User login

Appraising the Evidence Supporting Choosing Wisely® Recommendations

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

Guideline Appraisal

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

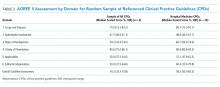

A total of 320 recommendations were considered in our analysis, including 10 published across the 2 hospital medicine lists. When limited to the highest quality citation for each of the recommendations, 225 (70.3%) cited CPGs, whereas 71 (22.2%) cited primary research articles (Table 1). Specifically, 29 (9.1%) cited systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 28 (8.8%) cited observational studies, and 13 (4.1%) cited RCTs. One recommendation (0.3%) cited a case series as its highest level of evidence, 7 (2.2%) cited review articles, 7 (2.2%) cited editorials or opinion pieces, and 10 (3.1%) cited other types of documents, such as websites or books. Among hospital medicine recommendations, 9 (90%) referenced CPGs and 1 (10%) cited an observational study.

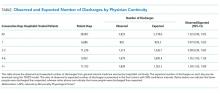

For the AGREE II assessment, we included 23 CPGs from the 225 referenced across all recommendations, after which we separately selected 6 CPGs from the hospital medicine recommendations. There was no overlap. Notably, 4 hospital medicine recommendations referenced a common CPG. Among the random sample of referenced CPGs, the median overall score obtained by using AGREE II was 54.2% (IQR 33.3%-70.8%, Table 2). This was similar to the median overall among hospital medicine guidelines (58.2%, IQR 50.0%-83.3%). Both hospital medicine and other sampled guidelines tended to score poorly in stakeholder involvement (48.6%, IQR 44.1%-61.1% and 47.2%, IQR 38.9%-61.1%, respectively). There were no significant differences between hospital medicine-referenced CPGs and the larger sample of CPGs in any AGREE II subdomains. The median age from the CPG publication to the list publication was 7 years (IQR 4–7) for hospital medicine recommendations and 3 years (IQR 2–6) for the nonhospital medicine recommendations. Substantial agreement was found between raters on the overall guideline assessment (ICC 0.80, 95% CI 0.58-0.91; Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of recommendation strengths and evidence grades, several recommendations were backed by Grades II–III (on a scale of I-III) evidence and level C (on a scale of A–C) recommendations in the reviewed CPG (Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Recommendation 4, and Heart Rhythm Society, Recommendation 1). In one other case, the cited CPG did not directly address the Choosing Wisely® item (Society of Vascular Medicine, Recommendation 2).

DISCUSSION

Given the rising costs and the potential for iatrogenic harm, curbing ineffective practices has become an urgent concern. To achieve this, the Choosing Wisely® campaign has taken an important step by targeting certain low-value practices for de-adoption. However, the evidence supporting recommendations is variable. Specifically, 25 recommendations cited case series, review articles, or lower quality evidence as their highest level of support; moreover, among recommendations citing CPGs, quality, timeliness, and support for the recommendation item were variable. Although the hospital medicine lists tended to cite higher-quality evidence in the form of CPGs, these CPGs were often less recent than the guidelines referenced by other lists.

Our findings parallel those of other works that evaluate evidence among Choosing Wisely® recommendations and, more broadly, among CPGs.18–21 Lin and Yancey evaluated the quality of primary care-focused Choosing Wisely® recommendations using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, a ranking system that evaluates evidence quality, consistency, and patient-centeredness.18 In their analysis, the authors found that many recommendations were based on lower quality evidence or relied on nonpatent-centered intermediate outcomes. Several groups, meanwhile, have evaluated the quality of evidence supporting CPG recommendations, finding them to be highly variable as well.19–21 These findings likely reflect inherent difficulties in the process, by which guideline development groups distill a broad evidence base into useful clinical recommendations, a reality that may have influenced the Choosing Wisely® list development groups seeking to make similar recommendations on low-value services.

These data should be taken in context due to several limitations. First, our sample of referenced CPGs includes only a small sample of all CPGs cited; thus, it may not be representative of all referenced guidelines. Second, the AGREE II assessment is inherently subjective, despite the availability of training materials. Third, data collection ended in April, 2014. Although this represents a majority of published lists to date, it is possible that more recent Choosing Wisely®lists include a stronger focus on evidence quality. Finally, references cited by Choosing Wisely®may not be representative of the entirety of the dataset that was considered when formulating the recommendations.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that Choosing Wisely®recommendations vary in terms of evidence strength. Although our results reveal that the majority of recommendations cite guidelines or high-quality original research, evidence gaps remain, with a small number citing low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. Given the barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, such campaigns as Choosing Wisely®face an uphill battle in their attempt to prompt behavior changes among providers and consumers.6-9 As a result, it is incumbent on funding agencies and medical journals to promote studies evaluating the harms and overall value of the care we deliver.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a majority of Choosing Wisely® recommendations cite high-quality evidence, some reference low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. To overcome clinical inertia and other barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, a clear rationale for the impetus to eradicate entrenched practices is critical.2,22 Choosing Wisely® has provided visionary leadership and a powerful platform to question low-value care. To expand the campaign’s efforts, the medical field must be able to generate the high-quality evidence necessary to support these efforts; further, list development groups must consider the availability of strong evidence when targeting services for de-implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. K08HS020672, Dr. Cooke).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong P, Saudners R, Olsen L, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. PubMed

2. Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386-388. PubMed

3. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. PubMed

6. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

7. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, Barron J, Brady P, Liu Y, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

8. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA. Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):210-217. PubMed

9. Bishop TF, Cea M, Miranda Y, Kim R, Lash-Dardia M, Lee JI, et al. Academic physicians’ views on low-value services and the choosing wisely campaign: A qualitative study. Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):17-22. PubMed

10. Prochaska MT, Hohmann SF, Modes M, Arora VM. Trends in Troponin-only testing for AMI in academic teaching hospitals and the impact of Choosing Wisely®. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):957-962. PubMed

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. PubMed

12. ABIM Foundation. ChoosingWisely.org Search Recommendations. 2014.

13. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(5):421-424. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. He Z, Tian H, Song A, Jin L, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(12):e635. PubMed

17. Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, Robinson JL. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):732-738. PubMed

18. Lin KW, Yancey JR. Evaluating the Evidence for Choosing WiselyTM in Primary Care Using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):512-515. PubMed

19. McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e250. PubMed

20. Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. PubMed

21. Feuerstein JD, Gifford AE, Akbari M, Goldman J, Leffler DA, Sheth SG, et al. Systematic analysis underlying the quality of the scientific evidence and conflicts of interest in gastroenterology practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1686-1693. PubMed

22. Robert G, Harlock J, Williams I. Disentangling rhetoric and reality: an international Delphi study of factors and processes that facilitate the successful implementation of decisions to decommission healthcare services. Implement Sci. 2014;9:123. PubMed

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

Guideline Appraisal

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

A total of 320 recommendations were considered in our analysis, including 10 published across the 2 hospital medicine lists. When limited to the highest quality citation for each of the recommendations, 225 (70.3%) cited CPGs, whereas 71 (22.2%) cited primary research articles (Table 1). Specifically, 29 (9.1%) cited systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 28 (8.8%) cited observational studies, and 13 (4.1%) cited RCTs. One recommendation (0.3%) cited a case series as its highest level of evidence, 7 (2.2%) cited review articles, 7 (2.2%) cited editorials or opinion pieces, and 10 (3.1%) cited other types of documents, such as websites or books. Among hospital medicine recommendations, 9 (90%) referenced CPGs and 1 (10%) cited an observational study.

For the AGREE II assessment, we included 23 CPGs from the 225 referenced across all recommendations, after which we separately selected 6 CPGs from the hospital medicine recommendations. There was no overlap. Notably, 4 hospital medicine recommendations referenced a common CPG. Among the random sample of referenced CPGs, the median overall score obtained by using AGREE II was 54.2% (IQR 33.3%-70.8%, Table 2). This was similar to the median overall among hospital medicine guidelines (58.2%, IQR 50.0%-83.3%). Both hospital medicine and other sampled guidelines tended to score poorly in stakeholder involvement (48.6%, IQR 44.1%-61.1% and 47.2%, IQR 38.9%-61.1%, respectively). There were no significant differences between hospital medicine-referenced CPGs and the larger sample of CPGs in any AGREE II subdomains. The median age from the CPG publication to the list publication was 7 years (IQR 4–7) for hospital medicine recommendations and 3 years (IQR 2–6) for the nonhospital medicine recommendations. Substantial agreement was found between raters on the overall guideline assessment (ICC 0.80, 95% CI 0.58-0.91; Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of recommendation strengths and evidence grades, several recommendations were backed by Grades II–III (on a scale of I-III) evidence and level C (on a scale of A–C) recommendations in the reviewed CPG (Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Recommendation 4, and Heart Rhythm Society, Recommendation 1). In one other case, the cited CPG did not directly address the Choosing Wisely® item (Society of Vascular Medicine, Recommendation 2).

DISCUSSION

Given the rising costs and the potential for iatrogenic harm, curbing ineffective practices has become an urgent concern. To achieve this, the Choosing Wisely® campaign has taken an important step by targeting certain low-value practices for de-adoption. However, the evidence supporting recommendations is variable. Specifically, 25 recommendations cited case series, review articles, or lower quality evidence as their highest level of support; moreover, among recommendations citing CPGs, quality, timeliness, and support for the recommendation item were variable. Although the hospital medicine lists tended to cite higher-quality evidence in the form of CPGs, these CPGs were often less recent than the guidelines referenced by other lists.

Our findings parallel those of other works that evaluate evidence among Choosing Wisely® recommendations and, more broadly, among CPGs.18–21 Lin and Yancey evaluated the quality of primary care-focused Choosing Wisely® recommendations using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, a ranking system that evaluates evidence quality, consistency, and patient-centeredness.18 In their analysis, the authors found that many recommendations were based on lower quality evidence or relied on nonpatent-centered intermediate outcomes. Several groups, meanwhile, have evaluated the quality of evidence supporting CPG recommendations, finding them to be highly variable as well.19–21 These findings likely reflect inherent difficulties in the process, by which guideline development groups distill a broad evidence base into useful clinical recommendations, a reality that may have influenced the Choosing Wisely® list development groups seeking to make similar recommendations on low-value services.

These data should be taken in context due to several limitations. First, our sample of referenced CPGs includes only a small sample of all CPGs cited; thus, it may not be representative of all referenced guidelines. Second, the AGREE II assessment is inherently subjective, despite the availability of training materials. Third, data collection ended in April, 2014. Although this represents a majority of published lists to date, it is possible that more recent Choosing Wisely®lists include a stronger focus on evidence quality. Finally, references cited by Choosing Wisely®may not be representative of the entirety of the dataset that was considered when formulating the recommendations.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that Choosing Wisely®recommendations vary in terms of evidence strength. Although our results reveal that the majority of recommendations cite guidelines or high-quality original research, evidence gaps remain, with a small number citing low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. Given the barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, such campaigns as Choosing Wisely®face an uphill battle in their attempt to prompt behavior changes among providers and consumers.6-9 As a result, it is incumbent on funding agencies and medical journals to promote studies evaluating the harms and overall value of the care we deliver.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a majority of Choosing Wisely® recommendations cite high-quality evidence, some reference low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. To overcome clinical inertia and other barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, a clear rationale for the impetus to eradicate entrenched practices is critical.2,22 Choosing Wisely® has provided visionary leadership and a powerful platform to question low-value care. To expand the campaign’s efforts, the medical field must be able to generate the high-quality evidence necessary to support these efforts; further, list development groups must consider the availability of strong evidence when targeting services for de-implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. K08HS020672, Dr. Cooke).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

As healthcare costs rise, physicians and other stakeholders are now seeking innovative and effective ways to reduce the provision of low-value services.1,2 The Choosing Wisely® campaign aims to further this goal by promoting lists of specific procedures, tests, and treatments that providers should avoid in selected clinical settings.3 On February 21, 2013, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) released 2 Choosing Wisely® lists consisting of adult and pediatric services that are seen as costly to consumers and to the healthcare system, but which are often nonbeneficial or even harmful.4,5 A total of 80 physician and nurse specialty societies have joined in submitting additional lists.

Despite the growing enthusiasm for this effort, questions remain regarding the Choosing Wisely® campaign’s ability to initiate the meaningful de-adoption of low-value services. Specifically, prior efforts to reduce the use of services deemed to be of questionable benefit have met several challenges.2,6 Early analyses of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations reveal similar roadblocks and variable uptakes of several recommendations.7-10 While the reasons for difficulties in achieving de-adoption are broad, one important factor in whether clinicians are willing to follow guideline recommendations from such initiatives as Choosing Wisely®is the extent to which they believe in the underlying evidence.11 The current work seeks to formally evaluate the evidence supporting the Choosing Wisely® recommendations, and to compare the quality of evidence supporting SHM lists to other published Choosing Wisely® lists.

METHODS

Data Sources

Using the online listing of published Choosing Wisely® recommendations, a dataset was generated incorporating all 320 recommendations comprising the 58 lists published through August, 2014; these include both the adult and pediatric hospital medicine lists released by the SHM.4,5,12 Although data collection ended at this point, this represents a majority of all 81 lists and 535 recommendations published through December, 2017. The reviewers (A.J.A., A.G., M.W., T.S.V., M.S., and C.R.C) extracted information about the references cited for each recommendation.

Data Analysis

The reviewers obtained each reference cited by a Choosing Wisely® recommendation and categorized it by evidence strength along the following hierarchy: clinical practice guideline (CPG), primary research, review article, expert opinion, book, or others/unknown. CPGs were used as the highest level of evidence based on standard expectations for methodological rigor.13 Primary research was further rated as follows: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, and case series. Each recommendation was graded using only the strongest piece of evidence cited.

Guideline Appraisal

We further sought to evaluate the strength of referenced CPGs. To accomplish this, a 10% random sample of the Choosing Wisely® recommendations citing CPGs was selected, and the referenced CPGs were obtained. Separately, CPGs referenced by the SHM-published adult and pediatric lists were also obtained. For both groups, one CPG was randomly selected when a recommendation cited more than one CPG. These guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, a widely used instrument designed to assess CPG quality.14,15 AGREE II consists of 25 questions categorized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Guidelines are also assigned an overall score. Two trained reviewers (A.J.A. and A.G.) assessed each of the sampled CPGs using a standardized form. Scores were then standardized using the method recommended by the instrument and reported as a percentage of available points. Although a standard interpretation of scores is not provided by the instrument, prior applications deemed scores below 50% as deficient16,17. When a recommendation item cited multiple CPGs, one was randomly selected. We also abstracted data on the year of publication, the evidence grade assigned to specific items recommended by Choosing Wisely®, and whether the CPG addressed the referring recommendation. All data management and analysis were conducted using Stata (V14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

A total of 320 recommendations were considered in our analysis, including 10 published across the 2 hospital medicine lists. When limited to the highest quality citation for each of the recommendations, 225 (70.3%) cited CPGs, whereas 71 (22.2%) cited primary research articles (Table 1). Specifically, 29 (9.1%) cited systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 28 (8.8%) cited observational studies, and 13 (4.1%) cited RCTs. One recommendation (0.3%) cited a case series as its highest level of evidence, 7 (2.2%) cited review articles, 7 (2.2%) cited editorials or opinion pieces, and 10 (3.1%) cited other types of documents, such as websites or books. Among hospital medicine recommendations, 9 (90%) referenced CPGs and 1 (10%) cited an observational study.

For the AGREE II assessment, we included 23 CPGs from the 225 referenced across all recommendations, after which we separately selected 6 CPGs from the hospital medicine recommendations. There was no overlap. Notably, 4 hospital medicine recommendations referenced a common CPG. Among the random sample of referenced CPGs, the median overall score obtained by using AGREE II was 54.2% (IQR 33.3%-70.8%, Table 2). This was similar to the median overall among hospital medicine guidelines (58.2%, IQR 50.0%-83.3%). Both hospital medicine and other sampled guidelines tended to score poorly in stakeholder involvement (48.6%, IQR 44.1%-61.1% and 47.2%, IQR 38.9%-61.1%, respectively). There were no significant differences between hospital medicine-referenced CPGs and the larger sample of CPGs in any AGREE II subdomains. The median age from the CPG publication to the list publication was 7 years (IQR 4–7) for hospital medicine recommendations and 3 years (IQR 2–6) for the nonhospital medicine recommendations. Substantial agreement was found between raters on the overall guideline assessment (ICC 0.80, 95% CI 0.58-0.91; Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of recommendation strengths and evidence grades, several recommendations were backed by Grades II–III (on a scale of I-III) evidence and level C (on a scale of A–C) recommendations in the reviewed CPG (Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Recommendation 4, and Heart Rhythm Society, Recommendation 1). In one other case, the cited CPG did not directly address the Choosing Wisely® item (Society of Vascular Medicine, Recommendation 2).

DISCUSSION

Given the rising costs and the potential for iatrogenic harm, curbing ineffective practices has become an urgent concern. To achieve this, the Choosing Wisely® campaign has taken an important step by targeting certain low-value practices for de-adoption. However, the evidence supporting recommendations is variable. Specifically, 25 recommendations cited case series, review articles, or lower quality evidence as their highest level of support; moreover, among recommendations citing CPGs, quality, timeliness, and support for the recommendation item were variable. Although the hospital medicine lists tended to cite higher-quality evidence in the form of CPGs, these CPGs were often less recent than the guidelines referenced by other lists.

Our findings parallel those of other works that evaluate evidence among Choosing Wisely® recommendations and, more broadly, among CPGs.18–21 Lin and Yancey evaluated the quality of primary care-focused Choosing Wisely® recommendations using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy, a ranking system that evaluates evidence quality, consistency, and patient-centeredness.18 In their analysis, the authors found that many recommendations were based on lower quality evidence or relied on nonpatent-centered intermediate outcomes. Several groups, meanwhile, have evaluated the quality of evidence supporting CPG recommendations, finding them to be highly variable as well.19–21 These findings likely reflect inherent difficulties in the process, by which guideline development groups distill a broad evidence base into useful clinical recommendations, a reality that may have influenced the Choosing Wisely® list development groups seeking to make similar recommendations on low-value services.

These data should be taken in context due to several limitations. First, our sample of referenced CPGs includes only a small sample of all CPGs cited; thus, it may not be representative of all referenced guidelines. Second, the AGREE II assessment is inherently subjective, despite the availability of training materials. Third, data collection ended in April, 2014. Although this represents a majority of published lists to date, it is possible that more recent Choosing Wisely®lists include a stronger focus on evidence quality. Finally, references cited by Choosing Wisely®may not be representative of the entirety of the dataset that was considered when formulating the recommendations.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that Choosing Wisely®recommendations vary in terms of evidence strength. Although our results reveal that the majority of recommendations cite guidelines or high-quality original research, evidence gaps remain, with a small number citing low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. Given the barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, such campaigns as Choosing Wisely®face an uphill battle in their attempt to prompt behavior changes among providers and consumers.6-9 As a result, it is incumbent on funding agencies and medical journals to promote studies evaluating the harms and overall value of the care we deliver.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a majority of Choosing Wisely® recommendations cite high-quality evidence, some reference low-quality evidence or low-quality CPGs as their highest form of support. To overcome clinical inertia and other barriers to the successful de-implementation of low-value services, a clear rationale for the impetus to eradicate entrenched practices is critical.2,22 Choosing Wisely® has provided visionary leadership and a powerful platform to question low-value care. To expand the campaign’s efforts, the medical field must be able to generate the high-quality evidence necessary to support these efforts; further, list development groups must consider the availability of strong evidence when targeting services for de-implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (No. K08HS020672, Dr. Cooke).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong P, Saudners R, Olsen L, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. PubMed

2. Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386-388. PubMed

3. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. PubMed

6. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

7. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, Barron J, Brady P, Liu Y, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

8. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA. Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):210-217. PubMed

9. Bishop TF, Cea M, Miranda Y, Kim R, Lash-Dardia M, Lee JI, et al. Academic physicians’ views on low-value services and the choosing wisely campaign: A qualitative study. Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):17-22. PubMed

10. Prochaska MT, Hohmann SF, Modes M, Arora VM. Trends in Troponin-only testing for AMI in academic teaching hospitals and the impact of Choosing Wisely®. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):957-962. PubMed

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. PubMed

12. ABIM Foundation. ChoosingWisely.org Search Recommendations. 2014.

13. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(5):421-424. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. He Z, Tian H, Song A, Jin L, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(12):e635. PubMed

17. Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, Robinson JL. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):732-738. PubMed

18. Lin KW, Yancey JR. Evaluating the Evidence for Choosing WiselyTM in Primary Care Using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):512-515. PubMed

19. McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e250. PubMed

20. Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. PubMed

21. Feuerstein JD, Gifford AE, Akbari M, Goldman J, Leffler DA, Sheth SG, et al. Systematic analysis underlying the quality of the scientific evidence and conflicts of interest in gastroenterology practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1686-1693. PubMed

22. Robert G, Harlock J, Williams I. Disentangling rhetoric and reality: an international Delphi study of factors and processes that facilitate the successful implementation of decisions to decommission healthcare services. Implement Sci. 2014;9:123. PubMed

1. Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong P, Saudners R, Olsen L, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2010. PubMed

2. Weinberger SE. Providing high-value, cost-conscious care: a critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):386-388. PubMed

3. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. PubMed

4. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, Goldstein J, O’Callaghan J, Auron M, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

5. Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. PubMed

6. Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. PubMed

7. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, Barron J, Brady P, Liu Y, et al. Early trends among seven recommendations from the Choosing Wisely campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

8. Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA. Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):210-217. PubMed

9. Bishop TF, Cea M, Miranda Y, Kim R, Lash-Dardia M, Lee JI, et al. Academic physicians’ views on low-value services and the choosing wisely campaign: A qualitative study. Healthc (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):17-22. PubMed

10. Prochaska MT, Hohmann SF, Modes M, Arora VM. Trends in Troponin-only testing for AMI in academic teaching hospitals and the impact of Choosing Wisely®. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):957-962. PubMed

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. PubMed

12. ABIM Foundation. ChoosingWisely.org Search Recommendations. 2014.

13. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(5):421-424. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. He Z, Tian H, Song A, Jin L, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on pancreatic cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(12):e635. PubMed

17. Isaac A, Saginur M, Hartling L, Robinson JL. Quality of reporting and evidence in American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):732-738. PubMed

18. Lin KW, Yancey JR. Evaluating the Evidence for Choosing WiselyTM in Primary Care Using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):512-515. PubMed

19. McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e250. PubMed

20. Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. PubMed

21. Feuerstein JD, Gifford AE, Akbari M, Goldman J, Leffler DA, Sheth SG, et al. Systematic analysis underlying the quality of the scientific evidence and conflicts of interest in gastroenterology practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1686-1693. PubMed

22. Robert G, Harlock J, Williams I. Disentangling rhetoric and reality: an international Delphi study of factors and processes that facilitate the successful implementation of decisions to decommission healthcare services. Implement Sci. 2014;9:123. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Patient Perceptions of Readmission Risk: An Exploratory Survey

Recent years have seen a proliferation of programs designed to prevent readmissions, including patient education initiatives, financial assistance programs, postdischarge services, and clinical personnel assigned to help patients navigate their posthospitalization clinical care. Although some strategies do not require direct patient participation (such as timely and effective handoffs between inpatient and outpatient care teams), many rely upon a commitment by the patient to participate in the postdischarge care plan. At our hospital, we have found that only about 2/3 of patients who are offered transitional interventions (such as postdischarge phone calls by nurses or home nursing through a “transition guide” program) receive the intended interventions, and those who do not receive them are more likely to be readmitted.1 While limited patient uptake may relate, in part, to factors that are difficult to overcome, such as inadequate housing or phone service, we have also encountered patients whose values, beliefs, or preferences about their care do not align with those of the care team. The purposes of this exploratory study were to (1) assess patient attitudes surrounding readmission, (2) ascertain whether these attitudes are associated with actual readmission, and (3) determine whether patients can estimate their own risk of readmission.

METHODS

From January 2014 to September 2016, we circulated surveys to patients on internal medicine nursing units who were being discharged home within 24 hours. Blank surveys were distributed to nursing units by the researchers. Unit clerks and support staff were educated on the purpose of the project and asked to distribute surveys to patients who were identified by unit case managers or nurses as slated for discharge. Staff members were not asked to help with or supervise survey completion. Surveys were generally filled out by patients, but we allowed family members to assist patients if needed, and to indicate so with a checkbox. There were no exclusion criteria. Because surveys were distributed by clinical staff, the received surveys can be considered a convenience sample. Patients were asked 5 questions with 4- or 5-point Likert scale responses:

(1) “How likely is it that you will be admitted to the hospital (have to stay in the hospital overnight) again within the next 30 days after you leave the hospital this time?” [answers ranging from “Very Unlikely (<5% chance)” to “Very Likely (>50% chance)”];

(2) “How would you feel about being rehospitalized in the next month?” [answers ranging from “Very sad, frustrated, or disappointed” to “Very happy or relieved”];

(3) “How much do you think that you personally can control whether or not you will be rehospitalized (based on what you do to take care of your body, take your medicines, and follow-up with your healthcare team)?” [answers ranging from “I have no control over whether I will be rehospitalized” to “I have complete control over whether I will be rehospitalized”];

(4) “Which of the options below best describes how you plan to follow the medical instructions after you leave the hospital?” [answers ranging from “I do NOT plan to do very much of what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team” to “I plan to do EVERYTHING I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists and other members of the care team”]; and

(5) “Pick the item below that best describes YOUR OWN VIEW of the care team’s recommendations:” [answers ranging from “I DO NOT AGREE AT ALL that the best way to be healthy is to do exactly what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team” to “I FULLY AGREE that the best way to be healthy is to do exactly what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team”].

Responses were linked, based on discharge date and medical record number, to administrative data, including age, sex, race, payer, and clinical data. Subsequent hospitalizations to our hospital were ascertained from administrative data. We estimated expected risk of readmission using the all payer refined diagnosis related group coupled with the associated severity-of-illness (SOI) score, as we have reported previously.2-5 We restricted our analysis to patients who answered the question related to the likelihood of readmission. Logistic regression models were constructed using actual 30-day readmission as the dependent variable to determine whether patients could predict their own readmissions and whether patient attitudes and beliefs about their care were predictive of subsequent readmission. Patient survey responses were entered as continuous independent variables (ranging from 1-4 or 1-5, as appropriate). Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine whether patients could predict their readmissions independent of demographic variables and expected readmission rate (modeled continuously); we repeated this model after dichotomizing the patient’s estimate of the likelihood of readmission as either “unlikely” or “likely.” Patients with missing survey responses were excluded from individual models without imputation. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board.

RESULTS

Responses were obtained from 895 patients. Their median age was 56 years [interquartile range, 43-67], 51.4% were female, and 41.7% were white. Mean SOI was 2.53 (on a 1-4 scale), and median length-of-stay was representative for our medical service at 5.2 days (range, 1-66 days). Family members reported filling out the survey in 57 cases. The primary payer was Medicare in 40.7%, Medicaid in 24.9%, and other in 34.4%. A total of 138 patients (15.4%) were readmitted within 30 days. The Table shows survey responses and associated readmission rates. None of the attitudes related to readmission were predictive of actual readmission. However, patients were able to predict their own readmissions (P = .002 for linear trend). After adjustment for expected readmission rate, race, sex, age, and payer, the trend remained significant (P = .005). Other significant predictors of readmissions in this model included expected readmission rate (P = .002), age (P = .02), and payer (P = .002). After dichotomizing the patient estimate of readmission rate as “unlikely” (N = 581) or “likely” (N = 314), the unadjusted odds ratio associating a patient-estimated risk of readmission as “likely” with actual readmission was 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.5). The adjusted odds ratio (including the variables above) was 1.6 (1.1-2.4).

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that patients are able to quantify their own readmission risk. This was true even after adjustment for expected readmission rate, age, sex, race, and payer. However, we did not identify any patient attitudes, beliefs, or preferences related to readmission or discharge instructions that were associated with subsequent rehospitalization. Reassuringly, more than 80% of patients who responded to the survey indicated that they would be sad, frustrated, or disappointed should readmission occur. This suggests that most patients are invested in preventing rehospitalization. Also reassuring was that patients indicated that they agreed with the discharge care plan and intended to follow their discharge instructions.

The major limitation of this study is that it was a convenience sample. Surveys were distributed inconsistently by nursing unit staff, preventing us from calculating a response rate. Further, it is possible, if not likely, that those patients with higher levels of engagement were more likely to take the time to respond, enriching our sample with activated patients. Although we allowed family members to fill out surveys on behalf of patients, this was done in fewer than 10% of instances; as such, our data may have limited applicability to patients who are physically or cognitively unable to participate in the discharge process. Finally, in this study, we did not capture readmissions to other facilities.

We conclude that patients are able to predict their own readmissions, even after accounting for other potential predictors of readmission. However, we found no evidence to support the possibility that low levels of engagement, limited trust in the healthcare team, or nonchalance about being readmitted are associated with subsequent rehospitalization. Whether asking patients about their perceived risk of readmission might help target readmission prevention programs deserves further study.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Daniel J. Brotman had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the study data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors also thank the following individuals for their contributions: Drafting the manuscript (Brotman); revising the manuscript for important intellectual content (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Hoyer, Deutschendorf); acquiring the data (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Deutschendorf); interpreting the data (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Hoyer, Deutschendorf); and analyzing the data (Brotman). The authors thank nursing leadership and nursing unit staff for their assistance in distributing surveys.

Funding support: Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Program

Disclosures: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

1. Hoyer EH, Brotman DJ, Apfel A, et al. Improving outcomes after hospitalization: a prospective observational multi-center evaluation of care-coordination strategies on 30-day readmissions to Maryland hospitals. J Gen Int Med. 2017 (in press). PubMed

2. Oduyebo I, Lehmann CU, Pollack CE, et al. Association of self-reported hospital discharge handoffs with 30-day readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):624-629. PubMed

3. Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Atanelov L, Knox B, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277-282. PubMed

4. Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Miller J, Deutschendorf A, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Functional status impairment is associated with unplanned readmissions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(10):1951-1958. PubMed

5. Hoyer EH, Odonkor CA, Bhatia SN, Leung C, Deutschendorf A, Brotman DJ. Association between days to complete inpatient discharge summaries with all-payer hospital readmissions in Maryland. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):393-400. PubMed

Recent years have seen a proliferation of programs designed to prevent readmissions, including patient education initiatives, financial assistance programs, postdischarge services, and clinical personnel assigned to help patients navigate their posthospitalization clinical care. Although some strategies do not require direct patient participation (such as timely and effective handoffs between inpatient and outpatient care teams), many rely upon a commitment by the patient to participate in the postdischarge care plan. At our hospital, we have found that only about 2/3 of patients who are offered transitional interventions (such as postdischarge phone calls by nurses or home nursing through a “transition guide” program) receive the intended interventions, and those who do not receive them are more likely to be readmitted.1 While limited patient uptake may relate, in part, to factors that are difficult to overcome, such as inadequate housing or phone service, we have also encountered patients whose values, beliefs, or preferences about their care do not align with those of the care team. The purposes of this exploratory study were to (1) assess patient attitudes surrounding readmission, (2) ascertain whether these attitudes are associated with actual readmission, and (3) determine whether patients can estimate their own risk of readmission.

METHODS

From January 2014 to September 2016, we circulated surveys to patients on internal medicine nursing units who were being discharged home within 24 hours. Blank surveys were distributed to nursing units by the researchers. Unit clerks and support staff were educated on the purpose of the project and asked to distribute surveys to patients who were identified by unit case managers or nurses as slated for discharge. Staff members were not asked to help with or supervise survey completion. Surveys were generally filled out by patients, but we allowed family members to assist patients if needed, and to indicate so with a checkbox. There were no exclusion criteria. Because surveys were distributed by clinical staff, the received surveys can be considered a convenience sample. Patients were asked 5 questions with 4- or 5-point Likert scale responses:

(1) “How likely is it that you will be admitted to the hospital (have to stay in the hospital overnight) again within the next 30 days after you leave the hospital this time?” [answers ranging from “Very Unlikely (<5% chance)” to “Very Likely (>50% chance)”];

(2) “How would you feel about being rehospitalized in the next month?” [answers ranging from “Very sad, frustrated, or disappointed” to “Very happy or relieved”];

(3) “How much do you think that you personally can control whether or not you will be rehospitalized (based on what you do to take care of your body, take your medicines, and follow-up with your healthcare team)?” [answers ranging from “I have no control over whether I will be rehospitalized” to “I have complete control over whether I will be rehospitalized”];

(4) “Which of the options below best describes how you plan to follow the medical instructions after you leave the hospital?” [answers ranging from “I do NOT plan to do very much of what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team” to “I plan to do EVERYTHING I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists and other members of the care team”]; and

(5) “Pick the item below that best describes YOUR OWN VIEW of the care team’s recommendations:” [answers ranging from “I DO NOT AGREE AT ALL that the best way to be healthy is to do exactly what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team” to “I FULLY AGREE that the best way to be healthy is to do exactly what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team”].

Responses were linked, based on discharge date and medical record number, to administrative data, including age, sex, race, payer, and clinical data. Subsequent hospitalizations to our hospital were ascertained from administrative data. We estimated expected risk of readmission using the all payer refined diagnosis related group coupled with the associated severity-of-illness (SOI) score, as we have reported previously.2-5 We restricted our analysis to patients who answered the question related to the likelihood of readmission. Logistic regression models were constructed using actual 30-day readmission as the dependent variable to determine whether patients could predict their own readmissions and whether patient attitudes and beliefs about their care were predictive of subsequent readmission. Patient survey responses were entered as continuous independent variables (ranging from 1-4 or 1-5, as appropriate). Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine whether patients could predict their readmissions independent of demographic variables and expected readmission rate (modeled continuously); we repeated this model after dichotomizing the patient’s estimate of the likelihood of readmission as either “unlikely” or “likely.” Patients with missing survey responses were excluded from individual models without imputation. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board.

RESULTS

Responses were obtained from 895 patients. Their median age was 56 years [interquartile range, 43-67], 51.4% were female, and 41.7% were white. Mean SOI was 2.53 (on a 1-4 scale), and median length-of-stay was representative for our medical service at 5.2 days (range, 1-66 days). Family members reported filling out the survey in 57 cases. The primary payer was Medicare in 40.7%, Medicaid in 24.9%, and other in 34.4%. A total of 138 patients (15.4%) were readmitted within 30 days. The Table shows survey responses and associated readmission rates. None of the attitudes related to readmission were predictive of actual readmission. However, patients were able to predict their own readmissions (P = .002 for linear trend). After adjustment for expected readmission rate, race, sex, age, and payer, the trend remained significant (P = .005). Other significant predictors of readmissions in this model included expected readmission rate (P = .002), age (P = .02), and payer (P = .002). After dichotomizing the patient estimate of readmission rate as “unlikely” (N = 581) or “likely” (N = 314), the unadjusted odds ratio associating a patient-estimated risk of readmission as “likely” with actual readmission was 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.5). The adjusted odds ratio (including the variables above) was 1.6 (1.1-2.4).

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that patients are able to quantify their own readmission risk. This was true even after adjustment for expected readmission rate, age, sex, race, and payer. However, we did not identify any patient attitudes, beliefs, or preferences related to readmission or discharge instructions that were associated with subsequent rehospitalization. Reassuringly, more than 80% of patients who responded to the survey indicated that they would be sad, frustrated, or disappointed should readmission occur. This suggests that most patients are invested in preventing rehospitalization. Also reassuring was that patients indicated that they agreed with the discharge care plan and intended to follow their discharge instructions.

The major limitation of this study is that it was a convenience sample. Surveys were distributed inconsistently by nursing unit staff, preventing us from calculating a response rate. Further, it is possible, if not likely, that those patients with higher levels of engagement were more likely to take the time to respond, enriching our sample with activated patients. Although we allowed family members to fill out surveys on behalf of patients, this was done in fewer than 10% of instances; as such, our data may have limited applicability to patients who are physically or cognitively unable to participate in the discharge process. Finally, in this study, we did not capture readmissions to other facilities.

We conclude that patients are able to predict their own readmissions, even after accounting for other potential predictors of readmission. However, we found no evidence to support the possibility that low levels of engagement, limited trust in the healthcare team, or nonchalance about being readmitted are associated with subsequent rehospitalization. Whether asking patients about their perceived risk of readmission might help target readmission prevention programs deserves further study.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Daniel J. Brotman had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the study data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors also thank the following individuals for their contributions: Drafting the manuscript (Brotman); revising the manuscript for important intellectual content (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Hoyer, Deutschendorf); acquiring the data (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Deutschendorf); interpreting the data (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Hoyer, Deutschendorf); and analyzing the data (Brotman). The authors thank nursing leadership and nursing unit staff for their assistance in distributing surveys.

Funding support: Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Program

Disclosures: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Recent years have seen a proliferation of programs designed to prevent readmissions, including patient education initiatives, financial assistance programs, postdischarge services, and clinical personnel assigned to help patients navigate their posthospitalization clinical care. Although some strategies do not require direct patient participation (such as timely and effective handoffs between inpatient and outpatient care teams), many rely upon a commitment by the patient to participate in the postdischarge care plan. At our hospital, we have found that only about 2/3 of patients who are offered transitional interventions (such as postdischarge phone calls by nurses or home nursing through a “transition guide” program) receive the intended interventions, and those who do not receive them are more likely to be readmitted.1 While limited patient uptake may relate, in part, to factors that are difficult to overcome, such as inadequate housing or phone service, we have also encountered patients whose values, beliefs, or preferences about their care do not align with those of the care team. The purposes of this exploratory study were to (1) assess patient attitudes surrounding readmission, (2) ascertain whether these attitudes are associated with actual readmission, and (3) determine whether patients can estimate their own risk of readmission.

METHODS

From January 2014 to September 2016, we circulated surveys to patients on internal medicine nursing units who were being discharged home within 24 hours. Blank surveys were distributed to nursing units by the researchers. Unit clerks and support staff were educated on the purpose of the project and asked to distribute surveys to patients who were identified by unit case managers or nurses as slated for discharge. Staff members were not asked to help with or supervise survey completion. Surveys were generally filled out by patients, but we allowed family members to assist patients if needed, and to indicate so with a checkbox. There were no exclusion criteria. Because surveys were distributed by clinical staff, the received surveys can be considered a convenience sample. Patients were asked 5 questions with 4- or 5-point Likert scale responses:

(1) “How likely is it that you will be admitted to the hospital (have to stay in the hospital overnight) again within the next 30 days after you leave the hospital this time?” [answers ranging from “Very Unlikely (<5% chance)” to “Very Likely (>50% chance)”];

(2) “How would you feel about being rehospitalized in the next month?” [answers ranging from “Very sad, frustrated, or disappointed” to “Very happy or relieved”];

(3) “How much do you think that you personally can control whether or not you will be rehospitalized (based on what you do to take care of your body, take your medicines, and follow-up with your healthcare team)?” [answers ranging from “I have no control over whether I will be rehospitalized” to “I have complete control over whether I will be rehospitalized”];

(4) “Which of the options below best describes how you plan to follow the medical instructions after you leave the hospital?” [answers ranging from “I do NOT plan to do very much of what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team” to “I plan to do EVERYTHING I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists and other members of the care team”]; and

(5) “Pick the item below that best describes YOUR OWN VIEW of the care team’s recommendations:” [answers ranging from “I DO NOT AGREE AT ALL that the best way to be healthy is to do exactly what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team” to “I FULLY AGREE that the best way to be healthy is to do exactly what I am being asked to do by the doctors, nurses, therapists, and other members of the care team”].

Responses were linked, based on discharge date and medical record number, to administrative data, including age, sex, race, payer, and clinical data. Subsequent hospitalizations to our hospital were ascertained from administrative data. We estimated expected risk of readmission using the all payer refined diagnosis related group coupled with the associated severity-of-illness (SOI) score, as we have reported previously.2-5 We restricted our analysis to patients who answered the question related to the likelihood of readmission. Logistic regression models were constructed using actual 30-day readmission as the dependent variable to determine whether patients could predict their own readmissions and whether patient attitudes and beliefs about their care were predictive of subsequent readmission. Patient survey responses were entered as continuous independent variables (ranging from 1-4 or 1-5, as appropriate). Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine whether patients could predict their readmissions independent of demographic variables and expected readmission rate (modeled continuously); we repeated this model after dichotomizing the patient’s estimate of the likelihood of readmission as either “unlikely” or “likely.” Patients with missing survey responses were excluded from individual models without imputation. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board.

RESULTS

Responses were obtained from 895 patients. Their median age was 56 years [interquartile range, 43-67], 51.4% were female, and 41.7% were white. Mean SOI was 2.53 (on a 1-4 scale), and median length-of-stay was representative for our medical service at 5.2 days (range, 1-66 days). Family members reported filling out the survey in 57 cases. The primary payer was Medicare in 40.7%, Medicaid in 24.9%, and other in 34.4%. A total of 138 patients (15.4%) were readmitted within 30 days. The Table shows survey responses and associated readmission rates. None of the attitudes related to readmission were predictive of actual readmission. However, patients were able to predict their own readmissions (P = .002 for linear trend). After adjustment for expected readmission rate, race, sex, age, and payer, the trend remained significant (P = .005). Other significant predictors of readmissions in this model included expected readmission rate (P = .002), age (P = .02), and payer (P = .002). After dichotomizing the patient estimate of readmission rate as “unlikely” (N = 581) or “likely” (N = 314), the unadjusted odds ratio associating a patient-estimated risk of readmission as “likely” with actual readmission was 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.5). The adjusted odds ratio (including the variables above) was 1.6 (1.1-2.4).

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that patients are able to quantify their own readmission risk. This was true even after adjustment for expected readmission rate, age, sex, race, and payer. However, we did not identify any patient attitudes, beliefs, or preferences related to readmission or discharge instructions that were associated with subsequent rehospitalization. Reassuringly, more than 80% of patients who responded to the survey indicated that they would be sad, frustrated, or disappointed should readmission occur. This suggests that most patients are invested in preventing rehospitalization. Also reassuring was that patients indicated that they agreed with the discharge care plan and intended to follow their discharge instructions.

The major limitation of this study is that it was a convenience sample. Surveys were distributed inconsistently by nursing unit staff, preventing us from calculating a response rate. Further, it is possible, if not likely, that those patients with higher levels of engagement were more likely to take the time to respond, enriching our sample with activated patients. Although we allowed family members to fill out surveys on behalf of patients, this was done in fewer than 10% of instances; as such, our data may have limited applicability to patients who are physically or cognitively unable to participate in the discharge process. Finally, in this study, we did not capture readmissions to other facilities.

We conclude that patients are able to predict their own readmissions, even after accounting for other potential predictors of readmission. However, we found no evidence to support the possibility that low levels of engagement, limited trust in the healthcare team, or nonchalance about being readmitted are associated with subsequent rehospitalization. Whether asking patients about their perceived risk of readmission might help target readmission prevention programs deserves further study.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Daniel J. Brotman had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the study data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors also thank the following individuals for their contributions: Drafting the manuscript (Brotman); revising the manuscript for important intellectual content (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Hoyer, Deutschendorf); acquiring the data (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Deutschendorf); interpreting the data (Brotman, Shihab, Tieu, Cheng, Bertram, Hoyer, Deutschendorf); and analyzing the data (Brotman). The authors thank nursing leadership and nursing unit staff for their assistance in distributing surveys.

Funding support: Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Program

Disclosures: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

1. Hoyer EH, Brotman DJ, Apfel A, et al. Improving outcomes after hospitalization: a prospective observational multi-center evaluation of care-coordination strategies on 30-day readmissions to Maryland hospitals. J Gen Int Med. 2017 (in press). PubMed

2. Oduyebo I, Lehmann CU, Pollack CE, et al. Association of self-reported hospital discharge handoffs with 30-day readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):624-629. PubMed

3. Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Atanelov L, Knox B, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277-282. PubMed

4. Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Miller J, Deutschendorf A, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Functional status impairment is associated with unplanned readmissions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(10):1951-1958. PubMed

5. Hoyer EH, Odonkor CA, Bhatia SN, Leung C, Deutschendorf A, Brotman DJ. Association between days to complete inpatient discharge summaries with all-payer hospital readmissions in Maryland. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):393-400. PubMed

1. Hoyer EH, Brotman DJ, Apfel A, et al. Improving outcomes after hospitalization: a prospective observational multi-center evaluation of care-coordination strategies on 30-day readmissions to Maryland hospitals. J Gen Int Med. 2017 (in press). PubMed

2. Oduyebo I, Lehmann CU, Pollack CE, et al. Association of self-reported hospital discharge handoffs with 30-day readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):624-629. PubMed

3. Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Atanelov L, Knox B, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277-282. PubMed

4. Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Miller J, Deutschendorf A, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Functional status impairment is associated with unplanned readmissions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(10):1951-1958. PubMed

5. Hoyer EH, Odonkor CA, Bhatia SN, Leung C, Deutschendorf A, Brotman DJ. Association between days to complete inpatient discharge summaries with all-payer hospital readmissions in Maryland. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):393-400. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Influence of Hospitalist Continuity on the Likelihood of Patient Discharge in General Medicine Patients

In addition to treating patients, physicians frequently have other time commitments that could include administrative, teaching, research, and family duties. Inpatient medicine is particularly unforgiving to these nonclinical duties since patients have to be assessed on a daily basis. Because of this characteristic, it is not uncommon for inpatient care responsibility to be switched between physicians to create time for nonclinical duties and personal health.