User login

Trichilemmoma

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

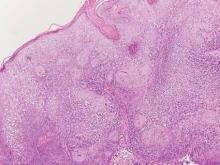

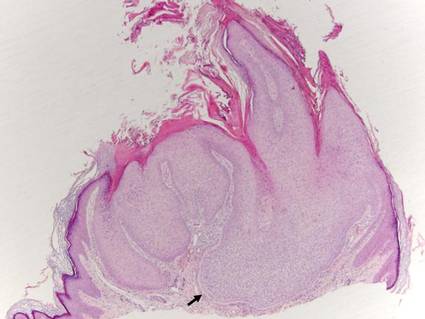

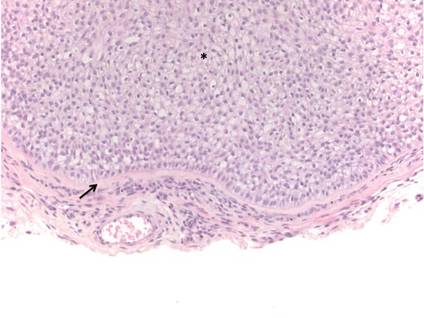

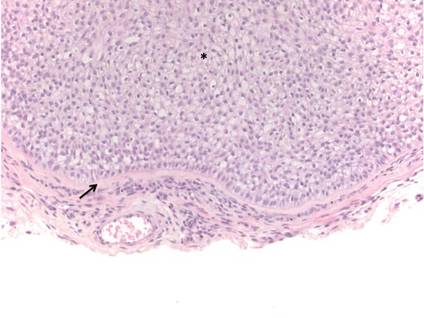

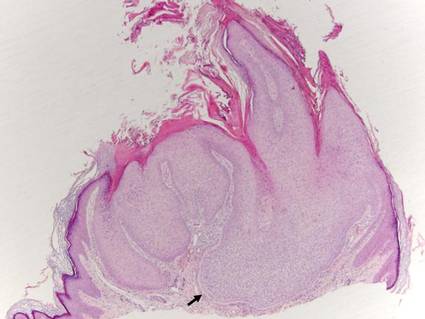

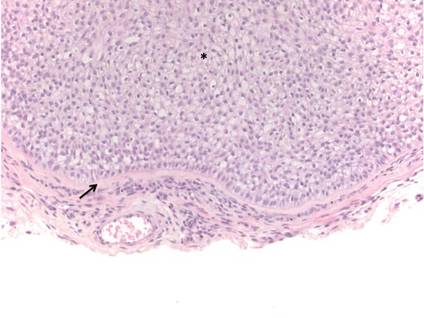

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

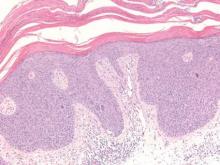

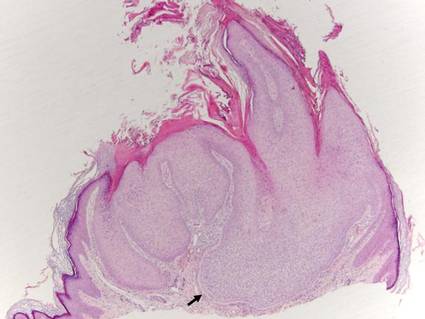

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

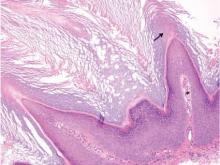

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

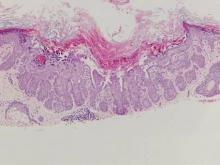

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Catching up on brain stimulation with Dr. Irving Reti

Psychiatry is a field where the treatment of our disorders remains perplexing: We’re still trying to figure out if the best way to treat psychiatric conditions is through psychotherapy, with medications, or for more resistant conditions, by stimulating activity in the brain in several different ways.

The field of brain stimulation includes electroconvulsive therapy, as well as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), direct transcranial current stimulation (tDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS), all of which are examples of treatments that are still just coming into their own.

In search of an update on brain stimulation, I met with Dr. Irving Reti, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Stimulation Program and editor of “Brain Stimulation: Methodologies and Interventions” (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). We met at a Starbucks in Baltimore, and I’ll tell you that a one-on-one conversation with an expert is a wonderful way to learn about state-of-the-art treatments, the only downside being that Starbucks does not offer CME credit.

Dr. Reti, who went to medical school at the University of Sydney and speaks with a charming Australian accent, trained in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, and then did a neuroscience fellowship.

“I’d just finished residency training, and I was giving ECT to rats. We were looking at the expression of immediate-early genes. At the same time, I started doing consults in the mood disorders clinic.”

In 2006, Dr. Reti took over as director of ECT at Hopkins, and that same year, Dr. Jimmy Potash got funding to study TMS. Dr. Potash has since moved to the University of Iowa, and Dr. Reti took over TMS administration at Hopkins. Dr. Reti was flattered to be approached by Wiley to edit “Brain Stimulation,” and he talked about how he was pleased with the final edition of the book.

“I ended up getting the top people to write the chapters, people like Sarah Lisanby, Michael Nitsche, John Rothwell, and Mark George. These are the leaders in the field of brain stimulation.”

I asked Dr. Reti to walk me through what was happening in each brain stimulation area.

“In ECT,” he said, “we know a lot more now about how both the settings and the anesthesia regimen affect the outcomes. We didn’t know this when I trained in the ’90s.” Dr. Reti estimated that he’s administered ECT to close to 2,000 patients.

TMS is done less often at Hopkins; he estimated that 10-20 patients receive the treatment, and each patient comes 30-40 times, with each session lasting 40 minutes.

“It’s better than medicine but not as effective as ECT. We’re seeing an efficacy rate around 50%-60%,” and he noted that some patients have trouble tolerating the procedure as the magnetic stimulation can be uncomfortable. “The TMS coil stimulates the scalp nerves and muscles immediately under the coil, which causes discomfort.” He noted that some patients need to premedicate with over-the-counter pain medicines.

“We’re also finding that low-frequency stimulation on the right can be helpful for anxiety,” Dr. Reti said.

He talked about treating patients with psychotherapy along with TMS. The brain changes are thought to increase the brain’s plasticity and perhaps make psychotherapy more effective.

“It’s being studied in drug treatment. You can show someone with an addiction stimuli to trigger cravings, and doing this with TMS may block the response,” he said.

He talked for a while about direct transcranial brain stimulation, which I was not very familiar with. Because it is being used to improve focus-playing video games, the equipment is not being marketed as a psychiatric treatment and doesn’t fall under the domain of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Kids are using it to improve their concentration and performance with video games; all you need is a 9-volt battery and some electrodes that are attached to the scalp. The kits cost about $250, but you can burn your scalp,” he said.

Dr. Reti referred me to an article in the New Yorker on tDCS, “Electrified: Adventures in transcranial direct-current stimulation” by Elif Batuman. He noted that there are studies in progress to look at therapeutic uses for tDCS, including one at Johns Hopkins where neuropsychologist David Schretlen is looking at improving cognition in schizophrenia. Dr. Reti is interested in seeing if tDCS might be helpful in decreasing self-injurious behaviors in autistic children, as ECT has been effective in severe cases. He noted that while ECT and TMS stimulate neurons in the brain to fire, tDCS changes the stimulation threshold without directly causing the neurons to discharge.

Finally, we talked a little about deep brain stimulation. Thin electrodes directly target nodes in brain circuits that can modulate the activity of those circuits. He noted that deep brain stimulation was being used at Johns Hopkins to treat Parkinson’s disease, and other centers have looked at its use for severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“We know that the response habituates; now they are trying on-demand DBS,” Dr. Reti noted.

So, although I got no continuing medical education credits, I did get to try a new Starbucks drink while having a very stimulating discussion on the latest convulsive and nonconvulsive psychiatric brain research.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Psychiatry is a field where the treatment of our disorders remains perplexing: We’re still trying to figure out if the best way to treat psychiatric conditions is through psychotherapy, with medications, or for more resistant conditions, by stimulating activity in the brain in several different ways.

The field of brain stimulation includes electroconvulsive therapy, as well as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), direct transcranial current stimulation (tDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS), all of which are examples of treatments that are still just coming into their own.

In search of an update on brain stimulation, I met with Dr. Irving Reti, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Stimulation Program and editor of “Brain Stimulation: Methodologies and Interventions” (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). We met at a Starbucks in Baltimore, and I’ll tell you that a one-on-one conversation with an expert is a wonderful way to learn about state-of-the-art treatments, the only downside being that Starbucks does not offer CME credit.

Dr. Reti, who went to medical school at the University of Sydney and speaks with a charming Australian accent, trained in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, and then did a neuroscience fellowship.

“I’d just finished residency training, and I was giving ECT to rats. We were looking at the expression of immediate-early genes. At the same time, I started doing consults in the mood disorders clinic.”

In 2006, Dr. Reti took over as director of ECT at Hopkins, and that same year, Dr. Jimmy Potash got funding to study TMS. Dr. Potash has since moved to the University of Iowa, and Dr. Reti took over TMS administration at Hopkins. Dr. Reti was flattered to be approached by Wiley to edit “Brain Stimulation,” and he talked about how he was pleased with the final edition of the book.

“I ended up getting the top people to write the chapters, people like Sarah Lisanby, Michael Nitsche, John Rothwell, and Mark George. These are the leaders in the field of brain stimulation.”

I asked Dr. Reti to walk me through what was happening in each brain stimulation area.

“In ECT,” he said, “we know a lot more now about how both the settings and the anesthesia regimen affect the outcomes. We didn’t know this when I trained in the ’90s.” Dr. Reti estimated that he’s administered ECT to close to 2,000 patients.

TMS is done less often at Hopkins; he estimated that 10-20 patients receive the treatment, and each patient comes 30-40 times, with each session lasting 40 minutes.

“It’s better than medicine but not as effective as ECT. We’re seeing an efficacy rate around 50%-60%,” and he noted that some patients have trouble tolerating the procedure as the magnetic stimulation can be uncomfortable. “The TMS coil stimulates the scalp nerves and muscles immediately under the coil, which causes discomfort.” He noted that some patients need to premedicate with over-the-counter pain medicines.

“We’re also finding that low-frequency stimulation on the right can be helpful for anxiety,” Dr. Reti said.

He talked about treating patients with psychotherapy along with TMS. The brain changes are thought to increase the brain’s plasticity and perhaps make psychotherapy more effective.

“It’s being studied in drug treatment. You can show someone with an addiction stimuli to trigger cravings, and doing this with TMS may block the response,” he said.

He talked for a while about direct transcranial brain stimulation, which I was not very familiar with. Because it is being used to improve focus-playing video games, the equipment is not being marketed as a psychiatric treatment and doesn’t fall under the domain of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Kids are using it to improve their concentration and performance with video games; all you need is a 9-volt battery and some electrodes that are attached to the scalp. The kits cost about $250, but you can burn your scalp,” he said.

Dr. Reti referred me to an article in the New Yorker on tDCS, “Electrified: Adventures in transcranial direct-current stimulation” by Elif Batuman. He noted that there are studies in progress to look at therapeutic uses for tDCS, including one at Johns Hopkins where neuropsychologist David Schretlen is looking at improving cognition in schizophrenia. Dr. Reti is interested in seeing if tDCS might be helpful in decreasing self-injurious behaviors in autistic children, as ECT has been effective in severe cases. He noted that while ECT and TMS stimulate neurons in the brain to fire, tDCS changes the stimulation threshold without directly causing the neurons to discharge.

Finally, we talked a little about deep brain stimulation. Thin electrodes directly target nodes in brain circuits that can modulate the activity of those circuits. He noted that deep brain stimulation was being used at Johns Hopkins to treat Parkinson’s disease, and other centers have looked at its use for severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“We know that the response habituates; now they are trying on-demand DBS,” Dr. Reti noted.

So, although I got no continuing medical education credits, I did get to try a new Starbucks drink while having a very stimulating discussion on the latest convulsive and nonconvulsive psychiatric brain research.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Psychiatry is a field where the treatment of our disorders remains perplexing: We’re still trying to figure out if the best way to treat psychiatric conditions is through psychotherapy, with medications, or for more resistant conditions, by stimulating activity in the brain in several different ways.

The field of brain stimulation includes electroconvulsive therapy, as well as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), direct transcranial current stimulation (tDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS), all of which are examples of treatments that are still just coming into their own.

In search of an update on brain stimulation, I met with Dr. Irving Reti, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Stimulation Program and editor of “Brain Stimulation: Methodologies and Interventions” (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). We met at a Starbucks in Baltimore, and I’ll tell you that a one-on-one conversation with an expert is a wonderful way to learn about state-of-the-art treatments, the only downside being that Starbucks does not offer CME credit.

Dr. Reti, who went to medical school at the University of Sydney and speaks with a charming Australian accent, trained in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, and then did a neuroscience fellowship.

“I’d just finished residency training, and I was giving ECT to rats. We were looking at the expression of immediate-early genes. At the same time, I started doing consults in the mood disorders clinic.”

In 2006, Dr. Reti took over as director of ECT at Hopkins, and that same year, Dr. Jimmy Potash got funding to study TMS. Dr. Potash has since moved to the University of Iowa, and Dr. Reti took over TMS administration at Hopkins. Dr. Reti was flattered to be approached by Wiley to edit “Brain Stimulation,” and he talked about how he was pleased with the final edition of the book.

“I ended up getting the top people to write the chapters, people like Sarah Lisanby, Michael Nitsche, John Rothwell, and Mark George. These are the leaders in the field of brain stimulation.”

I asked Dr. Reti to walk me through what was happening in each brain stimulation area.

“In ECT,” he said, “we know a lot more now about how both the settings and the anesthesia regimen affect the outcomes. We didn’t know this when I trained in the ’90s.” Dr. Reti estimated that he’s administered ECT to close to 2,000 patients.

TMS is done less often at Hopkins; he estimated that 10-20 patients receive the treatment, and each patient comes 30-40 times, with each session lasting 40 minutes.

“It’s better than medicine but not as effective as ECT. We’re seeing an efficacy rate around 50%-60%,” and he noted that some patients have trouble tolerating the procedure as the magnetic stimulation can be uncomfortable. “The TMS coil stimulates the scalp nerves and muscles immediately under the coil, which causes discomfort.” He noted that some patients need to premedicate with over-the-counter pain medicines.

“We’re also finding that low-frequency stimulation on the right can be helpful for anxiety,” Dr. Reti said.

He talked about treating patients with psychotherapy along with TMS. The brain changes are thought to increase the brain’s plasticity and perhaps make psychotherapy more effective.

“It’s being studied in drug treatment. You can show someone with an addiction stimuli to trigger cravings, and doing this with TMS may block the response,” he said.

He talked for a while about direct transcranial brain stimulation, which I was not very familiar with. Because it is being used to improve focus-playing video games, the equipment is not being marketed as a psychiatric treatment and doesn’t fall under the domain of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Kids are using it to improve their concentration and performance with video games; all you need is a 9-volt battery and some electrodes that are attached to the scalp. The kits cost about $250, but you can burn your scalp,” he said.

Dr. Reti referred me to an article in the New Yorker on tDCS, “Electrified: Adventures in transcranial direct-current stimulation” by Elif Batuman. He noted that there are studies in progress to look at therapeutic uses for tDCS, including one at Johns Hopkins where neuropsychologist David Schretlen is looking at improving cognition in schizophrenia. Dr. Reti is interested in seeing if tDCS might be helpful in decreasing self-injurious behaviors in autistic children, as ECT has been effective in severe cases. He noted that while ECT and TMS stimulate neurons in the brain to fire, tDCS changes the stimulation threshold without directly causing the neurons to discharge.

Finally, we talked a little about deep brain stimulation. Thin electrodes directly target nodes in brain circuits that can modulate the activity of those circuits. He noted that deep brain stimulation was being used at Johns Hopkins to treat Parkinson’s disease, and other centers have looked at its use for severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“We know that the response habituates; now they are trying on-demand DBS,” Dr. Reti noted.

So, although I got no continuing medical education credits, I did get to try a new Starbucks drink while having a very stimulating discussion on the latest convulsive and nonconvulsive psychiatric brain research.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Top 10 treatments for vitiligo

PARK CITY, UTAH – At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Dr. Sancy A. Leachman offered a top 10 list of new agents and technologies for the treatment of vitiligo.

No. 10: Ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) phototherapy

Dr. Harvey Lui at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver is leading a phase II trial to evaluate the potential for UVA1 to induce repigmentation within vitiligo patches and to assess the side effect profile of the treatment. “I think it might work,” said Dr. Leachman, professor and chair of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland.

No. 9: Ginkgo biloba

The use of ginko biloba 40-60 mg 2-3 times per day, 10 minutes before a meal, was mentioned in a Cochrane Review of vitiligo treatments published on Feb. 24, 2015. “I think I’m going to give this a try in people who have failed other treatments and see if I can get some response,” Dr. Leachman said.

No. 8: Red light

Dr. Lui is leading a randomized phase II trial of low-intensity and high-intensity red light versus no treatment for vitiligo patches. Treatments will be given twice weekly for 10 weeks, with follow-up assessments at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post treatment.

No. 7: Micrografting

A novel suction blister device known as the CelluTome epidermal harvesting system uses heat and slight vacuum pressure to harvest healthy epidermal skin tissue without damaging the donor site. Dr. Leachman characterized the technology as “semiautomating the process of suction graft transplantation.”

No. 6: The ReCell device

Manufactured by Avita Medical, this investigational autologous cell harvesting device is used after CO2 abrasion and enables clinicians to create regenerative epithelial suspension with a small sample of the patient’s skin. A phase IV trial in the Netherlands is underway to assess the efficacy and safety of autologous epidermal cell suspension grafting with the ReCell device after CO2 laser abrasion, compared with CO2 laser abrasion alone and no treatment, in patients with piebaldism and stable vitiligo.

No. 5: Topical Photocil

In a pilot study sponsored by Applied Biology, researchers are enrolling patients with vitiligo to assess the safety and efficacy of Photocil. The primary outcome measure is the Vitiligo Area Severity Index (VASI). “When this cream is activated by sunlight, it degrades into narrow-band and UVB light, so you can put a topical cream on that will administer narrow-band UVB only in that spot,” said Dr. Leachman, who is also director of OHSU’s Knight Melanoma Research Program. “That’s amazing to me.”

No. 4: Afamelanotide

This is an analogue of a melanocyte-stimulating hormone. A randomized study conducted at two academic medical centers found that the combination of afamelanotide implant and narrow-band UVB phototherapy resulted in statistically superior and faster repigmentation, compared with narrow-band UVB monotherapy (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Jan;151(1):42-50).

No. 3: Abatacept (Orencia)

This is a soluble fusion protein consisting of human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), which prevents T-cell activation. A phase I trial is underway at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to determine if weekly self-injections of the agent lead to clinical improvements of vitiligo lesions. The primary outcome measure is change in repigmentation with abatacept therapy based on the VASI score.

No. 2. Simvastatin

The notion of its use is based on STAT1 inhibition reducing interferon-gamma–dependent activation of CD8-positive T cells, according to Dr. Leachman. The concept has been successful in a mouse model, and a study in humans was recently completed by Dr. John Harris at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. “What we have is the ability to apply an existing drug (Simvastatin) to the process and see if it works,” she said. “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could give a statin and improve vitiligo?”

No 1: Tofacitinib

This is a Janus kinase inhibitor commonly used for rheumatoid arthritis. According to Dr. Leachman, Janus kinase inhibition prevents STAT activation, “which prevents [interferon]-gamma production, which reduces activation of CD8-positive T cells via CXCL10 binding to CXCR3,” she said. A case report demonstrating its efficacy in a 53-year-old patient was recently published in JAMA Dermatology by Dr. Brett A. King and Dr. Brittany Craiglow, dermatologists at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. “I’m hopeful that this [agent] will be made into a topical cream because these drugs do have substantial side effects,” Dr. Leachman said.

Dr. Leachman disclosed that she is a member of the medical and scientific advisory board for Myriad Genetics Laboratory. She has also participated in an advisory board meeting for Castle Biosciences and has participated in the DecisionDx registry.

PARK CITY, UTAH – At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Dr. Sancy A. Leachman offered a top 10 list of new agents and technologies for the treatment of vitiligo.

No. 10: Ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) phototherapy

Dr. Harvey Lui at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver is leading a phase II trial to evaluate the potential for UVA1 to induce repigmentation within vitiligo patches and to assess the side effect profile of the treatment. “I think it might work,” said Dr. Leachman, professor and chair of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland.

No. 9: Ginkgo biloba

The use of ginko biloba 40-60 mg 2-3 times per day, 10 minutes before a meal, was mentioned in a Cochrane Review of vitiligo treatments published on Feb. 24, 2015. “I think I’m going to give this a try in people who have failed other treatments and see if I can get some response,” Dr. Leachman said.

No. 8: Red light

Dr. Lui is leading a randomized phase II trial of low-intensity and high-intensity red light versus no treatment for vitiligo patches. Treatments will be given twice weekly for 10 weeks, with follow-up assessments at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post treatment.

No. 7: Micrografting

A novel suction blister device known as the CelluTome epidermal harvesting system uses heat and slight vacuum pressure to harvest healthy epidermal skin tissue without damaging the donor site. Dr. Leachman characterized the technology as “semiautomating the process of suction graft transplantation.”

No. 6: The ReCell device

Manufactured by Avita Medical, this investigational autologous cell harvesting device is used after CO2 abrasion and enables clinicians to create regenerative epithelial suspension with a small sample of the patient’s skin. A phase IV trial in the Netherlands is underway to assess the efficacy and safety of autologous epidermal cell suspension grafting with the ReCell device after CO2 laser abrasion, compared with CO2 laser abrasion alone and no treatment, in patients with piebaldism and stable vitiligo.

No. 5: Topical Photocil

In a pilot study sponsored by Applied Biology, researchers are enrolling patients with vitiligo to assess the safety and efficacy of Photocil. The primary outcome measure is the Vitiligo Area Severity Index (VASI). “When this cream is activated by sunlight, it degrades into narrow-band and UVB light, so you can put a topical cream on that will administer narrow-band UVB only in that spot,” said Dr. Leachman, who is also director of OHSU’s Knight Melanoma Research Program. “That’s amazing to me.”

No. 4: Afamelanotide

This is an analogue of a melanocyte-stimulating hormone. A randomized study conducted at two academic medical centers found that the combination of afamelanotide implant and narrow-band UVB phototherapy resulted in statistically superior and faster repigmentation, compared with narrow-band UVB monotherapy (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Jan;151(1):42-50).

No. 3: Abatacept (Orencia)

This is a soluble fusion protein consisting of human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), which prevents T-cell activation. A phase I trial is underway at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to determine if weekly self-injections of the agent lead to clinical improvements of vitiligo lesions. The primary outcome measure is change in repigmentation with abatacept therapy based on the VASI score.

No. 2. Simvastatin

The notion of its use is based on STAT1 inhibition reducing interferon-gamma–dependent activation of CD8-positive T cells, according to Dr. Leachman. The concept has been successful in a mouse model, and a study in humans was recently completed by Dr. John Harris at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. “What we have is the ability to apply an existing drug (Simvastatin) to the process and see if it works,” she said. “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could give a statin and improve vitiligo?”

No 1: Tofacitinib

This is a Janus kinase inhibitor commonly used for rheumatoid arthritis. According to Dr. Leachman, Janus kinase inhibition prevents STAT activation, “which prevents [interferon]-gamma production, which reduces activation of CD8-positive T cells via CXCL10 binding to CXCR3,” she said. A case report demonstrating its efficacy in a 53-year-old patient was recently published in JAMA Dermatology by Dr. Brett A. King and Dr. Brittany Craiglow, dermatologists at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. “I’m hopeful that this [agent] will be made into a topical cream because these drugs do have substantial side effects,” Dr. Leachman said.

Dr. Leachman disclosed that she is a member of the medical and scientific advisory board for Myriad Genetics Laboratory. She has also participated in an advisory board meeting for Castle Biosciences and has participated in the DecisionDx registry.

PARK CITY, UTAH – At the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association, Dr. Sancy A. Leachman offered a top 10 list of new agents and technologies for the treatment of vitiligo.

No. 10: Ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) phototherapy

Dr. Harvey Lui at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver is leading a phase II trial to evaluate the potential for UVA1 to induce repigmentation within vitiligo patches and to assess the side effect profile of the treatment. “I think it might work,” said Dr. Leachman, professor and chair of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland.

No. 9: Ginkgo biloba

The use of ginko biloba 40-60 mg 2-3 times per day, 10 minutes before a meal, was mentioned in a Cochrane Review of vitiligo treatments published on Feb. 24, 2015. “I think I’m going to give this a try in people who have failed other treatments and see if I can get some response,” Dr. Leachman said.

No. 8: Red light

Dr. Lui is leading a randomized phase II trial of low-intensity and high-intensity red light versus no treatment for vitiligo patches. Treatments will be given twice weekly for 10 weeks, with follow-up assessments at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post treatment.

No. 7: Micrografting

A novel suction blister device known as the CelluTome epidermal harvesting system uses heat and slight vacuum pressure to harvest healthy epidermal skin tissue without damaging the donor site. Dr. Leachman characterized the technology as “semiautomating the process of suction graft transplantation.”

No. 6: The ReCell device

Manufactured by Avita Medical, this investigational autologous cell harvesting device is used after CO2 abrasion and enables clinicians to create regenerative epithelial suspension with a small sample of the patient’s skin. A phase IV trial in the Netherlands is underway to assess the efficacy and safety of autologous epidermal cell suspension grafting with the ReCell device after CO2 laser abrasion, compared with CO2 laser abrasion alone and no treatment, in patients with piebaldism and stable vitiligo.

No. 5: Topical Photocil

In a pilot study sponsored by Applied Biology, researchers are enrolling patients with vitiligo to assess the safety and efficacy of Photocil. The primary outcome measure is the Vitiligo Area Severity Index (VASI). “When this cream is activated by sunlight, it degrades into narrow-band and UVB light, so you can put a topical cream on that will administer narrow-band UVB only in that spot,” said Dr. Leachman, who is also director of OHSU’s Knight Melanoma Research Program. “That’s amazing to me.”

No. 4: Afamelanotide

This is an analogue of a melanocyte-stimulating hormone. A randomized study conducted at two academic medical centers found that the combination of afamelanotide implant and narrow-band UVB phototherapy resulted in statistically superior and faster repigmentation, compared with narrow-band UVB monotherapy (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Jan;151(1):42-50).

No. 3: Abatacept (Orencia)

This is a soluble fusion protein consisting of human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), which prevents T-cell activation. A phase I trial is underway at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to determine if weekly self-injections of the agent lead to clinical improvements of vitiligo lesions. The primary outcome measure is change in repigmentation with abatacept therapy based on the VASI score.

No. 2. Simvastatin

The notion of its use is based on STAT1 inhibition reducing interferon-gamma–dependent activation of CD8-positive T cells, according to Dr. Leachman. The concept has been successful in a mouse model, and a study in humans was recently completed by Dr. John Harris at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester. “What we have is the ability to apply an existing drug (Simvastatin) to the process and see if it works,” she said. “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could give a statin and improve vitiligo?”

No 1: Tofacitinib

This is a Janus kinase inhibitor commonly used for rheumatoid arthritis. According to Dr. Leachman, Janus kinase inhibition prevents STAT activation, “which prevents [interferon]-gamma production, which reduces activation of CD8-positive T cells via CXCL10 binding to CXCR3,” she said. A case report demonstrating its efficacy in a 53-year-old patient was recently published in JAMA Dermatology by Dr. Brett A. King and Dr. Brittany Craiglow, dermatologists at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. “I’m hopeful that this [agent] will be made into a topical cream because these drugs do have substantial side effects,” Dr. Leachman said.

Dr. Leachman disclosed that she is a member of the medical and scientific advisory board for Myriad Genetics Laboratory. She has also participated in an advisory board meeting for Castle Biosciences and has participated in the DecisionDx registry.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT PDA 2015

LISTEN NOW: Tales from the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignette (RIV) Poster Competition

Hospitalists who presented RIV posters at HM15 talk about their projects. Dr. Brian Poustinchian worked on a bedside rounding study at Midwestern University in Illinois, and Dr. Jennifer Pascoe worked on a poster about patients leaving the hospital against medical advice, focusing on a case of her own at the University of Rochester.

Hospitalists who presented RIV posters at HM15 talk about their projects. Dr. Brian Poustinchian worked on a bedside rounding study at Midwestern University in Illinois, and Dr. Jennifer Pascoe worked on a poster about patients leaving the hospital against medical advice, focusing on a case of her own at the University of Rochester.

Hospitalists who presented RIV posters at HM15 talk about their projects. Dr. Brian Poustinchian worked on a bedside rounding study at Midwestern University in Illinois, and Dr. Jennifer Pascoe worked on a poster about patients leaving the hospital against medical advice, focusing on a case of her own at the University of Rochester.

Similar Early Outcomes in nvAF Regardless of Anticoagulant Type

NEW YORK - In the early months of anticoagulant treatment, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (nvAF) have similar rates of bleeding and arterial clots with dabigatran, rivaroxaban and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) like warfarin, researchers from France report.

Large randomized trials have shown the newer non-VKA oral anticoagulants (NOAC) to have superior safety and efficacy relative to warfarin, but subsequent observational studies have yielded conflicting results.

Dr. Géric Maura from National Health Insurance (CNAMTS) in Paris and colleagues used the French National Health Insurance information system to assess the bleeding and arterial thrombotic risks of dabigatran and rivaroxaban, each compared with VKA, during the first few months of therapy in 32,807 newly treated patients with nvAF.

There was no significant difference in bleeding between VKA- and dabigatran- or rivaroxaban-treated patients on propensity-matched analysis, regardless of whether patients were treated with low or high doses of each NOAC, the researchers report in Circulation, online July 21.

The composite outcome comprising hospitalization for bleeding and death occurred with similar frequency in the different treatment groups.

Among the secondary endpoints, there were no significant differences between treatments in arterial thromboembolic events or in the composite outcome comprising stroke, systemic embolism and death.

"Although our overall results are reassuring in relation to initiation of NOAC in nvAF patients in France with no marked excess thromboembolic or bleeding risk, they also suggest that particular caution is required when initiating NOAC," the researchers conclude. "But on the basis of this study comparing NOAC to VKA, NOAC cannot be considered to be safer than VKA during the early phase of treatment. On the contrary, the clinical implications of our results are that physicians must be just as cautious when initiating NOAC as when initiating VKA, particularly in view of the absence of an antidote and objective monitoring of the extent of anticoagulation."

"Similar analyses should be extended to other NOAC such as apixaban and observational studies should now focus on NOAC head-to-head comparison in a non-inferiority design," they suggest.

The study had no commercial funding and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Maura did not respond to a request for comment.

NEW YORK - In the early months of anticoagulant treatment, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (nvAF) have similar rates of bleeding and arterial clots with dabigatran, rivaroxaban and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) like warfarin, researchers from France report.

Large randomized trials have shown the newer non-VKA oral anticoagulants (NOAC) to have superior safety and efficacy relative to warfarin, but subsequent observational studies have yielded conflicting results.

Dr. Géric Maura from National Health Insurance (CNAMTS) in Paris and colleagues used the French National Health Insurance information system to assess the bleeding and arterial thrombotic risks of dabigatran and rivaroxaban, each compared with VKA, during the first few months of therapy in 32,807 newly treated patients with nvAF.

There was no significant difference in bleeding between VKA- and dabigatran- or rivaroxaban-treated patients on propensity-matched analysis, regardless of whether patients were treated with low or high doses of each NOAC, the researchers report in Circulation, online July 21.

The composite outcome comprising hospitalization for bleeding and death occurred with similar frequency in the different treatment groups.

Among the secondary endpoints, there were no significant differences between treatments in arterial thromboembolic events or in the composite outcome comprising stroke, systemic embolism and death.

"Although our overall results are reassuring in relation to initiation of NOAC in nvAF patients in France with no marked excess thromboembolic or bleeding risk, they also suggest that particular caution is required when initiating NOAC," the researchers conclude. "But on the basis of this study comparing NOAC to VKA, NOAC cannot be considered to be safer than VKA during the early phase of treatment. On the contrary, the clinical implications of our results are that physicians must be just as cautious when initiating NOAC as when initiating VKA, particularly in view of the absence of an antidote and objective monitoring of the extent of anticoagulation."

"Similar analyses should be extended to other NOAC such as apixaban and observational studies should now focus on NOAC head-to-head comparison in a non-inferiority design," they suggest.

The study had no commercial funding and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Maura did not respond to a request for comment.

NEW YORK - In the early months of anticoagulant treatment, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (nvAF) have similar rates of bleeding and arterial clots with dabigatran, rivaroxaban and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) like warfarin, researchers from France report.

Large randomized trials have shown the newer non-VKA oral anticoagulants (NOAC) to have superior safety and efficacy relative to warfarin, but subsequent observational studies have yielded conflicting results.

Dr. Géric Maura from National Health Insurance (CNAMTS) in Paris and colleagues used the French National Health Insurance information system to assess the bleeding and arterial thrombotic risks of dabigatran and rivaroxaban, each compared with VKA, during the first few months of therapy in 32,807 newly treated patients with nvAF.

There was no significant difference in bleeding between VKA- and dabigatran- or rivaroxaban-treated patients on propensity-matched analysis, regardless of whether patients were treated with low or high doses of each NOAC, the researchers report in Circulation, online July 21.

The composite outcome comprising hospitalization for bleeding and death occurred with similar frequency in the different treatment groups.

Among the secondary endpoints, there were no significant differences between treatments in arterial thromboembolic events or in the composite outcome comprising stroke, systemic embolism and death.

"Although our overall results are reassuring in relation to initiation of NOAC in nvAF patients in France with no marked excess thromboembolic or bleeding risk, they also suggest that particular caution is required when initiating NOAC," the researchers conclude. "But on the basis of this study comparing NOAC to VKA, NOAC cannot be considered to be safer than VKA during the early phase of treatment. On the contrary, the clinical implications of our results are that physicians must be just as cautious when initiating NOAC as when initiating VKA, particularly in view of the absence of an antidote and objective monitoring of the extent of anticoagulation."

"Similar analyses should be extended to other NOAC such as apixaban and observational studies should now focus on NOAC head-to-head comparison in a non-inferiority design," they suggest.

The study had no commercial funding and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Maura did not respond to a request for comment.

New prognostic model for follicular lymphoma

Photo courtesy of NIH

A newly developed prognostic model can identify follicular lymphoma (FL) patients at the highest risk for treatment failure, according to researchers.

To create this model, called m7-FLIPI, the team combined the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and the mutation status of 7 genes—EZH2, ARID1A, MEF2B, EP300, FOXO1, CREBBP, and CARD11.

The researchers said this is the first prognostic model for FL that accounts for both clinical factors and genetic mutations.

They described the creation and testing of the model in The Lancet Oncology.

“We set out to determine, at the time of diagnosis, which patients’ disease will have sustained responses after treatment and whether new genetic data could help inform which patients are at risk for developing progressive lymphoma so clinicians would be able to offer these high-risk patients more effective therapies,” said Randy Gascoyne, MD, of the British Columbia Cancer Agency in Vancouver, Canada.

He and his colleagues created the m7-FLIPI by conducting a retrospective analysis of genetic mutations and clinical risk factors in 2 cohorts of patients with symptomatic, advanced stage, or bulky FL grade 1, 2, or 3A.

The patients had a biopsy specimen collected 12 months or less before they began first-line treatment with an immunochemotherapy regimen containing rituximab.

Training cohort

The training cohort consisted of 151 FL patients who received R-CHOP. The median follow-up for these patients was 7.7 years.

When the researchers applied the m7-FLIPI to this cohort, they found 28% of patients (43/151) were defined as high-risk, with a 5-year failure-free survival (FFS) rate of 38.29%.

And 72% of patients (108/151) were defined as low-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 77.21%. The hazard ratio was 4.14 (P<0.0001).

The positive predictive value for 5-year FFS was 64%, and the negative predictive value was 78%. The m7-FLIPI outperformed a prognostic model of only gene mutations and the FLIPI-2.

Validation cohort

The validation cohort consisted of 107 patients who received R-CVP. The median follow-up for these patients was 6.7 years.

When the researchers applied the m7-FLIPI to this cohort, they found that 22% of patients (24/107) were defined as high-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 25%.

And 78% of patients (83/107) were defined as low-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 68.24%. The hazard ratio was 3.58 (P<0.0001).

The positive predictive value for 5-year FFS was 72%, and the negative predictive value was 68%. The m7-FLIPI outperformed the FLIPI alone and the FLIPI combined with ECOG performance status.

Overall survival

Although the m7-FLIPI was designed specifically for FFS, the researchers also tested its prognostic utility for overall survival (OS).

In the training cohort, high-risk disease according to the m7-FLIPI was associated with a 5-year OS of 65.25%, compared to 89.98% for low-risk disease (P=0.00031).

In the validation cohort, 5-year OS was 41.67% for patients with high-risk disease and 84.01% for patients with low-risk disease (P<0.0001). In both cohorts, the m7-FLIPI outperformed the FLIPI alone.

Based on these results, the researchers believe the m7-FLIPI could be utilized in a clinical setting to test all new FL patients at diagnosis and identify patients who harbor the most aggressive disease.

“The m7-FLIPI could be extremely significant for the medical community,” Dr Gascoyne said, “changing the story for high-risk patients who are currently destined to not respond well to standard treatment.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIH

A newly developed prognostic model can identify follicular lymphoma (FL) patients at the highest risk for treatment failure, according to researchers.

To create this model, called m7-FLIPI, the team combined the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and the mutation status of 7 genes—EZH2, ARID1A, MEF2B, EP300, FOXO1, CREBBP, and CARD11.

The researchers said this is the first prognostic model for FL that accounts for both clinical factors and genetic mutations.

They described the creation and testing of the model in The Lancet Oncology.

“We set out to determine, at the time of diagnosis, which patients’ disease will have sustained responses after treatment and whether new genetic data could help inform which patients are at risk for developing progressive lymphoma so clinicians would be able to offer these high-risk patients more effective therapies,” said Randy Gascoyne, MD, of the British Columbia Cancer Agency in Vancouver, Canada.

He and his colleagues created the m7-FLIPI by conducting a retrospective analysis of genetic mutations and clinical risk factors in 2 cohorts of patients with symptomatic, advanced stage, or bulky FL grade 1, 2, or 3A.

The patients had a biopsy specimen collected 12 months or less before they began first-line treatment with an immunochemotherapy regimen containing rituximab.

Training cohort

The training cohort consisted of 151 FL patients who received R-CHOP. The median follow-up for these patients was 7.7 years.

When the researchers applied the m7-FLIPI to this cohort, they found 28% of patients (43/151) were defined as high-risk, with a 5-year failure-free survival (FFS) rate of 38.29%.

And 72% of patients (108/151) were defined as low-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 77.21%. The hazard ratio was 4.14 (P<0.0001).

The positive predictive value for 5-year FFS was 64%, and the negative predictive value was 78%. The m7-FLIPI outperformed a prognostic model of only gene mutations and the FLIPI-2.

Validation cohort

The validation cohort consisted of 107 patients who received R-CVP. The median follow-up for these patients was 6.7 years.

When the researchers applied the m7-FLIPI to this cohort, they found that 22% of patients (24/107) were defined as high-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 25%.

And 78% of patients (83/107) were defined as low-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 68.24%. The hazard ratio was 3.58 (P<0.0001).

The positive predictive value for 5-year FFS was 72%, and the negative predictive value was 68%. The m7-FLIPI outperformed the FLIPI alone and the FLIPI combined with ECOG performance status.

Overall survival

Although the m7-FLIPI was designed specifically for FFS, the researchers also tested its prognostic utility for overall survival (OS).

In the training cohort, high-risk disease according to the m7-FLIPI was associated with a 5-year OS of 65.25%, compared to 89.98% for low-risk disease (P=0.00031).

In the validation cohort, 5-year OS was 41.67% for patients with high-risk disease and 84.01% for patients with low-risk disease (P<0.0001). In both cohorts, the m7-FLIPI outperformed the FLIPI alone.

Based on these results, the researchers believe the m7-FLIPI could be utilized in a clinical setting to test all new FL patients at diagnosis and identify patients who harbor the most aggressive disease.

“The m7-FLIPI could be extremely significant for the medical community,” Dr Gascoyne said, “changing the story for high-risk patients who are currently destined to not respond well to standard treatment.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIH

A newly developed prognostic model can identify follicular lymphoma (FL) patients at the highest risk for treatment failure, according to researchers.

To create this model, called m7-FLIPI, the team combined the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and the mutation status of 7 genes—EZH2, ARID1A, MEF2B, EP300, FOXO1, CREBBP, and CARD11.

The researchers said this is the first prognostic model for FL that accounts for both clinical factors and genetic mutations.

They described the creation and testing of the model in The Lancet Oncology.

“We set out to determine, at the time of diagnosis, which patients’ disease will have sustained responses after treatment and whether new genetic data could help inform which patients are at risk for developing progressive lymphoma so clinicians would be able to offer these high-risk patients more effective therapies,” said Randy Gascoyne, MD, of the British Columbia Cancer Agency in Vancouver, Canada.

He and his colleagues created the m7-FLIPI by conducting a retrospective analysis of genetic mutations and clinical risk factors in 2 cohorts of patients with symptomatic, advanced stage, or bulky FL grade 1, 2, or 3A.

The patients had a biopsy specimen collected 12 months or less before they began first-line treatment with an immunochemotherapy regimen containing rituximab.

Training cohort

The training cohort consisted of 151 FL patients who received R-CHOP. The median follow-up for these patients was 7.7 years.

When the researchers applied the m7-FLIPI to this cohort, they found 28% of patients (43/151) were defined as high-risk, with a 5-year failure-free survival (FFS) rate of 38.29%.

And 72% of patients (108/151) were defined as low-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 77.21%. The hazard ratio was 4.14 (P<0.0001).

The positive predictive value for 5-year FFS was 64%, and the negative predictive value was 78%. The m7-FLIPI outperformed a prognostic model of only gene mutations and the FLIPI-2.

Validation cohort

The validation cohort consisted of 107 patients who received R-CVP. The median follow-up for these patients was 6.7 years.

When the researchers applied the m7-FLIPI to this cohort, they found that 22% of patients (24/107) were defined as high-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 25%.

And 78% of patients (83/107) were defined as low-risk, with a 5-year FFS of 68.24%. The hazard ratio was 3.58 (P<0.0001).

The positive predictive value for 5-year FFS was 72%, and the negative predictive value was 68%. The m7-FLIPI outperformed the FLIPI alone and the FLIPI combined with ECOG performance status.

Overall survival

Although the m7-FLIPI was designed specifically for FFS, the researchers also tested its prognostic utility for overall survival (OS).

In the training cohort, high-risk disease according to the m7-FLIPI was associated with a 5-year OS of 65.25%, compared to 89.98% for low-risk disease (P=0.00031).

In the validation cohort, 5-year OS was 41.67% for patients with high-risk disease and 84.01% for patients with low-risk disease (P<0.0001). In both cohorts, the m7-FLIPI outperformed the FLIPI alone.

Based on these results, the researchers believe the m7-FLIPI could be utilized in a clinical setting to test all new FL patients at diagnosis and identify patients who harbor the most aggressive disease.

“The m7-FLIPI could be extremely significant for the medical community,” Dr Gascoyne said, “changing the story for high-risk patients who are currently destined to not respond well to standard treatment.” ![]()

Rivaroxaban monitoring kit launched in Europe

Instrumentation Laboratory, a company that develops in vitro diagnostic instruments, has announced the commercialization of the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in Europe.

This testing kit consists of the HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa Assay, Rivaroxaban Calibrators, and Rivaroxaban Controls, which can be used with ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing Systems to monitor patients taking the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The assay, calibrators, and controls are now CE IVD Marked under the European IVD Directive 98/79/EC.

This allows Instrumentation Laboratory to distribute the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in the European Union and other international territories.

Although monitoring is generally not required for patients on rivaroxaban, there are cases in which measuring rivaroxaban may be necessary.

This includes patients who present with bleeding, require reversal of anticoagulation, experience deteriorating renal function, or must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure and have taken rivaroxaban within 24 hours or longer if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL min-1.

Liquid Anti-Xa Assay

The HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa kit is a one-stage chromogenic assay based on a synthetic chromogenic substrate and factor Xa inactivation. Rivaroxaban levels in patient plasma are measured automatically on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System when this assay is calibrated with the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators.

The Anti-Xa Assay kit consists of:

- Factor Xa reagent: 5 x 2.5 mL vial of a liquid preparation containing purified bovine factor Xa (approximately 5.5 nkat/mL), Tris-Buffer, EDTA, dextran sulfate, sodium chloride, and bovine serum albumin.

- Chromogenic substrate: 5 x 3 mL vial of liquid chromogenic substrate S-2732 (approximately 1.2 mg/mL) and bulking agent.

Rivaroxaban Calibrators

The HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators are intended for the calibration of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized calibrators prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban are used by the instrument to automatically prepare a calibration curve.

The Rivaroxaban Calibrator kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 1: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing buffers and stabilizers.

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 2: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, buffers, and stabilizers.

Rivaroxaban Controls

HemosIL Rivaroxaban Controls are intended for the quality control of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized controls are prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban. Use of both controls is recommended for a complete quality control program.

The Rivaroxaban Controls kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Low Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

- Rivaroxaban High Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

Instrumentation Laboratory, a company that develops in vitro diagnostic instruments, has announced the commercialization of the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in Europe.

This testing kit consists of the HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa Assay, Rivaroxaban Calibrators, and Rivaroxaban Controls, which can be used with ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing Systems to monitor patients taking the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The assay, calibrators, and controls are now CE IVD Marked under the European IVD Directive 98/79/EC.

This allows Instrumentation Laboratory to distribute the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in the European Union and other international territories.

Although monitoring is generally not required for patients on rivaroxaban, there are cases in which measuring rivaroxaban may be necessary.

This includes patients who present with bleeding, require reversal of anticoagulation, experience deteriorating renal function, or must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure and have taken rivaroxaban within 24 hours or longer if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL min-1.

Liquid Anti-Xa Assay

The HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa kit is a one-stage chromogenic assay based on a synthetic chromogenic substrate and factor Xa inactivation. Rivaroxaban levels in patient plasma are measured automatically on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System when this assay is calibrated with the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators.

The Anti-Xa Assay kit consists of:

- Factor Xa reagent: 5 x 2.5 mL vial of a liquid preparation containing purified bovine factor Xa (approximately 5.5 nkat/mL), Tris-Buffer, EDTA, dextran sulfate, sodium chloride, and bovine serum albumin.

- Chromogenic substrate: 5 x 3 mL vial of liquid chromogenic substrate S-2732 (approximately 1.2 mg/mL) and bulking agent.

Rivaroxaban Calibrators

The HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators are intended for the calibration of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized calibrators prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban are used by the instrument to automatically prepare a calibration curve.

The Rivaroxaban Calibrator kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 1: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing buffers and stabilizers.

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 2: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, buffers, and stabilizers.

Rivaroxaban Controls

HemosIL Rivaroxaban Controls are intended for the quality control of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized controls are prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban. Use of both controls is recommended for a complete quality control program.

The Rivaroxaban Controls kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Low Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

- Rivaroxaban High Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

Instrumentation Laboratory, a company that develops in vitro diagnostic instruments, has announced the commercialization of the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in Europe.

This testing kit consists of the HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa Assay, Rivaroxaban Calibrators, and Rivaroxaban Controls, which can be used with ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing Systems to monitor patients taking the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The assay, calibrators, and controls are now CE IVD Marked under the European IVD Directive 98/79/EC.

This allows Instrumentation Laboratory to distribute the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in the European Union and other international territories.

Although monitoring is generally not required for patients on rivaroxaban, there are cases in which measuring rivaroxaban may be necessary.

This includes patients who present with bleeding, require reversal of anticoagulation, experience deteriorating renal function, or must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure and have taken rivaroxaban within 24 hours or longer if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL min-1.

Liquid Anti-Xa Assay

The HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa kit is a one-stage chromogenic assay based on a synthetic chromogenic substrate and factor Xa inactivation. Rivaroxaban levels in patient plasma are measured automatically on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System when this assay is calibrated with the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators.

The Anti-Xa Assay kit consists of:

- Factor Xa reagent: 5 x 2.5 mL vial of a liquid preparation containing purified bovine factor Xa (approximately 5.5 nkat/mL), Tris-Buffer, EDTA, dextran sulfate, sodium chloride, and bovine serum albumin.

- Chromogenic substrate: 5 x 3 mL vial of liquid chromogenic substrate S-2732 (approximately 1.2 mg/mL) and bulking agent.

Rivaroxaban Calibrators

The HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators are intended for the calibration of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized calibrators prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban are used by the instrument to automatically prepare a calibration curve.

The Rivaroxaban Calibrator kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 1: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing buffers and stabilizers.

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 2: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, buffers, and stabilizers.

Rivaroxaban Controls

HemosIL Rivaroxaban Controls are intended for the quality control of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized controls are prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban. Use of both controls is recommended for a complete quality control program.

The Rivaroxaban Controls kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Low Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

- Rivaroxaban High Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

Platform simplifies data analysis, team says

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers say they have developed a user-friendly platform for analyzing transcriptomic and epigenomic sequencing data.

This platform, BioWardrobe, was designed to help biomedical researchers analyze data that might answer questions about diseases and basic biology.

“Although biologists can perform experiments and obtain the data, they often lack the programming expertise required to perform computational data analysis,” said Artem Barski, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

“BioWardrobe aims to empower researchers by bridging this gap between data and knowledge.”

Dr Barski and Andrey Kartashov, also of the University of Cincinnati, described BioWardrobe in Genome Biology.

The pair said the recent proliferation of sequencing-based methods for analysis of gene expression, chromatin structure, and protein-DNA interactions has widened our horizons, but the volume of data obtained from sequencing requires computational data analysis.

Unfortunately, the bioinformatics and programming expertise required for this analysis may be absent in biomedical laboratories. And this can result in data inaccessibility or delays in applying modern sequencing-based technologies to pressing questions in basic and health-related research.

Dr Barski and Kartashov believe BioWardrobe can solve those problems by providing a “biologist-friendly” web interface.

BioWardrobe users can download data from institutional facilities or public databases, map reads, and visualize results on a genome browser. The platform also allows for differential gene expression and binding analysis, and it can create average tag-density profiles and heatmaps.

Dr Barski and Kartashov plan to continue improving BioWardrobe and continue using the platform in their own research on epigenetic regulation in the immune system, as well as in collaborative projects with other investigators. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers say they have developed a user-friendly platform for analyzing transcriptomic and epigenomic sequencing data.

This platform, BioWardrobe, was designed to help biomedical researchers analyze data that might answer questions about diseases and basic biology.

“Although biologists can perform experiments and obtain the data, they often lack the programming expertise required to perform computational data analysis,” said Artem Barski, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

“BioWardrobe aims to empower researchers by bridging this gap between data and knowledge.”

Dr Barski and Andrey Kartashov, also of the University of Cincinnati, described BioWardrobe in Genome Biology.