User login

Pediatric hospitalists take on the challenge of antibiotic stewardship

When Carol Glaser, MD, was in training, the philosophy around antibiotic prescribing often went something like this: “Ten days of antibiotics is good, but let’s do a few more days just to be sure,” she said.

Today, however, the new mantra is “less is more.” Dr. Glaser is an experienced pediatric infectious disease physician and the lead physician for pediatric antimicrobial stewardship at The Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente, at the Oakland (Calif.) Medical Center. While antibiotic stewardship is an issue relevant to nearly all hospitalists, for pediatric patients, the considerations can be unique and particularly serious.

Dr. Shah, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, spoke last spring at HM17, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting. His talk drew from issues raised on pediatric hospital medicine electronic mailing lists and from audience questions. These centered on decisions regarding the use of intravenous versus oral antibiotics for pediatric patients – or what he refers to as intravenous-to-oral conversion – as well as antibiotic treatment duration.

“For many conditions in pediatrics, we used to treat with intravenous antibiotics initially – and sometimes for the entire course – and now we’re using oral antibiotics for the entire course,” Dr. Shah said. He noted that urinary tract infections were once treated with IV antibiotics in the hospital but are now routinely treated orally in an outpatient setting.

Dr. Shah cited two studies, both of which he coauthored as part of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, which compared intravenous versus oral antibiotics treatments given after discharge: The first, published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2014, examined treatment for osteomyelitis, while the second, which focused on complicated pneumonia, was published in Pediatrics in 2016.1,2

Both were observational, retrospective studies involving more than 2,000 children across more than 30 hospitals. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that roughly half of the patients were discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and half were prescribed oral antibiotics. In some hospitals, 100% of patients were sent home with a PICC line, and in others, all children were sent home on oral antibiotics. Although treatment failure rates were the same for both groups, 15% of the patients sent home with a PICC line had to return to the emergency department because of PICC-related complications. Some were hospitalized.1

The Pediatrics study found less variation in PICC versus oral antibiotic use across hospitals for patients with complicated pneumonia, but the treatment failure rate was slightly higher for PICC patients at 3.2%, compared with 2.6% for those on oral antibiotics. This difference, however, was not statistically significant. PICC-related complications were observed in 7.1% of patients with PICC lines also were more likely to experience adverse drug reactions, compared with patients on oral antibiotics.2

“PICC lines have some advantages, particularly when children are unable or unwilling to take oral antibiotics, but they also have risks” said Dr. Shah. “If outcomes are equivalent, why would you subject patients to the risks of a catheter? And, every time they get a fever at home with a PICC line, they need urgent evaluation for the possibility of a catheter-associated bacterial infection. There is an emotional cost, as well, to taking care of catheters in the home setting.”

Additionally, economic pressures are compelling hospitals to reduce costs and resource utilization while maintaining or improving the quality of care, Dr. Shah pointed out. “Hospitalists do many things well, and quality improvement is one of those areas. That approach really aligns with antimicrobial stewardship, and there is greater incentive with episode-based payment models and financial penalties for excess readmissions. Reducing post-discharge IV antibiotic use aligns with stewardship goals and reduces the likelihood of hospital readmissions.”

The hospital medicine division at Dr. Shah’s hospital helped assemble a multidisciplinary team involving emergency physicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, hospitalists, and infectious disease physicians to encourage the use of appropriate, narrow-spectrum antibiotics and reduce the duration of antibiotic therapies. For example, skin and soft-tissue infections that were once treated for 10-14 days are now sufficiently treated in 5-7days. These efforts to improve outcomes through better adherence to evidence-based practices, including better stewardship, earned the team the SHM Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award in 2014.

“Quality improvement is really about changing the system, and hospitalists, who excel in QI, are poised to help drive antimicrobial stewardship efforts,” Dr. Shah said.

At Oakland Medical Center, Dr. Glaser helped implement handshake rounds, an idea they adopted from a group in Colorado. Every day, with every patient, the antimicrobial stewardship team meets with representatives of the teams – pediatric intensive care, the wards, the NICU, and others – to review antibiotic treatment plans for the choice of antimicrobial drug, for the duration of treatment, and for specific conditions. “We work really closely with hospitalists and our strong pediatric pharmacy team every day to ask: ‘Do we have the right dose? Do we really need to use this antibiotic?’ ” Dr. Glaser said.

Last year, she also worked to incorporate antimicrobial stewardship principles into the hospital’s residency program. “I think the most important thing we’re doing is changing the culture,” she said. “For these young physicians, we’re giving them the knowledge to empower them rather than telling them what to do and giving them a better, fundamental understanding of infectious disease.”

For instance, most pediatric respiratory illnesses are caused by a virus, yet physicians will still prescribe antibiotics for a host of reasons – including the expectations of parents, the guesswork that can go into diagnosing a young patient who cannot describe what is wrong, and the fear that children will get sicker if an antibiotic is not started early.

“A lot of it is figuring out the best approach with the least amount of side effects but covering what we need to cover for a given patient,” she said.

A number of physicians from Dr. Glaser’s team presented stewardship data from their hospital at the July 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting in Nashville, demonstrating that, overall, they are using fewer antibiotics and that fewer of those used are broad spectrum. This satisfies the “pillars of stewardship,” Dr. Glaser said. Use antibiotics only when you need them, use them only as long as you need, and then make sure you use the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic you possibly can, she said.

Oakland Medical Center has benefited from a strong commitment to antimicrobial stewardship efforts, Dr. Glaser said, noting that many programs may lack such support, a problem that can be one of the biggest hurdles antimicrobial stewardship efforts face. The support at her hospital “has been an immense help in getting our program to where it is today.”

References

1. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Feb:169(2):120-8.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20161692.

When Carol Glaser, MD, was in training, the philosophy around antibiotic prescribing often went something like this: “Ten days of antibiotics is good, but let’s do a few more days just to be sure,” she said.

Today, however, the new mantra is “less is more.” Dr. Glaser is an experienced pediatric infectious disease physician and the lead physician for pediatric antimicrobial stewardship at The Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente, at the Oakland (Calif.) Medical Center. While antibiotic stewardship is an issue relevant to nearly all hospitalists, for pediatric patients, the considerations can be unique and particularly serious.

Dr. Shah, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, spoke last spring at HM17, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting. His talk drew from issues raised on pediatric hospital medicine electronic mailing lists and from audience questions. These centered on decisions regarding the use of intravenous versus oral antibiotics for pediatric patients – or what he refers to as intravenous-to-oral conversion – as well as antibiotic treatment duration.

“For many conditions in pediatrics, we used to treat with intravenous antibiotics initially – and sometimes for the entire course – and now we’re using oral antibiotics for the entire course,” Dr. Shah said. He noted that urinary tract infections were once treated with IV antibiotics in the hospital but are now routinely treated orally in an outpatient setting.

Dr. Shah cited two studies, both of which he coauthored as part of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, which compared intravenous versus oral antibiotics treatments given after discharge: The first, published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2014, examined treatment for osteomyelitis, while the second, which focused on complicated pneumonia, was published in Pediatrics in 2016.1,2

Both were observational, retrospective studies involving more than 2,000 children across more than 30 hospitals. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that roughly half of the patients were discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and half were prescribed oral antibiotics. In some hospitals, 100% of patients were sent home with a PICC line, and in others, all children were sent home on oral antibiotics. Although treatment failure rates were the same for both groups, 15% of the patients sent home with a PICC line had to return to the emergency department because of PICC-related complications. Some were hospitalized.1

The Pediatrics study found less variation in PICC versus oral antibiotic use across hospitals for patients with complicated pneumonia, but the treatment failure rate was slightly higher for PICC patients at 3.2%, compared with 2.6% for those on oral antibiotics. This difference, however, was not statistically significant. PICC-related complications were observed in 7.1% of patients with PICC lines also were more likely to experience adverse drug reactions, compared with patients on oral antibiotics.2

“PICC lines have some advantages, particularly when children are unable or unwilling to take oral antibiotics, but they also have risks” said Dr. Shah. “If outcomes are equivalent, why would you subject patients to the risks of a catheter? And, every time they get a fever at home with a PICC line, they need urgent evaluation for the possibility of a catheter-associated bacterial infection. There is an emotional cost, as well, to taking care of catheters in the home setting.”

Additionally, economic pressures are compelling hospitals to reduce costs and resource utilization while maintaining or improving the quality of care, Dr. Shah pointed out. “Hospitalists do many things well, and quality improvement is one of those areas. That approach really aligns with antimicrobial stewardship, and there is greater incentive with episode-based payment models and financial penalties for excess readmissions. Reducing post-discharge IV antibiotic use aligns with stewardship goals and reduces the likelihood of hospital readmissions.”

The hospital medicine division at Dr. Shah’s hospital helped assemble a multidisciplinary team involving emergency physicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, hospitalists, and infectious disease physicians to encourage the use of appropriate, narrow-spectrum antibiotics and reduce the duration of antibiotic therapies. For example, skin and soft-tissue infections that were once treated for 10-14 days are now sufficiently treated in 5-7days. These efforts to improve outcomes through better adherence to evidence-based practices, including better stewardship, earned the team the SHM Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award in 2014.

“Quality improvement is really about changing the system, and hospitalists, who excel in QI, are poised to help drive antimicrobial stewardship efforts,” Dr. Shah said.

At Oakland Medical Center, Dr. Glaser helped implement handshake rounds, an idea they adopted from a group in Colorado. Every day, with every patient, the antimicrobial stewardship team meets with representatives of the teams – pediatric intensive care, the wards, the NICU, and others – to review antibiotic treatment plans for the choice of antimicrobial drug, for the duration of treatment, and for specific conditions. “We work really closely with hospitalists and our strong pediatric pharmacy team every day to ask: ‘Do we have the right dose? Do we really need to use this antibiotic?’ ” Dr. Glaser said.

Last year, she also worked to incorporate antimicrobial stewardship principles into the hospital’s residency program. “I think the most important thing we’re doing is changing the culture,” she said. “For these young physicians, we’re giving them the knowledge to empower them rather than telling them what to do and giving them a better, fundamental understanding of infectious disease.”

For instance, most pediatric respiratory illnesses are caused by a virus, yet physicians will still prescribe antibiotics for a host of reasons – including the expectations of parents, the guesswork that can go into diagnosing a young patient who cannot describe what is wrong, and the fear that children will get sicker if an antibiotic is not started early.

“A lot of it is figuring out the best approach with the least amount of side effects but covering what we need to cover for a given patient,” she said.

A number of physicians from Dr. Glaser’s team presented stewardship data from their hospital at the July 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting in Nashville, demonstrating that, overall, they are using fewer antibiotics and that fewer of those used are broad spectrum. This satisfies the “pillars of stewardship,” Dr. Glaser said. Use antibiotics only when you need them, use them only as long as you need, and then make sure you use the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic you possibly can, she said.

Oakland Medical Center has benefited from a strong commitment to antimicrobial stewardship efforts, Dr. Glaser said, noting that many programs may lack such support, a problem that can be one of the biggest hurdles antimicrobial stewardship efforts face. The support at her hospital “has been an immense help in getting our program to where it is today.”

References

1. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Feb:169(2):120-8.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20161692.

When Carol Glaser, MD, was in training, the philosophy around antibiotic prescribing often went something like this: “Ten days of antibiotics is good, but let’s do a few more days just to be sure,” she said.

Today, however, the new mantra is “less is more.” Dr. Glaser is an experienced pediatric infectious disease physician and the lead physician for pediatric antimicrobial stewardship at The Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente, at the Oakland (Calif.) Medical Center. While antibiotic stewardship is an issue relevant to nearly all hospitalists, for pediatric patients, the considerations can be unique and particularly serious.

Dr. Shah, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, spoke last spring at HM17, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting. His talk drew from issues raised on pediatric hospital medicine electronic mailing lists and from audience questions. These centered on decisions regarding the use of intravenous versus oral antibiotics for pediatric patients – or what he refers to as intravenous-to-oral conversion – as well as antibiotic treatment duration.

“For many conditions in pediatrics, we used to treat with intravenous antibiotics initially – and sometimes for the entire course – and now we’re using oral antibiotics for the entire course,” Dr. Shah said. He noted that urinary tract infections were once treated with IV antibiotics in the hospital but are now routinely treated orally in an outpatient setting.

Dr. Shah cited two studies, both of which he coauthored as part of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, which compared intravenous versus oral antibiotics treatments given after discharge: The first, published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2014, examined treatment for osteomyelitis, while the second, which focused on complicated pneumonia, was published in Pediatrics in 2016.1,2

Both were observational, retrospective studies involving more than 2,000 children across more than 30 hospitals. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that roughly half of the patients were discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, and half were prescribed oral antibiotics. In some hospitals, 100% of patients were sent home with a PICC line, and in others, all children were sent home on oral antibiotics. Although treatment failure rates were the same for both groups, 15% of the patients sent home with a PICC line had to return to the emergency department because of PICC-related complications. Some were hospitalized.1

The Pediatrics study found less variation in PICC versus oral antibiotic use across hospitals for patients with complicated pneumonia, but the treatment failure rate was slightly higher for PICC patients at 3.2%, compared with 2.6% for those on oral antibiotics. This difference, however, was not statistically significant. PICC-related complications were observed in 7.1% of patients with PICC lines also were more likely to experience adverse drug reactions, compared with patients on oral antibiotics.2

“PICC lines have some advantages, particularly when children are unable or unwilling to take oral antibiotics, but they also have risks” said Dr. Shah. “If outcomes are equivalent, why would you subject patients to the risks of a catheter? And, every time they get a fever at home with a PICC line, they need urgent evaluation for the possibility of a catheter-associated bacterial infection. There is an emotional cost, as well, to taking care of catheters in the home setting.”

Additionally, economic pressures are compelling hospitals to reduce costs and resource utilization while maintaining or improving the quality of care, Dr. Shah pointed out. “Hospitalists do many things well, and quality improvement is one of those areas. That approach really aligns with antimicrobial stewardship, and there is greater incentive with episode-based payment models and financial penalties for excess readmissions. Reducing post-discharge IV antibiotic use aligns with stewardship goals and reduces the likelihood of hospital readmissions.”

The hospital medicine division at Dr. Shah’s hospital helped assemble a multidisciplinary team involving emergency physicians, pharmacists, nursing staff, hospitalists, and infectious disease physicians to encourage the use of appropriate, narrow-spectrum antibiotics and reduce the duration of antibiotic therapies. For example, skin and soft-tissue infections that were once treated for 10-14 days are now sufficiently treated in 5-7days. These efforts to improve outcomes through better adherence to evidence-based practices, including better stewardship, earned the team the SHM Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award in 2014.

“Quality improvement is really about changing the system, and hospitalists, who excel in QI, are poised to help drive antimicrobial stewardship efforts,” Dr. Shah said.

At Oakland Medical Center, Dr. Glaser helped implement handshake rounds, an idea they adopted from a group in Colorado. Every day, with every patient, the antimicrobial stewardship team meets with representatives of the teams – pediatric intensive care, the wards, the NICU, and others – to review antibiotic treatment plans for the choice of antimicrobial drug, for the duration of treatment, and for specific conditions. “We work really closely with hospitalists and our strong pediatric pharmacy team every day to ask: ‘Do we have the right dose? Do we really need to use this antibiotic?’ ” Dr. Glaser said.

Last year, she also worked to incorporate antimicrobial stewardship principles into the hospital’s residency program. “I think the most important thing we’re doing is changing the culture,” she said. “For these young physicians, we’re giving them the knowledge to empower them rather than telling them what to do and giving them a better, fundamental understanding of infectious disease.”

For instance, most pediatric respiratory illnesses are caused by a virus, yet physicians will still prescribe antibiotics for a host of reasons – including the expectations of parents, the guesswork that can go into diagnosing a young patient who cannot describe what is wrong, and the fear that children will get sicker if an antibiotic is not started early.

“A lot of it is figuring out the best approach with the least amount of side effects but covering what we need to cover for a given patient,” she said.

A number of physicians from Dr. Glaser’s team presented stewardship data from their hospital at the July 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting in Nashville, demonstrating that, overall, they are using fewer antibiotics and that fewer of those used are broad spectrum. This satisfies the “pillars of stewardship,” Dr. Glaser said. Use antibiotics only when you need them, use them only as long as you need, and then make sure you use the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic you possibly can, she said.

Oakland Medical Center has benefited from a strong commitment to antimicrobial stewardship efforts, Dr. Glaser said, noting that many programs may lack such support, a problem that can be one of the biggest hurdles antimicrobial stewardship efforts face. The support at her hospital “has been an immense help in getting our program to where it is today.”

References

1. Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Feb:169(2):120-8.

2. Shah SS, Srivastava R, Wu S, et al. Intravenous versus oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of complicated pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2016 Dec;138(6). pii: e20161692.

FDA approves second CAR-T therapy

A second chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has gained FDA approval, this time for the treatment of large B-cell lymphoma in adults.

“Today marks another milestone in the development of a whole new scientific paradigm for the treatment of serious diseases,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a statement. “This approval demonstrates the continued momentum of this promising new area of medicine, and we’re committed to supporting and helping expedite the development of these products.”

Approval was based on ZUMA-1, a multicenter clinical trial of 101 adults with refractory or relapsed large B-cell lymphoma. Almost three-quarters (72%) of patients responded, including 51% who achieved complete remission.

CAR-T therapy can cause severe, life-threatening side effects, most notably cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicities, for which axicabtagene ciloleucel will carry a boxed warning and will come with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), according to the FDA.

The list price for a single treatment of axicabtagene ciloleucel is $373,000, according to the manufacturer.

“We will soon release a comprehensive policy to address how we plan to support the development of cell-based regenerative medicine,” Dr. Gottlieb said in a statement. “That policy will also clarify how we will apply our expedited programs to breakthrough products that use CAR-T cells and other gene therapies. We remain committed to supporting the efficient development of safe and effective treatments that leverage these new scientific platforms.”

Axicabtagene ciloleucel was developed by Kite Pharma, which was acquired recently by Gilead Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

A second chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has gained FDA approval, this time for the treatment of large B-cell lymphoma in adults.

“Today marks another milestone in the development of a whole new scientific paradigm for the treatment of serious diseases,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a statement. “This approval demonstrates the continued momentum of this promising new area of medicine, and we’re committed to supporting and helping expedite the development of these products.”

Approval was based on ZUMA-1, a multicenter clinical trial of 101 adults with refractory or relapsed large B-cell lymphoma. Almost three-quarters (72%) of patients responded, including 51% who achieved complete remission.

CAR-T therapy can cause severe, life-threatening side effects, most notably cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicities, for which axicabtagene ciloleucel will carry a boxed warning and will come with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), according to the FDA.

The list price for a single treatment of axicabtagene ciloleucel is $373,000, according to the manufacturer.

“We will soon release a comprehensive policy to address how we plan to support the development of cell-based regenerative medicine,” Dr. Gottlieb said in a statement. “That policy will also clarify how we will apply our expedited programs to breakthrough products that use CAR-T cells and other gene therapies. We remain committed to supporting the efficient development of safe and effective treatments that leverage these new scientific platforms.”

Axicabtagene ciloleucel was developed by Kite Pharma, which was acquired recently by Gilead Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

A second chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has gained FDA approval, this time for the treatment of large B-cell lymphoma in adults.

“Today marks another milestone in the development of a whole new scientific paradigm for the treatment of serious diseases,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a statement. “This approval demonstrates the continued momentum of this promising new area of medicine, and we’re committed to supporting and helping expedite the development of these products.”

Approval was based on ZUMA-1, a multicenter clinical trial of 101 adults with refractory or relapsed large B-cell lymphoma. Almost three-quarters (72%) of patients responded, including 51% who achieved complete remission.

CAR-T therapy can cause severe, life-threatening side effects, most notably cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicities, for which axicabtagene ciloleucel will carry a boxed warning and will come with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), according to the FDA.

The list price for a single treatment of axicabtagene ciloleucel is $373,000, according to the manufacturer.

“We will soon release a comprehensive policy to address how we plan to support the development of cell-based regenerative medicine,” Dr. Gottlieb said in a statement. “That policy will also clarify how we will apply our expedited programs to breakthrough products that use CAR-T cells and other gene therapies. We remain committed to supporting the efficient development of safe and effective treatments that leverage these new scientific platforms.”

Axicabtagene ciloleucel was developed by Kite Pharma, which was acquired recently by Gilead Sciences.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

VA Partnership Expands Access to Lung Screening Programs

Lung cancer has an 80% cure rate when caught early, and screening programs are key to providing this chance. The VA and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation have established the VA-Partnership to increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS) Implementation Network.

The initiative builds upon experience gained from other screening programs, the VA says, including those of the VA’s Office of Rural Health, which is supporting the project’s goal to reach veterans living in rural areas. It also adds to a portfolio of other major VA lung cancer initiatives, including the VALOR Trial (Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Or Stereotactic Radiotherapy) and the APOLLO Network (Applied Proteogenomics OrganizationaL Learning and Outcomes).

“Research shows that with comprehensive lung screening programs, early identification of lung cancer leads to more effective treatments and, ultimately, saves lives,” said John Damonti, president of Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, the project’s sponsor.

The project will launch with lung-screening services at the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona by December 2017, and then extend these services to 9 additional VA medical facilities starting in 2018.

Lung cancer has an 80% cure rate when caught early, and screening programs are key to providing this chance. The VA and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation have established the VA-Partnership to increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS) Implementation Network.

The initiative builds upon experience gained from other screening programs, the VA says, including those of the VA’s Office of Rural Health, which is supporting the project’s goal to reach veterans living in rural areas. It also adds to a portfolio of other major VA lung cancer initiatives, including the VALOR Trial (Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Or Stereotactic Radiotherapy) and the APOLLO Network (Applied Proteogenomics OrganizationaL Learning and Outcomes).

“Research shows that with comprehensive lung screening programs, early identification of lung cancer leads to more effective treatments and, ultimately, saves lives,” said John Damonti, president of Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, the project’s sponsor.

The project will launch with lung-screening services at the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona by December 2017, and then extend these services to 9 additional VA medical facilities starting in 2018.

Lung cancer has an 80% cure rate when caught early, and screening programs are key to providing this chance. The VA and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation have established the VA-Partnership to increase Access to Lung Screening (VA-PALS) Implementation Network.

The initiative builds upon experience gained from other screening programs, the VA says, including those of the VA’s Office of Rural Health, which is supporting the project’s goal to reach veterans living in rural areas. It also adds to a portfolio of other major VA lung cancer initiatives, including the VALOR Trial (Veterans Affairs Lung Cancer Or Stereotactic Radiotherapy) and the APOLLO Network (Applied Proteogenomics OrganizationaL Learning and Outcomes).

“Research shows that with comprehensive lung screening programs, early identification of lung cancer leads to more effective treatments and, ultimately, saves lives,” said John Damonti, president of Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, the project’s sponsor.

The project will launch with lung-screening services at the Phoenix VA Health Care System in Arizona by December 2017, and then extend these services to 9 additional VA medical facilities starting in 2018.

This Is No Measly Rash

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

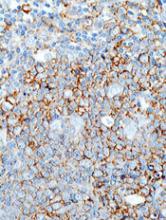

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

A 7-year-old girl is urgently referred to dermatology for a rash of several weeks’ duration. It is the rash itself, rather than any related symptoms, that frightens the family; the possibility of measles (raised by their primary care provider) compounded their concern. Antifungal cream (clotrimazole) has been of no help.

Physically, the child feels fine, without fever or malaise. But further questioning reveals that she was diagnosed with and treated for strep throat “about a month before” the rash developed.

The child was recently adopted by her aunt and uncle after her parents were killed in an automobile accident. This, understandably, has caused her to fall behind in school. She has no pets, no siblings, and no family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

Numerous discrete, round papules and plaques are distributed very evenly on the trunk. They are uniformly scaly and pink, measuring 2 to 3 cm each. In addition, several areas of thick, white, tenacious scaling are seen in the scalp.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and nails are free of any notable change.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of guttate psoriasis, which is genetic in predisposition but triggered by strep in the susceptible patient. It’s tempting to partially attribute this case to the child’s high stress level, but this is purely speculative.

Psoriasis affects about 7 million people in the US—more than 150 million worldwide—in a variety of forms. The guttate morphology is seen primarily in children, with plaques that favor extensor surfaces of the arms, trunk, and legs. Biopsy was not needed in this case; if performed, it would have shown characteristic changes (eg, parakeratosis, fusing of rete ridges).

These changes occur because psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, targets keratinocytes—cells that regenerate over a 28-day period to replace the outer layer of skin as it flakes off. With psoriasis, this process is accelerated; keratinocytes move and slough off within a week, creating scaly, inflamed lesions.

Long-term follow-up is needed to monitor the patient’s overall health, because psoriasis increases comorbidity of conditions such as coronary vessel disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer. In patients with any form of psoriasis, there is the potential for psoriatic arthropathy, a destructive, crippling form of arthropathy that affects up to 25% of all patients. And in a third of guttate psoriasis cases, the condition evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. For this reason, the guttate variety must be treated aggressively with a combination of phototherapy and topical steroids, adequate treatment of any residual strep, and, in adults, the occasional addition of methotrexate.

Regarding the family’s concern, measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause other constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia). The other item in the differential, tinea corporis, involves lesions that are not as uniformly scaly, numerous, or evenly spaced. And with tinea, scaling typically occurs on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Guttate psoriasis is more common in children than in adults and is often triggered by strep infection, though stress has also been implicated as a trigger.

- In about a third of all cases, this type evolves into permanent plaque psoriasis. All patients with psoriasis are at risk for psoriatic arthropathy (25% of patients).

- Measles does not involve scaly papules and plaques and would likely cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, myalgia).

- Tinea corporis lesions are not uniformly scaly, nor would they be as numerous or evenly spaced; most of the scale in tinea is seen on the peripheral leading edge of the lesion.

CAR T-cell therapy approved to treat lymphomas

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™, formerly KTE-C19) for use in adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma who have received 2 or more lines of systemic therapy.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy approved to treat lymphomas.

The approval encompasses diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and transformed follicular lymphoma.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is not approved to treat primary central nervous system lymphoma.

The FDA’s approval of axicabtagene ciloleucel was based on results from the phase 2 ZUMA-1 trial. Updated results from this trial were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

Risks

Axicabtagene ciloleucel has a Boxed Warning in its product label noting that the therapy can cause cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicities. Full prescribing information for axicabtagene ciloleucel is available at https://www.yescarta.com/.

Because of the risk of CRS and neurologic toxicities, axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), which includes elements to assure safe use. The FDA is requiring that hospitals and clinics that dispense axicabtagene ciloleucel be specially certified.

As part of that certification, staff who prescribe, dispense, or administer axicabtagene ciloleucel are required to be trained to recognize and manage CRS and nervous system toxicities. In addition, patients must be informed of the potential serious side effects associated with axicabtagene ciloleucel and of the importance of promptly returning to the treatment site if side effects develop.

Additional information about the REMS program can be found at https://www.yescartarems.com/.

To further evaluate the long-term safety of axicabtagene ciloleucel, the FDA is requiring the manufacturer—Kite, a Gilead company—to conduct a post-marketing observational study of patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel.

Access and cost

The list price of axicabtagene ciloleucel is $373,000.

The product will be manufactured in Kite’s commercial manufacturing facility in El Segundo, California.

In 2017, Kite established a multi-disciplinary field team focused on providing education and logistics training for medical centers. Now, this team has provided final site certification to 16 centers, enabling them to make axicabtagene ciloleucel available to appropriate patients.

Kite is working to train staff at more than 30 additional centers, with an eventual target of 70 to 90 centers across the US. The latest information on authorized centers is available at https://www.yescarta.com/authorized-treatment-centers/. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™, formerly KTE-C19) for use in adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma who have received 2 or more lines of systemic therapy.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy approved to treat lymphomas.

The approval encompasses diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and transformed follicular lymphoma.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is not approved to treat primary central nervous system lymphoma.

The FDA’s approval of axicabtagene ciloleucel was based on results from the phase 2 ZUMA-1 trial. Updated results from this trial were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

Risks

Axicabtagene ciloleucel has a Boxed Warning in its product label noting that the therapy can cause cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicities. Full prescribing information for axicabtagene ciloleucel is available at https://www.yescarta.com/.

Because of the risk of CRS and neurologic toxicities, axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), which includes elements to assure safe use. The FDA is requiring that hospitals and clinics that dispense axicabtagene ciloleucel be specially certified.

As part of that certification, staff who prescribe, dispense, or administer axicabtagene ciloleucel are required to be trained to recognize and manage CRS and nervous system toxicities. In addition, patients must be informed of the potential serious side effects associated with axicabtagene ciloleucel and of the importance of promptly returning to the treatment site if side effects develop.

Additional information about the REMS program can be found at https://www.yescartarems.com/.

To further evaluate the long-term safety of axicabtagene ciloleucel, the FDA is requiring the manufacturer—Kite, a Gilead company—to conduct a post-marketing observational study of patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel.

Access and cost

The list price of axicabtagene ciloleucel is $373,000.

The product will be manufactured in Kite’s commercial manufacturing facility in El Segundo, California.

In 2017, Kite established a multi-disciplinary field team focused on providing education and logistics training for medical centers. Now, this team has provided final site certification to 16 centers, enabling them to make axicabtagene ciloleucel available to appropriate patients.

Kite is working to train staff at more than 30 additional centers, with an eventual target of 70 to 90 centers across the US. The latest information on authorized centers is available at https://www.yescarta.com/authorized-treatment-centers/. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™, formerly KTE-C19) for use in adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma who have received 2 or more lines of systemic therapy.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy approved to treat lymphomas.

The approval encompasses diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and transformed follicular lymphoma.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is not approved to treat primary central nervous system lymphoma.

The FDA’s approval of axicabtagene ciloleucel was based on results from the phase 2 ZUMA-1 trial. Updated results from this trial were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017.

Risks

Axicabtagene ciloleucel has a Boxed Warning in its product label noting that the therapy can cause cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicities. Full prescribing information for axicabtagene ciloleucel is available at https://www.yescarta.com/.

Because of the risk of CRS and neurologic toxicities, axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), which includes elements to assure safe use. The FDA is requiring that hospitals and clinics that dispense axicabtagene ciloleucel be specially certified.

As part of that certification, staff who prescribe, dispense, or administer axicabtagene ciloleucel are required to be trained to recognize and manage CRS and nervous system toxicities. In addition, patients must be informed of the potential serious side effects associated with axicabtagene ciloleucel and of the importance of promptly returning to the treatment site if side effects develop.

Additional information about the REMS program can be found at https://www.yescartarems.com/.

To further evaluate the long-term safety of axicabtagene ciloleucel, the FDA is requiring the manufacturer—Kite, a Gilead company—to conduct a post-marketing observational study of patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel.

Access and cost

The list price of axicabtagene ciloleucel is $373,000.

The product will be manufactured in Kite’s commercial manufacturing facility in El Segundo, California.

In 2017, Kite established a multi-disciplinary field team focused on providing education and logistics training for medical centers. Now, this team has provided final site certification to 16 centers, enabling them to make axicabtagene ciloleucel available to appropriate patients.

Kite is working to train staff at more than 30 additional centers, with an eventual target of 70 to 90 centers across the US. The latest information on authorized centers is available at https://www.yescarta.com/authorized-treatment-centers/. ![]()

Cheek pain

Based on the presence of bilateral Wickham striae, the FP diagnosed oral lichen planus in this patient. If the pattern were unilateral or the patient had a history of tobacco or alcohol use, the FP’s suspicion would have turned to a diagnosis of oral leukoplakia—a precursor to squamous cell carcinoma.

A mid-potency topical steroid is a good initial treatment for oral lichen planus. Triamcinolone can be prescribed in an oral base, but because it is very thick and sticky, it is better for local application to small areas around the teeth. Other treatment options include a gel or ointment, but these are not necessarily better inside the mouth. Most patients will find the cream easier to apply, even if it doesn’t taste good. If a mid-potency steroid doesn’t work, it is possible to use a high-potency steroid and change the vehicle according to the patient’s preference.

The FP in this case prescribed topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily to the buccal mucosa. At follow-up one month later, the patient’s cheeks no longer hurt, and the white Wickham striae were less visible. The FP instructed the patient to continue using the topical steroid twice daily as needed, and to return if her condition worsened.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Kraft RL, Usatine R. Lichen planus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 901-909.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the presence of bilateral Wickham striae, the FP diagnosed oral lichen planus in this patient. If the pattern were unilateral or the patient had a history of tobacco or alcohol use, the FP’s suspicion would have turned to a diagnosis of oral leukoplakia—a precursor to squamous cell carcinoma.

A mid-potency topical steroid is a good initial treatment for oral lichen planus. Triamcinolone can be prescribed in an oral base, but because it is very thick and sticky, it is better for local application to small areas around the teeth. Other treatment options include a gel or ointment, but these are not necessarily better inside the mouth. Most patients will find the cream easier to apply, even if it doesn’t taste good. If a mid-potency steroid doesn’t work, it is possible to use a high-potency steroid and change the vehicle according to the patient’s preference.

The FP in this case prescribed topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily to the buccal mucosa. At follow-up one month later, the patient’s cheeks no longer hurt, and the white Wickham striae were less visible. The FP instructed the patient to continue using the topical steroid twice daily as needed, and to return if her condition worsened.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Kraft RL, Usatine R. Lichen planus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 901-909.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the presence of bilateral Wickham striae, the FP diagnosed oral lichen planus in this patient. If the pattern were unilateral or the patient had a history of tobacco or alcohol use, the FP’s suspicion would have turned to a diagnosis of oral leukoplakia—a precursor to squamous cell carcinoma.

A mid-potency topical steroid is a good initial treatment for oral lichen planus. Triamcinolone can be prescribed in an oral base, but because it is very thick and sticky, it is better for local application to small areas around the teeth. Other treatment options include a gel or ointment, but these are not necessarily better inside the mouth. Most patients will find the cream easier to apply, even if it doesn’t taste good. If a mid-potency steroid doesn’t work, it is possible to use a high-potency steroid and change the vehicle according to the patient’s preference.

The FP in this case prescribed topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream to be applied twice daily to the buccal mucosa. At follow-up one month later, the patient’s cheeks no longer hurt, and the white Wickham striae were less visible. The FP instructed the patient to continue using the topical steroid twice daily as needed, and to return if her condition worsened.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Kraft RL, Usatine R. Lichen planus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 901-909.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

From the Washington Office: Lessons learned from a faithful reader – A tribute to Daniel M. Caruso, MD, FACS

One of the most difficult and unpleasant aspects of being middle-aged is beginning to experience the loss of friends and colleagues who have had a profound impact on one’s life. Those who have been, or continue to be, associated with the department of surgery of Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix recently experienced such a loss with the passing of Daniel M. Caruso, MD, FACS, after a very determined and utterly courageous battle with cancer.

I first came to know Dan 9 years ago when Maricopa Medical Center’s need for a pediatric surgeon and my desire for a different practice situation in the Phoenix area converged, resulting in my becoming a member of his faculty. As my chairman and my friend, Dan had a significant positive impact on me, and though he was chronologically several years my junior, he taught and reinforced life lessons that I will forever carry forward. He was also a faithful reader of this column, and whenever I saw him in Arizona, he always had a kind word about my monthly efforts presented here.

Perhaps Dan’s most admirable trait was his loyalty. He was fiercely loyal to me, his other faculty, the staff of the Arizona Burn Center, and his resident trainees. In turn, he instilled in all around him a profound sense of loyalty to both himself and our department. Nothing exemplifies this better than the “leave no stone unturned” care he received from current faculty, hospital staff, and his former trainees over the last months of his life. In short, he was the leader of his pack.

Dan’s loyalty was not of the “fair weather” sort; it prevailed even in the face of potential adverse circumstances that promised to actually cause him more grief. Nor was his loyalty blind and without limits, as all who were ever in contentious conversation with him have likely been reminded, “I am Sicilian. Don’t put a gun to my head.” That said, his loyalty was, like everything else about him, appropriately measured and extraordinarily genuine, providing for all of us an example toward which to strive.

Being measured in all one’s responses to the adversity presented by others is another valuable lesson Dan taught me. I can only imagine the headaches, anxiety, and stress of being the chair of a department largely made up of “passionate” mid-career surgeons during tumultuous times of continuous change. Despite the fact that many of us frequently urged him to be more forceful, just say “no,” or otherwise flex his or our collective muscle, Dan was forever the calm voice in the storm, reacting in a measured way that was much more reminiscent of honey than vinegar. Dan provided indisputable evidence that your grandmother was correct when she told you that you will catch more flies that way.

Nowhere were these qualities more preeminently displayed than in the administration of the surgical residency program at Maricopa. As is common to most academically affiliated, community-based surgery programs, much of our collective identity as a department was cloaked in the residency program and our trainees. Being a product of the program himself, Dan was the consummate “keeper of the flame.” He was also a superb judge of character and surgical aptitude and the unsurpassed prophet of future success. He was a passionate advocate for those residents in whom he saw promise even when his view was aggressively challenged by others in the department who felt otherwise.

In the case of residents whose flaws in the form of either “expressions of youth” or academic performance caused some faculty to have a negative opinion, Dan remained singularly focused on what he saw as their future potential. He not only protected them, but also saw to it that they were provided every resource available to succeed. He ensured that all trainees who met his muster by working hard and taking excellent care of the patients were given every opportunity to succeed. When appropriate and necessary, his profound insight into others’ talents combined with his compassionate demeanor made him particularly well suited to make suggestions, to the very few, that they might be happier and more successful in a specialty other than surgery. In sum, he had an unsurpassed passion for training the next generation of surgeons, paying it forward into the future as he went.

Dan had both a profound sense of justice and a keen political sense about how and when to strategically best use his position and influence to ensure fairness of outcomes. Amongst his faculty, he was particularly adept at discerning whose talents were best suited to specific tasks and thus, whom he should assign to ensure the optimal outcome for the department, our trainees, and our patients. When once I met with him to express my profound concerns relative to how members of our department were being treated by a certain hospital committee, his response was to act swiftly to ensure that I was appointed to that committee. By doing so, he showed that he trusted my judgment to look out for the interests of our department whilst simultaneously resolving my own concerns. He also gently reinforced the valuable life lesson of not going to your boss only with a problem. Take along that potential solution as well.

As I look forward to Clinical Congress and seeing familiar faces from the “Copa,” past and present, I anticipate many firm handshakes and warm embraces as well as a few tears shed in shared grief. Plain and simple, Dan was the consummate critical care/burn surgeon, a passionate surgical educator, and overall, epitomized the phrase, “great guy.” Our world is a far better place because of his 53 years of labor in the fields of this life.

Somewhere, a red Ferrari with a Detroit Lions license plate is humming down a flat stretch of highway at a clearly excessive rate of speed with Bob Seger blasting from the stereo ...

Well done, my friend. Very well done.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

One of the most difficult and unpleasant aspects of being middle-aged is beginning to experience the loss of friends and colleagues who have had a profound impact on one’s life. Those who have been, or continue to be, associated with the department of surgery of Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix recently experienced such a loss with the passing of Daniel M. Caruso, MD, FACS, after a very determined and utterly courageous battle with cancer.

I first came to know Dan 9 years ago when Maricopa Medical Center’s need for a pediatric surgeon and my desire for a different practice situation in the Phoenix area converged, resulting in my becoming a member of his faculty. As my chairman and my friend, Dan had a significant positive impact on me, and though he was chronologically several years my junior, he taught and reinforced life lessons that I will forever carry forward. He was also a faithful reader of this column, and whenever I saw him in Arizona, he always had a kind word about my monthly efforts presented here.

Perhaps Dan’s most admirable trait was his loyalty. He was fiercely loyal to me, his other faculty, the staff of the Arizona Burn Center, and his resident trainees. In turn, he instilled in all around him a profound sense of loyalty to both himself and our department. Nothing exemplifies this better than the “leave no stone unturned” care he received from current faculty, hospital staff, and his former trainees over the last months of his life. In short, he was the leader of his pack.

Dan’s loyalty was not of the “fair weather” sort; it prevailed even in the face of potential adverse circumstances that promised to actually cause him more grief. Nor was his loyalty blind and without limits, as all who were ever in contentious conversation with him have likely been reminded, “I am Sicilian. Don’t put a gun to my head.” That said, his loyalty was, like everything else about him, appropriately measured and extraordinarily genuine, providing for all of us an example toward which to strive.

Being measured in all one’s responses to the adversity presented by others is another valuable lesson Dan taught me. I can only imagine the headaches, anxiety, and stress of being the chair of a department largely made up of “passionate” mid-career surgeons during tumultuous times of continuous change. Despite the fact that many of us frequently urged him to be more forceful, just say “no,” or otherwise flex his or our collective muscle, Dan was forever the calm voice in the storm, reacting in a measured way that was much more reminiscent of honey than vinegar. Dan provided indisputable evidence that your grandmother was correct when she told you that you will catch more flies that way.

Nowhere were these qualities more preeminently displayed than in the administration of the surgical residency program at Maricopa. As is common to most academically affiliated, community-based surgery programs, much of our collective identity as a department was cloaked in the residency program and our trainees. Being a product of the program himself, Dan was the consummate “keeper of the flame.” He was also a superb judge of character and surgical aptitude and the unsurpassed prophet of future success. He was a passionate advocate for those residents in whom he saw promise even when his view was aggressively challenged by others in the department who felt otherwise.

In the case of residents whose flaws in the form of either “expressions of youth” or academic performance caused some faculty to have a negative opinion, Dan remained singularly focused on what he saw as their future potential. He not only protected them, but also saw to it that they were provided every resource available to succeed. He ensured that all trainees who met his muster by working hard and taking excellent care of the patients were given every opportunity to succeed. When appropriate and necessary, his profound insight into others’ talents combined with his compassionate demeanor made him particularly well suited to make suggestions, to the very few, that they might be happier and more successful in a specialty other than surgery. In sum, he had an unsurpassed passion for training the next generation of surgeons, paying it forward into the future as he went.

Dan had both a profound sense of justice and a keen political sense about how and when to strategically best use his position and influence to ensure fairness of outcomes. Amongst his faculty, he was particularly adept at discerning whose talents were best suited to specific tasks and thus, whom he should assign to ensure the optimal outcome for the department, our trainees, and our patients. When once I met with him to express my profound concerns relative to how members of our department were being treated by a certain hospital committee, his response was to act swiftly to ensure that I was appointed to that committee. By doing so, he showed that he trusted my judgment to look out for the interests of our department whilst simultaneously resolving my own concerns. He also gently reinforced the valuable life lesson of not going to your boss only with a problem. Take along that potential solution as well.

As I look forward to Clinical Congress and seeing familiar faces from the “Copa,” past and present, I anticipate many firm handshakes and warm embraces as well as a few tears shed in shared grief. Plain and simple, Dan was the consummate critical care/burn surgeon, a passionate surgical educator, and overall, epitomized the phrase, “great guy.” Our world is a far better place because of his 53 years of labor in the fields of this life.

Somewhere, a red Ferrari with a Detroit Lions license plate is humming down a flat stretch of highway at a clearly excessive rate of speed with Bob Seger blasting from the stereo ...

Well done, my friend. Very well done.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

One of the most difficult and unpleasant aspects of being middle-aged is beginning to experience the loss of friends and colleagues who have had a profound impact on one’s life. Those who have been, or continue to be, associated with the department of surgery of Maricopa Medical Center in Phoenix recently experienced such a loss with the passing of Daniel M. Caruso, MD, FACS, after a very determined and utterly courageous battle with cancer.

I first came to know Dan 9 years ago when Maricopa Medical Center’s need for a pediatric surgeon and my desire for a different practice situation in the Phoenix area converged, resulting in my becoming a member of his faculty. As my chairman and my friend, Dan had a significant positive impact on me, and though he was chronologically several years my junior, he taught and reinforced life lessons that I will forever carry forward. He was also a faithful reader of this column, and whenever I saw him in Arizona, he always had a kind word about my monthly efforts presented here.

Perhaps Dan’s most admirable trait was his loyalty. He was fiercely loyal to me, his other faculty, the staff of the Arizona Burn Center, and his resident trainees. In turn, he instilled in all around him a profound sense of loyalty to both himself and our department. Nothing exemplifies this better than the “leave no stone unturned” care he received from current faculty, hospital staff, and his former trainees over the last months of his life. In short, he was the leader of his pack.

Dan’s loyalty was not of the “fair weather” sort; it prevailed even in the face of potential adverse circumstances that promised to actually cause him more grief. Nor was his loyalty blind and without limits, as all who were ever in contentious conversation with him have likely been reminded, “I am Sicilian. Don’t put a gun to my head.” That said, his loyalty was, like everything else about him, appropriately measured and extraordinarily genuine, providing for all of us an example toward which to strive.

Being measured in all one’s responses to the adversity presented by others is another valuable lesson Dan taught me. I can only imagine the headaches, anxiety, and stress of being the chair of a department largely made up of “passionate” mid-career surgeons during tumultuous times of continuous change. Despite the fact that many of us frequently urged him to be more forceful, just say “no,” or otherwise flex his or our collective muscle, Dan was forever the calm voice in the storm, reacting in a measured way that was much more reminiscent of honey than vinegar. Dan provided indisputable evidence that your grandmother was correct when she told you that you will catch more flies that way.

Nowhere were these qualities more preeminently displayed than in the administration of the surgical residency program at Maricopa. As is common to most academically affiliated, community-based surgery programs, much of our collective identity as a department was cloaked in the residency program and our trainees. Being a product of the program himself, Dan was the consummate “keeper of the flame.” He was also a superb judge of character and surgical aptitude and the unsurpassed prophet of future success. He was a passionate advocate for those residents in whom he saw promise even when his view was aggressively challenged by others in the department who felt otherwise.

In the case of residents whose flaws in the form of either “expressions of youth” or academic performance caused some faculty to have a negative opinion, Dan remained singularly focused on what he saw as their future potential. He not only protected them, but also saw to it that they were provided every resource available to succeed. He ensured that all trainees who met his muster by working hard and taking excellent care of the patients were given every opportunity to succeed. When appropriate and necessary, his profound insight into others’ talents combined with his compassionate demeanor made him particularly well suited to make suggestions, to the very few, that they might be happier and more successful in a specialty other than surgery. In sum, he had an unsurpassed passion for training the next generation of surgeons, paying it forward into the future as he went.

Dan had both a profound sense of justice and a keen political sense about how and when to strategically best use his position and influence to ensure fairness of outcomes. Amongst his faculty, he was particularly adept at discerning whose talents were best suited to specific tasks and thus, whom he should assign to ensure the optimal outcome for the department, our trainees, and our patients. When once I met with him to express my profound concerns relative to how members of our department were being treated by a certain hospital committee, his response was to act swiftly to ensure that I was appointed to that committee. By doing so, he showed that he trusted my judgment to look out for the interests of our department whilst simultaneously resolving my own concerns. He also gently reinforced the valuable life lesson of not going to your boss only with a problem. Take along that potential solution as well.

As I look forward to Clinical Congress and seeing familiar faces from the “Copa,” past and present, I anticipate many firm handshakes and warm embraces as well as a few tears shed in shared grief. Plain and simple, Dan was the consummate critical care/burn surgeon, a passionate surgical educator, and overall, epitomized the phrase, “great guy.” Our world is a far better place because of his 53 years of labor in the fields of this life.

Somewhere, a red Ferrari with a Detroit Lions license plate is humming down a flat stretch of highway at a clearly excessive rate of speed with Bob Seger blasting from the stereo ...

Well done, my friend. Very well done.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

The opioid epidemic, surgeons, and palliative care

Recent public and professional attention to what is now called the opioid epidemic has obvious implications for surgery and palliative care. Because of the status of “epidemic,” there is a sense of urgency within the surgical and palliative care community to reevaluate the assessment and treatment of patients for whom opioid therapy is being considered.

Although the liberal use of opioids is a common stereotype of palliative care, the use of opioids in the palliative care setting is part of a complex assessment and treatment process. Opioid use in this setting is analogous to palliative surgery in the surgical palliative care setting: It is one tool, and it is most effective and safe when based on an assessment of the more general picture. A fundamental concept of palliative care, “total pain,” provides a basis for improved pain management that goes far beyond the use and dependency on opioid therapy. Dame Cicely Saunders, who was mentored by a surgeon and later became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, defined the concept of total pain as the suffering that encompasses all of a person’s physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical struggles (BMJ. 2005 Jul 23;331[7510]:238). Blake Cady, a preeminent surgeon and surgical educator, once wrote that the day-to-day decisions in surgery are best made in the context of a surgical philosophy of care (J Am Coll Surg. 2005 Feb;200[2]:285-90). This applies to all interventions. Total-pain assessment provides us the opportunity to identify nonphysical factors associated with pain that might not indicate opioid use or even contraindicate their use. Existential distress or spiritual pain in a delirious or underassessed patient can be indistinguishable from physical distress. Socioeconomic factors, such as an inability to pay for medical care, can present as pain.

Surgeons are uniquely positioned as “listening posts” in the overall campaign to curb opioid misuse. They can identify patients at risk for or diagnosed with substance use disorder so they can be managed or referred for specialist treatment appropriately.

Awareness of other dimensions of pain will enhance their efficacy in this role.

Opioid sparing is a key tactic in the strategy for controlling opioid use and minimizing opioid-induced side effects. Occasionally surgical or interventional radiologic procedures are useful for this purpose.

There are immediate, specific actions surgeons can take in order to constructively participate in opioid use reform:

- Expand your patient’s pain history to include nonphysical dimensions of pain and refer appropriately.

- Know your opioids; carry an opioid conversion table. Errors in opioid conversion can result in significant undertreatment of pain but can result in overdosage just as easily.

- Know your pharmacist. Pharmacists are valuable allies in safe opioid prescribing and monitoring practices.

- Be wary of “standardized” order sets that include opioids. There is no standard dose or standard patient as we are rapidly learning from genomics.

- Utilize your state’s patient drug-monitoring program – a new pain for clinicians, but some headaches are worth it. It clearly has already put the brakes on opioid prescribing.