User login

Annual AGA Tech Summit returns to Boston in 2017

AGA is excited to return to Boston for its eighth annual Tech Summit on April 12-14, 2017, at the InterContinental Hotel. We’ve assembled prominent individuals in the physician, medtech, and regulatory communities to lead attendees through a program that’s both informative and inspirational.

This is an ideal opportunity to explore critical elements impacting how GI technology evolves from concept to reality, including what it takes to obtain adoption, coverage, and reimbursement in a continually evolving health care environment.

We hope to see you this spring in Boston for a truly unique experience. Learn more and register at http://techsummit.gastro.org.

Have a novel idea or innovation? Apply for the AGA “Shark Tank”Calling all companies and entrepreneurs with an innovative technology or FDA-regulated product. If you are looking to get it financed, licensed, or distributed, you are encouraged to submit an application for an opportunity to present during the “Shark Tank” session at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit. A panel of business development leaders, investors, entrepreneurs, and other strategic partners will provide valuable feedback.

AGA is excited to return to Boston for its eighth annual Tech Summit on April 12-14, 2017, at the InterContinental Hotel. We’ve assembled prominent individuals in the physician, medtech, and regulatory communities to lead attendees through a program that’s both informative and inspirational.

This is an ideal opportunity to explore critical elements impacting how GI technology evolves from concept to reality, including what it takes to obtain adoption, coverage, and reimbursement in a continually evolving health care environment.

We hope to see you this spring in Boston for a truly unique experience. Learn more and register at http://techsummit.gastro.org.

Have a novel idea or innovation? Apply for the AGA “Shark Tank”Calling all companies and entrepreneurs with an innovative technology or FDA-regulated product. If you are looking to get it financed, licensed, or distributed, you are encouraged to submit an application for an opportunity to present during the “Shark Tank” session at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit. A panel of business development leaders, investors, entrepreneurs, and other strategic partners will provide valuable feedback.

AGA is excited to return to Boston for its eighth annual Tech Summit on April 12-14, 2017, at the InterContinental Hotel. We’ve assembled prominent individuals in the physician, medtech, and regulatory communities to lead attendees through a program that’s both informative and inspirational.

This is an ideal opportunity to explore critical elements impacting how GI technology evolves from concept to reality, including what it takes to obtain adoption, coverage, and reimbursement in a continually evolving health care environment.

We hope to see you this spring in Boston for a truly unique experience. Learn more and register at http://techsummit.gastro.org.

Have a novel idea or innovation? Apply for the AGA “Shark Tank”Calling all companies and entrepreneurs with an innovative technology or FDA-regulated product. If you are looking to get it financed, licensed, or distributed, you are encouraged to submit an application for an opportunity to present during the “Shark Tank” session at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit. A panel of business development leaders, investors, entrepreneurs, and other strategic partners will provide valuable feedback.

New histopathologic marker may aid dermatomyositis diagnosis

The detection of sarcoplasmic myxovirus resistance A expression in immunohistochemical analysis of muscle biopsy in patients suspected of having dermatomyositis may add greater sensitivity for the diagnosis when compared with conventional pathologic hallmarks of the disease, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Myxovirus resistance A (MxA) is one of the type 1 interferon–inducible proteins whose overexpression is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis, and MxA expression has rarely been observed in other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, said first author Akinori Uruha, MD, PhD, of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, and his colleagues. They compared MxA expression in muscle biopsy samples from definite, probable, and possible dermatomyositis cases as well as other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and other control conditions to assess its value against other muscle pathologic markers of dermatomyositis, such as the presence of perifascicular atrophy (PFA) and capillary membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition (Neurology. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003568).

The investigators studied muscle biopsy samples collected from 154 consecutive patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies seen from all over Japan, including 34 with dermatomyositis (10 juvenile cases), 8 with polymyositis (1 juvenile), 16 with anti–tRNA-synthetase antibody–associated myopathy (ASM); 46 with immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), and 50 with inclusion body myositis. The IMNM cases involved included 24 with anti–signal recognition particle (SRP) antibodies, 6 with anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) antibodies, and 16 without anti-SRP, anti-HMGCR, or anti–tRNA-synthetase antibodies (3 juvenile patients). They used 51 patients with muscular dystrophy and 26 with neuropathies as controls.

Sarcoplasmic MxA expression proved to be more sensitive for a diagnosis of dermatomyositis than PFA and capillary MAC deposition (71% vs. 47% and 35%, respectively) but still had comparable specificity to those two markers (98% vs. 98% and 93%, respectively).

Of 18 cases with probable dermatomyositis, defined as typical skin rash but a lack of PFA, 8 (44%) showed sarcoplasmic MxA expression, and its sensitivity was 90% in juvenile cases overall and 63% in adult patients. Only 3 (17%) of the 18 showed capillary MAC deposition. Sarcoplasmic MxA expression occurred in all 12 patients with definite dermatomyositis, defined by the typical skin rash plus presence of PFA, whereas only 7 (58%) showed capillary MAC deposition. Among the four patients with possible dermatomyositis (PFA present but lacking typical skin rash), all showed sarcoplasmic MxA expression, compared with just two showing capillary MAC deposition.

In all other patients without definite, probable, or possible dermatomyositis, only two were positive for sarcoplasmic MxA expression (one with ASM and one with IMNM).

Dr. Uruha and his associates said that the results are “clearly demonstrating that sarcoplasmic MxA expression should be an excellent diagnostic marker of [dermatomyositis].”

The authors noted that the study was limited by the fact that they could not obtain full information about dermatomyositis-associated antibodies, and because other proteins of type 1 interferon signature are known to be upregulated in dermatomyositis, additional studies will need to determine which of the proteins is a better diagnostic marker.

The study was supported partly by an Intramural Research Grant of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

The detection of sarcoplasmic myxovirus resistance A expression in immunohistochemical analysis of muscle biopsy in patients suspected of having dermatomyositis may add greater sensitivity for the diagnosis when compared with conventional pathologic hallmarks of the disease, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Myxovirus resistance A (MxA) is one of the type 1 interferon–inducible proteins whose overexpression is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis, and MxA expression has rarely been observed in other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, said first author Akinori Uruha, MD, PhD, of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, and his colleagues. They compared MxA expression in muscle biopsy samples from definite, probable, and possible dermatomyositis cases as well as other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and other control conditions to assess its value against other muscle pathologic markers of dermatomyositis, such as the presence of perifascicular atrophy (PFA) and capillary membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition (Neurology. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003568).

The investigators studied muscle biopsy samples collected from 154 consecutive patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies seen from all over Japan, including 34 with dermatomyositis (10 juvenile cases), 8 with polymyositis (1 juvenile), 16 with anti–tRNA-synthetase antibody–associated myopathy (ASM); 46 with immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), and 50 with inclusion body myositis. The IMNM cases involved included 24 with anti–signal recognition particle (SRP) antibodies, 6 with anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) antibodies, and 16 without anti-SRP, anti-HMGCR, or anti–tRNA-synthetase antibodies (3 juvenile patients). They used 51 patients with muscular dystrophy and 26 with neuropathies as controls.

Sarcoplasmic MxA expression proved to be more sensitive for a diagnosis of dermatomyositis than PFA and capillary MAC deposition (71% vs. 47% and 35%, respectively) but still had comparable specificity to those two markers (98% vs. 98% and 93%, respectively).

Of 18 cases with probable dermatomyositis, defined as typical skin rash but a lack of PFA, 8 (44%) showed sarcoplasmic MxA expression, and its sensitivity was 90% in juvenile cases overall and 63% in adult patients. Only 3 (17%) of the 18 showed capillary MAC deposition. Sarcoplasmic MxA expression occurred in all 12 patients with definite dermatomyositis, defined by the typical skin rash plus presence of PFA, whereas only 7 (58%) showed capillary MAC deposition. Among the four patients with possible dermatomyositis (PFA present but lacking typical skin rash), all showed sarcoplasmic MxA expression, compared with just two showing capillary MAC deposition.

In all other patients without definite, probable, or possible dermatomyositis, only two were positive for sarcoplasmic MxA expression (one with ASM and one with IMNM).

Dr. Uruha and his associates said that the results are “clearly demonstrating that sarcoplasmic MxA expression should be an excellent diagnostic marker of [dermatomyositis].”

The authors noted that the study was limited by the fact that they could not obtain full information about dermatomyositis-associated antibodies, and because other proteins of type 1 interferon signature are known to be upregulated in dermatomyositis, additional studies will need to determine which of the proteins is a better diagnostic marker.

The study was supported partly by an Intramural Research Grant of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

The detection of sarcoplasmic myxovirus resistance A expression in immunohistochemical analysis of muscle biopsy in patients suspected of having dermatomyositis may add greater sensitivity for the diagnosis when compared with conventional pathologic hallmarks of the disease, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Myxovirus resistance A (MxA) is one of the type 1 interferon–inducible proteins whose overexpression is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis, and MxA expression has rarely been observed in other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, said first author Akinori Uruha, MD, PhD, of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, and his colleagues. They compared MxA expression in muscle biopsy samples from definite, probable, and possible dermatomyositis cases as well as other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and other control conditions to assess its value against other muscle pathologic markers of dermatomyositis, such as the presence of perifascicular atrophy (PFA) and capillary membrane attack complex (MAC) deposition (Neurology. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003568).

The investigators studied muscle biopsy samples collected from 154 consecutive patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies seen from all over Japan, including 34 with dermatomyositis (10 juvenile cases), 8 with polymyositis (1 juvenile), 16 with anti–tRNA-synthetase antibody–associated myopathy (ASM); 46 with immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), and 50 with inclusion body myositis. The IMNM cases involved included 24 with anti–signal recognition particle (SRP) antibodies, 6 with anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR) antibodies, and 16 without anti-SRP, anti-HMGCR, or anti–tRNA-synthetase antibodies (3 juvenile patients). They used 51 patients with muscular dystrophy and 26 with neuropathies as controls.

Sarcoplasmic MxA expression proved to be more sensitive for a diagnosis of dermatomyositis than PFA and capillary MAC deposition (71% vs. 47% and 35%, respectively) but still had comparable specificity to those two markers (98% vs. 98% and 93%, respectively).

Of 18 cases with probable dermatomyositis, defined as typical skin rash but a lack of PFA, 8 (44%) showed sarcoplasmic MxA expression, and its sensitivity was 90% in juvenile cases overall and 63% in adult patients. Only 3 (17%) of the 18 showed capillary MAC deposition. Sarcoplasmic MxA expression occurred in all 12 patients with definite dermatomyositis, defined by the typical skin rash plus presence of PFA, whereas only 7 (58%) showed capillary MAC deposition. Among the four patients with possible dermatomyositis (PFA present but lacking typical skin rash), all showed sarcoplasmic MxA expression, compared with just two showing capillary MAC deposition.

In all other patients without definite, probable, or possible dermatomyositis, only two were positive for sarcoplasmic MxA expression (one with ASM and one with IMNM).

Dr. Uruha and his associates said that the results are “clearly demonstrating that sarcoplasmic MxA expression should be an excellent diagnostic marker of [dermatomyositis].”

The authors noted that the study was limited by the fact that they could not obtain full information about dermatomyositis-associated antibodies, and because other proteins of type 1 interferon signature are known to be upregulated in dermatomyositis, additional studies will need to determine which of the proteins is a better diagnostic marker.

The study was supported partly by an Intramural Research Grant of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Sarcoplasmic MxA expression proved to be more sensitive for a diagnosis of dermatomyositis than PFA and capillary MAC deposition (71% vs. 47% and 35%, respectively) but still had comparable specificity to those two markers (98% vs. 98% and 93%, respectively).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 154 patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, 51 with muscular dystrophy, and 26 with neuropathies.

Disclosures: The study was supported partly by an Intramural Research Grant of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Skin-Lightening Agents

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on skin-lightening agents. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better Clinical Dark Spot Corrector

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica, an Allergan compan

“It contains vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, and licorice root extract to help lighten the skin and improve texture without hydroquinone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Meladerm

Civant Skin Care

“This is an excellent hydroquinone-free cream for treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma. It contains a combination of ingredients known to inhibit various steps along the melanogenesis pathway, such as retinyl palmitate, licorice extract, and arbutin, as well as lactic, kojic, and ascorbic acids.”—Cherise M. Levi, DO, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, dry shampoos, athlete’s foot treatments, and face scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on skin-lightening agents. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better Clinical Dark Spot Corrector

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica, an Allergan compan

“It contains vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, and licorice root extract to help lighten the skin and improve texture without hydroquinone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Meladerm

Civant Skin Care

“This is an excellent hydroquinone-free cream for treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma. It contains a combination of ingredients known to inhibit various steps along the melanogenesis pathway, such as retinyl palmitate, licorice extract, and arbutin, as well as lactic, kojic, and ascorbic acids.”—Cherise M. Levi, DO, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, dry shampoos, athlete’s foot treatments, and face scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on skin-lightening agents. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better Clinical Dark Spot Corrector

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica, an Allergan compan

“It contains vitamin C, niacinamide, retinol, and licorice root extract to help lighten the skin and improve texture without hydroquinone.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Meladerm

Civant Skin Care

“This is an excellent hydroquinone-free cream for treating postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and melasma. It contains a combination of ingredients known to inhibit various steps along the melanogenesis pathway, such as retinyl palmitate, licorice extract, and arbutin, as well as lactic, kojic, and ascorbic acids.”—Cherise M. Levi, DO, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, dry shampoos, athlete’s foot treatments, and face scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

Hybrid procedures may be better option for LVOTO in lower-weight neonates

Little outcomes data have been published comparing hybrid and Norwood stage 1 procedures for newborns with critical left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), but a prospective analysis of more than 500 operations over 9 years reported that while the Norwood has better survival rates overall, hybrid procedures may improve survival in low-birth-weight newborns.

“Although lower birth weight was identified as an important risk factor for death for the entire cohort, the detrimental impact of low birth weight was mitigated, to some degree, for patients who underwent a hybrid procedure,” said Travis Wilder, MD, of the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society (CHSS) Data Center, and his coauthors. They reported their findings in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (153:163-72).

Norwood operations involve major surgical reconstruction along with exposure to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), with either deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) or regional cerebral perfusion, during aortic arch reconstruction. Previous reports have linked CPB to postoperative hemodynamic instability, complications, and death (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 Jun;87:1885-92). “In addition, the early physiological stress imposed on neonates after Norwood operations raises concerns regarding adverse neurodevelopment,” Dr. Wilder and his coauthors wrote.

Dr. Wilder and his coauthors pointed out that the hybrid procedure has emerged to avoid CPB and DHCA or regional cerebral perfusion and the potential resulting physiologic instability. “In this light, hybrid palliation may be perceived as a lower-risk alternative to Norwood operations, especially for patients considered at high risk for mortality,” the researchers said. Despite that perception, the actual survival “remains incompletely defined,” they said.

The overall average 4-year unadjusted survival for the entire study population was 65%, but those who had the NW-RVPA procedure had significantly improved survival (73%) vs. both the NW-BT (61%) and the hybrid groups (60%).

Those who had the hybrid procedure were older at stage 1 (12 days vs. 8 and 6 days, respectively for NW-BT and NW-RVPA) and had lower birth weight (2.9 kg vs. 3.2 kg and 3.15 kg, respectively). Hybrid patients also had a higher prevalence of baseline right ventricle dysfunction, were more likely to have baseline tricuspid valve regurgitation, and had a lower prevalence of aortic and mitral valve atresia.

For all patients, birth weight of 2.0-2.5 kg had a strong association with poor survival, Dr. Wilder and his coauthors reported, but the drop-off in survival for low-birth-weight neonates was greater in the Norwood group than in the hybrid group. “This finding suggests that hybrid procedures may offer a modest survival advantage over NW-RVPA at birth weight less than or equal to 2.0 kg and over NW-BT at birth weight less than or equal to 3.0 kg,” the researchers said.

Dr. Wilder and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

While the study by Dr. Wilder and his coauthors may have drawn an accurate conclusion about low-birth-weight newborns possibly benefiting from a hybrid procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the number of patients in each strategy was small, Carlos M. Mery, MD, MPH, of Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Jan;153:173-4).

Dr. Mery noted other limitations of the study, namely the heterogeneity of procedures by participating center. “Of the 20 centers, only 11 performed any hybrid procedures, and 1 center accounted for 42% of all hybrid procedures performed,” he said. “Because centers may be associated with possibly unaccounted risk factors and different learning curves, the conclusions may not be easily generalizable.”

The conclusion that newborns of lower birth weight may benefit from the hybrid procedure helps to bring clarity for which patients may benefit from a specific procedure, Dr. Mery said. “We seem to be getting closer to the ultimate goal of being able to offer each individual patient the management strategy that will lead to the best possible outcome, not only for quantity but also for quality of life,” Dr. Mery said.

Dr. Mery had no financial relationships to disclose.

While the study by Dr. Wilder and his coauthors may have drawn an accurate conclusion about low-birth-weight newborns possibly benefiting from a hybrid procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the number of patients in each strategy was small, Carlos M. Mery, MD, MPH, of Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Jan;153:173-4).

Dr. Mery noted other limitations of the study, namely the heterogeneity of procedures by participating center. “Of the 20 centers, only 11 performed any hybrid procedures, and 1 center accounted for 42% of all hybrid procedures performed,” he said. “Because centers may be associated with possibly unaccounted risk factors and different learning curves, the conclusions may not be easily generalizable.”

The conclusion that newborns of lower birth weight may benefit from the hybrid procedure helps to bring clarity for which patients may benefit from a specific procedure, Dr. Mery said. “We seem to be getting closer to the ultimate goal of being able to offer each individual patient the management strategy that will lead to the best possible outcome, not only for quantity but also for quality of life,” Dr. Mery said.

Dr. Mery had no financial relationships to disclose.

While the study by Dr. Wilder and his coauthors may have drawn an accurate conclusion about low-birth-weight newborns possibly benefiting from a hybrid procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the number of patients in each strategy was small, Carlos M. Mery, MD, MPH, of Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Jan;153:173-4).

Dr. Mery noted other limitations of the study, namely the heterogeneity of procedures by participating center. “Of the 20 centers, only 11 performed any hybrid procedures, and 1 center accounted for 42% of all hybrid procedures performed,” he said. “Because centers may be associated with possibly unaccounted risk factors and different learning curves, the conclusions may not be easily generalizable.”

The conclusion that newborns of lower birth weight may benefit from the hybrid procedure helps to bring clarity for which patients may benefit from a specific procedure, Dr. Mery said. “We seem to be getting closer to the ultimate goal of being able to offer each individual patient the management strategy that will lead to the best possible outcome, not only for quantity but also for quality of life,” Dr. Mery said.

Dr. Mery had no financial relationships to disclose.

Little outcomes data have been published comparing hybrid and Norwood stage 1 procedures for newborns with critical left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), but a prospective analysis of more than 500 operations over 9 years reported that while the Norwood has better survival rates overall, hybrid procedures may improve survival in low-birth-weight newborns.

“Although lower birth weight was identified as an important risk factor for death for the entire cohort, the detrimental impact of low birth weight was mitigated, to some degree, for patients who underwent a hybrid procedure,” said Travis Wilder, MD, of the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society (CHSS) Data Center, and his coauthors. They reported their findings in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (153:163-72).

Norwood operations involve major surgical reconstruction along with exposure to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), with either deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) or regional cerebral perfusion, during aortic arch reconstruction. Previous reports have linked CPB to postoperative hemodynamic instability, complications, and death (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 Jun;87:1885-92). “In addition, the early physiological stress imposed on neonates after Norwood operations raises concerns regarding adverse neurodevelopment,” Dr. Wilder and his coauthors wrote.

Dr. Wilder and his coauthors pointed out that the hybrid procedure has emerged to avoid CPB and DHCA or regional cerebral perfusion and the potential resulting physiologic instability. “In this light, hybrid palliation may be perceived as a lower-risk alternative to Norwood operations, especially for patients considered at high risk for mortality,” the researchers said. Despite that perception, the actual survival “remains incompletely defined,” they said.

The overall average 4-year unadjusted survival for the entire study population was 65%, but those who had the NW-RVPA procedure had significantly improved survival (73%) vs. both the NW-BT (61%) and the hybrid groups (60%).

Those who had the hybrid procedure were older at stage 1 (12 days vs. 8 and 6 days, respectively for NW-BT and NW-RVPA) and had lower birth weight (2.9 kg vs. 3.2 kg and 3.15 kg, respectively). Hybrid patients also had a higher prevalence of baseline right ventricle dysfunction, were more likely to have baseline tricuspid valve regurgitation, and had a lower prevalence of aortic and mitral valve atresia.

For all patients, birth weight of 2.0-2.5 kg had a strong association with poor survival, Dr. Wilder and his coauthors reported, but the drop-off in survival for low-birth-weight neonates was greater in the Norwood group than in the hybrid group. “This finding suggests that hybrid procedures may offer a modest survival advantage over NW-RVPA at birth weight less than or equal to 2.0 kg and over NW-BT at birth weight less than or equal to 3.0 kg,” the researchers said.

Dr. Wilder and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Little outcomes data have been published comparing hybrid and Norwood stage 1 procedures for newborns with critical left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), but a prospective analysis of more than 500 operations over 9 years reported that while the Norwood has better survival rates overall, hybrid procedures may improve survival in low-birth-weight newborns.

“Although lower birth weight was identified as an important risk factor for death for the entire cohort, the detrimental impact of low birth weight was mitigated, to some degree, for patients who underwent a hybrid procedure,” said Travis Wilder, MD, of the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society (CHSS) Data Center, and his coauthors. They reported their findings in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (153:163-72).

Norwood operations involve major surgical reconstruction along with exposure to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), with either deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) or regional cerebral perfusion, during aortic arch reconstruction. Previous reports have linked CPB to postoperative hemodynamic instability, complications, and death (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 Jun;87:1885-92). “In addition, the early physiological stress imposed on neonates after Norwood operations raises concerns regarding adverse neurodevelopment,” Dr. Wilder and his coauthors wrote.

Dr. Wilder and his coauthors pointed out that the hybrid procedure has emerged to avoid CPB and DHCA or regional cerebral perfusion and the potential resulting physiologic instability. “In this light, hybrid palliation may be perceived as a lower-risk alternative to Norwood operations, especially for patients considered at high risk for mortality,” the researchers said. Despite that perception, the actual survival “remains incompletely defined,” they said.

The overall average 4-year unadjusted survival for the entire study population was 65%, but those who had the NW-RVPA procedure had significantly improved survival (73%) vs. both the NW-BT (61%) and the hybrid groups (60%).

Those who had the hybrid procedure were older at stage 1 (12 days vs. 8 and 6 days, respectively for NW-BT and NW-RVPA) and had lower birth weight (2.9 kg vs. 3.2 kg and 3.15 kg, respectively). Hybrid patients also had a higher prevalence of baseline right ventricle dysfunction, were more likely to have baseline tricuspid valve regurgitation, and had a lower prevalence of aortic and mitral valve atresia.

For all patients, birth weight of 2.0-2.5 kg had a strong association with poor survival, Dr. Wilder and his coauthors reported, but the drop-off in survival for low-birth-weight neonates was greater in the Norwood group than in the hybrid group. “This finding suggests that hybrid procedures may offer a modest survival advantage over NW-RVPA at birth weight less than or equal to 2.0 kg and over NW-BT at birth weight less than or equal to 3.0 kg,” the researchers said.

Dr. Wilder and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Norwood procedures have the best survival rates for neonates with critical left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, but hybrid procedures may improve survival for those with lower birth weight.

Major finding: Risk-adjusted 4-year survival was 76% for the Norwood operation with a right ventricle–to-pulmonary artery conduit, 61% for Norwood with a modified Blalock-Taussig shunt and 60% for the hybrid procedure.

Data source: Prospective observational cohort study of 564 neonates admitted to 21 Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society institutions from 2005 to 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Wilder and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

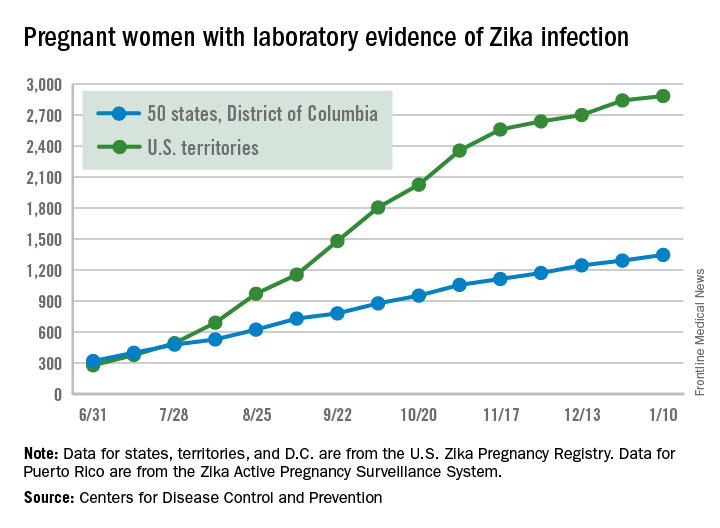

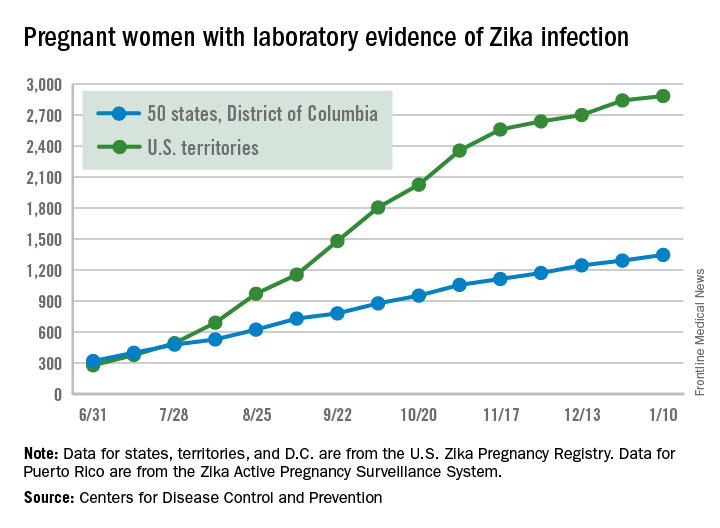

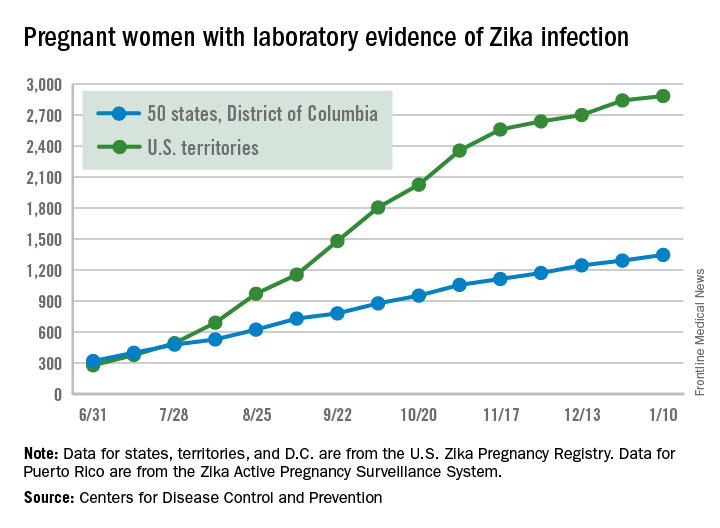

Zika virus slowdown continues

Zika activity is slowing as winter progresses, with less than a hundred new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of infection reported over the 2 weeks ending Jan. 10, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent CDC data show that, for the first time since early August, the majority of new cases of Zika infection among pregnant women were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with the U.S. territories. There were a total of 98 new cases, with 55 reported in the states and 43 in the U.S. territories.

The total number of Zika-infected pregnant women in the United States is now 4,232 for 2016-2017. There have been 2,885 cases in the territories and 1,347 cases reported in the states/D.C. Among the cases in the states/D.C., 940 pregnancies have been completed, with Zika-related birth defects seen in 37 live-born infants and five pregnancy losses, the CDC said. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria.

Zika cases among all Americans are still being reported weekly by the CDC, and the increase there has slowed as well: Total cases were up by 146 for the week ending Jan. 18, compared with 294 and 205 for each of the previous 2 weeks, according to CDC reports.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika activity is slowing as winter progresses, with less than a hundred new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of infection reported over the 2 weeks ending Jan. 10, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent CDC data show that, for the first time since early August, the majority of new cases of Zika infection among pregnant women were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with the U.S. territories. There were a total of 98 new cases, with 55 reported in the states and 43 in the U.S. territories.

The total number of Zika-infected pregnant women in the United States is now 4,232 for 2016-2017. There have been 2,885 cases in the territories and 1,347 cases reported in the states/D.C. Among the cases in the states/D.C., 940 pregnancies have been completed, with Zika-related birth defects seen in 37 live-born infants and five pregnancy losses, the CDC said. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria.

Zika cases among all Americans are still being reported weekly by the CDC, and the increase there has slowed as well: Total cases were up by 146 for the week ending Jan. 18, compared with 294 and 205 for each of the previous 2 weeks, according to CDC reports.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Zika activity is slowing as winter progresses, with less than a hundred new cases of pregnant women with laboratory evidence of infection reported over the 2 weeks ending Jan. 10, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent CDC data show that, for the first time since early August, the majority of new cases of Zika infection among pregnant women were reported in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with the U.S. territories. There were a total of 98 new cases, with 55 reported in the states and 43 in the U.S. territories.

The total number of Zika-infected pregnant women in the United States is now 4,232 for 2016-2017. There have been 2,885 cases in the territories and 1,347 cases reported in the states/D.C. Among the cases in the states/D.C., 940 pregnancies have been completed, with Zika-related birth defects seen in 37 live-born infants and five pregnancy losses, the CDC said. The CDC is no longer reporting adverse pregnancy outcomes for the territories because Puerto Rico is not using the same inclusion criteria.

Zika cases among all Americans are still being reported weekly by the CDC, and the increase there has slowed as well: Total cases were up by 146 for the week ending Jan. 18, compared with 294 and 205 for each of the previous 2 weeks, according to CDC reports.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Sleeve lobectomy appears better than pneumonectomy for NSCLC

Guidelines that recommend sleeve lobectomy as a means of avoiding pneumonectomy for lung cancer have been based on a limited retrospective series, but a large series drawn from a nationwide database in France has confirmed the preference for sleeve lobectomy because it leads to higher rates of survival, despite an increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications.

“Whenever it is technically possible, surgeons must perform sleeve lobectomy to provide more long-term survival benefits to patients, even with the risk of more postoperative pulmonary complications,” said Pierre-Benoit Pagès, MD, PhD, and his coauthors in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:184-95). Dr. Pagès is with the department of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University Hospital Center Dijon (France) and Bocage Hospital.

Three-year overall survival was 71.9% for the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 60.8% for the pneumonectomy group. Three-year disease-free survival was 46.4% for the sleeve lobectomy group and 31.6% for the pneumonectomy group. In addition, compared with the sleeve lobectomy group, the pneumonectomy group had an increased risk of recurrence by matching (hazard ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.1-2).

The researchers performed a propensity-matched analysis that favored sleeve lobectomy for early overall and disease-free survival, but the weighted analysis did not. Patients in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. the pneumonectomy group were younger (60.9 years vs. 61.9), had higher body mass index (25.6 vs. 25.1), had higher average forced expiratory volume (74.1% vs. 62.9%), and had lower American Society of Anesthesiologists scores (73.7% with scores of 1 and 2 vs. 70.8%). Sleeve lobectomy patients also were more likely to have right-sided surgery (69.6% vs. 41%) and squamous cell carcinoma (54.6% vs. 48.3%), and lower T and N stages (T1 and T2, 60.5% vs. 40.6%; N0, 40.9% vs. 26.2%).

Overall mortality after surgery was 5% in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 5.9% in the pneumonectomy group, but propensity scoring showed far fewer postoperative pulmonary complications in the pneumonectomy group, with an odds ratio of 0.4, Dr. Pagès and his coauthors said. However, with other significant complications – arrhythmia, bronchopleural fistula, empyema, and hemorrhage – pneumonectomy had a propensity-matched odds ratio ranging from 1.6 to 7. “We found no significant difference regarding postoperative mortality in the sleeve lobectomy and pneumonectomy groups, whatever the statistical method used,” Dr. Pagès and his coauthors wrote.

The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study by Dr. Pagès and his colleagues is unique in the field of surgery for non–small cell lung cancer in that it drew on a nationwide database using data from 103 centers, Betty C. Tong, MD, MHS, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:196). “These results are likely as close to real life as possible,” she said.

She acknowledged that no prospective, randomized controlled trials have compared sleeve lobectomy to pneumonectomy, but she added, “it is unlikely that such a trial could be successfully executed.” The 5:1 ratio of patients having pneumonectomy vs. sleeve lobectomy in this study is similar to findings from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery database (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;132:247-54), Dr. Tong pointed out, “and likely reflects the fact that sleeve lobectomy can be technically more difficult to perform.”

The findings of the French Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery group “should strongly encourage thoracic surgeons to perform pneumonectomy as sparingly as possible,” and consider sleeve lobectomy the standard for patients with central tumors, Dr. Tong said.

She had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study by Dr. Pagès and his colleagues is unique in the field of surgery for non–small cell lung cancer in that it drew on a nationwide database using data from 103 centers, Betty C. Tong, MD, MHS, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:196). “These results are likely as close to real life as possible,” she said.

She acknowledged that no prospective, randomized controlled trials have compared sleeve lobectomy to pneumonectomy, but she added, “it is unlikely that such a trial could be successfully executed.” The 5:1 ratio of patients having pneumonectomy vs. sleeve lobectomy in this study is similar to findings from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery database (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;132:247-54), Dr. Tong pointed out, “and likely reflects the fact that sleeve lobectomy can be technically more difficult to perform.”

The findings of the French Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery group “should strongly encourage thoracic surgeons to perform pneumonectomy as sparingly as possible,” and consider sleeve lobectomy the standard for patients with central tumors, Dr. Tong said.

She had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study by Dr. Pagès and his colleagues is unique in the field of surgery for non–small cell lung cancer in that it drew on a nationwide database using data from 103 centers, Betty C. Tong, MD, MHS, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:196). “These results are likely as close to real life as possible,” she said.

She acknowledged that no prospective, randomized controlled trials have compared sleeve lobectomy to pneumonectomy, but she added, “it is unlikely that such a trial could be successfully executed.” The 5:1 ratio of patients having pneumonectomy vs. sleeve lobectomy in this study is similar to findings from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery database (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;132:247-54), Dr. Tong pointed out, “and likely reflects the fact that sleeve lobectomy can be technically more difficult to perform.”

The findings of the French Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery group “should strongly encourage thoracic surgeons to perform pneumonectomy as sparingly as possible,” and consider sleeve lobectomy the standard for patients with central tumors, Dr. Tong said.

She had no financial relationships to disclose.

Guidelines that recommend sleeve lobectomy as a means of avoiding pneumonectomy for lung cancer have been based on a limited retrospective series, but a large series drawn from a nationwide database in France has confirmed the preference for sleeve lobectomy because it leads to higher rates of survival, despite an increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications.

“Whenever it is technically possible, surgeons must perform sleeve lobectomy to provide more long-term survival benefits to patients, even with the risk of more postoperative pulmonary complications,” said Pierre-Benoit Pagès, MD, PhD, and his coauthors in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:184-95). Dr. Pagès is with the department of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University Hospital Center Dijon (France) and Bocage Hospital.

Three-year overall survival was 71.9% for the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 60.8% for the pneumonectomy group. Three-year disease-free survival was 46.4% for the sleeve lobectomy group and 31.6% for the pneumonectomy group. In addition, compared with the sleeve lobectomy group, the pneumonectomy group had an increased risk of recurrence by matching (hazard ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.1-2).

The researchers performed a propensity-matched analysis that favored sleeve lobectomy for early overall and disease-free survival, but the weighted analysis did not. Patients in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. the pneumonectomy group were younger (60.9 years vs. 61.9), had higher body mass index (25.6 vs. 25.1), had higher average forced expiratory volume (74.1% vs. 62.9%), and had lower American Society of Anesthesiologists scores (73.7% with scores of 1 and 2 vs. 70.8%). Sleeve lobectomy patients also were more likely to have right-sided surgery (69.6% vs. 41%) and squamous cell carcinoma (54.6% vs. 48.3%), and lower T and N stages (T1 and T2, 60.5% vs. 40.6%; N0, 40.9% vs. 26.2%).

Overall mortality after surgery was 5% in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 5.9% in the pneumonectomy group, but propensity scoring showed far fewer postoperative pulmonary complications in the pneumonectomy group, with an odds ratio of 0.4, Dr. Pagès and his coauthors said. However, with other significant complications – arrhythmia, bronchopleural fistula, empyema, and hemorrhage – pneumonectomy had a propensity-matched odds ratio ranging from 1.6 to 7. “We found no significant difference regarding postoperative mortality in the sleeve lobectomy and pneumonectomy groups, whatever the statistical method used,” Dr. Pagès and his coauthors wrote.

The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

Guidelines that recommend sleeve lobectomy as a means of avoiding pneumonectomy for lung cancer have been based on a limited retrospective series, but a large series drawn from a nationwide database in France has confirmed the preference for sleeve lobectomy because it leads to higher rates of survival, despite an increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications.

“Whenever it is technically possible, surgeons must perform sleeve lobectomy to provide more long-term survival benefits to patients, even with the risk of more postoperative pulmonary complications,” said Pierre-Benoit Pagès, MD, PhD, and his coauthors in the January 2017 issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:184-95). Dr. Pagès is with the department of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University Hospital Center Dijon (France) and Bocage Hospital.

Three-year overall survival was 71.9% for the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 60.8% for the pneumonectomy group. Three-year disease-free survival was 46.4% for the sleeve lobectomy group and 31.6% for the pneumonectomy group. In addition, compared with the sleeve lobectomy group, the pneumonectomy group had an increased risk of recurrence by matching (hazard ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.1-2).

The researchers performed a propensity-matched analysis that favored sleeve lobectomy for early overall and disease-free survival, but the weighted analysis did not. Patients in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. the pneumonectomy group were younger (60.9 years vs. 61.9), had higher body mass index (25.6 vs. 25.1), had higher average forced expiratory volume (74.1% vs. 62.9%), and had lower American Society of Anesthesiologists scores (73.7% with scores of 1 and 2 vs. 70.8%). Sleeve lobectomy patients also were more likely to have right-sided surgery (69.6% vs. 41%) and squamous cell carcinoma (54.6% vs. 48.3%), and lower T and N stages (T1 and T2, 60.5% vs. 40.6%; N0, 40.9% vs. 26.2%).

Overall mortality after surgery was 5% in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 5.9% in the pneumonectomy group, but propensity scoring showed far fewer postoperative pulmonary complications in the pneumonectomy group, with an odds ratio of 0.4, Dr. Pagès and his coauthors said. However, with other significant complications – arrhythmia, bronchopleural fistula, empyema, and hemorrhage – pneumonectomy had a propensity-matched odds ratio ranging from 1.6 to 7. “We found no significant difference regarding postoperative mortality in the sleeve lobectomy and pneumonectomy groups, whatever the statistical method used,” Dr. Pagès and his coauthors wrote.

The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

Key clinical point: Sleeve lobectomy for non–small cell lung cancer may lead to higher rates of overall and disease-free survival vs. pneumonectomy.

Major finding: Overall postoperative mortality was 5% in the sleeve lobectomy group vs. 5.9% in the pneumonectomy group.

Data source: An analysis of 941 sleeve lobectomy and 5,318 pneumonectomy procedures from 2005 to 2014 in the nationwide French database Epithor.

Disclosures: Dr. Pagès has received research grants from the Nuovo-Soldati Foundation for Cancer Research and the French Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, on whose behalf the study was performed. Dr. Pagès and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Female physicians, lower mortality, lower readmissions: A case study

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Gastrografin IDs, treats suspected small bowel obstruction

HOLLYWOOD, FLA – The radiopaque contrast agent Gastrografin accurately diagnosed the majority of small bowel obstructions, allowing surgeons to identify which patients needed emergent surgery and which could be managed conservatively.

When instilled via nasogastric tube, the diatrizoate solution had a 92% positive predictive value for adhesive small bowel obstruction, Martin D. Zielinski, MD, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Dr. Zielinski of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., examined the diagnostic accuracy of the Gastrografin challenge, a small bowel obstruction diagnosis and treatment protocol he developed at the center. The challenge begins with 2 hours of nasogastric suctioning. Patients then receive 100 mL Gastrografin mixed with 50 mL water via the nasogastric tube. The tube is clamped for 8 hours, and then patients have an abdominal x-ray. If the contrast material appears in the colon, or if the patient has a bowel movement in the interim, then the challenge is passed, the tube can be removed, and diet advanced.

If there is no contrast in the colon, or if the patient has no bowel movement, then the surgeon assumes the obstruction remains, and exploratory surgery proceeds.

Dr. Zielinski’s study comprised 316 patients with a suspected adhesive small bowel obstruction. Of these, 173 were managed with the Gastrografin challenge; they were compared to 143 patients who were managed without the contrast agent.

Patients were a mean of 58 years. There were no significant differences in the rate of prior abdominal operations; duration of obstipation; or small bowel feces sign.

The comparator group was managed by a clinical algorithm in which any patient with initial signs of ischemia underwent exploratory surgery, and those without signs of ischemia were managed symptomatically. Patients in the Gastrografin arm who passed the trial were similarly managed, while those who failed it underwent exploratory surgery.

Among those who had the challenge, 130 (75%) passed. Gastrografin had a high diagnostic accuracy for small bowel obstruction, with 87% sensitivity, 71% specificity; and 92% positive predictive value. The negative predictive value was not as good, at 59%.

The Gastrografin protocol was associated with significantly fewer exploratory surgeries (21% vs. 44%), and significantly fewer small bowel resections (7% vs. 21%). That advantage was maintained even among patients in both groups who underwent exploratory surgery, with an ultimate resection rate of 34% vs. 49%. The length of stay was also significantly less in the Gastrografin group, 4 vs. 5 days).

There was no difference in the overall complication rate (12.5% vs. 18%). Complications included acute kidney injury (6% vs. 9%); pneumonia (4% vs. 5%), organ space infection (1% vs. 4%), surgical site infection (3.5% vs. 5%), and anastomotic leak (2% each group).

The rate of missed small bowel strangulation was significantly lower among the Gastrografin group as well (0.6% vs. 7.7%). There were no cases of Gastrografin pneumonitis.

Dr. Zielinski had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

HOLLYWOOD, FLA – The radiopaque contrast agent Gastrografin accurately diagnosed the majority of small bowel obstructions, allowing surgeons to identify which patients needed emergent surgery and which could be managed conservatively.

When instilled via nasogastric tube, the diatrizoate solution had a 92% positive predictive value for adhesive small bowel obstruction, Martin D. Zielinski, MD, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Dr. Zielinski of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., examined the diagnostic accuracy of the Gastrografin challenge, a small bowel obstruction diagnosis and treatment protocol he developed at the center. The challenge begins with 2 hours of nasogastric suctioning. Patients then receive 100 mL Gastrografin mixed with 50 mL water via the nasogastric tube. The tube is clamped for 8 hours, and then patients have an abdominal x-ray. If the contrast material appears in the colon, or if the patient has a bowel movement in the interim, then the challenge is passed, the tube can be removed, and diet advanced.

If there is no contrast in the colon, or if the patient has no bowel movement, then the surgeon assumes the obstruction remains, and exploratory surgery proceeds.

Dr. Zielinski’s study comprised 316 patients with a suspected adhesive small bowel obstruction. Of these, 173 were managed with the Gastrografin challenge; they were compared to 143 patients who were managed without the contrast agent.

Patients were a mean of 58 years. There were no significant differences in the rate of prior abdominal operations; duration of obstipation; or small bowel feces sign.

The comparator group was managed by a clinical algorithm in which any patient with initial signs of ischemia underwent exploratory surgery, and those without signs of ischemia were managed symptomatically. Patients in the Gastrografin arm who passed the trial were similarly managed, while those who failed it underwent exploratory surgery.

Among those who had the challenge, 130 (75%) passed. Gastrografin had a high diagnostic accuracy for small bowel obstruction, with 87% sensitivity, 71% specificity; and 92% positive predictive value. The negative predictive value was not as good, at 59%.

The Gastrografin protocol was associated with significantly fewer exploratory surgeries (21% vs. 44%), and significantly fewer small bowel resections (7% vs. 21%). That advantage was maintained even among patients in both groups who underwent exploratory surgery, with an ultimate resection rate of 34% vs. 49%. The length of stay was also significantly less in the Gastrografin group, 4 vs. 5 days).

There was no difference in the overall complication rate (12.5% vs. 18%). Complications included acute kidney injury (6% vs. 9%); pneumonia (4% vs. 5%), organ space infection (1% vs. 4%), surgical site infection (3.5% vs. 5%), and anastomotic leak (2% each group).

The rate of missed small bowel strangulation was significantly lower among the Gastrografin group as well (0.6% vs. 7.7%). There were no cases of Gastrografin pneumonitis.

Dr. Zielinski had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

HOLLYWOOD, FLA – The radiopaque contrast agent Gastrografin accurately diagnosed the majority of small bowel obstructions, allowing surgeons to identify which patients needed emergent surgery and which could be managed conservatively.

When instilled via nasogastric tube, the diatrizoate solution had a 92% positive predictive value for adhesive small bowel obstruction, Martin D. Zielinski, MD, said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Dr. Zielinski of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., examined the diagnostic accuracy of the Gastrografin challenge, a small bowel obstruction diagnosis and treatment protocol he developed at the center. The challenge begins with 2 hours of nasogastric suctioning. Patients then receive 100 mL Gastrografin mixed with 50 mL water via the nasogastric tube. The tube is clamped for 8 hours, and then patients have an abdominal x-ray. If the contrast material appears in the colon, or if the patient has a bowel movement in the interim, then the challenge is passed, the tube can be removed, and diet advanced.

If there is no contrast in the colon, or if the patient has no bowel movement, then the surgeon assumes the obstruction remains, and exploratory surgery proceeds.

Dr. Zielinski’s study comprised 316 patients with a suspected adhesive small bowel obstruction. Of these, 173 were managed with the Gastrografin challenge; they were compared to 143 patients who were managed without the contrast agent.

Patients were a mean of 58 years. There were no significant differences in the rate of prior abdominal operations; duration of obstipation; or small bowel feces sign.

The comparator group was managed by a clinical algorithm in which any patient with initial signs of ischemia underwent exploratory surgery, and those without signs of ischemia were managed symptomatically. Patients in the Gastrografin arm who passed the trial were similarly managed, while those who failed it underwent exploratory surgery.

Among those who had the challenge, 130 (75%) passed. Gastrografin had a high diagnostic accuracy for small bowel obstruction, with 87% sensitivity, 71% specificity; and 92% positive predictive value. The negative predictive value was not as good, at 59%.

The Gastrografin protocol was associated with significantly fewer exploratory surgeries (21% vs. 44%), and significantly fewer small bowel resections (7% vs. 21%). That advantage was maintained even among patients in both groups who underwent exploratory surgery, with an ultimate resection rate of 34% vs. 49%. The length of stay was also significantly less in the Gastrografin group, 4 vs. 5 days).

There was no difference in the overall complication rate (12.5% vs. 18%). Complications included acute kidney injury (6% vs. 9%); pneumonia (4% vs. 5%), organ space infection (1% vs. 4%), surgical site infection (3.5% vs. 5%), and anastomotic leak (2% each group).

The rate of missed small bowel strangulation was significantly lower among the Gastrografin group as well (0.6% vs. 7.7%). There were no cases of Gastrografin pneumonitis.

Dr. Zielinski had no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE EAST ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: The bowel-imaging agent Gastrografin can both diagnose and treat small bowel obstruction.

Major finding: The agent had a 92% positive predictive value; it was associated with fewer bowel resections (7% vs. 21%) and a day shorter length of stay, compared with those who didn’t receive it.

Data source: The prospective study comprised 316 patients, 173 of whom underwent the Gastrografin challenge.

Disclosures: Dr. Zielinski had no financial disclosures.

Childhood PCV program produces overall protection

Childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccines continue to indirectly produce widespread societal protection against invasive pneumococcal disease, a review and meta-analysis showed.

In fact, the reviewed studies suggest that the use of these vaccines in children can lead to an overall 90% drop in invasive pneumococcal disease within fewer than 10 years.

Herd immunity appears to be at work, the review authors said. The effect is so powerful that the findings raise questions about “the merit of offering [the 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine] in older groups” in places that have a children’s pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) program, the investigators said.

U.S. guidelines recommend vaccinations for older people, although the recommendations are up for review in 2018.

According to the review, childhood PCVs have had a tremendous impact since a seven-valent version (PCV7) was first released in 2000. “In vaccinated young children, disease due to serotypes included in the vaccines has been reduced to negligible levels,” the authors wrote.

But unvaccinated people, especially the elderly, remain susceptible.

The review authors, led by Tinevimbo Shiri, PhD, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, updated a 2013 systemic review (Vaccine. 2013 Dec 17;32[1]:133-45). They focused on studies from 1994 to 2016 that examined the effects of introducing PCV in children.

A total of 242 studies were included in the meta-analysis, published in the January issue of Lancet Global Health (2017 Jan;5[1]:e51-e9), including 70 from the previous review. Of these, only 9 (4%) were performed in poor or middle-income countries, with most of the rest having been done in North America (42%) and Europe (38%).

The researchers found that “[herd] immunity effects continued to accumulate over time and reduced disease due to PCV7 serotypes, for which follow-up data have generally been available for the longest period, with a 90% average reduction after about 9 years.”

Specifically, the review estimated it would take 8.9 years for a 90% reduction in invasive pneumococcal disease for grouped serotypes in the PCV7 and 9.5 years for the extra six grouped serotypes in the 13-valent PCV. The latter vaccine was introduced in 2010.

The researchers found evidence of a similar annual reduction in disease linked to grouped serotypes in the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in adults aged 19 and up. They noted that the 11 serotypes contained in PPV23 but not in PCV13 “did not change invasive pneumococcal disease at any age.”