User login

Hormonal contraceptives tied to leukemia in progeny

A nationwide cohort study suggests an association between a woman’s use of hormonal contraceptives and leukemia in her offspring.

Children of mothers who used hormonal contraception, either during pregnancy or in the 3 months beforehand, had a 1.5-fold greater risk of leukemia, when compared to children of mothers who had never used hormonal contraception.

This increased risk translated to one additional case of leukemia per about 50,000 children exposed to hormonal contraceptives.

The increased risk appeared limited to non-lymphoid leukemia.

Marie Hargreave, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center in Copenhagen, Denmark, and her colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Oncology.

The study included 1,185,157 children born between 1996 and 2014 and followed for a median of 9.3 years. Data on these children were collected from the Danish Medical Birth Registry and the Danish Cancer Registry.

The researchers looked at redeemed prescriptions from the Danish National Prescription Registry to determine the mothers’ contraceptive use and divided the women into three categories:

- Mothers who had never used hormonal contraceptives

- Those with previous hormonal contraceptive use, defined as greater than 3 months before the start of pregnancy

- Mothers with recent contraceptive use, defined as during or within 3 months of pregnancy.

Results

There were 606 children diagnosed with leukemia in the study cohort—465 with lymphoid leukemia and 141 with non-lymphoid leukemia.

Overall, children born to mothers with previous or recent use of hormonal contraceptives had a significantly increased risk of developing any leukemia. The hazard ratios (HRs) were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.25 (P=0.039)

- Recent use—HR=1.46 (P=0.011)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.42 (P=0.025)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=1.78 (P=0.070).

The risk of lymphoid leukemia did not increase significantly with maternal use of hormonal contraceptives. The HRs were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.23 (P=0.089)

- Recent use—HR=1.27 (P=0.167)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.28 (P=0.173)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=1.22 (P=0.635).

However, the risk of non-lymphoid leukemia was significantly increased in children born to mothers with recent hormonal contraceptive use. The HRs were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.33 (P=0.232)

- Recent use—HR=2.17 (P=0.008)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.95 (P=0.033)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=3.87 (P=0.006).

The association between recent contraceptive use and any leukemia was strongest in children ages 6 to 10 years. The researchers said this was not surprising because the incidence of non-lymphoid leukemia increases after the age of 6.

The researchers estimated that a mother’s recent use of hormonal contraceptives would have resulted in about one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children; in other words, 25 additional cases of leukemia over the study period.

This low risk of leukemia “is not a major concern with regard to the safety of hormonal contraceptives,” the researchers said.

However, the findings do suggest the intrauterine hormonal environment affects leukemia development in children, and this should be explored in future research.

This study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations, and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

A nationwide cohort study suggests an association between a woman’s use of hormonal contraceptives and leukemia in her offspring.

Children of mothers who used hormonal contraception, either during pregnancy or in the 3 months beforehand, had a 1.5-fold greater risk of leukemia, when compared to children of mothers who had never used hormonal contraception.

This increased risk translated to one additional case of leukemia per about 50,000 children exposed to hormonal contraceptives.

The increased risk appeared limited to non-lymphoid leukemia.

Marie Hargreave, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center in Copenhagen, Denmark, and her colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Oncology.

The study included 1,185,157 children born between 1996 and 2014 and followed for a median of 9.3 years. Data on these children were collected from the Danish Medical Birth Registry and the Danish Cancer Registry.

The researchers looked at redeemed prescriptions from the Danish National Prescription Registry to determine the mothers’ contraceptive use and divided the women into three categories:

- Mothers who had never used hormonal contraceptives

- Those with previous hormonal contraceptive use, defined as greater than 3 months before the start of pregnancy

- Mothers with recent contraceptive use, defined as during or within 3 months of pregnancy.

Results

There were 606 children diagnosed with leukemia in the study cohort—465 with lymphoid leukemia and 141 with non-lymphoid leukemia.

Overall, children born to mothers with previous or recent use of hormonal contraceptives had a significantly increased risk of developing any leukemia. The hazard ratios (HRs) were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.25 (P=0.039)

- Recent use—HR=1.46 (P=0.011)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.42 (P=0.025)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=1.78 (P=0.070).

The risk of lymphoid leukemia did not increase significantly with maternal use of hormonal contraceptives. The HRs were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.23 (P=0.089)

- Recent use—HR=1.27 (P=0.167)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.28 (P=0.173)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=1.22 (P=0.635).

However, the risk of non-lymphoid leukemia was significantly increased in children born to mothers with recent hormonal contraceptive use. The HRs were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.33 (P=0.232)

- Recent use—HR=2.17 (P=0.008)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.95 (P=0.033)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=3.87 (P=0.006).

The association between recent contraceptive use and any leukemia was strongest in children ages 6 to 10 years. The researchers said this was not surprising because the incidence of non-lymphoid leukemia increases after the age of 6.

The researchers estimated that a mother’s recent use of hormonal contraceptives would have resulted in about one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children; in other words, 25 additional cases of leukemia over the study period.

This low risk of leukemia “is not a major concern with regard to the safety of hormonal contraceptives,” the researchers said.

However, the findings do suggest the intrauterine hormonal environment affects leukemia development in children, and this should be explored in future research.

This study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations, and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

A nationwide cohort study suggests an association between a woman’s use of hormonal contraceptives and leukemia in her offspring.

Children of mothers who used hormonal contraception, either during pregnancy or in the 3 months beforehand, had a 1.5-fold greater risk of leukemia, when compared to children of mothers who had never used hormonal contraception.

This increased risk translated to one additional case of leukemia per about 50,000 children exposed to hormonal contraceptives.

The increased risk appeared limited to non-lymphoid leukemia.

Marie Hargreave, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center in Copenhagen, Denmark, and her colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Oncology.

The study included 1,185,157 children born between 1996 and 2014 and followed for a median of 9.3 years. Data on these children were collected from the Danish Medical Birth Registry and the Danish Cancer Registry.

The researchers looked at redeemed prescriptions from the Danish National Prescription Registry to determine the mothers’ contraceptive use and divided the women into three categories:

- Mothers who had never used hormonal contraceptives

- Those with previous hormonal contraceptive use, defined as greater than 3 months before the start of pregnancy

- Mothers with recent contraceptive use, defined as during or within 3 months of pregnancy.

Results

There were 606 children diagnosed with leukemia in the study cohort—465 with lymphoid leukemia and 141 with non-lymphoid leukemia.

Overall, children born to mothers with previous or recent use of hormonal contraceptives had a significantly increased risk of developing any leukemia. The hazard ratios (HRs) were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.25 (P=0.039)

- Recent use—HR=1.46 (P=0.011)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.42 (P=0.025)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=1.78 (P=0.070).

The risk of lymphoid leukemia did not increase significantly with maternal use of hormonal contraceptives. The HRs were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.23 (P=0.089)

- Recent use—HR=1.27 (P=0.167)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.28 (P=0.173)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=1.22 (P=0.635).

However, the risk of non-lymphoid leukemia was significantly increased in children born to mothers with recent hormonal contraceptive use. The HRs were as follows:

- Previous use of hormonal contraceptives—HR=1.33 (P=0.232)

- Recent use—HR=2.17 (P=0.008)

- Use within 3 months of pregnancy—HR=1.95 (P=0.033)

- Use during pregnancy—HR=3.87 (P=0.006).

The association between recent contraceptive use and any leukemia was strongest in children ages 6 to 10 years. The researchers said this was not surprising because the incidence of non-lymphoid leukemia increases after the age of 6.

The researchers estimated that a mother’s recent use of hormonal contraceptives would have resulted in about one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children; in other words, 25 additional cases of leukemia over the study period.

This low risk of leukemia “is not a major concern with regard to the safety of hormonal contraceptives,” the researchers said.

However, the findings do suggest the intrauterine hormonal environment affects leukemia development in children, and this should be explored in future research.

This study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations, and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Neurotoxicity risk is higher for Hispanic kids with ALL

In a prospective study, Hispanic pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had a risk of methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity that was more than twice the risk observed in non-Hispanic white patients.

However, there was no significant difference in methotrexate neurotoxicity between non-Hispanic black patients and non-Hispanic white patients.

There were no cases of neurotoxicity among patients of other races/ethnicities.

Michael E. Scheurer, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and his colleagues conducted this study and detailed the results in Clinical Cancer Research.

The study included 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL. Most patients (85.7%) had B-ALL, 10.7% had T-ALL, and 3.6% had lymphoblastic lymphoma.

Nearly half of the patients (48.2%) were Hispanic, 36.2% were non-Hispanic white, 8.3% were non-Hispanic black, and 7.3% were non-Hispanic “other.”

The patients, who had a mean age of 8.4 years at diagnosis, were treated with modern ALL protocols and were followed from diagnosis to the start of maintenance/continuation therapy.

Methotrexate neurotoxicity was seen in 39 patients at the time of the analysis. Of those patients, 29 (74.4%) were Hispanic.

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics had a high risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, even after the researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 2.43 (P=0.036).

“We had observed that our Hispanic patients tended to experience neurotoxicity more often than other groups, but we were surprised to see the magnitude of the difference,” Dr. Scheurer said.

There was no significant difference in methotrexate neurotoxicity between non-Hispanic black patients and non-Hispanic white patients. The adjusted HR for non-Hispanic black patients was 1.23 (P=0.80).

Patients in the “other” racial/ethnic group did not experience any neurotoxic events.

All nine patients who experienced a second neurotoxic event were Hispanic.

Patients who had neurotoxicity received an average of 2.25 fewer doses of intrathecal methotrexate (P<0.01) and 1.81 fewer doses of intravenous methotrexate (P=0.084) than patients without neurotoxicity.

About three-quarters (74.4%) of patients experiencing methotrexate neurotoxicity received leucovorin rescue, according to the investigators, who noted that leucovorin may interact with methotrexate and reduce its efficacy.

Relapse occurred in 15.4% (6/39) of patients with neurotoxicity and 2.1% (13/241) of patients with no neurotoxicity (P=0.0038).

The investigators said these findings add to the growing body of evidence that Hispanics and other minority pediatric patients with ALL experience “significant disparities” in treatment outcomes.

It remains unclear why Hispanic patients would have a higher risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, and that must be explored in future studies, the investigators said.

The team is currently investigating whether biomarkers could be used to identify patients at risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity.

“Biomarkers may someday allow us to identify patients upfront, before even beginning therapy, who might be at risk for such outcomes,” Dr. Scheurer said. “If we can identify these at-risk patients, we can potentially employ strategies to either fully prevent or mitigate these toxicities.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The researchers said they had no potential conflicts of interest.

In a prospective study, Hispanic pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had a risk of methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity that was more than twice the risk observed in non-Hispanic white patients.

However, there was no significant difference in methotrexate neurotoxicity between non-Hispanic black patients and non-Hispanic white patients.

There were no cases of neurotoxicity among patients of other races/ethnicities.

Michael E. Scheurer, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and his colleagues conducted this study and detailed the results in Clinical Cancer Research.

The study included 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL. Most patients (85.7%) had B-ALL, 10.7% had T-ALL, and 3.6% had lymphoblastic lymphoma.

Nearly half of the patients (48.2%) were Hispanic, 36.2% were non-Hispanic white, 8.3% were non-Hispanic black, and 7.3% were non-Hispanic “other.”

The patients, who had a mean age of 8.4 years at diagnosis, were treated with modern ALL protocols and were followed from diagnosis to the start of maintenance/continuation therapy.

Methotrexate neurotoxicity was seen in 39 patients at the time of the analysis. Of those patients, 29 (74.4%) were Hispanic.

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics had a high risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, even after the researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 2.43 (P=0.036).

“We had observed that our Hispanic patients tended to experience neurotoxicity more often than other groups, but we were surprised to see the magnitude of the difference,” Dr. Scheurer said.

There was no significant difference in methotrexate neurotoxicity between non-Hispanic black patients and non-Hispanic white patients. The adjusted HR for non-Hispanic black patients was 1.23 (P=0.80).

Patients in the “other” racial/ethnic group did not experience any neurotoxic events.

All nine patients who experienced a second neurotoxic event were Hispanic.

Patients who had neurotoxicity received an average of 2.25 fewer doses of intrathecal methotrexate (P<0.01) and 1.81 fewer doses of intravenous methotrexate (P=0.084) than patients without neurotoxicity.

About three-quarters (74.4%) of patients experiencing methotrexate neurotoxicity received leucovorin rescue, according to the investigators, who noted that leucovorin may interact with methotrexate and reduce its efficacy.

Relapse occurred in 15.4% (6/39) of patients with neurotoxicity and 2.1% (13/241) of patients with no neurotoxicity (P=0.0038).

The investigators said these findings add to the growing body of evidence that Hispanics and other minority pediatric patients with ALL experience “significant disparities” in treatment outcomes.

It remains unclear why Hispanic patients would have a higher risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, and that must be explored in future studies, the investigators said.

The team is currently investigating whether biomarkers could be used to identify patients at risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity.

“Biomarkers may someday allow us to identify patients upfront, before even beginning therapy, who might be at risk for such outcomes,” Dr. Scheurer said. “If we can identify these at-risk patients, we can potentially employ strategies to either fully prevent or mitigate these toxicities.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The researchers said they had no potential conflicts of interest.

In a prospective study, Hispanic pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had a risk of methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity that was more than twice the risk observed in non-Hispanic white patients.

However, there was no significant difference in methotrexate neurotoxicity between non-Hispanic black patients and non-Hispanic white patients.

There were no cases of neurotoxicity among patients of other races/ethnicities.

Michael E. Scheurer, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and his colleagues conducted this study and detailed the results in Clinical Cancer Research.

The study included 280 patients with newly diagnosed ALL. Most patients (85.7%) had B-ALL, 10.7% had T-ALL, and 3.6% had lymphoblastic lymphoma.

Nearly half of the patients (48.2%) were Hispanic, 36.2% were non-Hispanic white, 8.3% were non-Hispanic black, and 7.3% were non-Hispanic “other.”

The patients, who had a mean age of 8.4 years at diagnosis, were treated with modern ALL protocols and were followed from diagnosis to the start of maintenance/continuation therapy.

Methotrexate neurotoxicity was seen in 39 patients at the time of the analysis. Of those patients, 29 (74.4%) were Hispanic.

Compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics had a high risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, even after the researchers accounted for age, sex, ALL risk stratification, and other factors. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 2.43 (P=0.036).

“We had observed that our Hispanic patients tended to experience neurotoxicity more often than other groups, but we were surprised to see the magnitude of the difference,” Dr. Scheurer said.

There was no significant difference in methotrexate neurotoxicity between non-Hispanic black patients and non-Hispanic white patients. The adjusted HR for non-Hispanic black patients was 1.23 (P=0.80).

Patients in the “other” racial/ethnic group did not experience any neurotoxic events.

All nine patients who experienced a second neurotoxic event were Hispanic.

Patients who had neurotoxicity received an average of 2.25 fewer doses of intrathecal methotrexate (P<0.01) and 1.81 fewer doses of intravenous methotrexate (P=0.084) than patients without neurotoxicity.

About three-quarters (74.4%) of patients experiencing methotrexate neurotoxicity received leucovorin rescue, according to the investigators, who noted that leucovorin may interact with methotrexate and reduce its efficacy.

Relapse occurred in 15.4% (6/39) of patients with neurotoxicity and 2.1% (13/241) of patients with no neurotoxicity (P=0.0038).

The investigators said these findings add to the growing body of evidence that Hispanics and other minority pediatric patients with ALL experience “significant disparities” in treatment outcomes.

It remains unclear why Hispanic patients would have a higher risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity, and that must be explored in future studies, the investigators said.

The team is currently investigating whether biomarkers could be used to identify patients at risk of methotrexate neurotoxicity.

“Biomarkers may someday allow us to identify patients upfront, before even beginning therapy, who might be at risk for such outcomes,” Dr. Scheurer said. “If we can identify these at-risk patients, we can potentially employ strategies to either fully prevent or mitigate these toxicities.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium, a St. Baldrick’s Foundation Consortium Research Grant. The researchers said they had no potential conflicts of interest.

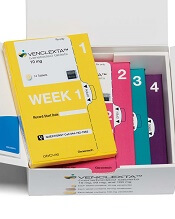

MRD data added to venetoclax label

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the label for venetoclax tablets (Venclexta®) to include data on minimal residual disease (MRD).

The drug’s prescribing information now includes details on MRD negativity in previously treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received venetoclax in combination with rituximab in the phase 3 MURANO trial.

The combination of venetoclax and rituximab was FDA approved in June for the treatment of patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma, with or without 17p deletion, who received at least one prior therapy.

The MURANO trial (NCT02005471), which supported the FDA approval, included 389 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.

The patients were randomized to receive:

- Venetoclax at 400 mg daily for 24 months (after a 5-week ramp-up period) plus rituximab at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 for the first cycle and at 500 mg/m2 on day 1 for cycles 2 to 6 (n=194)

- Bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 for 6 cycles plus rituximab at the same schedule as the venetoclax arm (n=195).

Researchers evaluated MRD in patients who achieved a partial response or better. MRD was assessed using allele-specific oligonucleotide polymerase chain reaction, and the definition of MRD negativity was less than one CLL cell per 10,000 lymphocytes.

The researchers assessed MRD in the peripheral blood 3 months after the last dose of rituximab. At that time, 53% (103/194) of patients in the venetoclax-rituximab arm were MRD negative, as were 12% (23/195) of patients in the bendamustine-rituximab arm.

The researchers also assessed MRD in the peripheral blood of patients with a complete response (CR) or CR with incomplete marrow recovery (CRi). MRD negativity was achieved by 3% (6/194) of these patients in the venetoclax-rituximab arm and 2% (3/195) in the bendamustine-rituximab arm.

Three percent (3/106) of patients in the venetoclax arm who achieved CR/CRi were MRD negative in both the peripheral blood and the bone marrow.

“The rates of MRD negativity seen with Venclexta plus rituximab are very encouraging,” said MURANO investigator John Seymour, MBBS, PhD, of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Additional results from the MURANO trial were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March and are included in the prescribing information for venetoclax.

Venetoclax is being developed by AbbVie and Roche. It is jointly commercialized by AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, in the U.S. and by AbbVie outside the U.S.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the label for venetoclax tablets (Venclexta®) to include data on minimal residual disease (MRD).

The drug’s prescribing information now includes details on MRD negativity in previously treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received venetoclax in combination with rituximab in the phase 3 MURANO trial.

The combination of venetoclax and rituximab was FDA approved in June for the treatment of patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma, with or without 17p deletion, who received at least one prior therapy.

The MURANO trial (NCT02005471), which supported the FDA approval, included 389 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.

The patients were randomized to receive:

- Venetoclax at 400 mg daily for 24 months (after a 5-week ramp-up period) plus rituximab at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 for the first cycle and at 500 mg/m2 on day 1 for cycles 2 to 6 (n=194)

- Bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 for 6 cycles plus rituximab at the same schedule as the venetoclax arm (n=195).

Researchers evaluated MRD in patients who achieved a partial response or better. MRD was assessed using allele-specific oligonucleotide polymerase chain reaction, and the definition of MRD negativity was less than one CLL cell per 10,000 lymphocytes.

The researchers assessed MRD in the peripheral blood 3 months after the last dose of rituximab. At that time, 53% (103/194) of patients in the venetoclax-rituximab arm were MRD negative, as were 12% (23/195) of patients in the bendamustine-rituximab arm.

The researchers also assessed MRD in the peripheral blood of patients with a complete response (CR) or CR with incomplete marrow recovery (CRi). MRD negativity was achieved by 3% (6/194) of these patients in the venetoclax-rituximab arm and 2% (3/195) in the bendamustine-rituximab arm.

Three percent (3/106) of patients in the venetoclax arm who achieved CR/CRi were MRD negative in both the peripheral blood and the bone marrow.

“The rates of MRD negativity seen with Venclexta plus rituximab are very encouraging,” said MURANO investigator John Seymour, MBBS, PhD, of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Additional results from the MURANO trial were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March and are included in the prescribing information for venetoclax.

Venetoclax is being developed by AbbVie and Roche. It is jointly commercialized by AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, in the U.S. and by AbbVie outside the U.S.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the label for venetoclax tablets (Venclexta®) to include data on minimal residual disease (MRD).

The drug’s prescribing information now includes details on MRD negativity in previously treated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received venetoclax in combination with rituximab in the phase 3 MURANO trial.

The combination of venetoclax and rituximab was FDA approved in June for the treatment of patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma, with or without 17p deletion, who received at least one prior therapy.

The MURANO trial (NCT02005471), which supported the FDA approval, included 389 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.

The patients were randomized to receive:

- Venetoclax at 400 mg daily for 24 months (after a 5-week ramp-up period) plus rituximab at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 for the first cycle and at 500 mg/m2 on day 1 for cycles 2 to 6 (n=194)

- Bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 for 6 cycles plus rituximab at the same schedule as the venetoclax arm (n=195).

Researchers evaluated MRD in patients who achieved a partial response or better. MRD was assessed using allele-specific oligonucleotide polymerase chain reaction, and the definition of MRD negativity was less than one CLL cell per 10,000 lymphocytes.

The researchers assessed MRD in the peripheral blood 3 months after the last dose of rituximab. At that time, 53% (103/194) of patients in the venetoclax-rituximab arm were MRD negative, as were 12% (23/195) of patients in the bendamustine-rituximab arm.

The researchers also assessed MRD in the peripheral blood of patients with a complete response (CR) or CR with incomplete marrow recovery (CRi). MRD negativity was achieved by 3% (6/194) of these patients in the venetoclax-rituximab arm and 2% (3/195) in the bendamustine-rituximab arm.

Three percent (3/106) of patients in the venetoclax arm who achieved CR/CRi were MRD negative in both the peripheral blood and the bone marrow.

“The rates of MRD negativity seen with Venclexta plus rituximab are very encouraging,” said MURANO investigator John Seymour, MBBS, PhD, of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Additional results from the MURANO trial were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March and are included in the prescribing information for venetoclax.

Venetoclax is being developed by AbbVie and Roche. It is jointly commercialized by AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, in the U.S. and by AbbVie outside the U.S.

Eye Can’t See a Thing

About 10 years ago, this 63-year-old man noticed a lesion on his eyelid. It didn’t bother him, so he ignored it—until recently, when it reached a size sufficient to interfere with his vision. This development, and subsequent commentary from friends concerned by its proximity to his eye and fears of cancer, disturbed him enough to seek evaluation.

He first consulted an ophthalmologist, who provided a diagnosis that the patient promptly forgot. However, he was also advised to see a dermatologist or plastic surgeon for further evaluation, since the lesion does not affect the eye itself. The patient wants the lesion removed but seeks a dermatology referral first.

He denies pain, discomfort, or trauma to the affected area.

EXAMINATION

A translucent, round, 7-mm cystic lesion is located on the left lateral lower eyelid just below the margin, resembling a bleb. No redness is seen in the area. Palpation confirms the soft, cystic nature of the lesion.

Examination of the other eye and the rest of the patient’s facial skin reveals no abnormalities.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical presentation of an apocrine hidrocystoma (AH), a benign lesion of uncertain etiology. The eyelid is rich in apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands, all of which can transform into cysts via traumatic plugging.

AH is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, or sudoriferous cyst. It is an entity distinct from chalazions (a granulomatous reaction to sebaceous glands in the eyelid) and lacrimal duct cysts. The differential includes basal cell carcinoma, intradermal nevus, and eccrine cyst.

In my experience, merely incising and draining the cyst is useless in the long run; while this does reduce swelling, it also invites recurrence. Therefore, removal by saucerization and cauterization of the base is the best treatment option.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Apocrine hidrocystomas (AHs) are benign cysts derived from plugged apocrine sweat glands, which are found in numerous areas around the body, including the eyes.

- AHs are also known as cystadenomas, Moll gland cysts, or sudoriferous cysts.

- Though AHs are often found near the eye, they are not technically an eye problem—but they do have potential to obstruct the visual field.

- Removal is usually by saucerization, with cautery of the base for hemostasis and prevention of recurrence.

About 10 years ago, this 63-year-old man noticed a lesion on his eyelid. It didn’t bother him, so he ignored it—until recently, when it reached a size sufficient to interfere with his vision. This development, and subsequent commentary from friends concerned by its proximity to his eye and fears of cancer, disturbed him enough to seek evaluation.

He first consulted an ophthalmologist, who provided a diagnosis that the patient promptly forgot. However, he was also advised to see a dermatologist or plastic surgeon for further evaluation, since the lesion does not affect the eye itself. The patient wants the lesion removed but seeks a dermatology referral first.

He denies pain, discomfort, or trauma to the affected area.

EXAMINATION

A translucent, round, 7-mm cystic lesion is located on the left lateral lower eyelid just below the margin, resembling a bleb. No redness is seen in the area. Palpation confirms the soft, cystic nature of the lesion.

Examination of the other eye and the rest of the patient’s facial skin reveals no abnormalities.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical presentation of an apocrine hidrocystoma (AH), a benign lesion of uncertain etiology. The eyelid is rich in apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands, all of which can transform into cysts via traumatic plugging.

AH is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, or sudoriferous cyst. It is an entity distinct from chalazions (a granulomatous reaction to sebaceous glands in the eyelid) and lacrimal duct cysts. The differential includes basal cell carcinoma, intradermal nevus, and eccrine cyst.

In my experience, merely incising and draining the cyst is useless in the long run; while this does reduce swelling, it also invites recurrence. Therefore, removal by saucerization and cauterization of the base is the best treatment option.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Apocrine hidrocystomas (AHs) are benign cysts derived from plugged apocrine sweat glands, which are found in numerous areas around the body, including the eyes.

- AHs are also known as cystadenomas, Moll gland cysts, or sudoriferous cysts.

- Though AHs are often found near the eye, they are not technically an eye problem—but they do have potential to obstruct the visual field.

- Removal is usually by saucerization, with cautery of the base for hemostasis and prevention of recurrence.

About 10 years ago, this 63-year-old man noticed a lesion on his eyelid. It didn’t bother him, so he ignored it—until recently, when it reached a size sufficient to interfere with his vision. This development, and subsequent commentary from friends concerned by its proximity to his eye and fears of cancer, disturbed him enough to seek evaluation.

He first consulted an ophthalmologist, who provided a diagnosis that the patient promptly forgot. However, he was also advised to see a dermatologist or plastic surgeon for further evaluation, since the lesion does not affect the eye itself. The patient wants the lesion removed but seeks a dermatology referral first.

He denies pain, discomfort, or trauma to the affected area.

EXAMINATION

A translucent, round, 7-mm cystic lesion is located on the left lateral lower eyelid just below the margin, resembling a bleb. No redness is seen in the area. Palpation confirms the soft, cystic nature of the lesion.

Examination of the other eye and the rest of the patient’s facial skin reveals no abnormalities.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a typical presentation of an apocrine hidrocystoma (AH), a benign lesion of uncertain etiology. The eyelid is rich in apocrine, eccrine, and sebaceous glands, all of which can transform into cysts via traumatic plugging.

AH is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, or sudoriferous cyst. It is an entity distinct from chalazions (a granulomatous reaction to sebaceous glands in the eyelid) and lacrimal duct cysts. The differential includes basal cell carcinoma, intradermal nevus, and eccrine cyst.

In my experience, merely incising and draining the cyst is useless in the long run; while this does reduce swelling, it also invites recurrence. Therefore, removal by saucerization and cauterization of the base is the best treatment option.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Apocrine hidrocystomas (AHs) are benign cysts derived from plugged apocrine sweat glands, which are found in numerous areas around the body, including the eyes.

- AHs are also known as cystadenomas, Moll gland cysts, or sudoriferous cysts.

- Though AHs are often found near the eye, they are not technically an eye problem—but they do have potential to obstruct the visual field.

- Removal is usually by saucerization, with cautery of the base for hemostasis and prevention of recurrence.

Manic after having found a ‘cure’ for Alzheimer’s disease

CASE Reckless driving, impulse buying

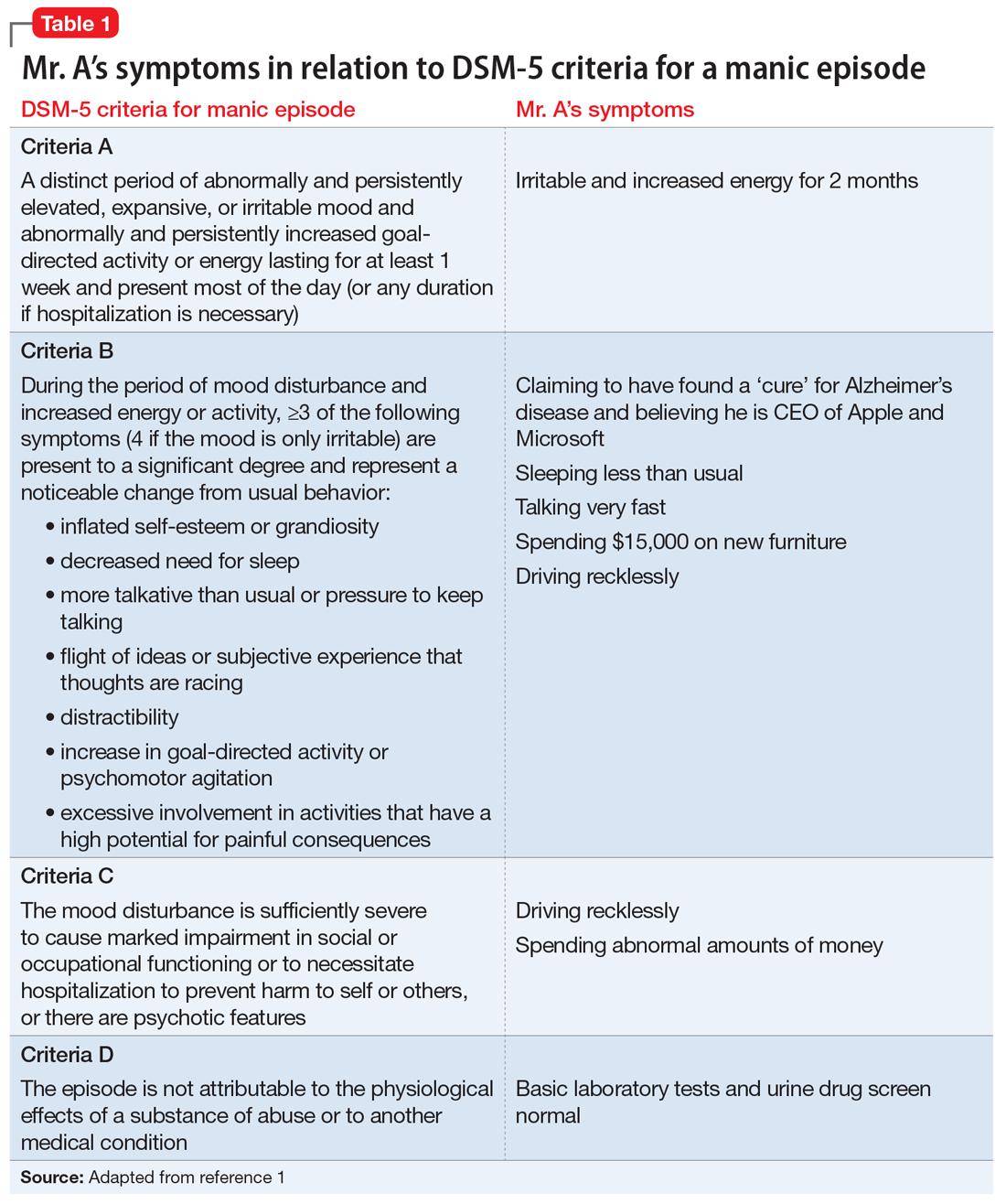

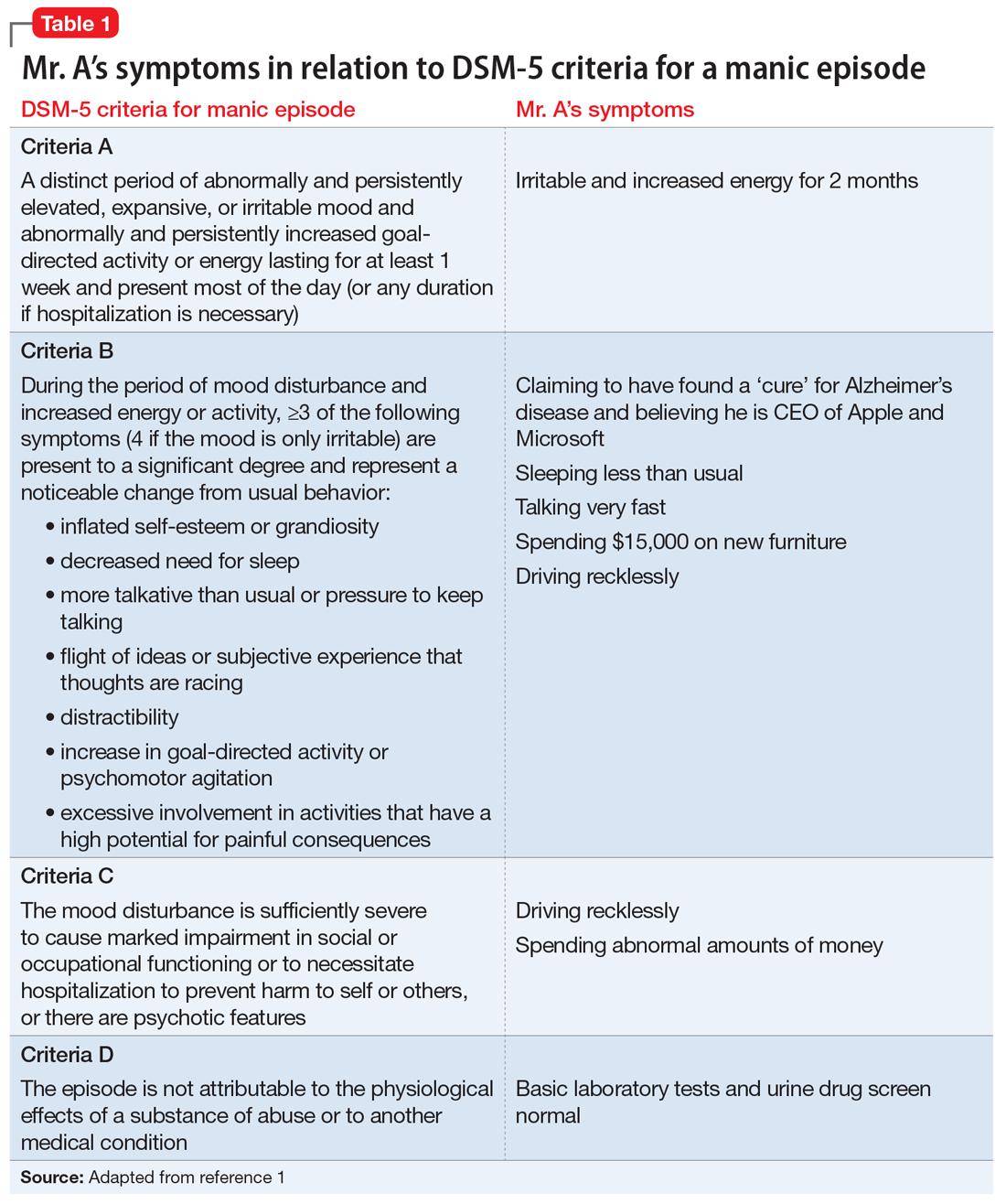

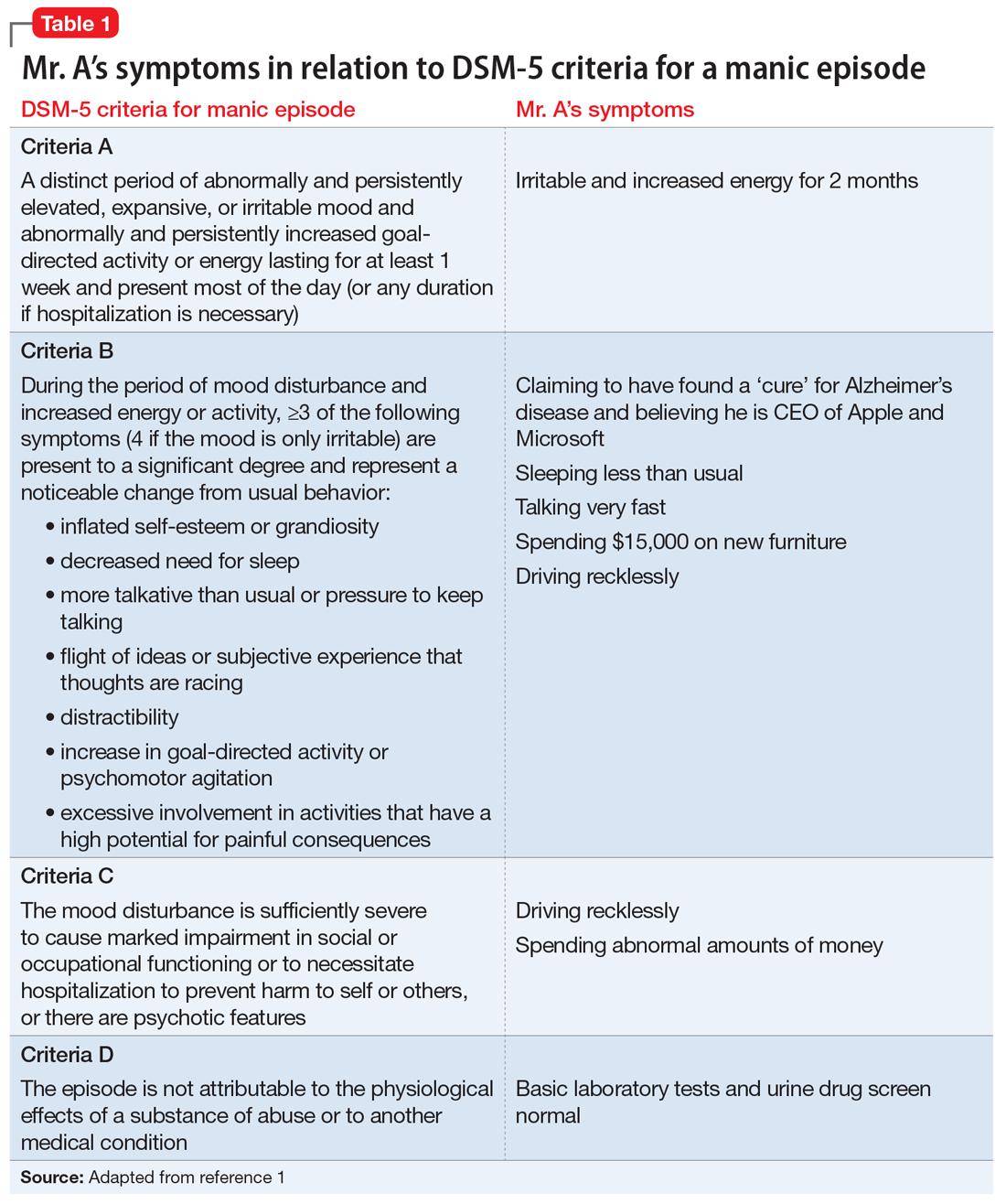

Mr. A, age 73, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit at a community hospital for evaluation of a psychotic episode. His admission to the unit was initiated by his primary care physician, who noted that Mr. A was “not making sense” during a routine visit. Mr. A was speaking rapidly about how he had discovered that high-dose omega-3 fatty acid supplements were a “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease. He also believes that he was recently appointed as CEO of Microsoft and Apple for his discoveries.

Three months earlier, Mr. A had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (10 to 15 g/d) because he believed they were the cure for memory problems, pain, and depression. At that time, he discontinued taking nortriptyline, 25 mg/d, and citalopram, 40 mg/d, which his outpatient psychiatrist had prescribed for major depressive disorder (MDD). Mr. A also had stopped taking buprenorphine, 2 mg, sublingual, 4 times a day, which he had been prescribed for chronic pain.

Mr. A’s wife reports that during the last 2 months, her husband had become irritable, impulsive, grandiose, and was sleeping very little. She added that although her husband’s ophthalmologist had advised him to not drive due to impaired vision, he had been driving recklessly across the metropolitan area. He had also spent nearly $15,000 buying furniture and other items for their home.

In addition to MDD, Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain. He has been taking vitamin D3, 2,000 U/d, as a nutritional supplement.

[polldaddy:10091672]

The authors’ observations

Mr. A met the DSM-5 criteria for a manic episode (Table 11). His manic and delusional symptoms are new. He has a long-standing diagnosis of MDD, which for many years had been successfully treated with antidepressants without a manic switch. The absence of a manic switch when treated with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer suggested that Mr. A did not have bipolarity in terms of a mood disorder diathesis.2 In addition, it would be unusual for an individual to develop a new-onset or primary bipolar disorder after age 60. Individuals in this age group who present with manic symptoms for the first time are preponderantly found to have a general medical or iatrogenic cause for the emergence of these symptoms.3 Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain.

Typically a sedentary man, Mr. A had been exhibiting disinhibited behavior, grandiosity, insomnia, and psychosis. These symptoms began 3 months before he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, when he had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Continue to: EVALUATION Persistent mania

EVALUATION Persistent mania

On initial examination, Mr. A is upset and irritable. He is casually dressed and well-groomed. He lacks insight and says he was brought to the hospital against his will, and it is his wife “who is the one who is crazy.” He is oriented to person, place, and time. At times he is found roaming the hallways, being intrusive, hyperverbal, and tangential with pressured speech. He is very difficult to redirect, and regularly interrupts the interview. His vital signs are stable. He walks well, with slow and steady gait, and displays no tremor or bradykinesia.

[polldaddy:10091674]

The authors’ observations

In order to rule out organic causes, a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid profile, urine drug screen, and brain MRI were ordered. No abnormalities were found. DHA and EPA levels were not measured because such testing was not available at the laboratory at the hospital.

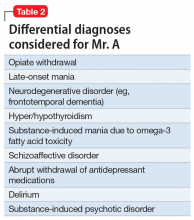

Mania emerging after the sixth decade of life is a rare occurrence. Therefore, we made a substantial effort to try to find another cause that might explain Mr. A’s unusual presentation (Table 2).

Omega-3 fatty acid–induced mania. The major types of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are EPA and DHA and their precursor, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). EPA and DHA are found primarily in fatty fish, such as salmon, and in fish oil supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids have beneficial anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroplastic effects.4 Having properties similar to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help prevent depression, have few interactions with other medications, and have a lower adverse-effect burden than antidepressants. They have been found to be beneficial as a maintenance treatment and for prevention of depressive episodes in bipolar depression, but no positive association has been found for bipolar mania.5

Continue to: However, very limited evidence suggests...

However, very limited evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplements, particularly those with flaxseed oil, can induce hypomania or mania. This association was first reported by Rudin6 in 1981, and later reported in other studies.7 How omega-3 fatty acids might induce mania is unclear.

Mr. A was reportedly taking high doses of an omega-3 fatty acid supplement. We hypothesized that the antidepressant effect of this supplement may have precipitated a manic episode. Mr. A had no history of manic episodes in the past and was stable during the treatment with the outpatient psychiatrist. A first episode mania in the seventh decade of life would be highly unusual without an organic etiology. After laboratory tests found no abnormalities that would point to an organic etiology, iatrogenic causes were considered. After a review of the literature, there was anecdotal evidence for the induction of mania in clinical trials studying the effects of omega-3 supplements on affective disorders.

This led us to ask: How much omega-3 fatty acid supplements, if any, can a patient with a depressive or bipolar disorder safely take? Currently, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are not FDA-approved for the treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. However, patients may take 1.5 to 2 g/d for MDD. Further research is needed to determine the optimal dose. It is unclear at this time if omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has any benefit in the acute or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

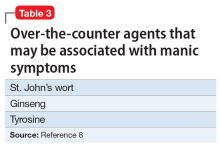

Alternative nutritional supplements for mood disorders. Traditionally, mood disorders, such as MDD and bipolar disorder, have been treated with psychotropic medications. However, through the years, sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of nutritional interventions as a cost-effective approach to preventing and treating these conditions.5 Proponents of this approach believe such supplements can increase efficacy, as well as decrease the required dose of psychotropic medications, thus potentially minimizing adverse effects. However, their overuse can pose a potential threat of toxicity or unexpected adverse effects, such as precipitation of mania. Table 38 lists over-the-counter nutritional and/or herbal agents that may cause mania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

On admission, Mr. A receives a dose of

[polldaddy:10091676]

The authors’ observations

During an acute manic episode, the goal of treatment is urgent mood stabilization. Monotherapy can be used; however, in emergent settings, a combination is often used for a rapid response. The most commonly used agents are lithium, anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, and antipsychotics.9 In addition, benzodiazepines can be used for insomnia, agitation, or anxiety. The decision to use lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic depends upon the specific medication’s adverse effects, the patient’s medical history, previous medication trials, drug–drug interactions, patient preference, and cost.

Because Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, lithium was contraindicated.

[polldaddy:10091678]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

After the acute episode of mania resolves, maintenance pharmacotherapy typically involves continuing the same regimen that achieved mood stabilization. Monotherapy is typically preferred to combination therapy, but it is not always possible after a manic episode.10 A reasonable approach is to slowly taper the antipsychotic after several months of dual therapy if symptoms continue to be well-controlled. Further adjustments may be necessary, depending on the medications’ adverse effects. Moreover, further acute episodes of mania or depression will also determine future treatment.

OUTCOME Resolution of delusions

Mr. A is discharged 30 days after admission. At this point, his acute manic episode has resolved with non-tangential, non-pressured speech, improved sleep, and decreased impulsivity. His grandiose delusions also have resolved. He is prescribed valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and risperidone, 6 mg/d at bedtime, under the care of his outpatient psychiatrist.

Bottom Line

Initial presentation of a manic episode in an older patient is rare. It is important to rule out organic causes. Weak evidence suggests omega-3 fatty acid supplements may have the potential to induce mania in certain patients.

Related Resource

- Ramaswamy S, Driscoll D, Rodriguez A, et al. Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(7):34-38,40,41-45.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Suboxone, Subutex

Citalopram • Celexa

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam• Ativan

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

3. Sami M, Khan H, Nilforooshan R. Late onset mania as an organic syndrome: a review of case reports in the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015:188:226-231.

4. Su KP, Matsuoka Y, Pae CU. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):129-137.

5. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

6. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(9):837-850.

7. Su KP, Shen WW, Huang SY. Are omega3 fatty acids beneficial in depression but not mania? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):716-717.

8. Joshi K, Faubion M. Mania and psychosis associated with St. John’s wort and ginseng. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(9):56-61.

9. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

10. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al; Trial 127 Investigators. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476-488.

CASE Reckless driving, impulse buying

Mr. A, age 73, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit at a community hospital for evaluation of a psychotic episode. His admission to the unit was initiated by his primary care physician, who noted that Mr. A was “not making sense” during a routine visit. Mr. A was speaking rapidly about how he had discovered that high-dose omega-3 fatty acid supplements were a “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease. He also believes that he was recently appointed as CEO of Microsoft and Apple for his discoveries.

Three months earlier, Mr. A had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (10 to 15 g/d) because he believed they were the cure for memory problems, pain, and depression. At that time, he discontinued taking nortriptyline, 25 mg/d, and citalopram, 40 mg/d, which his outpatient psychiatrist had prescribed for major depressive disorder (MDD). Mr. A also had stopped taking buprenorphine, 2 mg, sublingual, 4 times a day, which he had been prescribed for chronic pain.

Mr. A’s wife reports that during the last 2 months, her husband had become irritable, impulsive, grandiose, and was sleeping very little. She added that although her husband’s ophthalmologist had advised him to not drive due to impaired vision, he had been driving recklessly across the metropolitan area. He had also spent nearly $15,000 buying furniture and other items for their home.

In addition to MDD, Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain. He has been taking vitamin D3, 2,000 U/d, as a nutritional supplement.

[polldaddy:10091672]

The authors’ observations

Mr. A met the DSM-5 criteria for a manic episode (Table 11). His manic and delusional symptoms are new. He has a long-standing diagnosis of MDD, which for many years had been successfully treated with antidepressants without a manic switch. The absence of a manic switch when treated with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer suggested that Mr. A did not have bipolarity in terms of a mood disorder diathesis.2 In addition, it would be unusual for an individual to develop a new-onset or primary bipolar disorder after age 60. Individuals in this age group who present with manic symptoms for the first time are preponderantly found to have a general medical or iatrogenic cause for the emergence of these symptoms.3 Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain.

Typically a sedentary man, Mr. A had been exhibiting disinhibited behavior, grandiosity, insomnia, and psychosis. These symptoms began 3 months before he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, when he had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Continue to: EVALUATION Persistent mania

EVALUATION Persistent mania

On initial examination, Mr. A is upset and irritable. He is casually dressed and well-groomed. He lacks insight and says he was brought to the hospital against his will, and it is his wife “who is the one who is crazy.” He is oriented to person, place, and time. At times he is found roaming the hallways, being intrusive, hyperverbal, and tangential with pressured speech. He is very difficult to redirect, and regularly interrupts the interview. His vital signs are stable. He walks well, with slow and steady gait, and displays no tremor or bradykinesia.

[polldaddy:10091674]

The authors’ observations

In order to rule out organic causes, a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid profile, urine drug screen, and brain MRI were ordered. No abnormalities were found. DHA and EPA levels were not measured because such testing was not available at the laboratory at the hospital.

Mania emerging after the sixth decade of life is a rare occurrence. Therefore, we made a substantial effort to try to find another cause that might explain Mr. A’s unusual presentation (Table 2).

Omega-3 fatty acid–induced mania. The major types of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are EPA and DHA and their precursor, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). EPA and DHA are found primarily in fatty fish, such as salmon, and in fish oil supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids have beneficial anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroplastic effects.4 Having properties similar to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help prevent depression, have few interactions with other medications, and have a lower adverse-effect burden than antidepressants. They have been found to be beneficial as a maintenance treatment and for prevention of depressive episodes in bipolar depression, but no positive association has been found for bipolar mania.5

Continue to: However, very limited evidence suggests...

However, very limited evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplements, particularly those with flaxseed oil, can induce hypomania or mania. This association was first reported by Rudin6 in 1981, and later reported in other studies.7 How omega-3 fatty acids might induce mania is unclear.

Mr. A was reportedly taking high doses of an omega-3 fatty acid supplement. We hypothesized that the antidepressant effect of this supplement may have precipitated a manic episode. Mr. A had no history of manic episodes in the past and was stable during the treatment with the outpatient psychiatrist. A first episode mania in the seventh decade of life would be highly unusual without an organic etiology. After laboratory tests found no abnormalities that would point to an organic etiology, iatrogenic causes were considered. After a review of the literature, there was anecdotal evidence for the induction of mania in clinical trials studying the effects of omega-3 supplements on affective disorders.

This led us to ask: How much omega-3 fatty acid supplements, if any, can a patient with a depressive or bipolar disorder safely take? Currently, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are not FDA-approved for the treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. However, patients may take 1.5 to 2 g/d for MDD. Further research is needed to determine the optimal dose. It is unclear at this time if omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has any benefit in the acute or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Alternative nutritional supplements for mood disorders. Traditionally, mood disorders, such as MDD and bipolar disorder, have been treated with psychotropic medications. However, through the years, sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of nutritional interventions as a cost-effective approach to preventing and treating these conditions.5 Proponents of this approach believe such supplements can increase efficacy, as well as decrease the required dose of psychotropic medications, thus potentially minimizing adverse effects. However, their overuse can pose a potential threat of toxicity or unexpected adverse effects, such as precipitation of mania. Table 38 lists over-the-counter nutritional and/or herbal agents that may cause mania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

On admission, Mr. A receives a dose of

[polldaddy:10091676]

The authors’ observations

During an acute manic episode, the goal of treatment is urgent mood stabilization. Monotherapy can be used; however, in emergent settings, a combination is often used for a rapid response. The most commonly used agents are lithium, anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, and antipsychotics.9 In addition, benzodiazepines can be used for insomnia, agitation, or anxiety. The decision to use lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic depends upon the specific medication’s adverse effects, the patient’s medical history, previous medication trials, drug–drug interactions, patient preference, and cost.

Because Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, lithium was contraindicated.

[polldaddy:10091678]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

After the acute episode of mania resolves, maintenance pharmacotherapy typically involves continuing the same regimen that achieved mood stabilization. Monotherapy is typically preferred to combination therapy, but it is not always possible after a manic episode.10 A reasonable approach is to slowly taper the antipsychotic after several months of dual therapy if symptoms continue to be well-controlled. Further adjustments may be necessary, depending on the medications’ adverse effects. Moreover, further acute episodes of mania or depression will also determine future treatment.

OUTCOME Resolution of delusions

Mr. A is discharged 30 days after admission. At this point, his acute manic episode has resolved with non-tangential, non-pressured speech, improved sleep, and decreased impulsivity. His grandiose delusions also have resolved. He is prescribed valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and risperidone, 6 mg/d at bedtime, under the care of his outpatient psychiatrist.

Bottom Line

Initial presentation of a manic episode in an older patient is rare. It is important to rule out organic causes. Weak evidence suggests omega-3 fatty acid supplements may have the potential to induce mania in certain patients.

Related Resource

- Ramaswamy S, Driscoll D, Rodriguez A, et al. Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(7):34-38,40,41-45.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Suboxone, Subutex

Citalopram • Celexa

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam• Ativan

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproic acid • Depakote

CASE Reckless driving, impulse buying

Mr. A, age 73, is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit at a community hospital for evaluation of a psychotic episode. His admission to the unit was initiated by his primary care physician, who noted that Mr. A was “not making sense” during a routine visit. Mr. A was speaking rapidly about how he had discovered that high-dose omega-3 fatty acid supplements were a “cure” for Alzheimer’s disease. He also believes that he was recently appointed as CEO of Microsoft and Apple for his discoveries.

Three months earlier, Mr. A had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (10 to 15 g/d) because he believed they were the cure for memory problems, pain, and depression. At that time, he discontinued taking nortriptyline, 25 mg/d, and citalopram, 40 mg/d, which his outpatient psychiatrist had prescribed for major depressive disorder (MDD). Mr. A also had stopped taking buprenorphine, 2 mg, sublingual, 4 times a day, which he had been prescribed for chronic pain.

Mr. A’s wife reports that during the last 2 months, her husband had become irritable, impulsive, grandiose, and was sleeping very little. She added that although her husband’s ophthalmologist had advised him to not drive due to impaired vision, he had been driving recklessly across the metropolitan area. He had also spent nearly $15,000 buying furniture and other items for their home.

In addition to MDD, Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain. He has been taking vitamin D3, 2,000 U/d, as a nutritional supplement.

[polldaddy:10091672]

The authors’ observations

Mr. A met the DSM-5 criteria for a manic episode (Table 11). His manic and delusional symptoms are new. He has a long-standing diagnosis of MDD, which for many years had been successfully treated with antidepressants without a manic switch. The absence of a manic switch when treated with antidepressants without a mood stabilizer suggested that Mr. A did not have bipolarity in terms of a mood disorder diathesis.2 In addition, it would be unusual for an individual to develop a new-onset or primary bipolar disorder after age 60. Individuals in this age group who present with manic symptoms for the first time are preponderantly found to have a general medical or iatrogenic cause for the emergence of these symptoms.3 Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and chronic pain.

Typically a sedentary man, Mr. A had been exhibiting disinhibited behavior, grandiosity, insomnia, and psychosis. These symptoms began 3 months before he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, when he had started taking high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Continue to: EVALUATION Persistent mania

EVALUATION Persistent mania

On initial examination, Mr. A is upset and irritable. He is casually dressed and well-groomed. He lacks insight and says he was brought to the hospital against his will, and it is his wife “who is the one who is crazy.” He is oriented to person, place, and time. At times he is found roaming the hallways, being intrusive, hyperverbal, and tangential with pressured speech. He is very difficult to redirect, and regularly interrupts the interview. His vital signs are stable. He walks well, with slow and steady gait, and displays no tremor or bradykinesia.

[polldaddy:10091674]

The authors’ observations

In order to rule out organic causes, a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid profile, urine drug screen, and brain MRI were ordered. No abnormalities were found. DHA and EPA levels were not measured because such testing was not available at the laboratory at the hospital.

Mania emerging after the sixth decade of life is a rare occurrence. Therefore, we made a substantial effort to try to find another cause that might explain Mr. A’s unusual presentation (Table 2).

Omega-3 fatty acid–induced mania. The major types of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are EPA and DHA and their precursor, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). EPA and DHA are found primarily in fatty fish, such as salmon, and in fish oil supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids have beneficial anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and neuroplastic effects.4 Having properties similar to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, omega-3 fatty acids are thought to help prevent depression, have few interactions with other medications, and have a lower adverse-effect burden than antidepressants. They have been found to be beneficial as a maintenance treatment and for prevention of depressive episodes in bipolar depression, but no positive association has been found for bipolar mania.5

Continue to: However, very limited evidence suggests...

However, very limited evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acid supplements, particularly those with flaxseed oil, can induce hypomania or mania. This association was first reported by Rudin6 in 1981, and later reported in other studies.7 How omega-3 fatty acids might induce mania is unclear.

Mr. A was reportedly taking high doses of an omega-3 fatty acid supplement. We hypothesized that the antidepressant effect of this supplement may have precipitated a manic episode. Mr. A had no history of manic episodes in the past and was stable during the treatment with the outpatient psychiatrist. A first episode mania in the seventh decade of life would be highly unusual without an organic etiology. After laboratory tests found no abnormalities that would point to an organic etiology, iatrogenic causes were considered. After a review of the literature, there was anecdotal evidence for the induction of mania in clinical trials studying the effects of omega-3 supplements on affective disorders.

This led us to ask: How much omega-3 fatty acid supplements, if any, can a patient with a depressive or bipolar disorder safely take? Currently, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are not FDA-approved for the treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. However, patients may take 1.5 to 2 g/d for MDD. Further research is needed to determine the optimal dose. It is unclear at this time if omega-3 fatty acid supplementation has any benefit in the acute or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Alternative nutritional supplements for mood disorders. Traditionally, mood disorders, such as MDD and bipolar disorder, have been treated with psychotropic medications. However, through the years, sporadic studies have examined the efficacy of nutritional interventions as a cost-effective approach to preventing and treating these conditions.5 Proponents of this approach believe such supplements can increase efficacy, as well as decrease the required dose of psychotropic medications, thus potentially minimizing adverse effects. However, their overuse can pose a potential threat of toxicity or unexpected adverse effects, such as precipitation of mania. Table 38 lists over-the-counter nutritional and/or herbal agents that may cause mania.

Continue to: TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

TREATMENT Nonadherence leads to a court order

On admission, Mr. A receives a dose of

[polldaddy:10091676]

The authors’ observations

During an acute manic episode, the goal of treatment is urgent mood stabilization. Monotherapy can be used; however, in emergent settings, a combination is often used for a rapid response. The most commonly used agents are lithium, anticonvulsants such as valproic acid, and antipsychotics.9 In addition, benzodiazepines can be used for insomnia, agitation, or anxiety. The decision to use lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic depends upon the specific medication’s adverse effects, the patient’s medical history, previous medication trials, drug–drug interactions, patient preference, and cost.

Because Mr. A has a history of chronic kidney disease, lithium was contraindicated.

[polldaddy:10091678]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

After the acute episode of mania resolves, maintenance pharmacotherapy typically involves continuing the same regimen that achieved mood stabilization. Monotherapy is typically preferred to combination therapy, but it is not always possible after a manic episode.10 A reasonable approach is to slowly taper the antipsychotic after several months of dual therapy if symptoms continue to be well-controlled. Further adjustments may be necessary, depending on the medications’ adverse effects. Moreover, further acute episodes of mania or depression will also determine future treatment.

OUTCOME Resolution of delusions

Mr. A is discharged 30 days after admission. At this point, his acute manic episode has resolved with non-tangential, non-pressured speech, improved sleep, and decreased impulsivity. His grandiose delusions also have resolved. He is prescribed valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, and risperidone, 6 mg/d at bedtime, under the care of his outpatient psychiatrist.

Bottom Line

Initial presentation of a manic episode in an older patient is rare. It is important to rule out organic causes. Weak evidence suggests omega-3 fatty acid supplements may have the potential to induce mania in certain patients.

Related Resource

- Ramaswamy S, Driscoll D, Rodriguez A, et al. Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(7):34-38,40,41-45.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Suboxone, Subutex

Citalopram • Celexa

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen • Vicodin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam• Ativan

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

3. Sami M, Khan H, Nilforooshan R. Late onset mania as an organic syndrome: a review of case reports in the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015:188:226-231.

4. Su KP, Matsuoka Y, Pae CU. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):129-137.

5. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

6. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(9):837-850.

7. Su KP, Shen WW, Huang SY. Are omega3 fatty acids beneficial in depression but not mania? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):716-717.

8. Joshi K, Faubion M. Mania and psychosis associated with St. John’s wort and ginseng. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(9):56-61.

9. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

10. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al; Trial 127 Investigators. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476-488.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495-553.

3. Sami M, Khan H, Nilforooshan R. Late onset mania as an organic syndrome: a review of case reports in the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015:188:226-231.

4. Su KP, Matsuoka Y, Pae CU. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):129-137.

5. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

6. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(9):837-850.

7. Su KP, Shen WW, Huang SY. Are omega3 fatty acids beneficial in depression but not mania? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):716-717.

8. Joshi K, Faubion M. Mania and psychosis associated with St. John’s wort and ginseng. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(9):56-61.

9. Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. The world federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(2):85-116.

10. Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, et al; Trial 127 Investigators. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476-488.

Outpatient costs soar for Medicare patients with chronic hepatitis B

The average cost of outpatient care for Medicare recipients with chronic hepatitis B (CH-B) rose by 400% from 2005 to 2014, according to investigators.

Inpatient costs also increased, although less dramatically, reported lead author Min Kim, MD, of the Inova Fairfax Hospital Center for Liver Diseases in Falls Church, Virginia, and her colleagues. The causes of these spending hikes may range from policy changes and expanded screening to an aging immigrant population.

“According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, from 1988 to 2012 most people with CH-B in the United States were foreign born and accounted for up to 70% of all CH-B infections,” the authors wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. “The Centers for Disease Control [and Prevention] estimates that Asians, who comprise 5% of the U.S. population, account for 50% of all chronic CH-B infections.” Despite these statistics, the clinical and economic impacts of an aging immigrant population are unknown. The investigators therefore assessed patient characteristics associated with increased 1-year mortality and the impact of demographic changes on Medicare costs.

The retrospective study began with a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries from 2005 to 2014. From this group, 18,603 patients with CH-B were identified by ICD-9 codes V02.61, 070.2, 070.3, 070.42, and 070.52. Patients with ICD-9-CM codes of 197.7, 155.1, or 155.2 were excluded, as were records containing insufficient information about year, region, or race. Patients were analyzed collectively and as inpatients (n = 6,550) or outpatients (n = 13,648).

Cost of care (per patient, per year) and 1-year mortality were evaluated. Patient characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, type of Medicare eligibility, length of stay, Charlson comorbidity index, presence of decompensated cirrhosis, and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Most dramatically, outpatient charges rose more than 400% during the study period, from $9,257 in 2005 to $47,864 in 2014 (P less than .001). Inpatient charges increased by almost 50%, from $66,610 to $94,221 (P less than .001). (All values converted to 2016 dollars.)

Although the increase in outpatient costs appears seismic, the authors noted that costs held steady from 2005 to 2010 before spiking dramatically, reaching a peak of $58,450 in 2013 before settling down to $47,864 the following year. This spike may be caused by changes in screening measures and policies. In 2009, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases expanded screening guidelines to include previously ineligible patients with CH-B, and in 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services expanded ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for CH-B from 9 to 25.

“It seems plausible that the increase in CH-B prevalence, and its associated costs, might actually be a reflection of [these factors],” the authors noted. Still, “additional studies are needed to clarify this observation.”

Turning to patient characteristics, the authors reported that 1-year mortality was independently associated most strongly with decompensated cirrhosis (odds ratio, 3.02) and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR, 2.64). In comparison with white patients, Asians were less likely to die (OR, 0.47).

“It is possible that this can be explained through differences in transmission mode and disease progression of CH-B between these two demographics,” the authors wrote. “A majority of Asian Medicare recipients with CH-B likely acquired it perinatally and did not develop significant liver disease. In contrast, whites with CH-B generally acquired it in adulthood, increasing the chance of developing liver disease.”

Over the 10-year study period, Medicare beneficiaries with CH-B became more frequently Asian and less frequently male. While the number of outpatient visits and average Charlson comorbidity index increased, decreases were reported for length of stay, rates of 1-year mortality, hospitalization, and HCC – the latter of which is most closely associated with higher costs of care.

The investigators suggested that the decreased incidence of HCC was caused by “better screening programs for HCC and/or more widespread use of antiviral treatment for CH-B.”

“Although advances in antiviral treatment have effectively reduced hospitalization and disease progression,” the authors wrote, “vulnerable groups – especially immigrants and individuals living in poverty – present an important challenge for better identification of infected individuals and their linkage to care. In this context, it is vital to target these cohorts to reduce further mortality and resource utilization, as well as optimize long-term public health and financial benefits.”

Study funding was provided by Seattle Genetics. One coauthor reported compensation from Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: Kim M et al. J Clin Gastro. 2018 Aug 13. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001110.

The average cost of outpatient care for Medicare recipients with chronic hepatitis B (CH-B) rose by 400% from 2005 to 2014, according to investigators.

Inpatient costs also increased, although less dramatically, reported lead author Min Kim, MD, of the Inova Fairfax Hospital Center for Liver Diseases in Falls Church, Virginia, and her colleagues. The causes of these spending hikes may range from policy changes and expanded screening to an aging immigrant population.

“According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, from 1988 to 2012 most people with CH-B in the United States were foreign born and accounted for up to 70% of all CH-B infections,” the authors wrote in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. “The Centers for Disease Control [and Prevention] estimates that Asians, who comprise 5% of the U.S. population, account for 50% of all chronic CH-B infections.” Despite these statistics, the clinical and economic impacts of an aging immigrant population are unknown. The investigators therefore assessed patient characteristics associated with increased 1-year mortality and the impact of demographic changes on Medicare costs.

The retrospective study began with a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries from 2005 to 2014. From this group, 18,603 patients with CH-B were identified by ICD-9 codes V02.61, 070.2, 070.3, 070.42, and 070.52. Patients with ICD-9-CM codes of 197.7, 155.1, or 155.2 were excluded, as were records containing insufficient information about year, region, or race. Patients were analyzed collectively and as inpatients (n = 6,550) or outpatients (n = 13,648).