User login

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - January 2017

Scabies

BY JENNA BOROK AND LAWRENCE EICHENFIELD, MD

Frontline Medical News

The scabies mite or the “itch mite” was discovered in 1687 as the first identifiable microorganism that caused human disease.1 Scabies is an infection of the epidermis with the mite, Sarcoptes scabiei variety hominis (S. scabiei) affecting approximately 300 million people worldwide.2 It is a common disease, especially among school-aged children and is particularly rampant in areas of poor sanitation and overcrowding.2,3

S. scabiei live in and on human skin where the impregnated female mite burrows into the stratum corneum and lays two to three eggs daily for as long as 30 days.3,4 The egg becomes a larva, which leaves the burrow and molts into a nymph, and it continues to molt into a mature mite.3 Mating then occurs during the mite stage. After mating, the male mite dies and the female completes the life cycle by burrowing back into the stratum corneum; this process takes about 2 weeks.3,4

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on strong clinical suspicion. The chief complaint is often a generalized itching rash that is often worse at nighttime.3,6 Small inflammatory papules are the main physical exam finding, and they usually are widely distributed, the favored locations including the finger webs, wrists, elbows, axillae, girdle area, and feet.3 In addition, male genitalia oftentimes are involved, and small itching papules on the penis should be considered scabies until proven otherwise.3 The head almost always is spared except in infants, who may present with pustules on the palms and soles of the feet and vesicles or lesions on the neck and face.7

The pathognomonic exam finding is the mite’s burrow, which appears as a 2-5 mm white, superficial, threadlike line. Upon close inspection, a tiny black speck often can be seen at the end of the burrow, which represents the adult mite.3 The presence of mites, eggs, or feces also is diagnostic and is accomplished by a skin scraping with a No. 15 blade.3 A positive scraping is diagnostic, although a negative scraping does not rule out the condition. (We explain this to our patients by saying “If you call someone’s home phone and they answer the phone, you know they are home. If you call and there is no answer, it could be that they aren’t home, or they are home and just not answering.”) A biopsy usually is not required, but may provide a diagnosis when scabies is unsuspected.3

The differential for red papules that itch in children includes atopic dermatitis, impetigo, papular urticaria, contact dermatitis, and other infestations, including bites from mosquitoes, fleas, and bed bugs. Atopic dermatitis (AD) can present as eczematous, erythematous papular lesions with oozing in flexural areas similar to areas affected by scabies. However, there are no burrows seen in AD, and the lesions are not in the interdigital web spaces. Impetigo has erythematous vesiculopustular lesions that form honey-colored crusts. Papular urticaria may be a hypersensitivity reaction to another insect, and the urticarial lesions are usually on the exposed parts of extremities. Unlike scabies, there are no burrows and usually no symptomatic family members. Contact dermatitis can present with vesicular, bullous, and sometimes papular erythematous lesions. It occurs after exposure to an allergen and often has well-demarcated borders with geometric shapes.

Treatment

Few randomized control or head-to-head trials exist on scabies treatment.2 First-line treatment is permethrin 5% cream, which is applied to the entire body surface from the neck down in children, but includes the face and scalp in infants.8,9 It is applied at bedtime and is washed off in the morning, and a second application is recommended after 7 days.3,8 It can be used in infants 2 months of age and older, and in pregnant females.3 Household contacts should be treated too, and those who are asymptomatic only require one application of permethrin.3 Permethrin is effective and more cost effective than ivermectin. Oral ivermectin has been used to treat scabies with a dose of 0.2 mg/kg and then repeated 2 weeks later, but the safety in children under 15 kg has not been determined.9 Lindane is an alternative option and is not recommended as first-line therapy because of its toxicity. It only should be used if the patient cannot tolerate or failed the previously mentioned therapies, with particular concern in children less than 50 kg.8,9 Infants and young children should be treated with permethrin and not with lindane.8 Clothes and bed linens can be decontaminated by machine-washing at a hot temperature.3,8 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can be helpful post-treatment to minimize pruritus and secondary eczematous changes.9

References

1. Int J Dermatol. 1998 Aug;37(8):625-30.

3. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology, 5th edition (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2013).

4. BMJ. 2005 Sep 17;331(7517):619-22.

5. Br Med J. 1941 Sep 20;2(4211):405-6.

6. Lancet. 2006 May 27;367(9524):1767-74.

7. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(1):9-18.

8. MMWR June 5, 2015 / 64(RR3);1-137.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Borok is a medical student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Borok said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

Scabies

BY JENNA BOROK AND LAWRENCE EICHENFIELD, MD

Frontline Medical News

The scabies mite or the “itch mite” was discovered in 1687 as the first identifiable microorganism that caused human disease.1 Scabies is an infection of the epidermis with the mite, Sarcoptes scabiei variety hominis (S. scabiei) affecting approximately 300 million people worldwide.2 It is a common disease, especially among school-aged children and is particularly rampant in areas of poor sanitation and overcrowding.2,3

S. scabiei live in and on human skin where the impregnated female mite burrows into the stratum corneum and lays two to three eggs daily for as long as 30 days.3,4 The egg becomes a larva, which leaves the burrow and molts into a nymph, and it continues to molt into a mature mite.3 Mating then occurs during the mite stage. After mating, the male mite dies and the female completes the life cycle by burrowing back into the stratum corneum; this process takes about 2 weeks.3,4

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on strong clinical suspicion. The chief complaint is often a generalized itching rash that is often worse at nighttime.3,6 Small inflammatory papules are the main physical exam finding, and they usually are widely distributed, the favored locations including the finger webs, wrists, elbows, axillae, girdle area, and feet.3 In addition, male genitalia oftentimes are involved, and small itching papules on the penis should be considered scabies until proven otherwise.3 The head almost always is spared except in infants, who may present with pustules on the palms and soles of the feet and vesicles or lesions on the neck and face.7

The pathognomonic exam finding is the mite’s burrow, which appears as a 2-5 mm white, superficial, threadlike line. Upon close inspection, a tiny black speck often can be seen at the end of the burrow, which represents the adult mite.3 The presence of mites, eggs, or feces also is diagnostic and is accomplished by a skin scraping with a No. 15 blade.3 A positive scraping is diagnostic, although a negative scraping does not rule out the condition. (We explain this to our patients by saying “If you call someone’s home phone and they answer the phone, you know they are home. If you call and there is no answer, it could be that they aren’t home, or they are home and just not answering.”) A biopsy usually is not required, but may provide a diagnosis when scabies is unsuspected.3

The differential for red papules that itch in children includes atopic dermatitis, impetigo, papular urticaria, contact dermatitis, and other infestations, including bites from mosquitoes, fleas, and bed bugs. Atopic dermatitis (AD) can present as eczematous, erythematous papular lesions with oozing in flexural areas similar to areas affected by scabies. However, there are no burrows seen in AD, and the lesions are not in the interdigital web spaces. Impetigo has erythematous vesiculopustular lesions that form honey-colored crusts. Papular urticaria may be a hypersensitivity reaction to another insect, and the urticarial lesions are usually on the exposed parts of extremities. Unlike scabies, there are no burrows and usually no symptomatic family members. Contact dermatitis can present with vesicular, bullous, and sometimes papular erythematous lesions. It occurs after exposure to an allergen and often has well-demarcated borders with geometric shapes.

Treatment

Few randomized control or head-to-head trials exist on scabies treatment.2 First-line treatment is permethrin 5% cream, which is applied to the entire body surface from the neck down in children, but includes the face and scalp in infants.8,9 It is applied at bedtime and is washed off in the morning, and a second application is recommended after 7 days.3,8 It can be used in infants 2 months of age and older, and in pregnant females.3 Household contacts should be treated too, and those who are asymptomatic only require one application of permethrin.3 Permethrin is effective and more cost effective than ivermectin. Oral ivermectin has been used to treat scabies with a dose of 0.2 mg/kg and then repeated 2 weeks later, but the safety in children under 15 kg has not been determined.9 Lindane is an alternative option and is not recommended as first-line therapy because of its toxicity. It only should be used if the patient cannot tolerate or failed the previously mentioned therapies, with particular concern in children less than 50 kg.8,9 Infants and young children should be treated with permethrin and not with lindane.8 Clothes and bed linens can be decontaminated by machine-washing at a hot temperature.3,8 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can be helpful post-treatment to minimize pruritus and secondary eczematous changes.9

References

1. Int J Dermatol. 1998 Aug;37(8):625-30.

3. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology, 5th edition (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2013).

4. BMJ. 2005 Sep 17;331(7517):619-22.

5. Br Med J. 1941 Sep 20;2(4211):405-6.

6. Lancet. 2006 May 27;367(9524):1767-74.

7. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(1):9-18.

8. MMWR June 5, 2015 / 64(RR3);1-137.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Borok is a medical student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Borok said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

Scabies

BY JENNA BOROK AND LAWRENCE EICHENFIELD, MD

Frontline Medical News

The scabies mite or the “itch mite” was discovered in 1687 as the first identifiable microorganism that caused human disease.1 Scabies is an infection of the epidermis with the mite, Sarcoptes scabiei variety hominis (S. scabiei) affecting approximately 300 million people worldwide.2 It is a common disease, especially among school-aged children and is particularly rampant in areas of poor sanitation and overcrowding.2,3

S. scabiei live in and on human skin where the impregnated female mite burrows into the stratum corneum and lays two to three eggs daily for as long as 30 days.3,4 The egg becomes a larva, which leaves the burrow and molts into a nymph, and it continues to molt into a mature mite.3 Mating then occurs during the mite stage. After mating, the male mite dies and the female completes the life cycle by burrowing back into the stratum corneum; this process takes about 2 weeks.3,4

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on strong clinical suspicion. The chief complaint is often a generalized itching rash that is often worse at nighttime.3,6 Small inflammatory papules are the main physical exam finding, and they usually are widely distributed, the favored locations including the finger webs, wrists, elbows, axillae, girdle area, and feet.3 In addition, male genitalia oftentimes are involved, and small itching papules on the penis should be considered scabies until proven otherwise.3 The head almost always is spared except in infants, who may present with pustules on the palms and soles of the feet and vesicles or lesions on the neck and face.7

The pathognomonic exam finding is the mite’s burrow, which appears as a 2-5 mm white, superficial, threadlike line. Upon close inspection, a tiny black speck often can be seen at the end of the burrow, which represents the adult mite.3 The presence of mites, eggs, or feces also is diagnostic and is accomplished by a skin scraping with a No. 15 blade.3 A positive scraping is diagnostic, although a negative scraping does not rule out the condition. (We explain this to our patients by saying “If you call someone’s home phone and they answer the phone, you know they are home. If you call and there is no answer, it could be that they aren’t home, or they are home and just not answering.”) A biopsy usually is not required, but may provide a diagnosis when scabies is unsuspected.3

The differential for red papules that itch in children includes atopic dermatitis, impetigo, papular urticaria, contact dermatitis, and other infestations, including bites from mosquitoes, fleas, and bed bugs. Atopic dermatitis (AD) can present as eczematous, erythematous papular lesions with oozing in flexural areas similar to areas affected by scabies. However, there are no burrows seen in AD, and the lesions are not in the interdigital web spaces. Impetigo has erythematous vesiculopustular lesions that form honey-colored crusts. Papular urticaria may be a hypersensitivity reaction to another insect, and the urticarial lesions are usually on the exposed parts of extremities. Unlike scabies, there are no burrows and usually no symptomatic family members. Contact dermatitis can present with vesicular, bullous, and sometimes papular erythematous lesions. It occurs after exposure to an allergen and often has well-demarcated borders with geometric shapes.

Treatment

Few randomized control or head-to-head trials exist on scabies treatment.2 First-line treatment is permethrin 5% cream, which is applied to the entire body surface from the neck down in children, but includes the face and scalp in infants.8,9 It is applied at bedtime and is washed off in the morning, and a second application is recommended after 7 days.3,8 It can be used in infants 2 months of age and older, and in pregnant females.3 Household contacts should be treated too, and those who are asymptomatic only require one application of permethrin.3 Permethrin is effective and more cost effective than ivermectin. Oral ivermectin has been used to treat scabies with a dose of 0.2 mg/kg and then repeated 2 weeks later, but the safety in children under 15 kg has not been determined.9 Lindane is an alternative option and is not recommended as first-line therapy because of its toxicity. It only should be used if the patient cannot tolerate or failed the previously mentioned therapies, with particular concern in children less than 50 kg.8,9 Infants and young children should be treated with permethrin and not with lindane.8 Clothes and bed linens can be decontaminated by machine-washing at a hot temperature.3,8 Topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines can be helpful post-treatment to minimize pruritus and secondary eczematous changes.9

References

1. Int J Dermatol. 1998 Aug;37(8):625-30.

3. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology, 5th edition (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2013).

4. BMJ. 2005 Sep 17;331(7517):619-22.

5. Br Med J. 1941 Sep 20;2(4211):405-6.

6. Lancet. 2006 May 27;367(9524):1767-74.

7. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(1):9-18.

8. MMWR June 5, 2015 / 64(RR3);1-137.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Borok is a medical student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Borok said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

A 3-month-old boy presents to his physician for evaluation of a diffusely itchy rash. The rash started about 1 month ago and has been getting progressively worse; it is now very pruritic. The rash is diffuse, but includes the face, trunk, hands, and feet.

He is otherwise healthy and has no history of eczema or infections.

There are no animals at home. The infant was born at term with an unremarkable perinatal history.

FDA approves ibrutinib to treat rel/ref MZL

Photo courtesy of

Janssen Biotech, Inc.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) for the treatment of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

The drug is now approved to treat patients with relapsed/refractory MZL who require systemic therapy and have received at least 1 prior anti-CD20-based therapy.

Ibrutinib has accelerated approval for this indication, based on the overall response rate the drug produced in a phase 2 trial.

Continued approval of ibrutinib as a treatment for MZL may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

The FDA’s approval of ibrutinib for MZL makes it the first treatment approved specifically for patients with this disease. It also marks the seventh FDA approval and fifth disease indication for ibrutinib since the drug was first approved in 2013.

Ibrutinib is also FDA-approved to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, patients with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least 1 prior therapy, and patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. The approval for mantle cell lymphoma is an accelerated approval.

Ibrutinib is jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company, and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Phase 2 trial

The FDA’s approval of ibrutinib for MZL is based on data from the phase 2, single-arm PCYC-1121 study, in which researchers evaluated the drug in MZL patients who required systemic therapy and had received at least 1 prior anti-CD20-based therapy.

Results from this study were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1213).

The efficacy analysis included 63 patients with 3 subtypes of MZL: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (n=32), nodal (n=17), and splenic (n=14).

The overall response rate was 46%, with a partial response rate of 42.9% and a complete response rate of 3.2%. Responses were observed across all 3 MZL subtypes.

The median time to response was 4.5 months (range, 2.3-16.4 months). And the median duration of response was not reached (range, 16.7 months to not reached).

Overall, the safety data from this study was consistent with the known safety profile of ibrutinib in B-cell malignancies.

The most common adverse events of all grades (occurring in >20% of patients) were thrombocytopenia (49%), fatigue (44%), anemia (43%), diarrhea (43%), bruising (41%), musculoskeletal pain (40%), hemorrhage (30%), rash (29%), nausea (25%), peripheral edema (24%), arthralgia (24%), neutropenia (22%), cough (22%), dyspnea (21%), and upper respiratory tract infection (21%).

The most common (>10%) grade 3 or 4 events were decreases in hemoglobin and neutrophils (13% each) and pneumonia (10%).

The risks associated with ibrutinib as listed in the Warnings and Precautions section of the prescribing information are hemorrhage, infections, cytopenias, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, secondary primary malignancies, tumor lysis syndrome, and embryo fetal toxicities. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Janssen Biotech, Inc.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) for the treatment of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

The drug is now approved to treat patients with relapsed/refractory MZL who require systemic therapy and have received at least 1 prior anti-CD20-based therapy.

Ibrutinib has accelerated approval for this indication, based on the overall response rate the drug produced in a phase 2 trial.

Continued approval of ibrutinib as a treatment for MZL may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

The FDA’s approval of ibrutinib for MZL makes it the first treatment approved specifically for patients with this disease. It also marks the seventh FDA approval and fifth disease indication for ibrutinib since the drug was first approved in 2013.

Ibrutinib is also FDA-approved to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, patients with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least 1 prior therapy, and patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. The approval for mantle cell lymphoma is an accelerated approval.

Ibrutinib is jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company, and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Phase 2 trial

The FDA’s approval of ibrutinib for MZL is based on data from the phase 2, single-arm PCYC-1121 study, in which researchers evaluated the drug in MZL patients who required systemic therapy and had received at least 1 prior anti-CD20-based therapy.

Results from this study were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1213).

The efficacy analysis included 63 patients with 3 subtypes of MZL: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (n=32), nodal (n=17), and splenic (n=14).

The overall response rate was 46%, with a partial response rate of 42.9% and a complete response rate of 3.2%. Responses were observed across all 3 MZL subtypes.

The median time to response was 4.5 months (range, 2.3-16.4 months). And the median duration of response was not reached (range, 16.7 months to not reached).

Overall, the safety data from this study was consistent with the known safety profile of ibrutinib in B-cell malignancies.

The most common adverse events of all grades (occurring in >20% of patients) were thrombocytopenia (49%), fatigue (44%), anemia (43%), diarrhea (43%), bruising (41%), musculoskeletal pain (40%), hemorrhage (30%), rash (29%), nausea (25%), peripheral edema (24%), arthralgia (24%), neutropenia (22%), cough (22%), dyspnea (21%), and upper respiratory tract infection (21%).

The most common (>10%) grade 3 or 4 events were decreases in hemoglobin and neutrophils (13% each) and pneumonia (10%).

The risks associated with ibrutinib as listed in the Warnings and Precautions section of the prescribing information are hemorrhage, infections, cytopenias, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, secondary primary malignancies, tumor lysis syndrome, and embryo fetal toxicities. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Janssen Biotech, Inc.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) for the treatment of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

The drug is now approved to treat patients with relapsed/refractory MZL who require systemic therapy and have received at least 1 prior anti-CD20-based therapy.

Ibrutinib has accelerated approval for this indication, based on the overall response rate the drug produced in a phase 2 trial.

Continued approval of ibrutinib as a treatment for MZL may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

The FDA’s approval of ibrutinib for MZL makes it the first treatment approved specifically for patients with this disease. It also marks the seventh FDA approval and fifth disease indication for ibrutinib since the drug was first approved in 2013.

Ibrutinib is also FDA-approved to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, patients with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least 1 prior therapy, and patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. The approval for mantle cell lymphoma is an accelerated approval.

Ibrutinib is jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company, and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Phase 2 trial

The FDA’s approval of ibrutinib for MZL is based on data from the phase 2, single-arm PCYC-1121 study, in which researchers evaluated the drug in MZL patients who required systemic therapy and had received at least 1 prior anti-CD20-based therapy.

Results from this study were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 1213).

The efficacy analysis included 63 patients with 3 subtypes of MZL: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (n=32), nodal (n=17), and splenic (n=14).

The overall response rate was 46%, with a partial response rate of 42.9% and a complete response rate of 3.2%. Responses were observed across all 3 MZL subtypes.

The median time to response was 4.5 months (range, 2.3-16.4 months). And the median duration of response was not reached (range, 16.7 months to not reached).

Overall, the safety data from this study was consistent with the known safety profile of ibrutinib in B-cell malignancies.

The most common adverse events of all grades (occurring in >20% of patients) were thrombocytopenia (49%), fatigue (44%), anemia (43%), diarrhea (43%), bruising (41%), musculoskeletal pain (40%), hemorrhage (30%), rash (29%), nausea (25%), peripheral edema (24%), arthralgia (24%), neutropenia (22%), cough (22%), dyspnea (21%), and upper respiratory tract infection (21%).

The most common (>10%) grade 3 or 4 events were decreases in hemoglobin and neutrophils (13% each) and pneumonia (10%).

The risks associated with ibrutinib as listed in the Warnings and Precautions section of the prescribing information are hemorrhage, infections, cytopenias, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, secondary primary malignancies, tumor lysis syndrome, and embryo fetal toxicities. ![]()

PI ties to industry linked to positive trial results

capsules for a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Financial ties between principal investigators (PIs) and drug companies are independently associated with positive clinical trial results, according to new research.

The study showed a significant association between positive trial outcomes and PIs having financial ties to the manufacturer of the study drug, even after accounting for the source of research funding.

Researchers reported these findings in The BMJ.

Salomeh Keyhani, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues conducted this research, analyzing a random sample of 195 drug trials published in 2013.

The team found financial ties between PIs and manufacturers of the study drug for 67.7% of the studies (n=132). In all, 58% of the PIs had financial ties to the manufacturers (231/397).

Types of financial ties included:

- Advisor/consultancy payments (39%)

- Speakers’ fees (20%)

- Unspecified financial ties (20%)

- Honoraria (13%)

- Employee relationships (13%)

- Travel fees (13%)

- Stock ownership (10%)

- Having a patent related to the study drug (5%).

PIs reported financial ties to the drug manufacturer in 76% (103/136) of studies with positive results and 49% (29/59) of studies with negative results (P<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the study’s funding source, a financial tie was significantly associated with a positive trial outcome. The odds ratio was 3.57 (P=0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for a range of other study-related factors as well, a financial tie remained significantly associated with a positive trial outcome. The odds ratio was 3.37 (P=0.006).

Dr Keyhani and her colleagues stressed that this analysis was observational and cannot be used to draw conclusions about causation.

However, they said, given the importance of industry and academic collaboration in advancing the development of new treatments, “more thought needs to be given to the roles that investigators, policy makers, and journal editors can play in ensuring the credibility of the evidence base.”

Authors of a related editorial said more research is needed to determine how industry funding and financial ties could influence trial results.

The authors—Andreas Lundh, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, and Lisa Bero, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia—urged trial investigators to share their data and participate in industry-funded trials only if data are made publicly available.

The authors also suggested journals could help by rejecting research by investigators who are unwilling to share their data and by penalizing investigators who fail to disclose financial ties. The role of sponsors, or companies with which investigators have ties, in the research must also be transparent.

In the meantime, trials with industry funding or investigators with financial ties “should be interpreted with caution until all relevant information is fully disclosed and easily accessible,” the authors concluded. ![]()

capsules for a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Financial ties between principal investigators (PIs) and drug companies are independently associated with positive clinical trial results, according to new research.

The study showed a significant association between positive trial outcomes and PIs having financial ties to the manufacturer of the study drug, even after accounting for the source of research funding.

Researchers reported these findings in The BMJ.

Salomeh Keyhani, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues conducted this research, analyzing a random sample of 195 drug trials published in 2013.

The team found financial ties between PIs and manufacturers of the study drug for 67.7% of the studies (n=132). In all, 58% of the PIs had financial ties to the manufacturers (231/397).

Types of financial ties included:

- Advisor/consultancy payments (39%)

- Speakers’ fees (20%)

- Unspecified financial ties (20%)

- Honoraria (13%)

- Employee relationships (13%)

- Travel fees (13%)

- Stock ownership (10%)

- Having a patent related to the study drug (5%).

PIs reported financial ties to the drug manufacturer in 76% (103/136) of studies with positive results and 49% (29/59) of studies with negative results (P<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the study’s funding source, a financial tie was significantly associated with a positive trial outcome. The odds ratio was 3.57 (P=0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for a range of other study-related factors as well, a financial tie remained significantly associated with a positive trial outcome. The odds ratio was 3.37 (P=0.006).

Dr Keyhani and her colleagues stressed that this analysis was observational and cannot be used to draw conclusions about causation.

However, they said, given the importance of industry and academic collaboration in advancing the development of new treatments, “more thought needs to be given to the roles that investigators, policy makers, and journal editors can play in ensuring the credibility of the evidence base.”

Authors of a related editorial said more research is needed to determine how industry funding and financial ties could influence trial results.

The authors—Andreas Lundh, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, and Lisa Bero, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia—urged trial investigators to share their data and participate in industry-funded trials only if data are made publicly available.

The authors also suggested journals could help by rejecting research by investigators who are unwilling to share their data and by penalizing investigators who fail to disclose financial ties. The role of sponsors, or companies with which investigators have ties, in the research must also be transparent.

In the meantime, trials with industry funding or investigators with financial ties “should be interpreted with caution until all relevant information is fully disclosed and easily accessible,” the authors concluded. ![]()

capsules for a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Financial ties between principal investigators (PIs) and drug companies are independently associated with positive clinical trial results, according to new research.

The study showed a significant association between positive trial outcomes and PIs having financial ties to the manufacturer of the study drug, even after accounting for the source of research funding.

Researchers reported these findings in The BMJ.

Salomeh Keyhani, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues conducted this research, analyzing a random sample of 195 drug trials published in 2013.

The team found financial ties between PIs and manufacturers of the study drug for 67.7% of the studies (n=132). In all, 58% of the PIs had financial ties to the manufacturers (231/397).

Types of financial ties included:

- Advisor/consultancy payments (39%)

- Speakers’ fees (20%)

- Unspecified financial ties (20%)

- Honoraria (13%)

- Employee relationships (13%)

- Travel fees (13%)

- Stock ownership (10%)

- Having a patent related to the study drug (5%).

PIs reported financial ties to the drug manufacturer in 76% (103/136) of studies with positive results and 49% (29/59) of studies with negative results (P<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the study’s funding source, a financial tie was significantly associated with a positive trial outcome. The odds ratio was 3.57 (P=0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for a range of other study-related factors as well, a financial tie remained significantly associated with a positive trial outcome. The odds ratio was 3.37 (P=0.006).

Dr Keyhani and her colleagues stressed that this analysis was observational and cannot be used to draw conclusions about causation.

However, they said, given the importance of industry and academic collaboration in advancing the development of new treatments, “more thought needs to be given to the roles that investigators, policy makers, and journal editors can play in ensuring the credibility of the evidence base.”

Authors of a related editorial said more research is needed to determine how industry funding and financial ties could influence trial results.

The authors—Andreas Lundh, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, and Lisa Bero, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia—urged trial investigators to share their data and participate in industry-funded trials only if data are made publicly available.

The authors also suggested journals could help by rejecting research by investigators who are unwilling to share their data and by penalizing investigators who fail to disclose financial ties. The role of sponsors, or companies with which investigators have ties, in the research must also be transparent.

In the meantime, trials with industry funding or investigators with financial ties “should be interpreted with caution until all relevant information is fully disclosed and easily accessible,” the authors concluded. ![]()

US agencies update regulations on research subjects

tumor in a test tube

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and 15 other federal agencies have issued a final rule to update regulations intended to safeguard individuals who participate in research.

Most provisions in the new rule will go into effect in 2018.

The HHS says the new rule strengthens protections for people who volunteer to participate in research, while ensuring that the oversight system does not add inappropriate administrative burdens.

The current regulations, which have been in place since 1991, are often referred to as the “Common Rule.”

In September 2015, HHS and the other Common Rule agencies published a proposed new rule regarding research subjects—a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM)—which drew more than 2100 comments.

In response to concerns raised during the review process, the final rule contains a number of significant changes from the NPRM.

Research covered

The final rule does not cover clinical trials that are not federally funded.

The Common Rule has historically applied only to research conducted or supported by a Common Rule department or agency. And, although the NPRM proposed changing this policy, the final rule remains in line with the Common Rule.

Consent

The final rule requires consent forms to provide potential research subjects with a better understanding of a project’s scope so they can make a more fully informed decision about whether to participate.

Consent forms should include a concise explanation—at the beginning of the document—of the information that would be most important to individuals contemplating participation in a particular study, including the purpose of the research, the risks and benefits, and appropriate alternative treatments that might be beneficial to the prospective subject.

The rule also requires that consent forms for certain federally funded clinical trials be posted on a public website.

Institutional review boards

The final rule requires, in many cases, use of a single institutional review board (IRB) for multi-institutional research studies.

However, the final rule has been modified from the NPRM to add substantial increased flexibility in now allowing broad groups of studies (instead of just specific studies) to be removed from this requirement.

Privacy

The final rule does not include the standardized privacy safeguards for identifiable private information and identifiable biospecimens that were proposed in the NPRM.

In most respects, the final rule retains the current approach to privacy standards.

For studies on stored identifiable data or identifiable biospecimens, researchers will have the option of relying on broad consent obtained for future research as an alternative to seeking IRB approval to waive the consent requirement.

As under the current rule, researchers will not have to obtain consent for studies on non-identified stored data or biospecimens.

Exemptions

The final rule establishes new exempt categories of research based on the level of risk they pose to participants.

For example, to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden and allow IRBs to focus their attention on higher-risk studies, there is a new exemption for secondary research involving identifiable private information if the research is regulated by and participants are protected under the HIPAA rules.

Review

The final rule removes the requirement to conduct continuing review of ongoing research studies in certain instances where such review does little to protect subjects.

For more details, see the final rule. ![]()

tumor in a test tube

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and 15 other federal agencies have issued a final rule to update regulations intended to safeguard individuals who participate in research.

Most provisions in the new rule will go into effect in 2018.

The HHS says the new rule strengthens protections for people who volunteer to participate in research, while ensuring that the oversight system does not add inappropriate administrative burdens.

The current regulations, which have been in place since 1991, are often referred to as the “Common Rule.”

In September 2015, HHS and the other Common Rule agencies published a proposed new rule regarding research subjects—a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM)—which drew more than 2100 comments.

In response to concerns raised during the review process, the final rule contains a number of significant changes from the NPRM.

Research covered

The final rule does not cover clinical trials that are not federally funded.

The Common Rule has historically applied only to research conducted or supported by a Common Rule department or agency. And, although the NPRM proposed changing this policy, the final rule remains in line with the Common Rule.

Consent

The final rule requires consent forms to provide potential research subjects with a better understanding of a project’s scope so they can make a more fully informed decision about whether to participate.

Consent forms should include a concise explanation—at the beginning of the document—of the information that would be most important to individuals contemplating participation in a particular study, including the purpose of the research, the risks and benefits, and appropriate alternative treatments that might be beneficial to the prospective subject.

The rule also requires that consent forms for certain federally funded clinical trials be posted on a public website.

Institutional review boards

The final rule requires, in many cases, use of a single institutional review board (IRB) for multi-institutional research studies.

However, the final rule has been modified from the NPRM to add substantial increased flexibility in now allowing broad groups of studies (instead of just specific studies) to be removed from this requirement.

Privacy

The final rule does not include the standardized privacy safeguards for identifiable private information and identifiable biospecimens that were proposed in the NPRM.

In most respects, the final rule retains the current approach to privacy standards.

For studies on stored identifiable data or identifiable biospecimens, researchers will have the option of relying on broad consent obtained for future research as an alternative to seeking IRB approval to waive the consent requirement.

As under the current rule, researchers will not have to obtain consent for studies on non-identified stored data or biospecimens.

Exemptions

The final rule establishes new exempt categories of research based on the level of risk they pose to participants.

For example, to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden and allow IRBs to focus their attention on higher-risk studies, there is a new exemption for secondary research involving identifiable private information if the research is regulated by and participants are protected under the HIPAA rules.

Review

The final rule removes the requirement to conduct continuing review of ongoing research studies in certain instances where such review does little to protect subjects.

For more details, see the final rule. ![]()

tumor in a test tube

Photo by Rhoda Baer

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and 15 other federal agencies have issued a final rule to update regulations intended to safeguard individuals who participate in research.

Most provisions in the new rule will go into effect in 2018.

The HHS says the new rule strengthens protections for people who volunteer to participate in research, while ensuring that the oversight system does not add inappropriate administrative burdens.

The current regulations, which have been in place since 1991, are often referred to as the “Common Rule.”

In September 2015, HHS and the other Common Rule agencies published a proposed new rule regarding research subjects—a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM)—which drew more than 2100 comments.

In response to concerns raised during the review process, the final rule contains a number of significant changes from the NPRM.

Research covered

The final rule does not cover clinical trials that are not federally funded.

The Common Rule has historically applied only to research conducted or supported by a Common Rule department or agency. And, although the NPRM proposed changing this policy, the final rule remains in line with the Common Rule.

Consent

The final rule requires consent forms to provide potential research subjects with a better understanding of a project’s scope so they can make a more fully informed decision about whether to participate.

Consent forms should include a concise explanation—at the beginning of the document—of the information that would be most important to individuals contemplating participation in a particular study, including the purpose of the research, the risks and benefits, and appropriate alternative treatments that might be beneficial to the prospective subject.

The rule also requires that consent forms for certain federally funded clinical trials be posted on a public website.

Institutional review boards

The final rule requires, in many cases, use of a single institutional review board (IRB) for multi-institutional research studies.

However, the final rule has been modified from the NPRM to add substantial increased flexibility in now allowing broad groups of studies (instead of just specific studies) to be removed from this requirement.

Privacy

The final rule does not include the standardized privacy safeguards for identifiable private information and identifiable biospecimens that were proposed in the NPRM.

In most respects, the final rule retains the current approach to privacy standards.

For studies on stored identifiable data or identifiable biospecimens, researchers will have the option of relying on broad consent obtained for future research as an alternative to seeking IRB approval to waive the consent requirement.

As under the current rule, researchers will not have to obtain consent for studies on non-identified stored data or biospecimens.

Exemptions

The final rule establishes new exempt categories of research based on the level of risk they pose to participants.

For example, to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden and allow IRBs to focus their attention on higher-risk studies, there is a new exemption for secondary research involving identifiable private information if the research is regulated by and participants are protected under the HIPAA rules.

Review

The final rule removes the requirement to conduct continuing review of ongoing research studies in certain instances where such review does little to protect subjects.

For more details, see the final rule. ![]()

Group creates library of SCD-specific iPSCs

Photo from Salk Institute

Researchers have created an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) library intended to aid the study of sickle cell disease (SCD).

The library consists of iPSCs generated from blood samples taken from ethnically diverse SCD patients from around the world.

The researchers say these iPSCs can be used to create disease models, which may allow scientists to better understand how SCD occurs and develop and test new treatments for the disease.

As a complement to the library, the researchers also designed CRISPR/Cas gene editing tools to correct the sickle hemoglobin mutation.

The team described this work in Stem Cell Reports.

“Sickle cell disease affects millions of people worldwide and is an emerging global health burden,” said study author George Murphy, PhD, of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine in Massachusetts.

“iPSCs have the potential to revolutionize the way we study human development, model life-threatening diseases, and, eventually, treat patients.”

The researchers’ library includes SCD-specific iPSCs from patients of different ethnicities with different β-globin gene haplotypes and fetal hemoglobin levels.

The researchers generated 54 iPSC lines from blood samples collected from individuals of African American, Brazilian, and Saudi Arabian descent. Both genders were represented, as well as a range of ages (3 to 53 years of age).

Most of the cell lines in the library, along with accompanying genetic and hematologic data, are freely available via the WiCell website.

“In addition to the library, we’ve designed and are using gene editing tools to correct the sickle hemoglobin mutation using the stem cell lines,” said Gustavo Mostoslavsky, MD, PhD, also of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine.

“When coupled with corrected sickle cell disease-specific iPSCs, these tools could one day provide a functional cure for the disorder.” ![]()

Photo from Salk Institute

Researchers have created an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) library intended to aid the study of sickle cell disease (SCD).

The library consists of iPSCs generated from blood samples taken from ethnically diverse SCD patients from around the world.

The researchers say these iPSCs can be used to create disease models, which may allow scientists to better understand how SCD occurs and develop and test new treatments for the disease.

As a complement to the library, the researchers also designed CRISPR/Cas gene editing tools to correct the sickle hemoglobin mutation.

The team described this work in Stem Cell Reports.

“Sickle cell disease affects millions of people worldwide and is an emerging global health burden,” said study author George Murphy, PhD, of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine in Massachusetts.

“iPSCs have the potential to revolutionize the way we study human development, model life-threatening diseases, and, eventually, treat patients.”

The researchers’ library includes SCD-specific iPSCs from patients of different ethnicities with different β-globin gene haplotypes and fetal hemoglobin levels.

The researchers generated 54 iPSC lines from blood samples collected from individuals of African American, Brazilian, and Saudi Arabian descent. Both genders were represented, as well as a range of ages (3 to 53 years of age).

Most of the cell lines in the library, along with accompanying genetic and hematologic data, are freely available via the WiCell website.

“In addition to the library, we’ve designed and are using gene editing tools to correct the sickle hemoglobin mutation using the stem cell lines,” said Gustavo Mostoslavsky, MD, PhD, also of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine.

“When coupled with corrected sickle cell disease-specific iPSCs, these tools could one day provide a functional cure for the disorder.” ![]()

Photo from Salk Institute

Researchers have created an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) library intended to aid the study of sickle cell disease (SCD).

The library consists of iPSCs generated from blood samples taken from ethnically diverse SCD patients from around the world.

The researchers say these iPSCs can be used to create disease models, which may allow scientists to better understand how SCD occurs and develop and test new treatments for the disease.

As a complement to the library, the researchers also designed CRISPR/Cas gene editing tools to correct the sickle hemoglobin mutation.

The team described this work in Stem Cell Reports.

“Sickle cell disease affects millions of people worldwide and is an emerging global health burden,” said study author George Murphy, PhD, of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine in Massachusetts.

“iPSCs have the potential to revolutionize the way we study human development, model life-threatening diseases, and, eventually, treat patients.”

The researchers’ library includes SCD-specific iPSCs from patients of different ethnicities with different β-globin gene haplotypes and fetal hemoglobin levels.

The researchers generated 54 iPSC lines from blood samples collected from individuals of African American, Brazilian, and Saudi Arabian descent. Both genders were represented, as well as a range of ages (3 to 53 years of age).

Most of the cell lines in the library, along with accompanying genetic and hematologic data, are freely available via the WiCell website.

“In addition to the library, we’ve designed and are using gene editing tools to correct the sickle hemoglobin mutation using the stem cell lines,” said Gustavo Mostoslavsky, MD, PhD, also of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine.

“When coupled with corrected sickle cell disease-specific iPSCs, these tools could one day provide a functional cure for the disorder.” ![]()

The Importance of Subclavian Angiography in the Evaluation of Chest Pain: Coronary-Subclavian Steal Syndrome

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS) is a rare clinical entity with an incidence of 0.2% to 0.7%.1 Despite its scarcity, CSSS is a condition that can result in devastating clinical consequences, such as myocardial ischemia, ranging from angina to myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic cardiomyopathy.2

In 1974, Harjola and Valle first reported the angiographic and physiologic descriptions of CSSS in an asymptomatic patient who was found to have flow reversal in the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft in a follow-up coronary angiography performed 11 months after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).3 Because of the similarity in the pathophysiology of this condition with vertebral-subclavian steal syndrome, this clinical entity was named coronary-subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS).4,5

In steal-syndrome phenomena, there is a significant stenosis in the subclavian artery proximal to the origin of an arterial branch, either LIMA or vertebral artery, resulting in lower pressure in the distal subclavian artery. As a result, the negative pressure gradient might be sufficient to cause retrograde flow; consequently causing arterial branch “flow reversal,” and then “steal” flow from the organ—either heart or brain—supplied by that artery.3,6

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is caused by a reversal of flow in a previously constructed internal mammary artery (IMA)-coronary conduit graft. It typically results from hemodynamically significant subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the ipsilateral IMA. The reversal of flow will “steal” the blood from the coronary territory supplied by the IMA conduit.4,5 The absence of proximal subclavian artery stenosis does not preclude the presence of this syndrome; reversal in the IMA conduit can occur in association with upper extremity hemodialysis fistulae or anomalous connection of the left subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery in d-transposition of the great arteries.2 Although the stenosis is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic disease, other clinical entities, including Takayasu vasculitis, radiation, and giant cell arteritis, have been described.6 Patients with CSSS usually present with stable or unstable angina as well as arm claudication and various neurologic symptoms.5 The consequence of CSSS can include ischemic cardiomyopathy, acute MI,7 stroke, and death.5,8

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old man with a previous MI managed with CABG, permanent atrial fibrillation (AF), and moderate aortic stenosis presented to the ambulatory clinic with recurrent symptoms of stable angina despite being on maximal anti-anginal therapy. A coronary angiogram performed 4 years earlier had revealed significant left main artery disease and total occlusion of the right coronary artery.

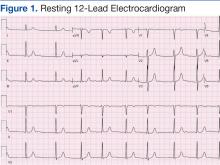

Cardiovascular examination revealed an irregular rhythm with a normal S1, variable S2, and a 3/6 systolic ejection murmur heard best at the right second intercostal space with radiation to the carotids. His peripheral pulses were equal and symmetric in the lower extremities, and no peripheral edema was noted. The remainder of the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram showed AF at a rate of 60 bpm (Figure 1).

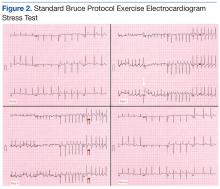

A stress test was performed to elucidate a possible coronary distribution for the cause of the chest pain.

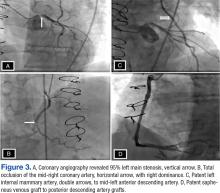

Consequently, coronary angiography was performed and showed 95% left main stenosis and total occlusion of the mid-right coronary artery with right dominance, patent LIMA to mid-LAD and patent saphenous venous graft to posterior descending artery grafts (Figure 3)

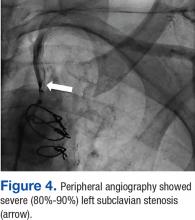

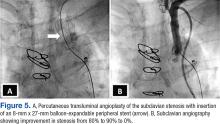

The patient underwent percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) of the subclavian stenosis with insertion of an 8 mm x 27 mm balloon-expandable peripheral stent (Figure 5) (Supplemental video 6). The patient tolerated the procedure well without complications and with resolution of his symptoms at a 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

Long-term follow-up of LIMA as a conduit to LAD has shown a 10-year patency of 95% compared with 76% for saphenous vein and an associated 10-year survival of 93.4% for LIMA compared with 88% for saphenous vein graft.9,10 Because of the superiority of LIMA outcomes, it has become the preferred graft in CABG. However, this approach is associated with 0.1% to 0.2% risk of ischemia related to flow reversal in the LIMA b

Greater awareness and improvement in diagnostic imaging have contributed to the increased incidence of CSSS and its consequences.2 Although symptoms related to myocardial ischemia, as in this case, are the most dominant in CSSS, other brachiocephalic symptoms, including vertebral-subclavian steal, transient ischemic attacks, and strokes, have been reported.11 Additionally, the same disease might compromise distal flow, resulting in extremity claudication or even distal microembolization.12

It is important to recognize that significant brachiocephalic stenosis has been reported in about 0.2% to 2.5% of patients undergoing elective CABG.6,8 Therefore, it is essential to screen for brachiocephalic artery disease before undergoing CABG. Different strategies have been suggested, including assessing pressure gradient between the upper extremities as the initial step; CSSS should be considered when the pressure gradient is > 20 mm Hg.

Other strategies include ultrasonic duplex scanning with provocation test using arm exercise or reactive hyperemia.13 Many high-volume centers are performing screening by proximal subclavian angiography in all patients undergoing coronary angiography. When significant disease is detected, arch aortography and 4-vessel cerebral angiography is performed.6 In addition, other centers have adopted the routine use of computerized tomographic angiography before CABG.14

Surgical correction of CSSS is considered to be the gold standard and can be accomplished by performing aorta-subclavian bypass, carotid-subclavian bypass, axillo-axillary bypass, or relocation of the IMA graft.2 Although this approach is invasive and carries many disadvantages related to patient comfort,surgical revascularization can be performed safely at the time of CABG and may not carry additional risk of morbidity or mortality.15 Moreover, surgical correction is the preferred modality for treatment of CSSS when the anatomy is not favorable for percutaneous intervention, such as chronic total occlusion of the subclavian artery.15Alternatively, CSSS can effectively be managed less invasively by percutaneous intervention, including PTA with stent placement,16,17 thrombectomy18 or atherectomy of the stenotic subclavian artery.19

In this patient, PTA was performed with primary stent placement. The lesion was crossed with a sheath, using combined femoral and radial access. After proper positioning, a balloon-expandable stent was deployed that resulted in complete angiographic resolution of the lesion and improvement of symptoms at 6-month follow-up. In line with previous reports, this case demonstrated that percutaneous intervention is a feasible and less invasive approach for management of CSSS.16,17 The effectiveness of the percutaneous approach has effectiveness equivalent to surgical bypass with minimal complications and good long-term success. Therefore, it has been suggested as first-line therapy in CSSS.8,16

Although preoperative screening for brachiocephalic disease before undergoing ipsilateral IMA coronary artery bypass can prevent the development of CSSS, there is controversy about the best approach for managing these concomitant conditions. Many institutions use all-vein coronary conduits, but that forgoes the benefit of a LIMA graft. Therefore, others still perform an IMA conduit after brachiocephalic reconstruction. An alternative method is to use free IMA or radial artery conduit. Currently, there are limited data about the use of endovascular treatment for brachiocephalic disease with a CABG.2

Conclusion

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is an important clinical condition that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the Sullivan and colleagues report of 27 patients with CSSS, 59.3% had stable angina and 40.7% had acute coronary syndrome, among which 14.8% presented with acute MI.7 Therefore, early recognition is essential to prevent catastrophic consequences.

Patients with CSSS usually present with cardiac symptoms, but symptoms related to vertebral-subclavian steal and posterior cerebral insufficiency can coexist. The authors suggest routine preoperative screening for the presence of brachiocephalic disease, using ultrasonic duplex or angiography. This practice is cost-effective and essential to prevent the development of CSSS. Optimal management of brachiocephalic disease prior to CABG is debatable; however, IMA grafting and reconstruction of the brachiocephalic system seems to be a promising approach.

When CSSS develops after CABG, the condition can be successfully treated with percutaneous intervention and outcomes comparable with those of surgical bypass.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the division of cardiology at New Jersey VA Health Care System, in particular Steve Tsai, MD; Ronald L. Vaillancourt, RN, and Preciosa Yap, RN.

1. Marques KM, Ernst SM, Mast EG, Bal ET, Suttorp MJ, Plokker HW. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the left subclavian artery to prevent or treat the coronary-subclavian steal syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(6):687-690.

2. Takach TJ, Reul GJ, Cooley DA, et al. Myocardial thievery: the coronary-subclavian steal syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(1):386-392.

3. Harjola PT, Valle M. The importance of aortic arch or subclavian angiography before coronary reconstruction. Chest. 1974;66(4):436-438.

4. Tyras DH, Barner HB. Coronary-subclavian steal. Arch Surg. 1977;112(9):1125-1127.

5. Brown AH. Coronary steal by internal mammary graft with subclavian stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73(5):690-693.

6. Takach TJ, Reul GJ, Duncan JM, et al. Concomitant brachiocephalic and coronary artery disease: outcome and decision analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(2):564-569.

7. Sullivan TM, Gray BH, Bacharach JM, et al. Angioplasty and primary stenting of the subclavian, innominate, and common carotid arteries in 83 patients. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28(6):1059-1065.

8. Hwang HY, Kim JH, Lee W, Park JH, Kim KB. Left subclavian artery stenosis in coronary artery bypass: prevalence and revascularization strategies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(4):1146-11 50.

9. Zeff RH, Kongtahworn C, Iannone LA, et al. Internal mammary artery versus saphenous vein graft to the left anterior descending coronary artery: prospective randomized study with 10-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg.1988;45(5):533-536.

10. Loop FD, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM, et al. Influence of the internal-mammary-artery graft on 10-year survival and other cardiac events. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(1):1-6.

11. Lee SR, Jeong MH, Rhew JY, et al. Simultaneous coronary-subclavian and vertebral-subclavian steal syndrome. Circ J. 2003;67(5):464-466.

12. Takach TJ, Beggs ML, Nykamp VJ, Reul GJ Jr. Concomitant cerebral and coronary subclavian steal. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63(3):853-854.

13. Branchereau A, Magnan PE, Espinoza H, Bartoli JM. Subclavian artery stenosis: hemodynamic aspects and surgical outcome. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1991;32(5):604-661.

14. Park KH, Lee HY, Lim C, et al. Clinical impact of computerised tomographic angiography performed for preoperative evaluation before coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37(6):1346-1352.

15. Sintek M, Coverstone E, Singh J. Coronary subclavian steal syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2014;29(6):506-513.

16. Eisenhauer AC. Subclavian and innominate revascularization: surgical therapy versus catheter-based intervention. Curr Interv Cardiol Rep. 2000;2(2):101-110.

17. Bates MC, Broce M, Lavigne PS, Stone P. Subclavian artery stenting: factors influencing long-term outcome. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;61(1):5-11.

18. Zeller T, Frank U, Burgelin K, Sinn L, Horn B, Roskamm H. Acute thrombotic subclavian artery occlusion treated with a new rotational thrombectomy device. J Endovasc Ther. 2002;9(6):917-921.

19. Breall JA, Grossman W, Stillman IE, Gianturco LE, Kim D. Atherectomy of the subclavian artery for patients with symptomatic coronary-subclavian steal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21(7):1564-1567.

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS) is a rare clinical entity with an incidence of 0.2% to 0.7%.1 Despite its scarcity, CSSS is a condition that can result in devastating clinical consequences, such as myocardial ischemia, ranging from angina to myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic cardiomyopathy.2

In 1974, Harjola and Valle first reported the angiographic and physiologic descriptions of CSSS in an asymptomatic patient who was found to have flow reversal in the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft in a follow-up coronary angiography performed 11 months after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).3 Because of the similarity in the pathophysiology of this condition with vertebral-subclavian steal syndrome, this clinical entity was named coronary-subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS).4,5

In steal-syndrome phenomena, there is a significant stenosis in the subclavian artery proximal to the origin of an arterial branch, either LIMA or vertebral artery, resulting in lower pressure in the distal subclavian artery. As a result, the negative pressure gradient might be sufficient to cause retrograde flow; consequently causing arterial branch “flow reversal,” and then “steal” flow from the organ—either heart or brain—supplied by that artery.3,6

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is caused by a reversal of flow in a previously constructed internal mammary artery (IMA)-coronary conduit graft. It typically results from hemodynamically significant subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the ipsilateral IMA. The reversal of flow will “steal” the blood from the coronary territory supplied by the IMA conduit.4,5 The absence of proximal subclavian artery stenosis does not preclude the presence of this syndrome; reversal in the IMA conduit can occur in association with upper extremity hemodialysis fistulae or anomalous connection of the left subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery in d-transposition of the great arteries.2 Although the stenosis is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic disease, other clinical entities, including Takayasu vasculitis, radiation, and giant cell arteritis, have been described.6 Patients with CSSS usually present with stable or unstable angina as well as arm claudication and various neurologic symptoms.5 The consequence of CSSS can include ischemic cardiomyopathy, acute MI,7 stroke, and death.5,8

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old man with a previous MI managed with CABG, permanent atrial fibrillation (AF), and moderate aortic stenosis presented to the ambulatory clinic with recurrent symptoms of stable angina despite being on maximal anti-anginal therapy. A coronary angiogram performed 4 years earlier had revealed significant left main artery disease and total occlusion of the right coronary artery.

Cardiovascular examination revealed an irregular rhythm with a normal S1, variable S2, and a 3/6 systolic ejection murmur heard best at the right second intercostal space with radiation to the carotids. His peripheral pulses were equal and symmetric in the lower extremities, and no peripheral edema was noted. The remainder of the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram showed AF at a rate of 60 bpm (Figure 1).

A stress test was performed to elucidate a possible coronary distribution for the cause of the chest pain.

Consequently, coronary angiography was performed and showed 95% left main stenosis and total occlusion of the mid-right coronary artery with right dominance, patent LIMA to mid-LAD and patent saphenous venous graft to posterior descending artery grafts (Figure 3)

The patient underwent percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) of the subclavian stenosis with insertion of an 8 mm x 27 mm balloon-expandable peripheral stent (Figure 5) (Supplemental video 6). The patient tolerated the procedure well without complications and with resolution of his symptoms at a 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

Long-term follow-up of LIMA as a conduit to LAD has shown a 10-year patency of 95% compared with 76% for saphenous vein and an associated 10-year survival of 93.4% for LIMA compared with 88% for saphenous vein graft.9,10 Because of the superiority of LIMA outcomes, it has become the preferred graft in CABG. However, this approach is associated with 0.1% to 0.2% risk of ischemia related to flow reversal in the LIMA b

Greater awareness and improvement in diagnostic imaging have contributed to the increased incidence of CSSS and its consequences.2 Although symptoms related to myocardial ischemia, as in this case, are the most dominant in CSSS, other brachiocephalic symptoms, including vertebral-subclavian steal, transient ischemic attacks, and strokes, have been reported.11 Additionally, the same disease might compromise distal flow, resulting in extremity claudication or even distal microembolization.12

It is important to recognize that significant brachiocephalic stenosis has been reported in about 0.2% to 2.5% of patients undergoing elective CABG.6,8 Therefore, it is essential to screen for brachiocephalic artery disease before undergoing CABG. Different strategies have been suggested, including assessing pressure gradient between the upper extremities as the initial step; CSSS should be considered when the pressure gradient is > 20 mm Hg.

Other strategies include ultrasonic duplex scanning with provocation test using arm exercise or reactive hyperemia.13 Many high-volume centers are performing screening by proximal subclavian angiography in all patients undergoing coronary angiography. When significant disease is detected, arch aortography and 4-vessel cerebral angiography is performed.6 In addition, other centers have adopted the routine use of computerized tomographic angiography before CABG.14

Surgical correction of CSSS is considered to be the gold standard and can be accomplished by performing aorta-subclavian bypass, carotid-subclavian bypass, axillo-axillary bypass, or relocation of the IMA graft.2 Although this approach is invasive and carries many disadvantages related to patient comfort,surgical revascularization can be performed safely at the time of CABG and may not carry additional risk of morbidity or mortality.15 Moreover, surgical correction is the preferred modality for treatment of CSSS when the anatomy is not favorable for percutaneous intervention, such as chronic total occlusion of the subclavian artery.15Alternatively, CSSS can effectively be managed less invasively by percutaneous intervention, including PTA with stent placement,16,17 thrombectomy18 or atherectomy of the stenotic subclavian artery.19

In this patient, PTA was performed with primary stent placement. The lesion was crossed with a sheath, using combined femoral and radial access. After proper positioning, a balloon-expandable stent was deployed that resulted in complete angiographic resolution of the lesion and improvement of symptoms at 6-month follow-up. In line with previous reports, this case demonstrated that percutaneous intervention is a feasible and less invasive approach for management of CSSS.16,17 The effectiveness of the percutaneous approach has effectiveness equivalent to surgical bypass with minimal complications and good long-term success. Therefore, it has been suggested as first-line therapy in CSSS.8,16

Although preoperative screening for brachiocephalic disease before undergoing ipsilateral IMA coronary artery bypass can prevent the development of CSSS, there is controversy about the best approach for managing these concomitant conditions. Many institutions use all-vein coronary conduits, but that forgoes the benefit of a LIMA graft. Therefore, others still perform an IMA conduit after brachiocephalic reconstruction. An alternative method is to use free IMA or radial artery conduit. Currently, there are limited data about the use of endovascular treatment for brachiocephalic disease with a CABG.2

Conclusion

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is an important clinical condition that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the Sullivan and colleagues report of 27 patients with CSSS, 59.3% had stable angina and 40.7% had acute coronary syndrome, among which 14.8% presented with acute MI.7 Therefore, early recognition is essential to prevent catastrophic consequences.

Patients with CSSS usually present with cardiac symptoms, but symptoms related to vertebral-subclavian steal and posterior cerebral insufficiency can coexist. The authors suggest routine preoperative screening for the presence of brachiocephalic disease, using ultrasonic duplex or angiography. This practice is cost-effective and essential to prevent the development of CSSS. Optimal management of brachiocephalic disease prior to CABG is debatable; however, IMA grafting and reconstruction of the brachiocephalic system seems to be a promising approach.

When CSSS develops after CABG, the condition can be successfully treated with percutaneous intervention and outcomes comparable with those of surgical bypass.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the division of cardiology at New Jersey VA Health Care System, in particular Steve Tsai, MD; Ronald L. Vaillancourt, RN, and Preciosa Yap, RN.

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS) is a rare clinical entity with an incidence of 0.2% to 0.7%.1 Despite its scarcity, CSSS is a condition that can result in devastating clinical consequences, such as myocardial ischemia, ranging from angina to myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic cardiomyopathy.2

In 1974, Harjola and Valle first reported the angiographic and physiologic descriptions of CSSS in an asymptomatic patient who was found to have flow reversal in the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft in a follow-up coronary angiography performed 11 months after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).3 Because of the similarity in the pathophysiology of this condition with vertebral-subclavian steal syndrome, this clinical entity was named coronary-subclavian steal syndrome (CSSS).4,5

In steal-syndrome phenomena, there is a significant stenosis in the subclavian artery proximal to the origin of an arterial branch, either LIMA or vertebral artery, resulting in lower pressure in the distal subclavian artery. As a result, the negative pressure gradient might be sufficient to cause retrograde flow; consequently causing arterial branch “flow reversal,” and then “steal” flow from the organ—either heart or brain—supplied by that artery.3,6

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is caused by a reversal of flow in a previously constructed internal mammary artery (IMA)-coronary conduit graft. It typically results from hemodynamically significant subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the ipsilateral IMA. The reversal of flow will “steal” the blood from the coronary territory supplied by the IMA conduit.4,5 The absence of proximal subclavian artery stenosis does not preclude the presence of this syndrome; reversal in the IMA conduit can occur in association with upper extremity hemodialysis fistulae or anomalous connection of the left subclavian artery to the pulmonary artery in d-transposition of the great arteries.2 Although the stenosis is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic disease, other clinical entities, including Takayasu vasculitis, radiation, and giant cell arteritis, have been described.6 Patients with CSSS usually present with stable or unstable angina as well as arm claudication and various neurologic symptoms.5 The consequence of CSSS can include ischemic cardiomyopathy, acute MI,7 stroke, and death.5,8

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old man with a previous MI managed with CABG, permanent atrial fibrillation (AF), and moderate aortic stenosis presented to the ambulatory clinic with recurrent symptoms of stable angina despite being on maximal anti-anginal therapy. A coronary angiogram performed 4 years earlier had revealed significant left main artery disease and total occlusion of the right coronary artery.

Cardiovascular examination revealed an irregular rhythm with a normal S1, variable S2, and a 3/6 systolic ejection murmur heard best at the right second intercostal space with radiation to the carotids. His peripheral pulses were equal and symmetric in the lower extremities, and no peripheral edema was noted. The remainder of the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram showed AF at a rate of 60 bpm (Figure 1).

A stress test was performed to elucidate a possible coronary distribution for the cause of the chest pain.

Consequently, coronary angiography was performed and showed 95% left main stenosis and total occlusion of the mid-right coronary artery with right dominance, patent LIMA to mid-LAD and patent saphenous venous graft to posterior descending artery grafts (Figure 3)

The patient underwent percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) of the subclavian stenosis with insertion of an 8 mm x 27 mm balloon-expandable peripheral stent (Figure 5) (Supplemental video 6). The patient tolerated the procedure well without complications and with resolution of his symptoms at a 6-month follow-up.

Discussion