User login

Typhoid isn’t covered??!!

My wife and I decided to visit Morocco, to test the maxim that my fellow columnist Joe Eastern often cites: The words you won’t say on your deathbed are, “If only I had spent more time at the office.”

Though I’m not convinced he’s right about that – he’s never even seen my office – I thought I’d give being away a try. My office manager comes from near Marrakesh. While bound for Morocco, we could check out her hometown, even if there is no obvious tax angle.

As I contemplated exotic travel, the first things that came to mind of course were what rare diseases I might catch, which vaccines could prevent them, and how to get insurance to pay for getting immunized. Alexa helped me find CDC recommendations for immunizations for travel to Morocco, which included:

• Typhoid ... contaminated food or water.

• Hepatitis A ... contaminated food or water.

• Hepatitis B ... contaminated body fluids (sex, needles, etc.).

• Cholera ... contaminated food or water.

• Rabies ... infected animals.

• Influenza ... airborne droplets.

This trip was indeed starting to sound like an awful lot of fun.

My PCP called in several of the relevant vaccines to my local pharmacy, who informed me that typhoid vaccine is not covered by my health insurance. This spurred the following (somewhat embellished) dialogue with my insurer:

“Why is typhoid not covered?”

“Contractual exclusion. We don’t cover anything starting with “typ-,” including typhoid, typhus, typical, and typographic.”

“Do you cover bubonic plague?”

“Only for high-risk travel.”

“Such as?”

“Such as if you travel to Europe during the 14th century.”

“How about Hepatitis B and rabies?”

“That would depend.”

“On what?”

“On whether you plan to have sex with rabid bats, or rabid sex with placid bats.”

“I wouldn’t say I have plans. But, you know, in the moment ...”

“Sorry, not covered.”

“How about cholera?”

“Have you ever been threatened by cholera?

“Not exactly. But I did have a cranky uncle. When he was irritated, he often said, ‘May cholera grab you!’ ”

“You’re not covered. Your uncle might be.”

“We’ve decided on a side trip to Tanzania. As long as we’re already in Africa ...”

“Do you suffer from Sleeping Sickness?”

“Only at Grand Rounds.”

“We do cover eflornithine, but there is a problem ...”

“What problem?”

“Our only eflornithine manufacturing facility is in Bangladesh, where it takes up two floors of a factory that also makes designer jeans. That factory is closed for safety and child-labor violations.”

“For how long?”

“Indefinitely”

“Then what can I do?”

“You can apply eflornithine cream for your Sleeping Sickness and hope for the best.”

“Eflornithine cream?”

“Vaniqa. It may not help your sleeping symptoms, but you’ll need fewer haircuts.”

“Oh, thanks. What about River Blindness? Do you cover ivermectin?”

“Only if the preferred formulary alternatives have been exhausted.”

“What are those?”

“Metronidazole and azelaic acid.”

“Hold on! Are you looking at the page for onchocerciasis or the one for rosacea?”

“Yes. Did Montezuma ever make it to Morocco?”

“I don’t have that information. You’ll have to ask Alexa. Anything else?”

“No, I’m all set. Just remind me what you said about bats?”

In the end a family situation came up, and we had to cancel our trip. Instead, we watched the movie “Casablanca.” That is an excellent movie, with many pungent and memorable lines. Not only that but watching it does not cause jet lag.

As for the typhoid vaccine, in the end, it was not covered by insurance. Nevertheless, I haven’t had a bit of typhoid, so the vaccine seems to be working very well.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

My wife and I decided to visit Morocco, to test the maxim that my fellow columnist Joe Eastern often cites: The words you won’t say on your deathbed are, “If only I had spent more time at the office.”

Though I’m not convinced he’s right about that – he’s never even seen my office – I thought I’d give being away a try. My office manager comes from near Marrakesh. While bound for Morocco, we could check out her hometown, even if there is no obvious tax angle.

As I contemplated exotic travel, the first things that came to mind of course were what rare diseases I might catch, which vaccines could prevent them, and how to get insurance to pay for getting immunized. Alexa helped me find CDC recommendations for immunizations for travel to Morocco, which included:

• Typhoid ... contaminated food or water.

• Hepatitis A ... contaminated food or water.

• Hepatitis B ... contaminated body fluids (sex, needles, etc.).

• Cholera ... contaminated food or water.

• Rabies ... infected animals.

• Influenza ... airborne droplets.

This trip was indeed starting to sound like an awful lot of fun.

My PCP called in several of the relevant vaccines to my local pharmacy, who informed me that typhoid vaccine is not covered by my health insurance. This spurred the following (somewhat embellished) dialogue with my insurer:

“Why is typhoid not covered?”

“Contractual exclusion. We don’t cover anything starting with “typ-,” including typhoid, typhus, typical, and typographic.”

“Do you cover bubonic plague?”

“Only for high-risk travel.”

“Such as?”

“Such as if you travel to Europe during the 14th century.”

“How about Hepatitis B and rabies?”

“That would depend.”

“On what?”

“On whether you plan to have sex with rabid bats, or rabid sex with placid bats.”

“I wouldn’t say I have plans. But, you know, in the moment ...”

“Sorry, not covered.”

“How about cholera?”

“Have you ever been threatened by cholera?

“Not exactly. But I did have a cranky uncle. When he was irritated, he often said, ‘May cholera grab you!’ ”

“You’re not covered. Your uncle might be.”

“We’ve decided on a side trip to Tanzania. As long as we’re already in Africa ...”

“Do you suffer from Sleeping Sickness?”

“Only at Grand Rounds.”

“We do cover eflornithine, but there is a problem ...”

“What problem?”

“Our only eflornithine manufacturing facility is in Bangladesh, where it takes up two floors of a factory that also makes designer jeans. That factory is closed for safety and child-labor violations.”

“For how long?”

“Indefinitely”

“Then what can I do?”

“You can apply eflornithine cream for your Sleeping Sickness and hope for the best.”

“Eflornithine cream?”

“Vaniqa. It may not help your sleeping symptoms, but you’ll need fewer haircuts.”

“Oh, thanks. What about River Blindness? Do you cover ivermectin?”

“Only if the preferred formulary alternatives have been exhausted.”

“What are those?”

“Metronidazole and azelaic acid.”

“Hold on! Are you looking at the page for onchocerciasis or the one for rosacea?”

“Yes. Did Montezuma ever make it to Morocco?”

“I don’t have that information. You’ll have to ask Alexa. Anything else?”

“No, I’m all set. Just remind me what you said about bats?”

In the end a family situation came up, and we had to cancel our trip. Instead, we watched the movie “Casablanca.” That is an excellent movie, with many pungent and memorable lines. Not only that but watching it does not cause jet lag.

As for the typhoid vaccine, in the end, it was not covered by insurance. Nevertheless, I haven’t had a bit of typhoid, so the vaccine seems to be working very well.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

My wife and I decided to visit Morocco, to test the maxim that my fellow columnist Joe Eastern often cites: The words you won’t say on your deathbed are, “If only I had spent more time at the office.”

Though I’m not convinced he’s right about that – he’s never even seen my office – I thought I’d give being away a try. My office manager comes from near Marrakesh. While bound for Morocco, we could check out her hometown, even if there is no obvious tax angle.

As I contemplated exotic travel, the first things that came to mind of course were what rare diseases I might catch, which vaccines could prevent them, and how to get insurance to pay for getting immunized. Alexa helped me find CDC recommendations for immunizations for travel to Morocco, which included:

• Typhoid ... contaminated food or water.

• Hepatitis A ... contaminated food or water.

• Hepatitis B ... contaminated body fluids (sex, needles, etc.).

• Cholera ... contaminated food or water.

• Rabies ... infected animals.

• Influenza ... airborne droplets.

This trip was indeed starting to sound like an awful lot of fun.

My PCP called in several of the relevant vaccines to my local pharmacy, who informed me that typhoid vaccine is not covered by my health insurance. This spurred the following (somewhat embellished) dialogue with my insurer:

“Why is typhoid not covered?”

“Contractual exclusion. We don’t cover anything starting with “typ-,” including typhoid, typhus, typical, and typographic.”

“Do you cover bubonic plague?”

“Only for high-risk travel.”

“Such as?”

“Such as if you travel to Europe during the 14th century.”

“How about Hepatitis B and rabies?”

“That would depend.”

“On what?”

“On whether you plan to have sex with rabid bats, or rabid sex with placid bats.”

“I wouldn’t say I have plans. But, you know, in the moment ...”

“Sorry, not covered.”

“How about cholera?”

“Have you ever been threatened by cholera?

“Not exactly. But I did have a cranky uncle. When he was irritated, he often said, ‘May cholera grab you!’ ”

“You’re not covered. Your uncle might be.”

“We’ve decided on a side trip to Tanzania. As long as we’re already in Africa ...”

“Do you suffer from Sleeping Sickness?”

“Only at Grand Rounds.”

“We do cover eflornithine, but there is a problem ...”

“What problem?”

“Our only eflornithine manufacturing facility is in Bangladesh, where it takes up two floors of a factory that also makes designer jeans. That factory is closed for safety and child-labor violations.”

“For how long?”

“Indefinitely”

“Then what can I do?”

“You can apply eflornithine cream for your Sleeping Sickness and hope for the best.”

“Eflornithine cream?”

“Vaniqa. It may not help your sleeping symptoms, but you’ll need fewer haircuts.”

“Oh, thanks. What about River Blindness? Do you cover ivermectin?”

“Only if the preferred formulary alternatives have been exhausted.”

“What are those?”

“Metronidazole and azelaic acid.”

“Hold on! Are you looking at the page for onchocerciasis or the one for rosacea?”

“Yes. Did Montezuma ever make it to Morocco?”

“I don’t have that information. You’ll have to ask Alexa. Anything else?”

“No, I’m all set. Just remind me what you said about bats?”

In the end a family situation came up, and we had to cancel our trip. Instead, we watched the movie “Casablanca.” That is an excellent movie, with many pungent and memorable lines. Not only that but watching it does not cause jet lag.

As for the typhoid vaccine, in the end, it was not covered by insurance. Nevertheless, I haven’t had a bit of typhoid, so the vaccine seems to be working very well.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Tau imaging predicts looming cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly

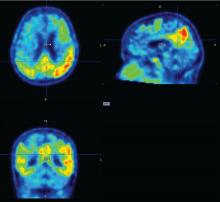

BOSTON – Progressive tau accumulation in the temporal lobe of cognitively normal older adults was associated with cognitive decline over time in a prospective, longitudinal study presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

This track of cognitive impairment following tau pathology in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) population suggests two roles for serial positron emission tomography (PET) scans with a tau binding agent, Bernard Hanseeuw, MD, PhD, said at the meeting. In the near future, they could be used to track therapeutic response in clinical trials. Farther out, if future validation studies confirm these preliminary results, they might be a useful clinical tool for predicting how fast an individual Alzheimer’s patient will progress, he said in an interview.

Serial tau scans, however, would, he said.

“Every patient with Alzheimer’s disease is different, with a different disease course. Amyloid scans can tell us if someone is on the wrong path, but tau scans could tell us how fast they are going. If you have Alzheimer’s, it’s important to know if you may not be able to live in your own home in a year. With tau PET, we could track the disease and predict how fast it might evolve. That is very clinically relevant,” said Dr. Hanseeuw.

Tau imaging remains investigational only. Several tau imaging agents are being developed, but none has yet been approved in the United States or in Europe.

To investigate the correlation of tau and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s, Dr. Hanseeuw examined serial tau and amyloid PET scans conducted on 60 clinically normal older adults with a mean age of 75 years. About one-third of the cohort was positive for the APOE4 allele. All of them had a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and a mean Mini-Mental State Exam score of at least 27. They also scored in the normal range on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Mini-Mental State Exam, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and Logical Memory IIA Delayed Recall, and correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain.

The study included up to 4 years of data on cognition and amyloid PET imaging, and up to 3 years of tau PET imaging data. The investigators assessed amyloid as a whole-brain aggregate and tau in the bilateral inferior temporal neocortex. “This is where the change is most happening in patients, and it’s a place where relatively few normal elderly would have tau,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. All of the analyses controlled for age, sex, and years of education.

Baseline amyloid levels were low in 36 participants and high in 24. At least some tau was present in all of the subjects. This is not an unexpected finding, since tau accumulates with age, Dr. Hanseeuw said. Over the study period, six subjects progressed to a CDR of 0.5 – a rating consistent with mild cognitive impairment. At baseline, high tau and high amyloid levels were both associated with a progressive decline in PACC scores in the following years. However, the rate of change in tau predicted change in cognition better than did the baseline measurements. In contrast, the rate of change in amyloid was not associated with cognitive decline.

“What is interesting here is that tau changed four times faster than amyloid,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. “The average subject needed 5 years to change 1 standard deviation in tau, but would have needed 20 years to change 1 standard deviation in amyloid.”

Fast-changing outcomes are important to accelerate drug assessment in clinical trials. Currently, it takes 3-5 years to conduct most anti-AD trials, he added.

Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Progressive tau accumulation in the temporal lobe of cognitively normal older adults was associated with cognitive decline over time in a prospective, longitudinal study presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

This track of cognitive impairment following tau pathology in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) population suggests two roles for serial positron emission tomography (PET) scans with a tau binding agent, Bernard Hanseeuw, MD, PhD, said at the meeting. In the near future, they could be used to track therapeutic response in clinical trials. Farther out, if future validation studies confirm these preliminary results, they might be a useful clinical tool for predicting how fast an individual Alzheimer’s patient will progress, he said in an interview.

Serial tau scans, however, would, he said.

“Every patient with Alzheimer’s disease is different, with a different disease course. Amyloid scans can tell us if someone is on the wrong path, but tau scans could tell us how fast they are going. If you have Alzheimer’s, it’s important to know if you may not be able to live in your own home in a year. With tau PET, we could track the disease and predict how fast it might evolve. That is very clinically relevant,” said Dr. Hanseeuw.

Tau imaging remains investigational only. Several tau imaging agents are being developed, but none has yet been approved in the United States or in Europe.

To investigate the correlation of tau and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s, Dr. Hanseeuw examined serial tau and amyloid PET scans conducted on 60 clinically normal older adults with a mean age of 75 years. About one-third of the cohort was positive for the APOE4 allele. All of them had a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and a mean Mini-Mental State Exam score of at least 27. They also scored in the normal range on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Mini-Mental State Exam, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and Logical Memory IIA Delayed Recall, and correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain.

The study included up to 4 years of data on cognition and amyloid PET imaging, and up to 3 years of tau PET imaging data. The investigators assessed amyloid as a whole-brain aggregate and tau in the bilateral inferior temporal neocortex. “This is where the change is most happening in patients, and it’s a place where relatively few normal elderly would have tau,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. All of the analyses controlled for age, sex, and years of education.

Baseline amyloid levels were low in 36 participants and high in 24. At least some tau was present in all of the subjects. This is not an unexpected finding, since tau accumulates with age, Dr. Hanseeuw said. Over the study period, six subjects progressed to a CDR of 0.5 – a rating consistent with mild cognitive impairment. At baseline, high tau and high amyloid levels were both associated with a progressive decline in PACC scores in the following years. However, the rate of change in tau predicted change in cognition better than did the baseline measurements. In contrast, the rate of change in amyloid was not associated with cognitive decline.

“What is interesting here is that tau changed four times faster than amyloid,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. “The average subject needed 5 years to change 1 standard deviation in tau, but would have needed 20 years to change 1 standard deviation in amyloid.”

Fast-changing outcomes are important to accelerate drug assessment in clinical trials. Currently, it takes 3-5 years to conduct most anti-AD trials, he added.

Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Progressive tau accumulation in the temporal lobe of cognitively normal older adults was associated with cognitive decline over time in a prospective, longitudinal study presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

This track of cognitive impairment following tau pathology in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) population suggests two roles for serial positron emission tomography (PET) scans with a tau binding agent, Bernard Hanseeuw, MD, PhD, said at the meeting. In the near future, they could be used to track therapeutic response in clinical trials. Farther out, if future validation studies confirm these preliminary results, they might be a useful clinical tool for predicting how fast an individual Alzheimer’s patient will progress, he said in an interview.

Serial tau scans, however, would, he said.

“Every patient with Alzheimer’s disease is different, with a different disease course. Amyloid scans can tell us if someone is on the wrong path, but tau scans could tell us how fast they are going. If you have Alzheimer’s, it’s important to know if you may not be able to live in your own home in a year. With tau PET, we could track the disease and predict how fast it might evolve. That is very clinically relevant,” said Dr. Hanseeuw.

Tau imaging remains investigational only. Several tau imaging agents are being developed, but none has yet been approved in the United States or in Europe.

To investigate the correlation of tau and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s, Dr. Hanseeuw examined serial tau and amyloid PET scans conducted on 60 clinically normal older adults with a mean age of 75 years. About one-third of the cohort was positive for the APOE4 allele. All of them had a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and a mean Mini-Mental State Exam score of at least 27. They also scored in the normal range on the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) test. This relatively new cognitive scale is an increasingly popular item in clinical trials. The PACC is a composite of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Mini-Mental State Exam, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, and Logical Memory IIA Delayed Recall, and correlates well with amyloid accumulation in the brain.

The study included up to 4 years of data on cognition and amyloid PET imaging, and up to 3 years of tau PET imaging data. The investigators assessed amyloid as a whole-brain aggregate and tau in the bilateral inferior temporal neocortex. “This is where the change is most happening in patients, and it’s a place where relatively few normal elderly would have tau,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. All of the analyses controlled for age, sex, and years of education.

Baseline amyloid levels were low in 36 participants and high in 24. At least some tau was present in all of the subjects. This is not an unexpected finding, since tau accumulates with age, Dr. Hanseeuw said. Over the study period, six subjects progressed to a CDR of 0.5 – a rating consistent with mild cognitive impairment. At baseline, high tau and high amyloid levels were both associated with a progressive decline in PACC scores in the following years. However, the rate of change in tau predicted change in cognition better than did the baseline measurements. In contrast, the rate of change in amyloid was not associated with cognitive decline.

“What is interesting here is that tau changed four times faster than amyloid,” Dr. Hanseeuw said. “The average subject needed 5 years to change 1 standard deviation in tau, but would have needed 20 years to change 1 standard deviation in amyloid.”

Fast-changing outcomes are important to accelerate drug assessment in clinical trials. Currently, it takes 3-5 years to conduct most anti-AD trials, he added.

Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM CTAD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Tau levels changed twice as fast as cognition, suggesting that the protein is a significant marker of future cognitive change.

Data source: A prospective, longitudinal study of 60 cognitively normal subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Hanseeuw had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Hanseeuw B et al. CTAD 2017 Abstract OC2.

Think before you Tweet: Social media guidelines for surgeons aim to prevent Internet regret

Think before you tweet. That’s what surgeons should remember before they express themselves on social media.

Anger and frustration can prompt ill-advised social media postings that have a big potential for blowback, Heather J. Logghe, MD, FACS, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. But so can enthusiasm about posting about a new device or procedure, a fascination with a difficult case, the sense of relief that a patient made it though a harrowing period, or even just the simple joy of tossing back a beer or two with pals at the local watering hole (J Am Coll Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.022).

“In a survey of 48 state medical boards, 44 (92%) reported online-related misbehavior with serious disciplinary consequences leading to license restriction, suspension, or revocation. A 2011 study of ‘Physicians on Twitter’ revealed that 10% of the physicians sampled had tweeted potential patient privacy violations. A 2014 study of publicly available Facebook profiles of 319 Midwest residents found 14% had ‘potentially unprofessional content’ and 12.2% had ‘clearly unprofessional’ content, the latter including references to binge drinking, sexually suggestive photos, and HIPAA violations.”

Dr. Logghe, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, is a member of the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS’s) social media committee tasked with creating practice recommendations for clinicians’ use of social media. Conducting a literature review was the first step to creating a surgeon-specific document, and the team found seven online behavior guidelines directed at physicians. Groups authoring these papers included the American Medical Association, the Federation of State Medical Boards, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and several international groups.

Dr. Logghe and her colleagues reviewed each one, synthesized the information, and created a practice recommendation statement specific to the ACS. While not encoded in any professional ethics requirements, “Best Practices for Surgeons’ Social Media Use: Statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons” does lay out some common, potentially problematic scenarios and offers some suggestions about how to avoid Internet regret.

Everything discussed in the paper revolves around maintaining a decorous public persona. Professionalism on and off the clock is a key tenet of the recommendations. Definitions of key terms like “professionalism” are an important basis for any practice guideline, but sometimes concepts are not easy to define, the team wrote. “Perhaps the limitation most difficult to address in any formalized guideline is the necessary subjectivity in interpreting what is ‘appropriate’ or ‘professional’ online – or in any other setting,” the authors wrote. The ACS Code of Professional Conduct does not explicitly define either of those terms or discuss the appearance of unprofessional behavior.

In the absence of a plain-and-simple definition, the authors attempted to couch the social media recommendations in terms of ACS’s commitment to maintaining the patient trust. It urges surgeons to “avoid even the appearance of impropriety.”

The practice recommendations touch on a number of areas that are potentially problematic for surgeons, including confidentiality, financial conflicts, collegial support, and general social responsibility.

Confidentiality

Maintaining privacy is more than a courtesy to patients: It’s a federally mandated law with serious punitive repercussions if violated. Blogs, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook offer a vast potential for sharing information with and educating the public, but postings can also easily violate HIPPA standards, the team wrote.

“In general, most social media platforms are not HIPPA-compliant,” no matter how the privacy settings are adjusted. These modes of communication are never appropriate for patient-physician communication: They can’t be archived in an electronic health record, and it is ill advised to give any medical advice by using these channels.

Discussing a particular case online, even with the usual defining details omitted, can be a bad idea.“Simply de-identifying patient information may not be sufficient. When posting information online, one must be cognizant of the context of other information available online. Such information includes the poster’s place of employment, news media, and publicly available vital statistics. Therefore even when posting general comments about hospital events, surgical cases, or patients under one’s care, it is essential to consider the sum of information available to the reader, rather than simply the information shared in the isolated post.”

Employment

Most employers have social media guidelines and don’t take kindly to violations – which can affect both current and future job postings. “A strong social media presence can be of benefit to one’s employer, [but] content that portrays a surgeon in an unprofessional or controversial light can be detrimental and even career-damaging.”

This reaches beyond professional communications online and deep into a surgeon’s personal life, the team noted, so exercise caution when “friending.”

“While this practice is inevitable, surgeons should be aware of potential conflicts. Connecting with or accepting friend requests from some but not all coworkers or coresidents could be interpreted as favoritism and may create a problematic work relationship. … Surgeons should consider primarily connecting with coworkers on professional websites if they have little contact with them outside the workplace.”

As for friending patients – just don’t, for both your sake and theirs. “Accepting a patient’s Facebook friend request may allow them access to events, details, and commentary not traditionally appropriate for the patient-physician relationship. Accepting such requests is strongly discouraged. If concerned about appearing rude or rejecting a patient’s request to be Facebook friends, the patient can be referred to society guidelines or best practices such as these.” One helpful alternative to such a request may be to invite patients to follow a practice website or other professional page.

Conflicts of interest

Online friends might not require disclosures when a surgeon posts about an exciting procedure or piece of equipment, such as whether there is a financial interest in doing so, but it’s important to be proactive. “As always, it is the physician’s responsibility to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. If it is not feasible to include a relevant conflict of interest within a post, the post should not be made.”

Defamation

Irritated about a colleague? Keep it to yourself – especially if you’ve had a beer. “It is never appropriate to post derogatory comments about patients or colleagues. Surgeons should be careful not to post in anger or under the influence of any substance. Statements about a colleague’s abilities, experience, or outcomes intended in jest may be appropriate for the surgeon’s lounge, yet entirely inappropriate for public consumption. Again, the ‘pause-before-posting’ practice is likely to prevent regretful posts in this vein.”

Privacy and Permanence

The Internet goes everywhere and lasts forever. A snappy quote that’s funny at 2 a.m. might not seem so hilarious in the light of day – or even in the light of a day 5 years yet to come.

The delete key is a false friend, and that clever pseudonym you dreamed up is probably as crackable as the classic “Pa55word” password. “One should presume that all content posted online will remain there forever and may be seen by anyone. Again, ‘pause-before-posting’ is a recommended practice.”

Privacy settings should be viewed as an illusion, the team noted. In this era of face recognition and tagging, images carry just as much risk as words.

Collegial support

Maybe your mother was right when she said, “This is for your own good.” If a colleague’s postings are getting out of hand, a tactful heart-to-heart might be the best course of action. “As coined by Dr. Sarah Mansfield, ‘Looking after colleagues is an integral element of professional conduct.’ Surgeons who notice colleagues posting unprofessional content that could be damaging to both the colleague and the public’s trust in the profession should discreetly express their concern to the individual, who should then take any appropriate corrective actions. … If the action is in violation of the law or medical board regulations, it should be reported to the appropriate governing bodies.”

Physician, Google Thyself

The team acknowledged that an online presence is virtually a must for professional development. And even if you don’t create a web page, chances are your university or hospital has done it for you. The media is interested in your life, too, and may make mention of your activities – both positive or negative.

“To better understand and control this publicly accessible information, surgeons are encouraged to periodically self-audit themselves online and taking measures to ensure that the information present is accurate and professional.” Some professional service websites are more trustworthy than others. The team encouraged physicians to participate in the ACS professional pages, LinkedIn, Doximity, and ResearchGate.

Not rules – just recommendations

The team stressed that their recommendations aren’t meant to stifle personal expression. Instead, their aim is to prompt a more conscious use of what can be a very powerful tool for both self-expression and professional development.

“The authors recommend no punitive action based on a perceived ‘violation’ of these recommendations alone. While they refer to other guidelines, including laws such as HIPAA, that must be appropriately enforced, these best practices are intended to guide the practicing surgeon in the use of social media rather than act as regulations or encourage reprimand. Rather than encouraging a social media landscape as sterile as the operating theater, the authors hope these recommendations lead to conscious consideration of online behavior, to avoidance of preventable harm, and to recognition of others’ views of their posts.”

None of the authors reported any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Logghe HJ et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.022.

As Editor of the ACS Communities, I am thrilled to see the RAS paper of social media recommendations. We who did not grow up with a keyboard in our hands can learn valuable and career-saving lessons from our younger colleagues who have had a lifetime of experience with social media.

There’s nothing like social media to get your thoughts “out there,” but the other side of the sword is excellently described in this article. I have seen or had to intervene on each of the subjects mentioned in it while reading through the thousands of posts that the ACS Communities’ users have generated over the last three-and-a-half years. When sitting in front of a screen, we can easily lose sight of the fact that our comments are going out into the real world and how rapidly they might reflect back on us and affect friends, relatives, employers, patients, foreign governments, cultures vastly different from our own, and other breathing, feeling human beings – in short, the entire universe hears regardless of whether the site is “password protected.”

I urge everyone using social media to read these guidelines, laminate them, and put them in their wallets, purses, or somewhere else that’s handy. Being self-aware and insightful in your posts can do a world of good, but a lack thereof can result in an avalanche of harm to yourself or others.

Tyler G. Hughes, MD, FACS, is a clinical professor in the department of surgery and the director of medical education at the Kansas University in Salina, Kan., as well as a Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

As Editor of the ACS Communities, I am thrilled to see the RAS paper of social media recommendations. We who did not grow up with a keyboard in our hands can learn valuable and career-saving lessons from our younger colleagues who have had a lifetime of experience with social media.

There’s nothing like social media to get your thoughts “out there,” but the other side of the sword is excellently described in this article. I have seen or had to intervene on each of the subjects mentioned in it while reading through the thousands of posts that the ACS Communities’ users have generated over the last three-and-a-half years. When sitting in front of a screen, we can easily lose sight of the fact that our comments are going out into the real world and how rapidly they might reflect back on us and affect friends, relatives, employers, patients, foreign governments, cultures vastly different from our own, and other breathing, feeling human beings – in short, the entire universe hears regardless of whether the site is “password protected.”

I urge everyone using social media to read these guidelines, laminate them, and put them in their wallets, purses, or somewhere else that’s handy. Being self-aware and insightful in your posts can do a world of good, but a lack thereof can result in an avalanche of harm to yourself or others.

Tyler G. Hughes, MD, FACS, is a clinical professor in the department of surgery and the director of medical education at the Kansas University in Salina, Kan., as well as a Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

As Editor of the ACS Communities, I am thrilled to see the RAS paper of social media recommendations. We who did not grow up with a keyboard in our hands can learn valuable and career-saving lessons from our younger colleagues who have had a lifetime of experience with social media.

There’s nothing like social media to get your thoughts “out there,” but the other side of the sword is excellently described in this article. I have seen or had to intervene on each of the subjects mentioned in it while reading through the thousands of posts that the ACS Communities’ users have generated over the last three-and-a-half years. When sitting in front of a screen, we can easily lose sight of the fact that our comments are going out into the real world and how rapidly they might reflect back on us and affect friends, relatives, employers, patients, foreign governments, cultures vastly different from our own, and other breathing, feeling human beings – in short, the entire universe hears regardless of whether the site is “password protected.”

I urge everyone using social media to read these guidelines, laminate them, and put them in their wallets, purses, or somewhere else that’s handy. Being self-aware and insightful in your posts can do a world of good, but a lack thereof can result in an avalanche of harm to yourself or others.

Tyler G. Hughes, MD, FACS, is a clinical professor in the department of surgery and the director of medical education at the Kansas University in Salina, Kan., as well as a Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Think before you tweet. That’s what surgeons should remember before they express themselves on social media.

Anger and frustration can prompt ill-advised social media postings that have a big potential for blowback, Heather J. Logghe, MD, FACS, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. But so can enthusiasm about posting about a new device or procedure, a fascination with a difficult case, the sense of relief that a patient made it though a harrowing period, or even just the simple joy of tossing back a beer or two with pals at the local watering hole (J Am Coll Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.022).

“In a survey of 48 state medical boards, 44 (92%) reported online-related misbehavior with serious disciplinary consequences leading to license restriction, suspension, or revocation. A 2011 study of ‘Physicians on Twitter’ revealed that 10% of the physicians sampled had tweeted potential patient privacy violations. A 2014 study of publicly available Facebook profiles of 319 Midwest residents found 14% had ‘potentially unprofessional content’ and 12.2% had ‘clearly unprofessional’ content, the latter including references to binge drinking, sexually suggestive photos, and HIPAA violations.”

Dr. Logghe, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, is a member of the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS’s) social media committee tasked with creating practice recommendations for clinicians’ use of social media. Conducting a literature review was the first step to creating a surgeon-specific document, and the team found seven online behavior guidelines directed at physicians. Groups authoring these papers included the American Medical Association, the Federation of State Medical Boards, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and several international groups.

Dr. Logghe and her colleagues reviewed each one, synthesized the information, and created a practice recommendation statement specific to the ACS. While not encoded in any professional ethics requirements, “Best Practices for Surgeons’ Social Media Use: Statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons” does lay out some common, potentially problematic scenarios and offers some suggestions about how to avoid Internet regret.

Everything discussed in the paper revolves around maintaining a decorous public persona. Professionalism on and off the clock is a key tenet of the recommendations. Definitions of key terms like “professionalism” are an important basis for any practice guideline, but sometimes concepts are not easy to define, the team wrote. “Perhaps the limitation most difficult to address in any formalized guideline is the necessary subjectivity in interpreting what is ‘appropriate’ or ‘professional’ online – or in any other setting,” the authors wrote. The ACS Code of Professional Conduct does not explicitly define either of those terms or discuss the appearance of unprofessional behavior.

In the absence of a plain-and-simple definition, the authors attempted to couch the social media recommendations in terms of ACS’s commitment to maintaining the patient trust. It urges surgeons to “avoid even the appearance of impropriety.”

The practice recommendations touch on a number of areas that are potentially problematic for surgeons, including confidentiality, financial conflicts, collegial support, and general social responsibility.

Confidentiality

Maintaining privacy is more than a courtesy to patients: It’s a federally mandated law with serious punitive repercussions if violated. Blogs, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook offer a vast potential for sharing information with and educating the public, but postings can also easily violate HIPPA standards, the team wrote.

“In general, most social media platforms are not HIPPA-compliant,” no matter how the privacy settings are adjusted. These modes of communication are never appropriate for patient-physician communication: They can’t be archived in an electronic health record, and it is ill advised to give any medical advice by using these channels.

Discussing a particular case online, even with the usual defining details omitted, can be a bad idea.“Simply de-identifying patient information may not be sufficient. When posting information online, one must be cognizant of the context of other information available online. Such information includes the poster’s place of employment, news media, and publicly available vital statistics. Therefore even when posting general comments about hospital events, surgical cases, or patients under one’s care, it is essential to consider the sum of information available to the reader, rather than simply the information shared in the isolated post.”

Employment

Most employers have social media guidelines and don’t take kindly to violations – which can affect both current and future job postings. “A strong social media presence can be of benefit to one’s employer, [but] content that portrays a surgeon in an unprofessional or controversial light can be detrimental and even career-damaging.”

This reaches beyond professional communications online and deep into a surgeon’s personal life, the team noted, so exercise caution when “friending.”

“While this practice is inevitable, surgeons should be aware of potential conflicts. Connecting with or accepting friend requests from some but not all coworkers or coresidents could be interpreted as favoritism and may create a problematic work relationship. … Surgeons should consider primarily connecting with coworkers on professional websites if they have little contact with them outside the workplace.”

As for friending patients – just don’t, for both your sake and theirs. “Accepting a patient’s Facebook friend request may allow them access to events, details, and commentary not traditionally appropriate for the patient-physician relationship. Accepting such requests is strongly discouraged. If concerned about appearing rude or rejecting a patient’s request to be Facebook friends, the patient can be referred to society guidelines or best practices such as these.” One helpful alternative to such a request may be to invite patients to follow a practice website or other professional page.

Conflicts of interest

Online friends might not require disclosures when a surgeon posts about an exciting procedure or piece of equipment, such as whether there is a financial interest in doing so, but it’s important to be proactive. “As always, it is the physician’s responsibility to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. If it is not feasible to include a relevant conflict of interest within a post, the post should not be made.”

Defamation

Irritated about a colleague? Keep it to yourself – especially if you’ve had a beer. “It is never appropriate to post derogatory comments about patients or colleagues. Surgeons should be careful not to post in anger or under the influence of any substance. Statements about a colleague’s abilities, experience, or outcomes intended in jest may be appropriate for the surgeon’s lounge, yet entirely inappropriate for public consumption. Again, the ‘pause-before-posting’ practice is likely to prevent regretful posts in this vein.”

Privacy and Permanence

The Internet goes everywhere and lasts forever. A snappy quote that’s funny at 2 a.m. might not seem so hilarious in the light of day – or even in the light of a day 5 years yet to come.

The delete key is a false friend, and that clever pseudonym you dreamed up is probably as crackable as the classic “Pa55word” password. “One should presume that all content posted online will remain there forever and may be seen by anyone. Again, ‘pause-before-posting’ is a recommended practice.”

Privacy settings should be viewed as an illusion, the team noted. In this era of face recognition and tagging, images carry just as much risk as words.

Collegial support

Maybe your mother was right when she said, “This is for your own good.” If a colleague’s postings are getting out of hand, a tactful heart-to-heart might be the best course of action. “As coined by Dr. Sarah Mansfield, ‘Looking after colleagues is an integral element of professional conduct.’ Surgeons who notice colleagues posting unprofessional content that could be damaging to both the colleague and the public’s trust in the profession should discreetly express their concern to the individual, who should then take any appropriate corrective actions. … If the action is in violation of the law or medical board regulations, it should be reported to the appropriate governing bodies.”

Physician, Google Thyself

The team acknowledged that an online presence is virtually a must for professional development. And even if you don’t create a web page, chances are your university or hospital has done it for you. The media is interested in your life, too, and may make mention of your activities – both positive or negative.

“To better understand and control this publicly accessible information, surgeons are encouraged to periodically self-audit themselves online and taking measures to ensure that the information present is accurate and professional.” Some professional service websites are more trustworthy than others. The team encouraged physicians to participate in the ACS professional pages, LinkedIn, Doximity, and ResearchGate.

Not rules – just recommendations

The team stressed that their recommendations aren’t meant to stifle personal expression. Instead, their aim is to prompt a more conscious use of what can be a very powerful tool for both self-expression and professional development.

“The authors recommend no punitive action based on a perceived ‘violation’ of these recommendations alone. While they refer to other guidelines, including laws such as HIPAA, that must be appropriately enforced, these best practices are intended to guide the practicing surgeon in the use of social media rather than act as regulations or encourage reprimand. Rather than encouraging a social media landscape as sterile as the operating theater, the authors hope these recommendations lead to conscious consideration of online behavior, to avoidance of preventable harm, and to recognition of others’ views of their posts.”

None of the authors reported any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Logghe HJ et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.022.

Think before you tweet. That’s what surgeons should remember before they express themselves on social media.

Anger and frustration can prompt ill-advised social media postings that have a big potential for blowback, Heather J. Logghe, MD, FACS, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. But so can enthusiasm about posting about a new device or procedure, a fascination with a difficult case, the sense of relief that a patient made it though a harrowing period, or even just the simple joy of tossing back a beer or two with pals at the local watering hole (J Am Coll Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.022).

“In a survey of 48 state medical boards, 44 (92%) reported online-related misbehavior with serious disciplinary consequences leading to license restriction, suspension, or revocation. A 2011 study of ‘Physicians on Twitter’ revealed that 10% of the physicians sampled had tweeted potential patient privacy violations. A 2014 study of publicly available Facebook profiles of 319 Midwest residents found 14% had ‘potentially unprofessional content’ and 12.2% had ‘clearly unprofessional’ content, the latter including references to binge drinking, sexually suggestive photos, and HIPAA violations.”

Dr. Logghe, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, is a member of the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS’s) social media committee tasked with creating practice recommendations for clinicians’ use of social media. Conducting a literature review was the first step to creating a surgeon-specific document, and the team found seven online behavior guidelines directed at physicians. Groups authoring these papers included the American Medical Association, the Federation of State Medical Boards, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and several international groups.

Dr. Logghe and her colleagues reviewed each one, synthesized the information, and created a practice recommendation statement specific to the ACS. While not encoded in any professional ethics requirements, “Best Practices for Surgeons’ Social Media Use: Statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons” does lay out some common, potentially problematic scenarios and offers some suggestions about how to avoid Internet regret.

Everything discussed in the paper revolves around maintaining a decorous public persona. Professionalism on and off the clock is a key tenet of the recommendations. Definitions of key terms like “professionalism” are an important basis for any practice guideline, but sometimes concepts are not easy to define, the team wrote. “Perhaps the limitation most difficult to address in any formalized guideline is the necessary subjectivity in interpreting what is ‘appropriate’ or ‘professional’ online – or in any other setting,” the authors wrote. The ACS Code of Professional Conduct does not explicitly define either of those terms or discuss the appearance of unprofessional behavior.

In the absence of a plain-and-simple definition, the authors attempted to couch the social media recommendations in terms of ACS’s commitment to maintaining the patient trust. It urges surgeons to “avoid even the appearance of impropriety.”

The practice recommendations touch on a number of areas that are potentially problematic for surgeons, including confidentiality, financial conflicts, collegial support, and general social responsibility.

Confidentiality

Maintaining privacy is more than a courtesy to patients: It’s a federally mandated law with serious punitive repercussions if violated. Blogs, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook offer a vast potential for sharing information with and educating the public, but postings can also easily violate HIPPA standards, the team wrote.

“In general, most social media platforms are not HIPPA-compliant,” no matter how the privacy settings are adjusted. These modes of communication are never appropriate for patient-physician communication: They can’t be archived in an electronic health record, and it is ill advised to give any medical advice by using these channels.

Discussing a particular case online, even with the usual defining details omitted, can be a bad idea.“Simply de-identifying patient information may not be sufficient. When posting information online, one must be cognizant of the context of other information available online. Such information includes the poster’s place of employment, news media, and publicly available vital statistics. Therefore even when posting general comments about hospital events, surgical cases, or patients under one’s care, it is essential to consider the sum of information available to the reader, rather than simply the information shared in the isolated post.”

Employment

Most employers have social media guidelines and don’t take kindly to violations – which can affect both current and future job postings. “A strong social media presence can be of benefit to one’s employer, [but] content that portrays a surgeon in an unprofessional or controversial light can be detrimental and even career-damaging.”

This reaches beyond professional communications online and deep into a surgeon’s personal life, the team noted, so exercise caution when “friending.”

“While this practice is inevitable, surgeons should be aware of potential conflicts. Connecting with or accepting friend requests from some but not all coworkers or coresidents could be interpreted as favoritism and may create a problematic work relationship. … Surgeons should consider primarily connecting with coworkers on professional websites if they have little contact with them outside the workplace.”

As for friending patients – just don’t, for both your sake and theirs. “Accepting a patient’s Facebook friend request may allow them access to events, details, and commentary not traditionally appropriate for the patient-physician relationship. Accepting such requests is strongly discouraged. If concerned about appearing rude or rejecting a patient’s request to be Facebook friends, the patient can be referred to society guidelines or best practices such as these.” One helpful alternative to such a request may be to invite patients to follow a practice website or other professional page.

Conflicts of interest

Online friends might not require disclosures when a surgeon posts about an exciting procedure or piece of equipment, such as whether there is a financial interest in doing so, but it’s important to be proactive. “As always, it is the physician’s responsibility to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. If it is not feasible to include a relevant conflict of interest within a post, the post should not be made.”

Defamation

Irritated about a colleague? Keep it to yourself – especially if you’ve had a beer. “It is never appropriate to post derogatory comments about patients or colleagues. Surgeons should be careful not to post in anger or under the influence of any substance. Statements about a colleague’s abilities, experience, or outcomes intended in jest may be appropriate for the surgeon’s lounge, yet entirely inappropriate for public consumption. Again, the ‘pause-before-posting’ practice is likely to prevent regretful posts in this vein.”

Privacy and Permanence

The Internet goes everywhere and lasts forever. A snappy quote that’s funny at 2 a.m. might not seem so hilarious in the light of day – or even in the light of a day 5 years yet to come.

The delete key is a false friend, and that clever pseudonym you dreamed up is probably as crackable as the classic “Pa55word” password. “One should presume that all content posted online will remain there forever and may be seen by anyone. Again, ‘pause-before-posting’ is a recommended practice.”

Privacy settings should be viewed as an illusion, the team noted. In this era of face recognition and tagging, images carry just as much risk as words.

Collegial support

Maybe your mother was right when she said, “This is for your own good.” If a colleague’s postings are getting out of hand, a tactful heart-to-heart might be the best course of action. “As coined by Dr. Sarah Mansfield, ‘Looking after colleagues is an integral element of professional conduct.’ Surgeons who notice colleagues posting unprofessional content that could be damaging to both the colleague and the public’s trust in the profession should discreetly express their concern to the individual, who should then take any appropriate corrective actions. … If the action is in violation of the law or medical board regulations, it should be reported to the appropriate governing bodies.”

Physician, Google Thyself

The team acknowledged that an online presence is virtually a must for professional development. And even if you don’t create a web page, chances are your university or hospital has done it for you. The media is interested in your life, too, and may make mention of your activities – both positive or negative.

“To better understand and control this publicly accessible information, surgeons are encouraged to periodically self-audit themselves online and taking measures to ensure that the information present is accurate and professional.” Some professional service websites are more trustworthy than others. The team encouraged physicians to participate in the ACS professional pages, LinkedIn, Doximity, and ResearchGate.

Not rules – just recommendations

The team stressed that their recommendations aren’t meant to stifle personal expression. Instead, their aim is to prompt a more conscious use of what can be a very powerful tool for both self-expression and professional development.

“The authors recommend no punitive action based on a perceived ‘violation’ of these recommendations alone. While they refer to other guidelines, including laws such as HIPAA, that must be appropriately enforced, these best practices are intended to guide the practicing surgeon in the use of social media rather than act as regulations or encourage reprimand. Rather than encouraging a social media landscape as sterile as the operating theater, the authors hope these recommendations lead to conscious consideration of online behavior, to avoidance of preventable harm, and to recognition of others’ views of their posts.”

None of the authors reported any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Logghe HJ et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.022.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

MyPlate as effective as calorie counting after 12 months

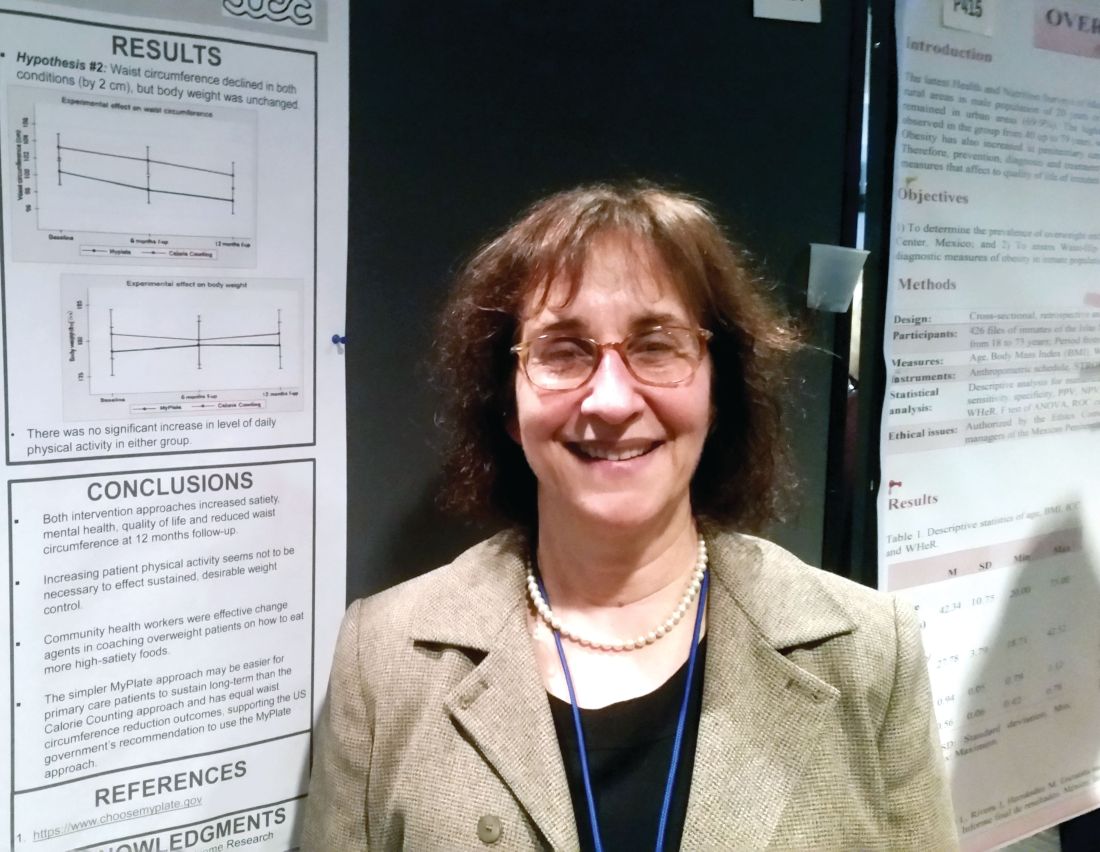

MONTREAL – The high-satiety MyPlate approach to weight loss reduced waist circumference, improved mental health and quality of life, and increased satiety 12 months into a study that found the strategy as effective as a conventional calorie-counting approach.

After 12 months, waist circumference had decreased by about 2 cm in study participants, regardless of whether they used the MyPlate approach or counted calories. Body weight was unchanged after a year in both groups.

“The simpler MyPlate approach may be easier for primary care patients to sustain long-term than the calorie-counting approach and has equal waist circumference reduction outcomes, supporting the U.S. government’s recommendation to use the MyPlate approach,” wrote Lillian Gelberg, MD, and her collaborators.

MyPlate recommends eating more fruits and vegetables, making half of grain choices whole grain, replacing sugary drinks with water, limiting sodium intake.

Over the study period, neither group significantly increased their physical activity. “Increasing patient physical activity seems not to be necessary to effect sustained, desirable weight control,” the researchers wrote.

The comparative effectiveness study compared the two weight loss approaches in 261 primarily Hispanic patients at two federally qualified health center clinics.

The primary outcome in the patient-centered study was perceived satiety; secondary outcomes included waist circumference, weight, mental health, quality of life, intake of sugary drinks, water intake, and exercise.

Participants received 11 health coaching sessions from bilingual community health workers, dubbed “promotoras,” over a 6 month period. “Community health workers were effective change agents in coaching overweight patients on how to eat more high-satiety foods,” Dr. Gelberg and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Two of the sessions were hour-long home-based sessions; the MyPlate group also received two hour-long cooking demonstrations. Both groups received two hour-long group education sessions, as well as a total of seven 20-minute telephone coaching sessions.

Most participants (56%) were in five sessions during the study period, with a quarter completing 10 of the 11 sessions. At 12 months, 80% of study members were still being followed.

Overall, 95% of the participants were female, and about half (n = 126) did not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

A total of 86% were Hispanic, and Spanish was the preferred language for about three quarters of all participants. Most patients (82%) were born outside the United States.

The mean age at enrollment was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 for about half (46%) of the patients; 5% had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more.

In an interview, Dr. Gelberg, professor of family medicine and public health and management at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that the investigators had hypothesized that the MyPlate approach would be easier for patients to follow, because it’s easier to understand and less cumbersome in terms of record keeping. The investigators did not think that one approach would result in greater reductions in body weight or waist circumference, a finding borne out by the data presented.

Both groups reduced their intake of sugary drinks and increased the amount of water they drank, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Dr. Gelberg reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

This article was updated on 2/13/18

MONTREAL – The high-satiety MyPlate approach to weight loss reduced waist circumference, improved mental health and quality of life, and increased satiety 12 months into a study that found the strategy as effective as a conventional calorie-counting approach.

After 12 months, waist circumference had decreased by about 2 cm in study participants, regardless of whether they used the MyPlate approach or counted calories. Body weight was unchanged after a year in both groups.

“The simpler MyPlate approach may be easier for primary care patients to sustain long-term than the calorie-counting approach and has equal waist circumference reduction outcomes, supporting the U.S. government’s recommendation to use the MyPlate approach,” wrote Lillian Gelberg, MD, and her collaborators.

MyPlate recommends eating more fruits and vegetables, making half of grain choices whole grain, replacing sugary drinks with water, limiting sodium intake.

Over the study period, neither group significantly increased their physical activity. “Increasing patient physical activity seems not to be necessary to effect sustained, desirable weight control,” the researchers wrote.

The comparative effectiveness study compared the two weight loss approaches in 261 primarily Hispanic patients at two federally qualified health center clinics.

The primary outcome in the patient-centered study was perceived satiety; secondary outcomes included waist circumference, weight, mental health, quality of life, intake of sugary drinks, water intake, and exercise.

Participants received 11 health coaching sessions from bilingual community health workers, dubbed “promotoras,” over a 6 month period. “Community health workers were effective change agents in coaching overweight patients on how to eat more high-satiety foods,” Dr. Gelberg and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Two of the sessions were hour-long home-based sessions; the MyPlate group also received two hour-long cooking demonstrations. Both groups received two hour-long group education sessions, as well as a total of seven 20-minute telephone coaching sessions.

Most participants (56%) were in five sessions during the study period, with a quarter completing 10 of the 11 sessions. At 12 months, 80% of study members were still being followed.

Overall, 95% of the participants were female, and about half (n = 126) did not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

A total of 86% were Hispanic, and Spanish was the preferred language for about three quarters of all participants. Most patients (82%) were born outside the United States.

The mean age at enrollment was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 for about half (46%) of the patients; 5% had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more.

In an interview, Dr. Gelberg, professor of family medicine and public health and management at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that the investigators had hypothesized that the MyPlate approach would be easier for patients to follow, because it’s easier to understand and less cumbersome in terms of record keeping. The investigators did not think that one approach would result in greater reductions in body weight or waist circumference, a finding borne out by the data presented.

Both groups reduced their intake of sugary drinks and increased the amount of water they drank, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Dr. Gelberg reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

This article was updated on 2/13/18

MONTREAL – The high-satiety MyPlate approach to weight loss reduced waist circumference, improved mental health and quality of life, and increased satiety 12 months into a study that found the strategy as effective as a conventional calorie-counting approach.

After 12 months, waist circumference had decreased by about 2 cm in study participants, regardless of whether they used the MyPlate approach or counted calories. Body weight was unchanged after a year in both groups.

“The simpler MyPlate approach may be easier for primary care patients to sustain long-term than the calorie-counting approach and has equal waist circumference reduction outcomes, supporting the U.S. government’s recommendation to use the MyPlate approach,” wrote Lillian Gelberg, MD, and her collaborators.

MyPlate recommends eating more fruits and vegetables, making half of grain choices whole grain, replacing sugary drinks with water, limiting sodium intake.

Over the study period, neither group significantly increased their physical activity. “Increasing patient physical activity seems not to be necessary to effect sustained, desirable weight control,” the researchers wrote.

The comparative effectiveness study compared the two weight loss approaches in 261 primarily Hispanic patients at two federally qualified health center clinics.

The primary outcome in the patient-centered study was perceived satiety; secondary outcomes included waist circumference, weight, mental health, quality of life, intake of sugary drinks, water intake, and exercise.

Participants received 11 health coaching sessions from bilingual community health workers, dubbed “promotoras,” over a 6 month period. “Community health workers were effective change agents in coaching overweight patients on how to eat more high-satiety foods,” Dr. Gelberg and her colleagues noted in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group.

Two of the sessions were hour-long home-based sessions; the MyPlate group also received two hour-long cooking demonstrations. Both groups received two hour-long group education sessions, as well as a total of seven 20-minute telephone coaching sessions.

Most participants (56%) were in five sessions during the study period, with a quarter completing 10 of the 11 sessions. At 12 months, 80% of study members were still being followed.

Overall, 95% of the participants were female, and about half (n = 126) did not have a high school diploma or equivalent.

A total of 86% were Hispanic, and Spanish was the preferred language for about three quarters of all participants. Most patients (82%) were born outside the United States.

The mean age at enrollment was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 30 to less than 35 kg/m2 for about half (46%) of the patients; 5% had a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more.

In an interview, Dr. Gelberg, professor of family medicine and public health and management at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that the investigators had hypothesized that the MyPlate approach would be easier for patients to follow, because it’s easier to understand and less cumbersome in terms of record keeping. The investigators did not think that one approach would result in greater reductions in body weight or waist circumference, a finding borne out by the data presented.

Both groups reduced their intake of sugary drinks and increased the amount of water they drank, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute. Dr. Gelberg reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

This article was updated on 2/13/18

REPORTING FROM NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 12 months, both approaches reduced waist circumference by 2 cm but didn’t result in weight loss.

Data source: Prospective randomized comparative effectiveness trial of 261 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Gelberg reported no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Comparative Effectiveness Institute.

Source: Gelberg L, abstract P414.

FDA axes asthma drugs’ boxed warning

The Food and Drug Administration has eliminated the boxed warning for risk of asthma-related death from the labels of products containing both an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta agonist (LABA), the agency announced.

In 2011, the FDA required companies manufacturing fixed-dose LABA-ICS combination products to conduct 26-week clinical safety trials to evaluate the risks of serious adverse asthma-related events in patients treated with these drugs. Specifically, the companies had to compare the follows the FDA’s review of these trials, which found that treating asthma with LABAs in combination with ICS did not result in patients experiencing significantly more serious asthma-related side effects and asthma-related deaths, compared with those being treated with an ICS alone, according to the FDA announcement. “Results of subgroup analyses for gender, adolescents 12-18 years, and African Americans are consistent with the primary endpoint results,” the statement added.

“These trials showed that LABAs, when used with ICS, did not significantly increase the risk of asthma-related hospitalizations, the need to insert a breathing tube known as intubation, or asthma-related deaths, compared to ICS alone,” the FDA said in the statement.

The trials also demonstrated that using the combination reduced asthma exacerbations, compared with using ICS alone, and that most of the exacerbations “were those that required at least 3 days of systemic corticosteroids” – information that is being added the product labels, according to the FDA.

The products that will no longer carry this boxed warning in their labels include AstraZeneca’s budesonide/formoterol fumarate dihydrate (Symbicort) and GlaxoSmithKline’s fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (Breo Ellipta) and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (Advair Diskus and Advair HFA).

The FDA also approved updates to the Warnings and Precautions section of labeling for the ICS/LABA class, which now includes a description of the four trials. Information on the efficacy of the drugs, found in the trials, has been added to the Clinical Studies section of the labels as well.

In a related safety announcement, the FDA stated the following: “Using LABAs alone to treat asthma without an ICS to treat lung inflammation is associated with an increased risk of asthma-related death. Therefore, the Boxed Warning stating this will remain in the labels of all single-ingredient LABA medicines, which are approved to treat asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and wheezing caused by exercise. The labels of medicines that contain both an ICS and LABA also retain a Warning and Precaution related to the increased risk of asthma-related death when LABAs are used without an ICS to treat asthma.

The Food and Drug Administration has eliminated the boxed warning for risk of asthma-related death from the labels of products containing both an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta agonist (LABA), the agency announced.

In 2011, the FDA required companies manufacturing fixed-dose LABA-ICS combination products to conduct 26-week clinical safety trials to evaluate the risks of serious adverse asthma-related events in patients treated with these drugs. Specifically, the companies had to compare the follows the FDA’s review of these trials, which found that treating asthma with LABAs in combination with ICS did not result in patients experiencing significantly more serious asthma-related side effects and asthma-related deaths, compared with those being treated with an ICS alone, according to the FDA announcement. “Results of subgroup analyses for gender, adolescents 12-18 years, and African Americans are consistent with the primary endpoint results,” the statement added.

“These trials showed that LABAs, when used with ICS, did not significantly increase the risk of asthma-related hospitalizations, the need to insert a breathing tube known as intubation, or asthma-related deaths, compared to ICS alone,” the FDA said in the statement.

The trials also demonstrated that using the combination reduced asthma exacerbations, compared with using ICS alone, and that most of the exacerbations “were those that required at least 3 days of systemic corticosteroids” – information that is being added the product labels, according to the FDA.

The products that will no longer carry this boxed warning in their labels include AstraZeneca’s budesonide/formoterol fumarate dihydrate (Symbicort) and GlaxoSmithKline’s fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (Breo Ellipta) and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (Advair Diskus and Advair HFA).

The FDA also approved updates to the Warnings and Precautions section of labeling for the ICS/LABA class, which now includes a description of the four trials. Information on the efficacy of the drugs, found in the trials, has been added to the Clinical Studies section of the labels as well.

In a related safety announcement, the FDA stated the following: “Using LABAs alone to treat asthma without an ICS to treat lung inflammation is associated with an increased risk of asthma-related death. Therefore, the Boxed Warning stating this will remain in the labels of all single-ingredient LABA medicines, which are approved to treat asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and wheezing caused by exercise. The labels of medicines that contain both an ICS and LABA also retain a Warning and Precaution related to the increased risk of asthma-related death when LABAs are used without an ICS to treat asthma.

The Food and Drug Administration has eliminated the boxed warning for risk of asthma-related death from the labels of products containing both an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a long-acting beta agonist (LABA), the agency announced.