User login

Behavioral Health: Using Rating Scales in a Clinical Setting

In the current health care environment, there is an increasing demand for objective assessment of disease states.1 This is particularly apparent in the realm of behavioral health, where documentation of outcomes lags that of other areas of medicine.

In 2012, the additional health care costs incurred by persons with mental health diagnoses were estimated to be $293 billion among commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare beneficiaries in the United States—a figure that is 273% higher than the cost for those without psychiatric diagnoses.2 Psychiatric and medical illnesses can be so tightly linked that accurate diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders becomes essential to control medical illnesses. It is not surprising that there is increased scrutiny to the ways in which behavioral health care can be objectively assessed and monitored, and payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increasingly require objective documentation of disease state improvement for payment.3

Support for objective assessment of disease derives from the collaborative care model. This model is designed to better integrate mental health and primary care (among other practices) by establishing the Patient-Centered Medical Home and emphasizing screening and monitoring patient-reported outcomes over time to assess treatment response.4 This approach, which is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, is associated with significant improvements in outcomes compared with usual care.5 It tracks patient progress using validated clinical rating scales and other screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] for depression), an approach that is analogous to how patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored by A1C lab tests.6 An extensive body of research supports the impact of this approach on treatment. A 2012 Cochrane review associated collaborative care with significant improvements in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual treatment.7

Despite these findings, a recent Kennedy Forum brief asserts that behavioral health is characterized by a "lack of systematic measurement to determine whether patients are responding to treatment."8 That same brief points to the many validated, easy-to-administer rating scales and screening tools that can reliably measure the frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms over time, and likens the lack of their use to "treating high blood pressure without using a blood pressure cuff to measure if a patient's blood pressure is improving."8 In fact, it is estimated that only 18% of psychiatrists and 11% of psychologists use rating scales routinely.9,10 This lack of use denies clinicians important information that can help detect deterioration or lack of improvement in their patients; implementing these scales in primary care can help early detection of behavioral health problems.

Behavioral health is replete with rating scales and screening tools, and the number of competing scales can make choosing a measure difficult.1 Nonetheless, not all scales are appropriate for clinical use; many are designed for research, for instance, and are lengthy and difficult to administer.

Let's review a number of rating scales that are brief, useful, and easy to administer. A framework for the screening tools addressed in this article is available on the federally funded Center for Integrated Health Solutions website (www.integration.samhsa.gov). This site promotes the use of tools designed to assist in screening and monitoring for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use, and suicidality.11

QUALITY CRITERIA FOR RATING SCALES

The quality of a rating scale is determined by the following attributes.

Objectivity. The ability of a scale to obtain the same results, regardless of who administers, analyzes, or interprets it.

Reliability. The ability of a scale to convey consistent and reproducible information across time, patients, and raters.

Validity. The degree to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (eg, depressive symptoms). Sensitivity and specificity are measures of validity and provide additional information about the rating scale; namely, whether the scale can detect the presence of a disease (sensitivity) and whether it detects only that disease or condition and not another (specificity).

Establishment of norms. Whether a scale provides reference values for different clinical groups.

Practicability. The resources required to administer the assessment instrument in terms of time, staff, and material.12

In addition to meeting these quality criteria, selection of a scale can be based on whether it is self-rated or observer-rated. Advantages to self-rated scales, such as the PHQ-9, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, are their practicability—they are easy to administer and don't require much time—and their use in evaluating and raising awareness of subjective states.

However, reliability may be a concern, as some patients may lack insight or exaggerate or mask symptoms when completing such scales.13 Both observer- and self-rated scales can be used together to minimize bias, identify symptoms that might have been missed/not addressed in the clinical interview, and drive clinical decision-making. Both can also help patients communicate with their providers and make them feel more involved in clinical decision-making.8

ENDORSED RATING SCALES

The following scales have met many of the quality criteria described here and are endorsed by the government payer system. They can easily be incorporated into clinical practice and will provide useful clinical information that can assist in diagnosis and monitoring patient outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire

PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that can help to detect depression and supplement a thorough mental health interview. It scores the nine DSM-IV criteria for depression on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). It is a public resource that is easy to find online, available without cost in several languages, and takes just a few minutes to complete.14

PHQ-9 has shown excellent test-retest reliability in screening for depression, and normative data on the instrument's use are available in various clinical populations.15 Research has shown that as PHQ-9 depression scores increase, functional status decreases, while depressive symptoms, sick days, and health care utilization increase.15 In one study, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 had 88% sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.16 In addition to its use as a screening tool, PHQ-9 is a responsive and reliable measure of depression treatment outcomes.17

Mood Disorder Questionnaire

MDQ is another brief, self-report questionnaire that is available online. It is designed to identify and monitor patients who are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.18,19

The first question on the MDQ asks if the patient has experienced any of 13 common mood and behavior symptoms. The second question asks if these symptoms have ever occurred at the same time, and the third asks the degree to which the patient finds the symptoms to be problematic. The remaining two questions provide additional clinical information, addressing family history of manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder and whether a diagnosis of either disorder has been made.

The MDQ has shown validity in assessing bipolar disorder symptoms in a general population, although recent research suggests that imprecise recall bias may limit its reliability in detecting hypomanic episodes earlier in life.20,21 Nonetheless, its specificity of > 97% means that it will effectively screen out just about all true negatives.18

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

The GAD-7 scale is a brief, self-administered questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of GAD.22 It asks patients to rate seven items that represent problems with general anxiety and scores each item on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Similar to the other measures, it is easily accessible online.

Research evidence supports the reliability and validity of GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population. Sensitivity and specificity are 89% and 82%, respectively. Normative data for age- and sex-specific subgroups support its use across age groups and in both males and females.23 The GAD-7 performs well for detecting and monitoring not only GAD but also panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24

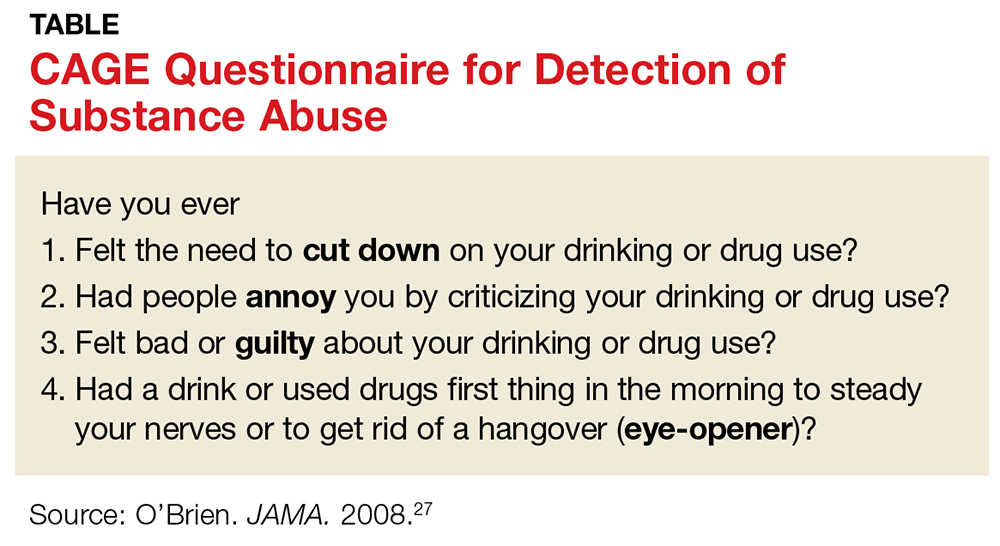

CAGE questionnaire for detection of substance use

The CAGE questionnaire is a widely used screening tool that was originally developed to detect alcohol abuse but has been adapted to assess other substance abuse.25,26 The omission of substance abuse from diagnostic consideration can have a major effect on quality of care, because substance abuse can be the underlying cause of other diseases. Therefore, routine administration of this instrument in clinical practice can lead to better understanding and monitoring of patient health.27

Similar to other instruments, CAGE is free and available online.27 It contains four simple questions, with 1 point assigned to each positive answer (see Table); the simple mnemonic makes the questions easy to remember and to administer in a clinical setting.

CAGE has demonstrated validity, with one study determining that scores ≥ 2 had a specificity and sensitivity of 76% and 93%, respectively, for identifying excessive drinking, and a specificity and sensitivity of 77% and 91%, respectively, for identifying alcohol abuse.28

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS was developed by researchers at Columbia University to assess the severity of and track changes over time in suicidal ideation and behavior. C-SSRS is two pages and takes only a few minutes to administer; however, it also may be completed as a self-report measure. The questions are phrased in an interview format, and while clinicians are encouraged to receive training prior to its administration, specific training in mental health is not required.

The "Lifetime/Recent" version allows practitioners to gather lifetime history of suicidality as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior, whereas the "Since Last Visit" version of the scale assesses suicidality in patients who have completed at least one Lifetime/Recent C-SSRS assessment. A truncated, six-item "Screener" version is typically used in emergency situations. A risk assessment can be added to either the Full or Screener version to summarize the answers from C-SSRS and document risk and protective factors.29

Several studies have found C-SSRS to be reliable and valid for identifying suicide risk in children and adults.30,31USA Today reported that an individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale is eight to 10 times more likely to complete suicide.32 In addition, the C-SSRS has helped reduce the suicide rate by 65% in one of the largest providers of community-based behavioral health care in the United States.32

USING SCALES TO AUGMENT CARE

Each of the scales described in this article can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. The information the scales provide can be used to track progression of symptoms and effectiveness of treatment. Although rating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan, they can and should be used to augment information from the clinician's assessment and follow-up interviews.5

1. McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care with the medical system. http://thekennedyforum-dot-org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/KennedyForum-BehavioralHealth_FINAL_3.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Behavioral health (BH) Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs) Program initiatives. www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/2012-09-27-behavioral-health-clinical-quality-measures-program-initiatives-public-forum.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M. The collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

5. World Group On Psychiatric Evaluation; American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee On Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

6. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman, Inc; 2014.

7. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

8. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for measurement-based care. www.thekennedyforum.org/a-national-call-for-measurement-based-care/. Accessed August 14, 2017.

9. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1916-1919.

10. Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, et al. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists' ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(1):25-32.

11. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions. Screening tools. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools. Accessed August 14, 2017.

12. Moller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26.

13. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

14. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/AssessmentTools/14-PHQ-9%20overview.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

15. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Rehab Measures Web site. www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=954. Accessed August 14, 2017.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

17. Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201.

18. Ketter TA. Strategies for monitoring outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(suppl 1):10-16.

19. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. University of Texas Medical Branch. www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

20. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178-180.

21. Boschloo L, Nolen WA, Spijker AT, et al. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) for detecting (hypo) manic episodes: its validity and impact of recall bias. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):203-208.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

23. Lowe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274.

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325.

25. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907.

26. CAGE substance abuse screening tool. Johns Hopkins Medicine. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns_hopkins_healthcare/downloads/cage%20substance%20screening%20tool.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

27. O'Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2054-2056.

28. Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1(8267):325-328.

29. Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (CS-SRS). http://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.general-use.english. Accessed August 14, 2017.

30. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):887-893.

31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277.

32. Esposito L. Suicide checklist spots people at highest risk. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011-11-09/Suicide-checklist-spots-peo ple-at-highest-risk/51135944/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

In the current health care environment, there is an increasing demand for objective assessment of disease states.1 This is particularly apparent in the realm of behavioral health, where documentation of outcomes lags that of other areas of medicine.

In 2012, the additional health care costs incurred by persons with mental health diagnoses were estimated to be $293 billion among commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare beneficiaries in the United States—a figure that is 273% higher than the cost for those without psychiatric diagnoses.2 Psychiatric and medical illnesses can be so tightly linked that accurate diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders becomes essential to control medical illnesses. It is not surprising that there is increased scrutiny to the ways in which behavioral health care can be objectively assessed and monitored, and payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increasingly require objective documentation of disease state improvement for payment.3

Support for objective assessment of disease derives from the collaborative care model. This model is designed to better integrate mental health and primary care (among other practices) by establishing the Patient-Centered Medical Home and emphasizing screening and monitoring patient-reported outcomes over time to assess treatment response.4 This approach, which is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, is associated with significant improvements in outcomes compared with usual care.5 It tracks patient progress using validated clinical rating scales and other screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] for depression), an approach that is analogous to how patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored by A1C lab tests.6 An extensive body of research supports the impact of this approach on treatment. A 2012 Cochrane review associated collaborative care with significant improvements in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual treatment.7

Despite these findings, a recent Kennedy Forum brief asserts that behavioral health is characterized by a "lack of systematic measurement to determine whether patients are responding to treatment."8 That same brief points to the many validated, easy-to-administer rating scales and screening tools that can reliably measure the frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms over time, and likens the lack of their use to "treating high blood pressure without using a blood pressure cuff to measure if a patient's blood pressure is improving."8 In fact, it is estimated that only 18% of psychiatrists and 11% of psychologists use rating scales routinely.9,10 This lack of use denies clinicians important information that can help detect deterioration or lack of improvement in their patients; implementing these scales in primary care can help early detection of behavioral health problems.

Behavioral health is replete with rating scales and screening tools, and the number of competing scales can make choosing a measure difficult.1 Nonetheless, not all scales are appropriate for clinical use; many are designed for research, for instance, and are lengthy and difficult to administer.

Let's review a number of rating scales that are brief, useful, and easy to administer. A framework for the screening tools addressed in this article is available on the federally funded Center for Integrated Health Solutions website (www.integration.samhsa.gov). This site promotes the use of tools designed to assist in screening and monitoring for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use, and suicidality.11

QUALITY CRITERIA FOR RATING SCALES

The quality of a rating scale is determined by the following attributes.

Objectivity. The ability of a scale to obtain the same results, regardless of who administers, analyzes, or interprets it.

Reliability. The ability of a scale to convey consistent and reproducible information across time, patients, and raters.

Validity. The degree to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (eg, depressive symptoms). Sensitivity and specificity are measures of validity and provide additional information about the rating scale; namely, whether the scale can detect the presence of a disease (sensitivity) and whether it detects only that disease or condition and not another (specificity).

Establishment of norms. Whether a scale provides reference values for different clinical groups.

Practicability. The resources required to administer the assessment instrument in terms of time, staff, and material.12

In addition to meeting these quality criteria, selection of a scale can be based on whether it is self-rated or observer-rated. Advantages to self-rated scales, such as the PHQ-9, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, are their practicability—they are easy to administer and don't require much time—and their use in evaluating and raising awareness of subjective states.

However, reliability may be a concern, as some patients may lack insight or exaggerate or mask symptoms when completing such scales.13 Both observer- and self-rated scales can be used together to minimize bias, identify symptoms that might have been missed/not addressed in the clinical interview, and drive clinical decision-making. Both can also help patients communicate with their providers and make them feel more involved in clinical decision-making.8

ENDORSED RATING SCALES

The following scales have met many of the quality criteria described here and are endorsed by the government payer system. They can easily be incorporated into clinical practice and will provide useful clinical information that can assist in diagnosis and monitoring patient outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire

PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that can help to detect depression and supplement a thorough mental health interview. It scores the nine DSM-IV criteria for depression on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). It is a public resource that is easy to find online, available without cost in several languages, and takes just a few minutes to complete.14

PHQ-9 has shown excellent test-retest reliability in screening for depression, and normative data on the instrument's use are available in various clinical populations.15 Research has shown that as PHQ-9 depression scores increase, functional status decreases, while depressive symptoms, sick days, and health care utilization increase.15 In one study, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 had 88% sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.16 In addition to its use as a screening tool, PHQ-9 is a responsive and reliable measure of depression treatment outcomes.17

Mood Disorder Questionnaire

MDQ is another brief, self-report questionnaire that is available online. It is designed to identify and monitor patients who are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.18,19

The first question on the MDQ asks if the patient has experienced any of 13 common mood and behavior symptoms. The second question asks if these symptoms have ever occurred at the same time, and the third asks the degree to which the patient finds the symptoms to be problematic. The remaining two questions provide additional clinical information, addressing family history of manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder and whether a diagnosis of either disorder has been made.

The MDQ has shown validity in assessing bipolar disorder symptoms in a general population, although recent research suggests that imprecise recall bias may limit its reliability in detecting hypomanic episodes earlier in life.20,21 Nonetheless, its specificity of > 97% means that it will effectively screen out just about all true negatives.18

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

The GAD-7 scale is a brief, self-administered questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of GAD.22 It asks patients to rate seven items that represent problems with general anxiety and scores each item on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Similar to the other measures, it is easily accessible online.

Research evidence supports the reliability and validity of GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population. Sensitivity and specificity are 89% and 82%, respectively. Normative data for age- and sex-specific subgroups support its use across age groups and in both males and females.23 The GAD-7 performs well for detecting and monitoring not only GAD but also panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24

CAGE questionnaire for detection of substance use

The CAGE questionnaire is a widely used screening tool that was originally developed to detect alcohol abuse but has been adapted to assess other substance abuse.25,26 The omission of substance abuse from diagnostic consideration can have a major effect on quality of care, because substance abuse can be the underlying cause of other diseases. Therefore, routine administration of this instrument in clinical practice can lead to better understanding and monitoring of patient health.27

Similar to other instruments, CAGE is free and available online.27 It contains four simple questions, with 1 point assigned to each positive answer (see Table); the simple mnemonic makes the questions easy to remember and to administer in a clinical setting.

CAGE has demonstrated validity, with one study determining that scores ≥ 2 had a specificity and sensitivity of 76% and 93%, respectively, for identifying excessive drinking, and a specificity and sensitivity of 77% and 91%, respectively, for identifying alcohol abuse.28

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS was developed by researchers at Columbia University to assess the severity of and track changes over time in suicidal ideation and behavior. C-SSRS is two pages and takes only a few minutes to administer; however, it also may be completed as a self-report measure. The questions are phrased in an interview format, and while clinicians are encouraged to receive training prior to its administration, specific training in mental health is not required.

The "Lifetime/Recent" version allows practitioners to gather lifetime history of suicidality as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior, whereas the "Since Last Visit" version of the scale assesses suicidality in patients who have completed at least one Lifetime/Recent C-SSRS assessment. A truncated, six-item "Screener" version is typically used in emergency situations. A risk assessment can be added to either the Full or Screener version to summarize the answers from C-SSRS and document risk and protective factors.29

Several studies have found C-SSRS to be reliable and valid for identifying suicide risk in children and adults.30,31USA Today reported that an individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale is eight to 10 times more likely to complete suicide.32 In addition, the C-SSRS has helped reduce the suicide rate by 65% in one of the largest providers of community-based behavioral health care in the United States.32

USING SCALES TO AUGMENT CARE

Each of the scales described in this article can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. The information the scales provide can be used to track progression of symptoms and effectiveness of treatment. Although rating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan, they can and should be used to augment information from the clinician's assessment and follow-up interviews.5

In the current health care environment, there is an increasing demand for objective assessment of disease states.1 This is particularly apparent in the realm of behavioral health, where documentation of outcomes lags that of other areas of medicine.

In 2012, the additional health care costs incurred by persons with mental health diagnoses were estimated to be $293 billion among commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare beneficiaries in the United States—a figure that is 273% higher than the cost for those without psychiatric diagnoses.2 Psychiatric and medical illnesses can be so tightly linked that accurate diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders becomes essential to control medical illnesses. It is not surprising that there is increased scrutiny to the ways in which behavioral health care can be objectively assessed and monitored, and payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increasingly require objective documentation of disease state improvement for payment.3

Support for objective assessment of disease derives from the collaborative care model. This model is designed to better integrate mental health and primary care (among other practices) by establishing the Patient-Centered Medical Home and emphasizing screening and monitoring patient-reported outcomes over time to assess treatment response.4 This approach, which is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, is associated with significant improvements in outcomes compared with usual care.5 It tracks patient progress using validated clinical rating scales and other screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] for depression), an approach that is analogous to how patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored by A1C lab tests.6 An extensive body of research supports the impact of this approach on treatment. A 2012 Cochrane review associated collaborative care with significant improvements in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual treatment.7

Despite these findings, a recent Kennedy Forum brief asserts that behavioral health is characterized by a "lack of systematic measurement to determine whether patients are responding to treatment."8 That same brief points to the many validated, easy-to-administer rating scales and screening tools that can reliably measure the frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms over time, and likens the lack of their use to "treating high blood pressure without using a blood pressure cuff to measure if a patient's blood pressure is improving."8 In fact, it is estimated that only 18% of psychiatrists and 11% of psychologists use rating scales routinely.9,10 This lack of use denies clinicians important information that can help detect deterioration or lack of improvement in their patients; implementing these scales in primary care can help early detection of behavioral health problems.

Behavioral health is replete with rating scales and screening tools, and the number of competing scales can make choosing a measure difficult.1 Nonetheless, not all scales are appropriate for clinical use; many are designed for research, for instance, and are lengthy and difficult to administer.

Let's review a number of rating scales that are brief, useful, and easy to administer. A framework for the screening tools addressed in this article is available on the federally funded Center for Integrated Health Solutions website (www.integration.samhsa.gov). This site promotes the use of tools designed to assist in screening and monitoring for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use, and suicidality.11

QUALITY CRITERIA FOR RATING SCALES

The quality of a rating scale is determined by the following attributes.

Objectivity. The ability of a scale to obtain the same results, regardless of who administers, analyzes, or interprets it.

Reliability. The ability of a scale to convey consistent and reproducible information across time, patients, and raters.

Validity. The degree to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (eg, depressive symptoms). Sensitivity and specificity are measures of validity and provide additional information about the rating scale; namely, whether the scale can detect the presence of a disease (sensitivity) and whether it detects only that disease or condition and not another (specificity).

Establishment of norms. Whether a scale provides reference values for different clinical groups.

Practicability. The resources required to administer the assessment instrument in terms of time, staff, and material.12

In addition to meeting these quality criteria, selection of a scale can be based on whether it is self-rated or observer-rated. Advantages to self-rated scales, such as the PHQ-9, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, are their practicability—they are easy to administer and don't require much time—and their use in evaluating and raising awareness of subjective states.

However, reliability may be a concern, as some patients may lack insight or exaggerate or mask symptoms when completing such scales.13 Both observer- and self-rated scales can be used together to minimize bias, identify symptoms that might have been missed/not addressed in the clinical interview, and drive clinical decision-making. Both can also help patients communicate with their providers and make them feel more involved in clinical decision-making.8

ENDORSED RATING SCALES

The following scales have met many of the quality criteria described here and are endorsed by the government payer system. They can easily be incorporated into clinical practice and will provide useful clinical information that can assist in diagnosis and monitoring patient outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire

PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that can help to detect depression and supplement a thorough mental health interview. It scores the nine DSM-IV criteria for depression on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). It is a public resource that is easy to find online, available without cost in several languages, and takes just a few minutes to complete.14

PHQ-9 has shown excellent test-retest reliability in screening for depression, and normative data on the instrument's use are available in various clinical populations.15 Research has shown that as PHQ-9 depression scores increase, functional status decreases, while depressive symptoms, sick days, and health care utilization increase.15 In one study, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 had 88% sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.16 In addition to its use as a screening tool, PHQ-9 is a responsive and reliable measure of depression treatment outcomes.17

Mood Disorder Questionnaire

MDQ is another brief, self-report questionnaire that is available online. It is designed to identify and monitor patients who are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.18,19

The first question on the MDQ asks if the patient has experienced any of 13 common mood and behavior symptoms. The second question asks if these symptoms have ever occurred at the same time, and the third asks the degree to which the patient finds the symptoms to be problematic. The remaining two questions provide additional clinical information, addressing family history of manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder and whether a diagnosis of either disorder has been made.

The MDQ has shown validity in assessing bipolar disorder symptoms in a general population, although recent research suggests that imprecise recall bias may limit its reliability in detecting hypomanic episodes earlier in life.20,21 Nonetheless, its specificity of > 97% means that it will effectively screen out just about all true negatives.18

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

The GAD-7 scale is a brief, self-administered questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of GAD.22 It asks patients to rate seven items that represent problems with general anxiety and scores each item on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Similar to the other measures, it is easily accessible online.

Research evidence supports the reliability and validity of GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population. Sensitivity and specificity are 89% and 82%, respectively. Normative data for age- and sex-specific subgroups support its use across age groups and in both males and females.23 The GAD-7 performs well for detecting and monitoring not only GAD but also panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24

CAGE questionnaire for detection of substance use

The CAGE questionnaire is a widely used screening tool that was originally developed to detect alcohol abuse but has been adapted to assess other substance abuse.25,26 The omission of substance abuse from diagnostic consideration can have a major effect on quality of care, because substance abuse can be the underlying cause of other diseases. Therefore, routine administration of this instrument in clinical practice can lead to better understanding and monitoring of patient health.27

Similar to other instruments, CAGE is free and available online.27 It contains four simple questions, with 1 point assigned to each positive answer (see Table); the simple mnemonic makes the questions easy to remember and to administer in a clinical setting.

CAGE has demonstrated validity, with one study determining that scores ≥ 2 had a specificity and sensitivity of 76% and 93%, respectively, for identifying excessive drinking, and a specificity and sensitivity of 77% and 91%, respectively, for identifying alcohol abuse.28

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS was developed by researchers at Columbia University to assess the severity of and track changes over time in suicidal ideation and behavior. C-SSRS is two pages and takes only a few minutes to administer; however, it also may be completed as a self-report measure. The questions are phrased in an interview format, and while clinicians are encouraged to receive training prior to its administration, specific training in mental health is not required.

The "Lifetime/Recent" version allows practitioners to gather lifetime history of suicidality as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior, whereas the "Since Last Visit" version of the scale assesses suicidality in patients who have completed at least one Lifetime/Recent C-SSRS assessment. A truncated, six-item "Screener" version is typically used in emergency situations. A risk assessment can be added to either the Full or Screener version to summarize the answers from C-SSRS and document risk and protective factors.29

Several studies have found C-SSRS to be reliable and valid for identifying suicide risk in children and adults.30,31USA Today reported that an individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale is eight to 10 times more likely to complete suicide.32 In addition, the C-SSRS has helped reduce the suicide rate by 65% in one of the largest providers of community-based behavioral health care in the United States.32

USING SCALES TO AUGMENT CARE

Each of the scales described in this article can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. The information the scales provide can be used to track progression of symptoms and effectiveness of treatment. Although rating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan, they can and should be used to augment information from the clinician's assessment and follow-up interviews.5

1. McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care with the medical system. http://thekennedyforum-dot-org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/KennedyForum-BehavioralHealth_FINAL_3.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Behavioral health (BH) Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs) Program initiatives. www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/2012-09-27-behavioral-health-clinical-quality-measures-program-initiatives-public-forum.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M. The collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

5. World Group On Psychiatric Evaluation; American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee On Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

6. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman, Inc; 2014.

7. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

8. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for measurement-based care. www.thekennedyforum.org/a-national-call-for-measurement-based-care/. Accessed August 14, 2017.

9. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1916-1919.

10. Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, et al. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists' ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(1):25-32.

11. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions. Screening tools. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools. Accessed August 14, 2017.

12. Moller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26.

13. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

14. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/AssessmentTools/14-PHQ-9%20overview.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

15. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Rehab Measures Web site. www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=954. Accessed August 14, 2017.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

17. Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201.

18. Ketter TA. Strategies for monitoring outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(suppl 1):10-16.

19. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. University of Texas Medical Branch. www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

20. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178-180.

21. Boschloo L, Nolen WA, Spijker AT, et al. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) for detecting (hypo) manic episodes: its validity and impact of recall bias. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):203-208.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

23. Lowe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274.

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325.

25. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907.

26. CAGE substance abuse screening tool. Johns Hopkins Medicine. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns_hopkins_healthcare/downloads/cage%20substance%20screening%20tool.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

27. O'Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2054-2056.

28. Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1(8267):325-328.

29. Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (CS-SRS). http://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.general-use.english. Accessed August 14, 2017.

30. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):887-893.

31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277.

32. Esposito L. Suicide checklist spots people at highest risk. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011-11-09/Suicide-checklist-spots-peo ple-at-highest-risk/51135944/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

1. McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care with the medical system. http://thekennedyforum-dot-org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/KennedyForum-BehavioralHealth_FINAL_3.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Behavioral health (BH) Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs) Program initiatives. www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/2012-09-27-behavioral-health-clinical-quality-measures-program-initiatives-public-forum.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M. The collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

5. World Group On Psychiatric Evaluation; American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee On Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

6. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman, Inc; 2014.

7. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

8. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for measurement-based care. www.thekennedyforum.org/a-national-call-for-measurement-based-care/. Accessed August 14, 2017.

9. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1916-1919.

10. Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, et al. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists' ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(1):25-32.

11. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions. Screening tools. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools. Accessed August 14, 2017.

12. Moller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26.

13. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

14. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/AssessmentTools/14-PHQ-9%20overview.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

15. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Rehab Measures Web site. www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=954. Accessed August 14, 2017.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

17. Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201.

18. Ketter TA. Strategies for monitoring outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(suppl 1):10-16.

19. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. University of Texas Medical Branch. www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

20. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178-180.

21. Boschloo L, Nolen WA, Spijker AT, et al. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) for detecting (hypo) manic episodes: its validity and impact of recall bias. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):203-208.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

23. Lowe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274.

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325.

25. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907.

26. CAGE substance abuse screening tool. Johns Hopkins Medicine. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns_hopkins_healthcare/downloads/cage%20substance%20screening%20tool.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

27. O'Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2054-2056.

28. Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1(8267):325-328.

29. Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (CS-SRS). http://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.general-use.english. Accessed August 14, 2017.

30. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):887-893.

31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277.

32. Esposito L. Suicide checklist spots people at highest risk. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011-11-09/Suicide-checklist-spots-peo ple-at-highest-risk/51135944/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

Prenatal antidepressant use linked to psychiatric illness in offspring

Antidepressant use before and during pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring, according to the results of a population-based cohort study published Sept. 7 in the BMJ.

There have been contradictory findings in the literature about whether in utero exposure to SSRIs is associated with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. “However, these studies did not investigate the overall risk of psychiatric disorders, which is important because differentiating between overlapping symptoms and diagnosing specific disorders are challenging in children and adolescents,” Xiaoqin Liu, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark, and her coauthors wrote (BMJ 2017;358:j3668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3668).

Participants were categorized into four groups based on maternal use of antidepressants; unexposed, antidepressant discontinuation (if the mother had used in the 2 years before but not during pregnancy), antidepressant continuation (if the use happened in the 2 years before pregnancy and during it), and new users (if antidepressant use happened only during pregnancy).

The study found that children whose mothers used antidepressants both in the 2 years before pregnancy and during pregnancy had a 27% higher incidence of any psychiatric disorder, compared with children whose mothers had used antidepressants but discontinued them before becoming pregnant (95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.38).

This figure was adjusted for factors such as maternal age and psychiatric history at delivery, psychiatric treatment in the 2 years before pregnancy, other psychotropic medications used during pregnancy, and paternal psychiatric history at the time of delivery.

Any maternal antidepressant use was associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the offspring, compared with the unexposed group. The 15-year cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders in offspring was 8% in the unexposed group, 11.5% in the discontinuation group, 13.6% in the continuation group, and 14.5% in the new user group.

There were no differences in risk between children exposed to SSRI monotherapy and those exposed to non-SSRI monotherapy, although the statistical precision for the latter was low, the researchers noted. However, they did see a lower risk of psychiatric disorder in children who were exposed only during the first trimester, compared with those exposed in the second or third trimesters.

The researchers suggested that the association between in utero exposure and the risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring may be the result of a combination of underlying maternal disorders and in utero antidepressant exposure. “We speculated that this increased risk could be due to the severity of underlying maternal psychiatric disorders because mothers with severe symptoms are more likely to continue treatment during pregnancy,” they wrote.

The researchers cautioned that discontinuation of treatment could lead to psychiatric episodes that could have long-lasting effects on both mother and child.

The investigators reported support from several research foundations, as well as institutional grants from Sage Therapeutics and Janssen. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Only the most severely sick women have drugs prescribed during pregnancy. Consequently, confounding by indication is a major challenge in pharmacoepidemiological studies. Including a disease comparison group with women discontinuing antidepressants before pregnancy, as in Liu and her colleagues’ study, offers an important advantage over studies that use only healthy comparison groups because it allows researchers to disentangle the effect of antidepressants from the underlying maternal psychiatric disease.

It is important that researchers report absolute risks to facilitate communication between clinicians and pregnant women. For example, if prenatal exposure to antidepressants is associated with a 23% increased risk of autism in children, and if we assume a baseline prevalence of autism of 1%, then for every 10,000 women who continue treatment during pregnancy, 23 additional cases of autism would occur. This number may be alarming to some patients and reassuring to others.

Hedvig Nordeng, PhD, Angela Lupattelli, PhD, and Mollie Wood, PhD, are from the University of Oslo. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (BMJ 2017;358:j3950 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3950). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Only the most severely sick women have drugs prescribed during pregnancy. Consequently, confounding by indication is a major challenge in pharmacoepidemiological studies. Including a disease comparison group with women discontinuing antidepressants before pregnancy, as in Liu and her colleagues’ study, offers an important advantage over studies that use only healthy comparison groups because it allows researchers to disentangle the effect of antidepressants from the underlying maternal psychiatric disease.

It is important that researchers report absolute risks to facilitate communication between clinicians and pregnant women. For example, if prenatal exposure to antidepressants is associated with a 23% increased risk of autism in children, and if we assume a baseline prevalence of autism of 1%, then for every 10,000 women who continue treatment during pregnancy, 23 additional cases of autism would occur. This number may be alarming to some patients and reassuring to others.

Hedvig Nordeng, PhD, Angela Lupattelli, PhD, and Mollie Wood, PhD, are from the University of Oslo. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (BMJ 2017;358:j3950 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3950). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Only the most severely sick women have drugs prescribed during pregnancy. Consequently, confounding by indication is a major challenge in pharmacoepidemiological studies. Including a disease comparison group with women discontinuing antidepressants before pregnancy, as in Liu and her colleagues’ study, offers an important advantage over studies that use only healthy comparison groups because it allows researchers to disentangle the effect of antidepressants from the underlying maternal psychiatric disease.

It is important that researchers report absolute risks to facilitate communication between clinicians and pregnant women. For example, if prenatal exposure to antidepressants is associated with a 23% increased risk of autism in children, and if we assume a baseline prevalence of autism of 1%, then for every 10,000 women who continue treatment during pregnancy, 23 additional cases of autism would occur. This number may be alarming to some patients and reassuring to others.

Hedvig Nordeng, PhD, Angela Lupattelli, PhD, and Mollie Wood, PhD, are from the University of Oslo. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (BMJ 2017;358:j3950 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3950). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Antidepressant use before and during pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring, according to the results of a population-based cohort study published Sept. 7 in the BMJ.

There have been contradictory findings in the literature about whether in utero exposure to SSRIs is associated with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. “However, these studies did not investigate the overall risk of psychiatric disorders, which is important because differentiating between overlapping symptoms and diagnosing specific disorders are challenging in children and adolescents,” Xiaoqin Liu, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark, and her coauthors wrote (BMJ 2017;358:j3668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3668).

Participants were categorized into four groups based on maternal use of antidepressants; unexposed, antidepressant discontinuation (if the mother had used in the 2 years before but not during pregnancy), antidepressant continuation (if the use happened in the 2 years before pregnancy and during it), and new users (if antidepressant use happened only during pregnancy).

The study found that children whose mothers used antidepressants both in the 2 years before pregnancy and during pregnancy had a 27% higher incidence of any psychiatric disorder, compared with children whose mothers had used antidepressants but discontinued them before becoming pregnant (95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.38).

This figure was adjusted for factors such as maternal age and psychiatric history at delivery, psychiatric treatment in the 2 years before pregnancy, other psychotropic medications used during pregnancy, and paternal psychiatric history at the time of delivery.

Any maternal antidepressant use was associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the offspring, compared with the unexposed group. The 15-year cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders in offspring was 8% in the unexposed group, 11.5% in the discontinuation group, 13.6% in the continuation group, and 14.5% in the new user group.

There were no differences in risk between children exposed to SSRI monotherapy and those exposed to non-SSRI monotherapy, although the statistical precision for the latter was low, the researchers noted. However, they did see a lower risk of psychiatric disorder in children who were exposed only during the first trimester, compared with those exposed in the second or third trimesters.

The researchers suggested that the association between in utero exposure and the risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring may be the result of a combination of underlying maternal disorders and in utero antidepressant exposure. “We speculated that this increased risk could be due to the severity of underlying maternal psychiatric disorders because mothers with severe symptoms are more likely to continue treatment during pregnancy,” they wrote.

The researchers cautioned that discontinuation of treatment could lead to psychiatric episodes that could have long-lasting effects on both mother and child.

The investigators reported support from several research foundations, as well as institutional grants from Sage Therapeutics and Janssen. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Antidepressant use before and during pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring, according to the results of a population-based cohort study published Sept. 7 in the BMJ.

There have been contradictory findings in the literature about whether in utero exposure to SSRIs is associated with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. “However, these studies did not investigate the overall risk of psychiatric disorders, which is important because differentiating between overlapping symptoms and diagnosing specific disorders are challenging in children and adolescents,” Xiaoqin Liu, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark, and her coauthors wrote (BMJ 2017;358:j3668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3668).

Participants were categorized into four groups based on maternal use of antidepressants; unexposed, antidepressant discontinuation (if the mother had used in the 2 years before but not during pregnancy), antidepressant continuation (if the use happened in the 2 years before pregnancy and during it), and new users (if antidepressant use happened only during pregnancy).

The study found that children whose mothers used antidepressants both in the 2 years before pregnancy and during pregnancy had a 27% higher incidence of any psychiatric disorder, compared with children whose mothers had used antidepressants but discontinued them before becoming pregnant (95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.38).

This figure was adjusted for factors such as maternal age and psychiatric history at delivery, psychiatric treatment in the 2 years before pregnancy, other psychotropic medications used during pregnancy, and paternal psychiatric history at the time of delivery.

Any maternal antidepressant use was associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the offspring, compared with the unexposed group. The 15-year cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders in offspring was 8% in the unexposed group, 11.5% in the discontinuation group, 13.6% in the continuation group, and 14.5% in the new user group.

There were no differences in risk between children exposed to SSRI monotherapy and those exposed to non-SSRI monotherapy, although the statistical precision for the latter was low, the researchers noted. However, they did see a lower risk of psychiatric disorder in children who were exposed only during the first trimester, compared with those exposed in the second or third trimesters.

The researchers suggested that the association between in utero exposure and the risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring may be the result of a combination of underlying maternal disorders and in utero antidepressant exposure. “We speculated that this increased risk could be due to the severity of underlying maternal psychiatric disorders because mothers with severe symptoms are more likely to continue treatment during pregnancy,” they wrote.

The researchers cautioned that discontinuation of treatment could lead to psychiatric episodes that could have long-lasting effects on both mother and child.

The investigators reported support from several research foundations, as well as institutional grants from Sage Therapeutics and Janssen. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM THE BMJ

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Children whose mothers took antidepressants both before and during pregnancy are 27% more likely to develop psychiatric illness than are those whose mothers stopped taking antidepressants before pregnancy.

Data source: A population-based cohort study in 905,383 liveborn singletons.

Disclosures: The investigators reported support from several research foundations, as well as institutional grants from Sage Therapeutics and Janssen. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Does microneedling have a role in aesthetics?

AT MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – When Jill S. Waibel, MD, first saw a dermal roller microneedling device around 2004, it reminded her of a weapon that might be conjured up by the character Dr. Kaufman, a professional assassin who appeared in the 1997 James Bond film, “Tomorrow Never Dies.”

“I’m thinking, that thing looks super painful,” Dr. Waibel said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Patients seek microneedling treatments to rejuvenate skin; to treat acne scarring, other scars, striae, and rhytides; and to improve pigmentation. Its mechanism of action remains elusive. The hypothesis for microneedling’s effects on superficial rhytides, the wound that it creates induces production of new collagen and that multiple tiny wounds in the skin stimulate the release of various growth factors that play a role in collagen synthesis. When used on atrophic scars, the hypothesis is that microneedling breaks apart collagen bundles in the superficial layer of the dermis while inducing production of collagen. Authors of a recent systematic review on the topic found that the procedure showed noteworthy results on its own, particularly when combined with radio-frequency features (J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017 Jun 17. pii: S1748-6815[17]30250-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.06.006).

“However, there were shortcomings with most of the research: There were small numbers of patients, studies that were not randomized, not controlled, and further research is needed to see if microneedling truly works,” said Dr. Waibel, who was not involved with the analysis.

Microneedling devices come in many forms, including manual rollers, fixed-needle rollers, electric-powered pens, and devices with a new light-emitting microneedling technology. Of the five devices currently cleared by the Food and Drug Administration, four feature bipolar radio frequency and insulated needles, while one is a bipolar radio-frequency device (Infini) that contains noninsulated needles. Dr. Waibel favors the electric-powered pens, such as the StrataPen and the Eclipse MicroPen, that enable the user to adjust operating speed and penetration depths from 0.5 mm-3.0 mm, as well as feature disposable needle tips and disposable needles. These devices allow the depth of penetration to be changed according to what part of the face is being treated: “So on thinner areas of the face, like the forehead and the nose, you’re going to treat with a depth of 0.5 mm-1.0 mm, whereas in thicker areas, like the cheeks, you go up to 3.0 mm,” she said. “Typically, we do vertical and horizontal passes, repeating three to six times. When you see pinpoint bleeding, that’s the sign to stop. You can stop prior to that as well.”

One split-face study compared microneedling with nonablative fractional laser in 30 patients with atrophic scars, who underwent five sessions 1 month apart. (Dermatol Surg 2017; 43:S47-56). At 3 months, the side of the face treated with the laser showed a 70% improvement, compared with 30% for the side treated with microneedling (P less than .001). The researchers observed significantly lower pain scores with the laser procedure, but microneedling had a significantly shorter down time. A separate study of 12 healthy adults found that pretreatment with an ablative fractional laser significantly intensifies protoporphyrin IX fluorescence to a larger extent than curettage, microdermabrasion, microneedling, and nonablative fractional laser (JAMA Derm. 2017;153[4]:270-8). “So the message is that lasers are still superior, but there may be a role for microneedling,” Dr. Waibel said.

Since she began dabbling with microneedling in her practice over the past year, Dr. Waibel has found it is a good option for younger patients and for patients who desire little to no recovery time. “These are not expensive procedures for someone who doesn’t have a lot of skin damage,” she said. “It’s also good for difficult indications to improve, like striae. If I charge patients a few hundred dollars for a laser treatment, maybe I can do two or three follow-ups with the microneedle to stimulate collagen. This has become one of my go-tos with the radio-frequency device. I’ll do one fractional ablative laser treatment, then I’ll do two of the radiofrequency microneedle devices 1 and 2 months later. Then I’ll reassess to see what they need next. Or you might tweak [the course of treatment] after isolated laser treatments.”

Using a microneedle device requires meticulous cleaning of the intended treatment area prior to the procedure to avoid introducing bacteria or makeup into the skin. Dr. Waibel uses topical anesthesia for 20-30 minutes and then applies hyaluronic acid gel on the treatment surface to facilitate the gliding action of the device. “The technique involves perpendicular device placement with manual skin traction for smooth delivery of microneedles, going in vertical, horizontal, and oblique motions,” she explained. “Pinpoint bleeding is your guide for the pens. You don’t get pinpoint bleeding with some of the actual devices. Use manual pressure with ice and water to stop the bleeding.”

Contraindications for microneedling include patients with an active infection (such as herpes labialis), acne, and a predisposition for keloid scarring. Caution is advised with concomitant use of topical products of any type during a microneedling procedure because of the risk of granuloma formation. In 2014, researchers published a case series of three patients who developed biopsy-proven foreign body granulomas after the application of topical products during microneedling, including two cases that involved topical vitamin C (JAMA Dermatol 2014;150[1]:68-72).

“These are new devices, and we have new questions,” Dr. Waibel concluded. “I think they have a role, but we don’t fully understand the mechanism of action, and we have to be very careful about putting pharmacology down these channels. We don’t know the best treatment intervals, and we don’t know the best devices,” she added, pointing out that many of the devices have no indications cleared by the FDA yet.

She also noted that the FDA has put a hold on many microneedling devices from being sold in the United States until appropriate safety and efficacy data are collected.

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she has conducted clinical research for Strata Sciences, Aquavit, and Lutronic. She is also a member of the advisory board for Lutronic.

AT MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – When Jill S. Waibel, MD, first saw a dermal roller microneedling device around 2004, it reminded her of a weapon that might be conjured up by the character Dr. Kaufman, a professional assassin who appeared in the 1997 James Bond film, “Tomorrow Never Dies.”

“I’m thinking, that thing looks super painful,” Dr. Waibel said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Patients seek microneedling treatments to rejuvenate skin; to treat acne scarring, other scars, striae, and rhytides; and to improve pigmentation. Its mechanism of action remains elusive. The hypothesis for microneedling’s effects on superficial rhytides, the wound that it creates induces production of new collagen and that multiple tiny wounds in the skin stimulate the release of various growth factors that play a role in collagen synthesis. When used on atrophic scars, the hypothesis is that microneedling breaks apart collagen bundles in the superficial layer of the dermis while inducing production of collagen. Authors of a recent systematic review on the topic found that the procedure showed noteworthy results on its own, particularly when combined with radio-frequency features (J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017 Jun 17. pii: S1748-6815[17]30250-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.06.006).

“However, there were shortcomings with most of the research: There were small numbers of patients, studies that were not randomized, not controlled, and further research is needed to see if microneedling truly works,” said Dr. Waibel, who was not involved with the analysis.

Microneedling devices come in many forms, including manual rollers, fixed-needle rollers, electric-powered pens, and devices with a new light-emitting microneedling technology. Of the five devices currently cleared by the Food and Drug Administration, four feature bipolar radio frequency and insulated needles, while one is a bipolar radio-frequency device (Infini) that contains noninsulated needles. Dr. Waibel favors the electric-powered pens, such as the StrataPen and the Eclipse MicroPen, that enable the user to adjust operating speed and penetration depths from 0.5 mm-3.0 mm, as well as feature disposable needle tips and disposable needles. These devices allow the depth of penetration to be changed according to what part of the face is being treated: “So on thinner areas of the face, like the forehead and the nose, you’re going to treat with a depth of 0.5 mm-1.0 mm, whereas in thicker areas, like the cheeks, you go up to 3.0 mm,” she said. “Typically, we do vertical and horizontal passes, repeating three to six times. When you see pinpoint bleeding, that’s the sign to stop. You can stop prior to that as well.”

One split-face study compared microneedling with nonablative fractional laser in 30 patients with atrophic scars, who underwent five sessions 1 month apart. (Dermatol Surg 2017; 43:S47-56). At 3 months, the side of the face treated with the laser showed a 70% improvement, compared with 30% for the side treated with microneedling (P less than .001). The researchers observed significantly lower pain scores with the laser procedure, but microneedling had a significantly shorter down time. A separate study of 12 healthy adults found that pretreatment with an ablative fractional laser significantly intensifies protoporphyrin IX fluorescence to a larger extent than curettage, microdermabrasion, microneedling, and nonablative fractional laser (JAMA Derm. 2017;153[4]:270-8). “So the message is that lasers are still superior, but there may be a role for microneedling,” Dr. Waibel said.

Since she began dabbling with microneedling in her practice over the past year, Dr. Waibel has found it is a good option for younger patients and for patients who desire little to no recovery time. “These are not expensive procedures for someone who doesn’t have a lot of skin damage,” she said. “It’s also good for difficult indications to improve, like striae. If I charge patients a few hundred dollars for a laser treatment, maybe I can do two or three follow-ups with the microneedle to stimulate collagen. This has become one of my go-tos with the radio-frequency device. I’ll do one fractional ablative laser treatment, then I’ll do two of the radiofrequency microneedle devices 1 and 2 months later. Then I’ll reassess to see what they need next. Or you might tweak [the course of treatment] after isolated laser treatments.”