User login

PARP inhibitors: New developments in ovarian cancer treatment

Ovarian cancer remains the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer worldwide and one of the five leading causes of death from cancer in women in the United States. In addition to surgery, treatment consists of combination platinum and taxane chemotherapy that offers a high response rate; however, a majority of women will develop persistent or recurrent disease.

A clinical practice statement released by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology in October 2014 states that “women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancers should receive genetic counseling and be offered genetic testing, even in the absence of family history.” Patients should be informed that this genetic testing serves to prognosticate, inform about personal and familial cancer risk, but also aids in choices of novel therapeutic agents, specifically Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Genetic involvement of BRCA

A small proportion of ovarian cancers are attributable to genetic mutations, with approximately 10%-15% of cases caused by germline mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2. BRCA1 deleterious mutations confer an ovarian cancer risk of approximately 39%-46%; and the risk of ovarian cancer is roughly 12%-20% for patients with BRCA2 deleterious mutations. As a tumor suppressor gene, BRCA is involved in the DNA repair process. Specifically, it is involved in homologous recombination (a form of double-stranded DNA repair mechanism). Thus, cells with defective BRCA proteins cannot repair double-stranded breaks (DSB) in DNA.

The homologous recombination pathway is complex and involves a number of genes. Deficiencies in this pathway confer a sensitivity to PARP inhibition. Tumors that share dysfunction in the homologous recombination pathway, but do not contain mutations in the BRCA gene, are classified as tumors with “BRCAness.”

Generally, the inheritance of a defective BRCA1 or BRCA2 allele (a germline mutation) alone is not enough to cause the development of cancer. Instead, once the second, functioning allele becomes nonfunctional, cancer can arise through an accumulation of mutations in the genetic code.

Furthermore, regardless of germline BRCA status, cancers have high rates of genetic mutation. As a result of the mutation rate, tumors can develop noninherited, noninheritable alterations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes (a somatic mutation).

Mechanism of PARP inhibitor activity

The PARP family of enzymes hold a vital role in the repair of DNA and the stabilization of the human genome through the repair of single-stranded breaks (SSB) in DNA. PARP inhibitors were originally developed as a chemosensitizing agent for other cytotoxic agents. It was only later discovered that ovarian cancer cells and mouse models that were deficient in BRCA proteins were especially sensitive to PARP inhibition. Eventually, the clinical development strategy became to employ PARP inhibitors in selected patients with BRCA mutations.

As previously mentioned, cells deficient in the tumor suppressor genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) have an inability to repair DSBs. Inhibiting PARP enzymes will therefore cause an increase in SSB. During cell replication, these SSBs are converted to DSBs. Ultimately, the accumulation of DSBs leads to cell death. The concept that these two deficiencies – which alone are nonlethal – can be combined to induce cell death is described as synthetic lethality.

The exact mechanism through which PARP inhibitors function is not fully understood; however, four models currently exist to explain how PARP inhibitors instigate synthetic lethality. PARP inhibitors may block base excision repair mechanisms, trap PARP enzymes on damaged DNA, reduce the affinity of functioning BRCA enzymes to damaged DNA, and suppress nonhomologous end joining repair mechanisms.1

FDA approval of PARP inhibitors

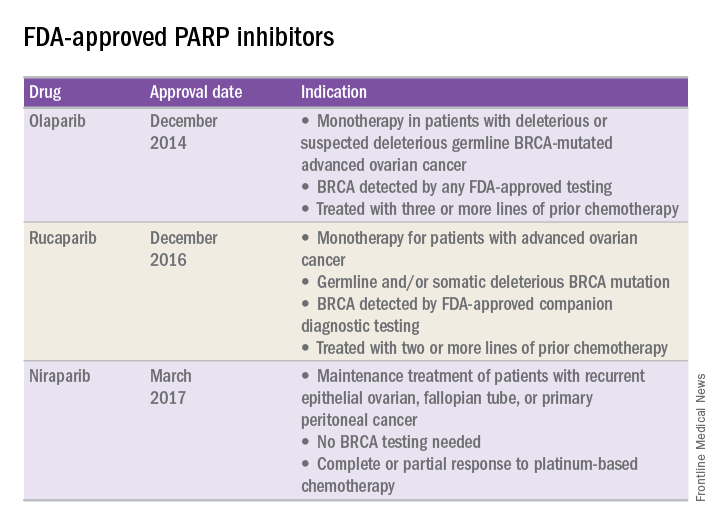

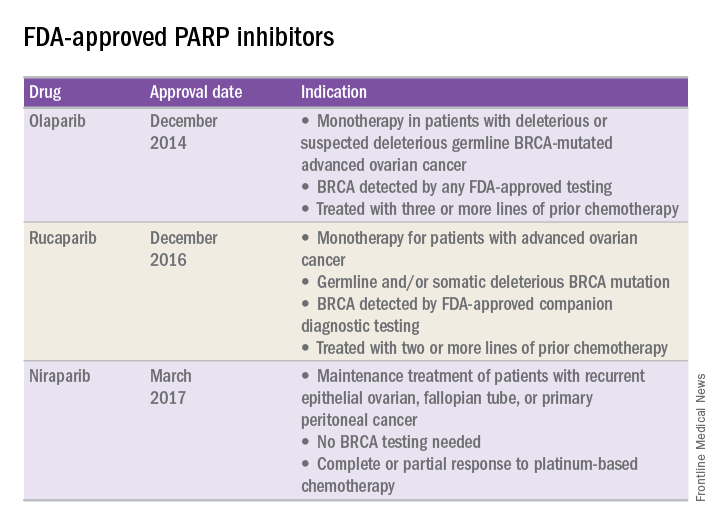

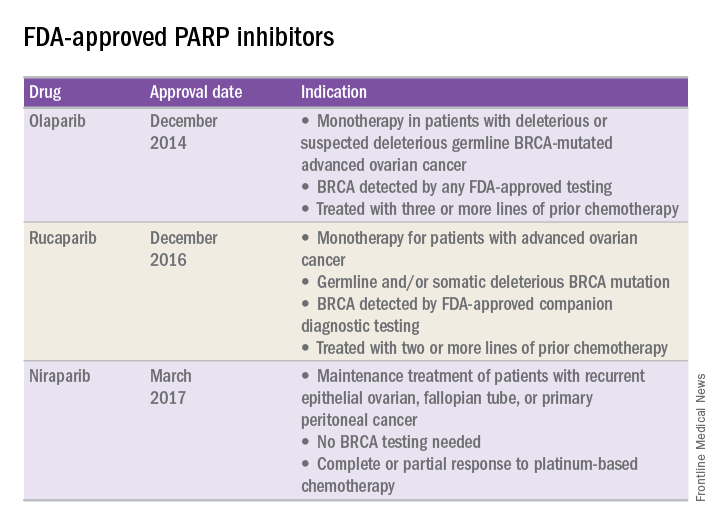

In recent years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved three PARP inhibitors in the treatment of ovarian cancer in slightly different clinical scenarios.

Olaparib was tested in a trial of 193 patients who harbored a deleterious or suspected deleterious germline BRCA-associated ovarian cancer who had received prior therapies.2 Overall, the response rate in this population was 41% (95% confidence interval, 28-54) with a median duration of response of 8.0 months. These results led to the FDA approval of olaparib for ovarian cancer treatment as fourth-line therapy in patients with BRCA mutations.

Two separate trials using rucaparib showed an overall response rate of 54% and a duration of response of 9.2 months.3,4 These early results allowed the FDA to grant accelerated approval to another PARP inhibitor for use in ovarian cancer.

More recently, a phase III trial of niraparib maintenance therapy versus placebo enrolled 553 women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.5 Women with germline BRCA mutations had recurrence-free intervals of 21 months on niraparib, compared with 5.5 months for those on placebo. Even without germline BRCA mutations, women benefited from a recurrence-free interval of 9.3 months, compared with 3.9 months for placebo.

PARP inhibitors represent a novel targeted therapy for ovarian cancer, particularly those with deleterious germline or somatic BRCA mutations. When combined with genetic testing for BRCA mutations, PARP inhibitors represent an example of a predictive biomarker paired with a tailored therapeutic. Maturing data from ongoing trials will likely expand the opportunity to use PARP inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

References

1. Br J Cancer. 2016 Nov 8;115(10):1157-73.

2. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jan 20;33(3):244-50.

3. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Mar 6. pii: clincanres.2796.2016. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2796.

4. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Jan;18(1):75-87.

5. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2154-64.

Dr. Tran is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Ovarian cancer remains the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer worldwide and one of the five leading causes of death from cancer in women in the United States. In addition to surgery, treatment consists of combination platinum and taxane chemotherapy that offers a high response rate; however, a majority of women will develop persistent or recurrent disease.

A clinical practice statement released by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology in October 2014 states that “women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancers should receive genetic counseling and be offered genetic testing, even in the absence of family history.” Patients should be informed that this genetic testing serves to prognosticate, inform about personal and familial cancer risk, but also aids in choices of novel therapeutic agents, specifically Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Genetic involvement of BRCA

A small proportion of ovarian cancers are attributable to genetic mutations, with approximately 10%-15% of cases caused by germline mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2. BRCA1 deleterious mutations confer an ovarian cancer risk of approximately 39%-46%; and the risk of ovarian cancer is roughly 12%-20% for patients with BRCA2 deleterious mutations. As a tumor suppressor gene, BRCA is involved in the DNA repair process. Specifically, it is involved in homologous recombination (a form of double-stranded DNA repair mechanism). Thus, cells with defective BRCA proteins cannot repair double-stranded breaks (DSB) in DNA.

The homologous recombination pathway is complex and involves a number of genes. Deficiencies in this pathway confer a sensitivity to PARP inhibition. Tumors that share dysfunction in the homologous recombination pathway, but do not contain mutations in the BRCA gene, are classified as tumors with “BRCAness.”

Generally, the inheritance of a defective BRCA1 or BRCA2 allele (a germline mutation) alone is not enough to cause the development of cancer. Instead, once the second, functioning allele becomes nonfunctional, cancer can arise through an accumulation of mutations in the genetic code.

Furthermore, regardless of germline BRCA status, cancers have high rates of genetic mutation. As a result of the mutation rate, tumors can develop noninherited, noninheritable alterations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes (a somatic mutation).

Mechanism of PARP inhibitor activity

The PARP family of enzymes hold a vital role in the repair of DNA and the stabilization of the human genome through the repair of single-stranded breaks (SSB) in DNA. PARP inhibitors were originally developed as a chemosensitizing agent for other cytotoxic agents. It was only later discovered that ovarian cancer cells and mouse models that were deficient in BRCA proteins were especially sensitive to PARP inhibition. Eventually, the clinical development strategy became to employ PARP inhibitors in selected patients with BRCA mutations.

As previously mentioned, cells deficient in the tumor suppressor genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) have an inability to repair DSBs. Inhibiting PARP enzymes will therefore cause an increase in SSB. During cell replication, these SSBs are converted to DSBs. Ultimately, the accumulation of DSBs leads to cell death. The concept that these two deficiencies – which alone are nonlethal – can be combined to induce cell death is described as synthetic lethality.

The exact mechanism through which PARP inhibitors function is not fully understood; however, four models currently exist to explain how PARP inhibitors instigate synthetic lethality. PARP inhibitors may block base excision repair mechanisms, trap PARP enzymes on damaged DNA, reduce the affinity of functioning BRCA enzymes to damaged DNA, and suppress nonhomologous end joining repair mechanisms.1

FDA approval of PARP inhibitors

In recent years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved three PARP inhibitors in the treatment of ovarian cancer in slightly different clinical scenarios.

Olaparib was tested in a trial of 193 patients who harbored a deleterious or suspected deleterious germline BRCA-associated ovarian cancer who had received prior therapies.2 Overall, the response rate in this population was 41% (95% confidence interval, 28-54) with a median duration of response of 8.0 months. These results led to the FDA approval of olaparib for ovarian cancer treatment as fourth-line therapy in patients with BRCA mutations.

Two separate trials using rucaparib showed an overall response rate of 54% and a duration of response of 9.2 months.3,4 These early results allowed the FDA to grant accelerated approval to another PARP inhibitor for use in ovarian cancer.

More recently, a phase III trial of niraparib maintenance therapy versus placebo enrolled 553 women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.5 Women with germline BRCA mutations had recurrence-free intervals of 21 months on niraparib, compared with 5.5 months for those on placebo. Even without germline BRCA mutations, women benefited from a recurrence-free interval of 9.3 months, compared with 3.9 months for placebo.

PARP inhibitors represent a novel targeted therapy for ovarian cancer, particularly those with deleterious germline or somatic BRCA mutations. When combined with genetic testing for BRCA mutations, PARP inhibitors represent an example of a predictive biomarker paired with a tailored therapeutic. Maturing data from ongoing trials will likely expand the opportunity to use PARP inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

References

1. Br J Cancer. 2016 Nov 8;115(10):1157-73.

2. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jan 20;33(3):244-50.

3. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Mar 6. pii: clincanres.2796.2016. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2796.

4. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Jan;18(1):75-87.

5. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2154-64.

Dr. Tran is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Ovarian cancer remains the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer worldwide and one of the five leading causes of death from cancer in women in the United States. In addition to surgery, treatment consists of combination platinum and taxane chemotherapy that offers a high response rate; however, a majority of women will develop persistent or recurrent disease.

A clinical practice statement released by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology in October 2014 states that “women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancers should receive genetic counseling and be offered genetic testing, even in the absence of family history.” Patients should be informed that this genetic testing serves to prognosticate, inform about personal and familial cancer risk, but also aids in choices of novel therapeutic agents, specifically Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Genetic involvement of BRCA

A small proportion of ovarian cancers are attributable to genetic mutations, with approximately 10%-15% of cases caused by germline mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2. BRCA1 deleterious mutations confer an ovarian cancer risk of approximately 39%-46%; and the risk of ovarian cancer is roughly 12%-20% for patients with BRCA2 deleterious mutations. As a tumor suppressor gene, BRCA is involved in the DNA repair process. Specifically, it is involved in homologous recombination (a form of double-stranded DNA repair mechanism). Thus, cells with defective BRCA proteins cannot repair double-stranded breaks (DSB) in DNA.

The homologous recombination pathway is complex and involves a number of genes. Deficiencies in this pathway confer a sensitivity to PARP inhibition. Tumors that share dysfunction in the homologous recombination pathway, but do not contain mutations in the BRCA gene, are classified as tumors with “BRCAness.”

Generally, the inheritance of a defective BRCA1 or BRCA2 allele (a germline mutation) alone is not enough to cause the development of cancer. Instead, once the second, functioning allele becomes nonfunctional, cancer can arise through an accumulation of mutations in the genetic code.

Furthermore, regardless of germline BRCA status, cancers have high rates of genetic mutation. As a result of the mutation rate, tumors can develop noninherited, noninheritable alterations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes (a somatic mutation).

Mechanism of PARP inhibitor activity

The PARP family of enzymes hold a vital role in the repair of DNA and the stabilization of the human genome through the repair of single-stranded breaks (SSB) in DNA. PARP inhibitors were originally developed as a chemosensitizing agent for other cytotoxic agents. It was only later discovered that ovarian cancer cells and mouse models that were deficient in BRCA proteins were especially sensitive to PARP inhibition. Eventually, the clinical development strategy became to employ PARP inhibitors in selected patients with BRCA mutations.

As previously mentioned, cells deficient in the tumor suppressor genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) have an inability to repair DSBs. Inhibiting PARP enzymes will therefore cause an increase in SSB. During cell replication, these SSBs are converted to DSBs. Ultimately, the accumulation of DSBs leads to cell death. The concept that these two deficiencies – which alone are nonlethal – can be combined to induce cell death is described as synthetic lethality.

The exact mechanism through which PARP inhibitors function is not fully understood; however, four models currently exist to explain how PARP inhibitors instigate synthetic lethality. PARP inhibitors may block base excision repair mechanisms, trap PARP enzymes on damaged DNA, reduce the affinity of functioning BRCA enzymes to damaged DNA, and suppress nonhomologous end joining repair mechanisms.1

FDA approval of PARP inhibitors

In recent years, the Food and Drug Administration has approved three PARP inhibitors in the treatment of ovarian cancer in slightly different clinical scenarios.

Olaparib was tested in a trial of 193 patients who harbored a deleterious or suspected deleterious germline BRCA-associated ovarian cancer who had received prior therapies.2 Overall, the response rate in this population was 41% (95% confidence interval, 28-54) with a median duration of response of 8.0 months. These results led to the FDA approval of olaparib for ovarian cancer treatment as fourth-line therapy in patients with BRCA mutations.

Two separate trials using rucaparib showed an overall response rate of 54% and a duration of response of 9.2 months.3,4 These early results allowed the FDA to grant accelerated approval to another PARP inhibitor for use in ovarian cancer.

More recently, a phase III trial of niraparib maintenance therapy versus placebo enrolled 553 women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.5 Women with germline BRCA mutations had recurrence-free intervals of 21 months on niraparib, compared with 5.5 months for those on placebo. Even without germline BRCA mutations, women benefited from a recurrence-free interval of 9.3 months, compared with 3.9 months for placebo.

PARP inhibitors represent a novel targeted therapy for ovarian cancer, particularly those with deleterious germline or somatic BRCA mutations. When combined with genetic testing for BRCA mutations, PARP inhibitors represent an example of a predictive biomarker paired with a tailored therapeutic. Maturing data from ongoing trials will likely expand the opportunity to use PARP inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

References

1. Br J Cancer. 2016 Nov 8;115(10):1157-73.

2. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jan 20;33(3):244-50.

3. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Mar 6. pii: clincanres.2796.2016. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2796.

4. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Jan;18(1):75-87.

5. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2154-64.

Dr. Tran is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Pelvic organ prolapse: Effective treatments

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on pelvic organ prolapse.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material that is often tested on board exams. Earlier this year, ACOG released a revised Practice Bulletin (#176) updating its advice on the diagnosis and management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1 It is a well-written document summarizing most of the landmark articles published in the field of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following procedures is the most effective for a sexually-active patient with advanced prolapse?

A. Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS)

B. Uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS)

C. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP)

D. Colpocleisis

E. Hysteropexy

A randomized trial comparing SSLS and USLS found the two apical procedures with native tissue repair are equally effective with comparable functional and adverse outcomes (answers A and B are incorrect). However, randomized trials comparing SCP to SSLS show that SCP with synthetic mesh has the lowest recurrence rate for prolapse. Colpocleisis is done for patients who are not sexually active (answer D is incorrect). Hysteropexy is performed for patients who desire preservation of the uterus. There is less available evidence on safety and efficacy, compared with hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (answer E is incorrect)

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. SCP is the most effective prolapse repair technique.

2. USLS and SSLS fixation are equally effective when compared with one another.

3. Colpocleisis is a highly successful procedure for POP in patients who are not sexually active.

Literature summary

The lifetime risk for undergoing surgery for POP or stress incontinence is 20%. POP is the descent of one or more aspects of the vagina or uterus, which allows nearby organs to herniate into the vagina. POP should only be treated if it is symptomatic and bothersome for the patient. The pessary is an alternative to surgical treatment of prolapse.

Proven risk factors for POP are increased parity, vaginal delivery, age, obesity, chronic constipation, and certain congenital anomalies. A history should be taken to elucidate symptoms of prolapse, such as bulge, pressure, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. It is also important to find out how much the POP is affecting her quality of life. A physical exam is best performed with a split speculum, with bladder empty, while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. We recommend using the POP-Q system to grade the severity of prolapse. The tone of the pelvic floor muscle should also be evaluated (absent, weak, normal, or strong) during pelvic exam.

The minimum testing necessary for a patient with POP is urinalysis and a postvoid residual. A stress test with a full bladder should also be done with and without reduction of the prolapse. If you’re considering surgery and the patient has advanced prolapse and/or other complicating factors – such as obstructive symptoms or significant neurologic disorder – you should consider performing urodynamic testing as well.

Native tissue, suture-based reconstructive repairs of the vagina include apical procedures, such as SSLS and USLS, in addition to anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair. At 2-year follow-up, SSLS and USLS along with anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair are equally effective for treatment of prolapse with comparable functional and adverse outcomes. SCP is more effective than SSLS but the abdominal procedure (not laparoscopic) may be associated with more complications. Currently, there are no published randomized trials comparing minimally-invasive SCP to USLS, but one is underway (clinicaltrials.gov).

Other procedures for POP include obliterative procedures such as colpocleisis, which is highly effective for patients who do not desire future vaginal intercourse and also has low morbidity. Preservation of the uterus by hysteropexy procedures (either transvaginal or transabdominal) are also options for women desiring to preserve their uterus, but these procedures have little safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the procedure performed, routine intraoperative cystoscopy should be done to assure ureteral patency and to rule out injury to the lower urinary tract.

Some type of prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure – retropubic or Burch – may be done at the time of vaginal prolapse repair or abdominal prolapse repair, respectively, in order to reduce the chance of postoperative stress urinary incontinence in a patient without symptoms of stress incontinence. The exception to this is in a patient who has an elevated postvoid residual or someone with a prior anti-incontinence procedure without symptoms of stress urinary incontinence.

Practice tips

Finally, here are some precautions and words of advice about the following POP procedures:

- Neither synthetic nor biologic grafts should be used to augment posterior repairs as these do not improve outcomes.

- Transvaginal repair of rectocele is superior to the transanal repair techniques.

- Synthetic mesh augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall may improve anatomic outcomes, but this comes at a cost (more reoperations and higher rate of complications). Thus, surgeons performing these procedures should have specialized training and the patient should have a unique indication and must undergo proper consent as recommended by ACOG.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on pelvic organ prolapse.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material that is often tested on board exams. Earlier this year, ACOG released a revised Practice Bulletin (#176) updating its advice on the diagnosis and management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1 It is a well-written document summarizing most of the landmark articles published in the field of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following procedures is the most effective for a sexually-active patient with advanced prolapse?

A. Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS)

B. Uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS)

C. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP)

D. Colpocleisis

E. Hysteropexy

A randomized trial comparing SSLS and USLS found the two apical procedures with native tissue repair are equally effective with comparable functional and adverse outcomes (answers A and B are incorrect). However, randomized trials comparing SCP to SSLS show that SCP with synthetic mesh has the lowest recurrence rate for prolapse. Colpocleisis is done for patients who are not sexually active (answer D is incorrect). Hysteropexy is performed for patients who desire preservation of the uterus. There is less available evidence on safety and efficacy, compared with hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (answer E is incorrect)

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. SCP is the most effective prolapse repair technique.

2. USLS and SSLS fixation are equally effective when compared with one another.

3. Colpocleisis is a highly successful procedure for POP in patients who are not sexually active.

Literature summary

The lifetime risk for undergoing surgery for POP or stress incontinence is 20%. POP is the descent of one or more aspects of the vagina or uterus, which allows nearby organs to herniate into the vagina. POP should only be treated if it is symptomatic and bothersome for the patient. The pessary is an alternative to surgical treatment of prolapse.

Proven risk factors for POP are increased parity, vaginal delivery, age, obesity, chronic constipation, and certain congenital anomalies. A history should be taken to elucidate symptoms of prolapse, such as bulge, pressure, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. It is also important to find out how much the POP is affecting her quality of life. A physical exam is best performed with a split speculum, with bladder empty, while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. We recommend using the POP-Q system to grade the severity of prolapse. The tone of the pelvic floor muscle should also be evaluated (absent, weak, normal, or strong) during pelvic exam.

The minimum testing necessary for a patient with POP is urinalysis and a postvoid residual. A stress test with a full bladder should also be done with and without reduction of the prolapse. If you’re considering surgery and the patient has advanced prolapse and/or other complicating factors – such as obstructive symptoms or significant neurologic disorder – you should consider performing urodynamic testing as well.

Native tissue, suture-based reconstructive repairs of the vagina include apical procedures, such as SSLS and USLS, in addition to anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair. At 2-year follow-up, SSLS and USLS along with anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair are equally effective for treatment of prolapse with comparable functional and adverse outcomes. SCP is more effective than SSLS but the abdominal procedure (not laparoscopic) may be associated with more complications. Currently, there are no published randomized trials comparing minimally-invasive SCP to USLS, but one is underway (clinicaltrials.gov).

Other procedures for POP include obliterative procedures such as colpocleisis, which is highly effective for patients who do not desire future vaginal intercourse and also has low morbidity. Preservation of the uterus by hysteropexy procedures (either transvaginal or transabdominal) are also options for women desiring to preserve their uterus, but these procedures have little safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the procedure performed, routine intraoperative cystoscopy should be done to assure ureteral patency and to rule out injury to the lower urinary tract.

Some type of prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure – retropubic or Burch – may be done at the time of vaginal prolapse repair or abdominal prolapse repair, respectively, in order to reduce the chance of postoperative stress urinary incontinence in a patient without symptoms of stress incontinence. The exception to this is in a patient who has an elevated postvoid residual or someone with a prior anti-incontinence procedure without symptoms of stress urinary incontinence.

Practice tips

Finally, here are some precautions and words of advice about the following POP procedures:

- Neither synthetic nor biologic grafts should be used to augment posterior repairs as these do not improve outcomes.

- Transvaginal repair of rectocele is superior to the transanal repair techniques.

- Synthetic mesh augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall may improve anatomic outcomes, but this comes at a cost (more reoperations and higher rate of complications). Thus, surgeons performing these procedures should have specialized training and the patient should have a unique indication and must undergo proper consent as recommended by ACOG.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment of a six-part series that will review key concepts and articles that ob.gyns. can use to prepare for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maintenance of Certification examination. The series is adapted from Ob/Gyn Board Master (obgynboardmaster.com), an online board review course created by Erudyte. This month’s edition of the Board Corner focuses on pelvic organ prolapse.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ “Practice Bulletins” are important practice management guidelines for ob.gyn. clinicians. The Practice Bulletins are rich sources of material that is often tested on board exams. Earlier this year, ACOG released a revised Practice Bulletin (#176) updating its advice on the diagnosis and management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP).1 It is a well-written document summarizing most of the landmark articles published in the field of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. We recommend you read this bulletin and review this topic carefully.

Let’s begin with a possible medical board question: Which of the following procedures is the most effective for a sexually-active patient with advanced prolapse?

A. Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS)

B. Uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS)

C. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP)

D. Colpocleisis

E. Hysteropexy

A randomized trial comparing SSLS and USLS found the two apical procedures with native tissue repair are equally effective with comparable functional and adverse outcomes (answers A and B are incorrect). However, randomized trials comparing SCP to SSLS show that SCP with synthetic mesh has the lowest recurrence rate for prolapse. Colpocleisis is done for patients who are not sexually active (answer D is incorrect). Hysteropexy is performed for patients who desire preservation of the uterus. There is less available evidence on safety and efficacy, compared with hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (answer E is incorrect)

Key points

The key points to remember are:

1. SCP is the most effective prolapse repair technique.

2. USLS and SSLS fixation are equally effective when compared with one another.

3. Colpocleisis is a highly successful procedure for POP in patients who are not sexually active.

Literature summary

The lifetime risk for undergoing surgery for POP or stress incontinence is 20%. POP is the descent of one or more aspects of the vagina or uterus, which allows nearby organs to herniate into the vagina. POP should only be treated if it is symptomatic and bothersome for the patient. The pessary is an alternative to surgical treatment of prolapse.

Proven risk factors for POP are increased parity, vaginal delivery, age, obesity, chronic constipation, and certain congenital anomalies. A history should be taken to elucidate symptoms of prolapse, such as bulge, pressure, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or defecatory dysfunction. It is also important to find out how much the POP is affecting her quality of life. A physical exam is best performed with a split speculum, with bladder empty, while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. We recommend using the POP-Q system to grade the severity of prolapse. The tone of the pelvic floor muscle should also be evaluated (absent, weak, normal, or strong) during pelvic exam.

The minimum testing necessary for a patient with POP is urinalysis and a postvoid residual. A stress test with a full bladder should also be done with and without reduction of the prolapse. If you’re considering surgery and the patient has advanced prolapse and/or other complicating factors – such as obstructive symptoms or significant neurologic disorder – you should consider performing urodynamic testing as well.

Native tissue, suture-based reconstructive repairs of the vagina include apical procedures, such as SSLS and USLS, in addition to anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair. At 2-year follow-up, SSLS and USLS along with anterior colporrhaphy and posterior repair are equally effective for treatment of prolapse with comparable functional and adverse outcomes. SCP is more effective than SSLS but the abdominal procedure (not laparoscopic) may be associated with more complications. Currently, there are no published randomized trials comparing minimally-invasive SCP to USLS, but one is underway (clinicaltrials.gov).

Other procedures for POP include obliterative procedures such as colpocleisis, which is highly effective for patients who do not desire future vaginal intercourse and also has low morbidity. Preservation of the uterus by hysteropexy procedures (either transvaginal or transabdominal) are also options for women desiring to preserve their uterus, but these procedures have little safety and efficacy data. Regardless of the procedure performed, routine intraoperative cystoscopy should be done to assure ureteral patency and to rule out injury to the lower urinary tract.

Some type of prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure – retropubic or Burch – may be done at the time of vaginal prolapse repair or abdominal prolapse repair, respectively, in order to reduce the chance of postoperative stress urinary incontinence in a patient without symptoms of stress incontinence. The exception to this is in a patient who has an elevated postvoid residual or someone with a prior anti-incontinence procedure without symptoms of stress urinary incontinence.

Practice tips

Finally, here are some precautions and words of advice about the following POP procedures:

- Neither synthetic nor biologic grafts should be used to augment posterior repairs as these do not improve outcomes.

- Transvaginal repair of rectocele is superior to the transanal repair techniques.

- Synthetic mesh augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall may improve anatomic outcomes, but this comes at a cost (more reoperations and higher rate of complications). Thus, surgeons performing these procedures should have specialized training and the patient should have a unique indication and must undergo proper consent as recommended by ACOG.

Dr. Siddighi is editor-in-chief of the Ob/Gyn Board Master and director of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery and director of grand rounds at Loma Linda University Health in California. Ob.Gyn. News and Ob/Gyn Board Master are owned by the same parent company, Frontline Medical Communications.

Reference

Disease-Modifying Drug Treatment Before, During, and After Pregnancy in Women With MS

Treatment Before, During, and After Pregnancy

To evaluate treatment patterns before, during, and after pregnancy in women with MS and a live birth, Dr. Houtchens and colleagues used a US administrative claims database to conduct a retrospective analysis of women ages 18 to 65 with MS, a claim indicative of a live birth, and one-year continuous eligibility before and after pregnancy in the IMS Health Real World Data Adjudicated Claims US database from January 1, 2006, to June 30, 2015. Disease-modifying drug treatment was evaluated during the year prior to pregnancy (at three-month intervals), the three trimesters of pregnancy, puerperium (six weeks post-pregnancy), and one year post pregnancy (seven to 12 weeks post pregnancy and three to six, six to nine, and nine to 12 months post pregnancy). The researchers evaluated the proportion of women exposed to disease-modifying drug treatment during the 12 time periods. Results were also stratified by the number of relapses women experienced in the year prior to pregnancy.

Of 190,475 women with MS, 2,158 met eligibility criteria. Mean age was 30.26. Most women had commercial health insurance (98%) and were from the Midwest (32%), South (30%), or Northeast (29%) regions of the US.

The proportion of women with MS and a live birth treated with any disease-modifying drug was 20.48% at nine to 12 months pre-pregnancy, 21.46% at six to nine months pre-pregnancy, 20.62% at three to six months pre-pregnancy, and 17.75% at three months pre-pregnancy. During pregnancy, the proportion of women treated with a disease-modifying drug decreased to 12.05% during the first trimester and 1.90% during the second trimester, and then increased slightly to 2.97% during the third trimester. The proportion of women treated with disease-modifying drugs increased to 8.34% during puerperium, 12.93% during seven to 12 weeks post partum, 21.97% during three to six months post partum, 24.47% during six to nine months post partum, and 25.49% during nine to 12 months post partum. The majority of women (81.9%) had received disease-modifying drug treatment by six to nine months post partum. The proportion of women with disease-modifying drug treatment before and after pregnancy increased numerically with the number of relapses experienced before pregnancy.

Treatment After a Live Birth

In a separate analysis using the same cohort, Dr. Houtchens and colleagues looked closer at the time to initiation of disease-modifying drug treatment after a live birth in women with MS. Of the 2,094 women included in this analysis, the proportion with a live birth initiating a disease-modifying drug treatment within one year was 28.46%, and the proportion with no disease-modifying treatment within one year was 71.54%.

For those initiating a disease-modifying treatment within one year, mean time from live birth to first treatment was 118.98 days, and median time to first treatment was 93.50 days. A total of 16.11% received a disease-modifying drug less than 30 days after live birth, approximately half initiated a treatment within 90 days (47.82%), and three-quarters initiated a disease-modifying drug within six months (75.5%). The proportion of patients initiating treatment within one year after live birth increased with higher numbers of pre-pregnancy relapses (zero relapses, n = 441, 24.53%; one relapse, n = 108, 50.94%; two relapses, n = 33, 54.10%; three or more relapses, n = 14, 60.87%). The mean number of days until disease-modifying drug initiation for those receiving treatment within one year who had zero pre-pregnancy relapses was 123.57 (median, 99); one relapse, 107.95 (median, 80); two relapses, 120.76 (median, 98); and three or more relapses, 55.57 (median, 49.5). Patients who received disease-modifying drug treatment one year pre-pregnancy were more likely to receive treatment within one year after delivery, compared with patients without exposure to treatment in the year before pregnancy (72.58% vs 12.44%).

This study was supported by EMD Serono.

Treatment Before, During, and After Pregnancy

To evaluate treatment patterns before, during, and after pregnancy in women with MS and a live birth, Dr. Houtchens and colleagues used a US administrative claims database to conduct a retrospective analysis of women ages 18 to 65 with MS, a claim indicative of a live birth, and one-year continuous eligibility before and after pregnancy in the IMS Health Real World Data Adjudicated Claims US database from January 1, 2006, to June 30, 2015. Disease-modifying drug treatment was evaluated during the year prior to pregnancy (at three-month intervals), the three trimesters of pregnancy, puerperium (six weeks post-pregnancy), and one year post pregnancy (seven to 12 weeks post pregnancy and three to six, six to nine, and nine to 12 months post pregnancy). The researchers evaluated the proportion of women exposed to disease-modifying drug treatment during the 12 time periods. Results were also stratified by the number of relapses women experienced in the year prior to pregnancy.

Of 190,475 women with MS, 2,158 met eligibility criteria. Mean age was 30.26. Most women had commercial health insurance (98%) and were from the Midwest (32%), South (30%), or Northeast (29%) regions of the US.

The proportion of women with MS and a live birth treated with any disease-modifying drug was 20.48% at nine to 12 months pre-pregnancy, 21.46% at six to nine months pre-pregnancy, 20.62% at three to six months pre-pregnancy, and 17.75% at three months pre-pregnancy. During pregnancy, the proportion of women treated with a disease-modifying drug decreased to 12.05% during the first trimester and 1.90% during the second trimester, and then increased slightly to 2.97% during the third trimester. The proportion of women treated with disease-modifying drugs increased to 8.34% during puerperium, 12.93% during seven to 12 weeks post partum, 21.97% during three to six months post partum, 24.47% during six to nine months post partum, and 25.49% during nine to 12 months post partum. The majority of women (81.9%) had received disease-modifying drug treatment by six to nine months post partum. The proportion of women with disease-modifying drug treatment before and after pregnancy increased numerically with the number of relapses experienced before pregnancy.

Treatment After a Live Birth

In a separate analysis using the same cohort, Dr. Houtchens and colleagues looked closer at the time to initiation of disease-modifying drug treatment after a live birth in women with MS. Of the 2,094 women included in this analysis, the proportion with a live birth initiating a disease-modifying drug treatment within one year was 28.46%, and the proportion with no disease-modifying treatment within one year was 71.54%.

For those initiating a disease-modifying treatment within one year, mean time from live birth to first treatment was 118.98 days, and median time to first treatment was 93.50 days. A total of 16.11% received a disease-modifying drug less than 30 days after live birth, approximately half initiated a treatment within 90 days (47.82%), and three-quarters initiated a disease-modifying drug within six months (75.5%). The proportion of patients initiating treatment within one year after live birth increased with higher numbers of pre-pregnancy relapses (zero relapses, n = 441, 24.53%; one relapse, n = 108, 50.94%; two relapses, n = 33, 54.10%; three or more relapses, n = 14, 60.87%). The mean number of days until disease-modifying drug initiation for those receiving treatment within one year who had zero pre-pregnancy relapses was 123.57 (median, 99); one relapse, 107.95 (median, 80); two relapses, 120.76 (median, 98); and three or more relapses, 55.57 (median, 49.5). Patients who received disease-modifying drug treatment one year pre-pregnancy were more likely to receive treatment within one year after delivery, compared with patients without exposure to treatment in the year before pregnancy (72.58% vs 12.44%).

This study was supported by EMD Serono.

Treatment Before, During, and After Pregnancy

To evaluate treatment patterns before, during, and after pregnancy in women with MS and a live birth, Dr. Houtchens and colleagues used a US administrative claims database to conduct a retrospective analysis of women ages 18 to 65 with MS, a claim indicative of a live birth, and one-year continuous eligibility before and after pregnancy in the IMS Health Real World Data Adjudicated Claims US database from January 1, 2006, to June 30, 2015. Disease-modifying drug treatment was evaluated during the year prior to pregnancy (at three-month intervals), the three trimesters of pregnancy, puerperium (six weeks post-pregnancy), and one year post pregnancy (seven to 12 weeks post pregnancy and three to six, six to nine, and nine to 12 months post pregnancy). The researchers evaluated the proportion of women exposed to disease-modifying drug treatment during the 12 time periods. Results were also stratified by the number of relapses women experienced in the year prior to pregnancy.

Of 190,475 women with MS, 2,158 met eligibility criteria. Mean age was 30.26. Most women had commercial health insurance (98%) and were from the Midwest (32%), South (30%), or Northeast (29%) regions of the US.

The proportion of women with MS and a live birth treated with any disease-modifying drug was 20.48% at nine to 12 months pre-pregnancy, 21.46% at six to nine months pre-pregnancy, 20.62% at three to six months pre-pregnancy, and 17.75% at three months pre-pregnancy. During pregnancy, the proportion of women treated with a disease-modifying drug decreased to 12.05% during the first trimester and 1.90% during the second trimester, and then increased slightly to 2.97% during the third trimester. The proportion of women treated with disease-modifying drugs increased to 8.34% during puerperium, 12.93% during seven to 12 weeks post partum, 21.97% during three to six months post partum, 24.47% during six to nine months post partum, and 25.49% during nine to 12 months post partum. The majority of women (81.9%) had received disease-modifying drug treatment by six to nine months post partum. The proportion of women with disease-modifying drug treatment before and after pregnancy increased numerically with the number of relapses experienced before pregnancy.

Treatment After a Live Birth

In a separate analysis using the same cohort, Dr. Houtchens and colleagues looked closer at the time to initiation of disease-modifying drug treatment after a live birth in women with MS. Of the 2,094 women included in this analysis, the proportion with a live birth initiating a disease-modifying drug treatment within one year was 28.46%, and the proportion with no disease-modifying treatment within one year was 71.54%.

For those initiating a disease-modifying treatment within one year, mean time from live birth to first treatment was 118.98 days, and median time to first treatment was 93.50 days. A total of 16.11% received a disease-modifying drug less than 30 days after live birth, approximately half initiated a treatment within 90 days (47.82%), and three-quarters initiated a disease-modifying drug within six months (75.5%). The proportion of patients initiating treatment within one year after live birth increased with higher numbers of pre-pregnancy relapses (zero relapses, n = 441, 24.53%; one relapse, n = 108, 50.94%; two relapses, n = 33, 54.10%; three or more relapses, n = 14, 60.87%). The mean number of days until disease-modifying drug initiation for those receiving treatment within one year who had zero pre-pregnancy relapses was 123.57 (median, 99); one relapse, 107.95 (median, 80); two relapses, 120.76 (median, 98); and three or more relapses, 55.57 (median, 49.5). Patients who received disease-modifying drug treatment one year pre-pregnancy were more likely to receive treatment within one year after delivery, compared with patients without exposure to treatment in the year before pregnancy (72.58% vs 12.44%).

This study was supported by EMD Serono.

CAR T cells elicit durable, potent responses in kids with EM relapse of ALL

CHICAGO—Outcomes for pediatric patients with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are dismal, with the probability of event-free survival ranging from 15% to 70% after a first relapse to 15% to 20% after a second relapse.

“So novel therapies are obviously urgently needed,” Mala Kiran Talekar, MD, of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, affirmed. “And herein comes the role of CAR T cells as a breakthrough therapy for relapsed/refractory pediatric ALL.”

She presented the outcome of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in pediatric patients with non-CNS extramedullary (EM) relapse at the ASCO 2017 Annual meeting as abstract 10507.

The investigators had drawn the patient population for this analysis from 2 CAR studies, CTL019 and CTL119.

CTL019, which had already been completed, employed a murine CAR, and CTL119 is ongoing and uses a humanized CAR.

Of the 60 patients enrolled in CTL019, 56 (93%) achieved a complete response (CR) at day 28, and 100% had a CNS remission. Their 12-month overall survival (OS) was 79%.

“[K]eep in mind, when the study first started,” Dr Talekar said, “the patient population that had been referred to us was patients who had suffered a second or greater relapse or had been refractory to forms of treatment available to them, and the majority had been refractory to multiple therapies.”

The humanized CAR study, CTL119, is divided into 2 cohorts—one with CAR-naïve patients (n=22) and the other a CAR-retreatment arm (n=15) with patients who had received previous CAR therapy and relapsed.

Dr Talekar explained that the humanized CAR was made with the intention of decreasing rejection or loss of persistence of the T cells related to murine antigenicity.

Nine patients (60%) in the CAR-retreatment arm achieved a CR at day 28, and at 6 months, 78% experienced relapse-free survival (RFS) with a median follow-up of 12 months.

All of the CAR-naïve patients achieved CR at day 28, with 86% achieving RFS at 6 months, with a median follow-up of 10 months.

ALL with EM involvement

The investigators identified 10 pediatric patients treated in the murine (n=6) or humanized (n=4) trials who had received CAR therapy for isolated extramedullary disease or for combined bone marrow extramedullary (BM/EM) relapse of ALL.

They defined EM relapse as involvement of a non-CNS site confirmed by imaging with or without pathology within 12 months of CAR T-cell infusion. After infusion, patients had diagnostic imaging performed at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Of the 10 patients, 5 had active EM involvement at the time of infusion, 2 had isolated EM relapse—1 with parotid and multifocal bony lesions and 1 with testis and sinus lesions—and 5 had multiple sites of EM relapse.

The patients had 2 to 4 prior ALL relapses, 2 had prior local radiation to the EM site, and all 10 had received prior bone marrow transplants.

Three patients had an MLL rearrangement, 1 had hypodiploid ALL, and 1 had trisomy 21.

Nine of the 10 patients achieved MRD-negative CR at day 28.

One patient was not evaluable because his disease progressed within 2 weeks of CAR therapy in both the bone marrow and EM site. He died 6 weeks after the infusion.

Five patients evaluated by serial imaging had objective responses. Two had no evidence of EM disease by day 28, 2 had resolution by 3 months, and 1 had continued decrease in the size of her uterine mass at 3 and 6 months. She underwent hysterectomy at 8 months with no evidence of disease on pathology.

Four patients with a prior history of skin or testicular involvement had no evidence of disease by exam at day 28.

Three of the 9 patients relapsed with CD19+ disease. One had skin/medullary involvement and died at 38 months after CAR T-cell infusion. And 2 had medullary disease: 1 died at 17 months and 1 is alive at 28 months.

The remaining 6 patients are alive and well at a median follow-up of 10 months (range, 3 – 16 months) without recurrence of disease.

The investigators therefore concluded that single agent CAR T-cell immunotherapy can induce potent and durable response in patients with EM relapse of their ALL. ![]()

CHICAGO—Outcomes for pediatric patients with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are dismal, with the probability of event-free survival ranging from 15% to 70% after a first relapse to 15% to 20% after a second relapse.

“So novel therapies are obviously urgently needed,” Mala Kiran Talekar, MD, of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, affirmed. “And herein comes the role of CAR T cells as a breakthrough therapy for relapsed/refractory pediatric ALL.”

She presented the outcome of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in pediatric patients with non-CNS extramedullary (EM) relapse at the ASCO 2017 Annual meeting as abstract 10507.

The investigators had drawn the patient population for this analysis from 2 CAR studies, CTL019 and CTL119.

CTL019, which had already been completed, employed a murine CAR, and CTL119 is ongoing and uses a humanized CAR.

Of the 60 patients enrolled in CTL019, 56 (93%) achieved a complete response (CR) at day 28, and 100% had a CNS remission. Their 12-month overall survival (OS) was 79%.

“[K]eep in mind, when the study first started,” Dr Talekar said, “the patient population that had been referred to us was patients who had suffered a second or greater relapse or had been refractory to forms of treatment available to them, and the majority had been refractory to multiple therapies.”

The humanized CAR study, CTL119, is divided into 2 cohorts—one with CAR-naïve patients (n=22) and the other a CAR-retreatment arm (n=15) with patients who had received previous CAR therapy and relapsed.

Dr Talekar explained that the humanized CAR was made with the intention of decreasing rejection or loss of persistence of the T cells related to murine antigenicity.

Nine patients (60%) in the CAR-retreatment arm achieved a CR at day 28, and at 6 months, 78% experienced relapse-free survival (RFS) with a median follow-up of 12 months.

All of the CAR-naïve patients achieved CR at day 28, with 86% achieving RFS at 6 months, with a median follow-up of 10 months.

ALL with EM involvement

The investigators identified 10 pediatric patients treated in the murine (n=6) or humanized (n=4) trials who had received CAR therapy for isolated extramedullary disease or for combined bone marrow extramedullary (BM/EM) relapse of ALL.

They defined EM relapse as involvement of a non-CNS site confirmed by imaging with or without pathology within 12 months of CAR T-cell infusion. After infusion, patients had diagnostic imaging performed at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Of the 10 patients, 5 had active EM involvement at the time of infusion, 2 had isolated EM relapse—1 with parotid and multifocal bony lesions and 1 with testis and sinus lesions—and 5 had multiple sites of EM relapse.

The patients had 2 to 4 prior ALL relapses, 2 had prior local radiation to the EM site, and all 10 had received prior bone marrow transplants.

Three patients had an MLL rearrangement, 1 had hypodiploid ALL, and 1 had trisomy 21.

Nine of the 10 patients achieved MRD-negative CR at day 28.

One patient was not evaluable because his disease progressed within 2 weeks of CAR therapy in both the bone marrow and EM site. He died 6 weeks after the infusion.

Five patients evaluated by serial imaging had objective responses. Two had no evidence of EM disease by day 28, 2 had resolution by 3 months, and 1 had continued decrease in the size of her uterine mass at 3 and 6 months. She underwent hysterectomy at 8 months with no evidence of disease on pathology.

Four patients with a prior history of skin or testicular involvement had no evidence of disease by exam at day 28.

Three of the 9 patients relapsed with CD19+ disease. One had skin/medullary involvement and died at 38 months after CAR T-cell infusion. And 2 had medullary disease: 1 died at 17 months and 1 is alive at 28 months.

The remaining 6 patients are alive and well at a median follow-up of 10 months (range, 3 – 16 months) without recurrence of disease.

The investigators therefore concluded that single agent CAR T-cell immunotherapy can induce potent and durable response in patients with EM relapse of their ALL. ![]()

CHICAGO—Outcomes for pediatric patients with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are dismal, with the probability of event-free survival ranging from 15% to 70% after a first relapse to 15% to 20% after a second relapse.

“So novel therapies are obviously urgently needed,” Mala Kiran Talekar, MD, of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, affirmed. “And herein comes the role of CAR T cells as a breakthrough therapy for relapsed/refractory pediatric ALL.”

She presented the outcome of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in pediatric patients with non-CNS extramedullary (EM) relapse at the ASCO 2017 Annual meeting as abstract 10507.

The investigators had drawn the patient population for this analysis from 2 CAR studies, CTL019 and CTL119.

CTL019, which had already been completed, employed a murine CAR, and CTL119 is ongoing and uses a humanized CAR.

Of the 60 patients enrolled in CTL019, 56 (93%) achieved a complete response (CR) at day 28, and 100% had a CNS remission. Their 12-month overall survival (OS) was 79%.

“[K]eep in mind, when the study first started,” Dr Talekar said, “the patient population that had been referred to us was patients who had suffered a second or greater relapse or had been refractory to forms of treatment available to them, and the majority had been refractory to multiple therapies.”

The humanized CAR study, CTL119, is divided into 2 cohorts—one with CAR-naïve patients (n=22) and the other a CAR-retreatment arm (n=15) with patients who had received previous CAR therapy and relapsed.

Dr Talekar explained that the humanized CAR was made with the intention of decreasing rejection or loss of persistence of the T cells related to murine antigenicity.

Nine patients (60%) in the CAR-retreatment arm achieved a CR at day 28, and at 6 months, 78% experienced relapse-free survival (RFS) with a median follow-up of 12 months.

All of the CAR-naïve patients achieved CR at day 28, with 86% achieving RFS at 6 months, with a median follow-up of 10 months.

ALL with EM involvement

The investigators identified 10 pediatric patients treated in the murine (n=6) or humanized (n=4) trials who had received CAR therapy for isolated extramedullary disease or for combined bone marrow extramedullary (BM/EM) relapse of ALL.

They defined EM relapse as involvement of a non-CNS site confirmed by imaging with or without pathology within 12 months of CAR T-cell infusion. After infusion, patients had diagnostic imaging performed at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Of the 10 patients, 5 had active EM involvement at the time of infusion, 2 had isolated EM relapse—1 with parotid and multifocal bony lesions and 1 with testis and sinus lesions—and 5 had multiple sites of EM relapse.

The patients had 2 to 4 prior ALL relapses, 2 had prior local radiation to the EM site, and all 10 had received prior bone marrow transplants.

Three patients had an MLL rearrangement, 1 had hypodiploid ALL, and 1 had trisomy 21.

Nine of the 10 patients achieved MRD-negative CR at day 28.

One patient was not evaluable because his disease progressed within 2 weeks of CAR therapy in both the bone marrow and EM site. He died 6 weeks after the infusion.

Five patients evaluated by serial imaging had objective responses. Two had no evidence of EM disease by day 28, 2 had resolution by 3 months, and 1 had continued decrease in the size of her uterine mass at 3 and 6 months. She underwent hysterectomy at 8 months with no evidence of disease on pathology.

Four patients with a prior history of skin or testicular involvement had no evidence of disease by exam at day 28.

Three of the 9 patients relapsed with CD19+ disease. One had skin/medullary involvement and died at 38 months after CAR T-cell infusion. And 2 had medullary disease: 1 died at 17 months and 1 is alive at 28 months.

The remaining 6 patients are alive and well at a median follow-up of 10 months (range, 3 – 16 months) without recurrence of disease.

The investigators therefore concluded that single agent CAR T-cell immunotherapy can induce potent and durable response in patients with EM relapse of their ALL. ![]()

Azacitidine alone comparable to AZA combos for most MDS patients

A 3-arm phase 2 study of azacitidine alone or in combination with lenalidomide or vorinostat in patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) has shown the combination therapies to have similar overall response rates (ORR) to azacitidine monotherapy. Based on these findings, investigators did not choose either combination arm for phase 3 testing of overall survival.

However, patients with CMML treated with the azacitidine-lenalidomide combination had twice the ORR compared with azacitidine monotherapy, they reported.

And patients with certain mutations, such as DNMT3A, BCOR, and NRAS, had higher overall response rates, although only those with the DNMT3A mutation were significant.

Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology on behalf of the North American Intergroup Study SWOG S117.

Doses of azacitidine were the same for monotherapy and combination arms: 75 mg/m2/day intravenously or subcutaneously on days 1 to 7 of a 28-day cycle.

Patients in the lenalidomide arm received 10 mg/day orally of that drug on days 1 to 21, and patients in the vorinostat arm received 300 mg twice daily orally on days 3 to 9.

Patient characteristics

Patients had MDS of IPSS Intermediate-2 or higher or bone marrow blasts 5% or greater. Patients with CMML had fewer than 20% blasts.

The investigators randomized 277 patients to receive either azacitidine alone (n=92), azacitidine plus lenalidomide (n=93), or azacitidine plus vorinostat (n=92).

Patients were a median age of 70 years (range, 28 to 93). Eighty-five patients (31%) were female, 53 (19%) had CMML, and 18 (6%) had treatment-related MDS. More than half the patients were transfusion-dependent at baseline.

Baseline characteristics were similar across the 3 arms. The investigators noted that the baseline characteristics were also similar across the 90 centers participating in the study, whether they were an MDS Center of Excellence or a high-volume center.

Adverse events

For the most part, therapy-related adverse events were similar across the arms.

Rates of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia and infection and infestations were similar for all 3 cohorts: 89% for azaciditine monotherapy, 91% for the lenalidomide combination, and 91% for the vorinostat combination.

However, the vorinostat arm had more grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal toxicities (14 patients, 15%) compared with the monotherapy arm (4 patients, 4%), P=0.02.

And patients receiving lenalidomide experienced more grade 3 or higher rash (14 patients, 16%) compared with patients receiving monotherapy (3 patients, 3%), P=0.005.

Patients in the combination arms stopped therapy at significantly higher rates than the monotherapy arm. Eight percent of patients receiving monotherapy stopped treatment compared with 20% in the lenalidomide arm and 21% in the vorinostat arm.

Patients in the combination arms also had more dose modifications not specified in the protocol than those in the monotherapy arm. Twenty-four percent receiving azacitidine monotherapy had non-protocol defined dose modifications, compared with 43% in the lenalidomide arm and 42% in the vorinostat arm.

Responses

The ORR for the entire study population was 38%.

Patients in the monotherapy arm had an ORR of 38%, those in the lenalidomide arm, 49%, and those in the vorinostate arm, 27%. Neither arm achieved significance compared with the monotherapy arm.

Patients who were treatment-naïve in the lenalidomide arm had a somewhat improved ORR compared with monotherapy, P=0.08.

The median duration of response for all cohorts was 15 months: 10 months for monotherapy, 14 months for lenalidomide, and 18 months for vorinostat.

Patients who were able to remain on therapy for 6 months or more in the lenalidomide arm achieved a higher ORR of 87% compared with monotherapy (62%, P=0.01). However, there was no difference in response duration with longer therapy.

The median overall survival (OS) was 17 months for all patients, 15 months for patients in the monotherapy group, 19 months for those in the lenalidomide arm, and 17 months for those in the vorinostat group.

CMML patients had similar OS across treatment arms, with the median not yet reached for patients in the monotherapy arm.

Subgroup responses

Patients with CMML in the lenalidomide arm had a significantly higher ORR than CMML patients in the monotherapy arm, 68% and 28%, respectively (P=0.02).

Median duration of response for CMML patients was 19 months, with no differences between the arms.

The investigators observed no differences in ORR for therapy-related MDS, IPSS subgroups, transfusion-dependent patients, or allogeneic transplant rates.

However, they noted ORR was better for patients with chromosome 5 abnormality regardless of treatment arm than for those without the abnormality (odds ratio, 2.17, P=0.008).

One hundred thirteen patients had mutational data available. They had a median number of 2 mutations (range, 0 to 7), with the most common being ASXL1 (n = 31), TET2 (n = 26), SRSF2 (n = 23), TP53 (n = 22), RUNX1 (n = 21), and U2AF1 (n = 19).

Patients with DNMT3A mutation had a significantly higher ORR than for patients without mutations, 67% and 34%, respectively P=0.025).

Patients with BCOR and NRAS mutations had numerically higher, but non-significant, ORR than non-mutated patients. Patients with BCOR mutation had a 57% ORR compared with 34% for non-mutated patients (P=0.23). Patients with NRAS mutation had a 60% ORR compared with 36% for non-mutated patients (P=0.28).

Patients with mutations in TET2 (P = .046) and TP53 (P = .003) had a worse response duration than those without mutations.

Response duration was significantly better with fewer mutations. For 2 or more mutations, the hazard ration was 6.86 versus no mutations (P=0.01).

The investigators believed under-dosing may have compromised response and survival in the combination arms. They suggested that studies focused on the subgroups that seemed to benefit from the combinations should be conducted. ![]()

A 3-arm phase 2 study of azacitidine alone or in combination with lenalidomide or vorinostat in patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) has shown the combination therapies to have similar overall response rates (ORR) to azacitidine monotherapy. Based on these findings, investigators did not choose either combination arm for phase 3 testing of overall survival.

However, patients with CMML treated with the azacitidine-lenalidomide combination had twice the ORR compared with azacitidine monotherapy, they reported.

And patients with certain mutations, such as DNMT3A, BCOR, and NRAS, had higher overall response rates, although only those with the DNMT3A mutation were significant.

Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology on behalf of the North American Intergroup Study SWOG S117.

Doses of azacitidine were the same for monotherapy and combination arms: 75 mg/m2/day intravenously or subcutaneously on days 1 to 7 of a 28-day cycle.

Patients in the lenalidomide arm received 10 mg/day orally of that drug on days 1 to 21, and patients in the vorinostat arm received 300 mg twice daily orally on days 3 to 9.

Patient characteristics

Patients had MDS of IPSS Intermediate-2 or higher or bone marrow blasts 5% or greater. Patients with CMML had fewer than 20% blasts.

The investigators randomized 277 patients to receive either azacitidine alone (n=92), azacitidine plus lenalidomide (n=93), or azacitidine plus vorinostat (n=92).

Patients were a median age of 70 years (range, 28 to 93). Eighty-five patients (31%) were female, 53 (19%) had CMML, and 18 (6%) had treatment-related MDS. More than half the patients were transfusion-dependent at baseline.

Baseline characteristics were similar across the 3 arms. The investigators noted that the baseline characteristics were also similar across the 90 centers participating in the study, whether they were an MDS Center of Excellence or a high-volume center.

Adverse events

For the most part, therapy-related adverse events were similar across the arms.

Rates of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia and infection and infestations were similar for all 3 cohorts: 89% for azaciditine monotherapy, 91% for the lenalidomide combination, and 91% for the vorinostat combination.

However, the vorinostat arm had more grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal toxicities (14 patients, 15%) compared with the monotherapy arm (4 patients, 4%), P=0.02.

And patients receiving lenalidomide experienced more grade 3 or higher rash (14 patients, 16%) compared with patients receiving monotherapy (3 patients, 3%), P=0.005.

Patients in the combination arms stopped therapy at significantly higher rates than the monotherapy arm. Eight percent of patients receiving monotherapy stopped treatment compared with 20% in the lenalidomide arm and 21% in the vorinostat arm.

Patients in the combination arms also had more dose modifications not specified in the protocol than those in the monotherapy arm. Twenty-four percent receiving azacitidine monotherapy had non-protocol defined dose modifications, compared with 43% in the lenalidomide arm and 42% in the vorinostat arm.

Responses

The ORR for the entire study population was 38%.

Patients in the monotherapy arm had an ORR of 38%, those in the lenalidomide arm, 49%, and those in the vorinostate arm, 27%. Neither arm achieved significance compared with the monotherapy arm.

Patients who were treatment-naïve in the lenalidomide arm had a somewhat improved ORR compared with monotherapy, P=0.08.

The median duration of response for all cohorts was 15 months: 10 months for monotherapy, 14 months for lenalidomide, and 18 months for vorinostat.

Patients who were able to remain on therapy for 6 months or more in the lenalidomide arm achieved a higher ORR of 87% compared with monotherapy (62%, P=0.01). However, there was no difference in response duration with longer therapy.

The median overall survival (OS) was 17 months for all patients, 15 months for patients in the monotherapy group, 19 months for those in the lenalidomide arm, and 17 months for those in the vorinostat group.

CMML patients had similar OS across treatment arms, with the median not yet reached for patients in the monotherapy arm.

Subgroup responses

Patients with CMML in the lenalidomide arm had a significantly higher ORR than CMML patients in the monotherapy arm, 68% and 28%, respectively (P=0.02).

Median duration of response for CMML patients was 19 months, with no differences between the arms.

The investigators observed no differences in ORR for therapy-related MDS, IPSS subgroups, transfusion-dependent patients, or allogeneic transplant rates.

However, they noted ORR was better for patients with chromosome 5 abnormality regardless of treatment arm than for those without the abnormality (odds ratio, 2.17, P=0.008).

One hundred thirteen patients had mutational data available. They had a median number of 2 mutations (range, 0 to 7), with the most common being ASXL1 (n = 31), TET2 (n = 26), SRSF2 (n = 23), TP53 (n = 22), RUNX1 (n = 21), and U2AF1 (n = 19).

Patients with DNMT3A mutation had a significantly higher ORR than for patients without mutations, 67% and 34%, respectively P=0.025).

Patients with BCOR and NRAS mutations had numerically higher, but non-significant, ORR than non-mutated patients. Patients with BCOR mutation had a 57% ORR compared with 34% for non-mutated patients (P=0.23). Patients with NRAS mutation had a 60% ORR compared with 36% for non-mutated patients (P=0.28).

Patients with mutations in TET2 (P = .046) and TP53 (P = .003) had a worse response duration than those without mutations.

Response duration was significantly better with fewer mutations. For 2 or more mutations, the hazard ration was 6.86 versus no mutations (P=0.01).

The investigators believed under-dosing may have compromised response and survival in the combination arms. They suggested that studies focused on the subgroups that seemed to benefit from the combinations should be conducted. ![]()

A 3-arm phase 2 study of azacitidine alone or in combination with lenalidomide or vorinostat in patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) has shown the combination therapies to have similar overall response rates (ORR) to azacitidine monotherapy. Based on these findings, investigators did not choose either combination arm for phase 3 testing of overall survival.

However, patients with CMML treated with the azacitidine-lenalidomide combination had twice the ORR compared with azacitidine monotherapy, they reported.

And patients with certain mutations, such as DNMT3A, BCOR, and NRAS, had higher overall response rates, although only those with the DNMT3A mutation were significant.

Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology on behalf of the North American Intergroup Study SWOG S117.

Doses of azacitidine were the same for monotherapy and combination arms: 75 mg/m2/day intravenously or subcutaneously on days 1 to 7 of a 28-day cycle.

Patients in the lenalidomide arm received 10 mg/day orally of that drug on days 1 to 21, and patients in the vorinostat arm received 300 mg twice daily orally on days 3 to 9.

Patient characteristics

Patients had MDS of IPSS Intermediate-2 or higher or bone marrow blasts 5% or greater. Patients with CMML had fewer than 20% blasts.

The investigators randomized 277 patients to receive either azacitidine alone (n=92), azacitidine plus lenalidomide (n=93), or azacitidine plus vorinostat (n=92).

Patients were a median age of 70 years (range, 28 to 93). Eighty-five patients (31%) were female, 53 (19%) had CMML, and 18 (6%) had treatment-related MDS. More than half the patients were transfusion-dependent at baseline.

Baseline characteristics were similar across the 3 arms. The investigators noted that the baseline characteristics were also similar across the 90 centers participating in the study, whether they were an MDS Center of Excellence or a high-volume center.

Adverse events

For the most part, therapy-related adverse events were similar across the arms.

Rates of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia and infection and infestations were similar for all 3 cohorts: 89% for azaciditine monotherapy, 91% for the lenalidomide combination, and 91% for the vorinostat combination.

However, the vorinostat arm had more grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal toxicities (14 patients, 15%) compared with the monotherapy arm (4 patients, 4%), P=0.02.

And patients receiving lenalidomide experienced more grade 3 or higher rash (14 patients, 16%) compared with patients receiving monotherapy (3 patients, 3%), P=0.005.

Patients in the combination arms stopped therapy at significantly higher rates than the monotherapy arm. Eight percent of patients receiving monotherapy stopped treatment compared with 20% in the lenalidomide arm and 21% in the vorinostat arm.

Patients in the combination arms also had more dose modifications not specified in the protocol than those in the monotherapy arm. Twenty-four percent receiving azacitidine monotherapy had non-protocol defined dose modifications, compared with 43% in the lenalidomide arm and 42% in the vorinostat arm.

Responses

The ORR for the entire study population was 38%.

Patients in the monotherapy arm had an ORR of 38%, those in the lenalidomide arm, 49%, and those in the vorinostate arm, 27%. Neither arm achieved significance compared with the monotherapy arm.