User login

Seeing Redness and Ear-itation

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is relapsing polychondritis (RP; choice “a”). The lack of surface changes in the affected skin rules out contact dermatitis, while the lack of a positive response to antibiotics and absence of an entrance wound eliminate the possibility of an infectious etiology.

DISCUSSION

There are no tests to confirm the diagnosis of RP. It is a rare autoimmune condition that usually manifests in the later decades of life and equally affects men and women.

RP’s ability to appear in cartilage anywhere in the body and in a variety of forms makes timely diagnosis almost impossible. But this case illustrates some diagnostically useful signs to watch for.

The unexplained erythema in the ear, which very obviously spared the cartilage-free lobe, prompted a biopsy of the cartilage; this showed changes consistent with RP. A subsequent review of the patient’s ophthalmology records indicated a chronic episcleritis, most likely due to inflammation of eyelid cartilage.

Further testing was performed to rule out other explanations, such as gout, or autoimmune diseases, such as lupus. Results were negative.

The patient was then referred to a pulmonologist, who found no respiratory involvement, and a rheumatologist, for further evaluation (including blood work) to rule out other conditions and end-organ (eg, renal) involvement.

On follow-up, the patient was responding well to prednisone prescribed by her rheumatologist. Given her limited disease, her prognosis is fairly good.

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is relapsing polychondritis (RP; choice “a”). The lack of surface changes in the affected skin rules out contact dermatitis, while the lack of a positive response to antibiotics and absence of an entrance wound eliminate the possibility of an infectious etiology.

DISCUSSION

There are no tests to confirm the diagnosis of RP. It is a rare autoimmune condition that usually manifests in the later decades of life and equally affects men and women.

RP’s ability to appear in cartilage anywhere in the body and in a variety of forms makes timely diagnosis almost impossible. But this case illustrates some diagnostically useful signs to watch for.

The unexplained erythema in the ear, which very obviously spared the cartilage-free lobe, prompted a biopsy of the cartilage; this showed changes consistent with RP. A subsequent review of the patient’s ophthalmology records indicated a chronic episcleritis, most likely due to inflammation of eyelid cartilage.

Further testing was performed to rule out other explanations, such as gout, or autoimmune diseases, such as lupus. Results were negative.

The patient was then referred to a pulmonologist, who found no respiratory involvement, and a rheumatologist, for further evaluation (including blood work) to rule out other conditions and end-organ (eg, renal) involvement.

On follow-up, the patient was responding well to prednisone prescribed by her rheumatologist. Given her limited disease, her prognosis is fairly good.

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is relapsing polychondritis (RP; choice “a”). The lack of surface changes in the affected skin rules out contact dermatitis, while the lack of a positive response to antibiotics and absence of an entrance wound eliminate the possibility of an infectious etiology.

DISCUSSION

There are no tests to confirm the diagnosis of RP. It is a rare autoimmune condition that usually manifests in the later decades of life and equally affects men and women.

RP’s ability to appear in cartilage anywhere in the body and in a variety of forms makes timely diagnosis almost impossible. But this case illustrates some diagnostically useful signs to watch for.

The unexplained erythema in the ear, which very obviously spared the cartilage-free lobe, prompted a biopsy of the cartilage; this showed changes consistent with RP. A subsequent review of the patient’s ophthalmology records indicated a chronic episcleritis, most likely due to inflammation of eyelid cartilage.

Further testing was performed to rule out other explanations, such as gout, or autoimmune diseases, such as lupus. Results were negative.

The patient was then referred to a pulmonologist, who found no respiratory involvement, and a rheumatologist, for further evaluation (including blood work) to rule out other conditions and end-organ (eg, renal) involvement.

On follow-up, the patient was responding well to prednisone prescribed by her rheumatologist. Given her limited disease, her prognosis is fairly good.

Several months ago, family members pointed out that this 60-year-old woman’s left ear was red. She consulted her primary care provider, who prescribed antibiotics. But when these failed to clear the problem, she was referred to dermatology.

Today, the patient complains of some discomfort in the ear but denies actual pain; she is, for example, able to sleep despite the problem. She reports that the redness manifested slowly but has spread over time to encompass most of her ear.

Uniformly distributed, bright red erythema on the left ear spares only the lobe. No wound or epidermal component (eg, scaling or blistering) is noted. However, there is increased warmth and tenderness on palpation of the erythematous portion. No nodes can be felt in the vicinity, nor are any abnormalities observed in the other ear.

The patient denies other skin problems, joint pain, and breathing difficulty. But she does have an ongoing history of irritation in both eyes. She has been seeing an ophthalmologist for months without relief. On examination, both eyes appear injected, with slightly swollen eyelids. Inspection and palpation of the nose reveal no abnormalities.

HIV update: Legalizing sex work, novel one-drug therapy, concomitant opioid use

Here’s your weekly quick take on recent notable news and journal articles related to HIV and AIDS research:

Novel therapy tested. An unboosted HIV-1 integrase strand-transfer inhibitor produced led to rapid declines in HIV-1 RNA after 10 days of monotherapy in a phase 1B study reported in JAIDS. The drug (bictegravir) was well tolerated, and displayed rapid absorption and a half-life supportive of once-daily therapy in HIV-infected subjects.

New diagnoses declining in black women. Based on three different measures, the disparity in HIV diagnoses in black women decreased in 2014, compared with 2010, according to a CDC report.

Legalizing sex work is linked to lower HIV rates. Rates of HIV infection in female sex workers are lower in European countries that have legalized of some aspects of sex work, according to a study in the Lancet HIV.

Flu vaccine likely safe in HIV-positive women on therapy. H1N1 influenza vaccination in HIV-infected women on effective antiretroviral treatment did not induce measurable antigen-driven proliferation of the HIV-1 proviral reservoir, according to a study in AIDS Research and Therapy.

Could vitamin supplements lower subsequent TB risk? At the start of ART, vitamin A and D deficiencies were more common in adults who went on to develop tuberculosis, according to a study in JAIDS.

Cerebrospinal fluid CD8+ T cells beneficial in acute HIV infection. CD8+ T cells expand in the central nervous system during acute HIV infection and are functional and directed against HIV antigens. If combination antiretroviral therapy is initiated early, the cells could protect against injury seen in chronic HIV infection based on a study in JAIDS.

Opioid use declined with HIV care. Opioid prescription use decreased substantially with longer time in HIV care among both episodic and chronic opioid users infected with HIV, according to a study in JAIDS.

HIV treatment goals need to improve. Meeting the National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals will require more efforts to link and retain black patients to care. Among blacks living with diagnosed HIV at year-end 2013, 53.5% were retained in care and 48.5% achieved viral suppression. The lowest levels of care and viral suppression were among persons with infection attributed to injection drug use and males with infection attributed to heterosexual contact, according to a report in MMWR. The strategy goals are 85% linkage to care, 90% retention in care, and 80% viral load suppression by 2020.

[email protected]

On Twitter @richpizzi

Here’s your weekly quick take on recent notable news and journal articles related to HIV and AIDS research:

Novel therapy tested. An unboosted HIV-1 integrase strand-transfer inhibitor produced led to rapid declines in HIV-1 RNA after 10 days of monotherapy in a phase 1B study reported in JAIDS. The drug (bictegravir) was well tolerated, and displayed rapid absorption and a half-life supportive of once-daily therapy in HIV-infected subjects.

New diagnoses declining in black women. Based on three different measures, the disparity in HIV diagnoses in black women decreased in 2014, compared with 2010, according to a CDC report.

Legalizing sex work is linked to lower HIV rates. Rates of HIV infection in female sex workers are lower in European countries that have legalized of some aspects of sex work, according to a study in the Lancet HIV.

Flu vaccine likely safe in HIV-positive women on therapy. H1N1 influenza vaccination in HIV-infected women on effective antiretroviral treatment did not induce measurable antigen-driven proliferation of the HIV-1 proviral reservoir, according to a study in AIDS Research and Therapy.

Could vitamin supplements lower subsequent TB risk? At the start of ART, vitamin A and D deficiencies were more common in adults who went on to develop tuberculosis, according to a study in JAIDS.

Cerebrospinal fluid CD8+ T cells beneficial in acute HIV infection. CD8+ T cells expand in the central nervous system during acute HIV infection and are functional and directed against HIV antigens. If combination antiretroviral therapy is initiated early, the cells could protect against injury seen in chronic HIV infection based on a study in JAIDS.

Opioid use declined with HIV care. Opioid prescription use decreased substantially with longer time in HIV care among both episodic and chronic opioid users infected with HIV, according to a study in JAIDS.

HIV treatment goals need to improve. Meeting the National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals will require more efforts to link and retain black patients to care. Among blacks living with diagnosed HIV at year-end 2013, 53.5% were retained in care and 48.5% achieved viral suppression. The lowest levels of care and viral suppression were among persons with infection attributed to injection drug use and males with infection attributed to heterosexual contact, according to a report in MMWR. The strategy goals are 85% linkage to care, 90% retention in care, and 80% viral load suppression by 2020.

[email protected]

On Twitter @richpizzi

Here’s your weekly quick take on recent notable news and journal articles related to HIV and AIDS research:

Novel therapy tested. An unboosted HIV-1 integrase strand-transfer inhibitor produced led to rapid declines in HIV-1 RNA after 10 days of monotherapy in a phase 1B study reported in JAIDS. The drug (bictegravir) was well tolerated, and displayed rapid absorption and a half-life supportive of once-daily therapy in HIV-infected subjects.

New diagnoses declining in black women. Based on three different measures, the disparity in HIV diagnoses in black women decreased in 2014, compared with 2010, according to a CDC report.

Legalizing sex work is linked to lower HIV rates. Rates of HIV infection in female sex workers are lower in European countries that have legalized of some aspects of sex work, according to a study in the Lancet HIV.

Flu vaccine likely safe in HIV-positive women on therapy. H1N1 influenza vaccination in HIV-infected women on effective antiretroviral treatment did not induce measurable antigen-driven proliferation of the HIV-1 proviral reservoir, according to a study in AIDS Research and Therapy.

Could vitamin supplements lower subsequent TB risk? At the start of ART, vitamin A and D deficiencies were more common in adults who went on to develop tuberculosis, according to a study in JAIDS.

Cerebrospinal fluid CD8+ T cells beneficial in acute HIV infection. CD8+ T cells expand in the central nervous system during acute HIV infection and are functional and directed against HIV antigens. If combination antiretroviral therapy is initiated early, the cells could protect against injury seen in chronic HIV infection based on a study in JAIDS.

Opioid use declined with HIV care. Opioid prescription use decreased substantially with longer time in HIV care among both episodic and chronic opioid users infected with HIV, according to a study in JAIDS.

HIV treatment goals need to improve. Meeting the National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals will require more efforts to link and retain black patients to care. Among blacks living with diagnosed HIV at year-end 2013, 53.5% were retained in care and 48.5% achieved viral suppression. The lowest levels of care and viral suppression were among persons with infection attributed to injection drug use and males with infection attributed to heterosexual contact, according to a report in MMWR. The strategy goals are 85% linkage to care, 90% retention in care, and 80% viral load suppression by 2020.

[email protected]

On Twitter @richpizzi

Rotavirus vaccine and PCV reduce hospital burden of young children

Vaccination programs targeting rotavirus and pneumonia in children younger than 2 years both contributed to a “rapid and considerable” decline in the hospital burden of pediatric patients, both in relation to those diseases and overall, according to an observational study.

Three vaccines were added to the National Immunization Plan in Israel within a 1.5-year interval, between July 2009 and January 2011: rotavirus vaccine and the 7-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV). Researchers studied the population at the Soroka University Medical Center in Beer Sheva, Israel, which was split roughly 50/50 between Jewish children and Bedouin Muslim children.

The rates of rotavirus gastroenteritis, nonrotavirus gastroenteritis, alveolar pneumonia, and nonalveolar lower respiratory tract infections in the 37,591 hospitalized children younger than 2 years declined by 78%, 21%, 46%, and 7%, respectively, over the course of the study period. Outpatient ED visits for the same diseases declined 80%, 16%, 67%, and 13%, respectively.

The results are more evidence that rotavirus vaccine can help prevent diarrhea not caused by rotavirus and, similarly, that PCV can help prevent lower respiratory tract infections not caused by pneumococci.

Overall, hospitalizations and outpatient ED visits also declined significantly, by 11% and 12%, respectively.

“The impact of [rotavirus vaccine] and PCV may not be limited to prevention of diarrhea and respiratory disease, respectively. In one study, it was suggested that diarrhea may increase the risk of subsequent pneumonia in young children, pointing to potential synergistic benefits” of the vaccines, the authors wrote (Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162[10]:999-1007).

The study was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Pfizer. Authors received speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from those companies and from GlaxoSmithKline.

Vaccination programs targeting rotavirus and pneumonia in children younger than 2 years both contributed to a “rapid and considerable” decline in the hospital burden of pediatric patients, both in relation to those diseases and overall, according to an observational study.

Three vaccines were added to the National Immunization Plan in Israel within a 1.5-year interval, between July 2009 and January 2011: rotavirus vaccine and the 7-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV). Researchers studied the population at the Soroka University Medical Center in Beer Sheva, Israel, which was split roughly 50/50 between Jewish children and Bedouin Muslim children.

The rates of rotavirus gastroenteritis, nonrotavirus gastroenteritis, alveolar pneumonia, and nonalveolar lower respiratory tract infections in the 37,591 hospitalized children younger than 2 years declined by 78%, 21%, 46%, and 7%, respectively, over the course of the study period. Outpatient ED visits for the same diseases declined 80%, 16%, 67%, and 13%, respectively.

The results are more evidence that rotavirus vaccine can help prevent diarrhea not caused by rotavirus and, similarly, that PCV can help prevent lower respiratory tract infections not caused by pneumococci.

Overall, hospitalizations and outpatient ED visits also declined significantly, by 11% and 12%, respectively.

“The impact of [rotavirus vaccine] and PCV may not be limited to prevention of diarrhea and respiratory disease, respectively. In one study, it was suggested that diarrhea may increase the risk of subsequent pneumonia in young children, pointing to potential synergistic benefits” of the vaccines, the authors wrote (Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162[10]:999-1007).

The study was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Pfizer. Authors received speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from those companies and from GlaxoSmithKline.

Vaccination programs targeting rotavirus and pneumonia in children younger than 2 years both contributed to a “rapid and considerable” decline in the hospital burden of pediatric patients, both in relation to those diseases and overall, according to an observational study.

Three vaccines were added to the National Immunization Plan in Israel within a 1.5-year interval, between July 2009 and January 2011: rotavirus vaccine and the 7-valent and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV). Researchers studied the population at the Soroka University Medical Center in Beer Sheva, Israel, which was split roughly 50/50 between Jewish children and Bedouin Muslim children.

The rates of rotavirus gastroenteritis, nonrotavirus gastroenteritis, alveolar pneumonia, and nonalveolar lower respiratory tract infections in the 37,591 hospitalized children younger than 2 years declined by 78%, 21%, 46%, and 7%, respectively, over the course of the study period. Outpatient ED visits for the same diseases declined 80%, 16%, 67%, and 13%, respectively.

The results are more evidence that rotavirus vaccine can help prevent diarrhea not caused by rotavirus and, similarly, that PCV can help prevent lower respiratory tract infections not caused by pneumococci.

Overall, hospitalizations and outpatient ED visits also declined significantly, by 11% and 12%, respectively.

“The impact of [rotavirus vaccine] and PCV may not be limited to prevention of diarrhea and respiratory disease, respectively. In one study, it was suggested that diarrhea may increase the risk of subsequent pneumonia in young children, pointing to potential synergistic benefits” of the vaccines, the authors wrote (Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162[10]:999-1007).

The study was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Pfizer. Authors received speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from those companies and from GlaxoSmithKline.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rates of rotavirus gastroenteritis, nonrotavirus gastroenteritis, alveolar pneumonia, and nonalveolar lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized children younger than 2 years declined by 78%, 21%, 46%, and 7%, respectively, over the course of the study period.

Data source: A prospective, population-based observational study of one hospital in southern Israel.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme and Pfizer. Authors received speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from those companies and from GlaxoSmithKline.

In Oregon pertussis outbreak, unvaccinated children were affected earlier

were, according to Steve G. Robison, MPH, and Juventila Liko, MD, MPH, from the Immunization Program, Oregon Health Authority, Portland.

A total of 351 pertussis cases in children aged 2 months to 10 years were reported in Portland and the upper Willamette Valley from Jan. 1 to Nov. 1, 2012. Children who were unvaccinated accounted for 76 (22%) of the reported cases, and children who were poorly vaccinated accounted for 50 of the 275 (18%) cases in vaccinated children.

“Children who are not immunized represent a dynamic risk of spreading disease in an outbreak and have an impact that is greater than simply lessening overall community immunity levels. Diseases such as pertussis may spread across areas through the choice of parents to not immunize or to limit immunizations. Once locally present, pertussis will spread to the unimmunized and vulnerable, who in turn through the weight of exposure, may then ignite a wider outbreak in vaccinated populations,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study in the Journal of Pediatrics (doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.047).

were, according to Steve G. Robison, MPH, and Juventila Liko, MD, MPH, from the Immunization Program, Oregon Health Authority, Portland.

A total of 351 pertussis cases in children aged 2 months to 10 years were reported in Portland and the upper Willamette Valley from Jan. 1 to Nov. 1, 2012. Children who were unvaccinated accounted for 76 (22%) of the reported cases, and children who were poorly vaccinated accounted for 50 of the 275 (18%) cases in vaccinated children.

“Children who are not immunized represent a dynamic risk of spreading disease in an outbreak and have an impact that is greater than simply lessening overall community immunity levels. Diseases such as pertussis may spread across areas through the choice of parents to not immunize or to limit immunizations. Once locally present, pertussis will spread to the unimmunized and vulnerable, who in turn through the weight of exposure, may then ignite a wider outbreak in vaccinated populations,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study in the Journal of Pediatrics (doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.047).

were, according to Steve G. Robison, MPH, and Juventila Liko, MD, MPH, from the Immunization Program, Oregon Health Authority, Portland.

A total of 351 pertussis cases in children aged 2 months to 10 years were reported in Portland and the upper Willamette Valley from Jan. 1 to Nov. 1, 2012. Children who were unvaccinated accounted for 76 (22%) of the reported cases, and children who were poorly vaccinated accounted for 50 of the 275 (18%) cases in vaccinated children.

“Children who are not immunized represent a dynamic risk of spreading disease in an outbreak and have an impact that is greater than simply lessening overall community immunity levels. Diseases such as pertussis may spread across areas through the choice of parents to not immunize or to limit immunizations. Once locally present, pertussis will spread to the unimmunized and vulnerable, who in turn through the weight of exposure, may then ignite a wider outbreak in vaccinated populations,” the investigators noted.

Find the full study in the Journal of Pediatrics (doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.047).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

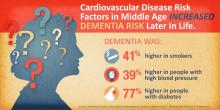

Mid-life cardiovascular risk factors set stage for later-life dementia

HOUSTON – Cardiovascular risk factors present in middle age may presage dementia in later years, a subanalysis of a 25-year atherosclerosis study has determined.

Diabetes conferred the greatest dementia risk, nearly doubling the chance of dementia, Rebecca Gottesman, MD, PhD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“In fact, the risk associated with diabetes nears the increased risk associated with having an APOE4 [apolipoprotein E epsilon 4] allele,” said Dr. Gottesman of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Her subanalysis of the biracial ARIC-NCS (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study) also identified some racial differences in risk, with blacks being more vulnerable to the risk imposed by diabetes, and whites more vulnerable to the hypertension-associated risk.

The ARIC study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, is a prospective epidemiologic study conducted in four U.S. communities. ARIC is designed to investigate the causes of atherosclerosis and its clinical outcomes, and variation in cardiovascular risk factors, medical care, and disease by race, gender, location, and date. To date, the ARIC project has published over 800 articles in peer-reviewed journals. A total of 15,792 participants received an extensive examination, including medical, social, and demographic data. These participants were reexamined every 3 years with the first screen occurring in 1987-1989. Follow-up occurs yearly by telephone to maintain contact with participants and to assess the health status of the cohort.

ARIC-NCS comprises about 10,000 of these subjects. Of these, 6,471 completed the fifth visit, which occurred during 2011-2013. They have undergone cognitive, neurologic, and brain imaging assessments to diagnose mild cognitive impairment or dementia and assign an etiology for the cognitive disorder. Last year, investigators published the study’s primary findings: Nearly 30% had a diagnosis of either dementia or mild cognitive impairment.

Dr. Gottesman sought to determine the extent to which these subjects’ baseline cardiovascular risk factors influenced their chances of cognitive decline or dementia. She assessed risk for the entire cohort, and then for black and white subjects separately.

Dementia was present in 1,516 cases (23%). In the total cohort, dementia was – not surprisingly – significantly associated with increasing age. Subjects aged 50-54 years had twice the risk for dementia when compared with younger subjects, while those aged 60-66 years had eight times greater risk. Black race conferred a 30% increased risk, compared with white race (hazard ratio, 1.3). Education of less than a high school degree was associated with a 40% increased risk. Having at least one copy of the APOE4 allele doubled the risk.

Diabetes was second only to genetic status, increasing the risk by 80%.

Dr. Gottesman then divided the cohort by race and reexamined these risk factors separately. She found some significant differences in the way these factors affected risk in white and black subjects.

Age exerted a greater influence on dementia risks in whites than it did in blacks. The risk was about doubled in both groups for people aged 50-54 years. But at age 55-59 years, it was significantly higher in whites than in blacks (HR, 4.37 vs. 3.53). The risk differential was even greater between whites and blacks aged 60-66 years (HR, 9.5 vs. 6.2).

Blacks with low education were more vulnerable to dementia than were whites (HR, 1.6 vs. 1.29). APOE4 status (at least one allele) more than doubled the risk of dementia for whites (HR, 2.23) but was not as strong in blacks (HR, 1.61).

Obesity was riskier for whites, increasing the risk of dementia by 22%, but it had no influence on risk among blacks. Current smoking increased the risk for whites by 62% but was not a significant risk factor for blacks. Prehypertension also affected whites more, increasing the risk by 35%, compared with a nonsignificant 17% for blacks. Full-blown hypertension increased the risk of dementia similarly in both groups (37% and 36%, respectively).

Diabetes increased the risk of dementia more in blacks than it did in whites (85% vs. 69%).

“We don’t have a clear explanation of these disparities in dementia risk with regard to race,” Dr. Gottesman said. “It could be, though, that even if a risk factor has the same relationship with dementia in both groups, if it is more prevalent in one group, that may somewhat account for this larger population attributable risk.”

She had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

HOUSTON – Cardiovascular risk factors present in middle age may presage dementia in later years, a subanalysis of a 25-year atherosclerosis study has determined.

Diabetes conferred the greatest dementia risk, nearly doubling the chance of dementia, Rebecca Gottesman, MD, PhD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“In fact, the risk associated with diabetes nears the increased risk associated with having an APOE4 [apolipoprotein E epsilon 4] allele,” said Dr. Gottesman of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Her subanalysis of the biracial ARIC-NCS (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study) also identified some racial differences in risk, with blacks being more vulnerable to the risk imposed by diabetes, and whites more vulnerable to the hypertension-associated risk.

The ARIC study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, is a prospective epidemiologic study conducted in four U.S. communities. ARIC is designed to investigate the causes of atherosclerosis and its clinical outcomes, and variation in cardiovascular risk factors, medical care, and disease by race, gender, location, and date. To date, the ARIC project has published over 800 articles in peer-reviewed journals. A total of 15,792 participants received an extensive examination, including medical, social, and demographic data. These participants were reexamined every 3 years with the first screen occurring in 1987-1989. Follow-up occurs yearly by telephone to maintain contact with participants and to assess the health status of the cohort.

ARIC-NCS comprises about 10,000 of these subjects. Of these, 6,471 completed the fifth visit, which occurred during 2011-2013. They have undergone cognitive, neurologic, and brain imaging assessments to diagnose mild cognitive impairment or dementia and assign an etiology for the cognitive disorder. Last year, investigators published the study’s primary findings: Nearly 30% had a diagnosis of either dementia or mild cognitive impairment.

Dr. Gottesman sought to determine the extent to which these subjects’ baseline cardiovascular risk factors influenced their chances of cognitive decline or dementia. She assessed risk for the entire cohort, and then for black and white subjects separately.

Dementia was present in 1,516 cases (23%). In the total cohort, dementia was – not surprisingly – significantly associated with increasing age. Subjects aged 50-54 years had twice the risk for dementia when compared with younger subjects, while those aged 60-66 years had eight times greater risk. Black race conferred a 30% increased risk, compared with white race (hazard ratio, 1.3). Education of less than a high school degree was associated with a 40% increased risk. Having at least one copy of the APOE4 allele doubled the risk.

Diabetes was second only to genetic status, increasing the risk by 80%.

Dr. Gottesman then divided the cohort by race and reexamined these risk factors separately. She found some significant differences in the way these factors affected risk in white and black subjects.

Age exerted a greater influence on dementia risks in whites than it did in blacks. The risk was about doubled in both groups for people aged 50-54 years. But at age 55-59 years, it was significantly higher in whites than in blacks (HR, 4.37 vs. 3.53). The risk differential was even greater between whites and blacks aged 60-66 years (HR, 9.5 vs. 6.2).

Blacks with low education were more vulnerable to dementia than were whites (HR, 1.6 vs. 1.29). APOE4 status (at least one allele) more than doubled the risk of dementia for whites (HR, 2.23) but was not as strong in blacks (HR, 1.61).

Obesity was riskier for whites, increasing the risk of dementia by 22%, but it had no influence on risk among blacks. Current smoking increased the risk for whites by 62% but was not a significant risk factor for blacks. Prehypertension also affected whites more, increasing the risk by 35%, compared with a nonsignificant 17% for blacks. Full-blown hypertension increased the risk of dementia similarly in both groups (37% and 36%, respectively).

Diabetes increased the risk of dementia more in blacks than it did in whites (85% vs. 69%).

“We don’t have a clear explanation of these disparities in dementia risk with regard to race,” Dr. Gottesman said. “It could be, though, that even if a risk factor has the same relationship with dementia in both groups, if it is more prevalent in one group, that may somewhat account for this larger population attributable risk.”

She had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

HOUSTON – Cardiovascular risk factors present in middle age may presage dementia in later years, a subanalysis of a 25-year atherosclerosis study has determined.

Diabetes conferred the greatest dementia risk, nearly doubling the chance of dementia, Rebecca Gottesman, MD, PhD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“In fact, the risk associated with diabetes nears the increased risk associated with having an APOE4 [apolipoprotein E epsilon 4] allele,” said Dr. Gottesman of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Her subanalysis of the biracial ARIC-NCS (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study) also identified some racial differences in risk, with blacks being more vulnerable to the risk imposed by diabetes, and whites more vulnerable to the hypertension-associated risk.

The ARIC study, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, is a prospective epidemiologic study conducted in four U.S. communities. ARIC is designed to investigate the causes of atherosclerosis and its clinical outcomes, and variation in cardiovascular risk factors, medical care, and disease by race, gender, location, and date. To date, the ARIC project has published over 800 articles in peer-reviewed journals. A total of 15,792 participants received an extensive examination, including medical, social, and demographic data. These participants were reexamined every 3 years with the first screen occurring in 1987-1989. Follow-up occurs yearly by telephone to maintain contact with participants and to assess the health status of the cohort.

ARIC-NCS comprises about 10,000 of these subjects. Of these, 6,471 completed the fifth visit, which occurred during 2011-2013. They have undergone cognitive, neurologic, and brain imaging assessments to diagnose mild cognitive impairment or dementia and assign an etiology for the cognitive disorder. Last year, investigators published the study’s primary findings: Nearly 30% had a diagnosis of either dementia or mild cognitive impairment.

Dr. Gottesman sought to determine the extent to which these subjects’ baseline cardiovascular risk factors influenced their chances of cognitive decline or dementia. She assessed risk for the entire cohort, and then for black and white subjects separately.

Dementia was present in 1,516 cases (23%). In the total cohort, dementia was – not surprisingly – significantly associated with increasing age. Subjects aged 50-54 years had twice the risk for dementia when compared with younger subjects, while those aged 60-66 years had eight times greater risk. Black race conferred a 30% increased risk, compared with white race (hazard ratio, 1.3). Education of less than a high school degree was associated with a 40% increased risk. Having at least one copy of the APOE4 allele doubled the risk.

Diabetes was second only to genetic status, increasing the risk by 80%.

Dr. Gottesman then divided the cohort by race and reexamined these risk factors separately. She found some significant differences in the way these factors affected risk in white and black subjects.

Age exerted a greater influence on dementia risks in whites than it did in blacks. The risk was about doubled in both groups for people aged 50-54 years. But at age 55-59 years, it was significantly higher in whites than in blacks (HR, 4.37 vs. 3.53). The risk differential was even greater between whites and blacks aged 60-66 years (HR, 9.5 vs. 6.2).

Blacks with low education were more vulnerable to dementia than were whites (HR, 1.6 vs. 1.29). APOE4 status (at least one allele) more than doubled the risk of dementia for whites (HR, 2.23) but was not as strong in blacks (HR, 1.61).

Obesity was riskier for whites, increasing the risk of dementia by 22%, but it had no influence on risk among blacks. Current smoking increased the risk for whites by 62% but was not a significant risk factor for blacks. Prehypertension also affected whites more, increasing the risk by 35%, compared with a nonsignificant 17% for blacks. Full-blown hypertension increased the risk of dementia similarly in both groups (37% and 36%, respectively).

Diabetes increased the risk of dementia more in blacks than it did in whites (85% vs. 69%).

“We don’t have a clear explanation of these disparities in dementia risk with regard to race,” Dr. Gottesman said. “It could be, though, that even if a risk factor has the same relationship with dementia in both groups, if it is more prevalent in one group, that may somewhat account for this larger population attributable risk.”

She had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Smoking and hypertension increased the risk of dementia by 40% each; diabetes, by 80%.

Data source: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study study comprised more than 6,000 people.

Disclosures: Dr. Gottesman had no financial disclosures.

Stable response in sickle cell disease patient treated with gene therapy

A teenage boy with sickle cell disease has been successfully treated with a therapy that uses a viral vector to insert functional genes into blood-producing stem cells.

The patient’s positive response to the intervention was first reported in 2015, and his clinical remission was reported in late 2016 at the American Society of Hematology’s annual meeting.

The new report, published online March 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine, contains the first detailed description of the case (2017;376:848-55).

Treatment consisted of LentiGlobin BB305, an engineered lentiviral vector–mediated addition of an antisickling human beta-globin gene (HbAT87Q ) into the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells. The technology was developed by bluebird bio, which partially funded the study and helped design its protocol.

The investigators, led by Marina Cavazzana, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, collected blood-producing stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow. The cells were transduced ex vivo using LentiGlobin BB305.

After the patient underwent 4 days of myeloablation and a 2-day washout period, the transduced stem cells were infused at 5.6x106 CD34+ cells per kilogram. The patient continued receiving red blood cell transfusions until at least 30% healthy hemoglobin with the signature of the introduced gene could be detected.

Neutrophil engraftment occurred at 38 days after transplantation, and platelet engraftment, at 3 months. Red cell transfusions were discontinued at 3 months.

The patient saw vector-bearing healthy cells in the blood increase during the first 3 months after transplantation, the investigators reported, and the cells continue to be produced at stable levels through month 15, which suggests “engraftment of transduced stem cells that were capable of long-term repopulation,” the investigators wrote.

Also at 15 months after transplantation, the patient had 48% HbAT87Q, while 30% healthy hemoglobin is considered sufficient to see clinical improvement in SCD patients.

The patient has not experienced sickle cell disease–related clinical events or hospitalization since transplantation, Dr. Cavazzana and her colleagues reported, noting all his medications, including pain medication, have been stopped.

Most adverse events seen in the study were associated with busulfan, the drug used in myeloablation, and no adverse events were associated with the gene therapy itself.

These results, the investigators concluded, provide proof of concept for lentiviral vectors in delivering this gene therapy for SCD. This approach, they said, “may help to guide the design of future clinical trials of gene therapy for sickle cell disease.” One important advantage for lentiviral vectors over retroviral vectors is that the former appear less likely to generate cancer-causing mutations; the engineered vector used in this study is self-inactivating.

Two more SCD patients have since been enrolled in the same study.

In a press statement accompanying the March 1 publication, the makers of the gene therapy said these results had prompted them to modify protocols in an ongoing U.S-based study of the same therapy in SCD, in the hope of achieving outcomes similar to those seen in France.

The study was funded by bluebird bio and grants from Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and INSERM. Of the 27 authors, 9 disclosed being stockholders of bluebird, receiving fees, holding patents on technologies used in the study, or being employees. One reported financial relationships with other firms, and 17, including the corresponding author, reported no commercial conflicts of interest.

A teenage boy with sickle cell disease has been successfully treated with a therapy that uses a viral vector to insert functional genes into blood-producing stem cells.

The patient’s positive response to the intervention was first reported in 2015, and his clinical remission was reported in late 2016 at the American Society of Hematology’s annual meeting.

The new report, published online March 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine, contains the first detailed description of the case (2017;376:848-55).

Treatment consisted of LentiGlobin BB305, an engineered lentiviral vector–mediated addition of an antisickling human beta-globin gene (HbAT87Q ) into the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells. The technology was developed by bluebird bio, which partially funded the study and helped design its protocol.

The investigators, led by Marina Cavazzana, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, collected blood-producing stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow. The cells were transduced ex vivo using LentiGlobin BB305.

After the patient underwent 4 days of myeloablation and a 2-day washout period, the transduced stem cells were infused at 5.6x106 CD34+ cells per kilogram. The patient continued receiving red blood cell transfusions until at least 30% healthy hemoglobin with the signature of the introduced gene could be detected.

Neutrophil engraftment occurred at 38 days after transplantation, and platelet engraftment, at 3 months. Red cell transfusions were discontinued at 3 months.

The patient saw vector-bearing healthy cells in the blood increase during the first 3 months after transplantation, the investigators reported, and the cells continue to be produced at stable levels through month 15, which suggests “engraftment of transduced stem cells that were capable of long-term repopulation,” the investigators wrote.

Also at 15 months after transplantation, the patient had 48% HbAT87Q, while 30% healthy hemoglobin is considered sufficient to see clinical improvement in SCD patients.

The patient has not experienced sickle cell disease–related clinical events or hospitalization since transplantation, Dr. Cavazzana and her colleagues reported, noting all his medications, including pain medication, have been stopped.

Most adverse events seen in the study were associated with busulfan, the drug used in myeloablation, and no adverse events were associated with the gene therapy itself.

These results, the investigators concluded, provide proof of concept for lentiviral vectors in delivering this gene therapy for SCD. This approach, they said, “may help to guide the design of future clinical trials of gene therapy for sickle cell disease.” One important advantage for lentiviral vectors over retroviral vectors is that the former appear less likely to generate cancer-causing mutations; the engineered vector used in this study is self-inactivating.

Two more SCD patients have since been enrolled in the same study.

In a press statement accompanying the March 1 publication, the makers of the gene therapy said these results had prompted them to modify protocols in an ongoing U.S-based study of the same therapy in SCD, in the hope of achieving outcomes similar to those seen in France.

The study was funded by bluebird bio and grants from Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and INSERM. Of the 27 authors, 9 disclosed being stockholders of bluebird, receiving fees, holding patents on technologies used in the study, or being employees. One reported financial relationships with other firms, and 17, including the corresponding author, reported no commercial conflicts of interest.

A teenage boy with sickle cell disease has been successfully treated with a therapy that uses a viral vector to insert functional genes into blood-producing stem cells.

The patient’s positive response to the intervention was first reported in 2015, and his clinical remission was reported in late 2016 at the American Society of Hematology’s annual meeting.

The new report, published online March 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine, contains the first detailed description of the case (2017;376:848-55).

Treatment consisted of LentiGlobin BB305, an engineered lentiviral vector–mediated addition of an antisickling human beta-globin gene (HbAT87Q ) into the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells. The technology was developed by bluebird bio, which partially funded the study and helped design its protocol.

The investigators, led by Marina Cavazzana, MD, PhD, of Necker Children’s Hospital, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, collected blood-producing stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow. The cells were transduced ex vivo using LentiGlobin BB305.

After the patient underwent 4 days of myeloablation and a 2-day washout period, the transduced stem cells were infused at 5.6x106 CD34+ cells per kilogram. The patient continued receiving red blood cell transfusions until at least 30% healthy hemoglobin with the signature of the introduced gene could be detected.

Neutrophil engraftment occurred at 38 days after transplantation, and platelet engraftment, at 3 months. Red cell transfusions were discontinued at 3 months.

The patient saw vector-bearing healthy cells in the blood increase during the first 3 months after transplantation, the investigators reported, and the cells continue to be produced at stable levels through month 15, which suggests “engraftment of transduced stem cells that were capable of long-term repopulation,” the investigators wrote.

Also at 15 months after transplantation, the patient had 48% HbAT87Q, while 30% healthy hemoglobin is considered sufficient to see clinical improvement in SCD patients.

The patient has not experienced sickle cell disease–related clinical events or hospitalization since transplantation, Dr. Cavazzana and her colleagues reported, noting all his medications, including pain medication, have been stopped.

Most adverse events seen in the study were associated with busulfan, the drug used in myeloablation, and no adverse events were associated with the gene therapy itself.

These results, the investigators concluded, provide proof of concept for lentiviral vectors in delivering this gene therapy for SCD. This approach, they said, “may help to guide the design of future clinical trials of gene therapy for sickle cell disease.” One important advantage for lentiviral vectors over retroviral vectors is that the former appear less likely to generate cancer-causing mutations; the engineered vector used in this study is self-inactivating.

Two more SCD patients have since been enrolled in the same study.

In a press statement accompanying the March 1 publication, the makers of the gene therapy said these results had prompted them to modify protocols in an ongoing U.S-based study of the same therapy in SCD, in the hope of achieving outcomes similar to those seen in France.

The study was funded by bluebird bio and grants from Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and INSERM. Of the 27 authors, 9 disclosed being stockholders of bluebird, receiving fees, holding patents on technologies used in the study, or being employees. One reported financial relationships with other firms, and 17, including the corresponding author, reported no commercial conflicts of interest.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Using gene therapy in blood-producing stem cells led to clinical remission and durable healthy hemoglobin production in a teenage boy with sickle cell disease.

Major finding: At 15 months post treatment, the patient’s level of therapeutic antisickling beta-globin was 50%, suggesting engraftment and ongoing healthy cell production.

Data source: The first case report from a phase I/II open label trial in France, enrolling three patients with sickle cell disease.

Disclosures: The study was funded by bluebird bio, maker of the technology, and grants from Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and INSERM. One-third of coauthors disclosed financial relationships with the sponsor.

Nemolizumab improves pruritus in atopic dermatitis

Monthly subcutaneous injections of nemolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-31 signaling, significantly improved pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis (AD) in a small, 3-month phase II trial. The results were published online March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Although this trial has limitations, most notably the small number of patients and short duration, it provides evidence supporting the role of interleukin-31 in the pathobiologic mechanism of atopic dermatitis,” said Thomas Ruzicka, MD, of the department of dermatology and allergology, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, and his associates.

Pruritus aggravates atopic dermatitis and has been linked to loss of sleep, depression, aggressiveness, body disfiguration, and suicidal thoughts. Existing treatments, including emollients, topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and oral antihistamines, have limited efficacy and can cause adverse effects when used long term, the investigators noted.

They assessed nemolizumab in a manufacturer-funded multiple-dose trial involving 264 adults in the United States, Europe, and Japan who had refractory moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, inadequately controlled with topical treatments. Study participants were randomly assigned in a double blind fashion to receive 12 weeks of 0.1 mg/kg nemolizumab (53 patients), 0.5 mg/kg nemolizumab (54 patients), 2.0 mg/kg nemolizumab (52 patients), or placebo (53 control subjects) every 4 weeks. Another 52 participants were given 2.0 mg/kg nemolizumab every 8 weeks in an exploratory analysis. All the study participants were permitted to use emollients and localized treatments, and some were permitted by the investigators to use a potent topical glucocorticoid as rescue therapy after week 4.

A total of 216 patients (82%) completed the trial.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage improvement at week 12 in scores on a pruritus visual analogue scale, which patients recorded electronically every day. These scores improved significantly in a dose-dependent manner for active treatment, compared with placebo. Pruritus declined by 43.7% with the 0.1 mg/kg dose (P =.002), 59.8% with the 0.5 mg/kg dose (P less than .001), and 63.1% with the 2.0 mg/kg dose (P less than .001), compared with 20.9% with placebo.

Nemolizumab also bested placebo in several secondary endpoints including scores on a verbal rating of pruritus, the Eczema Area and Severity Index, and the static Investigator’s Global Assessment, the investigators said (N Engl J Med 2017;376:826-35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606490).

The study population was too small to allow the investigators to draw conclusions regarding adverse events, even before a relatively high number of participants dropped out. However, patients who received active treatment had a higher rate of dermatitis exacerbations and peripheral edema than did those who received placebo.

The group given 0.5 mg/kg nemolizumab every month showed the greatest treatment benefit and the best benefit-to-risk profile, Dr. Ruzicka and his associates said.

This trial was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical, which also participated in the study design, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Ruzicka reported receiving research grants and personal fees from Chugai and honoraria from Astellas; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

In addition to the benefits cited by Ruzicka et al., nemolizumab appeared to work quickly, reducing pruritus by nearly 30% within the first week, compared with a slight placebo effect.

Data from larger and longer-term studies, as well as pediatric trials, are needed to fully understand how nemolizumab and other new agents should be incorporated into the management of AD.

It will be important to assess how quickly disease flares occur when these agents are stopped, and whether the concomitant use of other treatments may enhance their effectiveness or induce longer remissions.

Lynda C. Schneider, MD, is in the division of immunology at Boston Children’s Hospital. She disclosed having received grant support from Astellas, personal fees from Anacor Pharmaceuticals, and other support from the National Eczema Association outside the submitted work. Dr. Schneider made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the study (N Engl J Med. 2017 March 2. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1616072).

In addition to the benefits cited by Ruzicka et al., nemolizumab appeared to work quickly, reducing pruritus by nearly 30% within the first week, compared with a slight placebo effect.

Data from larger and longer-term studies, as well as pediatric trials, are needed to fully understand how nemolizumab and other new agents should be incorporated into the management of AD.

It will be important to assess how quickly disease flares occur when these agents are stopped, and whether the concomitant use of other treatments may enhance their effectiveness or induce longer remissions.

Lynda C. Schneider, MD, is in the division of immunology at Boston Children’s Hospital. She disclosed having received grant support from Astellas, personal fees from Anacor Pharmaceuticals, and other support from the National Eczema Association outside the submitted work. Dr. Schneider made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the study (N Engl J Med. 2017 March 2. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1616072).

In addition to the benefits cited by Ruzicka et al., nemolizumab appeared to work quickly, reducing pruritus by nearly 30% within the first week, compared with a slight placebo effect.

Data from larger and longer-term studies, as well as pediatric trials, are needed to fully understand how nemolizumab and other new agents should be incorporated into the management of AD.

It will be important to assess how quickly disease flares occur when these agents are stopped, and whether the concomitant use of other treatments may enhance their effectiveness or induce longer remissions.

Lynda C. Schneider, MD, is in the division of immunology at Boston Children’s Hospital. She disclosed having received grant support from Astellas, personal fees from Anacor Pharmaceuticals, and other support from the National Eczema Association outside the submitted work. Dr. Schneider made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the study (N Engl J Med. 2017 March 2. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1616072).

Monthly subcutaneous injections of nemolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-31 signaling, significantly improved pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis (AD) in a small, 3-month phase II trial. The results were published online March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Although this trial has limitations, most notably the small number of patients and short duration, it provides evidence supporting the role of interleukin-31 in the pathobiologic mechanism of atopic dermatitis,” said Thomas Ruzicka, MD, of the department of dermatology and allergology, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, and his associates.

Pruritus aggravates atopic dermatitis and has been linked to loss of sleep, depression, aggressiveness, body disfiguration, and suicidal thoughts. Existing treatments, including emollients, topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and oral antihistamines, have limited efficacy and can cause adverse effects when used long term, the investigators noted.

They assessed nemolizumab in a manufacturer-funded multiple-dose trial involving 264 adults in the United States, Europe, and Japan who had refractory moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, inadequately controlled with topical treatments. Study participants were randomly assigned in a double blind fashion to receive 12 weeks of 0.1 mg/kg nemolizumab (53 patients), 0.5 mg/kg nemolizumab (54 patients), 2.0 mg/kg nemolizumab (52 patients), or placebo (53 control subjects) every 4 weeks. Another 52 participants were given 2.0 mg/kg nemolizumab every 8 weeks in an exploratory analysis. All the study participants were permitted to use emollients and localized treatments, and some were permitted by the investigators to use a potent topical glucocorticoid as rescue therapy after week 4.

A total of 216 patients (82%) completed the trial.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage improvement at week 12 in scores on a pruritus visual analogue scale, which patients recorded electronically every day. These scores improved significantly in a dose-dependent manner for active treatment, compared with placebo. Pruritus declined by 43.7% with the 0.1 mg/kg dose (P =.002), 59.8% with the 0.5 mg/kg dose (P less than .001), and 63.1% with the 2.0 mg/kg dose (P less than .001), compared with 20.9% with placebo.

Nemolizumab also bested placebo in several secondary endpoints including scores on a verbal rating of pruritus, the Eczema Area and Severity Index, and the static Investigator’s Global Assessment, the investigators said (N Engl J Med 2017;376:826-35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606490).

The study population was too small to allow the investigators to draw conclusions regarding adverse events, even before a relatively high number of participants dropped out. However, patients who received active treatment had a higher rate of dermatitis exacerbations and peripheral edema than did those who received placebo.

The group given 0.5 mg/kg nemolizumab every month showed the greatest treatment benefit and the best benefit-to-risk profile, Dr. Ruzicka and his associates said.

This trial was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical, which also participated in the study design, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Ruzicka reported receiving research grants and personal fees from Chugai and honoraria from Astellas; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Monthly subcutaneous injections of nemolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-31 signaling, significantly improved pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis (AD) in a small, 3-month phase II trial. The results were published online March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Although this trial has limitations, most notably the small number of patients and short duration, it provides evidence supporting the role of interleukin-31 in the pathobiologic mechanism of atopic dermatitis,” said Thomas Ruzicka, MD, of the department of dermatology and allergology, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, and his associates.

Pruritus aggravates atopic dermatitis and has been linked to loss of sleep, depression, aggressiveness, body disfiguration, and suicidal thoughts. Existing treatments, including emollients, topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and oral antihistamines, have limited efficacy and can cause adverse effects when used long term, the investigators noted.

They assessed nemolizumab in a manufacturer-funded multiple-dose trial involving 264 adults in the United States, Europe, and Japan who had refractory moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, inadequately controlled with topical treatments. Study participants were randomly assigned in a double blind fashion to receive 12 weeks of 0.1 mg/kg nemolizumab (53 patients), 0.5 mg/kg nemolizumab (54 patients), 2.0 mg/kg nemolizumab (52 patients), or placebo (53 control subjects) every 4 weeks. Another 52 participants were given 2.0 mg/kg nemolizumab every 8 weeks in an exploratory analysis. All the study participants were permitted to use emollients and localized treatments, and some were permitted by the investigators to use a potent topical glucocorticoid as rescue therapy after week 4.

A total of 216 patients (82%) completed the trial.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage improvement at week 12 in scores on a pruritus visual analogue scale, which patients recorded electronically every day. These scores improved significantly in a dose-dependent manner for active treatment, compared with placebo. Pruritus declined by 43.7% with the 0.1 mg/kg dose (P =.002), 59.8% with the 0.5 mg/kg dose (P less than .001), and 63.1% with the 2.0 mg/kg dose (P less than .001), compared with 20.9% with placebo.

Nemolizumab also bested placebo in several secondary endpoints including scores on a verbal rating of pruritus, the Eczema Area and Severity Index, and the static Investigator’s Global Assessment, the investigators said (N Engl J Med 2017;376:826-35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606490).

The study population was too small to allow the investigators to draw conclusions regarding adverse events, even before a relatively high number of participants dropped out. However, patients who received active treatment had a higher rate of dermatitis exacerbations and peripheral edema than did those who received placebo.

The group given 0.5 mg/kg nemolizumab every month showed the greatest treatment benefit and the best benefit-to-risk profile, Dr. Ruzicka and his associates said.

This trial was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical, which also participated in the study design, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Ruzicka reported receiving research grants and personal fees from Chugai and honoraria from Astellas; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Monthly nemolizumab injections significantly improved pruritus in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

Major finding: Pruritus declined by 43.7% with the 0.1-mg/kg dose, 59.8% with the 0.5-mg/kg dose, and 63.1% with the 2.0-mg/kg dose, compared with 20.9% with placebo.

Data source: A manufacturer-funded international randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase II trial of 216 adults with moderate to severe AD treated for 12 weeks.

Disclosures: This trial was funded by Chugai Pharmaceutical, which also participated in the study design, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Ruzicka reported receiving research grants and personal fees from Chugai and honoraria from Astellas; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Blinatumomab superior to chemotherapy for refractory ALL

Blinatumomab proved superior to standard chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), based on results of an international phase III trial reported online March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was halted early when an interim analysis revealed the clear benefit with blinatumomab, Hagop Kantarjian, MD, chair of the department of leukemia, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his associates wrote.

The manufacturer-sponsored open-label study included 376 adults with Ph-negative B-cell precursor ALL that was either refractory to primary induction therapy or to salvage with intensive combination chemotherapy, first relapse with the first remission lasting less than 12 months, second or greater relapse, or relapse at any time after allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either blinatumomab (267 patients) or the investigator’s choice of one of four protocol-defined regimens of standard chemotherapy (109 patients) and were followed at 101 medical centers in 21 countries for a median of 11 months.

For each 6-week cycle of blinatumomab therapy, patients received treatment for 4 weeks (9 mcg blinatumomab per day during week 1 of induction cycle one and 28 mcg/day thereafter, by continuous infusion) and then no treatment for 2 weeks.

Maintenance treatment with blinatumomab was given as a 4-week continuous infusion every 12 weeks.

At the interim analysis – when 75% of the total number of planned deaths for the final analysis had occurred – the monitoring committee recommended that the trial be stopped early because of the benefit observed with blinatumomab therapy. Median overall survival was significantly longer with blinatumomab (7.7 months) than with chemotherapy (4 months), with a hazard ratio for death of 0.71. The estimated survival at 6 months was 54% with blinatumomab and 39% with chemotherapy.

Remission rates also favored blinatumomab: Rates of complete remission with full hematologic recovery were 34% vs. 16% and rates of complete remission with full, partial, or incomplete hematologic recovery were 44% vs. 25%.

In addition, the median duration of remission was 7.3 months with blinatumomab and 4.6 months with chemotherapy. And 6-month estimates of event-free survival were 31% vs. 12%. These survival and remission benefits were consistent across all subgroups of patients and persisted in several sensitivity analyses, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 2. doi: 10.1056/nejmOA1609783).

A total of 24% of the patients in the blinatumomab group and 24% of the patients in the chemotherapy group underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with comparable outcomes and death rates.

Serious adverse events occurred in 62% of patients receiving blinatumomab and in 45% of those receiving chemotherapy, including fatal adverse events in 19% and 17%, respectively. The fatal events were considered to be related to treatment in 3% of the blinatumomab group and in 7% of the chemotherapy group. Rates of treatment discontinuation from an adverse event were 12% and 8%, respectively.

Patient-reported health status and quality of life improved with blinatumomab but worsened with chemotherapy.

“Given the previous exposure of these patients to myelosuppressive and immunosuppressive treatments, the activity of an immune-based therapy such as blinatumomab, which depends on functioning T cells for its activity, provides encouragement that responses may be further enhanced and made durable with additional immune activation strategies,” Dr. Kantarjian and his associates noted.

Dr. Kantarjian reported receiving research support from Amgen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and ARIAD; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Blinatumomab proved superior to standard chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), based on results of an international phase III trial reported online March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was halted early when an interim analysis revealed the clear benefit with blinatumomab, Hagop Kantarjian, MD, chair of the department of leukemia, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his associates wrote.

The manufacturer-sponsored open-label study included 376 adults with Ph-negative B-cell precursor ALL that was either refractory to primary induction therapy or to salvage with intensive combination chemotherapy, first relapse with the first remission lasting less than 12 months, second or greater relapse, or relapse at any time after allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either blinatumomab (267 patients) or the investigator’s choice of one of four protocol-defined regimens of standard chemotherapy (109 patients) and were followed at 101 medical centers in 21 countries for a median of 11 months.

For each 6-week cycle of blinatumomab therapy, patients received treatment for 4 weeks (9 mcg blinatumomab per day during week 1 of induction cycle one and 28 mcg/day thereafter, by continuous infusion) and then no treatment for 2 weeks.

Maintenance treatment with blinatumomab was given as a 4-week continuous infusion every 12 weeks.

At the interim analysis – when 75% of the total number of planned deaths for the final analysis had occurred – the monitoring committee recommended that the trial be stopped early because of the benefit observed with blinatumomab therapy. Median overall survival was significantly longer with blinatumomab (7.7 months) than with chemotherapy (4 months), with a hazard ratio for death of 0.71. The estimated survival at 6 months was 54% with blinatumomab and 39% with chemotherapy.

Remission rates also favored blinatumomab: Rates of complete remission with full hematologic recovery were 34% vs. 16% and rates of complete remission with full, partial, or incomplete hematologic recovery were 44% vs. 25%.

In addition, the median duration of remission was 7.3 months with blinatumomab and 4.6 months with chemotherapy. And 6-month estimates of event-free survival were 31% vs. 12%. These survival and remission benefits were consistent across all subgroups of patients and persisted in several sensitivity analyses, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 2. doi: 10.1056/nejmOA1609783).

A total of 24% of the patients in the blinatumomab group and 24% of the patients in the chemotherapy group underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with comparable outcomes and death rates.

Serious adverse events occurred in 62% of patients receiving blinatumomab and in 45% of those receiving chemotherapy, including fatal adverse events in 19% and 17%, respectively. The fatal events were considered to be related to treatment in 3% of the blinatumomab group and in 7% of the chemotherapy group. Rates of treatment discontinuation from an adverse event were 12% and 8%, respectively.

Patient-reported health status and quality of life improved with blinatumomab but worsened with chemotherapy.

“Given the previous exposure of these patients to myelosuppressive and immunosuppressive treatments, the activity of an immune-based therapy such as blinatumomab, which depends on functioning T cells for its activity, provides encouragement that responses may be further enhanced and made durable with additional immune activation strategies,” Dr. Kantarjian and his associates noted.

Dr. Kantarjian reported receiving research support from Amgen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and ARIAD; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Blinatumomab proved superior to standard chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), based on results of an international phase III trial reported online March 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was halted early when an interim analysis revealed the clear benefit with blinatumomab, Hagop Kantarjian, MD, chair of the department of leukemia, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his associates wrote.

The manufacturer-sponsored open-label study included 376 adults with Ph-negative B-cell precursor ALL that was either refractory to primary induction therapy or to salvage with intensive combination chemotherapy, first relapse with the first remission lasting less than 12 months, second or greater relapse, or relapse at any time after allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either blinatumomab (267 patients) or the investigator’s choice of one of four protocol-defined regimens of standard chemotherapy (109 patients) and were followed at 101 medical centers in 21 countries for a median of 11 months.

For each 6-week cycle of blinatumomab therapy, patients received treatment for 4 weeks (9 mcg blinatumomab per day during week 1 of induction cycle one and 28 mcg/day thereafter, by continuous infusion) and then no treatment for 2 weeks.

Maintenance treatment with blinatumomab was given as a 4-week continuous infusion every 12 weeks.

At the interim analysis – when 75% of the total number of planned deaths for the final analysis had occurred – the monitoring committee recommended that the trial be stopped early because of the benefit observed with blinatumomab therapy. Median overall survival was significantly longer with blinatumomab (7.7 months) than with chemotherapy (4 months), with a hazard ratio for death of 0.71. The estimated survival at 6 months was 54% with blinatumomab and 39% with chemotherapy.

Remission rates also favored blinatumomab: Rates of complete remission with full hematologic recovery were 34% vs. 16% and rates of complete remission with full, partial, or incomplete hematologic recovery were 44% vs. 25%.

In addition, the median duration of remission was 7.3 months with blinatumomab and 4.6 months with chemotherapy. And 6-month estimates of event-free survival were 31% vs. 12%. These survival and remission benefits were consistent across all subgroups of patients and persisted in several sensitivity analyses, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 2. doi: 10.1056/nejmOA1609783).

A total of 24% of the patients in the blinatumomab group and 24% of the patients in the chemotherapy group underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation, with comparable outcomes and death rates.

Serious adverse events occurred in 62% of patients receiving blinatumomab and in 45% of those receiving chemotherapy, including fatal adverse events in 19% and 17%, respectively. The fatal events were considered to be related to treatment in 3% of the blinatumomab group and in 7% of the chemotherapy group. Rates of treatment discontinuation from an adverse event were 12% and 8%, respectively.

Patient-reported health status and quality of life improved with blinatumomab but worsened with chemotherapy.

“Given the previous exposure of these patients to myelosuppressive and immunosuppressive treatments, the activity of an immune-based therapy such as blinatumomab, which depends on functioning T cells for its activity, provides encouragement that responses may be further enhanced and made durable with additional immune activation strategies,” Dr. Kantarjian and his associates noted.

Dr. Kantarjian reported receiving research support from Amgen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and ARIAD; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Blinatumomab proved superior to standard chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory ALL in a phase III trial.

Major finding: Median overall survival with blinatumomab (7.7 months) was significantly longer than with chemotherapy (4.0 months), and rates of complete remission with full hematologic recovery were 34% vs 16%, respectively.

Data source: A manufacturer-sponsored international randomized open-label phase-3 trial involving 376 adults followed for 11 months.

Disclosures: This trial was funded by Amgen, which also participated in the study design, data analysis, and report writing. Dr. Kantarjian reported receiving research support from Amgen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and ARIAD; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Tissue, peripheral eosinophilia correlate with UC activity, severity

Evidence linking tissue and peripheral eosinophilia with ulcerative colitis (UC) activity and severity was found in a retrospective chart review of pediatric UC cases.

Further, the review found both types of eosinophilia linked with the need for step-up therapy or corticosteroid therapy in the first year following UC diagnosis.

Sara Morgenstern, MD, of Tel Aviv University, and her coauthors reviewed all pediatric UC cases diagnosed between ages 0 and 17 years at the Schneider Children’s Hospital of Israel, Petah Tikva, between 1990 and 2015. Of 96 children diagnosed with UC by colonoscopy and followed for a median of 13 years, 31 had severe eosinophilia at the time of diagnosis, compared with 40 who had mild eosinophilia, and 25 who had a normal tissue eosinophil count. After remission, 77 had a normal eosinophilia and 19 had mild eosinophilia.

“At diagnosis, at follow-up with histologic activity and at follow-up with histologic remission, peripheral eosinophilia was demonstrated in 27%, 30% and 8%, respectively,” Dr. Morgenstern and her coauthors wrote. In the control group, 5% had peripheral eosinophilia, a significant difference (Dig Liver Dis. 2017 Feb;49[2]:170-4).

Disease activity and severity, as measured using the Pediatric UC Activity Index score, correlated significantly with tissue and blood eosinophil counts at diagnosis (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively). Disease activity and severity also correlated significantly with corticosteroid therapy, immunomodulatory therapy, and biologic therapy during the first year following diagnosis (P = .018, .04, and .05 for tissue eosinophilia; P = .013, .01, and .04 for peripheral eosinophilia, respectively).

“These findings may suggest that both tissue and peripheral eosinophilia may serve as a diagnostic marker for disease activity, severity, and short-term outcomes also in the pediatric population,” they wrote.

Dr. Morgenstern and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Evidence linking tissue and peripheral eosinophilia with ulcerative colitis (UC) activity and severity was found in a retrospective chart review of pediatric UC cases.

Further, the review found both types of eosinophilia linked with the need for step-up therapy or corticosteroid therapy in the first year following UC diagnosis.