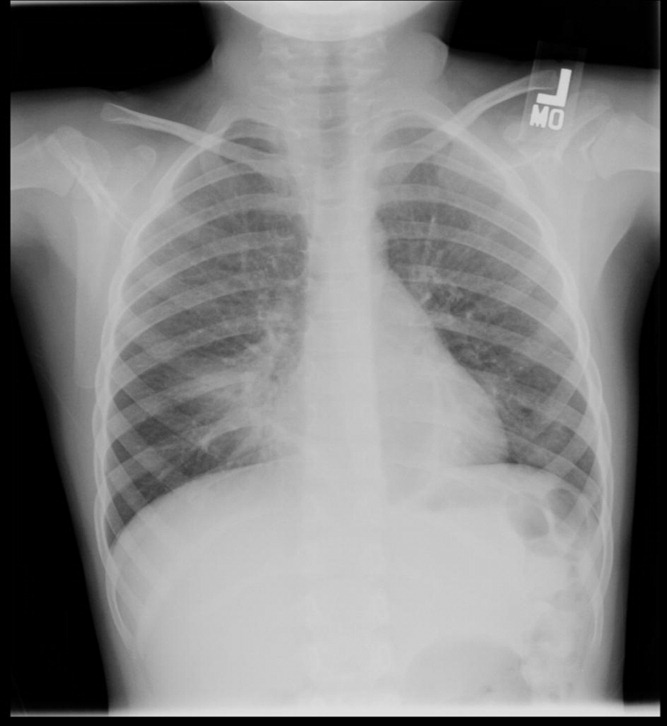

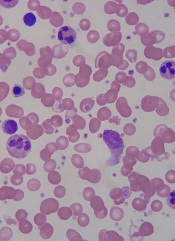

The kappa coefficients of inter‐rater reliability between the radiologists across the 6 clinical measures of interest are displayed in Table 1. As shown, the most reliable measure was that of alveolar infiltrate (Figure 1), which attained a substantial degree of agreement between the radiologists. Two other measures, any infiltrate and pleural effusion, attained moderate reliability, while bronchograms and hilar adenopathy were each classified as having fair reliability. However, interstitial infiltrate (Figure 2) was found to have the lowest kappa estimate, with a slight degree of reliability. When examining inter‐rater reliability among the radiologists separately from each institution, the pattern of results was similar.

| All Radiologists (n = 6) | Kappa | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Any infiltrate | 0.47 | 0.39, 0.56 |

| Alveolar infiltrate | 0.69 | 0.60, 0.78 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | 0.14 | 0.05, 0.23 |

| Air bronchograms | 0.32 | 0.24, 0.42 |

| Hilar adenopathy | 0.21 | 0.08, 0.39 |

| Pleural effusion | 0.45 | 0.29, 0.61 |

At least 4 of the 6 radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of an alveolar infiltrate for 95 of the 100 unique CXRs; all 6 radiologists agreed regarding the presence or absence of an alveolar infiltrate in 72 of the 100 unique CXRs. At least 4 of the 6 radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of any infiltrate and interstitial infiltrate 96% and 90% of the time, respectively. All 6 of the radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of any infiltrate and interstitial infiltrate 35% and 27% of the time, respectively.

Intra‐Rater Reliability

Estimates of intra‐rater reliability on the primary clinical outcomes (alveolar infiltrate, interstitial infiltrate, and any infiltrate) are found in Table 2. Across the 6 raters, the kappa estimates for alveolar infiltrate were all classified as substantial or almost perfect. The kappa estimates for interstitial infiltrate varied widely, ranging from fair to almost perfect, while for any infiltrate, reliability ranged from moderate to almost perfect.

| Kappa | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Any infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.60 | 0.10, 1.00 |

| Rater 3 | 0.80 | 0.44, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 5 | n/a* | |

| Rater 6 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Alveolar infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 3 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 5 | 0.78 | 0.39, 1.00 |

| Rater 6 | 0.74 | 0.27, 1.00 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.21 | 0.43, 0.85 |

| Rater 3 | 0.74 | 0.27, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | n/a | |

| Rater 5 | 0.58 | 0.07, 1.00 |

| Rater 6 | 0.62 | 0.5, 1.00 |

DISCUSSION

The chest radiograph serves as an integral component of the reference standard for the diagnosis of childhood pneumonia. Few prior studies have assessed the reliability of chest radiograph findings in children.3, 5, 12, 14, 15 We found a high degree of agreement among radiologists for radiologic findings consistent with bacterial pneumonia when standardized interpretation criteria were applied. In this study, we identified radiographic features of pneumonia, such as alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion, that were consistently identified by different radiologists reviewing the same radiograph and by the same radiologist reviewing the same radiograph. These data support the notion that radiographic features most suggestive of bacterial pneumonia are consistently identified by radiologists.16, 17 There was less consistency in the identification of other radiographic findings, such as interstitial infiltrates, air bronchograms, and hilar lymphadenopathy.

Prior studies have found high levels of disagreement among radiologists in the interpretation of chest radiographs.2, 3, 15, 18 Many of these prior studies emphasized variation in detection of radiographic findings that would not typically alter clinical management. We observed high intra‐rater, and inter‐rater reliability among radiologists for the findings of alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion. These are the radiographic findings most consistent with a bacterial etiologic agent for pneumonia.19 Other studies have also found that the presence of an alveolar infiltrate is a reliable radiographic finding in children18 and adults.7, 9, 10 These findings support the use of the WHO definition of primary endpoint pneumonia for use in epidemiologic studies.4, 6, 11

This study also confirms a previous report by Cherian et al. that findings of many children with asthma, reactive airways disease, bronchiolitis, and viral infections interstitial infiltrates are less reliable.6 This is not surprising considering the fact that these patients often have radiographic findings due to small airway disease and atelectasis.19, 20 The differentiation between atelectasis and interstitial infiltrate is difficult, particularly in young children. A prior study conducted among neonates observed wide variability in the interpretation of chest radiographs, and that the differentiation of pneumonia from atelectasis was difficult for this patient population.5 The decisions around antimicrobial treatment of children with radiographic findings of interstitial infiltrates should be made in the context of the clinical history and physical examination findings, and clinicians should realize that these radiographic features demonstrate poor reliability for the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Overall reliability for the presence of any infiltrate, and its converse, no infiltrate was considered moderate. This is driven by the low reliability and variability around the radiographic diagnosis of interstitial infiltrates. Our findings are similar to those observed in adults with lower respiratory tract infections.9 The low reliability in identification of interstitial infiltrates may explain why prior studies have demonstrated that the CXR results rarely change management in children who have radiographs performed for suspicion of pneumonia.1, 21 Our study highlights the importance of quantifying CXR findings to include specific comments regarding the presence or absence of alveolar infiltrates, rather than the presence or absence of any infiltrate.

The WHO has procured definitions the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia, and this definition has been utilized to help standardize the interpretation of chest radiographs for the conduct of epidemiological studies.6, 11 Specifically, the definitions utilized not only define the presence or absence of pneumonia, but also attempt to differentiate a primarily bacterial infection (consolidation or pleural effusion), from a viral or atypical presentation (interstitial pattern). Even under the best of circumstances, the differentiation of viral versus bacterial pneumonia is not always possible, and again, is often made by the treating physician by incorporating the clinical setting within which the radiograph was obtained.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the included radiographs did not reflect the frequency with which certain radiographic findings would be identified in children evaluated for pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department setting. Radiographs were purposefully selected to encompass a broad spectrum of radiologic findings, including less common findings such as hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions. Thus, the prevalence of pneumonia and other abnormal findings in this study was artificially higher than typically observed among a cohort of children for whom pneumonia is considered, a factor that may limit the generalizability of our results. Secondly, the clinical history was not provided to the radiologists to avoid bias by indication. For this study, we notified the radiologists that all radiographs were performed for clinical suspicion of pneumonia without providing details about the subjects' signs and symptoms. The absence of clinical history, however, does not mirror the real world scenario in which the interpretation of the chest radiograph is frequently made in the context of the clinical history. The relevance of this latter issue is unclear, as Tudor et al. found a nonstatistically significant improvement in the overall accuracy in chest radiograph interpretation when radiologists were provided clinical details.10 The radiologists recruited for this study all practice in an academic children's hospital setting, and thus, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to this type of practice setting. Finally, reproducibility does not imply accuracy, and reliability in identifying specific findings does not necessarily lead to improved or different management. Thus, while the reliability of radiographic findings of alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion is reassuringly high, the validity of these radiographic features for bacterial pneumonia is not known. Ascertainment of validity can only be assessed through the use of invasive testing such as lung biopsy, as the yield from bacterial testing such as blood cultures is low, and the results of other studies such as viral testing of nasopharyngeal washings do not prove an etiologic cause of pneumonia.

CONCLUSIONS

Radiographic findings of alveolar infiltrates and pleural effusions are highly reliable among radiologists. Radiographic interpretation of interstitial infiltrates appears to be less reliable.

- ,,, et al.Usefulness of chest radiographs in children with acute lower respiratory tract disease.J Pediatr.1987;111:187–193.

- ,,, et al.Disagreement in the interpretation of chest radiographs among specialists and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with suspected pneumonia.Eur J Intern Med.2006;17:43–47.

- ,,.Problems in the clinical and roentgenographic diagnosis of pneumonia in young children.Clin Pediatr (Phila).1984;23:398–399.

- WHO guidelines on detecting pneumonia in children.Lancet.1991;338:1453–1454.

- ,,, et al.Inter‐ and intra‐observer variability in the assessment of atelectasis and consolidation in neonatal chest radiographs.Pediatr Radiol.1999;29:459–462.

- ,,, et al.Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies.Bull World Health Organ.2005;83:353–359.

- ,,, et al.Interobserver reliability of the chest radiograph in community‐acquired pneumonia. PORT Investigators.Chest.1996;110:343–350.

- ,,, et al.Chest radiographs in the emergency department: is the radiologist really necessary?Postgrad Med J.2003;79:214–217.

- ,,, et al.Inter‐observer variation in the interpretation of chest radiographs for pneumonia in community‐acquired lower respiratory tract infections.Clin Radiol.2004;59:743–752.

- ,,.An assessment of inter‐observer agreement and accuracy when reporting plain radiographs.Clin Radiol.1997;52:235–238.

- Standardization of interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children. In:World Health Organization: Pneumonia Vaccine Trial Investigators' Group.Geneva:Department of Vaccine and Biologics;2001.

- ,,, et al.Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than 5 years of age for prevention of pneumonia: updated analysis using World Health Organization standardized interpretation of chest radiographs.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25:779–781.

- ,.The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data.Biometrics.1977;33:159–174.

- ,.Clinical, laboratory, and radiological information in the diagnosis of pneumonia in children.Ann Emerg Med.1988;17:43–46.

- ,.Intraobserver and interobserver agreement of the interpretation of pediatric chest radiographs.Emerg Radiol.17:285–290.

- ,,, et al.Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:347–382.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the management of adults with community‐acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001;163:1730–1754.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of radiological findings and microbial aetiology of childhood pneumonia.Acta Paediatr.1993;82:360–363.

- Kuhn JP, Slovis TL, Haller JO, eds.Caffey's Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging.10th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Mosby;2004.

- ,,, et al.Clinical predictors of pneumonia among children with wheezing.Pediatrics.2009;124:e29–e36.

- ,,, et al.The clinical impact of the radiology report in wheezing and nonwheezing febrile children: a survey of clinicians.Pediatr Radiol.2009;39:348–353.

The chest radiograph (CXR) is the most commonly used diagnostic imaging modality in children, and is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia. As such, physicians in developed countries rely on chest radiography to establish the diagnosis of pneumonia.13 However, there are limited data investigating the reliability of this test for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children.2, 46

Prior investigations have noted poor overall agreement by emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and pulmonary medicine physicians, and even radiologists, in their interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia.2, 5, 710 The World Health Organization (WHO) developed criteria to standardize CXR interpretation for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children for use in epidemiologic studies.11 These standardized definitions of pneumonia have been formally evaluated by the WHO6 and utilized in epidemiologic studies of vaccine efficacy,12 but the overall reliability of these radiographic criteria have not been studied outside of these forums.

We conducted this prospective case‐based study to evaluate the reliability of the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia among children presenting to a pediatric emergency department with clinical suspicion of pneumonia. We were primarily interested in assessing the overall reliability in CXR interpretation for the diagnosis of pneumonia, and identifying which radiographic features of pneumonia were consistently identified by radiologists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

We evaluated the reliability of CXR interpretation with respect to the diagnosis of pneumonia among radiologists. Six board‐certified radiologists at 2 academic children's hospitals (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA [n = 3] and Children's Hospital, Boston, Boston, MA [n = 3]) interpreted the same 110 chest radiographs in a blinded fashion. The radiologists varied with respect to the number of years practicing pediatric radiology (median 8 years, range 3‐36 years). Clinical information such as age, gender, clinical indication for obtaining the radiograph, history, and physical examination findings were not provided. Aside from the study form which stated the WHO classification scheme for radiographic pneumonia, no other information or training was provided to the radiologists as part of this study.

Radiographs were selected among a population of children presenting to the emergency department at Children's Hospital, Boston, who had a radiograph obtained for concern of pneumonia. From this cohort, we selected children who had radiographs which encompassed the spectrum of respiratory disease processes encountered in a pediatric population. The radiographs selected for review included 50 radiographs with a final reading in the medical record without suspicion for pneumonia, and 50 radiographs in which the diagnosis of pneumonia could not be excluded. In the latter group, 25 radiographs had a final reading suggestive of an alveolar infiltrate, and 25 radiographs had a final reading suggestive of an interstitial infiltrate. Ten duplicate radiographs were included to permit assessment of intra‐rater reliability.

Radiograph Interpretation

Radiologists at both sites interpreted the identical 110 radiographs (both anteroposterior [AP] and lateral views for each subject). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) images were downloaded from a registry at Children's Hospital, Boston, and were copied to DVDs which were provided to each radiologist. Standardized radiographic imaging software (eFilm Lite [Mississauga, Canada]) was used by each radiologist to view and interpret the radiographs.

Each radiologist completed a study questionnaire for each radiograph interpreted (see Supporting Appendix A in the online version of this article). The questionnaire utilized radiographic descriptors of primary end‐point pneumonia described by the WHO which were procured to standardize the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia.11, 12 The main outcome of interest was the presence or absence of an infiltrate. Among radiographs in which an infiltrate was identified, radiologists selected whether there was an alveolar infiltrate, interstitial infiltrate, or both. An alveolar infiltrate was defined as a dense or fluffy opacity that occupies a portion or whole of a lobe, or of the entire lung, that may or may not contain air bronchograms.11, 12 An interstitial infiltrate was defined by a lacy pattern involving both lungs, featuring peribronchial thickening and multiple areas of atelectasis.11, 12 It also included minor patchy infiltrates that were not of sufficient magnitude to constitute consolidation, and small areas of atelectasis that in children may be difficult to distinguish from consolidation. Among interstitial infiltrates, radiologists were asked to distinguish infiltrate from atelectasis. A radiograph classified as having either an alveolar infiltrate or interstitial infiltrate (not atelectasis) was considered to have any infiltrate. Additional findings including air bronchograms, hilar adenopathy, pleural effusion, and location of abnormalities were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Inter‐rater reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic to determine the overall agreement between the 6 radiologists for each binary outcome (ie, presence or absence of alveolar infiltrate). To calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for kappa statistics with more than 2 raters, we employed a bootstrapping method with 1000 replications of samples equal in size to the study sample, using the kapci program as implemented by STATA software (version 10.1, STATA Corp, College Station, TX). Also, intra‐rater reliability was evaluated by examining the agreement within each radiologist upon review of 10 duplicate radiographs that had been randomly inserted into the case‐mix. We used the benchmarks proposed by Landis and Koch to classify the strength of agreement measured by the kappa statistic, as follows: poor (<0.0); slight (0‐0.20); fair (0.21‐0.40); moderate (0.41‐0.60); substantial (0.61‐0.80); almost perfect (0.81‐1.0).13

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Children's Hospital, Boston and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

RESULTS

Patient Sample

The sample of 110 radiographs was obtained from 100 children presenting to the emergency department at Children's Hospital, Boston, with concern of pneumonia. These patients ranged in age from 1 week to 19 years (median, 3.5 years; interquartile range [IQR], 1.6‐6.0 years). Fifty (50%) of these patients were male. As stated above, the sample comprised 50 radiographs with a final reading in the medical record without suspicion for pneumonia, and 50 radiographs in which the diagnosis of pneumonia could not be excluded. The 10 duplicate radiographs encompassed a similar spectrum of findings.

Inter‐Rater Reliability

The kappa coefficients of inter‐rater reliability between the radiologists across the 6 clinical measures of interest are displayed in Table 1. As shown, the most reliable measure was that of alveolar infiltrate (Figure 1), which attained a substantial degree of agreement between the radiologists. Two other measures, any infiltrate and pleural effusion, attained moderate reliability, while bronchograms and hilar adenopathy were each classified as having fair reliability. However, interstitial infiltrate (Figure 2) was found to have the lowest kappa estimate, with a slight degree of reliability. When examining inter‐rater reliability among the radiologists separately from each institution, the pattern of results was similar.

| All Radiologists (n = 6) | Kappa | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Any infiltrate | 0.47 | 0.39, 0.56 |

| Alveolar infiltrate | 0.69 | 0.60, 0.78 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | 0.14 | 0.05, 0.23 |

| Air bronchograms | 0.32 | 0.24, 0.42 |

| Hilar adenopathy | 0.21 | 0.08, 0.39 |

| Pleural effusion | 0.45 | 0.29, 0.61 |

At least 4 of the 6 radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of an alveolar infiltrate for 95 of the 100 unique CXRs; all 6 radiologists agreed regarding the presence or absence of an alveolar infiltrate in 72 of the 100 unique CXRs. At least 4 of the 6 radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of any infiltrate and interstitial infiltrate 96% and 90% of the time, respectively. All 6 of the radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of any infiltrate and interstitial infiltrate 35% and 27% of the time, respectively.

Intra‐Rater Reliability

Estimates of intra‐rater reliability on the primary clinical outcomes (alveolar infiltrate, interstitial infiltrate, and any infiltrate) are found in Table 2. Across the 6 raters, the kappa estimates for alveolar infiltrate were all classified as substantial or almost perfect. The kappa estimates for interstitial infiltrate varied widely, ranging from fair to almost perfect, while for any infiltrate, reliability ranged from moderate to almost perfect.

| Kappa | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Any infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.60 | 0.10, 1.00 |

| Rater 3 | 0.80 | 0.44, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 5 | n/a* | |

| Rater 6 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Alveolar infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 3 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 5 | 0.78 | 0.39, 1.00 |

| Rater 6 | 0.74 | 0.27, 1.00 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.21 | 0.43, 0.85 |

| Rater 3 | 0.74 | 0.27, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | n/a | |

| Rater 5 | 0.58 | 0.07, 1.00 |

| Rater 6 | 0.62 | 0.5, 1.00 |

DISCUSSION

The chest radiograph serves as an integral component of the reference standard for the diagnosis of childhood pneumonia. Few prior studies have assessed the reliability of chest radiograph findings in children.3, 5, 12, 14, 15 We found a high degree of agreement among radiologists for radiologic findings consistent with bacterial pneumonia when standardized interpretation criteria were applied. In this study, we identified radiographic features of pneumonia, such as alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion, that were consistently identified by different radiologists reviewing the same radiograph and by the same radiologist reviewing the same radiograph. These data support the notion that radiographic features most suggestive of bacterial pneumonia are consistently identified by radiologists.16, 17 There was less consistency in the identification of other radiographic findings, such as interstitial infiltrates, air bronchograms, and hilar lymphadenopathy.

Prior studies have found high levels of disagreement among radiologists in the interpretation of chest radiographs.2, 3, 15, 18 Many of these prior studies emphasized variation in detection of radiographic findings that would not typically alter clinical management. We observed high intra‐rater, and inter‐rater reliability among radiologists for the findings of alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion. These are the radiographic findings most consistent with a bacterial etiologic agent for pneumonia.19 Other studies have also found that the presence of an alveolar infiltrate is a reliable radiographic finding in children18 and adults.7, 9, 10 These findings support the use of the WHO definition of primary endpoint pneumonia for use in epidemiologic studies.4, 6, 11

This study also confirms a previous report by Cherian et al. that findings of many children with asthma, reactive airways disease, bronchiolitis, and viral infections interstitial infiltrates are less reliable.6 This is not surprising considering the fact that these patients often have radiographic findings due to small airway disease and atelectasis.19, 20 The differentiation between atelectasis and interstitial infiltrate is difficult, particularly in young children. A prior study conducted among neonates observed wide variability in the interpretation of chest radiographs, and that the differentiation of pneumonia from atelectasis was difficult for this patient population.5 The decisions around antimicrobial treatment of children with radiographic findings of interstitial infiltrates should be made in the context of the clinical history and physical examination findings, and clinicians should realize that these radiographic features demonstrate poor reliability for the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Overall reliability for the presence of any infiltrate, and its converse, no infiltrate was considered moderate. This is driven by the low reliability and variability around the radiographic diagnosis of interstitial infiltrates. Our findings are similar to those observed in adults with lower respiratory tract infections.9 The low reliability in identification of interstitial infiltrates may explain why prior studies have demonstrated that the CXR results rarely change management in children who have radiographs performed for suspicion of pneumonia.1, 21 Our study highlights the importance of quantifying CXR findings to include specific comments regarding the presence or absence of alveolar infiltrates, rather than the presence or absence of any infiltrate.

The WHO has procured definitions the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia, and this definition has been utilized to help standardize the interpretation of chest radiographs for the conduct of epidemiological studies.6, 11 Specifically, the definitions utilized not only define the presence or absence of pneumonia, but also attempt to differentiate a primarily bacterial infection (consolidation or pleural effusion), from a viral or atypical presentation (interstitial pattern). Even under the best of circumstances, the differentiation of viral versus bacterial pneumonia is not always possible, and again, is often made by the treating physician by incorporating the clinical setting within which the radiograph was obtained.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the included radiographs did not reflect the frequency with which certain radiographic findings would be identified in children evaluated for pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department setting. Radiographs were purposefully selected to encompass a broad spectrum of radiologic findings, including less common findings such as hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions. Thus, the prevalence of pneumonia and other abnormal findings in this study was artificially higher than typically observed among a cohort of children for whom pneumonia is considered, a factor that may limit the generalizability of our results. Secondly, the clinical history was not provided to the radiologists to avoid bias by indication. For this study, we notified the radiologists that all radiographs were performed for clinical suspicion of pneumonia without providing details about the subjects' signs and symptoms. The absence of clinical history, however, does not mirror the real world scenario in which the interpretation of the chest radiograph is frequently made in the context of the clinical history. The relevance of this latter issue is unclear, as Tudor et al. found a nonstatistically significant improvement in the overall accuracy in chest radiograph interpretation when radiologists were provided clinical details.10 The radiologists recruited for this study all practice in an academic children's hospital setting, and thus, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to this type of practice setting. Finally, reproducibility does not imply accuracy, and reliability in identifying specific findings does not necessarily lead to improved or different management. Thus, while the reliability of radiographic findings of alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion is reassuringly high, the validity of these radiographic features for bacterial pneumonia is not known. Ascertainment of validity can only be assessed through the use of invasive testing such as lung biopsy, as the yield from bacterial testing such as blood cultures is low, and the results of other studies such as viral testing of nasopharyngeal washings do not prove an etiologic cause of pneumonia.

CONCLUSIONS

Radiographic findings of alveolar infiltrates and pleural effusions are highly reliable among radiologists. Radiographic interpretation of interstitial infiltrates appears to be less reliable.

The chest radiograph (CXR) is the most commonly used diagnostic imaging modality in children, and is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia. As such, physicians in developed countries rely on chest radiography to establish the diagnosis of pneumonia.13 However, there are limited data investigating the reliability of this test for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children.2, 46

Prior investigations have noted poor overall agreement by emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and pulmonary medicine physicians, and even radiologists, in their interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia.2, 5, 710 The World Health Organization (WHO) developed criteria to standardize CXR interpretation for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children for use in epidemiologic studies.11 These standardized definitions of pneumonia have been formally evaluated by the WHO6 and utilized in epidemiologic studies of vaccine efficacy,12 but the overall reliability of these radiographic criteria have not been studied outside of these forums.

We conducted this prospective case‐based study to evaluate the reliability of the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia among children presenting to a pediatric emergency department with clinical suspicion of pneumonia. We were primarily interested in assessing the overall reliability in CXR interpretation for the diagnosis of pneumonia, and identifying which radiographic features of pneumonia were consistently identified by radiologists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

We evaluated the reliability of CXR interpretation with respect to the diagnosis of pneumonia among radiologists. Six board‐certified radiologists at 2 academic children's hospitals (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA [n = 3] and Children's Hospital, Boston, Boston, MA [n = 3]) interpreted the same 110 chest radiographs in a blinded fashion. The radiologists varied with respect to the number of years practicing pediatric radiology (median 8 years, range 3‐36 years). Clinical information such as age, gender, clinical indication for obtaining the radiograph, history, and physical examination findings were not provided. Aside from the study form which stated the WHO classification scheme for radiographic pneumonia, no other information or training was provided to the radiologists as part of this study.

Radiographs were selected among a population of children presenting to the emergency department at Children's Hospital, Boston, who had a radiograph obtained for concern of pneumonia. From this cohort, we selected children who had radiographs which encompassed the spectrum of respiratory disease processes encountered in a pediatric population. The radiographs selected for review included 50 radiographs with a final reading in the medical record without suspicion for pneumonia, and 50 radiographs in which the diagnosis of pneumonia could not be excluded. In the latter group, 25 radiographs had a final reading suggestive of an alveolar infiltrate, and 25 radiographs had a final reading suggestive of an interstitial infiltrate. Ten duplicate radiographs were included to permit assessment of intra‐rater reliability.

Radiograph Interpretation

Radiologists at both sites interpreted the identical 110 radiographs (both anteroposterior [AP] and lateral views for each subject). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) images were downloaded from a registry at Children's Hospital, Boston, and were copied to DVDs which were provided to each radiologist. Standardized radiographic imaging software (eFilm Lite [Mississauga, Canada]) was used by each radiologist to view and interpret the radiographs.

Each radiologist completed a study questionnaire for each radiograph interpreted (see Supporting Appendix A in the online version of this article). The questionnaire utilized radiographic descriptors of primary end‐point pneumonia described by the WHO which were procured to standardize the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia.11, 12 The main outcome of interest was the presence or absence of an infiltrate. Among radiographs in which an infiltrate was identified, radiologists selected whether there was an alveolar infiltrate, interstitial infiltrate, or both. An alveolar infiltrate was defined as a dense or fluffy opacity that occupies a portion or whole of a lobe, or of the entire lung, that may or may not contain air bronchograms.11, 12 An interstitial infiltrate was defined by a lacy pattern involving both lungs, featuring peribronchial thickening and multiple areas of atelectasis.11, 12 It also included minor patchy infiltrates that were not of sufficient magnitude to constitute consolidation, and small areas of atelectasis that in children may be difficult to distinguish from consolidation. Among interstitial infiltrates, radiologists were asked to distinguish infiltrate from atelectasis. A radiograph classified as having either an alveolar infiltrate or interstitial infiltrate (not atelectasis) was considered to have any infiltrate. Additional findings including air bronchograms, hilar adenopathy, pleural effusion, and location of abnormalities were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Inter‐rater reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic to determine the overall agreement between the 6 radiologists for each binary outcome (ie, presence or absence of alveolar infiltrate). To calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for kappa statistics with more than 2 raters, we employed a bootstrapping method with 1000 replications of samples equal in size to the study sample, using the kapci program as implemented by STATA software (version 10.1, STATA Corp, College Station, TX). Also, intra‐rater reliability was evaluated by examining the agreement within each radiologist upon review of 10 duplicate radiographs that had been randomly inserted into the case‐mix. We used the benchmarks proposed by Landis and Koch to classify the strength of agreement measured by the kappa statistic, as follows: poor (<0.0); slight (0‐0.20); fair (0.21‐0.40); moderate (0.41‐0.60); substantial (0.61‐0.80); almost perfect (0.81‐1.0).13

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Children's Hospital, Boston and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

RESULTS

Patient Sample

The sample of 110 radiographs was obtained from 100 children presenting to the emergency department at Children's Hospital, Boston, with concern of pneumonia. These patients ranged in age from 1 week to 19 years (median, 3.5 years; interquartile range [IQR], 1.6‐6.0 years). Fifty (50%) of these patients were male. As stated above, the sample comprised 50 radiographs with a final reading in the medical record without suspicion for pneumonia, and 50 radiographs in which the diagnosis of pneumonia could not be excluded. The 10 duplicate radiographs encompassed a similar spectrum of findings.

Inter‐Rater Reliability

The kappa coefficients of inter‐rater reliability between the radiologists across the 6 clinical measures of interest are displayed in Table 1. As shown, the most reliable measure was that of alveolar infiltrate (Figure 1), which attained a substantial degree of agreement between the radiologists. Two other measures, any infiltrate and pleural effusion, attained moderate reliability, while bronchograms and hilar adenopathy were each classified as having fair reliability. However, interstitial infiltrate (Figure 2) was found to have the lowest kappa estimate, with a slight degree of reliability. When examining inter‐rater reliability among the radiologists separately from each institution, the pattern of results was similar.

| All Radiologists (n = 6) | Kappa | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Any infiltrate | 0.47 | 0.39, 0.56 |

| Alveolar infiltrate | 0.69 | 0.60, 0.78 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | 0.14 | 0.05, 0.23 |

| Air bronchograms | 0.32 | 0.24, 0.42 |

| Hilar adenopathy | 0.21 | 0.08, 0.39 |

| Pleural effusion | 0.45 | 0.29, 0.61 |

At least 4 of the 6 radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of an alveolar infiltrate for 95 of the 100 unique CXRs; all 6 radiologists agreed regarding the presence or absence of an alveolar infiltrate in 72 of the 100 unique CXRs. At least 4 of the 6 radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of any infiltrate and interstitial infiltrate 96% and 90% of the time, respectively. All 6 of the radiologists agreed on the presence or absence of any infiltrate and interstitial infiltrate 35% and 27% of the time, respectively.

Intra‐Rater Reliability

Estimates of intra‐rater reliability on the primary clinical outcomes (alveolar infiltrate, interstitial infiltrate, and any infiltrate) are found in Table 2. Across the 6 raters, the kappa estimates for alveolar infiltrate were all classified as substantial or almost perfect. The kappa estimates for interstitial infiltrate varied widely, ranging from fair to almost perfect, while for any infiltrate, reliability ranged from moderate to almost perfect.

| Kappa | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Any infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.60 | 0.10, 1.00 |

| Rater 3 | 0.80 | 0.44, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 5 | n/a* | |

| Rater 6 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Alveolar infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 3 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 5 | 0.78 | 0.39, 1.00 |

| Rater 6 | 0.74 | 0.27, 1.00 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | ||

| Rater 1 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.00 |

| Rater 2 | 0.21 | 0.43, 0.85 |

| Rater 3 | 0.74 | 0.27, 1.00 |

| Rater 4 | n/a | |

| Rater 5 | 0.58 | 0.07, 1.00 |

| Rater 6 | 0.62 | 0.5, 1.00 |

DISCUSSION

The chest radiograph serves as an integral component of the reference standard for the diagnosis of childhood pneumonia. Few prior studies have assessed the reliability of chest radiograph findings in children.3, 5, 12, 14, 15 We found a high degree of agreement among radiologists for radiologic findings consistent with bacterial pneumonia when standardized interpretation criteria were applied. In this study, we identified radiographic features of pneumonia, such as alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion, that were consistently identified by different radiologists reviewing the same radiograph and by the same radiologist reviewing the same radiograph. These data support the notion that radiographic features most suggestive of bacterial pneumonia are consistently identified by radiologists.16, 17 There was less consistency in the identification of other radiographic findings, such as interstitial infiltrates, air bronchograms, and hilar lymphadenopathy.

Prior studies have found high levels of disagreement among radiologists in the interpretation of chest radiographs.2, 3, 15, 18 Many of these prior studies emphasized variation in detection of radiographic findings that would not typically alter clinical management. We observed high intra‐rater, and inter‐rater reliability among radiologists for the findings of alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion. These are the radiographic findings most consistent with a bacterial etiologic agent for pneumonia.19 Other studies have also found that the presence of an alveolar infiltrate is a reliable radiographic finding in children18 and adults.7, 9, 10 These findings support the use of the WHO definition of primary endpoint pneumonia for use in epidemiologic studies.4, 6, 11

This study also confirms a previous report by Cherian et al. that findings of many children with asthma, reactive airways disease, bronchiolitis, and viral infections interstitial infiltrates are less reliable.6 This is not surprising considering the fact that these patients often have radiographic findings due to small airway disease and atelectasis.19, 20 The differentiation between atelectasis and interstitial infiltrate is difficult, particularly in young children. A prior study conducted among neonates observed wide variability in the interpretation of chest radiographs, and that the differentiation of pneumonia from atelectasis was difficult for this patient population.5 The decisions around antimicrobial treatment of children with radiographic findings of interstitial infiltrates should be made in the context of the clinical history and physical examination findings, and clinicians should realize that these radiographic features demonstrate poor reliability for the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Overall reliability for the presence of any infiltrate, and its converse, no infiltrate was considered moderate. This is driven by the low reliability and variability around the radiographic diagnosis of interstitial infiltrates. Our findings are similar to those observed in adults with lower respiratory tract infections.9 The low reliability in identification of interstitial infiltrates may explain why prior studies have demonstrated that the CXR results rarely change management in children who have radiographs performed for suspicion of pneumonia.1, 21 Our study highlights the importance of quantifying CXR findings to include specific comments regarding the presence or absence of alveolar infiltrates, rather than the presence or absence of any infiltrate.

The WHO has procured definitions the radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia, and this definition has been utilized to help standardize the interpretation of chest radiographs for the conduct of epidemiological studies.6, 11 Specifically, the definitions utilized not only define the presence or absence of pneumonia, but also attempt to differentiate a primarily bacterial infection (consolidation or pleural effusion), from a viral or atypical presentation (interstitial pattern). Even under the best of circumstances, the differentiation of viral versus bacterial pneumonia is not always possible, and again, is often made by the treating physician by incorporating the clinical setting within which the radiograph was obtained.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the included radiographs did not reflect the frequency with which certain radiographic findings would be identified in children evaluated for pneumonia in a pediatric emergency department setting. Radiographs were purposefully selected to encompass a broad spectrum of radiologic findings, including less common findings such as hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions. Thus, the prevalence of pneumonia and other abnormal findings in this study was artificially higher than typically observed among a cohort of children for whom pneumonia is considered, a factor that may limit the generalizability of our results. Secondly, the clinical history was not provided to the radiologists to avoid bias by indication. For this study, we notified the radiologists that all radiographs were performed for clinical suspicion of pneumonia without providing details about the subjects' signs and symptoms. The absence of clinical history, however, does not mirror the real world scenario in which the interpretation of the chest radiograph is frequently made in the context of the clinical history. The relevance of this latter issue is unclear, as Tudor et al. found a nonstatistically significant improvement in the overall accuracy in chest radiograph interpretation when radiologists were provided clinical details.10 The radiologists recruited for this study all practice in an academic children's hospital setting, and thus, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to this type of practice setting. Finally, reproducibility does not imply accuracy, and reliability in identifying specific findings does not necessarily lead to improved or different management. Thus, while the reliability of radiographic findings of alveolar infiltrate and pleural effusion is reassuringly high, the validity of these radiographic features for bacterial pneumonia is not known. Ascertainment of validity can only be assessed through the use of invasive testing such as lung biopsy, as the yield from bacterial testing such as blood cultures is low, and the results of other studies such as viral testing of nasopharyngeal washings do not prove an etiologic cause of pneumonia.

CONCLUSIONS

Radiographic findings of alveolar infiltrates and pleural effusions are highly reliable among radiologists. Radiographic interpretation of interstitial infiltrates appears to be less reliable.

- ,,, et al.Usefulness of chest radiographs in children with acute lower respiratory tract disease.J Pediatr.1987;111:187–193.

- ,,, et al.Disagreement in the interpretation of chest radiographs among specialists and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with suspected pneumonia.Eur J Intern Med.2006;17:43–47.

- ,,.Problems in the clinical and roentgenographic diagnosis of pneumonia in young children.Clin Pediatr (Phila).1984;23:398–399.

- WHO guidelines on detecting pneumonia in children.Lancet.1991;338:1453–1454.

- ,,, et al.Inter‐ and intra‐observer variability in the assessment of atelectasis and consolidation in neonatal chest radiographs.Pediatr Radiol.1999;29:459–462.

- ,,, et al.Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies.Bull World Health Organ.2005;83:353–359.

- ,,, et al.Interobserver reliability of the chest radiograph in community‐acquired pneumonia. PORT Investigators.Chest.1996;110:343–350.

- ,,, et al.Chest radiographs in the emergency department: is the radiologist really necessary?Postgrad Med J.2003;79:214–217.

- ,,, et al.Inter‐observer variation in the interpretation of chest radiographs for pneumonia in community‐acquired lower respiratory tract infections.Clin Radiol.2004;59:743–752.

- ,,.An assessment of inter‐observer agreement and accuracy when reporting plain radiographs.Clin Radiol.1997;52:235–238.

- Standardization of interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children. In:World Health Organization: Pneumonia Vaccine Trial Investigators' Group.Geneva:Department of Vaccine and Biologics;2001.

- ,,, et al.Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than 5 years of age for prevention of pneumonia: updated analysis using World Health Organization standardized interpretation of chest radiographs.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25:779–781.

- ,.The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data.Biometrics.1977;33:159–174.

- ,.Clinical, laboratory, and radiological information in the diagnosis of pneumonia in children.Ann Emerg Med.1988;17:43–46.

- ,.Intraobserver and interobserver agreement of the interpretation of pediatric chest radiographs.Emerg Radiol.17:285–290.

- ,,, et al.Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31:347–382.

- ,,, et al.Guidelines for the management of adults with community‐acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001;163:1730–1754.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of radiological findings and microbial aetiology of childhood pneumonia.Acta Paediatr.1993;82:360–363.

- Kuhn JP, Slovis TL, Haller JO, eds.Caffey's Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging.10th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Mosby;2004.

- ,,, et al.Clinical predictors of pneumonia among children with wheezing.Pediatrics.2009;124:e29–e36.