User login

Novel Solution for Massive Glenoid Defects in Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Patient-Specific Glenoid Vault Reconstruction System

Take-Home Points

- With more shoulder arthroplasties being performed on younger patients, we can expect more revisions in the future.

- Many of these revision cases will have profound glenoid bone loss.

- Bone grafting the glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty has been less successful especially with significant vault defects.

- Based on the CAD-CAM success in total hip and knee replacement surgery, a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system has been developed by Zimmer Biomet to deal with profound glenoid bone loss and cuff insufficiency.

- Early results of this vault reconstruction system have been promising in these most difficult clinical situations.

Early results of this vault reconstruction system have been promising in these most difficult clinical situations. Complex glenoid deformities present the most difficult challenges in shoulder arthroplasty (SA). These deformities may be caused by severe degenerative or congenital deformity, posttraumatic anatomy, tumor, or, in most cases, bone loss after glenoid failure in anatomical total SA.

Walch and colleagues1 described the pathologic glenoid lesions seen in progressive degenerative arthritis and some congenital defects. The most severe were initially characterized as Walch B2 and Walch C deformities. These lesions have been further classified to include Walch B3 posteroinferior glenoid deformities.2,3 Each of these deformities can result in severe glenoid vault deficiency.

In some revision cases and in severe rheumatoid cases, these deformities can present as cavitary lesions with or without failure of the glenoid rim or wall resulting in significant compromise of glenoid vault lesions.4,5 In these cases, the degree of “medialization” of the native glenohumeral joint line and the amount of peripheral bone loss can have profound effects on the amount of bone available for fixation and on the ability to allow component positioning for best surgical and biomechanical outcomes.

Other bone loss deformities, which have been described by Antuna and colleagues6 and Seebauer and colleagues,7 often accompany disease processes with severe cuff deficiency. These deformities historically have been treated with intercalary-type bone grafts in 1- or 2-stage revision of reverse SA or in salvage to hemiarthroplasty. Treatment of these pathologies with the technique described produced only fair results in short-term to midterm follow-up. The most commonly reported complications have been component loosening, bone graft failure, infection, and instability.8-11Borrowing from hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons’ experience in using CAD/CAM (computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing) patient-specific implants to fill significant bony defects, Dr. D. M. Dines and Dr. Craig developed a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system (VRS) in conjunction with the Comprehensive Shoulder Arthroplasty System (Zimmer Biomet). For a number of years, the Food and Drug Administration allowed this patient-specific glenoid VRS component to be made available only as a custom implant. Recently, however, full 510K clearance was granted to use the VRS in reverse SA patients with severe soft-tissue deficiency and significant glenoid bone loss.

In this article, we describe the implant and its indications, technical aspects of production, and surgical technique.

Vault Reconstruction System

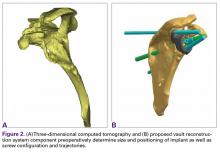

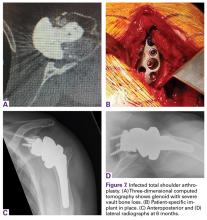

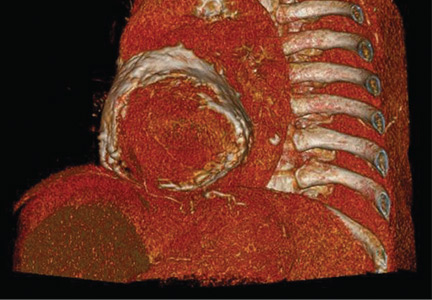

Severe glenoid bone loss often requires an implant that specifically matches the patient’s anatomy. The patient-specific glenoid VRS (Figure 1) is made from a 3-dimensional reconstruction of a 2-dimensional computed tomography image.

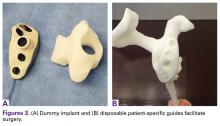

In some cases in which the bone is sufficient to enhance fixation in the deficient glenoid vault, a custom boss may be added to the implant, as well as a custom guide matching the implant.

Glenoid Exposure

In most cases of severe glenoid bone loss, the associated soft-tissue deficiency allows for easier glenoid exposure. In this implant system, however, maximal peripheral en face exposure of the glenoid is required. In addition, it is mandatory to avoid disturbing the remaining glenoid bone surfaces, which often are thin or fragile, because the patient-specific implant is referenced to this anatomy. Bone that is not maintained changes the orientation of the patient-specific guide and ultimately the fixation of the component. Using the correct retractors and meticulously excising soft-tissue scar tissue are crucial for success.

Implant Positioning

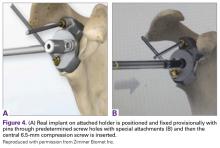

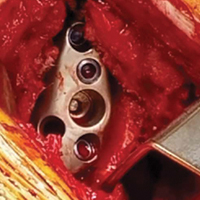

With the glenoid surface properly exposed, the removable inserter handle and the built-in lip on the implant are used to position the patient-specific guide. Next, a central guide pin is placed through the inserter for temporary fixation and further instrumentation. If enough bone is present, a boss reamer can be used over the guide pin to prepare and increase the fixation surface.

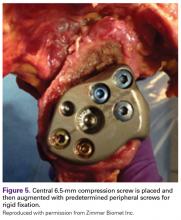

The central 6.5-mm nonlocking compression screw is placed to provide strong initial compressive fixation in best bone.

With the patient-specific glenoid VRS implant now rigidly fixed in the glenoid, the sized and offset glenosphere is properly positioned, and the reverse SA is completed in routine fashion.

Case Examples

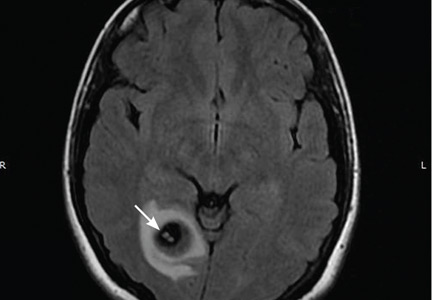

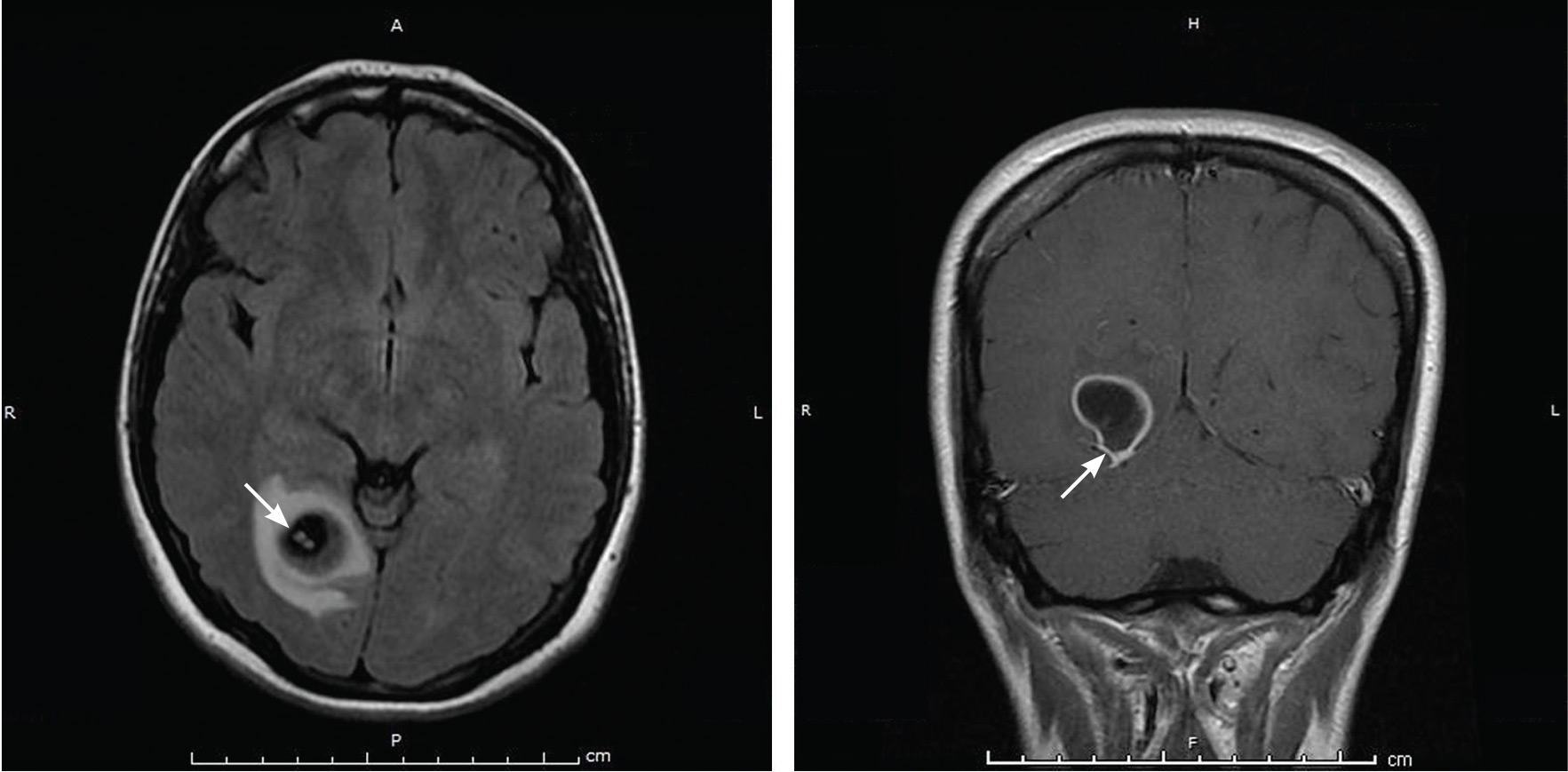

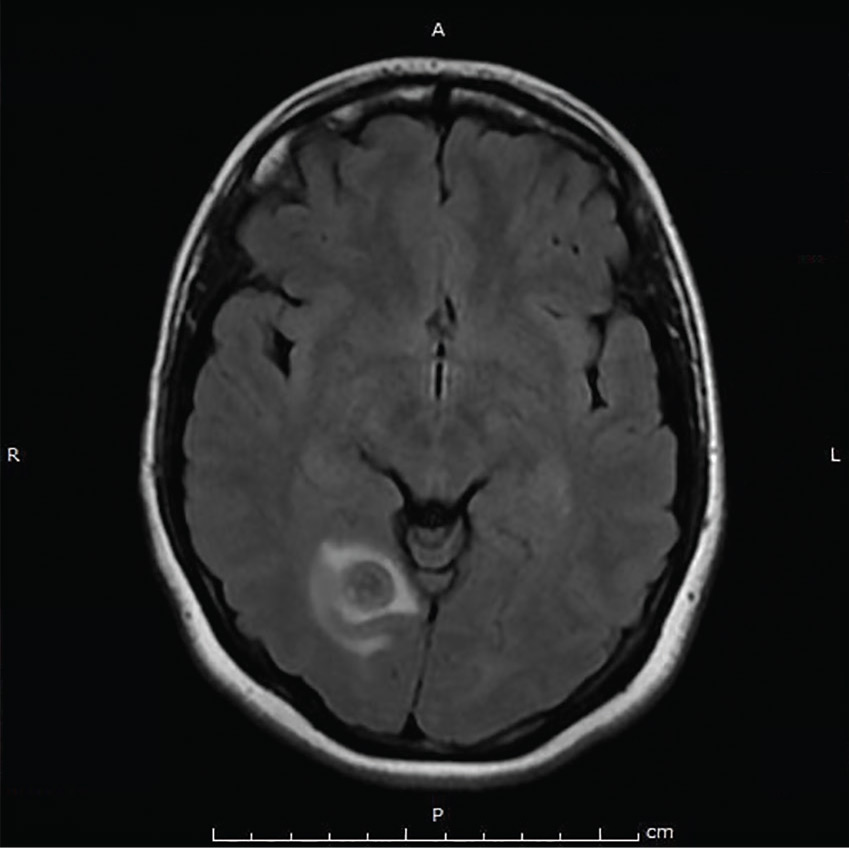

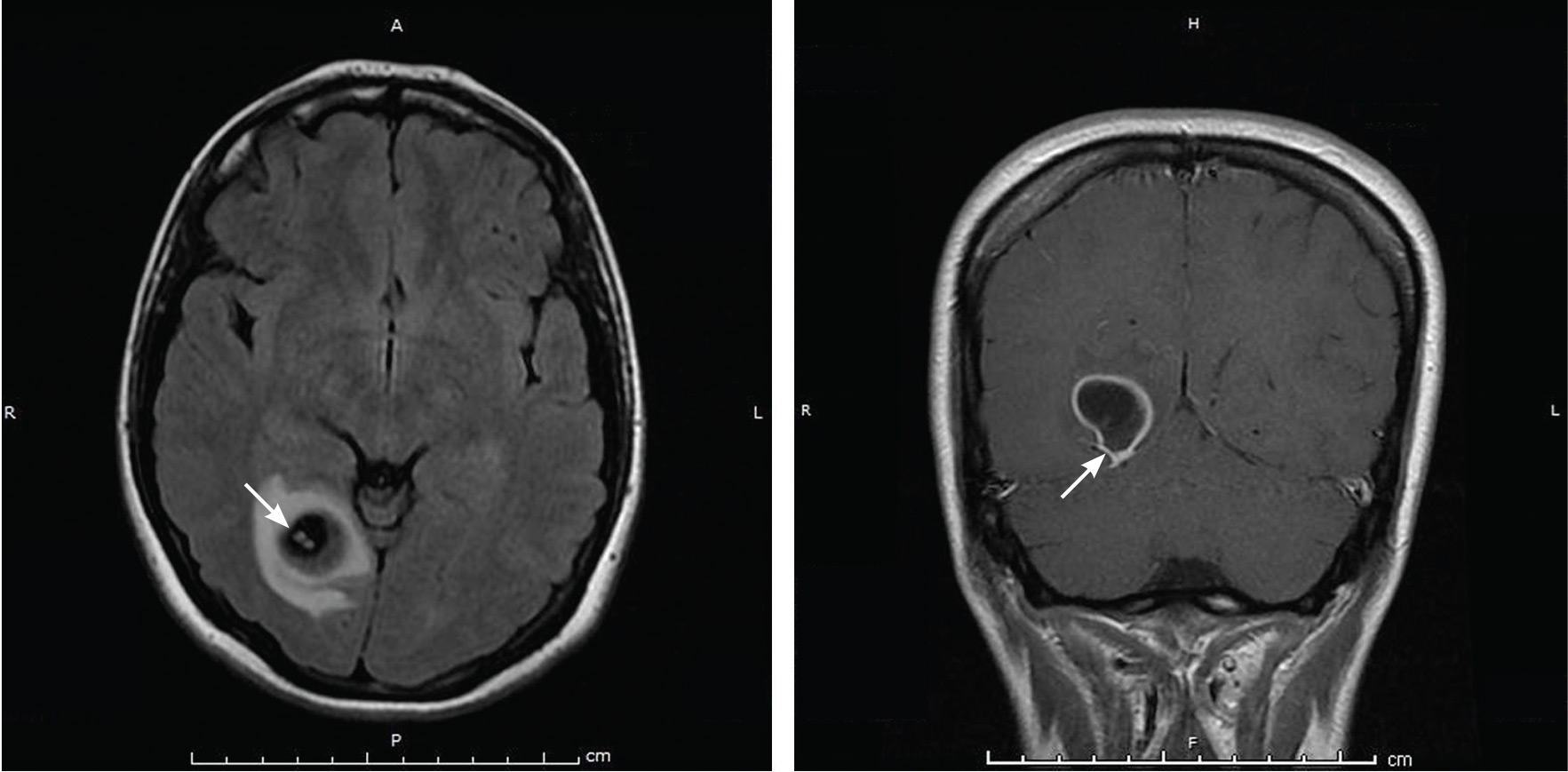

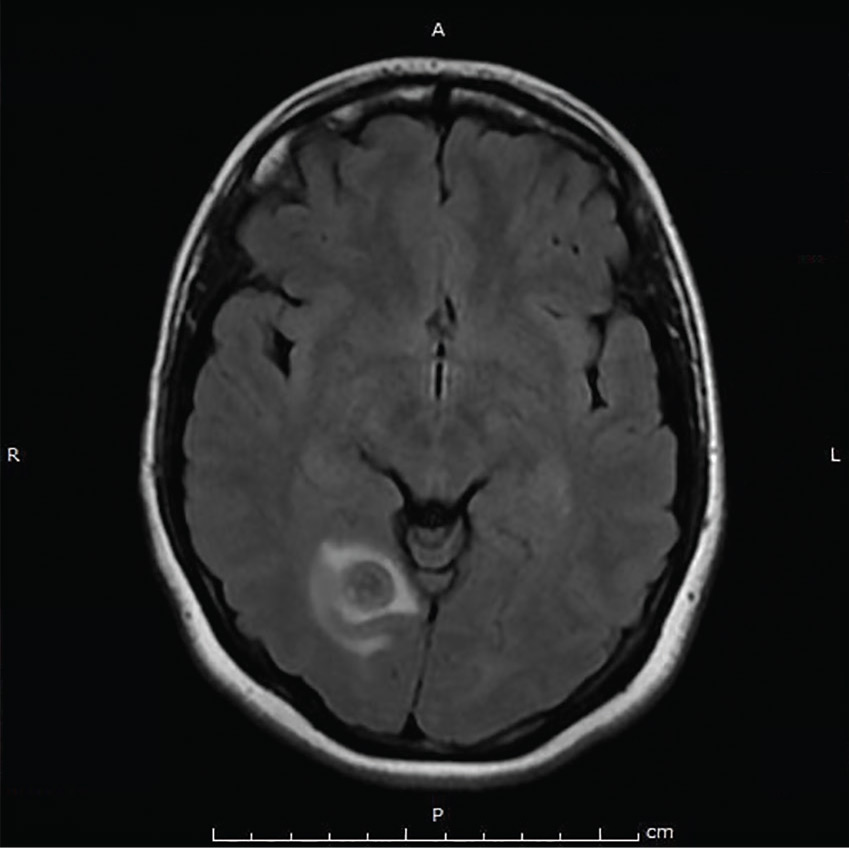

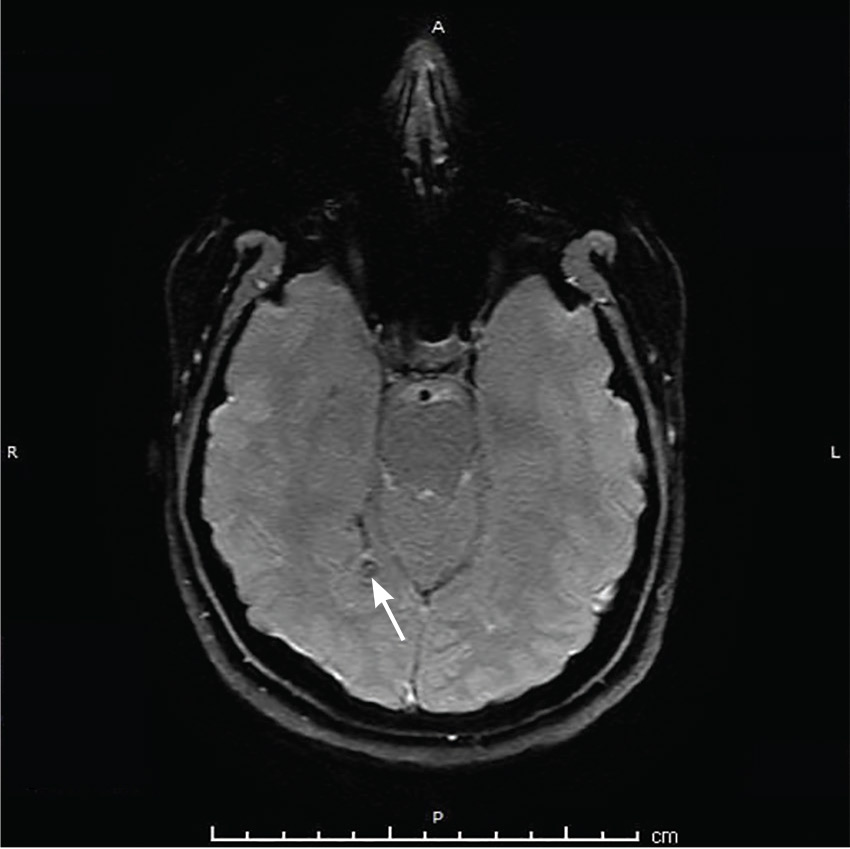

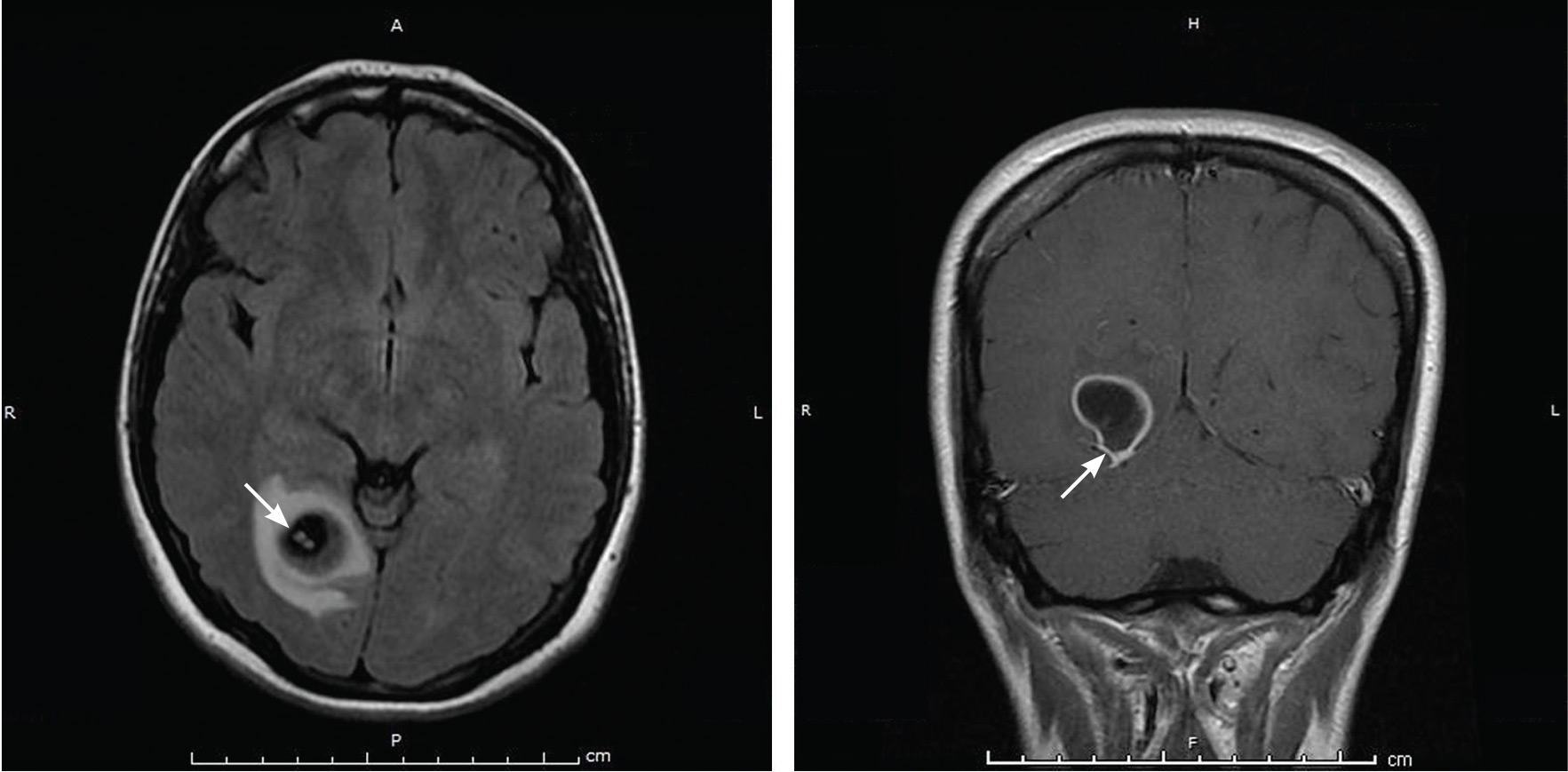

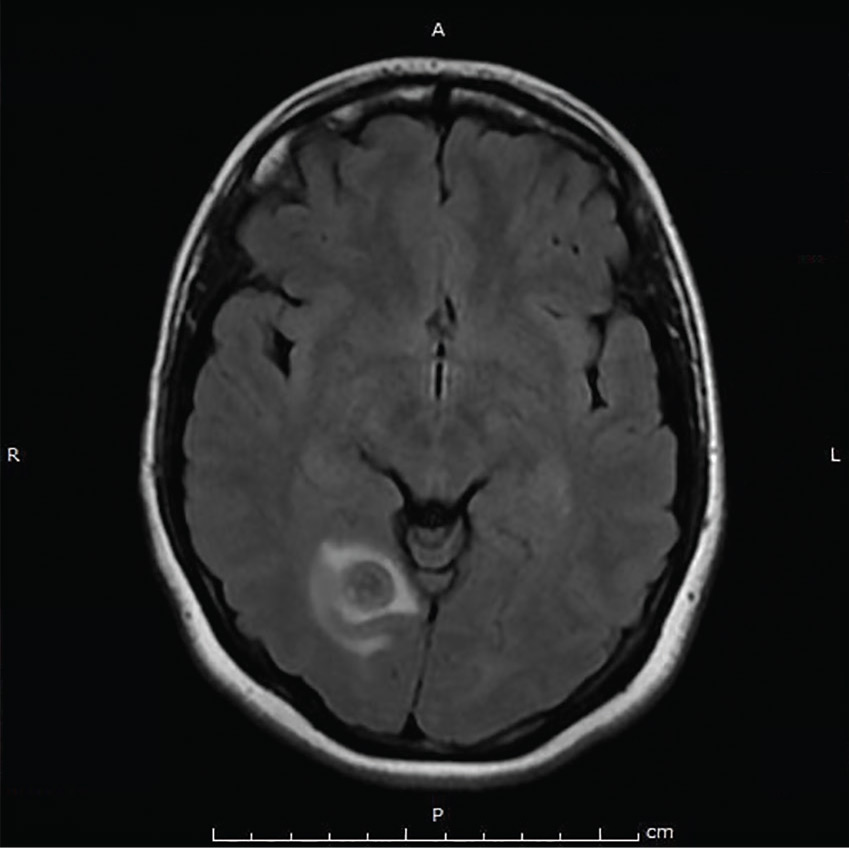

A 49-year-old man underwent hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis. The procedure failed and, 3 years later, was revised to conventional total SA. Unfortunately, the cemented all-polyethylene glenoid loosened secondary to active Propionibacterium acnes infection, which required excisional arthroplasty with antibiotic spacer. Significant cavitary bone loss was found with anterior glenoid wall bone loss compromising the glenoid vault. Given the history of bone loss and infection, patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction was performed after infection eradication. Within 4 years after this surgery, the patient had resumed all activities. At age 57 years, he had restricted active forward elevation and abduction to 120° but was satisfied with the outcome.

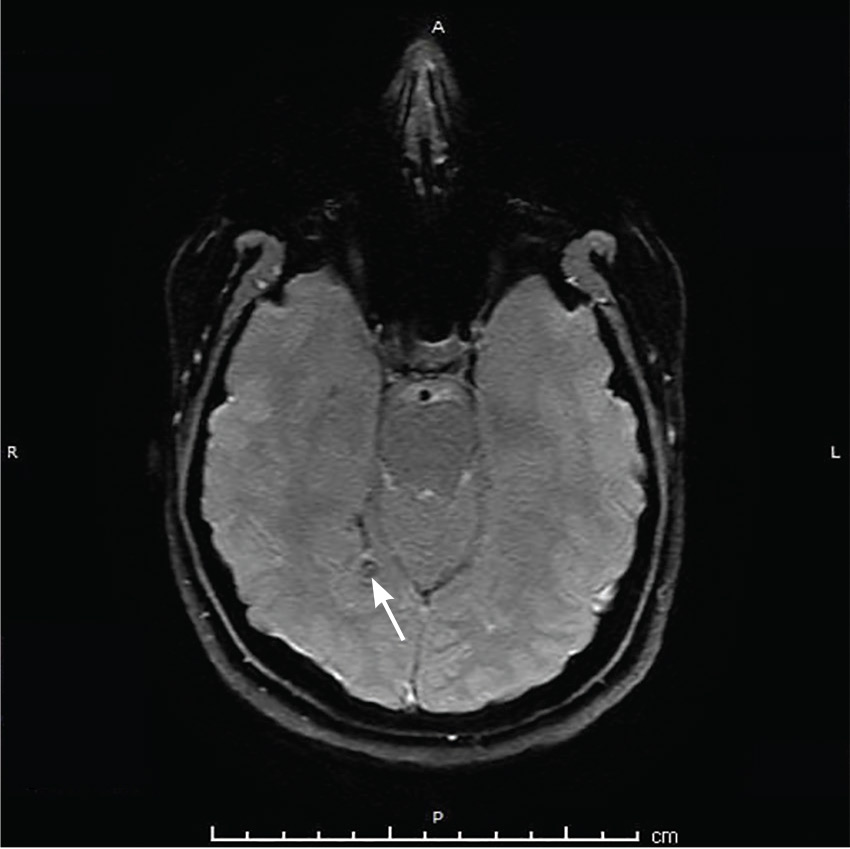

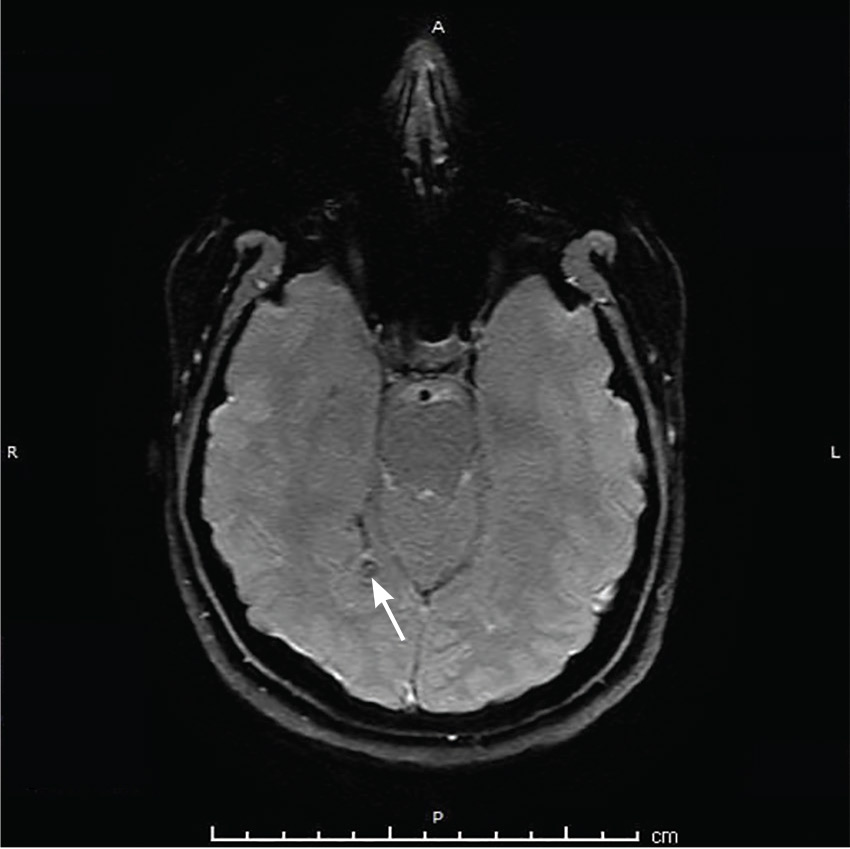

A 71-year-old man underwent reverse SA for rotator cuff-deficient osteoarthritis. After implant excision and spacer placement, he was left with severe soft-tissue deficiency and glenoid bone loss, which caused substantial disability. After treatment for infection, a work-up was performed for glenoid bone deficiency and insertion of a patient-specific glenoid VRS implant.

Discussion

Glenoid bone deformity and deficiency are among the most difficult challenges in SA—a particularly compelling fact given the increasing number of SAs being performed in younger, more active patients. SA surgeons can now expect to be performing even more revisions with concomitant bone defects, which may be severe in some cases.

In addition to these causes of extreme bone loss, recent awareness of the importance of recognizing and treating bone deficits in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, and instability has led to the development of patient-specific guides, instrumentation, and implants. Concepts from the use of CAD/CAM acetabular implants in total hip arthroplasty for severe acetabular bony defects were applied to the use of patient-specific glenoid reconstruction implants without bone graft augmentation.12 In different form, this idea was reported by Chammaa and colleagues13 in 30 cases, and clinical and durable results were very promising.

We have described use of this technique in 2 extreme cases of glenoid vault deficiency. In each case, short-term results were quite satisfactory. However, both patients were relatively young, and long-term clinical and radiographic follow-up is needed.

Many of the severe cases of glenoid bone loss require an implant that specifically matches the patient’s anatomy. The glenoid VRS implant described here may be of great benefit in these difficult reconstructions and is a valuable addition to the armamentarium of treatments for distorted glenoid anatomy. Eventually, the idea may become useful in treating other, less significant defects by re-creating more-normal biomechanics in SA without bone graft.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

2. Chan K, Knowles NK, Chaoui J, et al. Characterization of the Walch B3 glenoid in primary osteoarthritis [published online January 11, 2017]. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.003.

3. Bercik MJ, Kruse K 2nd, Yalizis M, Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. A modification to the Walch classification of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis using three-dimensional imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(10):1601-1606.

4. Sears BW, Johnston PS, Ramsay ML, Williams GR. Glenoid bone loss in primary total shoulder arthroplasty: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(9):604-613.

5. Kocsis G, Thyagarajan DS, Fairbairn KJ, Wallace WA. A new classification of glenoid bone loss to help plan the implantation of a glenoid component before revision arthroplasty of the shoulder. Bone Joint J. 2016;98(3):374-380.

6. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

7. Seebauer L, Walter W, Keyl W. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of defect arthropathy [in English, German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2005;17(1):1-24.

8. Iannotti JP, Frangiamore SJ. Fate of large structural allograft for treatment of severe uncontained glenoid bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012:21(6):765-771.

9. Hill JM, Norris TR. Long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty following bone-grafting of the glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(6):877-883.

10. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367.

11. Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR, Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymptomatic posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1298-1308.

12. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684.

13. Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):101-107.

Take-Home Points

- With more shoulder arthroplasties being performed on younger patients, we can expect more revisions in the future.

- Many of these revision cases will have profound glenoid bone loss.

- Bone grafting the glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty has been less successful especially with significant vault defects.

- Based on the CAD-CAM success in total hip and knee replacement surgery, a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system has been developed by Zimmer Biomet to deal with profound glenoid bone loss and cuff insufficiency.

- Early results of this vault reconstruction system have been promising in these most difficult clinical situations.

Early results of this vault reconstruction system have been promising in these most difficult clinical situations. Complex glenoid deformities present the most difficult challenges in shoulder arthroplasty (SA). These deformities may be caused by severe degenerative or congenital deformity, posttraumatic anatomy, tumor, or, in most cases, bone loss after glenoid failure in anatomical total SA.

Walch and colleagues1 described the pathologic glenoid lesions seen in progressive degenerative arthritis and some congenital defects. The most severe were initially characterized as Walch B2 and Walch C deformities. These lesions have been further classified to include Walch B3 posteroinferior glenoid deformities.2,3 Each of these deformities can result in severe glenoid vault deficiency.

In some revision cases and in severe rheumatoid cases, these deformities can present as cavitary lesions with or without failure of the glenoid rim or wall resulting in significant compromise of glenoid vault lesions.4,5 In these cases, the degree of “medialization” of the native glenohumeral joint line and the amount of peripheral bone loss can have profound effects on the amount of bone available for fixation and on the ability to allow component positioning for best surgical and biomechanical outcomes.

Other bone loss deformities, which have been described by Antuna and colleagues6 and Seebauer and colleagues,7 often accompany disease processes with severe cuff deficiency. These deformities historically have been treated with intercalary-type bone grafts in 1- or 2-stage revision of reverse SA or in salvage to hemiarthroplasty. Treatment of these pathologies with the technique described produced only fair results in short-term to midterm follow-up. The most commonly reported complications have been component loosening, bone graft failure, infection, and instability.8-11Borrowing from hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons’ experience in using CAD/CAM (computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing) patient-specific implants to fill significant bony defects, Dr. D. M. Dines and Dr. Craig developed a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system (VRS) in conjunction with the Comprehensive Shoulder Arthroplasty System (Zimmer Biomet). For a number of years, the Food and Drug Administration allowed this patient-specific glenoid VRS component to be made available only as a custom implant. Recently, however, full 510K clearance was granted to use the VRS in reverse SA patients with severe soft-tissue deficiency and significant glenoid bone loss.

In this article, we describe the implant and its indications, technical aspects of production, and surgical technique.

Vault Reconstruction System

Severe glenoid bone loss often requires an implant that specifically matches the patient’s anatomy. The patient-specific glenoid VRS (Figure 1) is made from a 3-dimensional reconstruction of a 2-dimensional computed tomography image.

In some cases in which the bone is sufficient to enhance fixation in the deficient glenoid vault, a custom boss may be added to the implant, as well as a custom guide matching the implant.

Glenoid Exposure

In most cases of severe glenoid bone loss, the associated soft-tissue deficiency allows for easier glenoid exposure. In this implant system, however, maximal peripheral en face exposure of the glenoid is required. In addition, it is mandatory to avoid disturbing the remaining glenoid bone surfaces, which often are thin or fragile, because the patient-specific implant is referenced to this anatomy. Bone that is not maintained changes the orientation of the patient-specific guide and ultimately the fixation of the component. Using the correct retractors and meticulously excising soft-tissue scar tissue are crucial for success.

Implant Positioning

With the glenoid surface properly exposed, the removable inserter handle and the built-in lip on the implant are used to position the patient-specific guide. Next, a central guide pin is placed through the inserter for temporary fixation and further instrumentation. If enough bone is present, a boss reamer can be used over the guide pin to prepare and increase the fixation surface.

The central 6.5-mm nonlocking compression screw is placed to provide strong initial compressive fixation in best bone.

With the patient-specific glenoid VRS implant now rigidly fixed in the glenoid, the sized and offset glenosphere is properly positioned, and the reverse SA is completed in routine fashion.

Case Examples

A 49-year-old man underwent hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis. The procedure failed and, 3 years later, was revised to conventional total SA. Unfortunately, the cemented all-polyethylene glenoid loosened secondary to active Propionibacterium acnes infection, which required excisional arthroplasty with antibiotic spacer. Significant cavitary bone loss was found with anterior glenoid wall bone loss compromising the glenoid vault. Given the history of bone loss and infection, patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction was performed after infection eradication. Within 4 years after this surgery, the patient had resumed all activities. At age 57 years, he had restricted active forward elevation and abduction to 120° but was satisfied with the outcome.

A 71-year-old man underwent reverse SA for rotator cuff-deficient osteoarthritis. After implant excision and spacer placement, he was left with severe soft-tissue deficiency and glenoid bone loss, which caused substantial disability. After treatment for infection, a work-up was performed for glenoid bone deficiency and insertion of a patient-specific glenoid VRS implant.

Discussion

Glenoid bone deformity and deficiency are among the most difficult challenges in SA—a particularly compelling fact given the increasing number of SAs being performed in younger, more active patients. SA surgeons can now expect to be performing even more revisions with concomitant bone defects, which may be severe in some cases.

In addition to these causes of extreme bone loss, recent awareness of the importance of recognizing and treating bone deficits in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, and instability has led to the development of patient-specific guides, instrumentation, and implants. Concepts from the use of CAD/CAM acetabular implants in total hip arthroplasty for severe acetabular bony defects were applied to the use of patient-specific glenoid reconstruction implants without bone graft augmentation.12 In different form, this idea was reported by Chammaa and colleagues13 in 30 cases, and clinical and durable results were very promising.

We have described use of this technique in 2 extreme cases of glenoid vault deficiency. In each case, short-term results were quite satisfactory. However, both patients were relatively young, and long-term clinical and radiographic follow-up is needed.

Many of the severe cases of glenoid bone loss require an implant that specifically matches the patient’s anatomy. The glenoid VRS implant described here may be of great benefit in these difficult reconstructions and is a valuable addition to the armamentarium of treatments for distorted glenoid anatomy. Eventually, the idea may become useful in treating other, less significant defects by re-creating more-normal biomechanics in SA without bone graft.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- With more shoulder arthroplasties being performed on younger patients, we can expect more revisions in the future.

- Many of these revision cases will have profound glenoid bone loss.

- Bone grafting the glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty has been less successful especially with significant vault defects.

- Based on the CAD-CAM success in total hip and knee replacement surgery, a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system has been developed by Zimmer Biomet to deal with profound glenoid bone loss and cuff insufficiency.

- Early results of this vault reconstruction system have been promising in these most difficult clinical situations.

Early results of this vault reconstruction system have been promising in these most difficult clinical situations. Complex glenoid deformities present the most difficult challenges in shoulder arthroplasty (SA). These deformities may be caused by severe degenerative or congenital deformity, posttraumatic anatomy, tumor, or, in most cases, bone loss after glenoid failure in anatomical total SA.

Walch and colleagues1 described the pathologic glenoid lesions seen in progressive degenerative arthritis and some congenital defects. The most severe were initially characterized as Walch B2 and Walch C deformities. These lesions have been further classified to include Walch B3 posteroinferior glenoid deformities.2,3 Each of these deformities can result in severe glenoid vault deficiency.

In some revision cases and in severe rheumatoid cases, these deformities can present as cavitary lesions with or without failure of the glenoid rim or wall resulting in significant compromise of glenoid vault lesions.4,5 In these cases, the degree of “medialization” of the native glenohumeral joint line and the amount of peripheral bone loss can have profound effects on the amount of bone available for fixation and on the ability to allow component positioning for best surgical and biomechanical outcomes.

Other bone loss deformities, which have been described by Antuna and colleagues6 and Seebauer and colleagues,7 often accompany disease processes with severe cuff deficiency. These deformities historically have been treated with intercalary-type bone grafts in 1- or 2-stage revision of reverse SA or in salvage to hemiarthroplasty. Treatment of these pathologies with the technique described produced only fair results in short-term to midterm follow-up. The most commonly reported complications have been component loosening, bone graft failure, infection, and instability.8-11Borrowing from hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons’ experience in using CAD/CAM (computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing) patient-specific implants to fill significant bony defects, Dr. D. M. Dines and Dr. Craig developed a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system (VRS) in conjunction with the Comprehensive Shoulder Arthroplasty System (Zimmer Biomet). For a number of years, the Food and Drug Administration allowed this patient-specific glenoid VRS component to be made available only as a custom implant. Recently, however, full 510K clearance was granted to use the VRS in reverse SA patients with severe soft-tissue deficiency and significant glenoid bone loss.

In this article, we describe the implant and its indications, technical aspects of production, and surgical technique.

Vault Reconstruction System

Severe glenoid bone loss often requires an implant that specifically matches the patient’s anatomy. The patient-specific glenoid VRS (Figure 1) is made from a 3-dimensional reconstruction of a 2-dimensional computed tomography image.

In some cases in which the bone is sufficient to enhance fixation in the deficient glenoid vault, a custom boss may be added to the implant, as well as a custom guide matching the implant.

Glenoid Exposure

In most cases of severe glenoid bone loss, the associated soft-tissue deficiency allows for easier glenoid exposure. In this implant system, however, maximal peripheral en face exposure of the glenoid is required. In addition, it is mandatory to avoid disturbing the remaining glenoid bone surfaces, which often are thin or fragile, because the patient-specific implant is referenced to this anatomy. Bone that is not maintained changes the orientation of the patient-specific guide and ultimately the fixation of the component. Using the correct retractors and meticulously excising soft-tissue scar tissue are crucial for success.

Implant Positioning

With the glenoid surface properly exposed, the removable inserter handle and the built-in lip on the implant are used to position the patient-specific guide. Next, a central guide pin is placed through the inserter for temporary fixation and further instrumentation. If enough bone is present, a boss reamer can be used over the guide pin to prepare and increase the fixation surface.

The central 6.5-mm nonlocking compression screw is placed to provide strong initial compressive fixation in best bone.

With the patient-specific glenoid VRS implant now rigidly fixed in the glenoid, the sized and offset glenosphere is properly positioned, and the reverse SA is completed in routine fashion.

Case Examples

A 49-year-old man underwent hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis. The procedure failed and, 3 years later, was revised to conventional total SA. Unfortunately, the cemented all-polyethylene glenoid loosened secondary to active Propionibacterium acnes infection, which required excisional arthroplasty with antibiotic spacer. Significant cavitary bone loss was found with anterior glenoid wall bone loss compromising the glenoid vault. Given the history of bone loss and infection, patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction was performed after infection eradication. Within 4 years after this surgery, the patient had resumed all activities. At age 57 years, he had restricted active forward elevation and abduction to 120° but was satisfied with the outcome.

A 71-year-old man underwent reverse SA for rotator cuff-deficient osteoarthritis. After implant excision and spacer placement, he was left with severe soft-tissue deficiency and glenoid bone loss, which caused substantial disability. After treatment for infection, a work-up was performed for glenoid bone deficiency and insertion of a patient-specific glenoid VRS implant.

Discussion

Glenoid bone deformity and deficiency are among the most difficult challenges in SA—a particularly compelling fact given the increasing number of SAs being performed in younger, more active patients. SA surgeons can now expect to be performing even more revisions with concomitant bone defects, which may be severe in some cases.

In addition to these causes of extreme bone loss, recent awareness of the importance of recognizing and treating bone deficits in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, trauma, and instability has led to the development of patient-specific guides, instrumentation, and implants. Concepts from the use of CAD/CAM acetabular implants in total hip arthroplasty for severe acetabular bony defects were applied to the use of patient-specific glenoid reconstruction implants without bone graft augmentation.12 In different form, this idea was reported by Chammaa and colleagues13 in 30 cases, and clinical and durable results were very promising.

We have described use of this technique in 2 extreme cases of glenoid vault deficiency. In each case, short-term results were quite satisfactory. However, both patients were relatively young, and long-term clinical and radiographic follow-up is needed.

Many of the severe cases of glenoid bone loss require an implant that specifically matches the patient’s anatomy. The glenoid VRS implant described here may be of great benefit in these difficult reconstructions and is a valuable addition to the armamentarium of treatments for distorted glenoid anatomy. Eventually, the idea may become useful in treating other, less significant defects by re-creating more-normal biomechanics in SA without bone graft.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

2. Chan K, Knowles NK, Chaoui J, et al. Characterization of the Walch B3 glenoid in primary osteoarthritis [published online January 11, 2017]. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.003.

3. Bercik MJ, Kruse K 2nd, Yalizis M, Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. A modification to the Walch classification of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis using three-dimensional imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(10):1601-1606.

4. Sears BW, Johnston PS, Ramsay ML, Williams GR. Glenoid bone loss in primary total shoulder arthroplasty: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(9):604-613.

5. Kocsis G, Thyagarajan DS, Fairbairn KJ, Wallace WA. A new classification of glenoid bone loss to help plan the implantation of a glenoid component before revision arthroplasty of the shoulder. Bone Joint J. 2016;98(3):374-380.

6. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

7. Seebauer L, Walter W, Keyl W. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of defect arthropathy [in English, German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2005;17(1):1-24.

8. Iannotti JP, Frangiamore SJ. Fate of large structural allograft for treatment of severe uncontained glenoid bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012:21(6):765-771.

9. Hill JM, Norris TR. Long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty following bone-grafting of the glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(6):877-883.

10. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367.

11. Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR, Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymptomatic posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1298-1308.

12. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684.

13. Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):101-107.

1. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

2. Chan K, Knowles NK, Chaoui J, et al. Characterization of the Walch B3 glenoid in primary osteoarthritis [published online January 11, 2017]. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.003.

3. Bercik MJ, Kruse K 2nd, Yalizis M, Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. A modification to the Walch classification of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis using three-dimensional imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(10):1601-1606.

4. Sears BW, Johnston PS, Ramsay ML, Williams GR. Glenoid bone loss in primary total shoulder arthroplasty: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(9):604-613.

5. Kocsis G, Thyagarajan DS, Fairbairn KJ, Wallace WA. A new classification of glenoid bone loss to help plan the implantation of a glenoid component before revision arthroplasty of the shoulder. Bone Joint J. 2016;98(3):374-380.

6. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

7. Seebauer L, Walter W, Keyl W. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of defect arthropathy [in English, German]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2005;17(1):1-24.

8. Iannotti JP, Frangiamore SJ. Fate of large structural allograft for treatment of severe uncontained glenoid bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012:21(6):765-771.

9. Hill JM, Norris TR. Long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty following bone-grafting of the glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(6):877-883.

10. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367.

11. Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR, Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymptomatic posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1298-1308.

12. Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):675-684.

13. Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(1):101-107.

High-Resolution Wireless Ultrasound

Arthrex Synergy MSK Ultrasound by Clarius(http://www.synergy-ultrasound.com/)

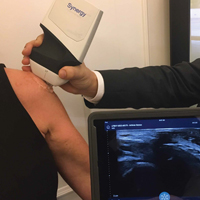

Three scanners are capable of targeting different tissue types and depths. We prefer the Synergy MSK Linear Ultrasound by Clarius, a linear transducer that can evaluate tissue to depths of 7 cm and use frequencies from 4 MHz to 13 MHz. Its battery holds a standby charge for 7 days and can be actively used for 45 minutes. The unit has a magnesium shell; with the battery removed, the unit can be completely immersed in liquid without being damaged, which allows for easy cleaning and, potentially, sterilization with a soak solution. Color Doppler (for blood-flow assessment) and proprietary advanced needle visualization technology will be available in June.

The app is simply controlled with typical smart-device gestures. Depth control requires a finger swipe, and zoom takes a pinch. Other controls, such as optimal gain and frequency settings, are automated. Images and videos can be stored on the device and uploaded either to the Clarius Cloud or to a PACS (picture archiving and communication system) device. New features will allow the device to use a Synergy arthroscopy tower (Arthrex) as its display for surgeons and anesthesiologists in the surgical suite.

This technology finally allows ultrasound to be used in the operating room without the hassles of cumbersome machines and the potential contamination by the sleeves covering the cord that connects the transducer and the base unit (Figure 1).

Recent studies have demonstrated new ultrasound-guided surgical techniques for biceps tenodesis,4 anterolateral ligament reconstruction,13 medial patellofemoral ligament repair or reconstruction,14 and medial collateral ligament internal bracing.4

This small device can also be easily used on sports fields, as it can be carried in a pocket with a smart phone or tablet. With its 10- to 15-second start-up, it is readily available and allows for immediate evaluation of a player. No longer does a player need to be taken off the field for a radiograph. The same advantage of portability means the unit is appropriate for emergency department physicians and staff.

Surgical pearl: Overall, ultrasound is an imaging technology that has improved the accuracy and efficacy of injections. Wireless capability, portability, and versatility with high-resolution images improve this modality further and extend our reach into surgical, office, hospital, and sports settings. The ease, convenience, and reasonable price of high-resolution wireless ultrasound make it an attractive tool for physicians, nursing staff, athletic trainers, and physical therapists.

1. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

2. Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Adams E, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) position statement: interventional musculoskeletal ultrasound in sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(3):145-150.

3. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

4. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

5. Kang MN, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas DA, Blacksin MF. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: a comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 suppl):61S-66S.

6. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

7. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

8. Partington PF, Broome GH. Diagnostic injection around the shoulder: hit and miss? A cadaveric study of injection accuracy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):147-150.

9. Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, de Waal Malefijt MC. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

10. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

11. Sivan M, Brown J, Brennan S, Bhakta B. A one-stop approach to the management of soft tissue and degenerative musculoskeletal conditions using clinic-based ultrasonography. Musculoskeletal Care. 2011;9(2):63-68.

12. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

13. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

14. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of the medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. In press.

Arthrex Synergy MSK Ultrasound by Clarius(http://www.synergy-ultrasound.com/)

Three scanners are capable of targeting different tissue types and depths. We prefer the Synergy MSK Linear Ultrasound by Clarius, a linear transducer that can evaluate tissue to depths of 7 cm and use frequencies from 4 MHz to 13 MHz. Its battery holds a standby charge for 7 days and can be actively used for 45 minutes. The unit has a magnesium shell; with the battery removed, the unit can be completely immersed in liquid without being damaged, which allows for easy cleaning and, potentially, sterilization with a soak solution. Color Doppler (for blood-flow assessment) and proprietary advanced needle visualization technology will be available in June.

The app is simply controlled with typical smart-device gestures. Depth control requires a finger swipe, and zoom takes a pinch. Other controls, such as optimal gain and frequency settings, are automated. Images and videos can be stored on the device and uploaded either to the Clarius Cloud or to a PACS (picture archiving and communication system) device. New features will allow the device to use a Synergy arthroscopy tower (Arthrex) as its display for surgeons and anesthesiologists in the surgical suite.

This technology finally allows ultrasound to be used in the operating room without the hassles of cumbersome machines and the potential contamination by the sleeves covering the cord that connects the transducer and the base unit (Figure 1).

Recent studies have demonstrated new ultrasound-guided surgical techniques for biceps tenodesis,4 anterolateral ligament reconstruction,13 medial patellofemoral ligament repair or reconstruction,14 and medial collateral ligament internal bracing.4

This small device can also be easily used on sports fields, as it can be carried in a pocket with a smart phone or tablet. With its 10- to 15-second start-up, it is readily available and allows for immediate evaluation of a player. No longer does a player need to be taken off the field for a radiograph. The same advantage of portability means the unit is appropriate for emergency department physicians and staff.

Surgical pearl: Overall, ultrasound is an imaging technology that has improved the accuracy and efficacy of injections. Wireless capability, portability, and versatility with high-resolution images improve this modality further and extend our reach into surgical, office, hospital, and sports settings. The ease, convenience, and reasonable price of high-resolution wireless ultrasound make it an attractive tool for physicians, nursing staff, athletic trainers, and physical therapists.

Arthrex Synergy MSK Ultrasound by Clarius(http://www.synergy-ultrasound.com/)

Three scanners are capable of targeting different tissue types and depths. We prefer the Synergy MSK Linear Ultrasound by Clarius, a linear transducer that can evaluate tissue to depths of 7 cm and use frequencies from 4 MHz to 13 MHz. Its battery holds a standby charge for 7 days and can be actively used for 45 minutes. The unit has a magnesium shell; with the battery removed, the unit can be completely immersed in liquid without being damaged, which allows for easy cleaning and, potentially, sterilization with a soak solution. Color Doppler (for blood-flow assessment) and proprietary advanced needle visualization technology will be available in June.

The app is simply controlled with typical smart-device gestures. Depth control requires a finger swipe, and zoom takes a pinch. Other controls, such as optimal gain and frequency settings, are automated. Images and videos can be stored on the device and uploaded either to the Clarius Cloud or to a PACS (picture archiving and communication system) device. New features will allow the device to use a Synergy arthroscopy tower (Arthrex) as its display for surgeons and anesthesiologists in the surgical suite.

This technology finally allows ultrasound to be used in the operating room without the hassles of cumbersome machines and the potential contamination by the sleeves covering the cord that connects the transducer and the base unit (Figure 1).

Recent studies have demonstrated new ultrasound-guided surgical techniques for biceps tenodesis,4 anterolateral ligament reconstruction,13 medial patellofemoral ligament repair or reconstruction,14 and medial collateral ligament internal bracing.4

This small device can also be easily used on sports fields, as it can be carried in a pocket with a smart phone or tablet. With its 10- to 15-second start-up, it is readily available and allows for immediate evaluation of a player. No longer does a player need to be taken off the field for a radiograph. The same advantage of portability means the unit is appropriate for emergency department physicians and staff.

Surgical pearl: Overall, ultrasound is an imaging technology that has improved the accuracy and efficacy of injections. Wireless capability, portability, and versatility with high-resolution images improve this modality further and extend our reach into surgical, office, hospital, and sports settings. The ease, convenience, and reasonable price of high-resolution wireless ultrasound make it an attractive tool for physicians, nursing staff, athletic trainers, and physical therapists.

1. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

2. Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Adams E, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) position statement: interventional musculoskeletal ultrasound in sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(3):145-150.

3. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

4. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

5. Kang MN, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas DA, Blacksin MF. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: a comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 suppl):61S-66S.

6. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

7. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

8. Partington PF, Broome GH. Diagnostic injection around the shoulder: hit and miss? A cadaveric study of injection accuracy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):147-150.

9. Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, de Waal Malefijt MC. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

10. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

11. Sivan M, Brown J, Brennan S, Bhakta B. A one-stop approach to the management of soft tissue and degenerative musculoskeletal conditions using clinic-based ultrasonography. Musculoskeletal Care. 2011;9(2):63-68.

12. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

13. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

14. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of the medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. In press.

1. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(1):59-63.

2. Finnoff JT, Hall MM, Adams E, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) position statement: interventional musculoskeletal ultrasound in sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(3):145-150.

3. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282.

4. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

5. Kang MN, Rizio L, Prybicien M, Middlemas DA, Blacksin MF. The accuracy of subacromial corticosteroid injections: a comparison of multiple methods. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1 suppl):61S-66S.

6. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind injection versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

7. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

8. Partington PF, Broome GH. Diagnostic injection around the shoulder: hit and miss? A cadaveric study of injection accuracy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(2):147-150.

9. Rutten MJ, Maresch BJ, Jager GJ, de Waal Malefijt MC. Injection of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: blind or ultrasound-guided? Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):254-257.

10. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

11. Sivan M, Brown J, Brennan S, Bhakta B. A one-stop approach to the management of soft tissue and degenerative musculoskeletal conditions using clinic-based ultrasonography. Musculoskeletal Care. 2011;9(2):63-68.

12. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

13. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

14. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of the medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. In press.

Robotic-Assisted Total Knee Arthroplasty

Stryker(http://www.stryker.com/en-us/products/Orthopaedics/MakoRobotic-ArmAssistedSurgery/index.htm)

Mako Robotic-Arm Assisted Surgery

The role of new technology in the treatment of knee arthritis is to enable accurate execution of the surgical plan for each individual’s arthritic presentation. A robotic-assisted approach allows a surgeon to perform a unicompartmental to a tricompartmental knee replacement in a consistent and reproducible manner.1

The desire is to address the technical inaccuracies (malalignment, malrotation, and soft tissue imbalance) that lead to early revisions and patient dissatisfaction.

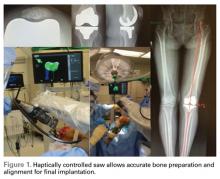

Preoperative planning utilizing a computed tomography- based approach enables the evaluation of the entire limb pathology, and aids the surgeon in“patient-matching” the implant position based on anatomic references 3-dimensionally.

Intraoperative tracking informs the surgeon on pre-resection alignment, and flexion-extension gaps. The surgeon can define a fixed vs correctable deformity, and then adjust the implant position prior to cutting, if required, while defining the desired implant and limb alignment.

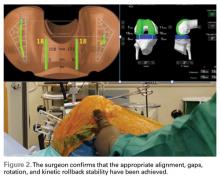

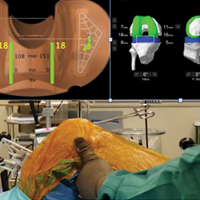

Haptically guiding the saw allows the surgeon to perform accurate bony cuts in 3 planes while protecting the soft tissues (Figure 1).

Trialing with integrated sensors allows me to evaluate the effects of the alignment and gaps on the soft tissue balance, and kinematic rollback with dynamic testing.2

The goal of robotic sensor-assisted surgery is to develop a patient specific preoperative plan, and then assist in accurate, dynamic modifications based on the patient’s limb alignment and soft tissue tension. The final implant position can be evaluated through a full range of motion (ROM), and stability defined. This information is then collected, and the effects of implant position and various limb alignment targets on soft tissue balance are evaluated as it relates to functional outcomes and patient satisfaction measurements.

Surgical pearl: Using the Mako Robotic-Arm Assisted Surgery, I performed the first robotic-assisted total knee replacement in June 2016, and have performed over 80 cases to date. Early results are showing improved accuracy, early ROM, and a decreased postoperative utilization of therapy and assistive devices. Multi-centered studies will enable the evaluation of robotic surgical approaches on short- and long-term outcomes.

1. Jacofsky DJ, Allen M. Robotics in arthroplasty: a comprehensive review. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(10):2353-2363.

2. Roche M, Elson L, Anderson C. Dynamic soft tissue balancing in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):157-165.

Stryker(http://www.stryker.com/en-us/products/Orthopaedics/MakoRobotic-ArmAssistedSurgery/index.htm)

Mako Robotic-Arm Assisted Surgery

The role of new technology in the treatment of knee arthritis is to enable accurate execution of the surgical plan for each individual’s arthritic presentation. A robotic-assisted approach allows a surgeon to perform a unicompartmental to a tricompartmental knee replacement in a consistent and reproducible manner.1

The desire is to address the technical inaccuracies (malalignment, malrotation, and soft tissue imbalance) that lead to early revisions and patient dissatisfaction.

Preoperative planning utilizing a computed tomography- based approach enables the evaluation of the entire limb pathology, and aids the surgeon in“patient-matching” the implant position based on anatomic references 3-dimensionally.

Intraoperative tracking informs the surgeon on pre-resection alignment, and flexion-extension gaps. The surgeon can define a fixed vs correctable deformity, and then adjust the implant position prior to cutting, if required, while defining the desired implant and limb alignment.

Haptically guiding the saw allows the surgeon to perform accurate bony cuts in 3 planes while protecting the soft tissues (Figure 1).

Trialing with integrated sensors allows me to evaluate the effects of the alignment and gaps on the soft tissue balance, and kinematic rollback with dynamic testing.2

The goal of robotic sensor-assisted surgery is to develop a patient specific preoperative plan, and then assist in accurate, dynamic modifications based on the patient’s limb alignment and soft tissue tension. The final implant position can be evaluated through a full range of motion (ROM), and stability defined. This information is then collected, and the effects of implant position and various limb alignment targets on soft tissue balance are evaluated as it relates to functional outcomes and patient satisfaction measurements.

Surgical pearl: Using the Mako Robotic-Arm Assisted Surgery, I performed the first robotic-assisted total knee replacement in June 2016, and have performed over 80 cases to date. Early results are showing improved accuracy, early ROM, and a decreased postoperative utilization of therapy and assistive devices. Multi-centered studies will enable the evaluation of robotic surgical approaches on short- and long-term outcomes.

Stryker(http://www.stryker.com/en-us/products/Orthopaedics/MakoRobotic-ArmAssistedSurgery/index.htm)

Mako Robotic-Arm Assisted Surgery

The role of new technology in the treatment of knee arthritis is to enable accurate execution of the surgical plan for each individual’s arthritic presentation. A robotic-assisted approach allows a surgeon to perform a unicompartmental to a tricompartmental knee replacement in a consistent and reproducible manner.1

The desire is to address the technical inaccuracies (malalignment, malrotation, and soft tissue imbalance) that lead to early revisions and patient dissatisfaction.

Preoperative planning utilizing a computed tomography- based approach enables the evaluation of the entire limb pathology, and aids the surgeon in“patient-matching” the implant position based on anatomic references 3-dimensionally.

Intraoperative tracking informs the surgeon on pre-resection alignment, and flexion-extension gaps. The surgeon can define a fixed vs correctable deformity, and then adjust the implant position prior to cutting, if required, while defining the desired implant and limb alignment.

Haptically guiding the saw allows the surgeon to perform accurate bony cuts in 3 planes while protecting the soft tissues (Figure 1).

Trialing with integrated sensors allows me to evaluate the effects of the alignment and gaps on the soft tissue balance, and kinematic rollback with dynamic testing.2

The goal of robotic sensor-assisted surgery is to develop a patient specific preoperative plan, and then assist in accurate, dynamic modifications based on the patient’s limb alignment and soft tissue tension. The final implant position can be evaluated through a full range of motion (ROM), and stability defined. This information is then collected, and the effects of implant position and various limb alignment targets on soft tissue balance are evaluated as it relates to functional outcomes and patient satisfaction measurements.

Surgical pearl: Using the Mako Robotic-Arm Assisted Surgery, I performed the first robotic-assisted total knee replacement in June 2016, and have performed over 80 cases to date. Early results are showing improved accuracy, early ROM, and a decreased postoperative utilization of therapy and assistive devices. Multi-centered studies will enable the evaluation of robotic surgical approaches on short- and long-term outcomes.

1. Jacofsky DJ, Allen M. Robotics in arthroplasty: a comprehensive review. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(10):2353-2363.

2. Roche M, Elson L, Anderson C. Dynamic soft tissue balancing in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):157-165.

1. Jacofsky DJ, Allen M. Robotics in arthroplasty: a comprehensive review. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(10):2353-2363.

2. Roche M, Elson L, Anderson C. Dynamic soft tissue balancing in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(2):157-165.

Bedbugs: Helping your patient through an infestation

Bedbugs have been unwelcome bedfellows for humans for thousands of years. An increase in pyrethroid resistance, a ban on the insecticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT), increased international travel, and increased population density in large cities have led to an exponential rise in the incidence of bedbug infestations. Physicians are often at the forefront of bedbug infestation diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis is suggested, symptomatic treatment of the patient and extermination of the pests are essential, though time-consuming, costly, and often problematic. Measures to eliminate infestation and to prevent spread include identification of the pest, early detection, patient education, and professional eradication.

BEDBUGS: A BRIEF HISTORY

The term bedbug refers to the obligate parasitic arthropod Cimex lectularius (the common bedbug) and, less commonly, its tropical cousin C hemipterus. Bedbugs have coexisted with humans for centuries, dating back to the ancient Egyptians 3,500 years ago.1 Through the mid-20th century, about 30% of US households were infested with bedbugs.2 The introduction of pesticides during World War II markedly decreased the incidence, but with increased international travel, pesticide resistance, and the banning of certain pesticides in the last decade, bedbugs have reemerged worldwide.3

BIOLOGY

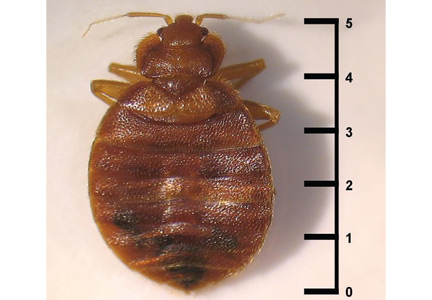

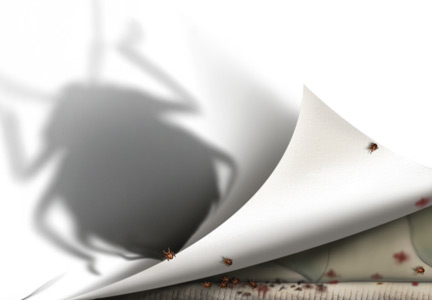

Bedbugs are red-brown, wingless, oval-shaped insects measuring 4 to 5 mm in length (Figure 1). They are hematophagous ectoparasites that preferentially feed on human blood, although they feed on some animals as well.2

Cimex lectularius dwells in temperate climates and C hemipterus in more tropical climates, but overlap and interbreeding are common. The usual life cycle is about 6 months, but some bugs live 12 months or longer. The female bedbug lays 5 to 8 eggs per week, or approximately 500 eggs in her lifetime, and each egg hatches in 5 to 10 days.4

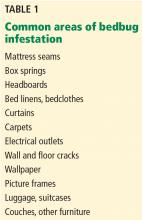

These photophobic parasites do not live on their human hosts but rather simply visit for a meal. They cohabitate in dark locations, attacking human hosts when they are inactive or sleeping for long periods of time. Common living areas include mattress seams, box springs, bed linens and clothes, wallpaper seams, electrical outlets, and furniture seams (Table 1).5 The female bedbug lays her eggs in these secluded crevices, ensuring their safety until hatching. The dense nests of adult bedbugs, their eggs, and accumulated fecal matter allow for easy visual identification of infestation.5

Bedbugs typically feed between 1:00 am and 5:00 am. Though wingless, they successfully navigate towards their human host, attracted by emitted heat and carbon dioxide.2 Once attached to human skin, the bedbug bite releases enzymes and chemicals including nitrophorin and nitric oxide that facilitate bleeding; these substances are responsible for the resultant dermatitis. (Of note, bedbugs with experimentally excised salivary glands do not cause skin disease in humans.6) After feeding for 3 to 20 minutes, the length and weight of the arthropod can increase by 50% to 200%. A fully sated bedbug can survive for a year until its next meal.2,7 Even if an establishment, home, room, or article of clothing infested with bedbugs has been abandoned for several months, without proper eradication the item still represents a possible nidus for recurrent disease if used, inhabited, or worn again.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

From the earliest documented cases of Cimex in ancient Egyptian tombs to the mid-1900s, the cohabitation of humans and bedbugs was seen as inevitable. With the introduction of DDT 60 years ago, the bedbug population significantly decreased.8 Since DDT’s prohibition, coupled with increased travel and heightened resistance to over-the-counter insecticides, the bedbug population has reemerged exponentially.9,10

Infestations have been reported worldwide, on every continent, and in all 50 of the United States. In Australia, infestations have risen 4,500% in the last 10 to 15 years.11 In the United States, infestation occurs exclusively with C lectularius and the incidence is rising. Philadelphia and New York City are among the most bedbug-infested US cities. New York City experienced a 2,000% increase in bedbug complaints between 2004 and 2009.8

Bedbugs can be transmitted either through active migration of colonies from one area to another adjacent living area through wall spaces or ventilation, or through passive transportation in luggage, clothing, furniture, used mattresses, bookbags, and other personal items.1 Although infestation affects people of all socioeconomic classes and backgrounds, the likelihood increases in people who frequently travel and people who live in lower income neighborhoods with tightly packed apartments. Bedbug infestations are also common in refugee camps: 98% of the rooms in a refugee camp in Sierra Leone had bedbugs, and almost 90% of the residents had signs of bites.12 Unlike scabies, direct person-to-person, skin-to-skin transfer is rare.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Bedbug bites are analogous, almost identical, to other arthropod bites: bites begin as pink macules that progress to papules (Figure 2), large plaques, or wheals (hives).13 Bites can arise minutes or even days after the initial assault. Some papules and plaques may have a central crust or erosion suggesting a bite.

Bites are typically intensely pruritic, and occasionally, hypersensitive victims can develop bullae, necrotic plaques, or even vasculitis. New papules and plaques form as older ones heal. Some patients may have fever and malaise.13 About 30% of patients may not have skin disease from bedbugs, making diagnosis in those individuals impossible.

The nonspecific nature of this presentation and the subsequent difficulty in prompt diagnosis can lead to a prolonged period of morbidity for the patient, as well as increasing the window of opportunity for the bedbugs to affect other surrounding individuals.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS IS BROAD

Commonly, bedbug bites have been misdiagnosed as drug eruptions, food allergies, dermatitis herpetiformis, staphylococcal or varicella infection, and scabies, as well as other arthropod bites.11 This broad differential diagnosis can often be narrowed by careful observation of the bite distribution. The clustering of bites in groups of 3, often in a linear pattern, sometimes overlying blood vessels, is known as the “breakfast, lunch, and dinner” sign (Figure 3), and this can help to guide the clinician toward the diagnosis of a bite as opposed to a diffuse urticarial response.2

If the characteristic clusters of bites are not present, distinguishing clinically between the various causes of pruritic urticarial lesions is difficult. Subtle clues that point towards bedbug bites can be that the rash appears to be most edematous in the morning and flattens throughout the day, as the bites occur typically during sleep.14 Likewise, the rash associated with bedbug bites has also been reported to last longer, to blanch less, and to be less responsive to steroid and antihistamine treatment than other urticarial rashes.14 If a skin biopsy specimen is available, histologic assessment can help to rule out similarly presenting conditions such as prodromal bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, and urticarial dermatosis, even if it cannot provide a definitive answer as to the etiology.15

Bedbug bites vs other arthropod bites

Once a bite is suspected, differentiating between bedbug and other arthropod bites is the next challenge.

Once again, a detailed assessment of the location of the bites can yield valuable information. The waist, axillae, and uncovered parts of the body are the usual sites for bedbug bites.2 Likewise, inflammatory papules along the eyelid (the “eyelid sign”) are highly suggestive of a bedbug bite.16

The scant involvement of covered body areas, the lack of shallow burrows in the skin, and the lack of scabetic elements on skin scrapings exclude scabies as a diagnosis.

Skin biopsy is not helpful in differentiating arthropod bites, as the histologic findings are nonspecific. The key to a definitive diagnosis in these cases is identification of the suspected bug in characteristic locations. Patients should be encouraged to carefully inspect mattresses, floorboards, and other crevices for the small ovaloid bugs or the reddish-brown specks of heme and feces they typically leave behind on bed linens.15 A positive reported sighting of the bugs can lend credence to the diagnosis, whereas capture and laboratory assessment of a specimen is ideal.

BEDBUGS AS DISEASE VECTORS

Extracutaneous manifestations of bedbug assault are rare. Anaphylaxis to proteins in Cimex saliva may occur, as well as significant blood loss, even anemia, from extensive feeding.17 Bedbug infestations can exacerbate asthma, preexisting mental illness, anxiety, and insomnia.18 Since bedbugs extract blood from hosts, they have a putative ability to act as vectors of disease. Some 45 known pathogens have been isolated from the Cimex species including hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Trypanosoma cruzi, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. To date, however, there is no evidence to demonstrate transmission of pathogens to humans.5

TREATMENT AND ERADICATION

Treatment is mainly symptomatic—systemic antihistamines and topical corticosteroids to reduce pruritus and alleviate the dermatitis.2 Patients should be instructed to avoid scratching to prevent infection. Secondary bacterial infection can be treated with topical or systemic antibiotics. Rare cases of bite-induced asthma or anaphylaxis necessitate appropriate emergency treatment. Extermination of infestation is critical to therapy.

If bedbug infestation is suggested, mattresses, bedding, sleeping areas, and bed clothing should be inspected for insects, eggs, and fecal spotting. Adhesives or traps that emit heat or carbon dioxide can be used to capture the bedbugs. During widespread infestation, the arthropods release a pungent odor, which allows trained dogs to detect them with 95% to 98% accuracy.19

Eradication techniques

Once infestation is confirmed, patients should contact an exterminator who can confirm the presence of bedbugs. Typical eradication measures often require nonchemical control and chemical pesticides.

Professional exterminators have special equipment that can heat a room to 48 to 50°C (118–122°F). Heat sustained at this temperature for 90 minutes is sufficient to kill bedbugs.20

The infested area should be vacuumed daily, and vacuum bags and unwanted items should be sealed in plastic before discarding. Clothing, linens, and infested fabrics should be washed and dried in heat at 60°C (140°F) or greater.

Mattresses and furniture should be sealed in a special plastic that allows treatment with heat, steaming, or pesticides. Most professional pesticides contain pyrethroids, but resistance to these products is common, necessitating the use of multiple formulations to overcome resistance.8

Over-the-counter pesticides, almost exclusively pyrethroids, are variably effective and potentially hazardous to consumers.8 Patients must be advised to follow label directions to avoid adverse effects and toxicity.

Alternative chemical eradication methods to circumvent the problem of resistance include piperonyl butoxide, S-methoprene, boric acid, silicates (diatomaceous earth dust), and sulfuryl fluoride. Recent research has also posited the use of antiparasitic agents such as ivermectin and moxidectin in cases of resistant bedbug infestation, with promising results.21

All extermination products and techniques have variable risks, efficacies, and costs,8 and repeat inspections and retreatment are often required.

Prevention strategies include visual inspection of possibly infested rooms, with particular attention to mattress seams and crevices, placing luggage on a luggage rack away from the floor and bed, and careful examination of acquired second-hand items.7

Educating patients is the key to success

While all of the above eradication techniques are important curative strategies, the success of any treatment is contingent on appropriate patient education about the nature of the problem.

Resolving a bedbug infestation is notoriously difficult and requires meticulous adherence to hygiene and cleansing instructions throughout the household or institution for a sustained period of time. Information from sources such as the US Environmental Protection Agency (www.epa.gov) can empower patients to perform the necessary eradication protocols, and clinicians should routinely recommended them as part of a holistic treatment strategy.

- Krause-Parello CA, Sciscione P. Bedbugs: an equal opportunist and cosmopolitan creature. J Sch Nurs 2009; 25:126–132.

- Sfeir M, Munoz-Price LS. Scabies and bedbugs in hospital outbreaks. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2014; 16:412.

- Romero A, Potter MF, Potter DA, Haynes KF. Insecticide resistance in the bed bug: a factor in the pest's sudden resurgence? J Med Entomol 2007; 44:175–178.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:200–210.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, Russell RC. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; 25:164–192.

- Goddard J, Edwards KT. Effects of bed bug saliva on human skin. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149:372–373.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA 2009; 301:1358–1366.

- Davies TG, Field LM, Williamson MS. The re-emergence of the bed bug as a nuisance pest: implications of resistance to the pyrethroid insecticides. Med Vet Entomol 2012; 26:241–254.

- Saenz VL, Booth W, Schal C, Vargo EL. Genetic analysis of bed bug populations reveals small propagule size within individual infestations but high genetic diversity across infestations from the eastern United States. J Med Entomol 2012; 49:865–875.

- Jones SC, Bryant JL. Ineffectiveness of over-the-counter total-release foggers against the bed bug (Heteroptera: cimicidae). J Econ Entomol 2012; 105:957–963.

- Doggett SL, Russell R. Bed bugs—what the GP needs to know. Aust Fam Physician 2009; 38:880–884.

- Gbakima AA, Terry BC, Kanja F, Kortequee S, Dukuley I, Sahr F. High prevalence of bedbugs Cimex hemipterus and Cimex lectularis in camps for internally displaced persons in Freetown, Sierra Leone: a pilot humanitarian investigation. West Afr J Med 2002; 21:268–271.

- deShazo RD, Feldlaufer MF, Mihm MC Jr, Goddard J. Bullous reactions to bedbug bites reflect cutaneous vasculitis. Am J Med 2012; 125:688–694.

- Scarupa MD, Economides A. Bedbug bites masquerading as urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117:1508–1509.

- Thomas I, Kihiczak GG, Schwartz RA. Bedbug bites: a review. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:430–433.

- Quach KA, Zaenglein AL. The eyelid sign: a clue to bed bug bites. Pediatr Dermatol 2014; 31:353–355.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Szell M, Laferl H, Auer H, Wenisch C. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res 2012; 110:2577–2579.

- Goddard J, de Shazo R. Psychological effects of bed bug attacks (Cimex lectularius L). Am J Med 2012; 125:101–103.

- Pfiester M, Koehler PG, Pereira RM. Ability of bed bug-detecting canines to locate live bed bugs and viable bed bug eggs. J Econ Entomol 2008; 101:1389–1396.

- Kells SA, Goblirsch MJ. Temperature and time requirements for controlling bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) under commercial heat treatment conditions. Insects 2011; 2:412–422.

- Sheele JM, Ridge GE. Toxicity and potential utility of ivermectin and moxidectin as xenointoxicants against the common bed bug Cimex lectularius L. Parasitol Res 2016; 115:3071–3081.

Bedbugs have been unwelcome bedfellows for humans for thousands of years. An increase in pyrethroid resistance, a ban on the insecticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT), increased international travel, and increased population density in large cities have led to an exponential rise in the incidence of bedbug infestations. Physicians are often at the forefront of bedbug infestation diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis is suggested, symptomatic treatment of the patient and extermination of the pests are essential, though time-consuming, costly, and often problematic. Measures to eliminate infestation and to prevent spread include identification of the pest, early detection, patient education, and professional eradication.

BEDBUGS: A BRIEF HISTORY

The term bedbug refers to the obligate parasitic arthropod Cimex lectularius (the common bedbug) and, less commonly, its tropical cousin C hemipterus. Bedbugs have coexisted with humans for centuries, dating back to the ancient Egyptians 3,500 years ago.1 Through the mid-20th century, about 30% of US households were infested with bedbugs.2 The introduction of pesticides during World War II markedly decreased the incidence, but with increased international travel, pesticide resistance, and the banning of certain pesticides in the last decade, bedbugs have reemerged worldwide.3

BIOLOGY

Bedbugs are red-brown, wingless, oval-shaped insects measuring 4 to 5 mm in length (Figure 1). They are hematophagous ectoparasites that preferentially feed on human blood, although they feed on some animals as well.2

Cimex lectularius dwells in temperate climates and C hemipterus in more tropical climates, but overlap and interbreeding are common. The usual life cycle is about 6 months, but some bugs live 12 months or longer. The female bedbug lays 5 to 8 eggs per week, or approximately 500 eggs in her lifetime, and each egg hatches in 5 to 10 days.4

These photophobic parasites do not live on their human hosts but rather simply visit for a meal. They cohabitate in dark locations, attacking human hosts when they are inactive or sleeping for long periods of time. Common living areas include mattress seams, box springs, bed linens and clothes, wallpaper seams, electrical outlets, and furniture seams (Table 1).5 The female bedbug lays her eggs in these secluded crevices, ensuring their safety until hatching. The dense nests of adult bedbugs, their eggs, and accumulated fecal matter allow for easy visual identification of infestation.5

Bedbugs typically feed between 1:00 am and 5:00 am. Though wingless, they successfully navigate towards their human host, attracted by emitted heat and carbon dioxide.2 Once attached to human skin, the bedbug bite releases enzymes and chemicals including nitrophorin and nitric oxide that facilitate bleeding; these substances are responsible for the resultant dermatitis. (Of note, bedbugs with experimentally excised salivary glands do not cause skin disease in humans.6) After feeding for 3 to 20 minutes, the length and weight of the arthropod can increase by 50% to 200%. A fully sated bedbug can survive for a year until its next meal.2,7 Even if an establishment, home, room, or article of clothing infested with bedbugs has been abandoned for several months, without proper eradication the item still represents a possible nidus for recurrent disease if used, inhabited, or worn again.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

From the earliest documented cases of Cimex in ancient Egyptian tombs to the mid-1900s, the cohabitation of humans and bedbugs was seen as inevitable. With the introduction of DDT 60 years ago, the bedbug population significantly decreased.8 Since DDT’s prohibition, coupled with increased travel and heightened resistance to over-the-counter insecticides, the bedbug population has reemerged exponentially.9,10

Infestations have been reported worldwide, on every continent, and in all 50 of the United States. In Australia, infestations have risen 4,500% in the last 10 to 15 years.11 In the United States, infestation occurs exclusively with C lectularius and the incidence is rising. Philadelphia and New York City are among the most bedbug-infested US cities. New York City experienced a 2,000% increase in bedbug complaints between 2004 and 2009.8

Bedbugs can be transmitted either through active migration of colonies from one area to another adjacent living area through wall spaces or ventilation, or through passive transportation in luggage, clothing, furniture, used mattresses, bookbags, and other personal items.1 Although infestation affects people of all socioeconomic classes and backgrounds, the likelihood increases in people who frequently travel and people who live in lower income neighborhoods with tightly packed apartments. Bedbug infestations are also common in refugee camps: 98% of the rooms in a refugee camp in Sierra Leone had bedbugs, and almost 90% of the residents had signs of bites.12 Unlike scabies, direct person-to-person, skin-to-skin transfer is rare.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Bedbug bites are analogous, almost identical, to other arthropod bites: bites begin as pink macules that progress to papules (Figure 2), large plaques, or wheals (hives).13 Bites can arise minutes or even days after the initial assault. Some papules and plaques may have a central crust or erosion suggesting a bite.

Bites are typically intensely pruritic, and occasionally, hypersensitive victims can develop bullae, necrotic plaques, or even vasculitis. New papules and plaques form as older ones heal. Some patients may have fever and malaise.13 About 30% of patients may not have skin disease from bedbugs, making diagnosis in those individuals impossible.

The nonspecific nature of this presentation and the subsequent difficulty in prompt diagnosis can lead to a prolonged period of morbidity for the patient, as well as increasing the window of opportunity for the bedbugs to affect other surrounding individuals.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS IS BROAD

Commonly, bedbug bites have been misdiagnosed as drug eruptions, food allergies, dermatitis herpetiformis, staphylococcal or varicella infection, and scabies, as well as other arthropod bites.11 This broad differential diagnosis can often be narrowed by careful observation of the bite distribution. The clustering of bites in groups of 3, often in a linear pattern, sometimes overlying blood vessels, is known as the “breakfast, lunch, and dinner” sign (Figure 3), and this can help to guide the clinician toward the diagnosis of a bite as opposed to a diffuse urticarial response.2