User login

DDSEP® 8 Quick quiz - September 2017 Question 2

Answer B

Objective: Recognize the clinical presentation and imaging features of main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

Critique: The patient’s imaging is consistent with main duct IPMN and the mild pancreatitis is likely a consequence of mucin plugging and obstruction. Main duct IPMN is associated with a higher incidence of malignancy, compared with branch duct IPMN and surgical resection is recommended if the patient is a surgical candidate.

While further sampling with endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography may be helpful, these tests have a low sensitivity for identifying dysplasia and are unlikely to change management. Surveillance with MRI would be appropriate if the patient does not wish to undergo surgery at this time.

Answer B

Objective: Recognize the clinical presentation and imaging features of main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

Critique: The patient’s imaging is consistent with main duct IPMN and the mild pancreatitis is likely a consequence of mucin plugging and obstruction. Main duct IPMN is associated with a higher incidence of malignancy, compared with branch duct IPMN and surgical resection is recommended if the patient is a surgical candidate.

While further sampling with endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography may be helpful, these tests have a low sensitivity for identifying dysplasia and are unlikely to change management. Surveillance with MRI would be appropriate if the patient does not wish to undergo surgery at this time.

Answer B

Objective: Recognize the clinical presentation and imaging features of main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

Critique: The patient’s imaging is consistent with main duct IPMN and the mild pancreatitis is likely a consequence of mucin plugging and obstruction. Main duct IPMN is associated with a higher incidence of malignancy, compared with branch duct IPMN and surgical resection is recommended if the patient is a surgical candidate.

While further sampling with endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography may be helpful, these tests have a low sensitivity for identifying dysplasia and are unlikely to change management. Surveillance with MRI would be appropriate if the patient does not wish to undergo surgery at this time.

A 72-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with mild acute pancreatitis. He reports vague abdominal pain for the past 3 months. He is otherwise healthy and has well-controlled hypertension. He is active and exercises three times a week. CT scan reveals a markedly dilated main pancreatic duct with no stricture as shown below in representative axial and coronal images (Figures 1, 2).

DDSEP® 8 Quick quiz - September 2017 Question 1

Answer D

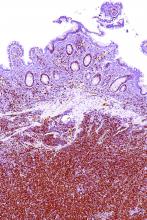

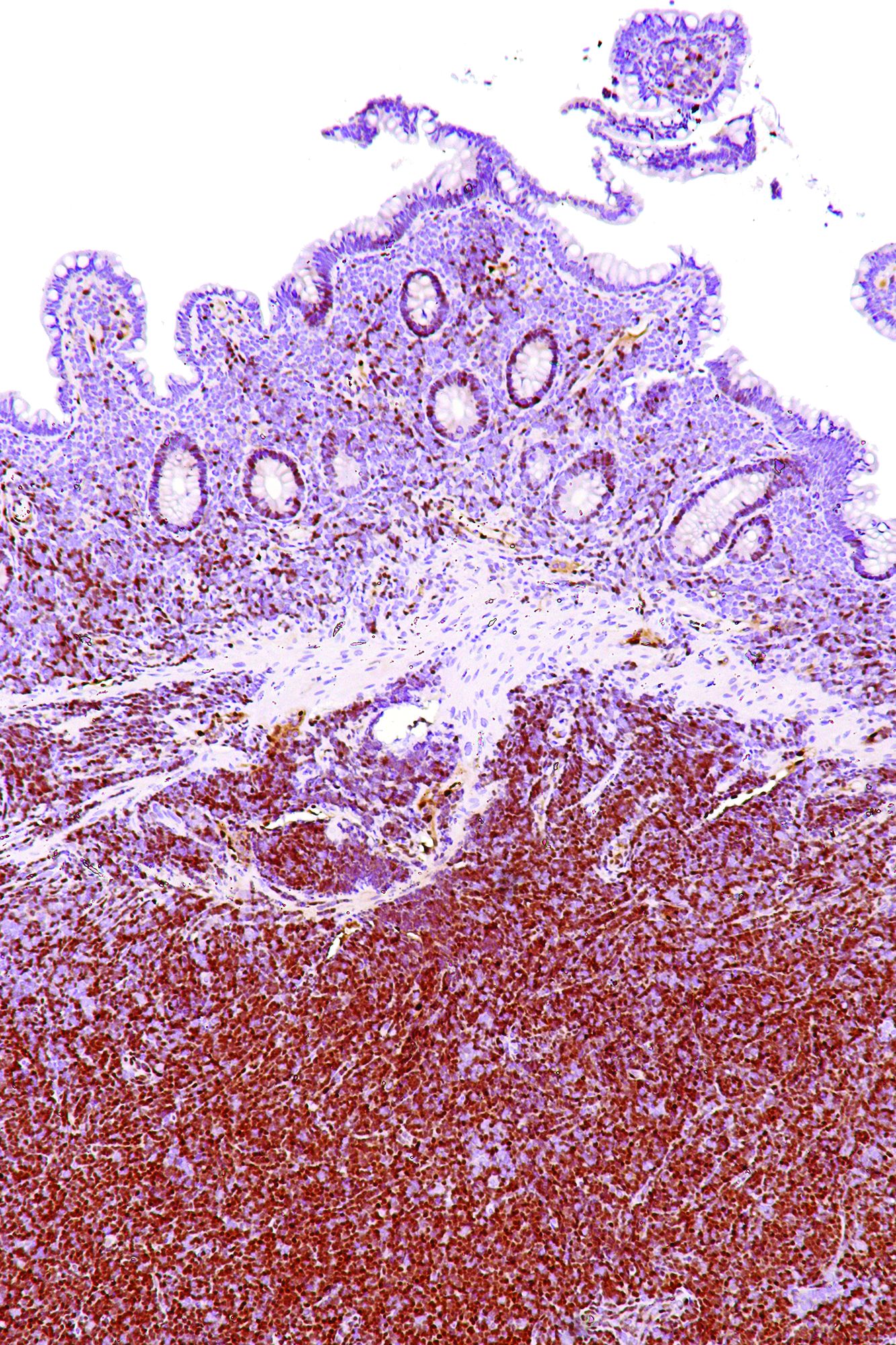

Objective: Identify the clinical presentation and risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Rationale: This patient likely has small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) based on her symptoms, the steatorrhea with the positive Sudan stain for fat, and a slight anemia with an elevated MCV suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency secondary to the bacterial overgrowth. She also has scleroderma, a condition commonly associated with SIBO, because it impairs gastrointestinal motility.

While hydrogen breath testing may help establish the diagnosis of SIBO, there is variable sensitivity and specificity of the testing with false-positive and false-negative test results frequently occurring. An alternative strategy is to treat empirically with an accepted antibiotic regimen and assess response after the course is completed.

References

1. Bures J., Cyrany J., Kohoutova D., et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun 28;16(24):2978-90.

2. Abu-Shanab A., Quigley E.M.. Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: The challenges persist! Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Feb;3(1):77-87.

3. Khoshini R., Dai S.C., Lezcano S., Pimentel M. A systematic review of diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Jun;53(6):1443-54.

Answer D

Objective: Identify the clinical presentation and risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Rationale: This patient likely has small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) based on her symptoms, the steatorrhea with the positive Sudan stain for fat, and a slight anemia with an elevated MCV suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency secondary to the bacterial overgrowth. She also has scleroderma, a condition commonly associated with SIBO, because it impairs gastrointestinal motility.

While hydrogen breath testing may help establish the diagnosis of SIBO, there is variable sensitivity and specificity of the testing with false-positive and false-negative test results frequently occurring. An alternative strategy is to treat empirically with an accepted antibiotic regimen and assess response after the course is completed.

References

1. Bures J., Cyrany J., Kohoutova D., et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun 28;16(24):2978-90.

2. Abu-Shanab A., Quigley E.M.. Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: The challenges persist! Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Feb;3(1):77-87.

3. Khoshini R., Dai S.C., Lezcano S., Pimentel M. A systematic review of diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Jun;53(6):1443-54.

Answer D

Objective: Identify the clinical presentation and risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Rationale: This patient likely has small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) based on her symptoms, the steatorrhea with the positive Sudan stain for fat, and a slight anemia with an elevated MCV suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency secondary to the bacterial overgrowth. She also has scleroderma, a condition commonly associated with SIBO, because it impairs gastrointestinal motility.

While hydrogen breath testing may help establish the diagnosis of SIBO, there is variable sensitivity and specificity of the testing with false-positive and false-negative test results frequently occurring. An alternative strategy is to treat empirically with an accepted antibiotic regimen and assess response after the course is completed.

References

1. Bures J., Cyrany J., Kohoutova D., et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jun 28;16(24):2978-90.

2. Abu-Shanab A., Quigley E.M.. Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: The challenges persist! Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Feb;3(1):77-87.

3. Khoshini R., Dai S.C., Lezcano S., Pimentel M. A systematic review of diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Jun;53(6):1443-54.

A 56-year-old woman with a history of scleroderma presents for evaluation of recurrent episodes of bloating, excess flatulence, mild nausea, and watery diarrhea for the past 5 months without associated weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, or fevers.

She had a normal screening colonoscopy 2 years ago, and an upper endoscopy for evaluation of reflux and dyspepsia 5 years ago, which was only notable for a small sliding hiatal hernia. Laboratory testing reveals hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL with an MCV 106 fL. Stool studies are negative for occult blood, fecal calprotectin is not elevated, but a Sudan stain is positive.

Worsening osteoporosis care for RA patients shows need for action

Osteoporosis care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is suboptimal, and the relative risk of the application of appropriate osteoporosis care in both RA and osteoarthritis patients has been declining steadily over the past decade, according to findings from a large, prospective, observational study.

The study included 11,669 RA patients and 2,829 OA patients in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases who were followed from 2003 through 2014 and showed that about half of the RA patients in whom osteoporosis treatment was indicated never received an osteoporosis medication. Further, the decline in the application of appropriate osteoporosis care was apparent even after the release of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis, according to the findings, which have been accepted for publication in Arthritis Care & Research (doi: 10.1002/acr.23331).

A more recent study in the general population showed that, regardless of glucocorticoid (GC) use, there was a significant decrease in the use of oral bisphosphonates from 1996 to 2012, noted Dr. Ozen of the University of Nebraska, Omaha, and Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey.

“The evidence from all these studies suggests that, despite a slight improvement in GIOP care, with a decline in overall OP care in the early 2000s, the OP care gap has always been suboptimal and declined over the last decade significantly,” she said, adding that this is “especially more worrisome in glucocorticoid-receiving RA patients,” in whom bone loss and fracture risk are dramatically increased.

“Additionally, considering that rheumatologists do better regarding comorbidity follow-up and management than other specialists who follow patients with rheumatic diseases, the gap for osteoporosis care might be even higher than we reported,” she said.

Indeed, among physicians caring for patients with osteoporosis, there is concern that “we’re on the precipice of further increase in fracture burden,” according to Kenneth Saag, MD, a rheumatologist and professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The conclusions of the study by Dr. Ozen and her colleagues are disturbing, but “not tremendously surprising,” said Dr. Saag, who also is president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

The findings are consistent with those from previous studies, he explained.

For example, Daniel H. Solomon, MD, and his associates showed that only 23% of 623 RA patients, including 236 patients who were taking glucocorticoids at an index visit in 1999, underwent bone densitometry, and only 42% were prescribed a medication (other than calcium and/or vitamin D), that reduces bone loss (Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3136-42). They also showed that, in 2004, despite a slight improvement vs. prior years, only 48% of 193 RA patients included in a chart review had received a bone mineral density test or medication for osteoporosis, and 64% of those taking more than 5 mg of prednisone for more than 3 months were receiving osteoporosis management (Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:873-7).

In the current study, Dr. Ozen and her colleagues looked at both RA and OA patients and found that overall, osteoporosis treatment or screening was reported in 67.4% of study subjects over a mean of 5.5 years follow-up. Of those eligible for osteoporosis treatment based on the 2010 ACR guidelines, including 48.4% of RA patients and 17.6% of OA patients, 55% reported osteoporosis medication use. Despite their increased risk of osteoporosis, particularly in the setting of glucocorticoid use, RA patients were not more likely than OA patients to undergo screening or receive treatment (hazard ratio, 1.04).

“This suboptimal and decreasing trend for osteoporosis treatment and screening in RA patients is important as the prevalence of osteoporosis leading to fractures in RA, regardless of GC use, is still high, despite aggressive management strategies and the use of [biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic agents],” they wrote.

Factors contributing to the decline

The reasons for the decline after 2008 are not fully known, but data suggest that both patient and clinician factors play a role.

Lack of knowledge, unwillingness to take additional drugs, and cost are among patient factors that may interfere with screening and treatment, and lack of experience and time, and a focus more on disease activity and other comorbid conditions may be among clinician factors, they said.

Other factors that may have affected patient and clinician willingness to pursue care include 2007 cuts in Medicare reimbursement for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), a 2006 warning regarding jaw osteonecrosis with bisphosphonate use, and 2007 and 2010 publications about atrial fibrillation and atypical femoral fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate treatment, they noted.

Dr. Saag agreed that it is difficult to pinpoint exact reasons for the decline, but said the DXA reimbursement cuts have had a significant effect.

“Declining reimbursement is likely one of the major factors, if not the major factor in the decline in testing that has been observed nationally,” he said, explaining that reimbursement was below the break-even point for many physicians in freestanding medical practices, and that slight adjustments have applied only to facilities located in hospitals. As a result, the availability of DXA screening has declined.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation and other organizations such as the International Society for Clinical Densitometry are lobbying for changes, as there is a very strong link between testing and treatment.

“If we can’t get more people tested, we’re unlikely to get more people treated,” Dr. Saag said.

The availability of new agents for the treatment of osteoporosis could also lead to improvements in screening and care, he added.

In July, Amgen submitted to the Food and Drug Administration a supplemental new Biologics License Application for Prolia (denosumab) for the treatment of patients with GIOP. The application is based on a phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of Prolia, compared with risedronate, in patients receiving glucocorticoid treatment. Denosumab was also shown in a phase 3 study presented at the 2016 ACR meeting to result in greater improvement in bone mineral density vs. bisphosphonates across multiple sites, said Dr. Saag, an investigator for the trial.

“So we’re pleased about that finding, and we’re hopeful that eventually denosumab may become another treatment option,” he said, adding that having more choices leads to more personalized care for patients.

“We hope that, if it does receive approval and is utilized, that it may partially help address the gap in treatment that has been identified,” he said, adding that abaloparatide (Tymlos), which is approved for use in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and high fracture risk, and romosozumab, currently in late-phase development, could also eventually help bridge the gap.

Recent guideline update

There is also optimism that a recent update to the 2010 guideline, published in August in Arthritis Care & Research, will help address the problem (Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69:1095-1110).

“We hope that one the most important impacts of the new 2017 ACR GIOP guideline will be increasing the awareness of GIOP care,” Dr. Ozen said, noting that changes in the new guideline will also be helpful for guiding management of certain patients not addressed in the 2010 guideline, including adults under age 40 years and children.

The new guideline also incorporates FRAX hip fracture scores into the risk-assessment recommendations .

“Lastly, the addition of other oral bisphosphonates and denosumab to the guideline has broadened the potential therapeutic options for physicians and patients,” she said.

Efforts by the ACR to make these guidelines widely known among clinicians could also help promote improved screening and treatment, said Dr. Buckley, a professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

And that awareness is what is needed most, Dr. Ozen said.

“What we need in osteoporosis care of RA or GIOP patients is more awareness and education about risk-benefit ratios of antiosteoporotic medications instead of focusing on the medication type. We hope that our paper showing the worsening osteoporosis care and the new 2017 ACR GIOP guideline provide more awareness and guidance for the physicians managing these patients,” she said, adding that overcoming obstacles in osteoporosis care requires identification and attention to all potential causes for the suboptimal management of osteoporosis from both patients’ and physicians’ perspectives.

“With the improvement in management strategies of rheumatic diseases ... we anticipate improvement in life expectancy and cardiovascular outcomes in RA and inflammatory rheumatic diseases. In this regard, with aging and decreased but ongoing clinical or subclinical chronic inflammation, it is highly likely that we might be dealing with much older patients with higher osteoporosis and fracture risks. Considering the significant contribution of fractures on cost, disability, morbidity, and mortality of these diseases, rheumatologists and other specialists should work together more vigilantly to overcome the obstacles and improve osteoporosis care,” she said.

Dr. Ozen and Dr. Buckley reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Saag is an investigator and consultant for Amgen, Merck, and Radius Health, and is a consultant for Lilly.

Osteoporosis care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is suboptimal, and the relative risk of the application of appropriate osteoporosis care in both RA and osteoarthritis patients has been declining steadily over the past decade, according to findings from a large, prospective, observational study.

The study included 11,669 RA patients and 2,829 OA patients in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases who were followed from 2003 through 2014 and showed that about half of the RA patients in whom osteoporosis treatment was indicated never received an osteoporosis medication. Further, the decline in the application of appropriate osteoporosis care was apparent even after the release of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis, according to the findings, which have been accepted for publication in Arthritis Care & Research (doi: 10.1002/acr.23331).

A more recent study in the general population showed that, regardless of glucocorticoid (GC) use, there was a significant decrease in the use of oral bisphosphonates from 1996 to 2012, noted Dr. Ozen of the University of Nebraska, Omaha, and Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey.

“The evidence from all these studies suggests that, despite a slight improvement in GIOP care, with a decline in overall OP care in the early 2000s, the OP care gap has always been suboptimal and declined over the last decade significantly,” she said, adding that this is “especially more worrisome in glucocorticoid-receiving RA patients,” in whom bone loss and fracture risk are dramatically increased.

“Additionally, considering that rheumatologists do better regarding comorbidity follow-up and management than other specialists who follow patients with rheumatic diseases, the gap for osteoporosis care might be even higher than we reported,” she said.

Indeed, among physicians caring for patients with osteoporosis, there is concern that “we’re on the precipice of further increase in fracture burden,” according to Kenneth Saag, MD, a rheumatologist and professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The conclusions of the study by Dr. Ozen and her colleagues are disturbing, but “not tremendously surprising,” said Dr. Saag, who also is president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

The findings are consistent with those from previous studies, he explained.

For example, Daniel H. Solomon, MD, and his associates showed that only 23% of 623 RA patients, including 236 patients who were taking glucocorticoids at an index visit in 1999, underwent bone densitometry, and only 42% were prescribed a medication (other than calcium and/or vitamin D), that reduces bone loss (Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3136-42). They also showed that, in 2004, despite a slight improvement vs. prior years, only 48% of 193 RA patients included in a chart review had received a bone mineral density test or medication for osteoporosis, and 64% of those taking more than 5 mg of prednisone for more than 3 months were receiving osteoporosis management (Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:873-7).

In the current study, Dr. Ozen and her colleagues looked at both RA and OA patients and found that overall, osteoporosis treatment or screening was reported in 67.4% of study subjects over a mean of 5.5 years follow-up. Of those eligible for osteoporosis treatment based on the 2010 ACR guidelines, including 48.4% of RA patients and 17.6% of OA patients, 55% reported osteoporosis medication use. Despite their increased risk of osteoporosis, particularly in the setting of glucocorticoid use, RA patients were not more likely than OA patients to undergo screening or receive treatment (hazard ratio, 1.04).

“This suboptimal and decreasing trend for osteoporosis treatment and screening in RA patients is important as the prevalence of osteoporosis leading to fractures in RA, regardless of GC use, is still high, despite aggressive management strategies and the use of [biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic agents],” they wrote.

Factors contributing to the decline

The reasons for the decline after 2008 are not fully known, but data suggest that both patient and clinician factors play a role.

Lack of knowledge, unwillingness to take additional drugs, and cost are among patient factors that may interfere with screening and treatment, and lack of experience and time, and a focus more on disease activity and other comorbid conditions may be among clinician factors, they said.

Other factors that may have affected patient and clinician willingness to pursue care include 2007 cuts in Medicare reimbursement for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), a 2006 warning regarding jaw osteonecrosis with bisphosphonate use, and 2007 and 2010 publications about atrial fibrillation and atypical femoral fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate treatment, they noted.

Dr. Saag agreed that it is difficult to pinpoint exact reasons for the decline, but said the DXA reimbursement cuts have had a significant effect.

“Declining reimbursement is likely one of the major factors, if not the major factor in the decline in testing that has been observed nationally,” he said, explaining that reimbursement was below the break-even point for many physicians in freestanding medical practices, and that slight adjustments have applied only to facilities located in hospitals. As a result, the availability of DXA screening has declined.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation and other organizations such as the International Society for Clinical Densitometry are lobbying for changes, as there is a very strong link between testing and treatment.

“If we can’t get more people tested, we’re unlikely to get more people treated,” Dr. Saag said.

The availability of new agents for the treatment of osteoporosis could also lead to improvements in screening and care, he added.

In July, Amgen submitted to the Food and Drug Administration a supplemental new Biologics License Application for Prolia (denosumab) for the treatment of patients with GIOP. The application is based on a phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of Prolia, compared with risedronate, in patients receiving glucocorticoid treatment. Denosumab was also shown in a phase 3 study presented at the 2016 ACR meeting to result in greater improvement in bone mineral density vs. bisphosphonates across multiple sites, said Dr. Saag, an investigator for the trial.

“So we’re pleased about that finding, and we’re hopeful that eventually denosumab may become another treatment option,” he said, adding that having more choices leads to more personalized care for patients.

“We hope that, if it does receive approval and is utilized, that it may partially help address the gap in treatment that has been identified,” he said, adding that abaloparatide (Tymlos), which is approved for use in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and high fracture risk, and romosozumab, currently in late-phase development, could also eventually help bridge the gap.

Recent guideline update

There is also optimism that a recent update to the 2010 guideline, published in August in Arthritis Care & Research, will help address the problem (Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69:1095-1110).

“We hope that one the most important impacts of the new 2017 ACR GIOP guideline will be increasing the awareness of GIOP care,” Dr. Ozen said, noting that changes in the new guideline will also be helpful for guiding management of certain patients not addressed in the 2010 guideline, including adults under age 40 years and children.

The new guideline also incorporates FRAX hip fracture scores into the risk-assessment recommendations .

“Lastly, the addition of other oral bisphosphonates and denosumab to the guideline has broadened the potential therapeutic options for physicians and patients,” she said.

Efforts by the ACR to make these guidelines widely known among clinicians could also help promote improved screening and treatment, said Dr. Buckley, a professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

And that awareness is what is needed most, Dr. Ozen said.

“What we need in osteoporosis care of RA or GIOP patients is more awareness and education about risk-benefit ratios of antiosteoporotic medications instead of focusing on the medication type. We hope that our paper showing the worsening osteoporosis care and the new 2017 ACR GIOP guideline provide more awareness and guidance for the physicians managing these patients,” she said, adding that overcoming obstacles in osteoporosis care requires identification and attention to all potential causes for the suboptimal management of osteoporosis from both patients’ and physicians’ perspectives.

“With the improvement in management strategies of rheumatic diseases ... we anticipate improvement in life expectancy and cardiovascular outcomes in RA and inflammatory rheumatic diseases. In this regard, with aging and decreased but ongoing clinical or subclinical chronic inflammation, it is highly likely that we might be dealing with much older patients with higher osteoporosis and fracture risks. Considering the significant contribution of fractures on cost, disability, morbidity, and mortality of these diseases, rheumatologists and other specialists should work together more vigilantly to overcome the obstacles and improve osteoporosis care,” she said.

Dr. Ozen and Dr. Buckley reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Saag is an investigator and consultant for Amgen, Merck, and Radius Health, and is a consultant for Lilly.

Osteoporosis care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is suboptimal, and the relative risk of the application of appropriate osteoporosis care in both RA and osteoarthritis patients has been declining steadily over the past decade, according to findings from a large, prospective, observational study.

The study included 11,669 RA patients and 2,829 OA patients in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases who were followed from 2003 through 2014 and showed that about half of the RA patients in whom osteoporosis treatment was indicated never received an osteoporosis medication. Further, the decline in the application of appropriate osteoporosis care was apparent even after the release of the 2010 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis, according to the findings, which have been accepted for publication in Arthritis Care & Research (doi: 10.1002/acr.23331).

A more recent study in the general population showed that, regardless of glucocorticoid (GC) use, there was a significant decrease in the use of oral bisphosphonates from 1996 to 2012, noted Dr. Ozen of the University of Nebraska, Omaha, and Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey.

“The evidence from all these studies suggests that, despite a slight improvement in GIOP care, with a decline in overall OP care in the early 2000s, the OP care gap has always been suboptimal and declined over the last decade significantly,” she said, adding that this is “especially more worrisome in glucocorticoid-receiving RA patients,” in whom bone loss and fracture risk are dramatically increased.

“Additionally, considering that rheumatologists do better regarding comorbidity follow-up and management than other specialists who follow patients with rheumatic diseases, the gap for osteoporosis care might be even higher than we reported,” she said.

Indeed, among physicians caring for patients with osteoporosis, there is concern that “we’re on the precipice of further increase in fracture burden,” according to Kenneth Saag, MD, a rheumatologist and professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The conclusions of the study by Dr. Ozen and her colleagues are disturbing, but “not tremendously surprising,” said Dr. Saag, who also is president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

The findings are consistent with those from previous studies, he explained.

For example, Daniel H. Solomon, MD, and his associates showed that only 23% of 623 RA patients, including 236 patients who were taking glucocorticoids at an index visit in 1999, underwent bone densitometry, and only 42% were prescribed a medication (other than calcium and/or vitamin D), that reduces bone loss (Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3136-42). They also showed that, in 2004, despite a slight improvement vs. prior years, only 48% of 193 RA patients included in a chart review had received a bone mineral density test or medication for osteoporosis, and 64% of those taking more than 5 mg of prednisone for more than 3 months were receiving osteoporosis management (Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:873-7).

In the current study, Dr. Ozen and her colleagues looked at both RA and OA patients and found that overall, osteoporosis treatment or screening was reported in 67.4% of study subjects over a mean of 5.5 years follow-up. Of those eligible for osteoporosis treatment based on the 2010 ACR guidelines, including 48.4% of RA patients and 17.6% of OA patients, 55% reported osteoporosis medication use. Despite their increased risk of osteoporosis, particularly in the setting of glucocorticoid use, RA patients were not more likely than OA patients to undergo screening or receive treatment (hazard ratio, 1.04).

“This suboptimal and decreasing trend for osteoporosis treatment and screening in RA patients is important as the prevalence of osteoporosis leading to fractures in RA, regardless of GC use, is still high, despite aggressive management strategies and the use of [biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic agents],” they wrote.

Factors contributing to the decline

The reasons for the decline after 2008 are not fully known, but data suggest that both patient and clinician factors play a role.

Lack of knowledge, unwillingness to take additional drugs, and cost are among patient factors that may interfere with screening and treatment, and lack of experience and time, and a focus more on disease activity and other comorbid conditions may be among clinician factors, they said.

Other factors that may have affected patient and clinician willingness to pursue care include 2007 cuts in Medicare reimbursement for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), a 2006 warning regarding jaw osteonecrosis with bisphosphonate use, and 2007 and 2010 publications about atrial fibrillation and atypical femoral fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate treatment, they noted.

Dr. Saag agreed that it is difficult to pinpoint exact reasons for the decline, but said the DXA reimbursement cuts have had a significant effect.

“Declining reimbursement is likely one of the major factors, if not the major factor in the decline in testing that has been observed nationally,” he said, explaining that reimbursement was below the break-even point for many physicians in freestanding medical practices, and that slight adjustments have applied only to facilities located in hospitals. As a result, the availability of DXA screening has declined.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation and other organizations such as the International Society for Clinical Densitometry are lobbying for changes, as there is a very strong link between testing and treatment.

“If we can’t get more people tested, we’re unlikely to get more people treated,” Dr. Saag said.

The availability of new agents for the treatment of osteoporosis could also lead to improvements in screening and care, he added.

In July, Amgen submitted to the Food and Drug Administration a supplemental new Biologics License Application for Prolia (denosumab) for the treatment of patients with GIOP. The application is based on a phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of Prolia, compared with risedronate, in patients receiving glucocorticoid treatment. Denosumab was also shown in a phase 3 study presented at the 2016 ACR meeting to result in greater improvement in bone mineral density vs. bisphosphonates across multiple sites, said Dr. Saag, an investigator for the trial.

“So we’re pleased about that finding, and we’re hopeful that eventually denosumab may become another treatment option,” he said, adding that having more choices leads to more personalized care for patients.

“We hope that, if it does receive approval and is utilized, that it may partially help address the gap in treatment that has been identified,” he said, adding that abaloparatide (Tymlos), which is approved for use in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and high fracture risk, and romosozumab, currently in late-phase development, could also eventually help bridge the gap.

Recent guideline update

There is also optimism that a recent update to the 2010 guideline, published in August in Arthritis Care & Research, will help address the problem (Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69:1095-1110).

“We hope that one the most important impacts of the new 2017 ACR GIOP guideline will be increasing the awareness of GIOP care,” Dr. Ozen said, noting that changes in the new guideline will also be helpful for guiding management of certain patients not addressed in the 2010 guideline, including adults under age 40 years and children.

The new guideline also incorporates FRAX hip fracture scores into the risk-assessment recommendations .

“Lastly, the addition of other oral bisphosphonates and denosumab to the guideline has broadened the potential therapeutic options for physicians and patients,” she said.

Efforts by the ACR to make these guidelines widely known among clinicians could also help promote improved screening and treatment, said Dr. Buckley, a professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

And that awareness is what is needed most, Dr. Ozen said.

“What we need in osteoporosis care of RA or GIOP patients is more awareness and education about risk-benefit ratios of antiosteoporotic medications instead of focusing on the medication type. We hope that our paper showing the worsening osteoporosis care and the new 2017 ACR GIOP guideline provide more awareness and guidance for the physicians managing these patients,” she said, adding that overcoming obstacles in osteoporosis care requires identification and attention to all potential causes for the suboptimal management of osteoporosis from both patients’ and physicians’ perspectives.

“With the improvement in management strategies of rheumatic diseases ... we anticipate improvement in life expectancy and cardiovascular outcomes in RA and inflammatory rheumatic diseases. In this regard, with aging and decreased but ongoing clinical or subclinical chronic inflammation, it is highly likely that we might be dealing with much older patients with higher osteoporosis and fracture risks. Considering the significant contribution of fractures on cost, disability, morbidity, and mortality of these diseases, rheumatologists and other specialists should work together more vigilantly to overcome the obstacles and improve osteoporosis care,” she said.

Dr. Ozen and Dr. Buckley reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Saag is an investigator and consultant for Amgen, Merck, and Radius Health, and is a consultant for Lilly.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Study: Many cancer patients don’t understand clinical trials

MADRID—Results of a nationwide study suggest many cancer patients in Ireland don’t understand key aspects of clinical trial methodology.

Most of the patients surveyed, which included individuals who had participated in a clinical trial, did not understand the concepts of randomization or equipoise.

“Over half of previous medical trial participants and 73% of those who had never been on a cancer clinical trial did not understand that, in a randomized trial, the treatment given was decided by chance,” said study investigator Catherine Kelly, MB BCh, of Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin, Ireland.

“We also found that most patients did not understand clinical equipoise—the fact that no one knows which treatment is best. Surprisingly, this was more marked in previous clinical trial participants, 60% of whom believed that their doctor would know which study arm was best.”

Dr Kelly and her colleagues presented these findings at the ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 1465P_PR).

The researchers surveyed 1090 adult cancer patients treated at 1 of 14 participating oncology centers across Ireland.

The patients’ median age was 60 (range, 50-69), 64.4% were female, and 66% were diagnosed between 2014 and 2016. The most common cancer types were breast (31.4%), colorectal (15.6%), hematologic (12.6%), genitourinary (11.6%), and lung (6.8%).

The patients filled out anonymized questionnaires in which they were asked to evaluate statements about clinical trials. The patients had to determine whether a statement is true or false, or they could indicate that they didn’t know an answer.

A majority of the patients (82.3%) said they understood what a medical or cancer clinical trial is. And 27.8% of patients said they had previously participated in a cancer trial.

However, many patients didn’t know when clinical trials may be an option. Twenty-two percent of patients said it is true that “clinical trials are only used when standard treatments have not worked,” and 26.6% said they didn’t know if this statement is true or false.

Roughly a third (33.5%) of patients said it is true that, in a randomized trial, treatment is decided by chance, but 41.4% of patients said this is false, and 25% said they didn’t know.

More than half of patients (56.5%) said their doctor would know which treatment was superior in a clinical trial, and 23.2% of patients said they didn’t know if their doctor would know.

About 61% of all patients said their doctor would make sure they received the superior treatment in a clinical trial. An even greater percentage—63.6%—of patients who had previously participated in a clinical trial said the same.

“To provide informed consent when participating in a trial, patients need to understand these key concepts, and doctors explaining them well is essential to alleviating any fears that might prevent patients from participating,” Dr Kelly said.

“Doctors have a responsibility to properly inform their patients in this regard because they are the ones patients trust the most. As we analyze the data further, we will be able to offer physicians a more detailed picture of the questions patients need answered and the factors that influence their decision-making according to age group, cancer type, educational background, and other demographics.”

Funding for this research was provided to Cancer Trials Ireland by Amgen, Abbvie, Bayor, and Inveva. ![]()

MADRID—Results of a nationwide study suggest many cancer patients in Ireland don’t understand key aspects of clinical trial methodology.

Most of the patients surveyed, which included individuals who had participated in a clinical trial, did not understand the concepts of randomization or equipoise.

“Over half of previous medical trial participants and 73% of those who had never been on a cancer clinical trial did not understand that, in a randomized trial, the treatment given was decided by chance,” said study investigator Catherine Kelly, MB BCh, of Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin, Ireland.

“We also found that most patients did not understand clinical equipoise—the fact that no one knows which treatment is best. Surprisingly, this was more marked in previous clinical trial participants, 60% of whom believed that their doctor would know which study arm was best.”

Dr Kelly and her colleagues presented these findings at the ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 1465P_PR).

The researchers surveyed 1090 adult cancer patients treated at 1 of 14 participating oncology centers across Ireland.

The patients’ median age was 60 (range, 50-69), 64.4% were female, and 66% were diagnosed between 2014 and 2016. The most common cancer types were breast (31.4%), colorectal (15.6%), hematologic (12.6%), genitourinary (11.6%), and lung (6.8%).

The patients filled out anonymized questionnaires in which they were asked to evaluate statements about clinical trials. The patients had to determine whether a statement is true or false, or they could indicate that they didn’t know an answer.

A majority of the patients (82.3%) said they understood what a medical or cancer clinical trial is. And 27.8% of patients said they had previously participated in a cancer trial.

However, many patients didn’t know when clinical trials may be an option. Twenty-two percent of patients said it is true that “clinical trials are only used when standard treatments have not worked,” and 26.6% said they didn’t know if this statement is true or false.

Roughly a third (33.5%) of patients said it is true that, in a randomized trial, treatment is decided by chance, but 41.4% of patients said this is false, and 25% said they didn’t know.

More than half of patients (56.5%) said their doctor would know which treatment was superior in a clinical trial, and 23.2% of patients said they didn’t know if their doctor would know.

About 61% of all patients said their doctor would make sure they received the superior treatment in a clinical trial. An even greater percentage—63.6%—of patients who had previously participated in a clinical trial said the same.

“To provide informed consent when participating in a trial, patients need to understand these key concepts, and doctors explaining them well is essential to alleviating any fears that might prevent patients from participating,” Dr Kelly said.

“Doctors have a responsibility to properly inform their patients in this regard because they are the ones patients trust the most. As we analyze the data further, we will be able to offer physicians a more detailed picture of the questions patients need answered and the factors that influence their decision-making according to age group, cancer type, educational background, and other demographics.”

Funding for this research was provided to Cancer Trials Ireland by Amgen, Abbvie, Bayor, and Inveva. ![]()

MADRID—Results of a nationwide study suggest many cancer patients in Ireland don’t understand key aspects of clinical trial methodology.

Most of the patients surveyed, which included individuals who had participated in a clinical trial, did not understand the concepts of randomization or equipoise.

“Over half of previous medical trial participants and 73% of those who had never been on a cancer clinical trial did not understand that, in a randomized trial, the treatment given was decided by chance,” said study investigator Catherine Kelly, MB BCh, of Mater Misericordiae University Hospital in Dublin, Ireland.

“We also found that most patients did not understand clinical equipoise—the fact that no one knows which treatment is best. Surprisingly, this was more marked in previous clinical trial participants, 60% of whom believed that their doctor would know which study arm was best.”

Dr Kelly and her colleagues presented these findings at the ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 1465P_PR).

The researchers surveyed 1090 adult cancer patients treated at 1 of 14 participating oncology centers across Ireland.

The patients’ median age was 60 (range, 50-69), 64.4% were female, and 66% were diagnosed between 2014 and 2016. The most common cancer types were breast (31.4%), colorectal (15.6%), hematologic (12.6%), genitourinary (11.6%), and lung (6.8%).

The patients filled out anonymized questionnaires in which they were asked to evaluate statements about clinical trials. The patients had to determine whether a statement is true or false, or they could indicate that they didn’t know an answer.

A majority of the patients (82.3%) said they understood what a medical or cancer clinical trial is. And 27.8% of patients said they had previously participated in a cancer trial.

However, many patients didn’t know when clinical trials may be an option. Twenty-two percent of patients said it is true that “clinical trials are only used when standard treatments have not worked,” and 26.6% said they didn’t know if this statement is true or false.

Roughly a third (33.5%) of patients said it is true that, in a randomized trial, treatment is decided by chance, but 41.4% of patients said this is false, and 25% said they didn’t know.

More than half of patients (56.5%) said their doctor would know which treatment was superior in a clinical trial, and 23.2% of patients said they didn’t know if their doctor would know.

About 61% of all patients said their doctor would make sure they received the superior treatment in a clinical trial. An even greater percentage—63.6%—of patients who had previously participated in a clinical trial said the same.

“To provide informed consent when participating in a trial, patients need to understand these key concepts, and doctors explaining them well is essential to alleviating any fears that might prevent patients from participating,” Dr Kelly said.

“Doctors have a responsibility to properly inform their patients in this regard because they are the ones patients trust the most. As we analyze the data further, we will be able to offer physicians a more detailed picture of the questions patients need answered and the factors that influence their decision-making according to age group, cancer type, educational background, and other demographics.”

Funding for this research was provided to Cancer Trials Ireland by Amgen, Abbvie, Bayor, and Inveva. ![]()

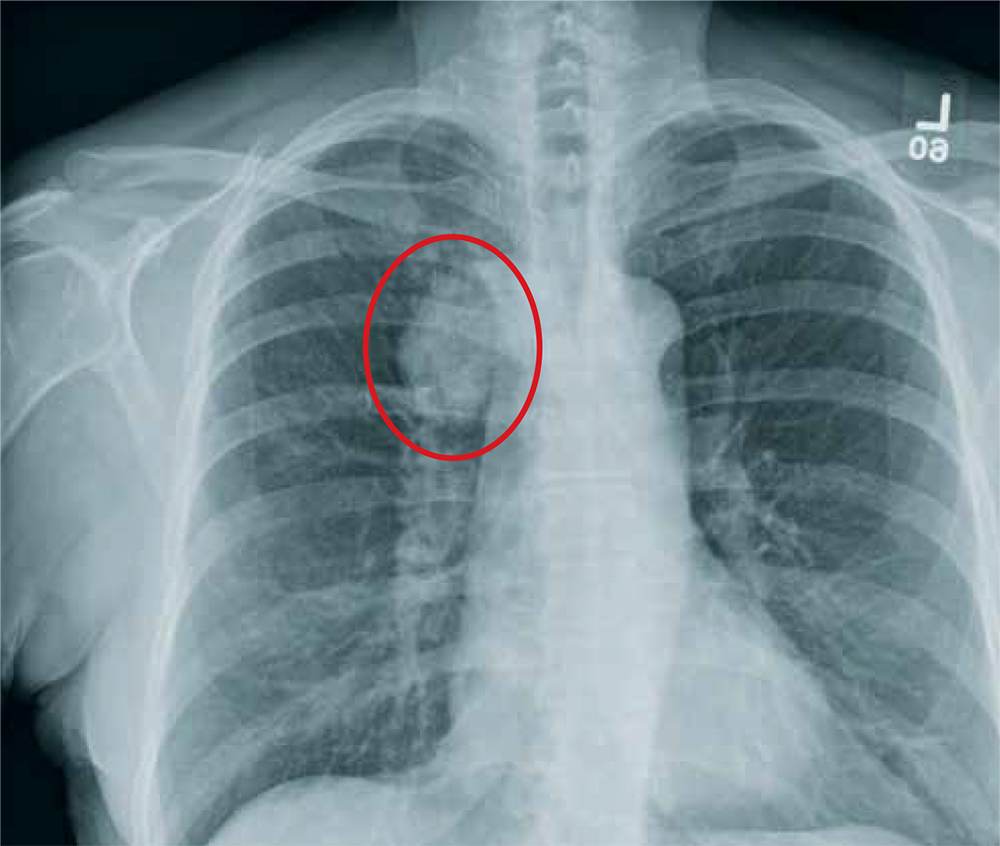

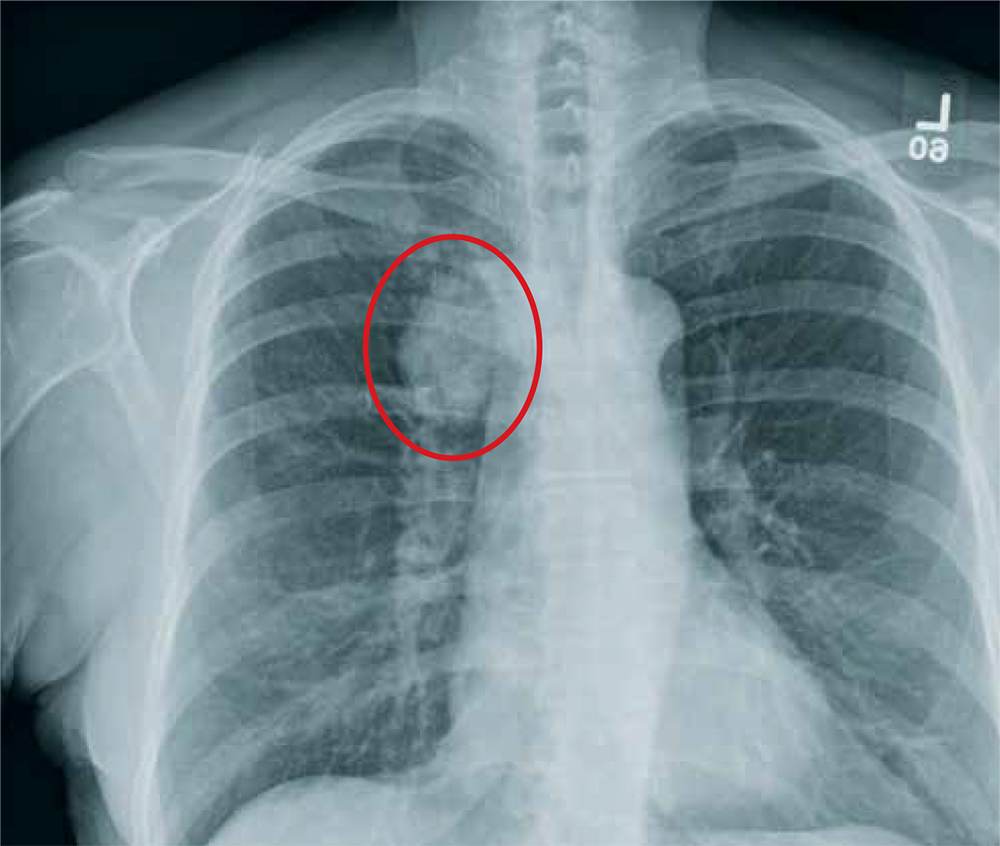

The Not-So-Routine Physical

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a moderate-size mass, measuring about 5 × 3 cm, at the medial portion of the right upper lobe, within the paratracheal region. This lesion should be treated as a neoplasm until proven otherwise. Contrast-enhanced CT is warranted, as well as prompt referral to a cardiothoracic surgeon.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a moderate-size mass, measuring about 5 × 3 cm, at the medial portion of the right upper lobe, within the paratracheal region. This lesion should be treated as a neoplasm until proven otherwise. Contrast-enhanced CT is warranted, as well as prompt referral to a cardiothoracic surgeon.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a moderate-size mass, measuring about 5 × 3 cm, at the medial portion of the right upper lobe, within the paratracheal region. This lesion should be treated as a neoplasm until proven otherwise. Contrast-enhanced CT is warranted, as well as prompt referral to a cardiothoracic surgeon.

A 60-year-old woman wants to establish care as a new patient at your clinic. She presents for an annual physical and has no current complaints.

Her medical history is significant for hypertension and remote uterine cancer, which was treated with a hysterectomy. She does report smoking a half-pack to one pack of cigarettes per day for “about 30 to 40” years.

Vital signs are normal. Overall, the complete physical examination yields no abnormal findings. Routine bloodwork, 12-lead ECG, and a chest radiograph are ordered. The last is shown. What is your impression?

Radiofrequency devices appear to reduce vaginal laxity

SAN DIEGO – The first randomized, sham-controlled study of a radiofrequency energy-based device for vaginal laxity showed a significant and sustained effect, and likely raises the bar on vaginal rejuvenation options, Suzanne L. Kilmer, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“There are a lot of women who have vaginal laxity, vaginal atrophy, and other issues, and this is something that seems to help,” she said. No devices have yet received female rejuvenation/vaginal function indications from the Food and Drug Administration.

Current in-office procedures involve the delivery of radiofrequency (RF) energy, which appears to stimulate collagen production, and the use of fractionated lasers to target the epithelium. “RF devices tend to be easier to use,” said Dr. Kilmer, director of the Laser and Skin Surgery of Northern California, Sacramento. “They’re smaller devices, do not require as much laser training, and they tend to be less expensive. There’s no plume or odor with any of the RF devices.”

She discussed the results of the Viveve Treatment of the Vaginal Introitus to Evaluate Effectiveness (Viveve I) study, conducted at nine sites in four countries, which examined the Viveve monopolar RF device in 155 premenopausal women. The study subjects were randomized to one of two groups: the treatment group received 90 J/cm2 for five passes and the sham group received 1 J/cm2 for five passes (J Sex Med 2017;14[2]:215-25).

The researchers used the Vaginal Laxity Questionnaire (VSQ), which grades vaginal tone on a 7-point scale that ranges from very loose (0) to very tight (7), and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to collect patient-reported outcomes at one, three, and six months. Subjects had to have a VSQ score of 3 or less to participate in the study.

At 6 months, patients in the treatment group were more than 3 times as likely to have no vaginal laxity, compared with their counterparts in the sham group (P less than or equal to 0.006). In addition, more than half of patients in the treatment group moved at least 2 points on the VSQ scale toward a “tighter” vagina.

“Even a one-point increase in tightness will be significant for women,” said Dr. Kilmer, who has used the Viveve device in her practice but was not part of this study.

Based on responses to the FSFI questionnaire, the researchers observed a significant and sustained improvement in sexual function after a single treatment among patients in the treatment group, compared with those in the sham group. The placebo effect didn’t rise above “dysfunctional” at six months, and rate of treatment emergent adverse events was similar between the treatment and sham groups (11.1% vs. 12.3%, respectively), she said.

The researchers also reported the following patient tolerability variables: warmth during the procedure (96% in the treatment group vs. 19% in the sham group, respectively); cool sensation during the procedure (42% vs. 75%), and stopped procedure due to discomfort (1% in each group).

Dr. Kilmer explained that RF heating of the skin and mucosa provides immediate contraction of collagen, long-term stimulation of new collagen production, as well as increased blood flow and restoration of nerve signaling, which results in normal vaginal lubrication. “The critical RF temperature is in the 35 to 47 degree range,” she said. “Very few people can tolerate above 42 degrees.”

Similarly, good results were noted in a pilot study of the ThermiVa radiofrequency product manufactured by ThermoGen in 23 patients who underwent three treatments one month apart (Int J Laser Aesthet Med. July 2015:16-21). All patients experienced significant change with about a 50% reduction in symptoms.

“Patients are very happy with this treatment,” said Dr. Kilmer, who is also a professor of dermatology at the University of California, Davis Medical Center. “It may not be the absolute home run, but I think it’s very safe ... Most people say it lasts about six months then they’ll start to see some of their symptoms coming back.”

Dr. Kilmer reported that she is a member of the medical advisory board for Allergan, Cytrellis, Lumenis, Merz, Miramar, Sienna Labs, Syneron/Candela, Zarin, Zeltiq, and Zift. She has also received research support from those companies as well as from Cutera, Cynosure, Lutronic, R2 Derm, Solta/Valeant, and Ulthera.

SAN DIEGO – The first randomized, sham-controlled study of a radiofrequency energy-based device for vaginal laxity showed a significant and sustained effect, and likely raises the bar on vaginal rejuvenation options, Suzanne L. Kilmer, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“There are a lot of women who have vaginal laxity, vaginal atrophy, and other issues, and this is something that seems to help,” she said. No devices have yet received female rejuvenation/vaginal function indications from the Food and Drug Administration.

Current in-office procedures involve the delivery of radiofrequency (RF) energy, which appears to stimulate collagen production, and the use of fractionated lasers to target the epithelium. “RF devices tend to be easier to use,” said Dr. Kilmer, director of the Laser and Skin Surgery of Northern California, Sacramento. “They’re smaller devices, do not require as much laser training, and they tend to be less expensive. There’s no plume or odor with any of the RF devices.”

She discussed the results of the Viveve Treatment of the Vaginal Introitus to Evaluate Effectiveness (Viveve I) study, conducted at nine sites in four countries, which examined the Viveve monopolar RF device in 155 premenopausal women. The study subjects were randomized to one of two groups: the treatment group received 90 J/cm2 for five passes and the sham group received 1 J/cm2 for five passes (J Sex Med 2017;14[2]:215-25).

The researchers used the Vaginal Laxity Questionnaire (VSQ), which grades vaginal tone on a 7-point scale that ranges from very loose (0) to very tight (7), and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to collect patient-reported outcomes at one, three, and six months. Subjects had to have a VSQ score of 3 or less to participate in the study.

At 6 months, patients in the treatment group were more than 3 times as likely to have no vaginal laxity, compared with their counterparts in the sham group (P less than or equal to 0.006). In addition, more than half of patients in the treatment group moved at least 2 points on the VSQ scale toward a “tighter” vagina.

“Even a one-point increase in tightness will be significant for women,” said Dr. Kilmer, who has used the Viveve device in her practice but was not part of this study.

Based on responses to the FSFI questionnaire, the researchers observed a significant and sustained improvement in sexual function after a single treatment among patients in the treatment group, compared with those in the sham group. The placebo effect didn’t rise above “dysfunctional” at six months, and rate of treatment emergent adverse events was similar between the treatment and sham groups (11.1% vs. 12.3%, respectively), she said.

The researchers also reported the following patient tolerability variables: warmth during the procedure (96% in the treatment group vs. 19% in the sham group, respectively); cool sensation during the procedure (42% vs. 75%), and stopped procedure due to discomfort (1% in each group).

Dr. Kilmer explained that RF heating of the skin and mucosa provides immediate contraction of collagen, long-term stimulation of new collagen production, as well as increased blood flow and restoration of nerve signaling, which results in normal vaginal lubrication. “The critical RF temperature is in the 35 to 47 degree range,” she said. “Very few people can tolerate above 42 degrees.”

Similarly, good results were noted in a pilot study of the ThermiVa radiofrequency product manufactured by ThermoGen in 23 patients who underwent three treatments one month apart (Int J Laser Aesthet Med. July 2015:16-21). All patients experienced significant change with about a 50% reduction in symptoms.

“Patients are very happy with this treatment,” said Dr. Kilmer, who is also a professor of dermatology at the University of California, Davis Medical Center. “It may not be the absolute home run, but I think it’s very safe ... Most people say it lasts about six months then they’ll start to see some of their symptoms coming back.”

Dr. Kilmer reported that she is a member of the medical advisory board for Allergan, Cytrellis, Lumenis, Merz, Miramar, Sienna Labs, Syneron/Candela, Zarin, Zeltiq, and Zift. She has also received research support from those companies as well as from Cutera, Cynosure, Lutronic, R2 Derm, Solta/Valeant, and Ulthera.

SAN DIEGO – The first randomized, sham-controlled study of a radiofrequency energy-based device for vaginal laxity showed a significant and sustained effect, and likely raises the bar on vaginal rejuvenation options, Suzanne L. Kilmer, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

“There are a lot of women who have vaginal laxity, vaginal atrophy, and other issues, and this is something that seems to help,” she said. No devices have yet received female rejuvenation/vaginal function indications from the Food and Drug Administration.

Current in-office procedures involve the delivery of radiofrequency (RF) energy, which appears to stimulate collagen production, and the use of fractionated lasers to target the epithelium. “RF devices tend to be easier to use,” said Dr. Kilmer, director of the Laser and Skin Surgery of Northern California, Sacramento. “They’re smaller devices, do not require as much laser training, and they tend to be less expensive. There’s no plume or odor with any of the RF devices.”

She discussed the results of the Viveve Treatment of the Vaginal Introitus to Evaluate Effectiveness (Viveve I) study, conducted at nine sites in four countries, which examined the Viveve monopolar RF device in 155 premenopausal women. The study subjects were randomized to one of two groups: the treatment group received 90 J/cm2 for five passes and the sham group received 1 J/cm2 for five passes (J Sex Med 2017;14[2]:215-25).

The researchers used the Vaginal Laxity Questionnaire (VSQ), which grades vaginal tone on a 7-point scale that ranges from very loose (0) to very tight (7), and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) to collect patient-reported outcomes at one, three, and six months. Subjects had to have a VSQ score of 3 or less to participate in the study.

At 6 months, patients in the treatment group were more than 3 times as likely to have no vaginal laxity, compared with their counterparts in the sham group (P less than or equal to 0.006). In addition, more than half of patients in the treatment group moved at least 2 points on the VSQ scale toward a “tighter” vagina.

“Even a one-point increase in tightness will be significant for women,” said Dr. Kilmer, who has used the Viveve device in her practice but was not part of this study.

Based on responses to the FSFI questionnaire, the researchers observed a significant and sustained improvement in sexual function after a single treatment among patients in the treatment group, compared with those in the sham group. The placebo effect didn’t rise above “dysfunctional” at six months, and rate of treatment emergent adverse events was similar between the treatment and sham groups (11.1% vs. 12.3%, respectively), she said.

The researchers also reported the following patient tolerability variables: warmth during the procedure (96% in the treatment group vs. 19% in the sham group, respectively); cool sensation during the procedure (42% vs. 75%), and stopped procedure due to discomfort (1% in each group).

Dr. Kilmer explained that RF heating of the skin and mucosa provides immediate contraction of collagen, long-term stimulation of new collagen production, as well as increased blood flow and restoration of nerve signaling, which results in normal vaginal lubrication. “The critical RF temperature is in the 35 to 47 degree range,” she said. “Very few people can tolerate above 42 degrees.”

Similarly, good results were noted in a pilot study of the ThermiVa radiofrequency product manufactured by ThermoGen in 23 patients who underwent three treatments one month apart (Int J Laser Aesthet Med. July 2015:16-21). All patients experienced significant change with about a 50% reduction in symptoms.

“Patients are very happy with this treatment,” said Dr. Kilmer, who is also a professor of dermatology at the University of California, Davis Medical Center. “It may not be the absolute home run, but I think it’s very safe ... Most people say it lasts about six months then they’ll start to see some of their symptoms coming back.”

Dr. Kilmer reported that she is a member of the medical advisory board for Allergan, Cytrellis, Lumenis, Merz, Miramar, Sienna Labs, Syneron/Candela, Zarin, Zeltiq, and Zift. She has also received research support from those companies as well as from Cutera, Cynosure, Lutronic, R2 Derm, Solta/Valeant, and Ulthera.

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

Maintenance therapy typically required after laser hair removal

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – Hair removal ranks as the most popular laser procedure performed in the United States, but patients with blond, red, or gray hairs are out of luck, since those threadlike strands lack a chromophore for the laser to respond to.

“For now, I recommend that these patients get electrolysis or use eflornithine cream,” Arisa Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Future treatment options for patients with light-colored hair look promising, however. One emerging technology combines laser hair removal with the insertion of a silver nanoparticle into the unpigmented hair follicle. “These are currently in pivotal trials, so we should be seeing them on the market very soon,” she said.

According to Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, there is still a place for nonlaser hair removal, including shaving, waxing, threading, and electrolysis, but laser hair removal is safe, effective in skilled hands, and permanent. Key factors in optimizing treatment include understanding laser safety and laser-tissue interaction, proper patient selection, preoperative preparation, parameter selection, and recognizing complications.

The first-degree target in laser hair removal is eumelanin contained in the bulb of hair follicles, she said, but the heat must diffuse to a secondary target – follicular stem cells in the bulge of the outer root sheath. “Pulse duration is important,” she said. “The thermal relaxation time of a terminal hair follicle is roughly 100 milliseconds. Longer pulse widths are going to be safer for darker skin types, and you want shorter pulse durations for fine hair, and longer pulse durations for thicker hair. Spot size is also important. Larger spot sizes are faster and create less pain and less epidermal damage.”

Indications include unwanted hair, hypertrichosis, and hirsutism/polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). “You want to counsel patients with PCOS properly, because they will require multiple treatments as they tend to make new hair follicles,” she said. Other indications include ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and pilonidal cysts.

The best candidates for laser hair removal are patients who have a light skin color and dark hair, and those who have thick, coarse hair. “Be cautious when treating tanned patients, and adjust your setting to a longer pulse duration and a lower fluence,” she continued. “I tell (patients) they’ll likely need at least six treatments. You want to treat them every 6 to 8 weeks. If you do treatments sooner than that, it’s probably not cost effective for the patient, because of the way hair follicles cycle. It’s also important that they avoid the sun.”

Clinicians can achieve temporary hair removal with Q-switched lasers, which may be suitable for patients with pseudofolliculitis barbae but who may not want permanent hair removal. “This will just vaporize the actual hair follicle, but that heat is not extending to the stem cells, so it’s temporary hair removal, because the hair follicle transitions into the telogen phase,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “The hair will then grow back after a few months.”

Endpoints are the most important factor for laser hair removal. You want to see perifollicular erythema, perifollicular edema, or hair singeing. “Then you know you have an effective treatment setting,” she said. “Sometimes, however, it takes time for this erythema or edema to develop, so you don’t want to keep increasing your fluences to see this end point. If you’re not comfortable with the laser you’re using, I recommend waiting a few minutes after treatment, and looking for the end point. You could always go higher during the next treatment, if you need to.”

Higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, but also with more side effects. “The recommended treatment settings are going to be the highest possible tolerated fluence that yields the desired endpoint without any adverse effects,” Dr. Ortiz said.

The first hair removal laser to hit the market was the Ruby 694-nm laser, which is safe for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. A long-term follow-up of the seminal study showed permanent posttreatment efficacy of up to 2 years (Arch Dermatol. 1998;134[7]:837-42). The Alexandrite 755-nm laser, meanwhile, penetrates deeper because it’s a longer wavelength, so there’s less melanin absorption, and it’s safer for darker skin types. “With a device like this, you want to make sure that you’re always holding the laser perpendicular to the skin surface so that your cryogen spray is firing at the same area as the laser. [That way] you don’t get a burn injury,” she said.

The diode at 800 nm and 810 nm penetrates even deeper, which results in less melanin absorption. “Originally these devices had smaller spot sizes, but now some of the newer devices have larger hand pieces and use contact cooling,” she said. “Some of the diode lasers cause singeing and char. The carbon actually sticks onto the sapphire window of the device, so you want to make sure you swipe the window after every few pulses so that you’re not putting the char onto the epidermis and causing an epidermal burn,” Dr. Ortiz advised.

She described the Nd:YAG 1,064-nm laser as the safest for skin types V and VI. It has the deepest penetration but the least melanin absorption. Intense pulsed light (IPL) can also be used for hair removal. IPLs “have a larger spot size, and you can use various cutoff filters to make them safer for darker skin types,” she said. “However, in head-to-head studies, usually laser hair removal does better than IPL.”

Potential complications from laser hair removal include paradoxical hypertrichosis; pigmentary alterations such as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation; infections/folliculitis, scarring, and eye injury. Dr. Ortiz underscored the importance of counseling patients about the need for maintenance treatments prior to initiating their first hair removal session. Laser hair removal removes about 85-90% of hairs permanently “so that leaves a significant number that remain, and new hairs may grow over time,” she said.

Authors of a recent study found that the plume release during laser hair removal should be considered a potential biohazard that warrants the use of smoke evacuators and good room ventilation (JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152[12]:1320-26). “We are learning that we should be more careful to evacuate the plume from laser hair removal or wear laser protective masks as the plume may contain harmful chemicals that we breathe in on a daily basis,” said Dr. Ortiz, who was not affiliated with the analysis.

She disclosed serving as a consultant to, receiving equipment from, and/or being a member of the scientific board of several device companies, including Alastin, Allergan, BTL, Cutera, InMode, Merz, Revance, Rodan and Fields, Sciton, and Sienna Biopharmaceuticals.

-[email protected]

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – Hair removal ranks as the most popular laser procedure performed in the United States, but patients with blond, red, or gray hairs are out of luck, since those threadlike strands lack a chromophore for the laser to respond to.

“For now, I recommend that these patients get electrolysis or use eflornithine cream,” Arisa Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Future treatment options for patients with light-colored hair look promising, however. One emerging technology combines laser hair removal with the insertion of a silver nanoparticle into the unpigmented hair follicle. “These are currently in pivotal trials, so we should be seeing them on the market very soon,” she said.

According to Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, there is still a place for nonlaser hair removal, including shaving, waxing, threading, and electrolysis, but laser hair removal is safe, effective in skilled hands, and permanent. Key factors in optimizing treatment include understanding laser safety and laser-tissue interaction, proper patient selection, preoperative preparation, parameter selection, and recognizing complications.

The first-degree target in laser hair removal is eumelanin contained in the bulb of hair follicles, she said, but the heat must diffuse to a secondary target – follicular stem cells in the bulge of the outer root sheath. “Pulse duration is important,” she said. “The thermal relaxation time of a terminal hair follicle is roughly 100 milliseconds. Longer pulse widths are going to be safer for darker skin types, and you want shorter pulse durations for fine hair, and longer pulse durations for thicker hair. Spot size is also important. Larger spot sizes are faster and create less pain and less epidermal damage.”

Indications include unwanted hair, hypertrichosis, and hirsutism/polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). “You want to counsel patients with PCOS properly, because they will require multiple treatments as they tend to make new hair follicles,” she said. Other indications include ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and pilonidal cysts.

The best candidates for laser hair removal are patients who have a light skin color and dark hair, and those who have thick, coarse hair. “Be cautious when treating tanned patients, and adjust your setting to a longer pulse duration and a lower fluence,” she continued. “I tell (patients) they’ll likely need at least six treatments. You want to treat them every 6 to 8 weeks. If you do treatments sooner than that, it’s probably not cost effective for the patient, because of the way hair follicles cycle. It’s also important that they avoid the sun.”

Clinicians can achieve temporary hair removal with Q-switched lasers, which may be suitable for patients with pseudofolliculitis barbae but who may not want permanent hair removal. “This will just vaporize the actual hair follicle, but that heat is not extending to the stem cells, so it’s temporary hair removal, because the hair follicle transitions into the telogen phase,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “The hair will then grow back after a few months.”

Endpoints are the most important factor for laser hair removal. You want to see perifollicular erythema, perifollicular edema, or hair singeing. “Then you know you have an effective treatment setting,” she said. “Sometimes, however, it takes time for this erythema or edema to develop, so you don’t want to keep increasing your fluences to see this end point. If you’re not comfortable with the laser you’re using, I recommend waiting a few minutes after treatment, and looking for the end point. You could always go higher during the next treatment, if you need to.”

Higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, but also with more side effects. “The recommended treatment settings are going to be the highest possible tolerated fluence that yields the desired endpoint without any adverse effects,” Dr. Ortiz said.

The first hair removal laser to hit the market was the Ruby 694-nm laser, which is safe for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. A long-term follow-up of the seminal study showed permanent posttreatment efficacy of up to 2 years (Arch Dermatol. 1998;134[7]:837-42). The Alexandrite 755-nm laser, meanwhile, penetrates deeper because it’s a longer wavelength, so there’s less melanin absorption, and it’s safer for darker skin types. “With a device like this, you want to make sure that you’re always holding the laser perpendicular to the skin surface so that your cryogen spray is firing at the same area as the laser. [That way] you don’t get a burn injury,” she said.

The diode at 800 nm and 810 nm penetrates even deeper, which results in less melanin absorption. “Originally these devices had smaller spot sizes, but now some of the newer devices have larger hand pieces and use contact cooling,” she said. “Some of the diode lasers cause singeing and char. The carbon actually sticks onto the sapphire window of the device, so you want to make sure you swipe the window after every few pulses so that you’re not putting the char onto the epidermis and causing an epidermal burn,” Dr. Ortiz advised.

She described the Nd:YAG 1,064-nm laser as the safest for skin types V and VI. It has the deepest penetration but the least melanin absorption. Intense pulsed light (IPL) can also be used for hair removal. IPLs “have a larger spot size, and you can use various cutoff filters to make them safer for darker skin types,” she said. “However, in head-to-head studies, usually laser hair removal does better than IPL.”

Potential complications from laser hair removal include paradoxical hypertrichosis; pigmentary alterations such as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation; infections/folliculitis, scarring, and eye injury. Dr. Ortiz underscored the importance of counseling patients about the need for maintenance treatments prior to initiating their first hair removal session. Laser hair removal removes about 85-90% of hairs permanently “so that leaves a significant number that remain, and new hairs may grow over time,” she said.

Authors of a recent study found that the plume release during laser hair removal should be considered a potential biohazard that warrants the use of smoke evacuators and good room ventilation (JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152[12]:1320-26). “We are learning that we should be more careful to evacuate the plume from laser hair removal or wear laser protective masks as the plume may contain harmful chemicals that we breathe in on a daily basis,” said Dr. Ortiz, who was not affiliated with the analysis.

She disclosed serving as a consultant to, receiving equipment from, and/or being a member of the scientific board of several device companies, including Alastin, Allergan, BTL, Cutera, InMode, Merz, Revance, Rodan and Fields, Sciton, and Sienna Biopharmaceuticals.

-[email protected]

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – Hair removal ranks as the most popular laser procedure performed in the United States, but patients with blond, red, or gray hairs are out of luck, since those threadlike strands lack a chromophore for the laser to respond to.

“For now, I recommend that these patients get electrolysis or use eflornithine cream,” Arisa Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Future treatment options for patients with light-colored hair look promising, however. One emerging technology combines laser hair removal with the insertion of a silver nanoparticle into the unpigmented hair follicle. “These are currently in pivotal trials, so we should be seeing them on the market very soon,” she said.

According to Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, there is still a place for nonlaser hair removal, including shaving, waxing, threading, and electrolysis, but laser hair removal is safe, effective in skilled hands, and permanent. Key factors in optimizing treatment include understanding laser safety and laser-tissue interaction, proper patient selection, preoperative preparation, parameter selection, and recognizing complications.

The first-degree target in laser hair removal is eumelanin contained in the bulb of hair follicles, she said, but the heat must diffuse to a secondary target – follicular stem cells in the bulge of the outer root sheath. “Pulse duration is important,” she said. “The thermal relaxation time of a terminal hair follicle is roughly 100 milliseconds. Longer pulse widths are going to be safer for darker skin types, and you want shorter pulse durations for fine hair, and longer pulse durations for thicker hair. Spot size is also important. Larger spot sizes are faster and create less pain and less epidermal damage.”

Indications include unwanted hair, hypertrichosis, and hirsutism/polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). “You want to counsel patients with PCOS properly, because they will require multiple treatments as they tend to make new hair follicles,” she said. Other indications include ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and pilonidal cysts.

The best candidates for laser hair removal are patients who have a light skin color and dark hair, and those who have thick, coarse hair. “Be cautious when treating tanned patients, and adjust your setting to a longer pulse duration and a lower fluence,” she continued. “I tell (patients) they’ll likely need at least six treatments. You want to treat them every 6 to 8 weeks. If you do treatments sooner than that, it’s probably not cost effective for the patient, because of the way hair follicles cycle. It’s also important that they avoid the sun.”