User login

Drug receives fast track, orphan designations for PTCL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug and fast track designations to tenalisib (RP6530) for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Tenalisib is a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor being developed by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals.

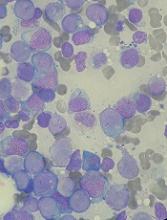

Research has shown that tenalisib inhibits the growth of immortalized cancerous cell lines and primary leukemia/lymphoma cells.

In preclinical studies, tenalisib reprogrammed macrophages from an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype (pro-tumor) to an inflammatory M1-like state (anti-tumor).

Researchers are currently conducting a phase 1 study of tenalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL. Results from this study were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2791*).

The presentation included data on 50 patients—24 with PTCL and 26 with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

For the PTCL patients, the median age was 63 (range, 40-89), and 67% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 1-7). All patients had an ECOG status of 0 (n=14) or 1 (n=10). More patients had relapsed disease (n=17, 58%) than refractory disease (n=10, 42%).

For the CTCL patients, the median age was 67 (range, 37-84), and 46% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 5.5 (range, 2-15). All patients had an ECOG status of 0 (n=23) or 1 (n=3). More patients had refractory disease (n=15, 58%) than relapsed disease (n=11, 42%).

In the dose-escalation portion of the study, patients received tenalisib at 200 mg twice daily (BID), 400 mg BID, 800 mg BID fasting, or 800 mg BID fed. The maximum tolerated dose was 800 mg BID fasting, so this dose is being used in the expansion cohort.

Twelve PTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. The overall response rate in these patients was 58% (7/12), with a 25% complete response rate (3/12).

Sixteen CTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. The overall response rate was 56% (9/16). All responders had partial responses.

In both PTCL and CTCL patients, treatment-related grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs) included transaminitis (22%), rash (6%), neutropenia (6%), hypophosphatemia (2%), increased international normalized ratio (2%), diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%), and sepsis (2%).

Treatment-related serious AEs included sepsis, increased international normalized ratio, diplopia secondary to neuropathy, and pyrexia. Five patients discontinued treatment due to AEs.

About orphan and fast track designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug and fast track designations to tenalisib (RP6530) for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Tenalisib is a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor being developed by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals.

Research has shown that tenalisib inhibits the growth of immortalized cancerous cell lines and primary leukemia/lymphoma cells.

In preclinical studies, tenalisib reprogrammed macrophages from an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype (pro-tumor) to an inflammatory M1-like state (anti-tumor).

Researchers are currently conducting a phase 1 study of tenalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL. Results from this study were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2791*).

The presentation included data on 50 patients—24 with PTCL and 26 with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

For the PTCL patients, the median age was 63 (range, 40-89), and 67% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 1-7). All patients had an ECOG status of 0 (n=14) or 1 (n=10). More patients had relapsed disease (n=17, 58%) than refractory disease (n=10, 42%).

For the CTCL patients, the median age was 67 (range, 37-84), and 46% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 5.5 (range, 2-15). All patients had an ECOG status of 0 (n=23) or 1 (n=3). More patients had refractory disease (n=15, 58%) than relapsed disease (n=11, 42%).

In the dose-escalation portion of the study, patients received tenalisib at 200 mg twice daily (BID), 400 mg BID, 800 mg BID fasting, or 800 mg BID fed. The maximum tolerated dose was 800 mg BID fasting, so this dose is being used in the expansion cohort.

Twelve PTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. The overall response rate in these patients was 58% (7/12), with a 25% complete response rate (3/12).

Sixteen CTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. The overall response rate was 56% (9/16). All responders had partial responses.

In both PTCL and CTCL patients, treatment-related grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs) included transaminitis (22%), rash (6%), neutropenia (6%), hypophosphatemia (2%), increased international normalized ratio (2%), diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%), and sepsis (2%).

Treatment-related serious AEs included sepsis, increased international normalized ratio, diplopia secondary to neuropathy, and pyrexia. Five patients discontinued treatment due to AEs.

About orphan and fast track designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug and fast track designations to tenalisib (RP6530) for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Tenalisib is a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor being developed by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals.

Research has shown that tenalisib inhibits the growth of immortalized cancerous cell lines and primary leukemia/lymphoma cells.

In preclinical studies, tenalisib reprogrammed macrophages from an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype (pro-tumor) to an inflammatory M1-like state (anti-tumor).

Researchers are currently conducting a phase 1 study of tenalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL. Results from this study were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 2791*).

The presentation included data on 50 patients—24 with PTCL and 26 with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

For the PTCL patients, the median age was 63 (range, 40-89), and 67% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 1-7). All patients had an ECOG status of 0 (n=14) or 1 (n=10). More patients had relapsed disease (n=17, 58%) than refractory disease (n=10, 42%).

For the CTCL patients, the median age was 67 (range, 37-84), and 46% were male. The median number of prior therapies was 5.5 (range, 2-15). All patients had an ECOG status of 0 (n=23) or 1 (n=3). More patients had refractory disease (n=15, 58%) than relapsed disease (n=11, 42%).

In the dose-escalation portion of the study, patients received tenalisib at 200 mg twice daily (BID), 400 mg BID, 800 mg BID fasting, or 800 mg BID fed. The maximum tolerated dose was 800 mg BID fasting, so this dose is being used in the expansion cohort.

Twelve PTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. The overall response rate in these patients was 58% (7/12), with a 25% complete response rate (3/12).

Sixteen CTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. The overall response rate was 56% (9/16). All responders had partial responses.

In both PTCL and CTCL patients, treatment-related grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs) included transaminitis (22%), rash (6%), neutropenia (6%), hypophosphatemia (2%), increased international normalized ratio (2%), diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%), and sepsis (2%).

Treatment-related serious AEs included sepsis, increased international normalized ratio, diplopia secondary to neuropathy, and pyrexia. Five patients discontinued treatment due to AEs.

About orphan and fast track designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

FDA grants orphan designation to drug for AML

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to CG’806 for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

CG’806 is an oral, first-in-class pan-FLT3/pan-BTK inhibitor being developed by Aptose Biosciences Inc.

In preclinical studies, CG’806 inhibited all wild-type and mutant forms of FLT3 tested, suppressed multiple oncogenic pathways operative in AML, and eliminated AML tumors (without toxicity) in murine xenograft models.

In addition, CG’806 demonstrated non-covalent inhibition of the wild-type and Cys481Ser mutant forms of the BTK enzyme, as well as other oncogenic kinases operative in B-cell malignancies.

Preclinical results with CG’806 were presented as posters at the AACR conference “Hematologic Malignancies: Translating Discoveries to Novel Therapies,” which took place last May.

“Results from non-clinical studies that we and our research collaborators have generated are promising and give reason for our eagerness to begin clinical trials in both AML and B-cell malignancies in 2018,” said William G. Rice, PhD, chairman, president, and chief executive officer at Aptose.

“We are pleased that the FDA has recognized the unique potential of CG’806 to address AML and has assigned CG’806 the status of orphan drug designation.”

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to CG’806 for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

CG’806 is an oral, first-in-class pan-FLT3/pan-BTK inhibitor being developed by Aptose Biosciences Inc.

In preclinical studies, CG’806 inhibited all wild-type and mutant forms of FLT3 tested, suppressed multiple oncogenic pathways operative in AML, and eliminated AML tumors (without toxicity) in murine xenograft models.

In addition, CG’806 demonstrated non-covalent inhibition of the wild-type and Cys481Ser mutant forms of the BTK enzyme, as well as other oncogenic kinases operative in B-cell malignancies.

Preclinical results with CG’806 were presented as posters at the AACR conference “Hematologic Malignancies: Translating Discoveries to Novel Therapies,” which took place last May.

“Results from non-clinical studies that we and our research collaborators have generated are promising and give reason for our eagerness to begin clinical trials in both AML and B-cell malignancies in 2018,” said William G. Rice, PhD, chairman, president, and chief executive officer at Aptose.

“We are pleased that the FDA has recognized the unique potential of CG’806 to address AML and has assigned CG’806 the status of orphan drug designation.”

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to CG’806 for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

CG’806 is an oral, first-in-class pan-FLT3/pan-BTK inhibitor being developed by Aptose Biosciences Inc.

In preclinical studies, CG’806 inhibited all wild-type and mutant forms of FLT3 tested, suppressed multiple oncogenic pathways operative in AML, and eliminated AML tumors (without toxicity) in murine xenograft models.

In addition, CG’806 demonstrated non-covalent inhibition of the wild-type and Cys481Ser mutant forms of the BTK enzyme, as well as other oncogenic kinases operative in B-cell malignancies.

Preclinical results with CG’806 were presented as posters at the AACR conference “Hematologic Malignancies: Translating Discoveries to Novel Therapies,” which took place last May.

“Results from non-clinical studies that we and our research collaborators have generated are promising and give reason for our eagerness to begin clinical trials in both AML and B-cell malignancies in 2018,” said William G. Rice, PhD, chairman, president, and chief executive officer at Aptose.

“We are pleased that the FDA has recognized the unique potential of CG’806 to address AML and has assigned CG’806 the status of orphan drug designation.”

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

Addition of azithromycin to maintenance therapy is beneficial in adults with uncontrolled asthma

Clinical question: Does azithromycin decrease the frequency of asthma exacerbations in adults with persistent asthma symptoms despite use of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA)?

Background: Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease that is highly prevalent worldwide within a subset of people with asthma who have symptoms that are poorly controlled despite ICS and LABA maintenance therapy. Currently, add-on therapy options include monoclonal antibodies, which are cost prohibitive. The need for additional therapeutic options exists. At the same time, macrolide antibiotics are known to have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antibacterial effects and have proven to have beneficial effects on asthma symptoms.

Setting: Multiple sites throughout Australia.

Synopsis: The AMAZES trial enrolled 420 adult patients with symptomatic asthma despite current use of ICS and LABA. Patients were randomly assigned to receive azithromycin 500 mg or placebo three times a week for 48 weeks. Patients who had hearing impairment, prolonged QTc interval, or emphysema were excluded.

Azithromycin reduced the frequency of asthma exacerbations, compared with placebo (1.07 vs. 1.86 exacerbations/patient-year; incidence rate ratio 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.47-0.74; P less than .0001). It also significantly improved asthma-related quality of life according to the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (adjusted mean difference, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21-0.52; P = .001). Diarrhea occurred more commonly in the azithromycin group but did not result in a higher withdrawal rate.

A significant limitation of this study was generalizability, as the median patient age was 60 years and race was not reported. More research is needed to determine the effect of long-term azithromycin use on microbial resistance.

Bottom line: Adding azithromycin to maintenance ICS and LABA therapy in patients with symptomatic asthma decreased the frequency of asthma exacerbations and improved quality of life.

Citation: Gibson PG et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Aug 12;390(10095):659-68.

Dr. Farber is a medical instructor, Duke University Health System.

Clinical question: Does azithromycin decrease the frequency of asthma exacerbations in adults with persistent asthma symptoms despite use of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA)?

Background: Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease that is highly prevalent worldwide within a subset of people with asthma who have symptoms that are poorly controlled despite ICS and LABA maintenance therapy. Currently, add-on therapy options include monoclonal antibodies, which are cost prohibitive. The need for additional therapeutic options exists. At the same time, macrolide antibiotics are known to have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antibacterial effects and have proven to have beneficial effects on asthma symptoms.

Setting: Multiple sites throughout Australia.

Synopsis: The AMAZES trial enrolled 420 adult patients with symptomatic asthma despite current use of ICS and LABA. Patients were randomly assigned to receive azithromycin 500 mg or placebo three times a week for 48 weeks. Patients who had hearing impairment, prolonged QTc interval, or emphysema were excluded.

Azithromycin reduced the frequency of asthma exacerbations, compared with placebo (1.07 vs. 1.86 exacerbations/patient-year; incidence rate ratio 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.47-0.74; P less than .0001). It also significantly improved asthma-related quality of life according to the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (adjusted mean difference, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21-0.52; P = .001). Diarrhea occurred more commonly in the azithromycin group but did not result in a higher withdrawal rate.

A significant limitation of this study was generalizability, as the median patient age was 60 years and race was not reported. More research is needed to determine the effect of long-term azithromycin use on microbial resistance.

Bottom line: Adding azithromycin to maintenance ICS and LABA therapy in patients with symptomatic asthma decreased the frequency of asthma exacerbations and improved quality of life.

Citation: Gibson PG et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Aug 12;390(10095):659-68.

Dr. Farber is a medical instructor, Duke University Health System.

Clinical question: Does azithromycin decrease the frequency of asthma exacerbations in adults with persistent asthma symptoms despite use of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA)?

Background: Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease that is highly prevalent worldwide within a subset of people with asthma who have symptoms that are poorly controlled despite ICS and LABA maintenance therapy. Currently, add-on therapy options include monoclonal antibodies, which are cost prohibitive. The need for additional therapeutic options exists. At the same time, macrolide antibiotics are known to have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antibacterial effects and have proven to have beneficial effects on asthma symptoms.

Setting: Multiple sites throughout Australia.

Synopsis: The AMAZES trial enrolled 420 adult patients with symptomatic asthma despite current use of ICS and LABA. Patients were randomly assigned to receive azithromycin 500 mg or placebo three times a week for 48 weeks. Patients who had hearing impairment, prolonged QTc interval, or emphysema were excluded.

Azithromycin reduced the frequency of asthma exacerbations, compared with placebo (1.07 vs. 1.86 exacerbations/patient-year; incidence rate ratio 0.59; 95% confidence interval, 0.47-0.74; P less than .0001). It also significantly improved asthma-related quality of life according to the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (adjusted mean difference, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21-0.52; P = .001). Diarrhea occurred more commonly in the azithromycin group but did not result in a higher withdrawal rate.

A significant limitation of this study was generalizability, as the median patient age was 60 years and race was not reported. More research is needed to determine the effect of long-term azithromycin use on microbial resistance.

Bottom line: Adding azithromycin to maintenance ICS and LABA therapy in patients with symptomatic asthma decreased the frequency of asthma exacerbations and improved quality of life.

Citation: Gibson PG et al. Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Aug 12;390(10095):659-68.

Dr. Farber is a medical instructor, Duke University Health System.

Axillary node dissection can be avoided with limited SLN involvement

SAN ANTONIO – Axillary dissection can be avoided in patients with early breast cancer and limited sentinel node involvement, investigators reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Both disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were similar in a population of patients with cT1-T2 N0M0 breast cancer and sentinel node micrometastases who underwent axillary dissection (AD), compared with those who did not. Complications associated with axillary surgery can be avoided in this population, without any adverse effect on survival.

“Our findings are fully consistent with those of the Z0011 trial, which after 10 years found no differences between the AD and no-AD groups for any endpoint in patients with moderate disease burden in the axilla undergoing conservative breast surgery,” said study author Viviana Galimberti, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology in Milan.

In the ACOSOG Z0011, trial, the use of sentinel node biopsy alone was not inferior to AD in patients with limited sentinel node metastasis treated with breast conservation and systemic therapy.

“We also suggest that non-AD is acceptable treatment in patients scheduled for mastectomy,” Dr. Galimberti said.

For patients with breast cancer and metastases in the sentinel nodes, AD has been the standard of care, but for those with limited sentinel node involvement, it was hypothesized that AD might not be necessary.

The phase 3 IBCSG 23-01 study was a multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial that compared DFS in breast cancer patients with one or more micrometastases (greater than or equal to 2 mm) in the sentinel nodes who were randomized to either AD or no axillary dissection (no-AD). The 5-year results, which were published in 2013 in the Lancet Oncology (2013 Jun;14[7]:e251-2) showed no difference in DFS between the two groups.

At the meeting, Dr. Galimberti reported on outcomes after an extended median follow-up of 9.8 years. A cohort of 934 women (931 evaluable) were enrolled from 27 centers from 2001 to 2010 and randomized to either AD or no AD (467 in the no-AD group and 464 in the AD group).

The results were similar to those reported at 5 years. The 10-year DFS rates were similar for both cohorts; 77% for non-AD vs. 75% for AD (hazard ratio [no-AD vs. AD], 0.85; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.11; log-rank P = .23; noninferiority P = .002).

The rate of axillary failure in the no-AD group was low, Dr. Galimberti pointed out, at 1.7% and 0.8% among women who underwent breast-conserving surgery. There were nine ipsilateral axillary events in the no-AD group vs. three in the AD group, and 45 deaths in the no-AD group vs. 58 in the AD group. The 10-year OS was 91% (95% CI, 88%-94%) in the no-AD group and 88% (95% CI, 85%-92%) in the AD group (HR [no-AD vs. AD], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56-1.07; log-rank P = .19).

There was no difference between groups for the main endpoint of DFS or the secondary endpoint of OS, said Dr. Galimberti.

In subgroup analyses, which included tumor size, estrogen-receptor status, progesterone-receptor status, tumor grade, and type of surgery, there were no subgroups identified that benefited from AD over no-AD.

“Our data fully support the change in clinical practice that started after the early published results,” Dr Galimberti concluded. “No AD is now standard treatment in early breast cancer when the sentinel node is only minimally involved.”

The study received no outside funding and the authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Galimberti et al. SABCS Abstract GS5-02

SAN ANTONIO – Axillary dissection can be avoided in patients with early breast cancer and limited sentinel node involvement, investigators reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Both disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were similar in a population of patients with cT1-T2 N0M0 breast cancer and sentinel node micrometastases who underwent axillary dissection (AD), compared with those who did not. Complications associated with axillary surgery can be avoided in this population, without any adverse effect on survival.

“Our findings are fully consistent with those of the Z0011 trial, which after 10 years found no differences between the AD and no-AD groups for any endpoint in patients with moderate disease burden in the axilla undergoing conservative breast surgery,” said study author Viviana Galimberti, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology in Milan.

In the ACOSOG Z0011, trial, the use of sentinel node biopsy alone was not inferior to AD in patients with limited sentinel node metastasis treated with breast conservation and systemic therapy.

“We also suggest that non-AD is acceptable treatment in patients scheduled for mastectomy,” Dr. Galimberti said.

For patients with breast cancer and metastases in the sentinel nodes, AD has been the standard of care, but for those with limited sentinel node involvement, it was hypothesized that AD might not be necessary.

The phase 3 IBCSG 23-01 study was a multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial that compared DFS in breast cancer patients with one or more micrometastases (greater than or equal to 2 mm) in the sentinel nodes who were randomized to either AD or no axillary dissection (no-AD). The 5-year results, which were published in 2013 in the Lancet Oncology (2013 Jun;14[7]:e251-2) showed no difference in DFS between the two groups.

At the meeting, Dr. Galimberti reported on outcomes after an extended median follow-up of 9.8 years. A cohort of 934 women (931 evaluable) were enrolled from 27 centers from 2001 to 2010 and randomized to either AD or no AD (467 in the no-AD group and 464 in the AD group).

The results were similar to those reported at 5 years. The 10-year DFS rates were similar for both cohorts; 77% for non-AD vs. 75% for AD (hazard ratio [no-AD vs. AD], 0.85; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.11; log-rank P = .23; noninferiority P = .002).

The rate of axillary failure in the no-AD group was low, Dr. Galimberti pointed out, at 1.7% and 0.8% among women who underwent breast-conserving surgery. There were nine ipsilateral axillary events in the no-AD group vs. three in the AD group, and 45 deaths in the no-AD group vs. 58 in the AD group. The 10-year OS was 91% (95% CI, 88%-94%) in the no-AD group and 88% (95% CI, 85%-92%) in the AD group (HR [no-AD vs. AD], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56-1.07; log-rank P = .19).

There was no difference between groups for the main endpoint of DFS or the secondary endpoint of OS, said Dr. Galimberti.

In subgroup analyses, which included tumor size, estrogen-receptor status, progesterone-receptor status, tumor grade, and type of surgery, there were no subgroups identified that benefited from AD over no-AD.

“Our data fully support the change in clinical practice that started after the early published results,” Dr Galimberti concluded. “No AD is now standard treatment in early breast cancer when the sentinel node is only minimally involved.”

The study received no outside funding and the authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Galimberti et al. SABCS Abstract GS5-02

SAN ANTONIO – Axillary dissection can be avoided in patients with early breast cancer and limited sentinel node involvement, investigators reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Both disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were similar in a population of patients with cT1-T2 N0M0 breast cancer and sentinel node micrometastases who underwent axillary dissection (AD), compared with those who did not. Complications associated with axillary surgery can be avoided in this population, without any adverse effect on survival.

“Our findings are fully consistent with those of the Z0011 trial, which after 10 years found no differences between the AD and no-AD groups for any endpoint in patients with moderate disease burden in the axilla undergoing conservative breast surgery,” said study author Viviana Galimberti, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology in Milan.

In the ACOSOG Z0011, trial, the use of sentinel node biopsy alone was not inferior to AD in patients with limited sentinel node metastasis treated with breast conservation and systemic therapy.

“We also suggest that non-AD is acceptable treatment in patients scheduled for mastectomy,” Dr. Galimberti said.

For patients with breast cancer and metastases in the sentinel nodes, AD has been the standard of care, but for those with limited sentinel node involvement, it was hypothesized that AD might not be necessary.

The phase 3 IBCSG 23-01 study was a multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial that compared DFS in breast cancer patients with one or more micrometastases (greater than or equal to 2 mm) in the sentinel nodes who were randomized to either AD or no axillary dissection (no-AD). The 5-year results, which were published in 2013 in the Lancet Oncology (2013 Jun;14[7]:e251-2) showed no difference in DFS between the two groups.

At the meeting, Dr. Galimberti reported on outcomes after an extended median follow-up of 9.8 years. A cohort of 934 women (931 evaluable) were enrolled from 27 centers from 2001 to 2010 and randomized to either AD or no AD (467 in the no-AD group and 464 in the AD group).

The results were similar to those reported at 5 years. The 10-year DFS rates were similar for both cohorts; 77% for non-AD vs. 75% for AD (hazard ratio [no-AD vs. AD], 0.85; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.11; log-rank P = .23; noninferiority P = .002).

The rate of axillary failure in the no-AD group was low, Dr. Galimberti pointed out, at 1.7% and 0.8% among women who underwent breast-conserving surgery. There were nine ipsilateral axillary events in the no-AD group vs. three in the AD group, and 45 deaths in the no-AD group vs. 58 in the AD group. The 10-year OS was 91% (95% CI, 88%-94%) in the no-AD group and 88% (95% CI, 85%-92%) in the AD group (HR [no-AD vs. AD], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56-1.07; log-rank P = .19).

There was no difference between groups for the main endpoint of DFS or the secondary endpoint of OS, said Dr. Galimberti.

In subgroup analyses, which included tumor size, estrogen-receptor status, progesterone-receptor status, tumor grade, and type of surgery, there were no subgroups identified that benefited from AD over no-AD.

“Our data fully support the change in clinical practice that started after the early published results,” Dr Galimberti concluded. “No AD is now standard treatment in early breast cancer when the sentinel node is only minimally involved.”

The study received no outside funding and the authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Galimberti et al. SABCS Abstract GS5-02

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2017

Key clinical point: Axillary dissection can be avoided in patients with early breast cancer and limited sentinel node involvement.

Major finding: At 10 years the disease-free rates were 77% for the no–axillary dissection group and 75% for the axillary dissection group (HR [no-AD vs. AD], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.65-1.11; log-rank P = .23; noninferiority P = .002).

Data source: Updated results of the phase 3 IBCSG 23-01 study, a multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial that included 934 participants.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding and the authors had no disclosures.

Source: Galimberti et al. SABCS Abstract GS5-02.

Single-agent daratumumab active in smoldering multiple myeloma

ATLANTA – Daratumumab monotherapy led to durable partial responses among intermediate to high-risk patients with smoldering multiple myeloma, according to results from the phase II CENTAURUS trial.

Although less than 5% of patients had complete responses, 27% had at least a very good partial response to long-term therapy (up to 20 treatment cycles lasting 8 weeks each), Craig C. Hofmeister, MD, of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The coprimary endpoint, median progression-free survival, exceeded 24 months in all dose cohorts, and was the longest when patients were treated longest.

Current guidelines recommend monitoring smoldering multiple myeloma every 3-6 months and treating only after patients progress. However, some experts pursue earlier treatment in the premalignant setting.

In CENTAURUS, 123 adults with smoldering multiple myeloma were randomly assigned to receive daratumumab (16 mg/kg IV) in 8-week cycles according to a long, intermediate, or short/intense schedule. The long schedule consisted of treatment weekly for cycle 1, every other week for cycles 2-3, monthly for cycles 4-7, and once every 8 weeks for up to 13 more cycles. The intermediate schedule consisted of treatment weekly in cycle 1 and every 8 weeks for up to 20 cycles. The short, intense schedule consisted of weekly treatment for 8 weeks (one cycle). Patients were followed for up to 4 years or until they progressed to multiple myeloma based on International Myeloma Working Group guidelines.

Over a median follow-up period of 15.8 months (range, 0 to 24 months), rates of complete response were 2% in the long treatment arm, 5% in the intermediate treatment arm, and 0% in the short treatment arm. Rates of at least very good partial response were 29%, 24%, and 15%, respectively. Overall response rates were 56%, 54%, and 38%, respectively. Median PFS was not reached in any arm, exceeding 24 months.

Treatment was generally well tolerated, said Dr. Hofmeister. The most common treatment-related adverse effects were fatigue, cough, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and insomnia. Hypertension and hyperglycemia were the most common grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events, affecting up to 5% of patients per arm. Fewer than 10% of patients in any arm developed treatment-emergent hematologic adverse events, and fewer than 5% developed grade 3-4 pneumonia or sepsis. There were three cases of a second primary malignancy, including one case of breast cancer and two cases of melanoma.

Rates of infusion-related reactions did not correlate with treatment duration. Grade 3-4 infusion-related reactions affected 0% to 3% of patients per arm. The sole death in this trial resulted from disease progression in a patient from the short treatment arm. “Taken together, efficacy and safety data support long dosing compared to intermediate and short dosing,” Dr. Hofmeister said.

The three arms were demographically similar. Patients tended to be white, in their late 50s to 60s, and to have ECOG scores of 0 with at least two risk factors for progression. About 70% had IgG disease and nearly half had less than 20% plasma cells in bone marrow.

Janssen, the maker of daratumumab, sponsored the trial. Dr. Hofmeister disclosed research funding from Janssen and research support, honoraria, and advisory relationships with Adaptive Biotechnologies, Thrasos, Celgene, Karyopharm, Takeda, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Hofmeister C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 510.

ATLANTA – Daratumumab monotherapy led to durable partial responses among intermediate to high-risk patients with smoldering multiple myeloma, according to results from the phase II CENTAURUS trial.

Although less than 5% of patients had complete responses, 27% had at least a very good partial response to long-term therapy (up to 20 treatment cycles lasting 8 weeks each), Craig C. Hofmeister, MD, of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The coprimary endpoint, median progression-free survival, exceeded 24 months in all dose cohorts, and was the longest when patients were treated longest.

Current guidelines recommend monitoring smoldering multiple myeloma every 3-6 months and treating only after patients progress. However, some experts pursue earlier treatment in the premalignant setting.

In CENTAURUS, 123 adults with smoldering multiple myeloma were randomly assigned to receive daratumumab (16 mg/kg IV) in 8-week cycles according to a long, intermediate, or short/intense schedule. The long schedule consisted of treatment weekly for cycle 1, every other week for cycles 2-3, monthly for cycles 4-7, and once every 8 weeks for up to 13 more cycles. The intermediate schedule consisted of treatment weekly in cycle 1 and every 8 weeks for up to 20 cycles. The short, intense schedule consisted of weekly treatment for 8 weeks (one cycle). Patients were followed for up to 4 years or until they progressed to multiple myeloma based on International Myeloma Working Group guidelines.

Over a median follow-up period of 15.8 months (range, 0 to 24 months), rates of complete response were 2% in the long treatment arm, 5% in the intermediate treatment arm, and 0% in the short treatment arm. Rates of at least very good partial response were 29%, 24%, and 15%, respectively. Overall response rates were 56%, 54%, and 38%, respectively. Median PFS was not reached in any arm, exceeding 24 months.

Treatment was generally well tolerated, said Dr. Hofmeister. The most common treatment-related adverse effects were fatigue, cough, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and insomnia. Hypertension and hyperglycemia were the most common grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events, affecting up to 5% of patients per arm. Fewer than 10% of patients in any arm developed treatment-emergent hematologic adverse events, and fewer than 5% developed grade 3-4 pneumonia or sepsis. There were three cases of a second primary malignancy, including one case of breast cancer and two cases of melanoma.

Rates of infusion-related reactions did not correlate with treatment duration. Grade 3-4 infusion-related reactions affected 0% to 3% of patients per arm. The sole death in this trial resulted from disease progression in a patient from the short treatment arm. “Taken together, efficacy and safety data support long dosing compared to intermediate and short dosing,” Dr. Hofmeister said.

The three arms were demographically similar. Patients tended to be white, in their late 50s to 60s, and to have ECOG scores of 0 with at least two risk factors for progression. About 70% had IgG disease and nearly half had less than 20% plasma cells in bone marrow.

Janssen, the maker of daratumumab, sponsored the trial. Dr. Hofmeister disclosed research funding from Janssen and research support, honoraria, and advisory relationships with Adaptive Biotechnologies, Thrasos, Celgene, Karyopharm, Takeda, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Hofmeister C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 510.

ATLANTA – Daratumumab monotherapy led to durable partial responses among intermediate to high-risk patients with smoldering multiple myeloma, according to results from the phase II CENTAURUS trial.

Although less than 5% of patients had complete responses, 27% had at least a very good partial response to long-term therapy (up to 20 treatment cycles lasting 8 weeks each), Craig C. Hofmeister, MD, of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The coprimary endpoint, median progression-free survival, exceeded 24 months in all dose cohorts, and was the longest when patients were treated longest.

Current guidelines recommend monitoring smoldering multiple myeloma every 3-6 months and treating only after patients progress. However, some experts pursue earlier treatment in the premalignant setting.

In CENTAURUS, 123 adults with smoldering multiple myeloma were randomly assigned to receive daratumumab (16 mg/kg IV) in 8-week cycles according to a long, intermediate, or short/intense schedule. The long schedule consisted of treatment weekly for cycle 1, every other week for cycles 2-3, monthly for cycles 4-7, and once every 8 weeks for up to 13 more cycles. The intermediate schedule consisted of treatment weekly in cycle 1 and every 8 weeks for up to 20 cycles. The short, intense schedule consisted of weekly treatment for 8 weeks (one cycle). Patients were followed for up to 4 years or until they progressed to multiple myeloma based on International Myeloma Working Group guidelines.

Over a median follow-up period of 15.8 months (range, 0 to 24 months), rates of complete response were 2% in the long treatment arm, 5% in the intermediate treatment arm, and 0% in the short treatment arm. Rates of at least very good partial response were 29%, 24%, and 15%, respectively. Overall response rates were 56%, 54%, and 38%, respectively. Median PFS was not reached in any arm, exceeding 24 months.

Treatment was generally well tolerated, said Dr. Hofmeister. The most common treatment-related adverse effects were fatigue, cough, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and insomnia. Hypertension and hyperglycemia were the most common grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events, affecting up to 5% of patients per arm. Fewer than 10% of patients in any arm developed treatment-emergent hematologic adverse events, and fewer than 5% developed grade 3-4 pneumonia or sepsis. There were three cases of a second primary malignancy, including one case of breast cancer and two cases of melanoma.

Rates of infusion-related reactions did not correlate with treatment duration. Grade 3-4 infusion-related reactions affected 0% to 3% of patients per arm. The sole death in this trial resulted from disease progression in a patient from the short treatment arm. “Taken together, efficacy and safety data support long dosing compared to intermediate and short dosing,” Dr. Hofmeister said.

The three arms were demographically similar. Patients tended to be white, in their late 50s to 60s, and to have ECOG scores of 0 with at least two risk factors for progression. About 70% had IgG disease and nearly half had less than 20% plasma cells in bone marrow.

Janssen, the maker of daratumumab, sponsored the trial. Dr. Hofmeister disclosed research funding from Janssen and research support, honoraria, and advisory relationships with Adaptive Biotechnologies, Thrasos, Celgene, Karyopharm, Takeda, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Hofmeister C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 510.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2017

Key clinical point: Single-agent daratumumab therapy was active and its safety profile was acceptable in patients with smoldering multiple myeloma.

Major finding: Rates of at least very good partial response were 29%, 24%, and 15% among patients who received long, intermediate, and short/intense treatment schedules, respectively. Median progression-free survival exceeded 24 months in all three arms.

Data source: CENTAURUS, a phase II trial of 123 patients with smoldering multiple myeloma.

Disclosures: Janssen sponsored the trial. Dr. Hofmeister disclosed research funding from Janssen and research support, honoraria, and advisory relationships with Adaptive Biotechnologies, Thrasos, Celgene, Karyopharm, Takeda, and other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Hofmeister C et al, ASH 2017, Abstract 510.

ERBB2 expression predicts pCR in HER2+ breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – Among patients receiving trastuzumab plus lapatinib neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive early breast cancer, amplification of ERBB2 was predictive of a pathologic complete response (pCR), according to findings presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

However, ERBB2 mRNA expression and PAM50-enriched HER2 better predicted pCR, said lead study author Cristos Sotiriou, MD, of the Breast Cancer Translational Research Laboratory at the Institut Jules Bordet in Belgium

High genomic instability was associated with a higher pCR rate in patients with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, but copy number alterations (CNAs) were not associated with event-free survival (EFS).

In the large phase 3 NeoALTTO trial, lapatinib combined with trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting nearly doubled the pCR rate as compared with either agent used alone. The 3-year EFS was also improved with dual HER2 blockage versus single HER2 therapy (84% for the combination, hazard ratio, 0.78; P = .33 vs. 78% for lapatinib alone and 76% for trastuzumab alone, HR, 1.06; P = .81 for both).

The researchers of this trial also found that pCR was a surrogate for long-term outcome.

“Expression of ERBB2, ESR1, and immune signatures were the main drivers of pCR,” said Dr. Sotiriou.

The main goal of the current study was to investigate the relevance of CNAs for pCR and EFS in this population. A total of 455 patients were enrolled in the NeoALTTO study, and of this cohort, 270 had tumor content that was sufficient to assay for CNAs. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and gene expression were also obtained and the genome instability index was calculated, and 184 samples were included in the final analysis.

Of the cancer genes, only ERBB2 was predictive of pCR.

A total of 159 recurrent CNA regions were identified. ERBB2 amplification was associated with high pCR (P = .0007), but less than ERBB2 expression, and it lost its significance after correcting for ERBB2 expression.

The genome instability index (GII) was defined as the “median absolute deviation of the normalized copy number” and independent of ERBB2 amplification, the pCR rate increased with the GII (P = .03.

Amplification of two regions on 6q23-24 was significantly associated with higher pCR (P = .00005 and P = .00087). One of the segments harbored 39 genes, some with an expression level that was also predictive of pCR. The 6q23-24 segment was associated with pCR in estrogen receptor–positive tumors only (interaction test P = .04).

After multiple testing correction, there were no amplified regions or genes found to be predictive of EFS.

“A novel amplified region on 6q23-24 was shown to be predictive of pCR, in particular for estrogen receptor–positive tumors,” said Dr. Sotiriou. “This may warrant further investigation.”

SOURCE: Sotiriou et al. SABCS Abstract GS1-04

SAN ANTONIO – Among patients receiving trastuzumab plus lapatinib neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive early breast cancer, amplification of ERBB2 was predictive of a pathologic complete response (pCR), according to findings presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

However, ERBB2 mRNA expression and PAM50-enriched HER2 better predicted pCR, said lead study author Cristos Sotiriou, MD, of the Breast Cancer Translational Research Laboratory at the Institut Jules Bordet in Belgium

High genomic instability was associated with a higher pCR rate in patients with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, but copy number alterations (CNAs) were not associated with event-free survival (EFS).

In the large phase 3 NeoALTTO trial, lapatinib combined with trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting nearly doubled the pCR rate as compared with either agent used alone. The 3-year EFS was also improved with dual HER2 blockage versus single HER2 therapy (84% for the combination, hazard ratio, 0.78; P = .33 vs. 78% for lapatinib alone and 76% for trastuzumab alone, HR, 1.06; P = .81 for both).

The researchers of this trial also found that pCR was a surrogate for long-term outcome.

“Expression of ERBB2, ESR1, and immune signatures were the main drivers of pCR,” said Dr. Sotiriou.

The main goal of the current study was to investigate the relevance of CNAs for pCR and EFS in this population. A total of 455 patients were enrolled in the NeoALTTO study, and of this cohort, 270 had tumor content that was sufficient to assay for CNAs. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and gene expression were also obtained and the genome instability index was calculated, and 184 samples were included in the final analysis.

Of the cancer genes, only ERBB2 was predictive of pCR.

A total of 159 recurrent CNA regions were identified. ERBB2 amplification was associated with high pCR (P = .0007), but less than ERBB2 expression, and it lost its significance after correcting for ERBB2 expression.

The genome instability index (GII) was defined as the “median absolute deviation of the normalized copy number” and independent of ERBB2 amplification, the pCR rate increased with the GII (P = .03.

Amplification of two regions on 6q23-24 was significantly associated with higher pCR (P = .00005 and P = .00087). One of the segments harbored 39 genes, some with an expression level that was also predictive of pCR. The 6q23-24 segment was associated with pCR in estrogen receptor–positive tumors only (interaction test P = .04).

After multiple testing correction, there were no amplified regions or genes found to be predictive of EFS.

“A novel amplified region on 6q23-24 was shown to be predictive of pCR, in particular for estrogen receptor–positive tumors,” said Dr. Sotiriou. “This may warrant further investigation.”

SOURCE: Sotiriou et al. SABCS Abstract GS1-04

SAN ANTONIO – Among patients receiving trastuzumab plus lapatinib neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive early breast cancer, amplification of ERBB2 was predictive of a pathologic complete response (pCR), according to findings presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

However, ERBB2 mRNA expression and PAM50-enriched HER2 better predicted pCR, said lead study author Cristos Sotiriou, MD, of the Breast Cancer Translational Research Laboratory at the Institut Jules Bordet in Belgium

High genomic instability was associated with a higher pCR rate in patients with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, but copy number alterations (CNAs) were not associated with event-free survival (EFS).

In the large phase 3 NeoALTTO trial, lapatinib combined with trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting nearly doubled the pCR rate as compared with either agent used alone. The 3-year EFS was also improved with dual HER2 blockage versus single HER2 therapy (84% for the combination, hazard ratio, 0.78; P = .33 vs. 78% for lapatinib alone and 76% for trastuzumab alone, HR, 1.06; P = .81 for both).

The researchers of this trial also found that pCR was a surrogate for long-term outcome.

“Expression of ERBB2, ESR1, and immune signatures were the main drivers of pCR,” said Dr. Sotiriou.

The main goal of the current study was to investigate the relevance of CNAs for pCR and EFS in this population. A total of 455 patients were enrolled in the NeoALTTO study, and of this cohort, 270 had tumor content that was sufficient to assay for CNAs. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and gene expression were also obtained and the genome instability index was calculated, and 184 samples were included in the final analysis.

Of the cancer genes, only ERBB2 was predictive of pCR.

A total of 159 recurrent CNA regions were identified. ERBB2 amplification was associated with high pCR (P = .0007), but less than ERBB2 expression, and it lost its significance after correcting for ERBB2 expression.

The genome instability index (GII) was defined as the “median absolute deviation of the normalized copy number” and independent of ERBB2 amplification, the pCR rate increased with the GII (P = .03.

Amplification of two regions on 6q23-24 was significantly associated with higher pCR (P = .00005 and P = .00087). One of the segments harbored 39 genes, some with an expression level that was also predictive of pCR. The 6q23-24 segment was associated with pCR in estrogen receptor–positive tumors only (interaction test P = .04).

After multiple testing correction, there were no amplified regions or genes found to be predictive of EFS.

“A novel amplified region on 6q23-24 was shown to be predictive of pCR, in particular for estrogen receptor–positive tumors,” said Dr. Sotiriou. “This may warrant further investigation.”

SOURCE: Sotiriou et al. SABCS Abstract GS1-04

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2017

Key clinical point: ERBB2 mRNA expression and PAM50-enriched HER2 better predicted pathologic complete response than did EEBB2 amplification.

Major finding: Of the cancer genes, only ERBB2 was predictive of pCR, and amplification of two regions on 6q23-24 was significantly associated with higher pCR (P = .00005 and P = .00087).

Data source: An analysis of the large phase 3 NeoALTTO trial, in which lapatinib was combined with trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting to investigate the relevance of copy number alterations on outcome.

Disclosures: The NeoALTTO trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Sotiriou did not make any disclosures.

Source: Sotiriou et al. SABCS Abstract GS1-04

HealthCare.gov enrollment for 2018 nearly doubled in final week

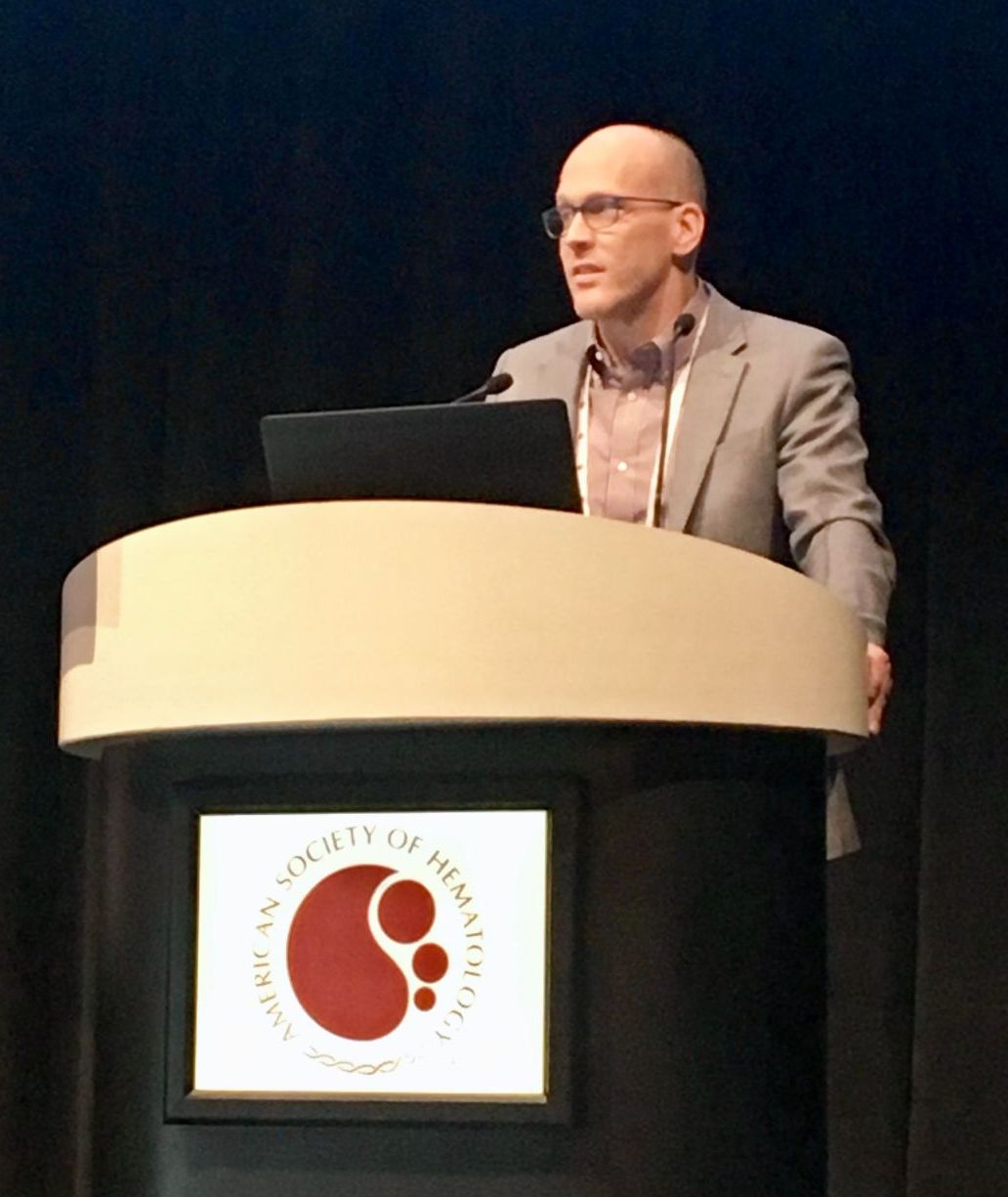

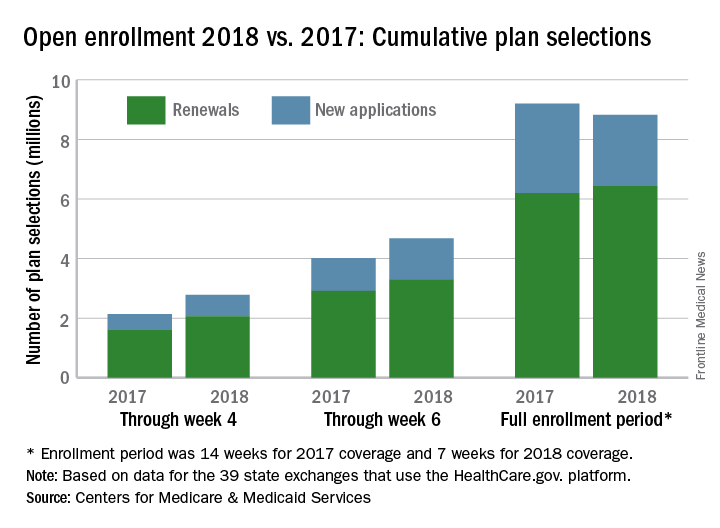

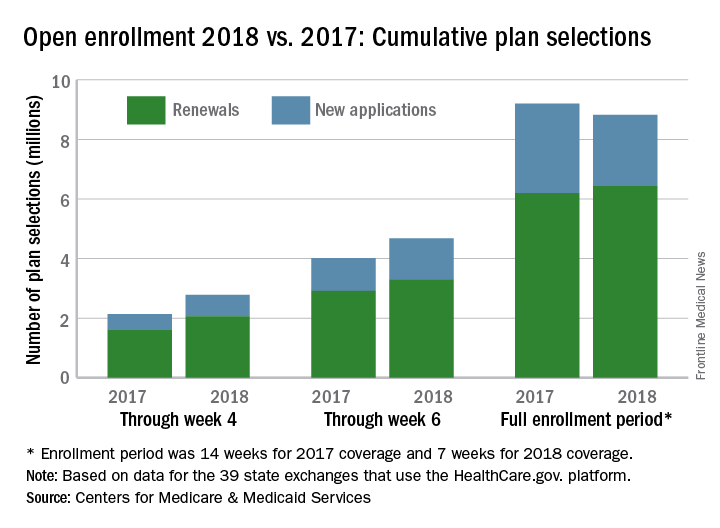

A busy final week of open enrollment at HealthCare.gov almost doubled the total number of health insurance plans selected and nearly equaled the total for last year’s much longer period, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

After the first 6 weeks of enrollment, the total number of plans selected for 2018 stood at 4.68 million. Just 1 week later, . That works out to 6.43 million plans selected by consumers who renewed their coverage on 1 of the 39 state exchanges that use the HealthCare.gov platform and 2.39 million plans selected by new consumers (those who did not have coverage in 2017), the CMS reported.

The CMS noted that the numbers for 2018 are estimates that represent plans selected and not the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.

SOURCE: CMS.gov Fact Sheet

A busy final week of open enrollment at HealthCare.gov almost doubled the total number of health insurance plans selected and nearly equaled the total for last year’s much longer period, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

After the first 6 weeks of enrollment, the total number of plans selected for 2018 stood at 4.68 million. Just 1 week later, . That works out to 6.43 million plans selected by consumers who renewed their coverage on 1 of the 39 state exchanges that use the HealthCare.gov platform and 2.39 million plans selected by new consumers (those who did not have coverage in 2017), the CMS reported.

The CMS noted that the numbers for 2018 are estimates that represent plans selected and not the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.

SOURCE: CMS.gov Fact Sheet

A busy final week of open enrollment at HealthCare.gov almost doubled the total number of health insurance plans selected and nearly equaled the total for last year’s much longer period, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

After the first 6 weeks of enrollment, the total number of plans selected for 2018 stood at 4.68 million. Just 1 week later, . That works out to 6.43 million plans selected by consumers who renewed their coverage on 1 of the 39 state exchanges that use the HealthCare.gov platform and 2.39 million plans selected by new consumers (those who did not have coverage in 2017), the CMS reported.

The CMS noted that the numbers for 2018 are estimates that represent plans selected and not the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.

SOURCE: CMS.gov Fact Sheet

FDA approves hydroxyurea for pediatric patients with sickle cell anemia

to reduce the frequency of painful crises and the need for blood transfusions, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 21.

This is the first FDA approval of hydroxyurea for use in pediatric sickle cell patients. The recommended initial dose is 20 mg/kg once daily but can be changed based on blood count levels, the agency said in a press release.

The most common adverse reactions to hydroxyurea, infections and neutropenia, occurred in less than 10% of patients. Hydroxyurea causes severe myelosuppression and should not be administered to patients with depressed bone marrow function.

Hydroxyurea is manufactured as Siklos by Addmedica. More information concerning hydroxyurea indications, dosing, and precautions can be found here.

SOURCE: FDA press release.

to reduce the frequency of painful crises and the need for blood transfusions, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 21.

This is the first FDA approval of hydroxyurea for use in pediatric sickle cell patients. The recommended initial dose is 20 mg/kg once daily but can be changed based on blood count levels, the agency said in a press release.

The most common adverse reactions to hydroxyurea, infections and neutropenia, occurred in less than 10% of patients. Hydroxyurea causes severe myelosuppression and should not be administered to patients with depressed bone marrow function.

Hydroxyurea is manufactured as Siklos by Addmedica. More information concerning hydroxyurea indications, dosing, and precautions can be found here.

SOURCE: FDA press release.

to reduce the frequency of painful crises and the need for blood transfusions, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 21.

This is the first FDA approval of hydroxyurea for use in pediatric sickle cell patients. The recommended initial dose is 20 mg/kg once daily but can be changed based on blood count levels, the agency said in a press release.

The most common adverse reactions to hydroxyurea, infections and neutropenia, occurred in less than 10% of patients. Hydroxyurea causes severe myelosuppression and should not be administered to patients with depressed bone marrow function.

Hydroxyurea is manufactured as Siklos by Addmedica. More information concerning hydroxyurea indications, dosing, and precautions can be found here.

SOURCE: FDA press release.

Length of stay shorter with admission to family medicine, not hospitalist, service

MONTREAL – When a family medicine teaching service provided hospital care for local patients, length of stay was almost a third shorter than when care was provided by the hospitalist internal medicine service at a large tertiary care hospital.

What made the difference in length of stay? “,” said Gregory Garrison, MD, of the department of family medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He noted that readmission rates weren’t higher for the patients cared for by the family medicine inpatient service.

The primary outcome measures were length of stay and readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, Dr. Garrison said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

A total of 3,125 admissions were seen for 2,138 unique patients. Most admissions (2,651; 84.8%) were for the family medicine service. Demographic characteristics and readmission rates were similar between admissions to the two services, but “hospitalist internal medicine patients were perhaps slightly sicker,” said Dr. Garrison. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 4 for the family medicine admissions and 5.6 for the hospitalist internal medicine admissions (P less than .001). Also, the patients admitted to the hospitalist service were slightly more likely to have had a previous hospital admission within the prior 12 months.

Examining the unadjusted data, Dr. Garrison and his colleagues found that the family medicine patients had a shorter length of stay, with a mean 2.5 days and a median 1.8 days, compared with the mean 3.8 days and median 2.7 days spent in hospital for the hospitalist internal medicine patients.

The difference remained significant after multivariable analysis to control for several potentially confounding factors, including patient demographics, prior health care utilization, disposition, readmissions, and Charlson comorbidity score.

The adjusted figures showed that length of stay was 31.8% longer for admissions to the hospitalist internal medicine service than for the family medicine service.

In discussion, Dr. Garrison said that he and his colleagues believe that the physicians, social workers, and clinical assistants who make up the family medicine service really understand the “outpatient resources that can be marshaled to help local patients with the transition from hospital to home.”

In practical terms, this can mean that a social worker knows which skilled nursing facilities are likely to accept a Friday admission, or that a physician understands community resources that can help an elderly patient return to her home with a little extra support, he said.

Another practicality, is that “the lack of a census cap on the family medicine inpatient service may incentivize rapid turnover,” he added.

Dr. Garrison reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32

MONTREAL – When a family medicine teaching service provided hospital care for local patients, length of stay was almost a third shorter than when care was provided by the hospitalist internal medicine service at a large tertiary care hospital.

What made the difference in length of stay? “,” said Gregory Garrison, MD, of the department of family medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He noted that readmission rates weren’t higher for the patients cared for by the family medicine inpatient service.

The primary outcome measures were length of stay and readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, Dr. Garrison said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

A total of 3,125 admissions were seen for 2,138 unique patients. Most admissions (2,651; 84.8%) were for the family medicine service. Demographic characteristics and readmission rates were similar between admissions to the two services, but “hospitalist internal medicine patients were perhaps slightly sicker,” said Dr. Garrison. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 4 for the family medicine admissions and 5.6 for the hospitalist internal medicine admissions (P less than .001). Also, the patients admitted to the hospitalist service were slightly more likely to have had a previous hospital admission within the prior 12 months.

Examining the unadjusted data, Dr. Garrison and his colleagues found that the family medicine patients had a shorter length of stay, with a mean 2.5 days and a median 1.8 days, compared with the mean 3.8 days and median 2.7 days spent in hospital for the hospitalist internal medicine patients.

The difference remained significant after multivariable analysis to control for several potentially confounding factors, including patient demographics, prior health care utilization, disposition, readmissions, and Charlson comorbidity score.

The adjusted figures showed that length of stay was 31.8% longer for admissions to the hospitalist internal medicine service than for the family medicine service.

In discussion, Dr. Garrison said that he and his colleagues believe that the physicians, social workers, and clinical assistants who make up the family medicine service really understand the “outpatient resources that can be marshaled to help local patients with the transition from hospital to home.”

In practical terms, this can mean that a social worker knows which skilled nursing facilities are likely to accept a Friday admission, or that a physician understands community resources that can help an elderly patient return to her home with a little extra support, he said.

Another practicality, is that “the lack of a census cap on the family medicine inpatient service may incentivize rapid turnover,” he added.

Dr. Garrison reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32

MONTREAL – When a family medicine teaching service provided hospital care for local patients, length of stay was almost a third shorter than when care was provided by the hospitalist internal medicine service at a large tertiary care hospital.

What made the difference in length of stay? “,” said Gregory Garrison, MD, of the department of family medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He noted that readmission rates weren’t higher for the patients cared for by the family medicine inpatient service.

The primary outcome measures were length of stay and readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, Dr. Garrison said at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

A total of 3,125 admissions were seen for 2,138 unique patients. Most admissions (2,651; 84.8%) were for the family medicine service. Demographic characteristics and readmission rates were similar between admissions to the two services, but “hospitalist internal medicine patients were perhaps slightly sicker,” said Dr. Garrison. The mean Charlson comorbidity score was 4 for the family medicine admissions and 5.6 for the hospitalist internal medicine admissions (P less than .001). Also, the patients admitted to the hospitalist service were slightly more likely to have had a previous hospital admission within the prior 12 months.

Examining the unadjusted data, Dr. Garrison and his colleagues found that the family medicine patients had a shorter length of stay, with a mean 2.5 days and a median 1.8 days, compared with the mean 3.8 days and median 2.7 days spent in hospital for the hospitalist internal medicine patients.

The difference remained significant after multivariable analysis to control for several potentially confounding factors, including patient demographics, prior health care utilization, disposition, readmissions, and Charlson comorbidity score.

The adjusted figures showed that length of stay was 31.8% longer for admissions to the hospitalist internal medicine service than for the family medicine service.

In discussion, Dr. Garrison said that he and his colleagues believe that the physicians, social workers, and clinical assistants who make up the family medicine service really understand the “outpatient resources that can be marshaled to help local patients with the transition from hospital to home.”

In practical terms, this can mean that a social worker knows which skilled nursing facilities are likely to accept a Friday admission, or that a physician understands community resources that can help an elderly patient return to her home with a little extra support, he said.

Another practicality, is that “the lack of a census cap on the family medicine inpatient service may incentivize rapid turnover,” he added.

Dr. Garrison reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32

REPORTING FROM NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point: Patients’ length of stay was shorter when they were cared for by family medicine doctors and not hospitalists.

Major finding: After multivariable analysis, the adjusted length of stay was 31.8% longer for patients on the hospitalist service than on the family medicine inpatient service.

Study details: A retrospective review of records from 3,125 admissions of 2,138 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Garrison reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

Source: Garrison G et al. NAPCRG 2017 Abstract AE32.

Study identifies predictors of acquired von Willebrand disease

ATLANTA – Waldenström macroglobulinemia can present as acquired von Willebrand disease (VWD), and when it does, the finding strongly correlates with high serum IgM levels and the presence of CXCR4 mutations, according to the results of a large, single-center retrospective study.

Further, successfully treating Waldenström macroglobulinemia often resolves acquired VWD, and the depth of treatment response predicts the degree of improvement, Jorge J. Castillo, MD, and his associates wrote in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Acquired VWD is an uncommon, poorly understood presentation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Because affected patients require treatment, better characterizing this subgroup is important, the investigators noted.

At the Bing Center for Waldenström Macroglobulinemia at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the researchers retrospectively studied 320 individuals with newly diagnosed Waldenström macroglobulinemia and used logistic regression analysis to seek predictors of acquired VWD, which they evaluated by measuring levels of VW factor antigen, VW factor activity, and factor VIII. Levels under 30% were considered VWD and levels between 30% and 50% were considered low-level VWD.

In all, 49 individuals had acquired VWD while 271 patients did not. These two groups were similar in terms of age, sex, hemoglobin level, platelet count, and bone marrow involvement. However, 45% of patients with acquired VWD had serum IgM levels above 6,000 mg/dL versus 6% of patients without acquired VWD (P less than .001), and 47% of patients with acquired VWD had serum IgM levels between 3,000 and 5,999 versus 31% of patients without acquired VWD (P less than .001). Also, 77% of patients with acquired VWD tested positive for CXCR4 mutation versus 37% of patients without acquired VWD (P less than .001).

A significantly higher proportion of patients without acquired VWD had white blood cell concentrations above 6,000/mcL (29% vs. 50%; P = .006). This finding lost statistical significance in the logistic regression model, but all the other variables remained significantly associated. Serum IgM levels above 6,000 mg/dL conferred a 55-fold increase in the odds of having acquired VWD (95% confidence interval, 17-177; P less than .001), and serum IgM levels between 3,000 and 5,999 mg/dL led to an 11-fold increase in these odds (95% CI, 4-34). The presence of CXCR4 mutations was associated with a sixfold increased odds of acquired VWD (95% CI, 2-15). The P value for each of these three associations was at or below .001.

Therapy for Waldenström macroglobulinemia led to statistically significant increases in levels of factor VIII, VW factor antigen, and VW factor activity (P less than .001) and the median of each level improved by at least 35% after treatment. After treatment, 78% of patients with acquired VWD had levels of all three measures above 50% (versus 0% before treatment; P less than .001). Patients with acquired VWD with the best responses to treatment had about a 90% decrease in IgM levels, while those with a partial response had about a two-thirds decrease and patients with stable disease had about a 20% decrease. A linear regression model confirmed that depth of treatment response, based on change in IgM level, correlated with degree of improvement in VWD – that is, the extent of improvement in levels of VW factor antigen, VW factor activity, and factor VIII.

No external funding sources were reported. Dr. Castillo disclosed consulting ties and research funding from Pharmacyclics and Janssen, and research funding from Millenium and Abbvie.

SOURCE: Castillo J, et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 1088.

ATLANTA – Waldenström macroglobulinemia can present as acquired von Willebrand disease (VWD), and when it does, the finding strongly correlates with high serum IgM levels and the presence of CXCR4 mutations, according to the results of a large, single-center retrospective study.

Further, successfully treating Waldenström macroglobulinemia often resolves acquired VWD, and the depth of treatment response predicts the degree of improvement, Jorge J. Castillo, MD, and his associates wrote in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Acquired VWD is an uncommon, poorly understood presentation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Because affected patients require treatment, better characterizing this subgroup is important, the investigators noted.

At the Bing Center for Waldenström Macroglobulinemia at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the researchers retrospectively studied 320 individuals with newly diagnosed Waldenström macroglobulinemia and used logistic regression analysis to seek predictors of acquired VWD, which they evaluated by measuring levels of VW factor antigen, VW factor activity, and factor VIII. Levels under 30% were considered VWD and levels between 30% and 50% were considered low-level VWD.

In all, 49 individuals had acquired VWD while 271 patients did not. These two groups were similar in terms of age, sex, hemoglobin level, platelet count, and bone marrow involvement. However, 45% of patients with acquired VWD had serum IgM levels above 6,000 mg/dL versus 6% of patients without acquired VWD (P less than .001), and 47% of patients with acquired VWD had serum IgM levels between 3,000 and 5,999 versus 31% of patients without acquired VWD (P less than .001). Also, 77% of patients with acquired VWD tested positive for CXCR4 mutation versus 37% of patients without acquired VWD (P less than .001).

A significantly higher proportion of patients without acquired VWD had white blood cell concentrations above 6,000/mcL (29% vs. 50%; P = .006). This finding lost statistical significance in the logistic regression model, but all the other variables remained significantly associated. Serum IgM levels above 6,000 mg/dL conferred a 55-fold increase in the odds of having acquired VWD (95% confidence interval, 17-177; P less than .001), and serum IgM levels between 3,000 and 5,999 mg/dL led to an 11-fold increase in these odds (95% CI, 4-34). The presence of CXCR4 mutations was associated with a sixfold increased odds of acquired VWD (95% CI, 2-15). The P value for each of these three associations was at or below .001.

Therapy for Waldenström macroglobulinemia led to statistically significant increases in levels of factor VIII, VW factor antigen, and VW factor activity (P less than .001) and the median of each level improved by at least 35% after treatment. After treatment, 78% of patients with acquired VWD had levels of all three measures above 50% (versus 0% before treatment; P less than .001). Patients with acquired VWD with the best responses to treatment had about a 90% decrease in IgM levels, while those with a partial response had about a two-thirds decrease and patients with stable disease had about a 20% decrease. A linear regression model confirmed that depth of treatment response, based on change in IgM level, correlated with degree of improvement in VWD – that is, the extent of improvement in levels of VW factor antigen, VW factor activity, and factor VIII.

No external funding sources were reported. Dr. Castillo disclosed consulting ties and research funding from Pharmacyclics and Janssen, and research funding from Millenium and Abbvie.

SOURCE: Castillo J, et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 1088.

ATLANTA – Waldenström macroglobulinemia can present as acquired von Willebrand disease (VWD), and when it does, the finding strongly correlates with high serum IgM levels and the presence of CXCR4 mutations, according to the results of a large, single-center retrospective study.

Further, successfully treating Waldenström macroglobulinemia often resolves acquired VWD, and the depth of treatment response predicts the degree of improvement, Jorge J. Castillo, MD, and his associates wrote in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Acquired VWD is an uncommon, poorly understood presentation of Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Because affected patients require treatment, better characterizing this subgroup is important, the investigators noted.