User login

New IHS Website Addresses Opioid Crisis

The opioid crisis has taken a toll everywhere, but American Indians and Alaska Natives have been hardest hit. That group had the highest drug overdose death rates in 2015, and the largest percentage increase— > 500%—in the number of deaths between 1999 and 2015 compared with that of other racial and ethnic groups.

In February 2018, the IHS released the revised agency policy on chronic pain management. It also has now launched a website (www.ihs.gov/opioids) as another step in addressing the problem.

The website discusses the crisis response, funding opportunities, best practices, and proper pain management. It includes Community Opioid Action Plans, which inform the public about how indigenous planning using traditional practices and holistic, culturally appropriate approaches can help.

The website also provides resources for tribes, such as links to the Office of Tribal Affairs and Policy, the point of contact for tribal governments, tribal organizations and federal agencies on behavioral health issues that affect tribal communities; the Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse; and SAMHSA Tribal Training and Technical Assistance.

The opioid crisis has taken a toll everywhere, but American Indians and Alaska Natives have been hardest hit. That group had the highest drug overdose death rates in 2015, and the largest percentage increase— > 500%—in the number of deaths between 1999 and 2015 compared with that of other racial and ethnic groups.

In February 2018, the IHS released the revised agency policy on chronic pain management. It also has now launched a website (www.ihs.gov/opioids) as another step in addressing the problem.

The website discusses the crisis response, funding opportunities, best practices, and proper pain management. It includes Community Opioid Action Plans, which inform the public about how indigenous planning using traditional practices and holistic, culturally appropriate approaches can help.

The website also provides resources for tribes, such as links to the Office of Tribal Affairs and Policy, the point of contact for tribal governments, tribal organizations and federal agencies on behavioral health issues that affect tribal communities; the Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse; and SAMHSA Tribal Training and Technical Assistance.

The opioid crisis has taken a toll everywhere, but American Indians and Alaska Natives have been hardest hit. That group had the highest drug overdose death rates in 2015, and the largest percentage increase— > 500%—in the number of deaths between 1999 and 2015 compared with that of other racial and ethnic groups.

In February 2018, the IHS released the revised agency policy on chronic pain management. It also has now launched a website (www.ihs.gov/opioids) as another step in addressing the problem.

The website discusses the crisis response, funding opportunities, best practices, and proper pain management. It includes Community Opioid Action Plans, which inform the public about how indigenous planning using traditional practices and holistic, culturally appropriate approaches can help.

The website also provides resources for tribes, such as links to the Office of Tribal Affairs and Policy, the point of contact for tribal governments, tribal organizations and federal agencies on behavioral health issues that affect tribal communities; the Office of Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse; and SAMHSA Tribal Training and Technical Assistance.

Hispanic ALL patients face higher treatment toxicity

Hispanic pediatric patients undergoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had a risk of methotrexate toxicity that was more than twice that of non-Hispanic whites, according to results of a prospective multicenter study.

Methotrexate toxicity often led to treatment modification or delays, which may have increased relapse risk in the Hispanic patients, according to investigator Michael E. Scheurer, PhD, MPH, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his colleagues.

“We had observed that our Hispanic patients tended to experience neurotoxicity more often than other groups, but we were surprised to see the magnitude of the difference,” Dr. Scheurer said in statement.

The study, described in Clinical Cancer Research, involved 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL enrolled at one of three major U.S. pediatric cancer treatment centers. Nearly half of the patients (48.2%) were Hispanic, and approximately 86% had a diagnosis of pre B-cell leukemia.

The patients, who had a mean age of 8.4 years at diagnosis, were treated with modern ALL protocols and were followed from diagnosis to the start of maintenance/continuation therapy.

Methotrexate toxicity was seen in 39 patients at the time of the analysis. Of those patients, 29 (74.4%) were Hispanic, Dr. Scheurer and his coauthors reported.

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics had a high risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, even after the researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.43; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-5.58).

Among nine patients who experienced a second neurotoxic event, all were Hispanic.

Patients who had neurotoxicity received an average of 2.25 fewer doses of intrathecal methotrexate, and slightly lower intravenous methotrexate doses. About three-quarters of the patients experiencing methotrexate toxicity received leucovorin after intrathecal methotrexate, according to the investigators, who noted that leucovorin may interact with methotrexate and reduce efficacy.

“These findings may help us better understand what factors contribute to poorer survival among Hispanic patients with ALL,” wrote Dr. Scheurer and his coauthors.

Relapse occurred in 15.4% of patients with neurotoxicity (6 of 39 patients), and in 2.1% of patients with no neurotoxicity (13 of 241 patients).

Taken together, the findings add to the growing body of evidence that Hispanics and other minority pediatric patients with ALL experience “significant disparities” in treatment outcomes, according to the investigators.

That body of evidence includes several recent cases series that suggest Hispanic patients with ALL have a high prevalence of methotrexate neurotoxicity.

It remains unclear why Hispanic patients would have a higher risk of methotrexate toxicity, and that must be explored in future studies, the investigators said.

The research team is currently investigating biomarkers that may help identify patients at risk of methotrexate toxicity up front. “If we can identify these at-risk patients, we can potentially employ strategies to either fully prevent or mitigate these toxicities,” Dr. Scheurer said in a statement.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Taylor OA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0939.

Hispanic pediatric patients undergoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had a risk of methotrexate toxicity that was more than twice that of non-Hispanic whites, according to results of a prospective multicenter study.

Methotrexate toxicity often led to treatment modification or delays, which may have increased relapse risk in the Hispanic patients, according to investigator Michael E. Scheurer, PhD, MPH, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his colleagues.

“We had observed that our Hispanic patients tended to experience neurotoxicity more often than other groups, but we were surprised to see the magnitude of the difference,” Dr. Scheurer said in statement.

The study, described in Clinical Cancer Research, involved 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL enrolled at one of three major U.S. pediatric cancer treatment centers. Nearly half of the patients (48.2%) were Hispanic, and approximately 86% had a diagnosis of pre B-cell leukemia.

The patients, who had a mean age of 8.4 years at diagnosis, were treated with modern ALL protocols and were followed from diagnosis to the start of maintenance/continuation therapy.

Methotrexate toxicity was seen in 39 patients at the time of the analysis. Of those patients, 29 (74.4%) were Hispanic, Dr. Scheurer and his coauthors reported.

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics had a high risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, even after the researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.43; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-5.58).

Among nine patients who experienced a second neurotoxic event, all were Hispanic.

Patients who had neurotoxicity received an average of 2.25 fewer doses of intrathecal methotrexate, and slightly lower intravenous methotrexate doses. About three-quarters of the patients experiencing methotrexate toxicity received leucovorin after intrathecal methotrexate, according to the investigators, who noted that leucovorin may interact with methotrexate and reduce efficacy.

“These findings may help us better understand what factors contribute to poorer survival among Hispanic patients with ALL,” wrote Dr. Scheurer and his coauthors.

Relapse occurred in 15.4% of patients with neurotoxicity (6 of 39 patients), and in 2.1% of patients with no neurotoxicity (13 of 241 patients).

Taken together, the findings add to the growing body of evidence that Hispanics and other minority pediatric patients with ALL experience “significant disparities” in treatment outcomes, according to the investigators.

That body of evidence includes several recent cases series that suggest Hispanic patients with ALL have a high prevalence of methotrexate neurotoxicity.

It remains unclear why Hispanic patients would have a higher risk of methotrexate toxicity, and that must be explored in future studies, the investigators said.

The research team is currently investigating biomarkers that may help identify patients at risk of methotrexate toxicity up front. “If we can identify these at-risk patients, we can potentially employ strategies to either fully prevent or mitigate these toxicities,” Dr. Scheurer said in a statement.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Taylor OA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0939.

Hispanic pediatric patients undergoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had a risk of methotrexate toxicity that was more than twice that of non-Hispanic whites, according to results of a prospective multicenter study.

Methotrexate toxicity often led to treatment modification or delays, which may have increased relapse risk in the Hispanic patients, according to investigator Michael E. Scheurer, PhD, MPH, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his colleagues.

“We had observed that our Hispanic patients tended to experience neurotoxicity more often than other groups, but we were surprised to see the magnitude of the difference,” Dr. Scheurer said in statement.

The study, described in Clinical Cancer Research, involved 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL enrolled at one of three major U.S. pediatric cancer treatment centers. Nearly half of the patients (48.2%) were Hispanic, and approximately 86% had a diagnosis of pre B-cell leukemia.

The patients, who had a mean age of 8.4 years at diagnosis, were treated with modern ALL protocols and were followed from diagnosis to the start of maintenance/continuation therapy.

Methotrexate toxicity was seen in 39 patients at the time of the analysis. Of those patients, 29 (74.4%) were Hispanic, Dr. Scheurer and his coauthors reported.

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics had a high risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, even after the researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.43; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-5.58).

Among nine patients who experienced a second neurotoxic event, all were Hispanic.

Patients who had neurotoxicity received an average of 2.25 fewer doses of intrathecal methotrexate, and slightly lower intravenous methotrexate doses. About three-quarters of the patients experiencing methotrexate toxicity received leucovorin after intrathecal methotrexate, according to the investigators, who noted that leucovorin may interact with methotrexate and reduce efficacy.

“These findings may help us better understand what factors contribute to poorer survival among Hispanic patients with ALL,” wrote Dr. Scheurer and his coauthors.

Relapse occurred in 15.4% of patients with neurotoxicity (6 of 39 patients), and in 2.1% of patients with no neurotoxicity (13 of 241 patients).

Taken together, the findings add to the growing body of evidence that Hispanics and other minority pediatric patients with ALL experience “significant disparities” in treatment outcomes, according to the investigators.

That body of evidence includes several recent cases series that suggest Hispanic patients with ALL have a high prevalence of methotrexate neurotoxicity.

It remains unclear why Hispanic patients would have a higher risk of methotrexate toxicity, and that must be explored in future studies, the investigators said.

The research team is currently investigating biomarkers that may help identify patients at risk of methotrexate toxicity up front. “If we can identify these at-risk patients, we can potentially employ strategies to either fully prevent or mitigate these toxicities,” Dr. Scheurer said in a statement.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The researchers reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Taylor OA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0939.

FROM CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors, the adjusted hazard ratio was 2.43 (95% CI, 1.06-5.58).

Study details: A prospective multicenter study of 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL, nearly half of whom were Hispanic.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The study authors reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Taylor OA et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Sep 11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0939.

Cell population appears to drive relapse in AML

Researchers believe they have identified cells that are responsible for relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

These “leukemic-regenerating cells” (LRCs), which are distinct from leukemic stem cells (LSCs), seem to arise in response to chemotherapy.

Experiments in mouse models of AML suggested that targeting LRCs could reduce the risk of relapse, and analyses of AML patient samples suggested LRCs might be used to predict relapse.

Allison Boyd, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer Cell.

The researchers evaluated the leukemic populations that persist after chemotherapy by analyzing AML patient samples and xenograft AML models. The team found that LSCs were depleted by chemotherapy, and a different cell population, LRCs, appeared to arise in response to treatment.

LRCs are “molecularly distinct from therapy-naïve LSCs,” the researchers said. In fact, the team identified 19 genes that are preferentially expressed by LRCs and could be druggable.

One of these genes is DRD2, and the researchers found they could target LRCs using a small-molecule antagonist of DRD2.

Targeting LRCs

Dr. Boyd and her colleagues compared the effects of treatment with a DRD2 antagonist in AML xenografts populated with therapy-naive LSCs and AML xenografts that harbored LRCs following exposure to cytarabine.

The researchers said DRD2 antagonist therapy “moderately” affected AML progenitors in the LSC model but “had profound effects on regenerating LRCs.”

Treatment with the DRD2 antagonist also improved the efficacy of chemotherapy.

In xenografts derived from one AML patient, treatment with cytarabine alone left 50% of mice with residual disease. However, the addition of the DRD2 antagonist enabled 100% of the mice to achieve disease-free status.

In xenografts derived from a patient with more aggressive AML, all recipient mice had residual disease after receiving cytarabine. Treatment with the DRD2 antagonist slowed leukemic re-growth and nearly doubled the time to relapse.

Targeting LRCs also reduced disease regeneration potential in samples from other AML patients.

“This is a major clinical opportunity because this type of leukemia is very diverse and responds differently across patients,” Dr. Boyd said. “It has been a challenge in a clinical setting to find a commonality for therapeutic targeting across the wide array of patients, and these regenerative cells provide that similarity.”

Predicting relapse

Dr. Boyd and her colleagues also analyzed bone marrow samples collected from AML patients approximately 3 weeks after they completed standard induction chemotherapy.

The team found that progenitor activity was enriched among residual leukemic cells. However, patient cells lacked gene expression signatures related to therapy-naive LSCs.

“Instead, these highly regenerative AML cells preferentially expressed our LRC signature,” the researchers said.

The team also found evidence to suggest that LRC molecular profiles arise temporarily after chemotherapy. The LRC signature was not observed at diagnosis or once AML was re-established at relapse.

“We think there are opportunities here because now we have a window where we can kick the cancer while it’s down,” Dr. Boyd said.

She and her colleagues also found the LRC signature might be useful for predicting relapse in AML patients.

The team assessed expression of SLC2A2, an LRC marker that has overlapping expression with DRD2, in 7 patients who were in clinical remission after induction.

The researchers found that chemotherapy increased expression of SLC2A2 only in the four patients who had residual disease—not in the three patients who remained in disease-free remission for at least 5 years.

“These results suggest that LRC populations represent reservoirs of residual disease, and LRC marker expression levels can be linked to clinical outcomes of AML relapse,” the researchers said.

This study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, and other organizations.

Researchers believe they have identified cells that are responsible for relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

These “leukemic-regenerating cells” (LRCs), which are distinct from leukemic stem cells (LSCs), seem to arise in response to chemotherapy.

Experiments in mouse models of AML suggested that targeting LRCs could reduce the risk of relapse, and analyses of AML patient samples suggested LRCs might be used to predict relapse.

Allison Boyd, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer Cell.

The researchers evaluated the leukemic populations that persist after chemotherapy by analyzing AML patient samples and xenograft AML models. The team found that LSCs were depleted by chemotherapy, and a different cell population, LRCs, appeared to arise in response to treatment.

LRCs are “molecularly distinct from therapy-naïve LSCs,” the researchers said. In fact, the team identified 19 genes that are preferentially expressed by LRCs and could be druggable.

One of these genes is DRD2, and the researchers found they could target LRCs using a small-molecule antagonist of DRD2.

Targeting LRCs

Dr. Boyd and her colleagues compared the effects of treatment with a DRD2 antagonist in AML xenografts populated with therapy-naive LSCs and AML xenografts that harbored LRCs following exposure to cytarabine.

The researchers said DRD2 antagonist therapy “moderately” affected AML progenitors in the LSC model but “had profound effects on regenerating LRCs.”

Treatment with the DRD2 antagonist also improved the efficacy of chemotherapy.

In xenografts derived from one AML patient, treatment with cytarabine alone left 50% of mice with residual disease. However, the addition of the DRD2 antagonist enabled 100% of the mice to achieve disease-free status.

In xenografts derived from a patient with more aggressive AML, all recipient mice had residual disease after receiving cytarabine. Treatment with the DRD2 antagonist slowed leukemic re-growth and nearly doubled the time to relapse.

Targeting LRCs also reduced disease regeneration potential in samples from other AML patients.

“This is a major clinical opportunity because this type of leukemia is very diverse and responds differently across patients,” Dr. Boyd said. “It has been a challenge in a clinical setting to find a commonality for therapeutic targeting across the wide array of patients, and these regenerative cells provide that similarity.”

Predicting relapse

Dr. Boyd and her colleagues also analyzed bone marrow samples collected from AML patients approximately 3 weeks after they completed standard induction chemotherapy.

The team found that progenitor activity was enriched among residual leukemic cells. However, patient cells lacked gene expression signatures related to therapy-naive LSCs.

“Instead, these highly regenerative AML cells preferentially expressed our LRC signature,” the researchers said.

The team also found evidence to suggest that LRC molecular profiles arise temporarily after chemotherapy. The LRC signature was not observed at diagnosis or once AML was re-established at relapse.

“We think there are opportunities here because now we have a window where we can kick the cancer while it’s down,” Dr. Boyd said.

She and her colleagues also found the LRC signature might be useful for predicting relapse in AML patients.

The team assessed expression of SLC2A2, an LRC marker that has overlapping expression with DRD2, in 7 patients who were in clinical remission after induction.

The researchers found that chemotherapy increased expression of SLC2A2 only in the four patients who had residual disease—not in the three patients who remained in disease-free remission for at least 5 years.

“These results suggest that LRC populations represent reservoirs of residual disease, and LRC marker expression levels can be linked to clinical outcomes of AML relapse,” the researchers said.

This study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, and other organizations.

Researchers believe they have identified cells that are responsible for relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

These “leukemic-regenerating cells” (LRCs), which are distinct from leukemic stem cells (LSCs), seem to arise in response to chemotherapy.

Experiments in mouse models of AML suggested that targeting LRCs could reduce the risk of relapse, and analyses of AML patient samples suggested LRCs might be used to predict relapse.

Allison Boyd, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer Cell.

The researchers evaluated the leukemic populations that persist after chemotherapy by analyzing AML patient samples and xenograft AML models. The team found that LSCs were depleted by chemotherapy, and a different cell population, LRCs, appeared to arise in response to treatment.

LRCs are “molecularly distinct from therapy-naïve LSCs,” the researchers said. In fact, the team identified 19 genes that are preferentially expressed by LRCs and could be druggable.

One of these genes is DRD2, and the researchers found they could target LRCs using a small-molecule antagonist of DRD2.

Targeting LRCs

Dr. Boyd and her colleagues compared the effects of treatment with a DRD2 antagonist in AML xenografts populated with therapy-naive LSCs and AML xenografts that harbored LRCs following exposure to cytarabine.

The researchers said DRD2 antagonist therapy “moderately” affected AML progenitors in the LSC model but “had profound effects on regenerating LRCs.”

Treatment with the DRD2 antagonist also improved the efficacy of chemotherapy.

In xenografts derived from one AML patient, treatment with cytarabine alone left 50% of mice with residual disease. However, the addition of the DRD2 antagonist enabled 100% of the mice to achieve disease-free status.

In xenografts derived from a patient with more aggressive AML, all recipient mice had residual disease after receiving cytarabine. Treatment with the DRD2 antagonist slowed leukemic re-growth and nearly doubled the time to relapse.

Targeting LRCs also reduced disease regeneration potential in samples from other AML patients.

“This is a major clinical opportunity because this type of leukemia is very diverse and responds differently across patients,” Dr. Boyd said. “It has been a challenge in a clinical setting to find a commonality for therapeutic targeting across the wide array of patients, and these regenerative cells provide that similarity.”

Predicting relapse

Dr. Boyd and her colleagues also analyzed bone marrow samples collected from AML patients approximately 3 weeks after they completed standard induction chemotherapy.

The team found that progenitor activity was enriched among residual leukemic cells. However, patient cells lacked gene expression signatures related to therapy-naive LSCs.

“Instead, these highly regenerative AML cells preferentially expressed our LRC signature,” the researchers said.

The team also found evidence to suggest that LRC molecular profiles arise temporarily after chemotherapy. The LRC signature was not observed at diagnosis or once AML was re-established at relapse.

“We think there are opportunities here because now we have a window where we can kick the cancer while it’s down,” Dr. Boyd said.

She and her colleagues also found the LRC signature might be useful for predicting relapse in AML patients.

The team assessed expression of SLC2A2, an LRC marker that has overlapping expression with DRD2, in 7 patients who were in clinical remission after induction.

The researchers found that chemotherapy increased expression of SLC2A2 only in the four patients who had residual disease—not in the three patients who remained in disease-free remission for at least 5 years.

“These results suggest that LRC populations represent reservoirs of residual disease, and LRC marker expression levels can be linked to clinical outcomes of AML relapse,” the researchers said.

This study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, and other organizations.

HIF1A could be therapeutic target for MDS

The transcription factor HIF1A could be a therapeutic target for “a broad spectrum” of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), according to researchers.

Preclinical experiments indicated that HIF1A fuels the biological processes that cause different types of MDS.

Researchers also found that inhibiting HIF1A reversed MDS symptoms and prolonged survival in mouse models of MDS.

Gang Huang, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cancer Discovery.

The researchers identified HIF1A’s role in MDS by first analyzing cells from healthy donors and MDS patients, including patients with refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts, and refractory anemia with excess blasts type 1 and 2.

The researchers observed increased gene expression of HIF1A-induced genes in the cells from MDS patients. The team also found a high frequency of HIF1A-expressing cells in the MDS cohort, regardless of the patients’ IPSS-R risk.

The researchers conducted experiments in mouse models to study the onset of MDS and its genetic and molecular drivers. The results suggested that dysregulation of HIF1A has a central role in the onset of MDS, including different manifestations and symptoms found in patients.

“We know the genomes of MDS patients have recurrent mutations in different transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic regulators, but the incidence of these mutations does not directly correspond to the disease when it occurs,” Dr. Huang noted.

“Our study shows that malfunctions in the signaling of HIF1A could be generating the diverse medical problems doctors see in MDS patients.”

Specifically, the researchers found that MDS-associated mutations—DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and MLL1—induced HIF1A signaling. And activation of HIF1A signaling in hematopoietic cells induced MDS phenotypes in mice.

The team said this suggests dysregulation of HIF1A signaling could generate diverse MDS phenotypes by “functioning as a signaling funnel” for MDS driver mutations.

The researchers also showed that inhibition of HIF1A could reverse MDS phenotypes. They said HIF1A deletion rescued dysplasia formation, partially rescued thrombocytopenia, and abrogated MDS development in mouse models.

Treatment with echinomycin, an inhibitor of HIF1A-mediated target gene activation, prolonged survival in mouse models of MDS and decreased MDSL cell numbers in the bone marrow and spleen.

This research was supported by the Kyoto University Foundation, the MDS Foundation, the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, the Leukemia Research Foundation, and others.

The transcription factor HIF1A could be a therapeutic target for “a broad spectrum” of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), according to researchers.

Preclinical experiments indicated that HIF1A fuels the biological processes that cause different types of MDS.

Researchers also found that inhibiting HIF1A reversed MDS symptoms and prolonged survival in mouse models of MDS.

Gang Huang, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cancer Discovery.

The researchers identified HIF1A’s role in MDS by first analyzing cells from healthy donors and MDS patients, including patients with refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts, and refractory anemia with excess blasts type 1 and 2.

The researchers observed increased gene expression of HIF1A-induced genes in the cells from MDS patients. The team also found a high frequency of HIF1A-expressing cells in the MDS cohort, regardless of the patients’ IPSS-R risk.

The researchers conducted experiments in mouse models to study the onset of MDS and its genetic and molecular drivers. The results suggested that dysregulation of HIF1A has a central role in the onset of MDS, including different manifestations and symptoms found in patients.

“We know the genomes of MDS patients have recurrent mutations in different transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic regulators, but the incidence of these mutations does not directly correspond to the disease when it occurs,” Dr. Huang noted.

“Our study shows that malfunctions in the signaling of HIF1A could be generating the diverse medical problems doctors see in MDS patients.”

Specifically, the researchers found that MDS-associated mutations—DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and MLL1—induced HIF1A signaling. And activation of HIF1A signaling in hematopoietic cells induced MDS phenotypes in mice.

The team said this suggests dysregulation of HIF1A signaling could generate diverse MDS phenotypes by “functioning as a signaling funnel” for MDS driver mutations.

The researchers also showed that inhibition of HIF1A could reverse MDS phenotypes. They said HIF1A deletion rescued dysplasia formation, partially rescued thrombocytopenia, and abrogated MDS development in mouse models.

Treatment with echinomycin, an inhibitor of HIF1A-mediated target gene activation, prolonged survival in mouse models of MDS and decreased MDSL cell numbers in the bone marrow and spleen.

This research was supported by the Kyoto University Foundation, the MDS Foundation, the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, the Leukemia Research Foundation, and others.

The transcription factor HIF1A could be a therapeutic target for “a broad spectrum” of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), according to researchers.

Preclinical experiments indicated that HIF1A fuels the biological processes that cause different types of MDS.

Researchers also found that inhibiting HIF1A reversed MDS symptoms and prolonged survival in mouse models of MDS.

Gang Huang, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cancer Discovery.

The researchers identified HIF1A’s role in MDS by first analyzing cells from healthy donors and MDS patients, including patients with refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts, and refractory anemia with excess blasts type 1 and 2.

The researchers observed increased gene expression of HIF1A-induced genes in the cells from MDS patients. The team also found a high frequency of HIF1A-expressing cells in the MDS cohort, regardless of the patients’ IPSS-R risk.

The researchers conducted experiments in mouse models to study the onset of MDS and its genetic and molecular drivers. The results suggested that dysregulation of HIF1A has a central role in the onset of MDS, including different manifestations and symptoms found in patients.

“We know the genomes of MDS patients have recurrent mutations in different transcriptional, epigenetic, and metabolic regulators, but the incidence of these mutations does not directly correspond to the disease when it occurs,” Dr. Huang noted.

“Our study shows that malfunctions in the signaling of HIF1A could be generating the diverse medical problems doctors see in MDS patients.”

Specifically, the researchers found that MDS-associated mutations—DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, RUNX1, and MLL1—induced HIF1A signaling. And activation of HIF1A signaling in hematopoietic cells induced MDS phenotypes in mice.

The team said this suggests dysregulation of HIF1A signaling could generate diverse MDS phenotypes by “functioning as a signaling funnel” for MDS driver mutations.

The researchers also showed that inhibition of HIF1A could reverse MDS phenotypes. They said HIF1A deletion rescued dysplasia formation, partially rescued thrombocytopenia, and abrogated MDS development in mouse models.

Treatment with echinomycin, an inhibitor of HIF1A-mediated target gene activation, prolonged survival in mouse models of MDS and decreased MDSL cell numbers in the bone marrow and spleen.

This research was supported by the Kyoto University Foundation, the MDS Foundation, the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, the Leukemia Research Foundation, and others.

Hemophilia B drug available in larger vial

CSL Behring has announced that Idelvion (Coagulation Factor IX [Recombinant], Albumin Fusion Protein) is now available in a 3500 IU vial size.

Idelvion is also available in 250 IU, 500 IU, 1000 IU, and 2000 IU vial sizes.

For some patients requiring high doses of Idelvion, the new 3500 IU vial size will reduce the reconstitution time needed to prepare multiple vials for a similar dose.

Idelvion is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin, and it is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat children and adults with hemophilia B.

Idelvion can be used as routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, for on-demand control and prevention of bleeding episodes, and for the perioperative management of bleeding.

Idelvion is approved for up to 14-day dosing in appropriate patients.

For more details on Idelvion, see the prescribing information.

CSL Behring has announced that Idelvion (Coagulation Factor IX [Recombinant], Albumin Fusion Protein) is now available in a 3500 IU vial size.

Idelvion is also available in 250 IU, 500 IU, 1000 IU, and 2000 IU vial sizes.

For some patients requiring high doses of Idelvion, the new 3500 IU vial size will reduce the reconstitution time needed to prepare multiple vials for a similar dose.

Idelvion is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin, and it is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat children and adults with hemophilia B.

Idelvion can be used as routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, for on-demand control and prevention of bleeding episodes, and for the perioperative management of bleeding.

Idelvion is approved for up to 14-day dosing in appropriate patients.

For more details on Idelvion, see the prescribing information.

CSL Behring has announced that Idelvion (Coagulation Factor IX [Recombinant], Albumin Fusion Protein) is now available in a 3500 IU vial size.

Idelvion is also available in 250 IU, 500 IU, 1000 IU, and 2000 IU vial sizes.

For some patients requiring high doses of Idelvion, the new 3500 IU vial size will reduce the reconstitution time needed to prepare multiple vials for a similar dose.

Idelvion is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin, and it is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat children and adults with hemophilia B.

Idelvion can be used as routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, for on-demand control and prevention of bleeding episodes, and for the perioperative management of bleeding.

Idelvion is approved for up to 14-day dosing in appropriate patients.

For more details on Idelvion, see the prescribing information.

Female to male transgender teens most likely to attempt suicide

according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Russell B. Toomey, PhD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and his associates performed an analysis of data from the Profiles of Student Life: Attitudes and Behaviors survey. Data was collected from June 2012 to May 2015 and included 120,617 adolescents aged 11-19 years. A total of 202 adolescents identified as male to female transgender, 175 identified as female to male transgender, 344 identified as nonbinary transgender, 1,052 identified as questioning, 60,973 identified as female, and 57,871 identified as male.

Male adolescents were least likely to attempt suicide, with 10% reporting at least one attempt, followed by those identifying as female (18%), questioning (28%), male to female transgender (30%), nonbinary transgender (42%), and female to male transgender (51%). All groups were significantly more likely to attempt suicide, compared with male adolescents.

Compared with transgender adolescents who identified as heterosexual only, identifying as non-heterosexual was associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide, except in nonbinary transgender adolescents. There was no association of increased risk of attempting suicide in transgender adolescents based on ethnicity, parental education levels, age, or urbanicity, except parent education level appeared to be a protective factor for questioning adolescents.

“These results should be used to inform suicide prevention and intervention policy and programs that are aimed at reducing ongoing gender identity–related disparities in suicide behavior as well as ongoing research in which authors seek to better understand for whom and why suicide behavior risk exists,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Toomey RB et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4218.

according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Russell B. Toomey, PhD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and his associates performed an analysis of data from the Profiles of Student Life: Attitudes and Behaviors survey. Data was collected from June 2012 to May 2015 and included 120,617 adolescents aged 11-19 years. A total of 202 adolescents identified as male to female transgender, 175 identified as female to male transgender, 344 identified as nonbinary transgender, 1,052 identified as questioning, 60,973 identified as female, and 57,871 identified as male.

Male adolescents were least likely to attempt suicide, with 10% reporting at least one attempt, followed by those identifying as female (18%), questioning (28%), male to female transgender (30%), nonbinary transgender (42%), and female to male transgender (51%). All groups were significantly more likely to attempt suicide, compared with male adolescents.

Compared with transgender adolescents who identified as heterosexual only, identifying as non-heterosexual was associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide, except in nonbinary transgender adolescents. There was no association of increased risk of attempting suicide in transgender adolescents based on ethnicity, parental education levels, age, or urbanicity, except parent education level appeared to be a protective factor for questioning adolescents.

“These results should be used to inform suicide prevention and intervention policy and programs that are aimed at reducing ongoing gender identity–related disparities in suicide behavior as well as ongoing research in which authors seek to better understand for whom and why suicide behavior risk exists,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Toomey RB et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4218.

according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Russell B. Toomey, PhD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and his associates performed an analysis of data from the Profiles of Student Life: Attitudes and Behaviors survey. Data was collected from June 2012 to May 2015 and included 120,617 adolescents aged 11-19 years. A total of 202 adolescents identified as male to female transgender, 175 identified as female to male transgender, 344 identified as nonbinary transgender, 1,052 identified as questioning, 60,973 identified as female, and 57,871 identified as male.

Male adolescents were least likely to attempt suicide, with 10% reporting at least one attempt, followed by those identifying as female (18%), questioning (28%), male to female transgender (30%), nonbinary transgender (42%), and female to male transgender (51%). All groups were significantly more likely to attempt suicide, compared with male adolescents.

Compared with transgender adolescents who identified as heterosexual only, identifying as non-heterosexual was associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide, except in nonbinary transgender adolescents. There was no association of increased risk of attempting suicide in transgender adolescents based on ethnicity, parental education levels, age, or urbanicity, except parent education level appeared to be a protective factor for questioning adolescents.

“These results should be used to inform suicide prevention and intervention policy and programs that are aimed at reducing ongoing gender identity–related disparities in suicide behavior as well as ongoing research in which authors seek to better understand for whom and why suicide behavior risk exists,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Toomey RB et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4218.

FROM PEDIATRICS

How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The 2018 meeting of the American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 6 to 8, featured a talk by Louis J. Muglia, MD, PhD, on “Evolution, Genetics, and Preterm Birth.” Dr. Muglia, who is Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, Director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth, and Director of the Division of Human Genetics at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, discussed his recent research on genetic associations of gestational duration and spontaneous preterm birth and some of his key findings. OBG

OBG Management : You discussed the “genetic architecture of human pregnancy.” Can you define what that is?

The genetic architecture tells us which pathways are activated that initiate birth to occur. By understanding that, we can begin to understand not only the genetic factors that the architecture describes, but also that the genetic architecture is going to be modified in response to environmental stimuli that will disrupt the outcomes. In the future, we will be able to develop biomarkers, predictive genetic algorithms, and other tools that will allow us to assess risk in a way that we can’t right now.

OBG Management : How is gene study adding to the overall knowledge of preterm birth?

Gene study is giving us new pathways to look at. It will give us biomarkers; it will give us targets for potential therapeutic interventions. I mentioned in my talk that one of the genes that we identified in our recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study pinpointed selenium as an important component and a whole process of determining risk for preterm birth that we never even thought of before. For instance, could there be preventive strategies for prematurity, like we have for neural tube defects and folic acid? The possibility of supplementation with selenium, or other micronutrients that some of the genetic studies will reveal to us in a nonbiased fashion, would not be discovered without the study of genes.

OBG Management : You mentioned your NEJM paper. Can you describe the large data sets that your team used in your gene research?

The discovery cohort, which refers to essentially the biggest compilation, was a wonderful collaboration that we had with the direct-to-consumer genotyping company 23andme. I had contacted them to determine if they had captured any pregnancy-related data, particularly birth-timing information related to individuals who had completed their research surveys. They indicated that they had asked the question, “What was the length of your first pregnancy?” With this information, we were able to get essentially 44,000 responses to that question. That really provided the foundation for the study in the NEJM.

Now, there are caveats with that information, since it was all recollection and self-reported data. We were unsure how accurate it would be. In addition, we did not always know why the delivery occurred—was it spontaneous or was it medically indicated? We were interested in the spontaneous, naturally-occurring preterm birth. Using that as a discovery cohort, with those reservations in mind, we identified 6 genes for birth length. We then asked in a carefully collected series of cohorts that we had amassed on our own, and with collaborators over the years from Finland, Norway, and Denmark, whether those same associations still existed. And every one of them did. Every one of them was validated in our carefully phenotyped cohort. In total, that was about 55,000 women that we had analyzed and studied between the discovery and the validation cohort. Since then, we have accessed another 3 or 4 cohorts, which has increased our sample size even more, so we have identified even more genes than we originally reported in our paper.

OBG Management : What do you identify as the next steps in your research after identifying several genes associated with the timing of birth?

The idea is not just to develop longer and longer lists of genes that are suggested or associated with birth timing phenotypes that we are interested in—either preterm birth or duration of gestation—but to actually understand what they are doing. That is a little bit trickier than saying we have identified genes. We have identified the precise region of mom’s genome that is involved in regulating birth timing, but in many cases I have indicated the closest gene that is involved in birth timing. For some of the regions, however, there are many genes involved, and so is it regulating one pathway, is it regulating many? Which tissue is involved in regulating? Is it in the uterus, in the cervix, or in the immune system? The next steps are to figure out how these things are acting so that we can design better strategies for prevention. The goal is to really bring down preterm birth rates by implementing strategies for prevention and treatment that we don’t currently have.

OBG Management : What is the significance of maternal selenium status and preterm birth risk?

Well, we really don’t know. We identified one of these gene regions, a variant near a factory involved in production of what are called selenoproteins—proteins that incorporate selenium into them. (There are about 25 of those in the human genome.) We identified a genetic risk factor in a region that is linked to the selenoprotein production chain. What we were brought to think about was this: In parts of the world where we know there is substantial selenium deficiency (parts of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of China, parts of Asia), could selenium deficiency itself be contributing to very high rates of preterm birth? Right now we are trying to figure out if there is an association by measuring maternal plasma selenium levels about halfway through pregnancy and then asking what was the outcome from the pregnancy. Are women with low levels of selenium at increased risk for preterm birth? There have been 2 studies published that do already suggest that women with lower selenium levels tend to give birth to premature babies often.

OBG Management : What is the HSPA1L pathway and why is it important for pregnancy outcomes?

In our study where we performed genome-wide association, we looked at what are called common variants in the human genome—common variants in general are carried by more people. They had to be carried by a couple percent of the population to be included in our study. But there is also the thought that individual, more severe variants (that do not necessarily get transmitted because of how severe their effects are), will also affect birth outcomes. So we did a study to sequence mom’s genome to look for these rarities, things that account for less than 1% of the whole population. We were able to identify this gene, HSPA1L, which again, as found in our genome-wide studies, seems to be involved in controlling the strength of the steroid hormone signal, which is very important for maintaining and ending pregnancy. Progesterone and estrogen are the yin and yang of maintaining and ending pregnancy, and we think HSPA1L, the variant we identified, decreases the steroid hormone signal function so that it is not able to regulate that progesterone/estrogen signal the same way anymore.

OBG Management : Why is this an exciting time to be studying genes in pregnancy?

To understand how gene study can optimize our knowledge of human pregnancy outcomes really requires a study of human pregnancy specifically, and one of the best opportunities we have is to gather these large data sets. And we can’t forget about collecting pregnancy outcomes on women as part of new National Institutes of Health initiatives that are developing personalized medicine strategies. We looked at 50,000 women in our research, but we have the capacity to look at 500,000 women. As we go from identifying 6 genes to 12 genes to 100 genes, we will be able to understand better how these things are talking to one another and better define the signatures of what tissues are being acted on. We will be able to get sequentially synergistic information that will allow us to solve this in a way we couldn’t before.

The opioid crisis: Treating pregnant women with addiction

Subcutaneous Ulnar Nerve Transposition Using Osborne’s Ligament as a Ligamentodermal or Ligamentofascial Sling

ABSTRACT

The ulnar nerve is most commonly compressed at the elbow in the cubital tunnel. Conservative and operative treatments have been applied for cubital tunnel syndrome. Surgical management options include decompression, medial epicondylectomy, and various anterior transposition techniques. We describe a novel technique of anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve by using Osborne’s ligament as a sling to avoid subluxation. Osborne’s ligament is incised posteriorly and medially on the olecranon to create a sling with 2 to 3 cm width. The sling is tailored to wrap around the ulnar nerve and attached to the flexor-pronator fascia or dermis to create a smooth gliding surface without causing compression. Ten patients with cubital tunnel syndrome, established by physical examination findings and electromyography/nerve conduction studies underwent ulnar nerve transposition using this technique and were able to participate in a phone survey. The average follow-up was 15.6 months (range, 4-28 months). The average time to become subjectively “better” after surgery was 4.2 weeks. The pain intensity was reduced from an average of 7.5 preoperatively to <1, on a 10-point scale, at the time of the survey. All patients had symptomatic relief without any complication. The proposed technique using Osborne’s ligament as a ligamentofascial or ligamentodermal sling offers a unique way of creating a non-compressive sling with the component of the cubital tunnel itself and has an additional benefit of creating a smooth gliding surface for early return of function.

Continue to: Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow...

Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow is a common nerve compression syndrome in the upper extremity. There are multiple sites of compression of the ulnar nerve distal to the axilla. The most common site of ulnar nerve compression is at the cubital tunnel.1 When ulnar nerve compression is clinically suspected, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity studies (NCS) may be performed to help support the diagnosis. However, a false negative rate in excess of 10% is found in patients with clinical signs and symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome.2 Treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome involves nonsurgical treatments, including activity modification, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, splinting, and physical therapy or surgical treatment.3-5

Surgical management of cubital tunnel syndrome is indicated after a failed nonsurgical management or a presentation with motor weakness. The most common surgical treatments include in situ decompression, subcutaneous transposition, intramuscular transposition, submuscular transposition, and medial epicondylectomy, or their combination.6 However, optimal surgical management of cubital tunnel syndrome remains controversial.2,7 The overall goal of surgery is to eliminate all sites of compression and obtain a tension-free nerve that glides smoothly.

After the initial concept of subcutaneous anterior ulnar nerve transposition was developed by Curtis8 in 1898, many different techniques have been derived including epineurial suture, fasciodermal sling, and subcutaneous to fascia suture.8-10 Common complications of subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition include nerve fibrosis, recurrent subluxation, and inadequate division of the intermuscular septum.9 Additionally, thin patients often have repeated trauma to their ulnar nerves after subcutaneous transposition.3

The anatomy of the cubital tunnel is well described, but it has multiple names and descriptions throughout the literature. Osborne11 originally described a transverse fibrous band as the fascial connection between the 2 heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris that forms the roof of the cubital tunnel. O’Driscoll and colleagues5 conducted a cadaver study and proposed calling Osborne’s band as the cubital tunnel retinaculum. They described 4 different variations of anatomy and the retinaculum as a 4-mm wide band of tissue located proximally in the cubital tunnel that is distinct from the arcuate ligament and the fascia between the 2 heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.5 Green and Rayan12 studied cubital tunnel anatomy and referred to the ligament that spans the medial epicondyle and the olecranon as the arcuate ligament, which is also distinct from the flexor carpi ulnaris aponeurosis. These variations in named anatomy make describing procedures around the cubital tunnel challenging. In this study, the fascial band between the 2 heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, as originally described by Osborne,11 will be referred to as Osborne’s ligament.

We describe a novel technique of anterior subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition, where Osborne’s ligament is used as a sling to prevent ulnar nerve subluxation over the medial epicondyle. We also describe the results of our initial subset of patients who were treated with this technique.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a chart review of all patients operated on between January 2010 and March 2012 by the same surgeon. We recruited 15 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with ulnar nerve transposition for moderate to severe cubital tunnel syndrome through EMG/NCS and physical examination during this time frame. Operative reports were then reviewed. In 14 of these 15 cases, Osborne’s ligament was used as a ligamentofascial or ligamentodermal sling. In the fifteenth patient, preoperative subluxation of the ulnar nerve was identified with movement of elbow, and Osborne’s ligament was found to not be large enough to provide an appropriate sling. Three patients were unreachable, and 1 patient chose to not participate in the study. Of the initial 15 patients, 10 were given a telephone survey (Appendix A), which was prepared based on the recommendation of Novak and colleagues13 and incorporated with questions regarding preoperative symptoms, satisfaction, smoking history, and employment status. This study was Institutional Review Board approved at our institution, and appropriate consent was obtained from the participants.

Appendix A. Ulnar Nerve Telephone Survey

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

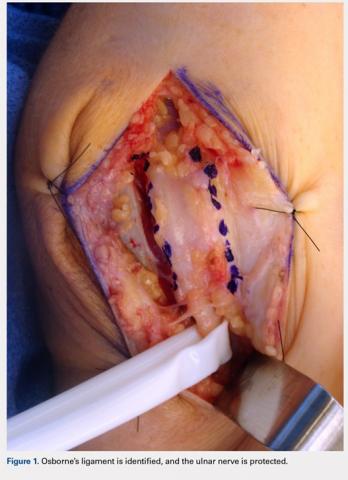

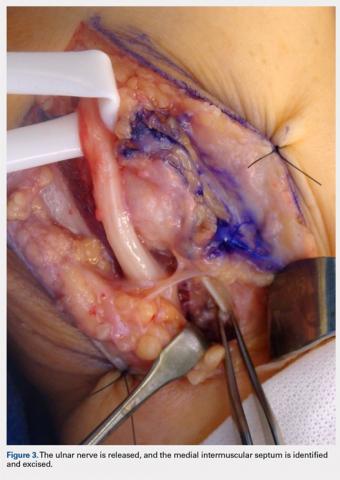

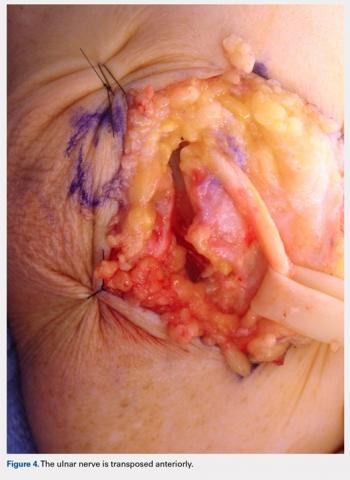

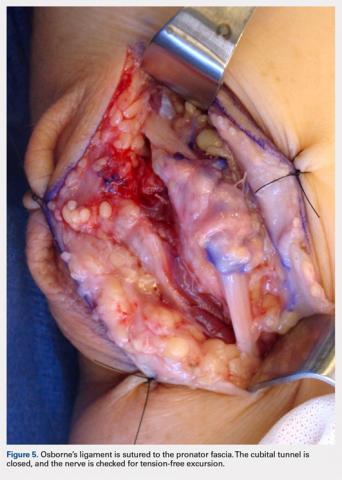

A 10 to 12 cm incision centered over the cubital tunnel is made. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is identified and protected. After dissection through superficial fascia, Osborne’s ligament is identified. The ligament is then released posteriorly from the olecranon and is assessed. The ulnar nerve is then freed in a proximal to distal manner to preserve vascular structures that supply the epineurium. The medial intermuscular septum is examined and excised as a site of compression. The ulnar nerve is then mobilized. Once mobilized, the ulnar nerve is transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle and checked to ensure that no sharp curves are made and nothing is impinging on the nerve while passively flexing and extending the elbow. The Osborne’s ligament is then passed over the top of the previously transposed ulnar nerve to create a sling that is ligamentofascial if sutured to the flexor/pronator fascia or ligamentodermal if sutured to dermis. Importantly, the flexor/pronator fascia is not incised. The remaining soft tissue and fascia of the cubital tunnel are then closed with 2-0 vicryl suture. The free end of the Osborne’s ligament is sutured to flexor/pronator fascia or to dermis, anterior to the medial epicondyle with No. 0 vicryl suture. This process is conducted in a tension-free manner to prevent creating a new site of compression. The nerve is then rechecked for appropriate, tension-free gliding followed by closure of the wound in layers after irrigation (additional details are shown in Figures 1-5).

RESULTS

Ten of the 15 patients were available for telephone review. The results of the telephone survey are as follows. The average time to telephone survey was 15.6 months (range, 4-28 months). The average time to become subjectively “better” was 4.2 weeks (range, 2-6 weeks). The average time back to work was 1.6 weeks (range, 1 day to 3 weeks). Three patients were retired and did not go back to work. All patients stated they were subjectively “better” after surgery, and when asked, all patients stated that they would choose surgery again. The average pain prior to surgery was 7.5 (range, 5.5-9.5) on a 10-point scale. The average pain after surgery at final phone interview was 0.1 on a 10-point scale (range, 0-1). All patients stated that their sensation was subjectively better after the surgery. One patient said that his strength worsened, another patient said that his strength was the same, and the remaining patients said that their strength was better. One patient was a smoker, and no patients had acute traumatic injuries that caused their ulnar nerve symptoms.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION