User login

New guidelines frame treatment options for Castleman disease

The (MCD), although adjuvant chemotherapy can be critical in severe cases, according to the first-ever consensus treatment guidelines based on symptom severity.

Early intervention with combination chemotherapy may prevent a fatal outcome in patients with severe idiopathic MCD, according to the guidelines, which are based on input from 42 experts from 10 countries.

The guidelines should help clinicians select therapy, evaluate response, and thereby improve outcomes for this difficult-to-treat disease, according to guideline co-author David C. Fajgenbaum, MD, who is himself an idiopathic MCD patient. Frits van Rhee, MD, PhD, is the first author of the guidelines.*

“Right now we recommend siltuximab first line for everyone,” Dr. Fajgenbaum said in an interview, “but if we continue to dig deeper, it may be that there are clinical cases within idiopathic MCD that we think are even better candidates than others, and there may be alternative therapies for other patients.”

Experts reviewed published literature and a series of 344 clinical cases to develop the guidelines, which are published in the journal Blood.

Treating idiopathic MCD is challenging because of the rarity and heterogeneity of the disease, among other factors, said Dr. Fajgenbaum, of the division of translational medicine and human genetics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Some 6,000-7,000 cases of Castleman disease are diagnosed yearly, and of those, only about 1,000 cases are idiopathic MCD, according to Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“Even within idiopathic MCD, there is some heterogeneity,” he said. “Some patients present in the intensive care unit with life-threatening multiple organ failure and will die within weeks of presentation, whereas others will have a slower presentation and certainly not nearly as aggressive presentation.”

Although the exact etiology of idiopathic MCD is unknown, human interleukin (IL)-6 is the most common pathological driver, experts said in the guidelines.

Siltuximab and tocilizumab are two IL-6–directed therapies used to treat multicentric Castleman disease, with siltuximab targeting IL-6 itself and tocilizumab targeting the IL-6 receptor. Siltuximab is recommended as the first choice because of rigorous data supporting its use, including randomized clinical trial data, while tocilizumab is recommended if siltuximab is not available.

However, clinicians need to carefully monitor laboratory results and clinical features for patients on these drugs because about 50% of idiopathic MCD patients don’t have a satisfactory response to first-line anti–IL-6 treatments, Dr. Fajgenbaum said.

“Once you get to second-line therapies, that’s really where the level of evidence is lower,” he said.

Second-line therapy should include rituximab, and immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents or steroids may be added, according to the guidelines.

Third line therapy is “less well defined,” according to the guidelines, and experts generally recommended immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine A, sirolimus, thalidomide, and lenalidomide.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has a high response rate but also a high rate of relapse and significant toxicities, according to the data analysis conducted as part of the guideline development process. Based on that, the experts said to avoid it unless the patient progresses to severe idiopathic MCD.

“Patients who are literally dying in the intensive care unit, given the right combination chemotherapy, can improve within days to weeks and can even leave the hospital,” Dr. Fajgenbaum said. “It’s not necessarily going to be the answer long term, but it can be life saving in the short term. So we recommended a really quite aggressive approach for these patients.”

To bolster the evidence base, investigators in the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) set up an international registry to collect treatment and outcome data for 500 patients. After the first year and a half, 150 patients were enrolled, and the investigators have identified more than 30 drugs that have been used off label to treat idiopathic MCD, according to Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“Some of the drugs are demonstrating efficacy in small numbers,” he said. “With the goal of 500 patients total, we can certainly hope to see some trends.”

Dr. Fajgenbaum was diagnosed with idiopathic MCD as a medical student.

“That certainly served as a very strong personal motivator for me to get involved in the disease,” he said. “But as I’ve gotten more and more involved, I’ve obviously met a lot of other patients, and that really is a huge motivator for all members of the CDCN. We want more options for more patients more quickly so we can help as many people as possible.”

Dr. Fajgenbaum reported research funding from Janssen. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, Celgene, Incyte, Pfizer, Sequenom, and Foundation Medicine, among others.

SOURCE: van Rhee F et al. Blood. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-862334.

This story was updated 10/01/2018.

The (MCD), although adjuvant chemotherapy can be critical in severe cases, according to the first-ever consensus treatment guidelines based on symptom severity.

Early intervention with combination chemotherapy may prevent a fatal outcome in patients with severe idiopathic MCD, according to the guidelines, which are based on input from 42 experts from 10 countries.

The guidelines should help clinicians select therapy, evaluate response, and thereby improve outcomes for this difficult-to-treat disease, according to guideline co-author David C. Fajgenbaum, MD, who is himself an idiopathic MCD patient. Frits van Rhee, MD, PhD, is the first author of the guidelines.*

“Right now we recommend siltuximab first line for everyone,” Dr. Fajgenbaum said in an interview, “but if we continue to dig deeper, it may be that there are clinical cases within idiopathic MCD that we think are even better candidates than others, and there may be alternative therapies for other patients.”

Experts reviewed published literature and a series of 344 clinical cases to develop the guidelines, which are published in the journal Blood.

Treating idiopathic MCD is challenging because of the rarity and heterogeneity of the disease, among other factors, said Dr. Fajgenbaum, of the division of translational medicine and human genetics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Some 6,000-7,000 cases of Castleman disease are diagnosed yearly, and of those, only about 1,000 cases are idiopathic MCD, according to Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“Even within idiopathic MCD, there is some heterogeneity,” he said. “Some patients present in the intensive care unit with life-threatening multiple organ failure and will die within weeks of presentation, whereas others will have a slower presentation and certainly not nearly as aggressive presentation.”

Although the exact etiology of idiopathic MCD is unknown, human interleukin (IL)-6 is the most common pathological driver, experts said in the guidelines.

Siltuximab and tocilizumab are two IL-6–directed therapies used to treat multicentric Castleman disease, with siltuximab targeting IL-6 itself and tocilizumab targeting the IL-6 receptor. Siltuximab is recommended as the first choice because of rigorous data supporting its use, including randomized clinical trial data, while tocilizumab is recommended if siltuximab is not available.

However, clinicians need to carefully monitor laboratory results and clinical features for patients on these drugs because about 50% of idiopathic MCD patients don’t have a satisfactory response to first-line anti–IL-6 treatments, Dr. Fajgenbaum said.

“Once you get to second-line therapies, that’s really where the level of evidence is lower,” he said.

Second-line therapy should include rituximab, and immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents or steroids may be added, according to the guidelines.

Third line therapy is “less well defined,” according to the guidelines, and experts generally recommended immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine A, sirolimus, thalidomide, and lenalidomide.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has a high response rate but also a high rate of relapse and significant toxicities, according to the data analysis conducted as part of the guideline development process. Based on that, the experts said to avoid it unless the patient progresses to severe idiopathic MCD.

“Patients who are literally dying in the intensive care unit, given the right combination chemotherapy, can improve within days to weeks and can even leave the hospital,” Dr. Fajgenbaum said. “It’s not necessarily going to be the answer long term, but it can be life saving in the short term. So we recommended a really quite aggressive approach for these patients.”

To bolster the evidence base, investigators in the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) set up an international registry to collect treatment and outcome data for 500 patients. After the first year and a half, 150 patients were enrolled, and the investigators have identified more than 30 drugs that have been used off label to treat idiopathic MCD, according to Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“Some of the drugs are demonstrating efficacy in small numbers,” he said. “With the goal of 500 patients total, we can certainly hope to see some trends.”

Dr. Fajgenbaum was diagnosed with idiopathic MCD as a medical student.

“That certainly served as a very strong personal motivator for me to get involved in the disease,” he said. “But as I’ve gotten more and more involved, I’ve obviously met a lot of other patients, and that really is a huge motivator for all members of the CDCN. We want more options for more patients more quickly so we can help as many people as possible.”

Dr. Fajgenbaum reported research funding from Janssen. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, Celgene, Incyte, Pfizer, Sequenom, and Foundation Medicine, among others.

SOURCE: van Rhee F et al. Blood. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-862334.

This story was updated 10/01/2018.

The (MCD), although adjuvant chemotherapy can be critical in severe cases, according to the first-ever consensus treatment guidelines based on symptom severity.

Early intervention with combination chemotherapy may prevent a fatal outcome in patients with severe idiopathic MCD, according to the guidelines, which are based on input from 42 experts from 10 countries.

The guidelines should help clinicians select therapy, evaluate response, and thereby improve outcomes for this difficult-to-treat disease, according to guideline co-author David C. Fajgenbaum, MD, who is himself an idiopathic MCD patient. Frits van Rhee, MD, PhD, is the first author of the guidelines.*

“Right now we recommend siltuximab first line for everyone,” Dr. Fajgenbaum said in an interview, “but if we continue to dig deeper, it may be that there are clinical cases within idiopathic MCD that we think are even better candidates than others, and there may be alternative therapies for other patients.”

Experts reviewed published literature and a series of 344 clinical cases to develop the guidelines, which are published in the journal Blood.

Treating idiopathic MCD is challenging because of the rarity and heterogeneity of the disease, among other factors, said Dr. Fajgenbaum, of the division of translational medicine and human genetics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Some 6,000-7,000 cases of Castleman disease are diagnosed yearly, and of those, only about 1,000 cases are idiopathic MCD, according to Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“Even within idiopathic MCD, there is some heterogeneity,” he said. “Some patients present in the intensive care unit with life-threatening multiple organ failure and will die within weeks of presentation, whereas others will have a slower presentation and certainly not nearly as aggressive presentation.”

Although the exact etiology of idiopathic MCD is unknown, human interleukin (IL)-6 is the most common pathological driver, experts said in the guidelines.

Siltuximab and tocilizumab are two IL-6–directed therapies used to treat multicentric Castleman disease, with siltuximab targeting IL-6 itself and tocilizumab targeting the IL-6 receptor. Siltuximab is recommended as the first choice because of rigorous data supporting its use, including randomized clinical trial data, while tocilizumab is recommended if siltuximab is not available.

However, clinicians need to carefully monitor laboratory results and clinical features for patients on these drugs because about 50% of idiopathic MCD patients don’t have a satisfactory response to first-line anti–IL-6 treatments, Dr. Fajgenbaum said.

“Once you get to second-line therapies, that’s really where the level of evidence is lower,” he said.

Second-line therapy should include rituximab, and immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents or steroids may be added, according to the guidelines.

Third line therapy is “less well defined,” according to the guidelines, and experts generally recommended immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine A, sirolimus, thalidomide, and lenalidomide.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has a high response rate but also a high rate of relapse and significant toxicities, according to the data analysis conducted as part of the guideline development process. Based on that, the experts said to avoid it unless the patient progresses to severe idiopathic MCD.

“Patients who are literally dying in the intensive care unit, given the right combination chemotherapy, can improve within days to weeks and can even leave the hospital,” Dr. Fajgenbaum said. “It’s not necessarily going to be the answer long term, but it can be life saving in the short term. So we recommended a really quite aggressive approach for these patients.”

To bolster the evidence base, investigators in the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) set up an international registry to collect treatment and outcome data for 500 patients. After the first year and a half, 150 patients were enrolled, and the investigators have identified more than 30 drugs that have been used off label to treat idiopathic MCD, according to Dr. Fajgenbaum.

“Some of the drugs are demonstrating efficacy in small numbers,” he said. “With the goal of 500 patients total, we can certainly hope to see some trends.”

Dr. Fajgenbaum was diagnosed with idiopathic MCD as a medical student.

“That certainly served as a very strong personal motivator for me to get involved in the disease,” he said. “But as I’ve gotten more and more involved, I’ve obviously met a lot of other patients, and that really is a huge motivator for all members of the CDCN. We want more options for more patients more quickly so we can help as many people as possible.”

Dr. Fajgenbaum reported research funding from Janssen. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, Celgene, Incyte, Pfizer, Sequenom, and Foundation Medicine, among others.

SOURCE: van Rhee F et al. Blood. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-862334.

This story was updated 10/01/2018.

FROM BLOOD

Employing irritable bowel syndrome patient-reported outcomes in the clinical trenches

Patients often seek care because they experience symptoms that negatively affect their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Health care providers must then elicit, measure, and interpret patient symptoms as part of their clinical evaluation. To assist with this goal and to help bridge the gap between patients and providers, investigators have developed and validated a wide range of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) across the breadth and depth of the human health and illness experience. These PROs, which measure any aspect of a patient’s biopsychosocial health and come directly from the patient, may help direct care and improve outcomes. When PROs are collected systematically, efficiently, and in the right place at the right time, they may enhance the patient–provider relationship by improving communication and facilitating shared decision making.1-3

Within gastroenterology and hepatology, PROs have been developed for a number of conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic idiopathic constipation, cirrhosis, eosinophilic esophagitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, among many other chronic diseases. IBS in particular is well suited for PRO measurement because it is symptom based and significantly impacts patients’ HRQOL and emotional health. Moreover, it is the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal condition and imparts a significant economic burden. In this article, we review the rationale for measuring IBS PROs in routine clinical practice and detail available measurement instruments.

Importance of IBS PROs in clinical practice

IBS is a functional GI disorder that is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits (i.e., diarrhea, constipation, or a mix of both). It has an estimated worldwide prevalence of 11%, and total costs are estimated at $30 billion annually in the United States alone.4 Because of the chronic relapsing nature of IBS, along with its impact on physical, mental, and social distress, it becomes important to accurately capture a patient’s illness experience with PROs. This is especially relevant to patients with IBS because we currently lack objective measurable biomarkers to assess their GI symptom burden. Instead, clinicians often are relegated to informal assessments of the severity of a patient’s symptoms, which ultimately guide their treatment recommendations: How many bowel movements have you had in the past week? Were your bowel movements hard or soft? How bad is your abdominal pain on a scale of 1 to 10? However, these traditional outcomes measured by health care providers often fail to capture other aspects of their health. For example, simply asking patients about the frequency and character of their stools will not provide any insight into how their symptoms impact their HRQOL and psychosocial health. An individual may report only two loose stools per day, but this may lead to substantial anxiety and negatively affect his or her performance at work. Similarly, the significance of the symptoms will vary from person to person; a patient with IBS who has five loose daily bowel movements may not be bothered by it, whereas another individual with three loose stools per day may feel that it severely hampers his or her daily activities. This is where PROs provide value because they provide a key component to understanding the true burden of IBS, and accounts for the HRQOL and psychosocial decrement engendered by the disease.

Although past literature has reported inconsistent benefits of using PROs in clinical practice,5 including that from our own work,6 there is a growing number of studies that have noted improved clinical outcomes through employing PROs.7-9 A compelling example is provided by Basch et al,7 who randomized patients receiving chemotherapy for metastatic cancer to either weekly symptom reporting using electronically delivered PRO instruments vs. usual care, which consisted of symptom reporting at the discretion of clinicians. Here, they found that the intervention group had higher HRQOL, were less likely to visit the emergency department, and remained on chemotherapy for a longer period of time. Interestingly, the benefits from PROs were greater among participants who lacked prior computer experience vs. those who were computer savvy. Basch et al9 also noted that the use of PROs extended survival by 5 months when compared with the control group (31.2 vs. 26.0 mo; P = .03). Longitudinal symptom reporting among IBS patients using PROs, when implemented well, may similarly lead to improved patient satisfaction, HRQOL, and clinical outcomes.

Measuring PROs in the clinical trenches

PROs generally are measured with patient questionnaires that collect data across several areas, including physical, social, and psychological functioning. Although PROs may enhance the patient–provider relationship and improve communication and shared decision making, we acknowledge that there are important barriers to its use in routine clinical practice.10 First, many providers (and their patients) may find use of PRO instruments burdensome, and it can be time consuming to collect PROs from patients and securely transmit the data into the electronic health record (EHR). This can make it untenable for use in busy practices. Second, many gastroenterologists have not received formal training in performing complete biopsychosocial evaluations with PROs, and it can be difficult to understand and act upon PRO scores. Third, there are many PROs to choose from and there is a lack of measurement standards across questionnaires. These challenges limit widespread use of PROs in clinical practice, and it is understandable why most providers instead opt for informal measurement of symptoms and function. Later, we detail strategies for overcoming the earlier-described challenges in employing PROs in everyday practice along with relevant IBS PRO instruments.

IBS–specific PRO instruments

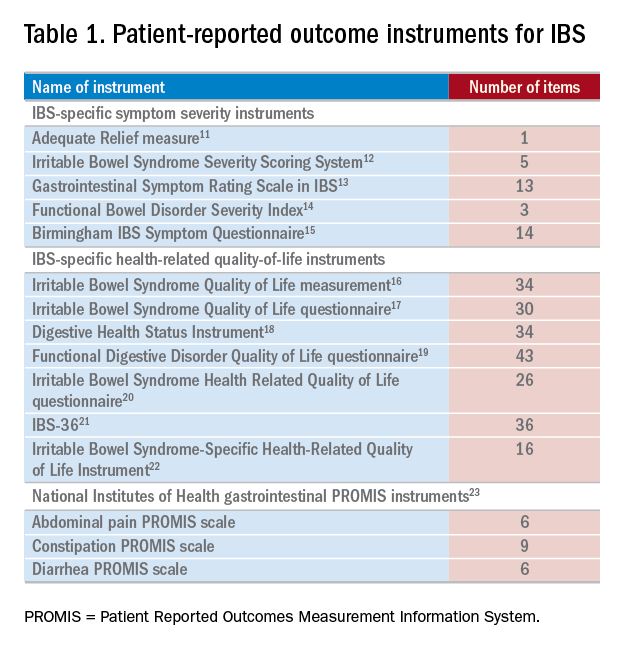

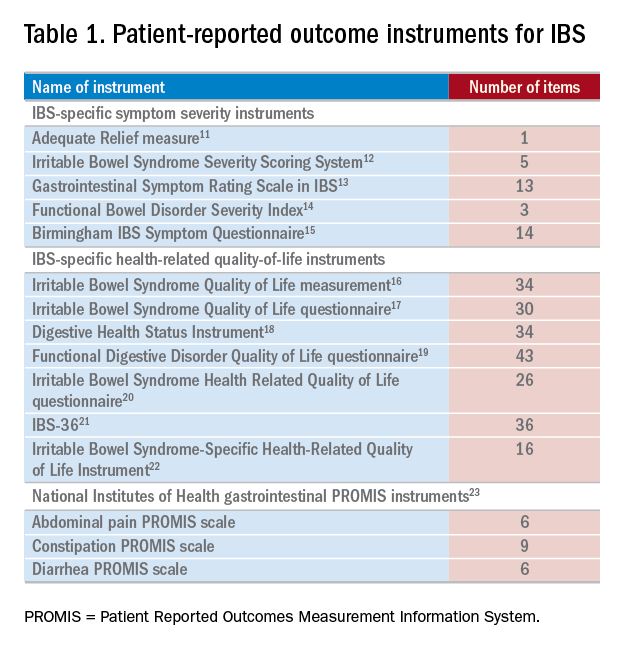

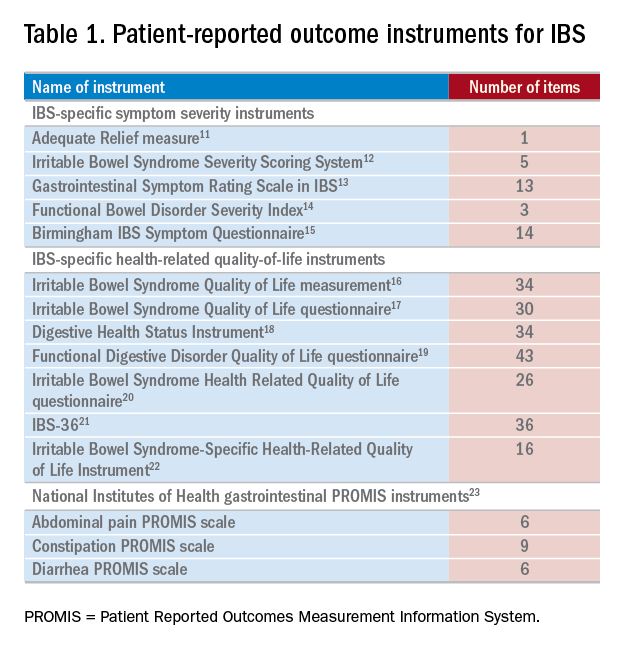

There have been several IBS-specific PRO instruments described in the literature, all of which vary in length, content, and amount of data supporting their validity (Table 1). Examples of IBS symptoms scales include the Adequate Relief measure, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in IBS, Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index, IBS Symptom Questionnaire, and Birmingham IBS Symptom Questionnaire.15,24 There are also IBS-specific HRQOL instruments, such as the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life measurement, Digestive Health Status Instrument, Functional Digestive Disorder Quality of Life questionnaire, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Health Related Quality of Life questionnaire, and IBS-36, among others.21,24

Bijkerk et al24 evaluated and compared the validity and appropriateness of both the symptom and QOL scales. Among the examined IBS symptom instruments, they found that the Adequate Relief question (Did you have adequate relief of IBS-related abdominal pain or discomfort?) is the best choice for assessing global symptomatology, and the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System is optimal for obtaining information on more specific symptoms.24 As for the QOL scales, the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life measurement, which comprises 34 items, is the preferred instrument for assessing changes in HRQOL because it is the most extensively validated.24 Bijkerk et al24 also concluded that although the studied instruments showed reasonable psychometric and methodologic qualities, the use of these instruments in daily clinical practice is debatable because the measures (save for the Adequate Relief question) are lengthy and/or cumbersome to use. Because these instruments may not be practical for use during everyday care, this leads to a discussion of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a novel approach to measuring PROs in the clinical trenches.

NIH PROMIS

Although there have been many efforts to implement PROs in routine clinical care, a recent confluence of scientific, regulatory, and political factors, coupled with technological advancements in PRO measurement techniques, have justified re-evaluation of the use of PROs in everyday practice. In response to the practical and technical challenges to employing PROs in the clinical trenches as described earlier, the NIH PROMIS (www.healthmeasures.net) was created in 2004 with the goal of developing and validating a toolbox of PROs that cover the breadth and depth of the human health and illness experience. The PROMIS initiative also was borne from the realization that patients are the ultimate consumers of health care and are the final judge on whether their health care needs are being addressed adequately.

By using modern psychometric techniques, such as item response theory and computerized adaptive testing, PROMIS offers state-of-the-art psychometrics, establishes common-language benchmarks for symptoms across conditions, and identifies clinical thresholds for action and meaningful clinical improvement or decline. PROMIS questionnaires, in light of accelerated EHR adoption in recent years, also are designed to be administered electronically and efficiently, allowing implementation in busy clinical settings. As of December 2017, these instruments can be administered and scored through EHRs such as Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) and Cerner (Cerner Corporation, North Kansas City, MO), the PROMIS iPad (Apple Inc, Cupertino, CA) App, and online data collection tools such as the Assessment Center (www.assessmentcenter.net) and REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN).25 An increasing number of health systems are making PROMIS measures available through their EHRs. For example, the University of Rochester Medical Center collects PROMIS scores for physical function, pain interference, and depression from more than 80% of their patients with in-clinic testing, and individual departments are able to further tailor their administered questionnaires.26

Gastrointestinal PROs measurement information system scales

Because of the extraordinary burden of illness from digestive diseases, the PROMIS consortium added a GI item bank, which our research group developed.23 By using the NIH PROMIS framework, we constructed and validated eight GI PROMIS symptom scales: abdominal pain, bloating/gas, constipation, diarrhea, bowel incontinence, dysphagia, heartburn/reflux, and nausea/vomiting.23 GI PROMIS was designed from the outset to not be a disease-targeted item bank (e.g., IBS-, cirrhosis-, or inflammatory bowel disease specific), but rather symptom targeted, measuring the physical symptoms of the GI tract, because it is more useful across the population as a whole. In Supplementary Figure 1 (at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.026), we include the abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea PROMIS scales because they form the cardinal symptoms of IBS.

GI PROMIS scales are readily accessible via the Assessment Center,25 and we also have made them freely available via MyGiHealth — an iOS (Apple Inc) and online app (go.mygihealth.io) endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association. The patient’s responses to the questionnaires are converted to percentile scores and compared with the general U.S. population, and then displayed in a symptom heat map. The app also allows users to track GI PROMIS scores longitudinally, empowering IBS patients (and any patient with GI symptoms for that matter) and their providers to see if they are objectively responding to prescribed therapies and potentially improving satisfaction and patient–provider communication.

Conclusions

IBS is a common, chronic, relapsing disease that often leads to physical, mental, and social distress. Without objective measurable biomarkers to assess IBS patients’ GI symptom burden, along with health care’s increased emphasis on patient-centered care, it becomes important to accurately capture a patient’s illness experience with PROs. A number of IBS symptom and QOL PRO instruments have been described in the literature, but most are beset by lengthy completion times and are impractical for use in everyday care. GI PROMIS, on the other hand, is a versatile and efficient instrument for collecting PRO data from not only IBS patients, but also all those who seek care in our GI clinics. Improvements in PRO and implementation science combined with technological advances have lessened the barriers to employing PROs in routine clinical care, and an increasing number of institutions are beginning to take up this challenge. In doing so and by seamlessly incorporating PROs in clinical practice, it facilitates placement of our patients’ voices at the forefront of their health care, changes how we monitor and manage patients, and, ultimately, may improve patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16:462-6).

References

1. Detmar S.B., Muller M.J., Schornagel J.H., et al. Role of health-related quality of life in palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1056-62.

2. Detmar S.B., Muller M.J., Schornagel J.H., et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:3027-34.

3. Neumann M., Edelhauser F., Kreps G.L., et al. Can patient-provider interaction increase the effectiveness of medical treatment or even substitute it? An exploration on why and how to study the specific effect of the provider. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:307-14.

4. Lembo A.J. The clinical and economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome. Pract Gastroenterol. 2007;31:3-9.

5. Valderas J.M., Kotzeva A., Espallargues M., et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:179-93.

6. Almario C.V., Chey W.D., Khanna D., et al. Impact of National Institutes of Health gastrointestinal PROMIS measures in clinical practice: results of a multicenter controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1546-56.

7. Basch E., Deal A.M., Kris M.G., et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557-65.

8. Kotronoulas G., Kearney N., Maguire R., et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1480-501.

9. Basch E., Deal A.M., Dueck A.C., et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197-8.

10. Spiegel B.M. Patient-reported outcomes in gastroenterology: clinical and research applications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:137-48.

11. Mangel A.W., Hahn B.A., Heath A.T., et al. Adequate relief as an endpoint in clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:76-81.

12. Francis C.Y., Morris J., Whorwell P.J. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402.

13. Wiklund I.K., Fullerton S., Hawkey C.J., et al. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: development and validation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:947-54.

14. Drossman D.A., Li Z., Toner B.B., et al. Functional bowel disorders. A multicenter comparison of health status and development of illness severity index. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:986-95.

15. Roalfe A.K., Roberts L.M., Wilson S. Evaluation of the Birmingham IBS symptom questionnaire. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:30.

16. Patrick D.L., Drossman D.A., Frederick I.O., et al. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400-11.

17. Hahn B.A., Kirchdoerfer L.J., Fullerton S., et al. Evaluation of a new quality of life questionnaire for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:547-52.

18. Shaw M., Talley N.J., Adlis S., et al. Development of a digestive health status instrument: tests of scaling assumptions, structure and reliability in a primary care population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1067-78.

19. Chassany O., Marquis P., Scherrer B., et al. Validation of a specific quality of life questionnaire for functional digestive disorders. Gut. 1999;44:527-33.

20. Wong E., Guyatt G.H., Cook D.J., et al. Development of a questionnaire to measure quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;583:50-6.

21. Groll D., Vanner S.J., Depew W.T., et al. The IBS-36: a new quality of life measure for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:962-71.

22. Lee E.H., Kwon O., Hahm K.B., et al. Irritable bowel syndrome-specific health-related quality of life instrument: development and psychometric evaluation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:22.

23. Spiegel B.M., Hays R.D., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

24. Bijkerk C.J., de Wit N.J., Muris J.W., et al. Outcome measures in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison of psychometric and methodological characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:122-7.

25. HealthMeasures. Data collection tools. 2017. Available from http://www.healthmeasures.net/resource-center/data-collection-tools. Accessed August 20, 2017.

26. Baumhauer J.F. Patient-reported outcomes – are they living up to their potential?. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:6-9.

Dr. Almario is assistant professor-in-residence of medicine and public health, division of digestive and liver diseases, Dr. Spiegel professor-in-residence of medicine and public health, division of digestive and liver diseases, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education, Los Angeles. Dr. Spiegel is a principal at My Total Health, which operates and maintains MyGiHealth; Dr. Almario has a stock option grant in My Total Health.

Patients often seek care because they experience symptoms that negatively affect their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Health care providers must then elicit, measure, and interpret patient symptoms as part of their clinical evaluation. To assist with this goal and to help bridge the gap between patients and providers, investigators have developed and validated a wide range of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) across the breadth and depth of the human health and illness experience. These PROs, which measure any aspect of a patient’s biopsychosocial health and come directly from the patient, may help direct care and improve outcomes. When PROs are collected systematically, efficiently, and in the right place at the right time, they may enhance the patient–provider relationship by improving communication and facilitating shared decision making.1-3

Within gastroenterology and hepatology, PROs have been developed for a number of conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic idiopathic constipation, cirrhosis, eosinophilic esophagitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, among many other chronic diseases. IBS in particular is well suited for PRO measurement because it is symptom based and significantly impacts patients’ HRQOL and emotional health. Moreover, it is the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal condition and imparts a significant economic burden. In this article, we review the rationale for measuring IBS PROs in routine clinical practice and detail available measurement instruments.

Importance of IBS PROs in clinical practice

IBS is a functional GI disorder that is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits (i.e., diarrhea, constipation, or a mix of both). It has an estimated worldwide prevalence of 11%, and total costs are estimated at $30 billion annually in the United States alone.4 Because of the chronic relapsing nature of IBS, along with its impact on physical, mental, and social distress, it becomes important to accurately capture a patient’s illness experience with PROs. This is especially relevant to patients with IBS because we currently lack objective measurable biomarkers to assess their GI symptom burden. Instead, clinicians often are relegated to informal assessments of the severity of a patient’s symptoms, which ultimately guide their treatment recommendations: How many bowel movements have you had in the past week? Were your bowel movements hard or soft? How bad is your abdominal pain on a scale of 1 to 10? However, these traditional outcomes measured by health care providers often fail to capture other aspects of their health. For example, simply asking patients about the frequency and character of their stools will not provide any insight into how their symptoms impact their HRQOL and psychosocial health. An individual may report only two loose stools per day, but this may lead to substantial anxiety and negatively affect his or her performance at work. Similarly, the significance of the symptoms will vary from person to person; a patient with IBS who has five loose daily bowel movements may not be bothered by it, whereas another individual with three loose stools per day may feel that it severely hampers his or her daily activities. This is where PROs provide value because they provide a key component to understanding the true burden of IBS, and accounts for the HRQOL and psychosocial decrement engendered by the disease.

Although past literature has reported inconsistent benefits of using PROs in clinical practice,5 including that from our own work,6 there is a growing number of studies that have noted improved clinical outcomes through employing PROs.7-9 A compelling example is provided by Basch et al,7 who randomized patients receiving chemotherapy for metastatic cancer to either weekly symptom reporting using electronically delivered PRO instruments vs. usual care, which consisted of symptom reporting at the discretion of clinicians. Here, they found that the intervention group had higher HRQOL, were less likely to visit the emergency department, and remained on chemotherapy for a longer period of time. Interestingly, the benefits from PROs were greater among participants who lacked prior computer experience vs. those who were computer savvy. Basch et al9 also noted that the use of PROs extended survival by 5 months when compared with the control group (31.2 vs. 26.0 mo; P = .03). Longitudinal symptom reporting among IBS patients using PROs, when implemented well, may similarly lead to improved patient satisfaction, HRQOL, and clinical outcomes.

Measuring PROs in the clinical trenches

PROs generally are measured with patient questionnaires that collect data across several areas, including physical, social, and psychological functioning. Although PROs may enhance the patient–provider relationship and improve communication and shared decision making, we acknowledge that there are important barriers to its use in routine clinical practice.10 First, many providers (and their patients) may find use of PRO instruments burdensome, and it can be time consuming to collect PROs from patients and securely transmit the data into the electronic health record (EHR). This can make it untenable for use in busy practices. Second, many gastroenterologists have not received formal training in performing complete biopsychosocial evaluations with PROs, and it can be difficult to understand and act upon PRO scores. Third, there are many PROs to choose from and there is a lack of measurement standards across questionnaires. These challenges limit widespread use of PROs in clinical practice, and it is understandable why most providers instead opt for informal measurement of symptoms and function. Later, we detail strategies for overcoming the earlier-described challenges in employing PROs in everyday practice along with relevant IBS PRO instruments.

IBS–specific PRO instruments

There have been several IBS-specific PRO instruments described in the literature, all of which vary in length, content, and amount of data supporting their validity (Table 1). Examples of IBS symptoms scales include the Adequate Relief measure, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in IBS, Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index, IBS Symptom Questionnaire, and Birmingham IBS Symptom Questionnaire.15,24 There are also IBS-specific HRQOL instruments, such as the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life measurement, Digestive Health Status Instrument, Functional Digestive Disorder Quality of Life questionnaire, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Health Related Quality of Life questionnaire, and IBS-36, among others.21,24

Bijkerk et al24 evaluated and compared the validity and appropriateness of both the symptom and QOL scales. Among the examined IBS symptom instruments, they found that the Adequate Relief question (Did you have adequate relief of IBS-related abdominal pain or discomfort?) is the best choice for assessing global symptomatology, and the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System is optimal for obtaining information on more specific symptoms.24 As for the QOL scales, the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life measurement, which comprises 34 items, is the preferred instrument for assessing changes in HRQOL because it is the most extensively validated.24 Bijkerk et al24 also concluded that although the studied instruments showed reasonable psychometric and methodologic qualities, the use of these instruments in daily clinical practice is debatable because the measures (save for the Adequate Relief question) are lengthy and/or cumbersome to use. Because these instruments may not be practical for use during everyday care, this leads to a discussion of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a novel approach to measuring PROs in the clinical trenches.

NIH PROMIS

Although there have been many efforts to implement PROs in routine clinical care, a recent confluence of scientific, regulatory, and political factors, coupled with technological advancements in PRO measurement techniques, have justified re-evaluation of the use of PROs in everyday practice. In response to the practical and technical challenges to employing PROs in the clinical trenches as described earlier, the NIH PROMIS (www.healthmeasures.net) was created in 2004 with the goal of developing and validating a toolbox of PROs that cover the breadth and depth of the human health and illness experience. The PROMIS initiative also was borne from the realization that patients are the ultimate consumers of health care and are the final judge on whether their health care needs are being addressed adequately.

By using modern psychometric techniques, such as item response theory and computerized adaptive testing, PROMIS offers state-of-the-art psychometrics, establishes common-language benchmarks for symptoms across conditions, and identifies clinical thresholds for action and meaningful clinical improvement or decline. PROMIS questionnaires, in light of accelerated EHR adoption in recent years, also are designed to be administered electronically and efficiently, allowing implementation in busy clinical settings. As of December 2017, these instruments can be administered and scored through EHRs such as Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) and Cerner (Cerner Corporation, North Kansas City, MO), the PROMIS iPad (Apple Inc, Cupertino, CA) App, and online data collection tools such as the Assessment Center (www.assessmentcenter.net) and REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN).25 An increasing number of health systems are making PROMIS measures available through their EHRs. For example, the University of Rochester Medical Center collects PROMIS scores for physical function, pain interference, and depression from more than 80% of their patients with in-clinic testing, and individual departments are able to further tailor their administered questionnaires.26

Gastrointestinal PROs measurement information system scales

Because of the extraordinary burden of illness from digestive diseases, the PROMIS consortium added a GI item bank, which our research group developed.23 By using the NIH PROMIS framework, we constructed and validated eight GI PROMIS symptom scales: abdominal pain, bloating/gas, constipation, diarrhea, bowel incontinence, dysphagia, heartburn/reflux, and nausea/vomiting.23 GI PROMIS was designed from the outset to not be a disease-targeted item bank (e.g., IBS-, cirrhosis-, or inflammatory bowel disease specific), but rather symptom targeted, measuring the physical symptoms of the GI tract, because it is more useful across the population as a whole. In Supplementary Figure 1 (at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.026), we include the abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea PROMIS scales because they form the cardinal symptoms of IBS.

GI PROMIS scales are readily accessible via the Assessment Center,25 and we also have made them freely available via MyGiHealth — an iOS (Apple Inc) and online app (go.mygihealth.io) endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association. The patient’s responses to the questionnaires are converted to percentile scores and compared with the general U.S. population, and then displayed in a symptom heat map. The app also allows users to track GI PROMIS scores longitudinally, empowering IBS patients (and any patient with GI symptoms for that matter) and their providers to see if they are objectively responding to prescribed therapies and potentially improving satisfaction and patient–provider communication.

Conclusions

IBS is a common, chronic, relapsing disease that often leads to physical, mental, and social distress. Without objective measurable biomarkers to assess IBS patients’ GI symptom burden, along with health care’s increased emphasis on patient-centered care, it becomes important to accurately capture a patient’s illness experience with PROs. A number of IBS symptom and QOL PRO instruments have been described in the literature, but most are beset by lengthy completion times and are impractical for use in everyday care. GI PROMIS, on the other hand, is a versatile and efficient instrument for collecting PRO data from not only IBS patients, but also all those who seek care in our GI clinics. Improvements in PRO and implementation science combined with technological advances have lessened the barriers to employing PROs in routine clinical care, and an increasing number of institutions are beginning to take up this challenge. In doing so and by seamlessly incorporating PROs in clinical practice, it facilitates placement of our patients’ voices at the forefront of their health care, changes how we monitor and manage patients, and, ultimately, may improve patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16:462-6).

References

1. Detmar S.B., Muller M.J., Schornagel J.H., et al. Role of health-related quality of life in palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1056-62.

2. Detmar S.B., Muller M.J., Schornagel J.H., et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:3027-34.

3. Neumann M., Edelhauser F., Kreps G.L., et al. Can patient-provider interaction increase the effectiveness of medical treatment or even substitute it? An exploration on why and how to study the specific effect of the provider. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:307-14.

4. Lembo A.J. The clinical and economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome. Pract Gastroenterol. 2007;31:3-9.

5. Valderas J.M., Kotzeva A., Espallargues M., et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:179-93.

6. Almario C.V., Chey W.D., Khanna D., et al. Impact of National Institutes of Health gastrointestinal PROMIS measures in clinical practice: results of a multicenter controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1546-56.

7. Basch E., Deal A.M., Kris M.G., et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557-65.

8. Kotronoulas G., Kearney N., Maguire R., et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1480-501.

9. Basch E., Deal A.M., Dueck A.C., et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197-8.

10. Spiegel B.M. Patient-reported outcomes in gastroenterology: clinical and research applications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:137-48.

11. Mangel A.W., Hahn B.A., Heath A.T., et al. Adequate relief as an endpoint in clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:76-81.

12. Francis C.Y., Morris J., Whorwell P.J. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402.

13. Wiklund I.K., Fullerton S., Hawkey C.J., et al. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: development and validation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:947-54.

14. Drossman D.A., Li Z., Toner B.B., et al. Functional bowel disorders. A multicenter comparison of health status and development of illness severity index. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:986-95.

15. Roalfe A.K., Roberts L.M., Wilson S. Evaluation of the Birmingham IBS symptom questionnaire. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:30.

16. Patrick D.L., Drossman D.A., Frederick I.O., et al. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400-11.

17. Hahn B.A., Kirchdoerfer L.J., Fullerton S., et al. Evaluation of a new quality of life questionnaire for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:547-52.

18. Shaw M., Talley N.J., Adlis S., et al. Development of a digestive health status instrument: tests of scaling assumptions, structure and reliability in a primary care population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1067-78.

19. Chassany O., Marquis P., Scherrer B., et al. Validation of a specific quality of life questionnaire for functional digestive disorders. Gut. 1999;44:527-33.

20. Wong E., Guyatt G.H., Cook D.J., et al. Development of a questionnaire to measure quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;583:50-6.

21. Groll D., Vanner S.J., Depew W.T., et al. The IBS-36: a new quality of life measure for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:962-71.

22. Lee E.H., Kwon O., Hahm K.B., et al. Irritable bowel syndrome-specific health-related quality of life instrument: development and psychometric evaluation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:22.

23. Spiegel B.M., Hays R.D., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

24. Bijkerk C.J., de Wit N.J., Muris J.W., et al. Outcome measures in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison of psychometric and methodological characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:122-7.

25. HealthMeasures. Data collection tools. 2017. Available from http://www.healthmeasures.net/resource-center/data-collection-tools. Accessed August 20, 2017.

26. Baumhauer J.F. Patient-reported outcomes – are they living up to their potential?. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:6-9.

Dr. Almario is assistant professor-in-residence of medicine and public health, division of digestive and liver diseases, Dr. Spiegel professor-in-residence of medicine and public health, division of digestive and liver diseases, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education, Los Angeles. Dr. Spiegel is a principal at My Total Health, which operates and maintains MyGiHealth; Dr. Almario has a stock option grant in My Total Health.

Patients often seek care because they experience symptoms that negatively affect their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Health care providers must then elicit, measure, and interpret patient symptoms as part of their clinical evaluation. To assist with this goal and to help bridge the gap between patients and providers, investigators have developed and validated a wide range of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) across the breadth and depth of the human health and illness experience. These PROs, which measure any aspect of a patient’s biopsychosocial health and come directly from the patient, may help direct care and improve outcomes. When PROs are collected systematically, efficiently, and in the right place at the right time, they may enhance the patient–provider relationship by improving communication and facilitating shared decision making.1-3

Within gastroenterology and hepatology, PROs have been developed for a number of conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic idiopathic constipation, cirrhosis, eosinophilic esophagitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, among many other chronic diseases. IBS in particular is well suited for PRO measurement because it is symptom based and significantly impacts patients’ HRQOL and emotional health. Moreover, it is the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal condition and imparts a significant economic burden. In this article, we review the rationale for measuring IBS PROs in routine clinical practice and detail available measurement instruments.

Importance of IBS PROs in clinical practice

IBS is a functional GI disorder that is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits (i.e., diarrhea, constipation, or a mix of both). It has an estimated worldwide prevalence of 11%, and total costs are estimated at $30 billion annually in the United States alone.4 Because of the chronic relapsing nature of IBS, along with its impact on physical, mental, and social distress, it becomes important to accurately capture a patient’s illness experience with PROs. This is especially relevant to patients with IBS because we currently lack objective measurable biomarkers to assess their GI symptom burden. Instead, clinicians often are relegated to informal assessments of the severity of a patient’s symptoms, which ultimately guide their treatment recommendations: How many bowel movements have you had in the past week? Were your bowel movements hard or soft? How bad is your abdominal pain on a scale of 1 to 10? However, these traditional outcomes measured by health care providers often fail to capture other aspects of their health. For example, simply asking patients about the frequency and character of their stools will not provide any insight into how their symptoms impact their HRQOL and psychosocial health. An individual may report only two loose stools per day, but this may lead to substantial anxiety and negatively affect his or her performance at work. Similarly, the significance of the symptoms will vary from person to person; a patient with IBS who has five loose daily bowel movements may not be bothered by it, whereas another individual with three loose stools per day may feel that it severely hampers his or her daily activities. This is where PROs provide value because they provide a key component to understanding the true burden of IBS, and accounts for the HRQOL and psychosocial decrement engendered by the disease.

Although past literature has reported inconsistent benefits of using PROs in clinical practice,5 including that from our own work,6 there is a growing number of studies that have noted improved clinical outcomes through employing PROs.7-9 A compelling example is provided by Basch et al,7 who randomized patients receiving chemotherapy for metastatic cancer to either weekly symptom reporting using electronically delivered PRO instruments vs. usual care, which consisted of symptom reporting at the discretion of clinicians. Here, they found that the intervention group had higher HRQOL, were less likely to visit the emergency department, and remained on chemotherapy for a longer period of time. Interestingly, the benefits from PROs were greater among participants who lacked prior computer experience vs. those who were computer savvy. Basch et al9 also noted that the use of PROs extended survival by 5 months when compared with the control group (31.2 vs. 26.0 mo; P = .03). Longitudinal symptom reporting among IBS patients using PROs, when implemented well, may similarly lead to improved patient satisfaction, HRQOL, and clinical outcomes.

Measuring PROs in the clinical trenches

PROs generally are measured with patient questionnaires that collect data across several areas, including physical, social, and psychological functioning. Although PROs may enhance the patient–provider relationship and improve communication and shared decision making, we acknowledge that there are important barriers to its use in routine clinical practice.10 First, many providers (and their patients) may find use of PRO instruments burdensome, and it can be time consuming to collect PROs from patients and securely transmit the data into the electronic health record (EHR). This can make it untenable for use in busy practices. Second, many gastroenterologists have not received formal training in performing complete biopsychosocial evaluations with PROs, and it can be difficult to understand and act upon PRO scores. Third, there are many PROs to choose from and there is a lack of measurement standards across questionnaires. These challenges limit widespread use of PROs in clinical practice, and it is understandable why most providers instead opt for informal measurement of symptoms and function. Later, we detail strategies for overcoming the earlier-described challenges in employing PROs in everyday practice along with relevant IBS PRO instruments.

IBS–specific PRO instruments

There have been several IBS-specific PRO instruments described in the literature, all of which vary in length, content, and amount of data supporting their validity (Table 1). Examples of IBS symptoms scales include the Adequate Relief measure, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in IBS, Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index, IBS Symptom Questionnaire, and Birmingham IBS Symptom Questionnaire.15,24 There are also IBS-specific HRQOL instruments, such as the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life measurement, Digestive Health Status Instrument, Functional Digestive Disorder Quality of Life questionnaire, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Health Related Quality of Life questionnaire, and IBS-36, among others.21,24

Bijkerk et al24 evaluated and compared the validity and appropriateness of both the symptom and QOL scales. Among the examined IBS symptom instruments, they found that the Adequate Relief question (Did you have adequate relief of IBS-related abdominal pain or discomfort?) is the best choice for assessing global symptomatology, and the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Severity Scoring System is optimal for obtaining information on more specific symptoms.24 As for the QOL scales, the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life measurement, which comprises 34 items, is the preferred instrument for assessing changes in HRQOL because it is the most extensively validated.24 Bijkerk et al24 also concluded that although the studied instruments showed reasonable psychometric and methodologic qualities, the use of these instruments in daily clinical practice is debatable because the measures (save for the Adequate Relief question) are lengthy and/or cumbersome to use. Because these instruments may not be practical for use during everyday care, this leads to a discussion of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a novel approach to measuring PROs in the clinical trenches.

NIH PROMIS

Although there have been many efforts to implement PROs in routine clinical care, a recent confluence of scientific, regulatory, and political factors, coupled with technological advancements in PRO measurement techniques, have justified re-evaluation of the use of PROs in everyday practice. In response to the practical and technical challenges to employing PROs in the clinical trenches as described earlier, the NIH PROMIS (www.healthmeasures.net) was created in 2004 with the goal of developing and validating a toolbox of PROs that cover the breadth and depth of the human health and illness experience. The PROMIS initiative also was borne from the realization that patients are the ultimate consumers of health care and are the final judge on whether their health care needs are being addressed adequately.

By using modern psychometric techniques, such as item response theory and computerized adaptive testing, PROMIS offers state-of-the-art psychometrics, establishes common-language benchmarks for symptoms across conditions, and identifies clinical thresholds for action and meaningful clinical improvement or decline. PROMIS questionnaires, in light of accelerated EHR adoption in recent years, also are designed to be administered electronically and efficiently, allowing implementation in busy clinical settings. As of December 2017, these instruments can be administered and scored through EHRs such as Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) and Cerner (Cerner Corporation, North Kansas City, MO), the PROMIS iPad (Apple Inc, Cupertino, CA) App, and online data collection tools such as the Assessment Center (www.assessmentcenter.net) and REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN).25 An increasing number of health systems are making PROMIS measures available through their EHRs. For example, the University of Rochester Medical Center collects PROMIS scores for physical function, pain interference, and depression from more than 80% of their patients with in-clinic testing, and individual departments are able to further tailor their administered questionnaires.26

Gastrointestinal PROs measurement information system scales

Because of the extraordinary burden of illness from digestive diseases, the PROMIS consortium added a GI item bank, which our research group developed.23 By using the NIH PROMIS framework, we constructed and validated eight GI PROMIS symptom scales: abdominal pain, bloating/gas, constipation, diarrhea, bowel incontinence, dysphagia, heartburn/reflux, and nausea/vomiting.23 GI PROMIS was designed from the outset to not be a disease-targeted item bank (e.g., IBS-, cirrhosis-, or inflammatory bowel disease specific), but rather symptom targeted, measuring the physical symptoms of the GI tract, because it is more useful across the population as a whole. In Supplementary Figure 1 (at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.026), we include the abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea PROMIS scales because they form the cardinal symptoms of IBS.

GI PROMIS scales are readily accessible via the Assessment Center,25 and we also have made them freely available via MyGiHealth — an iOS (Apple Inc) and online app (go.mygihealth.io) endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association. The patient’s responses to the questionnaires are converted to percentile scores and compared with the general U.S. population, and then displayed in a symptom heat map. The app also allows users to track GI PROMIS scores longitudinally, empowering IBS patients (and any patient with GI symptoms for that matter) and their providers to see if they are objectively responding to prescribed therapies and potentially improving satisfaction and patient–provider communication.

Conclusions

IBS is a common, chronic, relapsing disease that often leads to physical, mental, and social distress. Without objective measurable biomarkers to assess IBS patients’ GI symptom burden, along with health care’s increased emphasis on patient-centered care, it becomes important to accurately capture a patient’s illness experience with PROs. A number of IBS symptom and QOL PRO instruments have been described in the literature, but most are beset by lengthy completion times and are impractical for use in everyday care. GI PROMIS, on the other hand, is a versatile and efficient instrument for collecting PRO data from not only IBS patients, but also all those who seek care in our GI clinics. Improvements in PRO and implementation science combined with technological advances have lessened the barriers to employing PROs in routine clinical care, and an increasing number of institutions are beginning to take up this challenge. In doing so and by seamlessly incorporating PROs in clinical practice, it facilitates placement of our patients’ voices at the forefront of their health care, changes how we monitor and manage patients, and, ultimately, may improve patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16:462-6).

References

1. Detmar S.B., Muller M.J., Schornagel J.H., et al. Role of health-related quality of life in palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1056-62.

2. Detmar S.B., Muller M.J., Schornagel J.H., et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:3027-34.

3. Neumann M., Edelhauser F., Kreps G.L., et al. Can patient-provider interaction increase the effectiveness of medical treatment or even substitute it? An exploration on why and how to study the specific effect of the provider. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:307-14.

4. Lembo A.J. The clinical and economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome. Pract Gastroenterol. 2007;31:3-9.

5. Valderas J.M., Kotzeva A., Espallargues M., et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:179-93.

6. Almario C.V., Chey W.D., Khanna D., et al. Impact of National Institutes of Health gastrointestinal PROMIS measures in clinical practice: results of a multicenter controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1546-56.

7. Basch E., Deal A.M., Kris M.G., et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557-65.

8. Kotronoulas G., Kearney N., Maguire R., et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1480-501.

9. Basch E., Deal A.M., Dueck A.C., et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197-8.

10. Spiegel B.M. Patient-reported outcomes in gastroenterology: clinical and research applications. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:137-48.

11. Mangel A.W., Hahn B.A., Heath A.T., et al. Adequate relief as an endpoint in clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:76-81.

12. Francis C.Y., Morris J., Whorwell P.J. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402.

13. Wiklund I.K., Fullerton S., Hawkey C.J., et al. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: development and validation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:947-54.

14. Drossman D.A., Li Z., Toner B.B., et al. Functional bowel disorders. A multicenter comparison of health status and development of illness severity index. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:986-95.

15. Roalfe A.K., Roberts L.M., Wilson S. Evaluation of the Birmingham IBS symptom questionnaire. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:30.

16. Patrick D.L., Drossman D.A., Frederick I.O., et al. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400-11.

17. Hahn B.A., Kirchdoerfer L.J., Fullerton S., et al. Evaluation of a new quality of life questionnaire for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:547-52.

18. Shaw M., Talley N.J., Adlis S., et al. Development of a digestive health status instrument: tests of scaling assumptions, structure and reliability in a primary care population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1067-78.

19. Chassany O., Marquis P., Scherrer B., et al. Validation of a specific quality of life questionnaire for functional digestive disorders. Gut. 1999;44:527-33.

20. Wong E., Guyatt G.H., Cook D.J., et al. Development of a questionnaire to measure quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;583:50-6.

21. Groll D., Vanner S.J., Depew W.T., et al. The IBS-36: a new quality of life measure for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:962-71.

22. Lee E.H., Kwon O., Hahm K.B., et al. Irritable bowel syndrome-specific health-related quality of life instrument: development and psychometric evaluation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:22.

23. Spiegel B.M., Hays R.D., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

24. Bijkerk C.J., de Wit N.J., Muris J.W., et al. Outcome measures in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison of psychometric and methodological characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:122-7.

25. HealthMeasures. Data collection tools. 2017. Available from http://www.healthmeasures.net/resource-center/data-collection-tools. Accessed August 20, 2017.

26. Baumhauer J.F. Patient-reported outcomes – are they living up to their potential?. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:6-9.

Dr. Almario is assistant professor-in-residence of medicine and public health, division of digestive and liver diseases, Dr. Spiegel professor-in-residence of medicine and public health, division of digestive and liver diseases, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; Cedars-Sinai Center for Outcomes Research and Education, Los Angeles. Dr. Spiegel is a principal at My Total Health, which operates and maintains MyGiHealth; Dr. Almario has a stock option grant in My Total Health.

Mayo Clinic announces new president and CEO: Gianrico Farrugia, MD

The Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees has announced that Gianrico Farrugia, MD, vice president and CEO of Mayo Clinic Florida, will take over as president and CEO of Mayo Clinic at the end of the year. AGA congratulates Dr. Farrugia on this accomplishment.

Here’s three reasons why AGA is excited by this news:

1. Dr. Farrugia is an accomplished GI investigator. Dr. Farrugia runs an NIH-funded translational laboratory focused on disorders of GI motility. The aim of Dr. Farrugia’s work is to understand at a cellular, subcellular and molecular level how the normal functions of the GI tract determine the defects that result in diseases such as diabetic gastroparesis, slow transit constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which will ultimately lead to new strategies to treat these diseases by developing targeted disease-modifying agents.

2. Dr. Farrugia is an alumnus of the AGA Research Foundation Research Scholar Award program. Dr. Farrugia received his Research Scholar Award in 1994 for his project titled “Jejunal Smooth Muscle Ion Channel Regulation in Health and Disease.”

3. Dr. Farrugia has given back to AGA both with his time – serving on the AGA Nominating Committee, AGA Institute Council, and Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology editorial board – and by contributing, with his wife Geraldine Farrugia, to the AGA Research Foundation at the highest level as an AGA Legacy Society member.

Join AGA members in congratulating Dr. Farrugia in the AGA Community, community.gastro.org.

The Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees has announced that Gianrico Farrugia, MD, vice president and CEO of Mayo Clinic Florida, will take over as president and CEO of Mayo Clinic at the end of the year. AGA congratulates Dr. Farrugia on this accomplishment.

Here’s three reasons why AGA is excited by this news:

1. Dr. Farrugia is an accomplished GI investigator. Dr. Farrugia runs an NIH-funded translational laboratory focused on disorders of GI motility. The aim of Dr. Farrugia’s work is to understand at a cellular, subcellular and molecular level how the normal functions of the GI tract determine the defects that result in diseases such as diabetic gastroparesis, slow transit constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which will ultimately lead to new strategies to treat these diseases by developing targeted disease-modifying agents.

2. Dr. Farrugia is an alumnus of the AGA Research Foundation Research Scholar Award program. Dr. Farrugia received his Research Scholar Award in 1994 for his project titled “Jejunal Smooth Muscle Ion Channel Regulation in Health and Disease.”

3. Dr. Farrugia has given back to AGA both with his time – serving on the AGA Nominating Committee, AGA Institute Council, and Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology editorial board – and by contributing, with his wife Geraldine Farrugia, to the AGA Research Foundation at the highest level as an AGA Legacy Society member.

Join AGA members in congratulating Dr. Farrugia in the AGA Community, community.gastro.org.

The Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees has announced that Gianrico Farrugia, MD, vice president and CEO of Mayo Clinic Florida, will take over as president and CEO of Mayo Clinic at the end of the year. AGA congratulates Dr. Farrugia on this accomplishment.

Here’s three reasons why AGA is excited by this news:

1. Dr. Farrugia is an accomplished GI investigator. Dr. Farrugia runs an NIH-funded translational laboratory focused on disorders of GI motility. The aim of Dr. Farrugia’s work is to understand at a cellular, subcellular and molecular level how the normal functions of the GI tract determine the defects that result in diseases such as diabetic gastroparesis, slow transit constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which will ultimately lead to new strategies to treat these diseases by developing targeted disease-modifying agents.

2. Dr. Farrugia is an alumnus of the AGA Research Foundation Research Scholar Award program. Dr. Farrugia received his Research Scholar Award in 1994 for his project titled “Jejunal Smooth Muscle Ion Channel Regulation in Health and Disease.”

3. Dr. Farrugia has given back to AGA both with his time – serving on the AGA Nominating Committee, AGA Institute Council, and Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology editorial board – and by contributing, with his wife Geraldine Farrugia, to the AGA Research Foundation at the highest level as an AGA Legacy Society member.

Join AGA members in congratulating Dr. Farrugia in the AGA Community, community.gastro.org.

Rising microbiome investigator: Ting-Chin David Shen, MD, PhD

We spoke with Dr. Shen, instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the recipient of the AGA Research Foundation’s 2016 Microbiome Junior Investigator Award, to learn about his passion for gut microbiome research.

How would you sum up your research in one sentence?

My research examines the metabolic interactions between the gut microbiota and the mammalian host, with a particular emphasis on amino acid metabolism and nitrogen flux via the bacterial enzyme urease.

What impact do you hope your research will have on patients?

My hope is that by better understanding the biological mechanisms by which the gut microbiota impacts host metabolism, we can modulate its effects to treat a variety of conditions and diseases including hepatic encephalopathy, inborn errors of metabolism, obesity, malnutrition, etc.

What inspired you to focus your research career on the gut microbiome?

My clinical experience as a gastroenterologist inspired my interest in metabolic and nutritional research. When I learned of the impact that the gut microbiota has on host metabolism, it created an entirely different perspective for me in terms of thinking about how to treat metabolic and nutritional disorders. There are tremendous opportunities in modifying our gut microbiota in concert with dietary interventions in order to modulate our metabolism.

What recent publication from your lab best represents your work, if anyone wants to learn more?

The following work examined how the use of a defined bacterial consortium without urease activity can reduce colonic ammonia level upon inoculation into the gut and ameliorate morbidity and mortality in a murine model of liver disease: Shen T.D., Albenberg L.A., Bittinger K., et al, Engineering the gut microbiota to treat hyperammonemia. J Clin Invest. 2015 Jul 1;125(7):2841-50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4563680/.

We spoke with Dr. Shen, instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the recipient of the AGA Research Foundation’s 2016 Microbiome Junior Investigator Award, to learn about his passion for gut microbiome research.

How would you sum up your research in one sentence?

My research examines the metabolic interactions between the gut microbiota and the mammalian host, with a particular emphasis on amino acid metabolism and nitrogen flux via the bacterial enzyme urease.

What impact do you hope your research will have on patients?

My hope is that by better understanding the biological mechanisms by which the gut microbiota impacts host metabolism, we can modulate its effects to treat a variety of conditions and diseases including hepatic encephalopathy, inborn errors of metabolism, obesity, malnutrition, etc.

What inspired you to focus your research career on the gut microbiome?

My clinical experience as a gastroenterologist inspired my interest in metabolic and nutritional research. When I learned of the impact that the gut microbiota has on host metabolism, it created an entirely different perspective for me in terms of thinking about how to treat metabolic and nutritional disorders. There are tremendous opportunities in modifying our gut microbiota in concert with dietary interventions in order to modulate our metabolism.

What recent publication from your lab best represents your work, if anyone wants to learn more?