User login

Mindfulness and child health

If you are struggling to figure out how you, as an individual pediatrician, can make a significant impact on the most common current issues in child health of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, stress, and even adverse childhood experiences, you are not alone. Many of the problems we see in the office appear to stem so much from the culture in which we live that the medical interventions we have to offer seem paltry. Yet we strive to identify and attempt to ameliorate the child’s and family’s distress.

Real physical danger aside, a lot of personal distress is due to negative thoughts about one’s past or fears for one’s future. These thoughts are very important in restraining us from repeating mistakes and preparing us for action to prevent future harm. But the thoughts themselves can be stressful; they may paralyze us with anxiety, take away pleasure, interrupt our sleep, stimulate physiologic stress responses, and have adverse impacts on health. All these effects can occur without actually changing the course of events! How can we advise our patients and their parents to work to balance the protective function of our thoughts against the cost to our well-being?

One promising method you can confidently recommend to both children and their parents to manage stressful thinking is to learn and practice mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to a state of nonreactivity, awareness, focus, attention, and nonjudgment. Noticing thoughts and feelings passing through us with a neutral mind, as if we were watching a movie, rather than taking them personally, is the goal. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, learned from Buddhists, then developed and disseminated a formal program to teach this skill called mindfulness-based stress reduction; it has yielded significant benefits to the emotions and health of adult participants. While everyone can be mindful at times, the ability to enter this state at will and maintain it for a few minutes can be learned, even by preschool children.

How am I going to refer my patients to mindfulness programs, I can hear you saying, when I can’t even get them to standard therapies? Mindfulness in a less-structured format is often part of yoga or Tai Chi, meditation, art therapy, group therapy, or even religious services. Fortunately, parents and educators also can teach children mindfulness. But the first way you can start making this life skill available to your patients is by recommending it to their parents (“The Family ADHD Solution” by Mark Bertin [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011]).

You know that child emotional or behavior problems can cause adult stress. But adult stress also can cause or exacerbate a child’s emotional or behavior problems. Adult caregivers modeling meltdowns are shaping the minds of their children. Studies of teaching mindfulness to parents of children with developmental disabilities, autism, and ADHD, without touching the underlying disorder, show significant reductions in both adult stress and child behavior problems. Parents who can suspend emotion, take some deep breaths, and be thoughtful about the response they want to make instead of reacting impulsively act more reasonably, appear warmer and more compassionate to their children, and are often rewarded with better behavior. Such parents may feel better about themselves and their parenting, may experience less stress, and may themselves sleep better at night!

For children, having an adult simply declare moments to stop, take deep breaths, and notice the sounds, sights, feelings, and smells around them is a good start. Making a routine of taking an “awareness walk” around the block can be another lesson. Eating a food, such as a strawberry, mindfully – observing and savoring every bite – is another natural opportunity to practice increased awareness. One of my favorite tools, having a child shake a glitter globe (like a snow globe that can be made at home) and silently wait for the chaos to subside, “just like their feelings inside,” is soothing and a great metaphor! Abdominal breathing, part of many relaxation exercises, may be hard for young children to master. A parent might try having the child lie down with a stuffed animal on his or her belly and focus on watching it rise and fall while breathing as a way to learn this. For older children, keeping a “gratitude journal” helps focus on the positive, and also has some proven efficacy in relieving depression. Using the “1 Second Everyday” app to video a special moment daily may have a similar effect on sharpening awareness.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

If you are struggling to figure out how you, as an individual pediatrician, can make a significant impact on the most common current issues in child health of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, stress, and even adverse childhood experiences, you are not alone. Many of the problems we see in the office appear to stem so much from the culture in which we live that the medical interventions we have to offer seem paltry. Yet we strive to identify and attempt to ameliorate the child’s and family’s distress.

Real physical danger aside, a lot of personal distress is due to negative thoughts about one’s past or fears for one’s future. These thoughts are very important in restraining us from repeating mistakes and preparing us for action to prevent future harm. But the thoughts themselves can be stressful; they may paralyze us with anxiety, take away pleasure, interrupt our sleep, stimulate physiologic stress responses, and have adverse impacts on health. All these effects can occur without actually changing the course of events! How can we advise our patients and their parents to work to balance the protective function of our thoughts against the cost to our well-being?

One promising method you can confidently recommend to both children and their parents to manage stressful thinking is to learn and practice mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to a state of nonreactivity, awareness, focus, attention, and nonjudgment. Noticing thoughts and feelings passing through us with a neutral mind, as if we were watching a movie, rather than taking them personally, is the goal. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, learned from Buddhists, then developed and disseminated a formal program to teach this skill called mindfulness-based stress reduction; it has yielded significant benefits to the emotions and health of adult participants. While everyone can be mindful at times, the ability to enter this state at will and maintain it for a few minutes can be learned, even by preschool children.

How am I going to refer my patients to mindfulness programs, I can hear you saying, when I can’t even get them to standard therapies? Mindfulness in a less-structured format is often part of yoga or Tai Chi, meditation, art therapy, group therapy, or even religious services. Fortunately, parents and educators also can teach children mindfulness. But the first way you can start making this life skill available to your patients is by recommending it to their parents (“The Family ADHD Solution” by Mark Bertin [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011]).

You know that child emotional or behavior problems can cause adult stress. But adult stress also can cause or exacerbate a child’s emotional or behavior problems. Adult caregivers modeling meltdowns are shaping the minds of their children. Studies of teaching mindfulness to parents of children with developmental disabilities, autism, and ADHD, without touching the underlying disorder, show significant reductions in both adult stress and child behavior problems. Parents who can suspend emotion, take some deep breaths, and be thoughtful about the response they want to make instead of reacting impulsively act more reasonably, appear warmer and more compassionate to their children, and are often rewarded with better behavior. Such parents may feel better about themselves and their parenting, may experience less stress, and may themselves sleep better at night!

For children, having an adult simply declare moments to stop, take deep breaths, and notice the sounds, sights, feelings, and smells around them is a good start. Making a routine of taking an “awareness walk” around the block can be another lesson. Eating a food, such as a strawberry, mindfully – observing and savoring every bite – is another natural opportunity to practice increased awareness. One of my favorite tools, having a child shake a glitter globe (like a snow globe that can be made at home) and silently wait for the chaos to subside, “just like their feelings inside,” is soothing and a great metaphor! Abdominal breathing, part of many relaxation exercises, may be hard for young children to master. A parent might try having the child lie down with a stuffed animal on his or her belly and focus on watching it rise and fall while breathing as a way to learn this. For older children, keeping a “gratitude journal” helps focus on the positive, and also has some proven efficacy in relieving depression. Using the “1 Second Everyday” app to video a special moment daily may have a similar effect on sharpening awareness.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

If you are struggling to figure out how you, as an individual pediatrician, can make a significant impact on the most common current issues in child health of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, stress, and even adverse childhood experiences, you are not alone. Many of the problems we see in the office appear to stem so much from the culture in which we live that the medical interventions we have to offer seem paltry. Yet we strive to identify and attempt to ameliorate the child’s and family’s distress.

Real physical danger aside, a lot of personal distress is due to negative thoughts about one’s past or fears for one’s future. These thoughts are very important in restraining us from repeating mistakes and preparing us for action to prevent future harm. But the thoughts themselves can be stressful; they may paralyze us with anxiety, take away pleasure, interrupt our sleep, stimulate physiologic stress responses, and have adverse impacts on health. All these effects can occur without actually changing the course of events! How can we advise our patients and their parents to work to balance the protective function of our thoughts against the cost to our well-being?

One promising method you can confidently recommend to both children and their parents to manage stressful thinking is to learn and practice mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to a state of nonreactivity, awareness, focus, attention, and nonjudgment. Noticing thoughts and feelings passing through us with a neutral mind, as if we were watching a movie, rather than taking them personally, is the goal. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, learned from Buddhists, then developed and disseminated a formal program to teach this skill called mindfulness-based stress reduction; it has yielded significant benefits to the emotions and health of adult participants. While everyone can be mindful at times, the ability to enter this state at will and maintain it for a few minutes can be learned, even by preschool children.

How am I going to refer my patients to mindfulness programs, I can hear you saying, when I can’t even get them to standard therapies? Mindfulness in a less-structured format is often part of yoga or Tai Chi, meditation, art therapy, group therapy, or even religious services. Fortunately, parents and educators also can teach children mindfulness. But the first way you can start making this life skill available to your patients is by recommending it to their parents (“The Family ADHD Solution” by Mark Bertin [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011]).

You know that child emotional or behavior problems can cause adult stress. But adult stress also can cause or exacerbate a child’s emotional or behavior problems. Adult caregivers modeling meltdowns are shaping the minds of their children. Studies of teaching mindfulness to parents of children with developmental disabilities, autism, and ADHD, without touching the underlying disorder, show significant reductions in both adult stress and child behavior problems. Parents who can suspend emotion, take some deep breaths, and be thoughtful about the response they want to make instead of reacting impulsively act more reasonably, appear warmer and more compassionate to their children, and are often rewarded with better behavior. Such parents may feel better about themselves and their parenting, may experience less stress, and may themselves sleep better at night!

For children, having an adult simply declare moments to stop, take deep breaths, and notice the sounds, sights, feelings, and smells around them is a good start. Making a routine of taking an “awareness walk” around the block can be another lesson. Eating a food, such as a strawberry, mindfully – observing and savoring every bite – is another natural opportunity to practice increased awareness. One of my favorite tools, having a child shake a glitter globe (like a snow globe that can be made at home) and silently wait for the chaos to subside, “just like their feelings inside,” is soothing and a great metaphor! Abdominal breathing, part of many relaxation exercises, may be hard for young children to master. A parent might try having the child lie down with a stuffed animal on his or her belly and focus on watching it rise and fall while breathing as a way to learn this. For older children, keeping a “gratitude journal” helps focus on the positive, and also has some proven efficacy in relieving depression. Using the “1 Second Everyday” app to video a special moment daily may have a similar effect on sharpening awareness.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

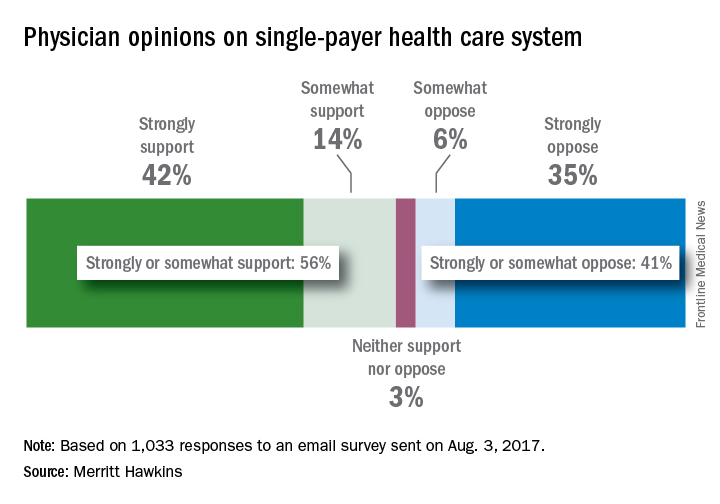

Physicians shift on support of single-payer system

, according to a recent survey by physician recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins.

A single-payer system was “strongly supported” by 42% and “somewhat supported” by 14% of the 1,033 physicians who responded to the email survey, which was sent out on Aug. 3. Compared with the 41% who expressed opposition to a single payer – 35% “strongly opposed” and 6% “somewhat opposed” – the total of 56% supporting it was more than enough to cover the margin of error of ±3.1%. The remaining 3% of physicians said that they neither support nor oppose a single-payer system, Merritt Hawkins reported.

In a survey the company conducted in 2008, just 42% of physicians supported a single-payer system and 58% opposed it. “Physicians appear to have evolved on single payer,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “Whether they are enthusiastic about it, are merely resigned to it, or are just seeking clarity, single payer is a concept many physicians appear to be embracing.”

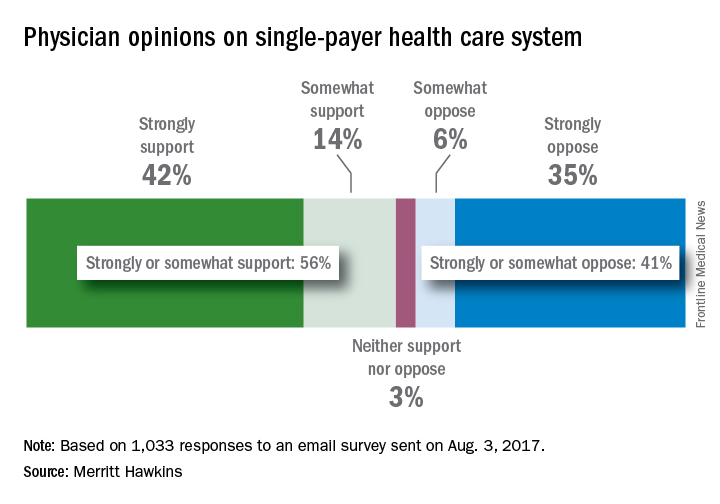

, according to a recent survey by physician recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins.

A single-payer system was “strongly supported” by 42% and “somewhat supported” by 14% of the 1,033 physicians who responded to the email survey, which was sent out on Aug. 3. Compared with the 41% who expressed opposition to a single payer – 35% “strongly opposed” and 6% “somewhat opposed” – the total of 56% supporting it was more than enough to cover the margin of error of ±3.1%. The remaining 3% of physicians said that they neither support nor oppose a single-payer system, Merritt Hawkins reported.

In a survey the company conducted in 2008, just 42% of physicians supported a single-payer system and 58% opposed it. “Physicians appear to have evolved on single payer,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “Whether they are enthusiastic about it, are merely resigned to it, or are just seeking clarity, single payer is a concept many physicians appear to be embracing.”

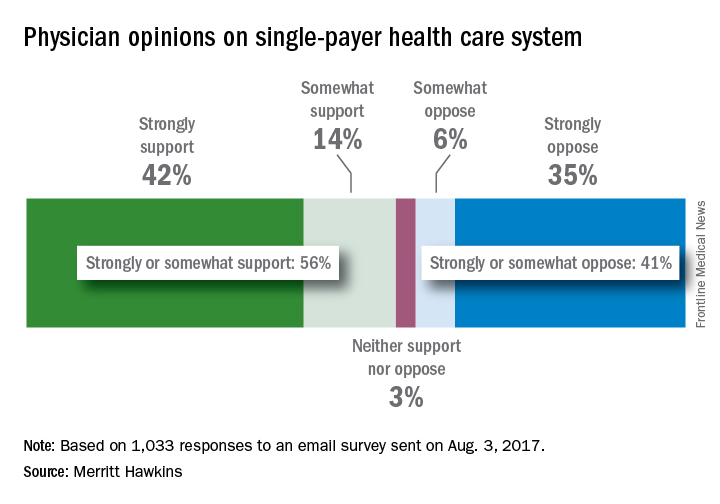

, according to a recent survey by physician recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins.

A single-payer system was “strongly supported” by 42% and “somewhat supported” by 14% of the 1,033 physicians who responded to the email survey, which was sent out on Aug. 3. Compared with the 41% who expressed opposition to a single payer – 35% “strongly opposed” and 6% “somewhat opposed” – the total of 56% supporting it was more than enough to cover the margin of error of ±3.1%. The remaining 3% of physicians said that they neither support nor oppose a single-payer system, Merritt Hawkins reported.

In a survey the company conducted in 2008, just 42% of physicians supported a single-payer system and 58% opposed it. “Physicians appear to have evolved on single payer,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “Whether they are enthusiastic about it, are merely resigned to it, or are just seeking clarity, single payer is a concept many physicians appear to be embracing.”

QI enthusiast to QI leader: Luci Leykum, MD

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

Editor’s Note: This ongoing series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Luci Leykum, MD, division chief, general and hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio.

Luci Leykum, MD, MBA, MSc, FACP, SFHM, became familiar with inpatient medicine at age 9 years, when her grandfather contracted non-AB hepatitis from a postoperative blood transfusion. In the ensuing years, Dr. Leykum visited her grandfather during his frequent hospitalizations, keeping a close watch on the physicians charged with his care.

“It was when HIV and what we now think is hep C were just emerging, and there was a lot to figure out,” Dr. Leykum recalled of these formative experiences. Her interests in problem-solving, human relationships, and physiology led to enrollment years later as a medical student at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where her keen observation skills led to a life-changing, “how did we get here?” moment.

Shortly before Dr. Leykum entered residency in 1999, New York Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital announced that they were merging. The timing was ideal for someone with Dr. Leykum’s acumen in business and medicine, and, as a resident, she began working with the chief medical officer for quality at the new, combined health system to identify quality improvement opportunities.

From there, the projects began pouring in: tracking phone hold times for residents; updating policies to reduce staff exposure to blood-borne pathogens and other infectious diseases; and monitoring flow through the hospitalization process. “In the progression of a few years, I was able to see important aspects of how the system came together,” said Dr. Leykum, “and how decisions were made around standards and metrics for the system as a whole and for its multiple individual hospital facilities.”

In 2004, two years out of residency, Dr. Leykum relocated to San Antonio to accept a clinician investigator position with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System/University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Research, she said, has allowed her to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that impact systems of health care. She sees the complementary sides of quality improvement and research.

“Through our quality improvement initiatives, we can evaluate and improve specific aspects of care, in specific contexts or systems,” Dr. Leykum explained. “In our research projects, we look for new insights that can be more broadly applied across contexts. With funding, you are able to look at things with a scope, depth, or time horizon beyond what you typically have with a QI project.”

Since joining the UTHSCSA/VA system, Dr. Leykum has participated in more than 15 externally funded studies, 6 as principal investigator. She joined SHM’s research committee in 2009, serving as chair for 6 years, and is currently working with the committee to implement the Improving Hospital Outcomes through Patient Engagement (i-HOPE) Study.

I-HOPE, funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, is a project to develop a patient- and stakeholder-partnered research agenda to improve the care of hospitalized patients. Dr. Leykum is also involved in implementing a collaborative care model at University Health System, a patient-partnered, interprofessional model that “focuses on improving interconnections, relationships, and sense making,” in the hospital system, she explained. “It was motivated strongly by our desire to improve our partnerships with patients and other providers in the hospital as a strategy to improve care.”

In addition to the many professional responsibilities she manages as division chief of general and hospital medicine at UTHSCSA – a position she has held for hospital medicine since 2006 and for the combined division since 2016 – Dr. Leykum continues to play an integral role in multiple academic and research initiatives for SHM.

She encourages anyone considering a concentration in QI and research to seek opportunities to actively learn these skills and, more importantly, let other people know their interests.

“The value of talking with colleagues at other places is so high,” she said. “When you actively reach out, you find that most people are happy to share their knowledge. Networking is one of the best parts of the SHM annual meeting – there’s an energy and excitement in learning about what others are doing. Wander into the poster and special interest sessions and see what people are working on, get email addresses, and participate on committees.”

The Search for Meaning After Surviving Cancer

Until now, research on meaning in cancer patients has focused mostly on patients with advanced cancer, who may be facing existential issues like the desire for hastened death. But as more people survive cancer, a sense of meaning is also an important issue for them, say researchers from VU University in Amsterdam. Those patients may be facing “fundamental uncertainties,” such as possible recurrence, long-term adverse effects of treatment, and physical, personal, and social losses. Helping them come to terms with those stressors can have benefits: higher psychological well-being, more successful adjustment, better quality of life.

Related: Social Interaction May Enhance Patient Survival After Chemotherapy

Noting the results of meaning-centered group psychotherapy (MCGP) for patients with advanced cancer, the researchers decided to compare MCGP with supportive group therapy (SGP) and usual care. Their study included 170 survivors who were diagnosed in the past 5 years, were treated with curative intent, and had completed their main treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy). Patients also had to have an expressed need for psychological care and at least 1 psychosocial condition, such as depressed mood, anxiety, or coping issues.

The researchers adapted the original MCGP intervention with different terminologies and topics more relevant for survivors (MCGP-CS [cancer survivors]). For instance, the topic “a good and meaningful death” was replaced by “carrying on in life despite limitations.” Topics included “The story of our life as a source of meaning: things we have done and want to do in the future.” The researchers also added mindfulness exercises to help patients with introspection.

Related: Women Living Longer With Metastatic Breast Cancer

The intervention consisted of 8 once-weekly sessions using didactics, group discussions, experimental exercises, and homework assignments. The SGP sessions, also 8 once-weekly meetings, did not pay specific attention to meaning. The psychotherapists leading the sessions, while maintaining an “unconditionally positive regard and empathetic understanding,” were trained to avoid group discussions on meaning-related topics. The primary outcome, measured before and after the intervention, then at 3 and 6 months, was personal meaning; secondary outcomes included psychological well-being, adjustment to cancer, optimism, and quality of life.

The researchers found “evidence for the efficacy of MCGP-CS to improve personal meaning among cancer survivors,” in both the short and longer terms. MCGP-CS participants scored significantly higher on goal-orientedness, psychological well-being, and adjustment to cancer. At 6 months, the intervention group also had lower scores for psychological distress and depressive symptoms.

Source:

van der Spek N, Vos J, van Uden-Kraan CF, et al. 2017;47(11):1990-2001.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000447.

Until now, research on meaning in cancer patients has focused mostly on patients with advanced cancer, who may be facing existential issues like the desire for hastened death. But as more people survive cancer, a sense of meaning is also an important issue for them, say researchers from VU University in Amsterdam. Those patients may be facing “fundamental uncertainties,” such as possible recurrence, long-term adverse effects of treatment, and physical, personal, and social losses. Helping them come to terms with those stressors can have benefits: higher psychological well-being, more successful adjustment, better quality of life.

Related: Social Interaction May Enhance Patient Survival After Chemotherapy

Noting the results of meaning-centered group psychotherapy (MCGP) for patients with advanced cancer, the researchers decided to compare MCGP with supportive group therapy (SGP) and usual care. Their study included 170 survivors who were diagnosed in the past 5 years, were treated with curative intent, and had completed their main treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy). Patients also had to have an expressed need for psychological care and at least 1 psychosocial condition, such as depressed mood, anxiety, or coping issues.

The researchers adapted the original MCGP intervention with different terminologies and topics more relevant for survivors (MCGP-CS [cancer survivors]). For instance, the topic “a good and meaningful death” was replaced by “carrying on in life despite limitations.” Topics included “The story of our life as a source of meaning: things we have done and want to do in the future.” The researchers also added mindfulness exercises to help patients with introspection.

Related: Women Living Longer With Metastatic Breast Cancer

The intervention consisted of 8 once-weekly sessions using didactics, group discussions, experimental exercises, and homework assignments. The SGP sessions, also 8 once-weekly meetings, did not pay specific attention to meaning. The psychotherapists leading the sessions, while maintaining an “unconditionally positive regard and empathetic understanding,” were trained to avoid group discussions on meaning-related topics. The primary outcome, measured before and after the intervention, then at 3 and 6 months, was personal meaning; secondary outcomes included psychological well-being, adjustment to cancer, optimism, and quality of life.

The researchers found “evidence for the efficacy of MCGP-CS to improve personal meaning among cancer survivors,” in both the short and longer terms. MCGP-CS participants scored significantly higher on goal-orientedness, psychological well-being, and adjustment to cancer. At 6 months, the intervention group also had lower scores for psychological distress and depressive symptoms.

Source:

van der Spek N, Vos J, van Uden-Kraan CF, et al. 2017;47(11):1990-2001.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000447.

Until now, research on meaning in cancer patients has focused mostly on patients with advanced cancer, who may be facing existential issues like the desire for hastened death. But as more people survive cancer, a sense of meaning is also an important issue for them, say researchers from VU University in Amsterdam. Those patients may be facing “fundamental uncertainties,” such as possible recurrence, long-term adverse effects of treatment, and physical, personal, and social losses. Helping them come to terms with those stressors can have benefits: higher psychological well-being, more successful adjustment, better quality of life.

Related: Social Interaction May Enhance Patient Survival After Chemotherapy

Noting the results of meaning-centered group psychotherapy (MCGP) for patients with advanced cancer, the researchers decided to compare MCGP with supportive group therapy (SGP) and usual care. Their study included 170 survivors who were diagnosed in the past 5 years, were treated with curative intent, and had completed their main treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy). Patients also had to have an expressed need for psychological care and at least 1 psychosocial condition, such as depressed mood, anxiety, or coping issues.

The researchers adapted the original MCGP intervention with different terminologies and topics more relevant for survivors (MCGP-CS [cancer survivors]). For instance, the topic “a good and meaningful death” was replaced by “carrying on in life despite limitations.” Topics included “The story of our life as a source of meaning: things we have done and want to do in the future.” The researchers also added mindfulness exercises to help patients with introspection.

Related: Women Living Longer With Metastatic Breast Cancer

The intervention consisted of 8 once-weekly sessions using didactics, group discussions, experimental exercises, and homework assignments. The SGP sessions, also 8 once-weekly meetings, did not pay specific attention to meaning. The psychotherapists leading the sessions, while maintaining an “unconditionally positive regard and empathetic understanding,” were trained to avoid group discussions on meaning-related topics. The primary outcome, measured before and after the intervention, then at 3 and 6 months, was personal meaning; secondary outcomes included psychological well-being, adjustment to cancer, optimism, and quality of life.

The researchers found “evidence for the efficacy of MCGP-CS to improve personal meaning among cancer survivors,” in both the short and longer terms. MCGP-CS participants scored significantly higher on goal-orientedness, psychological well-being, and adjustment to cancer. At 6 months, the intervention group also had lower scores for psychological distress and depressive symptoms.

Source:

van der Spek N, Vos J, van Uden-Kraan CF, et al. 2017;47(11):1990-2001.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000447.

Morning rituals

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” – Annie Dillard

It’s 4:40 a.m. and I’ve got two items checked off my list. As I stir my coffee, made the same way each day, I’m engaged in my morning ritual. It begins at 4:30 a.m. and ends with me ready for whatever comes that day.

In our life-hacking world, morning rituals are hotter than my mug of Italian roast. Blog posts, magazine articles, podcasts, and books, such as the New York Times best-selling “Make Your Bed,” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2017) written by a former Navy SEAL, all argue that the secret to a successful day, and life, lies in the start. But do morning rituals apply to us doctors?

Dr. William Osler, the father of modern medicine, had the answer a century ago: “The day [can] be predicted from the first waking hour. The start is everything,” he advised Yale medical students in his “Way of Life” address. “Live with day-tight compartments,” and focus on “what lies clearly at hand.” He encouraged them to develop focus so they might avoid “indecision and worry,” and fluster and flurry. Today, we call it “mindfulness,” so we might avoid “burnout.”

Dr. Osler, who read Ben Franklin, no doubt would have been familiar with Franklin’s recommendations: 5 a.m.: “Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness [prayer]! Contrive day’s business and take the resolution of the day; prosecute the present study, and breakfast.” Tested by over 200 years of self-help seekers, this is a good start. Through years of research and experimentation, I’ve refined this to the five morning activities that matter most:

2. Reflect on yesterday. Your brain is coming online in the few minutes after waking; while booting, review what happened yesterday. According to an article on-line in the Harvard Business Review (hbr.org), top CEOs make a habit of reviewing their actions and decisions to deconstruct both successes and failures. Replaying your day, like reviewing game film, is key to getting better.

3. Exercise. Physical activity improves memory, and cognition and aerobics are particularly effective. I vary both my activities and length of time in the gym. Ten minutes, if done all-out, might be all you need.

4. Preview and plan. In the excellent “How to Have a Good Day,” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016) author Caroline Webb recommends an approach from three angles: “Aim, Attitude, and Attention.” Aim: What are the most important activities today? Who will you meet? What might you say to be successful? Attitude is key and often overlooked. Perhaps you have a patient you’d prefer not to see or a colleague with whom you need to have a difficult conversation. Reflect on how your attitude will impact the outcome. Lastly, attention must be paid. It’s as relevant today as when Dr. Osler recommended it. What must you focus on today to be successful?

5. Breathe deeply. Developing the habit of mindful breathing can help you become more resilient and focused. Spend 10-30 minutes breathing deeply and mindfully. You can take this time to pray as Franklin did or for priming as self-help guru Tony Robbins recommends today. Whichever you choose, be deliberate and consistent.

I’m invariably energized when I finish my morning routine. Even on my worst procrastination days, I have the satisfaction of getting at least five things done. Much of today will be out of my control: Patients will arrive late and surgeries might run over. But this morning was all mine. By faithfully carrying out this ritual I’m not only ready each day, I’m better each day.

What’s your morning ritual?

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” – Annie Dillard

It’s 4:40 a.m. and I’ve got two items checked off my list. As I stir my coffee, made the same way each day, I’m engaged in my morning ritual. It begins at 4:30 a.m. and ends with me ready for whatever comes that day.

In our life-hacking world, morning rituals are hotter than my mug of Italian roast. Blog posts, magazine articles, podcasts, and books, such as the New York Times best-selling “Make Your Bed,” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2017) written by a former Navy SEAL, all argue that the secret to a successful day, and life, lies in the start. But do morning rituals apply to us doctors?

Dr. William Osler, the father of modern medicine, had the answer a century ago: “The day [can] be predicted from the first waking hour. The start is everything,” he advised Yale medical students in his “Way of Life” address. “Live with day-tight compartments,” and focus on “what lies clearly at hand.” He encouraged them to develop focus so they might avoid “indecision and worry,” and fluster and flurry. Today, we call it “mindfulness,” so we might avoid “burnout.”

Dr. Osler, who read Ben Franklin, no doubt would have been familiar with Franklin’s recommendations: 5 a.m.: “Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness [prayer]! Contrive day’s business and take the resolution of the day; prosecute the present study, and breakfast.” Tested by over 200 years of self-help seekers, this is a good start. Through years of research and experimentation, I’ve refined this to the five morning activities that matter most:

2. Reflect on yesterday. Your brain is coming online in the few minutes after waking; while booting, review what happened yesterday. According to an article on-line in the Harvard Business Review (hbr.org), top CEOs make a habit of reviewing their actions and decisions to deconstruct both successes and failures. Replaying your day, like reviewing game film, is key to getting better.

3. Exercise. Physical activity improves memory, and cognition and aerobics are particularly effective. I vary both my activities and length of time in the gym. Ten minutes, if done all-out, might be all you need.

4. Preview and plan. In the excellent “How to Have a Good Day,” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016) author Caroline Webb recommends an approach from three angles: “Aim, Attitude, and Attention.” Aim: What are the most important activities today? Who will you meet? What might you say to be successful? Attitude is key and often overlooked. Perhaps you have a patient you’d prefer not to see or a colleague with whom you need to have a difficult conversation. Reflect on how your attitude will impact the outcome. Lastly, attention must be paid. It’s as relevant today as when Dr. Osler recommended it. What must you focus on today to be successful?

5. Breathe deeply. Developing the habit of mindful breathing can help you become more resilient and focused. Spend 10-30 minutes breathing deeply and mindfully. You can take this time to pray as Franklin did or for priming as self-help guru Tony Robbins recommends today. Whichever you choose, be deliberate and consistent.

I’m invariably energized when I finish my morning routine. Even on my worst procrastination days, I have the satisfaction of getting at least five things done. Much of today will be out of my control: Patients will arrive late and surgeries might run over. But this morning was all mine. By faithfully carrying out this ritual I’m not only ready each day, I’m better each day.

What’s your morning ritual?

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” – Annie Dillard

It’s 4:40 a.m. and I’ve got two items checked off my list. As I stir my coffee, made the same way each day, I’m engaged in my morning ritual. It begins at 4:30 a.m. and ends with me ready for whatever comes that day.

In our life-hacking world, morning rituals are hotter than my mug of Italian roast. Blog posts, magazine articles, podcasts, and books, such as the New York Times best-selling “Make Your Bed,” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2017) written by a former Navy SEAL, all argue that the secret to a successful day, and life, lies in the start. But do morning rituals apply to us doctors?

Dr. William Osler, the father of modern medicine, had the answer a century ago: “The day [can] be predicted from the first waking hour. The start is everything,” he advised Yale medical students in his “Way of Life” address. “Live with day-tight compartments,” and focus on “what lies clearly at hand.” He encouraged them to develop focus so they might avoid “indecision and worry,” and fluster and flurry. Today, we call it “mindfulness,” so we might avoid “burnout.”

Dr. Osler, who read Ben Franklin, no doubt would have been familiar with Franklin’s recommendations: 5 a.m.: “Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness [prayer]! Contrive day’s business and take the resolution of the day; prosecute the present study, and breakfast.” Tested by over 200 years of self-help seekers, this is a good start. Through years of research and experimentation, I’ve refined this to the five morning activities that matter most:

2. Reflect on yesterday. Your brain is coming online in the few minutes after waking; while booting, review what happened yesterday. According to an article on-line in the Harvard Business Review (hbr.org), top CEOs make a habit of reviewing their actions and decisions to deconstruct both successes and failures. Replaying your day, like reviewing game film, is key to getting better.

3. Exercise. Physical activity improves memory, and cognition and aerobics are particularly effective. I vary both my activities and length of time in the gym. Ten minutes, if done all-out, might be all you need.

4. Preview and plan. In the excellent “How to Have a Good Day,” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2016) author Caroline Webb recommends an approach from three angles: “Aim, Attitude, and Attention.” Aim: What are the most important activities today? Who will you meet? What might you say to be successful? Attitude is key and often overlooked. Perhaps you have a patient you’d prefer not to see or a colleague with whom you need to have a difficult conversation. Reflect on how your attitude will impact the outcome. Lastly, attention must be paid. It’s as relevant today as when Dr. Osler recommended it. What must you focus on today to be successful?

5. Breathe deeply. Developing the habit of mindful breathing can help you become more resilient and focused. Spend 10-30 minutes breathing deeply and mindfully. You can take this time to pray as Franklin did or for priming as self-help guru Tony Robbins recommends today. Whichever you choose, be deliberate and consistent.

I’m invariably energized when I finish my morning routine. Even on my worst procrastination days, I have the satisfaction of getting at least five things done. Much of today will be out of my control: Patients will arrive late and surgeries might run over. But this morning was all mine. By faithfully carrying out this ritual I’m not only ready each day, I’m better each day.

What’s your morning ritual?

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Nurse education boosts proper use of VTE prophylaxis

Online education programs for nurses can improve the administration of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism (VTE), a new study suggests.

The research was spurred by a documented need to boost the administration of prescribed VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients.

Data had shown that patients’ refusal of VTE prophylaxis frequently resulted in nurses not administering the prescribed therapy.

The new research indicates that online education modules helped nurses communicate to patients the need for VTE prophylaxis and therefore improved rates of use.

“We teach in hopes of improving patient care, but there’s actually very little evidence that online professional education can have a measurable impact. Our results show that it does,” said Elliott Haut, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Haut and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE.

For this study, the researchers developed 2 online education modules about the importance of pharmacologic VTE prevention and tactics for better communicating its importance to patients.

One of the modules was “dynamic,” requiring nurses to select responses to clinical scenarios, such as how to respond to a patient who was refusing a prophylactic medication dose. The other module was “static,” involving a PowerPoint slide show with a traditional voice-over explaining the information.

The study included 933 permanently employed nurses on 21 medical or surgical floors at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Between April 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015, 445 nurses on 11 of the floors were randomized to the dynamic education arm of the study, and 488 nurses on 10 floors were enrolled in the static arm.

To track non-administration of VTE prophylaxis, the researchers retrieved data from the hospital’s electronic health record system. The team collected data for 1 year and divided it into 3 time periods: baseline, during the educational intervention, and post-education.

Over the entire study period, 214,478 doses of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis were prescribed to patients on the 21 hospital floors.

After education, non-administration of prescribed VTE prophylaxis decreased from 12.4% to 11.1% (conditional odds ratio [cOR]=0.87, P=0.002).

Nurses who completed the dynamic education module saw a greater reduction in non-administration—from 10.8% to 9.2% (cOR=0.83)—than nurses who completed the static education module—14.5% to 13.5% (cOR=0.92). However, the difference between the study arms was not significant (P=0.26).

“Our study adds to evidence that the way something is taught to professionals has a great influence on whether they retain information and apply it,” said Brandyn Lau, of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Active learning seems to get better results than passive learning, showing that it’s not just what you teach, but also how you teach it.”

“Now that we’ve shown the modules can be effective in improving practice, we want to make [them] available to the more than 3 million nurses practicing in the US,” Dr Haut added. ![]()

Online education programs for nurses can improve the administration of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism (VTE), a new study suggests.

The research was spurred by a documented need to boost the administration of prescribed VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients.

Data had shown that patients’ refusal of VTE prophylaxis frequently resulted in nurses not administering the prescribed therapy.

The new research indicates that online education modules helped nurses communicate to patients the need for VTE prophylaxis and therefore improved rates of use.

“We teach in hopes of improving patient care, but there’s actually very little evidence that online professional education can have a measurable impact. Our results show that it does,” said Elliott Haut, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Haut and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE.

For this study, the researchers developed 2 online education modules about the importance of pharmacologic VTE prevention and tactics for better communicating its importance to patients.

One of the modules was “dynamic,” requiring nurses to select responses to clinical scenarios, such as how to respond to a patient who was refusing a prophylactic medication dose. The other module was “static,” involving a PowerPoint slide show with a traditional voice-over explaining the information.

The study included 933 permanently employed nurses on 21 medical or surgical floors at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Between April 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015, 445 nurses on 11 of the floors were randomized to the dynamic education arm of the study, and 488 nurses on 10 floors were enrolled in the static arm.

To track non-administration of VTE prophylaxis, the researchers retrieved data from the hospital’s electronic health record system. The team collected data for 1 year and divided it into 3 time periods: baseline, during the educational intervention, and post-education.

Over the entire study period, 214,478 doses of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis were prescribed to patients on the 21 hospital floors.

After education, non-administration of prescribed VTE prophylaxis decreased from 12.4% to 11.1% (conditional odds ratio [cOR]=0.87, P=0.002).

Nurses who completed the dynamic education module saw a greater reduction in non-administration—from 10.8% to 9.2% (cOR=0.83)—than nurses who completed the static education module—14.5% to 13.5% (cOR=0.92). However, the difference between the study arms was not significant (P=0.26).

“Our study adds to evidence that the way something is taught to professionals has a great influence on whether they retain information and apply it,” said Brandyn Lau, of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Active learning seems to get better results than passive learning, showing that it’s not just what you teach, but also how you teach it.”

“Now that we’ve shown the modules can be effective in improving practice, we want to make [them] available to the more than 3 million nurses practicing in the US,” Dr Haut added. ![]()

Online education programs for nurses can improve the administration of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism (VTE), a new study suggests.

The research was spurred by a documented need to boost the administration of prescribed VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients.

Data had shown that patients’ refusal of VTE prophylaxis frequently resulted in nurses not administering the prescribed therapy.

The new research indicates that online education modules helped nurses communicate to patients the need for VTE prophylaxis and therefore improved rates of use.

“We teach in hopes of improving patient care, but there’s actually very little evidence that online professional education can have a measurable impact. Our results show that it does,” said Elliott Haut, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Haut and his colleagues reported these results in PLOS ONE.

For this study, the researchers developed 2 online education modules about the importance of pharmacologic VTE prevention and tactics for better communicating its importance to patients.

One of the modules was “dynamic,” requiring nurses to select responses to clinical scenarios, such as how to respond to a patient who was refusing a prophylactic medication dose. The other module was “static,” involving a PowerPoint slide show with a traditional voice-over explaining the information.

The study included 933 permanently employed nurses on 21 medical or surgical floors at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Between April 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015, 445 nurses on 11 of the floors were randomized to the dynamic education arm of the study, and 488 nurses on 10 floors were enrolled in the static arm.

To track non-administration of VTE prophylaxis, the researchers retrieved data from the hospital’s electronic health record system. The team collected data for 1 year and divided it into 3 time periods: baseline, during the educational intervention, and post-education.

Over the entire study period, 214,478 doses of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis were prescribed to patients on the 21 hospital floors.

After education, non-administration of prescribed VTE prophylaxis decreased from 12.4% to 11.1% (conditional odds ratio [cOR]=0.87, P=0.002).

Nurses who completed the dynamic education module saw a greater reduction in non-administration—from 10.8% to 9.2% (cOR=0.83)—than nurses who completed the static education module—14.5% to 13.5% (cOR=0.92). However, the difference between the study arms was not significant (P=0.26).

“Our study adds to evidence that the way something is taught to professionals has a great influence on whether they retain information and apply it,” said Brandyn Lau, of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Active learning seems to get better results than passive learning, showing that it’s not just what you teach, but also how you teach it.”

“Now that we’ve shown the modules can be effective in improving practice, we want to make [them] available to the more than 3 million nurses practicing in the US,” Dr Haut added. ![]()

Drug granted priority review for CTCL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to a supplemental biologics license application (sBLA) seeking approval for brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) as a treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA plans to make a decision on the sBLA for brentuximab vedotin by December 16, 2017.

The sBLA is supported by data from the phase 3 ALCANZA trial and a pair of phase 2 investigator-sponsored trials.

About brentuximab vedotin

Brentuximab vedotin is an antibody-drug conjugate directed to CD30, which is expressed on skin lesions in approximately 50% of patients with CTCL. The drug is being developed by Seattle Genetics and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Brentuximab vedotin is currently FDA-approved for 3 indications.

The drug is approved to treat patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) or after failure of at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-HSCT candidates. Brentuximab vedotin initially had accelerated approval for this indication, but it was later converted to full approval.

Brentuximab vedotin also has full approval as consolidation for patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma who have a high risk of relapse or progression after auto-HSCT.

And the drug has accelerated approval for the treatment of patients with systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (sALCL) after failure of at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. This accelerated approval is based on overall response rate. Continued approval for the sALCL indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

Brentuximab vedotin previously received breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA for the treatment of patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides (MF) and patients with primary cutaneous ALCL who require systemic therapy and have received 1 prior systemic therapy.

Brentuximab vedotin also has orphan drug designation from the FDA for the treatment of MF. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to a supplemental biologics license application (sBLA) seeking approval for brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) as a treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA plans to make a decision on the sBLA for brentuximab vedotin by December 16, 2017.

The sBLA is supported by data from the phase 3 ALCANZA trial and a pair of phase 2 investigator-sponsored trials.

About brentuximab vedotin

Brentuximab vedotin is an antibody-drug conjugate directed to CD30, which is expressed on skin lesions in approximately 50% of patients with CTCL. The drug is being developed by Seattle Genetics and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Brentuximab vedotin is currently FDA-approved for 3 indications.

The drug is approved to treat patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) or after failure of at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-HSCT candidates. Brentuximab vedotin initially had accelerated approval for this indication, but it was later converted to full approval.

Brentuximab vedotin also has full approval as consolidation for patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma who have a high risk of relapse or progression after auto-HSCT.

And the drug has accelerated approval for the treatment of patients with systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (sALCL) after failure of at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. This accelerated approval is based on overall response rate. Continued approval for the sALCL indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

Brentuximab vedotin previously received breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA for the treatment of patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides (MF) and patients with primary cutaneous ALCL who require systemic therapy and have received 1 prior systemic therapy.

Brentuximab vedotin also has orphan drug designation from the FDA for the treatment of MF. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review to a supplemental biologics license application (sBLA) seeking approval for brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) as a treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA plans to make a decision on the sBLA for brentuximab vedotin by December 16, 2017.

The sBLA is supported by data from the phase 3 ALCANZA trial and a pair of phase 2 investigator-sponsored trials.

About brentuximab vedotin

Brentuximab vedotin is an antibody-drug conjugate directed to CD30, which is expressed on skin lesions in approximately 50% of patients with CTCL. The drug is being developed by Seattle Genetics and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Brentuximab vedotin is currently FDA-approved for 3 indications.

The drug is approved to treat patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) or after failure of at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-HSCT candidates. Brentuximab vedotin initially had accelerated approval for this indication, but it was later converted to full approval.

Brentuximab vedotin also has full approval as consolidation for patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma who have a high risk of relapse or progression after auto-HSCT.

And the drug has accelerated approval for the treatment of patients with systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (sALCL) after failure of at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. This accelerated approval is based on overall response rate. Continued approval for the sALCL indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

Brentuximab vedotin previously received breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA for the treatment of patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides (MF) and patients with primary cutaneous ALCL who require systemic therapy and have received 1 prior systemic therapy.

Brentuximab vedotin also has orphan drug designation from the FDA for the treatment of MF. ![]()

Thrombotic events prompt device recall

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced that Cook Medical Inc. is recalling the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft.

The company found that when the device is used for the treatment of blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI), thrombi can form and the device can become occluded. This can lead to serious adverse events, including death.

There have been 5 reports of thrombosis/occlusion with this product, all in patients treated for BTAI. In 1 case, a patient died.

Therefore, Cook Medical Inc. is recalling all lots of the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft that were manufactured from April 10, 2015, to January 3, 2017, and distributed from October 29, 2015, to March 10, 2017.

On March 22, 2017, Cook Medical Inc. sent an “Urgent: Medical Device Correction and Removal” notification to all affected customers.

This recall notification included a description of the problem and reason for the recall, list of affected products, and customer actions to be taken in response to the recall notification.

On June 22, 2017, the company sent an updated notification to all affected customers.

This recall notification informed customers that the instructions for use (IFU) for the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft were updated to remove the indication for BTAI.

Because of the IFU correction to remove BTAI from the indication, it is necessary to remove specific sizes of this device (grafts with a proximal or distal diameter of 18-22 mm) that would likely be used only for BTAI.

About 500 of these devices (18 to 22 mm) will be removed, and roughly 4500 will be relabeled. A Cook Medical sales representative will follow-up with affected customers and provide a corrected IFU.

The company recommends that patients already treated with the Zenith Thoracic Endovascular Graft for the BTAI indication be followed according the current IFU and with considerations outlined in Cook Medical’s March 22, 2017, medical device correction notification.

Customers with questions about this recall may contact Cook Medical Customer Relations at 800-457-4500 or 812-339-2235.

Healthcare professionals and patients are encouraged to report adverse events related to the Zenith Thoracic Endovascular Graft to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced that Cook Medical Inc. is recalling the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft.

The company found that when the device is used for the treatment of blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI), thrombi can form and the device can become occluded. This can lead to serious adverse events, including death.

There have been 5 reports of thrombosis/occlusion with this product, all in patients treated for BTAI. In 1 case, a patient died.

Therefore, Cook Medical Inc. is recalling all lots of the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft that were manufactured from April 10, 2015, to January 3, 2017, and distributed from October 29, 2015, to March 10, 2017.

On March 22, 2017, Cook Medical Inc. sent an “Urgent: Medical Device Correction and Removal” notification to all affected customers.

This recall notification included a description of the problem and reason for the recall, list of affected products, and customer actions to be taken in response to the recall notification.

On June 22, 2017, the company sent an updated notification to all affected customers.

This recall notification informed customers that the instructions for use (IFU) for the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft were updated to remove the indication for BTAI.

Because of the IFU correction to remove BTAI from the indication, it is necessary to remove specific sizes of this device (grafts with a proximal or distal diameter of 18-22 mm) that would likely be used only for BTAI.

About 500 of these devices (18 to 22 mm) will be removed, and roughly 4500 will be relabeled. A Cook Medical sales representative will follow-up with affected customers and provide a corrected IFU.

The company recommends that patients already treated with the Zenith Thoracic Endovascular Graft for the BTAI indication be followed according the current IFU and with considerations outlined in Cook Medical’s March 22, 2017, medical device correction notification.

Customers with questions about this recall may contact Cook Medical Customer Relations at 800-457-4500 or 812-339-2235.

Healthcare professionals and patients are encouraged to report adverse events related to the Zenith Thoracic Endovascular Graft to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced that Cook Medical Inc. is recalling the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft.

The company found that when the device is used for the treatment of blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI), thrombi can form and the device can become occluded. This can lead to serious adverse events, including death.

There have been 5 reports of thrombosis/occlusion with this product, all in patients treated for BTAI. In 1 case, a patient died.

Therefore, Cook Medical Inc. is recalling all lots of the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft that were manufactured from April 10, 2015, to January 3, 2017, and distributed from October 29, 2015, to March 10, 2017.

On March 22, 2017, Cook Medical Inc. sent an “Urgent: Medical Device Correction and Removal” notification to all affected customers.

This recall notification included a description of the problem and reason for the recall, list of affected products, and customer actions to be taken in response to the recall notification.

On June 22, 2017, the company sent an updated notification to all affected customers.

This recall notification informed customers that the instructions for use (IFU) for the Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft were updated to remove the indication for BTAI.

Because of the IFU correction to remove BTAI from the indication, it is necessary to remove specific sizes of this device (grafts with a proximal or distal diameter of 18-22 mm) that would likely be used only for BTAI.

About 500 of these devices (18 to 22 mm) will be removed, and roughly 4500 will be relabeled. A Cook Medical sales representative will follow-up with affected customers and provide a corrected IFU.

The company recommends that patients already treated with the Zenith Thoracic Endovascular Graft for the BTAI indication be followed according the current IFU and with considerations outlined in Cook Medical’s March 22, 2017, medical device correction notification.

Customers with questions about this recall may contact Cook Medical Customer Relations at 800-457-4500 or 812-339-2235.

Healthcare professionals and patients are encouraged to report adverse events related to the Zenith Thoracic Endovascular Graft to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

Rash on abdomen

Based on the negative KOH and the nail pits, the FP made a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis. This condition can present in an annular pattern resembling tinea corporis. The combination of negative KOH and nail pits are enough to diagnose plaque psoriasis without a biopsy. Otherwise, a 4-mm punch biopsy of the area with erythema and scale would confirm the diagnosis.

Plaque psoriasis is typically treated using a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. Although repeated use of steroids in cases of atopic dermatitis can lead to skin atrophy, this is less common when treating psoriasis. If skin atrophy is still a concern, an alternative to topical steroids is a topical vitamin D preparation.

Vitamin D preparations are typically more expensive than steroids and require prior authorization, but there is one generic preparation (calcipotriene) that is more affordable than its brand-name counterparts. Another nonsystemic treatment to consider when treating plaque psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis is narrowband ultraviolet B therapy.

One risk factor for psoriasis is being overweight. In this case, the FP counseled the patient on weight loss. The FP then prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily (especially after bathing).

At a follow-up appointment a month later, there was about 70% clearance of the lesions. For the stubborn areas, the FP prescribed a higher-potency steroid, 0.05% clobetasol ointment, to be applied twice daily. As the cost of clobetasol has risen over the past 2 years, alternatives that may be covered by insurance include augmented betamethasone and halobetasol.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Psoriasis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 878-895.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the negative KOH and the nail pits, the FP made a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis. This condition can present in an annular pattern resembling tinea corporis. The combination of negative KOH and nail pits are enough to diagnose plaque psoriasis without a biopsy. Otherwise, a 4-mm punch biopsy of the area with erythema and scale would confirm the diagnosis.

Plaque psoriasis is typically treated using a mid- to high-potency topical steroid. Although repeated use of steroids in cases of atopic dermatitis can lead to skin atrophy, this is less common when treating psoriasis. If skin atrophy is still a concern, an alternative to topical steroids is a topical vitamin D preparation.