User login

Topical gel appears safe, effective in CTCL

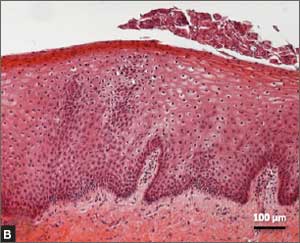

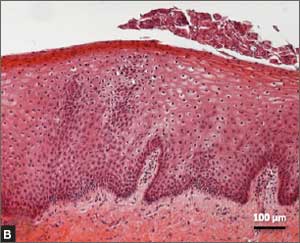

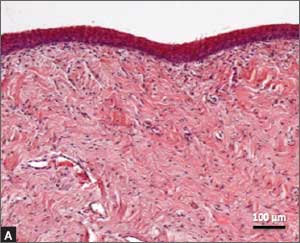

treatment (top) and 16 weeks

after treatment began

Photo from Penn Medicine

Results of a phase 1 trial suggest a topical gel can prompt regression of both treated and untreated lesions in patients with

early stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Of the 12 patients who received the treatment, resiquimod gel, 75% had a significant improvement in treated lesions.

And 92% of patients had a more than 50% improvement in body surface area involvement, which included untreated lesions. Two patients experienced complete disease clearance.

Adverse events associated with resiquimod were largely limited to the skin, although 2 patients had transient, low-grade fever. Five patients developed superficial skin erosions that healed when treatment was stopped and did not reappear after treatment began again.

Alain Rook, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

“The results of the trial suggest that resiquimod is safely and effectively absorbed into the skin and, beyond diminishing treated lesions, also enhances the immune response, leading to healing of even untreated lesions,” Dr Rook said.

“To our knowledge, this is the first topical therapy that can clear untreated lesions and lead to complete remission in some patients.”

Treatment and response

Dr Rook and his colleagues tested resiquimod gel in 12 patients who had previously undergone an average of 6 treatments for early stage CTCL.

The patients applied specified doses of resiquimod (0.03% or 0.06%) to select skin lesions for 16 weeks. Some patients using the 0.06% dose had complete clearance of all malignant cells after 8 weeks.

By the final evaluation, treated lesions had significantly improved in 75% of patients, and 30% of patients had complete clearance of all treated lesions.

Resiquimod also improved untreated lesions, resulting in more than 50% improvement in body surface area involvement for 92% of patients.

Two participants, one of whom had been living with CTCL for more than 15 years without responding to treatment, experienced complete eradication of the disease.

Malignant cell analysis

The researchers used high-throughput sequencing to detect malignant cells in patient samples. The technique could identify a single malignant cell among 100,000 healthy cells.

The team analyzed DNA from biopsies of the same lesion before treatment and 8 weeks after treatment began.

They observed a significant reduction of malignant T cells in 9 of 10 patients tested, 3 of whom had complete eradication of the malignant population and 1 of whom had a 99.6% reduction.

Adverse events

Adverse events associated with resiquimod were all grade 1 and were primarily related to local skin irritation. There were no serious adverse events.

Five of 8 patients receiving resiquimod at the 0.06% dose developed superficial skin erosions at some sites of treatment. These erosions healed completely within a week of stopping treatment and did not recur with re-initiation of treatment.

Two patients receiving the 0.06% dose experienced 2 days of low-grade fever (less than 100.50 F) when treatment began.

“Overall, lesions responded far better to topical resiquimod than they have with other topical therapies, including some potent topical steroids and topical chemotherapy, and [resiquimod] was extremely well tolerated by patients,” Dr Rook said.

“Building upon previous research, our study suggests resiquimod might be useful in combination with other therapies in the treatment of more advanced CTCL. Further research with larger participant populations is needed to determine the best approach and application for these patients.” ![]()

treatment (top) and 16 weeks

after treatment began

Photo from Penn Medicine

Results of a phase 1 trial suggest a topical gel can prompt regression of both treated and untreated lesions in patients with

early stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Of the 12 patients who received the treatment, resiquimod gel, 75% had a significant improvement in treated lesions.

And 92% of patients had a more than 50% improvement in body surface area involvement, which included untreated lesions. Two patients experienced complete disease clearance.

Adverse events associated with resiquimod were largely limited to the skin, although 2 patients had transient, low-grade fever. Five patients developed superficial skin erosions that healed when treatment was stopped and did not reappear after treatment began again.

Alain Rook, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

“The results of the trial suggest that resiquimod is safely and effectively absorbed into the skin and, beyond diminishing treated lesions, also enhances the immune response, leading to healing of even untreated lesions,” Dr Rook said.

“To our knowledge, this is the first topical therapy that can clear untreated lesions and lead to complete remission in some patients.”

Treatment and response

Dr Rook and his colleagues tested resiquimod gel in 12 patients who had previously undergone an average of 6 treatments for early stage CTCL.

The patients applied specified doses of resiquimod (0.03% or 0.06%) to select skin lesions for 16 weeks. Some patients using the 0.06% dose had complete clearance of all malignant cells after 8 weeks.

By the final evaluation, treated lesions had significantly improved in 75% of patients, and 30% of patients had complete clearance of all treated lesions.

Resiquimod also improved untreated lesions, resulting in more than 50% improvement in body surface area involvement for 92% of patients.

Two participants, one of whom had been living with CTCL for more than 15 years without responding to treatment, experienced complete eradication of the disease.

Malignant cell analysis

The researchers used high-throughput sequencing to detect malignant cells in patient samples. The technique could identify a single malignant cell among 100,000 healthy cells.

The team analyzed DNA from biopsies of the same lesion before treatment and 8 weeks after treatment began.

They observed a significant reduction of malignant T cells in 9 of 10 patients tested, 3 of whom had complete eradication of the malignant population and 1 of whom had a 99.6% reduction.

Adverse events

Adverse events associated with resiquimod were all grade 1 and were primarily related to local skin irritation. There were no serious adverse events.

Five of 8 patients receiving resiquimod at the 0.06% dose developed superficial skin erosions at some sites of treatment. These erosions healed completely within a week of stopping treatment and did not recur with re-initiation of treatment.

Two patients receiving the 0.06% dose experienced 2 days of low-grade fever (less than 100.50 F) when treatment began.

“Overall, lesions responded far better to topical resiquimod than they have with other topical therapies, including some potent topical steroids and topical chemotherapy, and [resiquimod] was extremely well tolerated by patients,” Dr Rook said.

“Building upon previous research, our study suggests resiquimod might be useful in combination with other therapies in the treatment of more advanced CTCL. Further research with larger participant populations is needed to determine the best approach and application for these patients.” ![]()

treatment (top) and 16 weeks

after treatment began

Photo from Penn Medicine

Results of a phase 1 trial suggest a topical gel can prompt regression of both treated and untreated lesions in patients with

early stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Of the 12 patients who received the treatment, resiquimod gel, 75% had a significant improvement in treated lesions.

And 92% of patients had a more than 50% improvement in body surface area involvement, which included untreated lesions. Two patients experienced complete disease clearance.

Adverse events associated with resiquimod were largely limited to the skin, although 2 patients had transient, low-grade fever. Five patients developed superficial skin erosions that healed when treatment was stopped and did not reappear after treatment began again.

Alain Rook, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

“The results of the trial suggest that resiquimod is safely and effectively absorbed into the skin and, beyond diminishing treated lesions, also enhances the immune response, leading to healing of even untreated lesions,” Dr Rook said.

“To our knowledge, this is the first topical therapy that can clear untreated lesions and lead to complete remission in some patients.”

Treatment and response

Dr Rook and his colleagues tested resiquimod gel in 12 patients who had previously undergone an average of 6 treatments for early stage CTCL.

The patients applied specified doses of resiquimod (0.03% or 0.06%) to select skin lesions for 16 weeks. Some patients using the 0.06% dose had complete clearance of all malignant cells after 8 weeks.

By the final evaluation, treated lesions had significantly improved in 75% of patients, and 30% of patients had complete clearance of all treated lesions.

Resiquimod also improved untreated lesions, resulting in more than 50% improvement in body surface area involvement for 92% of patients.

Two participants, one of whom had been living with CTCL for more than 15 years without responding to treatment, experienced complete eradication of the disease.

Malignant cell analysis

The researchers used high-throughput sequencing to detect malignant cells in patient samples. The technique could identify a single malignant cell among 100,000 healthy cells.

The team analyzed DNA from biopsies of the same lesion before treatment and 8 weeks after treatment began.

They observed a significant reduction of malignant T cells in 9 of 10 patients tested, 3 of whom had complete eradication of the malignant population and 1 of whom had a 99.6% reduction.

Adverse events

Adverse events associated with resiquimod were all grade 1 and were primarily related to local skin irritation. There were no serious adverse events.

Five of 8 patients receiving resiquimod at the 0.06% dose developed superficial skin erosions at some sites of treatment. These erosions healed completely within a week of stopping treatment and did not recur with re-initiation of treatment.

Two patients receiving the 0.06% dose experienced 2 days of low-grade fever (less than 100.50 F) when treatment began.

“Overall, lesions responded far better to topical resiquimod than they have with other topical therapies, including some potent topical steroids and topical chemotherapy, and [resiquimod] was extremely well tolerated by patients,” Dr Rook said.

“Building upon previous research, our study suggests resiquimod might be useful in combination with other therapies in the treatment of more advanced CTCL. Further research with larger participant populations is needed to determine the best approach and application for these patients.” ![]()

FDA approves IVIG product for kids

Photo by Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an intravenous human immune globulin (IVIG) product (Gammaplex) for pediatric patients age 2 years and older who have primary humoral immunodeficiencies.

This includes, but is not limited to, the humoral immune defect in common variable immunodeficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, congenital agammaglobulinemia, Wiskott Aldrich syndrome, and severe combined immunodeficiencies.

The approval was based on data submitted to the FDA as part of a post-marketing commitment following approval of the product for replacement therapy in adults in 2009.

Data supporting the latest approval came from a study of 25 children and adolescents (ages 3 to 16) with primary immunodeficiencies who were treated with IVIG for 12 months.

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the incidence of serious, acute bacterial infections (SABIs) as defined by the FDA. Secondary endpoints were safety and tolerability.

Throughout the course of the study, there were 2 SABIs—both pneumonia—resulting in an annual SABI event rate of 0.09, well below the maximum SABI event rate of 0.5 per subject required for approval.

Fourteen subjects (56%) had an adverse event that was possibly related to IVIG. Two patients experienced events that were considered definitely related to the treatment—headache, fatigue, and myalgia.

The most common adverse events, occurring in ≥ 5% of subjects, were dyspnea (2/25, 8%), otitis media acute (2/25, 8%), and tonsillar disorder (2/25, 8%).

Two patients had a serious adverse event of lobar pneumonia. Neither of these was considered related to IVIG, and neither met FDA-defined SABI criteria. None of the subjects withdrew from the study due to adverse events.

IVIG is marketed as Gammaplex by Bio Products Laboratory Limited. For more details on the treatment, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an intravenous human immune globulin (IVIG) product (Gammaplex) for pediatric patients age 2 years and older who have primary humoral immunodeficiencies.

This includes, but is not limited to, the humoral immune defect in common variable immunodeficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, congenital agammaglobulinemia, Wiskott Aldrich syndrome, and severe combined immunodeficiencies.

The approval was based on data submitted to the FDA as part of a post-marketing commitment following approval of the product for replacement therapy in adults in 2009.

Data supporting the latest approval came from a study of 25 children and adolescents (ages 3 to 16) with primary immunodeficiencies who were treated with IVIG for 12 months.

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the incidence of serious, acute bacterial infections (SABIs) as defined by the FDA. Secondary endpoints were safety and tolerability.

Throughout the course of the study, there were 2 SABIs—both pneumonia—resulting in an annual SABI event rate of 0.09, well below the maximum SABI event rate of 0.5 per subject required for approval.

Fourteen subjects (56%) had an adverse event that was possibly related to IVIG. Two patients experienced events that were considered definitely related to the treatment—headache, fatigue, and myalgia.

The most common adverse events, occurring in ≥ 5% of subjects, were dyspnea (2/25, 8%), otitis media acute (2/25, 8%), and tonsillar disorder (2/25, 8%).

Two patients had a serious adverse event of lobar pneumonia. Neither of these was considered related to IVIG, and neither met FDA-defined SABI criteria. None of the subjects withdrew from the study due to adverse events.

IVIG is marketed as Gammaplex by Bio Products Laboratory Limited. For more details on the treatment, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an intravenous human immune globulin (IVIG) product (Gammaplex) for pediatric patients age 2 years and older who have primary humoral immunodeficiencies.

This includes, but is not limited to, the humoral immune defect in common variable immunodeficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, congenital agammaglobulinemia, Wiskott Aldrich syndrome, and severe combined immunodeficiencies.

The approval was based on data submitted to the FDA as part of a post-marketing commitment following approval of the product for replacement therapy in adults in 2009.

Data supporting the latest approval came from a study of 25 children and adolescents (ages 3 to 16) with primary immunodeficiencies who were treated with IVIG for 12 months.

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was the incidence of serious, acute bacterial infections (SABIs) as defined by the FDA. Secondary endpoints were safety and tolerability.

Throughout the course of the study, there were 2 SABIs—both pneumonia—resulting in an annual SABI event rate of 0.09, well below the maximum SABI event rate of 0.5 per subject required for approval.

Fourteen subjects (56%) had an adverse event that was possibly related to IVIG. Two patients experienced events that were considered definitely related to the treatment—headache, fatigue, and myalgia.

The most common adverse events, occurring in ≥ 5% of subjects, were dyspnea (2/25, 8%), otitis media acute (2/25, 8%), and tonsillar disorder (2/25, 8%).

Two patients had a serious adverse event of lobar pneumonia. Neither of these was considered related to IVIG, and neither met FDA-defined SABI criteria. None of the subjects withdrew from the study due to adverse events.

IVIG is marketed as Gammaplex by Bio Products Laboratory Limited. For more details on the treatment, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Drug on fast track to treat aHUS

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to OMS721 for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

OMS721 is a monoclonal antibody targeting mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2), a key regulator of the lectin pathway of the complement system.

The FDA previously granted OMS721 orphan designation for the prevention of thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs).

Omeros Corporation, the company developing OMS721, has released results from a phase 1 trial of the drug in healthy subjects and an ongoing phase 2 trial in patients with TMAs, including aHUS.

Early positive responses in the phase 2 trial prompted the initiation of a compassionate use program for OMS721 to allow extended treatment of 2 patients who had completed 4 weeks of dosing.

Phase 1 results

In the phase 1 trial of healthy subjects, OMS721 was well tolerated and prompted a high degree of sustained lectin pathway inhibition, according to researchers.

Seven cohorts of subjects received OMS721 or placebo by either subcutaneous injection or intravenous infusion at increasing dose levels. The researchers observed no drug-related adverse events and no clinically significant abnormalities on laboratory tests or electrocardiograms.

At the highest dose evaluated, both routes of administration prompted inhibition of the lectin pathway and achieved the pharmacologic target of sustained inhibition for at least a week.

Phase 2 results and compassionate use

In the ongoing phase 2 study, all patients are receiving OMS721. The researchers said they have observed treatment-related, clinically meaningful improvements in disease markers among the patients treated thus far.

The first cohort in this trial consisted of 3 aHUS patients treated with the lowest dose of OMS721. All 3 patients had improvements in platelet counts after treatment. Serum haptoglobin improved in 2 patients, normalizing in 1.

Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels remained normal in 1 patient, substantially decreased to close to the normal range in another, and remained elevated in the third. Creatinine levels in the 1 patient with independent renal function improved.

One patient was taken off the trial because of a serious adverse event—a localized inflammatory response often related to certain types of infections, one of which the patient previously had for 3 years while on immunosuppressive therapy. All data to date indicate no active infection in this patient.

The patient relapsed after stopping OMS721 treatment. No other significant safety issues were observed in this trial or the phase 1 trial.

The other 2 aHUS patients in this cohort continue to receive OMS721 as part of a compassionate use program. Based on their improvements in disease markers, an investigator requested that Omeros continue to provide OMS721 to these patients.

Following European regulatory approval, Omeros released the shipment of OMS721 so these patients could continue treatment beyond the period that was initially planned for the phase 2 study.

About fast track and orphan designation

The FDA’s fast track program facilitates the development of drugs intended to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and that have the potential to address unmet medical needs. Fast track status affords the company developing a drug greater access to the FDA in order to expedite the drug’s development, review, and potential approval.

Many drugs that receive fast track designation also receive priority review, and their new drug applications may be accepted by the FDA as a rolling submission, in which portions of an application are reviewed before the complete application is submitted. Priority review and rolling submission can each provide further acceleration of the FDA’s approval process.

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides a drug’s developer with opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, and other benefits. ![]()

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to OMS721 for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

OMS721 is a monoclonal antibody targeting mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2), a key regulator of the lectin pathway of the complement system.

The FDA previously granted OMS721 orphan designation for the prevention of thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs).

Omeros Corporation, the company developing OMS721, has released results from a phase 1 trial of the drug in healthy subjects and an ongoing phase 2 trial in patients with TMAs, including aHUS.

Early positive responses in the phase 2 trial prompted the initiation of a compassionate use program for OMS721 to allow extended treatment of 2 patients who had completed 4 weeks of dosing.

Phase 1 results

In the phase 1 trial of healthy subjects, OMS721 was well tolerated and prompted a high degree of sustained lectin pathway inhibition, according to researchers.

Seven cohorts of subjects received OMS721 or placebo by either subcutaneous injection or intravenous infusion at increasing dose levels. The researchers observed no drug-related adverse events and no clinically significant abnormalities on laboratory tests or electrocardiograms.

At the highest dose evaluated, both routes of administration prompted inhibition of the lectin pathway and achieved the pharmacologic target of sustained inhibition for at least a week.

Phase 2 results and compassionate use

In the ongoing phase 2 study, all patients are receiving OMS721. The researchers said they have observed treatment-related, clinically meaningful improvements in disease markers among the patients treated thus far.

The first cohort in this trial consisted of 3 aHUS patients treated with the lowest dose of OMS721. All 3 patients had improvements in platelet counts after treatment. Serum haptoglobin improved in 2 patients, normalizing in 1.

Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels remained normal in 1 patient, substantially decreased to close to the normal range in another, and remained elevated in the third. Creatinine levels in the 1 patient with independent renal function improved.

One patient was taken off the trial because of a serious adverse event—a localized inflammatory response often related to certain types of infections, one of which the patient previously had for 3 years while on immunosuppressive therapy. All data to date indicate no active infection in this patient.

The patient relapsed after stopping OMS721 treatment. No other significant safety issues were observed in this trial or the phase 1 trial.

The other 2 aHUS patients in this cohort continue to receive OMS721 as part of a compassionate use program. Based on their improvements in disease markers, an investigator requested that Omeros continue to provide OMS721 to these patients.

Following European regulatory approval, Omeros released the shipment of OMS721 so these patients could continue treatment beyond the period that was initially planned for the phase 2 study.

About fast track and orphan designation

The FDA’s fast track program facilitates the development of drugs intended to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and that have the potential to address unmet medical needs. Fast track status affords the company developing a drug greater access to the FDA in order to expedite the drug’s development, review, and potential approval.

Many drugs that receive fast track designation also receive priority review, and their new drug applications may be accepted by the FDA as a rolling submission, in which portions of an application are reviewed before the complete application is submitted. Priority review and rolling submission can each provide further acceleration of the FDA’s approval process.

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides a drug’s developer with opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, and other benefits. ![]()

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to OMS721 for the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

OMS721 is a monoclonal antibody targeting mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2), a key regulator of the lectin pathway of the complement system.

The FDA previously granted OMS721 orphan designation for the prevention of thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs).

Omeros Corporation, the company developing OMS721, has released results from a phase 1 trial of the drug in healthy subjects and an ongoing phase 2 trial in patients with TMAs, including aHUS.

Early positive responses in the phase 2 trial prompted the initiation of a compassionate use program for OMS721 to allow extended treatment of 2 patients who had completed 4 weeks of dosing.

Phase 1 results

In the phase 1 trial of healthy subjects, OMS721 was well tolerated and prompted a high degree of sustained lectin pathway inhibition, according to researchers.

Seven cohorts of subjects received OMS721 or placebo by either subcutaneous injection or intravenous infusion at increasing dose levels. The researchers observed no drug-related adverse events and no clinically significant abnormalities on laboratory tests or electrocardiograms.

At the highest dose evaluated, both routes of administration prompted inhibition of the lectin pathway and achieved the pharmacologic target of sustained inhibition for at least a week.

Phase 2 results and compassionate use

In the ongoing phase 2 study, all patients are receiving OMS721. The researchers said they have observed treatment-related, clinically meaningful improvements in disease markers among the patients treated thus far.

The first cohort in this trial consisted of 3 aHUS patients treated with the lowest dose of OMS721. All 3 patients had improvements in platelet counts after treatment. Serum haptoglobin improved in 2 patients, normalizing in 1.

Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels remained normal in 1 patient, substantially decreased to close to the normal range in another, and remained elevated in the third. Creatinine levels in the 1 patient with independent renal function improved.

One patient was taken off the trial because of a serious adverse event—a localized inflammatory response often related to certain types of infections, one of which the patient previously had for 3 years while on immunosuppressive therapy. All data to date indicate no active infection in this patient.

The patient relapsed after stopping OMS721 treatment. No other significant safety issues were observed in this trial or the phase 1 trial.

The other 2 aHUS patients in this cohort continue to receive OMS721 as part of a compassionate use program. Based on their improvements in disease markers, an investigator requested that Omeros continue to provide OMS721 to these patients.

Following European regulatory approval, Omeros released the shipment of OMS721 so these patients could continue treatment beyond the period that was initially planned for the phase 2 study.

About fast track and orphan designation

The FDA’s fast track program facilitates the development of drugs intended to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and that have the potential to address unmet medical needs. Fast track status affords the company developing a drug greater access to the FDA in order to expedite the drug’s development, review, and potential approval.

Many drugs that receive fast track designation also receive priority review, and their new drug applications may be accepted by the FDA as a rolling submission, in which portions of an application are reviewed before the complete application is submitted. Priority review and rolling submission can each provide further acceleration of the FDA’s approval process.

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides a drug’s developer with opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, and other benefits. ![]()

Method allows for reuse of holdout data sets

Photo by Darren Baker

Researchers say they have devised a method for obtaining statistical validity that allows scientists to reuse their datasets while minimizing the risk of false discoveries.

Historically, to prevent false discoveries, scientists have not been able to reuse data they’ve already tested to test new hypotheses, especially if those new hypotheses were produced after the first round of data analysis.

Such processes may contaminate the data.

This is true even if the data is partitioned into a training set and a holdout set, as is commonly done to help ensure statistical validity.

In this case, Hypotheses generated about correlations between items in the training set can be tested on the holdout set. Real relationships would exist in both sets, while false ones would fail to be replicated.

The problem with using holdouts in that way is that, by nature, they can only be reused if each hypothesis is independent of another. Even a few additional hypotheses chained off one another could quickly lead to false discovery.

So scientists must collect a fresh holdout set each time an analysis depends on the outcomes of previous work.

However, Cynthia Dwork, PhD, of Microsoft Research in Mountain View, California, and her colleagues say they have devised a method that allows scientists to reuse a holdout set many times while still guaranteeing statistical validity.

The researchers described this method in Science.

With the new method, scientists do not test hypotheses on the holdout set directly. Instead, they query the set through a differentially private algorithm.

A differentially private algorithm guarantees that analyses remain functionally identical when applied to two different datasets: one with and one without the data from any single individual.

This means any findings that would rely on idiosyncratic outliers of a given set would disappear when looking at data through a differentially private lens.

To test their algorithm, Dr Dwork and her colleagues performed adaptive analysis on a data set rigged so that it contained nothing but random noise. The set was abstract but could be thought of as one that tested 20,000 patients on 10,000 variables, such as variants in their genomes, for ones that were predictive of lung cancer.

Though, by design, none of the variables in the set were predictive of cancer, reuse of a holdout set in the standard way showed that 500 of the variables had significant predictive power. Performing the same analysis with the researchers’ reusable holdout tool, however, correctly showed the lack of meaningful correlations.

An experiment with a second rigged dataset depicted a more realistic scenario. There, some of the variables did have predictive power, but traditional holdout use created a combination of variables that wildly overestimated this power. The reusable holdout tool correctly identified the 20 that had true statistical significance.

Dr Dwork and her colleagues say their reusable holdout method can prevent accidental overfitting, where predictive trends only apply to a given dataset and can’t be generalized.

And their method can warn users when they are exhausting the validity of a dataset. This is a red flag for what is known as P-hacking, or intentionally gaming data to get a publishable level of significance.

In these ways, the researchers believe that implementing the reusable holdout algorithm will allow scientists to generate stronger, more generalizable findings from smaller amounts of data. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

Researchers say they have devised a method for obtaining statistical validity that allows scientists to reuse their datasets while minimizing the risk of false discoveries.

Historically, to prevent false discoveries, scientists have not been able to reuse data they’ve already tested to test new hypotheses, especially if those new hypotheses were produced after the first round of data analysis.

Such processes may contaminate the data.

This is true even if the data is partitioned into a training set and a holdout set, as is commonly done to help ensure statistical validity.

In this case, Hypotheses generated about correlations between items in the training set can be tested on the holdout set. Real relationships would exist in both sets, while false ones would fail to be replicated.

The problem with using holdouts in that way is that, by nature, they can only be reused if each hypothesis is independent of another. Even a few additional hypotheses chained off one another could quickly lead to false discovery.

So scientists must collect a fresh holdout set each time an analysis depends on the outcomes of previous work.

However, Cynthia Dwork, PhD, of Microsoft Research in Mountain View, California, and her colleagues say they have devised a method that allows scientists to reuse a holdout set many times while still guaranteeing statistical validity.

The researchers described this method in Science.

With the new method, scientists do not test hypotheses on the holdout set directly. Instead, they query the set through a differentially private algorithm.

A differentially private algorithm guarantees that analyses remain functionally identical when applied to two different datasets: one with and one without the data from any single individual.

This means any findings that would rely on idiosyncratic outliers of a given set would disappear when looking at data through a differentially private lens.

To test their algorithm, Dr Dwork and her colleagues performed adaptive analysis on a data set rigged so that it contained nothing but random noise. The set was abstract but could be thought of as one that tested 20,000 patients on 10,000 variables, such as variants in their genomes, for ones that were predictive of lung cancer.

Though, by design, none of the variables in the set were predictive of cancer, reuse of a holdout set in the standard way showed that 500 of the variables had significant predictive power. Performing the same analysis with the researchers’ reusable holdout tool, however, correctly showed the lack of meaningful correlations.

An experiment with a second rigged dataset depicted a more realistic scenario. There, some of the variables did have predictive power, but traditional holdout use created a combination of variables that wildly overestimated this power. The reusable holdout tool correctly identified the 20 that had true statistical significance.

Dr Dwork and her colleagues say their reusable holdout method can prevent accidental overfitting, where predictive trends only apply to a given dataset and can’t be generalized.

And their method can warn users when they are exhausting the validity of a dataset. This is a red flag for what is known as P-hacking, or intentionally gaming data to get a publishable level of significance.

In these ways, the researchers believe that implementing the reusable holdout algorithm will allow scientists to generate stronger, more generalizable findings from smaller amounts of data. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

Researchers say they have devised a method for obtaining statistical validity that allows scientists to reuse their datasets while minimizing the risk of false discoveries.

Historically, to prevent false discoveries, scientists have not been able to reuse data they’ve already tested to test new hypotheses, especially if those new hypotheses were produced after the first round of data analysis.

Such processes may contaminate the data.

This is true even if the data is partitioned into a training set and a holdout set, as is commonly done to help ensure statistical validity.

In this case, Hypotheses generated about correlations between items in the training set can be tested on the holdout set. Real relationships would exist in both sets, while false ones would fail to be replicated.

The problem with using holdouts in that way is that, by nature, they can only be reused if each hypothesis is independent of another. Even a few additional hypotheses chained off one another could quickly lead to false discovery.

So scientists must collect a fresh holdout set each time an analysis depends on the outcomes of previous work.

However, Cynthia Dwork, PhD, of Microsoft Research in Mountain View, California, and her colleagues say they have devised a method that allows scientists to reuse a holdout set many times while still guaranteeing statistical validity.

The researchers described this method in Science.

With the new method, scientists do not test hypotheses on the holdout set directly. Instead, they query the set through a differentially private algorithm.

A differentially private algorithm guarantees that analyses remain functionally identical when applied to two different datasets: one with and one without the data from any single individual.

This means any findings that would rely on idiosyncratic outliers of a given set would disappear when looking at data through a differentially private lens.

To test their algorithm, Dr Dwork and her colleagues performed adaptive analysis on a data set rigged so that it contained nothing but random noise. The set was abstract but could be thought of as one that tested 20,000 patients on 10,000 variables, such as variants in their genomes, for ones that were predictive of lung cancer.

Though, by design, none of the variables in the set were predictive of cancer, reuse of a holdout set in the standard way showed that 500 of the variables had significant predictive power. Performing the same analysis with the researchers’ reusable holdout tool, however, correctly showed the lack of meaningful correlations.

An experiment with a second rigged dataset depicted a more realistic scenario. There, some of the variables did have predictive power, but traditional holdout use created a combination of variables that wildly overestimated this power. The reusable holdout tool correctly identified the 20 that had true statistical significance.

Dr Dwork and her colleagues say their reusable holdout method can prevent accidental overfitting, where predictive trends only apply to a given dataset and can’t be generalized.

And their method can warn users when they are exhausting the validity of a dataset. This is a red flag for what is known as P-hacking, or intentionally gaming data to get a publishable level of significance.

In these ways, the researchers believe that implementing the reusable holdout algorithm will allow scientists to generate stronger, more generalizable findings from smaller amounts of data. ![]()

Round Purple Erythematous Tumors

The Diagnosis: Skin Metastases of Vulvar Carcinoma

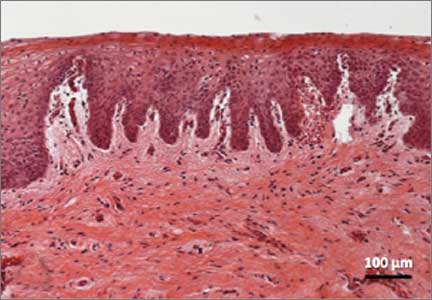

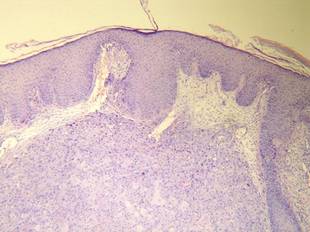

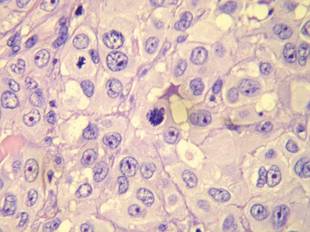

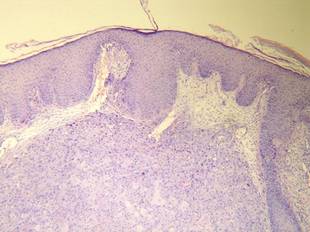

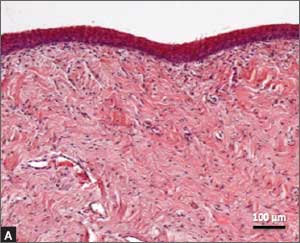

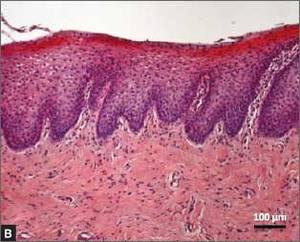

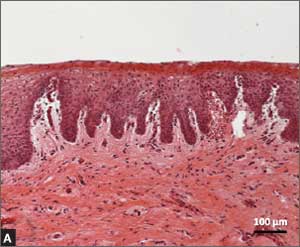

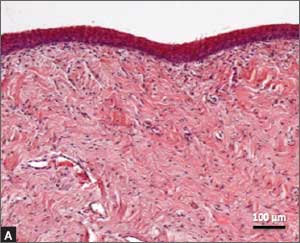

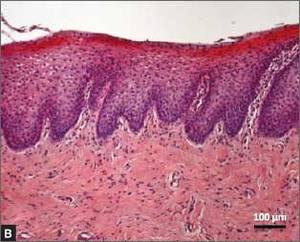

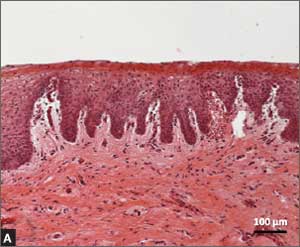

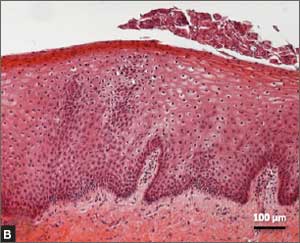

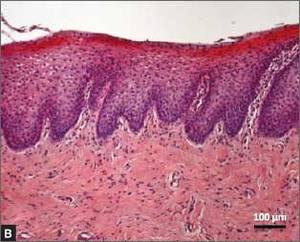

A Tzanck cytodiagnosis was performed and a punch biopsy specimen was obtained for histologic examination. The patient’s Tzanck cytodiagnosis was initially interpreted as a viral cytopathic effect due to the presence of multinucleated atypical cells; hence, she was treated with intravenous acyclovir. The biopsy specimen showed a preserved epidermis and a dense infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 1) formed by atypical squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and anisokaryosis, evident nucleoli, atypical mitoses, and multinucleated cells (Figure 2). The histopathologic diagnosis was skin metastases of moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The subsequent clinical course was unfavorableand the patient died during hospitalization from septic shock.

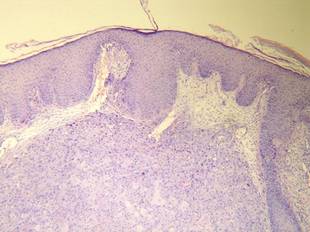

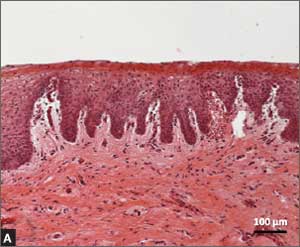

Figure 1. Histology revealed a preserved epidermis with a dense infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

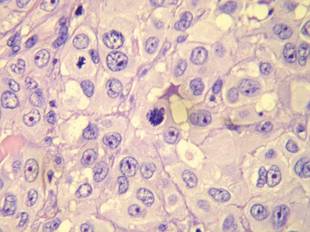

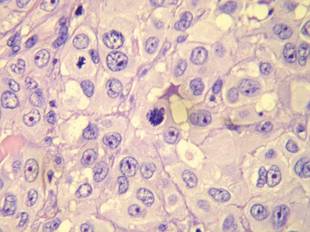

Figure 2. Atypical squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and anisokaryosis, evident nucleoli, atypical mitoses, and multinucleated cells were evident (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of solid tumors in advanced stages of disease progression or occasionally as an initial manifestation; they are a predictor of poor prognosis and breast cancer is the most frequent cause in women.1 Vulvar carcinoma comprises 5% of all malignant neoplasms of the female genital tract and 95% are squamous cell carcinoma; metastases appear most frequently in the inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes, followed by the lungs, liver, and bones.2 Skin metastases are extremely rare, with few cases documented.2,3

Clinically, skin metastases present most frequently as nodules, either solitary or multiple, that are sometimes ulcerated. However, a wide spectrum of metastases has been described, including erysipeloid, sclerodermiform (en cuirasse), telangiectatic papulovesicles, purpuric plaques mimicking vasculitis, alopecia areata–like scalp lesions, and others. The zosteriform pattern has been described in few cases, including vesiculobullous herpetiform lesions or nodular metastases with metameric distribution.4 In more than half of cases, the lesions were initially interpreted as herpes zoster and hence treated with acyclovir.5

Regarding cutaneous metastases of vulvar carcinoma, a case of metastases mimicking primary varicella-zoster virus infection has been reported,3 but our case represents a zosteriform pattern, which is unique.

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenic mechanism of zosteriform spread, though none have been adequately proven.4-7 Some of the patients described in the literature had a history of viral infection by serology or polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus in the same dermatome where metastases were observed. It has been suggested that neural damage caused by the herpesvirus results in an immune function impairment of the overlying skin, which consequently may be more receptive to the inflow of metastatic cells. In such cases, the zosteriform pattern could be due to a Wolf or Köbner phenomenon in an area of vulnerable skin.4-9

Other possible explanations for the zosteriform spread are the invasion of perineural lymphatic vessels or of the dorsal root ganglion, direct invasion from deeper structures, or the surgical implantation of neoplastic cells,4-7 though the latter 2 mechanisms do not correspond to true metastases.

1. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2, pt 1):161-182.

2. Wang AR, O’Brien M, Ross R, et al. Epidermotropic metastasis from vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: a rare cutaneous manifestation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1088-1091.

3. Mailhot J, O’Donnell P, Han R, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva mimicking primary varicella-zoster virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e63-e64.

4. Savoia P, Fava P, Deboli T, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases: a literature meta-analysis and a clinical report of three melanoma cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1355-1363.

5. Niiyama S, Satoh K, Kaneko S, et al. Zosteriform skin involvement of nodal T-cell lymphoma: a review of the published work of cutaneous malignancies mimicking herpes zoster. J Dermatol. 2007;34:68-73.

6. Zalaudek I, Leinweber B, Richtig E, et al. Cutaneous zosteriform melanoma metastases arising after herpes zoster infection: a case report and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:635-639.

7. LeSueur BW, Abraham LJ, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:126-128.

8. Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Brunetti G, et al. Opportunistic localization of skin lesions on vulnerable areas. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:483-488.

9. Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

The Diagnosis: Skin Metastases of Vulvar Carcinoma

A Tzanck cytodiagnosis was performed and a punch biopsy specimen was obtained for histologic examination. The patient’s Tzanck cytodiagnosis was initially interpreted as a viral cytopathic effect due to the presence of multinucleated atypical cells; hence, she was treated with intravenous acyclovir. The biopsy specimen showed a preserved epidermis and a dense infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 1) formed by atypical squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and anisokaryosis, evident nucleoli, atypical mitoses, and multinucleated cells (Figure 2). The histopathologic diagnosis was skin metastases of moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The subsequent clinical course was unfavorableand the patient died during hospitalization from septic shock.

Figure 1. Histology revealed a preserved epidermis with a dense infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Atypical squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and anisokaryosis, evident nucleoli, atypical mitoses, and multinucleated cells were evident (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of solid tumors in advanced stages of disease progression or occasionally as an initial manifestation; they are a predictor of poor prognosis and breast cancer is the most frequent cause in women.1 Vulvar carcinoma comprises 5% of all malignant neoplasms of the female genital tract and 95% are squamous cell carcinoma; metastases appear most frequently in the inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes, followed by the lungs, liver, and bones.2 Skin metastases are extremely rare, with few cases documented.2,3

Clinically, skin metastases present most frequently as nodules, either solitary or multiple, that are sometimes ulcerated. However, a wide spectrum of metastases has been described, including erysipeloid, sclerodermiform (en cuirasse), telangiectatic papulovesicles, purpuric plaques mimicking vasculitis, alopecia areata–like scalp lesions, and others. The zosteriform pattern has been described in few cases, including vesiculobullous herpetiform lesions or nodular metastases with metameric distribution.4 In more than half of cases, the lesions were initially interpreted as herpes zoster and hence treated with acyclovir.5

Regarding cutaneous metastases of vulvar carcinoma, a case of metastases mimicking primary varicella-zoster virus infection has been reported,3 but our case represents a zosteriform pattern, which is unique.

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenic mechanism of zosteriform spread, though none have been adequately proven.4-7 Some of the patients described in the literature had a history of viral infection by serology or polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus in the same dermatome where metastases were observed. It has been suggested that neural damage caused by the herpesvirus results in an immune function impairment of the overlying skin, which consequently may be more receptive to the inflow of metastatic cells. In such cases, the zosteriform pattern could be due to a Wolf or Köbner phenomenon in an area of vulnerable skin.4-9

Other possible explanations for the zosteriform spread are the invasion of perineural lymphatic vessels or of the dorsal root ganglion, direct invasion from deeper structures, or the surgical implantation of neoplastic cells,4-7 though the latter 2 mechanisms do not correspond to true metastases.

The Diagnosis: Skin Metastases of Vulvar Carcinoma

A Tzanck cytodiagnosis was performed and a punch biopsy specimen was obtained for histologic examination. The patient’s Tzanck cytodiagnosis was initially interpreted as a viral cytopathic effect due to the presence of multinucleated atypical cells; hence, she was treated with intravenous acyclovir. The biopsy specimen showed a preserved epidermis and a dense infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 1) formed by atypical squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and anisokaryosis, evident nucleoli, atypical mitoses, and multinucleated cells (Figure 2). The histopathologic diagnosis was skin metastases of moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The subsequent clinical course was unfavorableand the patient died during hospitalization from septic shock.

Figure 1. Histology revealed a preserved epidermis with a dense infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Atypical squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and anisokaryosis, evident nucleoli, atypical mitoses, and multinucleated cells were evident (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Cutaneous metastases occur in 0.7% to 9% of solid tumors in advanced stages of disease progression or occasionally as an initial manifestation; they are a predictor of poor prognosis and breast cancer is the most frequent cause in women.1 Vulvar carcinoma comprises 5% of all malignant neoplasms of the female genital tract and 95% are squamous cell carcinoma; metastases appear most frequently in the inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes, followed by the lungs, liver, and bones.2 Skin metastases are extremely rare, with few cases documented.2,3

Clinically, skin metastases present most frequently as nodules, either solitary or multiple, that are sometimes ulcerated. However, a wide spectrum of metastases has been described, including erysipeloid, sclerodermiform (en cuirasse), telangiectatic papulovesicles, purpuric plaques mimicking vasculitis, alopecia areata–like scalp lesions, and others. The zosteriform pattern has been described in few cases, including vesiculobullous herpetiform lesions or nodular metastases with metameric distribution.4 In more than half of cases, the lesions were initially interpreted as herpes zoster and hence treated with acyclovir.5

Regarding cutaneous metastases of vulvar carcinoma, a case of metastases mimicking primary varicella-zoster virus infection has been reported,3 but our case represents a zosteriform pattern, which is unique.

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenic mechanism of zosteriform spread, though none have been adequately proven.4-7 Some of the patients described in the literature had a history of viral infection by serology or polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus in the same dermatome where metastases were observed. It has been suggested that neural damage caused by the herpesvirus results in an immune function impairment of the overlying skin, which consequently may be more receptive to the inflow of metastatic cells. In such cases, the zosteriform pattern could be due to a Wolf or Köbner phenomenon in an area of vulnerable skin.4-9

Other possible explanations for the zosteriform spread are the invasion of perineural lymphatic vessels or of the dorsal root ganglion, direct invasion from deeper structures, or the surgical implantation of neoplastic cells,4-7 though the latter 2 mechanisms do not correspond to true metastases.

1. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2, pt 1):161-182.

2. Wang AR, O’Brien M, Ross R, et al. Epidermotropic metastasis from vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: a rare cutaneous manifestation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1088-1091.

3. Mailhot J, O’Donnell P, Han R, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva mimicking primary varicella-zoster virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e63-e64.

4. Savoia P, Fava P, Deboli T, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases: a literature meta-analysis and a clinical report of three melanoma cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1355-1363.

5. Niiyama S, Satoh K, Kaneko S, et al. Zosteriform skin involvement of nodal T-cell lymphoma: a review of the published work of cutaneous malignancies mimicking herpes zoster. J Dermatol. 2007;34:68-73.

6. Zalaudek I, Leinweber B, Richtig E, et al. Cutaneous zosteriform melanoma metastases arising after herpes zoster infection: a case report and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:635-639.

7. LeSueur BW, Abraham LJ, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:126-128.

8. Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Brunetti G, et al. Opportunistic localization of skin lesions on vulnerable areas. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:483-488.

9. Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

1. Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2, pt 1):161-182.

2. Wang AR, O’Brien M, Ross R, et al. Epidermotropic metastasis from vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: a rare cutaneous manifestation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1088-1091.

3. Mailhot J, O’Donnell P, Han R, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva mimicking primary varicella-zoster virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e63-e64.

4. Savoia P, Fava P, Deboli T, et al. Zosteriform cutaneous metastases: a literature meta-analysis and a clinical report of three melanoma cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1355-1363.

5. Niiyama S, Satoh K, Kaneko S, et al. Zosteriform skin involvement of nodal T-cell lymphoma: a review of the published work of cutaneous malignancies mimicking herpes zoster. J Dermatol. 2007;34:68-73.

6. Zalaudek I, Leinweber B, Richtig E, et al. Cutaneous zosteriform melanoma metastases arising after herpes zoster infection: a case report and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:635-639.

7. LeSueur BW, Abraham LJ, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Zosteriform skin metastases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:126-128.

8. Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Brunetti G, et al. Opportunistic localization of skin lesions on vulnerable areas. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:483-488.

9. Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

A 48-year-old woman presented with a dermatosis on the left thigh. She had a history of hypertension, obesity, and a stage IIIC vulvar carcinoma treated with radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy. Two months after surgery she was hospitalized because of a left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and an abscess involving the site of the lymphadenectomy. One month later she presented with a painful dermatosis on the left thigh. Physical examination revealed multiple round-shaped, purple, erythematous tumors with a smooth surface on the upper third of the left thigh extending to the lower abdomen. The tumors measured 0.5 cm in diameter and were grouped to form an indurated plaque on an erythematous base; some tumors were arranged as satellite lesions in the periphery. The dermatosis had a distinct zosteriform appearance.

Orbera intragastric balloon approved for weight loss in obese adults

Another endoscopically delivered intragastric balloon indicated as a weight loss aid in obese adults has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

The Orbera intragastric balloon has been approved as a treatment for weight loss, in obese adults, with a body mass index between 30 and 40 kg/m2, the manufacturer, Apollo Endosurgery, announced on Aug. 6. It is intended for obese adults who are considering invasive surgery or for whom invasive surgery is not appropriate, when diet and exercise or pharmaceutical interventions have not worked, the statement said.

During a 20- to 30-minute procedure, the deflated Orbera silicone balloon is placed in the stomach via an endoscopic procedure under a mild sedative, where it is then filled with saline until it is about the size of a grapefruit, according to the company. The patient usually can go home on the same day; the balloon is deflated and removed 6 months later. The company will provide patients with an individualized weight-loss program for patients for 1 year, starting from the time of balloon placement.

The approval of this device follows the approval of the ReShape intragastric balloon for obese adults, for up to 6 months, announced by the FDA on July 28. ReShape was the first such device to be approved in the United States.

The results of the pivotal U.S. 12-month multicenter trial of the Orbera balloon in more than 250 obese adults with a BMI of 30-40 kg/m2 were reported at the Digestive Disease Week meeting in May, by Dr. Barham K. Abu Dayyeh of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. For more than 2 years, patients were randomized to a 12-month behavioral modification program, with or without endoscopic placement of the balloon, which was removed at 6 months. Eighteen patients withdrew before treatment; 215 patients were evaluable at 6 months, 206 at 9 months, and 191 at 12 months.

At 6 months, the mean percent total body weight loss was about 10% in the balloon group, vs. 4% in the control group, a significant difference (P less than .001). In addition, the total body weight loss was significantly higher in the balloon group at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and the mean percent of excess weight loss at 6 months was better in the balloon group than in the control group (about 40% vs. 13%; P less than .001), he said at the meeting. The majority of excess weight loss achieved at 6 months was also maintained at 12 months.

Serious adverse events were reported in 7% of controls and almost 10% of the balloon group, which included eight early removals for intolerance, one gastric outlet obstruction, one laryngospasm during placement, one case of severe abdominal cramping, and one case of severe dehydration. Early device removals occurred in 22% of patients, 15 for symptoms and 13 at subject request, Dr. Abu Dayyeh said. There were no deaths during the study.

The Orbera balloon has been available in more than 80 countries, according to the manufacturer.

More information is available on the FDA website.

Another endoscopically delivered intragastric balloon indicated as a weight loss aid in obese adults has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

The Orbera intragastric balloon has been approved as a treatment for weight loss, in obese adults, with a body mass index between 30 and 40 kg/m2, the manufacturer, Apollo Endosurgery, announced on Aug. 6. It is intended for obese adults who are considering invasive surgery or for whom invasive surgery is not appropriate, when diet and exercise or pharmaceutical interventions have not worked, the statement said.

During a 20- to 30-minute procedure, the deflated Orbera silicone balloon is placed in the stomach via an endoscopic procedure under a mild sedative, where it is then filled with saline until it is about the size of a grapefruit, according to the company. The patient usually can go home on the same day; the balloon is deflated and removed 6 months later. The company will provide patients with an individualized weight-loss program for patients for 1 year, starting from the time of balloon placement.

The approval of this device follows the approval of the ReShape intragastric balloon for obese adults, for up to 6 months, announced by the FDA on July 28. ReShape was the first such device to be approved in the United States.

The results of the pivotal U.S. 12-month multicenter trial of the Orbera balloon in more than 250 obese adults with a BMI of 30-40 kg/m2 were reported at the Digestive Disease Week meeting in May, by Dr. Barham K. Abu Dayyeh of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. For more than 2 years, patients were randomized to a 12-month behavioral modification program, with or without endoscopic placement of the balloon, which was removed at 6 months. Eighteen patients withdrew before treatment; 215 patients were evaluable at 6 months, 206 at 9 months, and 191 at 12 months.

At 6 months, the mean percent total body weight loss was about 10% in the balloon group, vs. 4% in the control group, a significant difference (P less than .001). In addition, the total body weight loss was significantly higher in the balloon group at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and the mean percent of excess weight loss at 6 months was better in the balloon group than in the control group (about 40% vs. 13%; P less than .001), he said at the meeting. The majority of excess weight loss achieved at 6 months was also maintained at 12 months.

Serious adverse events were reported in 7% of controls and almost 10% of the balloon group, which included eight early removals for intolerance, one gastric outlet obstruction, one laryngospasm during placement, one case of severe abdominal cramping, and one case of severe dehydration. Early device removals occurred in 22% of patients, 15 for symptoms and 13 at subject request, Dr. Abu Dayyeh said. There were no deaths during the study.

The Orbera balloon has been available in more than 80 countries, according to the manufacturer.

More information is available on the FDA website.

Another endoscopically delivered intragastric balloon indicated as a weight loss aid in obese adults has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

The Orbera intragastric balloon has been approved as a treatment for weight loss, in obese adults, with a body mass index between 30 and 40 kg/m2, the manufacturer, Apollo Endosurgery, announced on Aug. 6. It is intended for obese adults who are considering invasive surgery or for whom invasive surgery is not appropriate, when diet and exercise or pharmaceutical interventions have not worked, the statement said.

During a 20- to 30-minute procedure, the deflated Orbera silicone balloon is placed in the stomach via an endoscopic procedure under a mild sedative, where it is then filled with saline until it is about the size of a grapefruit, according to the company. The patient usually can go home on the same day; the balloon is deflated and removed 6 months later. The company will provide patients with an individualized weight-loss program for patients for 1 year, starting from the time of balloon placement.

The approval of this device follows the approval of the ReShape intragastric balloon for obese adults, for up to 6 months, announced by the FDA on July 28. ReShape was the first such device to be approved in the United States.

The results of the pivotal U.S. 12-month multicenter trial of the Orbera balloon in more than 250 obese adults with a BMI of 30-40 kg/m2 were reported at the Digestive Disease Week meeting in May, by Dr. Barham K. Abu Dayyeh of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. For more than 2 years, patients were randomized to a 12-month behavioral modification program, with or without endoscopic placement of the balloon, which was removed at 6 months. Eighteen patients withdrew before treatment; 215 patients were evaluable at 6 months, 206 at 9 months, and 191 at 12 months.

At 6 months, the mean percent total body weight loss was about 10% in the balloon group, vs. 4% in the control group, a significant difference (P less than .001). In addition, the total body weight loss was significantly higher in the balloon group at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and the mean percent of excess weight loss at 6 months was better in the balloon group than in the control group (about 40% vs. 13%; P less than .001), he said at the meeting. The majority of excess weight loss achieved at 6 months was also maintained at 12 months.

Serious adverse events were reported in 7% of controls and almost 10% of the balloon group, which included eight early removals for intolerance, one gastric outlet obstruction, one laryngospasm during placement, one case of severe abdominal cramping, and one case of severe dehydration. Early device removals occurred in 22% of patients, 15 for symptoms and 13 at subject request, Dr. Abu Dayyeh said. There were no deaths during the study.

The Orbera balloon has been available in more than 80 countries, according to the manufacturer.

More information is available on the FDA website.

Tumor location, radiotherapy predict neuroendocrine dysfunction after pediatric glioma

Tumor location and radiotherapy, respectively, predict the speed of onset and density of long-term neuroendocrinopathy following pediatric glioma, report Dr. Hoong-Wei Gan and coauthors at University College London Institute of Child Health.

In a longitudinal study of 166 children with a median age of 4.9 years at diagnosis, progression-free status and endocrine event–free survival (EEFS) were 47.2% and 20.8%, respectively, despite high overall survival of 81%.

Growth hormone deficiency was the most common disorder (40.3%), followed by central precocious puberty (26%), gonadotropin (20.4%), thyroid-stimulating hormone (13.3%), and adrenocorticotropic hormone (13.3%) deficiencies. Hypothalamic involvement was associated with earlier onset of dysfunction (P < .001), whereas radiotherapy predicted density (P < .001), Dr. Gan and colleagues reported.

The reduction in EEFS is “concerning given the lack of a corresponding improvement in survival,” the authors said.

“Minimizing future endocrine, visual, and cognitive morbidity remains an important therapeutic goal in managing these tumors,” they added. “Optimal treatment strategy for these benign lesions remains elusive; while the absence of longitudinal neuroendocrine morbidity data limits our understanding of their etiology and evolution.”

Read the full report at J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Jul 28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2028.

Tumor location and radiotherapy, respectively, predict the speed of onset and density of long-term neuroendocrinopathy following pediatric glioma, report Dr. Hoong-Wei Gan and coauthors at University College London Institute of Child Health.

In a longitudinal study of 166 children with a median age of 4.9 years at diagnosis, progression-free status and endocrine event–free survival (EEFS) were 47.2% and 20.8%, respectively, despite high overall survival of 81%.

Growth hormone deficiency was the most common disorder (40.3%), followed by central precocious puberty (26%), gonadotropin (20.4%), thyroid-stimulating hormone (13.3%), and adrenocorticotropic hormone (13.3%) deficiencies. Hypothalamic involvement was associated with earlier onset of dysfunction (P < .001), whereas radiotherapy predicted density (P < .001), Dr. Gan and colleagues reported.

The reduction in EEFS is “concerning given the lack of a corresponding improvement in survival,” the authors said.

“Minimizing future endocrine, visual, and cognitive morbidity remains an important therapeutic goal in managing these tumors,” they added. “Optimal treatment strategy for these benign lesions remains elusive; while the absence of longitudinal neuroendocrine morbidity data limits our understanding of their etiology and evolution.”

Read the full report at J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Jul 28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2028.

Tumor location and radiotherapy, respectively, predict the speed of onset and density of long-term neuroendocrinopathy following pediatric glioma, report Dr. Hoong-Wei Gan and coauthors at University College London Institute of Child Health.

In a longitudinal study of 166 children with a median age of 4.9 years at diagnosis, progression-free status and endocrine event–free survival (EEFS) were 47.2% and 20.8%, respectively, despite high overall survival of 81%.

Growth hormone deficiency was the most common disorder (40.3%), followed by central precocious puberty (26%), gonadotropin (20.4%), thyroid-stimulating hormone (13.3%), and adrenocorticotropic hormone (13.3%) deficiencies. Hypothalamic involvement was associated with earlier onset of dysfunction (P < .001), whereas radiotherapy predicted density (P < .001), Dr. Gan and colleagues reported.

The reduction in EEFS is “concerning given the lack of a corresponding improvement in survival,” the authors said.

“Minimizing future endocrine, visual, and cognitive morbidity remains an important therapeutic goal in managing these tumors,” they added. “Optimal treatment strategy for these benign lesions remains elusive; while the absence of longitudinal neuroendocrine morbidity data limits our understanding of their etiology and evolution.”

Read the full report at J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Jul 28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2028.

One-third of organ donations after circulatory death are unsuccessful

Despite the increase in donation of organs for transplant after circulatory death, many of these donations fail, according to a new study.

Dr. Joseph Scalea of the division of transplantation at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and his colleagues sought to explicate the process resulting in unsuccessful donation after circulatory death (DCD) and to explore the factors contributing to time to death in donors with successful organ donation. They conducted a retrospective study of data obtained from all organ donors at a single transplant center during January 2011-September 2014 (Ann Surg. 2015 Jul 15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001298). A total of 506 organ donation procedures were studied, 169 of which were DCD. Time of death and outcomes data was obtained in 99.4% of the cases

The reasons for DCD failure appear to be rooted in the timing of support removal and the progression to death of these potential organ donors. A study of transplantation in the United Kingdom has shown that organs are less likely to be viable for transplantation if the donor does not progress to death within the first hour of withdrawal of support (Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013;18:133-9).

“People need to be aware that when folks have agreed to donate organs of a loved one and it is going to be a [circulatory death donation], that there is roughly a one in three chance, at least, that organ donation won’t come to fruition,” Dr. Jeffrey D. Punch, a transplant specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

Protocols vary by organization, but DCD typically involves the surgical team withdrawing life support in the absence of the organ recovery team. If circulatory death occurs within the time determined by the protocol, the organs are recovered for transplantation. Studies have indicated since the general acceptance of DCD since the 1990s, these donations account for as much as a 30% increase in donation rates in the United States and abroad (Am J Transplant. 2006 Feb;6(2):281-91; N Engl J Med. 2007;357:209-13).

The University of Wisconsin’s DCD protocol involved waiting up to 30 minutes after withdrawal of support (WOS) to recover pancreas and liver and up to 2 hours to recover kidneys.

During the study period, 33.4% (n = 169/506) of the organ donations were DCD. At least one organ was successfully donated in 72.8% of cases (n = 123), whereas in 27.2% (n = 46), the patient did not progress to death in the protocol time frame to be considered for donation. Head trauma (21.9%), cerebrovascular accident (23.7%), and anoxia (47.3%) were the most common diagnosis leading to DCD; however, success of DCD donation was not associated with the diagnosis. But if withdrawal of support was initiated in the OR, successful donation was more likely (P = .006).

“Those patients who underwent WOS in the ICU successfully donated organs less frequently. This difference is hard to interpret, as there may be different techniques of withdrawal in the ICU, or a selection bias (i.e., deemed less likely to die quickly) with which patients are considered for an ICU withdrawal,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Punch, the Jeremiah and Claire Turcotte Professor of Surgery at the University of Michigan added, “It certainly makes more sense for withdrawal of support to happen in the operating room. It is more effective and they are more likely to be able to donate organs.”

The mean time from WOS to death was 28 minutes and 35 seconds for successful donations and 33 hours, 37 minutes, and 15 seconds for unsuccessful donations. In patients that successfully donated, 90.2% died less than an hour after WOS.

The investigators point out, “the ability to donate organs from a family member or loved one is often the only positive memory of an otherwise devastating experience. Unfortunately, not all donors successfully donate after attempted DCD.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Despite the increase in donation of organs for transplant after circulatory death, many of these donations fail, according to a new study.

Dr. Joseph Scalea of the division of transplantation at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and his colleagues sought to explicate the process resulting in unsuccessful donation after circulatory death (DCD) and to explore the factors contributing to time to death in donors with successful organ donation. They conducted a retrospective study of data obtained from all organ donors at a single transplant center during January 2011-September 2014 (Ann Surg. 2015 Jul 15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001298). A total of 506 organ donation procedures were studied, 169 of which were DCD. Time of death and outcomes data was obtained in 99.4% of the cases

The reasons for DCD failure appear to be rooted in the timing of support removal and the progression to death of these potential organ donors. A study of transplantation in the United Kingdom has shown that organs are less likely to be viable for transplantation if the donor does not progress to death within the first hour of withdrawal of support (Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013;18:133-9).

“People need to be aware that when folks have agreed to donate organs of a loved one and it is going to be a [circulatory death donation], that there is roughly a one in three chance, at least, that organ donation won’t come to fruition,” Dr. Jeffrey D. Punch, a transplant specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

Protocols vary by organization, but DCD typically involves the surgical team withdrawing life support in the absence of the organ recovery team. If circulatory death occurs within the time determined by the protocol, the organs are recovered for transplantation. Studies have indicated since the general acceptance of DCD since the 1990s, these donations account for as much as a 30% increase in donation rates in the United States and abroad (Am J Transplant. 2006 Feb;6(2):281-91; N Engl J Med. 2007;357:209-13).

The University of Wisconsin’s DCD protocol involved waiting up to 30 minutes after withdrawal of support (WOS) to recover pancreas and liver and up to 2 hours to recover kidneys.

During the study period, 33.4% (n = 169/506) of the organ donations were DCD. At least one organ was successfully donated in 72.8% of cases (n = 123), whereas in 27.2% (n = 46), the patient did not progress to death in the protocol time frame to be considered for donation. Head trauma (21.9%), cerebrovascular accident (23.7%), and anoxia (47.3%) were the most common diagnosis leading to DCD; however, success of DCD donation was not associated with the diagnosis. But if withdrawal of support was initiated in the OR, successful donation was more likely (P = .006).

“Those patients who underwent WOS in the ICU successfully donated organs less frequently. This difference is hard to interpret, as there may be different techniques of withdrawal in the ICU, or a selection bias (i.e., deemed less likely to die quickly) with which patients are considered for an ICU withdrawal,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Punch, the Jeremiah and Claire Turcotte Professor of Surgery at the University of Michigan added, “It certainly makes more sense for withdrawal of support to happen in the operating room. It is more effective and they are more likely to be able to donate organs.”

The mean time from WOS to death was 28 minutes and 35 seconds for successful donations and 33 hours, 37 minutes, and 15 seconds for unsuccessful donations. In patients that successfully donated, 90.2% died less than an hour after WOS.

The investigators point out, “the ability to donate organs from a family member or loved one is often the only positive memory of an otherwise devastating experience. Unfortunately, not all donors successfully donate after attempted DCD.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Despite the increase in donation of organs for transplant after circulatory death, many of these donations fail, according to a new study.

Dr. Joseph Scalea of the division of transplantation at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and his colleagues sought to explicate the process resulting in unsuccessful donation after circulatory death (DCD) and to explore the factors contributing to time to death in donors with successful organ donation. They conducted a retrospective study of data obtained from all organ donors at a single transplant center during January 2011-September 2014 (Ann Surg. 2015 Jul 15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001298). A total of 506 organ donation procedures were studied, 169 of which were DCD. Time of death and outcomes data was obtained in 99.4% of the cases