User login

Tool that lets patients report AEs proves reliable

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Results of a multicenter study indicate that a tool cancer patients can use to report adverse events (AEs) is as accurate as other, established patient-reported and clinical measures.

The tool is the National Cancer Institute’s Patient Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE).

Study investigators were able to validate 119 of 124 PRO-CTCAE questions against 2 established measurement tools.

The 5 questions that were not validated could not be evaluated due to underrepresentation in the study population.

This research was published in JAMA Oncology.

“In most cancer clinical trials, information on side effects is collected by providers who have limited time with their patients, and current patient questionnaires are limited in scope and depth,” said study author Amylou Dueck, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“PRO-CTCAE is a library of items for patients to directly report on the level of each of their symptoms, to enhance the reporting of side effects in cancer clinical trials, which is normally based on information from providers. The study itself is unprecedented, as more than 100 distinct questions about symptomatic adverse events were validated simultaneously.”

To assess the PRO-CTCAE, Dr Dueck and her colleagues recruited 975 cancer patients from 9 clinical practices across the US, including 7 cancer centers.

The patients had a range of cancers and were undergoing outpatient chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. The investigators said these participants reflected the geographic, ethnic, racial, and economic diversity in cancer clinical trials.

The patients were asked to fill out the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire before appointments. The investigators then compared patient reports to clinician-reported Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30).

A majority of patients completed items on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire at their first visit (96.4%, 940/975) and second visit (90.6%, 852/940).

Most patients (99.8%, 938/940) reported having at least 1 symptomatic AE, with 81.7% (768/940) reporting at least 1 AE as frequent, severe, and/or interfering “quite a bit” with daily activities.

To gauge the accuracy of the PRO-CTCAE, the investigators assessed construct validity, test-retest reliability, and responsiveness of PRO-CTCAE items.

Construct validity

The investigators explained that construct validity reflects the association between a new measurement tool and an established measure.

Construct validity is often investigated through convergent validity, which determines whether the new tool moves in the same direction as an established instrument, and known-groups validity, which determines whether the tool can distinguish between groups of patients who are thought to be distinct.

When the investigators considered all QLQ-C30 functioning/global scales, they found that all 124 items on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire were associated in the expected direction with 1 or more scales. One hundred and fourteen of the PRO-CTCAE items demonstrated a meaningful correlation (Pearson r≥0.1), and 111 of them were statistically significant (P<0.05 for all).

Scores for 94 of 124 PRO-CTCAE items were higher among patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 to 4 (17.1% of patients) than among patients with a score of 0 to 1. The difference was significant for 58 of the items (P<0.05 for all).

Test-retest reliability and responsiveness

The investigators said they estimated test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), based on a 1-way analysis of variance model with an ICC of 0.7 or greater interpreted as high.

Test-retest reliability was 0.7 or greater for 36 of 49 prespecified PRO-CTCAE items. The median ICC was 0.76 [range, 0.53-0.96).

The investigators assessed the responsiveness of PRO-CTCAE items by comparing any change from the first visit to the second visit in 27 items that were selected a priori.

Correlations between PRO-CTCAE item changes and corresponding QLQ-C30 scale changes were significant for all 27 items (P≤0.006 for all).

“This is a landmark study demonstrating that meaningful information about adverse events can be elicited from patients themselves, which is a major step for advancing the patient-centeredness of clinical trials,” said study author Ethan Basch, MD, of the Lineberger Cancer Center of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Results of a multicenter study indicate that a tool cancer patients can use to report adverse events (AEs) is as accurate as other, established patient-reported and clinical measures.

The tool is the National Cancer Institute’s Patient Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE).

Study investigators were able to validate 119 of 124 PRO-CTCAE questions against 2 established measurement tools.

The 5 questions that were not validated could not be evaluated due to underrepresentation in the study population.

This research was published in JAMA Oncology.

“In most cancer clinical trials, information on side effects is collected by providers who have limited time with their patients, and current patient questionnaires are limited in scope and depth,” said study author Amylou Dueck, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“PRO-CTCAE is a library of items for patients to directly report on the level of each of their symptoms, to enhance the reporting of side effects in cancer clinical trials, which is normally based on information from providers. The study itself is unprecedented, as more than 100 distinct questions about symptomatic adverse events were validated simultaneously.”

To assess the PRO-CTCAE, Dr Dueck and her colleagues recruited 975 cancer patients from 9 clinical practices across the US, including 7 cancer centers.

The patients had a range of cancers and were undergoing outpatient chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. The investigators said these participants reflected the geographic, ethnic, racial, and economic diversity in cancer clinical trials.

The patients were asked to fill out the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire before appointments. The investigators then compared patient reports to clinician-reported Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30).

A majority of patients completed items on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire at their first visit (96.4%, 940/975) and second visit (90.6%, 852/940).

Most patients (99.8%, 938/940) reported having at least 1 symptomatic AE, with 81.7% (768/940) reporting at least 1 AE as frequent, severe, and/or interfering “quite a bit” with daily activities.

To gauge the accuracy of the PRO-CTCAE, the investigators assessed construct validity, test-retest reliability, and responsiveness of PRO-CTCAE items.

Construct validity

The investigators explained that construct validity reflects the association between a new measurement tool and an established measure.

Construct validity is often investigated through convergent validity, which determines whether the new tool moves in the same direction as an established instrument, and known-groups validity, which determines whether the tool can distinguish between groups of patients who are thought to be distinct.

When the investigators considered all QLQ-C30 functioning/global scales, they found that all 124 items on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire were associated in the expected direction with 1 or more scales. One hundred and fourteen of the PRO-CTCAE items demonstrated a meaningful correlation (Pearson r≥0.1), and 111 of them were statistically significant (P<0.05 for all).

Scores for 94 of 124 PRO-CTCAE items were higher among patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 to 4 (17.1% of patients) than among patients with a score of 0 to 1. The difference was significant for 58 of the items (P<0.05 for all).

Test-retest reliability and responsiveness

The investigators said they estimated test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), based on a 1-way analysis of variance model with an ICC of 0.7 or greater interpreted as high.

Test-retest reliability was 0.7 or greater for 36 of 49 prespecified PRO-CTCAE items. The median ICC was 0.76 [range, 0.53-0.96).

The investigators assessed the responsiveness of PRO-CTCAE items by comparing any change from the first visit to the second visit in 27 items that were selected a priori.

Correlations between PRO-CTCAE item changes and corresponding QLQ-C30 scale changes were significant for all 27 items (P≤0.006 for all).

“This is a landmark study demonstrating that meaningful information about adverse events can be elicited from patients themselves, which is a major step for advancing the patient-centeredness of clinical trials,” said study author Ethan Basch, MD, of the Lineberger Cancer Center of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Results of a multicenter study indicate that a tool cancer patients can use to report adverse events (AEs) is as accurate as other, established patient-reported and clinical measures.

The tool is the National Cancer Institute’s Patient Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE).

Study investigators were able to validate 119 of 124 PRO-CTCAE questions against 2 established measurement tools.

The 5 questions that were not validated could not be evaluated due to underrepresentation in the study population.

This research was published in JAMA Oncology.

“In most cancer clinical trials, information on side effects is collected by providers who have limited time with their patients, and current patient questionnaires are limited in scope and depth,” said study author Amylou Dueck, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“PRO-CTCAE is a library of items for patients to directly report on the level of each of their symptoms, to enhance the reporting of side effects in cancer clinical trials, which is normally based on information from providers. The study itself is unprecedented, as more than 100 distinct questions about symptomatic adverse events were validated simultaneously.”

To assess the PRO-CTCAE, Dr Dueck and her colleagues recruited 975 cancer patients from 9 clinical practices across the US, including 7 cancer centers.

The patients had a range of cancers and were undergoing outpatient chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. The investigators said these participants reflected the geographic, ethnic, racial, and economic diversity in cancer clinical trials.

The patients were asked to fill out the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire before appointments. The investigators then compared patient reports to clinician-reported Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30).

A majority of patients completed items on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire at their first visit (96.4%, 940/975) and second visit (90.6%, 852/940).

Most patients (99.8%, 938/940) reported having at least 1 symptomatic AE, with 81.7% (768/940) reporting at least 1 AE as frequent, severe, and/or interfering “quite a bit” with daily activities.

To gauge the accuracy of the PRO-CTCAE, the investigators assessed construct validity, test-retest reliability, and responsiveness of PRO-CTCAE items.

Construct validity

The investigators explained that construct validity reflects the association between a new measurement tool and an established measure.

Construct validity is often investigated through convergent validity, which determines whether the new tool moves in the same direction as an established instrument, and known-groups validity, which determines whether the tool can distinguish between groups of patients who are thought to be distinct.

When the investigators considered all QLQ-C30 functioning/global scales, they found that all 124 items on the PRO-CTCAE questionnaire were associated in the expected direction with 1 or more scales. One hundred and fourteen of the PRO-CTCAE items demonstrated a meaningful correlation (Pearson r≥0.1), and 111 of them were statistically significant (P<0.05 for all).

Scores for 94 of 124 PRO-CTCAE items were higher among patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 to 4 (17.1% of patients) than among patients with a score of 0 to 1. The difference was significant for 58 of the items (P<0.05 for all).

Test-retest reliability and responsiveness

The investigators said they estimated test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), based on a 1-way analysis of variance model with an ICC of 0.7 or greater interpreted as high.

Test-retest reliability was 0.7 or greater for 36 of 49 prespecified PRO-CTCAE items. The median ICC was 0.76 [range, 0.53-0.96).

The investigators assessed the responsiveness of PRO-CTCAE items by comparing any change from the first visit to the second visit in 27 items that were selected a priori.

Correlations between PRO-CTCAE item changes and corresponding QLQ-C30 scale changes were significant for all 27 items (P≤0.006 for all).

“This is a landmark study demonstrating that meaningful information about adverse events can be elicited from patients themselves, which is a major step for advancing the patient-centeredness of clinical trials,” said study author Ethan Basch, MD, of the Lineberger Cancer Center of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. ![]()

National Acute Medicine Programme

In 2009, Irish hospitals were experiencing ongoing and increasing overcrowding of emergency departments (EDs). This overcrowding and subsequent assessment delays are both associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates.[1, 2, 3, 4] The prevailing culture in many larger hospitals was to prioritize subspecialty care at the expense of the assessment and management of patients with undifferentiated acute medical presentations with nonspecific symptoms. The National Acute Medicine Programme (NAMP) was set up in 2010 by the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland (RCPI) and the Health Service Executive (HSE) to address this unsatisfactory management of acutely ill medical patients.

The objectives of the NAMP are categorized under 3 quality improvement principles: (1) Quality: to improve quality of care and patient safety by ensuring patients are seen by a nurse within 20 minutes and a senior doctor within 1 hour of arrival. (2) Access: to improve access by ensuring that the patient journey from presentation to decision to admit or discharge does not exceed 6 hours and to eliminate extended waiting periods on gurneys for medical patients. (3) Cost: to reduce cost and increase value by achieving bed savings through reduced overnight admissions and shortened lengths of stay.

The program was implemented by a small national team, which included hospital and public health physicians, nurses, a health and social care professional (HSCP), a general practitioner (GP), and a program manager. RCPI also set up a National Advisory Group of Consultant Physicians, comprised of representative medical consultants from all over the country, and key links were established with each acute hospital. The team aimed to develop a standardized model of care for all acutely ill medical patients and ensure its full implementation nationally.

METHODS

A literature review was undertaken to develop the standardized model of care in agreement with stakeholders and in consultation with patient groups.[5] The model of care required the establishment of acute medical assessment units (AMAUs), whose main function was to assess to discharge rather than admit to assess patients.[6, 7] At that time, only 8 of the 33 acute Irish hospitals that admitted medical patients had an AMAU. However, their function and operation varied greatly. In the remaining hospitals, all medical patients went to the ED, and from there were either admitted or discharged. Delays in access to senior clinicians, diagnostics, and allied health professionals such as, Occupational Therapists, Physiotherapists and Speech and Language Therapists often resulted in delays in assessment and treatment that could lead to overnight admissions.

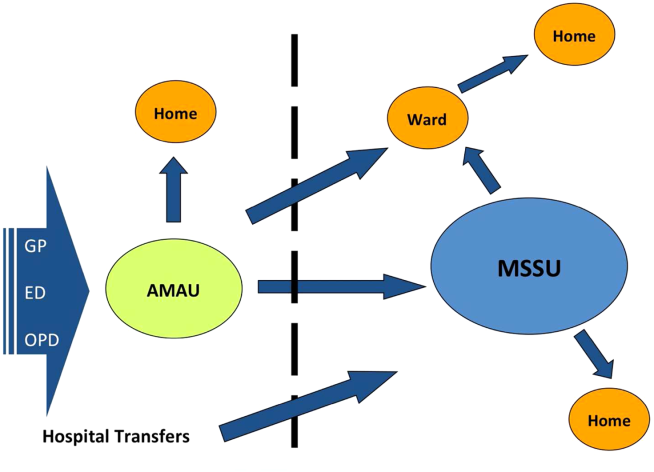

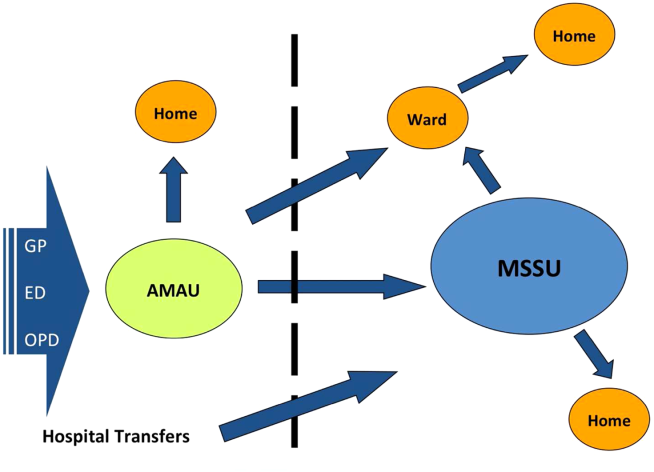

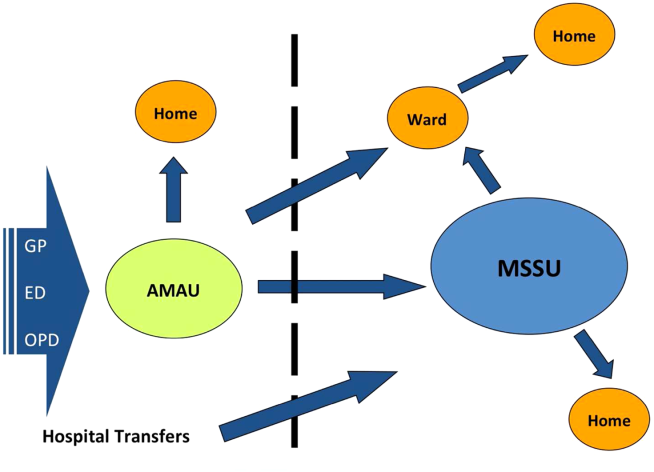

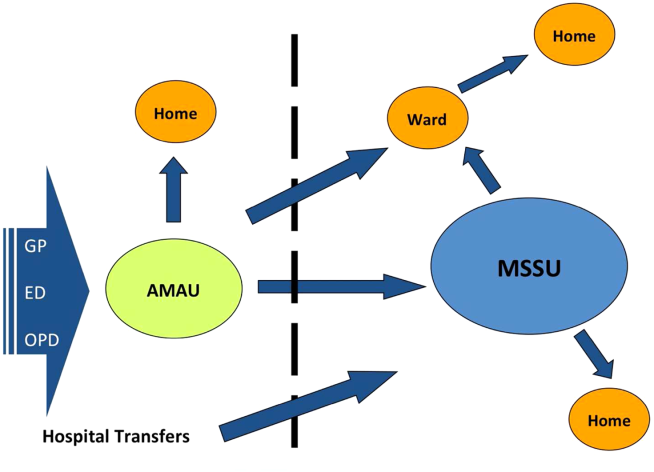

In the new model, all acute medical patients, except those requiring invasive monitoring, critical care, or special services such as oncology and dialysis, are referred to the AMAU by another doctor (ie. a GP, outpatient department, or ED physician), as shown in Figure 1. A senior physician in the AMAU then reviews the patient and decides to admit or discharge. This doctor can either be a dedicated physician with an interest in acute general medicine, or a specialist consultant rostered to work in the unit on a regular basis. Some patients are discharged the same day thanks to prompt review and treatment. Of those requiring overnight admission, some are streamed directly to specialist pathways (eg. coronary care unit). The remaining patients are admitted to the medical short‐stay unit (MSSU) under the care of an acute physician. Patients in the MSSU are then either discharged within 48 hours or go on to be transferred to a specialist ward.

The model of care was therefore divided into 4 care pathways. National Health Service (NHS) admission data for 2008 to 2009 were used to calculate the proportion of patients who flowed through each pathway. The NHS has a wealth of experience in the development and use of AMAUs, having started implementing these units in the early 2000s. Therefore, the NHS estimates calculated above were used to set the national benchmarks for the NAMP. The four pathways are:

1. Ambulatory Care Pathway

Patients receive safe and effective treatment and are discharged on the same day. The NAMP benchmark was that at least 25% of AMAU admissions should follow this pathway of care.

2. Medical Short‐Stay Care Pathway

This pathway was developed for those patients who require inpatient care but are not expected to stay longer than 1 or 2 nights. The program benchmark was that 31% of patients should be discharged within 48 hours.

3. Routine Specialist Inpatient Care Pathway

Approximately 33% of medical admissions are expected to stay more than 2 days and less than 14 days in the hospital and have a straightforward discharge after their acute episode of care. These patients are admitted either directly to specialist medical wards from AMAU or via the MSSU within 2 days of arrival. Care is formally handed over from the AMAU team to the appropriate consultant physician upon transfer.

4. Appropriate Care and Discharge of Complex Patients Care Pathway

Frail older patients have complex care needs that continue following discharge, and their discharge requirements must be identified early during the acute care episode. The NAMP benchmark was that no more than 11% of medical admissions would fall into this pathway and require a length of stay (LoS) exceeding 14 days.

The flow model was used to build system capacity by modeling and predicting the expected demand on each AMAU to assist in forward planning The number of assessment spaces and ward beds required for each hospital were calculated by analyzing respective admission data for 2009 and applying target lengths of stay for medical patients to the flow model. The program team carried out this analysis for each of the 32 hospitals. The model of care also identified a number of practice changes under each pathway that would be required to achieve process changes and the resulting efficiency gains. Table 1 summarizes these.

|

| Ambulatory care pathway |

| Establishment of adequate assessment area |

| National early warning score within 20 minutes |

| Access to senior decision maker within 1 hour |

| Access to rapid diagnostics and HSCP assessment |

| Development of clinical criteria for transfer between ED and AMAU |

| Liaison with discharge planner |

| Clear pathways to specialist wards and community support |

| Close liaison with GP to ensure integrated care |

| Patient experience time in AMAU to be 6 hours or less |

| Medical short‐stay care pathway |

| Establishment of adequate short‐stay unit |

| Access to senior decision maker within 12 hours of transfer from AMAU |

| Twice daily consultant ward rounds |

| Access to prioritized diagnostics and HSCP assessment |

| Integrated discharge planning |

| Routine specialist inpatient care pathway |

| Daily consultant ward rounds |

| Weekend nurse/HSCP‐facilitated discharges |

| Active discharge planning with planned dates of discharge for every patient |

| Liaison with caregivers and community supports |

| Development of clinical criteria to support bidirectional flow to community hospitals within hospital groups |

| Appropriate care and discharge of complex patients care pathway |

| Early assessment and identification of complex patients |

| Streaming to care of the elderly services where appropriate |

| Proactive multidisciplinary discharge planning and liaison with funding agencies for referral to community placements and supports |

Hospitals were also categorized into 4 divisions or models as determined by the complexity of patients they admit. Model 1 hospitals are community units with subacute inpatient beds that can care for patients with rehabilitation, respite, or palliative care needs. Model 2 hospitals are small hospitals that provide inpatient and outpatient care for low‐risk, differentiated medical patients or refer on to associated higher complexity facilities. The majority of hospitals in the country are model 3 general hospitals, admitting 50% of all medical patients. Last, model 4 hospitals are the 8 regional tertiary referral centers in Ireland. A considerable volume of their patient workload remains inpatient admissions for routine specialist inpatient care.

Measuring success in the program's quality and access objectives required the development of a bespoke information technology (IT) system that is not yet operational, and therefore these objectives could not be audited.

A number of outcome measures or key performance indicators (KPIs) were developed to assess performance under each care pathway relative to the cost objectives of the NAMP as shown in Table 2. The available hospital inpatient enquiry (HIPE) data were analyzed by the program team to establish baseline performance metrics for each hospital. Initially, these data were only available to the NAMP 1 year in arrears. However, the NAMP worked with the hospitals and the HIPE system to improve the completeness and timeliness of the HIPE reporting, so that by the third quarter of 2011 monthly data were available. Audit cycles occurred on a continuous monthly basis, with feedback provided to each hospital and follow‐up of results conducted at a local level. This allowed for analysis of performance at a national, hospital group, and individual hospital level. Of note, it was only possible to analyze readmission rates to the same facility in the absence of a national unique patient identifier, and therefore readmission rates observed were of limited use as a quality measure.

| Care Pathway | Metric | National Target | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Ambulatory care pathway | % of patients with LoS=0 | 25% | 11.5% | 12.9% | 18.8% | 23.2% |

| Medical short‐stay pathway | % of patients with LoS 12 days | 31% | 25.4% | 25.9% | 25.6% | 23.8% |

| Routine specialist inpatient pathway | % of patients with LoS>2 days | 44% | 63.1% | 61.2% | 55.6% | 53.1% |

| Complex care pathway | % of patients with LoS>14 days | 11% | 13.1% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 10.8% |

| % BDU of patients with LoS>30 days | 33% | 36.9% | 36.0% | 35.1% | 34.4% | |

| Routine and complex care pathway | Average LoS for those staying >2 days | 610 days | 12.9 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| Summary metric | Overall average LoS | 5.8 days | 8.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 6.9 |

| No. of medical discharges | 202,567 | 206,250 | 235,167 | 253,083 | ||

RESULTS

The NAMP model of care was officially launched in December 2010.[6] Thirty‐two out of the 33 Irish hospitals that admit acute medical patients had adopted the model of care by the end of 2013. The program team performed an initial diagnostic meeting at each hospital to explain the program, discuss their individual baseline metrics, and collaboratively develop a hospital‐specific implementation plan. A local implementation and unscheduled care governance team, composed of senior management members and local GPs, was established in each hospital to identify ward spaces to be developed as AMAUs, reassign nursing staff to the AMAU from the wards, and organize the recruitment of new consultants with an interest in acute general medicine. The program team performed 2 to 3 visits per year to each hospital to obtain feedback on performance and support local improvement plans using appreciative enquiry. They also organized workshops and training for physicians, nurses, managers, and data managers to improve understanding of and engagement with the program. An acute medicine nurse interest group was convened to support nurses in the transition to clinical practice with a greater focus on ambulatory care. Annual conferences were held to present and discuss annual and cumulative audit results.

Table 2 presents the national KPI results for the cost and value objectives over the 3 years of implementation. The number of medical discharges increased from 202,567 in 2010 to 253,083 in 2013. The proportion of discharges that passed through the AMAU was 29% in 2013, considerably reducing the amount of patients seen through the ED and alleviating some of the overcrowding experienced there.

The proportion of medical patients who avoided admission increased from 11.5% to 23.2% in 2013. When examining the proportion of patients discharged within 48 hours, we combined results for the ambulatory care pathway (LoS=0) and the medical short‐stay pathway (LoS=12) and found a 10% increase nationally from 36.9% to 47% in 2013. In addition, the proportion of total medical bed‐days used (BDU) for patients with LoS over 30 days also improved by 2.5%. The program achieved an overall reduction of 0.5 days in those staying over 2 days nationally, and an overall reduction in average LoS (AvLoS) for all medical inpatients of 1.6 days (from 8.5 days 6.9 days) across the 3 years.

Table 3 shows the average change in KPIs from 2010 to 2013 by hospital model group. Looking at data by hospital group allowed results to be interpreted in a national context and identify any bottlenecks in the health system.

| Care pathway | Metric | National | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Ambulatory care pathway | % of patients with LoS=0 | 11.7% | 11.5% | 12% | 11.5% |

| Medical short‐stay pathway | % of patients with LoS 12 days | 1.6% | 5% | 2.3% | 0.3% |

| Routine specialist inpatient pathway | % of patients with LoS>2 days | 10% | 6.4% | 9.8% | 11.2% |

| Complex care pathway | % of patients with LoS>14 days | 2.3% | 0.4% | 1.7% | 4.1% |

| % BDU of patients with LoS>30 days | 2.5% | 1.9% | 0.2% | 4.9% | |

| Routine and complex care pathway | Average LoS for those staying >2 days | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.4 |

| Summary metric | Overall average LoS | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 2.6 |

During the 3‐year period, the role of model 2 hospitals changed from admitting all medical patients to only admitting differentiated medical patients referred from GPs. This is reflected in their KPI results, with an increasing proportion of patients with LoS greater than 14 days and the proportion of BDU occupied by those with LoS greater than 30 days. Data from the model 2 and 3 hospitals showed a considerable increase in same‐day discharges, with a concurrent decrease in percentage of patients staying in the hospital longer than 2 days. This translated to a national reduction in AvLoS of 1 day in this hospital group. Model 2 hospitals experienced small increases in both the AvLoS for those patients staying over 2 days (0.7%) and the proportion of BDU occupied by patients staying longer than 30 days (1.9%), whereas model 3 had experienced no real change in either of these metrics (0% and 0.2%, respectively). This reflected the limited availability of long‐term care facilities and protracted funding approval process nationally during the implementation period.

Model 4 hospitals experienced improvement across all KPIs. There was an 11.2% increase in the proportion of patients discharged within 48 hours and a 1.4‐day reduction in AvLoS for patients with LoS>2 days. A notable success within this hospital category was the 4.9% reduction in percentage of BDU by patients with LoS>30 days. The AvLoS for all medical admissions in this group remained above the national target at 8.6 days but did decrease considerably by 2.6 days from its baseline.

Data on 28‐day readmission to the same facility were used as a balancing measure but were only available for the latter 2 years. We found rates of 11% and 10% for 2012 and 2013, respectively. Patient experience of these new units should be assessed, but it was not possible to measure this during the implementation period.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of the NAMP has demonstrably streamlined the care of acute medical patients in Ireland. We report the results of this national transformational change brought about by the implementation of an evidence‐based model of care. The development of a flow model for each hospital improved the patient flow from assessment to discharge. Process improvement lies at the core of all the successes achieved by the program. The practice changes highlighted in Table 1 were pivotal in streamlining and improving the care of acutely ill medical patients. The focus on early access to senior decision making, early diagnostics, and a continuous, coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care and discharge were central to the effective functioning of the AMAU and the resulting increase in avoided admissions.

Shortened lengths of stay are associated with better clinical outcomes and reduced exposure of patients to risk, and result in significant cost efficiencies accrued to the Irish health services.[2, 8] The adoption of ambulatory care and medical short‐stay pathways facilitated the 11.7% increase in avoided admissions and the reduction of 1.6 days in overall AvLoS nationally. This translates to significant cost savings for the Irish health system and likely improves clinical outcomes and reduced morbidity. We estimated these cost savings to be approximately 88.2 million by multiplying the number of bed days saved by the marginal cost of a bed day, which was quoted at 246 in 2012 by our Healthcare Pricing Office.

Thirty‐two of the 33 Irish hospitals that admit acute medical patients are now operating the program and achieving improvements in performance, as evidenced by ongoing audits. The priority given to the program by the RCPI and HSE has enabled the assignment of local implementation teams sustaining the focus on quality improvement at a local level. It also allowed for modest seed funding to be allocated for the appointment of 36 new consultants with an interest in acute general medicine. The cost of these additional consultants is offset by the considerable savings achieved through efficiency gains. An important challenge to implementation was the change in mindset required from local healthcare staff to divert patients away from the ED to the AMAU, and reassign staff and resources from other inpatient wards to the new unit. Visible clinical leadership from clinical directors, acute medicine hospital leads, senior nursing, and HSCP, together with management and local GPs, was essential in effecting this change. The program team also offered considerable support in this regard through advocacy and promotion of the program nationally. The implementation of the 4 care pathways represents a generational change in how medicine is practiced in Ireland. The development of acute medicine as a new specialty was strongly fostered by the program.

A number of disease‐specific clinical programs began operation during the implementation period and achieved reductions in AvLoS for some conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure, contributing to varying degrees (2%6%) to the bed‐days savings achieved by the NAMP. During the 3‐year period, there was a 25% increase in medical discharges. This is partly due to the changing demographics and epidemiology of chronic diseases in the Irish population. This increased demand was absorbed by the system with no increase in acute bed usage. We estimated that approximately 1000 additional acute beds would have been required if the NAMP efficiencies had not been achieved. Concurrent financial constraints compounded the stress on the public health system by limiting the available staff and resources for the new AMAUs and by reducing the number of community and nursing home beds available. This obstructed the flow of older and frailer patients out of the acute setting and impacted negatively on the performance of some hospitals.

An important limitation in auditing success in the quality and access aims of the program was the absence of IT systems within the AMAUs. These have since been specified by the NAMP but have not yet been delivered to the service areas. In addition, a bespoke user interface, which allows hospitals to manipulate and benchmark their own performance, is being developed. This will facilitate more in‐depth auditing within hospitals at the ward and consultant team level. The lack of a unique patient identifier hindered our ability to measure true 28‐day readmission rates, which is a useful quality indicator.

Despite these contextual, cultural, and structural challenges, the NAMP successfully implemented an evidence‐based model of care across the country. Through its implementation, tangible improvements to the Irish health system were observed with expected benefits to the patient. The program successfully instituted an ongoing audit cycle to promote continuous improvement and identified areas for future work to build on the successes achieved.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- ,. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient outcomes: a literature review. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2011;33(1):39–54.

- , , , et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):605–611.e6.

- , , . The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(2):106–115.

- , , , et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–10.

- Acute medical assessment units: a literature review. 2012. [Unpublished Manuscript]

- National Acute Medicine Programme Working Group. Report of the National Acute Medicine Programme 2010. Retrieved on Sep 24, 2014 from, http://www.hse.ie/eng/about/Who/clinical/natclinprog/acutemedicineprogramme/report.pdf. [Retrieved]

- Royal College of Physicians. Acute medical care. The right person, in the right setting—first time. October 2007. Retrieved on Sep 24, 2014, from, https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/acute_medical_care_final_for_web.pdf.

- . Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):213–216.

In 2009, Irish hospitals were experiencing ongoing and increasing overcrowding of emergency departments (EDs). This overcrowding and subsequent assessment delays are both associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates.[1, 2, 3, 4] The prevailing culture in many larger hospitals was to prioritize subspecialty care at the expense of the assessment and management of patients with undifferentiated acute medical presentations with nonspecific symptoms. The National Acute Medicine Programme (NAMP) was set up in 2010 by the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland (RCPI) and the Health Service Executive (HSE) to address this unsatisfactory management of acutely ill medical patients.

The objectives of the NAMP are categorized under 3 quality improvement principles: (1) Quality: to improve quality of care and patient safety by ensuring patients are seen by a nurse within 20 minutes and a senior doctor within 1 hour of arrival. (2) Access: to improve access by ensuring that the patient journey from presentation to decision to admit or discharge does not exceed 6 hours and to eliminate extended waiting periods on gurneys for medical patients. (3) Cost: to reduce cost and increase value by achieving bed savings through reduced overnight admissions and shortened lengths of stay.

The program was implemented by a small national team, which included hospital and public health physicians, nurses, a health and social care professional (HSCP), a general practitioner (GP), and a program manager. RCPI also set up a National Advisory Group of Consultant Physicians, comprised of representative medical consultants from all over the country, and key links were established with each acute hospital. The team aimed to develop a standardized model of care for all acutely ill medical patients and ensure its full implementation nationally.

METHODS

A literature review was undertaken to develop the standardized model of care in agreement with stakeholders and in consultation with patient groups.[5] The model of care required the establishment of acute medical assessment units (AMAUs), whose main function was to assess to discharge rather than admit to assess patients.[6, 7] At that time, only 8 of the 33 acute Irish hospitals that admitted medical patients had an AMAU. However, their function and operation varied greatly. In the remaining hospitals, all medical patients went to the ED, and from there were either admitted or discharged. Delays in access to senior clinicians, diagnostics, and allied health professionals such as, Occupational Therapists, Physiotherapists and Speech and Language Therapists often resulted in delays in assessment and treatment that could lead to overnight admissions.

In the new model, all acute medical patients, except those requiring invasive monitoring, critical care, or special services such as oncology and dialysis, are referred to the AMAU by another doctor (ie. a GP, outpatient department, or ED physician), as shown in Figure 1. A senior physician in the AMAU then reviews the patient and decides to admit or discharge. This doctor can either be a dedicated physician with an interest in acute general medicine, or a specialist consultant rostered to work in the unit on a regular basis. Some patients are discharged the same day thanks to prompt review and treatment. Of those requiring overnight admission, some are streamed directly to specialist pathways (eg. coronary care unit). The remaining patients are admitted to the medical short‐stay unit (MSSU) under the care of an acute physician. Patients in the MSSU are then either discharged within 48 hours or go on to be transferred to a specialist ward.

The model of care was therefore divided into 4 care pathways. National Health Service (NHS) admission data for 2008 to 2009 were used to calculate the proportion of patients who flowed through each pathway. The NHS has a wealth of experience in the development and use of AMAUs, having started implementing these units in the early 2000s. Therefore, the NHS estimates calculated above were used to set the national benchmarks for the NAMP. The four pathways are:

1. Ambulatory Care Pathway

Patients receive safe and effective treatment and are discharged on the same day. The NAMP benchmark was that at least 25% of AMAU admissions should follow this pathway of care.

2. Medical Short‐Stay Care Pathway

This pathway was developed for those patients who require inpatient care but are not expected to stay longer than 1 or 2 nights. The program benchmark was that 31% of patients should be discharged within 48 hours.

3. Routine Specialist Inpatient Care Pathway

Approximately 33% of medical admissions are expected to stay more than 2 days and less than 14 days in the hospital and have a straightforward discharge after their acute episode of care. These patients are admitted either directly to specialist medical wards from AMAU or via the MSSU within 2 days of arrival. Care is formally handed over from the AMAU team to the appropriate consultant physician upon transfer.

4. Appropriate Care and Discharge of Complex Patients Care Pathway

Frail older patients have complex care needs that continue following discharge, and their discharge requirements must be identified early during the acute care episode. The NAMP benchmark was that no more than 11% of medical admissions would fall into this pathway and require a length of stay (LoS) exceeding 14 days.

The flow model was used to build system capacity by modeling and predicting the expected demand on each AMAU to assist in forward planning The number of assessment spaces and ward beds required for each hospital were calculated by analyzing respective admission data for 2009 and applying target lengths of stay for medical patients to the flow model. The program team carried out this analysis for each of the 32 hospitals. The model of care also identified a number of practice changes under each pathway that would be required to achieve process changes and the resulting efficiency gains. Table 1 summarizes these.

|

| Ambulatory care pathway |

| Establishment of adequate assessment area |

| National early warning score within 20 minutes |

| Access to senior decision maker within 1 hour |

| Access to rapid diagnostics and HSCP assessment |

| Development of clinical criteria for transfer between ED and AMAU |

| Liaison with discharge planner |

| Clear pathways to specialist wards and community support |

| Close liaison with GP to ensure integrated care |

| Patient experience time in AMAU to be 6 hours or less |

| Medical short‐stay care pathway |

| Establishment of adequate short‐stay unit |

| Access to senior decision maker within 12 hours of transfer from AMAU |

| Twice daily consultant ward rounds |

| Access to prioritized diagnostics and HSCP assessment |

| Integrated discharge planning |

| Routine specialist inpatient care pathway |

| Daily consultant ward rounds |

| Weekend nurse/HSCP‐facilitated discharges |

| Active discharge planning with planned dates of discharge for every patient |

| Liaison with caregivers and community supports |

| Development of clinical criteria to support bidirectional flow to community hospitals within hospital groups |

| Appropriate care and discharge of complex patients care pathway |

| Early assessment and identification of complex patients |

| Streaming to care of the elderly services where appropriate |

| Proactive multidisciplinary discharge planning and liaison with funding agencies for referral to community placements and supports |

Hospitals were also categorized into 4 divisions or models as determined by the complexity of patients they admit. Model 1 hospitals are community units with subacute inpatient beds that can care for patients with rehabilitation, respite, or palliative care needs. Model 2 hospitals are small hospitals that provide inpatient and outpatient care for low‐risk, differentiated medical patients or refer on to associated higher complexity facilities. The majority of hospitals in the country are model 3 general hospitals, admitting 50% of all medical patients. Last, model 4 hospitals are the 8 regional tertiary referral centers in Ireland. A considerable volume of their patient workload remains inpatient admissions for routine specialist inpatient care.

Measuring success in the program's quality and access objectives required the development of a bespoke information technology (IT) system that is not yet operational, and therefore these objectives could not be audited.

A number of outcome measures or key performance indicators (KPIs) were developed to assess performance under each care pathway relative to the cost objectives of the NAMP as shown in Table 2. The available hospital inpatient enquiry (HIPE) data were analyzed by the program team to establish baseline performance metrics for each hospital. Initially, these data were only available to the NAMP 1 year in arrears. However, the NAMP worked with the hospitals and the HIPE system to improve the completeness and timeliness of the HIPE reporting, so that by the third quarter of 2011 monthly data were available. Audit cycles occurred on a continuous monthly basis, with feedback provided to each hospital and follow‐up of results conducted at a local level. This allowed for analysis of performance at a national, hospital group, and individual hospital level. Of note, it was only possible to analyze readmission rates to the same facility in the absence of a national unique patient identifier, and therefore readmission rates observed were of limited use as a quality measure.

| Care Pathway | Metric | National Target | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Ambulatory care pathway | % of patients with LoS=0 | 25% | 11.5% | 12.9% | 18.8% | 23.2% |

| Medical short‐stay pathway | % of patients with LoS 12 days | 31% | 25.4% | 25.9% | 25.6% | 23.8% |

| Routine specialist inpatient pathway | % of patients with LoS>2 days | 44% | 63.1% | 61.2% | 55.6% | 53.1% |

| Complex care pathway | % of patients with LoS>14 days | 11% | 13.1% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 10.8% |

| % BDU of patients with LoS>30 days | 33% | 36.9% | 36.0% | 35.1% | 34.4% | |

| Routine and complex care pathway | Average LoS for those staying >2 days | 610 days | 12.9 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| Summary metric | Overall average LoS | 5.8 days | 8.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 6.9 |

| No. of medical discharges | 202,567 | 206,250 | 235,167 | 253,083 | ||

RESULTS

The NAMP model of care was officially launched in December 2010.[6] Thirty‐two out of the 33 Irish hospitals that admit acute medical patients had adopted the model of care by the end of 2013. The program team performed an initial diagnostic meeting at each hospital to explain the program, discuss their individual baseline metrics, and collaboratively develop a hospital‐specific implementation plan. A local implementation and unscheduled care governance team, composed of senior management members and local GPs, was established in each hospital to identify ward spaces to be developed as AMAUs, reassign nursing staff to the AMAU from the wards, and organize the recruitment of new consultants with an interest in acute general medicine. The program team performed 2 to 3 visits per year to each hospital to obtain feedback on performance and support local improvement plans using appreciative enquiry. They also organized workshops and training for physicians, nurses, managers, and data managers to improve understanding of and engagement with the program. An acute medicine nurse interest group was convened to support nurses in the transition to clinical practice with a greater focus on ambulatory care. Annual conferences were held to present and discuss annual and cumulative audit results.

Table 2 presents the national KPI results for the cost and value objectives over the 3 years of implementation. The number of medical discharges increased from 202,567 in 2010 to 253,083 in 2013. The proportion of discharges that passed through the AMAU was 29% in 2013, considerably reducing the amount of patients seen through the ED and alleviating some of the overcrowding experienced there.

The proportion of medical patients who avoided admission increased from 11.5% to 23.2% in 2013. When examining the proportion of patients discharged within 48 hours, we combined results for the ambulatory care pathway (LoS=0) and the medical short‐stay pathway (LoS=12) and found a 10% increase nationally from 36.9% to 47% in 2013. In addition, the proportion of total medical bed‐days used (BDU) for patients with LoS over 30 days also improved by 2.5%. The program achieved an overall reduction of 0.5 days in those staying over 2 days nationally, and an overall reduction in average LoS (AvLoS) for all medical inpatients of 1.6 days (from 8.5 days 6.9 days) across the 3 years.

Table 3 shows the average change in KPIs from 2010 to 2013 by hospital model group. Looking at data by hospital group allowed results to be interpreted in a national context and identify any bottlenecks in the health system.

| Care pathway | Metric | National | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Ambulatory care pathway | % of patients with LoS=0 | 11.7% | 11.5% | 12% | 11.5% |

| Medical short‐stay pathway | % of patients with LoS 12 days | 1.6% | 5% | 2.3% | 0.3% |

| Routine specialist inpatient pathway | % of patients with LoS>2 days | 10% | 6.4% | 9.8% | 11.2% |

| Complex care pathway | % of patients with LoS>14 days | 2.3% | 0.4% | 1.7% | 4.1% |

| % BDU of patients with LoS>30 days | 2.5% | 1.9% | 0.2% | 4.9% | |

| Routine and complex care pathway | Average LoS for those staying >2 days | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.4 |

| Summary metric | Overall average LoS | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 2.6 |

During the 3‐year period, the role of model 2 hospitals changed from admitting all medical patients to only admitting differentiated medical patients referred from GPs. This is reflected in their KPI results, with an increasing proportion of patients with LoS greater than 14 days and the proportion of BDU occupied by those with LoS greater than 30 days. Data from the model 2 and 3 hospitals showed a considerable increase in same‐day discharges, with a concurrent decrease in percentage of patients staying in the hospital longer than 2 days. This translated to a national reduction in AvLoS of 1 day in this hospital group. Model 2 hospitals experienced small increases in both the AvLoS for those patients staying over 2 days (0.7%) and the proportion of BDU occupied by patients staying longer than 30 days (1.9%), whereas model 3 had experienced no real change in either of these metrics (0% and 0.2%, respectively). This reflected the limited availability of long‐term care facilities and protracted funding approval process nationally during the implementation period.

Model 4 hospitals experienced improvement across all KPIs. There was an 11.2% increase in the proportion of patients discharged within 48 hours and a 1.4‐day reduction in AvLoS for patients with LoS>2 days. A notable success within this hospital category was the 4.9% reduction in percentage of BDU by patients with LoS>30 days. The AvLoS for all medical admissions in this group remained above the national target at 8.6 days but did decrease considerably by 2.6 days from its baseline.

Data on 28‐day readmission to the same facility were used as a balancing measure but were only available for the latter 2 years. We found rates of 11% and 10% for 2012 and 2013, respectively. Patient experience of these new units should be assessed, but it was not possible to measure this during the implementation period.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of the NAMP has demonstrably streamlined the care of acute medical patients in Ireland. We report the results of this national transformational change brought about by the implementation of an evidence‐based model of care. The development of a flow model for each hospital improved the patient flow from assessment to discharge. Process improvement lies at the core of all the successes achieved by the program. The practice changes highlighted in Table 1 were pivotal in streamlining and improving the care of acutely ill medical patients. The focus on early access to senior decision making, early diagnostics, and a continuous, coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care and discharge were central to the effective functioning of the AMAU and the resulting increase in avoided admissions.

Shortened lengths of stay are associated with better clinical outcomes and reduced exposure of patients to risk, and result in significant cost efficiencies accrued to the Irish health services.[2, 8] The adoption of ambulatory care and medical short‐stay pathways facilitated the 11.7% increase in avoided admissions and the reduction of 1.6 days in overall AvLoS nationally. This translates to significant cost savings for the Irish health system and likely improves clinical outcomes and reduced morbidity. We estimated these cost savings to be approximately 88.2 million by multiplying the number of bed days saved by the marginal cost of a bed day, which was quoted at 246 in 2012 by our Healthcare Pricing Office.

Thirty‐two of the 33 Irish hospitals that admit acute medical patients are now operating the program and achieving improvements in performance, as evidenced by ongoing audits. The priority given to the program by the RCPI and HSE has enabled the assignment of local implementation teams sustaining the focus on quality improvement at a local level. It also allowed for modest seed funding to be allocated for the appointment of 36 new consultants with an interest in acute general medicine. The cost of these additional consultants is offset by the considerable savings achieved through efficiency gains. An important challenge to implementation was the change in mindset required from local healthcare staff to divert patients away from the ED to the AMAU, and reassign staff and resources from other inpatient wards to the new unit. Visible clinical leadership from clinical directors, acute medicine hospital leads, senior nursing, and HSCP, together with management and local GPs, was essential in effecting this change. The program team also offered considerable support in this regard through advocacy and promotion of the program nationally. The implementation of the 4 care pathways represents a generational change in how medicine is practiced in Ireland. The development of acute medicine as a new specialty was strongly fostered by the program.

A number of disease‐specific clinical programs began operation during the implementation period and achieved reductions in AvLoS for some conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure, contributing to varying degrees (2%6%) to the bed‐days savings achieved by the NAMP. During the 3‐year period, there was a 25% increase in medical discharges. This is partly due to the changing demographics and epidemiology of chronic diseases in the Irish population. This increased demand was absorbed by the system with no increase in acute bed usage. We estimated that approximately 1000 additional acute beds would have been required if the NAMP efficiencies had not been achieved. Concurrent financial constraints compounded the stress on the public health system by limiting the available staff and resources for the new AMAUs and by reducing the number of community and nursing home beds available. This obstructed the flow of older and frailer patients out of the acute setting and impacted negatively on the performance of some hospitals.

An important limitation in auditing success in the quality and access aims of the program was the absence of IT systems within the AMAUs. These have since been specified by the NAMP but have not yet been delivered to the service areas. In addition, a bespoke user interface, which allows hospitals to manipulate and benchmark their own performance, is being developed. This will facilitate more in‐depth auditing within hospitals at the ward and consultant team level. The lack of a unique patient identifier hindered our ability to measure true 28‐day readmission rates, which is a useful quality indicator.

Despite these contextual, cultural, and structural challenges, the NAMP successfully implemented an evidence‐based model of care across the country. Through its implementation, tangible improvements to the Irish health system were observed with expected benefits to the patient. The program successfully instituted an ongoing audit cycle to promote continuous improvement and identified areas for future work to build on the successes achieved.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

In 2009, Irish hospitals were experiencing ongoing and increasing overcrowding of emergency departments (EDs). This overcrowding and subsequent assessment delays are both associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates.[1, 2, 3, 4] The prevailing culture in many larger hospitals was to prioritize subspecialty care at the expense of the assessment and management of patients with undifferentiated acute medical presentations with nonspecific symptoms. The National Acute Medicine Programme (NAMP) was set up in 2010 by the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland (RCPI) and the Health Service Executive (HSE) to address this unsatisfactory management of acutely ill medical patients.

The objectives of the NAMP are categorized under 3 quality improvement principles: (1) Quality: to improve quality of care and patient safety by ensuring patients are seen by a nurse within 20 minutes and a senior doctor within 1 hour of arrival. (2) Access: to improve access by ensuring that the patient journey from presentation to decision to admit or discharge does not exceed 6 hours and to eliminate extended waiting periods on gurneys for medical patients. (3) Cost: to reduce cost and increase value by achieving bed savings through reduced overnight admissions and shortened lengths of stay.

The program was implemented by a small national team, which included hospital and public health physicians, nurses, a health and social care professional (HSCP), a general practitioner (GP), and a program manager. RCPI also set up a National Advisory Group of Consultant Physicians, comprised of representative medical consultants from all over the country, and key links were established with each acute hospital. The team aimed to develop a standardized model of care for all acutely ill medical patients and ensure its full implementation nationally.

METHODS

A literature review was undertaken to develop the standardized model of care in agreement with stakeholders and in consultation with patient groups.[5] The model of care required the establishment of acute medical assessment units (AMAUs), whose main function was to assess to discharge rather than admit to assess patients.[6, 7] At that time, only 8 of the 33 acute Irish hospitals that admitted medical patients had an AMAU. However, their function and operation varied greatly. In the remaining hospitals, all medical patients went to the ED, and from there were either admitted or discharged. Delays in access to senior clinicians, diagnostics, and allied health professionals such as, Occupational Therapists, Physiotherapists and Speech and Language Therapists often resulted in delays in assessment and treatment that could lead to overnight admissions.

In the new model, all acute medical patients, except those requiring invasive monitoring, critical care, or special services such as oncology and dialysis, are referred to the AMAU by another doctor (ie. a GP, outpatient department, or ED physician), as shown in Figure 1. A senior physician in the AMAU then reviews the patient and decides to admit or discharge. This doctor can either be a dedicated physician with an interest in acute general medicine, or a specialist consultant rostered to work in the unit on a regular basis. Some patients are discharged the same day thanks to prompt review and treatment. Of those requiring overnight admission, some are streamed directly to specialist pathways (eg. coronary care unit). The remaining patients are admitted to the medical short‐stay unit (MSSU) under the care of an acute physician. Patients in the MSSU are then either discharged within 48 hours or go on to be transferred to a specialist ward.

The model of care was therefore divided into 4 care pathways. National Health Service (NHS) admission data for 2008 to 2009 were used to calculate the proportion of patients who flowed through each pathway. The NHS has a wealth of experience in the development and use of AMAUs, having started implementing these units in the early 2000s. Therefore, the NHS estimates calculated above were used to set the national benchmarks for the NAMP. The four pathways are:

1. Ambulatory Care Pathway

Patients receive safe and effective treatment and are discharged on the same day. The NAMP benchmark was that at least 25% of AMAU admissions should follow this pathway of care.

2. Medical Short‐Stay Care Pathway

This pathway was developed for those patients who require inpatient care but are not expected to stay longer than 1 or 2 nights. The program benchmark was that 31% of patients should be discharged within 48 hours.

3. Routine Specialist Inpatient Care Pathway

Approximately 33% of medical admissions are expected to stay more than 2 days and less than 14 days in the hospital and have a straightforward discharge after their acute episode of care. These patients are admitted either directly to specialist medical wards from AMAU or via the MSSU within 2 days of arrival. Care is formally handed over from the AMAU team to the appropriate consultant physician upon transfer.

4. Appropriate Care and Discharge of Complex Patients Care Pathway

Frail older patients have complex care needs that continue following discharge, and their discharge requirements must be identified early during the acute care episode. The NAMP benchmark was that no more than 11% of medical admissions would fall into this pathway and require a length of stay (LoS) exceeding 14 days.

The flow model was used to build system capacity by modeling and predicting the expected demand on each AMAU to assist in forward planning The number of assessment spaces and ward beds required for each hospital were calculated by analyzing respective admission data for 2009 and applying target lengths of stay for medical patients to the flow model. The program team carried out this analysis for each of the 32 hospitals. The model of care also identified a number of practice changes under each pathway that would be required to achieve process changes and the resulting efficiency gains. Table 1 summarizes these.

|

| Ambulatory care pathway |

| Establishment of adequate assessment area |

| National early warning score within 20 minutes |

| Access to senior decision maker within 1 hour |

| Access to rapid diagnostics and HSCP assessment |

| Development of clinical criteria for transfer between ED and AMAU |

| Liaison with discharge planner |

| Clear pathways to specialist wards and community support |

| Close liaison with GP to ensure integrated care |

| Patient experience time in AMAU to be 6 hours or less |

| Medical short‐stay care pathway |

| Establishment of adequate short‐stay unit |

| Access to senior decision maker within 12 hours of transfer from AMAU |

| Twice daily consultant ward rounds |

| Access to prioritized diagnostics and HSCP assessment |

| Integrated discharge planning |

| Routine specialist inpatient care pathway |

| Daily consultant ward rounds |

| Weekend nurse/HSCP‐facilitated discharges |

| Active discharge planning with planned dates of discharge for every patient |

| Liaison with caregivers and community supports |

| Development of clinical criteria to support bidirectional flow to community hospitals within hospital groups |

| Appropriate care and discharge of complex patients care pathway |

| Early assessment and identification of complex patients |

| Streaming to care of the elderly services where appropriate |

| Proactive multidisciplinary discharge planning and liaison with funding agencies for referral to community placements and supports |

Hospitals were also categorized into 4 divisions or models as determined by the complexity of patients they admit. Model 1 hospitals are community units with subacute inpatient beds that can care for patients with rehabilitation, respite, or palliative care needs. Model 2 hospitals are small hospitals that provide inpatient and outpatient care for low‐risk, differentiated medical patients or refer on to associated higher complexity facilities. The majority of hospitals in the country are model 3 general hospitals, admitting 50% of all medical patients. Last, model 4 hospitals are the 8 regional tertiary referral centers in Ireland. A considerable volume of their patient workload remains inpatient admissions for routine specialist inpatient care.

Measuring success in the program's quality and access objectives required the development of a bespoke information technology (IT) system that is not yet operational, and therefore these objectives could not be audited.

A number of outcome measures or key performance indicators (KPIs) were developed to assess performance under each care pathway relative to the cost objectives of the NAMP as shown in Table 2. The available hospital inpatient enquiry (HIPE) data were analyzed by the program team to establish baseline performance metrics for each hospital. Initially, these data were only available to the NAMP 1 year in arrears. However, the NAMP worked with the hospitals and the HIPE system to improve the completeness and timeliness of the HIPE reporting, so that by the third quarter of 2011 monthly data were available. Audit cycles occurred on a continuous monthly basis, with feedback provided to each hospital and follow‐up of results conducted at a local level. This allowed for analysis of performance at a national, hospital group, and individual hospital level. Of note, it was only possible to analyze readmission rates to the same facility in the absence of a national unique patient identifier, and therefore readmission rates observed were of limited use as a quality measure.

| Care Pathway | Metric | National Target | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Ambulatory care pathway | % of patients with LoS=0 | 25% | 11.5% | 12.9% | 18.8% | 23.2% |

| Medical short‐stay pathway | % of patients with LoS 12 days | 31% | 25.4% | 25.9% | 25.6% | 23.8% |

| Routine specialist inpatient pathway | % of patients with LoS>2 days | 44% | 63.1% | 61.2% | 55.6% | 53.1% |

| Complex care pathway | % of patients with LoS>14 days | 11% | 13.1% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 10.8% |

| % BDU of patients with LoS>30 days | 33% | 36.9% | 36.0% | 35.1% | 34.4% | |

| Routine and complex care pathway | Average LoS for those staying >2 days | 610 days | 12.9 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| Summary metric | Overall average LoS | 5.8 days | 8.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 6.9 |

| No. of medical discharges | 202,567 | 206,250 | 235,167 | 253,083 | ||

RESULTS

The NAMP model of care was officially launched in December 2010.[6] Thirty‐two out of the 33 Irish hospitals that admit acute medical patients had adopted the model of care by the end of 2013. The program team performed an initial diagnostic meeting at each hospital to explain the program, discuss their individual baseline metrics, and collaboratively develop a hospital‐specific implementation plan. A local implementation and unscheduled care governance team, composed of senior management members and local GPs, was established in each hospital to identify ward spaces to be developed as AMAUs, reassign nursing staff to the AMAU from the wards, and organize the recruitment of new consultants with an interest in acute general medicine. The program team performed 2 to 3 visits per year to each hospital to obtain feedback on performance and support local improvement plans using appreciative enquiry. They also organized workshops and training for physicians, nurses, managers, and data managers to improve understanding of and engagement with the program. An acute medicine nurse interest group was convened to support nurses in the transition to clinical practice with a greater focus on ambulatory care. Annual conferences were held to present and discuss annual and cumulative audit results.

Table 2 presents the national KPI results for the cost and value objectives over the 3 years of implementation. The number of medical discharges increased from 202,567 in 2010 to 253,083 in 2013. The proportion of discharges that passed through the AMAU was 29% in 2013, considerably reducing the amount of patients seen through the ED and alleviating some of the overcrowding experienced there.

The proportion of medical patients who avoided admission increased from 11.5% to 23.2% in 2013. When examining the proportion of patients discharged within 48 hours, we combined results for the ambulatory care pathway (LoS=0) and the medical short‐stay pathway (LoS=12) and found a 10% increase nationally from 36.9% to 47% in 2013. In addition, the proportion of total medical bed‐days used (BDU) for patients with LoS over 30 days also improved by 2.5%. The program achieved an overall reduction of 0.5 days in those staying over 2 days nationally, and an overall reduction in average LoS (AvLoS) for all medical inpatients of 1.6 days (from 8.5 days 6.9 days) across the 3 years.

Table 3 shows the average change in KPIs from 2010 to 2013 by hospital model group. Looking at data by hospital group allowed results to be interpreted in a national context and identify any bottlenecks in the health system.

| Care pathway | Metric | National | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Ambulatory care pathway | % of patients with LoS=0 | 11.7% | 11.5% | 12% | 11.5% |

| Medical short‐stay pathway | % of patients with LoS 12 days | 1.6% | 5% | 2.3% | 0.3% |

| Routine specialist inpatient pathway | % of patients with LoS>2 days | 10% | 6.4% | 9.8% | 11.2% |

| Complex care pathway | % of patients with LoS>14 days | 2.3% | 0.4% | 1.7% | 4.1% |

| % BDU of patients with LoS>30 days | 2.5% | 1.9% | 0.2% | 4.9% | |

| Routine and complex care pathway | Average LoS for those staying >2 days | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.4 |

| Summary metric | Overall average LoS | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 2.6 |

During the 3‐year period, the role of model 2 hospitals changed from admitting all medical patients to only admitting differentiated medical patients referred from GPs. This is reflected in their KPI results, with an increasing proportion of patients with LoS greater than 14 days and the proportion of BDU occupied by those with LoS greater than 30 days. Data from the model 2 and 3 hospitals showed a considerable increase in same‐day discharges, with a concurrent decrease in percentage of patients staying in the hospital longer than 2 days. This translated to a national reduction in AvLoS of 1 day in this hospital group. Model 2 hospitals experienced small increases in both the AvLoS for those patients staying over 2 days (0.7%) and the proportion of BDU occupied by patients staying longer than 30 days (1.9%), whereas model 3 had experienced no real change in either of these metrics (0% and 0.2%, respectively). This reflected the limited availability of long‐term care facilities and protracted funding approval process nationally during the implementation period.

Model 4 hospitals experienced improvement across all KPIs. There was an 11.2% increase in the proportion of patients discharged within 48 hours and a 1.4‐day reduction in AvLoS for patients with LoS>2 days. A notable success within this hospital category was the 4.9% reduction in percentage of BDU by patients with LoS>30 days. The AvLoS for all medical admissions in this group remained above the national target at 8.6 days but did decrease considerably by 2.6 days from its baseline.

Data on 28‐day readmission to the same facility were used as a balancing measure but were only available for the latter 2 years. We found rates of 11% and 10% for 2012 and 2013, respectively. Patient experience of these new units should be assessed, but it was not possible to measure this during the implementation period.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of the NAMP has demonstrably streamlined the care of acute medical patients in Ireland. We report the results of this national transformational change brought about by the implementation of an evidence‐based model of care. The development of a flow model for each hospital improved the patient flow from assessment to discharge. Process improvement lies at the core of all the successes achieved by the program. The practice changes highlighted in Table 1 were pivotal in streamlining and improving the care of acutely ill medical patients. The focus on early access to senior decision making, early diagnostics, and a continuous, coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care and discharge were central to the effective functioning of the AMAU and the resulting increase in avoided admissions.

Shortened lengths of stay are associated with better clinical outcomes and reduced exposure of patients to risk, and result in significant cost efficiencies accrued to the Irish health services.[2, 8] The adoption of ambulatory care and medical short‐stay pathways facilitated the 11.7% increase in avoided admissions and the reduction of 1.6 days in overall AvLoS nationally. This translates to significant cost savings for the Irish health system and likely improves clinical outcomes and reduced morbidity. We estimated these cost savings to be approximately 88.2 million by multiplying the number of bed days saved by the marginal cost of a bed day, which was quoted at 246 in 2012 by our Healthcare Pricing Office.

Thirty‐two of the 33 Irish hospitals that admit acute medical patients are now operating the program and achieving improvements in performance, as evidenced by ongoing audits. The priority given to the program by the RCPI and HSE has enabled the assignment of local implementation teams sustaining the focus on quality improvement at a local level. It also allowed for modest seed funding to be allocated for the appointment of 36 new consultants with an interest in acute general medicine. The cost of these additional consultants is offset by the considerable savings achieved through efficiency gains. An important challenge to implementation was the change in mindset required from local healthcare staff to divert patients away from the ED to the AMAU, and reassign staff and resources from other inpatient wards to the new unit. Visible clinical leadership from clinical directors, acute medicine hospital leads, senior nursing, and HSCP, together with management and local GPs, was essential in effecting this change. The program team also offered considerable support in this regard through advocacy and promotion of the program nationally. The implementation of the 4 care pathways represents a generational change in how medicine is practiced in Ireland. The development of acute medicine as a new specialty was strongly fostered by the program.

A number of disease‐specific clinical programs began operation during the implementation period and achieved reductions in AvLoS for some conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure, contributing to varying degrees (2%6%) to the bed‐days savings achieved by the NAMP. During the 3‐year period, there was a 25% increase in medical discharges. This is partly due to the changing demographics and epidemiology of chronic diseases in the Irish population. This increased demand was absorbed by the system with no increase in acute bed usage. We estimated that approximately 1000 additional acute beds would have been required if the NAMP efficiencies had not been achieved. Concurrent financial constraints compounded the stress on the public health system by limiting the available staff and resources for the new AMAUs and by reducing the number of community and nursing home beds available. This obstructed the flow of older and frailer patients out of the acute setting and impacted negatively on the performance of some hospitals.

An important limitation in auditing success in the quality and access aims of the program was the absence of IT systems within the AMAUs. These have since been specified by the NAMP but have not yet been delivered to the service areas. In addition, a bespoke user interface, which allows hospitals to manipulate and benchmark their own performance, is being developed. This will facilitate more in‐depth auditing within hospitals at the ward and consultant team level. The lack of a unique patient identifier hindered our ability to measure true 28‐day readmission rates, which is a useful quality indicator.

Despite these contextual, cultural, and structural challenges, the NAMP successfully implemented an evidence‐based model of care across the country. Through its implementation, tangible improvements to the Irish health system were observed with expected benefits to the patient. The program successfully instituted an ongoing audit cycle to promote continuous improvement and identified areas for future work to build on the successes achieved.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- ,. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient outcomes: a literature review. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2011;33(1):39–54.

- , , , et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):605–611.e6.

- , , . The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(2):106–115.

- , , , et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–10.

- Acute medical assessment units: a literature review. 2012. [Unpublished Manuscript]