User login

Make the Diagnosis - August 2015

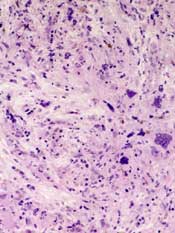

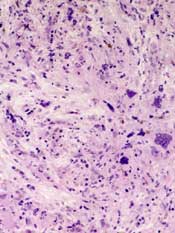

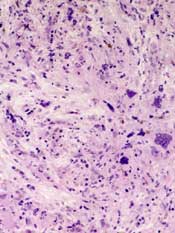

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Andrew R. Styperek, Houston Methodist Hospital and Dr. Leonard H. Goldberg of DermSurgery Associates, both in Houston. Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD in Aventura, Fla. To submit your case for possible publication, send an e-mail to [email protected]. A 27-year-old white female was admitted to the hospital with fever and shortness of breath. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of a long history of chronic skin itchiness and eczema, which had never resolved despite topical therapy. The patient denied any skeletal, tooth, or lung abnormalities. Her past medical history was significant for chronic cytomegalovirus infection of the right eye, resulting in extirpation of the orbit. She also had a history of eczema herpeticum. On physical exam, she had a patch of gauze over her right orbit, significant soft tissue loss of the nose, and numerous diffuse pink/red eczematous plaques over her arms, trunk, legs, and face. Of note, she also had multiple umbilicated and verrucous papules scattered over her body.

Team reports phase 3 results with abandoned MPN drug

Researchers have reported results of the phase 3 JAKARTA trial, in which they evaluated the selective JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib in patients with myelofibrosis (MF).

Fedratinib was being developed as a treatment for myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), but Sanofi Oncology stopped clinical development of the drug in 2013, after it was linked to a neurological condition known as Wernicke encephalopathy.

There were 4 confirmed cases of Wernicke encephalopathy in the JAKARTA trial, in addition to other adverse events (AEs). However, fedratinib also lessened the severity of MF symptoms in about 35% to 40% of patients.

These results have been published in JAMA Oncology alongside an invited commentary. The study was sponsored by Sanofi.

Treatment and response

The study enrolled 289 adult patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, or post-essential thrombocythemia MF. Patients were randomized to receive fedratinib at 400 mg once a day, fedratinib at 500 mg once a day, or placebo for at least 6 consecutive, 4-week cycles.

The study’s primary endpoint was spleen response, or a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume from baseline (determined by MRI or CT) at week 24 and confirmed 4 weeks later.

Thirty-six percent (35/96) of patients in the 400 mg arm and 40% (39/97) in the 500 mg arm achieved the primary endpoint, compared to 1% (1/96) of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The main secondary endpoint was symptom response, or a 50% or greater reduction in total symptom score (assessed using the modified Myelofibrosis Symptom Assessment Form).

At week 24, symptom response rates were 36% (33/91) in the 400 mg arm, 34% (31/91) in the 500 mg arm, and 7% (6/85) in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

Safety data

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 100% of patients in the 400 mg arm, 98% in the 500 mg arm, and 94% in the placebo arm. Serious AEs occurred in 27%, 31%, and 23%, respectively. AEs leading to discontinuation occurred in 14%, 25%, and 8%, respectively.

Infections occurred in 42% of patients in the 400 mg arm, 39% of patients in the 500 mg arm, and 27% of patients of patients in the placebo arm.

Nonhematologic AEs occurring in at least 10% of patients in any group were diarrhea (66%, 56%, and 16%, respectively), vomiting (42%, 55%, and 5%, respectively), nausea (64%, 51%, and 15%, respectively), constipation (10%, 18%, and 7%, respectively), asthenia (9%, 16%, and 6%, respectively), abdominal pain (15%, 12%, and 16%, respectively), fatigue (16%, 10%, and 10%, respectively), dyspnea (8%, 10%, and 6%, respectively), and weight loss (4%, 10%, and 5%, respectively).

Hematologic AEs occurring in at least 10% of patients in any group were anemia (99%, 98%, and 91%, respectively), thrombocytopenia (63%, 57%, and 51%, respectively), lymphopenia (57%, 66%, and 54%, respectively), leukopenia (47%, 53%, and 19%, respectively), and neutropenia (28%, 44%, and 15%, respectively).

One patient in each fedratinib arm and 2 in the placebo arm transformed to acute myeloid leukemia.

There were 24 deaths during the first 24 weeks of the study—4 in the 400 mg arm, 10 in the 500 mg arm, and 10 in the placebo arm. Nine of the deaths were attributed to AEs—1, 4, and 4, respectively.

Wernicke encephalopathy

There were 4 cases of Wernicke encephalopathy, all in women who received fedratinib at 500 mg. All of these cases were confirmed by an independent expert safety panel, 3 on the basis of clinical features and MRI results, and 1 on the basis of clinical symptoms alone.

The patients developed symptoms 6 weeks to 44 weeks after beginning fedratinib treatment, and all discontinued treatment permanently.

Cognitive symptoms manifested in the context of persistent vomiting, malnutrition, and cachexia in 1 patient, vomiting and hyponatremia in 1 patient, and renal failure with mild hyponatremia in 1 patient.

All of the patients received intravenous thiamine and showed responses to the treatment, but all had persistent cognitive defects at last follow-up. ![]()

Researchers have reported results of the phase 3 JAKARTA trial, in which they evaluated the selective JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib in patients with myelofibrosis (MF).

Fedratinib was being developed as a treatment for myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), but Sanofi Oncology stopped clinical development of the drug in 2013, after it was linked to a neurological condition known as Wernicke encephalopathy.

There were 4 confirmed cases of Wernicke encephalopathy in the JAKARTA trial, in addition to other adverse events (AEs). However, fedratinib also lessened the severity of MF symptoms in about 35% to 40% of patients.

These results have been published in JAMA Oncology alongside an invited commentary. The study was sponsored by Sanofi.

Treatment and response

The study enrolled 289 adult patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, or post-essential thrombocythemia MF. Patients were randomized to receive fedratinib at 400 mg once a day, fedratinib at 500 mg once a day, or placebo for at least 6 consecutive, 4-week cycles.

The study’s primary endpoint was spleen response, or a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume from baseline (determined by MRI or CT) at week 24 and confirmed 4 weeks later.

Thirty-six percent (35/96) of patients in the 400 mg arm and 40% (39/97) in the 500 mg arm achieved the primary endpoint, compared to 1% (1/96) of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The main secondary endpoint was symptom response, or a 50% or greater reduction in total symptom score (assessed using the modified Myelofibrosis Symptom Assessment Form).

At week 24, symptom response rates were 36% (33/91) in the 400 mg arm, 34% (31/91) in the 500 mg arm, and 7% (6/85) in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

Safety data

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 100% of patients in the 400 mg arm, 98% in the 500 mg arm, and 94% in the placebo arm. Serious AEs occurred in 27%, 31%, and 23%, respectively. AEs leading to discontinuation occurred in 14%, 25%, and 8%, respectively.

Infections occurred in 42% of patients in the 400 mg arm, 39% of patients in the 500 mg arm, and 27% of patients of patients in the placebo arm.

Nonhematologic AEs occurring in at least 10% of patients in any group were diarrhea (66%, 56%, and 16%, respectively), vomiting (42%, 55%, and 5%, respectively), nausea (64%, 51%, and 15%, respectively), constipation (10%, 18%, and 7%, respectively), asthenia (9%, 16%, and 6%, respectively), abdominal pain (15%, 12%, and 16%, respectively), fatigue (16%, 10%, and 10%, respectively), dyspnea (8%, 10%, and 6%, respectively), and weight loss (4%, 10%, and 5%, respectively).

Hematologic AEs occurring in at least 10% of patients in any group were anemia (99%, 98%, and 91%, respectively), thrombocytopenia (63%, 57%, and 51%, respectively), lymphopenia (57%, 66%, and 54%, respectively), leukopenia (47%, 53%, and 19%, respectively), and neutropenia (28%, 44%, and 15%, respectively).

One patient in each fedratinib arm and 2 in the placebo arm transformed to acute myeloid leukemia.

There were 24 deaths during the first 24 weeks of the study—4 in the 400 mg arm, 10 in the 500 mg arm, and 10 in the placebo arm. Nine of the deaths were attributed to AEs—1, 4, and 4, respectively.

Wernicke encephalopathy

There were 4 cases of Wernicke encephalopathy, all in women who received fedratinib at 500 mg. All of these cases were confirmed by an independent expert safety panel, 3 on the basis of clinical features and MRI results, and 1 on the basis of clinical symptoms alone.

The patients developed symptoms 6 weeks to 44 weeks after beginning fedratinib treatment, and all discontinued treatment permanently.

Cognitive symptoms manifested in the context of persistent vomiting, malnutrition, and cachexia in 1 patient, vomiting and hyponatremia in 1 patient, and renal failure with mild hyponatremia in 1 patient.

All of the patients received intravenous thiamine and showed responses to the treatment, but all had persistent cognitive defects at last follow-up. ![]()

Researchers have reported results of the phase 3 JAKARTA trial, in which they evaluated the selective JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib in patients with myelofibrosis (MF).

Fedratinib was being developed as a treatment for myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), but Sanofi Oncology stopped clinical development of the drug in 2013, after it was linked to a neurological condition known as Wernicke encephalopathy.

There were 4 confirmed cases of Wernicke encephalopathy in the JAKARTA trial, in addition to other adverse events (AEs). However, fedratinib also lessened the severity of MF symptoms in about 35% to 40% of patients.

These results have been published in JAMA Oncology alongside an invited commentary. The study was sponsored by Sanofi.

Treatment and response

The study enrolled 289 adult patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, or post-essential thrombocythemia MF. Patients were randomized to receive fedratinib at 400 mg once a day, fedratinib at 500 mg once a day, or placebo for at least 6 consecutive, 4-week cycles.

The study’s primary endpoint was spleen response, or a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume from baseline (determined by MRI or CT) at week 24 and confirmed 4 weeks later.

Thirty-six percent (35/96) of patients in the 400 mg arm and 40% (39/97) in the 500 mg arm achieved the primary endpoint, compared to 1% (1/96) of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The main secondary endpoint was symptom response, or a 50% or greater reduction in total symptom score (assessed using the modified Myelofibrosis Symptom Assessment Form).

At week 24, symptom response rates were 36% (33/91) in the 400 mg arm, 34% (31/91) in the 500 mg arm, and 7% (6/85) in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

Safety data

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 100% of patients in the 400 mg arm, 98% in the 500 mg arm, and 94% in the placebo arm. Serious AEs occurred in 27%, 31%, and 23%, respectively. AEs leading to discontinuation occurred in 14%, 25%, and 8%, respectively.

Infections occurred in 42% of patients in the 400 mg arm, 39% of patients in the 500 mg arm, and 27% of patients of patients in the placebo arm.

Nonhematologic AEs occurring in at least 10% of patients in any group were diarrhea (66%, 56%, and 16%, respectively), vomiting (42%, 55%, and 5%, respectively), nausea (64%, 51%, and 15%, respectively), constipation (10%, 18%, and 7%, respectively), asthenia (9%, 16%, and 6%, respectively), abdominal pain (15%, 12%, and 16%, respectively), fatigue (16%, 10%, and 10%, respectively), dyspnea (8%, 10%, and 6%, respectively), and weight loss (4%, 10%, and 5%, respectively).

Hematologic AEs occurring in at least 10% of patients in any group were anemia (99%, 98%, and 91%, respectively), thrombocytopenia (63%, 57%, and 51%, respectively), lymphopenia (57%, 66%, and 54%, respectively), leukopenia (47%, 53%, and 19%, respectively), and neutropenia (28%, 44%, and 15%, respectively).

One patient in each fedratinib arm and 2 in the placebo arm transformed to acute myeloid leukemia.

There were 24 deaths during the first 24 weeks of the study—4 in the 400 mg arm, 10 in the 500 mg arm, and 10 in the placebo arm. Nine of the deaths were attributed to AEs—1, 4, and 4, respectively.

Wernicke encephalopathy

There were 4 cases of Wernicke encephalopathy, all in women who received fedratinib at 500 mg. All of these cases were confirmed by an independent expert safety panel, 3 on the basis of clinical features and MRI results, and 1 on the basis of clinical symptoms alone.

The patients developed symptoms 6 weeks to 44 weeks after beginning fedratinib treatment, and all discontinued treatment permanently.

Cognitive symptoms manifested in the context of persistent vomiting, malnutrition, and cachexia in 1 patient, vomiting and hyponatremia in 1 patient, and renal failure with mild hyponatremia in 1 patient.

All of the patients received intravenous thiamine and showed responses to the treatment, but all had persistent cognitive defects at last follow-up. ![]()

The LAST Study: CML trial examines life after TKIs

In the last 12 months, 12 actively recruiting trials examining chronic myeloid leukemia have been listed at clinicaltrials.gov.

Most of these trials examine the efficacy of various tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), but one trial called The LAST Study seeks to determine what happens to patients after TKIs – those patients who have undetectable BCR-ABL by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for at least 2 years. The goal of this study is to improve decision making for TKI discontinuation, and patients will be closely monitored for molecular recurrence, testing them monthly for 6 months, then every other month for 24 months, and quarterly until 36 months. Patients who have molecular chronic myelogenous leukemia recurrence will restart TKIs and will continue to be monitored for disease status and patient-reported health status.

All study participants must currently be taking a TKI for at least 3 years and have documented undetectable BCR-ABL by PCR for at least 2 years. Two screening PCRs must have been completed with results less than MR4.5. Participation is not limited by the number of TKIs, but no participant can be resistant to any TKI, and patients need to have been compliant with therapy. Patients with prior stem cell transplants are excluded, as are patients with less than 36 months life expectancy and pregnant or lactating women.

Click here to learn more about The LAST Study.

In the last 12 months, 12 actively recruiting trials examining chronic myeloid leukemia have been listed at clinicaltrials.gov.

Most of these trials examine the efficacy of various tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), but one trial called The LAST Study seeks to determine what happens to patients after TKIs – those patients who have undetectable BCR-ABL by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for at least 2 years. The goal of this study is to improve decision making for TKI discontinuation, and patients will be closely monitored for molecular recurrence, testing them monthly for 6 months, then every other month for 24 months, and quarterly until 36 months. Patients who have molecular chronic myelogenous leukemia recurrence will restart TKIs and will continue to be monitored for disease status and patient-reported health status.

All study participants must currently be taking a TKI for at least 3 years and have documented undetectable BCR-ABL by PCR for at least 2 years. Two screening PCRs must have been completed with results less than MR4.5. Participation is not limited by the number of TKIs, but no participant can be resistant to any TKI, and patients need to have been compliant with therapy. Patients with prior stem cell transplants are excluded, as are patients with less than 36 months life expectancy and pregnant or lactating women.

Click here to learn more about The LAST Study.

In the last 12 months, 12 actively recruiting trials examining chronic myeloid leukemia have been listed at clinicaltrials.gov.

Most of these trials examine the efficacy of various tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), but one trial called The LAST Study seeks to determine what happens to patients after TKIs – those patients who have undetectable BCR-ABL by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for at least 2 years. The goal of this study is to improve decision making for TKI discontinuation, and patients will be closely monitored for molecular recurrence, testing them monthly for 6 months, then every other month for 24 months, and quarterly until 36 months. Patients who have molecular chronic myelogenous leukemia recurrence will restart TKIs and will continue to be monitored for disease status and patient-reported health status.

All study participants must currently be taking a TKI for at least 3 years and have documented undetectable BCR-ABL by PCR for at least 2 years. Two screening PCRs must have been completed with results less than MR4.5. Participation is not limited by the number of TKIs, but no participant can be resistant to any TKI, and patients need to have been compliant with therapy. Patients with prior stem cell transplants are excluded, as are patients with less than 36 months life expectancy and pregnant or lactating women.

Click here to learn more about The LAST Study.

FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Online resource launched to prevent inpatient hospital falls

An online resource guide offers 21 targeted solutions for reducing the rate of falls in hospitals and urgent care settings, The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare announced in a statement.

Using the fall prevention methodology of the Targeted Solutions Tool, developed in collaboration with seven hospitals and five health care organizations, a typical 200-bed hospital could potentially reduce the number of patients injured from a fall from 117 to 45, avoiding approximately $1 million in costs annually, the agency claims.

Some of the recommendations for reducing in-hospital falls include:

• Creating awareness among staff.

• Using a validated fall risk assessment tool.

• Engaging patients and their families in the fall safety program.

• Hourly rounding with scheduled restroom use for patients.

• Engaging all hospital staff and patients to ensure no patient walks without assistance.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients fall in hospitals every year and many of these falls result in moderate to severe injuries that can prolong hospital stays and require the patient to undergo additional treatment,” Dr. Erin DuPree, vice president and chief medical officer of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, said in a statement.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was created in 2008 as a nonprofit affiliate of The Joint Commission.

Check out the online resource here.

An online resource guide offers 21 targeted solutions for reducing the rate of falls in hospitals and urgent care settings, The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare announced in a statement.

Using the fall prevention methodology of the Targeted Solutions Tool, developed in collaboration with seven hospitals and five health care organizations, a typical 200-bed hospital could potentially reduce the number of patients injured from a fall from 117 to 45, avoiding approximately $1 million in costs annually, the agency claims.

Some of the recommendations for reducing in-hospital falls include:

• Creating awareness among staff.

• Using a validated fall risk assessment tool.

• Engaging patients and their families in the fall safety program.

• Hourly rounding with scheduled restroom use for patients.

• Engaging all hospital staff and patients to ensure no patient walks without assistance.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients fall in hospitals every year and many of these falls result in moderate to severe injuries that can prolong hospital stays and require the patient to undergo additional treatment,” Dr. Erin DuPree, vice president and chief medical officer of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, said in a statement.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was created in 2008 as a nonprofit affiliate of The Joint Commission.

Check out the online resource here.

An online resource guide offers 21 targeted solutions for reducing the rate of falls in hospitals and urgent care settings, The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare announced in a statement.

Using the fall prevention methodology of the Targeted Solutions Tool, developed in collaboration with seven hospitals and five health care organizations, a typical 200-bed hospital could potentially reduce the number of patients injured from a fall from 117 to 45, avoiding approximately $1 million in costs annually, the agency claims.

Some of the recommendations for reducing in-hospital falls include:

• Creating awareness among staff.

• Using a validated fall risk assessment tool.

• Engaging patients and their families in the fall safety program.

• Hourly rounding with scheduled restroom use for patients.

• Engaging all hospital staff and patients to ensure no patient walks without assistance.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients fall in hospitals every year and many of these falls result in moderate to severe injuries that can prolong hospital stays and require the patient to undergo additional treatment,” Dr. Erin DuPree, vice president and chief medical officer of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, said in a statement.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was created in 2008 as a nonprofit affiliate of The Joint Commission.

Check out the online resource here.

Why go to international conferences?

I recently returned from the DASS (Dermatology and Allied Specialties Summit) in New Delhi. It was interesting and thought provoking. New Delhi, and India in general, are modern and ancient, growing like Topsy, crushed into one another, in a hyperkinetic mix, something like Mexico on amphetamines.

I generally find conferences far afield introduce novel ideas. It helps greatly that these conferences almost always use English as the official language.

The underlying concept for DASS is multidisciplinary, which is unusual in dermatology. It was rewarding to discuss skin cancer treatment with surgical oncologists, plastic and general surgeons, and medical oncologists. There were also discussions on polycystic ovary disease, rosacea and the “red face,” current treatment of Hansen disease, man-eating psoriasis and urticaria, and of course, botulinum toxin, fillers, lasers, and chemical peels. Of great interest were new “old” treatments for skin disease, since biologics are generally not affordable.

I also got into lively discussions at the World Congress of Dermatology in Vancouver a few weeks earlier. The problem in many countries is funding of dermatologic treatments (particularly Mohs) within a fixed dermatology budget. We in the United States can vote with our feet, and generally seek out treatment we decide is best. Over the past 30 years, 70% of skin cancer has migrated from hospital-based surgical specialties to office-based dermatology, at great cost savings to the health care system.

In most of the world, the government allocates money, and tells hospitals and doctors to make do. This results in a static, change-resistant budget process, where patients have even fewer choices than in the U.S. Hospitals always win in these budget battles, to the detriment of office-based medicine and patient choice, and innovation.

Internationally, correcting this may require dermatologists going to politicians and not saying, “we need more money,” but rather saying, “we can save you money.” For example, if 99% of skin cancer treatment moves out of the hospital to the office setting, where it should be, the budgeteers should be delighted to pay your office costs, which are a fraction of those for an operating room. The budget should reflect that X number of new operating rooms do not need to be built, X number of scrub nurses do not need to trained or can be reassigned, X number of support staff are not needed, or that wait times, a chronic complaint around the world, can shrink.

There will be resistance to this approach from hospital-dependent specialists, and the hospitals. They will argue it isn’t safe, and that the costs aren’t defined. However, these issues have been worked out in detail and the data published.

The same argument can be made for the use of biologics. How many erythrodermic hospitalizations will be avoided? How many missed days of work will not be missed?

It is far easier to budge a bureaucracy by emphasizing cost savings rather than quality, though these are opportunities for dermatologists to improve both.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati. Email him at [email protected].

I recently returned from the DASS (Dermatology and Allied Specialties Summit) in New Delhi. It was interesting and thought provoking. New Delhi, and India in general, are modern and ancient, growing like Topsy, crushed into one another, in a hyperkinetic mix, something like Mexico on amphetamines.

I generally find conferences far afield introduce novel ideas. It helps greatly that these conferences almost always use English as the official language.

The underlying concept for DASS is multidisciplinary, which is unusual in dermatology. It was rewarding to discuss skin cancer treatment with surgical oncologists, plastic and general surgeons, and medical oncologists. There were also discussions on polycystic ovary disease, rosacea and the “red face,” current treatment of Hansen disease, man-eating psoriasis and urticaria, and of course, botulinum toxin, fillers, lasers, and chemical peels. Of great interest were new “old” treatments for skin disease, since biologics are generally not affordable.

I also got into lively discussions at the World Congress of Dermatology in Vancouver a few weeks earlier. The problem in many countries is funding of dermatologic treatments (particularly Mohs) within a fixed dermatology budget. We in the United States can vote with our feet, and generally seek out treatment we decide is best. Over the past 30 years, 70% of skin cancer has migrated from hospital-based surgical specialties to office-based dermatology, at great cost savings to the health care system.

In most of the world, the government allocates money, and tells hospitals and doctors to make do. This results in a static, change-resistant budget process, where patients have even fewer choices than in the U.S. Hospitals always win in these budget battles, to the detriment of office-based medicine and patient choice, and innovation.

Internationally, correcting this may require dermatologists going to politicians and not saying, “we need more money,” but rather saying, “we can save you money.” For example, if 99% of skin cancer treatment moves out of the hospital to the office setting, where it should be, the budgeteers should be delighted to pay your office costs, which are a fraction of those for an operating room. The budget should reflect that X number of new operating rooms do not need to be built, X number of scrub nurses do not need to trained or can be reassigned, X number of support staff are not needed, or that wait times, a chronic complaint around the world, can shrink.

There will be resistance to this approach from hospital-dependent specialists, and the hospitals. They will argue it isn’t safe, and that the costs aren’t defined. However, these issues have been worked out in detail and the data published.

The same argument can be made for the use of biologics. How many erythrodermic hospitalizations will be avoided? How many missed days of work will not be missed?

It is far easier to budge a bureaucracy by emphasizing cost savings rather than quality, though these are opportunities for dermatologists to improve both.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati. Email him at [email protected].

I recently returned from the DASS (Dermatology and Allied Specialties Summit) in New Delhi. It was interesting and thought provoking. New Delhi, and India in general, are modern and ancient, growing like Topsy, crushed into one another, in a hyperkinetic mix, something like Mexico on amphetamines.

I generally find conferences far afield introduce novel ideas. It helps greatly that these conferences almost always use English as the official language.

The underlying concept for DASS is multidisciplinary, which is unusual in dermatology. It was rewarding to discuss skin cancer treatment with surgical oncologists, plastic and general surgeons, and medical oncologists. There were also discussions on polycystic ovary disease, rosacea and the “red face,” current treatment of Hansen disease, man-eating psoriasis and urticaria, and of course, botulinum toxin, fillers, lasers, and chemical peels. Of great interest were new “old” treatments for skin disease, since biologics are generally not affordable.

I also got into lively discussions at the World Congress of Dermatology in Vancouver a few weeks earlier. The problem in many countries is funding of dermatologic treatments (particularly Mohs) within a fixed dermatology budget. We in the United States can vote with our feet, and generally seek out treatment we decide is best. Over the past 30 years, 70% of skin cancer has migrated from hospital-based surgical specialties to office-based dermatology, at great cost savings to the health care system.

In most of the world, the government allocates money, and tells hospitals and doctors to make do. This results in a static, change-resistant budget process, where patients have even fewer choices than in the U.S. Hospitals always win in these budget battles, to the detriment of office-based medicine and patient choice, and innovation.

Internationally, correcting this may require dermatologists going to politicians and not saying, “we need more money,” but rather saying, “we can save you money.” For example, if 99% of skin cancer treatment moves out of the hospital to the office setting, where it should be, the budgeteers should be delighted to pay your office costs, which are a fraction of those for an operating room. The budget should reflect that X number of new operating rooms do not need to be built, X number of scrub nurses do not need to trained or can be reassigned, X number of support staff are not needed, or that wait times, a chronic complaint around the world, can shrink.

There will be resistance to this approach from hospital-dependent specialists, and the hospitals. They will argue it isn’t safe, and that the costs aren’t defined. However, these issues have been worked out in detail and the data published.

The same argument can be made for the use of biologics. How many erythrodermic hospitalizations will be avoided? How many missed days of work will not be missed?

It is far easier to budge a bureaucracy by emphasizing cost savings rather than quality, though these are opportunities for dermatologists to improve both.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice, but maintains a clinical assistant professorship of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati. Email him at [email protected].

Triple Therapy May Increase Major Bleeding in Older Patients with Acute MI, AF

NEW YORK - Compared with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), triple therapy increases the risk of major bleeding without altering the rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or death in older patients with acute MI and atrial fibrillation (AF), according to a registry study.

"These data suggest that the risk-benefit ratio of triple therapy in older patients with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation should be carefully considered," Dr. Connie N. Hess, from Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, told Reuters Health by email. "However, these results need to be confirmed with prospective studies; a number of ongoing randomized clinical trials may help to provide insight."

Therapeutic decisions for older patients with acute MI and AF are challenging, not least because they have been excluded from or underrepresented in clinical trials.

Dr. Hess's team linked data from the ACTION Registry Get With The Guidelines and Medicare administrative claims to compare outcomes with DAPT or triple therapy (DAPT plus warfarin) in 4959 patients age 65 and older with acute MI and AF who underwent coronary stenting.

More patients were discharged on DAPT (72.4%) than on triple therapy (27.6%), the researchers report in the August 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), available online now.

The primary effectiveness outcome, major adverse cardiac events (MACE, including death or readmission for MI or stroke) at two years, did not differ in incidence between triple therapy (32.6%) and DAPT (32.7%), and there were no significant differences in the incidences of the individual MACE components.

In contrast, the cumulative incidence of bleeding requiring hospitalization within two years of discharge was significantly higher for patients on triple therapy (17.6%) than for patients on DAPT (11.0%; p<0.0001), and this difference persisted after adjustment for case-mix, treatment, and hospital features.

Triple therapy was also associated with a 2.04-fold higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage, compared with DAPT.

The association of triple therapy with MACE and bleeding outcomes was similar for patients older and younger than 75, for men and women, for patients with low and high predicted stroke risk, for patients with shorter versus longer duration of AF, for patients treated with drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents, and for patients presenting with non-ST-segment elevation MI versus ST-segment elevation MI.

"Until we have data from prospective studies to define optimal antithrombotic use in older patients with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation, providers should be especially mindful of an individual's bleeding risk when deciding to prescribe triple therapy," Dr. Hess concluded.

Dr. John C. Messenger, from the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, cowrote an editorial related to this report. He told Reuters Health by email, "We should ideally look to minimize duration of triple therapy, keeping it as short as possible. We also need to enroll patients in trials designed to evaluate double therapy without the use of aspirin."

"With the change in guidelines recommending oral anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation at lower risk for ischemic stroke, the negative impact of bleeding related to the use of triple therapy may far outweigh the benefit of reduction of ischemic stroke," Dr. Messenger said. "We obviously need further study on this topic."

Dr. Andrea Rubboli, from Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna, Italy, has researched how best to treat these patients. He told Reuters Health by email, "Given that I practice in Europe, where current guidelines recommend triple therapy for these patients, what I found most surprising is the relatively small proportion of AF patients treated with (percutaneous coronary intervention) PCI who were discharged on triple therapy. Conversely, it was not surprising that DAPT was comparable to triple therapy in terms of MACE and superior in terms of bleeding because this has been previously reported and the several limitations of this kind of analysis (especially the lack of information on the therapy really ongoing at the time of event) may account for that."

"Triple therapy confirmed to be the best treatment for these patients," Dr. Rubboli concluded. "While not reducing MACE versus DAPT, it is indeed significantly more effective in reducing the most feared and devastating complication of AF, that is, stroke. Given the increased risk of bleeding, however, great care should be put in monitoring such therapy."

Dr. Nikolaus Sarafoff, from Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany, told Reuters Health by email, "In my opinion, one major limitation of the study is that only 7.7% of patients in the DAPT group were on oral anticoagulation (OAC) at randomization as compared to 62.1% in the triple arm. This shows clearly that physicians felt that patients in the DAPT arm had no real indication for OAC (even before the myocardial infarction with PCI occurred) and this makes the comparison of the two groups very difficult."

"The indication for triple therapy and the optimal antithrombotic treatment should be taken carefully, weighing the bleeding and the ischemic risk of the patient," Dr. Sarafoff concluded. "Several options to reduce bleeding complications in this high-risk population exist, such as omitting aspirin, shortening the duration of therapy. The results of the present study cannot supplant current guidelines that state clearly that patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc Score 2 are in need of OAC no matter whether concomitant antiplatelet therapy is needed."

The American College of Cardiology Foundation's National Cardiovascular Data Registry supported this study. Three coauthors reported relevant relationships.

NEW YORK - Compared with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), triple therapy increases the risk of major bleeding without altering the rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or death in older patients with acute MI and atrial fibrillation (AF), according to a registry study.

"These data suggest that the risk-benefit ratio of triple therapy in older patients with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation should be carefully considered," Dr. Connie N. Hess, from Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, told Reuters Health by email. "However, these results need to be confirmed with prospective studies; a number of ongoing randomized clinical trials may help to provide insight."

Therapeutic decisions for older patients with acute MI and AF are challenging, not least because they have been excluded from or underrepresented in clinical trials.

Dr. Hess's team linked data from the ACTION Registry Get With The Guidelines and Medicare administrative claims to compare outcomes with DAPT or triple therapy (DAPT plus warfarin) in 4959 patients age 65 and older with acute MI and AF who underwent coronary stenting.

More patients were discharged on DAPT (72.4%) than on triple therapy (27.6%), the researchers report in the August 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), available online now.

The primary effectiveness outcome, major adverse cardiac events (MACE, including death or readmission for MI or stroke) at two years, did not differ in incidence between triple therapy (32.6%) and DAPT (32.7%), and there were no significant differences in the incidences of the individual MACE components.

In contrast, the cumulative incidence of bleeding requiring hospitalization within two years of discharge was significantly higher for patients on triple therapy (17.6%) than for patients on DAPT (11.0%; p<0.0001), and this difference persisted after adjustment for case-mix, treatment, and hospital features.

Triple therapy was also associated with a 2.04-fold higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage, compared with DAPT.

The association of triple therapy with MACE and bleeding outcomes was similar for patients older and younger than 75, for men and women, for patients with low and high predicted stroke risk, for patients with shorter versus longer duration of AF, for patients treated with drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents, and for patients presenting with non-ST-segment elevation MI versus ST-segment elevation MI.

"Until we have data from prospective studies to define optimal antithrombotic use in older patients with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation, providers should be especially mindful of an individual's bleeding risk when deciding to prescribe triple therapy," Dr. Hess concluded.

Dr. John C. Messenger, from the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, cowrote an editorial related to this report. He told Reuters Health by email, "We should ideally look to minimize duration of triple therapy, keeping it as short as possible. We also need to enroll patients in trials designed to evaluate double therapy without the use of aspirin."

"With the change in guidelines recommending oral anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation at lower risk for ischemic stroke, the negative impact of bleeding related to the use of triple therapy may far outweigh the benefit of reduction of ischemic stroke," Dr. Messenger said. "We obviously need further study on this topic."

Dr. Andrea Rubboli, from Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna, Italy, has researched how best to treat these patients. He told Reuters Health by email, "Given that I practice in Europe, where current guidelines recommend triple therapy for these patients, what I found most surprising is the relatively small proportion of AF patients treated with (percutaneous coronary intervention) PCI who were discharged on triple therapy. Conversely, it was not surprising that DAPT was comparable to triple therapy in terms of MACE and superior in terms of bleeding because this has been previously reported and the several limitations of this kind of analysis (especially the lack of information on the therapy really ongoing at the time of event) may account for that."

"Triple therapy confirmed to be the best treatment for these patients," Dr. Rubboli concluded. "While not reducing MACE versus DAPT, it is indeed significantly more effective in reducing the most feared and devastating complication of AF, that is, stroke. Given the increased risk of bleeding, however, great care should be put in monitoring such therapy."

Dr. Nikolaus Sarafoff, from Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany, told Reuters Health by email, "In my opinion, one major limitation of the study is that only 7.7% of patients in the DAPT group were on oral anticoagulation (OAC) at randomization as compared to 62.1% in the triple arm. This shows clearly that physicians felt that patients in the DAPT arm had no real indication for OAC (even before the myocardial infarction with PCI occurred) and this makes the comparison of the two groups very difficult."

"The indication for triple therapy and the optimal antithrombotic treatment should be taken carefully, weighing the bleeding and the ischemic risk of the patient," Dr. Sarafoff concluded. "Several options to reduce bleeding complications in this high-risk population exist, such as omitting aspirin, shortening the duration of therapy. The results of the present study cannot supplant current guidelines that state clearly that patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc Score 2 are in need of OAC no matter whether concomitant antiplatelet therapy is needed."

The American College of Cardiology Foundation's National Cardiovascular Data Registry supported this study. Three coauthors reported relevant relationships.

NEW YORK - Compared with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), triple therapy increases the risk of major bleeding without altering the rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or death in older patients with acute MI and atrial fibrillation (AF), according to a registry study.

"These data suggest that the risk-benefit ratio of triple therapy in older patients with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation should be carefully considered," Dr. Connie N. Hess, from Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, told Reuters Health by email. "However, these results need to be confirmed with prospective studies; a number of ongoing randomized clinical trials may help to provide insight."

Therapeutic decisions for older patients with acute MI and AF are challenging, not least because they have been excluded from or underrepresented in clinical trials.

Dr. Hess's team linked data from the ACTION Registry Get With The Guidelines and Medicare administrative claims to compare outcomes with DAPT or triple therapy (DAPT plus warfarin) in 4959 patients age 65 and older with acute MI and AF who underwent coronary stenting.

More patients were discharged on DAPT (72.4%) than on triple therapy (27.6%), the researchers report in the August 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), available online now.

The primary effectiveness outcome, major adverse cardiac events (MACE, including death or readmission for MI or stroke) at two years, did not differ in incidence between triple therapy (32.6%) and DAPT (32.7%), and there were no significant differences in the incidences of the individual MACE components.

In contrast, the cumulative incidence of bleeding requiring hospitalization within two years of discharge was significantly higher for patients on triple therapy (17.6%) than for patients on DAPT (11.0%; p<0.0001), and this difference persisted after adjustment for case-mix, treatment, and hospital features.

Triple therapy was also associated with a 2.04-fold higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage, compared with DAPT.

The association of triple therapy with MACE and bleeding outcomes was similar for patients older and younger than 75, for men and women, for patients with low and high predicted stroke risk, for patients with shorter versus longer duration of AF, for patients treated with drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents, and for patients presenting with non-ST-segment elevation MI versus ST-segment elevation MI.

"Until we have data from prospective studies to define optimal antithrombotic use in older patients with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation, providers should be especially mindful of an individual's bleeding risk when deciding to prescribe triple therapy," Dr. Hess concluded.

Dr. John C. Messenger, from the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, cowrote an editorial related to this report. He told Reuters Health by email, "We should ideally look to minimize duration of triple therapy, keeping it as short as possible. We also need to enroll patients in trials designed to evaluate double therapy without the use of aspirin."

"With the change in guidelines recommending oral anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation at lower risk for ischemic stroke, the negative impact of bleeding related to the use of triple therapy may far outweigh the benefit of reduction of ischemic stroke," Dr. Messenger said. "We obviously need further study on this topic."

Dr. Andrea Rubboli, from Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna, Italy, has researched how best to treat these patients. He told Reuters Health by email, "Given that I practice in Europe, where current guidelines recommend triple therapy for these patients, what I found most surprising is the relatively small proportion of AF patients treated with (percutaneous coronary intervention) PCI who were discharged on triple therapy. Conversely, it was not surprising that DAPT was comparable to triple therapy in terms of MACE and superior in terms of bleeding because this has been previously reported and the several limitations of this kind of analysis (especially the lack of information on the therapy really ongoing at the time of event) may account for that."

"Triple therapy confirmed to be the best treatment for these patients," Dr. Rubboli concluded. "While not reducing MACE versus DAPT, it is indeed significantly more effective in reducing the most feared and devastating complication of AF, that is, stroke. Given the increased risk of bleeding, however, great care should be put in monitoring such therapy."

Dr. Nikolaus Sarafoff, from Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany, told Reuters Health by email, "In my opinion, one major limitation of the study is that only 7.7% of patients in the DAPT group were on oral anticoagulation (OAC) at randomization as compared to 62.1% in the triple arm. This shows clearly that physicians felt that patients in the DAPT arm had no real indication for OAC (even before the myocardial infarction with PCI occurred) and this makes the comparison of the two groups very difficult."

"The indication for triple therapy and the optimal antithrombotic treatment should be taken carefully, weighing the bleeding and the ischemic risk of the patient," Dr. Sarafoff concluded. "Several options to reduce bleeding complications in this high-risk population exist, such as omitting aspirin, shortening the duration of therapy. The results of the present study cannot supplant current guidelines that state clearly that patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc Score 2 are in need of OAC no matter whether concomitant antiplatelet therapy is needed."

The American College of Cardiology Foundation's National Cardiovascular Data Registry supported this study. Three coauthors reported relevant relationships.

How malaria increases the risk of Burkitt lymphoma

Image by Ed Uthman

A link between malaria and Burkitt lymphoma was first described more than 50 years ago, but how the parasitic infection promotes lymphomagenesis has remained a mystery.

Now, research in mice has revealed that B-cell DNA becomes vulnerable to cancer-causing mutations during prolonged combat against the malaria parasite.

Davide Robbiani, MD, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York, and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The team infected mice with the malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi and, immediately, the mice experienced an increase in germinal center (GC) B lymphocytes, which can give rise to Burkitt lymphoma.

“In malaria-infected mice, these cells divide very rapidly over the course of months,” Dr Robbiani said.

As the GC B lymphocytes proliferate, they also express high levels of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which induces mutations in their DNA. As a result, these cells can diversify to generate a wide range of antibodies.

But in addition to beneficial mutations in antibody genes, AID can cause off-target damage and shuffling of cancer-causing genes.

“In mice infected with the malaria parasite, these so-called chromosomal rearrangements occur very frequently in GC lymphocytes,” Dr Robbiani said. “And at least some of the changes are due to AID.”

To further investigate this phenomenon, the researchers bred mice lacking the p53 gene, which is known to protect cells from Burkitt lymphoma. All of the mice that expressed AID but not p53 ultimately developed lymphoma.

And when these mice were infected with the malaria parasite, they developed lymphomas specifically in mature B cells, similar to what happens in Burkitt lymphoma.

“This finding sheds new light on a long-standing mystery of why two seemingly different diseases are associated with each other,” Dr Robbiani said.

Researchers are now attempting to determine how AID causes its off-target damage to DNA, which could lead to new treatments.

“If we could somehow limit this collateral damage to cancer-causing genes without reducing the infection-fighting powers of B cells, that could be very useful,” Dr Robbiani said. “But first, we have to find out how the collateral DNA damage occurs in the first place.”

Dr Robbiani noted that hepatitis C virus and Helicobacter pylori infections, as well as some autoimmune diseases, are also linked with

chronic B lymphocyte activation and an increased risk of lymphoma.

Therefore,

strategies aimed at reducing unintended DNA damage caused by AID might

also help reduce the risk of lymphoma in patients with these conditions.

“It’s possible that AID also plays a role in the association between these other infections and cancer,” Dr Robbiani said. “This is purely a speculation at this point, though highly suggestive.” ![]()

Image by Ed Uthman

A link between malaria and Burkitt lymphoma was first described more than 50 years ago, but how the parasitic infection promotes lymphomagenesis has remained a mystery.

Now, research in mice has revealed that B-cell DNA becomes vulnerable to cancer-causing mutations during prolonged combat against the malaria parasite.

Davide Robbiani, MD, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York, and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The team infected mice with the malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi and, immediately, the mice experienced an increase in germinal center (GC) B lymphocytes, which can give rise to Burkitt lymphoma.

“In malaria-infected mice, these cells divide very rapidly over the course of months,” Dr Robbiani said.

As the GC B lymphocytes proliferate, they also express high levels of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which induces mutations in their DNA. As a result, these cells can diversify to generate a wide range of antibodies.

But in addition to beneficial mutations in antibody genes, AID can cause off-target damage and shuffling of cancer-causing genes.

“In mice infected with the malaria parasite, these so-called chromosomal rearrangements occur very frequently in GC lymphocytes,” Dr Robbiani said. “And at least some of the changes are due to AID.”

To further investigate this phenomenon, the researchers bred mice lacking the p53 gene, which is known to protect cells from Burkitt lymphoma. All of the mice that expressed AID but not p53 ultimately developed lymphoma.

And when these mice were infected with the malaria parasite, they developed lymphomas specifically in mature B cells, similar to what happens in Burkitt lymphoma.

“This finding sheds new light on a long-standing mystery of why two seemingly different diseases are associated with each other,” Dr Robbiani said.

Researchers are now attempting to determine how AID causes its off-target damage to DNA, which could lead to new treatments.

“If we could somehow limit this collateral damage to cancer-causing genes without reducing the infection-fighting powers of B cells, that could be very useful,” Dr Robbiani said. “But first, we have to find out how the collateral DNA damage occurs in the first place.”

Dr Robbiani noted that hepatitis C virus and Helicobacter pylori infections, as well as some autoimmune diseases, are also linked with

chronic B lymphocyte activation and an increased risk of lymphoma.

Therefore,

strategies aimed at reducing unintended DNA damage caused by AID might

also help reduce the risk of lymphoma in patients with these conditions.

“It’s possible that AID also plays a role in the association between these other infections and cancer,” Dr Robbiani said. “This is purely a speculation at this point, though highly suggestive.” ![]()

Image by Ed Uthman

A link between malaria and Burkitt lymphoma was first described more than 50 years ago, but how the parasitic infection promotes lymphomagenesis has remained a mystery.

Now, research in mice has revealed that B-cell DNA becomes vulnerable to cancer-causing mutations during prolonged combat against the malaria parasite.

Davide Robbiani, MD, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York, and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The team infected mice with the malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi and, immediately, the mice experienced an increase in germinal center (GC) B lymphocytes, which can give rise to Burkitt lymphoma.

“In malaria-infected mice, these cells divide very rapidly over the course of months,” Dr Robbiani said.

As the GC B lymphocytes proliferate, they also express high levels of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which induces mutations in their DNA. As a result, these cells can diversify to generate a wide range of antibodies.

But in addition to beneficial mutations in antibody genes, AID can cause off-target damage and shuffling of cancer-causing genes.

“In mice infected with the malaria parasite, these so-called chromosomal rearrangements occur very frequently in GC lymphocytes,” Dr Robbiani said. “And at least some of the changes are due to AID.”

To further investigate this phenomenon, the researchers bred mice lacking the p53 gene, which is known to protect cells from Burkitt lymphoma. All of the mice that expressed AID but not p53 ultimately developed lymphoma.

And when these mice were infected with the malaria parasite, they developed lymphomas specifically in mature B cells, similar to what happens in Burkitt lymphoma.

“This finding sheds new light on a long-standing mystery of why two seemingly different diseases are associated with each other,” Dr Robbiani said.

Researchers are now attempting to determine how AID causes its off-target damage to DNA, which could lead to new treatments.

“If we could somehow limit this collateral damage to cancer-causing genes without reducing the infection-fighting powers of B cells, that could be very useful,” Dr Robbiani said. “But first, we have to find out how the collateral DNA damage occurs in the first place.”

Dr Robbiani noted that hepatitis C virus and Helicobacter pylori infections, as well as some autoimmune diseases, are also linked with

chronic B lymphocyte activation and an increased risk of lymphoma.

Therefore,

strategies aimed at reducing unintended DNA damage caused by AID might

also help reduce the risk of lymphoma in patients with these conditions.

“It’s possible that AID also plays a role in the association between these other infections and cancer,” Dr Robbiani said. “This is purely a speculation at this point, though highly suggestive.” ![]()

Remember ‘CURE’ indication for clopidogrel in ACS

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Clopidogrel is vastly underutilized in real-world medical management of patients with unstable angina or non–ST-segment elevation MI who don’t undergo coronary revascularization, Dr. Mel L. Anderson said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Such patients fall under the umbrella of the so-called CURE indication for clopidogrel, named for the landmark Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events trial. CURE showed that adding clopidogrel to aspirin for an average of 9 months in patients with acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation reduced the major adverse cardiovascular event rate from 11.4% to 9.3% (N Engl J Med. 2001;345[7]:494-502).

Clinical practice has changed enormously since CURE was published in 2001, so a group of investigators decided to see if discharging medically managed ACS patients on clopidogrel is still beneficial in the contemporary setting. They conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of 16,345 Kaiser Permanente Northern California patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI managed medically without percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft, of whom only 36% were discharged on clopidogrel.

“It’s disappointing that fully two-thirds of patients did not get clopidogrel when they had an indication for it,” commented Dr. Anderson, chief of the hospital medicine section at the Denver VA Medical Center and an internist at the university.

Two-year all-cause mortality was 8.3% in the clopidogrel users, compared with 13% in propensity-matched controls not on clopidogrel, for an adjusted 37% relative risk reduction in favor of the antiplatelet agent (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jun 3;63[21]:2249-57).

“That’s a number-needed-to-treat of 20. It’s really quite a robust benefit for a drug that’s now generic and has a well-established safety profile,” Dr. Anderson continued.

The 2-year composite outcome of death or MI occurred in 13.5% of the clopidogrel group and 17.4% of controls, for a number-needed-to-treat of about 25. Clopidogrel’s benefit in terms of this composite endpoint achieved significance only among the 65% of participants with NSTEMI, not those with unstable angina.

“Don’t forget the CURE indication for clopidogrel,” the hospitalist concluded.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Clopidogrel is vastly underutilized in real-world medical management of patients with unstable angina or non–ST-segment elevation MI who don’t undergo coronary revascularization, Dr. Mel L. Anderson said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Such patients fall under the umbrella of the so-called CURE indication for clopidogrel, named for the landmark Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events trial. CURE showed that adding clopidogrel to aspirin for an average of 9 months in patients with acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation reduced the major adverse cardiovascular event rate from 11.4% to 9.3% (N Engl J Med. 2001;345[7]:494-502).

Clinical practice has changed enormously since CURE was published in 2001, so a group of investigators decided to see if discharging medically managed ACS patients on clopidogrel is still beneficial in the contemporary setting. They conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of 16,345 Kaiser Permanente Northern California patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI managed medically without percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft, of whom only 36% were discharged on clopidogrel.

“It’s disappointing that fully two-thirds of patients did not get clopidogrel when they had an indication for it,” commented Dr. Anderson, chief of the hospital medicine section at the Denver VA Medical Center and an internist at the university.

Two-year all-cause mortality was 8.3% in the clopidogrel users, compared with 13% in propensity-matched controls not on clopidogrel, for an adjusted 37% relative risk reduction in favor of the antiplatelet agent (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jun 3;63[21]:2249-57).

“That’s a number-needed-to-treat of 20. It’s really quite a robust benefit for a drug that’s now generic and has a well-established safety profile,” Dr. Anderson continued.

The 2-year composite outcome of death or MI occurred in 13.5% of the clopidogrel group and 17.4% of controls, for a number-needed-to-treat of about 25. Clopidogrel’s benefit in terms of this composite endpoint achieved significance only among the 65% of participants with NSTEMI, not those with unstable angina.

“Don’t forget the CURE indication for clopidogrel,” the hospitalist concluded.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Clopidogrel is vastly underutilized in real-world medical management of patients with unstable angina or non–ST-segment elevation MI who don’t undergo coronary revascularization, Dr. Mel L. Anderson said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Such patients fall under the umbrella of the so-called CURE indication for clopidogrel, named for the landmark Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events trial. CURE showed that adding clopidogrel to aspirin for an average of 9 months in patients with acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation reduced the major adverse cardiovascular event rate from 11.4% to 9.3% (N Engl J Med. 2001;345[7]:494-502).

Clinical practice has changed enormously since CURE was published in 2001, so a group of investigators decided to see if discharging medically managed ACS patients on clopidogrel is still beneficial in the contemporary setting. They conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of 16,345 Kaiser Permanente Northern California patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI managed medically without percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft, of whom only 36% were discharged on clopidogrel.

“It’s disappointing that fully two-thirds of patients did not get clopidogrel when they had an indication for it,” commented Dr. Anderson, chief of the hospital medicine section at the Denver VA Medical Center and an internist at the university.

Two-year all-cause mortality was 8.3% in the clopidogrel users, compared with 13% in propensity-matched controls not on clopidogrel, for an adjusted 37% relative risk reduction in favor of the antiplatelet agent (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Jun 3;63[21]:2249-57).

“That’s a number-needed-to-treat of 20. It’s really quite a robust benefit for a drug that’s now generic and has a well-established safety profile,” Dr. Anderson continued.

The 2-year composite outcome of death or MI occurred in 13.5% of the clopidogrel group and 17.4% of controls, for a number-needed-to-treat of about 25. Clopidogrel’s benefit in terms of this composite endpoint achieved significance only among the 65% of participants with NSTEMI, not those with unstable angina.

“Don’t forget the CURE indication for clopidogrel,” the hospitalist concluded.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

Algorithm can enhance clustering, aid trial design

Chenyue Wendy Hu

Photo courtesy of Jeff Fitlow

and Rice University

A newly developed algorithm for “big data” could have a significant impact on clinical trials, according to researchers.

The algorithm, called progeny clustering, was the only method to successfully reveal “clinically meaningful” groupings of proteomic data from patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

And the algorithm is currently being used in a hospital study to identify optimal treatment for children with leukemia.

Details on progeny clustering have been published in Scientific Reports.

The authors noted that clustering is important for its ability to reveal information in complex sets of data like medical records.

“Doctors who design clinical trials need to know how to group patients so they receive the most appropriate treatment,” said author Amina Qutub, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas. “First, they need to estimate the optimal number of clusters in their data.”

The more accurate the clusters, the more personalized the treatment can be, Dr Qutub said. She added that separating groups by a single data point would be easy, but when separating patients by the types of proteins in their bloodstreams, for example, it becomes more difficult.

“That’s the kind of data that’s become prevalent everywhere in biology, and it’s good to have,” Dr Qutub said. “We want to know hundreds of features about a single person. The problem is identifying how to use all that data.”

Progeny clustering provides a way to ensure the number of clusters is as accurate as possible, Dr Qutub said. The algorithm extracts characteristics about patients from a data set, mixing and matching them randomly to create artificial populations—the “progeny” of the parent data. The characteristics appear in roughly the same ratios in the progeny as they do among the parents.

These characteristics, called dimensions, can be anything: as simple as hair color or place of birth, or as detailed as blood cell count or the proteins expressed by tumor cells. For even a small population, each individual may have hundreds or thousands of dimensions.

By creating progeny with the same dimensions of features, the algorithm increases the size of the data set. With this additional data, the distinct patterns become more apparent, allowing the algorithm to optimize the number of clusters that warrant attention from doctors and researchers.

Dr Qutub said this technique is just as reliable as state-of-the-art clustering evaluation algorithms, but at a fraction of the computational cost. In lab tests, progeny clustering compared favorably to other popular methods.

And it was the only method to provide clinically meaningful groupings in an acute myeloid leukemia reverse-phase protein array data set.

Progeny clustering also allows researchers to determine the ideal number of clusters in small populations, Dr Qutub noted.

The algorithm was used to design an ongoing trial involving leukemia patients at Texas Children’s Hospital.

“Progeny clustering allowed them to design a robust clinical trial, even though that trial did not involve a large number of children,” Dr Qutub said. “It meant they didn’t have to wait to enroll more.”

Dr Qutub added that the algorithm could apply to any data set.

“We could just as easily use it for a population of voters to see who should get campaign materials from a candidate,” she said. “Progeny clustering has a lot of possible applications.”

Dr Qutub and her colleagues plan to make the algorithm available for free on her lab’s website. ![]()

Chenyue Wendy Hu

Photo courtesy of Jeff Fitlow

and Rice University

A newly developed algorithm for “big data” could have a significant impact on clinical trials, according to researchers.

The algorithm, called progeny clustering, was the only method to successfully reveal “clinically meaningful” groupings of proteomic data from patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

And the algorithm is currently being used in a hospital study to identify optimal treatment for children with leukemia.

Details on progeny clustering have been published in Scientific Reports.

The authors noted that clustering is important for its ability to reveal information in complex sets of data like medical records.

“Doctors who design clinical trials need to know how to group patients so they receive the most appropriate treatment,” said author Amina Qutub, PhD, of Rice University in Houston, Texas. “First, they need to estimate the optimal number of clusters in their data.”

The more accurate the clusters, the more personalized the treatment can be, Dr Qutub said. She added that separating groups by a single data point would be easy, but when separating patients by the types of proteins in their bloodstreams, for example, it becomes more difficult.

“That’s the kind of data that’s become prevalent everywhere in biology, and it’s good to have,” Dr Qutub said. “We want to know hundreds of features about a single person. The problem is identifying how to use all that data.”

Progeny clustering provides a way to ensure the number of clusters is as accurate as possible, Dr Qutub said. The algorithm extracts characteristics about patients from a data set, mixing and matching them randomly to create artificial populations—the “progeny” of the parent data. The characteristics appear in roughly the same ratios in the progeny as they do among the parents.

These characteristics, called dimensions, can be anything: as simple as hair color or place of birth, or as detailed as blood cell count or the proteins expressed by tumor cells. For even a small population, each individual may have hundreds or thousands of dimensions.