User login

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

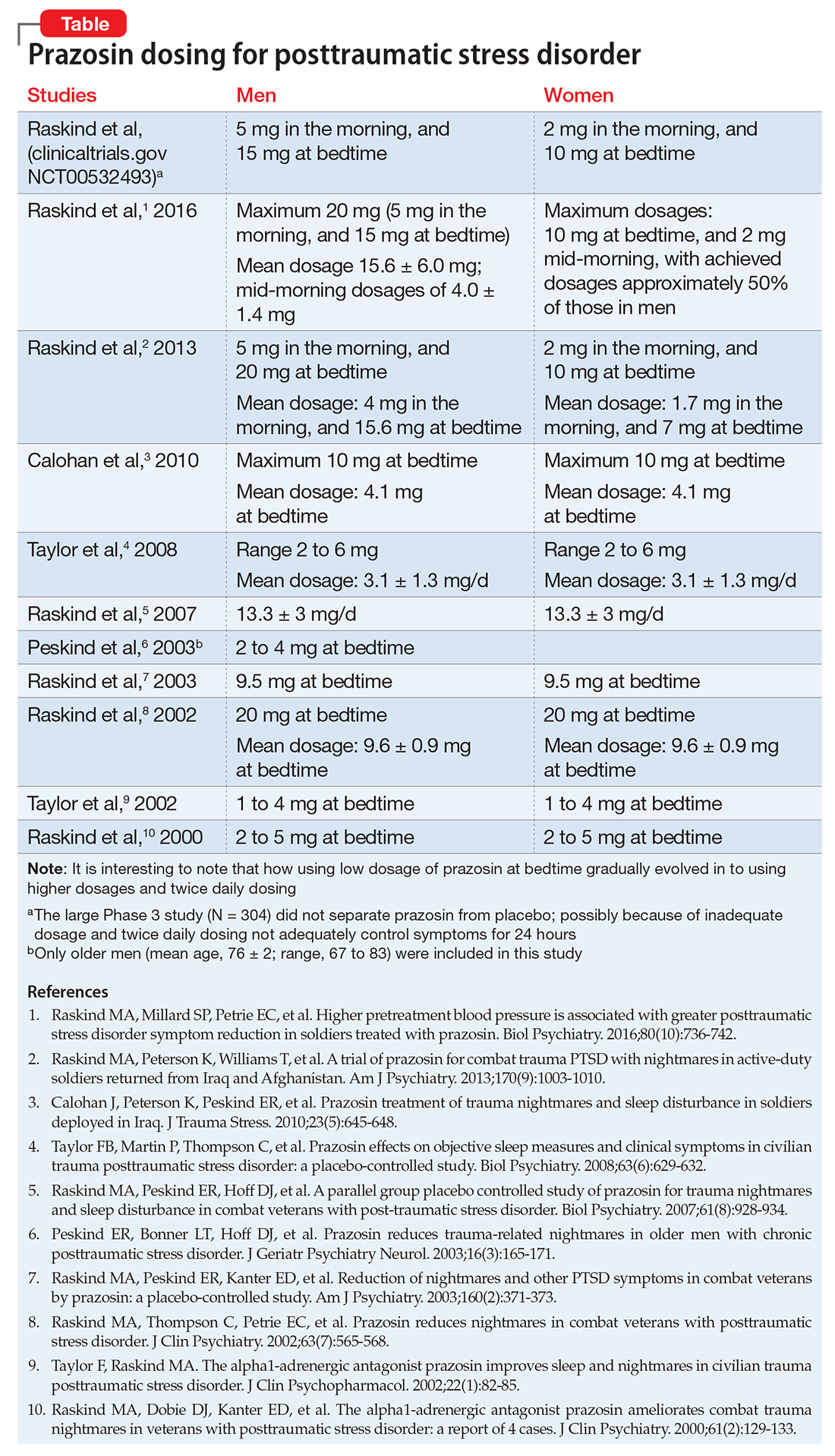

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

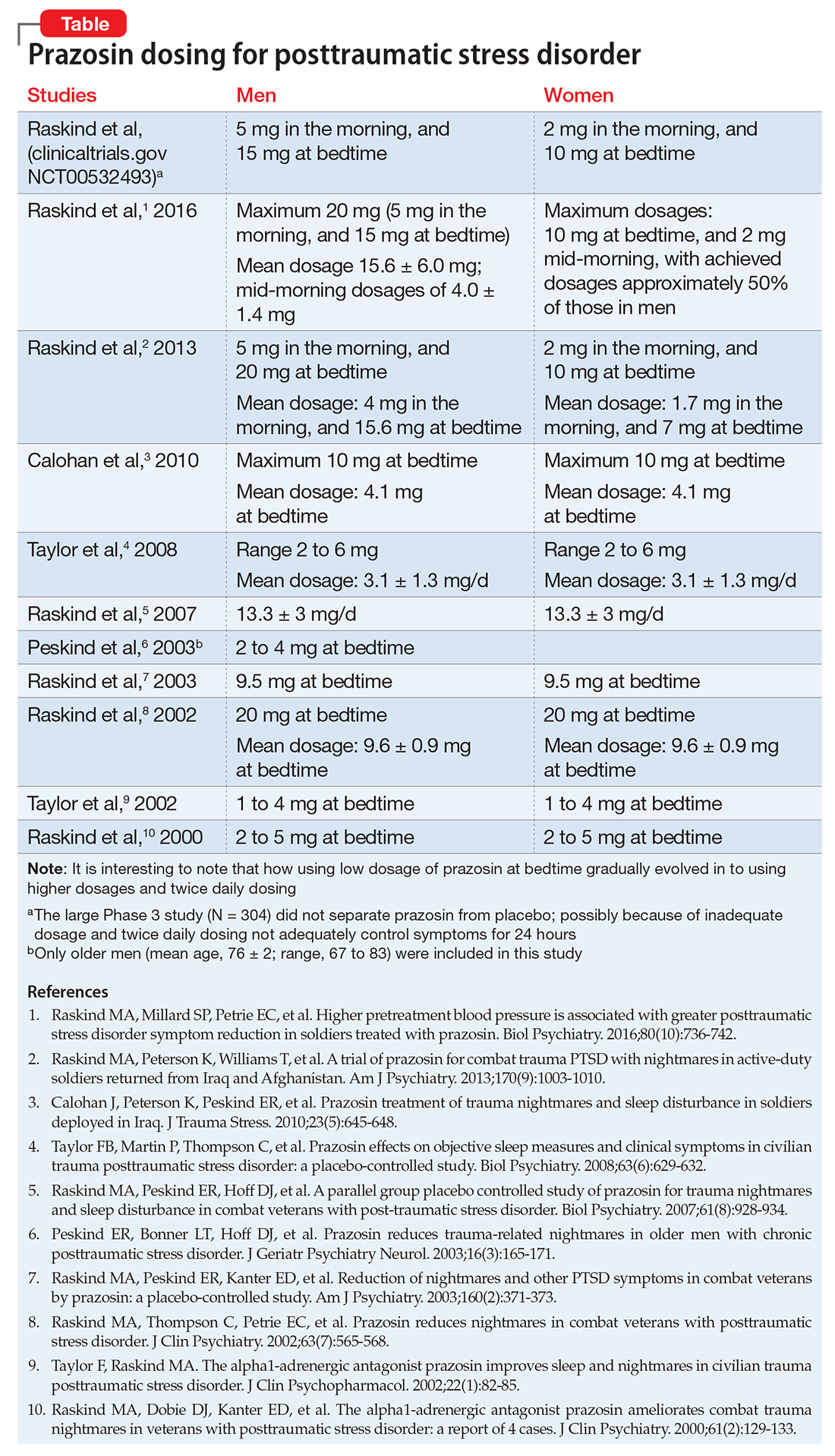

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

The primary symptoms of PTSD are recurrent and include intrusive memories and dreams of the traumatic events, flashbacks, hypervigilance, irritability, sleep disturbances, and persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults is 6.8% and is more common in women (9.7%) than men (3.6%).2 Among veterans, the prevalence of PTSD has been reported as:

- 31% among male Vietnam veterans (lifetime)

- 10% among Gulf War veterans

- 14% among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.3

Why is PTSD overlooked in substance use?

Among individuals with SUD, 10% to 63% have comorbid PTSD.4 A recent report underscores the complexity and challenges of SUD–PTSD comorbidity.5 Most PTSD patients with comorbid SUD receive treatment only for SUD and the PTSD symptoms often are unaddressed.5 Those suffering from PTSD often abuse alcohol because they might consider it to be a coping strategy. Alcohol reduces hyperactivation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex caused by re-experiencing PTSD symptoms. Other substances of abuse, such as Cannabis, could suppress PTSD symptoms through alternate mechanisms (eg, endocannabinoid receptors). All of these could mask PTSD symptoms, which can delay diagnosis and treatment.

SUD is the tip of the “SUD-PTSD iceberg.” Some clinicians tend to focus on detoxification while completely ignoring the underlying psychopathology of SUD, which may be PTSD. Even during detoxification, PTSD should be aggressively treated.6 Lastly, practice guidelines for managing SUD–PTSD comorbidity are lacking.

Targeting mechanisms of action

Noradrenergic mechanisms have been strongly implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are the only FDA-approved pharmacotherapy options for PTSD, although their efficacy is limited, perhaps because they are serotonergic.

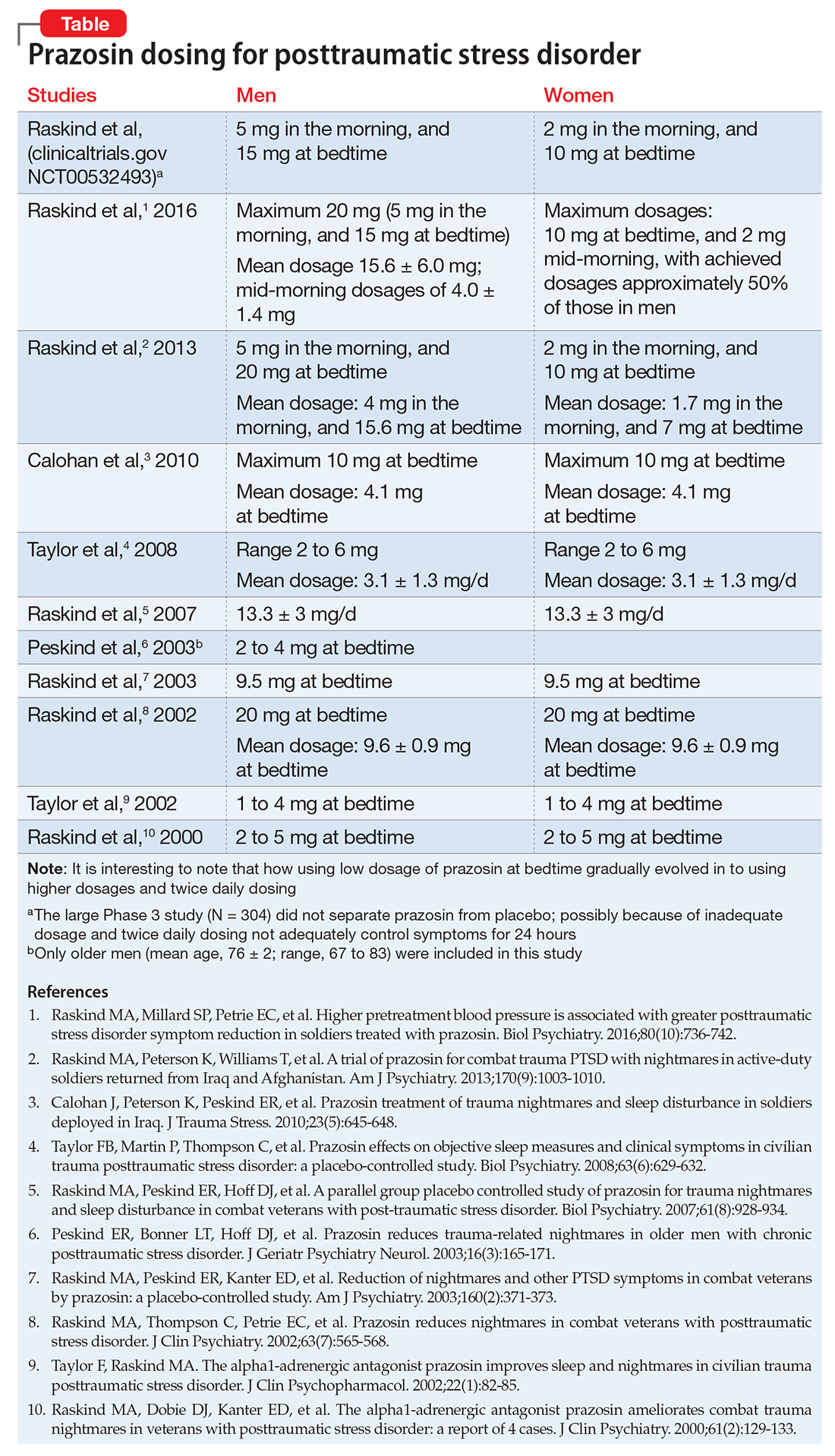

Prazosin, an alpha-1 (α-1) adrenergic antagonist that is FDA-approved for hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy, has been studied for treating nightmares in PTSD.7 Prazosin has shown efficacy for nightmares in PTSD and other daytime symptoms, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, and irritability.8 Several studies support the efficacy of prazosin in persons suffering from PTSD.9-11 Use of lower dosages in clinical trials might explain why prazosin did not separate from placebo in some studies. (See Table summarizing studies of prazosin dosing for PTSD.)

In a study of 12,844 veterans, the mean maximum prazosin dosage reached in the first year of treatment was 3.6 mg/d, and only 14% of patients reached the minimum Veterans Affairs recommended dosage of 6 mg/d.17 The most recent (March 2009) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend prazosin, 3 to 15 mg at bedtime.18

Prazosin has a short half-life of 2 to 3 hours and duration of action of 6 to 10 hours. Therefore, its use is limited to 2 or 3 times daily dosing. Higher (30 to 50 mg) and more frequent (2 to 3 times per day) dosages8,12,13 might be needed because of the drug’s short half-life.

Doxazosin. Another α-1 adrenergic drug, doxazosin, 8 to 16 mg/d, has shown benefit for PTSD as well.14,15 Doxazosin, which has a longer half-life (16 to 30 hours), requires only once-daily dosing.16 The most common side effects of prazosin and doxazosin are dizziness, headache, and drowsiness; syncope has been reported but is rare.

Prazosin and doxazosin also are used to treat substance abuse, such as alcohol use disorder19-21 and cocaine use disorder.22,23 This “two birds with one stone” approach could become more common in clinical practice.

Until a major breakthrough in PTSD treatment emerges, prazosin and doxazosin, although off-label, are reasonable treatment approaches.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.

1. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428.

2. National Comorbidity Survey. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed February 10, 2017.

3. Gradus JL. Epidemiology of PTSD. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/PTSD-overview/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp. Updated February 23, 2016. Accessed February 13, 2017.

4. Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, et al. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1401-1425.

5. Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Petry NM. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and substance use: emerging research on correlates, mechanisms, and treatments-introduction to the special issue. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):713-719.

6. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184-1190.

7. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129-133.

8. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

9. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Hoff DJ, et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(8):928-934.

10. Taylor FB, Martin P, Thompson C, et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):629-632.

11. Raskind MA, Millard SP, Petrie EC, et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater posttraumatic stress disorder symptom reduction in soldiers treated with prazosin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(10):736-742.

12. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43-47.

13. Vaishnav M, Patel V, Varghese SP, et al. Fludrocortisone in posttraumatic stress disorder: effective for symptoms and prazosin-induced hypotension. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01676.

14. Rodgman C, Verrico CD, Holst M, et al. Doxazosin XL reduces symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with PTSD: a pilot clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):e561-e565.

15. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an α-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26-31.

16. Smith C, Koola MM. Evidence for using doxazosin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(9):553-555.

17. Alexander B, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, et al. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of prazosin: a potential missed opportunity for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):e639-e644.

18. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd-watch.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2017.

19. Qazi H, Wijegunaratne H, Savajiyani R, et al. Naltrexone and prazosin combination for posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4). doi: 10.4088/PCC.14l01638.

20. Simpson TL, Malte CA, Dietel B, et al. A pilot trial of prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, for comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):808-817.

21. Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the α1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904-914.

22. Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):66-70.

23. Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854.