User login

Prazosin and doxazosin for PTSD are underutilized and underdosed

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

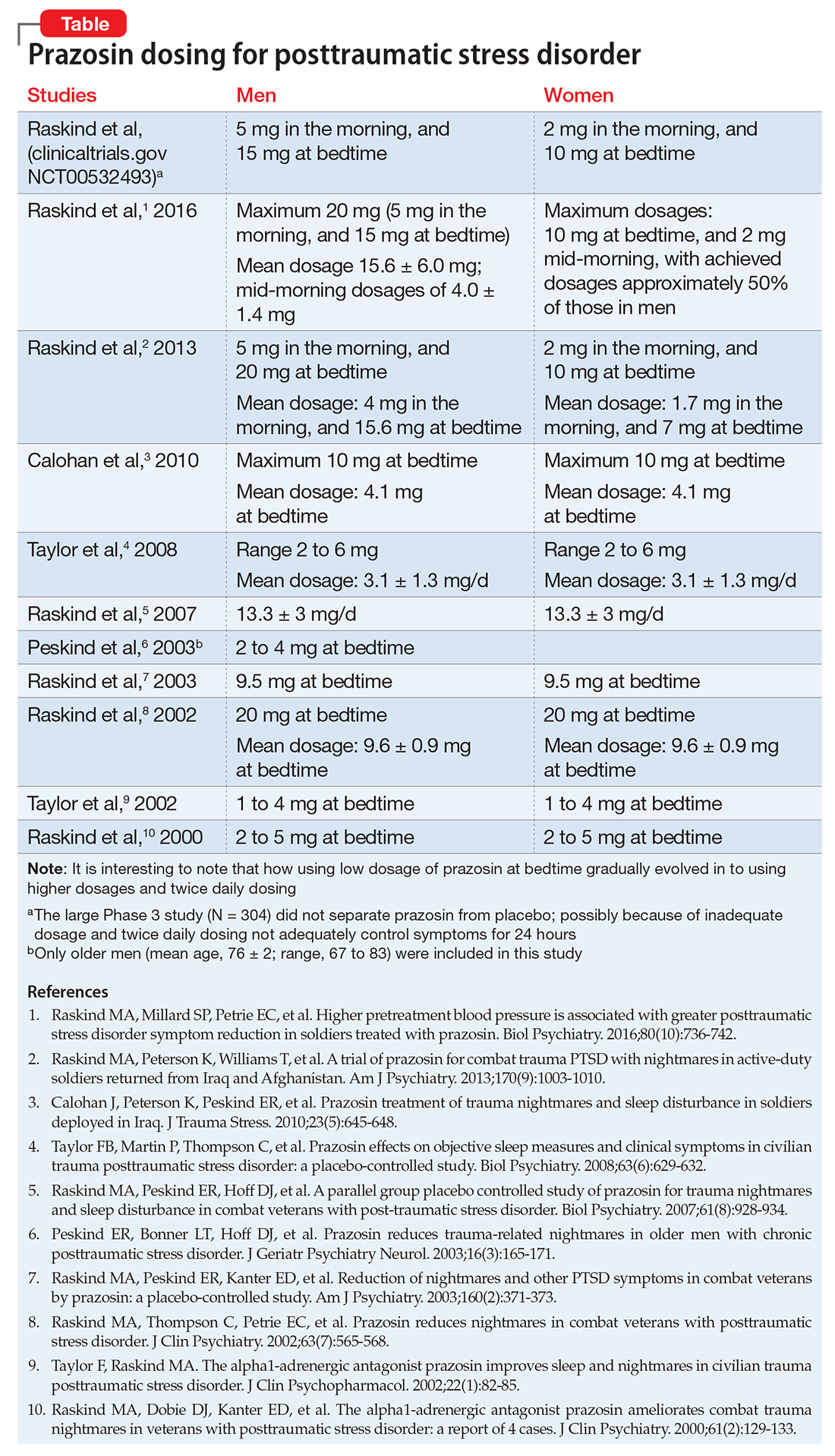

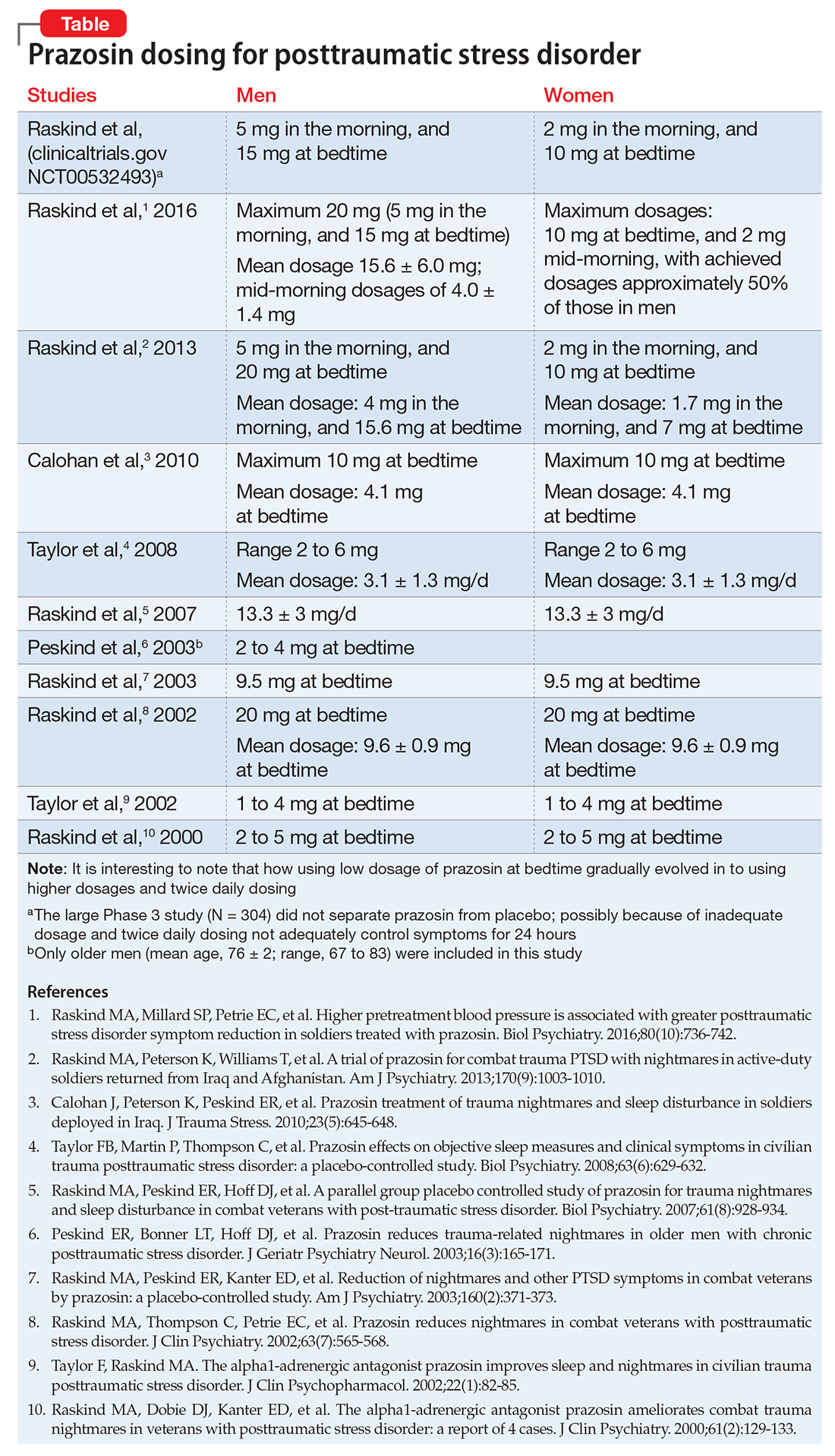

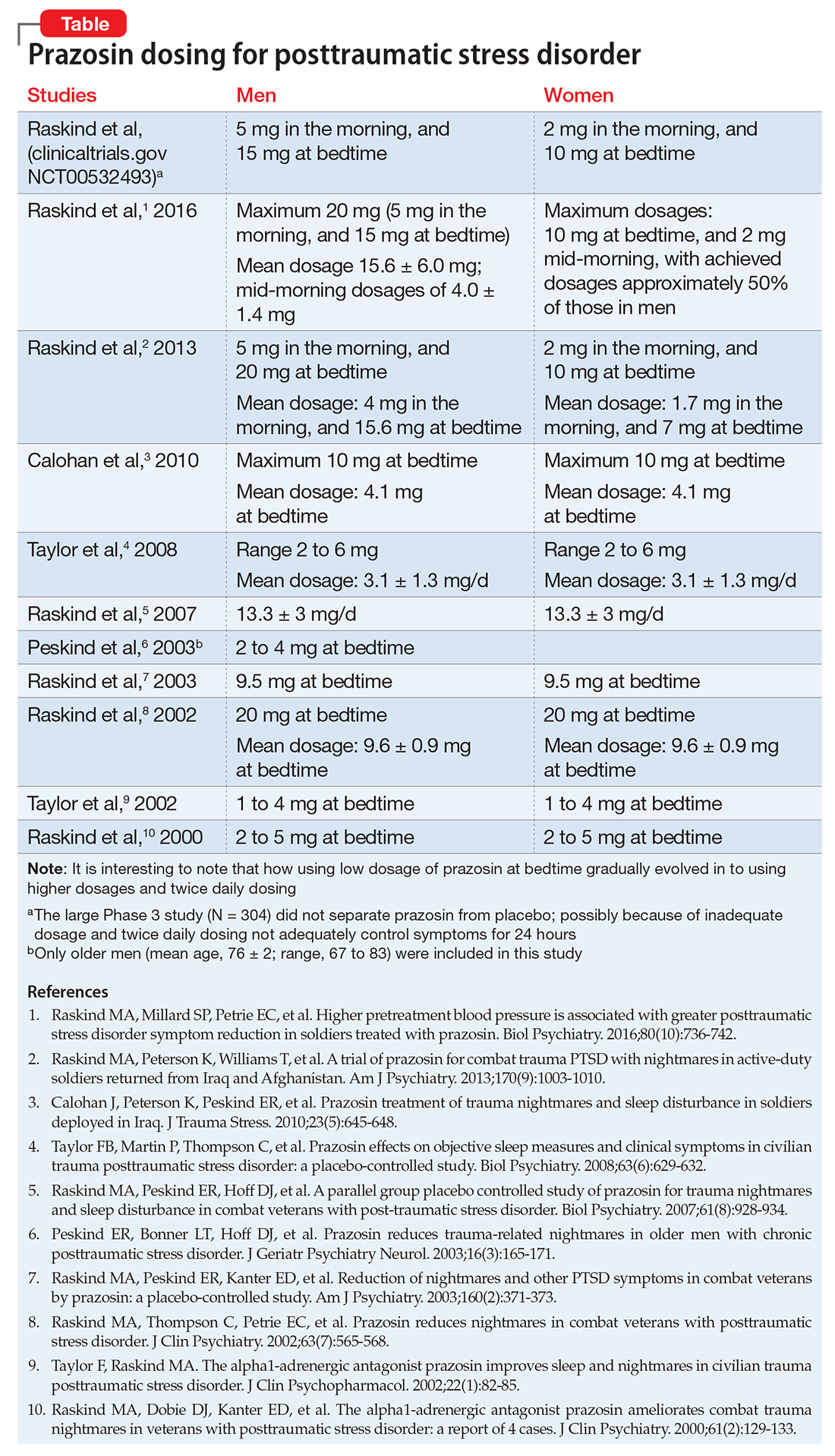

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

Opioid use remits, depression remains

Case Forgetful and depressed

Mr. B, age 55, has been a patient at our clinic for 8 years, where he has been under our care for treatment-resistant depression and opioid addiction [read about earlier events in his case in “A life of drugs and ‘downtime’” Current Psychiatry, August 2007, p. 98-103].1 He reports feeling intermittently depressed since his teens and has had 3 near-fatal suicide attempts.

Three years ago, Mr. B reported severe depressive symptoms and short-term memory loss, which undermined his job performance and contributed to interpersonal conflict with his wife. The episode has been continuously severe for 10 months. He was taking sertraline, 150 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, for major depressive disorder (MDD) and sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone, 20 mg/d, for opioid dependence, which was in sustained full remission.2 Mr. B scored 24/30 in the Mini- Mental State Examination, indicating mild cognitive deficit. Negative results of a complete routine laboratory workup rule out an organic cause for his deteriorating cognition.

How would you diagnose Mr. B’s condition at this point?

a) treatment-resistant MDD

b) cognitive disorder not otherwise specified

c) opioid use disorder

d) a and c

The authors' observations

Relapse is a core feature of substance use disorders (SUDs) that contributes significantly to the longstanding functional impairment in patients with a mood disorder. With the relapse rate following substance use treatment estimated at more than 60%,3 SUDs often are described as chronic relapsing conditions. In chronic stress, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is over-sensitized; we believe that acute stress can cause an unhealthy response to an over-expressed CRF system.

To prevent relapse in patients with an over-expressed CRF system, it is crucial to manage stress. One treatment option to consider in preventing relapse is mindfulness-based interventions (MBI). Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.” In the event of a relapse, awareness and acceptance fostered by mindfulness may aid in recognizing and minimizing unhealthy responses, such as negative thinking that can increase the risk of relapse.

History Remission, then relapse

Mr. B was admitted to inpatient psychiatric unit after a near-fatal suicide attempt 8 years ago and given a diagnosis of MDD recurrent, severe without psychotic features. Trials of sertraline, bupropion, trazodone, quetiapine, and aripiprazole were ineffective.

Before he presented to our clinic 8 years ago, Mr. B had been taking venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, and mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime. His previous outpatient psychiatrist added methylphenidate, 40 mg/d, to augment the antidepressants, but this did not alleviate Mr. B’s depression.

At age 40, he entered a methadone program, began working steadily, and got married. Five years later, he stopped methadone (it is unclear from the chart if his psychiatrist initiated this change). Mr. B’s depression persisted while using opioids and became worse after stopping methadone.

We considered electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at the time, but switching the antidepressant or starting ECT would address only the persistent depression; buprenorphine/naloxone would target opioid craving. We started a trial of buprenorphine/ naloxone, a partial μ opioid agonist and ĸ opioid antagonist; ĸ receptor antagonism serves as an antidepressant. He responded well to augmentation of his current regimen (mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime, and venlafaxine, 225 mg/d) with buprenorphine/naloxone, 16 mg/d.4,5 he reported no anergia and said he felt more motivated and productive.

Mr. B took buprenorphine/naloxone, 32 mg/d, for 4 years until, because of concern for daytime sedation, his outpatient psychiatrist reduced the dose to 20 mg/d. With the lower dosage of buprenorphine/naloxone initiated 4 years ago, Mr. B reported irritability, anhedonia, insomnia, increased self-criticism, and decreased self-care.

How would you treat Mr. B’s depression at this point?

a) switch to a daytime antidepressant

b) adjust the dosage of buprenorphine/ naloxone

c) try ECT

d) try mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

The authors’ observations

Mindfulness meditation (MM) is a meditation practice that cultivates awareness. While learning MM, the practitioner intentionally focuses on awareness—a way of purposely paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally, to nurture calmness and self-acceptance. Being conscious of what the practitioner is doing while he is doing it is the core of mindfulness practice.6

Mindfulness-based interventions. We recommended the following forms of MBI to treat Mr. B:

• Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). MBCT is designed to help people who suffer repeated bouts of depression and chronic unhappiness. It combines the ideas of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with MM practices and attitudes based on cultivating mindfulness.7

• Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). MBSR brings together MM and physical/breathing exercises to relax body and mind.6

Chronic stress and drug addiction

The literature demonstrates a significant association between acute and chronic stress and motivation to abuse substances. Stress mobilizes the CRF system to stimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and extra-hypothalamic actions of CRF can kindle the neuronal circuits responsible for stress-induced anxiety, dysphoria, and drug abuse behaviors.8

A study to evaluate effects of mindfulness on young adult romantic partners’ HPA responses to conflict stress showed that MM has sex-specific effects on neuroendocrine response to interpersonal stress.9 Research has shown that MM practice can decrease stress, increase well-being, and affect brain structure and function.10 Meta-analysis of studies of animal models and humans described how specific interventions intended to encourage pro-social behavior and well-being might produce plasticity-related changes in the brain.11 This work concluded that, by taking responsibility for the mind and the brain by participating in regular mental exercise, plastic changes in the brain promoted could produce lasting beneficial consequences for social and emotional behavior.11

What could be perpetuating Mr. B’s depression?

a) psychosocial stressors

b) over-expression of CRF gene due to psychosocial stressors

c) a and b

Treatment Mindfulness practice

Mr. B was started on CBT to manage anxiety symptoms and cognitive distortions. After 2 months, he reports no improvements in anxiety, depression, or cognitive distortions.

We consider MBI for Mr. B, which was developed by Segal et al7 to help prevent relapse of depression and gain the benefits of MM. There is evidence that MBI can prevent relapse of SUDs.12 Mr. B’s MBI practice is based on MBCT, as outlined by Segal et al.7 He attends biweekly, 45-minute therapy sessions at our outpatient clinic. During these sessions, MM is practiced for 10 minutes under a psychiatrist’s supervision. The MBCT manual calls for 45 minutes of MM practice but, during the 10-minute session, we instruct Mr. B to independently practice MM at home. Mr. B is assessed for relapses, and drug cravings; a urine toxicology screen is performed every 6 months.

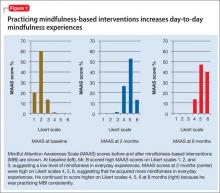

We score Mr. B’s day-to-day level of mindfulness experience, depression, and anxiety symptoms before starting MBI and after 8 weeks of practicing MBI (Figure 1). Mindfulness is scored with the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a valid, reliable scale.13 The MAAS comprises 15 items designed to reflect mindfulness in everyday experiences, including awareness and attention to thoughts, emotions, actions, and physical states. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale of 1 (“almost never”) to 6 (“almost always”). A typical item on MAAS is “I find myself doing things without paying attention.”

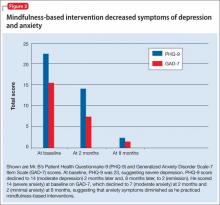

Depression and anxiety symptoms are measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) Item Scale. Mr. B scores a 23 on PHQ-9, indicating severe depression (he reports that he finds it ‘‘extremely difficult” to function) (Figure 2).

There is evidence to support the use of PHQ-9 for measurement-based care in the psychiatric population.14 PHQ-9 does not capture anxiety, which is a strong predicator of suicidal behavior; therefore, we use GAD-7 to measure the severity of Mr. B’s subjective anxiety.15 He scores a 14 on GAD-7 and reports that it is “very difficult” for him to function.

Mr. B is retested after 8 weeks. During those 8 weeks, he was instructed by audio guidance in body scan technique. He practices MBI techniques for 45 minutes every morning between 5 AM and 6 AM.6

After 3 months of MBI, Mr. B is promoted at work and reports that he is handling more responsibilities. He is stressed at his new job and, subsequently, experiences a relapse of anxiety symptoms and insomnia. Partly, this is because Mr. B is not able to consistently practice MBI and misses a few outpatient appointments. In the meantime, he has difficulties with sleep and concentration and anxiety symptoms.

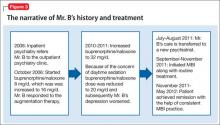

The treating psychiatrist reassures Mr. B and provides support to restart MBI. He manages to attend outpatient clinic appointments consistently and shows interest in practicing MBI daily. Later, he reports practicing MBI consistently along with his routine treatment at our clinic. The timeline of Mr. B’s history and treatment are summarized in Figure 3.

The authors’ observations

Mr. B’s CRF may have been down-regulated by MBI. This, in turn, decreased his depressive and anxiety symptoms, thereby helping to prevent relapse of depression and substance abuse. He benefited from MBI practices in several areas of his life, which can be described with the acronym FACES.10

Flexible. Mr. B became more cognitively flexible. He started to realize that “thoughts are not facts.”7 This change was reflected in his relationship with his wife. His wife came to one of our sessions because she noticed significant change in his attitude toward her. Their marriage of 15 years was riddled with conflict and his wife was excited to see the improvement he achieved within the short time of practicing MBI.

Adaptive. He became more adaptive to changes at the work place and reported that he is enjoying his work. This is a change from his feeling that his job was a burden, as he observed in our earlier sessions.

Coherent. He became more cognitively rational. He reported improvement in his memory and concentration. Five months after initiation of MBI and MM training, he was promoted and could cope with the stress at work.

Energized. Initially, he had said that he never wanted to be part of his extended family. During a session toward the end of the treatment, he mentioned that he made an effort to contact his extended family and reported that he found it more meaningful now to be reconnected with them.

Stable. He became more emotionally stable. He did not have the urge to use drugs and he did not relapse.

As we hypothesized, for Mr. B, practicing MBI was associated with abstinence from substance use, increased mindfulness, acceptance of mental health problems, and remission of psychiatric symptoms.

Bottom Line

Mindfulness-based interventions provide patients with tools to target symptoms such as poor affect regulation, poor impulse control, and rumination. Evidence supports that using MBI in addition to the usual treatment can prevent relapse of a substance use disorder.

Related Resources

• Sipe WE, Eisendrath SJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: theory and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):63-69.• Lau MA, Grabovac AD. Mindfulness-based interventions: Effective for depression and anxiety. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(12):39-55.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Quetiapine • Seroquel

Suboxone

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Sertraline • Zoloft

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Trazodone • Desyrel

Methadone • Dolophine Venlafaxine • Effexor

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

Acknowledgement

The manuscript preparation of Maju Mathew Koola, MD, DPM was supported by the NIMH T32 grant MH067533-07 (PI: William T. Carpenter, MD) and the American Psychiatric Association/Kempf Fund Award for Research Development in Psychobiological Psychiatry (PI: Koola). The treating Psychiatrist PGY-5 (2011-2012) Addiction Psychiatry fellow (Dr. Varghese) was supervised by Dr. Eiger. Drs. Koola and Varghese contributed equally with the manuscript preparation and are joint first authors. Dr. Varghese received a second prize for a poster presentation of this case report at the 34th Indo American Psychiatric Association meeting in San Francisco, CA, May 19, 2013. Christina Mathew, MD, also contributed with manuscript preparation.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufactures of competing products.

1. Tan EM, Eiger RI, Roth JD. A life of drugs and ‘downtime.’ Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):98-103.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

4. Schreiber S, Bleich A, Pick CG. Venlafaxine and mirtazapine: different mechanisms of antidepressant action, common opioid-mediated antinociceptive effects—a possible opioid involvement in severe depression? J Mol Neurosci. 2002; 18(1-2):143-149.

5. Sikka P, Kaushik S, Kumar G, et al. Study of antinociceptive activity of SSRI (fluoxetine and escitalopram) and atypical antidepressants (venlafaxine and mirtazepine) and their interaction with morphine and naloxone in mice. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(3):412-416.

6. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. 15th ed. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1990.

7. Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach for preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002.

8. Koob GF. The role of CRF and CRF-related peptides in the dark side of addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:3-14.

9. Laurent H, Laurent S, Hertz R, et al. Sex-specific effects of mindfulness on romantic partners’ cortisol responses to conflict and relations with psychological adjustment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2905-2913.

10. Siegel DJ. The mindful brain: reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company; 2007.

11. Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(5):689-695.

12. Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, et al. Mindfulness-based prevention for substance use disorders: a pilot efficacy trial. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):295-305.

13. Grossman P. Defining mindfulness by how poorly I think I pay attention during everyday awareness and other intractable problems for psychology’s (re)invention of mindfulness: comment on Brown et al. (2001). Psychol Assess. 2011;23(4):1034-1040; discussion 1041-1046.

14. Koola MM, Fawcett JA, Kelly DL. Case report on the management of depression in schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type focusing on lithium levels and measurement-based care. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(12):989-990.

15. Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123.

Case Forgetful and depressed

Mr. B, age 55, has been a patient at our clinic for 8 years, where he has been under our care for treatment-resistant depression and opioid addiction [read about earlier events in his case in “A life of drugs and ‘downtime’” Current Psychiatry, August 2007, p. 98-103].1 He reports feeling intermittently depressed since his teens and has had 3 near-fatal suicide attempts.

Three years ago, Mr. B reported severe depressive symptoms and short-term memory loss, which undermined his job performance and contributed to interpersonal conflict with his wife. The episode has been continuously severe for 10 months. He was taking sertraline, 150 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, for major depressive disorder (MDD) and sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone, 20 mg/d, for opioid dependence, which was in sustained full remission.2 Mr. B scored 24/30 in the Mini- Mental State Examination, indicating mild cognitive deficit. Negative results of a complete routine laboratory workup rule out an organic cause for his deteriorating cognition.

How would you diagnose Mr. B’s condition at this point?

a) treatment-resistant MDD

b) cognitive disorder not otherwise specified

c) opioid use disorder

d) a and c

The authors' observations

Relapse is a core feature of substance use disorders (SUDs) that contributes significantly to the longstanding functional impairment in patients with a mood disorder. With the relapse rate following substance use treatment estimated at more than 60%,3 SUDs often are described as chronic relapsing conditions. In chronic stress, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is over-sensitized; we believe that acute stress can cause an unhealthy response to an over-expressed CRF system.

To prevent relapse in patients with an over-expressed CRF system, it is crucial to manage stress. One treatment option to consider in preventing relapse is mindfulness-based interventions (MBI). Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.” In the event of a relapse, awareness and acceptance fostered by mindfulness may aid in recognizing and minimizing unhealthy responses, such as negative thinking that can increase the risk of relapse.

History Remission, then relapse

Mr. B was admitted to inpatient psychiatric unit after a near-fatal suicide attempt 8 years ago and given a diagnosis of MDD recurrent, severe without psychotic features. Trials of sertraline, bupropion, trazodone, quetiapine, and aripiprazole were ineffective.

Before he presented to our clinic 8 years ago, Mr. B had been taking venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, and mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime. His previous outpatient psychiatrist added methylphenidate, 40 mg/d, to augment the antidepressants, but this did not alleviate Mr. B’s depression.

At age 40, he entered a methadone program, began working steadily, and got married. Five years later, he stopped methadone (it is unclear from the chart if his psychiatrist initiated this change). Mr. B’s depression persisted while using opioids and became worse after stopping methadone.

We considered electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at the time, but switching the antidepressant or starting ECT would address only the persistent depression; buprenorphine/naloxone would target opioid craving. We started a trial of buprenorphine/ naloxone, a partial μ opioid agonist and ĸ opioid antagonist; ĸ receptor antagonism serves as an antidepressant. He responded well to augmentation of his current regimen (mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime, and venlafaxine, 225 mg/d) with buprenorphine/naloxone, 16 mg/d.4,5 he reported no anergia and said he felt more motivated and productive.

Mr. B took buprenorphine/naloxone, 32 mg/d, for 4 years until, because of concern for daytime sedation, his outpatient psychiatrist reduced the dose to 20 mg/d. With the lower dosage of buprenorphine/naloxone initiated 4 years ago, Mr. B reported irritability, anhedonia, insomnia, increased self-criticism, and decreased self-care.

How would you treat Mr. B’s depression at this point?

a) switch to a daytime antidepressant

b) adjust the dosage of buprenorphine/ naloxone

c) try ECT

d) try mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

The authors’ observations

Mindfulness meditation (MM) is a meditation practice that cultivates awareness. While learning MM, the practitioner intentionally focuses on awareness—a way of purposely paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally, to nurture calmness and self-acceptance. Being conscious of what the practitioner is doing while he is doing it is the core of mindfulness practice.6

Mindfulness-based interventions. We recommended the following forms of MBI to treat Mr. B:

• Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). MBCT is designed to help people who suffer repeated bouts of depression and chronic unhappiness. It combines the ideas of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with MM practices and attitudes based on cultivating mindfulness.7

• Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). MBSR brings together MM and physical/breathing exercises to relax body and mind.6

Chronic stress and drug addiction

The literature demonstrates a significant association between acute and chronic stress and motivation to abuse substances. Stress mobilizes the CRF system to stimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and extra-hypothalamic actions of CRF can kindle the neuronal circuits responsible for stress-induced anxiety, dysphoria, and drug abuse behaviors.8

A study to evaluate effects of mindfulness on young adult romantic partners’ HPA responses to conflict stress showed that MM has sex-specific effects on neuroendocrine response to interpersonal stress.9 Research has shown that MM practice can decrease stress, increase well-being, and affect brain structure and function.10 Meta-analysis of studies of animal models and humans described how specific interventions intended to encourage pro-social behavior and well-being might produce plasticity-related changes in the brain.11 This work concluded that, by taking responsibility for the mind and the brain by participating in regular mental exercise, plastic changes in the brain promoted could produce lasting beneficial consequences for social and emotional behavior.11

What could be perpetuating Mr. B’s depression?

a) psychosocial stressors

b) over-expression of CRF gene due to psychosocial stressors

c) a and b

Treatment Mindfulness practice

Mr. B was started on CBT to manage anxiety symptoms and cognitive distortions. After 2 months, he reports no improvements in anxiety, depression, or cognitive distortions.

We consider MBI for Mr. B, which was developed by Segal et al7 to help prevent relapse of depression and gain the benefits of MM. There is evidence that MBI can prevent relapse of SUDs.12 Mr. B’s MBI practice is based on MBCT, as outlined by Segal et al.7 He attends biweekly, 45-minute therapy sessions at our outpatient clinic. During these sessions, MM is practiced for 10 minutes under a psychiatrist’s supervision. The MBCT manual calls for 45 minutes of MM practice but, during the 10-minute session, we instruct Mr. B to independently practice MM at home. Mr. B is assessed for relapses, and drug cravings; a urine toxicology screen is performed every 6 months.

We score Mr. B’s day-to-day level of mindfulness experience, depression, and anxiety symptoms before starting MBI and after 8 weeks of practicing MBI (Figure 1). Mindfulness is scored with the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a valid, reliable scale.13 The MAAS comprises 15 items designed to reflect mindfulness in everyday experiences, including awareness and attention to thoughts, emotions, actions, and physical states. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale of 1 (“almost never”) to 6 (“almost always”). A typical item on MAAS is “I find myself doing things without paying attention.”

Depression and anxiety symptoms are measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) Item Scale. Mr. B scores a 23 on PHQ-9, indicating severe depression (he reports that he finds it ‘‘extremely difficult” to function) (Figure 2).

There is evidence to support the use of PHQ-9 for measurement-based care in the psychiatric population.14 PHQ-9 does not capture anxiety, which is a strong predicator of suicidal behavior; therefore, we use GAD-7 to measure the severity of Mr. B’s subjective anxiety.15 He scores a 14 on GAD-7 and reports that it is “very difficult” for him to function.

Mr. B is retested after 8 weeks. During those 8 weeks, he was instructed by audio guidance in body scan technique. He practices MBI techniques for 45 minutes every morning between 5 AM and 6 AM.6

After 3 months of MBI, Mr. B is promoted at work and reports that he is handling more responsibilities. He is stressed at his new job and, subsequently, experiences a relapse of anxiety symptoms and insomnia. Partly, this is because Mr. B is not able to consistently practice MBI and misses a few outpatient appointments. In the meantime, he has difficulties with sleep and concentration and anxiety symptoms.

The treating psychiatrist reassures Mr. B and provides support to restart MBI. He manages to attend outpatient clinic appointments consistently and shows interest in practicing MBI daily. Later, he reports practicing MBI consistently along with his routine treatment at our clinic. The timeline of Mr. B’s history and treatment are summarized in Figure 3.

The authors’ observations

Mr. B’s CRF may have been down-regulated by MBI. This, in turn, decreased his depressive and anxiety symptoms, thereby helping to prevent relapse of depression and substance abuse. He benefited from MBI practices in several areas of his life, which can be described with the acronym FACES.10

Flexible. Mr. B became more cognitively flexible. He started to realize that “thoughts are not facts.”7 This change was reflected in his relationship with his wife. His wife came to one of our sessions because she noticed significant change in his attitude toward her. Their marriage of 15 years was riddled with conflict and his wife was excited to see the improvement he achieved within the short time of practicing MBI.

Adaptive. He became more adaptive to changes at the work place and reported that he is enjoying his work. This is a change from his feeling that his job was a burden, as he observed in our earlier sessions.

Coherent. He became more cognitively rational. He reported improvement in his memory and concentration. Five months after initiation of MBI and MM training, he was promoted and could cope with the stress at work.

Energized. Initially, he had said that he never wanted to be part of his extended family. During a session toward the end of the treatment, he mentioned that he made an effort to contact his extended family and reported that he found it more meaningful now to be reconnected with them.

Stable. He became more emotionally stable. He did not have the urge to use drugs and he did not relapse.

As we hypothesized, for Mr. B, practicing MBI was associated with abstinence from substance use, increased mindfulness, acceptance of mental health problems, and remission of psychiatric symptoms.

Bottom Line

Mindfulness-based interventions provide patients with tools to target symptoms such as poor affect regulation, poor impulse control, and rumination. Evidence supports that using MBI in addition to the usual treatment can prevent relapse of a substance use disorder.

Related Resources

• Sipe WE, Eisendrath SJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: theory and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):63-69.• Lau MA, Grabovac AD. Mindfulness-based interventions: Effective for depression and anxiety. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(12):39-55.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Quetiapine • Seroquel

Suboxone

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Sertraline • Zoloft

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Trazodone • Desyrel

Methadone • Dolophine Venlafaxine • Effexor

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

Acknowledgement

The manuscript preparation of Maju Mathew Koola, MD, DPM was supported by the NIMH T32 grant MH067533-07 (PI: William T. Carpenter, MD) and the American Psychiatric Association/Kempf Fund Award for Research Development in Psychobiological Psychiatry (PI: Koola). The treating Psychiatrist PGY-5 (2011-2012) Addiction Psychiatry fellow (Dr. Varghese) was supervised by Dr. Eiger. Drs. Koola and Varghese contributed equally with the manuscript preparation and are joint first authors. Dr. Varghese received a second prize for a poster presentation of this case report at the 34th Indo American Psychiatric Association meeting in San Francisco, CA, May 19, 2013. Christina Mathew, MD, also contributed with manuscript preparation.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufactures of competing products.

Case Forgetful and depressed

Mr. B, age 55, has been a patient at our clinic for 8 years, where he has been under our care for treatment-resistant depression and opioid addiction [read about earlier events in his case in “A life of drugs and ‘downtime’” Current Psychiatry, August 2007, p. 98-103].1 He reports feeling intermittently depressed since his teens and has had 3 near-fatal suicide attempts.

Three years ago, Mr. B reported severe depressive symptoms and short-term memory loss, which undermined his job performance and contributed to interpersonal conflict with his wife. The episode has been continuously severe for 10 months. He was taking sertraline, 150 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, for major depressive disorder (MDD) and sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone, 20 mg/d, for opioid dependence, which was in sustained full remission.2 Mr. B scored 24/30 in the Mini- Mental State Examination, indicating mild cognitive deficit. Negative results of a complete routine laboratory workup rule out an organic cause for his deteriorating cognition.

How would you diagnose Mr. B’s condition at this point?

a) treatment-resistant MDD

b) cognitive disorder not otherwise specified

c) opioid use disorder

d) a and c

The authors' observations

Relapse is a core feature of substance use disorders (SUDs) that contributes significantly to the longstanding functional impairment in patients with a mood disorder. With the relapse rate following substance use treatment estimated at more than 60%,3 SUDs often are described as chronic relapsing conditions. In chronic stress, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is over-sensitized; we believe that acute stress can cause an unhealthy response to an over-expressed CRF system.

To prevent relapse in patients with an over-expressed CRF system, it is crucial to manage stress. One treatment option to consider in preventing relapse is mindfulness-based interventions (MBI). Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.” In the event of a relapse, awareness and acceptance fostered by mindfulness may aid in recognizing and minimizing unhealthy responses, such as negative thinking that can increase the risk of relapse.

History Remission, then relapse

Mr. B was admitted to inpatient psychiatric unit after a near-fatal suicide attempt 8 years ago and given a diagnosis of MDD recurrent, severe without psychotic features. Trials of sertraline, bupropion, trazodone, quetiapine, and aripiprazole were ineffective.

Before he presented to our clinic 8 years ago, Mr. B had been taking venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, and mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime. His previous outpatient psychiatrist added methylphenidate, 40 mg/d, to augment the antidepressants, but this did not alleviate Mr. B’s depression.

At age 40, he entered a methadone program, began working steadily, and got married. Five years later, he stopped methadone (it is unclear from the chart if his psychiatrist initiated this change). Mr. B’s depression persisted while using opioids and became worse after stopping methadone.

We considered electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at the time, but switching the antidepressant or starting ECT would address only the persistent depression; buprenorphine/naloxone would target opioid craving. We started a trial of buprenorphine/ naloxone, a partial μ opioid agonist and ĸ opioid antagonist; ĸ receptor antagonism serves as an antidepressant. He responded well to augmentation of his current regimen (mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime, and venlafaxine, 225 mg/d) with buprenorphine/naloxone, 16 mg/d.4,5 he reported no anergia and said he felt more motivated and productive.

Mr. B took buprenorphine/naloxone, 32 mg/d, for 4 years until, because of concern for daytime sedation, his outpatient psychiatrist reduced the dose to 20 mg/d. With the lower dosage of buprenorphine/naloxone initiated 4 years ago, Mr. B reported irritability, anhedonia, insomnia, increased self-criticism, and decreased self-care.

How would you treat Mr. B’s depression at this point?

a) switch to a daytime antidepressant

b) adjust the dosage of buprenorphine/ naloxone

c) try ECT

d) try mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

The authors’ observations

Mindfulness meditation (MM) is a meditation practice that cultivates awareness. While learning MM, the practitioner intentionally focuses on awareness—a way of purposely paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally, to nurture calmness and self-acceptance. Being conscious of what the practitioner is doing while he is doing it is the core of mindfulness practice.6

Mindfulness-based interventions. We recommended the following forms of MBI to treat Mr. B:

• Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). MBCT is designed to help people who suffer repeated bouts of depression and chronic unhappiness. It combines the ideas of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with MM practices and attitudes based on cultivating mindfulness.7

• Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). MBSR brings together MM and physical/breathing exercises to relax body and mind.6

Chronic stress and drug addiction

The literature demonstrates a significant association between acute and chronic stress and motivation to abuse substances. Stress mobilizes the CRF system to stimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and extra-hypothalamic actions of CRF can kindle the neuronal circuits responsible for stress-induced anxiety, dysphoria, and drug abuse behaviors.8

A study to evaluate effects of mindfulness on young adult romantic partners’ HPA responses to conflict stress showed that MM has sex-specific effects on neuroendocrine response to interpersonal stress.9 Research has shown that MM practice can decrease stress, increase well-being, and affect brain structure and function.10 Meta-analysis of studies of animal models and humans described how specific interventions intended to encourage pro-social behavior and well-being might produce plasticity-related changes in the brain.11 This work concluded that, by taking responsibility for the mind and the brain by participating in regular mental exercise, plastic changes in the brain promoted could produce lasting beneficial consequences for social and emotional behavior.11

What could be perpetuating Mr. B’s depression?

a) psychosocial stressors

b) over-expression of CRF gene due to psychosocial stressors

c) a and b

Treatment Mindfulness practice

Mr. B was started on CBT to manage anxiety symptoms and cognitive distortions. After 2 months, he reports no improvements in anxiety, depression, or cognitive distortions.

We consider MBI for Mr. B, which was developed by Segal et al7 to help prevent relapse of depression and gain the benefits of MM. There is evidence that MBI can prevent relapse of SUDs.12 Mr. B’s MBI practice is based on MBCT, as outlined by Segal et al.7 He attends biweekly, 45-minute therapy sessions at our outpatient clinic. During these sessions, MM is practiced for 10 minutes under a psychiatrist’s supervision. The MBCT manual calls for 45 minutes of MM practice but, during the 10-minute session, we instruct Mr. B to independently practice MM at home. Mr. B is assessed for relapses, and drug cravings; a urine toxicology screen is performed every 6 months.

We score Mr. B’s day-to-day level of mindfulness experience, depression, and anxiety symptoms before starting MBI and after 8 weeks of practicing MBI (Figure 1). Mindfulness is scored with the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a valid, reliable scale.13 The MAAS comprises 15 items designed to reflect mindfulness in everyday experiences, including awareness and attention to thoughts, emotions, actions, and physical states. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale of 1 (“almost never”) to 6 (“almost always”). A typical item on MAAS is “I find myself doing things without paying attention.”

Depression and anxiety symptoms are measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) Item Scale. Mr. B scores a 23 on PHQ-9, indicating severe depression (he reports that he finds it ‘‘extremely difficult” to function) (Figure 2).

There is evidence to support the use of PHQ-9 for measurement-based care in the psychiatric population.14 PHQ-9 does not capture anxiety, which is a strong predicator of suicidal behavior; therefore, we use GAD-7 to measure the severity of Mr. B’s subjective anxiety.15 He scores a 14 on GAD-7 and reports that it is “very difficult” for him to function.

Mr. B is retested after 8 weeks. During those 8 weeks, he was instructed by audio guidance in body scan technique. He practices MBI techniques for 45 minutes every morning between 5 AM and 6 AM.6

After 3 months of MBI, Mr. B is promoted at work and reports that he is handling more responsibilities. He is stressed at his new job and, subsequently, experiences a relapse of anxiety symptoms and insomnia. Partly, this is because Mr. B is not able to consistently practice MBI and misses a few outpatient appointments. In the meantime, he has difficulties with sleep and concentration and anxiety symptoms.

The treating psychiatrist reassures Mr. B and provides support to restart MBI. He manages to attend outpatient clinic appointments consistently and shows interest in practicing MBI daily. Later, he reports practicing MBI consistently along with his routine treatment at our clinic. The timeline of Mr. B’s history and treatment are summarized in Figure 3.

The authors’ observations

Mr. B’s CRF may have been down-regulated by MBI. This, in turn, decreased his depressive and anxiety symptoms, thereby helping to prevent relapse of depression and substance abuse. He benefited from MBI practices in several areas of his life, which can be described with the acronym FACES.10

Flexible. Mr. B became more cognitively flexible. He started to realize that “thoughts are not facts.”7 This change was reflected in his relationship with his wife. His wife came to one of our sessions because she noticed significant change in his attitude toward her. Their marriage of 15 years was riddled with conflict and his wife was excited to see the improvement he achieved within the short time of practicing MBI.

Adaptive. He became more adaptive to changes at the work place and reported that he is enjoying his work. This is a change from his feeling that his job was a burden, as he observed in our earlier sessions.

Coherent. He became more cognitively rational. He reported improvement in his memory and concentration. Five months after initiation of MBI and MM training, he was promoted and could cope with the stress at work.

Energized. Initially, he had said that he never wanted to be part of his extended family. During a session toward the end of the treatment, he mentioned that he made an effort to contact his extended family and reported that he found it more meaningful now to be reconnected with them.

Stable. He became more emotionally stable. He did not have the urge to use drugs and he did not relapse.

As we hypothesized, for Mr. B, practicing MBI was associated with abstinence from substance use, increased mindfulness, acceptance of mental health problems, and remission of psychiatric symptoms.

Bottom Line

Mindfulness-based interventions provide patients with tools to target symptoms such as poor affect regulation, poor impulse control, and rumination. Evidence supports that using MBI in addition to the usual treatment can prevent relapse of a substance use disorder.

Related Resources

• Sipe WE, Eisendrath SJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: theory and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):63-69.• Lau MA, Grabovac AD. Mindfulness-based interventions: Effective for depression and anxiety. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(12):39-55.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Mirtazapine • Remeron

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Quetiapine • Seroquel

Suboxone

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Sertraline • Zoloft

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Trazodone • Desyrel

Methadone • Dolophine Venlafaxine • Effexor

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

Acknowledgement

The manuscript preparation of Maju Mathew Koola, MD, DPM was supported by the NIMH T32 grant MH067533-07 (PI: William T. Carpenter, MD) and the American Psychiatric Association/Kempf Fund Award for Research Development in Psychobiological Psychiatry (PI: Koola). The treating Psychiatrist PGY-5 (2011-2012) Addiction Psychiatry fellow (Dr. Varghese) was supervised by Dr. Eiger. Drs. Koola and Varghese contributed equally with the manuscript preparation and are joint first authors. Dr. Varghese received a second prize for a poster presentation of this case report at the 34th Indo American Psychiatric Association meeting in San Francisco, CA, May 19, 2013. Christina Mathew, MD, also contributed with manuscript preparation.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufactures of competing products.

1. Tan EM, Eiger RI, Roth JD. A life of drugs and ‘downtime.’ Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):98-103.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

4. Schreiber S, Bleich A, Pick CG. Venlafaxine and mirtazapine: different mechanisms of antidepressant action, common opioid-mediated antinociceptive effects—a possible opioid involvement in severe depression? J Mol Neurosci. 2002; 18(1-2):143-149.

5. Sikka P, Kaushik S, Kumar G, et al. Study of antinociceptive activity of SSRI (fluoxetine and escitalopram) and atypical antidepressants (venlafaxine and mirtazepine) and their interaction with morphine and naloxone in mice. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(3):412-416.

6. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. 15th ed. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1990.

7. Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach for preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002.

8. Koob GF. The role of CRF and CRF-related peptides in the dark side of addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:3-14.

9. Laurent H, Laurent S, Hertz R, et al. Sex-specific effects of mindfulness on romantic partners’ cortisol responses to conflict and relations with psychological adjustment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2905-2913.

10. Siegel DJ. The mindful brain: reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company; 2007.

11. Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(5):689-695.

12. Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, et al. Mindfulness-based prevention for substance use disorders: a pilot efficacy trial. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):295-305.

13. Grossman P. Defining mindfulness by how poorly I think I pay attention during everyday awareness and other intractable problems for psychology’s (re)invention of mindfulness: comment on Brown et al. (2001). Psychol Assess. 2011;23(4):1034-1040; discussion 1041-1046.

14. Koola MM, Fawcett JA, Kelly DL. Case report on the management of depression in schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type focusing on lithium levels and measurement-based care. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(12):989-990.

15. Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123.

1. Tan EM, Eiger RI, Roth JD. A life of drugs and ‘downtime.’ Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):98-103.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

4. Schreiber S, Bleich A, Pick CG. Venlafaxine and mirtazapine: different mechanisms of antidepressant action, common opioid-mediated antinociceptive effects—a possible opioid involvement in severe depression? J Mol Neurosci. 2002; 18(1-2):143-149.

5. Sikka P, Kaushik S, Kumar G, et al. Study of antinociceptive activity of SSRI (fluoxetine and escitalopram) and atypical antidepressants (venlafaxine and mirtazepine) and their interaction with morphine and naloxone in mice. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(3):412-416.

6. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. 15th ed. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1990.

7. Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach for preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002.

8. Koob GF. The role of CRF and CRF-related peptides in the dark side of addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:3-14.

9. Laurent H, Laurent S, Hertz R, et al. Sex-specific effects of mindfulness on romantic partners’ cortisol responses to conflict and relations with psychological adjustment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2905-2913.

10. Siegel DJ. The mindful brain: reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company; 2007.

11. Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(5):689-695.

12. Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, et al. Mindfulness-based prevention for substance use disorders: a pilot efficacy trial. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):295-305.

13. Grossman P. Defining mindfulness by how poorly I think I pay attention during everyday awareness and other intractable problems for psychology’s (re)invention of mindfulness: comment on Brown et al. (2001). Psychol Assess. 2011;23(4):1034-1040; discussion 1041-1046.

14. Koola MM, Fawcett JA, Kelly DL. Case report on the management of depression in schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type focusing on lithium levels and measurement-based care. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(12):989-990.

15. Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123.