User login

This month in the journal CHEST®

Editor’s Picks

Editor in Chief, CHEST

Giants in CHEST Medicine –Arthur S. Slutsky, MD, MASc, BASc

By Dr. Eliot A. Phillipson

Original Research

A Longitudinal Cohort Study of Aspirin Use and Progression of Emphysema-like Lung

Characteristics on CT Imaging: The MESA Lung Study

By Dr. C. P. Aaron, et al.

The Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the Risk of ARDS: A Systematic Review and

Meta-analysis

By Dr. E. Simou, et al.

The Relationship Between COPD and Frailty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of

Observational Studies

By Dr. A. Marengoni, et al.

Editor’s Picks

Editor in Chief, CHEST

Giants in CHEST Medicine –Arthur S. Slutsky, MD, MASc, BASc

By Dr. Eliot A. Phillipson

Original Research

A Longitudinal Cohort Study of Aspirin Use and Progression of Emphysema-like Lung

Characteristics on CT Imaging: The MESA Lung Study

By Dr. C. P. Aaron, et al.

The Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the Risk of ARDS: A Systematic Review and

Meta-analysis

By Dr. E. Simou, et al.

The Relationship Between COPD and Frailty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of

Observational Studies

By Dr. A. Marengoni, et al.

Editor’s Picks

Editor in Chief, CHEST

Giants in CHEST Medicine –Arthur S. Slutsky, MD, MASc, BASc

By Dr. Eliot A. Phillipson

Original Research

A Longitudinal Cohort Study of Aspirin Use and Progression of Emphysema-like Lung

Characteristics on CT Imaging: The MESA Lung Study

By Dr. C. P. Aaron, et al.

The Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the Risk of ARDS: A Systematic Review and

Meta-analysis

By Dr. E. Simou, et al.

The Relationship Between COPD and Frailty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of

Observational Studies

By Dr. A. Marengoni, et al.

Family Fun in San Antonio During CHEST 2018

Planning on bringing your family with you to CHEST 2018 in San Antonio? Well, we’ve got you covered on ways to have some family fun when you’re not immersed in learning at the convention center. Here are a few activities you can take part in:

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

There are four San Antonio Missions you can visit: San José, Espada, Concepción, and San Juan. Explore the missions on your own, or join a park ranger or volunteer for a free, 45- to 60- minute guided tour of your chosen mission. While Mission San José is the most popular tour with ranger-led tours between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm, make sure to stop at the visitor center or information center of the other missions you want to tour to check available tour times.

World’s Largest Cowboy Boots

Just outside Saks Fifth Avenue at North Star Mall, you can take a selfie next to the World’s Largest Cowboy Boots. These 35-foot tall and 30-foot long boots shouldn’t be too hard to spot. Originally the boots were built by Bob “Daddy-O” Wade in Washington, DC, in 1979 and moved to San Antonio just 1 year later.

Natural Bridge Caverns

Explore the Natural Bridge Caverns, the largest caverns in Texas. This family-owned and family-operated attraction offers guided and adventure tours, and outdoor maze, mining for gems and fossils, and more! When you’re done, you can visit the Shops of Discovery Village where you’ll find treats, a general store, and souvenirs to take home.

The Alamo Trolley

Need a captivating-yet-low impact activity? Ride the Alamo Trolley. This “hop-on, hop-off” trolley allows you to explore San Antonio at your own pace. With 10 stops around town, this entirely narrated tour includes The Alamo, Hemisfair Park, River Walk, the Mission Trail, and more.

Clyde and Seamore’s Sea Lion High

If you go to SeaWorld San Antonio, kids will love attending the sea lion show called “Clyde and Seamore’s Sea Lion High.” The sea lions perform tricks and interact with the audience as Clyde and Seamore go back to school in search of their diplomas.

Cool Off at a Waterpark

While October weather in San Antonio may be slightly cooler than in the summer, it still averages in the mid-80 degrees Fahrenheit, so you’ll want to cool off at the pool or a waterpark. Take some downtime with the family and head to one of the several waterparks in the area, including Schlitterbahn, Splashtown San Antonio, and Aquatica at SeaWorld.

Brackenridge Park

Spend the day at one of San Antonio’s most popular parks, Brackenridge Park. Hike or bike along one of the nature trails, have a picnic, play with your kids at the Kiddie Park, or find the Japanese Tea Garden. Want to add something a little more exciting to your day? The San Antonio Zoo is also on the grounds, where there are lots of animals, experiences, and events.

Planning on bringing your family with you to CHEST 2018 in San Antonio? Well, we’ve got you covered on ways to have some family fun when you’re not immersed in learning at the convention center. Here are a few activities you can take part in:

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

There are four San Antonio Missions you can visit: San José, Espada, Concepción, and San Juan. Explore the missions on your own, or join a park ranger or volunteer for a free, 45- to 60- minute guided tour of your chosen mission. While Mission San José is the most popular tour with ranger-led tours between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm, make sure to stop at the visitor center or information center of the other missions you want to tour to check available tour times.

World’s Largest Cowboy Boots

Just outside Saks Fifth Avenue at North Star Mall, you can take a selfie next to the World’s Largest Cowboy Boots. These 35-foot tall and 30-foot long boots shouldn’t be too hard to spot. Originally the boots were built by Bob “Daddy-O” Wade in Washington, DC, in 1979 and moved to San Antonio just 1 year later.

Natural Bridge Caverns

Explore the Natural Bridge Caverns, the largest caverns in Texas. This family-owned and family-operated attraction offers guided and adventure tours, and outdoor maze, mining for gems and fossils, and more! When you’re done, you can visit the Shops of Discovery Village where you’ll find treats, a general store, and souvenirs to take home.

The Alamo Trolley

Need a captivating-yet-low impact activity? Ride the Alamo Trolley. This “hop-on, hop-off” trolley allows you to explore San Antonio at your own pace. With 10 stops around town, this entirely narrated tour includes The Alamo, Hemisfair Park, River Walk, the Mission Trail, and more.

Clyde and Seamore’s Sea Lion High

If you go to SeaWorld San Antonio, kids will love attending the sea lion show called “Clyde and Seamore’s Sea Lion High.” The sea lions perform tricks and interact with the audience as Clyde and Seamore go back to school in search of their diplomas.

Cool Off at a Waterpark

While October weather in San Antonio may be slightly cooler than in the summer, it still averages in the mid-80 degrees Fahrenheit, so you’ll want to cool off at the pool or a waterpark. Take some downtime with the family and head to one of the several waterparks in the area, including Schlitterbahn, Splashtown San Antonio, and Aquatica at SeaWorld.

Brackenridge Park

Spend the day at one of San Antonio’s most popular parks, Brackenridge Park. Hike or bike along one of the nature trails, have a picnic, play with your kids at the Kiddie Park, or find the Japanese Tea Garden. Want to add something a little more exciting to your day? The San Antonio Zoo is also on the grounds, where there are lots of animals, experiences, and events.

Planning on bringing your family with you to CHEST 2018 in San Antonio? Well, we’ve got you covered on ways to have some family fun when you’re not immersed in learning at the convention center. Here are a few activities you can take part in:

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

There are four San Antonio Missions you can visit: San José, Espada, Concepción, and San Juan. Explore the missions on your own, or join a park ranger or volunteer for a free, 45- to 60- minute guided tour of your chosen mission. While Mission San José is the most popular tour with ranger-led tours between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm, make sure to stop at the visitor center or information center of the other missions you want to tour to check available tour times.

World’s Largest Cowboy Boots

Just outside Saks Fifth Avenue at North Star Mall, you can take a selfie next to the World’s Largest Cowboy Boots. These 35-foot tall and 30-foot long boots shouldn’t be too hard to spot. Originally the boots were built by Bob “Daddy-O” Wade in Washington, DC, in 1979 and moved to San Antonio just 1 year later.

Natural Bridge Caverns

Explore the Natural Bridge Caverns, the largest caverns in Texas. This family-owned and family-operated attraction offers guided and adventure tours, and outdoor maze, mining for gems and fossils, and more! When you’re done, you can visit the Shops of Discovery Village where you’ll find treats, a general store, and souvenirs to take home.

The Alamo Trolley

Need a captivating-yet-low impact activity? Ride the Alamo Trolley. This “hop-on, hop-off” trolley allows you to explore San Antonio at your own pace. With 10 stops around town, this entirely narrated tour includes The Alamo, Hemisfair Park, River Walk, the Mission Trail, and more.

Clyde and Seamore’s Sea Lion High

If you go to SeaWorld San Antonio, kids will love attending the sea lion show called “Clyde and Seamore’s Sea Lion High.” The sea lions perform tricks and interact with the audience as Clyde and Seamore go back to school in search of their diplomas.

Cool Off at a Waterpark

While October weather in San Antonio may be slightly cooler than in the summer, it still averages in the mid-80 degrees Fahrenheit, so you’ll want to cool off at the pool or a waterpark. Take some downtime with the family and head to one of the several waterparks in the area, including Schlitterbahn, Splashtown San Antonio, and Aquatica at SeaWorld.

Brackenridge Park

Spend the day at one of San Antonio’s most popular parks, Brackenridge Park. Hike or bike along one of the nature trails, have a picnic, play with your kids at the Kiddie Park, or find the Japanese Tea Garden. Want to add something a little more exciting to your day? The San Antonio Zoo is also on the grounds, where there are lots of animals, experiences, and events.

Launching the Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) announces a new partnership with Medscape focused on supporting physicians in addressing the challenges of diagnosing and treating moderate to severe asthma. The Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence (https://www.medscape.com/resource/moderate-severe-asthma) will provide news, expert commentary, and insights on challenging cases to physicians specializing in chest medicine, allergy, primary care, pediatrics, and emergency medicine.

Medscape is a leading source of clinical news, health information, and point-of-care tools for physicians and health-care professionals. This new Center of Excellence available on Medscape.com will explore the diagnostic, therapeutic, and prevention strategies associated with moderate to severe asthma, including the latest research and breakthroughs. Topics will include challenges in classifying and diagnosing disease; risks, benefits, and barriers to treatment; and impact on patients’ quality of life.

“We look forward to working with Medscape on the Center of Excellence to ensure that all physicians treating patients with asthma have access to the latest information and research on managing this pervasive and challenging disease,” said John Studdard, MD, FCCP, President, American College of Chest Physicians.

“The Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence with CHEST provides a new, accessible channel for information, practical insights, and commentary to the thousands of physicians and health-care professionals who visit Medscape daily,” said Jo-Ann Strangis, Senior Vice President, Editorial for Medscape. “We are privileged to be working with CHEST and look forward to the Center of Excellence making a meaningful difference in patient care.”

Don’t miss Dr. Aaron Holley’s video on “Diagnosing Severe Asthma: ‘Not as Easy as It Sounds” (https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/896135?src=dpcs).

Visit the Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence: https://www.medscape.com/resource/moderate-severe-asthma

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) announces a new partnership with Medscape focused on supporting physicians in addressing the challenges of diagnosing and treating moderate to severe asthma. The Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence (https://www.medscape.com/resource/moderate-severe-asthma) will provide news, expert commentary, and insights on challenging cases to physicians specializing in chest medicine, allergy, primary care, pediatrics, and emergency medicine.

Medscape is a leading source of clinical news, health information, and point-of-care tools for physicians and health-care professionals. This new Center of Excellence available on Medscape.com will explore the diagnostic, therapeutic, and prevention strategies associated with moderate to severe asthma, including the latest research and breakthroughs. Topics will include challenges in classifying and diagnosing disease; risks, benefits, and barriers to treatment; and impact on patients’ quality of life.

“We look forward to working with Medscape on the Center of Excellence to ensure that all physicians treating patients with asthma have access to the latest information and research on managing this pervasive and challenging disease,” said John Studdard, MD, FCCP, President, American College of Chest Physicians.

“The Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence with CHEST provides a new, accessible channel for information, practical insights, and commentary to the thousands of physicians and health-care professionals who visit Medscape daily,” said Jo-Ann Strangis, Senior Vice President, Editorial for Medscape. “We are privileged to be working with CHEST and look forward to the Center of Excellence making a meaningful difference in patient care.”

Don’t miss Dr. Aaron Holley’s video on “Diagnosing Severe Asthma: ‘Not as Easy as It Sounds” (https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/896135?src=dpcs).

Visit the Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence: https://www.medscape.com/resource/moderate-severe-asthma

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) announces a new partnership with Medscape focused on supporting physicians in addressing the challenges of diagnosing and treating moderate to severe asthma. The Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence (https://www.medscape.com/resource/moderate-severe-asthma) will provide news, expert commentary, and insights on challenging cases to physicians specializing in chest medicine, allergy, primary care, pediatrics, and emergency medicine.

Medscape is a leading source of clinical news, health information, and point-of-care tools for physicians and health-care professionals. This new Center of Excellence available on Medscape.com will explore the diagnostic, therapeutic, and prevention strategies associated with moderate to severe asthma, including the latest research and breakthroughs. Topics will include challenges in classifying and diagnosing disease; risks, benefits, and barriers to treatment; and impact on patients’ quality of life.

“We look forward to working with Medscape on the Center of Excellence to ensure that all physicians treating patients with asthma have access to the latest information and research on managing this pervasive and challenging disease,” said John Studdard, MD, FCCP, President, American College of Chest Physicians.

“The Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence with CHEST provides a new, accessible channel for information, practical insights, and commentary to the thousands of physicians and health-care professionals who visit Medscape daily,” said Jo-Ann Strangis, Senior Vice President, Editorial for Medscape. “We are privileged to be working with CHEST and look forward to the Center of Excellence making a meaningful difference in patient care.”

Don’t miss Dr. Aaron Holley’s video on “Diagnosing Severe Asthma: ‘Not as Easy as It Sounds” (https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/896135?src=dpcs).

Visit the Moderate to Severe Asthma Center of Excellence: https://www.medscape.com/resource/moderate-severe-asthma

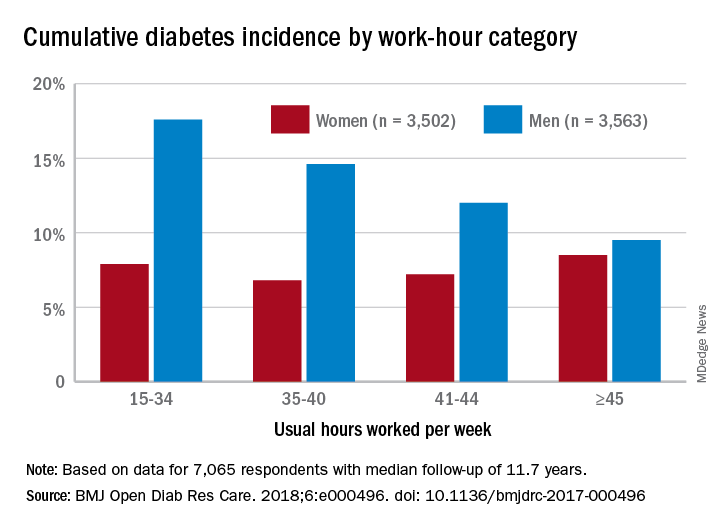

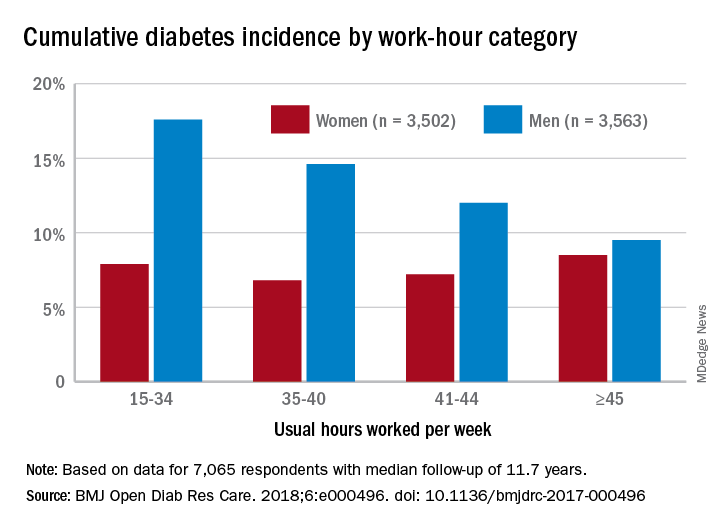

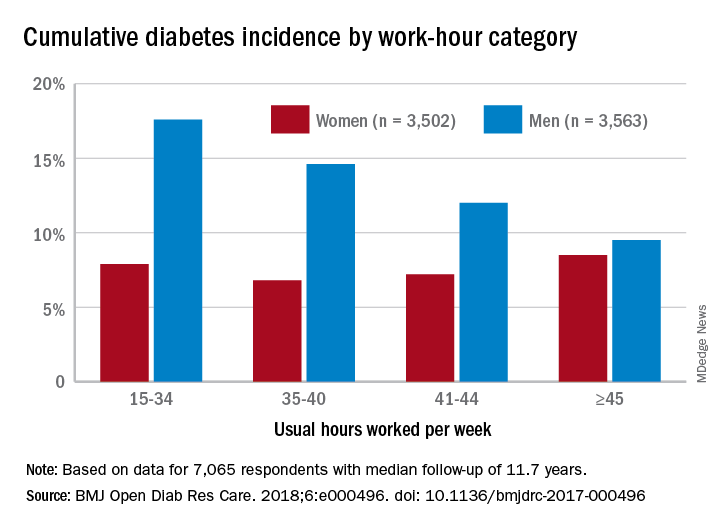

Diabetes risk may rise with work hours

Men have a higher risk overall for developing diabetes, 12.2%, compared with 7.5% for women, but the risk for women increases as they work more hours per week, which is not the case for men, according to the results of a 12-year Canadian study that included over 7,000 workers.

Among the 3,502 women in the study, those who worked 45 or more hours per week had a cumulative diabetes incidence of 8.5% over the median 11.7 years of follow-up. Diabetes incidence was 7.2% for women who worked 41-44 hours a week, 6.8% for those who worked 35-40 hours, and 7.9% among women who worked 15-34 hours weekly, Mahée Gilbert-Ouimet, PhD, of the Institute for Work & Health, Toronto, and her associates reported in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care.

For the 3,563 men included in the study, diabetes incidence was 9.5% for those who worked at least 45 hours a week versus 12% for those who worked 41-44 hours, 14.6% for men working 35-40 hours weekly, and 17.6% among those who put in 15-34 hours, the investigators wrote.

Hazard ratios for working 45 or more hours, compared with 35-40 hours, were 1.63 for women and 0.81 for men after adjustment for age, level of education, working conditions, and other factors, although the effect was significant only for women, they noted.

“Considering the rapid and substantial increase of diabetes prevalence in Canada and worldwide, identifying modifiable risk factors, such as long work hours, is of major importance to improve prevention and orient policy making as it could prevent numerous cases of diabetes and diabetes-related chronic diseases,” Dr. Gilbert-Ouimet and her associates wrote.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. None of the investigators declared any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gilbert-Ouimet M et al. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000496.

Men have a higher risk overall for developing diabetes, 12.2%, compared with 7.5% for women, but the risk for women increases as they work more hours per week, which is not the case for men, according to the results of a 12-year Canadian study that included over 7,000 workers.

Among the 3,502 women in the study, those who worked 45 or more hours per week had a cumulative diabetes incidence of 8.5% over the median 11.7 years of follow-up. Diabetes incidence was 7.2% for women who worked 41-44 hours a week, 6.8% for those who worked 35-40 hours, and 7.9% among women who worked 15-34 hours weekly, Mahée Gilbert-Ouimet, PhD, of the Institute for Work & Health, Toronto, and her associates reported in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care.

For the 3,563 men included in the study, diabetes incidence was 9.5% for those who worked at least 45 hours a week versus 12% for those who worked 41-44 hours, 14.6% for men working 35-40 hours weekly, and 17.6% among those who put in 15-34 hours, the investigators wrote.

Hazard ratios for working 45 or more hours, compared with 35-40 hours, were 1.63 for women and 0.81 for men after adjustment for age, level of education, working conditions, and other factors, although the effect was significant only for women, they noted.

“Considering the rapid and substantial increase of diabetes prevalence in Canada and worldwide, identifying modifiable risk factors, such as long work hours, is of major importance to improve prevention and orient policy making as it could prevent numerous cases of diabetes and diabetes-related chronic diseases,” Dr. Gilbert-Ouimet and her associates wrote.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. None of the investigators declared any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gilbert-Ouimet M et al. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000496.

Men have a higher risk overall for developing diabetes, 12.2%, compared with 7.5% for women, but the risk for women increases as they work more hours per week, which is not the case for men, according to the results of a 12-year Canadian study that included over 7,000 workers.

Among the 3,502 women in the study, those who worked 45 or more hours per week had a cumulative diabetes incidence of 8.5% over the median 11.7 years of follow-up. Diabetes incidence was 7.2% for women who worked 41-44 hours a week, 6.8% for those who worked 35-40 hours, and 7.9% among women who worked 15-34 hours weekly, Mahée Gilbert-Ouimet, PhD, of the Institute for Work & Health, Toronto, and her associates reported in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care.

For the 3,563 men included in the study, diabetes incidence was 9.5% for those who worked at least 45 hours a week versus 12% for those who worked 41-44 hours, 14.6% for men working 35-40 hours weekly, and 17.6% among those who put in 15-34 hours, the investigators wrote.

Hazard ratios for working 45 or more hours, compared with 35-40 hours, were 1.63 for women and 0.81 for men after adjustment for age, level of education, working conditions, and other factors, although the effect was significant only for women, they noted.

“Considering the rapid and substantial increase of diabetes prevalence in Canada and worldwide, identifying modifiable risk factors, such as long work hours, is of major importance to improve prevention and orient policy making as it could prevent numerous cases of diabetes and diabetes-related chronic diseases,” Dr. Gilbert-Ouimet and her associates wrote.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. None of the investigators declared any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gilbert-Ouimet M et al. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000496.

FROM BMJ OPEN DIABETES RESEARCH & CARE

High risk of low glucose? Hospital alerts promise a crucial heads-up

ORLANDO – Researchers have been able to sustain a dramatic reduction in hypoglycemia incidents at nine St. Louis–area hospitals, thanks to a computer algorithm that warns medical staff when patients appear to be on the road to dangerously low blood sugar levels.

The 6-year retrospective system-wide study, which was released at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, found that the use of the alert system lowered the annual occurrence of severe hypoglycemia events by 41% at the hospitals.

In at-risk patients – those with blood glucose levels under 90 mg/dL – the system considers several variables, such as their weight, creatinine clearance, insulin therapy, and basal insulin doses. If the algorithm considers that a patient is at high risk of a sub–40-mg/dL glucose level – dangerously low – it sends a single alert to medical staff during the patient’s stay.

The idea is that the real-time alerts will go to nurses or pharmacists who will review patient charts and then contact physicians. The doctors are expected to “make clinically appropriate changes,” Dr. Tobin said.

Earlier, Dr. Tobin and colleagues prospectively analyzed the alert system’s effectiveness at a single hospital for 5 months. The trial, a cohort intervention study, tracked 655 patients with a blood glucose level under 90 mg/dL.

In 2014, the researchers reported the results of that trial: The alert identified 390 of the patients as being at high risk for severe hypoglycemia (blood glucose under 40 mg/dL). The frequency of severe hypoglycemia events was just 3.1% in this population vs. 9.7% in unalerted patients who were also deemed to be at high risk (J Hosp Med. 2014[9]: 621-6).

For the new study, researchers extended the alert system to nine hospitals and tracked its use from 2011 to 2017.

During all visits, the number of severe hypoglycemic events fell from 2.9 to 1.7 per 1,000 at-risk patient days. (P less than .001)

At one hospital, Dr. Tobin said, the average monthly number of severe hypoglycemia incidents fell from 40 to 12.

Researchers found that the average blood glucose level post alert was 93 mg/dL vs. 74 mg/dL before alert. They also reported that the system-wide total of alerts per year ranged from 4,142 to 5,649.

“The current data reflected in our poster show that the alert process is sustainable over a wide range of clinical settings, including community hospitals of various size and complexity, as well as academic medical centers,” Dr. Tobin said.

The alert system had no effect on hyperglycemia, Dr. Tobin said.

In regard to expense, Dr. Tobin said it’s small because the alert system uses existing current staff and computer systems. Setup costs, he said, included programming, creating the alert infrastructure, and staff training

No study funding is reported. Dr. Tobin reports relationships with Novo Nordisk (advisory board, speaker’s bureau) and MannKind (speaker’s bureau). The other authors report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Tobin G et al. ADA 2018. Abstract 397-P.

ORLANDO – Researchers have been able to sustain a dramatic reduction in hypoglycemia incidents at nine St. Louis–area hospitals, thanks to a computer algorithm that warns medical staff when patients appear to be on the road to dangerously low blood sugar levels.

The 6-year retrospective system-wide study, which was released at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, found that the use of the alert system lowered the annual occurrence of severe hypoglycemia events by 41% at the hospitals.

In at-risk patients – those with blood glucose levels under 90 mg/dL – the system considers several variables, such as their weight, creatinine clearance, insulin therapy, and basal insulin doses. If the algorithm considers that a patient is at high risk of a sub–40-mg/dL glucose level – dangerously low – it sends a single alert to medical staff during the patient’s stay.

The idea is that the real-time alerts will go to nurses or pharmacists who will review patient charts and then contact physicians. The doctors are expected to “make clinically appropriate changes,” Dr. Tobin said.

Earlier, Dr. Tobin and colleagues prospectively analyzed the alert system’s effectiveness at a single hospital for 5 months. The trial, a cohort intervention study, tracked 655 patients with a blood glucose level under 90 mg/dL.

In 2014, the researchers reported the results of that trial: The alert identified 390 of the patients as being at high risk for severe hypoglycemia (blood glucose under 40 mg/dL). The frequency of severe hypoglycemia events was just 3.1% in this population vs. 9.7% in unalerted patients who were also deemed to be at high risk (J Hosp Med. 2014[9]: 621-6).

For the new study, researchers extended the alert system to nine hospitals and tracked its use from 2011 to 2017.

During all visits, the number of severe hypoglycemic events fell from 2.9 to 1.7 per 1,000 at-risk patient days. (P less than .001)

At one hospital, Dr. Tobin said, the average monthly number of severe hypoglycemia incidents fell from 40 to 12.

Researchers found that the average blood glucose level post alert was 93 mg/dL vs. 74 mg/dL before alert. They also reported that the system-wide total of alerts per year ranged from 4,142 to 5,649.

“The current data reflected in our poster show that the alert process is sustainable over a wide range of clinical settings, including community hospitals of various size and complexity, as well as academic medical centers,” Dr. Tobin said.

The alert system had no effect on hyperglycemia, Dr. Tobin said.

In regard to expense, Dr. Tobin said it’s small because the alert system uses existing current staff and computer systems. Setup costs, he said, included programming, creating the alert infrastructure, and staff training

No study funding is reported. Dr. Tobin reports relationships with Novo Nordisk (advisory board, speaker’s bureau) and MannKind (speaker’s bureau). The other authors report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Tobin G et al. ADA 2018. Abstract 397-P.

ORLANDO – Researchers have been able to sustain a dramatic reduction in hypoglycemia incidents at nine St. Louis–area hospitals, thanks to a computer algorithm that warns medical staff when patients appear to be on the road to dangerously low blood sugar levels.

The 6-year retrospective system-wide study, which was released at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, found that the use of the alert system lowered the annual occurrence of severe hypoglycemia events by 41% at the hospitals.

In at-risk patients – those with blood glucose levels under 90 mg/dL – the system considers several variables, such as their weight, creatinine clearance, insulin therapy, and basal insulin doses. If the algorithm considers that a patient is at high risk of a sub–40-mg/dL glucose level – dangerously low – it sends a single alert to medical staff during the patient’s stay.

The idea is that the real-time alerts will go to nurses or pharmacists who will review patient charts and then contact physicians. The doctors are expected to “make clinically appropriate changes,” Dr. Tobin said.

Earlier, Dr. Tobin and colleagues prospectively analyzed the alert system’s effectiveness at a single hospital for 5 months. The trial, a cohort intervention study, tracked 655 patients with a blood glucose level under 90 mg/dL.

In 2014, the researchers reported the results of that trial: The alert identified 390 of the patients as being at high risk for severe hypoglycemia (blood glucose under 40 mg/dL). The frequency of severe hypoglycemia events was just 3.1% in this population vs. 9.7% in unalerted patients who were also deemed to be at high risk (J Hosp Med. 2014[9]: 621-6).

For the new study, researchers extended the alert system to nine hospitals and tracked its use from 2011 to 2017.

During all visits, the number of severe hypoglycemic events fell from 2.9 to 1.7 per 1,000 at-risk patient days. (P less than .001)

At one hospital, Dr. Tobin said, the average monthly number of severe hypoglycemia incidents fell from 40 to 12.

Researchers found that the average blood glucose level post alert was 93 mg/dL vs. 74 mg/dL before alert. They also reported that the system-wide total of alerts per year ranged from 4,142 to 5,649.

“The current data reflected in our poster show that the alert process is sustainable over a wide range of clinical settings, including community hospitals of various size and complexity, as well as academic medical centers,” Dr. Tobin said.

The alert system had no effect on hyperglycemia, Dr. Tobin said.

In regard to expense, Dr. Tobin said it’s small because the alert system uses existing current staff and computer systems. Setup costs, he said, included programming, creating the alert infrastructure, and staff training

No study funding is reported. Dr. Tobin reports relationships with Novo Nordisk (advisory board, speaker’s bureau) and MannKind (speaker’s bureau). The other authors report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Tobin G et al. ADA 2018. Abstract 397-P.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Hospitals were able to sustain lower numbers of severe hypoglycemia events over 6 years by using a prewarning alert system.

Major finding: The number of severe hypoglycemic events (below 40 mg/dL) fell from 2.9 per 1,000 at-risk patient-days to 1.7 per 1,000 at-risk patient-days.

Study details: Retrospective, system-wide study of nine hospitals with alert system in place from 2011 to 2017.

Disclosures: No funding is reported. One author reports relationships with Novo Nordisk and MannKind. The other authors report no relevant disclosures.

Source: Tobin G et al. ADA 2018. Abstract 397-P.

Data Indicate Disparities in IV t-PA Administration

Women are more likely than men, and African Americans are less likely than Caucasians, to receive IV t-PA.

LOS ANGELES—Variables such as age, sex, race, and insurance status predict whether a patient with ischemic stroke will receive IV t-PA, according to an analysis presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The results provide “compelling evidence” of disparities, despite increased use of IV thrombolysis over time, said F. Stephen Benesh, MD, Chief Resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine.

Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States and has an economic impact of more than $34 billion annually, said Dr. Benesh. IV t-PA has been available since the 1990s, but not all eligible patients have access to this treatment. Dr. Benesh and colleagues examined data from the National Inpatient Sample to find emerging trends and predictors of IV t-PA administration in the clinical setting.

The National Inpatient Sample is a stratified sample of all discharges from US community hospitals. The investigators analyzed data from 2003 through 2013 and identified 1,168,847 patients who had been discharged with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke. They ascertained whether patients had received thrombolytic infusion by looking at medical coding. A bimodal logistic regression analysis was performed to identify differences between patients who received t-PA and those who did not. Variables included age, sex, race, teaching status of the treating institution, and patient’s insurance type.

During the period examined, 3.2% of patients with ischemic stroke received thrombolytic treatment. The annual rate of IV t-PA administration increased during the period to approximately 6% in 2013.

Women were slightly more likely to receive IV t-PA than men (odds ratio [OR], 1.036). African Americans (OR, 0.884) were less likely than Caucasians to receive IV t-PA.

Patients insured with Medicare were less likely to receive t-PA than patients insured with Medicaid (OR, 1.128), patients with private insurance (OR, 1.216), and self-paying patients (OR, 1.162). Dr. Benesh and colleagues found no statistically significant difference in the rate of t-PA administration between patients with Medicaid, those with private insurance, and self-paying patients.

In addition, teaching hospitals were more likely than nonteaching hospitals to administer IV t-PA (OR, 1.685).

Various factors may account for the discrepancies in IV t-PA administration. For example, a recent study found that African Americans are more likely to refuse t-PA than patients of other ethnicities. This research reveals “ongoing problems with education and socioeconomic disparities,” said Dr. Benesh.

—Erik Greb

Women are more likely than men, and African Americans are less likely than Caucasians, to receive IV t-PA.

Women are more likely than men, and African Americans are less likely than Caucasians, to receive IV t-PA.

LOS ANGELES—Variables such as age, sex, race, and insurance status predict whether a patient with ischemic stroke will receive IV t-PA, according to an analysis presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The results provide “compelling evidence” of disparities, despite increased use of IV thrombolysis over time, said F. Stephen Benesh, MD, Chief Resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine.

Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States and has an economic impact of more than $34 billion annually, said Dr. Benesh. IV t-PA has been available since the 1990s, but not all eligible patients have access to this treatment. Dr. Benesh and colleagues examined data from the National Inpatient Sample to find emerging trends and predictors of IV t-PA administration in the clinical setting.

The National Inpatient Sample is a stratified sample of all discharges from US community hospitals. The investigators analyzed data from 2003 through 2013 and identified 1,168,847 patients who had been discharged with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke. They ascertained whether patients had received thrombolytic infusion by looking at medical coding. A bimodal logistic regression analysis was performed to identify differences between patients who received t-PA and those who did not. Variables included age, sex, race, teaching status of the treating institution, and patient’s insurance type.

During the period examined, 3.2% of patients with ischemic stroke received thrombolytic treatment. The annual rate of IV t-PA administration increased during the period to approximately 6% in 2013.

Women were slightly more likely to receive IV t-PA than men (odds ratio [OR], 1.036). African Americans (OR, 0.884) were less likely than Caucasians to receive IV t-PA.

Patients insured with Medicare were less likely to receive t-PA than patients insured with Medicaid (OR, 1.128), patients with private insurance (OR, 1.216), and self-paying patients (OR, 1.162). Dr. Benesh and colleagues found no statistically significant difference in the rate of t-PA administration between patients with Medicaid, those with private insurance, and self-paying patients.

In addition, teaching hospitals were more likely than nonteaching hospitals to administer IV t-PA (OR, 1.685).

Various factors may account for the discrepancies in IV t-PA administration. For example, a recent study found that African Americans are more likely to refuse t-PA than patients of other ethnicities. This research reveals “ongoing problems with education and socioeconomic disparities,” said Dr. Benesh.

—Erik Greb

LOS ANGELES—Variables such as age, sex, race, and insurance status predict whether a patient with ischemic stroke will receive IV t-PA, according to an analysis presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The results provide “compelling evidence” of disparities, despite increased use of IV thrombolysis over time, said F. Stephen Benesh, MD, Chief Resident at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine.

Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States and has an economic impact of more than $34 billion annually, said Dr. Benesh. IV t-PA has been available since the 1990s, but not all eligible patients have access to this treatment. Dr. Benesh and colleagues examined data from the National Inpatient Sample to find emerging trends and predictors of IV t-PA administration in the clinical setting.

The National Inpatient Sample is a stratified sample of all discharges from US community hospitals. The investigators analyzed data from 2003 through 2013 and identified 1,168,847 patients who had been discharged with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke. They ascertained whether patients had received thrombolytic infusion by looking at medical coding. A bimodal logistic regression analysis was performed to identify differences between patients who received t-PA and those who did not. Variables included age, sex, race, teaching status of the treating institution, and patient’s insurance type.

During the period examined, 3.2% of patients with ischemic stroke received thrombolytic treatment. The annual rate of IV t-PA administration increased during the period to approximately 6% in 2013.

Women were slightly more likely to receive IV t-PA than men (odds ratio [OR], 1.036). African Americans (OR, 0.884) were less likely than Caucasians to receive IV t-PA.

Patients insured with Medicare were less likely to receive t-PA than patients insured with Medicaid (OR, 1.128), patients with private insurance (OR, 1.216), and self-paying patients (OR, 1.162). Dr. Benesh and colleagues found no statistically significant difference in the rate of t-PA administration between patients with Medicaid, those with private insurance, and self-paying patients.

In addition, teaching hospitals were more likely than nonteaching hospitals to administer IV t-PA (OR, 1.685).

Various factors may account for the discrepancies in IV t-PA administration. For example, a recent study found that African Americans are more likely to refuse t-PA than patients of other ethnicities. This research reveals “ongoing problems with education and socioeconomic disparities,” said Dr. Benesh.

—Erik Greb

Is Sodium Oxybate Effective in Children With Narcolepsy?

The drug appears to reduce cataplexy and excessive sleepiness without raising new safety concerns.

LOS ANGELES—Sodium oxybate reduces cataplexy and excessive sleepiness in children with narcolepsy type 1, according to a study described at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The treatment’s safety profile in this population is similar to that in adults.

Although symptoms of narcolepsy often begin during childhood or adolescence, few studies have evaluated treatments for narcolepsy in pediatric patients. Sodium oxybate is approved for the treatment of cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness in adults with narcolepsy, but it had not previously been studied in a large pediatric narcolepsy trial. Chad Ruoff, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine in California, and colleagues conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-withdrawal study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate in pediatric patients with narcolepsy type 1.

A Randomized-Withdrawal Study

Eligible participants were children and adolescents between ages 7 and 16 who had been diagnosed with narcolepsy type 1 and had cataplexy. Patients who were on stable doses of sodium oxybate and patients who were sodium-oxybate-naïve were included. Patients with evidence of sleep-disordered breathing were excluded.

Sodium-oxybate-naïve participants were titrated to a stable dose. After a stable-dose period, all participants began a two-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal period. The investigators randomized participants in equal groups to continue sodium oxybate or to be switched to placebo. At the end of the double-blind period, all participants received open-label sodium oxybate treatment. Efficacy assessments compared measurements during or at the end of the double-blind period with those taken the last two weeks of the stable-dose period. The study’s primary end point was change in weekly number of cataplexy attacks.

Study Was Terminated Early

Dr. Ruoff and colleagues randomized 63 participants. Approximately 41% of the population was between ages 7 and 11, 44% was female, and 38% was receiving sodium oxybate at baseline. A preplanned interim analysis of 35 participants indicated that sodium oxybate was effective, based on the primary end point result. The double-blind, randomized-withdrawal period thus was terminated early.

For the total group of 63 randomized participants, weekly cataplexy attacks were significantly increased in the placebo group (median, 12.7/week), compared with the sodium-oxybate-treated group (median, 0.3/week). Cataplexy severity, assessed using the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C), was worse in the placebo group than in the sodium-oxybate group. For 65% of participants in the placebo group, cataplexy was rated “much worse” or “very much worse,” compared with 17% of the sodium-oxybate group. Excessive sleepiness, assessed using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale for Children and Adolescents, also was worse in the placebo group (median increase, 3.0 points) than in the sodium-oxybate group (no change). In addition, the CGI-C for narcolepsy overall was worse in the placebo group.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in more than 10% of the overall sample were enuresis, nausea, vomiting, headache, and decreased weight. These adverse events had been reported in previous trials of sodium oxybate in adults with narcolepsy.

The study was sponsored by Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

The drug appears to reduce cataplexy and excessive sleepiness without raising new safety concerns.

The drug appears to reduce cataplexy and excessive sleepiness without raising new safety concerns.

LOS ANGELES—Sodium oxybate reduces cataplexy and excessive sleepiness in children with narcolepsy type 1, according to a study described at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The treatment’s safety profile in this population is similar to that in adults.

Although symptoms of narcolepsy often begin during childhood or adolescence, few studies have evaluated treatments for narcolepsy in pediatric patients. Sodium oxybate is approved for the treatment of cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness in adults with narcolepsy, but it had not previously been studied in a large pediatric narcolepsy trial. Chad Ruoff, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine in California, and colleagues conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-withdrawal study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate in pediatric patients with narcolepsy type 1.

A Randomized-Withdrawal Study

Eligible participants were children and adolescents between ages 7 and 16 who had been diagnosed with narcolepsy type 1 and had cataplexy. Patients who were on stable doses of sodium oxybate and patients who were sodium-oxybate-naïve were included. Patients with evidence of sleep-disordered breathing were excluded.

Sodium-oxybate-naïve participants were titrated to a stable dose. After a stable-dose period, all participants began a two-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal period. The investigators randomized participants in equal groups to continue sodium oxybate or to be switched to placebo. At the end of the double-blind period, all participants received open-label sodium oxybate treatment. Efficacy assessments compared measurements during or at the end of the double-blind period with those taken the last two weeks of the stable-dose period. The study’s primary end point was change in weekly number of cataplexy attacks.

Study Was Terminated Early

Dr. Ruoff and colleagues randomized 63 participants. Approximately 41% of the population was between ages 7 and 11, 44% was female, and 38% was receiving sodium oxybate at baseline. A preplanned interim analysis of 35 participants indicated that sodium oxybate was effective, based on the primary end point result. The double-blind, randomized-withdrawal period thus was terminated early.

For the total group of 63 randomized participants, weekly cataplexy attacks were significantly increased in the placebo group (median, 12.7/week), compared with the sodium-oxybate-treated group (median, 0.3/week). Cataplexy severity, assessed using the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C), was worse in the placebo group than in the sodium-oxybate group. For 65% of participants in the placebo group, cataplexy was rated “much worse” or “very much worse,” compared with 17% of the sodium-oxybate group. Excessive sleepiness, assessed using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale for Children and Adolescents, also was worse in the placebo group (median increase, 3.0 points) than in the sodium-oxybate group (no change). In addition, the CGI-C for narcolepsy overall was worse in the placebo group.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in more than 10% of the overall sample were enuresis, nausea, vomiting, headache, and decreased weight. These adverse events had been reported in previous trials of sodium oxybate in adults with narcolepsy.

The study was sponsored by Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

LOS ANGELES—Sodium oxybate reduces cataplexy and excessive sleepiness in children with narcolepsy type 1, according to a study described at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The treatment’s safety profile in this population is similar to that in adults.

Although symptoms of narcolepsy often begin during childhood or adolescence, few studies have evaluated treatments for narcolepsy in pediatric patients. Sodium oxybate is approved for the treatment of cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness in adults with narcolepsy, but it had not previously been studied in a large pediatric narcolepsy trial. Chad Ruoff, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford Center for Sleep Sciences and Medicine in California, and colleagues conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized-withdrawal study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate in pediatric patients with narcolepsy type 1.

A Randomized-Withdrawal Study

Eligible participants were children and adolescents between ages 7 and 16 who had been diagnosed with narcolepsy type 1 and had cataplexy. Patients who were on stable doses of sodium oxybate and patients who were sodium-oxybate-naïve were included. Patients with evidence of sleep-disordered breathing were excluded.

Sodium-oxybate-naïve participants were titrated to a stable dose. After a stable-dose period, all participants began a two-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal period. The investigators randomized participants in equal groups to continue sodium oxybate or to be switched to placebo. At the end of the double-blind period, all participants received open-label sodium oxybate treatment. Efficacy assessments compared measurements during or at the end of the double-blind period with those taken the last two weeks of the stable-dose period. The study’s primary end point was change in weekly number of cataplexy attacks.

Study Was Terminated Early

Dr. Ruoff and colleagues randomized 63 participants. Approximately 41% of the population was between ages 7 and 11, 44% was female, and 38% was receiving sodium oxybate at baseline. A preplanned interim analysis of 35 participants indicated that sodium oxybate was effective, based on the primary end point result. The double-blind, randomized-withdrawal period thus was terminated early.

For the total group of 63 randomized participants, weekly cataplexy attacks were significantly increased in the placebo group (median, 12.7/week), compared with the sodium-oxybate-treated group (median, 0.3/week). Cataplexy severity, assessed using the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C), was worse in the placebo group than in the sodium-oxybate group. For 65% of participants in the placebo group, cataplexy was rated “much worse” or “very much worse,” compared with 17% of the sodium-oxybate group. Excessive sleepiness, assessed using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale for Children and Adolescents, also was worse in the placebo group (median increase, 3.0 points) than in the sodium-oxybate group (no change). In addition, the CGI-C for narcolepsy overall was worse in the placebo group.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in more than 10% of the overall sample were enuresis, nausea, vomiting, headache, and decreased weight. These adverse events had been reported in previous trials of sodium oxybate in adults with narcolepsy.

The study was sponsored by Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

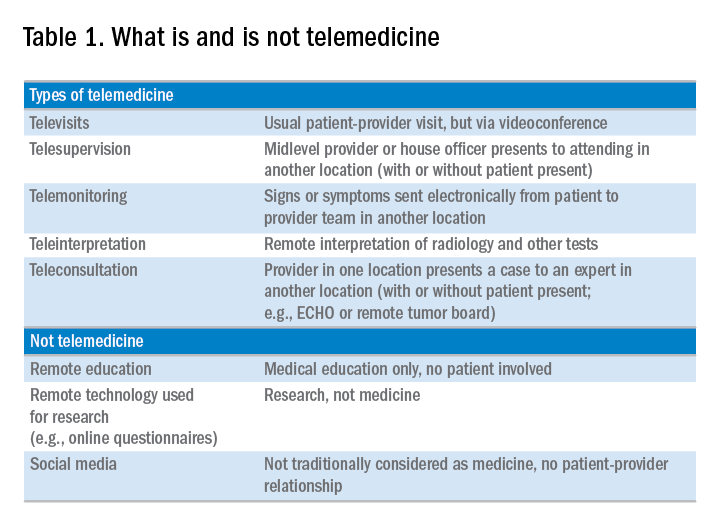

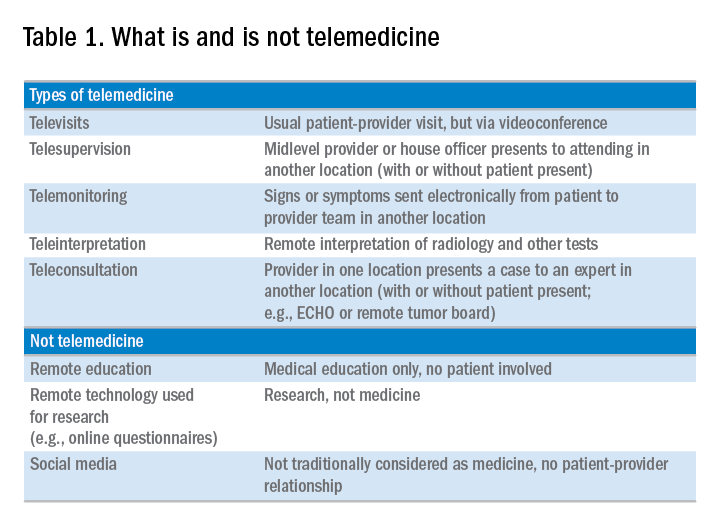

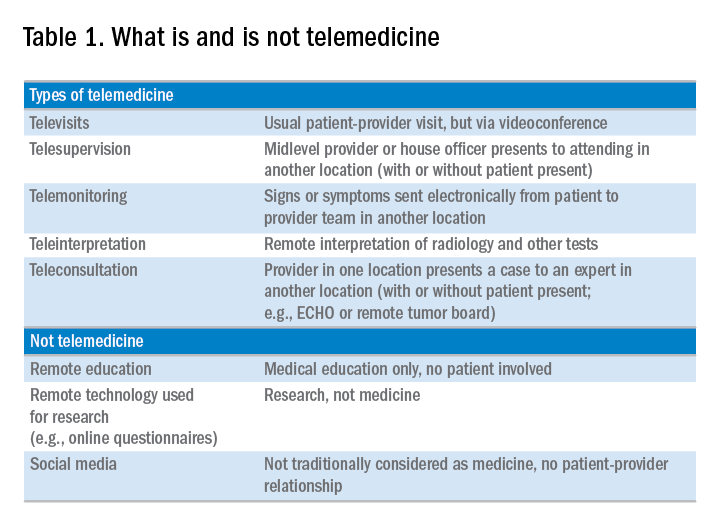

Current and future applications of telemedicine to optimize the delivery of care in chronic liver disease

Telemedicine is defined broadly by the World Health Organization as the delivery of health care services at a distance using electronic means for “the diagnosis of treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, education of health care providers”1 to improve health. Although no single accepted definition exists, telehealth often is used as the umbrella term to encompass telemedicine (health care delivery) in addition to other activities such as education, research, health surveillance, and public health promotion.2 These various terms often are used interchangeably throughout the literature, leading to confusion.1,3 For the purpose of this review, we will use the term telemedicine to describe any care delivery model whereby patient care is provided at a distance using information technology such as cellphones, computers, or other electronic devices.

In the United States, the use of telemedicine is increasing. According to a 2017 survey of 184 health care executives conducted by the American Telemedicine Association, 88% believed that they would invest in telehealth in the near future, 98% believed that it offered a competitive advantage, with the caveat that 71% believed that lack of coverage and payments were barriers to implementation. Recent studies have shown that telehealth interventions are effective at improving clinical outcomes and decreasing inpatient utilization, with good patient satisfaction in the areas of mental health and chronic disease management. The Veterans Administration has emerged as an early telehealth adopter in chronic disease settings such as mental health, dermatology, hypertension, heart failure, and, as of 2016, has provided care to nearly 700,000 (12%) veterans since its inception.4-6 Despite the increased uptake, significant infrastructure and legal barriers to telemedicine remain and the literature regarding its utility in clinical practice continues to emerge.

Compared with other chronic diseases (e.g., heart failure, diabetes, mental illness) there is a dearth of literature on the use of telemedicine in liver disease. The first portion of this review synthesizes currently published literature of telemedicine/telehealth interventions to improve health care delivery and health outcomes in chronic liver disease including published peer-reviewed articles, abstracts, and ongoing clinical trials. The second portion discusses a framework for the future development of telemedicine and its integration into clinical practice by citing examples currently used throughout the country as well as ways to overcome implementation barriers.

Use of telemedicine in chronic liver disease: A literature review

We performed a systematic review of telemedicine in chronic liver disease. In consultation with a biomedical librarian, we searched for English-language articles for relevant studies with adult participants from July 1984 to May 2017 in PubMed, OVID Medline, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, EMBASE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, Elsevier/Science Direct, and the Cochrane Library (the search strategy is shown in the Supplementary Material at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.004). The references of original publications and of review articles additionally were screened for potentially relevant studies. Abstracts that later resulted in no publications and studies in which telemedicine was used to deliver care, but was neither an exposure nor outcome, were excluded. Social media studies were not considered telemedicine if no patient care was involved. Studies of purely medical education interventions or those that evaluated the accuracy of technology to aid in diagnosis also were excluded.

Supplementary Table 1 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.004) shows the 20 published articles of telemedicine studies. Among these, there were 9 prospective trials, 3 retrospective studies, 2 case reports, and 6 small case series. One of the studies was randomized prospectively and 10 were uncontrolled.

Telemedicine in hepatitis C treatment

Telemedicine to aid in procedural/surgical management

A few reports have been published in the use of synchronous video and digital technology to aid in periprocedural management in liver disease. A case report highlighted a successful example of gastroenterologist-led teleproctoring using basic video technology to enable a surgeon to perform sclerotherapy for hemostasis in the setting of a variceal bleed.9 Another case report described the transmission of smart phone images from surgical trainees to an attending physician to make a real-time decision regarding a possibly questionable liver procurement, which took place 545 km away from the university hospital.10 A retrospective case series described the feasibility and successful use of high-resolution digital macroscopic photography and electronic transmission between liver transplant centers in the United Kingdom to increase the utilization of split liver transplantation, a setting in which detailed knowledge of vessel anatomy is needed for advanced surgical planning.11 Similarly, an uncontrolled case series from Greece reported on the feasibility and reliability of macroscopic image transmission to aid in the evaluation of liver grafts for transplantation.12

Telemedicine to support evaluation and management of hepatocellular carcinoma

One recent abstract reported on the use of asynchronous store-and-forward telemedicine for screening and management of hepatocellular carcinoma and evaluated process outcomes of specialty care access for newly diagnosed patients.13 A multifaceted approach included live video teleconferencing and centralized radiology review, which was conducted by a multidisciplinary tumor board at an expert hub site, which provided expert opinion and subsequent care (e.g., locoregional therapy, liver transplant evaluation) to spoke sites. As a result of the initiative, the time to specialty evaluation and receipt of hepatocellular carcinoma therapy decreased by 23 and 25 days, respectively.

Remote monitoring interventions

Proposed framework for advancing telemedicine in liver disease: The case for more research and policy changes

Telemedicine can serve two main goals in liver disease: improve access to specialty care, and improve care between visits. For the first goal, the technology is straightforward and limited research is required; the main barriers are regulatory and reimbursement. As an example, one of the authors (M.L.V.) uses telemedicine to perform liver transplant evaluations in Las Vegas, N.V., a state without a liver transplant program. Patients are seen initially by a nurse practitioner who resides in Las Vegas, and those patients needing transplant evaluation are scheduled for a video visit with the attending physician who is physically in California. This works well and patients love it; however, the business model is dependent on the downstream financial incentive of transplantation. In addition, various regulatory requirements must be satisfied such as monthly in-person visits. For the second goal, a number of exciting possibilities exist such as remote monitoring and patient disease management, but more research is needed.

Research

According to the Pew Research Center, 95% of American adults own a cellphone and 77% own a smartphone. These devices passively gather an extraordinary amount of data that could be harnessed to identify early warning signs of complications (remote monitoring). Another potentially fruitful area of research is patient disease management. This includes using technology (e.g., reminder texts) to effect behavior change such as with medication adherence, lifestyle modification, education, or peer mentoring. As an example, the coauthor (M.S.) is leading a study to promote physical activity among liver transplant recipients by using an online web portal developed by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania (Way to Health), which interfaces with patient cell phones and digital accelerometer devices. Participants receive daily feedback through text messages with their step counts, and small financial incentives are provided for adequate levels of physical activity. Technology also can facilitate the development of disease management platforms, which could improve both access and in-between visit monitoring, especially in remote areas. One of the authors (M.L.V.) currently is leading the development of a remote disease management program with funding from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Despite the tremendous promise, traditional research methods in telemedicine may be challenging given the rapid and increasing uptake of health technology among patients and health systems. As such, the classic paradigm of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the success of an intervention or change in care delivery often is not feasible. We believe there is a need to recalibrate the definition of what constitutes a high-quality telemedicine study. For example, pragmatic trials and those designed within an implementation science framework that evaluate feasibility, scalability, and cost, in parallel with traditional clinical outcomes, may be better suited and should be accepted more widely.17

Policy

Even when the technology is available and research shows efficacy, the implementation of telemedicine in clinical practice faces regulatory and reimbursement barriers. The first regulatory question is whether a patient–provider relationship is being established (with the exception of limited provider–provider curbside consultation, the answer usually is yes). If so, the practice then is subject to all the usual regulatory concerns. The provider needs to be licensed at the site of origin (where the patient is located) and hold malpractice coverage for that location, and the video and medical record transmission should be compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The next challenge is reimbursement. Medicare only pays for video consultation if the patient lives in a designated rural Health Professional Shortage Area (www.cms.gov), and reimbursement by private payers varies. Even this is dependent on ever-changing state laws. Reimbursement for remote patient monitoring is even more limited (the National Telehealth Policy Research Center publishes a useful handbook: http://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/resources/50%20State%20FINAL%20April%202016.pdf). Absent a bipartisan Congressional effort to remedy this situation, the best hope for removing reimbursement barriers lies with payment reform. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 mandates that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services shift from fee-for-service to alternative payment models in the coming years. In these alternate payment models, providers are responsible for the overall quality and total cost of care for a population of patients. In this scenario, there may be a financial incentive for telemedicine, especially remote monitoring, to keep patients out of the hospital. Until then, under current payment models, reimbursement is limited and the barriers to widespread implementation are high.

Conclusions

Telemedicine has continued to increase in uptake and shows tremendous promise in expanding access to health care, promoting patient disease management, and facilitating in-between health care visit monitoring. Although the future is bright, more research is needed to determine optimal ways to integrate telemedicine — especially remote monitoring — into routine clinical care. We call on our specialty societies to send a clear political advocacy message that policy changes are needed to overcome regulatory and reimbursement challenges.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lauren Jones and Mackenzie McDougal for their assistance with the literature review.

Supplementary materials and methods

The telemedicine interventions PubMed literature search strategy was as follows: ((“liver diseases”[MeSH Terms] OR (“liver”[All Fields] AND “diseases”[All Fields]) OR “liver diseases”[All Fields] OR (“liver”[All Fields] AND “disease”[All Fields]) OR “liver disease”[All Fields] OR liver dysfunction OR liver dysfunctions)) OR “liver transplantation”[MeSH Terms] OR “liver transplantation” [All Fields] AND (((“telemedicine”[MeSH Terms] OR “telemedicine”[All Fields] OR mobile health OR mhealth OR telehealth OR mhealth)) OR (videoconferencing OR videoconference)).

References

1. Kirsh S., Su G.L., Sales A., et al. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30:88-90.

2. Wilson L.S., Maeder A.J. recent directions in telemedicine: review of trends in research and practice. Healthc Inform Res. 2015;21:213-22.

3. Cross R.K., Kane, S. Integration of telemedicine into clinical gastroenterology and hepatology practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:175-81.

4. Darkins A., Ryan P., Kobb R., et al. Care coordination/home telehealth: the systematic implementation of health informatics, home telehealth, and disease management to support the care of veteran patients with chronic conditions. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:1118-26.

5. Tuerk P.W., Fortney J., Bosworth H.B., et al. Toward the development of national telehealth services: the role of Veterans Health Administration and future directions for research. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:115-7.

6. VA Press Release. Available: https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/includes/viewPDF.cfm?id=2789. Accessed: July 27, 2017.

7. Arora S., Kalishman S., Thornton K., et al. Expanding access to hepatitis C virus treatment-extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project: disruptive innovation in specialty care. Hepatology. 2010;52:1124-33.

8. Mitruka K., Thornton K., Cusick S., et al. Expanding primary care capacity to treat hepatitis C virus infection through an evidence-based care model–Arizona and Utah, 2012-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:393-8.

9. Ahmed A., Slosberg E., Prasad P., et al. The successful use of telemedicine in acute variceal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:212-3.

10. Croome K.P., Shum J., Al-Basheer M.A., et al. The benefit of smart phone usage in liver organ procurement. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:158-60.

11. Bhati C.S., Wigmore S.J., Reddy S., et al. Web-based image transmission: a novel approach to aid communication in split liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:98-103.

12. Mammas C.S., Geropoulos S., Saatsakis G., et al. Telepathology as a method to optimize quality in organ transplantation: a feasibility and reliability study of the virtual benching of liver graft. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;190:276-8.

13. Egert E.M., et al. A regional multidisciplinary liver tumor board improves access to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment for patients geographically distant from tertiary medical center. Hepatology. 2015;62:469A

14. Thomson M., Volk M., Kim H.M., et al. An automated telephone monitoring system to identify patients with cirrhosis at risk of re-hospitalization. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3563-9.

15. Ertel A.E., Kaiser T.E., Abbott D.E., et al. Use of video-based education and tele-health home monitoring after liver transplantation: results of a novel pilot study. Surgery. 2016;160:869-76.

16. Thygesen G.B., Andersen H., Damsgaard B.S. et al. The effect of nurse performed telemedical video consultations for patients suffering from alcohol-related liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2017;66:S349

17. Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R. et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:65-76.

Dr. Serper is in the division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, and the department of medicine, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia; Dr. Volk is in the division of gastroenterology and Transplantation Institute, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Telemedicine is defined broadly by the World Health Organization as the delivery of health care services at a distance using electronic means for “the diagnosis of treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, education of health care providers”1 to improve health. Although no single accepted definition exists, telehealth often is used as the umbrella term to encompass telemedicine (health care delivery) in addition to other activities such as education, research, health surveillance, and public health promotion.2 These various terms often are used interchangeably throughout the literature, leading to confusion.1,3 For the purpose of this review, we will use the term telemedicine to describe any care delivery model whereby patient care is provided at a distance using information technology such as cellphones, computers, or other electronic devices.

In the United States, the use of telemedicine is increasing. According to a 2017 survey of 184 health care executives conducted by the American Telemedicine Association, 88% believed that they would invest in telehealth in the near future, 98% believed that it offered a competitive advantage, with the caveat that 71% believed that lack of coverage and payments were barriers to implementation. Recent studies have shown that telehealth interventions are effective at improving clinical outcomes and decreasing inpatient utilization, with good patient satisfaction in the areas of mental health and chronic disease management. The Veterans Administration has emerged as an early telehealth adopter in chronic disease settings such as mental health, dermatology, hypertension, heart failure, and, as of 2016, has provided care to nearly 700,000 (12%) veterans since its inception.4-6 Despite the increased uptake, significant infrastructure and legal barriers to telemedicine remain and the literature regarding its utility in clinical practice continues to emerge.

Compared with other chronic diseases (e.g., heart failure, diabetes, mental illness) there is a dearth of literature on the use of telemedicine in liver disease. The first portion of this review synthesizes currently published literature of telemedicine/telehealth interventions to improve health care delivery and health outcomes in chronic liver disease including published peer-reviewed articles, abstracts, and ongoing clinical trials. The second portion discusses a framework for the future development of telemedicine and its integration into clinical practice by citing examples currently used throughout the country as well as ways to overcome implementation barriers.

Use of telemedicine in chronic liver disease: A literature review

We performed a systematic review of telemedicine in chronic liver disease. In consultation with a biomedical librarian, we searched for English-language articles for relevant studies with adult participants from July 1984 to May 2017 in PubMed, OVID Medline, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, EMBASE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, Elsevier/Science Direct, and the Cochrane Library (the search strategy is shown in the Supplementary Material at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.004). The references of original publications and of review articles additionally were screened for potentially relevant studies. Abstracts that later resulted in no publications and studies in which telemedicine was used to deliver care, but was neither an exposure nor outcome, were excluded. Social media studies were not considered telemedicine if no patient care was involved. Studies of purely medical education interventions or those that evaluated the accuracy of technology to aid in diagnosis also were excluded.

Supplementary Table 1 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.004) shows the 20 published articles of telemedicine studies. Among these, there were 9 prospective trials, 3 retrospective studies, 2 case reports, and 6 small case series. One of the studies was randomized prospectively and 10 were uncontrolled.

Telemedicine in hepatitis C treatment

Telemedicine to aid in procedural/surgical management

A few reports have been published in the use of synchronous video and digital technology to aid in periprocedural management in liver disease. A case report highlighted a successful example of gastroenterologist-led teleproctoring using basic video technology to enable a surgeon to perform sclerotherapy for hemostasis in the setting of a variceal bleed.9 Another case report described the transmission of smart phone images from surgical trainees to an attending physician to make a real-time decision regarding a possibly questionable liver procurement, which took place 545 km away from the university hospital.10 A retrospective case series described the feasibility and successful use of high-resolution digital macroscopic photography and electronic transmission between liver transplant centers in the United Kingdom to increase the utilization of split liver transplantation, a setting in which detailed knowledge of vessel anatomy is needed for advanced surgical planning.11 Similarly, an uncontrolled case series from Greece reported on the feasibility and reliability of macroscopic image transmission to aid in the evaluation of liver grafts for transplantation.12

Telemedicine to support evaluation and management of hepatocellular carcinoma

One recent abstract reported on the use of asynchronous store-and-forward telemedicine for screening and management of hepatocellular carcinoma and evaluated process outcomes of specialty care access for newly diagnosed patients.13 A multifaceted approach included live video teleconferencing and centralized radiology review, which was conducted by a multidisciplinary tumor board at an expert hub site, which provided expert opinion and subsequent care (e.g., locoregional therapy, liver transplant evaluation) to spoke sites. As a result of the initiative, the time to specialty evaluation and receipt of hepatocellular carcinoma therapy decreased by 23 and 25 days, respectively.

Remote monitoring interventions

Proposed framework for advancing telemedicine in liver disease: The case for more research and policy changes

Telemedicine can serve two main goals in liver disease: improve access to specialty care, and improve care between visits. For the first goal, the technology is straightforward and limited research is required; the main barriers are regulatory and reimbursement. As an example, one of the authors (M.L.V.) uses telemedicine to perform liver transplant evaluations in Las Vegas, N.V., a state without a liver transplant program. Patients are seen initially by a nurse practitioner who resides in Las Vegas, and those patients needing transplant evaluation are scheduled for a video visit with the attending physician who is physically in California. This works well and patients love it; however, the business model is dependent on the downstream financial incentive of transplantation. In addition, various regulatory requirements must be satisfied such as monthly in-person visits. For the second goal, a number of exciting possibilities exist such as remote monitoring and patient disease management, but more research is needed.

Research

According to the Pew Research Center, 95% of American adults own a cellphone and 77% own a smartphone. These devices passively gather an extraordinary amount of data that could be harnessed to identify early warning signs of complications (remote monitoring). Another potentially fruitful area of research is patient disease management. This includes using technology (e.g., reminder texts) to effect behavior change such as with medication adherence, lifestyle modification, education, or peer mentoring. As an example, the coauthor (M.S.) is leading a study to promote physical activity among liver transplant recipients by using an online web portal developed by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania (Way to Health), which interfaces with patient cell phones and digital accelerometer devices. Participants receive daily feedback through text messages with their step counts, and small financial incentives are provided for adequate levels of physical activity. Technology also can facilitate the development of disease management platforms, which could improve both access and in-between visit monitoring, especially in remote areas. One of the authors (M.L.V.) currently is leading the development of a remote disease management program with funding from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Despite the tremendous promise, traditional research methods in telemedicine may be challenging given the rapid and increasing uptake of health technology among patients and health systems. As such, the classic paradigm of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the success of an intervention or change in care delivery often is not feasible. We believe there is a need to recalibrate the definition of what constitutes a high-quality telemedicine study. For example, pragmatic trials and those designed within an implementation science framework that evaluate feasibility, scalability, and cost, in parallel with traditional clinical outcomes, may be better suited and should be accepted more widely.17

Policy