User login

The Use of Sodium Sulfacetamide in Dermatology

Sodium sulfacetamide has various uses in the field of dermatology due to its anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. It has been shown to be effective in the management of a variety of inflammatory facial dermatoses, including papulopustular rosacea, acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis. We review the mechanism of action, pharmacology and formulations, clinical uses, and adverse effects of sodium sulfacetamide as a dermatologic treatment.

Mechanism of Action

Sodium sulfacetamide is a sulfonamide-type antibacterial agent. Its mechanism of action is the inhibition of bacterial dihydropteroate synthetase, which prevents the conversion of p-aminobenzoic acid to folic acid. This process causes a bacteriostatic effect on the growth of several gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including Propionibacterium acnes.1,2

The effectiveness of sodium sulfacetamide is increased when used in combination with sulfur, which has keratolytic, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic effects. The addition of hydrocortisone has been reported to increase the effectiveness of both agents.3

Pharmacology

Sodium sulfacetamide is highly soluble at the physiologic pH of 7.4, which contributes to its high level of penetration and absorption.4 An in vitro study showed percutaneous absorption of sodium sulfacetamide to be around 4%.5 Sulfonamides are metabolized mainly by the liver and are excreted by the kidneys.

Formulations

The most common concentrations of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur are 10% and 5%, respectively. A wide variety of sulfacetamide-containing products are available, many of which are marketed to treat specific conditions depending on additional ingredients or the type of delivery system.

Clinical Uses

Topical formulations of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur have proven to be efficacious in the management of rosacea, with a typical regimen consisting of twice-daily application for 8 weeks.6 The sulfur in the formulation has the additional benefit of targeting Demodex mites, which are implicated as a contributing factor in some cases of rosacea.7 Sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% lotion was more effective in improving the erythema, papulopustules, and overall severity of rosacea as compared to metronidazole gel 0.75%.8 Other studies have reported increased efficacy when sodium sulfacetamide and topical sulfur are used along with metronidazole.9,10

Sodium sulfacetamide also has shown efficacy against acne. Its antibacterial and drying properties have been shown to decrease the number of inflammatory lesions and comedones, and in the treatment of acne vulgaris, no sensitivity reactions have been observed.2 Also, unlike topical antibiotics, cases of P acnes resistance to topical sulfur products have not been widely reported. Studies have demonstrated that twice-daily use of sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% for 12 weeks decreases inflammatory acne lesions by 80.4% to 83%.11,12

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic infection of the skin caused by Malassezia species. One study investigated the use of sodium sulfacetamide ointment and soap to treat seborrheic dermatitis and found that the condition was either improved or completely controlled in 93% (71/76) of cases.4 Sodium sulfacetamide lotion was an effective treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in 89% (54/61) of patients with scalp involvement and 68% (30/44) of patients with glabrous skin involvement.13

Perioral dermatitis is characterized by groups of erythematous papules and pustules localized around the mouth. The use of topical sodium sulfacetamide along with oral tetracyclines has been demonstrated to consistently clear lesions in most patients with perioral dermatitis.14 Sodium sulfacetamide is unique in that it is not associated with the excessive erythema and irritation often found with retinoic acid and benzoyl peroxide.15 Unfortunately, however, there have been no well-controlled trials to compare the efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide to other topical therapies for this condition.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects from sodium sulfacetamide are rare and generally are limited to cutaneous reactions including dryness, erythema, pruritus, and discomfort.1 Periocular use of sodium sulfacetamide can cause conjunctival irritation. One study reported that 19% (6/31) of patients experienced local reactions but most were considered mild.9 Rare but serious reactions including erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported from ophthalmic use.16,17

A common limiting factor to sodium sulfacetamide preparations that include elemental sulfur is the offensive smell, which has hindered patient compliance in the past; however, pharmaceutical companies have attempted to create more tolerable products without the odor.10 One study found that the tolerability of a sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% foam using a rinse-off method of application was excellent, with only 33% (8/24) of participants commenting on the smell.18 Another limiting factor of sodium sulfacetamide preparations containing sulfur is orange-brown discoloration when combined with benzoyl peroxide, which does not affect the skin but may stain clothing.19

Sodium sulfacetamide is rendered less effective when combined with silver-containing products.20 No other notable drug interactions are known; however, oral sulfonamides are known to interact with several drugs, including cyclosporine and phenytoin.21,22

Contraindications

Sodium sulfacetamide is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to sulfonamides, sulfur, or any other component of the preparation. It is a pregnancy category C drug, and pregnant women should only use sodium sulfacetamide if it is the only modality to treat the condition or the benefits outweigh the risks. Although there are no known reports of problems related to topical sodium sulfacetamide during pregnancy, the use of oral sulfonamides during pregnancy can increase the risk for neonatal jaundice.23 Likewise, caution should be exercised in prescribing this product to nursing women, as systemic sulfonamide antibacterials are well known to cause kernicterus in nursing neonates.1

Conclusion

The efficacy and safety of sodium sulfacetamide, used alone or in combination with sulfur, has been demonstrated in the treatment of rosacea, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis. Advances in formulation technology to decrease odor and irritation have allowed for more use of this product. Further studies will help elucidate the role that sodium sulfacetamide should play in the treatment of inflammatory dermatoses in comparison to other available products.

1. Akhavan A, Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:473-492.

2. Gupta AK, Nicol K. The use of sulfur in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:427-431.

3. Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Topical antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:445-459.

4. Duemling WM. Sodium sulfacetamide in topical therapy. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:75-82.

5. Sodium sulfacetamide. Drugs.com Web site. http://drugs.com/pro/sodium-sulfacetamide.html. Revised December 2012. Accessed June 16, 2015.

6. Sauder DN, Miller R, Gratton D, et al. The treatment of rosacea: the safety and efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% lotion (Novacet) is demonstrated in a double-blind study. J Dermatol Treat. 1997;8:79-85.

7. Trumbore MW, Goldstein JA, Gurge RM. Treatment of papulopustular rosacea with sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% emollient foam. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:299-304.

8. Lebwohl MG, Medansky RS, Russo CL, et al. The comparative efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% lotion and metronidazole 0.75% gel in the treatment of rosacea. J Geriatr Dermatol. 1995;3:183-185.

9. Nally JB, Berson DS. Topical therapies for rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:23-26.

10. Pelle MT, Crawford GH, James WD. Rosacea II: therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:499-512.

11. Tarimci N, Sener S, Kilinç T. Topical sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur lotion. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22:301.

12. Breneman DL, Ariano MC. Successful treatment of acne vulgaris in women with a new topical sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur lotion. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:365-367.

13. Whelan ST. Sodium sulfacetamide for seborrheic dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:724.

14. Bendl BJ. Perioral dermatitis: etiology and treatment. Cutis. 1976;17:903-908.

15. Olansky S. Old drug—in a new system—revisited. Cutis. 1977;19:852-854.

16. Genvert GI, Cohen EJ, Donnenfeld ED, et al. Erythema multiforme after use of topical sulfacetamide. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:465-468.

17. Rubin Z. Ophthalmic sulfonamide-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:235-236.

18. Draelos ZD. The multifunctionality of 10% sodium sulfacetamide, 5% sulfur emollient foam in the treatment of inflammatory facial dermatoses. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:234-246.

19. Dubina MI, Fleischer AB. Interaction of topical sulfacetamide and topical dapsone with benzoyl peroxide. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1027-1029.

20. Sodium sulfacetamide – sulfacetamide sodium liquid. DailyMed Web site. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=0d92c55b-5b54-4f5d-8921-24e4e877ae50. Accessed June 17, 2015.

21. Spes CH, Angermann CE, Stempfle HU, et al. Sulfadiazine therapy for toxoplasmosis in heart transplant recipients decreases cyclosporine concentration. Clin Investig. 1992;70:752-754.

22. Hansen JM, Kampmann JP, Siersbaek-Nielsen K, et al. The effect of different sulfonamides on phenytoin metabolism in man. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1979;624:106-110.

23. Bradley JS, Sauberan JB. Antimicrobial agents. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1453-1483.

Sodium sulfacetamide has various uses in the field of dermatology due to its anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. It has been shown to be effective in the management of a variety of inflammatory facial dermatoses, including papulopustular rosacea, acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis. We review the mechanism of action, pharmacology and formulations, clinical uses, and adverse effects of sodium sulfacetamide as a dermatologic treatment.

Mechanism of Action

Sodium sulfacetamide is a sulfonamide-type antibacterial agent. Its mechanism of action is the inhibition of bacterial dihydropteroate synthetase, which prevents the conversion of p-aminobenzoic acid to folic acid. This process causes a bacteriostatic effect on the growth of several gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including Propionibacterium acnes.1,2

The effectiveness of sodium sulfacetamide is increased when used in combination with sulfur, which has keratolytic, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic effects. The addition of hydrocortisone has been reported to increase the effectiveness of both agents.3

Pharmacology

Sodium sulfacetamide is highly soluble at the physiologic pH of 7.4, which contributes to its high level of penetration and absorption.4 An in vitro study showed percutaneous absorption of sodium sulfacetamide to be around 4%.5 Sulfonamides are metabolized mainly by the liver and are excreted by the kidneys.

Formulations

The most common concentrations of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur are 10% and 5%, respectively. A wide variety of sulfacetamide-containing products are available, many of which are marketed to treat specific conditions depending on additional ingredients or the type of delivery system.

Clinical Uses

Topical formulations of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur have proven to be efficacious in the management of rosacea, with a typical regimen consisting of twice-daily application for 8 weeks.6 The sulfur in the formulation has the additional benefit of targeting Demodex mites, which are implicated as a contributing factor in some cases of rosacea.7 Sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% lotion was more effective in improving the erythema, papulopustules, and overall severity of rosacea as compared to metronidazole gel 0.75%.8 Other studies have reported increased efficacy when sodium sulfacetamide and topical sulfur are used along with metronidazole.9,10

Sodium sulfacetamide also has shown efficacy against acne. Its antibacterial and drying properties have been shown to decrease the number of inflammatory lesions and comedones, and in the treatment of acne vulgaris, no sensitivity reactions have been observed.2 Also, unlike topical antibiotics, cases of P acnes resistance to topical sulfur products have not been widely reported. Studies have demonstrated that twice-daily use of sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% for 12 weeks decreases inflammatory acne lesions by 80.4% to 83%.11,12

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic infection of the skin caused by Malassezia species. One study investigated the use of sodium sulfacetamide ointment and soap to treat seborrheic dermatitis and found that the condition was either improved or completely controlled in 93% (71/76) of cases.4 Sodium sulfacetamide lotion was an effective treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in 89% (54/61) of patients with scalp involvement and 68% (30/44) of patients with glabrous skin involvement.13

Perioral dermatitis is characterized by groups of erythematous papules and pustules localized around the mouth. The use of topical sodium sulfacetamide along with oral tetracyclines has been demonstrated to consistently clear lesions in most patients with perioral dermatitis.14 Sodium sulfacetamide is unique in that it is not associated with the excessive erythema and irritation often found with retinoic acid and benzoyl peroxide.15 Unfortunately, however, there have been no well-controlled trials to compare the efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide to other topical therapies for this condition.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects from sodium sulfacetamide are rare and generally are limited to cutaneous reactions including dryness, erythema, pruritus, and discomfort.1 Periocular use of sodium sulfacetamide can cause conjunctival irritation. One study reported that 19% (6/31) of patients experienced local reactions but most were considered mild.9 Rare but serious reactions including erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported from ophthalmic use.16,17

A common limiting factor to sodium sulfacetamide preparations that include elemental sulfur is the offensive smell, which has hindered patient compliance in the past; however, pharmaceutical companies have attempted to create more tolerable products without the odor.10 One study found that the tolerability of a sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% foam using a rinse-off method of application was excellent, with only 33% (8/24) of participants commenting on the smell.18 Another limiting factor of sodium sulfacetamide preparations containing sulfur is orange-brown discoloration when combined with benzoyl peroxide, which does not affect the skin but may stain clothing.19

Sodium sulfacetamide is rendered less effective when combined with silver-containing products.20 No other notable drug interactions are known; however, oral sulfonamides are known to interact with several drugs, including cyclosporine and phenytoin.21,22

Contraindications

Sodium sulfacetamide is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to sulfonamides, sulfur, or any other component of the preparation. It is a pregnancy category C drug, and pregnant women should only use sodium sulfacetamide if it is the only modality to treat the condition or the benefits outweigh the risks. Although there are no known reports of problems related to topical sodium sulfacetamide during pregnancy, the use of oral sulfonamides during pregnancy can increase the risk for neonatal jaundice.23 Likewise, caution should be exercised in prescribing this product to nursing women, as systemic sulfonamide antibacterials are well known to cause kernicterus in nursing neonates.1

Conclusion

The efficacy and safety of sodium sulfacetamide, used alone or in combination with sulfur, has been demonstrated in the treatment of rosacea, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis. Advances in formulation technology to decrease odor and irritation have allowed for more use of this product. Further studies will help elucidate the role that sodium sulfacetamide should play in the treatment of inflammatory dermatoses in comparison to other available products.

Sodium sulfacetamide has various uses in the field of dermatology due to its anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. It has been shown to be effective in the management of a variety of inflammatory facial dermatoses, including papulopustular rosacea, acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis. We review the mechanism of action, pharmacology and formulations, clinical uses, and adverse effects of sodium sulfacetamide as a dermatologic treatment.

Mechanism of Action

Sodium sulfacetamide is a sulfonamide-type antibacterial agent. Its mechanism of action is the inhibition of bacterial dihydropteroate synthetase, which prevents the conversion of p-aminobenzoic acid to folic acid. This process causes a bacteriostatic effect on the growth of several gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including Propionibacterium acnes.1,2

The effectiveness of sodium sulfacetamide is increased when used in combination with sulfur, which has keratolytic, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic effects. The addition of hydrocortisone has been reported to increase the effectiveness of both agents.3

Pharmacology

Sodium sulfacetamide is highly soluble at the physiologic pH of 7.4, which contributes to its high level of penetration and absorption.4 An in vitro study showed percutaneous absorption of sodium sulfacetamide to be around 4%.5 Sulfonamides are metabolized mainly by the liver and are excreted by the kidneys.

Formulations

The most common concentrations of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur are 10% and 5%, respectively. A wide variety of sulfacetamide-containing products are available, many of which are marketed to treat specific conditions depending on additional ingredients or the type of delivery system.

Clinical Uses

Topical formulations of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur have proven to be efficacious in the management of rosacea, with a typical regimen consisting of twice-daily application for 8 weeks.6 The sulfur in the formulation has the additional benefit of targeting Demodex mites, which are implicated as a contributing factor in some cases of rosacea.7 Sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% lotion was more effective in improving the erythema, papulopustules, and overall severity of rosacea as compared to metronidazole gel 0.75%.8 Other studies have reported increased efficacy when sodium sulfacetamide and topical sulfur are used along with metronidazole.9,10

Sodium sulfacetamide also has shown efficacy against acne. Its antibacterial and drying properties have been shown to decrease the number of inflammatory lesions and comedones, and in the treatment of acne vulgaris, no sensitivity reactions have been observed.2 Also, unlike topical antibiotics, cases of P acnes resistance to topical sulfur products have not been widely reported. Studies have demonstrated that twice-daily use of sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% for 12 weeks decreases inflammatory acne lesions by 80.4% to 83%.11,12

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common chronic infection of the skin caused by Malassezia species. One study investigated the use of sodium sulfacetamide ointment and soap to treat seborrheic dermatitis and found that the condition was either improved or completely controlled in 93% (71/76) of cases.4 Sodium sulfacetamide lotion was an effective treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in 89% (54/61) of patients with scalp involvement and 68% (30/44) of patients with glabrous skin involvement.13

Perioral dermatitis is characterized by groups of erythematous papules and pustules localized around the mouth. The use of topical sodium sulfacetamide along with oral tetracyclines has been demonstrated to consistently clear lesions in most patients with perioral dermatitis.14 Sodium sulfacetamide is unique in that it is not associated with the excessive erythema and irritation often found with retinoic acid and benzoyl peroxide.15 Unfortunately, however, there have been no well-controlled trials to compare the efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide to other topical therapies for this condition.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects from sodium sulfacetamide are rare and generally are limited to cutaneous reactions including dryness, erythema, pruritus, and discomfort.1 Periocular use of sodium sulfacetamide can cause conjunctival irritation. One study reported that 19% (6/31) of patients experienced local reactions but most were considered mild.9 Rare but serious reactions including erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported from ophthalmic use.16,17

A common limiting factor to sodium sulfacetamide preparations that include elemental sulfur is the offensive smell, which has hindered patient compliance in the past; however, pharmaceutical companies have attempted to create more tolerable products without the odor.10 One study found that the tolerability of a sodium sulfacetamide 10%–sulfur 5% foam using a rinse-off method of application was excellent, with only 33% (8/24) of participants commenting on the smell.18 Another limiting factor of sodium sulfacetamide preparations containing sulfur is orange-brown discoloration when combined with benzoyl peroxide, which does not affect the skin but may stain clothing.19

Sodium sulfacetamide is rendered less effective when combined with silver-containing products.20 No other notable drug interactions are known; however, oral sulfonamides are known to interact with several drugs, including cyclosporine and phenytoin.21,22

Contraindications

Sodium sulfacetamide is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to sulfonamides, sulfur, or any other component of the preparation. It is a pregnancy category C drug, and pregnant women should only use sodium sulfacetamide if it is the only modality to treat the condition or the benefits outweigh the risks. Although there are no known reports of problems related to topical sodium sulfacetamide during pregnancy, the use of oral sulfonamides during pregnancy can increase the risk for neonatal jaundice.23 Likewise, caution should be exercised in prescribing this product to nursing women, as systemic sulfonamide antibacterials are well known to cause kernicterus in nursing neonates.1

Conclusion

The efficacy and safety of sodium sulfacetamide, used alone or in combination with sulfur, has been demonstrated in the treatment of rosacea, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis. Advances in formulation technology to decrease odor and irritation have allowed for more use of this product. Further studies will help elucidate the role that sodium sulfacetamide should play in the treatment of inflammatory dermatoses in comparison to other available products.

1. Akhavan A, Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:473-492.

2. Gupta AK, Nicol K. The use of sulfur in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:427-431.

3. Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Topical antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:445-459.

4. Duemling WM. Sodium sulfacetamide in topical therapy. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:75-82.

5. Sodium sulfacetamide. Drugs.com Web site. http://drugs.com/pro/sodium-sulfacetamide.html. Revised December 2012. Accessed June 16, 2015.

6. Sauder DN, Miller R, Gratton D, et al. The treatment of rosacea: the safety and efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% lotion (Novacet) is demonstrated in a double-blind study. J Dermatol Treat. 1997;8:79-85.

7. Trumbore MW, Goldstein JA, Gurge RM. Treatment of papulopustular rosacea with sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% emollient foam. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:299-304.

8. Lebwohl MG, Medansky RS, Russo CL, et al. The comparative efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% lotion and metronidazole 0.75% gel in the treatment of rosacea. J Geriatr Dermatol. 1995;3:183-185.

9. Nally JB, Berson DS. Topical therapies for rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:23-26.

10. Pelle MT, Crawford GH, James WD. Rosacea II: therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:499-512.

11. Tarimci N, Sener S, Kilinç T. Topical sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur lotion. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22:301.

12. Breneman DL, Ariano MC. Successful treatment of acne vulgaris in women with a new topical sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur lotion. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:365-367.

13. Whelan ST. Sodium sulfacetamide for seborrheic dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:724.

14. Bendl BJ. Perioral dermatitis: etiology and treatment. Cutis. 1976;17:903-908.

15. Olansky S. Old drug—in a new system—revisited. Cutis. 1977;19:852-854.

16. Genvert GI, Cohen EJ, Donnenfeld ED, et al. Erythema multiforme after use of topical sulfacetamide. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:465-468.

17. Rubin Z. Ophthalmic sulfonamide-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:235-236.

18. Draelos ZD. The multifunctionality of 10% sodium sulfacetamide, 5% sulfur emollient foam in the treatment of inflammatory facial dermatoses. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:234-246.

19. Dubina MI, Fleischer AB. Interaction of topical sulfacetamide and topical dapsone with benzoyl peroxide. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1027-1029.

20. Sodium sulfacetamide – sulfacetamide sodium liquid. DailyMed Web site. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=0d92c55b-5b54-4f5d-8921-24e4e877ae50. Accessed June 17, 2015.

21. Spes CH, Angermann CE, Stempfle HU, et al. Sulfadiazine therapy for toxoplasmosis in heart transplant recipients decreases cyclosporine concentration. Clin Investig. 1992;70:752-754.

22. Hansen JM, Kampmann JP, Siersbaek-Nielsen K, et al. The effect of different sulfonamides on phenytoin metabolism in man. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1979;624:106-110.

23. Bradley JS, Sauberan JB. Antimicrobial agents. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1453-1483.

1. Akhavan A, Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:473-492.

2. Gupta AK, Nicol K. The use of sulfur in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:427-431.

3. Motaparthi K, Hsu S. Topical antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012:445-459.

4. Duemling WM. Sodium sulfacetamide in topical therapy. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:75-82.

5. Sodium sulfacetamide. Drugs.com Web site. http://drugs.com/pro/sodium-sulfacetamide.html. Revised December 2012. Accessed June 16, 2015.

6. Sauder DN, Miller R, Gratton D, et al. The treatment of rosacea: the safety and efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% lotion (Novacet) is demonstrated in a double-blind study. J Dermatol Treat. 1997;8:79-85.

7. Trumbore MW, Goldstein JA, Gurge RM. Treatment of papulopustular rosacea with sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% emollient foam. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:299-304.

8. Lebwohl MG, Medansky RS, Russo CL, et al. The comparative efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10%/sulfur 5% lotion and metronidazole 0.75% gel in the treatment of rosacea. J Geriatr Dermatol. 1995;3:183-185.

9. Nally JB, Berson DS. Topical therapies for rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:23-26.

10. Pelle MT, Crawford GH, James WD. Rosacea II: therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:499-512.

11. Tarimci N, Sener S, Kilinç T. Topical sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur lotion. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22:301.

12. Breneman DL, Ariano MC. Successful treatment of acne vulgaris in women with a new topical sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur lotion. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:365-367.

13. Whelan ST. Sodium sulfacetamide for seborrheic dermatitis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:724.

14. Bendl BJ. Perioral dermatitis: etiology and treatment. Cutis. 1976;17:903-908.

15. Olansky S. Old drug—in a new system—revisited. Cutis. 1977;19:852-854.

16. Genvert GI, Cohen EJ, Donnenfeld ED, et al. Erythema multiforme after use of topical sulfacetamide. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:465-468.

17. Rubin Z. Ophthalmic sulfonamide-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:235-236.

18. Draelos ZD. The multifunctionality of 10% sodium sulfacetamide, 5% sulfur emollient foam in the treatment of inflammatory facial dermatoses. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:234-246.

19. Dubina MI, Fleischer AB. Interaction of topical sulfacetamide and topical dapsone with benzoyl peroxide. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1027-1029.

20. Sodium sulfacetamide – sulfacetamide sodium liquid. DailyMed Web site. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=0d92c55b-5b54-4f5d-8921-24e4e877ae50. Accessed June 17, 2015.

21. Spes CH, Angermann CE, Stempfle HU, et al. Sulfadiazine therapy for toxoplasmosis in heart transplant recipients decreases cyclosporine concentration. Clin Investig. 1992;70:752-754.

22. Hansen JM, Kampmann JP, Siersbaek-Nielsen K, et al. The effect of different sulfonamides on phenytoin metabolism in man. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1979;624:106-110.

23. Bradley JS, Sauberan JB. Antimicrobial agents. In: Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1453-1483.

Practice Points

- Sodium sulfacetamide is a useful agent in the management of papulopustular rosacea, acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and perioral dermatitis.

- Adverse effects are rare and generally are limited to dryness, erythema, pruritus, and discomfort.

Onychomatricoma: An Often Misdiagnosed Tumor of the Nails

Changes in the appearance of the nail apparatus can be produced by a variety of conditions. Onychomatricoma is an unusual benign tumor with specific clinical characteristics that was first described more than 2 decades ago.1 It is often and easily misdiagnosed because the condition rarely has been described. We report a case of onychomatricoma in a 54-year-old Colombian man who presented with a deformity of the nail plate on the right index finger that corresponded with the classic description of onychomatricoma. We emphasize the importance of reporting such lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Colombian man presented with nail dystrophy involving the right index finger of 2 years’ duration. He did not recall any trauma prior to the onset of the nail abnormalities. Several topical treatments had previously been ineffective. Physical examination revealed a longitudinally banded thickening of the lateral half of the nail plate on the right index finger with yellowish brown discoloration, transverse overcurvature of the nail, longitudinal white lines, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 1). Direct microscopy and fungal culture were performed to diagnose or rule out onychomycosis.

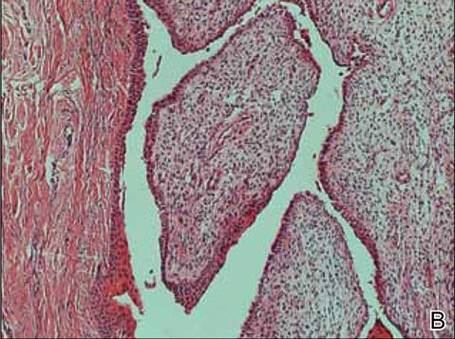

A clinical diagnosis of onychomatricoma was made, and the lesion was surgically removed and sent for histopathologic study (Figure 2). The radial half of the nail plate was avulsed, and the proximal part of the removed nail plate contained a large, firmly attached, filamentous tumor arising from the nail matrix (Figure 3) with multiple fine filiform projections (Figure 4). The nail bed was cleaned with a curette to remove any debris, the ulnar half of the nail plate and nail bed was left in place, and the radial border was reconstructed. Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis (Figure 5). No recurrences of the tumor were seen 36 months following surgery.

|

|

Comment

Since the original report of this tumor,1 fewer than 10 cases of onychomatricoma have been reported in Latin America,2-5 with no more than 80 cases reported worldwide.6 Clinicians and academicians are becoming interested in the topic, which will result in better recognition and more reports in the literature.

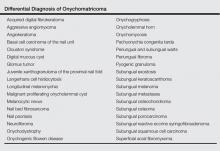

The clinical differential diagnosis of onycho-matricoma is extensive,7,8 but onychomatricoma has characteristic clinical and histopathologic features that allow its separation from other nail disorders and subungual tumors (Table).9 There are 4 cardinal clinical signs that suggest a diagnosis of onychomatricoma: (1) banded or diffuse thickening of the nail plate of variable widths; (2) yellowish discoloration of the involved nail plate, often showing fine splinter hemorrhages in the proximal nail portion; (3) transverse overcurvature of the nail; and (4) exposure of a filamentous tufted tumor emerging from the matrix in a funnel-shaped nail by avulsion.1

|

Histologic findings of onychomatricoma typically demonstrate a fibroepithelial tumor with a biphasic growth pattern mimicking normal nail matrix histology, including a proximal zone, which corresponds to the base of the fibroepithelial tumor, and a distal zone, which is composed of multiple epithelial digitations that extend into the small cavities present in the attached nail.10-12 Nevertheless, the anatomic tumor location, the often fragmented aspect of the tissue specimen, and the choice of the section planes may change the typical histologic features seen in onychomatricoma.13 Stromal prominence, cellularity, and atypia may vary in individual cases.10-12

The etiology of onychomatricoma is not yet known. Although it has been suggested that onychomatricoma could be an epithelial and connective tissue hamartoma simulating the nail matrix structure,1,10 the more recent concept of an epithelial onychogenic tumor with onychogenic mesenchyme will help to clarify its etiology because new histopathologic and immunohistochemical features suggest a neoplastic nature.14 On the other hand, predisposing factors such as trauma to the nail plate and onychomycosis may play a role,7 as the thumbs, index fingers, and great toes are more susceptible to onychomycosis and accidental trauma.

Conclusion

Our patient fulfilled the criteria of onychomatricoma.1 Onychomatricoma should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of subungual or periungual tumors to avoid misdiagnosis and erroneous treatments.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma: filamentous tufted tumor in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Estrada-Chavez G, Vega-Memije ME, Toussaint-Caire S, et al. Giant onychomatricoma: report of two cases with rare clinical presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46: 634-636.

3. Soto R, Wortsman X, Corredoira Y. Onychomatricoma: clinical and sonographic findings. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1461-1462.

4. Tavares GT, Chiacchio NG, Chiacchio ND, et al. Onychomatricoma: a tumor unknown to dermatologists. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:265-267.

5. Fernández-Sánchez M, Saeb-Lima M, Charli-Joseph Y, et al. Onychomatricoma: an infrequent nail tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:382-383.

6. Tavares G, Di-Chiacchio N, Di-Santis E, et al. Onycho-matricoma: epidemiological and clinical findings in a large series of 30 cases [published online ahead of print May 12, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13900.

7. Rashid RM, Swan J. Onychomatricoma: benign sporadic nail lesion or much more? Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:4.

8. Goutos I, Furniss D, Smith GD. Onychomatricoma: an unusual case of ungual pathology. case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:54-57.

9. Fraga GR, Patterson JW, McHargue CA. Onychomatricoma: report of a case and its comparison with fibrokeratoma of the nailbed. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:36-40.

10. Perrin C, Goettmann S, Baran R. Onychomatricoma: clinical and histopathologic findings in 12 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:560-564.

11. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):S66-S69.

12. Perrin C, Baran R, Pisani A, et al. The onychomatricoma: additional histologic criteria and immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:199-203.

13. Perrin C, Baran R, Balaguer T, et al. Onychomatricoma: new clinical and histological features. a review of 19 tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:1-8.

14. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

Changes in the appearance of the nail apparatus can be produced by a variety of conditions. Onychomatricoma is an unusual benign tumor with specific clinical characteristics that was first described more than 2 decades ago.1 It is often and easily misdiagnosed because the condition rarely has been described. We report a case of onychomatricoma in a 54-year-old Colombian man who presented with a deformity of the nail plate on the right index finger that corresponded with the classic description of onychomatricoma. We emphasize the importance of reporting such lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Colombian man presented with nail dystrophy involving the right index finger of 2 years’ duration. He did not recall any trauma prior to the onset of the nail abnormalities. Several topical treatments had previously been ineffective. Physical examination revealed a longitudinally banded thickening of the lateral half of the nail plate on the right index finger with yellowish brown discoloration, transverse overcurvature of the nail, longitudinal white lines, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 1). Direct microscopy and fungal culture were performed to diagnose or rule out onychomycosis.

A clinical diagnosis of onychomatricoma was made, and the lesion was surgically removed and sent for histopathologic study (Figure 2). The radial half of the nail plate was avulsed, and the proximal part of the removed nail plate contained a large, firmly attached, filamentous tumor arising from the nail matrix (Figure 3) with multiple fine filiform projections (Figure 4). The nail bed was cleaned with a curette to remove any debris, the ulnar half of the nail plate and nail bed was left in place, and the radial border was reconstructed. Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis (Figure 5). No recurrences of the tumor were seen 36 months following surgery.

|

|

Comment

Since the original report of this tumor,1 fewer than 10 cases of onychomatricoma have been reported in Latin America,2-5 with no more than 80 cases reported worldwide.6 Clinicians and academicians are becoming interested in the topic, which will result in better recognition and more reports in the literature.

The clinical differential diagnosis of onycho-matricoma is extensive,7,8 but onychomatricoma has characteristic clinical and histopathologic features that allow its separation from other nail disorders and subungual tumors (Table).9 There are 4 cardinal clinical signs that suggest a diagnosis of onychomatricoma: (1) banded or diffuse thickening of the nail plate of variable widths; (2) yellowish discoloration of the involved nail plate, often showing fine splinter hemorrhages in the proximal nail portion; (3) transverse overcurvature of the nail; and (4) exposure of a filamentous tufted tumor emerging from the matrix in a funnel-shaped nail by avulsion.1

|

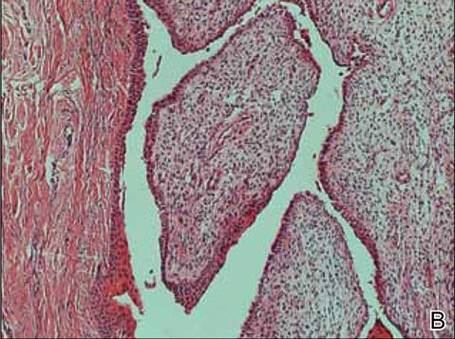

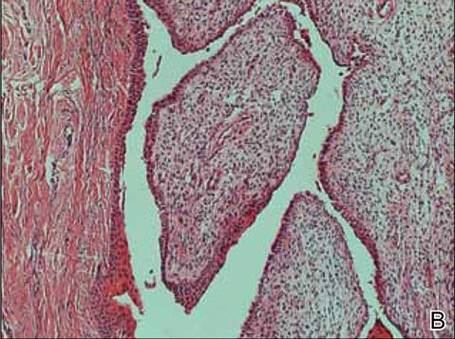

Histologic findings of onychomatricoma typically demonstrate a fibroepithelial tumor with a biphasic growth pattern mimicking normal nail matrix histology, including a proximal zone, which corresponds to the base of the fibroepithelial tumor, and a distal zone, which is composed of multiple epithelial digitations that extend into the small cavities present in the attached nail.10-12 Nevertheless, the anatomic tumor location, the often fragmented aspect of the tissue specimen, and the choice of the section planes may change the typical histologic features seen in onychomatricoma.13 Stromal prominence, cellularity, and atypia may vary in individual cases.10-12

The etiology of onychomatricoma is not yet known. Although it has been suggested that onychomatricoma could be an epithelial and connective tissue hamartoma simulating the nail matrix structure,1,10 the more recent concept of an epithelial onychogenic tumor with onychogenic mesenchyme will help to clarify its etiology because new histopathologic and immunohistochemical features suggest a neoplastic nature.14 On the other hand, predisposing factors such as trauma to the nail plate and onychomycosis may play a role,7 as the thumbs, index fingers, and great toes are more susceptible to onychomycosis and accidental trauma.

Conclusion

Our patient fulfilled the criteria of onychomatricoma.1 Onychomatricoma should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of subungual or periungual tumors to avoid misdiagnosis and erroneous treatments.

Changes in the appearance of the nail apparatus can be produced by a variety of conditions. Onychomatricoma is an unusual benign tumor with specific clinical characteristics that was first described more than 2 decades ago.1 It is often and easily misdiagnosed because the condition rarely has been described. We report a case of onychomatricoma in a 54-year-old Colombian man who presented with a deformity of the nail plate on the right index finger that corresponded with the classic description of onychomatricoma. We emphasize the importance of reporting such lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Colombian man presented with nail dystrophy involving the right index finger of 2 years’ duration. He did not recall any trauma prior to the onset of the nail abnormalities. Several topical treatments had previously been ineffective. Physical examination revealed a longitudinally banded thickening of the lateral half of the nail plate on the right index finger with yellowish brown discoloration, transverse overcurvature of the nail, longitudinal white lines, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 1). Direct microscopy and fungal culture were performed to diagnose or rule out onychomycosis.

A clinical diagnosis of onychomatricoma was made, and the lesion was surgically removed and sent for histopathologic study (Figure 2). The radial half of the nail plate was avulsed, and the proximal part of the removed nail plate contained a large, firmly attached, filamentous tumor arising from the nail matrix (Figure 3) with multiple fine filiform projections (Figure 4). The nail bed was cleaned with a curette to remove any debris, the ulnar half of the nail plate and nail bed was left in place, and the radial border was reconstructed. Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis (Figure 5). No recurrences of the tumor were seen 36 months following surgery.

|

|

Comment

Since the original report of this tumor,1 fewer than 10 cases of onychomatricoma have been reported in Latin America,2-5 with no more than 80 cases reported worldwide.6 Clinicians and academicians are becoming interested in the topic, which will result in better recognition and more reports in the literature.

The clinical differential diagnosis of onycho-matricoma is extensive,7,8 but onychomatricoma has characteristic clinical and histopathologic features that allow its separation from other nail disorders and subungual tumors (Table).9 There are 4 cardinal clinical signs that suggest a diagnosis of onychomatricoma: (1) banded or diffuse thickening of the nail plate of variable widths; (2) yellowish discoloration of the involved nail plate, often showing fine splinter hemorrhages in the proximal nail portion; (3) transverse overcurvature of the nail; and (4) exposure of a filamentous tufted tumor emerging from the matrix in a funnel-shaped nail by avulsion.1

|

Histologic findings of onychomatricoma typically demonstrate a fibroepithelial tumor with a biphasic growth pattern mimicking normal nail matrix histology, including a proximal zone, which corresponds to the base of the fibroepithelial tumor, and a distal zone, which is composed of multiple epithelial digitations that extend into the small cavities present in the attached nail.10-12 Nevertheless, the anatomic tumor location, the often fragmented aspect of the tissue specimen, and the choice of the section planes may change the typical histologic features seen in onychomatricoma.13 Stromal prominence, cellularity, and atypia may vary in individual cases.10-12

The etiology of onychomatricoma is not yet known. Although it has been suggested that onychomatricoma could be an epithelial and connective tissue hamartoma simulating the nail matrix structure,1,10 the more recent concept of an epithelial onychogenic tumor with onychogenic mesenchyme will help to clarify its etiology because new histopathologic and immunohistochemical features suggest a neoplastic nature.14 On the other hand, predisposing factors such as trauma to the nail plate and onychomycosis may play a role,7 as the thumbs, index fingers, and great toes are more susceptible to onychomycosis and accidental trauma.

Conclusion

Our patient fulfilled the criteria of onychomatricoma.1 Onychomatricoma should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of subungual or periungual tumors to avoid misdiagnosis and erroneous treatments.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma: filamentous tufted tumor in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Estrada-Chavez G, Vega-Memije ME, Toussaint-Caire S, et al. Giant onychomatricoma: report of two cases with rare clinical presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46: 634-636.

3. Soto R, Wortsman X, Corredoira Y. Onychomatricoma: clinical and sonographic findings. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1461-1462.

4. Tavares GT, Chiacchio NG, Chiacchio ND, et al. Onychomatricoma: a tumor unknown to dermatologists. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:265-267.

5. Fernández-Sánchez M, Saeb-Lima M, Charli-Joseph Y, et al. Onychomatricoma: an infrequent nail tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:382-383.

6. Tavares G, Di-Chiacchio N, Di-Santis E, et al. Onycho-matricoma: epidemiological and clinical findings in a large series of 30 cases [published online ahead of print May 12, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13900.

7. Rashid RM, Swan J. Onychomatricoma: benign sporadic nail lesion or much more? Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:4.

8. Goutos I, Furniss D, Smith GD. Onychomatricoma: an unusual case of ungual pathology. case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:54-57.

9. Fraga GR, Patterson JW, McHargue CA. Onychomatricoma: report of a case and its comparison with fibrokeratoma of the nailbed. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:36-40.

10. Perrin C, Goettmann S, Baran R. Onychomatricoma: clinical and histopathologic findings in 12 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:560-564.

11. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):S66-S69.

12. Perrin C, Baran R, Pisani A, et al. The onychomatricoma: additional histologic criteria and immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:199-203.

13. Perrin C, Baran R, Balaguer T, et al. Onychomatricoma: new clinical and histological features. a review of 19 tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:1-8.

14. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma: filamentous tufted tumor in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Estrada-Chavez G, Vega-Memije ME, Toussaint-Caire S, et al. Giant onychomatricoma: report of two cases with rare clinical presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46: 634-636.

3. Soto R, Wortsman X, Corredoira Y. Onychomatricoma: clinical and sonographic findings. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1461-1462.

4. Tavares GT, Chiacchio NG, Chiacchio ND, et al. Onychomatricoma: a tumor unknown to dermatologists. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:265-267.

5. Fernández-Sánchez M, Saeb-Lima M, Charli-Joseph Y, et al. Onychomatricoma: an infrequent nail tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:382-383.

6. Tavares G, Di-Chiacchio N, Di-Santis E, et al. Onycho-matricoma: epidemiological and clinical findings in a large series of 30 cases [published online ahead of print May 12, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13900.

7. Rashid RM, Swan J. Onychomatricoma: benign sporadic nail lesion or much more? Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:4.

8. Goutos I, Furniss D, Smith GD. Onychomatricoma: an unusual case of ungual pathology. case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:54-57.

9. Fraga GR, Patterson JW, McHargue CA. Onychomatricoma: report of a case and its comparison with fibrokeratoma of the nailbed. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:36-40.

10. Perrin C, Goettmann S, Baran R. Onychomatricoma: clinical and histopathologic findings in 12 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:560-564.

11. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):S66-S69.

12. Perrin C, Baran R, Pisani A, et al. The onychomatricoma: additional histologic criteria and immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:199-203.

13. Perrin C, Baran R, Balaguer T, et al. Onychomatricoma: new clinical and histological features. a review of 19 tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:1-8.

14. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

Practice Points

- Onychomatricoma has been described mostly in white individuals, but it can occur in all races and ethnic groups.

- Onychomatricoma should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of subungual or periungual tumors.

- Treatment of onychomatricoma is complete surgical excision.

How to Teach the Potassium Hydroxide Preparation: A Disappearing Clinical Art Form

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations remain an important bedside test for prompt and accurate diagnosis of superficial fungal infections known as dermatophytoses. This tool has been used for at least 100 years, with early terminology referring to it as potash; for the last century, it has largely been a technique passed down as a skill from master technician to learning apprentice. The original pioneer of the KOH preparation remains a mystery.1

Variations on techniques for performing the KOH preparation exist, and tips and tricks on the use of this test are a hot topic among dermatologists.2 Although primary care and dermatology-specific publications espouse the importance of the KOH preparation,3,4 it has unfortunately been identified and labeled as one of the forgotten diagnostic tools.5

It is incumbent on dermatologists to educate medical students and residents using a simple and specific method to ensure that this simple and effective technique, with sensitivity reported between 87% and 91% depending on the expertise of the examiner,6 remains part of the clinical armamentarium. One concern in the instruction of large groups of students and clinicians is the ready accessibility or availability of viable skin samples. This article describes a method of collecting and storing skin samples that will allow educators to train large groups of students on performing KOH preparations without having to repeatedly seek skin samples or patients with superficial skin infections. A detailed description of the pedagogy used to teach the preparation and interpretation of KOH slides to a large group of students also is reviewed.

Specimen Collection

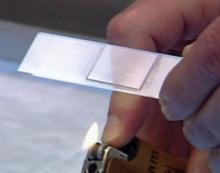

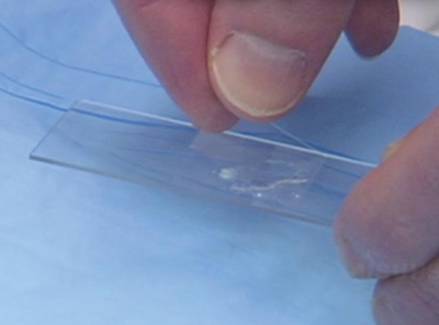

The first step in teaching the KOH preparation to a large group is the collection of a suitable number of skin scrapings from patients with a superficial fungal skin infection (eg, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor). A common technique for obtaining skin samples is to use a no. 15 scalpel blade (Figure 1) to scrape the scale of the lesion at its scaly border once the area is moistened with an alcohol pad or soap and water.7 The moisture from the alcohol pad allows the scale to stick to the no. 15 blade, facilitating collection. Once a suitable amount of scale is collected, it is placed on a glass microscope slide by smearing the scale from the blade onto the slide. This process has been modified to facilitate a larger quantity of specimen as follows: dermatophyte-infected plaques with scale are rubbed with the no. 15 blade and the free scale drops into a standard urine specimen cup. This process is repeated multiple times from different sites to capture the displaced scale with the dermatophyte. We have found that as long as the specimen cups are sealed tightly and stored in a relatively dry and cool environment (room temperature), the samples can be used to construct KOH teaching slides for at least 3 years. We have not used them beyond 3 years but suspect that they would continue to be viable after this time.

Preparation of Slides

Given that time for teaching often is limited, it is beneficial to fix many skin scrapings on a large number of glass slides prior to the session, which enables students to simply add KOH to the slides on the teaching day. To prepare the slides in advance, it is necessary to gather the following materials: a specimen cup with skin samples, glass slides, pickups or tweezers, a small pipette, a cup of water, protective gloves, and a pencil. After donning protective gloves, the pickups or tweezers are used to retrieve a few flakes of scale from the specimen cup and place them on the center of a glass slide. Using the pipette, 1 or 2 drops of water are added to the scale, and the slide is then allowed to dry. The slides are marked with the pencil to indicate the “up” side to prevent the students from applying KOH solution to the wrong side of the slide. The skin scale is fixed in place on the slide as the water evaporates and may be stored until needed for use in a standard slide box or folder.

Performing the KOH Preparation

On the day of teaching, it is helpful to engage the entire group of students with an introductory lecture on the purpose and use of the KOH preparation. Upon completion, students move to a workstation with all of the materials needed to prepare the slide. Additional items needed at this time are 10% KOH solution, coverslips, and a heating device (eg, lighter, Bunsen burner, match)(optional). Students are instructed to place 1 or 2 skin scales onto a glass slide or retrieve a slide with skin scales already fixed, and then add 1 drop of 10% KOH solution directly to the sample (Figure 2). Next, they should place a slide coverslip onto the KOH drop and skin sample using a side-to-side technique that will move the scale into a thin layer within the KOH solution and push away any excess solution to the periphery (Figure 3). Large amounts of excess KOH solution should be cleared away with a paper towel, lens paper, or tissue. The heat source can be used to gently heat the underside of the glass slide (Figure 4), but it often is sufficient to simply wait 3 to 5 minutes for the KOH solution to take effect. The heat accelerates the maceration of the scale and makes it easier to see the hyphae among the keratinocytes. Some physicians advocate the use of dimethyl sulfoxide in lieu of heating,8 but this solution may not be available in all primary care settings.

|

|

Microscopic Examination

Prior to examining the slides under the microscope, students may complete a self-guided tutorial (eg, digital or paper slide show) on the various features seen through the microscope that are indicative of dermatophytes, including branching hyphae and yeast buds. They also should be educated about the common appearance of artifacts that may resemble hyphae. Once the students have completed the tutorial, they may proceed to microscopic examination.

While the students are viewing their slides under the microscope, we find it helpful to have at least 1 experienced faculty member for every group of 10 students. This instructor should encourage the students to lower the microscope condenser all the way to facilitate better observation. Students should start with low power (×4 or red band) and scan for areas that are rich in skin scale. Once a collection of scale is found, the student can switch to higher power (×10 or yellow band) and start scanning for hyphae. Students should be reminded to search for filamentous and branching tubes that are refractile. The term refractile may be confusing to some students, so we explain that shifting the focus up or down will show the hyphae to change in brightness and may reveal a greenish tint. Another helpful indicator to point out is the feature that hyphae will cross the border of epidermal skin cells, whereas artifacts will not (Figure 5). Once the students have identified evidence of a dermatophyte infection, they must call the instructor to their station to verify the presence of hyphae or yeast buds, which helps confirm their understanding of the procedure. Once the student accurately identifies these items, the session is complete.

Comment

The use of a KOH preparation is a fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective way to diagnose superficial fungal infections; however, because of insufficient familiarity with this tool, the technique often is replaced by initiation of empiric antifungal therapy in patients with suspected dermatophytosis. This empiric treatment has the potential to delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment (eg, in a patient with nummular dermatitis, which can clinically mimic tinea corporis). One way to encourage the use of the KOH preparation in the primary care and dermatologic setting is to educate large groups of next-generation physicians while in medical training. This article describes a teaching technique that allows for long-term storage of positive skin samples and a detailed description of the pedagogy used to train and educate a large group of students in a relatively short period of time.

All KOH preparations fall under the US federal government’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and require proficiency testing.9 Although the teaching method presented here is designed for teaching medical students, it may be utilized to educate or refamiliarize experienced physicians with the procedure in an effort to improve proficiency in point-of-care testing programs used in many health care systems to comply with the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments. Future analyses could assess whether the method described here improves provider performance on such proficiency measures and whether it ultimately helps ensure quality patient care.

1. Dasgupta T, Sahu J. Origins of the KOH technique. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:238-242.

2. Stone S. Editor’s commentary. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:241-242.

3. Monroe JR. The diagnostic value of a KOH. JAAPA. 2001;4:50-51.

4. Hainer BL. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;1:101-109.

5. Ponka D, Baddar F. Microscopic potassium hydroxide preparation. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:57.

6. Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;4:620-626.

7. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.

9. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index.html?redirect=/clia/. Updated June 6, 2015. Accessed July 21, 2015.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations remain an important bedside test for prompt and accurate diagnosis of superficial fungal infections known as dermatophytoses. This tool has been used for at least 100 years, with early terminology referring to it as potash; for the last century, it has largely been a technique passed down as a skill from master technician to learning apprentice. The original pioneer of the KOH preparation remains a mystery.1

Variations on techniques for performing the KOH preparation exist, and tips and tricks on the use of this test are a hot topic among dermatologists.2 Although primary care and dermatology-specific publications espouse the importance of the KOH preparation,3,4 it has unfortunately been identified and labeled as one of the forgotten diagnostic tools.5

It is incumbent on dermatologists to educate medical students and residents using a simple and specific method to ensure that this simple and effective technique, with sensitivity reported between 87% and 91% depending on the expertise of the examiner,6 remains part of the clinical armamentarium. One concern in the instruction of large groups of students and clinicians is the ready accessibility or availability of viable skin samples. This article describes a method of collecting and storing skin samples that will allow educators to train large groups of students on performing KOH preparations without having to repeatedly seek skin samples or patients with superficial skin infections. A detailed description of the pedagogy used to teach the preparation and interpretation of KOH slides to a large group of students also is reviewed.

Specimen Collection

The first step in teaching the KOH preparation to a large group is the collection of a suitable number of skin scrapings from patients with a superficial fungal skin infection (eg, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor). A common technique for obtaining skin samples is to use a no. 15 scalpel blade (Figure 1) to scrape the scale of the lesion at its scaly border once the area is moistened with an alcohol pad or soap and water.7 The moisture from the alcohol pad allows the scale to stick to the no. 15 blade, facilitating collection. Once a suitable amount of scale is collected, it is placed on a glass microscope slide by smearing the scale from the blade onto the slide. This process has been modified to facilitate a larger quantity of specimen as follows: dermatophyte-infected plaques with scale are rubbed with the no. 15 blade and the free scale drops into a standard urine specimen cup. This process is repeated multiple times from different sites to capture the displaced scale with the dermatophyte. We have found that as long as the specimen cups are sealed tightly and stored in a relatively dry and cool environment (room temperature), the samples can be used to construct KOH teaching slides for at least 3 years. We have not used them beyond 3 years but suspect that they would continue to be viable after this time.

Preparation of Slides

Given that time for teaching often is limited, it is beneficial to fix many skin scrapings on a large number of glass slides prior to the session, which enables students to simply add KOH to the slides on the teaching day. To prepare the slides in advance, it is necessary to gather the following materials: a specimen cup with skin samples, glass slides, pickups or tweezers, a small pipette, a cup of water, protective gloves, and a pencil. After donning protective gloves, the pickups or tweezers are used to retrieve a few flakes of scale from the specimen cup and place them on the center of a glass slide. Using the pipette, 1 or 2 drops of water are added to the scale, and the slide is then allowed to dry. The slides are marked with the pencil to indicate the “up” side to prevent the students from applying KOH solution to the wrong side of the slide. The skin scale is fixed in place on the slide as the water evaporates and may be stored until needed for use in a standard slide box or folder.

Performing the KOH Preparation

On the day of teaching, it is helpful to engage the entire group of students with an introductory lecture on the purpose and use of the KOH preparation. Upon completion, students move to a workstation with all of the materials needed to prepare the slide. Additional items needed at this time are 10% KOH solution, coverslips, and a heating device (eg, lighter, Bunsen burner, match)(optional). Students are instructed to place 1 or 2 skin scales onto a glass slide or retrieve a slide with skin scales already fixed, and then add 1 drop of 10% KOH solution directly to the sample (Figure 2). Next, they should place a slide coverslip onto the KOH drop and skin sample using a side-to-side technique that will move the scale into a thin layer within the KOH solution and push away any excess solution to the periphery (Figure 3). Large amounts of excess KOH solution should be cleared away with a paper towel, lens paper, or tissue. The heat source can be used to gently heat the underside of the glass slide (Figure 4), but it often is sufficient to simply wait 3 to 5 minutes for the KOH solution to take effect. The heat accelerates the maceration of the scale and makes it easier to see the hyphae among the keratinocytes. Some physicians advocate the use of dimethyl sulfoxide in lieu of heating,8 but this solution may not be available in all primary care settings.

|

|

Microscopic Examination

Prior to examining the slides under the microscope, students may complete a self-guided tutorial (eg, digital or paper slide show) on the various features seen through the microscope that are indicative of dermatophytes, including branching hyphae and yeast buds. They also should be educated about the common appearance of artifacts that may resemble hyphae. Once the students have completed the tutorial, they may proceed to microscopic examination.

While the students are viewing their slides under the microscope, we find it helpful to have at least 1 experienced faculty member for every group of 10 students. This instructor should encourage the students to lower the microscope condenser all the way to facilitate better observation. Students should start with low power (×4 or red band) and scan for areas that are rich in skin scale. Once a collection of scale is found, the student can switch to higher power (×10 or yellow band) and start scanning for hyphae. Students should be reminded to search for filamentous and branching tubes that are refractile. The term refractile may be confusing to some students, so we explain that shifting the focus up or down will show the hyphae to change in brightness and may reveal a greenish tint. Another helpful indicator to point out is the feature that hyphae will cross the border of epidermal skin cells, whereas artifacts will not (Figure 5). Once the students have identified evidence of a dermatophyte infection, they must call the instructor to their station to verify the presence of hyphae or yeast buds, which helps confirm their understanding of the procedure. Once the student accurately identifies these items, the session is complete.

Comment

The use of a KOH preparation is a fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective way to diagnose superficial fungal infections; however, because of insufficient familiarity with this tool, the technique often is replaced by initiation of empiric antifungal therapy in patients with suspected dermatophytosis. This empiric treatment has the potential to delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment (eg, in a patient with nummular dermatitis, which can clinically mimic tinea corporis). One way to encourage the use of the KOH preparation in the primary care and dermatologic setting is to educate large groups of next-generation physicians while in medical training. This article describes a teaching technique that allows for long-term storage of positive skin samples and a detailed description of the pedagogy used to train and educate a large group of students in a relatively short period of time.

All KOH preparations fall under the US federal government’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and require proficiency testing.9 Although the teaching method presented here is designed for teaching medical students, it may be utilized to educate or refamiliarize experienced physicians with the procedure in an effort to improve proficiency in point-of-care testing programs used in many health care systems to comply with the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments. Future analyses could assess whether the method described here improves provider performance on such proficiency measures and whether it ultimately helps ensure quality patient care.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations remain an important bedside test for prompt and accurate diagnosis of superficial fungal infections known as dermatophytoses. This tool has been used for at least 100 years, with early terminology referring to it as potash; for the last century, it has largely been a technique passed down as a skill from master technician to learning apprentice. The original pioneer of the KOH preparation remains a mystery.1

Variations on techniques for performing the KOH preparation exist, and tips and tricks on the use of this test are a hot topic among dermatologists.2 Although primary care and dermatology-specific publications espouse the importance of the KOH preparation,3,4 it has unfortunately been identified and labeled as one of the forgotten diagnostic tools.5

It is incumbent on dermatologists to educate medical students and residents using a simple and specific method to ensure that this simple and effective technique, with sensitivity reported between 87% and 91% depending on the expertise of the examiner,6 remains part of the clinical armamentarium. One concern in the instruction of large groups of students and clinicians is the ready accessibility or availability of viable skin samples. This article describes a method of collecting and storing skin samples that will allow educators to train large groups of students on performing KOH preparations without having to repeatedly seek skin samples or patients with superficial skin infections. A detailed description of the pedagogy used to teach the preparation and interpretation of KOH slides to a large group of students also is reviewed.

Specimen Collection

The first step in teaching the KOH preparation to a large group is the collection of a suitable number of skin scrapings from patients with a superficial fungal skin infection (eg, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor). A common technique for obtaining skin samples is to use a no. 15 scalpel blade (Figure 1) to scrape the scale of the lesion at its scaly border once the area is moistened with an alcohol pad or soap and water.7 The moisture from the alcohol pad allows the scale to stick to the no. 15 blade, facilitating collection. Once a suitable amount of scale is collected, it is placed on a glass microscope slide by smearing the scale from the blade onto the slide. This process has been modified to facilitate a larger quantity of specimen as follows: dermatophyte-infected plaques with scale are rubbed with the no. 15 blade and the free scale drops into a standard urine specimen cup. This process is repeated multiple times from different sites to capture the displaced scale with the dermatophyte. We have found that as long as the specimen cups are sealed tightly and stored in a relatively dry and cool environment (room temperature), the samples can be used to construct KOH teaching slides for at least 3 years. We have not used them beyond 3 years but suspect that they would continue to be viable after this time.

Preparation of Slides

Given that time for teaching often is limited, it is beneficial to fix many skin scrapings on a large number of glass slides prior to the session, which enables students to simply add KOH to the slides on the teaching day. To prepare the slides in advance, it is necessary to gather the following materials: a specimen cup with skin samples, glass slides, pickups or tweezers, a small pipette, a cup of water, protective gloves, and a pencil. After donning protective gloves, the pickups or tweezers are used to retrieve a few flakes of scale from the specimen cup and place them on the center of a glass slide. Using the pipette, 1 or 2 drops of water are added to the scale, and the slide is then allowed to dry. The slides are marked with the pencil to indicate the “up” side to prevent the students from applying KOH solution to the wrong side of the slide. The skin scale is fixed in place on the slide as the water evaporates and may be stored until needed for use in a standard slide box or folder.

Performing the KOH Preparation

On the day of teaching, it is helpful to engage the entire group of students with an introductory lecture on the purpose and use of the KOH preparation. Upon completion, students move to a workstation with all of the materials needed to prepare the slide. Additional items needed at this time are 10% KOH solution, coverslips, and a heating device (eg, lighter, Bunsen burner, match)(optional). Students are instructed to place 1 or 2 skin scales onto a glass slide or retrieve a slide with skin scales already fixed, and then add 1 drop of 10% KOH solution directly to the sample (Figure 2). Next, they should place a slide coverslip onto the KOH drop and skin sample using a side-to-side technique that will move the scale into a thin layer within the KOH solution and push away any excess solution to the periphery (Figure 3). Large amounts of excess KOH solution should be cleared away with a paper towel, lens paper, or tissue. The heat source can be used to gently heat the underside of the glass slide (Figure 4), but it often is sufficient to simply wait 3 to 5 minutes for the KOH solution to take effect. The heat accelerates the maceration of the scale and makes it easier to see the hyphae among the keratinocytes. Some physicians advocate the use of dimethyl sulfoxide in lieu of heating,8 but this solution may not be available in all primary care settings.

|

|

Microscopic Examination

Prior to examining the slides under the microscope, students may complete a self-guided tutorial (eg, digital or paper slide show) on the various features seen through the microscope that are indicative of dermatophytes, including branching hyphae and yeast buds. They also should be educated about the common appearance of artifacts that may resemble hyphae. Once the students have completed the tutorial, they may proceed to microscopic examination.

While the students are viewing their slides under the microscope, we find it helpful to have at least 1 experienced faculty member for every group of 10 students. This instructor should encourage the students to lower the microscope condenser all the way to facilitate better observation. Students should start with low power (×4 or red band) and scan for areas that are rich in skin scale. Once a collection of scale is found, the student can switch to higher power (×10 or yellow band) and start scanning for hyphae. Students should be reminded to search for filamentous and branching tubes that are refractile. The term refractile may be confusing to some students, so we explain that shifting the focus up or down will show the hyphae to change in brightness and may reveal a greenish tint. Another helpful indicator to point out is the feature that hyphae will cross the border of epidermal skin cells, whereas artifacts will not (Figure 5). Once the students have identified evidence of a dermatophyte infection, they must call the instructor to their station to verify the presence of hyphae or yeast buds, which helps confirm their understanding of the procedure. Once the student accurately identifies these items, the session is complete.

Comment

The use of a KOH preparation is a fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective way to diagnose superficial fungal infections; however, because of insufficient familiarity with this tool, the technique often is replaced by initiation of empiric antifungal therapy in patients with suspected dermatophytosis. This empiric treatment has the potential to delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment (eg, in a patient with nummular dermatitis, which can clinically mimic tinea corporis). One way to encourage the use of the KOH preparation in the primary care and dermatologic setting is to educate large groups of next-generation physicians while in medical training. This article describes a teaching technique that allows for long-term storage of positive skin samples and a detailed description of the pedagogy used to train and educate a large group of students in a relatively short period of time.

All KOH preparations fall under the US federal government’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and require proficiency testing.9 Although the teaching method presented here is designed for teaching medical students, it may be utilized to educate or refamiliarize experienced physicians with the procedure in an effort to improve proficiency in point-of-care testing programs used in many health care systems to comply with the Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments. Future analyses could assess whether the method described here improves provider performance on such proficiency measures and whether it ultimately helps ensure quality patient care.

1. Dasgupta T, Sahu J. Origins of the KOH technique. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:238-242.

2. Stone S. Editor’s commentary. Clin Dermatol. 2012;2:241-242.

3. Monroe JR. The diagnostic value of a KOH. JAAPA. 2001;4:50-51.

4. Hainer BL. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician. 2003;1:101-109.

5. Ponka D, Baddar F. Microscopic potassium hydroxide preparation. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:57.

6. Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;4:620-626.