User login

In Vivo Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) imaging received Category I Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January 2016 and can now be submitted to insurance companies with reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy or a global skin pathology service.1 This fairly new technology is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution in vivo cellular images of the skin. It has been shown to be efficacious in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing the number of unnecessary skin biopsies that are performed. In addition to skin cancer diagnosis, RCM imaging also can help guide management of malignant lesions by detecting lateral margins prior to surgery as well as monitoring the lesion over time for treatment efficacy or recurrence. The potential impact of RCM imaging is tremendous, and reimbursement may lead to increased use in clinical practice to the benefit of our patients. Herein, we present a brief review of RCM imaging and reimbursement as well as the benefits and limitations of this new technology for dermatologists.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

In vivo RCM allows us to visualize the epidermis in real time on a cellular level down to the papillary dermis at a high resolution (×30) comparable to histologic examination. With optical sections 3- to 5-µm thick and a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1.0 µm, RCM produces a stack of 500×500-µm2 images up to a depth of approximately 200 µm.2,3 At any chosen depth, these smaller images are stitched together with sophisticated software into a block, or mosaic, increasing the field of view to up to 8×8 mm2. Imaging is performed in en face planes oriented parallel to the skin surface, similar to dermoscopy.

Current CPT Guidelines and Reimbursement

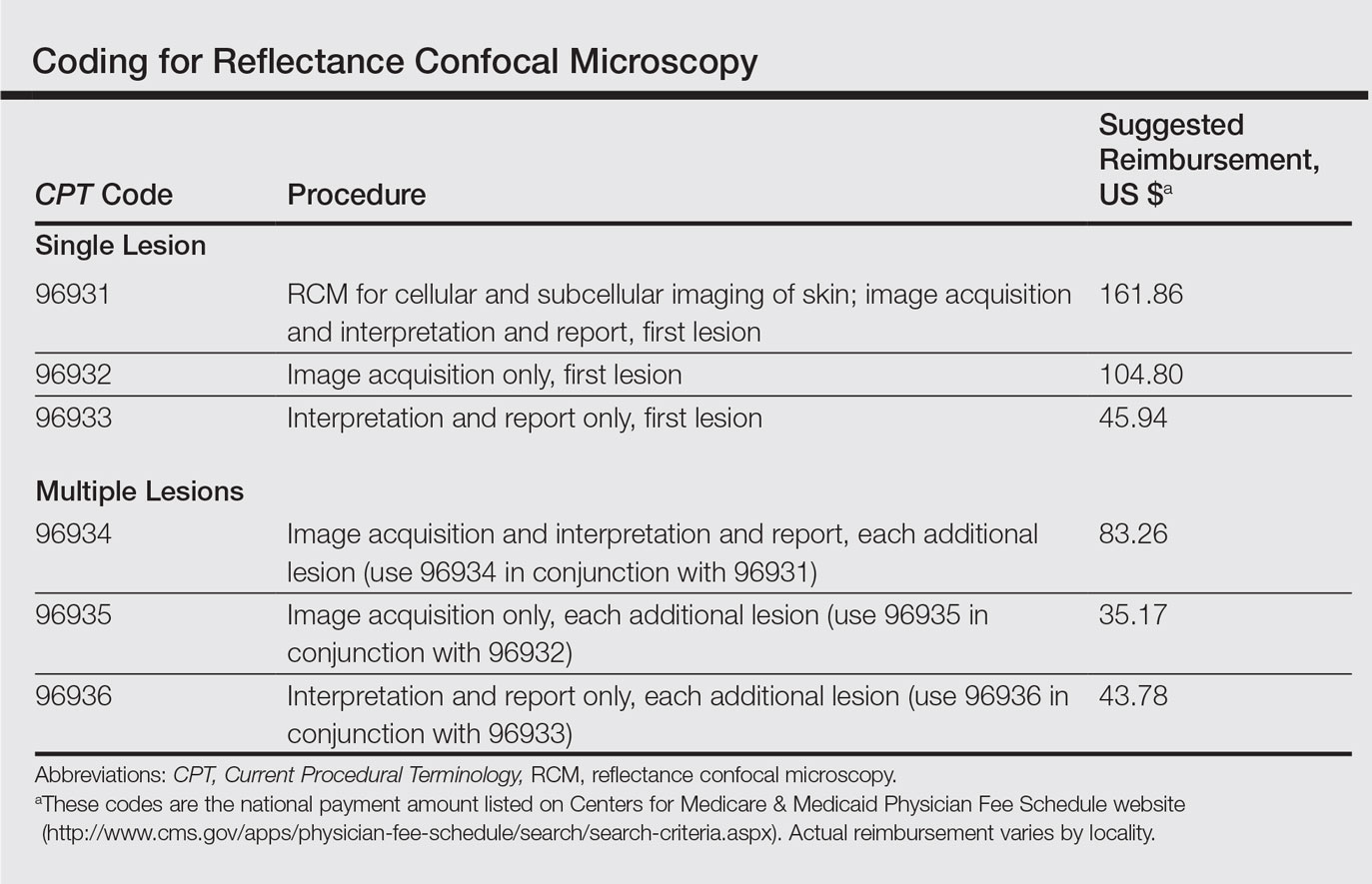

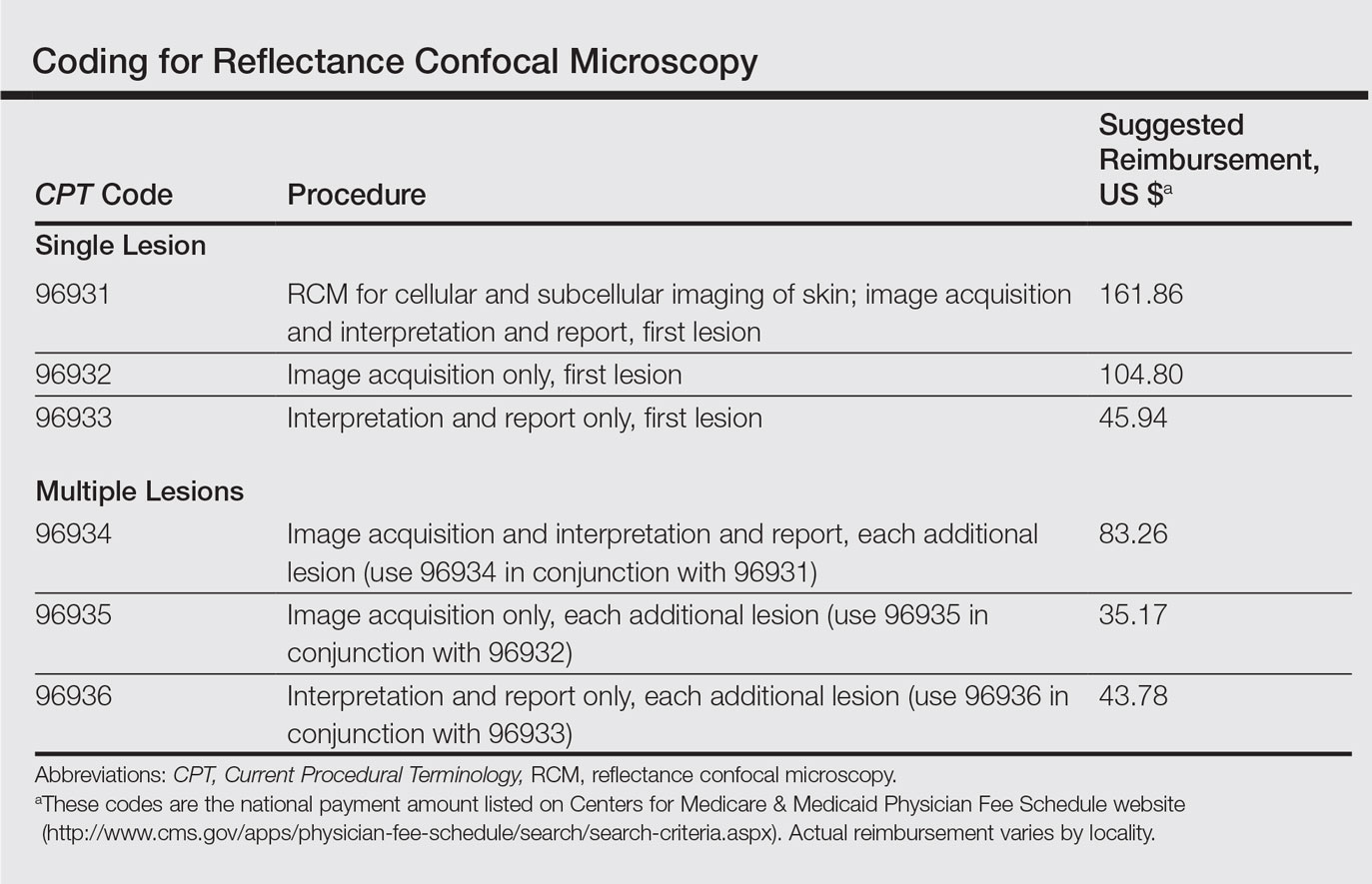

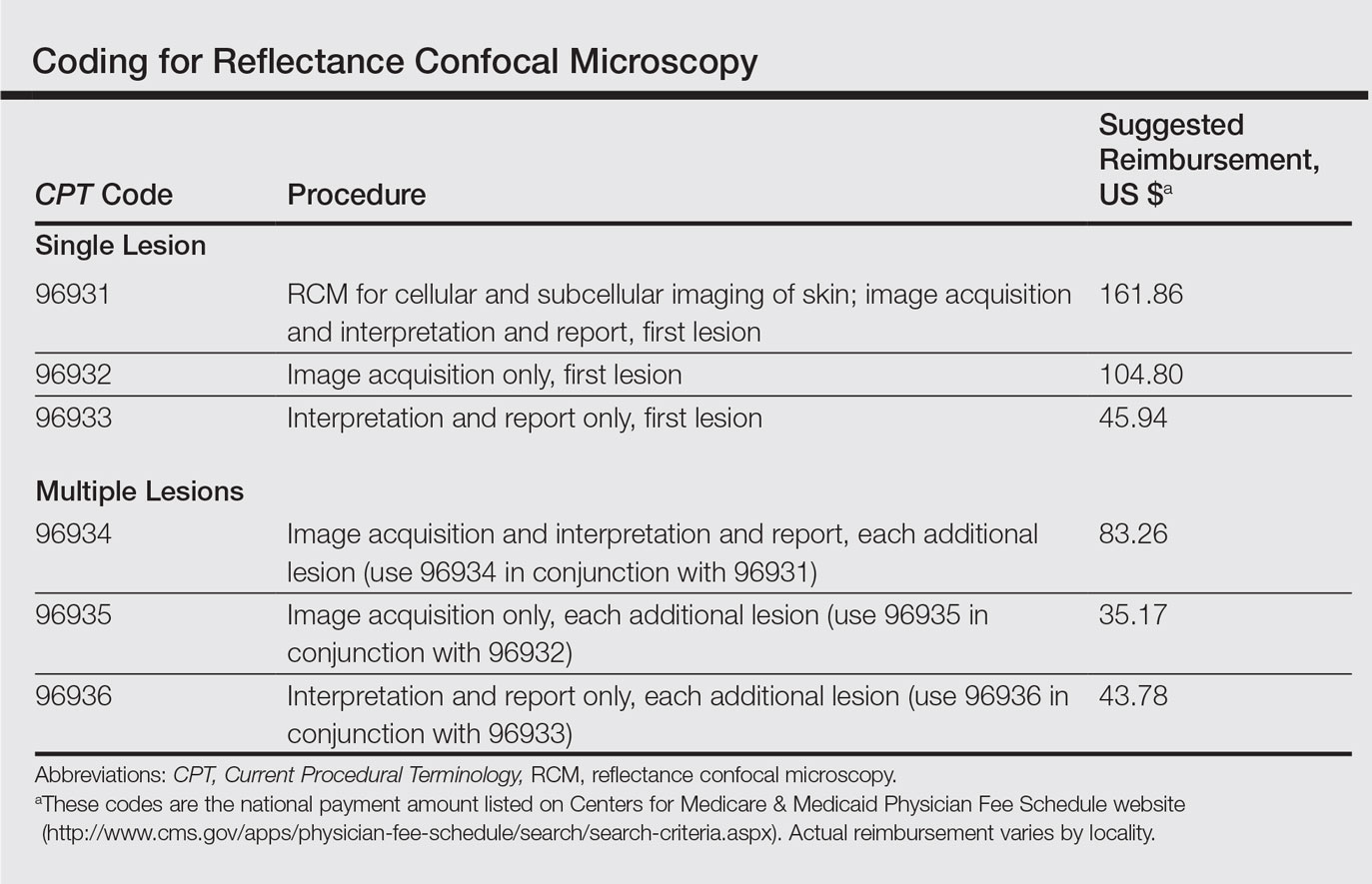

The CPT codes for RCM imaging provide reimbursement on a per-lesion basis and are similar to those used for skin biopsy and pathology (Table).1 Codes 96931 through 96933 are used for imaging of a single lesion on a patient. The first code—96931—is used when image acquisition, interpretation, and report creation are carried out by a single clinician. The next 2 codes are used when one clinician acquires the image—96932—comparable to the technical component of a pathology code, while another reads it and creates the report—96933—similar to a dermatopathologist billing for the professional component of a pathology report. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the next 3 codes—96934, 96935, and 96936—are used in conjunction with the applicable first code for each additional lesion with similar global, technical, and professional components. Because these codes are not in the radiology or pathology sections of CPT, a single code cannot be used with modifier -TC (technical component) and modifier -26, as they are in those sections.

The wide-probe VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D., Inc) currently is the only confocal device that can be reported with a CPT code and routinely reimbursed. The handheld VivaScope 3000 (Caliber I.D., Inc) can only view a small stack and does not have the ability to acquire a full mosaic image; it is not covered by these codes.

Images can be viewed as a stack captured at the same horizontal position but at sequential depths or as a mosaic, which has a larger field of view but is limited to a single plane. To appropriately assess a lesion, clinicians must obtain a mosaic that needs to be assessed at multiple layers for a diagnosis to be made because it is a cross-section view.

Diagnosis

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of RCM imaging in the diagnosis of a wide range of skin diseases, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, infectious diseases, and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as wound healing and skin aging. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging is not limited to the skin; it can be used to evaluate the hair, nails, oral mucosa, and other organs.

According to several studies, RCM imaging notably increases the diagnostic accuracy and detection rate of skin cancers over clinical and dermoscopic examination alone and therefore can act as an aid in differentiating lesions that are benign versus those that are suspicious and should be biopsied.

Reflectance confocal microscopy has been shown to have a mean sensitivity of 94% (range, 92%–96%) and specificity of 83% (range, 81%–84%) for all types of skin cancer when used with dermoscopy.4 In particular, for melanocytic lesions that are ambiguous on dermoscopy, RCM used in addition to dermoscopy increases the mean sensitivity and specificity for melanoma diagnosis to 93% (range, 89%–96%) and 76% (range, 68%–83%), respectively.5 Although these reported sensitivities are comparable to dermoscopy, the specificity is superior, especially for detecting hypomelanotic and amelanotic melanomas, which often lack specific features on dermoscopy.6-8

The combination of RCM with dermoscopy has reduced the number of unnecessary excisions of benign nevi by more than 50% when compared to dermoscopy alone.9 One study showed that the number needed to treat (ie, excise) a melanoma decreased from 14.6 with dermoscopy alone to 6.8 when guided by dermoscopy and RCM imaging.9 In a similar study, the number needed to treat dropped from 19.41 with dermoscopy alone to 6.25 with dermoscopy and RCM.10

These studies were not looking to evaluate RCM as a replacement test but rather as an add-on test to dermoscopy. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging takes longer than dermoscopy for each lesion; therefore, RCM should only be used as an adjunctive tool to dermoscopy and not as an initial screening test. Consequentially, a dermatologist skilled in dermoscopy is essential in deciding which lesions would be appropriate for subsequent RCM imaging.

In Vivo Margin Mapping as an Adjunct to Surgery

Oftentimes, tumor margins are poorly defined and can be difficult to map clinically and dermoscopically. Studies have demonstrated the use of RCM in delineation of surgical margins prior to surgery or excisional biopsies.11,12 Alternatively, when complete removal at biopsy would be impractical (eg, for extremely large lesions or lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face), RCM can be used to pick the best site for an appropriate biopsy, which decreases the chance of sampling error due to skip lesions and increases histologic accuracy.

Nonsurgical Treatment Monitoring

One advantage of RCM over conventional histology is that RCM imaging leaves the tissue intact, allowing dynamic changes to be studied over time, which is useful for monitoring nonmelanoma skin cancers and lentigo maligna being treated with noninvasive therapeutic modalities.13 If not as a definitive treatment, RCM can act as an adjunct for surgery by monitoring reduction in lesion size prior to Mohs micrographic surgery, thereby decreasing the resulting surgical defect.14

Limitations

Imaging Depth

Although RCM is a revolutionary device in the field of dermatology, it has several limitations. With a maximal imaging depth of 350 µm, the imaging resolution decreases substantially with depth, limiting accurate interpretation to 200 µm. Reflectance confocal microscopy can only image the superficial portion of a lesion; therefore, deep tumor margins cannot be assessed. Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic lesions, including lesions on the palms and soles, also are unable to be imaged with RCM. This limitation in depth penetration makes treatment monitoring impossible for invasive lesions that extend into the dermal layer.

Difficult-to-Reach Areas

Another limitation is the difficulty imaging areas such as the ocular canthi, nasal alae, or helices of the ear due to the wide probe size on the VivaScope 1500. The advent of the smaller handheld VivaScope 3000 device allows for improved imaging of concave services and difficult lesions at the risk of less accurate imaging, low field of view, and no reimbursement at present.

False-Positive Results

Although RCM has been shown to be helpful in reducing unnecessary biopsies, there still is the issue of false-positives on imaging. False-positives most commonly occur in nevi with severe atypia or when Langerhans cells are present that cannot always be differentiated from melanocytic cells.3,15,16 One prospective study found 7 false-positive results from 63 sites using RCM for the diagnosis of lentigo malignas.16 False-negatives can occur in the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and scar tissue that can hide cellular morphology or in sampling errors due to skip lesions.3,16

Time Efficiency

The time required for acquisition of RCM mosaics and stacks followed by reading and interpretation can be substantial depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, which is a major limitation for use of RCM in busy dermatology practices; therefore, RCM should be reserved for lesions selected to undergo biopsy that are clinically equivocal for malignancy prior to RCM examination.17 It would not be cost-effective or time effective to evaluate lesions that either clinically or dermoscopically have a high probability of malignancy; however, patients and physicians may opt for increased specificity at the expense of time, particularly when a lesion is located on a cosmetically sensitive area, as patients can avoid initial histologic biopsy and gain the cosmetic benefit of going straight to surgery versus obtaining an initial diagnostic biopsy.

Cost

Lastly, the high cost involved in purchasing an RCM device and the training involved to use and interpret RCM images currently limits RCM to large academic centers. Reimbursement may make more widespread use feasible. In any event, RCM imaging should be part of the curriculum for both dermatology and pathology trainees.

Future Directions

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging modality that allows for real-time evaluation of the skin. Used in conjunction with dermoscopy, RCM can substantially improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies. Now that RCM has finally gained foundational CPT codes and insurance reimbursement, there may be a growing demand for clinicians to incorporate this technology into their clinical practice.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Que SK, Fraga-Braghiroli N, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Through the looking glass: basics and principles of reflectance confocal microscopy [published online June 4, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:276-284.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside [published online October 27, 2016]. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Xiong YD, Ma S, Li X, et al. A meta-analysis of reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1295-1302.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:923-929.

- Losi A, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, et al. Hyporeflective pagetoid cells: a new clue for amelanotic melanoma diagnosis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:48-54.

- Guitera P, Menzies SQ, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy are complementary techniques for the diagnosis of difficult amelanotic and light-coloured skin lesions [published online October 12, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1311-1319.

- Pellacani G, Pepe P, Casari A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1044-1051.

- Pellacani G, Witkowski A, Cesinaro AM, et al. Cost-benefit of reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnostic performance of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:413-419.

- Champin J, Perrot JL, Cinotti E, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to optimize the spaghetti technique for defining surgical margins of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:247-256.

- Hibler BP, Cordova M, Wong RJ, et al. Intraoperative real-time reflectance confocal microscopy for guiding surgical margins of lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:980-983.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:202a10.

- Torres A, Niemeyer A, Berkes B, et al. 5% imiquimod cream and reflectance-mode confocal microscopy as adjunct modalities to Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12, pt 1):1462-1469.

- Hashemi P, Pulitzer MP, Scope A, et al. Langerhans cells and melanocytes share similar morphologic features under in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: a challenge for melanoma diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:452-462.

- Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1114-1120.

- Borsari S, Pampena R, Lallas A, et al. Clinical indications for use of reflectance confocal microscopy for skin cancer diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1093-1098.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) imaging received Category I Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January 2016 and can now be submitted to insurance companies with reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy or a global skin pathology service.1 This fairly new technology is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution in vivo cellular images of the skin. It has been shown to be efficacious in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing the number of unnecessary skin biopsies that are performed. In addition to skin cancer diagnosis, RCM imaging also can help guide management of malignant lesions by detecting lateral margins prior to surgery as well as monitoring the lesion over time for treatment efficacy or recurrence. The potential impact of RCM imaging is tremendous, and reimbursement may lead to increased use in clinical practice to the benefit of our patients. Herein, we present a brief review of RCM imaging and reimbursement as well as the benefits and limitations of this new technology for dermatologists.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

In vivo RCM allows us to visualize the epidermis in real time on a cellular level down to the papillary dermis at a high resolution (×30) comparable to histologic examination. With optical sections 3- to 5-µm thick and a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1.0 µm, RCM produces a stack of 500×500-µm2 images up to a depth of approximately 200 µm.2,3 At any chosen depth, these smaller images are stitched together with sophisticated software into a block, or mosaic, increasing the field of view to up to 8×8 mm2. Imaging is performed in en face planes oriented parallel to the skin surface, similar to dermoscopy.

Current CPT Guidelines and Reimbursement

The CPT codes for RCM imaging provide reimbursement on a per-lesion basis and are similar to those used for skin biopsy and pathology (Table).1 Codes 96931 through 96933 are used for imaging of a single lesion on a patient. The first code—96931—is used when image acquisition, interpretation, and report creation are carried out by a single clinician. The next 2 codes are used when one clinician acquires the image—96932—comparable to the technical component of a pathology code, while another reads it and creates the report—96933—similar to a dermatopathologist billing for the professional component of a pathology report. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the next 3 codes—96934, 96935, and 96936—are used in conjunction with the applicable first code for each additional lesion with similar global, technical, and professional components. Because these codes are not in the radiology or pathology sections of CPT, a single code cannot be used with modifier -TC (technical component) and modifier -26, as they are in those sections.

The wide-probe VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D., Inc) currently is the only confocal device that can be reported with a CPT code and routinely reimbursed. The handheld VivaScope 3000 (Caliber I.D., Inc) can only view a small stack and does not have the ability to acquire a full mosaic image; it is not covered by these codes.

Images can be viewed as a stack captured at the same horizontal position but at sequential depths or as a mosaic, which has a larger field of view but is limited to a single plane. To appropriately assess a lesion, clinicians must obtain a mosaic that needs to be assessed at multiple layers for a diagnosis to be made because it is a cross-section view.

Diagnosis

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of RCM imaging in the diagnosis of a wide range of skin diseases, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, infectious diseases, and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as wound healing and skin aging. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging is not limited to the skin; it can be used to evaluate the hair, nails, oral mucosa, and other organs.

According to several studies, RCM imaging notably increases the diagnostic accuracy and detection rate of skin cancers over clinical and dermoscopic examination alone and therefore can act as an aid in differentiating lesions that are benign versus those that are suspicious and should be biopsied.

Reflectance confocal microscopy has been shown to have a mean sensitivity of 94% (range, 92%–96%) and specificity of 83% (range, 81%–84%) for all types of skin cancer when used with dermoscopy.4 In particular, for melanocytic lesions that are ambiguous on dermoscopy, RCM used in addition to dermoscopy increases the mean sensitivity and specificity for melanoma diagnosis to 93% (range, 89%–96%) and 76% (range, 68%–83%), respectively.5 Although these reported sensitivities are comparable to dermoscopy, the specificity is superior, especially for detecting hypomelanotic and amelanotic melanomas, which often lack specific features on dermoscopy.6-8

The combination of RCM with dermoscopy has reduced the number of unnecessary excisions of benign nevi by more than 50% when compared to dermoscopy alone.9 One study showed that the number needed to treat (ie, excise) a melanoma decreased from 14.6 with dermoscopy alone to 6.8 when guided by dermoscopy and RCM imaging.9 In a similar study, the number needed to treat dropped from 19.41 with dermoscopy alone to 6.25 with dermoscopy and RCM.10

These studies were not looking to evaluate RCM as a replacement test but rather as an add-on test to dermoscopy. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging takes longer than dermoscopy for each lesion; therefore, RCM should only be used as an adjunctive tool to dermoscopy and not as an initial screening test. Consequentially, a dermatologist skilled in dermoscopy is essential in deciding which lesions would be appropriate for subsequent RCM imaging.

In Vivo Margin Mapping as an Adjunct to Surgery

Oftentimes, tumor margins are poorly defined and can be difficult to map clinically and dermoscopically. Studies have demonstrated the use of RCM in delineation of surgical margins prior to surgery or excisional biopsies.11,12 Alternatively, when complete removal at biopsy would be impractical (eg, for extremely large lesions or lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face), RCM can be used to pick the best site for an appropriate biopsy, which decreases the chance of sampling error due to skip lesions and increases histologic accuracy.

Nonsurgical Treatment Monitoring

One advantage of RCM over conventional histology is that RCM imaging leaves the tissue intact, allowing dynamic changes to be studied over time, which is useful for monitoring nonmelanoma skin cancers and lentigo maligna being treated with noninvasive therapeutic modalities.13 If not as a definitive treatment, RCM can act as an adjunct for surgery by monitoring reduction in lesion size prior to Mohs micrographic surgery, thereby decreasing the resulting surgical defect.14

Limitations

Imaging Depth

Although RCM is a revolutionary device in the field of dermatology, it has several limitations. With a maximal imaging depth of 350 µm, the imaging resolution decreases substantially with depth, limiting accurate interpretation to 200 µm. Reflectance confocal microscopy can only image the superficial portion of a lesion; therefore, deep tumor margins cannot be assessed. Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic lesions, including lesions on the palms and soles, also are unable to be imaged with RCM. This limitation in depth penetration makes treatment monitoring impossible for invasive lesions that extend into the dermal layer.

Difficult-to-Reach Areas

Another limitation is the difficulty imaging areas such as the ocular canthi, nasal alae, or helices of the ear due to the wide probe size on the VivaScope 1500. The advent of the smaller handheld VivaScope 3000 device allows for improved imaging of concave services and difficult lesions at the risk of less accurate imaging, low field of view, and no reimbursement at present.

False-Positive Results

Although RCM has been shown to be helpful in reducing unnecessary biopsies, there still is the issue of false-positives on imaging. False-positives most commonly occur in nevi with severe atypia or when Langerhans cells are present that cannot always be differentiated from melanocytic cells.3,15,16 One prospective study found 7 false-positive results from 63 sites using RCM for the diagnosis of lentigo malignas.16 False-negatives can occur in the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and scar tissue that can hide cellular morphology or in sampling errors due to skip lesions.3,16

Time Efficiency

The time required for acquisition of RCM mosaics and stacks followed by reading and interpretation can be substantial depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, which is a major limitation for use of RCM in busy dermatology practices; therefore, RCM should be reserved for lesions selected to undergo biopsy that are clinically equivocal for malignancy prior to RCM examination.17 It would not be cost-effective or time effective to evaluate lesions that either clinically or dermoscopically have a high probability of malignancy; however, patients and physicians may opt for increased specificity at the expense of time, particularly when a lesion is located on a cosmetically sensitive area, as patients can avoid initial histologic biopsy and gain the cosmetic benefit of going straight to surgery versus obtaining an initial diagnostic biopsy.

Cost

Lastly, the high cost involved in purchasing an RCM device and the training involved to use and interpret RCM images currently limits RCM to large academic centers. Reimbursement may make more widespread use feasible. In any event, RCM imaging should be part of the curriculum for both dermatology and pathology trainees.

Future Directions

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging modality that allows for real-time evaluation of the skin. Used in conjunction with dermoscopy, RCM can substantially improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies. Now that RCM has finally gained foundational CPT codes and insurance reimbursement, there may be a growing demand for clinicians to incorporate this technology into their clinical practice.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) imaging received Category I Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January 2016 and can now be submitted to insurance companies with reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy or a global skin pathology service.1 This fairly new technology is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution in vivo cellular images of the skin. It has been shown to be efficacious in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing the number of unnecessary skin biopsies that are performed. In addition to skin cancer diagnosis, RCM imaging also can help guide management of malignant lesions by detecting lateral margins prior to surgery as well as monitoring the lesion over time for treatment efficacy or recurrence. The potential impact of RCM imaging is tremendous, and reimbursement may lead to increased use in clinical practice to the benefit of our patients. Herein, we present a brief review of RCM imaging and reimbursement as well as the benefits and limitations of this new technology for dermatologists.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

In vivo RCM allows us to visualize the epidermis in real time on a cellular level down to the papillary dermis at a high resolution (×30) comparable to histologic examination. With optical sections 3- to 5-µm thick and a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1.0 µm, RCM produces a stack of 500×500-µm2 images up to a depth of approximately 200 µm.2,3 At any chosen depth, these smaller images are stitched together with sophisticated software into a block, or mosaic, increasing the field of view to up to 8×8 mm2. Imaging is performed in en face planes oriented parallel to the skin surface, similar to dermoscopy.

Current CPT Guidelines and Reimbursement

The CPT codes for RCM imaging provide reimbursement on a per-lesion basis and are similar to those used for skin biopsy and pathology (Table).1 Codes 96931 through 96933 are used for imaging of a single lesion on a patient. The first code—96931—is used when image acquisition, interpretation, and report creation are carried out by a single clinician. The next 2 codes are used when one clinician acquires the image—96932—comparable to the technical component of a pathology code, while another reads it and creates the report—96933—similar to a dermatopathologist billing for the professional component of a pathology report. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the next 3 codes—96934, 96935, and 96936—are used in conjunction with the applicable first code for each additional lesion with similar global, technical, and professional components. Because these codes are not in the radiology or pathology sections of CPT, a single code cannot be used with modifier -TC (technical component) and modifier -26, as they are in those sections.

The wide-probe VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D., Inc) currently is the only confocal device that can be reported with a CPT code and routinely reimbursed. The handheld VivaScope 3000 (Caliber I.D., Inc) can only view a small stack and does not have the ability to acquire a full mosaic image; it is not covered by these codes.

Images can be viewed as a stack captured at the same horizontal position but at sequential depths or as a mosaic, which has a larger field of view but is limited to a single plane. To appropriately assess a lesion, clinicians must obtain a mosaic that needs to be assessed at multiple layers for a diagnosis to be made because it is a cross-section view.

Diagnosis

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of RCM imaging in the diagnosis of a wide range of skin diseases, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, infectious diseases, and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as wound healing and skin aging. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging is not limited to the skin; it can be used to evaluate the hair, nails, oral mucosa, and other organs.

According to several studies, RCM imaging notably increases the diagnostic accuracy and detection rate of skin cancers over clinical and dermoscopic examination alone and therefore can act as an aid in differentiating lesions that are benign versus those that are suspicious and should be biopsied.

Reflectance confocal microscopy has been shown to have a mean sensitivity of 94% (range, 92%–96%) and specificity of 83% (range, 81%–84%) for all types of skin cancer when used with dermoscopy.4 In particular, for melanocytic lesions that are ambiguous on dermoscopy, RCM used in addition to dermoscopy increases the mean sensitivity and specificity for melanoma diagnosis to 93% (range, 89%–96%) and 76% (range, 68%–83%), respectively.5 Although these reported sensitivities are comparable to dermoscopy, the specificity is superior, especially for detecting hypomelanotic and amelanotic melanomas, which often lack specific features on dermoscopy.6-8

The combination of RCM with dermoscopy has reduced the number of unnecessary excisions of benign nevi by more than 50% when compared to dermoscopy alone.9 One study showed that the number needed to treat (ie, excise) a melanoma decreased from 14.6 with dermoscopy alone to 6.8 when guided by dermoscopy and RCM imaging.9 In a similar study, the number needed to treat dropped from 19.41 with dermoscopy alone to 6.25 with dermoscopy and RCM.10

These studies were not looking to evaluate RCM as a replacement test but rather as an add-on test to dermoscopy. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging takes longer than dermoscopy for each lesion; therefore, RCM should only be used as an adjunctive tool to dermoscopy and not as an initial screening test. Consequentially, a dermatologist skilled in dermoscopy is essential in deciding which lesions would be appropriate for subsequent RCM imaging.

In Vivo Margin Mapping as an Adjunct to Surgery

Oftentimes, tumor margins are poorly defined and can be difficult to map clinically and dermoscopically. Studies have demonstrated the use of RCM in delineation of surgical margins prior to surgery or excisional biopsies.11,12 Alternatively, when complete removal at biopsy would be impractical (eg, for extremely large lesions or lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face), RCM can be used to pick the best site for an appropriate biopsy, which decreases the chance of sampling error due to skip lesions and increases histologic accuracy.

Nonsurgical Treatment Monitoring

One advantage of RCM over conventional histology is that RCM imaging leaves the tissue intact, allowing dynamic changes to be studied over time, which is useful for monitoring nonmelanoma skin cancers and lentigo maligna being treated with noninvasive therapeutic modalities.13 If not as a definitive treatment, RCM can act as an adjunct for surgery by monitoring reduction in lesion size prior to Mohs micrographic surgery, thereby decreasing the resulting surgical defect.14

Limitations

Imaging Depth

Although RCM is a revolutionary device in the field of dermatology, it has several limitations. With a maximal imaging depth of 350 µm, the imaging resolution decreases substantially with depth, limiting accurate interpretation to 200 µm. Reflectance confocal microscopy can only image the superficial portion of a lesion; therefore, deep tumor margins cannot be assessed. Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic lesions, including lesions on the palms and soles, also are unable to be imaged with RCM. This limitation in depth penetration makes treatment monitoring impossible for invasive lesions that extend into the dermal layer.

Difficult-to-Reach Areas

Another limitation is the difficulty imaging areas such as the ocular canthi, nasal alae, or helices of the ear due to the wide probe size on the VivaScope 1500. The advent of the smaller handheld VivaScope 3000 device allows for improved imaging of concave services and difficult lesions at the risk of less accurate imaging, low field of view, and no reimbursement at present.

False-Positive Results

Although RCM has been shown to be helpful in reducing unnecessary biopsies, there still is the issue of false-positives on imaging. False-positives most commonly occur in nevi with severe atypia or when Langerhans cells are present that cannot always be differentiated from melanocytic cells.3,15,16 One prospective study found 7 false-positive results from 63 sites using RCM for the diagnosis of lentigo malignas.16 False-negatives can occur in the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and scar tissue that can hide cellular morphology or in sampling errors due to skip lesions.3,16

Time Efficiency

The time required for acquisition of RCM mosaics and stacks followed by reading and interpretation can be substantial depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, which is a major limitation for use of RCM in busy dermatology practices; therefore, RCM should be reserved for lesions selected to undergo biopsy that are clinically equivocal for malignancy prior to RCM examination.17 It would not be cost-effective or time effective to evaluate lesions that either clinically or dermoscopically have a high probability of malignancy; however, patients and physicians may opt for increased specificity at the expense of time, particularly when a lesion is located on a cosmetically sensitive area, as patients can avoid initial histologic biopsy and gain the cosmetic benefit of going straight to surgery versus obtaining an initial diagnostic biopsy.

Cost

Lastly, the high cost involved in purchasing an RCM device and the training involved to use and interpret RCM images currently limits RCM to large academic centers. Reimbursement may make more widespread use feasible. In any event, RCM imaging should be part of the curriculum for both dermatology and pathology trainees.

Future Directions

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging modality that allows for real-time evaluation of the skin. Used in conjunction with dermoscopy, RCM can substantially improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies. Now that RCM has finally gained foundational CPT codes and insurance reimbursement, there may be a growing demand for clinicians to incorporate this technology into their clinical practice.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Que SK, Fraga-Braghiroli N, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Through the looking glass: basics and principles of reflectance confocal microscopy [published online June 4, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:276-284.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside [published online October 27, 2016]. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Xiong YD, Ma S, Li X, et al. A meta-analysis of reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1295-1302.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:923-929.

- Losi A, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, et al. Hyporeflective pagetoid cells: a new clue for amelanotic melanoma diagnosis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:48-54.

- Guitera P, Menzies SQ, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy are complementary techniques for the diagnosis of difficult amelanotic and light-coloured skin lesions [published online October 12, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1311-1319.

- Pellacani G, Pepe P, Casari A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1044-1051.

- Pellacani G, Witkowski A, Cesinaro AM, et al. Cost-benefit of reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnostic performance of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:413-419.

- Champin J, Perrot JL, Cinotti E, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to optimize the spaghetti technique for defining surgical margins of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:247-256.

- Hibler BP, Cordova M, Wong RJ, et al. Intraoperative real-time reflectance confocal microscopy for guiding surgical margins of lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:980-983.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:202a10.

- Torres A, Niemeyer A, Berkes B, et al. 5% imiquimod cream and reflectance-mode confocal microscopy as adjunct modalities to Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12, pt 1):1462-1469.

- Hashemi P, Pulitzer MP, Scope A, et al. Langerhans cells and melanocytes share similar morphologic features under in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: a challenge for melanoma diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:452-462.

- Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1114-1120.

- Borsari S, Pampena R, Lallas A, et al. Clinical indications for use of reflectance confocal microscopy for skin cancer diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1093-1098.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Que SK, Fraga-Braghiroli N, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Through the looking glass: basics and principles of reflectance confocal microscopy [published online June 4, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:276-284.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside [published online October 27, 2016]. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Xiong YD, Ma S, Li X, et al. A meta-analysis of reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1295-1302.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:923-929.

- Losi A, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, et al. Hyporeflective pagetoid cells: a new clue for amelanotic melanoma diagnosis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:48-54.

- Guitera P, Menzies SQ, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy are complementary techniques for the diagnosis of difficult amelanotic and light-coloured skin lesions [published online October 12, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1311-1319.

- Pellacani G, Pepe P, Casari A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1044-1051.

- Pellacani G, Witkowski A, Cesinaro AM, et al. Cost-benefit of reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnostic performance of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:413-419.

- Champin J, Perrot JL, Cinotti E, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to optimize the spaghetti technique for defining surgical margins of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:247-256.

- Hibler BP, Cordova M, Wong RJ, et al. Intraoperative real-time reflectance confocal microscopy for guiding surgical margins of lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:980-983.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:202a10.

- Torres A, Niemeyer A, Berkes B, et al. 5% imiquimod cream and reflectance-mode confocal microscopy as adjunct modalities to Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12, pt 1):1462-1469.

- Hashemi P, Pulitzer MP, Scope A, et al. Langerhans cells and melanocytes share similar morphologic features under in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: a challenge for melanoma diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:452-462.

- Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1114-1120.

- Borsari S, Pampena R, Lallas A, et al. Clinical indications for use of reflectance confocal microscopy for skin cancer diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1093-1098.

Practice Points

- Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) recently received Category I Current Procedural Terminology codes for reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy.

- When used in combination with dermoscopy, RCM has been shown to increase diagnostic accuracy of skin cancer.

- Reflectance confocal microscopy also is useful in surgical treatment planning and monitoring nonsurgical treatments over time.

- Limitations of RCM imaging include low imaging depth, difficulty in imaging certain areas of the skin, learning curve for interpreting these images, and the cost of equipment.

Mitigating Burnout - Part 3

It is easy to look at the changes required to mitigate burnout and improve compassionate care and see the burden being placed mainly on the physician. Many of the proposed modifications seem to require the one commodity surgeons lack most, time. Any widespread effort to mitigate the burnout crisis must involve decreasing the barriers to patient care and reducing the physicians’ time constraints.

This may seem daunting, but broad changes in our healthcare system have been implemented in the name of quality, reducing errors, and alleviating trainee fatigue. Burnout can be a similar force for change. Much like the resident’s 80-hour workweek, however, in what manner this change is applied will be the ultimate determinant of the movement’s success.

This series of articles dealt with the adverse consequences of surgeon burnout on both clinicians and their patients, and then presented a conceptual framework to promote workforce well-being. Strategies that the SVS might adopt have been suggested. The central proposal is that helping physicians to deliver compassionate, collaborative care will not only mitigate burnout but also will enhance provider engagement, patient experience, and clinical outcomes, as well as improve the quality and safety of healthcare delivery. It seems reasonable to question if such broad strategic proposals are scalable to individual clinical settings.

The characteristics of compassionate care have been well described by patients, and, not surprisingly, only 53% reported that their last encounter with the health care system was compassionate. In 2014, a multidisciplinary consortium published recommendations for advancing compassionate person- and family-centered care. They detailed the attributes, values, and behaviors of such care, including focusing one’s attention, recognizing nonverbal clues, active listening, demonstrating nonjudgmental interest in the whole person, understanding the context of a person’s disease, and asking about the patient’s chief concerns in addition to their chief complaints. Most significantly, the authors outlined how these attributes could be integrated into existing competency documents such as those provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Entrustable Professional Activities, or the milestones programs of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).

It is but a small step to enhance current criteria for certification, clinical appointment, and privileging by including these professional attributes. Bear in mind that these skills are teachable and easily incorporated into health professional education and clinical care. As for metrics, the Schwartz Compassionate Care Scale is a validated patient-rated questionnaire that reliably measures physicians’ compassion and overall patient satisfaction and is available in the public domain. It also provides a metric that is important to clinicians and, when placed on the hospital dashboard, highlights that compassion is an organizational priority. Such priorities become the fabric of the workforce when organizational leadership installs programs such as values-based recruitment, retention, and promotion as Vivian Lee describes at the University of Utah Health System. Mitigating burnout requires changing the culture in which clinicians work and with whom they work.

Vascular surgeons and their professional surgical societies have a leadership opportunity to design high performing teams. Most patient care models have been structured around traditional medical and surgical departments. This paradigm overlooks the fact that patients do not “get sick” within traditional teaching disciplines but do so across varied medical and surgical specialties. Changes in organizational hierarchy are needed so that team-based care is supported. In addition to physician and nurse clinicians, the new teams would do well to expand to all “caregivers,” i.e. everyone who touches the patient (technologists, interpreters, pharmacists, transport workers, support staff, and administrators).

On the front line

On April 15, 2013, at 2:49 pm, two homemade bombs detonated near the finish line of the Boston Marathon killing three people at the scene and injuring 264 others; the most severe sustaining mutilating lower extremity injuries. Much has been written about the preparedness, the emergency response, and the fact that all those who made it to the hospital survived. Jeffrey Kalish, MD, a vascular surgeon at Boston Medical Center and SVS member, was on the front line that day. We asked him to share his personal experience of caring for the victims through the lens of compassionate collaborative care.

“It has been over four years since I went from being a spectator near the Boston Marathon finish line to rushing directly to the operating rooms at Boston Medical Center to help our teams perform lifesaving procedures on critically ill patients, including amputations and complex vascular repairs. While I have learned a tremendous amount since that experience with regard to limb salvage and amputation, reconstructive techniques, and prosthetics, I will focus here on the care the patients and their families received, the lessons our hospital learned from the weeks and months that followed, and how we modeled this care going forward for all amputation patients at Boston Medical Center.

"Based on lessons from the Boston Marathon bombings, I aligned a multidisciplinary team of health care providers in order to formalize and standardize best practices to benefit our amputation patients. STRONG (Surgery To Rehab Ongoing Needs Group) continues to strive toward the ultimate goal of improving and coordinating care for amputation patients and their families as they transition from the hospital setting to rehabilitation. Some of our guiding principles, along with their positive impacts on patient care and physician well-being, are highlighted below:

1. Sustaining hope with a new mindset: Although surgeons have historically considered amputation as a treatment failure, a more appropriate mindset is that amputation can often be a reconstructive procedure in the surgical armamentarium designed to restore a patient back to full function.

2. Seeing the patient in context: Shared decision making can occur more readily once a surgeon and the care team seek to understand the whole person and their family, including what that person does for work and leisure.

3. Communication with colleagues, patients, and families: Patient and family fear and confusion can often be reduced after establishment of a multi-disciplinary team with daily care coordination and consistent messaging. Breaking down traditional hospital silos to allow for improved coordination of care benefits both the patients and the practitioners.

4. Managing emotional and physical suffering: Introducing social workers, mental health professionals, or pastoral care advocates into the care team as soon as a patient is ready can help manage the emotional and psychosocial needs of patients and their families.

5. Sustaining long term surgeon/patient relationships: As clinicians, we can feel rewarded after restoring functional performance in our patients and by meeting the needs of our patients and families. This can occur both in the short-term during the acute hospital stay and in the long-term as we follow our patients’ progress towards achievement of their ultimate goals.

6. Attend to one’s own well-being and foster resilience. There will never be a substitute in our profession for the human connection between our patients and ourselves as their caregivers, and this connection should be one of the most treasured aspects of our work life. We should seek daily reminders of these positive interactions to nurture our ability to cope with a grueling and challenging field, where the outcomes are not always as ideal as we hope.

For me, STRONG is now a consistent and powerful reminder of why I originally became a doctor in the first place, and I strive to propagate this model of compassionate care to benefit future patients as we move forward together.”

We are at an inflexion point in health care. No amount of individual resilience can withstand a toxic or nonsupportive environment. It is unreasonable to think that simply by taking better care of ourselves we are going to resolve the issue of burnout. We need to rethink our current systems of care and focus our energy on developing those that support our ability to deliver the kind of care we know our patients need and deserve. We have an opportunity to alleviate the suffering many providers are experiencing as they strive to heal their patients. We have an opportunity to improve both physician and patient engagement, develop care delivery systems we know our patients deserve, and restore the deep sense of satisfaction that comes from practicing medicine and surgery. There is abundant expertise within our professional medical and surgical societies. The SVS has the courage and the duty to lead.

Drs. Colman, Kalish, and Sheahan extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, M.D., Scholar in Residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston, Mass., and Clinical Professor of Orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Bibliography

1. Acad Med (2016) 91:338-344

2. Health Aff (2011) 30:1772-1778

3. Patient Educ Couns (2015) 98:1005-10

4. Acad Med (2016) 91:310-316

5. http://www.theschwartzcenter.org/media/Triple-C-Conference-Framework-Tables_FINAL.pdf

6. http://www.theschwartzcenter.org/media/Triple-C-Conference-Recommendations-Report_FINAL1.pdf

7. JAMA (2017) 317: 901-2

8. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2017) 475:1309-14.

It is easy to look at the changes required to mitigate burnout and improve compassionate care and see the burden being placed mainly on the physician. Many of the proposed modifications seem to require the one commodity surgeons lack most, time. Any widespread effort to mitigate the burnout crisis must involve decreasing the barriers to patient care and reducing the physicians’ time constraints.

This may seem daunting, but broad changes in our healthcare system have been implemented in the name of quality, reducing errors, and alleviating trainee fatigue. Burnout can be a similar force for change. Much like the resident’s 80-hour workweek, however, in what manner this change is applied will be the ultimate determinant of the movement’s success.

This series of articles dealt with the adverse consequences of surgeon burnout on both clinicians and their patients, and then presented a conceptual framework to promote workforce well-being. Strategies that the SVS might adopt have been suggested. The central proposal is that helping physicians to deliver compassionate, collaborative care will not only mitigate burnout but also will enhance provider engagement, patient experience, and clinical outcomes, as well as improve the quality and safety of healthcare delivery. It seems reasonable to question if such broad strategic proposals are scalable to individual clinical settings.

The characteristics of compassionate care have been well described by patients, and, not surprisingly, only 53% reported that their last encounter with the health care system was compassionate. In 2014, a multidisciplinary consortium published recommendations for advancing compassionate person- and family-centered care. They detailed the attributes, values, and behaviors of such care, including focusing one’s attention, recognizing nonverbal clues, active listening, demonstrating nonjudgmental interest in the whole person, understanding the context of a person’s disease, and asking about the patient’s chief concerns in addition to their chief complaints. Most significantly, the authors outlined how these attributes could be integrated into existing competency documents such as those provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Entrustable Professional Activities, or the milestones programs of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).

It is but a small step to enhance current criteria for certification, clinical appointment, and privileging by including these professional attributes. Bear in mind that these skills are teachable and easily incorporated into health professional education and clinical care. As for metrics, the Schwartz Compassionate Care Scale is a validated patient-rated questionnaire that reliably measures physicians’ compassion and overall patient satisfaction and is available in the public domain. It also provides a metric that is important to clinicians and, when placed on the hospital dashboard, highlights that compassion is an organizational priority. Such priorities become the fabric of the workforce when organizational leadership installs programs such as values-based recruitment, retention, and promotion as Vivian Lee describes at the University of Utah Health System. Mitigating burnout requires changing the culture in which clinicians work and with whom they work.

Vascular surgeons and their professional surgical societies have a leadership opportunity to design high performing teams. Most patient care models have been structured around traditional medical and surgical departments. This paradigm overlooks the fact that patients do not “get sick” within traditional teaching disciplines but do so across varied medical and surgical specialties. Changes in organizational hierarchy are needed so that team-based care is supported. In addition to physician and nurse clinicians, the new teams would do well to expand to all “caregivers,” i.e. everyone who touches the patient (technologists, interpreters, pharmacists, transport workers, support staff, and administrators).

On the front line

On April 15, 2013, at 2:49 pm, two homemade bombs detonated near the finish line of the Boston Marathon killing three people at the scene and injuring 264 others; the most severe sustaining mutilating lower extremity injuries. Much has been written about the preparedness, the emergency response, and the fact that all those who made it to the hospital survived. Jeffrey Kalish, MD, a vascular surgeon at Boston Medical Center and SVS member, was on the front line that day. We asked him to share his personal experience of caring for the victims through the lens of compassionate collaborative care.

“It has been over four years since I went from being a spectator near the Boston Marathon finish line to rushing directly to the operating rooms at Boston Medical Center to help our teams perform lifesaving procedures on critically ill patients, including amputations and complex vascular repairs. While I have learned a tremendous amount since that experience with regard to limb salvage and amputation, reconstructive techniques, and prosthetics, I will focus here on the care the patients and their families received, the lessons our hospital learned from the weeks and months that followed, and how we modeled this care going forward for all amputation patients at Boston Medical Center.

"Based on lessons from the Boston Marathon bombings, I aligned a multidisciplinary team of health care providers in order to formalize and standardize best practices to benefit our amputation patients. STRONG (Surgery To Rehab Ongoing Needs Group) continues to strive toward the ultimate goal of improving and coordinating care for amputation patients and their families as they transition from the hospital setting to rehabilitation. Some of our guiding principles, along with their positive impacts on patient care and physician well-being, are highlighted below:

1. Sustaining hope with a new mindset: Although surgeons have historically considered amputation as a treatment failure, a more appropriate mindset is that amputation can often be a reconstructive procedure in the surgical armamentarium designed to restore a patient back to full function.

2. Seeing the patient in context: Shared decision making can occur more readily once a surgeon and the care team seek to understand the whole person and their family, including what that person does for work and leisure.

3. Communication with colleagues, patients, and families: Patient and family fear and confusion can often be reduced after establishment of a multi-disciplinary team with daily care coordination and consistent messaging. Breaking down traditional hospital silos to allow for improved coordination of care benefits both the patients and the practitioners.

4. Managing emotional and physical suffering: Introducing social workers, mental health professionals, or pastoral care advocates into the care team as soon as a patient is ready can help manage the emotional and psychosocial needs of patients and their families.

5. Sustaining long term surgeon/patient relationships: As clinicians, we can feel rewarded after restoring functional performance in our patients and by meeting the needs of our patients and families. This can occur both in the short-term during the acute hospital stay and in the long-term as we follow our patients’ progress towards achievement of their ultimate goals.

6. Attend to one’s own well-being and foster resilience. There will never be a substitute in our profession for the human connection between our patients and ourselves as their caregivers, and this connection should be one of the most treasured aspects of our work life. We should seek daily reminders of these positive interactions to nurture our ability to cope with a grueling and challenging field, where the outcomes are not always as ideal as we hope.

For me, STRONG is now a consistent and powerful reminder of why I originally became a doctor in the first place, and I strive to propagate this model of compassionate care to benefit future patients as we move forward together.”

We are at an inflexion point in health care. No amount of individual resilience can withstand a toxic or nonsupportive environment. It is unreasonable to think that simply by taking better care of ourselves we are going to resolve the issue of burnout. We need to rethink our current systems of care and focus our energy on developing those that support our ability to deliver the kind of care we know our patients need and deserve. We have an opportunity to alleviate the suffering many providers are experiencing as they strive to heal their patients. We have an opportunity to improve both physician and patient engagement, develop care delivery systems we know our patients deserve, and restore the deep sense of satisfaction that comes from practicing medicine and surgery. There is abundant expertise within our professional medical and surgical societies. The SVS has the courage and the duty to lead.

Drs. Colman, Kalish, and Sheahan extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, M.D., Scholar in Residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston, Mass., and Clinical Professor of Orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Bibliography

1. Acad Med (2016) 91:338-344

2. Health Aff (2011) 30:1772-1778

3. Patient Educ Couns (2015) 98:1005-10

4. Acad Med (2016) 91:310-316

5. http://www.theschwartzcenter.org/media/Triple-C-Conference-Framework-Tables_FINAL.pdf

6. http://www.theschwartzcenter.org/media/Triple-C-Conference-Recommendations-Report_FINAL1.pdf

7. JAMA (2017) 317: 901-2

8. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2017) 475:1309-14.

It is easy to look at the changes required to mitigate burnout and improve compassionate care and see the burden being placed mainly on the physician. Many of the proposed modifications seem to require the one commodity surgeons lack most, time. Any widespread effort to mitigate the burnout crisis must involve decreasing the barriers to patient care and reducing the physicians’ time constraints.

This may seem daunting, but broad changes in our healthcare system have been implemented in the name of quality, reducing errors, and alleviating trainee fatigue. Burnout can be a similar force for change. Much like the resident’s 80-hour workweek, however, in what manner this change is applied will be the ultimate determinant of the movement’s success.

This series of articles dealt with the adverse consequences of surgeon burnout on both clinicians and their patients, and then presented a conceptual framework to promote workforce well-being. Strategies that the SVS might adopt have been suggested. The central proposal is that helping physicians to deliver compassionate, collaborative care will not only mitigate burnout but also will enhance provider engagement, patient experience, and clinical outcomes, as well as improve the quality and safety of healthcare delivery. It seems reasonable to question if such broad strategic proposals are scalable to individual clinical settings.

The characteristics of compassionate care have been well described by patients, and, not surprisingly, only 53% reported that their last encounter with the health care system was compassionate. In 2014, a multidisciplinary consortium published recommendations for advancing compassionate person- and family-centered care. They detailed the attributes, values, and behaviors of such care, including focusing one’s attention, recognizing nonverbal clues, active listening, demonstrating nonjudgmental interest in the whole person, understanding the context of a person’s disease, and asking about the patient’s chief concerns in addition to their chief complaints. Most significantly, the authors outlined how these attributes could be integrated into existing competency documents such as those provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Entrustable Professional Activities, or the milestones programs of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).

It is but a small step to enhance current criteria for certification, clinical appointment, and privileging by including these professional attributes. Bear in mind that these skills are teachable and easily incorporated into health professional education and clinical care. As for metrics, the Schwartz Compassionate Care Scale is a validated patient-rated questionnaire that reliably measures physicians’ compassion and overall patient satisfaction and is available in the public domain. It also provides a metric that is important to clinicians and, when placed on the hospital dashboard, highlights that compassion is an organizational priority. Such priorities become the fabric of the workforce when organizational leadership installs programs such as values-based recruitment, retention, and promotion as Vivian Lee describes at the University of Utah Health System. Mitigating burnout requires changing the culture in which clinicians work and with whom they work.

Vascular surgeons and their professional surgical societies have a leadership opportunity to design high performing teams. Most patient care models have been structured around traditional medical and surgical departments. This paradigm overlooks the fact that patients do not “get sick” within traditional teaching disciplines but do so across varied medical and surgical specialties. Changes in organizational hierarchy are needed so that team-based care is supported. In addition to physician and nurse clinicians, the new teams would do well to expand to all “caregivers,” i.e. everyone who touches the patient (technologists, interpreters, pharmacists, transport workers, support staff, and administrators).

On the front line

On April 15, 2013, at 2:49 pm, two homemade bombs detonated near the finish line of the Boston Marathon killing three people at the scene and injuring 264 others; the most severe sustaining mutilating lower extremity injuries. Much has been written about the preparedness, the emergency response, and the fact that all those who made it to the hospital survived. Jeffrey Kalish, MD, a vascular surgeon at Boston Medical Center and SVS member, was on the front line that day. We asked him to share his personal experience of caring for the victims through the lens of compassionate collaborative care.

“It has been over four years since I went from being a spectator near the Boston Marathon finish line to rushing directly to the operating rooms at Boston Medical Center to help our teams perform lifesaving procedures on critically ill patients, including amputations and complex vascular repairs. While I have learned a tremendous amount since that experience with regard to limb salvage and amputation, reconstructive techniques, and prosthetics, I will focus here on the care the patients and their families received, the lessons our hospital learned from the weeks and months that followed, and how we modeled this care going forward for all amputation patients at Boston Medical Center.

"Based on lessons from the Boston Marathon bombings, I aligned a multidisciplinary team of health care providers in order to formalize and standardize best practices to benefit our amputation patients. STRONG (Surgery To Rehab Ongoing Needs Group) continues to strive toward the ultimate goal of improving and coordinating care for amputation patients and their families as they transition from the hospital setting to rehabilitation. Some of our guiding principles, along with their positive impacts on patient care and physician well-being, are highlighted below:

1. Sustaining hope with a new mindset: Although surgeons have historically considered amputation as a treatment failure, a more appropriate mindset is that amputation can often be a reconstructive procedure in the surgical armamentarium designed to restore a patient back to full function.

2. Seeing the patient in context: Shared decision making can occur more readily once a surgeon and the care team seek to understand the whole person and their family, including what that person does for work and leisure.

3. Communication with colleagues, patients, and families: Patient and family fear and confusion can often be reduced after establishment of a multi-disciplinary team with daily care coordination and consistent messaging. Breaking down traditional hospital silos to allow for improved coordination of care benefits both the patients and the practitioners.

4. Managing emotional and physical suffering: Introducing social workers, mental health professionals, or pastoral care advocates into the care team as soon as a patient is ready can help manage the emotional and psychosocial needs of patients and their families.

5. Sustaining long term surgeon/patient relationships: As clinicians, we can feel rewarded after restoring functional performance in our patients and by meeting the needs of our patients and families. This can occur both in the short-term during the acute hospital stay and in the long-term as we follow our patients’ progress towards achievement of their ultimate goals.

6. Attend to one’s own well-being and foster resilience. There will never be a substitute in our profession for the human connection between our patients and ourselves as their caregivers, and this connection should be one of the most treasured aspects of our work life. We should seek daily reminders of these positive interactions to nurture our ability to cope with a grueling and challenging field, where the outcomes are not always as ideal as we hope.

For me, STRONG is now a consistent and powerful reminder of why I originally became a doctor in the first place, and I strive to propagate this model of compassionate care to benefit future patients as we move forward together.”

We are at an inflexion point in health care. No amount of individual resilience can withstand a toxic or nonsupportive environment. It is unreasonable to think that simply by taking better care of ourselves we are going to resolve the issue of burnout. We need to rethink our current systems of care and focus our energy on developing those that support our ability to deliver the kind of care we know our patients need and deserve. We have an opportunity to alleviate the suffering many providers are experiencing as they strive to heal their patients. We have an opportunity to improve both physician and patient engagement, develop care delivery systems we know our patients deserve, and restore the deep sense of satisfaction that comes from practicing medicine and surgery. There is abundant expertise within our professional medical and surgical societies. The SVS has the courage and the duty to lead.

Drs. Colman, Kalish, and Sheahan extend their thanks and appreciation for the guidance, resources and support of Michael Goldberg, M.D., Scholar in Residence, Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care, Boston, Mass., and Clinical Professor of Orthopedics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Bibliography

1. Acad Med (2016) 91:338-344

2. Health Aff (2011) 30:1772-1778

3. Patient Educ Couns (2015) 98:1005-10

4. Acad Med (2016) 91:310-316

5. http://www.theschwartzcenter.org/media/Triple-C-Conference-Framework-Tables_FINAL.pdf

6. http://www.theschwartzcenter.org/media/Triple-C-Conference-Recommendations-Report_FINAL1.pdf

7. JAMA (2017) 317: 901-2

8. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2017) 475:1309-14.

Cutaneous laser surgery: Basic caution isn’t enough to prevent lawsuits

SAN DIEGO – Injuries and lawsuits related to laser cosmetic surgery are increasing and potential legal threats are not always easy to predict, according to two dermatologists who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS).

A laser procedure could go smoothly, for example, but the patient might be able to successfully sue if he or she is allowed to drive home after receiving a sedative. Or a physician might get sued because his or her nurse set a laser at the wrong setting and singed a patient.

The risk of a lawsuit is high, H. Ray Jalian, MD, a dermatologist in Los Angeles, said at the meeting. “The reality is that we’re all at some point going to face this.”

The most common procedure litigated was laser hair removal, making up almost 40% of the cases, which is not an indication that this particular procedure is dangerous, Dr. Jalian said. “It’s quite safe, and the complication rate is quite low,” but more of these procedures are being done, he noted. Rejuvenation procedures followed, accounting for 25% of cases.

The alleged injuries sustained from laser surgery included burns (47%), scars (39%), and pigmentation problems (24%). Deaths occurred in just over 2% of the cases. In the study, almost a third of plaintiffs alleged that they were not provided informed consent. Plaintiffs also alleged fraud (9%) and assault/battery (5%), and a family member occasionally sued for loss of consortium (8% of cases). The specialty with the largest percentage of the cases was plastic surgery (26%), followed by dermatology (21%).

Dr. Jalian and his copresenter, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, director of the Dermatology Laser & Cosmetic Center, and director of dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, offered these lessons about the legal risks associated with laser procedures:

• You may have a duty to protect your patient from bad choices.

Physicians aren’t expected to keep patients from making certain bad decisions such as sunbathing after a traditional resurfacing procedure, said Dr. Avram, of the department of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the ASLMS president. But in some cases, he said, the law may expect the physician to step in to prevent harm. For example, he said, a patient who has undergone a fractional ablative laser procedure and has received a sedative should not be allowed to drive home.

• You may get sued even if your employee is at fault.

The 2013 study found physicians were often sued even when they did not perform the laser procedure in question. Nonphysicians such as physician assistants and nurses often perform laser operations, and many states allow them to do so. “Nonphysicians were less likely to be sued even if they were the operators,” Dr. Jalian said. In the study, almost 38% of the 174 analyzed cases involved nonphysician operators, but they were sued in just 26% of the cases. In 33 of the 174 cases in the study, plaintiffs alleged failure to properly hire, train, or supervise staff.

He recommended looking at state laws, which differ greatly in their regulations – or lack of them – regarding the operation of medical lasers. In some cases, physicians must supervise laser use, he said. “But what are the requirements? Can you be available by phone down the street or in the Caribbean?”

Dr. Jalian, Dr. Avram, and a colleague followed up the 2013 study with another study that tracked 175 legal cases from 1999 to 2012 involving alleged injuries from cutaneous laser surgery. During this time period, 75 (43%) involved a nonphysician operating a laser, increasing from 36% in 2008 to 78% in 2012.

In almost two-thirds of cases, the procedures in question were done by nonphysicians outside a “traditional medical setting” such as a salon or spa (JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Apr;150[4]:407-11).

• Delayed side effects could mean delayed lawsuits.

According to Dr. Avram, statutes of limitations – the length of time in which a patient can file a lawsuit – typically last for 2-3 years in malpractice cases. But he said that the period begins when the physician is alleged to have made a mistake or when the patient becomes aware of – or should reasonably be aware of – an injury. Therefore, physicians could face legal trouble over delayed hypopigmentation that appears 6 months after a laser resurfacing treatment, or granulomas that appear years after a filler treatment, he said.

• A signed form is not a cure-all.

It is wise to make patients sign an extensive informed consent form, but this will not protect a physician against a claim of negligence, Dr. Avram said. And the reverse is also true: If a patient did not sign a proper consent form, he or she could still sue even if the procedure went perfectly, he noted.

• Your instincts are worth trusting.

When it comes to lawsuit prevention, Dr. Avram said, “by far the most important thing you can do happens within a minute of when you see the patient. Assess and trust your own intuition and your staff’s intuition. For elective, cosmetic treatments, don’t be afraid to say no. There’s no legal obligation to perform a cosmetic treatment on a patient.”

If you do choose to treat a patient, he advised, be open about the procedure and “maybe even tell them some of the tougher, worse-case scenarios.” If a procedure goes poorly, he said, consider how to fix it. “Many complications can be significantly improved or cleared with timely and appropriate intervention,” he said.

In some cases, refunding the patient’s money can be considered, with the patient signing a release, he said. “Document that you are refunding the money in order to preserve the doctor-patient relationship, not to avoid negligence.”

Dr. Jalian and Dr. Avram reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Injuries and lawsuits related to laser cosmetic surgery are increasing and potential legal threats are not always easy to predict, according to two dermatologists who spoke at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS).

A laser procedure could go smoothly, for example, but the patient might be able to successfully sue if he or she is allowed to drive home after receiving a sedative. Or a physician might get sued because his or her nurse set a laser at the wrong setting and singed a patient.

The risk of a lawsuit is high, H. Ray Jalian, MD, a dermatologist in Los Angeles, said at the meeting. “The reality is that we’re all at some point going to face this.”

The most common procedure litigated was laser hair removal, making up almost 40% of the cases, which is not an indication that this particular procedure is dangerous, Dr. Jalian said. “It’s quite safe, and the complication rate is quite low,” but more of these procedures are being done, he noted. Rejuvenation procedures followed, accounting for 25% of cases.