User login

Hospitalization Risk With Benzodiazepine and Opioid Use in Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (FULL)

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that may develop in response to a traumatic event, such as that experienced by a soldier during active combat duty. In 2009, more than 495,000 veterans within the VA health care system were treated for PTSD—nearly triple the number a decade earlier.1 Core symptoms of PTSD include alterations in arousal and reactivity, avoidant behaviors, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and intrusive thoughts and nightmares. All of the symptoms can be debilitating. First-line pharmacotherapy options that target these core symptoms include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).2

The anxiolytic and sedative effects of benzodiazepines may provide quick relief from many of the secondary symptoms of PTSD, including sleep disturbances, irritability, and panic attacks. However, benzodiazepines potentially interfere with the extinction of conditioned fear—a goal integral to certain types of psychotherapy, such as exposure therapy.3,4 In addition, the systematic review and meta-analysis by Guina and colleagues revealed that benzodiazepines are ineffective in the treatment of PTSD.5 The majority of the evaluated studies that used PTSD-specific measures (eg, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [CAPS]) found increased PTSD severity and worse prognosis with use of these medications.5 In 2010, the VA and the DoD released a joint guideline for PTSD management.2 According to the guideline, benzodiazepines cause harm when used in PTSD and are relatively contraindicated in combat veterans because of the higher incidence of comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) in these veterans relative to the general population.2,6

Opioid use also has been linked to poor functional and clinical outcomes in veterans with PTSD. Among patients being treated for opioid use disorder, those with PTSD were less likely to endorse employment as a main source of income and had a higher incidence of recent attempted suicide.7 In a large retrospective cohort study, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom veterans with PTSD who were prescribed opioids were more likely to present to the emergency department (ED) and to be hospitalized for overdoses and injuries.8

Despite the risks of benzodiazepine and opioid use in this patient population, these medications are still often prescribed to veterans with PTSD for symptomatic relief. In fiscal year 2009, across the VHA system 37% of veterans diagnosed with PTSD were prescribed a benzodiazepine, 69% of the time by a mental health provider.9 Among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, those with PTSD were significantly more likely to be prescribed an opioid for diagnosed pain—relative to those with a mental health disorder other than PTSD and those without a mental health disorder.8 Thus, there seems to be a disconnect between guideline recommendations and current practice.

The authors conducted a study to assess the potential risk of hospitalization for veterans with PTSD prescribed first-line pharmacotherapy and those also prescribed concurrent benzodiazepine and/or opioid therapy since the release of the PTSD guideline in 2010.2

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, conducted at the Southern Arizona VA Health Care System (SAVAHCS), the authors analyzed electronic medical record data from November 1, 2009 to August 1, 2015. Study inclusion criteria were veteran, aged 18 to 89 years, diagnosis of PTSD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 309.81), and SSRI or SNRI newly prescribed between November 1, 2010 and August 1, 2013.

Any veteran prescribed at least one 30-day or longer supply of any benzodiazepine or opioid within 1 year before the SSRI/SNRI initial prescription date was excluded from the study. Also excluded was any patient treated for PTSD at a facility outside SAVAHCS or whose 2-year evaluation period extended past August 1, 2015.

Study Groups

An outpatient prescription was determined to be the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription for a patient who received less than a 30-day cumulative supply of any SSRI or SNRI within 1 year before that prescription date. Citalopram, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, levomilnacipran, milnacipran, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, vilazodone, and vortioxetine were the prespecified SSRI/SNRIs included in the study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any benzodiazepine (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy. Alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, and triazolam were the prespecified benzodiazepines included in the study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any opioid (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy. Codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxymorphone, pentazocine, propoxyphene, and tramadol were the prespecified opioids included in this study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any benzodiazepine and any opioid (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy.

The index date was defined as the first date of prescription overlap. If there was no benzodiazepine or opioid prescription within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date, the patient was categorized as being on SSRI/SNRI monotherapy, and the index date was the date of the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription. For each patient, hospitalization data from the 2-year period after the index date were evaluated.

Outcomes and Data Collection

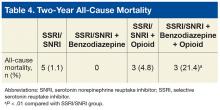

For evaluation of the primary outcome (2-year overall hospitalization risk), the number of unique mental health and medical/surgical hospitalizations was identified by the number of discharge summaries documented in the patient chart during the evaluation period. Time to first hospitalization was recorded for the survival data analysis. Secondary outcomes were mental health hospitalization risk, medical/surgical hospitalization risk, and all-cause mortality within 2 years.

Demographic data that were collected included age, sex, comorbid mental health disorders, comorbid SUDs, and concomitant use of psychotropic medications at index date (baseline). Select comorbid mental health disorders (anxiety, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder) and substance use disorders (alcohol, opioid, illicit drug) also were identified. Data on insomnia and pain comorbidities (headaches or migraines; neuropathy; head, neck, back, arthritis, or joint pain) were collected, as these comorbidities could be indications for prescribing benzodiazepines and opioids. Concomitant baseline use of classes of psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, non-SSRI/SNRI antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, nonbenzodiazepine sedatives/hypnotics) also were documented. Last, hospitalizations within 6 months before the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were noted.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze all baseline demographic data. Continuous measures were evaluated with 1-way analyses of variance and post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons, and categorical measures with contingency tables and χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests. When the overall χ2 test was significant across all 4 study groups, post hoc comparisons were performed between the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group and each other group with Bonferroni adjusted for 3 comparisons.

Unadjusted and adjusted Weibull proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate hospitalization risk within 2 years after the index date for the different study groups with the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group as the referent. Robust standard errors were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Weibull model (and not the Cox model) was used because it does not assume hazard remains constant over time, which is appropriate in this instance, as the risk of an adverse event (AE) may be higher when first starting a medication or combination of medications relative to when doses are stabilized. Models were adjusted for age, sex, baseline mental health disorders, and baseline psychotropic medications. As earlier hospitalizations showed evidence of effect modification when this covariate was tested, hazard analyses were limited to patients not previously hospitalized.

The effect size of differences in hospitalization risk meeting statistical significance was assessed by estimating the number needed to harm (NNH) and 95% CIs (not shown) to observe 1 additional hospitalization in each medication group relative to the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group over a 90-day period. A 95% CI for NNH that did not include 0 indicated the NNH was significant at the .05 level.10 All-cause mortality was evaluated with the Fisher exact test with post hoc Bonferroni-corrected comparisons as appropriate.

Results

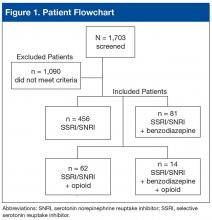

Of 1,703 patients screened, 613 met all study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

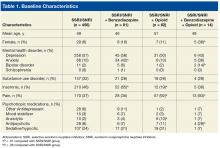

Baseline characteristics revealed no significant differences between groups in age or comorbid depression, schizophrenia, or SUDs (Table 1).

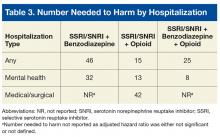

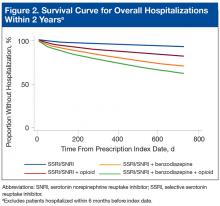

With the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group as the referent, all concurrent therapy groups were at significantly increased risk for overall hospitalization within 2 years after the index date (Tables 2 & 3, Figure 2).

Risk for mental health hospitalization was significantly increased in all concurrent therapy groups relative to the referent group.

Although the risk for medical/surgical hospitalization was not significantly increased in the SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy group (AHR, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.67-5.6), a significant difference was found in the SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy group (AHR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.6-12.0; NNH, 42).

Discussion

In 2013, Hawkins and colleagues evaluated hospitalization risk in veterans treated for PTSD within the Northwest VISN 20 between 2004 and 2010.11 Compared with patients treated with only an SSRI or SNRI, those treated with 1 of those medications and a benzodiazepine were at significantly higher risk for overall hospitalization (AHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.38-2.32; P < .001) and mental health hospitalization (AHR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.37-2.53; P < .001). Furthermore, those prescribed a benzodiazepine and an opioid along with an SSRI or SNRI were at higher risk for overall hospitalization (AHR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.22-4.00; P < .001), mental health hospitalization (AHR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.35-2.98; P < .01), medical/surgical hospitalization (AHR, 4.86; 95% CI, 3.30-7.14; P < .001), and ED visits (AHR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.53-2.65; P < .001).

Findings from the present study, which covered a period after the newest PTSD guideline was released,support findings reported by Hawkins and colleagues in their retrospective cohort study covering an earlier period.2,11 In the present study, compared with the monotherapy group, the SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy group and the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group were at higher risk for both overall hospitalization and mental health hospitalization within 2 years. However, in a subset of PTSD patients prescribed opioids along with first-line pharmacotherapy, this study found that overall, mental health, and medical/surgical hospitalizations were significantly increased as well. Furthermore, this study found 2-year mortality was significantly higher for the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group than for the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group.

Adjusted hazard ratios were higher in the present study than those in the study by Hawkins and colleagues,but CIs were wider as well.11 These differences may be attributable to the relatively smaller sample size of the present study and may explain why the HR was higher for the SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy group than for the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group.

Nevertheless, these results support the growing body of evidence establishing the many risks for AEs when benzodiazepines and opioids are prescribed in the setting of PTSD. Unfortunately, it seems that, against clear guideline recommendations and literature findings, these medications still are being prescribed to this vulnerable, high-risk population.

In the last few months of 2013, the VA health care system launched 2 important medication safety initiatives. The Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) was established as a quality improvement initiative for evidence-based provision of psychotropic medications. One PDSI metric in particular focused on reducing the proportion of veterans with PTSD being treated with benzodiazepines. The Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) came as a response to a dramatic increase in the number of fatal overdoses related to prescription opioids—an increase linked to an unprecedented jump in opioid use for nonmalignant pain. As the present study’s inclusion cutoff date of August 1, 2013, preceded the debut of both PDSI and OSI, the benzodiazepine and opioid prescription rates reported here might be higher than those currently being found under the 2 initiatives.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that might affect the interpretation or generalizability of findings. Requiring at least a 30-day supply for prescription eligibility was an attempt to focus on chronic use of medications rather than on, for example, onetime supplies of opioids for dental procedures. However, prescription fill history was not assessed. Therefore, patients could have been included in certain study groups even if their SSRI, SNRI, benzodiazepine, or opioid prescription was not refilled. Furthermore, only VA medical records were used; non-VA prescriptions were not captured.

In addition, this study was limited to patients who at bare minimum were prescribed an SSRI or an SNRI. Some patients may have been prescribed a benzodiazepine and/or an opioid but were not on appropriate first-line pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These patients were excluded from the study, and their relative hospitalization risk went unexplored. Therefore, the magnitude of the issue at hand might have been underestimated.

Although psychotherapy is a first-line treatment option for PTSD, the study did not assess the potential impact of psychotherapy on outcomes or the groups’ relative proportions of patients undergoing psychotherapy. It is unknown whether the groups were equivalent at baseline in regards to psychotherapy participation rates.

This study did not characterize the specific reasons for hospitalization beyond whether it was for a mental health or a medical/surgical issue; thus, no distinction was made between hospitalizations for an elective procedure and hospitalizations for a drug overdose or an injury. Investigators could characterize admission diagnoses to better assess whether hospitalizations are truly associated with study medications or whether patients are being hospitalized for unrelated reasons. In addition, they could elucidate the true nature of hospitalization risk associated with SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid use by comparing admission diagnoses made before and after initiation of these pharmacologic therapies.

This study also could not assess outcomes for patients who presented to the ED but were not admitted. If the hospital’s floor and ED beds were at full capacity, some patients might have been transferred to an outside facility. However, this scenario is not common at SAVAHCS, where the study was conducted.

Although some comorbid conditions were noted, the study did not evaluate whether its patients had a compelling indication for benzodiazepines in particular. Opioid use is very limited to the treatment of pain, and the majority of the patients on opioid therapy in this study had a diagnosed pain syndrome.

Because of the study’s sample size and power limitations, patients were eligible to be included in a concurrent therapy group if a benzodiazepine, an opioid, or both were added no later than 1 year after SSRI/SNRI initiation. This gap of up to 1 year might have introduced some variability in exposure to risk from earlier prescribed medications. However, sensitivity analyses were performed with multiple constructed Weibull models of time to hospitalization based on subsets with varying overlapping medication gaps. Analyses revealed relatively stable HRs, suggesting that potential bias did not occur.

Future Directions

Investigators could explore the higher all-cause mortality rates in the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group, as this study did not assess cause of death in these patients. Whether any patients died of reasons directly attributable to benzodiazepines or opioids is unknown.

That SSRIs and SNRIs are the only established first-line pharmacologic treatment options for PTSD symptoms partly accounts for the widespread use of benzodiazepines in this population. For that reason, beyond characterizing the many risks associated with using benzodiazepines to manage these symptoms, there is a huge need to research the viability of other pharmacologic agents in treating PTSD. This is especially important given the slower onset to efficacy of the SSRIs and SNRIs; per estimates, only up to 60% of patients respond to SSRIs, and 20% to 30% achieve full remission of PTSD.12 Furthermore, these rates likely are even lower for combat veterans than those for the general population. Several trials discussed in a 2009 guideline review of the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and PTSD have called into question the efficacy of SSRIs for combat-related PTSD.13 In these randomized, controlled trials, change in PTSD symptom severity as measured with CAPS was not significantly reduced with SSRIs compared with placebo.

A systematic review revealed that, of the nonantidepressants used as adjuncts in treating patients who do not achieve remission with SSRIs, the atypical antipsychotic risperidone may have the strongest supporting evidence.12 However, the present study found high rates of antipsychotic use in the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group, which also had the highest all-cause mortality rate. The safety of risperidone as an alternative treatment needs further evaluation.

Some prospective studies have suggested that the α1 blockers doxazosin and prazosin, the latter of which is commonly used for PTSD nightmares, also may improve PTSD symptoms as assessed by CAPS.14,15 Although these results are promising, the trials to date have been conducted with relatively small sample sizes.

With more veterans being treated for PTSD within the VA health care system, the central treatment goal remains: Adequately address the symptoms of PTSD while minimizing the harm caused by medications. Prescribers should limit benzodiazepine and opioid use in this population and consider safer nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment options when possible.

Conclusion

Combat veterans with PTSD who are prescribed benzodiazepines and/or opioids in addition to first-line pharmacotherapy are at significantly increased risk for overall and mental health hospitalization.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Jenkyn AB, Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ. Gender differences in prescribing among veterans diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(suppl 2):S542-S548.

2. Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/PTSD-full-2010c .pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed July 12, 2015.

3. Marks IM, Swinson RP, Baso˘glu M, et al. Alprazolam and exposure alone and combined in panic disorder with agoraphobia. A controlled study in London and Toronto. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:776-787.

4. Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Acute and delayed effects of alprazolam on flight phobics during exposure. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(9):831-841.

5. Guina J, Rossetter SR, DeRhodes BJ, Nahhas RW, Welton RS. Benzodiazepines for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(4):281-303.

6. Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(3):456-465.

7. Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Shanahan M. The costs and outcomes of treatment for opioid dependence associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(8):940-945.

8. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

9. Abrams TE, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, Friedman MJ. Aligning clinical practice to PTSD treatment guidelines: medication prescribing by provider type. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):142-148.

10. Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1492-1495.

11. Hawkins EJ, Malte CA, Grossbard J, Saxon AJ, Imel ZE, Kivlahan DR. Comparative safety of benzodiazepines and opioids among Veterans Affairs patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):354-362.

12. Berger W, Mendlowicz MV, Marques-Portella C, et al. Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):169-180.

13. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, Ursano RJ. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):204-213.

14. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

15. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that may develop in response to a traumatic event, such as that experienced by a soldier during active combat duty. In 2009, more than 495,000 veterans within the VA health care system were treated for PTSD—nearly triple the number a decade earlier.1 Core symptoms of PTSD include alterations in arousal and reactivity, avoidant behaviors, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and intrusive thoughts and nightmares. All of the symptoms can be debilitating. First-line pharmacotherapy options that target these core symptoms include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).2

The anxiolytic and sedative effects of benzodiazepines may provide quick relief from many of the secondary symptoms of PTSD, including sleep disturbances, irritability, and panic attacks. However, benzodiazepines potentially interfere with the extinction of conditioned fear—a goal integral to certain types of psychotherapy, such as exposure therapy.3,4 In addition, the systematic review and meta-analysis by Guina and colleagues revealed that benzodiazepines are ineffective in the treatment of PTSD.5 The majority of the evaluated studies that used PTSD-specific measures (eg, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [CAPS]) found increased PTSD severity and worse prognosis with use of these medications.5 In 2010, the VA and the DoD released a joint guideline for PTSD management.2 According to the guideline, benzodiazepines cause harm when used in PTSD and are relatively contraindicated in combat veterans because of the higher incidence of comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) in these veterans relative to the general population.2,6

Opioid use also has been linked to poor functional and clinical outcomes in veterans with PTSD. Among patients being treated for opioid use disorder, those with PTSD were less likely to endorse employment as a main source of income and had a higher incidence of recent attempted suicide.7 In a large retrospective cohort study, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom veterans with PTSD who were prescribed opioids were more likely to present to the emergency department (ED) and to be hospitalized for overdoses and injuries.8

Despite the risks of benzodiazepine and opioid use in this patient population, these medications are still often prescribed to veterans with PTSD for symptomatic relief. In fiscal year 2009, across the VHA system 37% of veterans diagnosed with PTSD were prescribed a benzodiazepine, 69% of the time by a mental health provider.9 Among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, those with PTSD were significantly more likely to be prescribed an opioid for diagnosed pain—relative to those with a mental health disorder other than PTSD and those without a mental health disorder.8 Thus, there seems to be a disconnect between guideline recommendations and current practice.

The authors conducted a study to assess the potential risk of hospitalization for veterans with PTSD prescribed first-line pharmacotherapy and those also prescribed concurrent benzodiazepine and/or opioid therapy since the release of the PTSD guideline in 2010.2

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, conducted at the Southern Arizona VA Health Care System (SAVAHCS), the authors analyzed electronic medical record data from November 1, 2009 to August 1, 2015. Study inclusion criteria were veteran, aged 18 to 89 years, diagnosis of PTSD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 309.81), and SSRI or SNRI newly prescribed between November 1, 2010 and August 1, 2013.

Any veteran prescribed at least one 30-day or longer supply of any benzodiazepine or opioid within 1 year before the SSRI/SNRI initial prescription date was excluded from the study. Also excluded was any patient treated for PTSD at a facility outside SAVAHCS or whose 2-year evaluation period extended past August 1, 2015.

Study Groups

An outpatient prescription was determined to be the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription for a patient who received less than a 30-day cumulative supply of any SSRI or SNRI within 1 year before that prescription date. Citalopram, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, levomilnacipran, milnacipran, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, vilazodone, and vortioxetine were the prespecified SSRI/SNRIs included in the study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any benzodiazepine (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy. Alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, and triazolam were the prespecified benzodiazepines included in the study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any opioid (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy. Codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxymorphone, pentazocine, propoxyphene, and tramadol were the prespecified opioids included in this study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any benzodiazepine and any opioid (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy.

The index date was defined as the first date of prescription overlap. If there was no benzodiazepine or opioid prescription within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date, the patient was categorized as being on SSRI/SNRI monotherapy, and the index date was the date of the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription. For each patient, hospitalization data from the 2-year period after the index date were evaluated.

Outcomes and Data Collection

For evaluation of the primary outcome (2-year overall hospitalization risk), the number of unique mental health and medical/surgical hospitalizations was identified by the number of discharge summaries documented in the patient chart during the evaluation period. Time to first hospitalization was recorded for the survival data analysis. Secondary outcomes were mental health hospitalization risk, medical/surgical hospitalization risk, and all-cause mortality within 2 years.

Demographic data that were collected included age, sex, comorbid mental health disorders, comorbid SUDs, and concomitant use of psychotropic medications at index date (baseline). Select comorbid mental health disorders (anxiety, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder) and substance use disorders (alcohol, opioid, illicit drug) also were identified. Data on insomnia and pain comorbidities (headaches or migraines; neuropathy; head, neck, back, arthritis, or joint pain) were collected, as these comorbidities could be indications for prescribing benzodiazepines and opioids. Concomitant baseline use of classes of psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, non-SSRI/SNRI antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, nonbenzodiazepine sedatives/hypnotics) also were documented. Last, hospitalizations within 6 months before the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were noted.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze all baseline demographic data. Continuous measures were evaluated with 1-way analyses of variance and post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons, and categorical measures with contingency tables and χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests. When the overall χ2 test was significant across all 4 study groups, post hoc comparisons were performed between the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group and each other group with Bonferroni adjusted for 3 comparisons.

Unadjusted and adjusted Weibull proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate hospitalization risk within 2 years after the index date for the different study groups with the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group as the referent. Robust standard errors were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Weibull model (and not the Cox model) was used because it does not assume hazard remains constant over time, which is appropriate in this instance, as the risk of an adverse event (AE) may be higher when first starting a medication or combination of medications relative to when doses are stabilized. Models were adjusted for age, sex, baseline mental health disorders, and baseline psychotropic medications. As earlier hospitalizations showed evidence of effect modification when this covariate was tested, hazard analyses were limited to patients not previously hospitalized.

The effect size of differences in hospitalization risk meeting statistical significance was assessed by estimating the number needed to harm (NNH) and 95% CIs (not shown) to observe 1 additional hospitalization in each medication group relative to the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group over a 90-day period. A 95% CI for NNH that did not include 0 indicated the NNH was significant at the .05 level.10 All-cause mortality was evaluated with the Fisher exact test with post hoc Bonferroni-corrected comparisons as appropriate.

Results

Of 1,703 patients screened, 613 met all study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics revealed no significant differences between groups in age or comorbid depression, schizophrenia, or SUDs (Table 1).

With the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group as the referent, all concurrent therapy groups were at significantly increased risk for overall hospitalization within 2 years after the index date (Tables 2 & 3, Figure 2).

Risk for mental health hospitalization was significantly increased in all concurrent therapy groups relative to the referent group.

Although the risk for medical/surgical hospitalization was not significantly increased in the SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy group (AHR, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.67-5.6), a significant difference was found in the SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy group (AHR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.6-12.0; NNH, 42).

Discussion

In 2013, Hawkins and colleagues evaluated hospitalization risk in veterans treated for PTSD within the Northwest VISN 20 between 2004 and 2010.11 Compared with patients treated with only an SSRI or SNRI, those treated with 1 of those medications and a benzodiazepine were at significantly higher risk for overall hospitalization (AHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.38-2.32; P < .001) and mental health hospitalization (AHR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.37-2.53; P < .001). Furthermore, those prescribed a benzodiazepine and an opioid along with an SSRI or SNRI were at higher risk for overall hospitalization (AHR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.22-4.00; P < .001), mental health hospitalization (AHR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.35-2.98; P < .01), medical/surgical hospitalization (AHR, 4.86; 95% CI, 3.30-7.14; P < .001), and ED visits (AHR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.53-2.65; P < .001).

Findings from the present study, which covered a period after the newest PTSD guideline was released,support findings reported by Hawkins and colleagues in their retrospective cohort study covering an earlier period.2,11 In the present study, compared with the monotherapy group, the SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy group and the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group were at higher risk for both overall hospitalization and mental health hospitalization within 2 years. However, in a subset of PTSD patients prescribed opioids along with first-line pharmacotherapy, this study found that overall, mental health, and medical/surgical hospitalizations were significantly increased as well. Furthermore, this study found 2-year mortality was significantly higher for the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group than for the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group.

Adjusted hazard ratios were higher in the present study than those in the study by Hawkins and colleagues,but CIs were wider as well.11 These differences may be attributable to the relatively smaller sample size of the present study and may explain why the HR was higher for the SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy group than for the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group.

Nevertheless, these results support the growing body of evidence establishing the many risks for AEs when benzodiazepines and opioids are prescribed in the setting of PTSD. Unfortunately, it seems that, against clear guideline recommendations and literature findings, these medications still are being prescribed to this vulnerable, high-risk population.

In the last few months of 2013, the VA health care system launched 2 important medication safety initiatives. The Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) was established as a quality improvement initiative for evidence-based provision of psychotropic medications. One PDSI metric in particular focused on reducing the proportion of veterans with PTSD being treated with benzodiazepines. The Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) came as a response to a dramatic increase in the number of fatal overdoses related to prescription opioids—an increase linked to an unprecedented jump in opioid use for nonmalignant pain. As the present study’s inclusion cutoff date of August 1, 2013, preceded the debut of both PDSI and OSI, the benzodiazepine and opioid prescription rates reported here might be higher than those currently being found under the 2 initiatives.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that might affect the interpretation or generalizability of findings. Requiring at least a 30-day supply for prescription eligibility was an attempt to focus on chronic use of medications rather than on, for example, onetime supplies of opioids for dental procedures. However, prescription fill history was not assessed. Therefore, patients could have been included in certain study groups even if their SSRI, SNRI, benzodiazepine, or opioid prescription was not refilled. Furthermore, only VA medical records were used; non-VA prescriptions were not captured.

In addition, this study was limited to patients who at bare minimum were prescribed an SSRI or an SNRI. Some patients may have been prescribed a benzodiazepine and/or an opioid but were not on appropriate first-line pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These patients were excluded from the study, and their relative hospitalization risk went unexplored. Therefore, the magnitude of the issue at hand might have been underestimated.

Although psychotherapy is a first-line treatment option for PTSD, the study did not assess the potential impact of psychotherapy on outcomes or the groups’ relative proportions of patients undergoing psychotherapy. It is unknown whether the groups were equivalent at baseline in regards to psychotherapy participation rates.

This study did not characterize the specific reasons for hospitalization beyond whether it was for a mental health or a medical/surgical issue; thus, no distinction was made between hospitalizations for an elective procedure and hospitalizations for a drug overdose or an injury. Investigators could characterize admission diagnoses to better assess whether hospitalizations are truly associated with study medications or whether patients are being hospitalized for unrelated reasons. In addition, they could elucidate the true nature of hospitalization risk associated with SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid use by comparing admission diagnoses made before and after initiation of these pharmacologic therapies.

This study also could not assess outcomes for patients who presented to the ED but were not admitted. If the hospital’s floor and ED beds were at full capacity, some patients might have been transferred to an outside facility. However, this scenario is not common at SAVAHCS, where the study was conducted.

Although some comorbid conditions were noted, the study did not evaluate whether its patients had a compelling indication for benzodiazepines in particular. Opioid use is very limited to the treatment of pain, and the majority of the patients on opioid therapy in this study had a diagnosed pain syndrome.

Because of the study’s sample size and power limitations, patients were eligible to be included in a concurrent therapy group if a benzodiazepine, an opioid, or both were added no later than 1 year after SSRI/SNRI initiation. This gap of up to 1 year might have introduced some variability in exposure to risk from earlier prescribed medications. However, sensitivity analyses were performed with multiple constructed Weibull models of time to hospitalization based on subsets with varying overlapping medication gaps. Analyses revealed relatively stable HRs, suggesting that potential bias did not occur.

Future Directions

Investigators could explore the higher all-cause mortality rates in the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group, as this study did not assess cause of death in these patients. Whether any patients died of reasons directly attributable to benzodiazepines or opioids is unknown.

That SSRIs and SNRIs are the only established first-line pharmacologic treatment options for PTSD symptoms partly accounts for the widespread use of benzodiazepines in this population. For that reason, beyond characterizing the many risks associated with using benzodiazepines to manage these symptoms, there is a huge need to research the viability of other pharmacologic agents in treating PTSD. This is especially important given the slower onset to efficacy of the SSRIs and SNRIs; per estimates, only up to 60% of patients respond to SSRIs, and 20% to 30% achieve full remission of PTSD.12 Furthermore, these rates likely are even lower for combat veterans than those for the general population. Several trials discussed in a 2009 guideline review of the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and PTSD have called into question the efficacy of SSRIs for combat-related PTSD.13 In these randomized, controlled trials, change in PTSD symptom severity as measured with CAPS was not significantly reduced with SSRIs compared with placebo.

A systematic review revealed that, of the nonantidepressants used as adjuncts in treating patients who do not achieve remission with SSRIs, the atypical antipsychotic risperidone may have the strongest supporting evidence.12 However, the present study found high rates of antipsychotic use in the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group, which also had the highest all-cause mortality rate. The safety of risperidone as an alternative treatment needs further evaluation.

Some prospective studies have suggested that the α1 blockers doxazosin and prazosin, the latter of which is commonly used for PTSD nightmares, also may improve PTSD symptoms as assessed by CAPS.14,15 Although these results are promising, the trials to date have been conducted with relatively small sample sizes.

With more veterans being treated for PTSD within the VA health care system, the central treatment goal remains: Adequately address the symptoms of PTSD while minimizing the harm caused by medications. Prescribers should limit benzodiazepine and opioid use in this population and consider safer nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment options when possible.

Conclusion

Combat veterans with PTSD who are prescribed benzodiazepines and/or opioids in addition to first-line pharmacotherapy are at significantly increased risk for overall and mental health hospitalization.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that may develop in response to a traumatic event, such as that experienced by a soldier during active combat duty. In 2009, more than 495,000 veterans within the VA health care system were treated for PTSD—nearly triple the number a decade earlier.1 Core symptoms of PTSD include alterations in arousal and reactivity, avoidant behaviors, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and intrusive thoughts and nightmares. All of the symptoms can be debilitating. First-line pharmacotherapy options that target these core symptoms include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).2

The anxiolytic and sedative effects of benzodiazepines may provide quick relief from many of the secondary symptoms of PTSD, including sleep disturbances, irritability, and panic attacks. However, benzodiazepines potentially interfere with the extinction of conditioned fear—a goal integral to certain types of psychotherapy, such as exposure therapy.3,4 In addition, the systematic review and meta-analysis by Guina and colleagues revealed that benzodiazepines are ineffective in the treatment of PTSD.5 The majority of the evaluated studies that used PTSD-specific measures (eg, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [CAPS]) found increased PTSD severity and worse prognosis with use of these medications.5 In 2010, the VA and the DoD released a joint guideline for PTSD management.2 According to the guideline, benzodiazepines cause harm when used in PTSD and are relatively contraindicated in combat veterans because of the higher incidence of comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) in these veterans relative to the general population.2,6

Opioid use also has been linked to poor functional and clinical outcomes in veterans with PTSD. Among patients being treated for opioid use disorder, those with PTSD were less likely to endorse employment as a main source of income and had a higher incidence of recent attempted suicide.7 In a large retrospective cohort study, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom veterans with PTSD who were prescribed opioids were more likely to present to the emergency department (ED) and to be hospitalized for overdoses and injuries.8

Despite the risks of benzodiazepine and opioid use in this patient population, these medications are still often prescribed to veterans with PTSD for symptomatic relief. In fiscal year 2009, across the VHA system 37% of veterans diagnosed with PTSD were prescribed a benzodiazepine, 69% of the time by a mental health provider.9 Among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, those with PTSD were significantly more likely to be prescribed an opioid for diagnosed pain—relative to those with a mental health disorder other than PTSD and those without a mental health disorder.8 Thus, there seems to be a disconnect between guideline recommendations and current practice.

The authors conducted a study to assess the potential risk of hospitalization for veterans with PTSD prescribed first-line pharmacotherapy and those also prescribed concurrent benzodiazepine and/or opioid therapy since the release of the PTSD guideline in 2010.2

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, conducted at the Southern Arizona VA Health Care System (SAVAHCS), the authors analyzed electronic medical record data from November 1, 2009 to August 1, 2015. Study inclusion criteria were veteran, aged 18 to 89 years, diagnosis of PTSD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 309.81), and SSRI or SNRI newly prescribed between November 1, 2010 and August 1, 2013.

Any veteran prescribed at least one 30-day or longer supply of any benzodiazepine or opioid within 1 year before the SSRI/SNRI initial prescription date was excluded from the study. Also excluded was any patient treated for PTSD at a facility outside SAVAHCS or whose 2-year evaluation period extended past August 1, 2015.

Study Groups

An outpatient prescription was determined to be the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription for a patient who received less than a 30-day cumulative supply of any SSRI or SNRI within 1 year before that prescription date. Citalopram, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, levomilnacipran, milnacipran, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, vilazodone, and vortioxetine were the prespecified SSRI/SNRIs included in the study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any benzodiazepine (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy. Alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, and triazolam were the prespecified benzodiazepines included in the study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any opioid (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy. Codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxymorphone, pentazocine, propoxyphene, and tramadol were the prespecified opioids included in this study.

Patients who received at least 1 outpatient prescription for any benzodiazepine and any opioid (minimum 30-day supply) within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were determined to be on concurrent SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy.

The index date was defined as the first date of prescription overlap. If there was no benzodiazepine or opioid prescription within 1 year after the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date, the patient was categorized as being on SSRI/SNRI monotherapy, and the index date was the date of the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription. For each patient, hospitalization data from the 2-year period after the index date were evaluated.

Outcomes and Data Collection

For evaluation of the primary outcome (2-year overall hospitalization risk), the number of unique mental health and medical/surgical hospitalizations was identified by the number of discharge summaries documented in the patient chart during the evaluation period. Time to first hospitalization was recorded for the survival data analysis. Secondary outcomes were mental health hospitalization risk, medical/surgical hospitalization risk, and all-cause mortality within 2 years.

Demographic data that were collected included age, sex, comorbid mental health disorders, comorbid SUDs, and concomitant use of psychotropic medications at index date (baseline). Select comorbid mental health disorders (anxiety, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder) and substance use disorders (alcohol, opioid, illicit drug) also were identified. Data on insomnia and pain comorbidities (headaches or migraines; neuropathy; head, neck, back, arthritis, or joint pain) were collected, as these comorbidities could be indications for prescribing benzodiazepines and opioids. Concomitant baseline use of classes of psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, non-SSRI/SNRI antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, nonbenzodiazepine sedatives/hypnotics) also were documented. Last, hospitalizations within 6 months before the initial SSRI/SNRI prescription date were noted.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze all baseline demographic data. Continuous measures were evaluated with 1-way analyses of variance and post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons, and categorical measures with contingency tables and χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests. When the overall χ2 test was significant across all 4 study groups, post hoc comparisons were performed between the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group and each other group with Bonferroni adjusted for 3 comparisons.

Unadjusted and adjusted Weibull proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate hospitalization risk within 2 years after the index date for the different study groups with the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group as the referent. Robust standard errors were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Weibull model (and not the Cox model) was used because it does not assume hazard remains constant over time, which is appropriate in this instance, as the risk of an adverse event (AE) may be higher when first starting a medication or combination of medications relative to when doses are stabilized. Models were adjusted for age, sex, baseline mental health disorders, and baseline psychotropic medications. As earlier hospitalizations showed evidence of effect modification when this covariate was tested, hazard analyses were limited to patients not previously hospitalized.

The effect size of differences in hospitalization risk meeting statistical significance was assessed by estimating the number needed to harm (NNH) and 95% CIs (not shown) to observe 1 additional hospitalization in each medication group relative to the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group over a 90-day period. A 95% CI for NNH that did not include 0 indicated the NNH was significant at the .05 level.10 All-cause mortality was evaluated with the Fisher exact test with post hoc Bonferroni-corrected comparisons as appropriate.

Results

Of 1,703 patients screened, 613 met all study inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics revealed no significant differences between groups in age or comorbid depression, schizophrenia, or SUDs (Table 1).

With the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group as the referent, all concurrent therapy groups were at significantly increased risk for overall hospitalization within 2 years after the index date (Tables 2 & 3, Figure 2).

Risk for mental health hospitalization was significantly increased in all concurrent therapy groups relative to the referent group.

Although the risk for medical/surgical hospitalization was not significantly increased in the SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy group (AHR, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.67-5.6), a significant difference was found in the SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy group (AHR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.6-12.0; NNH, 42).

Discussion

In 2013, Hawkins and colleagues evaluated hospitalization risk in veterans treated for PTSD within the Northwest VISN 20 between 2004 and 2010.11 Compared with patients treated with only an SSRI or SNRI, those treated with 1 of those medications and a benzodiazepine were at significantly higher risk for overall hospitalization (AHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.38-2.32; P < .001) and mental health hospitalization (AHR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.37-2.53; P < .001). Furthermore, those prescribed a benzodiazepine and an opioid along with an SSRI or SNRI were at higher risk for overall hospitalization (AHR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.22-4.00; P < .001), mental health hospitalization (AHR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.35-2.98; P < .01), medical/surgical hospitalization (AHR, 4.86; 95% CI, 3.30-7.14; P < .001), and ED visits (AHR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.53-2.65; P < .001).

Findings from the present study, which covered a period after the newest PTSD guideline was released,support findings reported by Hawkins and colleagues in their retrospective cohort study covering an earlier period.2,11 In the present study, compared with the monotherapy group, the SSRI/SNRI and benzodiazepine therapy group and the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group were at higher risk for both overall hospitalization and mental health hospitalization within 2 years. However, in a subset of PTSD patients prescribed opioids along with first-line pharmacotherapy, this study found that overall, mental health, and medical/surgical hospitalizations were significantly increased as well. Furthermore, this study found 2-year mortality was significantly higher for the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group than for the SSRI/SNRI monotherapy group.

Adjusted hazard ratios were higher in the present study than those in the study by Hawkins and colleagues,but CIs were wider as well.11 These differences may be attributable to the relatively smaller sample size of the present study and may explain why the HR was higher for the SSRI/SNRI and opioid therapy group than for the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group.

Nevertheless, these results support the growing body of evidence establishing the many risks for AEs when benzodiazepines and opioids are prescribed in the setting of PTSD. Unfortunately, it seems that, against clear guideline recommendations and literature findings, these medications still are being prescribed to this vulnerable, high-risk population.

In the last few months of 2013, the VA health care system launched 2 important medication safety initiatives. The Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) was established as a quality improvement initiative for evidence-based provision of psychotropic medications. One PDSI metric in particular focused on reducing the proportion of veterans with PTSD being treated with benzodiazepines. The Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) came as a response to a dramatic increase in the number of fatal overdoses related to prescription opioids—an increase linked to an unprecedented jump in opioid use for nonmalignant pain. As the present study’s inclusion cutoff date of August 1, 2013, preceded the debut of both PDSI and OSI, the benzodiazepine and opioid prescription rates reported here might be higher than those currently being found under the 2 initiatives.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that might affect the interpretation or generalizability of findings. Requiring at least a 30-day supply for prescription eligibility was an attempt to focus on chronic use of medications rather than on, for example, onetime supplies of opioids for dental procedures. However, prescription fill history was not assessed. Therefore, patients could have been included in certain study groups even if their SSRI, SNRI, benzodiazepine, or opioid prescription was not refilled. Furthermore, only VA medical records were used; non-VA prescriptions were not captured.

In addition, this study was limited to patients who at bare minimum were prescribed an SSRI or an SNRI. Some patients may have been prescribed a benzodiazepine and/or an opioid but were not on appropriate first-line pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These patients were excluded from the study, and their relative hospitalization risk went unexplored. Therefore, the magnitude of the issue at hand might have been underestimated.

Although psychotherapy is a first-line treatment option for PTSD, the study did not assess the potential impact of psychotherapy on outcomes or the groups’ relative proportions of patients undergoing psychotherapy. It is unknown whether the groups were equivalent at baseline in regards to psychotherapy participation rates.

This study did not characterize the specific reasons for hospitalization beyond whether it was for a mental health or a medical/surgical issue; thus, no distinction was made between hospitalizations for an elective procedure and hospitalizations for a drug overdose or an injury. Investigators could characterize admission diagnoses to better assess whether hospitalizations are truly associated with study medications or whether patients are being hospitalized for unrelated reasons. In addition, they could elucidate the true nature of hospitalization risk associated with SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid use by comparing admission diagnoses made before and after initiation of these pharmacologic therapies.

This study also could not assess outcomes for patients who presented to the ED but were not admitted. If the hospital’s floor and ED beds were at full capacity, some patients might have been transferred to an outside facility. However, this scenario is not common at SAVAHCS, where the study was conducted.

Although some comorbid conditions were noted, the study did not evaluate whether its patients had a compelling indication for benzodiazepines in particular. Opioid use is very limited to the treatment of pain, and the majority of the patients on opioid therapy in this study had a diagnosed pain syndrome.

Because of the study’s sample size and power limitations, patients were eligible to be included in a concurrent therapy group if a benzodiazepine, an opioid, or both were added no later than 1 year after SSRI/SNRI initiation. This gap of up to 1 year might have introduced some variability in exposure to risk from earlier prescribed medications. However, sensitivity analyses were performed with multiple constructed Weibull models of time to hospitalization based on subsets with varying overlapping medication gaps. Analyses revealed relatively stable HRs, suggesting that potential bias did not occur.

Future Directions

Investigators could explore the higher all-cause mortality rates in the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group, as this study did not assess cause of death in these patients. Whether any patients died of reasons directly attributable to benzodiazepines or opioids is unknown.

That SSRIs and SNRIs are the only established first-line pharmacologic treatment options for PTSD symptoms partly accounts for the widespread use of benzodiazepines in this population. For that reason, beyond characterizing the many risks associated with using benzodiazepines to manage these symptoms, there is a huge need to research the viability of other pharmacologic agents in treating PTSD. This is especially important given the slower onset to efficacy of the SSRIs and SNRIs; per estimates, only up to 60% of patients respond to SSRIs, and 20% to 30% achieve full remission of PTSD.12 Furthermore, these rates likely are even lower for combat veterans than those for the general population. Several trials discussed in a 2009 guideline review of the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and PTSD have called into question the efficacy of SSRIs for combat-related PTSD.13 In these randomized, controlled trials, change in PTSD symptom severity as measured with CAPS was not significantly reduced with SSRIs compared with placebo.

A systematic review revealed that, of the nonantidepressants used as adjuncts in treating patients who do not achieve remission with SSRIs, the atypical antipsychotic risperidone may have the strongest supporting evidence.12 However, the present study found high rates of antipsychotic use in the SSRI/SNRI, benzodiazepine, and opioid therapy group, which also had the highest all-cause mortality rate. The safety of risperidone as an alternative treatment needs further evaluation.

Some prospective studies have suggested that the α1 blockers doxazosin and prazosin, the latter of which is commonly used for PTSD nightmares, also may improve PTSD symptoms as assessed by CAPS.14,15 Although these results are promising, the trials to date have been conducted with relatively small sample sizes.

With more veterans being treated for PTSD within the VA health care system, the central treatment goal remains: Adequately address the symptoms of PTSD while minimizing the harm caused by medications. Prescribers should limit benzodiazepine and opioid use in this population and consider safer nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment options when possible.

Conclusion

Combat veterans with PTSD who are prescribed benzodiazepines and/or opioids in addition to first-line pharmacotherapy are at significantly increased risk for overall and mental health hospitalization.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Jenkyn AB, Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ. Gender differences in prescribing among veterans diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(suppl 2):S542-S548.

2. Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/PTSD-full-2010c .pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed July 12, 2015.

3. Marks IM, Swinson RP, Baso˘glu M, et al. Alprazolam and exposure alone and combined in panic disorder with agoraphobia. A controlled study in London and Toronto. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:776-787.

4. Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Acute and delayed effects of alprazolam on flight phobics during exposure. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(9):831-841.

5. Guina J, Rossetter SR, DeRhodes BJ, Nahhas RW, Welton RS. Benzodiazepines for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(4):281-303.

6. Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(3):456-465.

7. Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Shanahan M. The costs and outcomes of treatment for opioid dependence associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(8):940-945.

8. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

9. Abrams TE, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, Friedman MJ. Aligning clinical practice to PTSD treatment guidelines: medication prescribing by provider type. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):142-148.

10. Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1492-1495.

11. Hawkins EJ, Malte CA, Grossbard J, Saxon AJ, Imel ZE, Kivlahan DR. Comparative safety of benzodiazepines and opioids among Veterans Affairs patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):354-362.

12. Berger W, Mendlowicz MV, Marques-Portella C, et al. Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):169-180.

13. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, Ursano RJ. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):204-213.

14. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

15. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

1. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Jenkyn AB, Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ. Gender differences in prescribing among veterans diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(suppl 2):S542-S548.

2. Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/PTSD-full-2010c .pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed July 12, 2015.

3. Marks IM, Swinson RP, Baso˘glu M, et al. Alprazolam and exposure alone and combined in panic disorder with agoraphobia. A controlled study in London and Toronto. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:776-787.

4. Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Acute and delayed effects of alprazolam on flight phobics during exposure. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(9):831-841.

5. Guina J, Rossetter SR, DeRhodes BJ, Nahhas RW, Welton RS. Benzodiazepines for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(4):281-303.

6. Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(3):456-465.

7. Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S, Shanahan M. The costs and outcomes of treatment for opioid dependence associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(8):940-945.

8. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

9. Abrams TE, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, Friedman MJ. Aligning clinical practice to PTSD treatment guidelines: medication prescribing by provider type. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):142-148.

10. Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1492-1495.

11. Hawkins EJ, Malte CA, Grossbard J, Saxon AJ, Imel ZE, Kivlahan DR. Comparative safety of benzodiazepines and opioids among Veterans Affairs patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):354-362.

12. Berger W, Mendlowicz MV, Marques-Portella C, et al. Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):169-180.

13. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, Ursano RJ. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):204-213.

14. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

15. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

How Do You Treat a Patient With Refractory Headache?

RIVIERA BEACH, FL—Neurologists sometimes encounter patients with headaches that have not responded to prior treatment. These patients may be demoralized, and neurologists may be at a loss for a way to relieve their pain. Effective treatment is possible for many of these patients, according to Thomas N. Ward, MD, Emeritus Professor of Neurology at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. He described the process of differential diagnosis, as well as outpatient and inpatient therapeutic options for refractory headache, at the 44th Annual Meeting of the Southern Clinical Neurological Society.

Confirm the Diagnosis

When faced with a patient with refractory headache, a neurologist should first verify the diagnosis and rule out the possibility of secondary headache. These steps will improve the likelihood of a positive outcome. “If you follow the fundamentals and treat the type of headache it is, you usually get a pretty good result,” said Dr. Ward.

A patient with headache on 15 days per month or more has chronic daily headache. The duration of the headaches can provide the basis for a more specific diagnosis. Headaches of short duration (ie, less than four hours) may be symptoms of cluster headache, chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, hypnic headache, or trigeminal neuralgia. Headaches of long duration (ie, more than four hours) may indicate chronic migraine, chronic tension-type headache, hemicrania continua, or new daily persistent headache.

A patient with headache on 15 or more days per month, and for whom headaches on at least eight days per month meet the criteria of migraine, has chronic migraine. The two best-supported treatments for chronic migraine are topiramate and onabotulinumtoxinA. In patients with chronic migraine, what appears to be a tension-type headache may eventually declare its true nature and become a migraine headache with accompanying pounding and photophobia. What looks like a tension-type headache in a migraineur may respond to a triptan, said Dr. Ward.

Stop Medication Overuse

Medication overuse can confound the diagnosis and alter the headache itself. Many patients with refractory headache overuse medication but may fail to mention this to a neurologist. The overused medication may be a prescription or an over-the-counter drug such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or a combination that includes caffeine. Drugs with short half-lives appear to be particularly likely to cause medication overuse headache.

Some patients may be overusing opioids for their headache. “Opioids for headache are not a good idea,” said Dr. Ward. “Nothing good will come of it.” These drugs may cause central sensitization and reduce the efficacy of other headache remedies.

The risk of medication overuse headache increases if the patient uses combination analgesics, ergotamine, or triptans on 10 or more days per month, or simple analgesics on more than 15 days per month. “The clinical question I always ask patients is, ‘Are you taking more pills and having more headaches?’ If the answer is ‘yes,’ then they have medication overuse headache,” said Dr. Ward.

If patients stop taking the overused medication, they may have a withdrawal headache that is worse than their normal headache. Medication overuse headache usually resolves itself after the overuse is stopped, and bridge therapies such as steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or dihydroergotamine may alleviate pain during withdrawal. “If you can get the patient over that hump, which can be several days of bad headache, they often do remarkably better,” said Dr. Ward.

Get Back to Basics

Taking a careful history is essential to successful treatment. “If you do not get the original history, you could miss the diagnosis,” said Dr. Ward. The neurologist must know about the mode of onset of the patient’s headache, and also know all about his or her prior headaches.

A patient with refractory headache should undergo a thorough head and neck examination, but physicians sometimes neglect to perform it. An MRI of the brain with gadolinium generally is warranted. About 90% of patients with low CSF pressure have pachymeningeal enhancement, which is visible on MRI performed with gadolinium, said Dr. Ward. Blood work, however, usually reveals little and appears normal. Sometimes thyroid tests, a Lyme test, a blood count, and a serum creatinine test are helpful, and a serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate test in those over age 50 is important to obtain.

Lumbar punctures may be underused, said Dr. Ward. Although it is uncommon, some patients present with high intracranial pressure, but without papilledema. The correct diagnosis can lead to effective treatment for these patients.

Effective treatment also is more likely when the neurologist gets to know the patient. He or she can use preventive medications to reduce the number of headache days. The literature suggests that successful preventive therapy should achieve a target of four headache days or fewer per month.

Neurologists also should treat the patient’s comorbid conditions, which often are psychiatric in people with refractory headache. It is unusual to see a patient with chronic migraine who does not have anxiety and depression, said Dr. Ward. Patients with refractory headache also may have phobias, bipolar disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder, which is a significant confounder.

To Admit or Not to Admit?

A neurologist may have to decide whether to admit to the hospital a patient with chronic headache who is not doing well. First, the neurologist and patient should agree on a therapeutic target. Outpatient treatment works well if the patient is motivated and compliant and does not have confounding conditions. If the therapeutic target cannot be met through outpatient treatment, the neurologist should consider hospital admission. Insurance companies generally will cover three days of inpatient treatment, said Dr. Ward.

Neurologists have many options for inpatient treatment of refractory headache. Repetitive dihydroergotamine, known as the Raskin protocol, is highly effective if administered correctly. Dihydroergotamine should be given three times per day. “If you order it q. 8 h., the nurse will wake your patient up in the middle of the night, and waking up a patient with benign headaches is not a good idea,” said Dr. Ward. The dose must not be sufficient to cause nausea, because nauseating the patient can exacerbate headaches. “We usually premedicate with metoclopramide or prochlorperazine for nausea, but both of those drugs … also are good headache remedies.”

The Raskin protocol requires the withdrawal of other analgesics. The protocol typically lasts for three days, and most patients have good outcomes at this point. Extending the protocol to six or seven days may increase the number of patients with good outcomes. The success rate for the Raskin protocol is between 60% and 70%, said Dr. Ward. Patients who are pregnant or who have coronary artery disease should not receive dihydroergotamine, however.

Another option for inpatient treatment is IV chlorpromazine. The goal of this treatment is to induce a light sleep and maintain it for two or three days. The neurologist may start with a dose of 10 mg t.i.d. and monitor the patient’s response. The drug effectively suppresses narcotic withdrawal symptoms, so the neurologist may withdraw overused medications while the patient is asleep. Chlorpromazine may cause QT prolongation, so the patient should undergo cardiac monitoring. The drug also causes orthostatic hypotension, so patients should remain on bed rest and receive prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis, said Dr. Ward.

IV valproate is an excellent choice if the patient has cardiac problems or bipolar disease, he added. The drug can be administered in a single dose of between 300 mg and 500 mg run in rapidly. “You can run in a whole loading dose in five or 10 minutes with virtually no side effects,” said Dr. Ward. Treatment can be administered b.i.d. or t.i.d. for two or three days. Pregnant patients should not receive valproate, however. Yet another option is IV magnesium, although the evidence for its efficacy is mostly anecdotal. A protocol of 1 to 2 g administered over 10 to 20 minutes, repeated several times per day, may be effective. It is advisable to monitor the patient’s serum magnesium levels to ensure that they do not become excessive. Magnesium may adversely affect fetal bone development, so neurologists should exercise caution when considering the drug for a pregnant patient. IV magnesium is “an excellent choice for hemiplegic migraine,” said Dr. Ward.

If the patient’s occipital nerves are tender, occipital nerve blockade may relieve pain. IV ketorolac, in 30-mg doses t.i.d. or q.i.d., may alleviate breakthrough headaches. Lidocaine patches can reduce back or neck pain for as long as 12 hours daily.

Abruptly withdrawing butalbital entails a risk of seizures and delirium. Neurologists may wish to administer phenobarbital in its place, as a single bedtime dose, while they are tapering or stopping butalbital. A 30-mg dose of phenobarbital may be substituted for every 100 mg of butalbital, said Dr. Ward.

Suggested Reading

Ford RG, Ford KT. Continuous intravenous dihydroergotamine in the treatment of intractable headache. Headache. 1997;37(3):129-136.

Lai TH, Wang SJ. Update of inpatient treatment for refractory chronic daily headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(1):5.

Levin M. Opioids in headache. Headache. 2014;54(1):12-21.

Lipton RB, Silberstein SD, Saper JR, et al. Why headache treatment fails. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1064-1070.

RIVIERA BEACH, FL—Neurologists sometimes encounter patients with headaches that have not responded to prior treatment. These patients may be demoralized, and neurologists may be at a loss for a way to relieve their pain. Effective treatment is possible for many of these patients, according to Thomas N. Ward, MD, Emeritus Professor of Neurology at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. He described the process of differential diagnosis, as well as outpatient and inpatient therapeutic options for refractory headache, at the 44th Annual Meeting of the Southern Clinical Neurological Society.

Confirm the Diagnosis

When faced with a patient with refractory headache, a neurologist should first verify the diagnosis and rule out the possibility of secondary headache. These steps will improve the likelihood of a positive outcome. “If you follow the fundamentals and treat the type of headache it is, you usually get a pretty good result,” said Dr. Ward.