User login

Fracture Blisters After Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

Fracture blisters are a relatively uncommon complication of high-energy fractures, with an incidence of 2.9%.1 In the lower extremity, fracture blisters almost always occur distal to the knee.1 Histologically, the blisters represent an injury to the dermoepidermal junction.2 On physical examination, there are tense blood- and/or clear fluid–filled bullae overlying markedly swollen and edematous soft tissue,1 resembling a second-degree burn.3 Infection may develop after fracture blisters,1 and this is perhaps the most dreaded complication of total knee arthroplasty (TKA). The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 71-year-old man with end-stage osteoarthritis of the right knee underwent an elective TKA with cemented components (Legion PS; Smith & Nephew). His medical history included venous insufficiency, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, morbid obesity (body mass index, 50), and a previous uneventful left TKA. Tourniquet time was 78 minutes and estimated blood loss was 100 mL. An intra-articular drain was used and was removed on the first postoperative day. After wound closure, a soft splint bandage consisting of 2 to 3 layers of cotton and bias wrap was applied. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with enoxaparin 40 mg once daily was started on the first postoperative day.

Upon removal of the surgical dressings on the second postoperative day, the anterior leg was found to have a combination of tense clear fluid– and blood-filled blisters on markedly swollen and erythematous skin. The incision was minimally involved (Figure A). There was diffuse 2+ pitting edema with hyperesthesia in the affected skin distal to the knee. Prior to these findings, the patient had complained of increasing pain in his operative leg, but there was no escalation in analgesic requirements. There was no evidence of compartment syndrome on serial examinations. An ultrasound of the lower extremity was negative for DVT. Plain films did not show iatrogenic fractures. There was no intraoperative vascular injury, and the foot pulses remained unchanged between the time the patient was in the preoperative holding unit, the postanesthesia care unit, and the orthopedic ward. The operative leg was treated with elevation and loosely applied Kerlix roll gauze (Kendall, Covidien), but active blister formation continued for another 2 days. A 10-day prophylactic course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated on the third postoperative day after the blisters started to rupture. The patient was allowed to bear weight as tolerated, but his physical therapy (PT) course was limited by pain and fear “of losing his leg.” He declined several PT sessions and was hesitant to use continuous passive motion. The patient was discharged to a short-term rehabilitation facility with weekly outpatient follow-up. On the second postoperative week, his fluid-filled blisters completely reepithelialized, but the blood-filled blisters required an additional week for reepithelialization (Figure B). While the patient’s knee was stiff because of limited PT participation, it was not until the second postoperative week when most of the fracture blisters had healed that he was able to resume an intensive knee exercise program, avoiding the need for manipulation under anesthesia.

Discussion

Giordano and colleagues2 identified 2 types of fracture blisters: clear fluid– and blood-filled. While both types involved disruption of the dermoepidermal junction, greater disruption and complete absence of dermal epithelial cells was observed in the hemorrhagic type. Clinical follow-up of the patients in the study by Giordano and colleagues2 showed that the mean time for reepithelialization was 12 days for fluid-filled blisters and 16 days for blood-filled blisters. These findings are similar to what we observed in our case report. In particular, the fluid-filled blisters healed in 2 weeks, whereas the blood-filled blisters required 3 weeks to heal.

The etiology of the fracture blisters in this patient is likely multifactorial and related to age, obesity, venous insufficiency, and diabetes mellitus. Farage and colleagues4 described a series of progressive degenerative changes in the aging skin, including vascular atrophy and degradation of dermal connective tissue, leading to compromised skin competence. The integrity of the dermis can be further reduced in patients with diabetes through glycosylation of collagen fibrils.5 Compared with age-matched normal controls, patients with insulin-dependent diabetes have a reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation.6 Obesity is another potential contributing factor, with multiple studies showing significantly impaired venous flow in obese patients.7,8 Taken together, soft-tissue swelling after surgery in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency and compromised skin due to advanced age and diabetes may lead to markedly elevated interstitial pressure. One mechanism to relieve such abnormally high pressure is the formation of fracture blisters.1

Surgical risk factors that could have contributed to the complication in this case include the surgical skin preparation solution (ChloraPrep; CareFusion), use of adhesive antimicrobial drape (Ioban, 3M), tourniquet time, dressing choice, and DVT prophylaxis regimen. While the skin preparation solution is an unlikely culprit since the presentation is not consistent with contact dermatitis, inappropriate strapping or removal of the adhesive drape could result in stretch injury of the skin, shearing the dermoepidermal junction and causing tension blisters.9 There were no intraoperative complications and the tourniquet time was appropriate (78 minutes). Postoperatively, no compressive or adhesive dressings were used. With regards to DVT prophylaxis, the patient received a single dose of enoxaparin on the first postoperative day. While heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters have been reported,10 I do not feel that the use of enoxaparin was a contributing factor. Heparin-induced blisters have been described as systemic blisters,10 whereas the blisters in this case were confined to the operative extremity. The patient was not taking any nutritional supplements (eg, fish oil, vitamin E) that could have increased his risk of bleeding. Throughout his hospital stay, he was hemodynamically stable and did not require blood transfusion.

Management of fracture blisters is controversial, and there is no consensus on appropriate soft-tissue handling. In this patient, the blisters were left intact. Blister fluid has been shown to be sterile, containing growth factors, opsonins, and activated neutrophils that aid in healing and infection prevention.1 Giordano and Koval11 found no difference in the outcome of 3 soft-tissue treatment techniques: (1) aspiration of the blister, (2) deroofing of the blister followed by application of a topical antibiotic cream or coverage with nonadherent dressing, or (3) keeping the blister intact and covered with loose dressing or exposed to air. In contrast, Strauss and colleagues12 found that deroofing the fracture blister to healthy tissue followed by twice-daily application of silver sulfadiazine antibiotic cream promoted reepithelialization and resulted in better cosmetic appearance and higher patient satisfaction.

The optimal dressing for fracture blisters remains elusive. Madden and colleagues13 showed that the use of occlusive nonadherent dressing was associated with significantly faster healing and less pain compared with semiocclusive, antibiotic-impregnated dressings. In another study, Varela and colleagues1 found no differences in blister healing between patients treated with either (1) dry dressing and casting, (2) Silvadene dressing (King Pharmaceuticals), or (3) whirlpool débridement and Silvadene dressing.

Infection is perhaps the most dreaded complication of fracture blisters after TKA. Varela and colleagues1 showed that, while the fluid in intact blisters was a sterile transudate, polymicrobial colonization with skin flora often occurred soon after blister rupture and persisted until reepithelialization. Our patient received a 10-day course of prophylactic antibiotics and no superficial or deep infection developed; however, the real contribution of antibiotic prophylaxis to the absence of infection cannot be established based solely on 1 case.

Pain is another concern associated with fracture blisters. Our patient had significant pain that limited his ability to participate in PT, resulting in limited knee range of motion and eventual discharge to a short-term rehabilitation facility. Fortunately, after resolution of the fracture blisters, he was able to participate in an aggressive rehabilitation program. By 6 weeks after surgery, he had significant improvement in his knee motion, avoiding the need for manipulation under anesthesia.

Conclusion

This case represents the first reported fracture blisters after primary TKA. The risk of deep surgical site infection, a devastating complication after TKA, is perhaps the most frightening concern of this rare complication. While the etiology and the management are controversial, there is evidence to recommend prophylactic antibiotics after blister rupture and skin desquamation. The decision to withhold DVT prophylaxis should be based on individual patient risk factors and blister type (blood-filled vs clear fluid–filled). Patients should be encouraged to continue knee exercises during reepithelialization to avoid stiffness.

1. Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, Slemmons BK. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7(5):417-427.

2. Giordano CP, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD, Desai P. Fracture blisters. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(307):214-221.

3. Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, Abraham M, Arnold C. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(1):131-133.

4. Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Clinical implications of aging skin: cutaneous disorders in the elderly. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(2):73-86.

5. Quondamatteo F. Skin and diabetes mellitus: what do we know? Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355(1):1-21.

6. Bernstein JE, Levine LE, Medenica MM, Yung CW, Soltani K. Reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation in insulin-dependent diabetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):790-791.

7. Willenberg T, Schumacher A, Amann-Vesti B, et al. Impact of obesity on venous hemodynamics of the lower limbs. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(3):664-668.

8. van Rij AM, De Alwis CS, Jiang P, et al. Obesity and impaired venous function. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(6):739-744.

9. Polatsch DB, Baskies MA, Hommen JP, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Tape blisters that develop after hip fracture surgery: a retrospective series and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2004;33(9):452-456.

10. Roux J, Duong TA, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(1):105-107.

11. Giordano CP, Koval KJ. Treatment of fracture blisters: a prospective study of 53 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(2):171-176.

12. Strauss EJ, Petrucelli G, Bong M, Koval KJ, Egol KA. Blisters associated with lower-extremity fracture: results of a prospective treatment protocol. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(9):618-622.

13. Madden MR, Nolan E, Finkelstein JL, et al. Comparison of an occlusive and a semi-occlusive dressing and the effect of the wound exudate upon keratinocyte proliferation. J Trauma. 1989;29(7):924-930; discussion 930-931.

Fracture blisters are a relatively uncommon complication of high-energy fractures, with an incidence of 2.9%.1 In the lower extremity, fracture blisters almost always occur distal to the knee.1 Histologically, the blisters represent an injury to the dermoepidermal junction.2 On physical examination, there are tense blood- and/or clear fluid–filled bullae overlying markedly swollen and edematous soft tissue,1 resembling a second-degree burn.3 Infection may develop after fracture blisters,1 and this is perhaps the most dreaded complication of total knee arthroplasty (TKA). The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 71-year-old man with end-stage osteoarthritis of the right knee underwent an elective TKA with cemented components (Legion PS; Smith & Nephew). His medical history included venous insufficiency, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, morbid obesity (body mass index, 50), and a previous uneventful left TKA. Tourniquet time was 78 minutes and estimated blood loss was 100 mL. An intra-articular drain was used and was removed on the first postoperative day. After wound closure, a soft splint bandage consisting of 2 to 3 layers of cotton and bias wrap was applied. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with enoxaparin 40 mg once daily was started on the first postoperative day.

Upon removal of the surgical dressings on the second postoperative day, the anterior leg was found to have a combination of tense clear fluid– and blood-filled blisters on markedly swollen and erythematous skin. The incision was minimally involved (Figure A). There was diffuse 2+ pitting edema with hyperesthesia in the affected skin distal to the knee. Prior to these findings, the patient had complained of increasing pain in his operative leg, but there was no escalation in analgesic requirements. There was no evidence of compartment syndrome on serial examinations. An ultrasound of the lower extremity was negative for DVT. Plain films did not show iatrogenic fractures. There was no intraoperative vascular injury, and the foot pulses remained unchanged between the time the patient was in the preoperative holding unit, the postanesthesia care unit, and the orthopedic ward. The operative leg was treated with elevation and loosely applied Kerlix roll gauze (Kendall, Covidien), but active blister formation continued for another 2 days. A 10-day prophylactic course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated on the third postoperative day after the blisters started to rupture. The patient was allowed to bear weight as tolerated, but his physical therapy (PT) course was limited by pain and fear “of losing his leg.” He declined several PT sessions and was hesitant to use continuous passive motion. The patient was discharged to a short-term rehabilitation facility with weekly outpatient follow-up. On the second postoperative week, his fluid-filled blisters completely reepithelialized, but the blood-filled blisters required an additional week for reepithelialization (Figure B). While the patient’s knee was stiff because of limited PT participation, it was not until the second postoperative week when most of the fracture blisters had healed that he was able to resume an intensive knee exercise program, avoiding the need for manipulation under anesthesia.

Discussion

Giordano and colleagues2 identified 2 types of fracture blisters: clear fluid– and blood-filled. While both types involved disruption of the dermoepidermal junction, greater disruption and complete absence of dermal epithelial cells was observed in the hemorrhagic type. Clinical follow-up of the patients in the study by Giordano and colleagues2 showed that the mean time for reepithelialization was 12 days for fluid-filled blisters and 16 days for blood-filled blisters. These findings are similar to what we observed in our case report. In particular, the fluid-filled blisters healed in 2 weeks, whereas the blood-filled blisters required 3 weeks to heal.

The etiology of the fracture blisters in this patient is likely multifactorial and related to age, obesity, venous insufficiency, and diabetes mellitus. Farage and colleagues4 described a series of progressive degenerative changes in the aging skin, including vascular atrophy and degradation of dermal connective tissue, leading to compromised skin competence. The integrity of the dermis can be further reduced in patients with diabetes through glycosylation of collagen fibrils.5 Compared with age-matched normal controls, patients with insulin-dependent diabetes have a reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation.6 Obesity is another potential contributing factor, with multiple studies showing significantly impaired venous flow in obese patients.7,8 Taken together, soft-tissue swelling after surgery in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency and compromised skin due to advanced age and diabetes may lead to markedly elevated interstitial pressure. One mechanism to relieve such abnormally high pressure is the formation of fracture blisters.1

Surgical risk factors that could have contributed to the complication in this case include the surgical skin preparation solution (ChloraPrep; CareFusion), use of adhesive antimicrobial drape (Ioban, 3M), tourniquet time, dressing choice, and DVT prophylaxis regimen. While the skin preparation solution is an unlikely culprit since the presentation is not consistent with contact dermatitis, inappropriate strapping or removal of the adhesive drape could result in stretch injury of the skin, shearing the dermoepidermal junction and causing tension blisters.9 There were no intraoperative complications and the tourniquet time was appropriate (78 minutes). Postoperatively, no compressive or adhesive dressings were used. With regards to DVT prophylaxis, the patient received a single dose of enoxaparin on the first postoperative day. While heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters have been reported,10 I do not feel that the use of enoxaparin was a contributing factor. Heparin-induced blisters have been described as systemic blisters,10 whereas the blisters in this case were confined to the operative extremity. The patient was not taking any nutritional supplements (eg, fish oil, vitamin E) that could have increased his risk of bleeding. Throughout his hospital stay, he was hemodynamically stable and did not require blood transfusion.

Management of fracture blisters is controversial, and there is no consensus on appropriate soft-tissue handling. In this patient, the blisters were left intact. Blister fluid has been shown to be sterile, containing growth factors, opsonins, and activated neutrophils that aid in healing and infection prevention.1 Giordano and Koval11 found no difference in the outcome of 3 soft-tissue treatment techniques: (1) aspiration of the blister, (2) deroofing of the blister followed by application of a topical antibiotic cream or coverage with nonadherent dressing, or (3) keeping the blister intact and covered with loose dressing or exposed to air. In contrast, Strauss and colleagues12 found that deroofing the fracture blister to healthy tissue followed by twice-daily application of silver sulfadiazine antibiotic cream promoted reepithelialization and resulted in better cosmetic appearance and higher patient satisfaction.

The optimal dressing for fracture blisters remains elusive. Madden and colleagues13 showed that the use of occlusive nonadherent dressing was associated with significantly faster healing and less pain compared with semiocclusive, antibiotic-impregnated dressings. In another study, Varela and colleagues1 found no differences in blister healing between patients treated with either (1) dry dressing and casting, (2) Silvadene dressing (King Pharmaceuticals), or (3) whirlpool débridement and Silvadene dressing.

Infection is perhaps the most dreaded complication of fracture blisters after TKA. Varela and colleagues1 showed that, while the fluid in intact blisters was a sterile transudate, polymicrobial colonization with skin flora often occurred soon after blister rupture and persisted until reepithelialization. Our patient received a 10-day course of prophylactic antibiotics and no superficial or deep infection developed; however, the real contribution of antibiotic prophylaxis to the absence of infection cannot be established based solely on 1 case.

Pain is another concern associated with fracture blisters. Our patient had significant pain that limited his ability to participate in PT, resulting in limited knee range of motion and eventual discharge to a short-term rehabilitation facility. Fortunately, after resolution of the fracture blisters, he was able to participate in an aggressive rehabilitation program. By 6 weeks after surgery, he had significant improvement in his knee motion, avoiding the need for manipulation under anesthesia.

Conclusion

This case represents the first reported fracture blisters after primary TKA. The risk of deep surgical site infection, a devastating complication after TKA, is perhaps the most frightening concern of this rare complication. While the etiology and the management are controversial, there is evidence to recommend prophylactic antibiotics after blister rupture and skin desquamation. The decision to withhold DVT prophylaxis should be based on individual patient risk factors and blister type (blood-filled vs clear fluid–filled). Patients should be encouraged to continue knee exercises during reepithelialization to avoid stiffness.

Fracture blisters are a relatively uncommon complication of high-energy fractures, with an incidence of 2.9%.1 In the lower extremity, fracture blisters almost always occur distal to the knee.1 Histologically, the blisters represent an injury to the dermoepidermal junction.2 On physical examination, there are tense blood- and/or clear fluid–filled bullae overlying markedly swollen and edematous soft tissue,1 resembling a second-degree burn.3 Infection may develop after fracture blisters,1 and this is perhaps the most dreaded complication of total knee arthroplasty (TKA). The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 71-year-old man with end-stage osteoarthritis of the right knee underwent an elective TKA with cemented components (Legion PS; Smith & Nephew). His medical history included venous insufficiency, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, morbid obesity (body mass index, 50), and a previous uneventful left TKA. Tourniquet time was 78 minutes and estimated blood loss was 100 mL. An intra-articular drain was used and was removed on the first postoperative day. After wound closure, a soft splint bandage consisting of 2 to 3 layers of cotton and bias wrap was applied. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with enoxaparin 40 mg once daily was started on the first postoperative day.

Upon removal of the surgical dressings on the second postoperative day, the anterior leg was found to have a combination of tense clear fluid– and blood-filled blisters on markedly swollen and erythematous skin. The incision was minimally involved (Figure A). There was diffuse 2+ pitting edema with hyperesthesia in the affected skin distal to the knee. Prior to these findings, the patient had complained of increasing pain in his operative leg, but there was no escalation in analgesic requirements. There was no evidence of compartment syndrome on serial examinations. An ultrasound of the lower extremity was negative for DVT. Plain films did not show iatrogenic fractures. There was no intraoperative vascular injury, and the foot pulses remained unchanged between the time the patient was in the preoperative holding unit, the postanesthesia care unit, and the orthopedic ward. The operative leg was treated with elevation and loosely applied Kerlix roll gauze (Kendall, Covidien), but active blister formation continued for another 2 days. A 10-day prophylactic course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated on the third postoperative day after the blisters started to rupture. The patient was allowed to bear weight as tolerated, but his physical therapy (PT) course was limited by pain and fear “of losing his leg.” He declined several PT sessions and was hesitant to use continuous passive motion. The patient was discharged to a short-term rehabilitation facility with weekly outpatient follow-up. On the second postoperative week, his fluid-filled blisters completely reepithelialized, but the blood-filled blisters required an additional week for reepithelialization (Figure B). While the patient’s knee was stiff because of limited PT participation, it was not until the second postoperative week when most of the fracture blisters had healed that he was able to resume an intensive knee exercise program, avoiding the need for manipulation under anesthesia.

Discussion

Giordano and colleagues2 identified 2 types of fracture blisters: clear fluid– and blood-filled. While both types involved disruption of the dermoepidermal junction, greater disruption and complete absence of dermal epithelial cells was observed in the hemorrhagic type. Clinical follow-up of the patients in the study by Giordano and colleagues2 showed that the mean time for reepithelialization was 12 days for fluid-filled blisters and 16 days for blood-filled blisters. These findings are similar to what we observed in our case report. In particular, the fluid-filled blisters healed in 2 weeks, whereas the blood-filled blisters required 3 weeks to heal.

The etiology of the fracture blisters in this patient is likely multifactorial and related to age, obesity, venous insufficiency, and diabetes mellitus. Farage and colleagues4 described a series of progressive degenerative changes in the aging skin, including vascular atrophy and degradation of dermal connective tissue, leading to compromised skin competence. The integrity of the dermis can be further reduced in patients with diabetes through glycosylation of collagen fibrils.5 Compared with age-matched normal controls, patients with insulin-dependent diabetes have a reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation.6 Obesity is another potential contributing factor, with multiple studies showing significantly impaired venous flow in obese patients.7,8 Taken together, soft-tissue swelling after surgery in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency and compromised skin due to advanced age and diabetes may lead to markedly elevated interstitial pressure. One mechanism to relieve such abnormally high pressure is the formation of fracture blisters.1

Surgical risk factors that could have contributed to the complication in this case include the surgical skin preparation solution (ChloraPrep; CareFusion), use of adhesive antimicrobial drape (Ioban, 3M), tourniquet time, dressing choice, and DVT prophylaxis regimen. While the skin preparation solution is an unlikely culprit since the presentation is not consistent with contact dermatitis, inappropriate strapping or removal of the adhesive drape could result in stretch injury of the skin, shearing the dermoepidermal junction and causing tension blisters.9 There were no intraoperative complications and the tourniquet time was appropriate (78 minutes). Postoperatively, no compressive or adhesive dressings were used. With regards to DVT prophylaxis, the patient received a single dose of enoxaparin on the first postoperative day. While heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters have been reported,10 I do not feel that the use of enoxaparin was a contributing factor. Heparin-induced blisters have been described as systemic blisters,10 whereas the blisters in this case were confined to the operative extremity. The patient was not taking any nutritional supplements (eg, fish oil, vitamin E) that could have increased his risk of bleeding. Throughout his hospital stay, he was hemodynamically stable and did not require blood transfusion.

Management of fracture blisters is controversial, and there is no consensus on appropriate soft-tissue handling. In this patient, the blisters were left intact. Blister fluid has been shown to be sterile, containing growth factors, opsonins, and activated neutrophils that aid in healing and infection prevention.1 Giordano and Koval11 found no difference in the outcome of 3 soft-tissue treatment techniques: (1) aspiration of the blister, (2) deroofing of the blister followed by application of a topical antibiotic cream or coverage with nonadherent dressing, or (3) keeping the blister intact and covered with loose dressing or exposed to air. In contrast, Strauss and colleagues12 found that deroofing the fracture blister to healthy tissue followed by twice-daily application of silver sulfadiazine antibiotic cream promoted reepithelialization and resulted in better cosmetic appearance and higher patient satisfaction.

The optimal dressing for fracture blisters remains elusive. Madden and colleagues13 showed that the use of occlusive nonadherent dressing was associated with significantly faster healing and less pain compared with semiocclusive, antibiotic-impregnated dressings. In another study, Varela and colleagues1 found no differences in blister healing between patients treated with either (1) dry dressing and casting, (2) Silvadene dressing (King Pharmaceuticals), or (3) whirlpool débridement and Silvadene dressing.

Infection is perhaps the most dreaded complication of fracture blisters after TKA. Varela and colleagues1 showed that, while the fluid in intact blisters was a sterile transudate, polymicrobial colonization with skin flora often occurred soon after blister rupture and persisted until reepithelialization. Our patient received a 10-day course of prophylactic antibiotics and no superficial or deep infection developed; however, the real contribution of antibiotic prophylaxis to the absence of infection cannot be established based solely on 1 case.

Pain is another concern associated with fracture blisters. Our patient had significant pain that limited his ability to participate in PT, resulting in limited knee range of motion and eventual discharge to a short-term rehabilitation facility. Fortunately, after resolution of the fracture blisters, he was able to participate in an aggressive rehabilitation program. By 6 weeks after surgery, he had significant improvement in his knee motion, avoiding the need for manipulation under anesthesia.

Conclusion

This case represents the first reported fracture blisters after primary TKA. The risk of deep surgical site infection, a devastating complication after TKA, is perhaps the most frightening concern of this rare complication. While the etiology and the management are controversial, there is evidence to recommend prophylactic antibiotics after blister rupture and skin desquamation. The decision to withhold DVT prophylaxis should be based on individual patient risk factors and blister type (blood-filled vs clear fluid–filled). Patients should be encouraged to continue knee exercises during reepithelialization to avoid stiffness.

1. Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, Slemmons BK. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7(5):417-427.

2. Giordano CP, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD, Desai P. Fracture blisters. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(307):214-221.

3. Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, Abraham M, Arnold C. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(1):131-133.

4. Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Clinical implications of aging skin: cutaneous disorders in the elderly. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(2):73-86.

5. Quondamatteo F. Skin and diabetes mellitus: what do we know? Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355(1):1-21.

6. Bernstein JE, Levine LE, Medenica MM, Yung CW, Soltani K. Reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation in insulin-dependent diabetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):790-791.

7. Willenberg T, Schumacher A, Amann-Vesti B, et al. Impact of obesity on venous hemodynamics of the lower limbs. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(3):664-668.

8. van Rij AM, De Alwis CS, Jiang P, et al. Obesity and impaired venous function. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(6):739-744.

9. Polatsch DB, Baskies MA, Hommen JP, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Tape blisters that develop after hip fracture surgery: a retrospective series and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2004;33(9):452-456.

10. Roux J, Duong TA, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(1):105-107.

11. Giordano CP, Koval KJ. Treatment of fracture blisters: a prospective study of 53 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(2):171-176.

12. Strauss EJ, Petrucelli G, Bong M, Koval KJ, Egol KA. Blisters associated with lower-extremity fracture: results of a prospective treatment protocol. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(9):618-622.

13. Madden MR, Nolan E, Finkelstein JL, et al. Comparison of an occlusive and a semi-occlusive dressing and the effect of the wound exudate upon keratinocyte proliferation. J Trauma. 1989;29(7):924-930; discussion 930-931.

1. Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, Slemmons BK. Fracture blisters: clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7(5):417-427.

2. Giordano CP, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD, Desai P. Fracture blisters. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(307):214-221.

3. Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, Abraham M, Arnold C. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(1):131-133.

4. Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Clinical implications of aging skin: cutaneous disorders in the elderly. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(2):73-86.

5. Quondamatteo F. Skin and diabetes mellitus: what do we know? Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355(1):1-21.

6. Bernstein JE, Levine LE, Medenica MM, Yung CW, Soltani K. Reduced threshold to suction-induced blister formation in insulin-dependent diabetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):790-791.

7. Willenberg T, Schumacher A, Amann-Vesti B, et al. Impact of obesity on venous hemodynamics of the lower limbs. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(3):664-668.

8. van Rij AM, De Alwis CS, Jiang P, et al. Obesity and impaired venous function. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(6):739-744.

9. Polatsch DB, Baskies MA, Hommen JP, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Tape blisters that develop after hip fracture surgery: a retrospective series and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2004;33(9):452-456.

10. Roux J, Duong TA, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Heparin-induced hemorrhagic blisters. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(1):105-107.

11. Giordano CP, Koval KJ. Treatment of fracture blisters: a prospective study of 53 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(2):171-176.

12. Strauss EJ, Petrucelli G, Bong M, Koval KJ, Egol KA. Blisters associated with lower-extremity fracture: results of a prospective treatment protocol. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(9):618-622.

13. Madden MR, Nolan E, Finkelstein JL, et al. Comparison of an occlusive and a semi-occlusive dressing and the effect of the wound exudate upon keratinocyte proliferation. J Trauma. 1989;29(7):924-930; discussion 930-931.

Giant Solitary Synovial Chondromatosis Mimicking Chondrosarcoma: Report of a Rare Histologic Presentation and Literature Review

Synovial chondromatosis (SCM) is a relatively rare benign lesion of the synovium.1 Its pathogenesis has been thought to be a chondral metaplasia of the subintimal layer of the intra- or extra-articular synovium.2 However, evidence supporting a neoplastic cause of the disease is emerging.3 When intra-articular, any joint can be affected, though large joints are more prone to the disease; the knee, hip, and elbow are the most common locations.4 The synovial layer of tendons or bursae can be the origin of extra-articular SCM.5

Synovial chondrosarcoma (SCS), an even rarer pathology, can be caused by malignant transformation of SCM or can appear de novo on a synovial background.6 Histologic differentiation from SCM might be difficult because of the high incidence of hypercellularity, cellular atypia, and binucleated cells.6 Some features, such as presence of a very large mass or erosion of the surrounding bones, have been indicated as possible signs of malignancy.3 An unusual presentation of SCM, giant solitary synovial chondromatosis (GSSCM), can be hard to distinguish from SCS because of the large volume and possible aggressive radiologic findings.7 Some histologic features, such as presence of necrosis and mitotic cells, have been suggested as distinctive criteria for malignancy.8

In this article, we present a case of benign GSSCM with a histologic feature that has not been considered typical for benign SCM. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

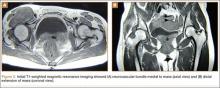

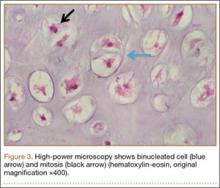

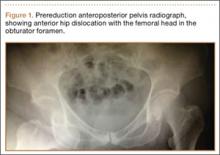

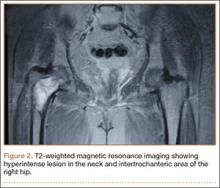

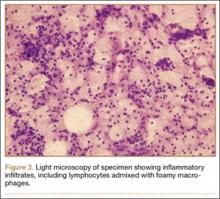

An 18-year-old woman presented with a large mass over the right hip. The mass had been growing slowly for 2 years. One year before presentation, a radiograph showed a large hip mass with fluffy calcification (Figure 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large nonhomogeneous mass anterior to the hip capsule and extending into the hip joint back to the posterior part of the joint (Figures 2A, 2B). Open incisional biopsy was performed in a local hospital at the time, and the histologic analysis revealed presence of atypical binucleated cells and pleomorphism, in addition to some mitotic activity (0 to 1 per high-power field) (Figure 3). These findings suggested malignancy. The patient declined surgery up until the time she presented to our hospital, 1 year later.

Clinical examination findings on admission to our hospital were striking. The patient had a large mass in the groin region. It was fairly tender and firm to palpation, immobile, and close to the skin. Hip motion was mildly painful but obviously restricted.

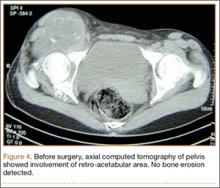

The mass was restaged. New radiographs and MRI did not show any significant changes since the previous year, computed tomography (CT) did not show any bone erosion (Figure 4), and chest radiograph, CT, and whole-body bone scan did not demonstrate any signs of metastasis.

Given the clinical presentation and previous histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of GSSCM with possible malignant transformation was made. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During surgery, the tumor was exposed through the Smith-Petersen approach. The mass was extruding under the fascia between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and iliopsoas muscle laterally. There was no adhesion of the surrounding structures, including the femoral neurovascular bundle, to the mass. The muscle was sitting on the anterolateral surface of the mass, which was considered located in the iliopsoas bursa but extending to the joint. In the vertical plane, the mass extended down to the subtrochanteric area. The entire solid extra-articular mass was excised en bloc, and hip capsulotomy was performed inferior to the area of emergence of the mass. The joint was occupied by a single solid cartilaginous mass molding around the femoral neck, filling the piriformis fossa and propagating to the posterior joint space. Obtaining enough exposure to the back of the joint required surgical hip dislocation. The visualized acetabular fossa revealed chondral fragments, which were excised. Bone erosion or significant osteoarthritis was not detected in any part of the joint. A nearly total synovectomy was performed, leaving the ascending retinacular vessels intact. Meticulous technique was used to avoid contaminating the extra-articular tissues. The wound was closed in the routine way after hip relocation.

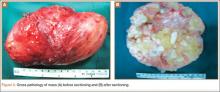

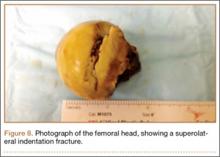

The 16×9.5×9-cm mass (Figure 5A) had a conglomerated internal structure (Figure 5B). Multiple specimens from the intra- and extra-articular portions of the mass were sent for histopathologic analysis, which revealed clusters of mature chondrocytes arranged in a lobular pattern and separated by thin fibrous bands. Areas of calcification and ossification were appreciated as well (Figures 6A-6C). No necrosis, mitosis, or bone permeation was detected. These findings were compatible with typical SCM. Given these pathologic findings and the lack of clinical deterioration over the previous year, a diagnosis of GSSCM with extension along the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursae was made. The already-performed marginal excision was deemed sufficient treatment. At most recent follow-up, 38 months after surgery, the patient was pain-free and had good hip range of motion and no indication of recurrence.

Discussion

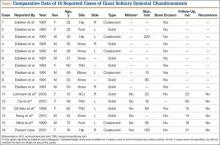

SCM is a benign disorder emerging from the synovium as a result of proliferative changes in the synovial membrane of the joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae, leading to the formation of numerous cartilaginous nodules, usually a few millimeters in diameter.8 In a rare presentation of the disease, the nodules may coalesce to form a large mass, or a single cartilaginous nodule may enlarge to form a mass. Edeiken and colleagues7 named this previously unrecognized SCM feature as GSSCM when there was a major single mass larger than 1 cm in diameter. There have been other SCM cases with multiple giant masses.9,10 In the English-language literature, we found 15 GSSCM cases, which include the first reported, by Edeiken and colleagues7 (Table). However, earlier SCM cases would be reclassified GSSCM according to their definition.11

The present case brings the total to 16. Nine of the 16 patients were male. Mean age at presentation was 41 years (range, 10-80 years). The knee was the most common GSSCM site (6 cases), followed by the temporomandibular and hip joints (3 each). Regarding gross pathology, 10 lesions were solid, and 6 (including the present one) were formed by conglomeration of the chondromatosis nodules. Lesions varied in size (16-200 mm), and 2 were primarily extra-articular (foot). One common issue with most of the cases was the initial diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. The exact surgical technique used was described for 6 cases (cases 11-16); the technique was marginal excision. In no case was recurrence 14 to 60 months after surgery reported.

This chondroproliferative process is potentially a diagnostic challenge, as distinguishing it from a chondrosarcoma, a more common lesion, could be difficult based on clinical and imaging findings, and, as is true for other chondral lesions, even histologic differentiation of the conditions might not be conclusive.12,13 Confusion in diagnosis was almost universal in this series of patients.

One important differentiating feature of benign and malignant skeletal lesions is the time course of the disease. Malignant tumors are expected to demonstrate rapid enlargement and local or systemic spread. Unfortunately, often SCS cannot be distinguished by this characteristic, as grade I or II chondrosarcoma is usually a slow-growing tumor and does not metastasize early.14 Although lack of recurrence is assuring, recurrence is not necessarily a sign of malignancy, as a considerable percentage of benign chondromatosis lesions recur.8

Radiologic differentiation between SCM and SCS is another challenge. Although bone erosion caused by a lesion not originating from bone is usually considered a sign of malignancy, GSSCM was reported as causing bone erosion in 5 of the 16 cases in our literature review.7,15 Our patient did not experience any bone erosion. However, lack of bone erosion is not a reliable criterion for excluding SCS, and bone erosion was noted in only 3 of the 9 SCS cases in the series reported by Bertoni and colleagues.6 Moreover, tumor size and propagation of tumor to surrounding tissue could be surprising in GSSCM. Large size (up to 20 cm) and extra-articular spread of a lesion originating in a joint are common findings.6,16 Our case was an obvious extension of a hip GSSCM to the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursa, which is the most common pattern of extracapsular spread of hip SCM.17 An interesting feature of the present case, however, was the relatively superficial location of the mass immediately under the fascia.

Calcified matrix is key in diagnosing a chondral lesion on imaging studies, but, in some cases, SCM does not demonstrate any radiographically detectable calcification at time of diagnosis.18 However, all the GSSCM cases reported to date had obvious calcified matrix.

The hypercellularity, cellular atypia, binucleated cells, and pleomorphism in the histologic examination of the present case are not features of malignancy in SCM.8 On the contrary, several other characteristics, including qualitative differences in the arrangement of chondrocytes (sheets rather than clusters), myxoid matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of the nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and, most important, permeation of the trabecular bone with the filling up of marrow spaces, have been assumed to be indicative of malignancy.8 Furthermore, Davis and colleagues8 found no mitotic activity in the histopathologic investigation of 53 SCM cases. Even in 3 cases that developed malignant transformation to SCS, mitosis was not found in the initial biopsy specimens before transformation. This was compatible with the common opinion that SCM is not a neoplastic, but a metaplastic, process. Histopathologic data were available for only 8 of the previous 15 GSSCM cases. There were no reports of mitosis, and necrosis was found in only 1 case.16 In our patient’s case, however, the first biopsy did show remarkable mitotic activity. This was not the case for the second biopsy, when mature chondrocytes associated with marked calcification and ossification were prominent features (Figures 6A, 6B). We presume that, within a limited period during earlier stages of tissue maturation in SCM, mitotic activity might be a possible finding. Of note, none of the other aforementioned histologic criteria for malignancy was seen in the first or second biopsy in the present case (Figures 3, 6C).

The original idea that SCM originates from a metaplasia in the subintimal layer of the synovium, where the synovium is in direct contact with the articular cartilage, has been challenged. The high incidence of hypercellularity, binucleated cells, and cellular atypia was always an argument against a metaplastic origin for the disease. Evidence of clonal chromosomal changes, like translocation of chromosome 1218 and chromosome 5 and 6 abnormalities,19,20 in addition to other alterations,19,21 provide some evidence supporting a neoplastic rather than a metaplastic origin for SCM. Given the presence of mitosis in the present case, the lack of mitotic activity in SCM, as stated by other authors,22 is not a universal feature and cannot be used as an argument against a neoplastic origin for SCM.

Although mitotic activity is uncommon in SCM, the present case illustrates the possible presence of mitotic activity in GSSCM. The simple presence of mitotic activity, a common finding in some other chondral tumors,23,24 does not preclude the diagnosis of benign SCM, as suggested before,8 and correlation of the clinical and radiologic manifestations with histopathologic findings is crucial for a correct diagnosis.

1. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

2. Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg. 1976;19(2):151-158.

3. Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1465-1488.

4. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis in association with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(145):179-182.

5. Sim FH, Dahlin DC, Ivins JC. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(4):492-495.

6. Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer. 1991;67(1):155-162.

7. Edeiken J, Edeiken BS, Ayala AG, Raymond AK, Murray JA, Guo SQ. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(1):23-29.

8. Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: a clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(7):683-688.

9. Goel A, Cullen C, Paul AS, Freemont AJ. Multiple giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee. Knee. 2001;8(3):243-245.

10. Dogan A, Harman M, Uslu M, Bayram I, Akpinar F. Rocky form giant synovial chondromatosis: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(5):465-468.

11. Eisenberg KS, Johnston JO. Synovial chondromatosis of the hip joint presenting as an intrapelvic mass: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):176-178.

12. Lohmann CH, Köster G, Klinger HM, Kunze E. Giant synovial osteochondromatosis of the acromio-clavicular joint in a child. A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(2):126-128.

13. Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Wang BL. Arthroscopically guided removal of large solitary synovial chondromatosis from the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(12):1236-1239.

14. Gil-Salu JL, Lazaro R, Aldasoro J, Gonzalez-Darder JM. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with intracranial extension. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(2):99-104.

15. Kang CH, Park JH, Lee DH, Kim CH, Park JM, Lee WS. Giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee mimicking a parosteal osteosarcoma: a case report. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 2010;16(2):95-98.

16. Nihal A, Read CJ, Henderson DC, Malcolm AJ. Extra-articular giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the foot: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Surg. 1999;5(1):29-32.

17. Robinson P, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS, Wunder JS. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip: extracapsular patterns of spread. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(4):210-215.

18. Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, et al. Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group. J Pathol. 2002;196(2):194-203.

19. Sah AP, Geller DS, Mankin HJ, et al. Malignant transformation of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder to chondrosarcoma. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1321-1328.

20. Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, Nelson M, Liu J, Bridge JA. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;140(1):18-22.

21. Rizzo M, Ghert MA, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma of bone: analysis of 108 cases and evaluation for predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391):224-233.

22. Davis RI, Foster H, Arthur K, Trewin S, Hamilton PW, Biggart DJ. Cell proliferation studies in primary synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 1998;184(1):18-23.

23. Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Onizawa K, et al. Chondroblastoma of the temporal base with high mitotic activity. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(11):516-520.

24. Kirin I, Jurisic D, Mokrovic H, Stanec Z, Stalekar H. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the second metacarpal bone—a case report. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(3):929-931.

Synovial chondromatosis (SCM) is a relatively rare benign lesion of the synovium.1 Its pathogenesis has been thought to be a chondral metaplasia of the subintimal layer of the intra- or extra-articular synovium.2 However, evidence supporting a neoplastic cause of the disease is emerging.3 When intra-articular, any joint can be affected, though large joints are more prone to the disease; the knee, hip, and elbow are the most common locations.4 The synovial layer of tendons or bursae can be the origin of extra-articular SCM.5

Synovial chondrosarcoma (SCS), an even rarer pathology, can be caused by malignant transformation of SCM or can appear de novo on a synovial background.6 Histologic differentiation from SCM might be difficult because of the high incidence of hypercellularity, cellular atypia, and binucleated cells.6 Some features, such as presence of a very large mass or erosion of the surrounding bones, have been indicated as possible signs of malignancy.3 An unusual presentation of SCM, giant solitary synovial chondromatosis (GSSCM), can be hard to distinguish from SCS because of the large volume and possible aggressive radiologic findings.7 Some histologic features, such as presence of necrosis and mitotic cells, have been suggested as distinctive criteria for malignancy.8

In this article, we present a case of benign GSSCM with a histologic feature that has not been considered typical for benign SCM. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

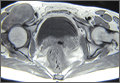

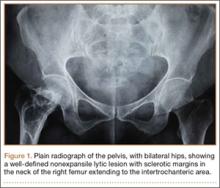

An 18-year-old woman presented with a large mass over the right hip. The mass had been growing slowly for 2 years. One year before presentation, a radiograph showed a large hip mass with fluffy calcification (Figure 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large nonhomogeneous mass anterior to the hip capsule and extending into the hip joint back to the posterior part of the joint (Figures 2A, 2B). Open incisional biopsy was performed in a local hospital at the time, and the histologic analysis revealed presence of atypical binucleated cells and pleomorphism, in addition to some mitotic activity (0 to 1 per high-power field) (Figure 3). These findings suggested malignancy. The patient declined surgery up until the time she presented to our hospital, 1 year later.

Clinical examination findings on admission to our hospital were striking. The patient had a large mass in the groin region. It was fairly tender and firm to palpation, immobile, and close to the skin. Hip motion was mildly painful but obviously restricted.

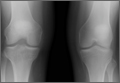

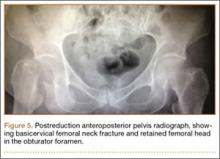

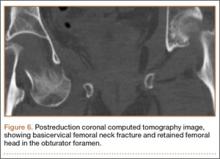

The mass was restaged. New radiographs and MRI did not show any significant changes since the previous year, computed tomography (CT) did not show any bone erosion (Figure 4), and chest radiograph, CT, and whole-body bone scan did not demonstrate any signs of metastasis.

Given the clinical presentation and previous histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of GSSCM with possible malignant transformation was made. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During surgery, the tumor was exposed through the Smith-Petersen approach. The mass was extruding under the fascia between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and iliopsoas muscle laterally. There was no adhesion of the surrounding structures, including the femoral neurovascular bundle, to the mass. The muscle was sitting on the anterolateral surface of the mass, which was considered located in the iliopsoas bursa but extending to the joint. In the vertical plane, the mass extended down to the subtrochanteric area. The entire solid extra-articular mass was excised en bloc, and hip capsulotomy was performed inferior to the area of emergence of the mass. The joint was occupied by a single solid cartilaginous mass molding around the femoral neck, filling the piriformis fossa and propagating to the posterior joint space. Obtaining enough exposure to the back of the joint required surgical hip dislocation. The visualized acetabular fossa revealed chondral fragments, which were excised. Bone erosion or significant osteoarthritis was not detected in any part of the joint. A nearly total synovectomy was performed, leaving the ascending retinacular vessels intact. Meticulous technique was used to avoid contaminating the extra-articular tissues. The wound was closed in the routine way after hip relocation.

The 16×9.5×9-cm mass (Figure 5A) had a conglomerated internal structure (Figure 5B). Multiple specimens from the intra- and extra-articular portions of the mass were sent for histopathologic analysis, which revealed clusters of mature chondrocytes arranged in a lobular pattern and separated by thin fibrous bands. Areas of calcification and ossification were appreciated as well (Figures 6A-6C). No necrosis, mitosis, or bone permeation was detected. These findings were compatible with typical SCM. Given these pathologic findings and the lack of clinical deterioration over the previous year, a diagnosis of GSSCM with extension along the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursae was made. The already-performed marginal excision was deemed sufficient treatment. At most recent follow-up, 38 months after surgery, the patient was pain-free and had good hip range of motion and no indication of recurrence.

Discussion

SCM is a benign disorder emerging from the synovium as a result of proliferative changes in the synovial membrane of the joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae, leading to the formation of numerous cartilaginous nodules, usually a few millimeters in diameter.8 In a rare presentation of the disease, the nodules may coalesce to form a large mass, or a single cartilaginous nodule may enlarge to form a mass. Edeiken and colleagues7 named this previously unrecognized SCM feature as GSSCM when there was a major single mass larger than 1 cm in diameter. There have been other SCM cases with multiple giant masses.9,10 In the English-language literature, we found 15 GSSCM cases, which include the first reported, by Edeiken and colleagues7 (Table). However, earlier SCM cases would be reclassified GSSCM according to their definition.11

The present case brings the total to 16. Nine of the 16 patients were male. Mean age at presentation was 41 years (range, 10-80 years). The knee was the most common GSSCM site (6 cases), followed by the temporomandibular and hip joints (3 each). Regarding gross pathology, 10 lesions were solid, and 6 (including the present one) were formed by conglomeration of the chondromatosis nodules. Lesions varied in size (16-200 mm), and 2 were primarily extra-articular (foot). One common issue with most of the cases was the initial diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. The exact surgical technique used was described for 6 cases (cases 11-16); the technique was marginal excision. In no case was recurrence 14 to 60 months after surgery reported.

This chondroproliferative process is potentially a diagnostic challenge, as distinguishing it from a chondrosarcoma, a more common lesion, could be difficult based on clinical and imaging findings, and, as is true for other chondral lesions, even histologic differentiation of the conditions might not be conclusive.12,13 Confusion in diagnosis was almost universal in this series of patients.

One important differentiating feature of benign and malignant skeletal lesions is the time course of the disease. Malignant tumors are expected to demonstrate rapid enlargement and local or systemic spread. Unfortunately, often SCS cannot be distinguished by this characteristic, as grade I or II chondrosarcoma is usually a slow-growing tumor and does not metastasize early.14 Although lack of recurrence is assuring, recurrence is not necessarily a sign of malignancy, as a considerable percentage of benign chondromatosis lesions recur.8

Radiologic differentiation between SCM and SCS is another challenge. Although bone erosion caused by a lesion not originating from bone is usually considered a sign of malignancy, GSSCM was reported as causing bone erosion in 5 of the 16 cases in our literature review.7,15 Our patient did not experience any bone erosion. However, lack of bone erosion is not a reliable criterion for excluding SCS, and bone erosion was noted in only 3 of the 9 SCS cases in the series reported by Bertoni and colleagues.6 Moreover, tumor size and propagation of tumor to surrounding tissue could be surprising in GSSCM. Large size (up to 20 cm) and extra-articular spread of a lesion originating in a joint are common findings.6,16 Our case was an obvious extension of a hip GSSCM to the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursa, which is the most common pattern of extracapsular spread of hip SCM.17 An interesting feature of the present case, however, was the relatively superficial location of the mass immediately under the fascia.

Calcified matrix is key in diagnosing a chondral lesion on imaging studies, but, in some cases, SCM does not demonstrate any radiographically detectable calcification at time of diagnosis.18 However, all the GSSCM cases reported to date had obvious calcified matrix.

The hypercellularity, cellular atypia, binucleated cells, and pleomorphism in the histologic examination of the present case are not features of malignancy in SCM.8 On the contrary, several other characteristics, including qualitative differences in the arrangement of chondrocytes (sheets rather than clusters), myxoid matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of the nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and, most important, permeation of the trabecular bone with the filling up of marrow spaces, have been assumed to be indicative of malignancy.8 Furthermore, Davis and colleagues8 found no mitotic activity in the histopathologic investigation of 53 SCM cases. Even in 3 cases that developed malignant transformation to SCS, mitosis was not found in the initial biopsy specimens before transformation. This was compatible with the common opinion that SCM is not a neoplastic, but a metaplastic, process. Histopathologic data were available for only 8 of the previous 15 GSSCM cases. There were no reports of mitosis, and necrosis was found in only 1 case.16 In our patient’s case, however, the first biopsy did show remarkable mitotic activity. This was not the case for the second biopsy, when mature chondrocytes associated with marked calcification and ossification were prominent features (Figures 6A, 6B). We presume that, within a limited period during earlier stages of tissue maturation in SCM, mitotic activity might be a possible finding. Of note, none of the other aforementioned histologic criteria for malignancy was seen in the first or second biopsy in the present case (Figures 3, 6C).

The original idea that SCM originates from a metaplasia in the subintimal layer of the synovium, where the synovium is in direct contact with the articular cartilage, has been challenged. The high incidence of hypercellularity, binucleated cells, and cellular atypia was always an argument against a metaplastic origin for the disease. Evidence of clonal chromosomal changes, like translocation of chromosome 1218 and chromosome 5 and 6 abnormalities,19,20 in addition to other alterations,19,21 provide some evidence supporting a neoplastic rather than a metaplastic origin for SCM. Given the presence of mitosis in the present case, the lack of mitotic activity in SCM, as stated by other authors,22 is not a universal feature and cannot be used as an argument against a neoplastic origin for SCM.

Although mitotic activity is uncommon in SCM, the present case illustrates the possible presence of mitotic activity in GSSCM. The simple presence of mitotic activity, a common finding in some other chondral tumors,23,24 does not preclude the diagnosis of benign SCM, as suggested before,8 and correlation of the clinical and radiologic manifestations with histopathologic findings is crucial for a correct diagnosis.

Synovial chondromatosis (SCM) is a relatively rare benign lesion of the synovium.1 Its pathogenesis has been thought to be a chondral metaplasia of the subintimal layer of the intra- or extra-articular synovium.2 However, evidence supporting a neoplastic cause of the disease is emerging.3 When intra-articular, any joint can be affected, though large joints are more prone to the disease; the knee, hip, and elbow are the most common locations.4 The synovial layer of tendons or bursae can be the origin of extra-articular SCM.5

Synovial chondrosarcoma (SCS), an even rarer pathology, can be caused by malignant transformation of SCM or can appear de novo on a synovial background.6 Histologic differentiation from SCM might be difficult because of the high incidence of hypercellularity, cellular atypia, and binucleated cells.6 Some features, such as presence of a very large mass or erosion of the surrounding bones, have been indicated as possible signs of malignancy.3 An unusual presentation of SCM, giant solitary synovial chondromatosis (GSSCM), can be hard to distinguish from SCS because of the large volume and possible aggressive radiologic findings.7 Some histologic features, such as presence of necrosis and mitotic cells, have been suggested as distinctive criteria for malignancy.8

In this article, we present a case of benign GSSCM with a histologic feature that has not been considered typical for benign SCM. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman presented with a large mass over the right hip. The mass had been growing slowly for 2 years. One year before presentation, a radiograph showed a large hip mass with fluffy calcification (Figure 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large nonhomogeneous mass anterior to the hip capsule and extending into the hip joint back to the posterior part of the joint (Figures 2A, 2B). Open incisional biopsy was performed in a local hospital at the time, and the histologic analysis revealed presence of atypical binucleated cells and pleomorphism, in addition to some mitotic activity (0 to 1 per high-power field) (Figure 3). These findings suggested malignancy. The patient declined surgery up until the time she presented to our hospital, 1 year later.

Clinical examination findings on admission to our hospital were striking. The patient had a large mass in the groin region. It was fairly tender and firm to palpation, immobile, and close to the skin. Hip motion was mildly painful but obviously restricted.

The mass was restaged. New radiographs and MRI did not show any significant changes since the previous year, computed tomography (CT) did not show any bone erosion (Figure 4), and chest radiograph, CT, and whole-body bone scan did not demonstrate any signs of metastasis.

Given the clinical presentation and previous histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of GSSCM with possible malignant transformation was made. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During surgery, the tumor was exposed through the Smith-Petersen approach. The mass was extruding under the fascia between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and iliopsoas muscle laterally. There was no adhesion of the surrounding structures, including the femoral neurovascular bundle, to the mass. The muscle was sitting on the anterolateral surface of the mass, which was considered located in the iliopsoas bursa but extending to the joint. In the vertical plane, the mass extended down to the subtrochanteric area. The entire solid extra-articular mass was excised en bloc, and hip capsulotomy was performed inferior to the area of emergence of the mass. The joint was occupied by a single solid cartilaginous mass molding around the femoral neck, filling the piriformis fossa and propagating to the posterior joint space. Obtaining enough exposure to the back of the joint required surgical hip dislocation. The visualized acetabular fossa revealed chondral fragments, which were excised. Bone erosion or significant osteoarthritis was not detected in any part of the joint. A nearly total synovectomy was performed, leaving the ascending retinacular vessels intact. Meticulous technique was used to avoid contaminating the extra-articular tissues. The wound was closed in the routine way after hip relocation.

The 16×9.5×9-cm mass (Figure 5A) had a conglomerated internal structure (Figure 5B). Multiple specimens from the intra- and extra-articular portions of the mass were sent for histopathologic analysis, which revealed clusters of mature chondrocytes arranged in a lobular pattern and separated by thin fibrous bands. Areas of calcification and ossification were appreciated as well (Figures 6A-6C). No necrosis, mitosis, or bone permeation was detected. These findings were compatible with typical SCM. Given these pathologic findings and the lack of clinical deterioration over the previous year, a diagnosis of GSSCM with extension along the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursae was made. The already-performed marginal excision was deemed sufficient treatment. At most recent follow-up, 38 months after surgery, the patient was pain-free and had good hip range of motion and no indication of recurrence.

Discussion

SCM is a benign disorder emerging from the synovium as a result of proliferative changes in the synovial membrane of the joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae, leading to the formation of numerous cartilaginous nodules, usually a few millimeters in diameter.8 In a rare presentation of the disease, the nodules may coalesce to form a large mass, or a single cartilaginous nodule may enlarge to form a mass. Edeiken and colleagues7 named this previously unrecognized SCM feature as GSSCM when there was a major single mass larger than 1 cm in diameter. There have been other SCM cases with multiple giant masses.9,10 In the English-language literature, we found 15 GSSCM cases, which include the first reported, by Edeiken and colleagues7 (Table). However, earlier SCM cases would be reclassified GSSCM according to their definition.11

The present case brings the total to 16. Nine of the 16 patients were male. Mean age at presentation was 41 years (range, 10-80 years). The knee was the most common GSSCM site (6 cases), followed by the temporomandibular and hip joints (3 each). Regarding gross pathology, 10 lesions were solid, and 6 (including the present one) were formed by conglomeration of the chondromatosis nodules. Lesions varied in size (16-200 mm), and 2 were primarily extra-articular (foot). One common issue with most of the cases was the initial diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. The exact surgical technique used was described for 6 cases (cases 11-16); the technique was marginal excision. In no case was recurrence 14 to 60 months after surgery reported.

This chondroproliferative process is potentially a diagnostic challenge, as distinguishing it from a chondrosarcoma, a more common lesion, could be difficult based on clinical and imaging findings, and, as is true for other chondral lesions, even histologic differentiation of the conditions might not be conclusive.12,13 Confusion in diagnosis was almost universal in this series of patients.

One important differentiating feature of benign and malignant skeletal lesions is the time course of the disease. Malignant tumors are expected to demonstrate rapid enlargement and local or systemic spread. Unfortunately, often SCS cannot be distinguished by this characteristic, as grade I or II chondrosarcoma is usually a slow-growing tumor and does not metastasize early.14 Although lack of recurrence is assuring, recurrence is not necessarily a sign of malignancy, as a considerable percentage of benign chondromatosis lesions recur.8

Radiologic differentiation between SCM and SCS is another challenge. Although bone erosion caused by a lesion not originating from bone is usually considered a sign of malignancy, GSSCM was reported as causing bone erosion in 5 of the 16 cases in our literature review.7,15 Our patient did not experience any bone erosion. However, lack of bone erosion is not a reliable criterion for excluding SCS, and bone erosion was noted in only 3 of the 9 SCS cases in the series reported by Bertoni and colleagues.6 Moreover, tumor size and propagation of tumor to surrounding tissue could be surprising in GSSCM. Large size (up to 20 cm) and extra-articular spread of a lesion originating in a joint are common findings.6,16 Our case was an obvious extension of a hip GSSCM to the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursa, which is the most common pattern of extracapsular spread of hip SCM.17 An interesting feature of the present case, however, was the relatively superficial location of the mass immediately under the fascia.

Calcified matrix is key in diagnosing a chondral lesion on imaging studies, but, in some cases, SCM does not demonstrate any radiographically detectable calcification at time of diagnosis.18 However, all the GSSCM cases reported to date had obvious calcified matrix.

The hypercellularity, cellular atypia, binucleated cells, and pleomorphism in the histologic examination of the present case are not features of malignancy in SCM.8 On the contrary, several other characteristics, including qualitative differences in the arrangement of chondrocytes (sheets rather than clusters), myxoid matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of the nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and, most important, permeation of the trabecular bone with the filling up of marrow spaces, have been assumed to be indicative of malignancy.8 Furthermore, Davis and colleagues8 found no mitotic activity in the histopathologic investigation of 53 SCM cases. Even in 3 cases that developed malignant transformation to SCS, mitosis was not found in the initial biopsy specimens before transformation. This was compatible with the common opinion that SCM is not a neoplastic, but a metaplastic, process. Histopathologic data were available for only 8 of the previous 15 GSSCM cases. There were no reports of mitosis, and necrosis was found in only 1 case.16 In our patient’s case, however, the first biopsy did show remarkable mitotic activity. This was not the case for the second biopsy, when mature chondrocytes associated with marked calcification and ossification were prominent features (Figures 6A, 6B). We presume that, within a limited period during earlier stages of tissue maturation in SCM, mitotic activity might be a possible finding. Of note, none of the other aforementioned histologic criteria for malignancy was seen in the first or second biopsy in the present case (Figures 3, 6C).

The original idea that SCM originates from a metaplasia in the subintimal layer of the synovium, where the synovium is in direct contact with the articular cartilage, has been challenged. The high incidence of hypercellularity, binucleated cells, and cellular atypia was always an argument against a metaplastic origin for the disease. Evidence of clonal chromosomal changes, like translocation of chromosome 1218 and chromosome 5 and 6 abnormalities,19,20 in addition to other alterations,19,21 provide some evidence supporting a neoplastic rather than a metaplastic origin for SCM. Given the presence of mitosis in the present case, the lack of mitotic activity in SCM, as stated by other authors,22 is not a universal feature and cannot be used as an argument against a neoplastic origin for SCM.

Although mitotic activity is uncommon in SCM, the present case illustrates the possible presence of mitotic activity in GSSCM. The simple presence of mitotic activity, a common finding in some other chondral tumors,23,24 does not preclude the diagnosis of benign SCM, as suggested before,8 and correlation of the clinical and radiologic manifestations with histopathologic findings is crucial for a correct diagnosis.

1. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

2. Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg. 1976;19(2):151-158.

3. Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1465-1488.

4. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis in association with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(145):179-182.

5. Sim FH, Dahlin DC, Ivins JC. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(4):492-495.

6. Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer. 1991;67(1):155-162.

7. Edeiken J, Edeiken BS, Ayala AG, Raymond AK, Murray JA, Guo SQ. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(1):23-29.

8. Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: a clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(7):683-688.

9. Goel A, Cullen C, Paul AS, Freemont AJ. Multiple giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee. Knee. 2001;8(3):243-245.

10. Dogan A, Harman M, Uslu M, Bayram I, Akpinar F. Rocky form giant synovial chondromatosis: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(5):465-468.

11. Eisenberg KS, Johnston JO. Synovial chondromatosis of the hip joint presenting as an intrapelvic mass: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):176-178.

12. Lohmann CH, Köster G, Klinger HM, Kunze E. Giant synovial osteochondromatosis of the acromio-clavicular joint in a child. A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(2):126-128.

13. Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Wang BL. Arthroscopically guided removal of large solitary synovial chondromatosis from the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(12):1236-1239.

14. Gil-Salu JL, Lazaro R, Aldasoro J, Gonzalez-Darder JM. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with intracranial extension. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(2):99-104.

15. Kang CH, Park JH, Lee DH, Kim CH, Park JM, Lee WS. Giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee mimicking a parosteal osteosarcoma: a case report. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 2010;16(2):95-98.

16. Nihal A, Read CJ, Henderson DC, Malcolm AJ. Extra-articular giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the foot: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Surg. 1999;5(1):29-32.

17. Robinson P, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS, Wunder JS. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip: extracapsular patterns of spread. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(4):210-215.

18. Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, et al. Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group. J Pathol. 2002;196(2):194-203.

19. Sah AP, Geller DS, Mankin HJ, et al. Malignant transformation of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder to chondrosarcoma. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1321-1328.

20. Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, Nelson M, Liu J, Bridge JA. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;140(1):18-22.

21. Rizzo M, Ghert MA, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma of bone: analysis of 108 cases and evaluation for predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391):224-233.

22. Davis RI, Foster H, Arthur K, Trewin S, Hamilton PW, Biggart DJ. Cell proliferation studies in primary synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 1998;184(1):18-23.

23. Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Onizawa K, et al. Chondroblastoma of the temporal base with high mitotic activity. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(11):516-520.

24. Kirin I, Jurisic D, Mokrovic H, Stanec Z, Stalekar H. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the second metacarpal bone—a case report. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(3):929-931.

1. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

2. Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg. 1976;19(2):151-158.