User login

FDA okays dosing software for hemophilia A

The Food and Drug Administration has granted 510(k) clearance to myPKFiT for ADVATE (Antihemophilic Factor, Recombinant), pharmokinetic dosing software used for tailoring prophylaxis regimens for hemophilia A patients.

The software can be used for hemophilia A patients aged 16 years or older who weigh at least 45 kilograms (about 99 pounds) and are treated with ADVATE.

The software is expected to be available in the United States by the end of the first quarter of 2018. A version of the software is already marketed in Europe.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted 510(k) clearance to myPKFiT for ADVATE (Antihemophilic Factor, Recombinant), pharmokinetic dosing software used for tailoring prophylaxis regimens for hemophilia A patients.

The software can be used for hemophilia A patients aged 16 years or older who weigh at least 45 kilograms (about 99 pounds) and are treated with ADVATE.

The software is expected to be available in the United States by the end of the first quarter of 2018. A version of the software is already marketed in Europe.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted 510(k) clearance to myPKFiT for ADVATE (Antihemophilic Factor, Recombinant), pharmokinetic dosing software used for tailoring prophylaxis regimens for hemophilia A patients.

The software can be used for hemophilia A patients aged 16 years or older who weigh at least 45 kilograms (about 99 pounds) and are treated with ADVATE.

The software is expected to be available in the United States by the end of the first quarter of 2018. A version of the software is already marketed in Europe.

Link between glucose control and CVD risk: It’s complicated

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2017

LOS ANGELES – If you think the link between glucose control and cardiovascular disease is complicated, you’re not alone.

“Glucose is not the only risk factor for CVD, and it may not be the most important risk factor,” Peter Reaven, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “Controlling blood pressure and lipids is also quite important. In current studies, patients with diabetes are aggressively treated for other risk factors with many vascular-acting medications, so it’s difficult to show the benefits of glucose lowering on its own. That is pertinent because it’s becoming clear that the benefits of glucose lowering may take a long time. How, and in whom, one controls glucose may influence the outcome.

Medications, hypoglycemia, glucose variation, and extent of disease all may influence vascular responses to glucose lowering.”

Dr. Reaven, an endocrinologist who directs the Diabetes Research Program at the University of Arizona and VA Health Care System, Phoenix, noted that, while a consistent body of evidence supports an association between higher levels of glucose and increased risk for CVD, it’s not as clear that tight control efforts decrease a patient’s risk for CVD at the microvascular and macrovascular level. “We also appreciate that complications from intensive glucose lowering – such as hypoglycemia, weight gain, time and cost, and increased mortality – are not minimal,” he said.

A meta-analysis of 27,049 patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in four major trials found that those who were allocated to more-intensive, compared with less-intensive, glucose control had a reduced risk of major cardiovascular events by 9% (hazard ratio, 0.91), primarily because of a 15% reduced risk of myocardial infarction (Diabetologia 2009;52[11] 2288-98). “None of these studies actually achieved statistical significance, but they all showed a modest trend,” said Dr. Reaven, who was not involved in the meta-analysis. At the same time, interim data from the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial follow-up study (VADT-F) showed that, after about 10 years, the median HbA1c levels were similar between patients who had received either intensive or standard glucose for a median of 5.6 years in the initial VADT trial (N Engl J Med. 2009;360[2]:129-39). Other risk factors between the two groups were similar, including LDL and systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

In this extended follow-up of the VADT, a 17% reduction in CVD was observed among patients who were treated more intensively, compared with those on standard therapy, after about 12 years of treatment (P = .04; N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2197-206). “Why does it take so long?” he asked. “Why does it take 10-plus years of mean follow-up with an HbA1c separation of 1.5% to start to lead to cardiovascular events? The reality is, we don’t know the answer.”

It’s possible that many years of hyperglycemia created enough vascular injury and long-term consequences that are not easily turned around in short intervals, but Dr. Reaven noted that advanced glycation and oxidation products might also be contributing to long-term vascular legacy events. In an analysis of patients from the VADT-F, he and his associates found that specific advanced glycation end products and oxidation products are associated with the severity of subclinical atherosclerosis over the long term and may play an important role in the “negative metabolic memory” of macrovascular complications in people with long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus (Diabetes Care 2017;40[4]:591-8). In particular, the combination of 3-deoxyglucosone hydroimidazolone and glyoxal hydroimidazolone and 2-aminoadipic acid was strongly associated with all measures of subclinical atherosclerosis.

In the initial VADT trial, severe hypoglycemia occurred nearly three times more commonly in the intensively treated group, compared with the standard therapy group. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as an episode of low blood glucose that was accompanied by confusion requiring assistance from another person or loss of consciousness. In related analyses, the hazard ratio for CV events, CV mortality, and overall mortality with severe hypoglycemia within the preceding 3 months was also increased. “So this is a consistent finding across multiple studies of the danger of severe hypoglycemia occurring during your efforts to improve glucose lowering,” Dr. Reaven said. “Interestingly, it appears that the risk for CVD events following severe hypoglycemia increases with higher baseline CV risk, based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 10-year CV risk score. So, how great your risk is begins to influence how well you do after severe hypoglycemia.”

In a separate stratified analysis of VADT data, the risk for CVD after severe hypoglycemia was more prominent in the standard treatment group, compared with the intensive treatment group. “There’s nearly a sevenfold increased risk for all-cause mortality following severe hypoglycemia in the preceding 3 months,” he said. “The same pattern is present for cardiovascular mortality and, somewhat, for cardiovascular events, although not statistically significant. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes was seen in the ACCORD [Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes] population as well.”

A subset of patients in the VADT study showed that individuals in the standard therapy group who had a prior serious hypoglycemic episode actually had greater coronary calcium progression during the study, compared with the intensively treated group (P = .02; Diabetes Care 2016;39[3]:448-54). “One possibility is that serious hypoglycemia contributed to the development of atherosclerosis in this group,” Dr. Reaven said. “This held true when one examined high and lower glucose levels on average in the study. Those individuals that had A1c levels of 7.5% or above were the ones that appeared to show coronary calcium progression during the study following episodes of severe hypoglycemia, whereas it did not appear to be an issue among those with good glucose control. Another finding was that severe hypoglycemia is associated with increased glucose variability from office visit to office visit.”

He concluded his remarks by noting that being “glucose centric” is not the right approach to treating patients with diabetes. “Other risk factors may offer bigger and more rapid benefits,” he said. “The benefits of glucose lowering are likely most relevant in type 1 diabetes and in early type 2 diabetes, and the benefits of glucose lowering on vascular disease appear to take a long time. Avoid severe hypoglycemia, especially in older patients with type 2 diabetes. This last point may be particularly relevant for those in poor control.”

Dr. Reaven reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2017

LOS ANGELES – If you think the link between glucose control and cardiovascular disease is complicated, you’re not alone.

“Glucose is not the only risk factor for CVD, and it may not be the most important risk factor,” Peter Reaven, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “Controlling blood pressure and lipids is also quite important. In current studies, patients with diabetes are aggressively treated for other risk factors with many vascular-acting medications, so it’s difficult to show the benefits of glucose lowering on its own. That is pertinent because it’s becoming clear that the benefits of glucose lowering may take a long time. How, and in whom, one controls glucose may influence the outcome.

Medications, hypoglycemia, glucose variation, and extent of disease all may influence vascular responses to glucose lowering.”

Dr. Reaven, an endocrinologist who directs the Diabetes Research Program at the University of Arizona and VA Health Care System, Phoenix, noted that, while a consistent body of evidence supports an association between higher levels of glucose and increased risk for CVD, it’s not as clear that tight control efforts decrease a patient’s risk for CVD at the microvascular and macrovascular level. “We also appreciate that complications from intensive glucose lowering – such as hypoglycemia, weight gain, time and cost, and increased mortality – are not minimal,” he said.

A meta-analysis of 27,049 patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in four major trials found that those who were allocated to more-intensive, compared with less-intensive, glucose control had a reduced risk of major cardiovascular events by 9% (hazard ratio, 0.91), primarily because of a 15% reduced risk of myocardial infarction (Diabetologia 2009;52[11] 2288-98). “None of these studies actually achieved statistical significance, but they all showed a modest trend,” said Dr. Reaven, who was not involved in the meta-analysis. At the same time, interim data from the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial follow-up study (VADT-F) showed that, after about 10 years, the median HbA1c levels were similar between patients who had received either intensive or standard glucose for a median of 5.6 years in the initial VADT trial (N Engl J Med. 2009;360[2]:129-39). Other risk factors between the two groups were similar, including LDL and systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

In this extended follow-up of the VADT, a 17% reduction in CVD was observed among patients who were treated more intensively, compared with those on standard therapy, after about 12 years of treatment (P = .04; N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2197-206). “Why does it take so long?” he asked. “Why does it take 10-plus years of mean follow-up with an HbA1c separation of 1.5% to start to lead to cardiovascular events? The reality is, we don’t know the answer.”

It’s possible that many years of hyperglycemia created enough vascular injury and long-term consequences that are not easily turned around in short intervals, but Dr. Reaven noted that advanced glycation and oxidation products might also be contributing to long-term vascular legacy events. In an analysis of patients from the VADT-F, he and his associates found that specific advanced glycation end products and oxidation products are associated with the severity of subclinical atherosclerosis over the long term and may play an important role in the “negative metabolic memory” of macrovascular complications in people with long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus (Diabetes Care 2017;40[4]:591-8). In particular, the combination of 3-deoxyglucosone hydroimidazolone and glyoxal hydroimidazolone and 2-aminoadipic acid was strongly associated with all measures of subclinical atherosclerosis.

In the initial VADT trial, severe hypoglycemia occurred nearly three times more commonly in the intensively treated group, compared with the standard therapy group. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as an episode of low blood glucose that was accompanied by confusion requiring assistance from another person or loss of consciousness. In related analyses, the hazard ratio for CV events, CV mortality, and overall mortality with severe hypoglycemia within the preceding 3 months was also increased. “So this is a consistent finding across multiple studies of the danger of severe hypoglycemia occurring during your efforts to improve glucose lowering,” Dr. Reaven said. “Interestingly, it appears that the risk for CVD events following severe hypoglycemia increases with higher baseline CV risk, based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 10-year CV risk score. So, how great your risk is begins to influence how well you do after severe hypoglycemia.”

In a separate stratified analysis of VADT data, the risk for CVD after severe hypoglycemia was more prominent in the standard treatment group, compared with the intensive treatment group. “There’s nearly a sevenfold increased risk for all-cause mortality following severe hypoglycemia in the preceding 3 months,” he said. “The same pattern is present for cardiovascular mortality and, somewhat, for cardiovascular events, although not statistically significant. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes was seen in the ACCORD [Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes] population as well.”

A subset of patients in the VADT study showed that individuals in the standard therapy group who had a prior serious hypoglycemic episode actually had greater coronary calcium progression during the study, compared with the intensively treated group (P = .02; Diabetes Care 2016;39[3]:448-54). “One possibility is that serious hypoglycemia contributed to the development of atherosclerosis in this group,” Dr. Reaven said. “This held true when one examined high and lower glucose levels on average in the study. Those individuals that had A1c levels of 7.5% or above were the ones that appeared to show coronary calcium progression during the study following episodes of severe hypoglycemia, whereas it did not appear to be an issue among those with good glucose control. Another finding was that severe hypoglycemia is associated with increased glucose variability from office visit to office visit.”

He concluded his remarks by noting that being “glucose centric” is not the right approach to treating patients with diabetes. “Other risk factors may offer bigger and more rapid benefits,” he said. “The benefits of glucose lowering are likely most relevant in type 1 diabetes and in early type 2 diabetes, and the benefits of glucose lowering on vascular disease appear to take a long time. Avoid severe hypoglycemia, especially in older patients with type 2 diabetes. This last point may be particularly relevant for those in poor control.”

Dr. Reaven reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2017

LOS ANGELES – If you think the link between glucose control and cardiovascular disease is complicated, you’re not alone.

“Glucose is not the only risk factor for CVD, and it may not be the most important risk factor,” Peter Reaven, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “Controlling blood pressure and lipids is also quite important. In current studies, patients with diabetes are aggressively treated for other risk factors with many vascular-acting medications, so it’s difficult to show the benefits of glucose lowering on its own. That is pertinent because it’s becoming clear that the benefits of glucose lowering may take a long time. How, and in whom, one controls glucose may influence the outcome.

Medications, hypoglycemia, glucose variation, and extent of disease all may influence vascular responses to glucose lowering.”

Dr. Reaven, an endocrinologist who directs the Diabetes Research Program at the University of Arizona and VA Health Care System, Phoenix, noted that, while a consistent body of evidence supports an association between higher levels of glucose and increased risk for CVD, it’s not as clear that tight control efforts decrease a patient’s risk for CVD at the microvascular and macrovascular level. “We also appreciate that complications from intensive glucose lowering – such as hypoglycemia, weight gain, time and cost, and increased mortality – are not minimal,” he said.

A meta-analysis of 27,049 patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in four major trials found that those who were allocated to more-intensive, compared with less-intensive, glucose control had a reduced risk of major cardiovascular events by 9% (hazard ratio, 0.91), primarily because of a 15% reduced risk of myocardial infarction (Diabetologia 2009;52[11] 2288-98). “None of these studies actually achieved statistical significance, but they all showed a modest trend,” said Dr. Reaven, who was not involved in the meta-analysis. At the same time, interim data from the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial follow-up study (VADT-F) showed that, after about 10 years, the median HbA1c levels were similar between patients who had received either intensive or standard glucose for a median of 5.6 years in the initial VADT trial (N Engl J Med. 2009;360[2]:129-39). Other risk factors between the two groups were similar, including LDL and systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

In this extended follow-up of the VADT, a 17% reduction in CVD was observed among patients who were treated more intensively, compared with those on standard therapy, after about 12 years of treatment (P = .04; N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2197-206). “Why does it take so long?” he asked. “Why does it take 10-plus years of mean follow-up with an HbA1c separation of 1.5% to start to lead to cardiovascular events? The reality is, we don’t know the answer.”

It’s possible that many years of hyperglycemia created enough vascular injury and long-term consequences that are not easily turned around in short intervals, but Dr. Reaven noted that advanced glycation and oxidation products might also be contributing to long-term vascular legacy events. In an analysis of patients from the VADT-F, he and his associates found that specific advanced glycation end products and oxidation products are associated with the severity of subclinical atherosclerosis over the long term and may play an important role in the “negative metabolic memory” of macrovascular complications in people with long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus (Diabetes Care 2017;40[4]:591-8). In particular, the combination of 3-deoxyglucosone hydroimidazolone and glyoxal hydroimidazolone and 2-aminoadipic acid was strongly associated with all measures of subclinical atherosclerosis.

In the initial VADT trial, severe hypoglycemia occurred nearly three times more commonly in the intensively treated group, compared with the standard therapy group. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as an episode of low blood glucose that was accompanied by confusion requiring assistance from another person or loss of consciousness. In related analyses, the hazard ratio for CV events, CV mortality, and overall mortality with severe hypoglycemia within the preceding 3 months was also increased. “So this is a consistent finding across multiple studies of the danger of severe hypoglycemia occurring during your efforts to improve glucose lowering,” Dr. Reaven said. “Interestingly, it appears that the risk for CVD events following severe hypoglycemia increases with higher baseline CV risk, based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 10-year CV risk score. So, how great your risk is begins to influence how well you do after severe hypoglycemia.”

In a separate stratified analysis of VADT data, the risk for CVD after severe hypoglycemia was more prominent in the standard treatment group, compared with the intensive treatment group. “There’s nearly a sevenfold increased risk for all-cause mortality following severe hypoglycemia in the preceding 3 months,” he said. “The same pattern is present for cardiovascular mortality and, somewhat, for cardiovascular events, although not statistically significant. The association between symptomatic, severe hypoglycemia and mortality in type 2 diabetes was seen in the ACCORD [Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes] population as well.”

A subset of patients in the VADT study showed that individuals in the standard therapy group who had a prior serious hypoglycemic episode actually had greater coronary calcium progression during the study, compared with the intensively treated group (P = .02; Diabetes Care 2016;39[3]:448-54). “One possibility is that serious hypoglycemia contributed to the development of atherosclerosis in this group,” Dr. Reaven said. “This held true when one examined high and lower glucose levels on average in the study. Those individuals that had A1c levels of 7.5% or above were the ones that appeared to show coronary calcium progression during the study following episodes of severe hypoglycemia, whereas it did not appear to be an issue among those with good glucose control. Another finding was that severe hypoglycemia is associated with increased glucose variability from office visit to office visit.”

He concluded his remarks by noting that being “glucose centric” is not the right approach to treating patients with diabetes. “Other risk factors may offer bigger and more rapid benefits,” he said. “The benefits of glucose lowering are likely most relevant in type 1 diabetes and in early type 2 diabetes, and the benefits of glucose lowering on vascular disease appear to take a long time. Avoid severe hypoglycemia, especially in older patients with type 2 diabetes. This last point may be particularly relevant for those in poor control.”

Dr. Reaven reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Intraoperative Use of External Fixator Attachments for Reduction of Lower Extremity Fractures and Dislocations

Take-Home Points

- External fixator attachments are fast and easy to assemble with existing external fixator equipment.

- They allow for multi-directional force application and use of extrinsic power grip.

- They limit radiation exposure and provides unobstructred line of sight to zone of injury.

- The attachments can then be removed once reduction is achieved.

External fixation has a long history both for initial open or closed management of fractures and for definitive management.1 After the introduction of internal fixation constructs using nails or plates, external fixation largely transitioned from a means of definitive management to a temporizing measure taken before definitive internal fixation.

The Delta Frame external fixator (DePuy Synthes), which is used for significantly swollen ankle and pilon fractures, features anteromedially placed tibial shaft pins and a transcalcaneal pin. For distal tibia fractures that are not amenable to urgent internal fixation because of the degree of swelling or soft-tissue injury, it provides ligamentotaxis and traction for reduction of fracture fragments and stabilization.2

Numerous other external fixator configurations, such as knee-spanning or tibia-spanning external fixators, can be used for similar purposes. These stabilization methods are all minimally invasive and thus cause little trauma to the zone of injury3 and give soft-tissue injuries time to heal before definitive internal fixation.

Several different external fixator configurations can be used for a variety of fracture patterns and locations, but we propose using the external fixator as a starting point and adding proximal and distal attachments. These attachments have the potential to create more reduction force, and they provide more control of proximal and distal fracture fragments, continue to be minimally invasive, offer extrinsic grip power, are easily assembled and disassembled for intraoperative fracture reduction, and reduce the surgeon’s radiation exposure.

Materials and Methods

Our institution employs an external fixator system that is often used for high-energy lower extremity pathology. This system facilitates assembly of a Sweet T–Cherry II configuration. For periarticular ankle injuries, a Delta Frame external fixator is applied as described in the AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) surgical reference. Two diaphyseal Schanz pins are inserted into the tibia anterior to posterior based on the pin-placement guide and confirmed with fluoroscopy. These pins must be positioned close enough to the fracture site to provide stability, but not so close as to enter the zone of injury. A Denham pin is placed in the calcaneus medial to lateral. Care is taken to avoid the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle. Then, with use of pin-carbon fiber rod connectors, rods are attached so the Schanz pins connect with the Denham pin. In Sweet T–Cherry II assembly, a different rod configuration is used; rods are attached to the proximal-most Schanz pin and the Denham pin. In Sweet T assembly, a rod-rod connector is used to attach 2 carbon fiber rods to each other.

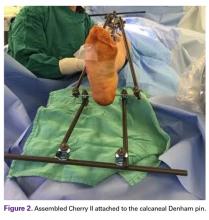

Next, in Cherry II assembly, 2 carbon fiber rods are attached to and locked to the Denham pin, one medial and the other lateral in an orientation orthogonal to the Denham pin extending distally. The Cherry II apparatus is completed with a third rod and is placed parallel to the Denham pin and orthogonal to the first 2 rods.

For knee-spanning external fixators, 2 Sweet T assemblies can be attached to the 2 Schanz pins. Furthermore, if 2 transverse pins are used for tibial external fixation, 2 Cherry II attachments can be used for multidirectional traction. An added benefit is extrinsic grip power, vs the intrinsic grip power provided with use of only the Schanz and Denham pins.

Results

The fully assembled apparatus provides a firm, well-fixed configuration for applying traction in multiple directions. Axial traction can be applied, as can anterior or posterior translation forces, which may be helpful in fracture reduction and joint dislocation. For difficult-to-reduce fractures or dislocations, the surgeon can apply multidirectional traction distally while the assistant applies countertraction proximally. Fracture reduction is confirmed with fluoroscopy, and the external fixator is locked in position to maintain reduction. After reduction is confirmed, Sweet T and Cherry II are easily removed. The end result is a reduced fracture or dislocation that has the typical appearance of the temporizing external fixator.

Discussion

The Sweet T–Cherry II configuration is assembled quickly and can aid the orthopedic surgeon and assistant in managing trauma cases involving difficult-to-reduce fractures. The principle is the same as in any other traction-countertraction model, though the materials required for assembly are already available to the surgeon, and additional equipment is not required. Furthermore, the large size of the attachments has the potential to offer more points of manipulation by the surgeon and assistant, when compared with Schanz and Denham pins alone. The configuration allows full extrinsic grip power as well (Figure 4), whereas only intrinsic hand power is allowed with traction applied through Schanz and Denham pins alone.

These attachments also have the potential to reduce surgeon and assistant radiation exposure. By positioning Sweet T and Cherry II proximally and distally, with the fluoroscopy machine over the zone of injury, the operators of the attachments increase their distance from the source of radiation. This strategic positioning decreases radiation exposure and reduces direct and scatter energy from the fluoroscopy machine and the patient.4 In addition, with the operators of the attachments farther from the zone of injury, the surgeon has a clear and direct view of the procedure, which may otherwise be obstructed with use of tensioning devices or conventional external fixator configurations. Sweet T and Cherry II attachments theoretically could be used for any configuration that uses proximal and distal fixation points. There is also the added benefit that these attachments are not restricted to applying traction axially but can also translate fracture fragments anteriorly, posteriorly, medially, or laterally, which has the potential to aid in reducing fractures and dislocations with varying degrees of translation, not only shortening. Although these attachments have mechanical counterparts, such as femoral distractors and other tensioning devices, the counterparts may take longer to assemble, apply, and activate. Sweet T and Cherry II attachments are included in the external fixator equipment and may generate more force and control while achieving reduction and stabilization similar to those achieved with other traction or tensioning devices. In addition, other tensioning devices may be cumbersome and unwieldy relative to Sweet T and Cherry II. For these attachments, research is needed on forces generated, time of assembly, and ease of use.

Conclusion

The Sweet T and Cherry II external fixator attachments have the potential to aid in managing difficult-to-reduce complex fractures and dislocations. These attachments are quickly assembled and may generate more force than does reduction with Schanz and Denham pins alone. The shape of these attachments may also provide a more comfortable and easier-to-manipulate base for application of traction in multiple directions. An added benefit is extrinsic grip power. Use of these attachments also has the potential to reduce operator radiation exposure and may provide an unobstructed view of the operative field, as the attachment operators are farther from the zone of injury. In addition, the materials used to assemble these attachments are included in almost all external fixation sets. More research comparing standard external fixator configurations with external fixator configurations using Sweet T and Cherry II attachments is needed.

1. Tejwani N, Polonet D, Wolinsky PR. External fixation of tibial fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(2):126-130.

2. Patterson MJ, Cole JD. Two-staged delayed open reduction and internal fixation of severe pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(2):85-91.

3. Bible JE, Mir HR. External fixation: principles and applications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(11):683-690.

4. Giordano BD, Ryder S, Baumhauer JF, DiGiovanni BF. Exposure to direct and scatter radiation with use of mini-c-arm fluoroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):948-952.

Take-Home Points

- External fixator attachments are fast and easy to assemble with existing external fixator equipment.

- They allow for multi-directional force application and use of extrinsic power grip.

- They limit radiation exposure and provides unobstructred line of sight to zone of injury.

- The attachments can then be removed once reduction is achieved.

External fixation has a long history both for initial open or closed management of fractures and for definitive management.1 After the introduction of internal fixation constructs using nails or plates, external fixation largely transitioned from a means of definitive management to a temporizing measure taken before definitive internal fixation.

The Delta Frame external fixator (DePuy Synthes), which is used for significantly swollen ankle and pilon fractures, features anteromedially placed tibial shaft pins and a transcalcaneal pin. For distal tibia fractures that are not amenable to urgent internal fixation because of the degree of swelling or soft-tissue injury, it provides ligamentotaxis and traction for reduction of fracture fragments and stabilization.2

Numerous other external fixator configurations, such as knee-spanning or tibia-spanning external fixators, can be used for similar purposes. These stabilization methods are all minimally invasive and thus cause little trauma to the zone of injury3 and give soft-tissue injuries time to heal before definitive internal fixation.

Several different external fixator configurations can be used for a variety of fracture patterns and locations, but we propose using the external fixator as a starting point and adding proximal and distal attachments. These attachments have the potential to create more reduction force, and they provide more control of proximal and distal fracture fragments, continue to be minimally invasive, offer extrinsic grip power, are easily assembled and disassembled for intraoperative fracture reduction, and reduce the surgeon’s radiation exposure.

Materials and Methods

Our institution employs an external fixator system that is often used for high-energy lower extremity pathology. This system facilitates assembly of a Sweet T–Cherry II configuration. For periarticular ankle injuries, a Delta Frame external fixator is applied as described in the AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) surgical reference. Two diaphyseal Schanz pins are inserted into the tibia anterior to posterior based on the pin-placement guide and confirmed with fluoroscopy. These pins must be positioned close enough to the fracture site to provide stability, but not so close as to enter the zone of injury. A Denham pin is placed in the calcaneus medial to lateral. Care is taken to avoid the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle. Then, with use of pin-carbon fiber rod connectors, rods are attached so the Schanz pins connect with the Denham pin. In Sweet T–Cherry II assembly, a different rod configuration is used; rods are attached to the proximal-most Schanz pin and the Denham pin. In Sweet T assembly, a rod-rod connector is used to attach 2 carbon fiber rods to each other.

Next, in Cherry II assembly, 2 carbon fiber rods are attached to and locked to the Denham pin, one medial and the other lateral in an orientation orthogonal to the Denham pin extending distally. The Cherry II apparatus is completed with a third rod and is placed parallel to the Denham pin and orthogonal to the first 2 rods.

For knee-spanning external fixators, 2 Sweet T assemblies can be attached to the 2 Schanz pins. Furthermore, if 2 transverse pins are used for tibial external fixation, 2 Cherry II attachments can be used for multidirectional traction. An added benefit is extrinsic grip power, vs the intrinsic grip power provided with use of only the Schanz and Denham pins.

Results

The fully assembled apparatus provides a firm, well-fixed configuration for applying traction in multiple directions. Axial traction can be applied, as can anterior or posterior translation forces, which may be helpful in fracture reduction and joint dislocation. For difficult-to-reduce fractures or dislocations, the surgeon can apply multidirectional traction distally while the assistant applies countertraction proximally. Fracture reduction is confirmed with fluoroscopy, and the external fixator is locked in position to maintain reduction. After reduction is confirmed, Sweet T and Cherry II are easily removed. The end result is a reduced fracture or dislocation that has the typical appearance of the temporizing external fixator.

Discussion

The Sweet T–Cherry II configuration is assembled quickly and can aid the orthopedic surgeon and assistant in managing trauma cases involving difficult-to-reduce fractures. The principle is the same as in any other traction-countertraction model, though the materials required for assembly are already available to the surgeon, and additional equipment is not required. Furthermore, the large size of the attachments has the potential to offer more points of manipulation by the surgeon and assistant, when compared with Schanz and Denham pins alone. The configuration allows full extrinsic grip power as well (Figure 4), whereas only intrinsic hand power is allowed with traction applied through Schanz and Denham pins alone.

These attachments also have the potential to reduce surgeon and assistant radiation exposure. By positioning Sweet T and Cherry II proximally and distally, with the fluoroscopy machine over the zone of injury, the operators of the attachments increase their distance from the source of radiation. This strategic positioning decreases radiation exposure and reduces direct and scatter energy from the fluoroscopy machine and the patient.4 In addition, with the operators of the attachments farther from the zone of injury, the surgeon has a clear and direct view of the procedure, which may otherwise be obstructed with use of tensioning devices or conventional external fixator configurations. Sweet T and Cherry II attachments theoretically could be used for any configuration that uses proximal and distal fixation points. There is also the added benefit that these attachments are not restricted to applying traction axially but can also translate fracture fragments anteriorly, posteriorly, medially, or laterally, which has the potential to aid in reducing fractures and dislocations with varying degrees of translation, not only shortening. Although these attachments have mechanical counterparts, such as femoral distractors and other tensioning devices, the counterparts may take longer to assemble, apply, and activate. Sweet T and Cherry II attachments are included in the external fixator equipment and may generate more force and control while achieving reduction and stabilization similar to those achieved with other traction or tensioning devices. In addition, other tensioning devices may be cumbersome and unwieldy relative to Sweet T and Cherry II. For these attachments, research is needed on forces generated, time of assembly, and ease of use.

Conclusion

The Sweet T and Cherry II external fixator attachments have the potential to aid in managing difficult-to-reduce complex fractures and dislocations. These attachments are quickly assembled and may generate more force than does reduction with Schanz and Denham pins alone. The shape of these attachments may also provide a more comfortable and easier-to-manipulate base for application of traction in multiple directions. An added benefit is extrinsic grip power. Use of these attachments also has the potential to reduce operator radiation exposure and may provide an unobstructed view of the operative field, as the attachment operators are farther from the zone of injury. In addition, the materials used to assemble these attachments are included in almost all external fixation sets. More research comparing standard external fixator configurations with external fixator configurations using Sweet T and Cherry II attachments is needed.

Take-Home Points

- External fixator attachments are fast and easy to assemble with existing external fixator equipment.

- They allow for multi-directional force application and use of extrinsic power grip.

- They limit radiation exposure and provides unobstructred line of sight to zone of injury.

- The attachments can then be removed once reduction is achieved.

External fixation has a long history both for initial open or closed management of fractures and for definitive management.1 After the introduction of internal fixation constructs using nails or plates, external fixation largely transitioned from a means of definitive management to a temporizing measure taken before definitive internal fixation.

The Delta Frame external fixator (DePuy Synthes), which is used for significantly swollen ankle and pilon fractures, features anteromedially placed tibial shaft pins and a transcalcaneal pin. For distal tibia fractures that are not amenable to urgent internal fixation because of the degree of swelling or soft-tissue injury, it provides ligamentotaxis and traction for reduction of fracture fragments and stabilization.2

Numerous other external fixator configurations, such as knee-spanning or tibia-spanning external fixators, can be used for similar purposes. These stabilization methods are all minimally invasive and thus cause little trauma to the zone of injury3 and give soft-tissue injuries time to heal before definitive internal fixation.

Several different external fixator configurations can be used for a variety of fracture patterns and locations, but we propose using the external fixator as a starting point and adding proximal and distal attachments. These attachments have the potential to create more reduction force, and they provide more control of proximal and distal fracture fragments, continue to be minimally invasive, offer extrinsic grip power, are easily assembled and disassembled for intraoperative fracture reduction, and reduce the surgeon’s radiation exposure.

Materials and Methods

Our institution employs an external fixator system that is often used for high-energy lower extremity pathology. This system facilitates assembly of a Sweet T–Cherry II configuration. For periarticular ankle injuries, a Delta Frame external fixator is applied as described in the AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) surgical reference. Two diaphyseal Schanz pins are inserted into the tibia anterior to posterior based on the pin-placement guide and confirmed with fluoroscopy. These pins must be positioned close enough to the fracture site to provide stability, but not so close as to enter the zone of injury. A Denham pin is placed in the calcaneus medial to lateral. Care is taken to avoid the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle. Then, with use of pin-carbon fiber rod connectors, rods are attached so the Schanz pins connect with the Denham pin. In Sweet T–Cherry II assembly, a different rod configuration is used; rods are attached to the proximal-most Schanz pin and the Denham pin. In Sweet T assembly, a rod-rod connector is used to attach 2 carbon fiber rods to each other.

Next, in Cherry II assembly, 2 carbon fiber rods are attached to and locked to the Denham pin, one medial and the other lateral in an orientation orthogonal to the Denham pin extending distally. The Cherry II apparatus is completed with a third rod and is placed parallel to the Denham pin and orthogonal to the first 2 rods.

For knee-spanning external fixators, 2 Sweet T assemblies can be attached to the 2 Schanz pins. Furthermore, if 2 transverse pins are used for tibial external fixation, 2 Cherry II attachments can be used for multidirectional traction. An added benefit is extrinsic grip power, vs the intrinsic grip power provided with use of only the Schanz and Denham pins.

Results

The fully assembled apparatus provides a firm, well-fixed configuration for applying traction in multiple directions. Axial traction can be applied, as can anterior or posterior translation forces, which may be helpful in fracture reduction and joint dislocation. For difficult-to-reduce fractures or dislocations, the surgeon can apply multidirectional traction distally while the assistant applies countertraction proximally. Fracture reduction is confirmed with fluoroscopy, and the external fixator is locked in position to maintain reduction. After reduction is confirmed, Sweet T and Cherry II are easily removed. The end result is a reduced fracture or dislocation that has the typical appearance of the temporizing external fixator.

Discussion

The Sweet T–Cherry II configuration is assembled quickly and can aid the orthopedic surgeon and assistant in managing trauma cases involving difficult-to-reduce fractures. The principle is the same as in any other traction-countertraction model, though the materials required for assembly are already available to the surgeon, and additional equipment is not required. Furthermore, the large size of the attachments has the potential to offer more points of manipulation by the surgeon and assistant, when compared with Schanz and Denham pins alone. The configuration allows full extrinsic grip power as well (Figure 4), whereas only intrinsic hand power is allowed with traction applied through Schanz and Denham pins alone.

These attachments also have the potential to reduce surgeon and assistant radiation exposure. By positioning Sweet T and Cherry II proximally and distally, with the fluoroscopy machine over the zone of injury, the operators of the attachments increase their distance from the source of radiation. This strategic positioning decreases radiation exposure and reduces direct and scatter energy from the fluoroscopy machine and the patient.4 In addition, with the operators of the attachments farther from the zone of injury, the surgeon has a clear and direct view of the procedure, which may otherwise be obstructed with use of tensioning devices or conventional external fixator configurations. Sweet T and Cherry II attachments theoretically could be used for any configuration that uses proximal and distal fixation points. There is also the added benefit that these attachments are not restricted to applying traction axially but can also translate fracture fragments anteriorly, posteriorly, medially, or laterally, which has the potential to aid in reducing fractures and dislocations with varying degrees of translation, not only shortening. Although these attachments have mechanical counterparts, such as femoral distractors and other tensioning devices, the counterparts may take longer to assemble, apply, and activate. Sweet T and Cherry II attachments are included in the external fixator equipment and may generate more force and control while achieving reduction and stabilization similar to those achieved with other traction or tensioning devices. In addition, other tensioning devices may be cumbersome and unwieldy relative to Sweet T and Cherry II. For these attachments, research is needed on forces generated, time of assembly, and ease of use.

Conclusion

The Sweet T and Cherry II external fixator attachments have the potential to aid in managing difficult-to-reduce complex fractures and dislocations. These attachments are quickly assembled and may generate more force than does reduction with Schanz and Denham pins alone. The shape of these attachments may also provide a more comfortable and easier-to-manipulate base for application of traction in multiple directions. An added benefit is extrinsic grip power. Use of these attachments also has the potential to reduce operator radiation exposure and may provide an unobstructed view of the operative field, as the attachment operators are farther from the zone of injury. In addition, the materials used to assemble these attachments are included in almost all external fixation sets. More research comparing standard external fixator configurations with external fixator configurations using Sweet T and Cherry II attachments is needed.

1. Tejwani N, Polonet D, Wolinsky PR. External fixation of tibial fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(2):126-130.

2. Patterson MJ, Cole JD. Two-staged delayed open reduction and internal fixation of severe pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(2):85-91.

3. Bible JE, Mir HR. External fixation: principles and applications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(11):683-690.

4. Giordano BD, Ryder S, Baumhauer JF, DiGiovanni BF. Exposure to direct and scatter radiation with use of mini-c-arm fluoroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):948-952.

1. Tejwani N, Polonet D, Wolinsky PR. External fixation of tibial fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(2):126-130.

2. Patterson MJ, Cole JD. Two-staged delayed open reduction and internal fixation of severe pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(2):85-91.

3. Bible JE, Mir HR. External fixation: principles and applications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(11):683-690.

4. Giordano BD, Ryder S, Baumhauer JF, DiGiovanni BF. Exposure to direct and scatter radiation with use of mini-c-arm fluoroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):948-952.

FDA approves cabozantinib for the frontline treatment of advanced RCC

The Food and Drug Administration has approved cabozantinib for the frontline treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

The drug was approved in 2016 for patients who had received prior antiangiogenic therapy.

The expanded approval was based on improvement in progression-free survival when compared with sunitinib in the phase 2 CABOSUN trial of 157 patients with previously untreated RCC, according to a statement from the company.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse reactions were reported in 68% of patients receiving cabozantinib, compared with 65% of patients receiving sunitinib. The most frequent adverse reactions in patients treated with cabozantinib were hypertension, diarrhea, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, fatigue, increased ALT, decreased appetite, stomatitis, pain, hypotension, and syncope. Approximately one-fifth of patients discontinued treatment in both arms.

Cabozantinib is marketed as Cabometyx by Exelixis.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved cabozantinib for the frontline treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

The drug was approved in 2016 for patients who had received prior antiangiogenic therapy.

The expanded approval was based on improvement in progression-free survival when compared with sunitinib in the phase 2 CABOSUN trial of 157 patients with previously untreated RCC, according to a statement from the company.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse reactions were reported in 68% of patients receiving cabozantinib, compared with 65% of patients receiving sunitinib. The most frequent adverse reactions in patients treated with cabozantinib were hypertension, diarrhea, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, fatigue, increased ALT, decreased appetite, stomatitis, pain, hypotension, and syncope. Approximately one-fifth of patients discontinued treatment in both arms.

Cabozantinib is marketed as Cabometyx by Exelixis.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved cabozantinib for the frontline treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

The drug was approved in 2016 for patients who had received prior antiangiogenic therapy.

The expanded approval was based on improvement in progression-free survival when compared with sunitinib in the phase 2 CABOSUN trial of 157 patients with previously untreated RCC, according to a statement from the company.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse reactions were reported in 68% of patients receiving cabozantinib, compared with 65% of patients receiving sunitinib. The most frequent adverse reactions in patients treated with cabozantinib were hypertension, diarrhea, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, fatigue, increased ALT, decreased appetite, stomatitis, pain, hypotension, and syncope. Approximately one-fifth of patients discontinued treatment in both arms.

Cabozantinib is marketed as Cabometyx by Exelixis.

Path CR signals good outcomes in treated high-risk breast cancers

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2017

SAN ANTONIO – Pathological complete response (pCR) is an accurate predictor of both event-free and distant recurrence-free survival in patients treated for stage 2 or 3 breast cancers with high risk for recurrence, according to investigators in the adaptive I-SPY2 trial.

Among 746 patients with various types of breast cancer evaluated in an intention-to-treat analysis, 3-year event-free survival (EFS) for those who had a pCR after chemotherapy and definitive surgery was 94%, compared with 76% for those who did not have a pCR.

Similarly, 3-year distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS) was 95% for patients who had a pCR after first-line therapy, compared with 79% for patients who did not, reported Douglas Yee, MD, of the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“We find that path CR is a strong predictor of event-free survival and distance recurrence-free survival in the setting of a multiagent platform trial,” he said at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

He explained that pCR is predictive of survival across all tumor subsets – regardless of hormone receptor status, HER2 status, and 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) status – and that pCR as a clinical trial endpoint allows investigators to rapidly evaluate novel therapeutic combinations, with the potential for identifying more effective and ideally less toxic regimens.

I-SPY 2 is a phase 2, adaptively randomized neoadjuvant clinical trial with a shared control arm in which patients receive standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and up to four simultaneous investigational arms. The primary endpoint is pCR, defined as no residual invasive cancer in the breast or lymph nodes, assessed according to the Residual Cancer Burden method. The goal is to match therapies with the most responsive breast cancer subtypes.

In the current analysis, the investigators looked at data on 245 patients with hormone receptor-negative and HER2– tumors (HR–/HER2–), 275 with HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors, 77 with HR–/HER2+ tumors, and 149 with tumors positive for both HR and HER2. Respective rates of pCR in these groups were 41%, 18%, 68% and 39%.

As noted, both EFS and DRFS were significantly better for patients with pCRs after initial therapy, with hazard ratios of 0.20 (P less than .001) for each comparison.

The predictive value of both EFS and DRFS held true for three of four subtypes studied, including triple-negative breast cancer (hazard ratios 0.17 and 0.16, P less than .001 for each), HR+/HER2– (HRs 0.21, P = .016 for EFS, and 0.22, P = .024 for DRFS), and HR–/HER2+ (HRs 0.10, and 0.14, P less than .001 for each).

However, among patients with HR+/HER2+ (triple-positive) breast cancers, EFS and DRFS rates were high for both patients with pCRs and those without, and the differences did not reach statistical significance. In these patients, the 3-year EFS rates were 96% for pCR and 87% for non pCR (HR, 0.26, P = .054), and the 3-year DRFS was 97% vs. 92% (HR, 0.19, P = 0.80).

“We believe that achieving path CR doing any therapy for any subtype is a sufficient endpoint,” Dr. Yee said. “Given that, we need to develop minimally-invasive techniques such as MRI and biopsy to identify path CR prior to definitive surgery. We need to validate robust MRI and tissue predictors of path CR, and if we can do that, we can begin to de-escalate toxic therapies,” he said.

The converse is also true: For patients who do not experience a path CR, MRI and tissue predictors could help to identify early in the course of therapy those patients who may need alternative treatments, he added.

“I think that this very clearly validates path CR as an incredibly powerful biomarker,” Eric P. Winer, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said in the question-and-response session following Dr. Yee’s presentation.

Dr. Winer emphasized, however, “that this does not mean that we can use path CR in comparing treatment A and treatment B in a randomized trial to determine that one is better in terms of long-term outcome.”

I-SPY2 is sponsored by the Quantum Leap Healthcare Collaborative, with funding support from the William K Bowes Foundation, Give Breast Cancer the Boot, University of California San Francisco, The Biomarkers consortium, Quintiles, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and Safeway. Dr. Yee reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Yee, D et al. SABCS Abstract GS3-08.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2017

SAN ANTONIO – Pathological complete response (pCR) is an accurate predictor of both event-free and distant recurrence-free survival in patients treated for stage 2 or 3 breast cancers with high risk for recurrence, according to investigators in the adaptive I-SPY2 trial.

Among 746 patients with various types of breast cancer evaluated in an intention-to-treat analysis, 3-year event-free survival (EFS) for those who had a pCR after chemotherapy and definitive surgery was 94%, compared with 76% for those who did not have a pCR.

Similarly, 3-year distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS) was 95% for patients who had a pCR after first-line therapy, compared with 79% for patients who did not, reported Douglas Yee, MD, of the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“We find that path CR is a strong predictor of event-free survival and distance recurrence-free survival in the setting of a multiagent platform trial,” he said at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

He explained that pCR is predictive of survival across all tumor subsets – regardless of hormone receptor status, HER2 status, and 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) status – and that pCR as a clinical trial endpoint allows investigators to rapidly evaluate novel therapeutic combinations, with the potential for identifying more effective and ideally less toxic regimens.

I-SPY 2 is a phase 2, adaptively randomized neoadjuvant clinical trial with a shared control arm in which patients receive standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and up to four simultaneous investigational arms. The primary endpoint is pCR, defined as no residual invasive cancer in the breast or lymph nodes, assessed according to the Residual Cancer Burden method. The goal is to match therapies with the most responsive breast cancer subtypes.

In the current analysis, the investigators looked at data on 245 patients with hormone receptor-negative and HER2– tumors (HR–/HER2–), 275 with HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors, 77 with HR–/HER2+ tumors, and 149 with tumors positive for both HR and HER2. Respective rates of pCR in these groups were 41%, 18%, 68% and 39%.

As noted, both EFS and DRFS were significantly better for patients with pCRs after initial therapy, with hazard ratios of 0.20 (P less than .001) for each comparison.

The predictive value of both EFS and DRFS held true for three of four subtypes studied, including triple-negative breast cancer (hazard ratios 0.17 and 0.16, P less than .001 for each), HR+/HER2– (HRs 0.21, P = .016 for EFS, and 0.22, P = .024 for DRFS), and HR–/HER2+ (HRs 0.10, and 0.14, P less than .001 for each).

However, among patients with HR+/HER2+ (triple-positive) breast cancers, EFS and DRFS rates were high for both patients with pCRs and those without, and the differences did not reach statistical significance. In these patients, the 3-year EFS rates were 96% for pCR and 87% for non pCR (HR, 0.26, P = .054), and the 3-year DRFS was 97% vs. 92% (HR, 0.19, P = 0.80).

“We believe that achieving path CR doing any therapy for any subtype is a sufficient endpoint,” Dr. Yee said. “Given that, we need to develop minimally-invasive techniques such as MRI and biopsy to identify path CR prior to definitive surgery. We need to validate robust MRI and tissue predictors of path CR, and if we can do that, we can begin to de-escalate toxic therapies,” he said.

The converse is also true: For patients who do not experience a path CR, MRI and tissue predictors could help to identify early in the course of therapy those patients who may need alternative treatments, he added.

“I think that this very clearly validates path CR as an incredibly powerful biomarker,” Eric P. Winer, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said in the question-and-response session following Dr. Yee’s presentation.

Dr. Winer emphasized, however, “that this does not mean that we can use path CR in comparing treatment A and treatment B in a randomized trial to determine that one is better in terms of long-term outcome.”

I-SPY2 is sponsored by the Quantum Leap Healthcare Collaborative, with funding support from the William K Bowes Foundation, Give Breast Cancer the Boot, University of California San Francisco, The Biomarkers consortium, Quintiles, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and Safeway. Dr. Yee reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Yee, D et al. SABCS Abstract GS3-08.

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2017

SAN ANTONIO – Pathological complete response (pCR) is an accurate predictor of both event-free and distant recurrence-free survival in patients treated for stage 2 or 3 breast cancers with high risk for recurrence, according to investigators in the adaptive I-SPY2 trial.

Among 746 patients with various types of breast cancer evaluated in an intention-to-treat analysis, 3-year event-free survival (EFS) for those who had a pCR after chemotherapy and definitive surgery was 94%, compared with 76% for those who did not have a pCR.

Similarly, 3-year distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS) was 95% for patients who had a pCR after first-line therapy, compared with 79% for patients who did not, reported Douglas Yee, MD, of the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“We find that path CR is a strong predictor of event-free survival and distance recurrence-free survival in the setting of a multiagent platform trial,” he said at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

He explained that pCR is predictive of survival across all tumor subsets – regardless of hormone receptor status, HER2 status, and 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) status – and that pCR as a clinical trial endpoint allows investigators to rapidly evaluate novel therapeutic combinations, with the potential for identifying more effective and ideally less toxic regimens.

I-SPY 2 is a phase 2, adaptively randomized neoadjuvant clinical trial with a shared control arm in which patients receive standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and up to four simultaneous investigational arms. The primary endpoint is pCR, defined as no residual invasive cancer in the breast or lymph nodes, assessed according to the Residual Cancer Burden method. The goal is to match therapies with the most responsive breast cancer subtypes.

In the current analysis, the investigators looked at data on 245 patients with hormone receptor-negative and HER2– tumors (HR–/HER2–), 275 with HR-positive/HER2-negative tumors, 77 with HR–/HER2+ tumors, and 149 with tumors positive for both HR and HER2. Respective rates of pCR in these groups were 41%, 18%, 68% and 39%.

As noted, both EFS and DRFS were significantly better for patients with pCRs after initial therapy, with hazard ratios of 0.20 (P less than .001) for each comparison.

The predictive value of both EFS and DRFS held true for three of four subtypes studied, including triple-negative breast cancer (hazard ratios 0.17 and 0.16, P less than .001 for each), HR+/HER2– (HRs 0.21, P = .016 for EFS, and 0.22, P = .024 for DRFS), and HR–/HER2+ (HRs 0.10, and 0.14, P less than .001 for each).

However, among patients with HR+/HER2+ (triple-positive) breast cancers, EFS and DRFS rates were high for both patients with pCRs and those without, and the differences did not reach statistical significance. In these patients, the 3-year EFS rates were 96% for pCR and 87% for non pCR (HR, 0.26, P = .054), and the 3-year DRFS was 97% vs. 92% (HR, 0.19, P = 0.80).

“We believe that achieving path CR doing any therapy for any subtype is a sufficient endpoint,” Dr. Yee said. “Given that, we need to develop minimally-invasive techniques such as MRI and biopsy to identify path CR prior to definitive surgery. We need to validate robust MRI and tissue predictors of path CR, and if we can do that, we can begin to de-escalate toxic therapies,” he said.

The converse is also true: For patients who do not experience a path CR, MRI and tissue predictors could help to identify early in the course of therapy those patients who may need alternative treatments, he added.

“I think that this very clearly validates path CR as an incredibly powerful biomarker,” Eric P. Winer, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said in the question-and-response session following Dr. Yee’s presentation.

Dr. Winer emphasized, however, “that this does not mean that we can use path CR in comparing treatment A and treatment B in a randomized trial to determine that one is better in terms of long-term outcome.”

I-SPY2 is sponsored by the Quantum Leap Healthcare Collaborative, with funding support from the William K Bowes Foundation, Give Breast Cancer the Boot, University of California San Francisco, The Biomarkers consortium, Quintiles, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and Safeway. Dr. Yee reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Yee, D et al. SABCS Abstract GS3-08.

Stereotactic Laser Ablation May Improve Cognitive Outcomes

MRI-guided stereotactic laser ablation (MRI-SLA) seems to offer advantages over more traditional open resection in patients requiring epileptic surgery, according to a recent review of the evidence.

- MRI-SLA has been found to improve several types of cognitive outcomes when compared to open surgery.

- Daniel Drane, MD, from Emory University points out that stereotactic laser ablation reduces collateral neurological damage.

- Stereotatic laser amygdalohippocampotomy may result in better neurological functioning in areas that include category related naming, verbal fluency, and object/familiar person recognition, when compared to traditional resection.

- The evidence suggests that using a neurosurgical technique like MRI-SLE offers advantages in patients undergoing epilepsy surgery by limiting the size of the surgical lesion zone.

Drane DL. MRI-Guided stereotactic laser ablation for epilepsy surgery: Promising preliminary results for cognitive outcome. [Published online ahead of print Sept 23, 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.016

MRI-guided stereotactic laser ablation (MRI-SLA) seems to offer advantages over more traditional open resection in patients requiring epileptic surgery, according to a recent review of the evidence.

- MRI-SLA has been found to improve several types of cognitive outcomes when compared to open surgery.

- Daniel Drane, MD, from Emory University points out that stereotactic laser ablation reduces collateral neurological damage.

- Stereotatic laser amygdalohippocampotomy may result in better neurological functioning in areas that include category related naming, verbal fluency, and object/familiar person recognition, when compared to traditional resection.

- The evidence suggests that using a neurosurgical technique like MRI-SLE offers advantages in patients undergoing epilepsy surgery by limiting the size of the surgical lesion zone.

Drane DL. MRI-Guided stereotactic laser ablation for epilepsy surgery: Promising preliminary results for cognitive outcome. [Published online ahead of print Sept 23, 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.016

MRI-guided stereotactic laser ablation (MRI-SLA) seems to offer advantages over more traditional open resection in patients requiring epileptic surgery, according to a recent review of the evidence.

- MRI-SLA has been found to improve several types of cognitive outcomes when compared to open surgery.

- Daniel Drane, MD, from Emory University points out that stereotactic laser ablation reduces collateral neurological damage.

- Stereotatic laser amygdalohippocampotomy may result in better neurological functioning in areas that include category related naming, verbal fluency, and object/familiar person recognition, when compared to traditional resection.

- The evidence suggests that using a neurosurgical technique like MRI-SLE offers advantages in patients undergoing epilepsy surgery by limiting the size of the surgical lesion zone.

Drane DL. MRI-Guided stereotactic laser ablation for epilepsy surgery: Promising preliminary results for cognitive outcome. [Published online ahead of print Sept 23, 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.016

The Value of Postsurgical Resting State Functional MRI

Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfMRI) may prove a valuable tool in evaluating patients with epilepsy postoperatively suggests this report from Epilepsy Research.

- Although task-based fMRI is often used to assess patients after surgery, Boerwinkle et al suggest resting state fMRI may be a useful adjunct and alternative after laser ablation of seizure foci, especially in pediatric patients.

- The researchers have developed software that can merge rsfMRI images with surgical navigation systems so that the technology can be more useful in a clinical setting.

- Boerwinkle et al postulate that performing rsfMRI after laser surgery may help clinicians detect changes in connectivity, determine the location of new seizure foci, and serve as a guide to determine the best course of antiepileptic therapy.

Boerwinkle VL, Vedantam A, Lam S et al. Connectivity changes after laser ablation: Resting-state fMRI. [Published online ahead of print Sept 28, 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.015

Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfMRI) may prove a valuable tool in evaluating patients with epilepsy postoperatively suggests this report from Epilepsy Research.

- Although task-based fMRI is often used to assess patients after surgery, Boerwinkle et al suggest resting state fMRI may be a useful adjunct and alternative after laser ablation of seizure foci, especially in pediatric patients.

- The researchers have developed software that can merge rsfMRI images with surgical navigation systems so that the technology can be more useful in a clinical setting.

- Boerwinkle et al postulate that performing rsfMRI after laser surgery may help clinicians detect changes in connectivity, determine the location of new seizure foci, and serve as a guide to determine the best course of antiepileptic therapy.

Boerwinkle VL, Vedantam A, Lam S et al. Connectivity changes after laser ablation: Resting-state fMRI. [Published online ahead of print Sept 28, 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.015

Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfMRI) may prove a valuable tool in evaluating patients with epilepsy postoperatively suggests this report from Epilepsy Research.

- Although task-based fMRI is often used to assess patients after surgery, Boerwinkle et al suggest resting state fMRI may be a useful adjunct and alternative after laser ablation of seizure foci, especially in pediatric patients.

- The researchers have developed software that can merge rsfMRI images with surgical navigation systems so that the technology can be more useful in a clinical setting.

- Boerwinkle et al postulate that performing rsfMRI after laser surgery may help clinicians detect changes in connectivity, determine the location of new seizure foci, and serve as a guide to determine the best course of antiepileptic therapy.

Boerwinkle VL, Vedantam A, Lam S et al. Connectivity changes after laser ablation: Resting-state fMRI. [Published online ahead of print Sept 28, 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.015

TLE Responds to Laser Interstitial Therapy

Magnetic resonance-guided stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy (SLAH) is emerging as a promising approach for patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy according to a recent review of the literature.

- Laser interstitial thermal therapy that is guided by MRI appears to be a safe, effective way to manage patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy—when used in properly selected patients.

- SLAH is less invasive than anterior temporal lobectomy and allows the surgeon to immediately destroy target tissue, which is not the case with radiosurgery.

- SLAH also has the advantage of allowing the surgeon to remove larger amounts of tissue than can be done with radiofrequency ablation.

- Bezchlibnyk et al state that MR-guided laser thermal therapy is less likely to cause neuropsychological deficits, when compared to open surgery.

Bezchlibnyk YB, Willie JT, Gross RE. A neurosurgeon`s view: Laser interstitial thermal therapy of mesial temporal lobe structures. [Published online ahead of print Oct 27 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.10.015

Magnetic resonance-guided stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy (SLAH) is emerging as a promising approach for patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy according to a recent review of the literature.

- Laser interstitial thermal therapy that is guided by MRI appears to be a safe, effective way to manage patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy—when used in properly selected patients.

- SLAH is less invasive than anterior temporal lobectomy and allows the surgeon to immediately destroy target tissue, which is not the case with radiosurgery.

- SLAH also has the advantage of allowing the surgeon to remove larger amounts of tissue than can be done with radiofrequency ablation.

- Bezchlibnyk et al state that MR-guided laser thermal therapy is less likely to cause neuropsychological deficits, when compared to open surgery.

Bezchlibnyk YB, Willie JT, Gross RE. A neurosurgeon`s view: Laser interstitial thermal therapy of mesial temporal lobe structures. [Published online ahead of print Oct 27 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.10.015

Magnetic resonance-guided stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy (SLAH) is emerging as a promising approach for patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy according to a recent review of the literature.

- Laser interstitial thermal therapy that is guided by MRI appears to be a safe, effective way to manage patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy—when used in properly selected patients.

- SLAH is less invasive than anterior temporal lobectomy and allows the surgeon to immediately destroy target tissue, which is not the case with radiosurgery.

- SLAH also has the advantage of allowing the surgeon to remove larger amounts of tissue than can be done with radiofrequency ablation.

- Bezchlibnyk et al state that MR-guided laser thermal therapy is less likely to cause neuropsychological deficits, when compared to open surgery.

Bezchlibnyk YB, Willie JT, Gross RE. A neurosurgeon`s view: Laser interstitial thermal therapy of mesial temporal lobe structures. [Published online ahead of print Oct 27 2017] Epilepsy Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.10.015

Cannabidiol linked to reduction in psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

Patients with schizophrenia showed signs of improvement in positive psychotic symptoms and clinician-rated improvement after treatment with cannabidiol, a component of cannabis thought to counteract the effects of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), an industry-funded phase 2 study reported.

According to the authors, the study is only the second to examine the use of cannabidiol in schizophrenia. “Because cannabidiol acts in a way different from conventional antipsychotic medication, it may represent a new class of treatment for schizophrenia,” wrote the study authors, including several employees of the drugmaker that helped to fund the research.

The study, led by Philip McGuire, FMedSci., of King’s College London, was published online Dec. 15 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Researchers have long been interested in the relationship between aspects of schizophrenia – especially psychosis – and cannabis. There’s been less focus on the effects of individual cannabinoids – components of cannabis such as THC (which is psychoactive), cannabinol (which is linked to sleep), and cannabidiol.

Researchers have linked cannabidiol to anxiety relief, and it’s been used to treat a wide variety of conditions, particularly epilepsy.

For the current study, a randomized, double-blind parallel-group trial, researchers assigned patients with schizophrenia or related psychotic disorders to receive 1,000 mg/day of cannabidiol (n = 43) or placebo (n = 45) for 6 weeks. The patients took the drug (10 mL of a 100-mg/mL oral solution) or a matching placebo twice a day in divided doses. They continued to take their existing antipsychotic medication; the study did not accept anyone taking more than one medication for that purpose.

The patients, aged 18-65, were at 15 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Romania, and Poland; 93% of the subjects were white, and 58% were male. The subjects were allowed to continue the use of alcohol or cannabis.

Eighty-three patients finished the trial after two withdrew because of adverse events and three withdrew consent. The intention-to-treat analysis involved 86 patients: 42 who took cannabidiol (including 3 who took it for 21 or fewer days) and 44 who took the placebo. At the end of treatment, the researchers found that the positive score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) fell from baseline by a mean –1.7 points in the placebo group and –3.2 points in the cannabidiol group, a difference of –1.4 points (P = .019). PANSS total and general scores also fell in both groups, as did the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms score, but the differences between the groups were not statistically significant. PANSS negative scores fell by about the same level in both groups.

At the end of treatment, clinicians were more likely to rate subjects in the cannabidiol group as improved on the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale (P = 0.018), compared with those in the placebo group.

About 35% of patients in both groups reported adverse events, including gastrointestinal problems (21% of those in the cannabidiol group and 6.7% of those in the placebo group). Researchers determined that just 10 patients in each group had treatment-related adverse events.

The mechanism of action of cannabidiol is unclear. Its effects “do not appear to depend on dopamine D2 receptor antagonism,” the investigators said. Theories about its mechanism of action include inhibition of the fatty acid amide hydrolase, inhibition of adenosine reuptake, TRPV1 and 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor agonism, and D2High partial agonism. “Because [cannabidiol] acts in a way different from conventional antipsychotic medication, it may represent a new class of treatment for schizophrenia,” the authors wrote.