User login

New and Updated FDA Boxed Warnings

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. These and other label changes are searchable in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

IMODIUM (LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE):

- New warning December 2016

WARNING: TORSADES DE POINTES AND SUDDEN DEATH

Cases of Torsades de Pointes, cardiac arrest, and death have been reported with the use of a higher than recommended dosages of Imodium (see WARNINGS and OVERDOSAGE).

Imodium is contraindicated in pediatric patients less than 2 years of age (see CONTRANIDICATIONS).

Avoid Imodium dosages higher than recommended in adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older due to the risk of serious cardiac adverse reactions (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

AUBAGIO (TERIFLUNOMIDE) TABLETS:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Risk of Teratogenicity

Aubagio is contraindicated for use in pregnant women and in women of reproductive potential who are not using effective contraception because of the potential for fetal harm. Teratogenicity and embryolethality occurred in animals at plasma teriflunomide exposures lower than that in humans. Exclude pregnancy before the start of treatment with Aubagio in females of reproductive potential. Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during Aubagio treatment and during an accelerated drug elimination procedure after Aubagio treatment. Stop Aubagio and use an accelerated drug elimination procedure if the patient becomes pregnant.

PROMACTA (ELTROMBOPAG) TABLETS, FOR ORAL USE AND ORAL SUSPENSION:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Chronic Hepatitis C

Promacta may increase the risk of severe and potentially lifethreatening hepatotoxicity. Monitor hepatic function and discontinue dosing as recommended.

ICLUSIG (PONATINIB HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

WARNING: ARTERIAL OCCLUSION, VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM, HEART FAILURE, and HEPATOTOXICITY

Arterial Occlusion

Arterial occlusions have occurred in at least 35% of Iclusig-treated patients. Some patients experienced more than 1 type of event. Events observed included fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, stenosis of large arterial vessels of the brain, severe peripheral vascular disease, and the need for urgent revascularization procedures. Patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors, including patients age 50 years or younger, experienced these events. Monitor for evidence of arterial occlusion. Interrupt or stop Iclusig immediately for arterial occlusion.

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous occlusive events have occurred in 6% of Iclusig-treated patients. Monitor for evidence of venous thromboembolism. Consider dose modification or discontinuation of Iclusig in patients who develop serious venous thromboembolism.

Heart Failure

Heart failure, including fatalities, occurred in 9% of Iclusig-treated patients.

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. These and other label changes are searchable in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

IMODIUM (LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE):

- New warning December 2016

WARNING: TORSADES DE POINTES AND SUDDEN DEATH

Cases of Torsades de Pointes, cardiac arrest, and death have been reported with the use of a higher than recommended dosages of Imodium (see WARNINGS and OVERDOSAGE).

Imodium is contraindicated in pediatric patients less than 2 years of age (see CONTRANIDICATIONS).

Avoid Imodium dosages higher than recommended in adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older due to the risk of serious cardiac adverse reactions (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

AUBAGIO (TERIFLUNOMIDE) TABLETS:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Risk of Teratogenicity

Aubagio is contraindicated for use in pregnant women and in women of reproductive potential who are not using effective contraception because of the potential for fetal harm. Teratogenicity and embryolethality occurred in animals at plasma teriflunomide exposures lower than that in humans. Exclude pregnancy before the start of treatment with Aubagio in females of reproductive potential. Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during Aubagio treatment and during an accelerated drug elimination procedure after Aubagio treatment. Stop Aubagio and use an accelerated drug elimination procedure if the patient becomes pregnant.

PROMACTA (ELTROMBOPAG) TABLETS, FOR ORAL USE AND ORAL SUSPENSION:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Chronic Hepatitis C

Promacta may increase the risk of severe and potentially lifethreatening hepatotoxicity. Monitor hepatic function and discontinue dosing as recommended.

ICLUSIG (PONATINIB HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

WARNING: ARTERIAL OCCLUSION, VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM, HEART FAILURE, and HEPATOTOXICITY

Arterial Occlusion

Arterial occlusions have occurred in at least 35% of Iclusig-treated patients. Some patients experienced more than 1 type of event. Events observed included fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, stenosis of large arterial vessels of the brain, severe peripheral vascular disease, and the need for urgent revascularization procedures. Patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors, including patients age 50 years or younger, experienced these events. Monitor for evidence of arterial occlusion. Interrupt or stop Iclusig immediately for arterial occlusion.

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous occlusive events have occurred in 6% of Iclusig-treated patients. Monitor for evidence of venous thromboembolism. Consider dose modification or discontinuation of Iclusig in patients who develop serious venous thromboembolism.

Heart Failure

Heart failure, including fatalities, occurred in 9% of Iclusig-treated patients.

The FDA’s MedWatch program safety labeling changes for boxed warnings are compiled quarterly for drugs and therapeutic biologics where important changes have been made to the safety information. These and other label changes are searchable in the Drug Safety Labeling Changes (SLC) database, where data are available to the public in downloadable and searchable formats. Boxed warnings are ordinarily used to highlight either adverse reactions so serious in proportion to the potential bene t from the drug that it is essential that it be considered in assessing the risks and bene ts of using the drug; or serious adverse reactions that can be prevented/reduced in frequency or severity by appropriate use of the drug; or FDA approved the drug with restrictions to ensure safe use because FDA concluded that the drug can be safely used only if distribution or use is restricted.

IMODIUM (LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE):

- New warning December 2016

WARNING: TORSADES DE POINTES AND SUDDEN DEATH

Cases of Torsades de Pointes, cardiac arrest, and death have been reported with the use of a higher than recommended dosages of Imodium (see WARNINGS and OVERDOSAGE).

Imodium is contraindicated in pediatric patients less than 2 years of age (see CONTRANIDICATIONS).

Avoid Imodium dosages higher than recommended in adults and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older due to the risk of serious cardiac adverse reactions (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION).

AUBAGIO (TERIFLUNOMIDE) TABLETS:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Risk of Teratogenicity

Aubagio is contraindicated for use in pregnant women and in women of reproductive potential who are not using effective contraception because of the potential for fetal harm. Teratogenicity and embryolethality occurred in animals at plasma teriflunomide exposures lower than that in humans. Exclude pregnancy before the start of treatment with Aubagio in females of reproductive potential. Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during Aubagio treatment and during an accelerated drug elimination procedure after Aubagio treatment. Stop Aubagio and use an accelerated drug elimination procedure if the patient becomes pregnant.

PROMACTA (ELTROMBOPAG) TABLETS, FOR ORAL USE AND ORAL SUSPENSION:

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

Chronic Hepatitis C

Promacta may increase the risk of severe and potentially lifethreatening hepatotoxicity. Monitor hepatic function and discontinue dosing as recommended.

ICLUSIG (PONATINIB HYDROCHLORIDE):

- Edited and updated warning December 2016

WARNING: ARTERIAL OCCLUSION, VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM, HEART FAILURE, and HEPATOTOXICITY

Arterial Occlusion

Arterial occlusions have occurred in at least 35% of Iclusig-treated patients. Some patients experienced more than 1 type of event. Events observed included fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, stenosis of large arterial vessels of the brain, severe peripheral vascular disease, and the need for urgent revascularization procedures. Patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors, including patients age 50 years or younger, experienced these events. Monitor for evidence of arterial occlusion. Interrupt or stop Iclusig immediately for arterial occlusion.

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous occlusive events have occurred in 6% of Iclusig-treated patients. Monitor for evidence of venous thromboembolism. Consider dose modification or discontinuation of Iclusig in patients who develop serious venous thromboembolism.

Heart Failure

Heart failure, including fatalities, occurred in 9% of Iclusig-treated patients.

CAR T-cell trial in adult ALL shut down

After 2 clinical holds in 2016 and 5 patient deaths, the Seattle biotech Juno Therapeutics is shutting down the phase 2 ROCKET trial of JCAR015.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy JCAR015 was being tested in adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

“We have decided not to move forward . . . at this time,” CEO Hans Bishop said in a statement, “even though it generated important learnings for us and the immunotherapy field.”

He said the company remains “committed to developing better treatment for patients battling ALL.”

The first clinical hold of the ROCKET trial occurred in July after 2 patients died. The company attributed the deaths primarily to the addition of fludarabine to the regimen.

Juno removed fludarabine from the treatment protocol, the clinical hold was lifted, and the trial resumed.

Then, in November, 2 more patients died from cerebral edema, and the trial was put on hold once again.

One patient had died earlier in 2016, totaling 5 patient deaths from cerebral edema, although the earliest death was not necessarily related to treatment, the company stated.

Juno attributed the deaths to multiple factors, including the patients’ treatment history and treatment received at the beginning of the trial.

Juno plans to start a new adult ALL trial in 2018. The therapy, they say, is more similar to JCAR017, which is being tested in pediatric patients.

ROCKET is not the first trial of JCAR015 to be placed on hold.

In 2014, after 2 patients died of cytokine release syndrome, the phase 1 trial was placed on clinical hold.

Juno made changes to the enrollment criteria and dosing, and the hold was lifted. Results from this trial were presented at ASCO 2015 and ASCO 2016. ![]()

After 2 clinical holds in 2016 and 5 patient deaths, the Seattle biotech Juno Therapeutics is shutting down the phase 2 ROCKET trial of JCAR015.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy JCAR015 was being tested in adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

“We have decided not to move forward . . . at this time,” CEO Hans Bishop said in a statement, “even though it generated important learnings for us and the immunotherapy field.”

He said the company remains “committed to developing better treatment for patients battling ALL.”

The first clinical hold of the ROCKET trial occurred in July after 2 patients died. The company attributed the deaths primarily to the addition of fludarabine to the regimen.

Juno removed fludarabine from the treatment protocol, the clinical hold was lifted, and the trial resumed.

Then, in November, 2 more patients died from cerebral edema, and the trial was put on hold once again.

One patient had died earlier in 2016, totaling 5 patient deaths from cerebral edema, although the earliest death was not necessarily related to treatment, the company stated.

Juno attributed the deaths to multiple factors, including the patients’ treatment history and treatment received at the beginning of the trial.

Juno plans to start a new adult ALL trial in 2018. The therapy, they say, is more similar to JCAR017, which is being tested in pediatric patients.

ROCKET is not the first trial of JCAR015 to be placed on hold.

In 2014, after 2 patients died of cytokine release syndrome, the phase 1 trial was placed on clinical hold.

Juno made changes to the enrollment criteria and dosing, and the hold was lifted. Results from this trial were presented at ASCO 2015 and ASCO 2016. ![]()

After 2 clinical holds in 2016 and 5 patient deaths, the Seattle biotech Juno Therapeutics is shutting down the phase 2 ROCKET trial of JCAR015.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy JCAR015 was being tested in adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

“We have decided not to move forward . . . at this time,” CEO Hans Bishop said in a statement, “even though it generated important learnings for us and the immunotherapy field.”

He said the company remains “committed to developing better treatment for patients battling ALL.”

The first clinical hold of the ROCKET trial occurred in July after 2 patients died. The company attributed the deaths primarily to the addition of fludarabine to the regimen.

Juno removed fludarabine from the treatment protocol, the clinical hold was lifted, and the trial resumed.

Then, in November, 2 more patients died from cerebral edema, and the trial was put on hold once again.

One patient had died earlier in 2016, totaling 5 patient deaths from cerebral edema, although the earliest death was not necessarily related to treatment, the company stated.

Juno attributed the deaths to multiple factors, including the patients’ treatment history and treatment received at the beginning of the trial.

Juno plans to start a new adult ALL trial in 2018. The therapy, they say, is more similar to JCAR017, which is being tested in pediatric patients.

ROCKET is not the first trial of JCAR015 to be placed on hold.

In 2014, after 2 patients died of cytokine release syndrome, the phase 1 trial was placed on clinical hold.

Juno made changes to the enrollment criteria and dosing, and the hold was lifted. Results from this trial were presented at ASCO 2015 and ASCO 2016. ![]()

Exercise better than meds to reduce fatigue in cancer patients

Exercise and/or psychological therapy work better than medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers conducted a review and meta-analysis of more than 113 studies and found that exercise and psychological interventions, as well as a combination of both, were associated with reduced fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

However, pharmaceutical interventions were not associated with the same magnitude of improvement.

The researchers therefore concluded that exercise and psychological therapy should be recommended over medications.

“If a cancer patient is having trouble with fatigue, rather than looking for extra cups of coffee, a nap, or a pharmaceutical solution, consider a 15-minute walk,” said study author Karen Mustian, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“It’s a really simple concept, but it’s very hard for patients and the medical community to wrap their heads around it because these interventions have not been front-and-center in the past. Our research gives clinicians a valuable asset to alleviate cancer-related fatigue.”

Dr Mustian and her colleagues reached their conclusions after analyzing data from 113 randomized clinical trials testing various treatments for cancer-related fatigue.

There were 11,525 patients enrolled in these studies. Nearly half (46.9%) were women with breast cancer. Ten studies focused on other types of cancer and enrolled only men.

Dr Mustian and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis to establish and compare the mean weighted effect sizes (WESs) of the fatigue treatments.

The team found that exercise alone—whether aerobic or anaerobic—reduced cancer-related fatigue most significantly. The WES was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.25-0.36; P<0.001).

Psychological interventions—such as therapy designed to provide education, change personal behavior, and adapt the way a person thinks about his or her circumstances—also improved fatigue. The WES was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.330.30; P<0.001).

A combination of psychological interventions and exercise had a significant improvement on fatigue as well. The WES was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.13-0.38; P<0.001).

However, the drugs tested for treating cancer-related fatigue—paroxetine hydrochloride, modafinil, armodafinil, methylphenidate hydrochloride, dexymethylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and methylprednisolone—were not as effective as the other interventions. The WES was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.00-0.19; P=0.05).

“The literature bears out that these drugs don’t work very well, although they are continually prescribed,” Dr Mustian said. “Cancer patients already take a lot of medications, and they all come with risks and side effects. So any time you can subtract a pharmaceutical from the picture it usually benefits patients.” ![]()

Exercise and/or psychological therapy work better than medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers conducted a review and meta-analysis of more than 113 studies and found that exercise and psychological interventions, as well as a combination of both, were associated with reduced fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

However, pharmaceutical interventions were not associated with the same magnitude of improvement.

The researchers therefore concluded that exercise and psychological therapy should be recommended over medications.

“If a cancer patient is having trouble with fatigue, rather than looking for extra cups of coffee, a nap, or a pharmaceutical solution, consider a 15-minute walk,” said study author Karen Mustian, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“It’s a really simple concept, but it’s very hard for patients and the medical community to wrap their heads around it because these interventions have not been front-and-center in the past. Our research gives clinicians a valuable asset to alleviate cancer-related fatigue.”

Dr Mustian and her colleagues reached their conclusions after analyzing data from 113 randomized clinical trials testing various treatments for cancer-related fatigue.

There were 11,525 patients enrolled in these studies. Nearly half (46.9%) were women with breast cancer. Ten studies focused on other types of cancer and enrolled only men.

Dr Mustian and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis to establish and compare the mean weighted effect sizes (WESs) of the fatigue treatments.

The team found that exercise alone—whether aerobic or anaerobic—reduced cancer-related fatigue most significantly. The WES was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.25-0.36; P<0.001).

Psychological interventions—such as therapy designed to provide education, change personal behavior, and adapt the way a person thinks about his or her circumstances—also improved fatigue. The WES was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.330.30; P<0.001).

A combination of psychological interventions and exercise had a significant improvement on fatigue as well. The WES was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.13-0.38; P<0.001).

However, the drugs tested for treating cancer-related fatigue—paroxetine hydrochloride, modafinil, armodafinil, methylphenidate hydrochloride, dexymethylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and methylprednisolone—were not as effective as the other interventions. The WES was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.00-0.19; P=0.05).

“The literature bears out that these drugs don’t work very well, although they are continually prescribed,” Dr Mustian said. “Cancer patients already take a lot of medications, and they all come with risks and side effects. So any time you can subtract a pharmaceutical from the picture it usually benefits patients.” ![]()

Exercise and/or psychological therapy work better than medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers conducted a review and meta-analysis of more than 113 studies and found that exercise and psychological interventions, as well as a combination of both, were associated with reduced fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

However, pharmaceutical interventions were not associated with the same magnitude of improvement.

The researchers therefore concluded that exercise and psychological therapy should be recommended over medications.

“If a cancer patient is having trouble with fatigue, rather than looking for extra cups of coffee, a nap, or a pharmaceutical solution, consider a 15-minute walk,” said study author Karen Mustian, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“It’s a really simple concept, but it’s very hard for patients and the medical community to wrap their heads around it because these interventions have not been front-and-center in the past. Our research gives clinicians a valuable asset to alleviate cancer-related fatigue.”

Dr Mustian and her colleagues reached their conclusions after analyzing data from 113 randomized clinical trials testing various treatments for cancer-related fatigue.

There were 11,525 patients enrolled in these studies. Nearly half (46.9%) were women with breast cancer. Ten studies focused on other types of cancer and enrolled only men.

Dr Mustian and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis to establish and compare the mean weighted effect sizes (WESs) of the fatigue treatments.

The team found that exercise alone—whether aerobic or anaerobic—reduced cancer-related fatigue most significantly. The WES was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.25-0.36; P<0.001).

Psychological interventions—such as therapy designed to provide education, change personal behavior, and adapt the way a person thinks about his or her circumstances—also improved fatigue. The WES was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.330.30; P<0.001).

A combination of psychological interventions and exercise had a significant improvement on fatigue as well. The WES was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.13-0.38; P<0.001).

However, the drugs tested for treating cancer-related fatigue—paroxetine hydrochloride, modafinil, armodafinil, methylphenidate hydrochloride, dexymethylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and methylprednisolone—were not as effective as the other interventions. The WES was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.00-0.19; P=0.05).

“The literature bears out that these drugs don’t work very well, although they are continually prescribed,” Dr Mustian said. “Cancer patients already take a lot of medications, and they all come with risks and side effects. So any time you can subtract a pharmaceutical from the picture it usually benefits patients.” ![]()

More Than “Teen Angst”: What to Watch For

The incidence of high-risk behavior among teenagers has attracted increased media attention lately. It feels like a new report surfaces every day detailing the death of one or more teens as a result of alcohol, illicit drug use, or speeding. These risky behaviors grab our attention; they are overt and somewhat public. But behaviors that correlate with anxiety and depression, which can in turn lead to suicide or suicidal ideation, are more subtle—and that is what concerns me.

The data on suicide is staggering. On a daily basis, almost 3,000 people worldwide complete suicide, and approximately 20 times as many survive a suicide attempt.1 Annually, deaths resulting from suicide exceed deaths from homicide and war combined.2 In 2013, there were 41,149 suicides in the US—that translates to a rate of 113 suicides each day, or one every 13 minutes.3 Suicide has surpassed homicide to become the second leading cause of death among 10- to 29-year-olds; in 2012, suicide claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people within this age bracket.4,5 In the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 17.7% of high school students reported seriously considering suicide during the prior 12 months, and nearly 9% of those students had attempted suicide during that same period.6 I wonder how many of those students exhibited telling behaviors that went unnoticed.

What are these subtle signs that are so easily overlooked? Behaviors most might consider “within the norm” of today’s youth—hours playing video games, sending hundreds of texts every day, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep. Research has demonstrated that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the incidence of depression in adolescents.7 A 2014 study of European teens published in World Psychiatry found that the adolescents most at risk for symptoms of depression and anxiety are those who are fixated on media, don’t get enough sleep, and have a sedentary lifestyle.8 Hmm... sounds like many US teenagers today. While that doesn’t mean that every teen who lacks sleep, plays video games, or isn’t active is at risk, we do need to pay closer attention to them, because this combination exacerbates risk.

There’s another unhealthy habit that contributes to the risk for teen suicidality: smoking and use of electronic vapor products (EVPs). The 2015 YRBS, which surveyed more than 15,000 high school students, noted that 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users. Analysis of that data identified associations between health-risk behaviors and both cigarette smoking and EVP use.9 Teens who smoked or used EVPs were more likely to engage in violence, substance abuse, and other high-risk behaviors, compared with nonusers. Moreover, compared with nonusers, cigarette-only, EVP-only, and dual smokers were significantly more likely to attempt suicide; cigarette-only smokers were more likely than EVP-only users to attempt suicide.9

Smoking, inactivity, sleep deprivation, and social isolation (because texting or face-timing with your friends is not being social) are a recipe for depression and anxiety in an adolescent. Sleep deprivation alone has been linked to depression and may be associated with a decreased ability to control, inhibit, or change emotional responses.10 Far too often, teens view suicide as the only relief from these feelings.

Awareness of this problem has grown in the past 30 years. The YRBS was developed in 1990 to monitor priority health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death, disability, and social problems among youth in the US—one of which is suicide.11 In 2001, the Department of Health and Human Services introduced the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, the first national program of its kind, and released an evidence-based practice guide for school-based suicide prevention plans.12 The 2002 Institute of Medicine report Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative recognized the need for early recognition and prevention of suicidality.13 And yet, we still have the staggering statistics I cited earlier.

Because of their proximity to children and adolescents, schools are frequently viewed as an integral setting for youth suicide prevention efforts. It is encouraging that suicide prevention programs exist in more than 77% of US public schools—but disheartening that it is not 100%.

And what about the rest of us? What can we, as health care providers, do to stem this tide of teen suicide? The importance of early prevention strategies to reduce onset of suicidal thoughts and help identify persons who are at risk for or are currently contemplating suicide cannot be overemphasized. We need more health care practitioners who are trained to assess suicide plans and to intervene with young persons. This involves education in recognizing risk factors and making appropriate referrals, expanding access to social services, reducing stigma and other barriers to seeking help, and providing awareness that suicide prevention is paramount.

It is incumbent on us as health care providers to screen for and ask our teenaged patients about those subtle behaviors. As adults, it is our responsibility to support and watch over our youth. In the words of former Surgeon General David Satcher, “We must act now. We cannot change the past, but together we can shape a different future.”14

1. World Health Organization. World Suicide Prevention Day. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s16/en/. Accessed February 2, 2017

2. World Health Organization. Suicide huge but preventable public health problem, says WHO. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr61/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

3. CDC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed February 2, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Suicide. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

5. CDC. Suicide trends among persons aged 10-24 years—United States, 1994-2012. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6408.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

6. CDC. Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behavior. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991-2013. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

7. Zahl T, Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and symptoms of major depression in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161711.

8. Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):78-86.

9. Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, King BA. Adolescent risk behaviors and use of electronic vapor products and cigarettes. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162921.

10. National Sleep Foundation. Adolescent sleep needs and patterns. https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/sleep_and_teens_report1.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

11. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) overview. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm. Accessed February 2, 2017.

12. Cooper GD, Clements PT, Holt K. A review and application of suicide prevention programs in high school settings. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(11):696-702.

13. Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2002.

14. US Public Health Service. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC: 1999.

The incidence of high-risk behavior among teenagers has attracted increased media attention lately. It feels like a new report surfaces every day detailing the death of one or more teens as a result of alcohol, illicit drug use, or speeding. These risky behaviors grab our attention; they are overt and somewhat public. But behaviors that correlate with anxiety and depression, which can in turn lead to suicide or suicidal ideation, are more subtle—and that is what concerns me.

The data on suicide is staggering. On a daily basis, almost 3,000 people worldwide complete suicide, and approximately 20 times as many survive a suicide attempt.1 Annually, deaths resulting from suicide exceed deaths from homicide and war combined.2 In 2013, there were 41,149 suicides in the US—that translates to a rate of 113 suicides each day, or one every 13 minutes.3 Suicide has surpassed homicide to become the second leading cause of death among 10- to 29-year-olds; in 2012, suicide claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people within this age bracket.4,5 In the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 17.7% of high school students reported seriously considering suicide during the prior 12 months, and nearly 9% of those students had attempted suicide during that same period.6 I wonder how many of those students exhibited telling behaviors that went unnoticed.

What are these subtle signs that are so easily overlooked? Behaviors most might consider “within the norm” of today’s youth—hours playing video games, sending hundreds of texts every day, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep. Research has demonstrated that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the incidence of depression in adolescents.7 A 2014 study of European teens published in World Psychiatry found that the adolescents most at risk for symptoms of depression and anxiety are those who are fixated on media, don’t get enough sleep, and have a sedentary lifestyle.8 Hmm... sounds like many US teenagers today. While that doesn’t mean that every teen who lacks sleep, plays video games, or isn’t active is at risk, we do need to pay closer attention to them, because this combination exacerbates risk.

There’s another unhealthy habit that contributes to the risk for teen suicidality: smoking and use of electronic vapor products (EVPs). The 2015 YRBS, which surveyed more than 15,000 high school students, noted that 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users. Analysis of that data identified associations between health-risk behaviors and both cigarette smoking and EVP use.9 Teens who smoked or used EVPs were more likely to engage in violence, substance abuse, and other high-risk behaviors, compared with nonusers. Moreover, compared with nonusers, cigarette-only, EVP-only, and dual smokers were significantly more likely to attempt suicide; cigarette-only smokers were more likely than EVP-only users to attempt suicide.9

Smoking, inactivity, sleep deprivation, and social isolation (because texting or face-timing with your friends is not being social) are a recipe for depression and anxiety in an adolescent. Sleep deprivation alone has been linked to depression and may be associated with a decreased ability to control, inhibit, or change emotional responses.10 Far too often, teens view suicide as the only relief from these feelings.

Awareness of this problem has grown in the past 30 years. The YRBS was developed in 1990 to monitor priority health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death, disability, and social problems among youth in the US—one of which is suicide.11 In 2001, the Department of Health and Human Services introduced the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, the first national program of its kind, and released an evidence-based practice guide for school-based suicide prevention plans.12 The 2002 Institute of Medicine report Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative recognized the need for early recognition and prevention of suicidality.13 And yet, we still have the staggering statistics I cited earlier.

Because of their proximity to children and adolescents, schools are frequently viewed as an integral setting for youth suicide prevention efforts. It is encouraging that suicide prevention programs exist in more than 77% of US public schools—but disheartening that it is not 100%.

And what about the rest of us? What can we, as health care providers, do to stem this tide of teen suicide? The importance of early prevention strategies to reduce onset of suicidal thoughts and help identify persons who are at risk for or are currently contemplating suicide cannot be overemphasized. We need more health care practitioners who are trained to assess suicide plans and to intervene with young persons. This involves education in recognizing risk factors and making appropriate referrals, expanding access to social services, reducing stigma and other barriers to seeking help, and providing awareness that suicide prevention is paramount.

It is incumbent on us as health care providers to screen for and ask our teenaged patients about those subtle behaviors. As adults, it is our responsibility to support and watch over our youth. In the words of former Surgeon General David Satcher, “We must act now. We cannot change the past, but together we can shape a different future.”14

The incidence of high-risk behavior among teenagers has attracted increased media attention lately. It feels like a new report surfaces every day detailing the death of one or more teens as a result of alcohol, illicit drug use, or speeding. These risky behaviors grab our attention; they are overt and somewhat public. But behaviors that correlate with anxiety and depression, which can in turn lead to suicide or suicidal ideation, are more subtle—and that is what concerns me.

The data on suicide is staggering. On a daily basis, almost 3,000 people worldwide complete suicide, and approximately 20 times as many survive a suicide attempt.1 Annually, deaths resulting from suicide exceed deaths from homicide and war combined.2 In 2013, there were 41,149 suicides in the US—that translates to a rate of 113 suicides each day, or one every 13 minutes.3 Suicide has surpassed homicide to become the second leading cause of death among 10- to 29-year-olds; in 2012, suicide claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people within this age bracket.4,5 In the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 17.7% of high school students reported seriously considering suicide during the prior 12 months, and nearly 9% of those students had attempted suicide during that same period.6 I wonder how many of those students exhibited telling behaviors that went unnoticed.

What are these subtle signs that are so easily overlooked? Behaviors most might consider “within the norm” of today’s youth—hours playing video games, sending hundreds of texts every day, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep. Research has demonstrated that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces the incidence of depression in adolescents.7 A 2014 study of European teens published in World Psychiatry found that the adolescents most at risk for symptoms of depression and anxiety are those who are fixated on media, don’t get enough sleep, and have a sedentary lifestyle.8 Hmm... sounds like many US teenagers today. While that doesn’t mean that every teen who lacks sleep, plays video games, or isn’t active is at risk, we do need to pay closer attention to them, because this combination exacerbates risk.

There’s another unhealthy habit that contributes to the risk for teen suicidality: smoking and use of electronic vapor products (EVPs). The 2015 YRBS, which surveyed more than 15,000 high school students, noted that 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users. Analysis of that data identified associations between health-risk behaviors and both cigarette smoking and EVP use.9 Teens who smoked or used EVPs were more likely to engage in violence, substance abuse, and other high-risk behaviors, compared with nonusers. Moreover, compared with nonusers, cigarette-only, EVP-only, and dual smokers were significantly more likely to attempt suicide; cigarette-only smokers were more likely than EVP-only users to attempt suicide.9

Smoking, inactivity, sleep deprivation, and social isolation (because texting or face-timing with your friends is not being social) are a recipe for depression and anxiety in an adolescent. Sleep deprivation alone has been linked to depression and may be associated with a decreased ability to control, inhibit, or change emotional responses.10 Far too often, teens view suicide as the only relief from these feelings.

Awareness of this problem has grown in the past 30 years. The YRBS was developed in 1990 to monitor priority health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death, disability, and social problems among youth in the US—one of which is suicide.11 In 2001, the Department of Health and Human Services introduced the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, the first national program of its kind, and released an evidence-based practice guide for school-based suicide prevention plans.12 The 2002 Institute of Medicine report Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative recognized the need for early recognition and prevention of suicidality.13 And yet, we still have the staggering statistics I cited earlier.

Because of their proximity to children and adolescents, schools are frequently viewed as an integral setting for youth suicide prevention efforts. It is encouraging that suicide prevention programs exist in more than 77% of US public schools—but disheartening that it is not 100%.

And what about the rest of us? What can we, as health care providers, do to stem this tide of teen suicide? The importance of early prevention strategies to reduce onset of suicidal thoughts and help identify persons who are at risk for or are currently contemplating suicide cannot be overemphasized. We need more health care practitioners who are trained to assess suicide plans and to intervene with young persons. This involves education in recognizing risk factors and making appropriate referrals, expanding access to social services, reducing stigma and other barriers to seeking help, and providing awareness that suicide prevention is paramount.

It is incumbent on us as health care providers to screen for and ask our teenaged patients about those subtle behaviors. As adults, it is our responsibility to support and watch over our youth. In the words of former Surgeon General David Satcher, “We must act now. We cannot change the past, but together we can shape a different future.”14

1. World Health Organization. World Suicide Prevention Day. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s16/en/. Accessed February 2, 2017

2. World Health Organization. Suicide huge but preventable public health problem, says WHO. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr61/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

3. CDC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed February 2, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Suicide. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

5. CDC. Suicide trends among persons aged 10-24 years—United States, 1994-2012. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6408.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

6. CDC. Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behavior. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991-2013. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

7. Zahl T, Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and symptoms of major depression in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161711.

8. Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):78-86.

9. Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, King BA. Adolescent risk behaviors and use of electronic vapor products and cigarettes. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162921.

10. National Sleep Foundation. Adolescent sleep needs and patterns. https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/sleep_and_teens_report1.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

11. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) overview. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm. Accessed February 2, 2017.

12. Cooper GD, Clements PT, Holt K. A review and application of suicide prevention programs in high school settings. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(11):696-702.

13. Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2002.

14. US Public Health Service. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC: 1999.

1. World Health Organization. World Suicide Prevention Day. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s16/en/. Accessed February 2, 2017

2. World Health Organization. Suicide huge but preventable public health problem, says WHO. www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr61/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

3. CDC. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed February 2, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Suicide. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en. Accessed February 2, 2017.

5. CDC. Suicide trends among persons aged 10-24 years—United States, 1994-2012. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6408.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

6. CDC. Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behavior. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991-2013. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

7. Zahl T, Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and symptoms of major depression in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20161711.

8. Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, et al. A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):78-86.

9. Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, King BA. Adolescent risk behaviors and use of electronic vapor products and cigarettes. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162921.

10. National Sleep Foundation. Adolescent sleep needs and patterns. https://sleepfoundation.org/sites/default/files/sleep_and_teens_report1.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

11. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) overview. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/overview.htm. Accessed February 2, 2017.

12. Cooper GD, Clements PT, Holt K. A review and application of suicide prevention programs in high school settings. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(11):696-702.

13. Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2002.

14. US Public Health Service. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. Washington, DC: 1999.

Ecofriendly surfactant is allergen of the year

ORLANDO – Alkyl glucosides, mild surfactants derived from natural, sustainable sources, have been named allergen of the year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

The ecofriendly nature of these compounds has led to their inclusion in more personal care products in the last decade and a half. Alkyl glucosides are derived from coconut, palm, or rapeseed oil with glucose supplied by corn, wheat starch, or potatoes. They can be found in rinse-off products such as shampoos, shower gels, and liquid cleansers but also in leave-on products such as deodorants, sunscreens, and moisturizers, investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society, held just prior to the start of the American Academy of Dermatology’s annual meeting.

Camille Loranger, MD, of the department of dermatology, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, presented her institution’s experience with allergic contact dermatitis caused by alkyl glucosides. A total of 3,095 patients were patch tested at the clinic between January 2009 and June 2016. Researchers used the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 65-allergen series, which includes decyl glucoside (5% in petrolatum). Slightly more than half of patients (1,628) also were tested for reactions to lauryl glucoside (3% in petrolatum) as part of an additional cosmetic series. Twenty patients in the larger series reacted to decyl glucoside, while 15 of those who tested for lauryl glucoside reacted. Of those 15 patients, 6 were found to be allergic to decyl glucoside as well (Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28[1]:5-13).

Allergy to alkyl glucosides became more common over time in the McGill series. The rate of positivity was low in the early years of the series, but increased from 1.37% of 437 patients in 2014 to 2.2% of 227 patients tested in the first half of 2016, Dr. Loranger said.

“Most of our patients were women with an average age of 48 years,” she added. “Body sites most commonly affected were the head and the hands. Only one case could be attributed to occupational exposure.”

Most patients – 86% – also were atopic (asthma, eczema, and rhinitis).

Products identified as most commonly causing a positive reaction were leave-on moisturizers and hand creams.

Donald V. Belsito, MD, professor of dermatology at Columbia University, N.Y., introduced the allergen of the year, pointing out that the compounds selected are not necessarily “bad actors.”

“The allergen of the year is really chosen to educate dermatologists about allergens that may be of low prevalence but a high relevance,” Dr. Belsito said. The allergens selected “are difficult to test for because they are tested for at irritant concentrations. It doesn’t mean they are these horrible substances that are damaging the world necessarily.”

The ACDS has been naming an allergen of the year since 2004.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

ORLANDO – Alkyl glucosides, mild surfactants derived from natural, sustainable sources, have been named allergen of the year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

The ecofriendly nature of these compounds has led to their inclusion in more personal care products in the last decade and a half. Alkyl glucosides are derived from coconut, palm, or rapeseed oil with glucose supplied by corn, wheat starch, or potatoes. They can be found in rinse-off products such as shampoos, shower gels, and liquid cleansers but also in leave-on products such as deodorants, sunscreens, and moisturizers, investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society, held just prior to the start of the American Academy of Dermatology’s annual meeting.

Camille Loranger, MD, of the department of dermatology, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, presented her institution’s experience with allergic contact dermatitis caused by alkyl glucosides. A total of 3,095 patients were patch tested at the clinic between January 2009 and June 2016. Researchers used the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 65-allergen series, which includes decyl glucoside (5% in petrolatum). Slightly more than half of patients (1,628) also were tested for reactions to lauryl glucoside (3% in petrolatum) as part of an additional cosmetic series. Twenty patients in the larger series reacted to decyl glucoside, while 15 of those who tested for lauryl glucoside reacted. Of those 15 patients, 6 were found to be allergic to decyl glucoside as well (Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28[1]:5-13).

Allergy to alkyl glucosides became more common over time in the McGill series. The rate of positivity was low in the early years of the series, but increased from 1.37% of 437 patients in 2014 to 2.2% of 227 patients tested in the first half of 2016, Dr. Loranger said.

“Most of our patients were women with an average age of 48 years,” she added. “Body sites most commonly affected were the head and the hands. Only one case could be attributed to occupational exposure.”

Most patients – 86% – also were atopic (asthma, eczema, and rhinitis).

Products identified as most commonly causing a positive reaction were leave-on moisturizers and hand creams.

Donald V. Belsito, MD, professor of dermatology at Columbia University, N.Y., introduced the allergen of the year, pointing out that the compounds selected are not necessarily “bad actors.”

“The allergen of the year is really chosen to educate dermatologists about allergens that may be of low prevalence but a high relevance,” Dr. Belsito said. The allergens selected “are difficult to test for because they are tested for at irritant concentrations. It doesn’t mean they are these horrible substances that are damaging the world necessarily.”

The ACDS has been naming an allergen of the year since 2004.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

ORLANDO – Alkyl glucosides, mild surfactants derived from natural, sustainable sources, have been named allergen of the year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

The ecofriendly nature of these compounds has led to their inclusion in more personal care products in the last decade and a half. Alkyl glucosides are derived from coconut, palm, or rapeseed oil with glucose supplied by corn, wheat starch, or potatoes. They can be found in rinse-off products such as shampoos, shower gels, and liquid cleansers but also in leave-on products such as deodorants, sunscreens, and moisturizers, investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society, held just prior to the start of the American Academy of Dermatology’s annual meeting.

Camille Loranger, MD, of the department of dermatology, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, presented her institution’s experience with allergic contact dermatitis caused by alkyl glucosides. A total of 3,095 patients were patch tested at the clinic between January 2009 and June 2016. Researchers used the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 65-allergen series, which includes decyl glucoside (5% in petrolatum). Slightly more than half of patients (1,628) also were tested for reactions to lauryl glucoside (3% in petrolatum) as part of an additional cosmetic series. Twenty patients in the larger series reacted to decyl glucoside, while 15 of those who tested for lauryl glucoside reacted. Of those 15 patients, 6 were found to be allergic to decyl glucoside as well (Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28[1]:5-13).

Allergy to alkyl glucosides became more common over time in the McGill series. The rate of positivity was low in the early years of the series, but increased from 1.37% of 437 patients in 2014 to 2.2% of 227 patients tested in the first half of 2016, Dr. Loranger said.

“Most of our patients were women with an average age of 48 years,” she added. “Body sites most commonly affected were the head and the hands. Only one case could be attributed to occupational exposure.”

Most patients – 86% – also were atopic (asthma, eczema, and rhinitis).

Products identified as most commonly causing a positive reaction were leave-on moisturizers and hand creams.

Donald V. Belsito, MD, professor of dermatology at Columbia University, N.Y., introduced the allergen of the year, pointing out that the compounds selected are not necessarily “bad actors.”

“The allergen of the year is really chosen to educate dermatologists about allergens that may be of low prevalence but a high relevance,” Dr. Belsito said. The allergens selected “are difficult to test for because they are tested for at irritant concentrations. It doesn’t mean they are these horrible substances that are damaging the world necessarily.”

The ACDS has been naming an allergen of the year since 2004.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

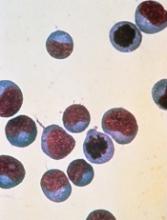

CAR designers report high B-cell cancer response rates

ORLANDO – Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies of B-cell lineage had robust immune responses following infusion of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T-cell construct designed to deliver a specific balance of antigens, investigators reported.

Adults with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute myeloid leukemia (ALL), non–Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received a CAR-T cell construct consisting of autologous CD4-positive and CD-8-positive T cells that were transduced separately, recombined, and then delivered in a single infusion had comparatively high overall response and complete response rates, reported Cameron Turtle, MBBS, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“We know that patients have a highly variable CD4 to CD8 ratio, so by actually controlling this and separately transducing, expanding, and then reformulating in this defined composition, we’re able to eliminate one source of variability in CAR-T cell products,” Dr. Turtle said at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

In preclinical studies, an even balance of CD4-positive and CD8-positive central memory T cells or naive T cells evoked more potent immune responses against B-cell malignancies in mice than CD19-positive cells, he explained

To see whether this would also hold true in humans, the investigators enrolled into a phase I/II trial adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, including ALL (36 patients), NHL (41), and CLL (24). No patients were excluded on the basis of either absolute lymphocyte, circulating tumors cells, history of stem cell transplant, or results of in vitro test expansions.

All patients underwent leukapheresis for harvesting of T-cells, and populations of CD4- and CD8-positive cells were separated and transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a CD19 CAR and a truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor that allowed tracing of the transduced cells via flow cytometry. The patients underwent lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (for the earliest patients), or cyclophosphamide plus fludarabine. Fifteen days after leukapheresis, the separated, transduced, and expanded cells were combined and delivered back to patients in a single infusion at one of three dose levels: 2 x 105, 2 x 106, or 2 x 107 CAR-T cells/kg.

ALL results

Two of the 36 patients with ALL died from complications of the CAR-T cell infusion process prior to evaluation. The 34 remaining patients all had morphologic bone marrow complete responses (CR). Of this group, 32 also had bone marrow CR on flow cytometry.

Using immunoglobulin H (IgH) deep sequencing in a subset of 20 patients 3 weeks after CAR-T cell infusion, the investigators could not detect the malignant IgH index clone in 13 of the patients, and found fewer than 10 copies in the bone marrow of 5 patients.

Six of seven patients with extramedullary disease at baseline had a complete response. The remaining patient in this group had an equivocal PET scan result, and experienced a relapse 2 months after assessment.

The investigators also determined that the lymphodepletion regimen may affect overall results, based on the finding that 10 of 12 patients who received cyclophosphamide alone achieved a CR, but seven of these 10 patients had a relapse within a few months. Of these seven patients. five received a second T-cell infusion, but none had significant T-cell expansion. The investigators traced the failure of the second attempt to a CD8-mediated transgene immune response to a murine single-chain variable fragment used in the construct.

For subsequent patients, they altered the lymphodepletion regimen to include fludarabine to prevent priming of the anti-CAR transgenic immune response. This modification resulted in improved progression-free survival and overall survival for subsequent patients receiving a second infusion, Dr. Turtle said.

NHL results

Of the 41 patients with NHL, 30 (73%) had aggressive histologies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell, and Burkitt lymphomas, and 11 (27%) had indolent histologies, including mantle cell and follicular lymphomas. Most of the patients had received multiple prior lines of therapy, and 19 (46%) had undergone either an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Of the 39 evaluable patients who completed therapy, the overall response rate was 67%, including 13 (39%) with CR. Dr. Turtle noted that the CR rate was substantially higher among patients who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepletion, compared with cyclophosphamide alone.

There were also a few responses, including two CRs, among patients with indolent histologies, he said.

CLL, safety results

All 24 patients with CLL had previously received ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Of this group, 19 either had no significant responses to the drug, inactivating mutations, or intolerable toxicities. All but 1 of the 24 patients also had high-risk cytogenetics.

Of the 16 ibrutinib-refractory patients who were evaluable for restaging, 14 had no evidence of disease in bone marrow by flow cytometry at 4 weeks. The overall response rate in this group was 69%, which included four CRs.

Among a majority of all patients, toxicity with the CAR-T cell therapy was mild to moderate. Early cytokine changes appeared to be predictive of serious adverse events such as the cytokine release syndrome, a finding that may allow clinicians to intervene early to prevent complications, Dr. Turtle said.

In the CAR-T cell therapy, “multiple things affect the response and toxicity, including CAR T-cell dose, disease burden, the anti-CAR transgene immune response and the lymphodepletion regimen, not to mention other patient factors that we’re still sorting out,” he commented.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

ORLANDO – Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies of B-cell lineage had robust immune responses following infusion of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T-cell construct designed to deliver a specific balance of antigens, investigators reported.

Adults with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute myeloid leukemia (ALL), non–Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received a CAR-T cell construct consisting of autologous CD4-positive and CD-8-positive T cells that were transduced separately, recombined, and then delivered in a single infusion had comparatively high overall response and complete response rates, reported Cameron Turtle, MBBS, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“We know that patients have a highly variable CD4 to CD8 ratio, so by actually controlling this and separately transducing, expanding, and then reformulating in this defined composition, we’re able to eliminate one source of variability in CAR-T cell products,” Dr. Turtle said at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

In preclinical studies, an even balance of CD4-positive and CD8-positive central memory T cells or naive T cells evoked more potent immune responses against B-cell malignancies in mice than CD19-positive cells, he explained

To see whether this would also hold true in humans, the investigators enrolled into a phase I/II trial adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, including ALL (36 patients), NHL (41), and CLL (24). No patients were excluded on the basis of either absolute lymphocyte, circulating tumors cells, history of stem cell transplant, or results of in vitro test expansions.

All patients underwent leukapheresis for harvesting of T-cells, and populations of CD4- and CD8-positive cells were separated and transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a CD19 CAR and a truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor that allowed tracing of the transduced cells via flow cytometry. The patients underwent lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (for the earliest patients), or cyclophosphamide plus fludarabine. Fifteen days after leukapheresis, the separated, transduced, and expanded cells were combined and delivered back to patients in a single infusion at one of three dose levels: 2 x 105, 2 x 106, or 2 x 107 CAR-T cells/kg.

ALL results

Two of the 36 patients with ALL died from complications of the CAR-T cell infusion process prior to evaluation. The 34 remaining patients all had morphologic bone marrow complete responses (CR). Of this group, 32 also had bone marrow CR on flow cytometry.

Using immunoglobulin H (IgH) deep sequencing in a subset of 20 patients 3 weeks after CAR-T cell infusion, the investigators could not detect the malignant IgH index clone in 13 of the patients, and found fewer than 10 copies in the bone marrow of 5 patients.

Six of seven patients with extramedullary disease at baseline had a complete response. The remaining patient in this group had an equivocal PET scan result, and experienced a relapse 2 months after assessment.

The investigators also determined that the lymphodepletion regimen may affect overall results, based on the finding that 10 of 12 patients who received cyclophosphamide alone achieved a CR, but seven of these 10 patients had a relapse within a few months. Of these seven patients. five received a second T-cell infusion, but none had significant T-cell expansion. The investigators traced the failure of the second attempt to a CD8-mediated transgene immune response to a murine single-chain variable fragment used in the construct.

For subsequent patients, they altered the lymphodepletion regimen to include fludarabine to prevent priming of the anti-CAR transgenic immune response. This modification resulted in improved progression-free survival and overall survival for subsequent patients receiving a second infusion, Dr. Turtle said.

NHL results

Of the 41 patients with NHL, 30 (73%) had aggressive histologies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell, and Burkitt lymphomas, and 11 (27%) had indolent histologies, including mantle cell and follicular lymphomas. Most of the patients had received multiple prior lines of therapy, and 19 (46%) had undergone either an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Of the 39 evaluable patients who completed therapy, the overall response rate was 67%, including 13 (39%) with CR. Dr. Turtle noted that the CR rate was substantially higher among patients who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepletion, compared with cyclophosphamide alone.

There were also a few responses, including two CRs, among patients with indolent histologies, he said.

CLL, safety results

All 24 patients with CLL had previously received ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Of this group, 19 either had no significant responses to the drug, inactivating mutations, or intolerable toxicities. All but 1 of the 24 patients also had high-risk cytogenetics.

Of the 16 ibrutinib-refractory patients who were evaluable for restaging, 14 had no evidence of disease in bone marrow by flow cytometry at 4 weeks. The overall response rate in this group was 69%, which included four CRs.

Among a majority of all patients, toxicity with the CAR-T cell therapy was mild to moderate. Early cytokine changes appeared to be predictive of serious adverse events such as the cytokine release syndrome, a finding that may allow clinicians to intervene early to prevent complications, Dr. Turtle said.

In the CAR-T cell therapy, “multiple things affect the response and toxicity, including CAR T-cell dose, disease burden, the anti-CAR transgene immune response and the lymphodepletion regimen, not to mention other patient factors that we’re still sorting out,” he commented.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

ORLANDO – Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies of B-cell lineage had robust immune responses following infusion of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–T-cell construct designed to deliver a specific balance of antigens, investigators reported.

Adults with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute myeloid leukemia (ALL), non–Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received a CAR-T cell construct consisting of autologous CD4-positive and CD-8-positive T cells that were transduced separately, recombined, and then delivered in a single infusion had comparatively high overall response and complete response rates, reported Cameron Turtle, MBBS, PhD, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

“We know that patients have a highly variable CD4 to CD8 ratio, so by actually controlling this and separately transducing, expanding, and then reformulating in this defined composition, we’re able to eliminate one source of variability in CAR-T cell products,” Dr. Turtle said at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

In preclinical studies, an even balance of CD4-positive and CD8-positive central memory T cells or naive T cells evoked more potent immune responses against B-cell malignancies in mice than CD19-positive cells, he explained

To see whether this would also hold true in humans, the investigators enrolled into a phase I/II trial adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, including ALL (36 patients), NHL (41), and CLL (24). No patients were excluded on the basis of either absolute lymphocyte, circulating tumors cells, history of stem cell transplant, or results of in vitro test expansions.

All patients underwent leukapheresis for harvesting of T-cells, and populations of CD4- and CD8-positive cells were separated and transduced with a lentiviral vector to express a CD19 CAR and a truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor that allowed tracing of the transduced cells via flow cytometry. The patients underwent lymphodepleting chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide (for the earliest patients), or cyclophosphamide plus fludarabine. Fifteen days after leukapheresis, the separated, transduced, and expanded cells were combined and delivered back to patients in a single infusion at one of three dose levels: 2 x 105, 2 x 106, or 2 x 107 CAR-T cells/kg.

ALL results

Two of the 36 patients with ALL died from complications of the CAR-T cell infusion process prior to evaluation. The 34 remaining patients all had morphologic bone marrow complete responses (CR). Of this group, 32 also had bone marrow CR on flow cytometry.

Using immunoglobulin H (IgH) deep sequencing in a subset of 20 patients 3 weeks after CAR-T cell infusion, the investigators could not detect the malignant IgH index clone in 13 of the patients, and found fewer than 10 copies in the bone marrow of 5 patients.

Six of seven patients with extramedullary disease at baseline had a complete response. The remaining patient in this group had an equivocal PET scan result, and experienced a relapse 2 months after assessment.

The investigators also determined that the lymphodepletion regimen may affect overall results, based on the finding that 10 of 12 patients who received cyclophosphamide alone achieved a CR, but seven of these 10 patients had a relapse within a few months. Of these seven patients. five received a second T-cell infusion, but none had significant T-cell expansion. The investigators traced the failure of the second attempt to a CD8-mediated transgene immune response to a murine single-chain variable fragment used in the construct.

For subsequent patients, they altered the lymphodepletion regimen to include fludarabine to prevent priming of the anti-CAR transgenic immune response. This modification resulted in improved progression-free survival and overall survival for subsequent patients receiving a second infusion, Dr. Turtle said.

NHL results

Of the 41 patients with NHL, 30 (73%) had aggressive histologies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell, and Burkitt lymphomas, and 11 (27%) had indolent histologies, including mantle cell and follicular lymphomas. Most of the patients had received multiple prior lines of therapy, and 19 (46%) had undergone either an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Of the 39 evaluable patients who completed therapy, the overall response rate was 67%, including 13 (39%) with CR. Dr. Turtle noted that the CR rate was substantially higher among patients who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepletion, compared with cyclophosphamide alone.

There were also a few responses, including two CRs, among patients with indolent histologies, he said.

CLL, safety results

All 24 patients with CLL had previously received ibrutinib (Imbruvica). Of this group, 19 either had no significant responses to the drug, inactivating mutations, or intolerable toxicities. All but 1 of the 24 patients also had high-risk cytogenetics.

Of the 16 ibrutinib-refractory patients who were evaluable for restaging, 14 had no evidence of disease in bone marrow by flow cytometry at 4 weeks. The overall response rate in this group was 69%, which included four CRs.

Among a majority of all patients, toxicity with the CAR-T cell therapy was mild to moderate. Early cytokine changes appeared to be predictive of serious adverse events such as the cytokine release syndrome, a finding that may allow clinicians to intervene early to prevent complications, Dr. Turtle said.

In the CAR-T cell therapy, “multiple things affect the response and toxicity, including CAR T-cell dose, disease burden, the anti-CAR transgene immune response and the lymphodepletion regimen, not to mention other patient factors that we’re still sorting out,” he commented.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

AT THE CLINICAL IMMUNO-ONCOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: A defined CAR-T cell construct was associated with high response rates in patients with B-cell malignancies.

Major finding: The overall response rate among patients with ibrutinib-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia was 69%, including four complete responses.

Data source: Phase I/II dose-finding, safety and efficacy study in patients with B-lineage hematologic malignancies

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Life Science Development Fund, Juno Therapeutics and the Bezos Family Foundation. Dr. Turtle disclosed consultancy, honoraria, and/or research funding from Juno Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.

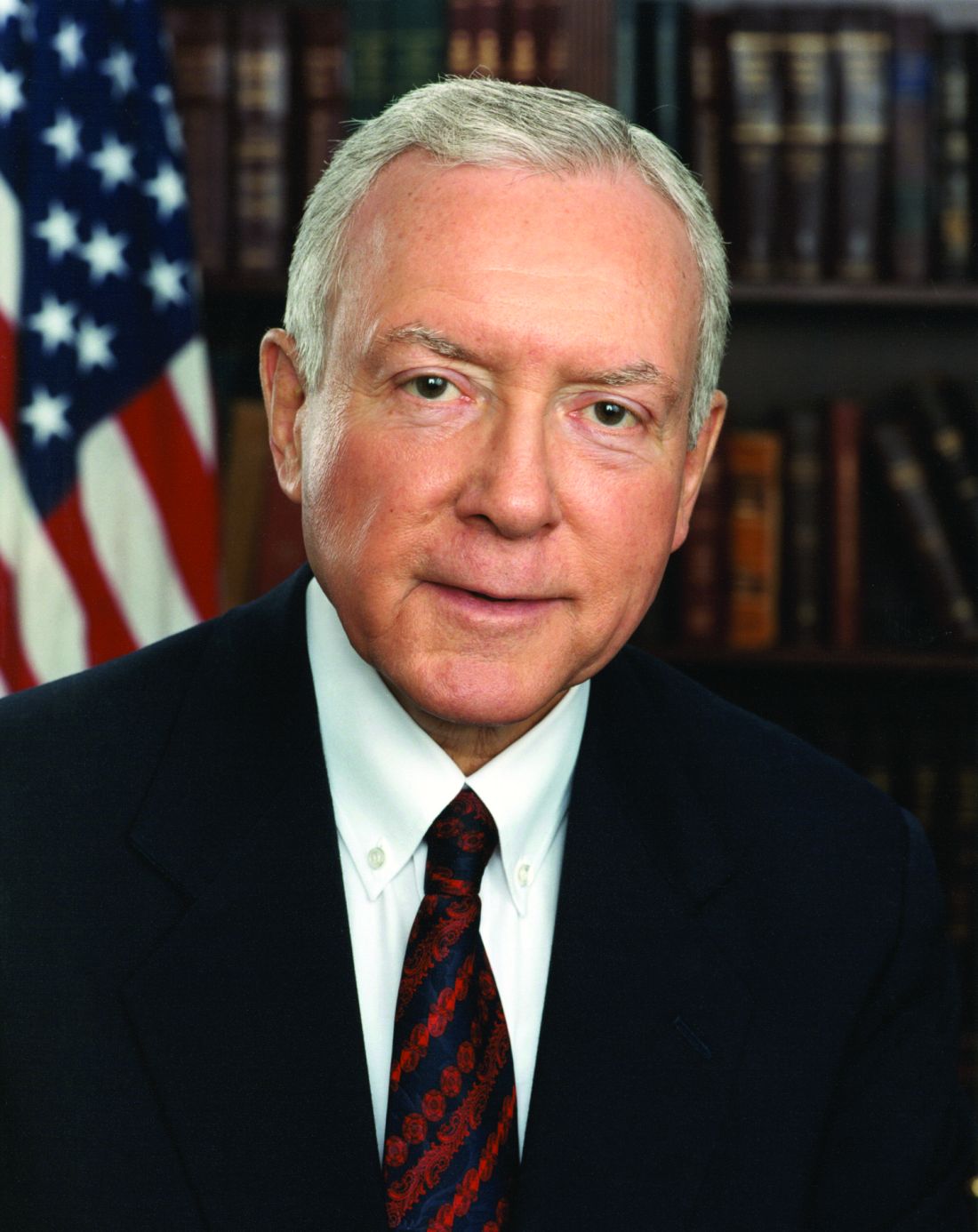

CMS nominee Verma clears Senate Finance hurdle

Seema Verma has moved one step closer to becoming the administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The Senate Finance Committee voted 13-12 on March 2 to approve Ms. Verma’s nomination after a delayed vote the day before. The vote, conducted during a meeting off the floor, was a straight party-line vote, with 13 Republicans voting for Ms. Verma and 12 Democrats voting against. One proxy vote was not counted into the final tally per Senate rules.

Her nomination will now be considered by the full Senate.

Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) praised Ms. Verma as a qualified leader who will help improve CMS.

Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Ron Wyden, (D-Ore.) denounced Ms. Verma, stressing that she failed to adequately answer questions during her nomination hearing and has presented no clear vision of her plans as the next CMS administrator.

During her nomination hearing on Feb. 16, Ms. Verma came under fire for past consulting agreements with states while working for Hewlett Packard, a company that had financial interests in the health programs she designed. The issue was raised again during a preliminary vote by the Finance Committee on March 1.

“Ms. Verma was on both sides of the deal, helping manage the state’s health programs while being paid by vendors to those same programs,” Sen. Wyden said during the hearing. “I am concerned that if Ms. Verma is confirmed to lead CMS, where many of the companies she worked for are major vendors, there will not be adequate scrutiny of her past relationships with them, just as there wasn’t in Indiana.”

Ms. Verma previously said she never negotiated on behalf of Hewlett Packard and that the work she conducted for the states did not overlap with work she completed for HP.

“I hold honesty and integrity and adherence to a high ethical standard as part of my personal philosophy. That’s for me, I demand that from my employees, and I set that example for my own children,” she said during the Feb. 16 hearing. “We were never in a position where we were negotiating on behalf of HP or any other contractor with the state that we had a relationship with. If there was the potential [for a conflict], we would recuse ourselves.”

Ms. Verma’s nomination will now move to the full Senate. No date has yet been set for the vote.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Seema Verma has moved one step closer to becoming the administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The Senate Finance Committee voted 13-12 on March 2 to approve Ms. Verma’s nomination after a delayed vote the day before. The vote, conducted during a meeting off the floor, was a straight party-line vote, with 13 Republicans voting for Ms. Verma and 12 Democrats voting against. One proxy vote was not counted into the final tally per Senate rules.