User login

Enhanced recovery protocols after colectomy safely cut LOS

, at 15 hospitals in a pilot study of the Enhanced Recovery in National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Guidance from experts, engaged multidisciplinary team leadership, continuous data collection and auditing, and collaboration across institutions were all key to success. “The pilot may serve to inform future implementation efforts across hospitals varied in size, location, and resource availability,” investigators led by Julia R. Berian, MD, a surgery resident at the University of Chicago, wrote in a study published online in JAMA Surgery.

The program suggested 13 measures aimed at improved pain control, reduced gut dysfunction, and early nutrition and physical activity. Recommendations included shorter fluid fasts and better preop patient counseling; discontinuation of IV fluids and mobilization of patients within 24 hours of surgery; and solid diets within 24-48 hours.

The measures weren’t mandatory; each hospital tailored its protocols, and timing of implementation was at their discretion.

The report didn’t name the 15 hospitals, but they varied by size and academic status. Hospitals were selected for the program because they were outliers on elective colectomy LOS. The study ran during 2013-2015.

There were 3,437 colectomies at the hospitals before implementation, and 1,538 after. Results were compared with those of 9,950 colectomies over the study period at hospitals not involved in the efforts. Emergency and septic cases were excluded.

ERPs decreased mean LOS by 1.7 days, from 6.9 to 5.2 days. After taking patient characteristics and other matters into account, the adjusted decrease was 1.1 days. LOS fell by 0.4 days in the control hospitals (P less than .001).

Serious morbidity or mortality in the ERP hospitals decreased from 485 cases (14.1%) before implementation to 162 (10.5%) afterward (P less than .001); there was no change in the control hospitals. After implementation, serious morbidity or mortality was significantly less likely in ERP hospitals (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.96).

Meanwhile, there was no difference in readmission rates before and after implementation.

“The ERIN pilot study included hospitals of various sizes, indicating that both small and large hospitals can successfully decrease LOS with implementation of an ERP. ... Regardless of resource limitations, small hospitals may have the advantage of decreased bureaucracy and improved communication and collaboration across disciplines. ... We strongly believe that surgeon engagement and leadership in such initiatives are critical to sustained success,” the investigators wrote.

The ACS; Johns Hopkins’ Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Baltimore; and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have recently launched the “Improving Surgical Care and Recovery” program to provide more than 750 hospitals with tools, experts, and other resources for implementing ERPs. “The program is one opportunity for hospitals seeking implementation guidance,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Berian reported receiving salary support from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Her coinvestigators reported receiving grant or salary support from the foundation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One investigator reported relationships with a variety of drug and device companies.

SOURCE: Berian J et. al. JAMA Surg. 2017 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4906

, at 15 hospitals in a pilot study of the Enhanced Recovery in National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Guidance from experts, engaged multidisciplinary team leadership, continuous data collection and auditing, and collaboration across institutions were all key to success. “The pilot may serve to inform future implementation efforts across hospitals varied in size, location, and resource availability,” investigators led by Julia R. Berian, MD, a surgery resident at the University of Chicago, wrote in a study published online in JAMA Surgery.

The program suggested 13 measures aimed at improved pain control, reduced gut dysfunction, and early nutrition and physical activity. Recommendations included shorter fluid fasts and better preop patient counseling; discontinuation of IV fluids and mobilization of patients within 24 hours of surgery; and solid diets within 24-48 hours.

The measures weren’t mandatory; each hospital tailored its protocols, and timing of implementation was at their discretion.

The report didn’t name the 15 hospitals, but they varied by size and academic status. Hospitals were selected for the program because they were outliers on elective colectomy LOS. The study ran during 2013-2015.

There were 3,437 colectomies at the hospitals before implementation, and 1,538 after. Results were compared with those of 9,950 colectomies over the study period at hospitals not involved in the efforts. Emergency and septic cases were excluded.

ERPs decreased mean LOS by 1.7 days, from 6.9 to 5.2 days. After taking patient characteristics and other matters into account, the adjusted decrease was 1.1 days. LOS fell by 0.4 days in the control hospitals (P less than .001).

Serious morbidity or mortality in the ERP hospitals decreased from 485 cases (14.1%) before implementation to 162 (10.5%) afterward (P less than .001); there was no change in the control hospitals. After implementation, serious morbidity or mortality was significantly less likely in ERP hospitals (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.96).

Meanwhile, there was no difference in readmission rates before and after implementation.

“The ERIN pilot study included hospitals of various sizes, indicating that both small and large hospitals can successfully decrease LOS with implementation of an ERP. ... Regardless of resource limitations, small hospitals may have the advantage of decreased bureaucracy and improved communication and collaboration across disciplines. ... We strongly believe that surgeon engagement and leadership in such initiatives are critical to sustained success,” the investigators wrote.

The ACS; Johns Hopkins’ Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Baltimore; and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have recently launched the “Improving Surgical Care and Recovery” program to provide more than 750 hospitals with tools, experts, and other resources for implementing ERPs. “The program is one opportunity for hospitals seeking implementation guidance,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Berian reported receiving salary support from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Her coinvestigators reported receiving grant or salary support from the foundation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One investigator reported relationships with a variety of drug and device companies.

SOURCE: Berian J et. al. JAMA Surg. 2017 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4906

, at 15 hospitals in a pilot study of the Enhanced Recovery in National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Guidance from experts, engaged multidisciplinary team leadership, continuous data collection and auditing, and collaboration across institutions were all key to success. “The pilot may serve to inform future implementation efforts across hospitals varied in size, location, and resource availability,” investigators led by Julia R. Berian, MD, a surgery resident at the University of Chicago, wrote in a study published online in JAMA Surgery.

The program suggested 13 measures aimed at improved pain control, reduced gut dysfunction, and early nutrition and physical activity. Recommendations included shorter fluid fasts and better preop patient counseling; discontinuation of IV fluids and mobilization of patients within 24 hours of surgery; and solid diets within 24-48 hours.

The measures weren’t mandatory; each hospital tailored its protocols, and timing of implementation was at their discretion.

The report didn’t name the 15 hospitals, but they varied by size and academic status. Hospitals were selected for the program because they were outliers on elective colectomy LOS. The study ran during 2013-2015.

There were 3,437 colectomies at the hospitals before implementation, and 1,538 after. Results were compared with those of 9,950 colectomies over the study period at hospitals not involved in the efforts. Emergency and septic cases were excluded.

ERPs decreased mean LOS by 1.7 days, from 6.9 to 5.2 days. After taking patient characteristics and other matters into account, the adjusted decrease was 1.1 days. LOS fell by 0.4 days in the control hospitals (P less than .001).

Serious morbidity or mortality in the ERP hospitals decreased from 485 cases (14.1%) before implementation to 162 (10.5%) afterward (P less than .001); there was no change in the control hospitals. After implementation, serious morbidity or mortality was significantly less likely in ERP hospitals (adjusted odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.96).

Meanwhile, there was no difference in readmission rates before and after implementation.

“The ERIN pilot study included hospitals of various sizes, indicating that both small and large hospitals can successfully decrease LOS with implementation of an ERP. ... Regardless of resource limitations, small hospitals may have the advantage of decreased bureaucracy and improved communication and collaboration across disciplines. ... We strongly believe that surgeon engagement and leadership in such initiatives are critical to sustained success,” the investigators wrote.

The ACS; Johns Hopkins’ Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Baltimore; and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have recently launched the “Improving Surgical Care and Recovery” program to provide more than 750 hospitals with tools, experts, and other resources for implementing ERPs. “The program is one opportunity for hospitals seeking implementation guidance,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Berian reported receiving salary support from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Her coinvestigators reported receiving grant or salary support from the foundation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One investigator reported relationships with a variety of drug and device companies.

SOURCE: Berian J et. al. JAMA Surg. 2017 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4906

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: With the help of the Enhanced Recovery in National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, 15 hospitals enacted enhanced recovery protocols for elective colectomy that shortened length of stay and decreased complications, without increasing readmissions.

Major finding: After taking patient characteristics and other matters into account, the adjusted decrease in LOS was 1.1 days, versus 0.4 days in control hospitals (P less than .001).

Study details: The study compared 3,437 colectomies at 15 hospitals before ERP implementation to 1,538 after.

Disclosures: Dr. Berian reported receiving salary support from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Her coinvestigators reported receiving grant or salary support from the foundation and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. One investigator reported relationships with a variety of drug and device companies.

Source: Berian J et. al. JAMA Surg. 2017 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4906

Hospitalization risk twice as likely for veterans with mental illness

SAN DIEGO – compared with their peers who had no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis, according to results of a large VA database study.

“Our patients sit at the center of two public health crises,” David T. Moore, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting and scientific symposium of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. “One is the incredibly reduced life expectancy for adults with mental illnesses. There may be a 20-year reduced life expectancy. Their mortality rate for chronic medical conditions such as heart disease and COPD is increased by two- to fourfold, and is associated with greater hospitalization rates, longer lengths of stay, and increased readmission rates. The second part of this crisis is the incredible cost associated with medical hospitalizations. About 1 in every $20 in the entire U.S. economy goes toward inpatient medical hospitalization.”

The final analysis included 952,252 veterans with a mental illness and 1,064,140 without a psychiatric or addiction diagnosis. Dr. Moore reported that among veterans with mental illness, 100,191 (7.1%) were hospitalized on a medical unit at some point during the study period, compared with only 31,759 (2.9%) of veterans with no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was significantly increased in veterans with mental health diagnoses, compared with those who did not have mental health diagnoses.

“There was more tobacco use; they were much more likely to receive an opioid prescription; [and] they used more outpatient medical services, whether it be primary care visits or specialty care visits,” Dr. Moore said of the hospitalized veterans. “They are sicker, but they also use more outpatient medical services, suggesting that they do not lack access to adequate outpatient medical care.”

Next, the researchers performed a subset analysis of all veterans with any mental health diagnosis. Compared with those who were not hospitalized during the study period, those hospitalized were older (a mean age of 52 vs. 45 years, respectively), more likely to be homeless (21% vs. 12%; relative risk, 1.8), and receive a VA pension, which is correlated with poor functioning and disability (7.1% vs. 2.9%; RR, 2.4). The only psychiatric disorder correlated with correlated with medical hospitalization was personality disorder (6.3% vs. 3.7%; RR, 1.7). The researchers also observed that a higher proportion of hospitalized patients had an alcohol use disorder (34% vs. 23%; RR, 1.7) and drug use (31% vs. 17%; RR, 1.8). “The use of benzodiazepines had the greatest relative risk for medical hospitalizations,” Dr. Moore said.

In unadjusted analyses, veterans with the following diagnoses were at increased risk for hospitalization: drug use disorder (odds ratio, 4.58), alcohol use disorder (OR, 3.84), bipolar disorder (OR, 3.29), major depressive disorder (OR, 3.04), schizophrenia (OR, 2.98), and posttraumatic stress disorder (OR, 1.91).

After adjusting for other health factors in multiple regression, alcohol use disorder was the only psychiatric or addiction disorder strongly associated with medical hospitalizations (OR, 1.95). After accounting for sociodemographic characteristics, medical comorbidities, use of outpatient medical services, and alcohol use, the OR for medical hospitalizations among veterans with mental illness decreased from 2.52 to 1.24.

“It looks like a lot of the folks with drug use disorders who are being hospitalized may also have co-occurring alcohol use disorders,” Dr. Moore said. “That may partly account for their hospitalization risk.”

He concluded that the study’s overall findings “leave us with a lot of questions about what to do. The majority of patients who are hospitalized have a mental illness. Is this a setting where we should be engaging them and trying to connect them with outpatient services?”

Dr. Moore reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Moore et al. AAAP 2017. Paper session A1.

SAN DIEGO – compared with their peers who had no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis, according to results of a large VA database study.

“Our patients sit at the center of two public health crises,” David T. Moore, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting and scientific symposium of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. “One is the incredibly reduced life expectancy for adults with mental illnesses. There may be a 20-year reduced life expectancy. Their mortality rate for chronic medical conditions such as heart disease and COPD is increased by two- to fourfold, and is associated with greater hospitalization rates, longer lengths of stay, and increased readmission rates. The second part of this crisis is the incredible cost associated with medical hospitalizations. About 1 in every $20 in the entire U.S. economy goes toward inpatient medical hospitalization.”

The final analysis included 952,252 veterans with a mental illness and 1,064,140 without a psychiatric or addiction diagnosis. Dr. Moore reported that among veterans with mental illness, 100,191 (7.1%) were hospitalized on a medical unit at some point during the study period, compared with only 31,759 (2.9%) of veterans with no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was significantly increased in veterans with mental health diagnoses, compared with those who did not have mental health diagnoses.

“There was more tobacco use; they were much more likely to receive an opioid prescription; [and] they used more outpatient medical services, whether it be primary care visits or specialty care visits,” Dr. Moore said of the hospitalized veterans. “They are sicker, but they also use more outpatient medical services, suggesting that they do not lack access to adequate outpatient medical care.”

Next, the researchers performed a subset analysis of all veterans with any mental health diagnosis. Compared with those who were not hospitalized during the study period, those hospitalized were older (a mean age of 52 vs. 45 years, respectively), more likely to be homeless (21% vs. 12%; relative risk, 1.8), and receive a VA pension, which is correlated with poor functioning and disability (7.1% vs. 2.9%; RR, 2.4). The only psychiatric disorder correlated with correlated with medical hospitalization was personality disorder (6.3% vs. 3.7%; RR, 1.7). The researchers also observed that a higher proportion of hospitalized patients had an alcohol use disorder (34% vs. 23%; RR, 1.7) and drug use (31% vs. 17%; RR, 1.8). “The use of benzodiazepines had the greatest relative risk for medical hospitalizations,” Dr. Moore said.

In unadjusted analyses, veterans with the following diagnoses were at increased risk for hospitalization: drug use disorder (odds ratio, 4.58), alcohol use disorder (OR, 3.84), bipolar disorder (OR, 3.29), major depressive disorder (OR, 3.04), schizophrenia (OR, 2.98), and posttraumatic stress disorder (OR, 1.91).

After adjusting for other health factors in multiple regression, alcohol use disorder was the only psychiatric or addiction disorder strongly associated with medical hospitalizations (OR, 1.95). After accounting for sociodemographic characteristics, medical comorbidities, use of outpatient medical services, and alcohol use, the OR for medical hospitalizations among veterans with mental illness decreased from 2.52 to 1.24.

“It looks like a lot of the folks with drug use disorders who are being hospitalized may also have co-occurring alcohol use disorders,” Dr. Moore said. “That may partly account for their hospitalization risk.”

He concluded that the study’s overall findings “leave us with a lot of questions about what to do. The majority of patients who are hospitalized have a mental illness. Is this a setting where we should be engaging them and trying to connect them with outpatient services?”

Dr. Moore reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Moore et al. AAAP 2017. Paper session A1.

SAN DIEGO – compared with their peers who had no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis, according to results of a large VA database study.

“Our patients sit at the center of two public health crises,” David T. Moore, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting and scientific symposium of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. “One is the incredibly reduced life expectancy for adults with mental illnesses. There may be a 20-year reduced life expectancy. Their mortality rate for chronic medical conditions such as heart disease and COPD is increased by two- to fourfold, and is associated with greater hospitalization rates, longer lengths of stay, and increased readmission rates. The second part of this crisis is the incredible cost associated with medical hospitalizations. About 1 in every $20 in the entire U.S. economy goes toward inpatient medical hospitalization.”

The final analysis included 952,252 veterans with a mental illness and 1,064,140 without a psychiatric or addiction diagnosis. Dr. Moore reported that among veterans with mental illness, 100,191 (7.1%) were hospitalized on a medical unit at some point during the study period, compared with only 31,759 (2.9%) of veterans with no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was significantly increased in veterans with mental health diagnoses, compared with those who did not have mental health diagnoses.

“There was more tobacco use; they were much more likely to receive an opioid prescription; [and] they used more outpatient medical services, whether it be primary care visits or specialty care visits,” Dr. Moore said of the hospitalized veterans. “They are sicker, but they also use more outpatient medical services, suggesting that they do not lack access to adequate outpatient medical care.”

Next, the researchers performed a subset analysis of all veterans with any mental health diagnosis. Compared with those who were not hospitalized during the study period, those hospitalized were older (a mean age of 52 vs. 45 years, respectively), more likely to be homeless (21% vs. 12%; relative risk, 1.8), and receive a VA pension, which is correlated with poor functioning and disability (7.1% vs. 2.9%; RR, 2.4). The only psychiatric disorder correlated with correlated with medical hospitalization was personality disorder (6.3% vs. 3.7%; RR, 1.7). The researchers also observed that a higher proportion of hospitalized patients had an alcohol use disorder (34% vs. 23%; RR, 1.7) and drug use (31% vs. 17%; RR, 1.8). “The use of benzodiazepines had the greatest relative risk for medical hospitalizations,” Dr. Moore said.

In unadjusted analyses, veterans with the following diagnoses were at increased risk for hospitalization: drug use disorder (odds ratio, 4.58), alcohol use disorder (OR, 3.84), bipolar disorder (OR, 3.29), major depressive disorder (OR, 3.04), schizophrenia (OR, 2.98), and posttraumatic stress disorder (OR, 1.91).

After adjusting for other health factors in multiple regression, alcohol use disorder was the only psychiatric or addiction disorder strongly associated with medical hospitalizations (OR, 1.95). After accounting for sociodemographic characteristics, medical comorbidities, use of outpatient medical services, and alcohol use, the OR for medical hospitalizations among veterans with mental illness decreased from 2.52 to 1.24.

“It looks like a lot of the folks with drug use disorders who are being hospitalized may also have co-occurring alcohol use disorders,” Dr. Moore said. “That may partly account for their hospitalization risk.”

He concluded that the study’s overall findings “leave us with a lot of questions about what to do. The majority of patients who are hospitalized have a mental illness. Is this a setting where we should be engaging them and trying to connect them with outpatient services?”

Dr. Moore reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Moore et al. AAAP 2017. Paper session A1.

REPORTING FROM AAAP

Key clinical point: In order to improve the health of veterans with mental illness, more efforts are needed to target alcohol use.

Major finding: Among veterans with mental illnesses, 7.1% were hospitalized, compared with 2.9% of their peers with no psychiatric or addiction diagnosis.

Study details: A database analysis of 952,252 veterans with a mental illness and 1,064,140 without a psychiatric or addiction diagnosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Moore reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Moore et al. AAAP 2017. Paper session A1.

Palliative care underutilized in dementia patients with acute abdomen

Despite high rates of in-hospital mortality and nonroutine discharge, palliative care is underutilized in patients with dementia and acute abdominal emergency, according to findings published in Surgery.

“Currently little is known about palliative care utilization among patients with dementia in possible need of surgical intervention. This raises the question of whether the acute surgical emergency represents an appropriate episode during which to introduce palliative care for patients with dementia,” wrote Ana Berlin, MD, FACS, of the department of surgery at New Jersey Medical School, Newark, N.J., and her coauthors (Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048).

Of 15,209 patients aged 50 years and older with dementia and acute abdomen, 7.5% received palliative care. Patients discharged nonroutinely and patients treated operatively were less likely to receive palliative care, the researchers reported.

Dr. Berlin and her colleagues used the National Inpatient Sample database to identify patients with dementia and acute abdomen who were admitted nonelectively between 2009 and 2013. They used ICD-9 primary and secondary codes to limit surgical diagnoses to gastrointestinal obstruction, ischemia, and perforation.

Overall, 50.9% of patients were admitted for gastrointestinal obstruction, 39.8% for perforation, 5.1% for bowel ischemia, and 4.3% for mixed pathology; 17.8% of patients were managed operatively.

Patients with intestinal ischemia had the highest rate of both operation and mortality, at 22.8% and 27.6%, respectively. These patients also had the lowest rate of routine discharge, at 15.9%, the authors said. In comparison, patients with obstruction had surgical intervention and in-hospital mortality rates of 17% and 10.1%, respectively, and a routine discharge rate of 20.9%. Patients with perforation had an operation rate of 13.8%, in-hospital mortality rate of 6.8%, and routine discharge rate of 26.9%.

The palliative care utilization rate overall was 7.5%. Patients with mixed pathology who did not have surgery were most likely to receive palliative care, at 21.1%, noted Dr. Berlin and her coauthors.

Patients who died postoperatively were less likely than were those who died without surgical intervention to have received palliative care (20.9% vs. 31.4%; odds ratio = 0.63, 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.86; P = .0039), and those who were discharged nonroutinely after an operation were less likely than were patients who were discharged nonroutinely without an operation to receive palliative care (3.7% vs. 7.0%; OR = 0.44, 95% CI, 0.34-0.57; P less than .0001).

Lastly, patients who received palliative care had shorter median hospital stays than did those who did not receive palliative care (5 days vs. 6 days; P less than .0001). These patients also had lower median hospital charges ($29,500 vs. $31,600; P = .0403).

The results identify two subsets of patients with unmet palliative care needs: patients requiring operative intervention, and patients with a diagnosis of intestinal ischemia, the authors said. In addition, the findings suggest that “surgeons should consider initiating palliative care … early in the hospital course for patients with dementia presenting with acute surgical abdomen,” they wrote.

“Both hip fracture and intensive care unit admission in patients with dementia have been described as appropriate triggers for palliative care assessment. ... Acute abdominal emergency [may also represent] an appropriate episode during which to introduce palliative care for patients with dementia,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School department of surgery and the New Jersey Medical School Hispanic Center of Excellence, Health Resources, and Services Administration. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048.

Few surgeons would argue that a patient with dementia and an acute abdomen would be less appropriate for a palliative care consultation than demented patients with a hip fracture or ICU admission who have been shown to benefit from triggered palliative care consults. However, the dynamic interaction between patient, family, and surgeon, described by Thomas Miner as the “palliative triangle,” will likely prevent universal acceptance of triggered consults (Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9[7]:696-709). Despite the current trend of increasingly algorithmic care, there is still a need for surgeon autonomy for treatment decisions even when the recommended triggered intervention is highly appropriate. A mentor of mine put it, “I never do things routinely, but there are some things I do all the time.” As the benefits of palliative care become more evident, the referrals for palliative care for this latest indication will become “some things I do all the time” just as pharmacokinetics referrals have become for antibiotics, anticoagulation, and total parenteral nutrition.

Few surgeons would argue that a patient with dementia and an acute abdomen would be less appropriate for a palliative care consultation than demented patients with a hip fracture or ICU admission who have been shown to benefit from triggered palliative care consults. However, the dynamic interaction between patient, family, and surgeon, described by Thomas Miner as the “palliative triangle,” will likely prevent universal acceptance of triggered consults (Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9[7]:696-709). Despite the current trend of increasingly algorithmic care, there is still a need for surgeon autonomy for treatment decisions even when the recommended triggered intervention is highly appropriate. A mentor of mine put it, “I never do things routinely, but there are some things I do all the time.” As the benefits of palliative care become more evident, the referrals for palliative care for this latest indication will become “some things I do all the time” just as pharmacokinetics referrals have become for antibiotics, anticoagulation, and total parenteral nutrition.

Few surgeons would argue that a patient with dementia and an acute abdomen would be less appropriate for a palliative care consultation than demented patients with a hip fracture or ICU admission who have been shown to benefit from triggered palliative care consults. However, the dynamic interaction between patient, family, and surgeon, described by Thomas Miner as the “palliative triangle,” will likely prevent universal acceptance of triggered consults (Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9[7]:696-709). Despite the current trend of increasingly algorithmic care, there is still a need for surgeon autonomy for treatment decisions even when the recommended triggered intervention is highly appropriate. A mentor of mine put it, “I never do things routinely, but there are some things I do all the time.” As the benefits of palliative care become more evident, the referrals for palliative care for this latest indication will become “some things I do all the time” just as pharmacokinetics referrals have become for antibiotics, anticoagulation, and total parenteral nutrition.

Despite high rates of in-hospital mortality and nonroutine discharge, palliative care is underutilized in patients with dementia and acute abdominal emergency, according to findings published in Surgery.

“Currently little is known about palliative care utilization among patients with dementia in possible need of surgical intervention. This raises the question of whether the acute surgical emergency represents an appropriate episode during which to introduce palliative care for patients with dementia,” wrote Ana Berlin, MD, FACS, of the department of surgery at New Jersey Medical School, Newark, N.J., and her coauthors (Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048).

Of 15,209 patients aged 50 years and older with dementia and acute abdomen, 7.5% received palliative care. Patients discharged nonroutinely and patients treated operatively were less likely to receive palliative care, the researchers reported.

Dr. Berlin and her colleagues used the National Inpatient Sample database to identify patients with dementia and acute abdomen who were admitted nonelectively between 2009 and 2013. They used ICD-9 primary and secondary codes to limit surgical diagnoses to gastrointestinal obstruction, ischemia, and perforation.

Overall, 50.9% of patients were admitted for gastrointestinal obstruction, 39.8% for perforation, 5.1% for bowel ischemia, and 4.3% for mixed pathology; 17.8% of patients were managed operatively.

Patients with intestinal ischemia had the highest rate of both operation and mortality, at 22.8% and 27.6%, respectively. These patients also had the lowest rate of routine discharge, at 15.9%, the authors said. In comparison, patients with obstruction had surgical intervention and in-hospital mortality rates of 17% and 10.1%, respectively, and a routine discharge rate of 20.9%. Patients with perforation had an operation rate of 13.8%, in-hospital mortality rate of 6.8%, and routine discharge rate of 26.9%.

The palliative care utilization rate overall was 7.5%. Patients with mixed pathology who did not have surgery were most likely to receive palliative care, at 21.1%, noted Dr. Berlin and her coauthors.

Patients who died postoperatively were less likely than were those who died without surgical intervention to have received palliative care (20.9% vs. 31.4%; odds ratio = 0.63, 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.86; P = .0039), and those who were discharged nonroutinely after an operation were less likely than were patients who were discharged nonroutinely without an operation to receive palliative care (3.7% vs. 7.0%; OR = 0.44, 95% CI, 0.34-0.57; P less than .0001).

Lastly, patients who received palliative care had shorter median hospital stays than did those who did not receive palliative care (5 days vs. 6 days; P less than .0001). These patients also had lower median hospital charges ($29,500 vs. $31,600; P = .0403).

The results identify two subsets of patients with unmet palliative care needs: patients requiring operative intervention, and patients with a diagnosis of intestinal ischemia, the authors said. In addition, the findings suggest that “surgeons should consider initiating palliative care … early in the hospital course for patients with dementia presenting with acute surgical abdomen,” they wrote.

“Both hip fracture and intensive care unit admission in patients with dementia have been described as appropriate triggers for palliative care assessment. ... Acute abdominal emergency [may also represent] an appropriate episode during which to introduce palliative care for patients with dementia,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School department of surgery and the New Jersey Medical School Hispanic Center of Excellence, Health Resources, and Services Administration. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048.

Despite high rates of in-hospital mortality and nonroutine discharge, palliative care is underutilized in patients with dementia and acute abdominal emergency, according to findings published in Surgery.

“Currently little is known about palliative care utilization among patients with dementia in possible need of surgical intervention. This raises the question of whether the acute surgical emergency represents an appropriate episode during which to introduce palliative care for patients with dementia,” wrote Ana Berlin, MD, FACS, of the department of surgery at New Jersey Medical School, Newark, N.J., and her coauthors (Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048).

Of 15,209 patients aged 50 years and older with dementia and acute abdomen, 7.5% received palliative care. Patients discharged nonroutinely and patients treated operatively were less likely to receive palliative care, the researchers reported.

Dr. Berlin and her colleagues used the National Inpatient Sample database to identify patients with dementia and acute abdomen who were admitted nonelectively between 2009 and 2013. They used ICD-9 primary and secondary codes to limit surgical diagnoses to gastrointestinal obstruction, ischemia, and perforation.

Overall, 50.9% of patients were admitted for gastrointestinal obstruction, 39.8% for perforation, 5.1% for bowel ischemia, and 4.3% for mixed pathology; 17.8% of patients were managed operatively.

Patients with intestinal ischemia had the highest rate of both operation and mortality, at 22.8% and 27.6%, respectively. These patients also had the lowest rate of routine discharge, at 15.9%, the authors said. In comparison, patients with obstruction had surgical intervention and in-hospital mortality rates of 17% and 10.1%, respectively, and a routine discharge rate of 20.9%. Patients with perforation had an operation rate of 13.8%, in-hospital mortality rate of 6.8%, and routine discharge rate of 26.9%.

The palliative care utilization rate overall was 7.5%. Patients with mixed pathology who did not have surgery were most likely to receive palliative care, at 21.1%, noted Dr. Berlin and her coauthors.

Patients who died postoperatively were less likely than were those who died without surgical intervention to have received palliative care (20.9% vs. 31.4%; odds ratio = 0.63, 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.86; P = .0039), and those who were discharged nonroutinely after an operation were less likely than were patients who were discharged nonroutinely without an operation to receive palliative care (3.7% vs. 7.0%; OR = 0.44, 95% CI, 0.34-0.57; P less than .0001).

Lastly, patients who received palliative care had shorter median hospital stays than did those who did not receive palliative care (5 days vs. 6 days; P less than .0001). These patients also had lower median hospital charges ($29,500 vs. $31,600; P = .0403).

The results identify two subsets of patients with unmet palliative care needs: patients requiring operative intervention, and patients with a diagnosis of intestinal ischemia, the authors said. In addition, the findings suggest that “surgeons should consider initiating palliative care … early in the hospital course for patients with dementia presenting with acute surgical abdomen,” they wrote.

“Both hip fracture and intensive care unit admission in patients with dementia have been described as appropriate triggers for palliative care assessment. ... Acute abdominal emergency [may also represent] an appropriate episode during which to introduce palliative care for patients with dementia,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School department of surgery and the New Jersey Medical School Hispanic Center of Excellence, Health Resources, and Services Administration. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048.

FROM SURGERY

Key clinical point: Despite high mortality and frequent nonroutine discharges, palliative care is underutilized in dementia patients with acute abdominal emergency.

Major finding: Among dementia patients with acute abdominal emergency, 7.5% received palliative care.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 15,209 patients aged 50 years and older from the National Inpatient Sample, for the period of 2009-2013.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School Department of Surgery and the New Jersey Medical School Hispanic Center of Excellence, Health Resources, and Services Administration.

SOURCE: Surgery. 2017 Dec 4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.09.048.

Contraceptive use appears low in teen girls on teratogenic medications

SAN DIEGO – A majority of U.S. teenage girls on Medicaid who were prescribed teratogenic medications for rheumatic diseases did not receive or fill prescriptions for contraception, and some became pregnant while taking the medication, a study showed.

The analysis of a Medicaid database of paid claims from 12 unidentified U.S. states during 2013-2015 found a pregnancy rate of 7.6% in 4,853 females aged 15-19 who were prescribed at least one of eight teratogenic medications, mostly labeled as category D or X: cyclophosphamide, enalapril, leflunomide, lisinopril, losartan, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and cyclosporine (category C). This rate varied from 2.2% in 15-year-olds to 13.6% in 19-year-olds.

The number of filled prescriptions for contraception was low despite the associated risk of the teratogenic medications, said Dr. Hays, a third-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

“Each teratogenic medication carries a different risk,” she said. “Certain teratogenic medications carry a greater risk than other teratogenic medications. The associated risk may vary based on the timing and duration of use.”

“The risks and benefits of using a teratogenic medication for treatment should be discussed with teens and women of reproductive age,” Dr. Hays said. “Disease activity should be low, and the teratogenic medication should be replaced with a safer medication prior to pregnancy if one is available. Highly effective forms of contraception should be offered to patients who are at risk for unintended pregnancy and those who are not trying to conceive.”

In addition to rheumatic diseases, the eight teratogenic medications cited in the study are used to treat other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, kidney disease, and malignancy, Dr. Hays said.

The study population was made up of 45.0% whites, 36.6% blacks, 4.8% Hispanics, and 13.6% others.

About 10% were defined as having a specific rheumatic disease, mainly systemic lupus erythematosus (70%), Dr. Hays said. “However, more than 10% had a rheumatic condition of some kind. Generalizations in ICD-9 coding made it difficult to identify specific diseases in some cases.”

The study did not examine birth defect outcomes in the babies born to the females in the cohort, but Dr. Hays said researchers are considering whether to track these numbers via claims data. The study also was not able to capture the use of nonprescribed contraception, such as condoms.

Moving forward, Dr. Hays said the researchers “are planning to also look at pregnancy and contraception rates in age-matched teens not taking teratogenic medications using the same Medicaid claims database. We are also hoping to research patient and provider perspectives pertaining to teratogenic medication use/risk and contraception.”

In addition, researchers hope to examine how commonly the individual drugs were prescribed and link them to contraception use and pregnancy, she said.

The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures, and the study had no external funding. The Medical University of South Carolina provided funding for database access.

SOURCE: Hays K et al. ACR 2017 Abstract 1813.

SAN DIEGO – A majority of U.S. teenage girls on Medicaid who were prescribed teratogenic medications for rheumatic diseases did not receive or fill prescriptions for contraception, and some became pregnant while taking the medication, a study showed.

The analysis of a Medicaid database of paid claims from 12 unidentified U.S. states during 2013-2015 found a pregnancy rate of 7.6% in 4,853 females aged 15-19 who were prescribed at least one of eight teratogenic medications, mostly labeled as category D or X: cyclophosphamide, enalapril, leflunomide, lisinopril, losartan, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and cyclosporine (category C). This rate varied from 2.2% in 15-year-olds to 13.6% in 19-year-olds.

The number of filled prescriptions for contraception was low despite the associated risk of the teratogenic medications, said Dr. Hays, a third-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

“Each teratogenic medication carries a different risk,” she said. “Certain teratogenic medications carry a greater risk than other teratogenic medications. The associated risk may vary based on the timing and duration of use.”

“The risks and benefits of using a teratogenic medication for treatment should be discussed with teens and women of reproductive age,” Dr. Hays said. “Disease activity should be low, and the teratogenic medication should be replaced with a safer medication prior to pregnancy if one is available. Highly effective forms of contraception should be offered to patients who are at risk for unintended pregnancy and those who are not trying to conceive.”

In addition to rheumatic diseases, the eight teratogenic medications cited in the study are used to treat other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, kidney disease, and malignancy, Dr. Hays said.

The study population was made up of 45.0% whites, 36.6% blacks, 4.8% Hispanics, and 13.6% others.

About 10% were defined as having a specific rheumatic disease, mainly systemic lupus erythematosus (70%), Dr. Hays said. “However, more than 10% had a rheumatic condition of some kind. Generalizations in ICD-9 coding made it difficult to identify specific diseases in some cases.”

The study did not examine birth defect outcomes in the babies born to the females in the cohort, but Dr. Hays said researchers are considering whether to track these numbers via claims data. The study also was not able to capture the use of nonprescribed contraception, such as condoms.

Moving forward, Dr. Hays said the researchers “are planning to also look at pregnancy and contraception rates in age-matched teens not taking teratogenic medications using the same Medicaid claims database. We are also hoping to research patient and provider perspectives pertaining to teratogenic medication use/risk and contraception.”

In addition, researchers hope to examine how commonly the individual drugs were prescribed and link them to contraception use and pregnancy, she said.

The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures, and the study had no external funding. The Medical University of South Carolina provided funding for database access.

SOURCE: Hays K et al. ACR 2017 Abstract 1813.

SAN DIEGO – A majority of U.S. teenage girls on Medicaid who were prescribed teratogenic medications for rheumatic diseases did not receive or fill prescriptions for contraception, and some became pregnant while taking the medication, a study showed.

The analysis of a Medicaid database of paid claims from 12 unidentified U.S. states during 2013-2015 found a pregnancy rate of 7.6% in 4,853 females aged 15-19 who were prescribed at least one of eight teratogenic medications, mostly labeled as category D or X: cyclophosphamide, enalapril, leflunomide, lisinopril, losartan, methotrexate, mycophenolate, and cyclosporine (category C). This rate varied from 2.2% in 15-year-olds to 13.6% in 19-year-olds.

The number of filled prescriptions for contraception was low despite the associated risk of the teratogenic medications, said Dr. Hays, a third-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

“Each teratogenic medication carries a different risk,” she said. “Certain teratogenic medications carry a greater risk than other teratogenic medications. The associated risk may vary based on the timing and duration of use.”

“The risks and benefits of using a teratogenic medication for treatment should be discussed with teens and women of reproductive age,” Dr. Hays said. “Disease activity should be low, and the teratogenic medication should be replaced with a safer medication prior to pregnancy if one is available. Highly effective forms of contraception should be offered to patients who are at risk for unintended pregnancy and those who are not trying to conceive.”

In addition to rheumatic diseases, the eight teratogenic medications cited in the study are used to treat other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, kidney disease, and malignancy, Dr. Hays said.

The study population was made up of 45.0% whites, 36.6% blacks, 4.8% Hispanics, and 13.6% others.

About 10% were defined as having a specific rheumatic disease, mainly systemic lupus erythematosus (70%), Dr. Hays said. “However, more than 10% had a rheumatic condition of some kind. Generalizations in ICD-9 coding made it difficult to identify specific diseases in some cases.”

The study did not examine birth defect outcomes in the babies born to the females in the cohort, but Dr. Hays said researchers are considering whether to track these numbers via claims data. The study also was not able to capture the use of nonprescribed contraception, such as condoms.

Moving forward, Dr. Hays said the researchers “are planning to also look at pregnancy and contraception rates in age-matched teens not taking teratogenic medications using the same Medicaid claims database. We are also hoping to research patient and provider perspectives pertaining to teratogenic medication use/risk and contraception.”

In addition, researchers hope to examine how commonly the individual drugs were prescribed and link them to contraception use and pregnancy, she said.

The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures, and the study had no external funding. The Medical University of South Carolina provided funding for database access.

SOURCE: Hays K et al. ACR 2017 Abstract 1813.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 7.6% of teen girls taking teratogenic medications became pregnant during a 3-year period.

Study details: An analysis of 4,853 females aged 15-19 on Medicaid who were taking teratogenic medications.

Disclosures: The study authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study had no external funding. The Medical University of South Carolina provided funding for database access.

Source: Hays K et al. ACR 2017 Abstract 1813.

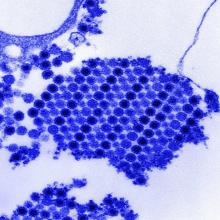

Skin signs spotlight highest-risk SLE patients

GENEVA – Careful warranting prompt initiation of long-term antiplatelet therapy, Dan Lipsker, MD, PhD, said in a plenary lecture at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Those patients are at very high risk. Those are the lupus patients with the poorest prognosis. Those are the lupus patients who still die today,” said Dr. Lipsker, professor of dermatology at the University of Strasbourg (France).

Cutaneous clues suggestive of thrombosis in SLE patients include atrophie blanche, pseudo-Degos lesions, livedo racemosa, acral nonpalpable purpura or reticulate erythema, cutaneous necrosis, splinter hemorrhage, thrombophlebitis, and nailfold telangiectasias. These skin findings can occur simultaneously with or after potentially life-threatening thrombotic events, or in the best of all scenarios, beforehand.

Dr. Lipsker told his audience of dermatologists that, by demonstrating facility in identifying these cutaneous disorders, they can make themselves “indispensable” to the rheumatologists, nephrologists, internists, and/or pediatricians who often provide the bulk of specialized care for SLE patients.

“We know today that, 5 years after initial diagnosis of SLE, the chief causes of morbidity and mortality are thrombotic events. And it can be extremely difficult to distinguish between an acute autoimmune lupus flare and a thrombotic event when, for example, the CNS or eyes are involved. But you will find direct evidence of thrombosis by carefully examining the skin,” the dermatologist maintained.

Some of these cutaneous signs constitute unequivocal evidence of thrombosis in SLE patients. Others are more ambiguous but should raise suspicion of an ongoing systemic thrombotic process unless another explanation is found.

One example of a skin finding that always indicates thrombosis is pseudo-Degos lesions: ivory-colored or white depressed atrophic papules with a raised border composed of telangiectasias. Biopsy shows evidence of a cone-shaped dermal arteriolar infarct.

“We have biopsied dozens of patients with this presentation, and you always find occluded vessels without a single inflammatory cell. These lesions are usually painful, and when you put those patients on low-dose aspirin they do better,” Dr. Lipsker said.

Atrophie blanche in a patient with SLE is also strong evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy. Atrophie blanche is a porcelain-white atrophic white scar with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the lower leg that occurs after skin injury in an area with venous insufficiency.

Livedo racemosa in a patient with SLE is also highly suggestive of a systemic thrombotic process. Characteristic of this dermatologic disorder is an irregular, netlike mottling surrounding pale skin.

“All of these skin signs allow identification of patients who have very high risk of thrombotic events,” Dr. Lipsker stressed.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

GENEVA – Careful warranting prompt initiation of long-term antiplatelet therapy, Dan Lipsker, MD, PhD, said in a plenary lecture at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Those patients are at very high risk. Those are the lupus patients with the poorest prognosis. Those are the lupus patients who still die today,” said Dr. Lipsker, professor of dermatology at the University of Strasbourg (France).

Cutaneous clues suggestive of thrombosis in SLE patients include atrophie blanche, pseudo-Degos lesions, livedo racemosa, acral nonpalpable purpura or reticulate erythema, cutaneous necrosis, splinter hemorrhage, thrombophlebitis, and nailfold telangiectasias. These skin findings can occur simultaneously with or after potentially life-threatening thrombotic events, or in the best of all scenarios, beforehand.

Dr. Lipsker told his audience of dermatologists that, by demonstrating facility in identifying these cutaneous disorders, they can make themselves “indispensable” to the rheumatologists, nephrologists, internists, and/or pediatricians who often provide the bulk of specialized care for SLE patients.

“We know today that, 5 years after initial diagnosis of SLE, the chief causes of morbidity and mortality are thrombotic events. And it can be extremely difficult to distinguish between an acute autoimmune lupus flare and a thrombotic event when, for example, the CNS or eyes are involved. But you will find direct evidence of thrombosis by carefully examining the skin,” the dermatologist maintained.

Some of these cutaneous signs constitute unequivocal evidence of thrombosis in SLE patients. Others are more ambiguous but should raise suspicion of an ongoing systemic thrombotic process unless another explanation is found.

One example of a skin finding that always indicates thrombosis is pseudo-Degos lesions: ivory-colored or white depressed atrophic papules with a raised border composed of telangiectasias. Biopsy shows evidence of a cone-shaped dermal arteriolar infarct.

“We have biopsied dozens of patients with this presentation, and you always find occluded vessels without a single inflammatory cell. These lesions are usually painful, and when you put those patients on low-dose aspirin they do better,” Dr. Lipsker said.

Atrophie blanche in a patient with SLE is also strong evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy. Atrophie blanche is a porcelain-white atrophic white scar with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the lower leg that occurs after skin injury in an area with venous insufficiency.

Livedo racemosa in a patient with SLE is also highly suggestive of a systemic thrombotic process. Characteristic of this dermatologic disorder is an irregular, netlike mottling surrounding pale skin.

“All of these skin signs allow identification of patients who have very high risk of thrombotic events,” Dr. Lipsker stressed.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

GENEVA – Careful warranting prompt initiation of long-term antiplatelet therapy, Dan Lipsker, MD, PhD, said in a plenary lecture at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Those patients are at very high risk. Those are the lupus patients with the poorest prognosis. Those are the lupus patients who still die today,” said Dr. Lipsker, professor of dermatology at the University of Strasbourg (France).

Cutaneous clues suggestive of thrombosis in SLE patients include atrophie blanche, pseudo-Degos lesions, livedo racemosa, acral nonpalpable purpura or reticulate erythema, cutaneous necrosis, splinter hemorrhage, thrombophlebitis, and nailfold telangiectasias. These skin findings can occur simultaneously with or after potentially life-threatening thrombotic events, or in the best of all scenarios, beforehand.

Dr. Lipsker told his audience of dermatologists that, by demonstrating facility in identifying these cutaneous disorders, they can make themselves “indispensable” to the rheumatologists, nephrologists, internists, and/or pediatricians who often provide the bulk of specialized care for SLE patients.

“We know today that, 5 years after initial diagnosis of SLE, the chief causes of morbidity and mortality are thrombotic events. And it can be extremely difficult to distinguish between an acute autoimmune lupus flare and a thrombotic event when, for example, the CNS or eyes are involved. But you will find direct evidence of thrombosis by carefully examining the skin,” the dermatologist maintained.

Some of these cutaneous signs constitute unequivocal evidence of thrombosis in SLE patients. Others are more ambiguous but should raise suspicion of an ongoing systemic thrombotic process unless another explanation is found.

One example of a skin finding that always indicates thrombosis is pseudo-Degos lesions: ivory-colored or white depressed atrophic papules with a raised border composed of telangiectasias. Biopsy shows evidence of a cone-shaped dermal arteriolar infarct.

“We have biopsied dozens of patients with this presentation, and you always find occluded vessels without a single inflammatory cell. These lesions are usually painful, and when you put those patients on low-dose aspirin they do better,” Dr. Lipsker said.

Atrophie blanche in a patient with SLE is also strong evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy. Atrophie blanche is a porcelain-white atrophic white scar with surrounding hyperpigmentation on the lower leg that occurs after skin injury in an area with venous insufficiency.

Livedo racemosa in a patient with SLE is also highly suggestive of a systemic thrombotic process. Characteristic of this dermatologic disorder is an irregular, netlike mottling surrounding pale skin.

“All of these skin signs allow identification of patients who have very high risk of thrombotic events,” Dr. Lipsker stressed.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Identity crisis

The provider has received “advanced-level education in pharmacology, pathophysiology, and physical assessment, diagnosis, and management” and provides patient care in a medical home “in a holistic fashion including physical care, therapeutic treatments, education, and coordination of services.”

This quote comes from a recent story in Pediatric News about collaborative practice. Was the author offering a job description of a) a chiropractor, b) a nurse practitioner, c) a pediatric oncologist, or d) a primary care physician?

Based on my personal experience working with nurse practitioners, both in hospital and office settings, I wholeheartedly concur with Dr. Haut’s list of their qualifications and capabilities. My problem is that she doesn’t list, nor can I comfortably imagine, the additional skills that a physician should have in his or her toolbox to complete the complementary relationships in a primary care practice that Dr. Haut envisions.

From my perspective, nurse practitioners and primary care physicians share the same job description, the one I listed in the first paragraph of this column. They both provide face-to-face, usually hands-on, medical care. At that critical interface between patient and provider, how do their roles differ? What other skills does a physician need to complement those of a competent and already experienced nurse practitioner?

Does being a physician guarantee that he or she has more experience than a nurse practitioner? You know as well as I do that you finished your training pretty wet behind the ears, and the first 5 years or more of your practice career were when you really began to feel like a competent provider. If my child has an earache, I would probably be more comfortable, or at least as comfortable, with her seeing a nurse practitioner with 5 years of experience in a busy practice than a newly minted, board-eligible pediatrician.

Is the breadth of a physician’s training in medical school an asset? Does the 2-month rotation he or she did on the adult neurology service taking care of stroke victims give the physician an advantage when it comes to taking care of pediatric patients with asthma?

Actually, I can imagine a suite of skills that a physician might bring to a collaborative practice that a nurse practitioner may not have, or more likely may have chosen not to pursue. Those skills have little to do with direct patient care, but can be critical for survival in today’s medical care environment. Here I am thinking of things such as negotiating with third-party payers, and leading and/or administering the complexities of a medium-sized or larger medical group. Does having a degree from a medical school automatically mean that the graduate is a skilled leader or administrator?

I can envision that over time a physician and a nurse practitioner might create an arrangement in which one of them focuses on the patients with asthma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and the other develops an expertise in breastfeeding management and picky eating. That kind of relationship fits my definition of complementary. However, a relationship in which the doctor is the boss and the nurse practitioner is not doesn’t feel complementary or collaborative to me.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

The provider has received “advanced-level education in pharmacology, pathophysiology, and physical assessment, diagnosis, and management” and provides patient care in a medical home “in a holistic fashion including physical care, therapeutic treatments, education, and coordination of services.”

This quote comes from a recent story in Pediatric News about collaborative practice. Was the author offering a job description of a) a chiropractor, b) a nurse practitioner, c) a pediatric oncologist, or d) a primary care physician?

Based on my personal experience working with nurse practitioners, both in hospital and office settings, I wholeheartedly concur with Dr. Haut’s list of their qualifications and capabilities. My problem is that she doesn’t list, nor can I comfortably imagine, the additional skills that a physician should have in his or her toolbox to complete the complementary relationships in a primary care practice that Dr. Haut envisions.

From my perspective, nurse practitioners and primary care physicians share the same job description, the one I listed in the first paragraph of this column. They both provide face-to-face, usually hands-on, medical care. At that critical interface between patient and provider, how do their roles differ? What other skills does a physician need to complement those of a competent and already experienced nurse practitioner?

Does being a physician guarantee that he or she has more experience than a nurse practitioner? You know as well as I do that you finished your training pretty wet behind the ears, and the first 5 years or more of your practice career were when you really began to feel like a competent provider. If my child has an earache, I would probably be more comfortable, or at least as comfortable, with her seeing a nurse practitioner with 5 years of experience in a busy practice than a newly minted, board-eligible pediatrician.

Is the breadth of a physician’s training in medical school an asset? Does the 2-month rotation he or she did on the adult neurology service taking care of stroke victims give the physician an advantage when it comes to taking care of pediatric patients with asthma?

Actually, I can imagine a suite of skills that a physician might bring to a collaborative practice that a nurse practitioner may not have, or more likely may have chosen not to pursue. Those skills have little to do with direct patient care, but can be critical for survival in today’s medical care environment. Here I am thinking of things such as negotiating with third-party payers, and leading and/or administering the complexities of a medium-sized or larger medical group. Does having a degree from a medical school automatically mean that the graduate is a skilled leader or administrator?

I can envision that over time a physician and a nurse practitioner might create an arrangement in which one of them focuses on the patients with asthma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and the other develops an expertise in breastfeeding management and picky eating. That kind of relationship fits my definition of complementary. However, a relationship in which the doctor is the boss and the nurse practitioner is not doesn’t feel complementary or collaborative to me.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

The provider has received “advanced-level education in pharmacology, pathophysiology, and physical assessment, diagnosis, and management” and provides patient care in a medical home “in a holistic fashion including physical care, therapeutic treatments, education, and coordination of services.”

This quote comes from a recent story in Pediatric News about collaborative practice. Was the author offering a job description of a) a chiropractor, b) a nurse practitioner, c) a pediatric oncologist, or d) a primary care physician?

Based on my personal experience working with nurse practitioners, both in hospital and office settings, I wholeheartedly concur with Dr. Haut’s list of their qualifications and capabilities. My problem is that she doesn’t list, nor can I comfortably imagine, the additional skills that a physician should have in his or her toolbox to complete the complementary relationships in a primary care practice that Dr. Haut envisions.

From my perspective, nurse practitioners and primary care physicians share the same job description, the one I listed in the first paragraph of this column. They both provide face-to-face, usually hands-on, medical care. At that critical interface between patient and provider, how do their roles differ? What other skills does a physician need to complement those of a competent and already experienced nurse practitioner?

Does being a physician guarantee that he or she has more experience than a nurse practitioner? You know as well as I do that you finished your training pretty wet behind the ears, and the first 5 years or more of your practice career were when you really began to feel like a competent provider. If my child has an earache, I would probably be more comfortable, or at least as comfortable, with her seeing a nurse practitioner with 5 years of experience in a busy practice than a newly minted, board-eligible pediatrician.

Is the breadth of a physician’s training in medical school an asset? Does the 2-month rotation he or she did on the adult neurology service taking care of stroke victims give the physician an advantage when it comes to taking care of pediatric patients with asthma?

Actually, I can imagine a suite of skills that a physician might bring to a collaborative practice that a nurse practitioner may not have, or more likely may have chosen not to pursue. Those skills have little to do with direct patient care, but can be critical for survival in today’s medical care environment. Here I am thinking of things such as negotiating with third-party payers, and leading and/or administering the complexities of a medium-sized or larger medical group. Does having a degree from a medical school automatically mean that the graduate is a skilled leader or administrator?

I can envision that over time a physician and a nurse practitioner might create an arrangement in which one of them focuses on the patients with asthma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and the other develops an expertise in breastfeeding management and picky eating. That kind of relationship fits my definition of complementary. However, a relationship in which the doctor is the boss and the nurse practitioner is not doesn’t feel complementary or collaborative to me.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Long-acting naltrexone tied to fewer detox admissions, more treatment engagement

SAN DIEGO – Persistence with long-acting naltrexone treatment was associated with significantly reduced detoxification admissions and concurrent engagement in treatment, a retrospective study of veterans found.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved long-acting naltrexone hydrochloride for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and opioid use disorder (OUD), but little is known about the patients who initiate and continue this therapy, Grace Chang, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting and scientific symposium of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. In an effort to evaluate the characteristics associated with long-term naltrexone treatment persistence, Dr. Chang, chief of consultation-liaison psychiatry at the VA Boston Healthcare System, and her associates studied 154 veterans who initiated long-acting naltrexone therapy for AUD or OUD between 2014 and 2015.

Among those who died in the study year after the index shot, no difference in the average number of long-acting naltrexone injections was observed (5.3 in the OUD group vs. 6.8 in the AUD group, P = .62). There was a long interval between the last known injection of long-acting naltrexone and the date of death (381 days in the OUD group vs. 326 days in the AUD group, P = .67). The cause of death was unknown in 57% of cases, while 21% were from natural causes, and 21% were tied to overdose or self-inflicted injury.

The rates of posttraumatic stress disorder in the OUD and AUD groups were about the same, but the AUD patients had higher rates of mood disorder and anxiety disorder. The AUD patients had higher rates of cardiac disease and pulmonary disease, while the OUD patients had higher rates of musculoskeletal problems. Renal disease was relatively rare in both groups. “The AUD patients started using their drug of choice earlier, but the groups were comparable in being able to attain over 2 years of abstinence at some point,” said Dr. Chang, who is also professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Both groups had about two detoxes in the year prior to the index shot.

“ We were also curious about what other drugs they were using prior to starting naltrexone. The OUD patients used more stimulants, more cocaine, and more sedative hypnotics. Smoking was endemic in both of these groups, as was marijuana use.”

The average interval from the time patients in both groups made the decision to start long-acting naltrexone to the time they received their first shot was about 2 months. “It’s safe to say that no one rushed into this,” Dr. Chang said. “The mean number of injections for the study year was about 5, which was very high, and the range was from 1 to 13, which suggests that some people got a shot every single month. Both of the groups had similar numbers of individual treatment sessions, which was about one. They had almost two residential admissions after the index shot and at least one other appointment with a prescribing psychiatrist.”

On Poisson regression analysis, factors associated with increased medication persistence included percent service connection and number of individual, group, residential, and other treatment modalities attended (P less than .05 for all associations). For each unit increase in the number of individual sessions, the number of long-acting naltrexone shots would go up by 7%, Dr. Chang said. For each unit increase in the number of group sessions, the number of long-acting naltrexone therapy shots would go up by 5%, while for each residential admission session, the number of long-acting naltrexone shots would go up by 14%.

“Keep in mind that our patients had an average of two residential admissions, so the number of shots went up by 28%,” she said. “For the number of other appointments with the addiction psychiatrist, the number of shots went up by 6%.”

Dr. Chang acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the relatively small sample size. “What was good to see is that the number of inpatient detox admissions was halved, when comparing the year before and the year after the shot,” she said. “This was highly statistically significant. Concurrent psychosocial treatment is highly important in the treatment persistence with this modality.”

Dr. Chang reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Persistence with long-acting naltrexone treatment was associated with significantly reduced detoxification admissions and concurrent engagement in treatment, a retrospective study of veterans found.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved long-acting naltrexone hydrochloride for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and opioid use disorder (OUD), but little is known about the patients who initiate and continue this therapy, Grace Chang, MD, MPH, said at the annual meeting and scientific symposium of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. In an effort to evaluate the characteristics associated with long-term naltrexone treatment persistence, Dr. Chang, chief of consultation-liaison psychiatry at the VA Boston Healthcare System, and her associates studied 154 veterans who initiated long-acting naltrexone therapy for AUD or OUD between 2014 and 2015.

Among those who died in the study year after the index shot, no difference in the average number of long-acting naltrexone injections was observed (5.3 in the OUD group vs. 6.8 in the AUD group, P = .62). There was a long interval between the last known injection of long-acting naltrexone and the date of death (381 days in the OUD group vs. 326 days in the AUD group, P = .67). The cause of death was unknown in 57% of cases, while 21% were from natural causes, and 21% were tied to overdose or self-inflicted injury.

The rates of posttraumatic stress disorder in the OUD and AUD groups were about the same, but the AUD patients had higher rates of mood disorder and anxiety disorder. The AUD patients had higher rates of cardiac disease and pulmonary disease, while the OUD patients had higher rates of musculoskeletal problems. Renal disease was relatively rare in both groups. “The AUD patients started using their drug of choice earlier, but the groups were comparable in being able to attain over 2 years of abstinence at some point,” said Dr. Chang, who is also professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Both groups had about two detoxes in the year prior to the index shot.

“ We were also curious about what other drugs they were using prior to starting naltrexone. The OUD patients used more stimulants, more cocaine, and more sedative hypnotics. Smoking was endemic in both of these groups, as was marijuana use.”

The average interval from the time patients in both groups made the decision to start long-acting naltrexone to the time they received their first shot was about 2 months. “It’s safe to say that no one rushed into this,” Dr. Chang said. “The mean number of injections for the study year was about 5, which was very high, and the range was from 1 to 13, which suggests that some people got a shot every single month. Both of the groups had similar numbers of individual treatment sessions, which was about one. They had almost two residential admissions after the index shot and at least one other appointment with a prescribing psychiatrist.”

On Poisson regression analysis, factors associated with increased medication persistence included percent service connection and number of individual, group, residential, and other treatment modalities attended (P less than .05 for all associations). For each unit increase in the number of individual sessions, the number of long-acting naltrexone shots would go up by 7%, Dr. Chang said. For each unit increase in the number of group sessions, the number of long-acting naltrexone therapy shots would go up by 5%, while for each residential admission session, the number of long-acting naltrexone shots would go up by 14%.

“Keep in mind that our patients had an average of two residential admissions, so the number of shots went up by 28%,” she said. “For the number of other appointments with the addiction psychiatrist, the number of shots went up by 6%.”

Dr. Chang acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the relatively small sample size. “What was good to see is that the number of inpatient detox admissions was halved, when comparing the year before and the year after the shot,” she said. “This was highly statistically significant. Concurrent psychosocial treatment is highly important in the treatment persistence with this modality.”

Dr. Chang reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Persistence with long-acting naltrexone treatment was associated with significantly reduced detoxification admissions and concurrent engagement in treatment, a retrospective study of veterans found.