User login

Vaccine candidate can protect humans from malaria

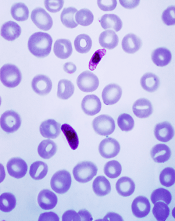

Plasmodium falciparum

Photo by Mae Melvin, CDC

In a phase 2 trial, a malaria vaccine candidate was able to prevent volunteers from contracting Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

The vaccine, known as PfSPZ vaccine, is composed of live but weakened P falciparum sporozoites.

Three to 5 doses of PfSPZ vaccine protected subjects against malaria parasites similar to those in the vaccine as well as parasites different from those in the vaccine.

A majority of subjects were protected at 3 weeks after vaccination. For some subjects, this protection was sustained at 24 weeks.

PfSPZ vaccine was considered well-tolerated, as all adverse events (AEs) in this trial were grade 1 or 2.

These results were published in JCI Insight.

The study was funded by the US Department of Defense through the Joint Warfighter Program, the Military Infectious Disease Research Program, and US Navy Advanced Medical Development, with additional support from Sanaria, Inc., the company developing PfSPZ vaccine.

“Our military continues to be at risk from malaria as it deploys worldwide,” said Kenneth A. Bertram, MD, of the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command in Ft Detrick, Maryland.

“We are excited about the results of this clinical trial and are now investing in the ongoing clinical trial to finalize the vaccination regimen for PfSPZ vaccine.”

The current trial included 67 volunteers with a median age of 29.6 (range, 19 to 45).

They were randomized to 3 treatment groups. Forty-five subjects were set to receive the PfSPZ vaccine, and 22 subjects served as controls.

The volunteers underwent controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) 3 weeks after vaccinated subjects received their final vaccine dose and then again at 24 weeks.

Efficacy at 3 weeks

Group 1

In this group, 13 subjects received 5 doses of the vaccine at 2.7 × 105. They and 6 control subjects underwent CHMI with a homologous strain of P falciparum, Pf3D7.

Twelve of the 13 fully immunized subjects, or 92.3%, did not develop parasitemia. However, all 6 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.6 days. The prepatent period in the immunized subject who developed parasitemia was 13.9 days.

Group 2

In this group, 5 subjects received 5 doses of the vaccine at 2.7 × 105. They and 4 control subjects underwent CHMI with a heterologous strain of P falciparum, Pf7G8.

Four of the 5 fully immunized subjects, or 80%, did not develop parasitemia. However, all 4 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.9 days. The prepatent period in the fully immunized subject who developed parasitemia was 11.9 days.

Group 3

In this group, 15 subjects received 3 doses of the vaccine at 4.5 × 105 and underwent homologous Pf3D7 CHMI. The control subjects for this group were the same as those in group 1.

Thirteen of the 15 immunized subjects, or 86.7%, did not develop parasitemia. The prepatent periods in the 2 immunized subjects who did develop parasitemia were 13.9 days and 16.9 days.

Efficacy at 24 weeks

Study subjects underwent a second CHMI at 24 weeks after immunized participants received their final dose of vaccine.

Group 1

Seven of the 10 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (70%). However, all 6 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.6 days. The median prepatent period in the 3 fully immunized subjects who developed parasitemia was 15.4 days.

Group 2

One of the 10 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (10%). However, all control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 10.9 days. The median prepatent period in the 9 fully immunized subjects who developed parasitemia was 11.9 days.

Group 3

Eight of the 14 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (57.1%). The median prepatent period in the 6 fully immunized subjects who did develop parasitemia was 14.0 days.

Safety

There were 66 solicited AEs reported within 7 days of immunization that were considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to vaccination. Ninety-two percent of these AEs were grade 1, and 8% were grade 2. All unsolicited AEs reported within 7 days of immunization were grade 1.

The incidence of AEs was not higher in group 3 than in groups 1 or 2, and the incidence of AEs did not increase as subjects received additional doses of the vaccine.

The most common AEs (with an incidence of 10% or higher in at least 1 group) were injection site pain, headache, fatigue, malaise, myalgia, injection site hemorrhage, and cough.

“The results of this clinical trial, along with recent results from other trials of this vaccine in the US and Africa, were critical to our decision to move forward with a trial involving 400 infants in Kenya,” said Tina Oneko, MD, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, who is the principal investigator of the Kenya trial but was not involved in the current trial.

“This represents significant progress toward the development of a regimen for PfSPZ vaccine that we anticipate will provide a high level [of] efficacy for malaria prevention in all age groups in Africa.” ![]()

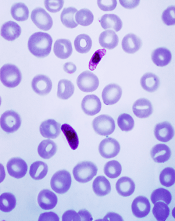

Plasmodium falciparum

Photo by Mae Melvin, CDC

In a phase 2 trial, a malaria vaccine candidate was able to prevent volunteers from contracting Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

The vaccine, known as PfSPZ vaccine, is composed of live but weakened P falciparum sporozoites.

Three to 5 doses of PfSPZ vaccine protected subjects against malaria parasites similar to those in the vaccine as well as parasites different from those in the vaccine.

A majority of subjects were protected at 3 weeks after vaccination. For some subjects, this protection was sustained at 24 weeks.

PfSPZ vaccine was considered well-tolerated, as all adverse events (AEs) in this trial were grade 1 or 2.

These results were published in JCI Insight.

The study was funded by the US Department of Defense through the Joint Warfighter Program, the Military Infectious Disease Research Program, and US Navy Advanced Medical Development, with additional support from Sanaria, Inc., the company developing PfSPZ vaccine.

“Our military continues to be at risk from malaria as it deploys worldwide,” said Kenneth A. Bertram, MD, of the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command in Ft Detrick, Maryland.

“We are excited about the results of this clinical trial and are now investing in the ongoing clinical trial to finalize the vaccination regimen for PfSPZ vaccine.”

The current trial included 67 volunteers with a median age of 29.6 (range, 19 to 45).

They were randomized to 3 treatment groups. Forty-five subjects were set to receive the PfSPZ vaccine, and 22 subjects served as controls.

The volunteers underwent controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) 3 weeks after vaccinated subjects received their final vaccine dose and then again at 24 weeks.

Efficacy at 3 weeks

Group 1

In this group, 13 subjects received 5 doses of the vaccine at 2.7 × 105. They and 6 control subjects underwent CHMI with a homologous strain of P falciparum, Pf3D7.

Twelve of the 13 fully immunized subjects, or 92.3%, did not develop parasitemia. However, all 6 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.6 days. The prepatent period in the immunized subject who developed parasitemia was 13.9 days.

Group 2

In this group, 5 subjects received 5 doses of the vaccine at 2.7 × 105. They and 4 control subjects underwent CHMI with a heterologous strain of P falciparum, Pf7G8.

Four of the 5 fully immunized subjects, or 80%, did not develop parasitemia. However, all 4 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.9 days. The prepatent period in the fully immunized subject who developed parasitemia was 11.9 days.

Group 3

In this group, 15 subjects received 3 doses of the vaccine at 4.5 × 105 and underwent homologous Pf3D7 CHMI. The control subjects for this group were the same as those in group 1.

Thirteen of the 15 immunized subjects, or 86.7%, did not develop parasitemia. The prepatent periods in the 2 immunized subjects who did develop parasitemia were 13.9 days and 16.9 days.

Efficacy at 24 weeks

Study subjects underwent a second CHMI at 24 weeks after immunized participants received their final dose of vaccine.

Group 1

Seven of the 10 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (70%). However, all 6 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.6 days. The median prepatent period in the 3 fully immunized subjects who developed parasitemia was 15.4 days.

Group 2

One of the 10 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (10%). However, all control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 10.9 days. The median prepatent period in the 9 fully immunized subjects who developed parasitemia was 11.9 days.

Group 3

Eight of the 14 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (57.1%). The median prepatent period in the 6 fully immunized subjects who did develop parasitemia was 14.0 days.

Safety

There were 66 solicited AEs reported within 7 days of immunization that were considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to vaccination. Ninety-two percent of these AEs were grade 1, and 8% were grade 2. All unsolicited AEs reported within 7 days of immunization were grade 1.

The incidence of AEs was not higher in group 3 than in groups 1 or 2, and the incidence of AEs did not increase as subjects received additional doses of the vaccine.

The most common AEs (with an incidence of 10% or higher in at least 1 group) were injection site pain, headache, fatigue, malaise, myalgia, injection site hemorrhage, and cough.

“The results of this clinical trial, along with recent results from other trials of this vaccine in the US and Africa, were critical to our decision to move forward with a trial involving 400 infants in Kenya,” said Tina Oneko, MD, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, who is the principal investigator of the Kenya trial but was not involved in the current trial.

“This represents significant progress toward the development of a regimen for PfSPZ vaccine that we anticipate will provide a high level [of] efficacy for malaria prevention in all age groups in Africa.” ![]()

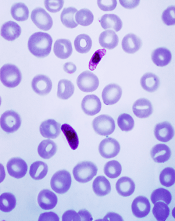

Plasmodium falciparum

Photo by Mae Melvin, CDC

In a phase 2 trial, a malaria vaccine candidate was able to prevent volunteers from contracting Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

The vaccine, known as PfSPZ vaccine, is composed of live but weakened P falciparum sporozoites.

Three to 5 doses of PfSPZ vaccine protected subjects against malaria parasites similar to those in the vaccine as well as parasites different from those in the vaccine.

A majority of subjects were protected at 3 weeks after vaccination. For some subjects, this protection was sustained at 24 weeks.

PfSPZ vaccine was considered well-tolerated, as all adverse events (AEs) in this trial were grade 1 or 2.

These results were published in JCI Insight.

The study was funded by the US Department of Defense through the Joint Warfighter Program, the Military Infectious Disease Research Program, and US Navy Advanced Medical Development, with additional support from Sanaria, Inc., the company developing PfSPZ vaccine.

“Our military continues to be at risk from malaria as it deploys worldwide,” said Kenneth A. Bertram, MD, of the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command in Ft Detrick, Maryland.

“We are excited about the results of this clinical trial and are now investing in the ongoing clinical trial to finalize the vaccination regimen for PfSPZ vaccine.”

The current trial included 67 volunteers with a median age of 29.6 (range, 19 to 45).

They were randomized to 3 treatment groups. Forty-five subjects were set to receive the PfSPZ vaccine, and 22 subjects served as controls.

The volunteers underwent controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) 3 weeks after vaccinated subjects received their final vaccine dose and then again at 24 weeks.

Efficacy at 3 weeks

Group 1

In this group, 13 subjects received 5 doses of the vaccine at 2.7 × 105. They and 6 control subjects underwent CHMI with a homologous strain of P falciparum, Pf3D7.

Twelve of the 13 fully immunized subjects, or 92.3%, did not develop parasitemia. However, all 6 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.6 days. The prepatent period in the immunized subject who developed parasitemia was 13.9 days.

Group 2

In this group, 5 subjects received 5 doses of the vaccine at 2.7 × 105. They and 4 control subjects underwent CHMI with a heterologous strain of P falciparum, Pf7G8.

Four of the 5 fully immunized subjects, or 80%, did not develop parasitemia. However, all 4 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.9 days. The prepatent period in the fully immunized subject who developed parasitemia was 11.9 days.

Group 3

In this group, 15 subjects received 3 doses of the vaccine at 4.5 × 105 and underwent homologous Pf3D7 CHMI. The control subjects for this group were the same as those in group 1.

Thirteen of the 15 immunized subjects, or 86.7%, did not develop parasitemia. The prepatent periods in the 2 immunized subjects who did develop parasitemia were 13.9 days and 16.9 days.

Efficacy at 24 weeks

Study subjects underwent a second CHMI at 24 weeks after immunized participants received their final dose of vaccine.

Group 1

Seven of the 10 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (70%). However, all 6 control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 11.6 days. The median prepatent period in the 3 fully immunized subjects who developed parasitemia was 15.4 days.

Group 2

One of the 10 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (10%). However, all control subjects did, with a median prepatent period of 10.9 days. The median prepatent period in the 9 fully immunized subjects who developed parasitemia was 11.9 days.

Group 3

Eight of the 14 fully immunized subjects who underwent a second CHMI did not develop parasitemia (57.1%). The median prepatent period in the 6 fully immunized subjects who did develop parasitemia was 14.0 days.

Safety

There were 66 solicited AEs reported within 7 days of immunization that were considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to vaccination. Ninety-two percent of these AEs were grade 1, and 8% were grade 2. All unsolicited AEs reported within 7 days of immunization were grade 1.

The incidence of AEs was not higher in group 3 than in groups 1 or 2, and the incidence of AEs did not increase as subjects received additional doses of the vaccine.

The most common AEs (with an incidence of 10% or higher in at least 1 group) were injection site pain, headache, fatigue, malaise, myalgia, injection site hemorrhage, and cough.

“The results of this clinical trial, along with recent results from other trials of this vaccine in the US and Africa, were critical to our decision to move forward with a trial involving 400 infants in Kenya,” said Tina Oneko, MD, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, who is the principal investigator of the Kenya trial but was not involved in the current trial.

“This represents significant progress toward the development of a regimen for PfSPZ vaccine that we anticipate will provide a high level [of] efficacy for malaria prevention in all age groups in Africa.” ![]()

High-flow oxygen noninferior to noninvasive ventilation postextubation

Clinical Question: Is high-flow oxygen noninferior to noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in preventing postextubation respiratory failure and reintubation?

Background: Studies that suggest NIV usage following extubation reduces the risk of postextubation respiratory failure have led to an increase in use of this practice. Compared with NIV, high-flow, conditioned oxygen therapy has many advantages and fewer adverse effects, suggesting it might be a useful alternative.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Three ICUs in Spain.

Rates of most secondary outcomes, including infection, mortality, and hospital length of stay (LOS) were similar between the two groups. ICU LOS was significantly less in the high-flow oxygen group (3d vs. 4d; 95% CI, –6.8 to –0.8).

Additionally, every patient tolerated high-flow oxygen therapy, while 40% of patients in the NIV arm required withdrawal of therapy for at least 6 hours due to adverse effects (P less than .001).

Bottom line: High-flow oxygen immediately following extubation may be a useful alternative to NIV in preventing postextubation respiratory failure.

Citation: Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-61.

Dr. Murphy is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical Question: Is high-flow oxygen noninferior to noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in preventing postextubation respiratory failure and reintubation?

Background: Studies that suggest NIV usage following extubation reduces the risk of postextubation respiratory failure have led to an increase in use of this practice. Compared with NIV, high-flow, conditioned oxygen therapy has many advantages and fewer adverse effects, suggesting it might be a useful alternative.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Three ICUs in Spain.

Rates of most secondary outcomes, including infection, mortality, and hospital length of stay (LOS) were similar between the two groups. ICU LOS was significantly less in the high-flow oxygen group (3d vs. 4d; 95% CI, –6.8 to –0.8).

Additionally, every patient tolerated high-flow oxygen therapy, while 40% of patients in the NIV arm required withdrawal of therapy for at least 6 hours due to adverse effects (P less than .001).

Bottom line: High-flow oxygen immediately following extubation may be a useful alternative to NIV in preventing postextubation respiratory failure.

Citation: Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-61.

Dr. Murphy is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical Question: Is high-flow oxygen noninferior to noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in preventing postextubation respiratory failure and reintubation?

Background: Studies that suggest NIV usage following extubation reduces the risk of postextubation respiratory failure have led to an increase in use of this practice. Compared with NIV, high-flow, conditioned oxygen therapy has many advantages and fewer adverse effects, suggesting it might be a useful alternative.

Study design: Randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Three ICUs in Spain.

Rates of most secondary outcomes, including infection, mortality, and hospital length of stay (LOS) were similar between the two groups. ICU LOS was significantly less in the high-flow oxygen group (3d vs. 4d; 95% CI, –6.8 to –0.8).

Additionally, every patient tolerated high-flow oxygen therapy, while 40% of patients in the NIV arm required withdrawal of therapy for at least 6 hours due to adverse effects (P less than .001).

Bottom line: High-flow oxygen immediately following extubation may be a useful alternative to NIV in preventing postextubation respiratory failure.

Citation: Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-61.

Dr. Murphy is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clonal hematopoiesis increases risk for therapy-related cancers

Small pre-leukemic clones left behind after treatment for non-myeloid malignancies appear to increase the risk for therapy-related myelodysplasia or leukemia, report investigators in two studies.

An analysis of peripheral blood samples taken from patients at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis and bone marrow samples taken at the time of a later therapy-related myeloid neoplasm diagnosis showed that 10 of 14 patients (71%) had clonal hematopoiesis before starting on cytotoxic chemotherapy. In contrast, clonal hematopoiesis was detected in pre-treatment samples of only 17 of 54 controls (31%), reported Koichi Takahashi, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Preleukemic clonal hematopoiesis is common in patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis and before they have been exposed to treatment. Our results suggest that clonal hematopoiesis could be used as a predictive marker to identify patients with cancer who are at risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms,” they wrote (Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 100–11).

In a separate study, investigators from the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, found in a nested case-control study that patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms were more likely than controls to have clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), and that the CHIP was often present before exposure to chemotherapy.

“We recorded a significantly higher prevalence of CHIP in individuals who developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (cases) than in those who did not (controls); however, around 27% of individuals with CHIP did not develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, suggesting that this feature alone should not be used to determine a patient’s suitability for chemotherapy,” wrote Nancy K. Gillis, PharmD, and colleagues (Lancet Oncol 2017; 18:112-21).

Risk factors examined

Dr. Takahashi and colleagues noted that previous studies have identified several treatment-related risk factors as being associated with therapy-related myeloid dysplasia or leukemia, including the use of alkylating agents, topoisomerase II inhibitors, and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation.

“By contrast, little is known about patient-specific risk factors. Older age was shown to increase the risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Several germline polymorphisms have also been associated with this risk, but none have been validated. As such, no predictive biomarkers exist for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms,” they wrote.

They performed a retrospective case-control study comparing patients treated for a primary cancer at their center from 1997 through 2015 who subsequently developed a myeloid neoplasm with controls treated during the same period. Controls were age-matched patients treated with combination chemotherapy for lymphoma who did not develop a therapy-related myeloid malignancy after at least 5 years of follow-up.

In addition, the investigators further explored the association between clonal hematopoiesis and therapy-related cancers in an external cohort of patients with lymphoma treated in a randomized trial at their center from 1999 through 2001. That trial compared the CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) with and without melatonin.

To detect clonal hematopoiesis in pre-treatment peripheral blood, the investigators used molecular barcode sequencing of 32 genes. They also used targeted gene sequencing on bone marrow samples from cases to investigate clonal evolution from clonal hematopoiesis to the development of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.

As noted before, 10 of 14 cases had evidence of pre-treatment clonal hematopoiesis, compared with 17 of 54 controls. For both cases and controls, the cumulative incidence of therapy-related myeloid cancers after 5 years was significantly higher among those with baseline clonal hematopoiesis, at 30% vs. 7% for patients without it (P = .016).

Five of 74 patients in the external cohort (7%) went on to develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, and of this group, four (80%) had clonal hematopoiesis at baseline. In contrast, of the 69 patients who did not develop therapy-related cancers, 11 (16%) had baseline clonal hematopoiesis.

In a multivariate model using data from the external cohort, clonal hematopoiesis was significantly associated with risk for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, with a hazard ratio of 13.7 (P = .013).

Elderly patient study

Dr. Gillis and her colleagues conducted a nested, case-control, proof-of-concept study to compare the prevalence of CHIP between patients with cancer who later developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (cases) and patients who did not (controls).

The cases were identified from an internal biobank of 123,357 patients, and included all patients who were diagnosed with a primary cancer, treated with chemotherapy, and subsequently developed a therapy-related myeloid neoplasm. The patients had to be 70 or older at the time of either primary or therapy-related cancer diagnosis with peripheral blood or mononuclear samples collected before the diagnosis of the second cancer.

Controls were patients diagnosed with a primary malignancy at age 70 or older who had chemotherapy but did not develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Every case was matched with at least four controls selected for sex, primary tumor type, age at diagnosis, smoking status, chemotherapy drug class, and duration of follow up.

They used sequential targeted and whole-exome sequencing to assess clonal evolution in cases for whom paired CHIP and therapy-related myeloid neoplasm samples were available.

They identified a total of 13 cases and 56 controls. Among all patients, CHIP was seen in 23 (33%). In contrast, previous studies have shown a prevalence of CHIP among older patients without cancer of about 10%, the authors note in their article.

The prevalence of CHIP was significantly higher among cases than among controls, occurring in 8 of 13 cases (62%) vs 15 of 56 controls (27%; P = .024). The odds ratio for therapy-related neoplasms with CHIP was 5.75 (P = .013).

The most commonly mutated genes were TET2 and TP53 among cases, and TET2 among controls.

“The distribution of CHIP-related gene mutations differs between individuals with therapy-related myeloid neoplasm and those without, suggesting that mutation-specific differences might exist in therapy-related myeloid neoplasm risk,” the investigators write.

Dr. Takahashi’s study was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, Red and Charline McCombs Institute for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cancer, The National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant, and the MD Anderson MDS & AML Moon Shots Program. Dr. Gillis’ study was internally funded. Dr. Takahasi and colleagues reported no competing financial interests. Two of Dr. Gillis’ colleagues reported grants or fees from several drug companies.

The real importance of the work reported by Gillis and colleagues and Takahashi and colleagues will come when therapies exist that can effectively eradicate nascent clonal hematopoiesis, thereby preventing therapy-related myeloid neoplasm evolution in at-risk patients.

Although high-intensity treatments, such as anthracycline-based induction chemotherapy, can eradicate myeloid clones, their effectiveness in clearing TP53-mutant cells is limited, and it is difficult to imagine intense approaches having a favorable risk–benefit balance in patients whose clonal hematopoiesis might never become a problem. Existing lower-intensity therapies for myeloid neoplasms such as DNA hypomethylating agents are not curative and often do not result in the reduction of VAF [variant allele frequencies] even when hematopoietic improvement occurs during therapy, so such agents would not be expected to eliminate pre-therapy-related myeloid neoplasm clones (although this hypothesis might still be worth testing, given that the emergence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasm could at least be delayed – even if not entirely prevented – with azacitidine or decitabine).

More promising are strategies that change the bone marrow microenvironment or break the immune tolerance of abnormal clones, although the use of these approaches for myeloid neoplasia is still in the very early stages. Although no method yet exists to reliably eliminate the preleukemic clones that can give rise to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, identification of higher risk patients could still affect monitoring practices, such as the frequency of clinical assessments. Molecular genetic panels are expensive at present but are becoming less so. Because VAF assessment by next-generation sequencing is quantitative and proportional to clone size, serial assessment could identify patients whose mutant clones are large and expanding and who therefore warrant closer monitoring or enrollment in so-called preventive hematology trials.

David P. Steensma, MD, is with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston. His remarks were excerpted from an accompanying editorial.

The real importance of the work reported by Gillis and colleagues and Takahashi and colleagues will come when therapies exist that can effectively eradicate nascent clonal hematopoiesis, thereby preventing therapy-related myeloid neoplasm evolution in at-risk patients.

Although high-intensity treatments, such as anthracycline-based induction chemotherapy, can eradicate myeloid clones, their effectiveness in clearing TP53-mutant cells is limited, and it is difficult to imagine intense approaches having a favorable risk–benefit balance in patients whose clonal hematopoiesis might never become a problem. Existing lower-intensity therapies for myeloid neoplasms such as DNA hypomethylating agents are not curative and often do not result in the reduction of VAF [variant allele frequencies] even when hematopoietic improvement occurs during therapy, so such agents would not be expected to eliminate pre-therapy-related myeloid neoplasm clones (although this hypothesis might still be worth testing, given that the emergence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasm could at least be delayed – even if not entirely prevented – with azacitidine or decitabine).

More promising are strategies that change the bone marrow microenvironment or break the immune tolerance of abnormal clones, although the use of these approaches for myeloid neoplasia is still in the very early stages. Although no method yet exists to reliably eliminate the preleukemic clones that can give rise to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, identification of higher risk patients could still affect monitoring practices, such as the frequency of clinical assessments. Molecular genetic panels are expensive at present but are becoming less so. Because VAF assessment by next-generation sequencing is quantitative and proportional to clone size, serial assessment could identify patients whose mutant clones are large and expanding and who therefore warrant closer monitoring or enrollment in so-called preventive hematology trials.

David P. Steensma, MD, is with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston. His remarks were excerpted from an accompanying editorial.

The real importance of the work reported by Gillis and colleagues and Takahashi and colleagues will come when therapies exist that can effectively eradicate nascent clonal hematopoiesis, thereby preventing therapy-related myeloid neoplasm evolution in at-risk patients.

Although high-intensity treatments, such as anthracycline-based induction chemotherapy, can eradicate myeloid clones, their effectiveness in clearing TP53-mutant cells is limited, and it is difficult to imagine intense approaches having a favorable risk–benefit balance in patients whose clonal hematopoiesis might never become a problem. Existing lower-intensity therapies for myeloid neoplasms such as DNA hypomethylating agents are not curative and often do not result in the reduction of VAF [variant allele frequencies] even when hematopoietic improvement occurs during therapy, so such agents would not be expected to eliminate pre-therapy-related myeloid neoplasm clones (although this hypothesis might still be worth testing, given that the emergence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasm could at least be delayed – even if not entirely prevented – with azacitidine or decitabine).

More promising are strategies that change the bone marrow microenvironment or break the immune tolerance of abnormal clones, although the use of these approaches for myeloid neoplasia is still in the very early stages. Although no method yet exists to reliably eliminate the preleukemic clones that can give rise to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, identification of higher risk patients could still affect monitoring practices, such as the frequency of clinical assessments. Molecular genetic panels are expensive at present but are becoming less so. Because VAF assessment by next-generation sequencing is quantitative and proportional to clone size, serial assessment could identify patients whose mutant clones are large and expanding and who therefore warrant closer monitoring or enrollment in so-called preventive hematology trials.

David P. Steensma, MD, is with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston. His remarks were excerpted from an accompanying editorial.

Small pre-leukemic clones left behind after treatment for non-myeloid malignancies appear to increase the risk for therapy-related myelodysplasia or leukemia, report investigators in two studies.

An analysis of peripheral blood samples taken from patients at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis and bone marrow samples taken at the time of a later therapy-related myeloid neoplasm diagnosis showed that 10 of 14 patients (71%) had clonal hematopoiesis before starting on cytotoxic chemotherapy. In contrast, clonal hematopoiesis was detected in pre-treatment samples of only 17 of 54 controls (31%), reported Koichi Takahashi, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Preleukemic clonal hematopoiesis is common in patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis and before they have been exposed to treatment. Our results suggest that clonal hematopoiesis could be used as a predictive marker to identify patients with cancer who are at risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms,” they wrote (Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 100–11).

In a separate study, investigators from the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, found in a nested case-control study that patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms were more likely than controls to have clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), and that the CHIP was often present before exposure to chemotherapy.

“We recorded a significantly higher prevalence of CHIP in individuals who developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (cases) than in those who did not (controls); however, around 27% of individuals with CHIP did not develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, suggesting that this feature alone should not be used to determine a patient’s suitability for chemotherapy,” wrote Nancy K. Gillis, PharmD, and colleagues (Lancet Oncol 2017; 18:112-21).

Risk factors examined

Dr. Takahashi and colleagues noted that previous studies have identified several treatment-related risk factors as being associated with therapy-related myeloid dysplasia or leukemia, including the use of alkylating agents, topoisomerase II inhibitors, and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation.

“By contrast, little is known about patient-specific risk factors. Older age was shown to increase the risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Several germline polymorphisms have also been associated with this risk, but none have been validated. As such, no predictive biomarkers exist for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms,” they wrote.

They performed a retrospective case-control study comparing patients treated for a primary cancer at their center from 1997 through 2015 who subsequently developed a myeloid neoplasm with controls treated during the same period. Controls were age-matched patients treated with combination chemotherapy for lymphoma who did not develop a therapy-related myeloid malignancy after at least 5 years of follow-up.

In addition, the investigators further explored the association between clonal hematopoiesis and therapy-related cancers in an external cohort of patients with lymphoma treated in a randomized trial at their center from 1999 through 2001. That trial compared the CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) with and without melatonin.

To detect clonal hematopoiesis in pre-treatment peripheral blood, the investigators used molecular barcode sequencing of 32 genes. They also used targeted gene sequencing on bone marrow samples from cases to investigate clonal evolution from clonal hematopoiesis to the development of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.

As noted before, 10 of 14 cases had evidence of pre-treatment clonal hematopoiesis, compared with 17 of 54 controls. For both cases and controls, the cumulative incidence of therapy-related myeloid cancers after 5 years was significantly higher among those with baseline clonal hematopoiesis, at 30% vs. 7% for patients without it (P = .016).

Five of 74 patients in the external cohort (7%) went on to develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, and of this group, four (80%) had clonal hematopoiesis at baseline. In contrast, of the 69 patients who did not develop therapy-related cancers, 11 (16%) had baseline clonal hematopoiesis.

In a multivariate model using data from the external cohort, clonal hematopoiesis was significantly associated with risk for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, with a hazard ratio of 13.7 (P = .013).

Elderly patient study

Dr. Gillis and her colleagues conducted a nested, case-control, proof-of-concept study to compare the prevalence of CHIP between patients with cancer who later developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (cases) and patients who did not (controls).

The cases were identified from an internal biobank of 123,357 patients, and included all patients who were diagnosed with a primary cancer, treated with chemotherapy, and subsequently developed a therapy-related myeloid neoplasm. The patients had to be 70 or older at the time of either primary or therapy-related cancer diagnosis with peripheral blood or mononuclear samples collected before the diagnosis of the second cancer.

Controls were patients diagnosed with a primary malignancy at age 70 or older who had chemotherapy but did not develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Every case was matched with at least four controls selected for sex, primary tumor type, age at diagnosis, smoking status, chemotherapy drug class, and duration of follow up.

They used sequential targeted and whole-exome sequencing to assess clonal evolution in cases for whom paired CHIP and therapy-related myeloid neoplasm samples were available.

They identified a total of 13 cases and 56 controls. Among all patients, CHIP was seen in 23 (33%). In contrast, previous studies have shown a prevalence of CHIP among older patients without cancer of about 10%, the authors note in their article.

The prevalence of CHIP was significantly higher among cases than among controls, occurring in 8 of 13 cases (62%) vs 15 of 56 controls (27%; P = .024). The odds ratio for therapy-related neoplasms with CHIP was 5.75 (P = .013).

The most commonly mutated genes were TET2 and TP53 among cases, and TET2 among controls.

“The distribution of CHIP-related gene mutations differs between individuals with therapy-related myeloid neoplasm and those without, suggesting that mutation-specific differences might exist in therapy-related myeloid neoplasm risk,” the investigators write.

Dr. Takahashi’s study was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, Red and Charline McCombs Institute for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cancer, The National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant, and the MD Anderson MDS & AML Moon Shots Program. Dr. Gillis’ study was internally funded. Dr. Takahasi and colleagues reported no competing financial interests. Two of Dr. Gillis’ colleagues reported grants or fees from several drug companies.

Small pre-leukemic clones left behind after treatment for non-myeloid malignancies appear to increase the risk for therapy-related myelodysplasia or leukemia, report investigators in two studies.

An analysis of peripheral blood samples taken from patients at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis and bone marrow samples taken at the time of a later therapy-related myeloid neoplasm diagnosis showed that 10 of 14 patients (71%) had clonal hematopoiesis before starting on cytotoxic chemotherapy. In contrast, clonal hematopoiesis was detected in pre-treatment samples of only 17 of 54 controls (31%), reported Koichi Takahashi, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Preleukemic clonal hematopoiesis is common in patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis and before they have been exposed to treatment. Our results suggest that clonal hematopoiesis could be used as a predictive marker to identify patients with cancer who are at risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms,” they wrote (Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 100–11).

In a separate study, investigators from the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, found in a nested case-control study that patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms were more likely than controls to have clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), and that the CHIP was often present before exposure to chemotherapy.

“We recorded a significantly higher prevalence of CHIP in individuals who developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (cases) than in those who did not (controls); however, around 27% of individuals with CHIP did not develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, suggesting that this feature alone should not be used to determine a patient’s suitability for chemotherapy,” wrote Nancy K. Gillis, PharmD, and colleagues (Lancet Oncol 2017; 18:112-21).

Risk factors examined

Dr. Takahashi and colleagues noted that previous studies have identified several treatment-related risk factors as being associated with therapy-related myeloid dysplasia or leukemia, including the use of alkylating agents, topoisomerase II inhibitors, and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation.

“By contrast, little is known about patient-specific risk factors. Older age was shown to increase the risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Several germline polymorphisms have also been associated with this risk, but none have been validated. As such, no predictive biomarkers exist for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms,” they wrote.

They performed a retrospective case-control study comparing patients treated for a primary cancer at their center from 1997 through 2015 who subsequently developed a myeloid neoplasm with controls treated during the same period. Controls were age-matched patients treated with combination chemotherapy for lymphoma who did not develop a therapy-related myeloid malignancy after at least 5 years of follow-up.

In addition, the investigators further explored the association between clonal hematopoiesis and therapy-related cancers in an external cohort of patients with lymphoma treated in a randomized trial at their center from 1999 through 2001. That trial compared the CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) with and without melatonin.

To detect clonal hematopoiesis in pre-treatment peripheral blood, the investigators used molecular barcode sequencing of 32 genes. They also used targeted gene sequencing on bone marrow samples from cases to investigate clonal evolution from clonal hematopoiesis to the development of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.

As noted before, 10 of 14 cases had evidence of pre-treatment clonal hematopoiesis, compared with 17 of 54 controls. For both cases and controls, the cumulative incidence of therapy-related myeloid cancers after 5 years was significantly higher among those with baseline clonal hematopoiesis, at 30% vs. 7% for patients without it (P = .016).

Five of 74 patients in the external cohort (7%) went on to develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, and of this group, four (80%) had clonal hematopoiesis at baseline. In contrast, of the 69 patients who did not develop therapy-related cancers, 11 (16%) had baseline clonal hematopoiesis.

In a multivariate model using data from the external cohort, clonal hematopoiesis was significantly associated with risk for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, with a hazard ratio of 13.7 (P = .013).

Elderly patient study

Dr. Gillis and her colleagues conducted a nested, case-control, proof-of-concept study to compare the prevalence of CHIP between patients with cancer who later developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (cases) and patients who did not (controls).

The cases were identified from an internal biobank of 123,357 patients, and included all patients who were diagnosed with a primary cancer, treated with chemotherapy, and subsequently developed a therapy-related myeloid neoplasm. The patients had to be 70 or older at the time of either primary or therapy-related cancer diagnosis with peripheral blood or mononuclear samples collected before the diagnosis of the second cancer.

Controls were patients diagnosed with a primary malignancy at age 70 or older who had chemotherapy but did not develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Every case was matched with at least four controls selected for sex, primary tumor type, age at diagnosis, smoking status, chemotherapy drug class, and duration of follow up.

They used sequential targeted and whole-exome sequencing to assess clonal evolution in cases for whom paired CHIP and therapy-related myeloid neoplasm samples were available.

They identified a total of 13 cases and 56 controls. Among all patients, CHIP was seen in 23 (33%). In contrast, previous studies have shown a prevalence of CHIP among older patients without cancer of about 10%, the authors note in their article.

The prevalence of CHIP was significantly higher among cases than among controls, occurring in 8 of 13 cases (62%) vs 15 of 56 controls (27%; P = .024). The odds ratio for therapy-related neoplasms with CHIP was 5.75 (P = .013).

The most commonly mutated genes were TET2 and TP53 among cases, and TET2 among controls.

“The distribution of CHIP-related gene mutations differs between individuals with therapy-related myeloid neoplasm and those without, suggesting that mutation-specific differences might exist in therapy-related myeloid neoplasm risk,” the investigators write.

Dr. Takahashi’s study was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, Red and Charline McCombs Institute for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cancer, The National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant, and the MD Anderson MDS & AML Moon Shots Program. Dr. Gillis’ study was internally funded. Dr. Takahasi and colleagues reported no competing financial interests. Two of Dr. Gillis’ colleagues reported grants or fees from several drug companies.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Pre-therapy clonal hematopoiesis is associated with increased risk for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.

Major finding: In two studies, the incidence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms was higher among patients with clonal hematopoiesis at baseline.

Data source: Retrospective case-control studies.

Disclosures: Dr. Takahashi’s study was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, Red and Charline McCombs Institute for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cancer, The National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant, and the MD Anderson MDS & AML Moon Shots Program. Dr. Gillis’ study was internally funded. Dr. Takahasi and colleagues reported no competing financial interests. Two of Dr. Gillis’ colleagues reported grants or fees from several drug companies.

Rituximab after ASCT boosted survival in mantle cell lymphoma

SAN DIEGO – Maintenance therapy every other month with rituximab significantly prolonged event-free and overall survival after autologous stem cell transplantation among younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, based on results from a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial.

After a median follow-up period of 50 months, 79% of the rituximab maintenance arm remained alive and free of progression, relapse, and severe infection, compared with 61% of the no-maintenance arm (P = .001), said Steven Le Gouill, MD, PhD, at the 2016 meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

This is the first study linking rituximab maintenance after ASCT to improved survival in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, said Dr. Le Gouill of Nantes University Hospital in Nantes, France.

The trial “demonstrates for the first time that rituximab maintenance after ASCT prolongs event-free survival, progression-free survival, and overall survival” in younger patients with treatment-naïve mantle cell lymphoma, Dr. Le Gouill said. The findings confirm rituximab maintenance as “a new standard of care” in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, he concluded.

Prior research http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1200920#t=abstract supports maintenance therapy with rituximab rather than interferon alfa for older patients whose mantle cell lymphoma responded to induction with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), noted Dr. Le Gouill. To examine outcomes in younger patients with treatment-naïve mantle cell lymphoma, he and his associates treated 299 individuals aged 65 years and younger (median age, 57 years) with standard induction consisting of 4 courses of rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and salt platinum (R-DHAP) every 21 days, followed by conditioning with rituximab plus BiCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (R-BEAM) and ASCT. Patients without at least a partial response to R-DHAP received 4 additional courses of R-CHOP-14 before ASCT. Patients then were randomized either to no maintenance or to infusions of 375 mg R per m2 every 2 months for 3 years.

A total of 53% of patients were mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index (MIPI) low risk, 27% were intermediate and 19% were high-risk. Rituximab maintenance was associated with a 60% lower risk of progression (HR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.68; P = .0007) and a 50% lower risk of death (HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.98; P = .04).

The French Innovative Leukemia Organisation sponsored the trial. Dr. Le Gouill disclosed ties to Roche, Janssen-Cilag, and Celgene.

SAN DIEGO – Maintenance therapy every other month with rituximab significantly prolonged event-free and overall survival after autologous stem cell transplantation among younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, based on results from a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial.

After a median follow-up period of 50 months, 79% of the rituximab maintenance arm remained alive and free of progression, relapse, and severe infection, compared with 61% of the no-maintenance arm (P = .001), said Steven Le Gouill, MD, PhD, at the 2016 meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

This is the first study linking rituximab maintenance after ASCT to improved survival in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, said Dr. Le Gouill of Nantes University Hospital in Nantes, France.

The trial “demonstrates for the first time that rituximab maintenance after ASCT prolongs event-free survival, progression-free survival, and overall survival” in younger patients with treatment-naïve mantle cell lymphoma, Dr. Le Gouill said. The findings confirm rituximab maintenance as “a new standard of care” in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, he concluded.

Prior research http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1200920#t=abstract supports maintenance therapy with rituximab rather than interferon alfa for older patients whose mantle cell lymphoma responded to induction with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), noted Dr. Le Gouill. To examine outcomes in younger patients with treatment-naïve mantle cell lymphoma, he and his associates treated 299 individuals aged 65 years and younger (median age, 57 years) with standard induction consisting of 4 courses of rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and salt platinum (R-DHAP) every 21 days, followed by conditioning with rituximab plus BiCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (R-BEAM) and ASCT. Patients without at least a partial response to R-DHAP received 4 additional courses of R-CHOP-14 before ASCT. Patients then were randomized either to no maintenance or to infusions of 375 mg R per m2 every 2 months for 3 years.

A total of 53% of patients were mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index (MIPI) low risk, 27% were intermediate and 19% were high-risk. Rituximab maintenance was associated with a 60% lower risk of progression (HR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.68; P = .0007) and a 50% lower risk of death (HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.98; P = .04).

The French Innovative Leukemia Organisation sponsored the trial. Dr. Le Gouill disclosed ties to Roche, Janssen-Cilag, and Celgene.

SAN DIEGO – Maintenance therapy every other month with rituximab significantly prolonged event-free and overall survival after autologous stem cell transplantation among younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, based on results from a multicenter, randomized, phase 3 trial.

After a median follow-up period of 50 months, 79% of the rituximab maintenance arm remained alive and free of progression, relapse, and severe infection, compared with 61% of the no-maintenance arm (P = .001), said Steven Le Gouill, MD, PhD, at the 2016 meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

This is the first study linking rituximab maintenance after ASCT to improved survival in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, said Dr. Le Gouill of Nantes University Hospital in Nantes, France.

The trial “demonstrates for the first time that rituximab maintenance after ASCT prolongs event-free survival, progression-free survival, and overall survival” in younger patients with treatment-naïve mantle cell lymphoma, Dr. Le Gouill said. The findings confirm rituximab maintenance as “a new standard of care” in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma, he concluded.

Prior research http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1200920#t=abstract supports maintenance therapy with rituximab rather than interferon alfa for older patients whose mantle cell lymphoma responded to induction with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), noted Dr. Le Gouill. To examine outcomes in younger patients with treatment-naïve mantle cell lymphoma, he and his associates treated 299 individuals aged 65 years and younger (median age, 57 years) with standard induction consisting of 4 courses of rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and salt platinum (R-DHAP) every 21 days, followed by conditioning with rituximab plus BiCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (R-BEAM) and ASCT. Patients without at least a partial response to R-DHAP received 4 additional courses of R-CHOP-14 before ASCT. Patients then were randomized either to no maintenance or to infusions of 375 mg R per m2 every 2 months for 3 years.

A total of 53% of patients were mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index (MIPI) low risk, 27% were intermediate and 19% were high-risk. Rituximab maintenance was associated with a 60% lower risk of progression (HR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.68; P = .0007) and a 50% lower risk of death (HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.98; P = .04).

The French Innovative Leukemia Organisation sponsored the trial. Dr. Le Gouill disclosed ties to Roche, Janssen-Cilag, and Celgene.

AT ASH 2016

Key clinical point: Maintenance therapy with rituximab after autologous stem cell transplantation was associated with significantly increased survival among younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma.

Major finding: After a median follow-up time of 50 months, 79% of patients who received rituximab maintenance remained alive and free of progression, relapse, and severe infection, compared with 61% of those who received no maintenance therapy (P = .001).

Data source: A multicenter randomized phase 3 trial of 299 adults up to 65 years old with mantle cell lymphoma.

Disclosures: The French Innovative Leukemia Organisation sponsored the trial. Dr. Le Gouill disclosed ties to Roche, Janssen-Cilag, and Celgene.

President Trump hits ground running on ACA repeal

WASHINGTON – President Trump wasted no time in getting the executive branch’s wheels in motion toward repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Within hours of being sworn in as the 45th president of the United States on Jan. 20, he signed an executive order that announced the incoming administration’s policy “to seek the prompt repeal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.”

The order opens the door for federal agencies to tackle ACA provisions such as the individual mandate and its tax penalties for not carrying insurance, as well as other financial aspects of the ACA that impact patients, providers, insurers, and manufacturers.

The order directs the secretaries of HHS, the Treasury department, and the Labor department to “exercise all authority and discretion available to them to provide greater flexibility to States and cooperate with them in implementing healthcare programs.”

With this order, President Trump also set the stage for creating a framework to sell insurance products across state lines by directing secretaries with oversight of insurance markets to “encourage the development of a free and open market in interstate commerce for the offering of healthcare services and health insurance, with the goal of achieving and preserving maximum options for patients and consumers.”

Little action is expected on the executive order until secretaries are approved for HHS, Treasury, and Labor. Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) is scheduled to appear before the Senate Finance Committee on Jan. 24.

WASHINGTON – President Trump wasted no time in getting the executive branch’s wheels in motion toward repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Within hours of being sworn in as the 45th president of the United States on Jan. 20, he signed an executive order that announced the incoming administration’s policy “to seek the prompt repeal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.”

The order opens the door for federal agencies to tackle ACA provisions such as the individual mandate and its tax penalties for not carrying insurance, as well as other financial aspects of the ACA that impact patients, providers, insurers, and manufacturers.

The order directs the secretaries of HHS, the Treasury department, and the Labor department to “exercise all authority and discretion available to them to provide greater flexibility to States and cooperate with them in implementing healthcare programs.”

With this order, President Trump also set the stage for creating a framework to sell insurance products across state lines by directing secretaries with oversight of insurance markets to “encourage the development of a free and open market in interstate commerce for the offering of healthcare services and health insurance, with the goal of achieving and preserving maximum options for patients and consumers.”

Little action is expected on the executive order until secretaries are approved for HHS, Treasury, and Labor. Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) is scheduled to appear before the Senate Finance Committee on Jan. 24.

WASHINGTON – President Trump wasted no time in getting the executive branch’s wheels in motion toward repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Within hours of being sworn in as the 45th president of the United States on Jan. 20, he signed an executive order that announced the incoming administration’s policy “to seek the prompt repeal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.”

The order opens the door for federal agencies to tackle ACA provisions such as the individual mandate and its tax penalties for not carrying insurance, as well as other financial aspects of the ACA that impact patients, providers, insurers, and manufacturers.

The order directs the secretaries of HHS, the Treasury department, and the Labor department to “exercise all authority and discretion available to them to provide greater flexibility to States and cooperate with them in implementing healthcare programs.”

With this order, President Trump also set the stage for creating a framework to sell insurance products across state lines by directing secretaries with oversight of insurance markets to “encourage the development of a free and open market in interstate commerce for the offering of healthcare services and health insurance, with the goal of achieving and preserving maximum options for patients and consumers.”

Little action is expected on the executive order until secretaries are approved for HHS, Treasury, and Labor. Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) is scheduled to appear before the Senate Finance Committee on Jan. 24.

Laser vaginal rejuvenation procedures

VIENNA – Vaginal rejuvenation is a major practice growth opportunity for dermatologists who have expertise with lasers, Peter Bjerring, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The rejuvenation procedures involve heating the connective tissue of the vaginal wall to 40-42 C in order to stimulate tissue remodeling with formation of new collagen and elastic fibers. The evidence base for vaginal rejuvenation using a variety of noninvasive energy-based devices developed for vaginal use isn’t nearly as extensive as it is for skin rejuvenation using lasers. Research is beginning to increase for this indication, but current results are primarily limited to small single-arm studies based on self-reported improvements. Further, studies don’t compare outcomes vs another treatment, such as estrogen cream.

Despite the minimal evidence base for laser procedures, “feminine rejuvenation is becoming very popular. These are (women) who might present to a dermatologist or to a gynecologist,” observed Dr. Bjerring, medical director and head of the Skin and Laser Center at Malholm (Denmark) Hospital.

Minimally ablative or nonablative fractional laser therapy for vaginal rejuvenation requires no anesthesia and no downtime. The lasers being used for this purpose are similar to those already used most often for skin resurfacing and rejuvenation of the face and neck: fractional CO2 lasers at the 10,600-nm wavelength, such as the MonaLisa Touch or FemTouch, and 2,940-nm nonablative erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) lasers such as the IntimaLase. A course of treatment with these devices typically consists of three, 15-minute sessions at 4- to 6-week intervals.

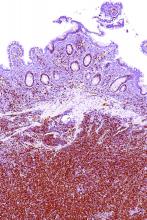

Dr. Bjerring noted that this mechanism of benefit has been demonstrated by Italian investigators who conducted a histologic study of the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser therapy on ex vivo specimens of atrophic vaginal tissue obtained from women with vulvovaginal atrophy who underwent major surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

The investigators treated one side of the atrophic vaginal wall specimen with the microablative fractional CO2 laser and left the contralateral area untreated as a control. They documented that laser therapy restored the vaginal squamous stratified epithelium, with enhanced storage of glycogen in the epithelial cells and shedding of glycogen-rich cells at the epithelial surface. In the connective tissue, activated fibroblasts synthesized new collagen-laden extracellular matrix. All this was accomplished without damage to adjacent untreated tissue (Menopause 2015 Aug;22(8):845-9).

In a single-arm study performed by many of the same Italian investigators, 77 postmenopausal women underwent a course of fractional microablative CO2 laser therapy because they experienced painful sexual intercourse due to vulvovaginal atrophy. At 12 weeks of followup, the group reported significant improvement in sexual function and satisfaction with their sexual life as measured by the Short Form-12 and the Female Sexual Function Index. Self-rated scores of vaginal burning, dryness, and itching improved significantly, as did complaints of pain during intercourse or urination. At baseline, 20 of the 77 women were not sexually active due to the severity of their vulvovaginal atrophy; at followup, 17 of the 20 had reestablished sexual activity (Climacteric. 2015 Apr;18(2):219-25).

Dr. Bjerring also highlighted an American study, again single-arm, in which 27 women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause were examined at baseline and again 3 months after their third and final treatment with a fractional CO2 laser. At follow up, 26 of the 27 pronounced themselves satisfied or extremely satisfied with the results, with significant improvement in the same outcome measures used in the Italian study. At follow up, 25 of the women had an increase in comfortable dilator size (Menopause 2016 Oct;23(10):1102-7).

Dr. Bjerring reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

VIENNA – Vaginal rejuvenation is a major practice growth opportunity for dermatologists who have expertise with lasers, Peter Bjerring, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The rejuvenation procedures involve heating the connective tissue of the vaginal wall to 40-42 C in order to stimulate tissue remodeling with formation of new collagen and elastic fibers. The evidence base for vaginal rejuvenation using a variety of noninvasive energy-based devices developed for vaginal use isn’t nearly as extensive as it is for skin rejuvenation using lasers. Research is beginning to increase for this indication, but current results are primarily limited to small single-arm studies based on self-reported improvements. Further, studies don’t compare outcomes vs another treatment, such as estrogen cream.

Despite the minimal evidence base for laser procedures, “feminine rejuvenation is becoming very popular. These are (women) who might present to a dermatologist or to a gynecologist,” observed Dr. Bjerring, medical director and head of the Skin and Laser Center at Malholm (Denmark) Hospital.

Minimally ablative or nonablative fractional laser therapy for vaginal rejuvenation requires no anesthesia and no downtime. The lasers being used for this purpose are similar to those already used most often for skin resurfacing and rejuvenation of the face and neck: fractional CO2 lasers at the 10,600-nm wavelength, such as the MonaLisa Touch or FemTouch, and 2,940-nm nonablative erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) lasers such as the IntimaLase. A course of treatment with these devices typically consists of three, 15-minute sessions at 4- to 6-week intervals.

Dr. Bjerring noted that this mechanism of benefit has been demonstrated by Italian investigators who conducted a histologic study of the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser therapy on ex vivo specimens of atrophic vaginal tissue obtained from women with vulvovaginal atrophy who underwent major surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

The investigators treated one side of the atrophic vaginal wall specimen with the microablative fractional CO2 laser and left the contralateral area untreated as a control. They documented that laser therapy restored the vaginal squamous stratified epithelium, with enhanced storage of glycogen in the epithelial cells and shedding of glycogen-rich cells at the epithelial surface. In the connective tissue, activated fibroblasts synthesized new collagen-laden extracellular matrix. All this was accomplished without damage to adjacent untreated tissue (Menopause 2015 Aug;22(8):845-9).

In a single-arm study performed by many of the same Italian investigators, 77 postmenopausal women underwent a course of fractional microablative CO2 laser therapy because they experienced painful sexual intercourse due to vulvovaginal atrophy. At 12 weeks of followup, the group reported significant improvement in sexual function and satisfaction with their sexual life as measured by the Short Form-12 and the Female Sexual Function Index. Self-rated scores of vaginal burning, dryness, and itching improved significantly, as did complaints of pain during intercourse or urination. At baseline, 20 of the 77 women were not sexually active due to the severity of their vulvovaginal atrophy; at followup, 17 of the 20 had reestablished sexual activity (Climacteric. 2015 Apr;18(2):219-25).

Dr. Bjerring also highlighted an American study, again single-arm, in which 27 women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause were examined at baseline and again 3 months after their third and final treatment with a fractional CO2 laser. At follow up, 26 of the 27 pronounced themselves satisfied or extremely satisfied with the results, with significant improvement in the same outcome measures used in the Italian study. At follow up, 25 of the women had an increase in comfortable dilator size (Menopause 2016 Oct;23(10):1102-7).

Dr. Bjerring reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

VIENNA – Vaginal rejuvenation is a major practice growth opportunity for dermatologists who have expertise with lasers, Peter Bjerring, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The rejuvenation procedures involve heating the connective tissue of the vaginal wall to 40-42 C in order to stimulate tissue remodeling with formation of new collagen and elastic fibers. The evidence base for vaginal rejuvenation using a variety of noninvasive energy-based devices developed for vaginal use isn’t nearly as extensive as it is for skin rejuvenation using lasers. Research is beginning to increase for this indication, but current results are primarily limited to small single-arm studies based on self-reported improvements. Further, studies don’t compare outcomes vs another treatment, such as estrogen cream.

Despite the minimal evidence base for laser procedures, “feminine rejuvenation is becoming very popular. These are (women) who might present to a dermatologist or to a gynecologist,” observed Dr. Bjerring, medical director and head of the Skin and Laser Center at Malholm (Denmark) Hospital.

Minimally ablative or nonablative fractional laser therapy for vaginal rejuvenation requires no anesthesia and no downtime. The lasers being used for this purpose are similar to those already used most often for skin resurfacing and rejuvenation of the face and neck: fractional CO2 lasers at the 10,600-nm wavelength, such as the MonaLisa Touch or FemTouch, and 2,940-nm nonablative erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) lasers such as the IntimaLase. A course of treatment with these devices typically consists of three, 15-minute sessions at 4- to 6-week intervals.

Dr. Bjerring noted that this mechanism of benefit has been demonstrated by Italian investigators who conducted a histologic study of the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser therapy on ex vivo specimens of atrophic vaginal tissue obtained from women with vulvovaginal atrophy who underwent major surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

The investigators treated one side of the atrophic vaginal wall specimen with the microablative fractional CO2 laser and left the contralateral area untreated as a control. They documented that laser therapy restored the vaginal squamous stratified epithelium, with enhanced storage of glycogen in the epithelial cells and shedding of glycogen-rich cells at the epithelial surface. In the connective tissue, activated fibroblasts synthesized new collagen-laden extracellular matrix. All this was accomplished without damage to adjacent untreated tissue (Menopause 2015 Aug;22(8):845-9).

In a single-arm study performed by many of the same Italian investigators, 77 postmenopausal women underwent a course of fractional microablative CO2 laser therapy because they experienced painful sexual intercourse due to vulvovaginal atrophy. At 12 weeks of followup, the group reported significant improvement in sexual function and satisfaction with their sexual life as measured by the Short Form-12 and the Female Sexual Function Index. Self-rated scores of vaginal burning, dryness, and itching improved significantly, as did complaints of pain during intercourse or urination. At baseline, 20 of the 77 women were not sexually active due to the severity of their vulvovaginal atrophy; at followup, 17 of the 20 had reestablished sexual activity (Climacteric. 2015 Apr;18(2):219-25).

Dr. Bjerring also highlighted an American study, again single-arm, in which 27 women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause were examined at baseline and again 3 months after their third and final treatment with a fractional CO2 laser. At follow up, 26 of the 27 pronounced themselves satisfied or extremely satisfied with the results, with significant improvement in the same outcome measures used in the Italian study. At follow up, 25 of the women had an increase in comfortable dilator size (Menopause 2016 Oct;23(10):1102-7).

Dr. Bjerring reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Curb AF recurrences through risk factor modification

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Overlooking the common modifiable risk factors in patients with atrial fibrillation is missing out on an excellent opportunity to help curb the growing global pandemic of the arrhythmia, Patrick T. O’Gara, MD, said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“My purpose here is a wake up call to improve screening for and treatment of modifiable risk factors in patients with atrial fibrillation,” declared Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Overweight/obesity: Investigators at the University of Adelaide (Australia) demonstrated in the LEGACY trial that patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more reduced their AF symptom burden in a dose-response fashion as they shed excess pounds as part of an intensive weight management program. Those who shed at least 10% of their baseline body weight had a 46% rate of 5-year freedom from AF without resort to rhythm control medications or ablation procedures of 46%. With 3%-9% weight loss, the rate was 22%. And with 3% weight loss, it was 13%.

The best results came from sustained linear weight loss. Weight fluctuations of greater than 5% – the classic yoyo dieting pattern – partially offset the overall benefit of weight loss with respect to recurrent AF (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 May 26;65(20):2159-69).

In a separate study, the same team of Australian investigators offered an opportunity to participate in a risk factor management program to patients with AF and a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more who were undergoing radiofrequency ablation for their arrhythmia. Participants had significantly fewer repeat ablation procedures during followup and were also less likely to be on antiarrhythmic drugs than the patients who opted for usual care (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Dec 2;64(21):2222-31).

Alcohol: The ‘holiday heart’ syndrome is well known, but alcohol consumption beyond binging can increase risk for AF. Dr. O’Gara noted that in a recent review article entitled “Alcohol and Atrial Fibrillation: A Sobering Review,” investigators at the University of Melbourne showed that while the relationship between the number of standard drinks per week and risk of cardiovascular mortality is J-shaped, with a nadir at 14-21 drinks per week in men and fewer in women, the risk of developing AF is linear over time and appears to increase incrementally with every additional drink per week (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Dec 13;68(23):2567-76).

Also, a prospective study of nearly 80,000 Swedes free from AF at baseline, coupled with a meta-analysis of seven prospective studies found that for each additional drink per day consumed the risk of developing AF rose over time by roughly a further 10% compared to that of teetotalers (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; Jul 22;64(3):281-9).

Physical inactivity: In the prospective Tromso Study, in which more than 20,000 Norwegian adults were followed for 20 years, leisure time physical activity displayed a J-shaped relationship with the risk of developing AF. Moderately active subjects were an adjusted 19% less likely to develop AF than those with low physical activity, while the risk in subjects who regularly engaged in vigorous physical activity was 37% higher than in the low-activity group (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 1;37(29):2307-13).

“This effect of moderate exercise might be due to the associated weight loss, improved endothelial function, better sleep, perhaps a better balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems,” Dr. O’Gara observed.