User login

Critical care medicine: An ongoing journey

My introduction to critical care medicine came about during the summer between my third and fourth years of medical school. During that brief break, I, like most of my classmates, was drawn to the classic medical satire The House of God by Samuel Shem,1 which had become a cult classic in the medical field for its ghoulish medical wisdom and dark humor. In “the house,” the intensive care unit (ICU) is “that mausoleum down the hall,” its patients “perched precariously on the edge of that slick bobsled ride down to death.”1 This sentiment persisted even as I began my critical care medicine fellowship in the mid-1990s.

The science and practice of critical care medicine have changed, evolved, and advanced over the past several decades reflecting newer technology, but also an aging population with higher acuity.2 Critical care medicine has established itself as a specialty in its own right, and the importance of the physician intensivist-led multidisciplinary care teams in optimizing outcome has been demonstrated.3,4 These teams have been associated with improved quality of care, reduced length of stay, improved resource utilization, and reduced rates of complications, morbidity, and death.

While there have been few medical miracles and limited advances in therapeutics over the last 30 years, advances in patient management, adherence to processes of care, better use of technology, and more timely diagnosis and treatment have facilitated improved outcomes.5 Collaboration with nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and other healthcare personnel is invaluable, as these providers are responsible for executing management protocols such as weaning sedation and mechanical ventilation, nutrition, glucose control, vasopressor and electrolyte titration, positioning, and early ambulation.

Unfortunately, as an increasing number of patients are being discharged from the ICU, evidence is accumulating that ICU survivors may develop persistent organ dysfunction requiring prolonged stays in the ICU and resulting in chronic critical illness. A 2015 study estimated 380,000 cases of chronic critical illness annually, particularly among the elderly population, with attendant hospital costs of up to $26 billion.6 While 70% of these patients may survive their hospitalization, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) estimates that the 1-year post-discharge mortality rate may exceed 50%.7

We can take pride and comfort in knowing that the past several decades have seen growth in critical care training, more engaged practice, and heightened communication resulting in lower mortality rates.8 However, a majority of survivors suffer significant morbidities that may be severe and persist for a prolonged period after hospital discharge. These worsening impairments after discharge are termed postintensive care syndrome (PICS), which manifests as a new or worsening mental, cognitive, and physical condition and may affect up to 50% of ICU survivors.6

The impact on daily functioning and quality of life can be devastating, and primary care physicians will be increasingly called on to diagnose and participate in ongoing post-discharge management. Additionally, the impact of critical illness on relatives and informal caregivers can be long-lasting and profound, increasing their own risk of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and financial hardship.

In this issue of the Journal, Golovyan and colleagues identify several potential complications and sequelae of critical illness after discharge from the ICU.9 Primary care providers will see these patients in outpatient settings and need to be prepared to triage and treat the new-onset and chronic conditions for which these patients are at high risk.

In addition, as the authors point out, family members and informal caregivers need to be counseled about the proper care of these patients as well as themselves.

The current healthcare system does not appropriately address these survivors and their families. In 2015, the Society of Critical Care Medicine announced the THRIVE initiative, designed to improve support for the patient and family after critical illness. Given the many survivors and caregivers touched by critical illness, the Society has invested in THRIVE with the intent of helping those affected to work together with clinicians to advance recovery. Through peer support groups, post-ICU clinics, and continuing research into quality improvement, THRIVE may help to reduce readmissions and improve quality of life for critical care survivors and their loved ones.

Things have changed since the days of The House of God. Critical care medicine has become a vibrant medical specialty and an integral part of our healthcare system. Dedicated critical care physicians and the multidisciplinary teams they lead have improved outcomes and resource utilization.2–5

The demand for ICU care will continue to increase as our population ages and the need for medical and surgical services increases commensurately. The ratio of ICU beds to hospital beds continues to escalate, and it is feared that the demand for critical care professionals may outstrip the supply.

While we no longer see that mournful shaking of the head when a patient is admitted to the ICU, we need to have the proper vision and use the most up-to-date scientific knowledge and research in treating underlying illness to ensure that once these patients are discharged, communication continues between critical care and primary care providers. This ongoing support will ensure these patients the best possible quality of life.

- Shem S. The House of God: A Novel. New York: R. Marek Publishers, 1978; chapter 18.

- Lilly CM, Swami S, Liu X, Riker RR, Badawi O. Five year trends of critical care practice and outcomes. Chest 2017; 152(4):723–735. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.050

- Yoo EJ, Edwards JD, Dean ML, Dudley RA. Multidisciplinary critical care and intensivist staffing: results of a statewide survey and association with mortality. J Intensive Care Med 2016; 31(5):325–332. doi:10.1177/0885066614534605

- Levy MM, Rapoport J, Lemeshow S, Chalfin DB, Phillips G, Danis M. Association between critical care physician management and patient mortality in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148(11):801–809. pmid:18519926

- Vincent JL, Singer M, Marini JJ, et al. Thirty years of critical care medicine. Crit Care 2010; 14(3):311. doi:10.1186/cc8979

- Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(6):1070–1077. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x

- Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, et al; ProVent Study Group Investigators. The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med 2015; 43(2):282–287. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000710

- Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ. Long term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA 2010; 303(22):2253–2259. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.761

- Golovyan DM, Khan SH, Wang S, Khan BA. What should I address at follow-up of patients who survive critical illness? Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(7):523–526. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17104

My introduction to critical care medicine came about during the summer between my third and fourth years of medical school. During that brief break, I, like most of my classmates, was drawn to the classic medical satire The House of God by Samuel Shem,1 which had become a cult classic in the medical field for its ghoulish medical wisdom and dark humor. In “the house,” the intensive care unit (ICU) is “that mausoleum down the hall,” its patients “perched precariously on the edge of that slick bobsled ride down to death.”1 This sentiment persisted even as I began my critical care medicine fellowship in the mid-1990s.

The science and practice of critical care medicine have changed, evolved, and advanced over the past several decades reflecting newer technology, but also an aging population with higher acuity.2 Critical care medicine has established itself as a specialty in its own right, and the importance of the physician intensivist-led multidisciplinary care teams in optimizing outcome has been demonstrated.3,4 These teams have been associated with improved quality of care, reduced length of stay, improved resource utilization, and reduced rates of complications, morbidity, and death.

While there have been few medical miracles and limited advances in therapeutics over the last 30 years, advances in patient management, adherence to processes of care, better use of technology, and more timely diagnosis and treatment have facilitated improved outcomes.5 Collaboration with nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and other healthcare personnel is invaluable, as these providers are responsible for executing management protocols such as weaning sedation and mechanical ventilation, nutrition, glucose control, vasopressor and electrolyte titration, positioning, and early ambulation.

Unfortunately, as an increasing number of patients are being discharged from the ICU, evidence is accumulating that ICU survivors may develop persistent organ dysfunction requiring prolonged stays in the ICU and resulting in chronic critical illness. A 2015 study estimated 380,000 cases of chronic critical illness annually, particularly among the elderly population, with attendant hospital costs of up to $26 billion.6 While 70% of these patients may survive their hospitalization, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) estimates that the 1-year post-discharge mortality rate may exceed 50%.7

We can take pride and comfort in knowing that the past several decades have seen growth in critical care training, more engaged practice, and heightened communication resulting in lower mortality rates.8 However, a majority of survivors suffer significant morbidities that may be severe and persist for a prolonged period after hospital discharge. These worsening impairments after discharge are termed postintensive care syndrome (PICS), which manifests as a new or worsening mental, cognitive, and physical condition and may affect up to 50% of ICU survivors.6

The impact on daily functioning and quality of life can be devastating, and primary care physicians will be increasingly called on to diagnose and participate in ongoing post-discharge management. Additionally, the impact of critical illness on relatives and informal caregivers can be long-lasting and profound, increasing their own risk of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and financial hardship.

In this issue of the Journal, Golovyan and colleagues identify several potential complications and sequelae of critical illness after discharge from the ICU.9 Primary care providers will see these patients in outpatient settings and need to be prepared to triage and treat the new-onset and chronic conditions for which these patients are at high risk.

In addition, as the authors point out, family members and informal caregivers need to be counseled about the proper care of these patients as well as themselves.

The current healthcare system does not appropriately address these survivors and their families. In 2015, the Society of Critical Care Medicine announced the THRIVE initiative, designed to improve support for the patient and family after critical illness. Given the many survivors and caregivers touched by critical illness, the Society has invested in THRIVE with the intent of helping those affected to work together with clinicians to advance recovery. Through peer support groups, post-ICU clinics, and continuing research into quality improvement, THRIVE may help to reduce readmissions and improve quality of life for critical care survivors and their loved ones.

Things have changed since the days of The House of God. Critical care medicine has become a vibrant medical specialty and an integral part of our healthcare system. Dedicated critical care physicians and the multidisciplinary teams they lead have improved outcomes and resource utilization.2–5

The demand for ICU care will continue to increase as our population ages and the need for medical and surgical services increases commensurately. The ratio of ICU beds to hospital beds continues to escalate, and it is feared that the demand for critical care professionals may outstrip the supply.

While we no longer see that mournful shaking of the head when a patient is admitted to the ICU, we need to have the proper vision and use the most up-to-date scientific knowledge and research in treating underlying illness to ensure that once these patients are discharged, communication continues between critical care and primary care providers. This ongoing support will ensure these patients the best possible quality of life.

My introduction to critical care medicine came about during the summer between my third and fourth years of medical school. During that brief break, I, like most of my classmates, was drawn to the classic medical satire The House of God by Samuel Shem,1 which had become a cult classic in the medical field for its ghoulish medical wisdom and dark humor. In “the house,” the intensive care unit (ICU) is “that mausoleum down the hall,” its patients “perched precariously on the edge of that slick bobsled ride down to death.”1 This sentiment persisted even as I began my critical care medicine fellowship in the mid-1990s.

The science and practice of critical care medicine have changed, evolved, and advanced over the past several decades reflecting newer technology, but also an aging population with higher acuity.2 Critical care medicine has established itself as a specialty in its own right, and the importance of the physician intensivist-led multidisciplinary care teams in optimizing outcome has been demonstrated.3,4 These teams have been associated with improved quality of care, reduced length of stay, improved resource utilization, and reduced rates of complications, morbidity, and death.

While there have been few medical miracles and limited advances in therapeutics over the last 30 years, advances in patient management, adherence to processes of care, better use of technology, and more timely diagnosis and treatment have facilitated improved outcomes.5 Collaboration with nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and other healthcare personnel is invaluable, as these providers are responsible for executing management protocols such as weaning sedation and mechanical ventilation, nutrition, glucose control, vasopressor and electrolyte titration, positioning, and early ambulation.

Unfortunately, as an increasing number of patients are being discharged from the ICU, evidence is accumulating that ICU survivors may develop persistent organ dysfunction requiring prolonged stays in the ICU and resulting in chronic critical illness. A 2015 study estimated 380,000 cases of chronic critical illness annually, particularly among the elderly population, with attendant hospital costs of up to $26 billion.6 While 70% of these patients may survive their hospitalization, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) estimates that the 1-year post-discharge mortality rate may exceed 50%.7

We can take pride and comfort in knowing that the past several decades have seen growth in critical care training, more engaged practice, and heightened communication resulting in lower mortality rates.8 However, a majority of survivors suffer significant morbidities that may be severe and persist for a prolonged period after hospital discharge. These worsening impairments after discharge are termed postintensive care syndrome (PICS), which manifests as a new or worsening mental, cognitive, and physical condition and may affect up to 50% of ICU survivors.6

The impact on daily functioning and quality of life can be devastating, and primary care physicians will be increasingly called on to diagnose and participate in ongoing post-discharge management. Additionally, the impact of critical illness on relatives and informal caregivers can be long-lasting and profound, increasing their own risk of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and financial hardship.

In this issue of the Journal, Golovyan and colleagues identify several potential complications and sequelae of critical illness after discharge from the ICU.9 Primary care providers will see these patients in outpatient settings and need to be prepared to triage and treat the new-onset and chronic conditions for which these patients are at high risk.

In addition, as the authors point out, family members and informal caregivers need to be counseled about the proper care of these patients as well as themselves.

The current healthcare system does not appropriately address these survivors and their families. In 2015, the Society of Critical Care Medicine announced the THRIVE initiative, designed to improve support for the patient and family after critical illness. Given the many survivors and caregivers touched by critical illness, the Society has invested in THRIVE with the intent of helping those affected to work together with clinicians to advance recovery. Through peer support groups, post-ICU clinics, and continuing research into quality improvement, THRIVE may help to reduce readmissions and improve quality of life for critical care survivors and their loved ones.

Things have changed since the days of The House of God. Critical care medicine has become a vibrant medical specialty and an integral part of our healthcare system. Dedicated critical care physicians and the multidisciplinary teams they lead have improved outcomes and resource utilization.2–5

The demand for ICU care will continue to increase as our population ages and the need for medical and surgical services increases commensurately. The ratio of ICU beds to hospital beds continues to escalate, and it is feared that the demand for critical care professionals may outstrip the supply.

While we no longer see that mournful shaking of the head when a patient is admitted to the ICU, we need to have the proper vision and use the most up-to-date scientific knowledge and research in treating underlying illness to ensure that once these patients are discharged, communication continues between critical care and primary care providers. This ongoing support will ensure these patients the best possible quality of life.

- Shem S. The House of God: A Novel. New York: R. Marek Publishers, 1978; chapter 18.

- Lilly CM, Swami S, Liu X, Riker RR, Badawi O. Five year trends of critical care practice and outcomes. Chest 2017; 152(4):723–735. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.050

- Yoo EJ, Edwards JD, Dean ML, Dudley RA. Multidisciplinary critical care and intensivist staffing: results of a statewide survey and association with mortality. J Intensive Care Med 2016; 31(5):325–332. doi:10.1177/0885066614534605

- Levy MM, Rapoport J, Lemeshow S, Chalfin DB, Phillips G, Danis M. Association between critical care physician management and patient mortality in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148(11):801–809. pmid:18519926

- Vincent JL, Singer M, Marini JJ, et al. Thirty years of critical care medicine. Crit Care 2010; 14(3):311. doi:10.1186/cc8979

- Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(6):1070–1077. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x

- Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, et al; ProVent Study Group Investigators. The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med 2015; 43(2):282–287. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000710

- Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ. Long term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA 2010; 303(22):2253–2259. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.761

- Golovyan DM, Khan SH, Wang S, Khan BA. What should I address at follow-up of patients who survive critical illness? Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(7):523–526. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17104

- Shem S. The House of God: A Novel. New York: R. Marek Publishers, 1978; chapter 18.

- Lilly CM, Swami S, Liu X, Riker RR, Badawi O. Five year trends of critical care practice and outcomes. Chest 2017; 152(4):723–735. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.050

- Yoo EJ, Edwards JD, Dean ML, Dudley RA. Multidisciplinary critical care and intensivist staffing: results of a statewide survey and association with mortality. J Intensive Care Med 2016; 31(5):325–332. doi:10.1177/0885066614534605

- Levy MM, Rapoport J, Lemeshow S, Chalfin DB, Phillips G, Danis M. Association between critical care physician management and patient mortality in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148(11):801–809. pmid:18519926

- Vincent JL, Singer M, Marini JJ, et al. Thirty years of critical care medicine. Crit Care 2010; 14(3):311. doi:10.1186/cc8979

- Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(6):1070–1077. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x

- Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, et al; ProVent Study Group Investigators. The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med 2015; 43(2):282–287. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000710

- Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ. Long term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA 2010; 303(22):2253–2259. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.761

- Golovyan DM, Khan SH, Wang S, Khan BA. What should I address at follow-up of patients who survive critical illness? Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(7):523–526. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17104

Optimizing calcium and vitamin D intake through diet and supplements

Although calcium and vitamin D are often recommended for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, considerable controversy exists in terms of their safety and efficacy.1 This article highlights the issues, referring readers to reviews and meta-analyses for details and providing some practical advice for patients requiring supplementation.

CALCIUM INTAKE AND BONE DENSITY

Calcium enters the body through diet and supplementation. If intake is low, blood calcium levels fall, resulting in secondary hyperparathyroidism, which has 3 main effects:

- Increased fractional absorption of the calcium that is consumed

- Reduced urinary excretion of calcium

- Increased bone resorption, which releases calcium into the blood,2 which explains the potential for the deleterious effect of deficient intake of calcium on bone.3

Based on the simple physiology outlined above, it seems logical that insufficient intake of calcium over time could lead to mobilization of calcium from bone, lower bone mineral density, and higher fracture risk.3 This topic has been reviewed by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis, and Musculoskeletal Diseases and the International Foundation for Osteoporosis.1

Many lines of evidence suggest that low calcium intake adversely affects bone mineral density.1 Low calcium intake has been associated with lower bone density in some cross-sectional studies,4–6 though not all.7 Interventions to increase calcium intake in postmenopausal women have shown beneficial effects on bone density,8–10 though in some studies the benefit was small and nonprogressive.11 The question is whether this improvement in bone mineral density translates into fewer fractures.

Results from individual studies looking at fracture prevention through calcium supplementation have been conflicting,10,12–14 and reviews and meta-analyses have summarized the data.1,3,15 A recent review of these meta-analyses showed a small but significant reduction in some types of fracture.1

Some speculate that the difficulty in demonstrating fracture efficacy might be due to imperfect compliance with calcium intake, and that the participants in the placebo groups often had fairly robust calcium intake from diet and off-study supplemental intake, which could reduce the sensitivity of studies to demonstrate the fracture benefit.1,16

The US Preventive Services Task Force17 recommends that the general public not take supplemental calcium for skeletal health, but emphasizes that this recommendation does not apply to patients with osteoporosis. Most other official guidelines (eg, those of the Endocrine Society,18 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists,19 Institute of Medicine,20 and National Osteoporosis Foundation21) recommend adequate calcium intake to optimize skeletal health.

CALCIUM INTAKE AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Patients often wonder if the calcium in their supplements ends up in their coronary arteries rather than their bones. Although we once dismissed such concerns, several studies and meta-analyses have reported higher rates of cardiovascular disease with supplemental calcium use.22–24 A proposed mechanism to explain this increased risk is that taking calcium supplements transiently raises the serum calcium level, resulting in calcium deposition in coronary arteries, accelerating atherosclerosis formation.25

On the other hand, some studies and meta-analyses have not shown any increased risk of cardiovascular disease with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.26,27 This subject has been reviewed by Harvey et al.1

Our conclusions are as follows:

Patients should be told that the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology released a statement in 2016 adopting the position that calcium intake from food and supplements should be considered safe from a cardiovascular perspective.28

If patients want to avoid the possible increase in risk of cardiovascular disease due to calcium supplementation, they can optimize their calcium intake with dietary calcium. Observational studies that showed increased risk with supplemental calcium found no such increase in cardiovascular disease with a robust dietary intake of calcium.29

This is not to say that patients should be encouraged to boost their dietary calcium intake and avoid heart disease by eating more cheese and ice cream, as these foods are high in saturated fats and cholesterol. Many dairy and nondairy sources of calcium do not contain these undesirable nutrients.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATION AND NEPHROLITHIASIS

High dietary calcium intake has not been shown to increase the risk of kidney stones.

In the Nurses’ Health Study, the multivariate relative risk of stone formation was 0.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.5–0.83) in those in the highest vs the lowest quintiles of dietary calcium intake.30 In contrast, the relative risk of stones in those taking calcium supplements was 1.2 (CI 1.02–1.41),30 although this higher risk was not seen in younger women (ages 27 to 44).31

Similar results were seen in the Women’s Health Initiative, in which calcium carbonate and vitamin D supplements resulted in a relative increased risk of stone formation of 1.17 (95% CI 1.02–1.34) compared with women on placebo.12

Data from male stone-formers also suggests that high dietary calcium intake does not increase the risk of stones.32

A theory to explain the difference between dietary and supplemental calcium with respect to stone formation is that dietary calcium binds to oxalate in the gut and reduces its absorption. The most common type of kidney stones are composed of calcium oxalate, and the oxalate, not the calcium, may be the real culprit. In contrast, calcium supplements are often taken between meals and therefore do not exert this protective effect and may be absorbed more rapidly and raise the serum calcium level more, which could lead to higher urinary calcium excretion.33

CALCIUM INTAKE IN PATIENTS TAKING ANTIRESORPTIVE DRUGS

Patients often mistakenly think that calcium and vitamin D supplements are given for mild cases of bone loss, and that if their bone loss is significant enough to require a medication, then they no longer need calcium and vitamin D supplements. Most clinical trials showing bone mineral density and fracture benefit from antiresorptive therapy were in patients who were taking enough calcium and vitamin D, so the efficacy of antiresorptive therapy is most clear only when taking enough calcium and vitamin D.34,35

Furthermore, patients with inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake essentially maintain their serum calcium levels by mobilizing calcium from bone; the combination of insufficient calcium intake and administration of agents that interfere with the ability to mobilize calcium from bone may put patients at risk of hypocalcemia.36

OPTIMIZING INTAKE OF CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D

Diet is key to calcium intake. People should consume adequate amounts of calcium-rich foods regardless of whether they have a history of kidney stones, since robust dietary intake of calcium does not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease or kidney stones and may actually have a protective effect. We also remain skeptical of the concern that supplemental calcium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

We recommend a target total calcium intake from diet, and if necessary, supplements, of 1,000 to 1,200 mg daily, and not to worry about cardiovascular disease or kidney stones. A patient or clinician reluctant to push calcium intake that high with supplements might opt for a more conservative goal of 800 mg of calcium daily. This recommendation is based on data suggesting that in the presence of vitamin D sufficiency, calcium supplementation with 500 mg of calcium citrate does little for patients whose calcium intake is above 400 mg/day.37

Vitamin D: How much do we need?

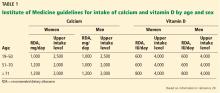

Regarding vitamin D intake, the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 to 800 IU to achieve a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 20 to 40 ng/mL.20

The Endocrine Society recommends “at least” 600 to 800 IU, but says that 1,500 to 2,000 IU may be needed to get the 25-hydroxyvitamin D level to 30 to 60 ng/mL.18

The Institute of Medicine based its recommendation on randomized controlled trials that showed fewer fractures with vitamin D intakes of 600 to 800 IU/day.13,14 Also, observational studies show little further reduction in fracture risk when the 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels rise above 20 ng/mL.38 A case-control study found an association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels higher than 40 ng/mL and pancreatic cancer.39

The Endocrine Society guidelines recommended higher intakes and levels of vitamin D because there are data suggesting that vitamin D levels higher than 30 ng/mL suppress parathyroid hormone levels further, which should favor less mobilization of bone.40

Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in people exposed to plenty of sunlight rarely go above 60 ng/mL, suggesting 60 ng/mL should be the upper limit of levels to target, and it is unlikely that such levels are harmful.41

Implementing either recommendation—a target 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 20 to 40 ng/mL or 30 to 60 ng/mL—is reasonable.

CALCULATING A PATIENT’S DIETARY CALCIUM INTAKE

A detailed dietary history can be obtained by a dietitian, or by using the Calcium Calculator app supported by the International Osteoporosis Foundation.43 However, dietary calcium intake can be assessed quickly. To approximate a patient’s total dietary calcium intake (in milligrams), we multiply the number of servings of dietary calcium by 300. A serving of dietary calcium is found in:

- 1 cup of milk, yogurt, calcium-fortified juice, almonds, cooked spinach, or collard greens

- 1.5 ounces of hard cheese

- 2 cups of ice cream, cottage cheese, or beans

- 4 ounces of tofu or canned fish with bones such as salmon or sardines.

Therefore, if a patient consumes 1 cup of milk daily and 1 cup of yogurt 3 times a week, she takes in an estimated 1.5 servings of dietary calcium daily, or 450 mg. What the patient does not receive in the diet should be made up with supplemental calcium.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS

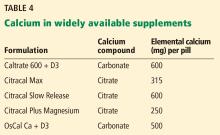

Calcium citrate has certain advantages as a supplement. Calcium carbonate requires gastric acidity to be absorbed and is therefore better absorbed if taken with meals; however, calcium citrate is equally well absorbed in the fasting or fed state and so can be taken without regard for achlorhydria or timing of meals.44

Another potential advantage of calcium citrate is that it has never been shown to increase the risk of kidney stones the way calcium carbonate has.12 Further, potassium citrate is a treatment for certain types of kidney stones,45 and it is possible that when calcium is given as citrate there is less danger of kidney stones.46 For these reasons, we generally recommend calcium citrate over other forms of calcium.

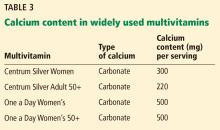

The brand of calcium citrate most readily available is Citracal, but any version of calcium citrate is acceptable.

SOURCES OF CONFUSION

Labels that describe calcium content of supplements are often misleading, and this lack of clarity can interfere with the patient’s ability to correctly identify how much calcium is in each pill.

Serving size. Whereas 1 serving of Caltrate is 1 pill, 1 serving of Tums or Citracal is 2 pills; for other brands a serving may be 3 or 4 pills.

Calcium salt vs elemental calcium. The amount of elemental calcium contained in different calcium salts varies according to the molecular weight of the salt: 1,000 mg of calcium carbonate has 400 mg of elemental calcium, while 1,000 mg of calcium citrate has 200 mg of elemental calcium.

When we recommend 1,000 to 1,200 mg of calcium daily, we mean the amount of elemental calcium. The label on calcium supplements usually indicates the amount of elemental calcium, but some have confusing information about the amount of calcium salt they contain. For instance, Tums lists the amount of calcium carbonate per pill on the top of the label, but elsewhere lists the amount of elemental calcium.

Same brand, different preparation. Some brands of calcium have more than 1 formulation, each with a different amount of calcium. For instance, Citracal has a maximum-strength 315-mg tablet and a “petite” 200-mg tablet. Careful reading of the label is required to make sure that the patient is getting the amount of calcium she thinks she is getting.

OPTIONS FOR THOSE WITH DIFFICULTY SWALLOWING LARGE PILLS

Many calcium pills are large and difficult to swallow. Patients often ask if calcium pills can be crushed, and the answer is that they certainly can, but this approach is cumbersome and usually results in patients eventually stopping calcium in frustration.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS AND CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a common side effect of calcium supplementation.47 Many patients report that they cannot take a calcium supplement because of constipation, or ask if there are calcium preparations that are less constipating than others.

There are ways of overcoming the constipating effects of calcium. Osmotic laxatives and stool softeners such as polyethylene glycol, magnesium citrate, and docusate sodium are safe and effective, although patients are often reluctant to take a medicine to combat the side effects from another medicine.

In such circumstances patients are often amenable to taking a combination product such as calcium with magnesium, since the cathartic effects of magnesium nicely counteract the constipating effects of calcium. This idea is exploited in antacids such as Rolaids, which are combinations of calcium carbonate and magnesium oxide that usually have no net effect on stool consistency.47

Many patients believe that calcium must be combined with magnesium to be absorbed. Although there are no data to support this idea, a patient already harboring this misconception may be more amenable to calcium-magnesium combinations for the purpose of avoiding constipation.

If a patient cannot find a calcium preparation that she can take at the full recommended doses, we often suggest starting with a very small dose for 2 weeks, and then adjusting the dose upward every 2 weeks until reaching the maximum dose that the patient can tolerate. Even if the dose is well below recommended doses, most of the benefit of calcium is obtained by bringing total intake to more than 500 mg daily,37 so continued use should be encouraged even when optimal targets cannot be sustained.

For patients who cannot tolerate enough calcium, we recommend being especially sure to optimize the vitamin D levels, since there are studies that suggest that secondary hyperparathyroidism mostly occurs in states of low calcium intake if vitamin D levels are insufficient.48

If the patient has secondary hyperparathyroidism despite best attempts at supplementation with calcium and vitamin D, consider prescribing calcitriol (activated vitamin D), which stimulates gut absorption of whatever calcium is taken.49 If calcitriol is given, the patient must undergo cumbersome monitoring for hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria. Fortunately, it is unusual to require calcitriol unless the patient has significant structural gastrointestinal abnormalities such as gastric bypass or Crohn disease.

- Harvey NC, Bilver E, Kaufman JM, et al. The role of calcium supplementation in healthy musculoskeletal ageing: an expert consensus meeting of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) and the International Foundation for Osteoporosis (IOF). Osteoporos Int 2017; 28(2):447–462. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3773-6

- Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest 2005; 115(12):3318–3325. doi.10.1172/JCI27071

- Bauer DC. Clinical practice. Calcium supplements and fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(16):1537–154 doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1210380

- Choi MJ, Park EJ, Jo HJ. Relationship of nutrient intakes and bone mineral density of elderly women in Daegu, Korea. Nutr Res Pract 2007; 1(4):328–33 doi:10.4162/nrp.2007.1.4.328

- Kim KM, Choi SH, Lim S, et al. Interactions between dietary calcium intake and bone mineral density or bone ge6ometry in a low calcium intake population (KNHANES IV 2008–2010). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99(7):2409–2417. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1006

- Joo NS, Dawson-Hughes B, Kim YS, Oh K, Yeum KJ. Impact of calcium and vitamin D insufficiencies on serum parathyroid hormone and bone mineral density: analysis of the fourth and fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV-3, 2009 and KNHANES V-1, 2010). J Bone Miner Res 2013; 28(4):764–770. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1790

- Anderson JJ, Roggenkamp KJ, Suchindran CM. Calcium intakes and femoral and lumbar bone density of elderly US men and women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006 analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(12):4531–4539. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1407

- Gui JC, Brašic JR, Liu XD, et al. Bone mineral density in postmenopausal Chinese women treated with calcium fortification in soymilk and cow’s milk. Osteoporos Int 2012; 23(5):1563–1570. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-1895-z

- Moschonis G, Katsaroli I, Lyritis GP, Manios Y. The effects of a 30-month dietary intervention on bone mineral density: the Postmenopausal Health Study. Br J Nutr 2010; 104(1):100–107. doi:10.1017/S000711451000019X

- Recker RR, Hinders S, Davies KM, et al. Correcting calcium nutritional deficiency prevents spine fractures in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 1996; 11(12):1961–1966. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650111218

- Tai V, Leung W, Grey A, Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Calcium intake and bone mineral density: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015; 351:h4183. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4183

- Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(7):669–683. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055218

- Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med 1992; 327(23):1637–1642. doi:10.1056/NEJM199212033272305

- Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 1997; 337(10):670–676. doi:10.1056/NEJM199709043371003

- Bolland MJ, Leung W, Tai V, et al. Calcium intake and risk of fracture: systematic review. BMJ 2015; 351:h4580. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4580

- Heaney RP. Vitamin D—baseline status and effective dose. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(1):77–78. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1206858

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(9):691–696. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-9-201305070-00603

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96(7):1911–1930. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385

- Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologist and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—2016. Endocr Pract 2016; 22(suppl 4):1–42. doi:10.4158/EP161435.ESGL

- Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96(1):53–58. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2704

- Cosman F, De Beur SJ, Leboff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25(10):2359–2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

- Bolland MJ, Barber PA, Doughty RN, et al. Vascular events in healthy older women receiving calcium supplementation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008; 336(7638):262–266. doi:10.1136/bmj.39440.525752.BE

- Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011; 342:d2040. doi:10.1136/bmj.d2040

- Mao PJ, Zhang C, Tang L, et al. Effect of calcium or vitamin D supplementation on vascular outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol 2013; 169(2):106–111. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.055

- Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Calcium supplementation and vascular disease. Climacteric 2008; 11(4):280–286. doi:10.1080/13697130802229639

- Lewis JR, Radavelli-Bagatini S, Rejnmark L, et al. The effects of calcium supplementation on verified coronary heart disease hospitalization and death in postmenopausal women: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Miner Res 2015; 30(1):165–175. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2311

- Hsia J, Heiss G, Ren H, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Calcium/vitamin D supplementation and cardiovascular events. Circulation 2007; 115(19):846–854. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.673491

- Kopecky SL, Bauer DC, Gulati M, et al. Lack of evidence linking calcium with or without vitamin D supplementation to cardiovascular disease in generally healthy adults: a clinical guideline from the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165(12):867–868. doi:10.7326/M16-1743

- Anderson JJ, Kruszka B, Delaney JA, et al. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5(10):e003815. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003815

- Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Spiegelman D, Stampfer MJ. Comparison of dietary calcium with supplemental calcium and other nutrients as factors affecting the risk for kidney stones in women. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(7):497–504. pmid:9092314

- Curhan GC, Willett WC, Knight EL, Stampfer MJ. Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in younger women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(8):885–891. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.8.885

- Borhi L, Schianchi T, Meschi T, et al. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(2):77–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010369

- Prochaska ML, Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Insights into nephrolithiasis from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(9):1638–1643. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303319

- Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 1996; 348(9041):1535–1541. pmid:8950879

- Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al; HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356(18):1809–1822. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067312

- Chen J, Smerdely P. Hypocalcaemia after denosumab in older people following fracture. Osteoporos Int 2017; 28(2):517–522. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3755-8

- Dawson-Hughes B, Dallal GE, Krall EA, Sadowski L, Sahyoun N, Tannenbaum S. A controlled trial of the effect of calcium supplementation on bone density in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 1990; 323(13):878–883. doi:10.1056/NEJM199009273231305

- Melhus H, Snellman G, Gedeborg R, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and fracture risk in a community-based cohort of elderly men in Sweden. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(6):2637–2645. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2699

- Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Jacobs EJ, Arslan AA. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of pancreatic cancer: Cohort Consortium Vitamin D Pooling Project of Rarer Cancers. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172(1):81–93. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq120

- Valcour A, Blocki F, Hawkins DM, Rao SD. Effects of age and serum 25-OH-vitamin D on serum parathyroid hormone levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(11):3989–3995. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2276

- Binkley N, Novotny R, Krueger T, et al. Low vitamin D status despite abundant sun exposure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92(6):2130–2135. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2250

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Agricultural Research Service. USDA food composition databases. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/search/list. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. IOF calcium calculator version 1.10. Apple App Store. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/iof-calcium-calculator/id956198268?mt=8. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- Recker RR. Calcium absorption and achlorhydria. N Engl J Med 1985; 313(2):70–73. doi:10.1056/NEJM198507113130202

- Coe FL, Evan A, Worcester E. Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest 2005; 115(10):2598–2608. doi:10.1172/JCI26662

- Sakhaee K, Poindexter JR, Griffith CS, Pak CY. Stone forming risk of calcium citrate supplementation in healthy postmenopausal women. J Urol 2004; 172(3):958–961. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000136400.14728.cd

- Kitchin B. Nutrition counseling for patients with osteoporosis: a personal approach. J Clin Densitom 2013; 16(4):426–431. doi:10.1016/j.jocd.2013.08.013

- Steingrimsdottir L, Gunnarsson O, Indridason OS, Franzson L, Sigurdsson G. Relationship between serum parathyroid hormone levels, vitamin D sufficiency, and calcium intake. JAMA 2005; 294(18):2336–2341. doi:10.1001/jama.294.18.2336

- Need AG, Horowitz M, Philcox JC, Nordin BE. 1,25-dihydroxycalciferol and calcium therapy in osteoporosis with calcium malabsorption. Dose response relationship of calcium absorption and indices of bone turnover. Miner Electrolyte Metab 1985; 11(1):35–40. pmid:3838358

Although calcium and vitamin D are often recommended for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, considerable controversy exists in terms of their safety and efficacy.1 This article highlights the issues, referring readers to reviews and meta-analyses for details and providing some practical advice for patients requiring supplementation.

CALCIUM INTAKE AND BONE DENSITY

Calcium enters the body through diet and supplementation. If intake is low, blood calcium levels fall, resulting in secondary hyperparathyroidism, which has 3 main effects:

- Increased fractional absorption of the calcium that is consumed

- Reduced urinary excretion of calcium

- Increased bone resorption, which releases calcium into the blood,2 which explains the potential for the deleterious effect of deficient intake of calcium on bone.3

Based on the simple physiology outlined above, it seems logical that insufficient intake of calcium over time could lead to mobilization of calcium from bone, lower bone mineral density, and higher fracture risk.3 This topic has been reviewed by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis, and Musculoskeletal Diseases and the International Foundation for Osteoporosis.1

Many lines of evidence suggest that low calcium intake adversely affects bone mineral density.1 Low calcium intake has been associated with lower bone density in some cross-sectional studies,4–6 though not all.7 Interventions to increase calcium intake in postmenopausal women have shown beneficial effects on bone density,8–10 though in some studies the benefit was small and nonprogressive.11 The question is whether this improvement in bone mineral density translates into fewer fractures.

Results from individual studies looking at fracture prevention through calcium supplementation have been conflicting,10,12–14 and reviews and meta-analyses have summarized the data.1,3,15 A recent review of these meta-analyses showed a small but significant reduction in some types of fracture.1

Some speculate that the difficulty in demonstrating fracture efficacy might be due to imperfect compliance with calcium intake, and that the participants in the placebo groups often had fairly robust calcium intake from diet and off-study supplemental intake, which could reduce the sensitivity of studies to demonstrate the fracture benefit.1,16

The US Preventive Services Task Force17 recommends that the general public not take supplemental calcium for skeletal health, but emphasizes that this recommendation does not apply to patients with osteoporosis. Most other official guidelines (eg, those of the Endocrine Society,18 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists,19 Institute of Medicine,20 and National Osteoporosis Foundation21) recommend adequate calcium intake to optimize skeletal health.

CALCIUM INTAKE AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Patients often wonder if the calcium in their supplements ends up in their coronary arteries rather than their bones. Although we once dismissed such concerns, several studies and meta-analyses have reported higher rates of cardiovascular disease with supplemental calcium use.22–24 A proposed mechanism to explain this increased risk is that taking calcium supplements transiently raises the serum calcium level, resulting in calcium deposition in coronary arteries, accelerating atherosclerosis formation.25

On the other hand, some studies and meta-analyses have not shown any increased risk of cardiovascular disease with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.26,27 This subject has been reviewed by Harvey et al.1

Our conclusions are as follows:

Patients should be told that the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology released a statement in 2016 adopting the position that calcium intake from food and supplements should be considered safe from a cardiovascular perspective.28

If patients want to avoid the possible increase in risk of cardiovascular disease due to calcium supplementation, they can optimize their calcium intake with dietary calcium. Observational studies that showed increased risk with supplemental calcium found no such increase in cardiovascular disease with a robust dietary intake of calcium.29

This is not to say that patients should be encouraged to boost their dietary calcium intake and avoid heart disease by eating more cheese and ice cream, as these foods are high in saturated fats and cholesterol. Many dairy and nondairy sources of calcium do not contain these undesirable nutrients.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATION AND NEPHROLITHIASIS

High dietary calcium intake has not been shown to increase the risk of kidney stones.

In the Nurses’ Health Study, the multivariate relative risk of stone formation was 0.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.5–0.83) in those in the highest vs the lowest quintiles of dietary calcium intake.30 In contrast, the relative risk of stones in those taking calcium supplements was 1.2 (CI 1.02–1.41),30 although this higher risk was not seen in younger women (ages 27 to 44).31

Similar results were seen in the Women’s Health Initiative, in which calcium carbonate and vitamin D supplements resulted in a relative increased risk of stone formation of 1.17 (95% CI 1.02–1.34) compared with women on placebo.12

Data from male stone-formers also suggests that high dietary calcium intake does not increase the risk of stones.32

A theory to explain the difference between dietary and supplemental calcium with respect to stone formation is that dietary calcium binds to oxalate in the gut and reduces its absorption. The most common type of kidney stones are composed of calcium oxalate, and the oxalate, not the calcium, may be the real culprit. In contrast, calcium supplements are often taken between meals and therefore do not exert this protective effect and may be absorbed more rapidly and raise the serum calcium level more, which could lead to higher urinary calcium excretion.33

CALCIUM INTAKE IN PATIENTS TAKING ANTIRESORPTIVE DRUGS

Patients often mistakenly think that calcium and vitamin D supplements are given for mild cases of bone loss, and that if their bone loss is significant enough to require a medication, then they no longer need calcium and vitamin D supplements. Most clinical trials showing bone mineral density and fracture benefit from antiresorptive therapy were in patients who were taking enough calcium and vitamin D, so the efficacy of antiresorptive therapy is most clear only when taking enough calcium and vitamin D.34,35

Furthermore, patients with inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake essentially maintain their serum calcium levels by mobilizing calcium from bone; the combination of insufficient calcium intake and administration of agents that interfere with the ability to mobilize calcium from bone may put patients at risk of hypocalcemia.36

OPTIMIZING INTAKE OF CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D

Diet is key to calcium intake. People should consume adequate amounts of calcium-rich foods regardless of whether they have a history of kidney stones, since robust dietary intake of calcium does not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease or kidney stones and may actually have a protective effect. We also remain skeptical of the concern that supplemental calcium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

We recommend a target total calcium intake from diet, and if necessary, supplements, of 1,000 to 1,200 mg daily, and not to worry about cardiovascular disease or kidney stones. A patient or clinician reluctant to push calcium intake that high with supplements might opt for a more conservative goal of 800 mg of calcium daily. This recommendation is based on data suggesting that in the presence of vitamin D sufficiency, calcium supplementation with 500 mg of calcium citrate does little for patients whose calcium intake is above 400 mg/day.37

Vitamin D: How much do we need?

Regarding vitamin D intake, the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 to 800 IU to achieve a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 20 to 40 ng/mL.20

The Endocrine Society recommends “at least” 600 to 800 IU, but says that 1,500 to 2,000 IU may be needed to get the 25-hydroxyvitamin D level to 30 to 60 ng/mL.18

The Institute of Medicine based its recommendation on randomized controlled trials that showed fewer fractures with vitamin D intakes of 600 to 800 IU/day.13,14 Also, observational studies show little further reduction in fracture risk when the 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels rise above 20 ng/mL.38 A case-control study found an association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels higher than 40 ng/mL and pancreatic cancer.39

The Endocrine Society guidelines recommended higher intakes and levels of vitamin D because there are data suggesting that vitamin D levels higher than 30 ng/mL suppress parathyroid hormone levels further, which should favor less mobilization of bone.40

Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in people exposed to plenty of sunlight rarely go above 60 ng/mL, suggesting 60 ng/mL should be the upper limit of levels to target, and it is unlikely that such levels are harmful.41

Implementing either recommendation—a target 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 20 to 40 ng/mL or 30 to 60 ng/mL—is reasonable.

CALCULATING A PATIENT’S DIETARY CALCIUM INTAKE

A detailed dietary history can be obtained by a dietitian, or by using the Calcium Calculator app supported by the International Osteoporosis Foundation.43 However, dietary calcium intake can be assessed quickly. To approximate a patient’s total dietary calcium intake (in milligrams), we multiply the number of servings of dietary calcium by 300. A serving of dietary calcium is found in:

- 1 cup of milk, yogurt, calcium-fortified juice, almonds, cooked spinach, or collard greens

- 1.5 ounces of hard cheese

- 2 cups of ice cream, cottage cheese, or beans

- 4 ounces of tofu or canned fish with bones such as salmon or sardines.

Therefore, if a patient consumes 1 cup of milk daily and 1 cup of yogurt 3 times a week, she takes in an estimated 1.5 servings of dietary calcium daily, or 450 mg. What the patient does not receive in the diet should be made up with supplemental calcium.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS

Calcium citrate has certain advantages as a supplement. Calcium carbonate requires gastric acidity to be absorbed and is therefore better absorbed if taken with meals; however, calcium citrate is equally well absorbed in the fasting or fed state and so can be taken without regard for achlorhydria or timing of meals.44

Another potential advantage of calcium citrate is that it has never been shown to increase the risk of kidney stones the way calcium carbonate has.12 Further, potassium citrate is a treatment for certain types of kidney stones,45 and it is possible that when calcium is given as citrate there is less danger of kidney stones.46 For these reasons, we generally recommend calcium citrate over other forms of calcium.

The brand of calcium citrate most readily available is Citracal, but any version of calcium citrate is acceptable.

SOURCES OF CONFUSION

Labels that describe calcium content of supplements are often misleading, and this lack of clarity can interfere with the patient’s ability to correctly identify how much calcium is in each pill.

Serving size. Whereas 1 serving of Caltrate is 1 pill, 1 serving of Tums or Citracal is 2 pills; for other brands a serving may be 3 or 4 pills.

Calcium salt vs elemental calcium. The amount of elemental calcium contained in different calcium salts varies according to the molecular weight of the salt: 1,000 mg of calcium carbonate has 400 mg of elemental calcium, while 1,000 mg of calcium citrate has 200 mg of elemental calcium.

When we recommend 1,000 to 1,200 mg of calcium daily, we mean the amount of elemental calcium. The label on calcium supplements usually indicates the amount of elemental calcium, but some have confusing information about the amount of calcium salt they contain. For instance, Tums lists the amount of calcium carbonate per pill on the top of the label, but elsewhere lists the amount of elemental calcium.

Same brand, different preparation. Some brands of calcium have more than 1 formulation, each with a different amount of calcium. For instance, Citracal has a maximum-strength 315-mg tablet and a “petite” 200-mg tablet. Careful reading of the label is required to make sure that the patient is getting the amount of calcium she thinks she is getting.

OPTIONS FOR THOSE WITH DIFFICULTY SWALLOWING LARGE PILLS

Many calcium pills are large and difficult to swallow. Patients often ask if calcium pills can be crushed, and the answer is that they certainly can, but this approach is cumbersome and usually results in patients eventually stopping calcium in frustration.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS AND CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a common side effect of calcium supplementation.47 Many patients report that they cannot take a calcium supplement because of constipation, or ask if there are calcium preparations that are less constipating than others.

There are ways of overcoming the constipating effects of calcium. Osmotic laxatives and stool softeners such as polyethylene glycol, magnesium citrate, and docusate sodium are safe and effective, although patients are often reluctant to take a medicine to combat the side effects from another medicine.

In such circumstances patients are often amenable to taking a combination product such as calcium with magnesium, since the cathartic effects of magnesium nicely counteract the constipating effects of calcium. This idea is exploited in antacids such as Rolaids, which are combinations of calcium carbonate and magnesium oxide that usually have no net effect on stool consistency.47

Many patients believe that calcium must be combined with magnesium to be absorbed. Although there are no data to support this idea, a patient already harboring this misconception may be more amenable to calcium-magnesium combinations for the purpose of avoiding constipation.

If a patient cannot find a calcium preparation that she can take at the full recommended doses, we often suggest starting with a very small dose for 2 weeks, and then adjusting the dose upward every 2 weeks until reaching the maximum dose that the patient can tolerate. Even if the dose is well below recommended doses, most of the benefit of calcium is obtained by bringing total intake to more than 500 mg daily,37 so continued use should be encouraged even when optimal targets cannot be sustained.

For patients who cannot tolerate enough calcium, we recommend being especially sure to optimize the vitamin D levels, since there are studies that suggest that secondary hyperparathyroidism mostly occurs in states of low calcium intake if vitamin D levels are insufficient.48

If the patient has secondary hyperparathyroidism despite best attempts at supplementation with calcium and vitamin D, consider prescribing calcitriol (activated vitamin D), which stimulates gut absorption of whatever calcium is taken.49 If calcitriol is given, the patient must undergo cumbersome monitoring for hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria. Fortunately, it is unusual to require calcitriol unless the patient has significant structural gastrointestinal abnormalities such as gastric bypass or Crohn disease.

Although calcium and vitamin D are often recommended for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, considerable controversy exists in terms of their safety and efficacy.1 This article highlights the issues, referring readers to reviews and meta-analyses for details and providing some practical advice for patients requiring supplementation.

CALCIUM INTAKE AND BONE DENSITY

Calcium enters the body through diet and supplementation. If intake is low, blood calcium levels fall, resulting in secondary hyperparathyroidism, which has 3 main effects:

- Increased fractional absorption of the calcium that is consumed

- Reduced urinary excretion of calcium

- Increased bone resorption, which releases calcium into the blood,2 which explains the potential for the deleterious effect of deficient intake of calcium on bone.3

Based on the simple physiology outlined above, it seems logical that insufficient intake of calcium over time could lead to mobilization of calcium from bone, lower bone mineral density, and higher fracture risk.3 This topic has been reviewed by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis, and Musculoskeletal Diseases and the International Foundation for Osteoporosis.1

Many lines of evidence suggest that low calcium intake adversely affects bone mineral density.1 Low calcium intake has been associated with lower bone density in some cross-sectional studies,4–6 though not all.7 Interventions to increase calcium intake in postmenopausal women have shown beneficial effects on bone density,8–10 though in some studies the benefit was small and nonprogressive.11 The question is whether this improvement in bone mineral density translates into fewer fractures.

Results from individual studies looking at fracture prevention through calcium supplementation have been conflicting,10,12–14 and reviews and meta-analyses have summarized the data.1,3,15 A recent review of these meta-analyses showed a small but significant reduction in some types of fracture.1

Some speculate that the difficulty in demonstrating fracture efficacy might be due to imperfect compliance with calcium intake, and that the participants in the placebo groups often had fairly robust calcium intake from diet and off-study supplemental intake, which could reduce the sensitivity of studies to demonstrate the fracture benefit.1,16

The US Preventive Services Task Force17 recommends that the general public not take supplemental calcium for skeletal health, but emphasizes that this recommendation does not apply to patients with osteoporosis. Most other official guidelines (eg, those of the Endocrine Society,18 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists,19 Institute of Medicine,20 and National Osteoporosis Foundation21) recommend adequate calcium intake to optimize skeletal health.

CALCIUM INTAKE AND CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Patients often wonder if the calcium in their supplements ends up in their coronary arteries rather than their bones. Although we once dismissed such concerns, several studies and meta-analyses have reported higher rates of cardiovascular disease with supplemental calcium use.22–24 A proposed mechanism to explain this increased risk is that taking calcium supplements transiently raises the serum calcium level, resulting in calcium deposition in coronary arteries, accelerating atherosclerosis formation.25

On the other hand, some studies and meta-analyses have not shown any increased risk of cardiovascular disease with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.26,27 This subject has been reviewed by Harvey et al.1

Our conclusions are as follows:

Patients should be told that the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology released a statement in 2016 adopting the position that calcium intake from food and supplements should be considered safe from a cardiovascular perspective.28

If patients want to avoid the possible increase in risk of cardiovascular disease due to calcium supplementation, they can optimize their calcium intake with dietary calcium. Observational studies that showed increased risk with supplemental calcium found no such increase in cardiovascular disease with a robust dietary intake of calcium.29

This is not to say that patients should be encouraged to boost their dietary calcium intake and avoid heart disease by eating more cheese and ice cream, as these foods are high in saturated fats and cholesterol. Many dairy and nondairy sources of calcium do not contain these undesirable nutrients.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATION AND NEPHROLITHIASIS

High dietary calcium intake has not been shown to increase the risk of kidney stones.

In the Nurses’ Health Study, the multivariate relative risk of stone formation was 0.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.5–0.83) in those in the highest vs the lowest quintiles of dietary calcium intake.30 In contrast, the relative risk of stones in those taking calcium supplements was 1.2 (CI 1.02–1.41),30 although this higher risk was not seen in younger women (ages 27 to 44).31

Similar results were seen in the Women’s Health Initiative, in which calcium carbonate and vitamin D supplements resulted in a relative increased risk of stone formation of 1.17 (95% CI 1.02–1.34) compared with women on placebo.12

Data from male stone-formers also suggests that high dietary calcium intake does not increase the risk of stones.32

A theory to explain the difference between dietary and supplemental calcium with respect to stone formation is that dietary calcium binds to oxalate in the gut and reduces its absorption. The most common type of kidney stones are composed of calcium oxalate, and the oxalate, not the calcium, may be the real culprit. In contrast, calcium supplements are often taken between meals and therefore do not exert this protective effect and may be absorbed more rapidly and raise the serum calcium level more, which could lead to higher urinary calcium excretion.33

CALCIUM INTAKE IN PATIENTS TAKING ANTIRESORPTIVE DRUGS

Patients often mistakenly think that calcium and vitamin D supplements are given for mild cases of bone loss, and that if their bone loss is significant enough to require a medication, then they no longer need calcium and vitamin D supplements. Most clinical trials showing bone mineral density and fracture benefit from antiresorptive therapy were in patients who were taking enough calcium and vitamin D, so the efficacy of antiresorptive therapy is most clear only when taking enough calcium and vitamin D.34,35

Furthermore, patients with inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake essentially maintain their serum calcium levels by mobilizing calcium from bone; the combination of insufficient calcium intake and administration of agents that interfere with the ability to mobilize calcium from bone may put patients at risk of hypocalcemia.36

OPTIMIZING INTAKE OF CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D

Diet is key to calcium intake. People should consume adequate amounts of calcium-rich foods regardless of whether they have a history of kidney stones, since robust dietary intake of calcium does not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease or kidney stones and may actually have a protective effect. We also remain skeptical of the concern that supplemental calcium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

We recommend a target total calcium intake from diet, and if necessary, supplements, of 1,000 to 1,200 mg daily, and not to worry about cardiovascular disease or kidney stones. A patient or clinician reluctant to push calcium intake that high with supplements might opt for a more conservative goal of 800 mg of calcium daily. This recommendation is based on data suggesting that in the presence of vitamin D sufficiency, calcium supplementation with 500 mg of calcium citrate does little for patients whose calcium intake is above 400 mg/day.37

Vitamin D: How much do we need?

Regarding vitamin D intake, the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 to 800 IU to achieve a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 20 to 40 ng/mL.20

The Endocrine Society recommends “at least” 600 to 800 IU, but says that 1,500 to 2,000 IU may be needed to get the 25-hydroxyvitamin D level to 30 to 60 ng/mL.18

The Institute of Medicine based its recommendation on randomized controlled trials that showed fewer fractures with vitamin D intakes of 600 to 800 IU/day.13,14 Also, observational studies show little further reduction in fracture risk when the 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels rise above 20 ng/mL.38 A case-control study found an association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels higher than 40 ng/mL and pancreatic cancer.39

The Endocrine Society guidelines recommended higher intakes and levels of vitamin D because there are data suggesting that vitamin D levels higher than 30 ng/mL suppress parathyroid hormone levels further, which should favor less mobilization of bone.40

Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in people exposed to plenty of sunlight rarely go above 60 ng/mL, suggesting 60 ng/mL should be the upper limit of levels to target, and it is unlikely that such levels are harmful.41

Implementing either recommendation—a target 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 20 to 40 ng/mL or 30 to 60 ng/mL—is reasonable.

CALCULATING A PATIENT’S DIETARY CALCIUM INTAKE

A detailed dietary history can be obtained by a dietitian, or by using the Calcium Calculator app supported by the International Osteoporosis Foundation.43 However, dietary calcium intake can be assessed quickly. To approximate a patient’s total dietary calcium intake (in milligrams), we multiply the number of servings of dietary calcium by 300. A serving of dietary calcium is found in:

- 1 cup of milk, yogurt, calcium-fortified juice, almonds, cooked spinach, or collard greens

- 1.5 ounces of hard cheese

- 2 cups of ice cream, cottage cheese, or beans

- 4 ounces of tofu or canned fish with bones such as salmon or sardines.

Therefore, if a patient consumes 1 cup of milk daily and 1 cup of yogurt 3 times a week, she takes in an estimated 1.5 servings of dietary calcium daily, or 450 mg. What the patient does not receive in the diet should be made up with supplemental calcium.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS

Calcium citrate has certain advantages as a supplement. Calcium carbonate requires gastric acidity to be absorbed and is therefore better absorbed if taken with meals; however, calcium citrate is equally well absorbed in the fasting or fed state and so can be taken without regard for achlorhydria or timing of meals.44

Another potential advantage of calcium citrate is that it has never been shown to increase the risk of kidney stones the way calcium carbonate has.12 Further, potassium citrate is a treatment for certain types of kidney stones,45 and it is possible that when calcium is given as citrate there is less danger of kidney stones.46 For these reasons, we generally recommend calcium citrate over other forms of calcium.

The brand of calcium citrate most readily available is Citracal, but any version of calcium citrate is acceptable.

SOURCES OF CONFUSION

Labels that describe calcium content of supplements are often misleading, and this lack of clarity can interfere with the patient’s ability to correctly identify how much calcium is in each pill.

Serving size. Whereas 1 serving of Caltrate is 1 pill, 1 serving of Tums or Citracal is 2 pills; for other brands a serving may be 3 or 4 pills.

Calcium salt vs elemental calcium. The amount of elemental calcium contained in different calcium salts varies according to the molecular weight of the salt: 1,000 mg of calcium carbonate has 400 mg of elemental calcium, while 1,000 mg of calcium citrate has 200 mg of elemental calcium.

When we recommend 1,000 to 1,200 mg of calcium daily, we mean the amount of elemental calcium. The label on calcium supplements usually indicates the amount of elemental calcium, but some have confusing information about the amount of calcium salt they contain. For instance, Tums lists the amount of calcium carbonate per pill on the top of the label, but elsewhere lists the amount of elemental calcium.

Same brand, different preparation. Some brands of calcium have more than 1 formulation, each with a different amount of calcium. For instance, Citracal has a maximum-strength 315-mg tablet and a “petite” 200-mg tablet. Careful reading of the label is required to make sure that the patient is getting the amount of calcium she thinks she is getting.

OPTIONS FOR THOSE WITH DIFFICULTY SWALLOWING LARGE PILLS

Many calcium pills are large and difficult to swallow. Patients often ask if calcium pills can be crushed, and the answer is that they certainly can, but this approach is cumbersome and usually results in patients eventually stopping calcium in frustration.

CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTS AND CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a common side effect of calcium supplementation.47 Many patients report that they cannot take a calcium supplement because of constipation, or ask if there are calcium preparations that are less constipating than others.

There are ways of overcoming the constipating effects of calcium. Osmotic laxatives and stool softeners such as polyethylene glycol, magnesium citrate, and docusate sodium are safe and effective, although patients are often reluctant to take a medicine to combat the side effects from another medicine.

In such circumstances patients are often amenable to taking a combination product such as calcium with magnesium, since the cathartic effects of magnesium nicely counteract the constipating effects of calcium. This idea is exploited in antacids such as Rolaids, which are combinations of calcium carbonate and magnesium oxide that usually have no net effect on stool consistency.47

Many patients believe that calcium must be combined with magnesium to be absorbed. Although there are no data to support this idea, a patient already harboring this misconception may be more amenable to calcium-magnesium combinations for the purpose of avoiding constipation.

If a patient cannot find a calcium preparation that she can take at the full recommended doses, we often suggest starting with a very small dose for 2 weeks, and then adjusting the dose upward every 2 weeks until reaching the maximum dose that the patient can tolerate. Even if the dose is well below recommended doses, most of the benefit of calcium is obtained by bringing total intake to more than 500 mg daily,37 so continued use should be encouraged even when optimal targets cannot be sustained.

For patients who cannot tolerate enough calcium, we recommend being especially sure to optimize the vitamin D levels, since there are studies that suggest that secondary hyperparathyroidism mostly occurs in states of low calcium intake if vitamin D levels are insufficient.48

If the patient has secondary hyperparathyroidism despite best attempts at supplementation with calcium and vitamin D, consider prescribing calcitriol (activated vitamin D), which stimulates gut absorption of whatever calcium is taken.49 If calcitriol is given, the patient must undergo cumbersome monitoring for hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria. Fortunately, it is unusual to require calcitriol unless the patient has significant structural gastrointestinal abnormalities such as gastric bypass or Crohn disease.