User login

Get on top of home BP monitoring

Also today, opioid use in osteoarthritis may mean more activity-limiting pain, sulfasalazine is pinpointed as the reason for high triple-therapy discontinuation, and point-of-care test for respiratory viruses lowers antibiotic use.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, opioid use in osteoarthritis may mean more activity-limiting pain, sulfasalazine is pinpointed as the reason for high triple-therapy discontinuation, and point-of-care test for respiratory viruses lowers antibiotic use.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, opioid use in osteoarthritis may mean more activity-limiting pain, sulfasalazine is pinpointed as the reason for high triple-therapy discontinuation, and point-of-care test for respiratory viruses lowers antibiotic use.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Office approach to small fiber neuropathy

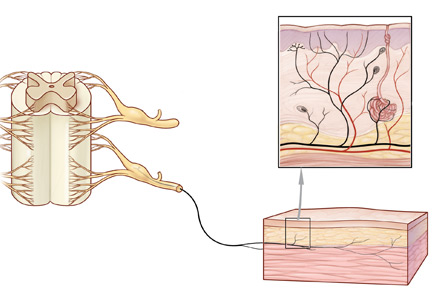

Peripheral neuropathy is the most common reason for an outpatient neurology visit in the United States and accounts for over $10 billion in healthcare spending each year.1,2 When the disorder affects only small, thinly myelinated or unmyelinated nerve fibers, it is referred to as small fiber neuropathy, which commonly presents as numbness and burning pain in the feet.

This article details the manifestations and evaluation of small fiber neuropathy, with an eye toward diagnosing an underlying cause amenable to treatment.

OLDER PATIENTS MOST AFFECTED

The epidemiology of small fiber neuropathy is not well established. It occurs more commonly in older patients, but data are mixed on prevalence by sex.3–6 In a Dutch study,3 the overall prevalence was at least 53 cases per 100,000, with the highest rate in men over age 65.

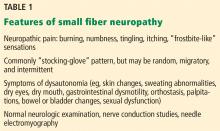

CHARACTERISTIC SENSORY DISTURBANCES

Sensations vary in quality and time

Patients with small fiber neuropathy typically present with a symmetric length-dependent (“stocking-glove”) distribution of sensory changes, starting in the feet and gradually ascending up the legs and then to the hands.

Commonly reported neuropathic symptoms include various combinations of burning, numbness, tingling, itching, sunburn-like, and frostbite-like sensations. Nonneuropathic symptoms may include tightness, a vise-like squeezing of the feet, and the sensation of a sock rolled up at the end of the shoe. Cramps or spasms may also be reported but rarely occur in isolation.7

Symptoms are typically worse at the end of the day and while sitting or lying down at night. They can arise spontaneously but may also be triggered by something as minor as the touch of clothing or cool air against the skin. Bedsheet sensitivity of the feet is reported so often that it is used as an outcome measure in clinical trials. Symptoms can also be exacerbated by extremes in ambient temperature and are especially worse in cold weather.

Random patterns suggest an immune cause

Symptoms may also have a non–length-dependent distribution that is asymmetric, patchy, intermittent, and migratory, and can involve the face, proximal limbs, and trunk. Symptoms may vary throughout the day, eg, starting with electric-shock sensations on one side of the face, followed by perineal numbness and then tingling in the arms lasting for a few minutes to several hours. While such patterns may be seen with diabetes and other common etiologies, they often suggest an underlying immune-mediated disorder such as Sjögren syndrome or sarcoidosis.8–10 Although large fiber polyneuropathy may also be non–length-dependent, the deficits are usually fixed, with no migratory component.

Autonomic features may be prominent

Autonomic symptoms occur in nearly half of patients and can be as troublesome as neuropathic pain.3 Small nerve fibers mediate somatic and autonomic functions, an evolutionary link that may reflect visceral defense mechanisms responding to pain as a signal of danger.11 This may help explain the multisystemic nature of symptoms, which can include sweating abnormalities, bowel and bladder disturbances, dry eyes, dry mouth, gastrointestinal dysmotility, skin changes (eg, discoloration, loss of hair, shiny skin), sexual dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and palpitations. In some cases, isolated dysautonomia may be seen.

TARGETED EXAMINATION

History: Medications, alcohol, infections

When a patient presents with neuropathic pain in the feet, a detailed history should be obtained, including alcohol use, family history of neuropathy, and use of neurotoxic medications such as metronidazole, colchicine, and chemotherapeutic agents.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C infection are well known to be associated with small fiber neuropathy, so relevant risk factors (eg, blood transfusions, sexual history, intravenous drug use) should be asked about. Recent illnesses and vaccinations are another important line of questioning, as a small-fiber variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome has been described.12

Assess reflexes, strength, sensation

On physical examination, particular attention should be focused on searching for abnormalities indicating large nerve fiber involvement (eg, absent deep tendon reflexes, weakness of the toes). However, absent ankle deep tendon reflexes and reduced vibratory sense may also occur in healthy elderly people.

Similarly, proprioception, motor strength, balance, and vibratory sensation are functions of large myelinated nerve fibers, and thus remain unaffected in patients with only small fiber neuropathy.

Evidence of a systemic disorder should also be sought, as it may indicate an underlying etiology.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Although patients with either large or small fiber neuropathy may have subjective hyperesthesia or numbness of the distal lower extremities, the absence of significant abnormalities on neurologic examination should prompt consideration of small fiber neuropathy.

Electromyography worthwhile

Nerve conduction studies and needle electrode examination evaluate only large nerve fiber conditions. While electromyographic results are normal in patients with isolated small fiber neuropathy, the test can help evaluate subclinical large nerve fiber involvement and alternative diagnoses such as bilateral S1 radiculopathy. Nerve conduction studies may be less useful in patients over age 75, as they may lack sural sensory responses because of aging changes.13

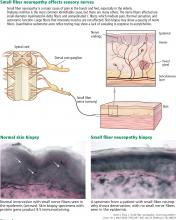

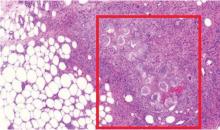

Skin biopsy easy to do

Skin biopsy for evaluating intraepidermal nerve fiber density is one of the most widely used tests for small fiber neuropathy. This minimally invasive procedure can now be performed in a primary care office using readily available tools or prepackaged kits and analyzed by several commercial laboratories.

Reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density on skin biopsy has been described in various other conditions such as fibromyalgia and chronic pain syndromes.16,17 The clinical significance of these findings remains uncertain.

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing (QSART) is a noninvasive autonomic study that assesses the volume of sweat produced by the limbs in response to acetylcholine. A measure of postganglionic sympathetic sudomotor nerve function, QSART has a sensitivity of up to 80% and can be used to diagnose small fiber neuropathy.18 In a series of 115 patients with sarcoidosis small fiber neuropathy,9 the QSART and skin biopsy findings were concordant in 17 cases and complementary in 29, allowing for confirmation of small fiber neuropathy in patients whose condition would have remained undiagnosed had only one test been performed. QSART can also be considered in cases where skin biopsy may be contraindicated (eg, patient use of anticoagulation). Of note, the study may be affected by a number of external factors, including caffeine, tobacco, antihistamines, and tricyclic antidepressants; these should be held before testing.

Other diagnostic studies

Other tests may be helpful, as follows:

Tilt-table and cardiovagal testing may be useful for patients with orthostasis and palpitations.

Thermoregulatory sweat testing can be used to evaluate patients with abnormal patterns of sweating, eg, hyperhidrosis of the face and head.

INITIAL TESTING FOR AN UNDERLYING CAUSE

Glucose tolerance test for diabetes

Diabetes is the most common identifiable cause of small fiber neuropathy and accounts for about a third of all cases.5 Impaired glucose tolerance is also thought to be a risk factor and has been found in up to 50% of idiopathic cases, but the association is still being debated.21

While testing for hemoglobin A1c is more convenient for the patient, especially because it does not require fasting, a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test is more sensitive for detecting glucose dysmetabolism.22

Lipid panel for metabolic syndrome

Small fiber neuropathy is associated with individual components of the metabolic syndrome, which include obesity, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Of these, dyslipidemia has emerged as the primary factor involved in the development of small fiber neuropathy, via an inflammatory pathway or oxidative stress mechanism.23,24

Vitamin B12 deficiency testing

Vitamin B12 deficiency, a potentially correctable cause of small fiber neuropathy, may be underdiagnosed, especially as values obtained by blood testing may not reflect tissue uptake. Causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include reduced intake, pernicious anemia, and medications that can affect absorption of vitamin B12 (eg, proton pump inhibitors, histamine 2 receptor antagonists, metformin).

Testing should include:

- Complete blood cell count to evaluate for vitamin B12-related macrocytic anemia and other hematologic abnormalities

- Serum vitamin B12 level

- Methylmalonic acid or homocysteine level in patients with subclinical or mild vitamin B12 deficiency, manifested as low to normal vitamin B12 levels (< 400 pg/mL); methylmalonic acid and homocysteine require vitamin B12 as a cofactor for enzymatic conversion, and either or both may be elevated in early vitamin B12 deficiency.

Celiac antibody panel

Celiac disease, a T-cell mediated enteropathy characterized by gluten intolerance and a herpetiform-like rash, can be associated with small fiber neuropathy.25 In some cases, neuropathy symptoms are preceded by the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms, or they may occur in isolation.25

Inflammatory disease testing

Sjögren syndrome accounts for nearly 10% of cases of small fiber neuropathy. Associated neuropathic symptoms are often non–length-dependent, can precede sicca symptoms for up to 6 years, and in some cases are the sole manifestation of the disease.10 Small fiber neuropathy may also be associated with vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue disorders.

Testing should include:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and antinuclear antibodies: though these are nonspecific markers of inflammation, they may support an immune-mediated etiology if positive

- Extractable nuclear antigen panel: Sjögren syndrome A and B autoantibodies are the most important components in this setting5,11

- The Schirmer test or salivary gland biopsy should be considered for seronegative patients with sicca or a suspected immune-mediated etiology, as the sensitivity of antibody testing ranges from only 10% to 55%.10

Thyroid function testing

Hypothyroidism, and less commonly hyperthyroidism, are associated with small fiber neuropathy.

Metabolic tests for liver and kidney disease

Renal insufficiency and liver impairment are well-known causes of small nerve fiber dysfunction. Testing should include:

- Comprehensive metabolic panel

- Gamma-glutamyltransferase if alcohol abuse is suspected, since heavy alcohol use is one of the most common causes of both large and small fiber neuropathy.

HIV and hepatitis C testing

For patients with relevant risk factors, HIV and hepatitis C testing should be part of the initial workup (and as second-tier testing for others). Patients who test positive for hepatitis C should undergo further testing for cryoglobulinemia, which can present with painful small fiber neuropathy.26

Serum and urine immunoelectrophoresis

Paraproteinemia, with causes ranging from monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance to multiple myeloma, has been associated with small fiber neuropathy. An abnormal serum or urine immunoelectrophoresis test warrants further investigation and possibly referral to a hematology-oncology specialist.

SECOND-TIER TESTING

Less common treatable causes of small fiber neuropathy may also be evaluated.

Copper, vitamin B1 (thiamine), or vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency testing. Although vitamin B6 toxicity may also result in neuropathy due to its toxic effect on the dorsal root ganglia, the mildly elevated vitamin B6 levels often found in patients being evaluated for neuropathy are unlikely to be the primary cause of symptoms. Many laboratories require fasting samples for accurate vitamin B6 levels.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels for sarcoidosis. Small fiber neuropathy is common in sarcoidosis, occurring in more than 30% of patients with systemic disease.27 However, screening for sarcoidosis by measuring serum levels is often falsely positive and is not cost-effective. In a study of 195 patients with idiopathic small fiber neuropathy,11 44% had an elevated serum level, but no evidence of sarcoidosis was seen on further testing, which included computed tomography of the chest in 29 patients.12 Thus, this test is best used for patients with evidence of systemic disease.

Amyloid testing for amyloidosis. Fat pad or bone marrow biopsy should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

Paraneoplastic autoantibody panel for occult cancer. Such testing may also be considered if clinically warranted. However, if a patient is found to have low positive titers of paraneoplastic antibodies and suspicion is low for an occult cancer (eg, no weight loss or early satiety), repeat confirmatory testing at another laboratory should be done before embarking on an extensive search for malignancy.

Ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody testing for autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. This should be ordered for patients with prominent autonomic dysfunction. The antibody test can be ordered separately or as part of an autoantibody panel. The antibody may indicate a primary immune-mediated process or a paraneoplastic disease.28

Genetic mutation testing. Recent discoveries of gene mutations leading to peripheral nerve hyperexcitability of voltage-gated sodium channels have elucidated a hereditary cause of small fiber neuropathy in nearly 30% of cases that were once thought to be idiopathic.29,30 Genetic testing for mutations in SCN9A and SCN10 (which code for the Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 sodium channels, respectively) is commercially available and may be considered for those with a family history of neuropathic pain in the feet or for young, otherwise healthy patients.

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal disorder characterized by angiokeratomas, cardiac and renal impairment, and small fiber neuropathy. Treatment is now available, but screening is not cost-efficient and should only be pursued in patients with other symptoms of the disease.31,32

OTHER POSSIBLE CAUSES

Guillain-Barré syndrome

A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant has been reported that is characterized by ascending limb paresthesias and cerebrospinal fluid albuminocytologic dissociation in the setting of preserved deep tendon reflexes and normal findings on EMG.12 The clinical course is similar to that of typical Guillain-Barré syndrome, in that symptoms follow an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, reach their nadir at 4 weeks, and then gradually improve. Some patients respond to intravenous immune globulin.

Vaccine-associated

Postvaccination small fiber neuropathy has also been reported. The nature of the association is unclear.33

Parkinson disease

Small fiber neuropathy is associated with Parkinson disease. It is attributed to a number of proposed factors, including neurodegeneration that occurs parallel to central nervous system decline, as well as intestinal malabsorption with resultant vitamin deficiency.34,35

Rapid glycemic lowering

Aggressive treatment of diabetes, defined as at least a 2-point reduction of serum hemoglobin A1c level over 3 months, may result in acute small fiber neuropathy. It manifests as severe distal extremity pain and dysautonomia.

In a retrospective study,36 104 (10.9%) of 954 patients presenting to a tertiary diabetic clinic developed treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy with symptoms occurring within 8 weeks of rapid glycemic control. The severity of neuropathy correlated with the degree and rate of glycemic lowering. The condition was reversible in some cases.

TREATING SPECIFIC DISORDERS

For patients with an identified cause of neuropathy, targeted treatment offers the best chance of halting progression and possibly improving symptoms. Below are recommendations for addressing neuropathy associated with the common diagnoses.

Diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, and metabolic syndrome. In addition to glycemic- and lipid-lowering therapies, lifestyle modifications with a specific focus on exercise and nutrition are integral to treating diabetes and related disorders.

In the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study,37 which evaluated the effects of intensive lifestyle intervention on neuropathy in 5,145 overweight patients with type 2 diabetes, patients in the intervention group had lower pain scores and better touch sensation in the toes compared with controls at 1 year. Differences correlated with the degree of weight loss and reduction of hemoglobin A1c and lipid levels.

As running and walking may not be feasible for many patients owing to pain, stationary cycling, aqua therapy, and swimming are other options. A stationary recumbent bike may be useful for older patients with balance issues.

Vitamin B12 deficiency. As reduced absorption rather than low dietary intake is the primary cause of vitamin B12 deficiency for many patients, parenteral rather than oral supplementation may be best. A suggested regimen is subcutaneous or intramuscular methylcobalamin injection of 1,000 µg given daily for 1 week, then once weekly for 1 month, followed by a maintenance dose once a month for at least 6 to 12 months. Alternatively, a daily dose of vitamin B12 1,000 µg can be taken sublingually.

Sjögren syndrome. According to anecdotal case reports, intravenous immune globulin, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants help painful small fiber neuropathy and dysautonomia associated with Sjögren syndrome.10

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis-associated small fiber neuropathy may also respond to intravenous immune globulin, as well as infliximab and combination therapy.9 Culver et al38 found that cibinetide, an experimental erythropoetin agonist, resulted in improved corneal nerve fiber measures in patients with small fiber neuropathy associated with sarcoidosis.

Celiac disease. A gluten-free diet is the treatment for celiac disease and can help some patients.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

For all patients, regardless of whether the cause of small fiber neuropathy has been identified, managing symptoms remains key, as pain and autonomic dysfunction can markedly impair quality of life. A multidisciplinary approach that incorporates pain medications, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications is ideal. Integrative holistic treatments such as natural supplements, yoga, and other mind-body therapies may also help.

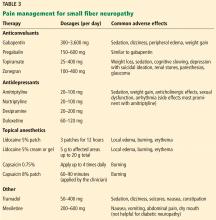

Pain control

Mexiletine, a voltage-gated sodium channel blocker used as an antiarrhythmic, may help refractory pain or hereditary small fiber neuropathy related to sodium channel dysfunction. However, it is not recommended for diabetic neuropathy.39

Combination regimens that use drugs with different mechanisms of action can be effective. In one study, combined gabapentin and nortriptyline were more effective than either drug alone for neuropathic pain.40

Inhaled cannabis reduced pain in patients with HIV and diabetic neuropathy in a number of studies. Side effects included euphoria, somnolence, and cognitive impairment.41,42 The use of medical marijuana is not yet legal nationwide and may affect employability even in states in which it has been legalized.

Owing to the opioid epidemic and high addiction potential, opioids are no longer a preferred recommendation for chronic treatment of noncancer-related neuropathy. A population-based study of 2,892 patients with neuropathy found that those on chronic opioid therapy (≥ 90 days) had worse functional outcomes and higher rates of addiction and overdose than those on short-term therapy.43 However, the opioid agonist tramadol was found to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain and may be a safer option for patients with chronic small fiber neuropathy.44

Integrative, holistic therapies

PROGNOSIS

For many patients, small fiber neuropathy is a slowly progressive disorder that reaches a clinical plateau lasting for years, with progression to large fiber involvement reported in 13% to 36% of cases; over half of patients in one series either improved or remained stable over a period of 2 years.5,57 Long-term studies are needed to fully understand the natural disease course. In the meantime, treating underlying disease and managing symptoms are imperative to patient care.

- Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Callaghan BC, Kerber KA. Choosing Wisely: highest-cost tests in outpatient neurology. Ann Neurol 2013; 73(5):679–683. doi:10.1002/ana.23865

- Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, Oglesby A, Tobian JA. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the US. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(6):1790–1795. pmid:12766111

- Peters MJ, Bakkers M, Merkies IS, Hoeijmakers JG, van Raak EP, Faber CG. Incidence and prevalence of small-fiber neuropathy: a survey in the Netherlands. Neurology 2013; 81(15):1356–1360. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a8236e

- Periquet MI, Novak V, Collins MP, et al. Painful sensory neuropathy: prospective evaluation using skin biopsy. Neurology 1999; 53(8):1641–1647. pmid:10563606

- Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain 2008; 131(pt 7):1912–1925. doi:10.1093/brain/awn093

- Lacomis D. Small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2002; 26(2):173–188. doi:10.1002/mus.10181

- Lopate G, Streif E, Harms M, Weihl C, Pestronk A. Cramps and small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2013; 48(2):252–255. doi:10.1002/mus.23757

- Khan S, Zhou L. Characterization of non-length-dependent small-fiber sensory neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2012; 45(1):86–91. doi:10.1002/mus.22255

- Tavee JO, Karwa K, Ahmed Z, Thompson N, Parambil J, Culver DA. Sarcoidosis-associated small fiber neuropathy in a large cohort: clinical aspects and response to IVIG and anti-TNF alpha treatment. Respir Med 2017; 126:135–138. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.03.011

- Berkowitz AL, Samuels MA. The neurology of Sjogren’s syndrome and the rheumatology of peripheral neuropathy and myelitis. Pract Neurol 2014; 14(1):14–22. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2013-000651

- Lang M, Treister R, Oaklander AL. Diagnostic value of blood tests for occult causes of initially idiopathic small-fiber polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2016; 263(12):2515–2527. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8270-5

- Seneviratne U, Gunasekera S. Acute small fibre sensory neuropathy: another variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72(4):540–542. pmid:11909922

- Tavee JO, Polston D, Zhou L, Shields RW, Butler RS, Levin KH. Sural sensory nerve action potential, epidermal nerve fiber density, and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex in the healthy elderly. Muscle Nerve 2014; 49(4):564–569. doi:10.1002/mus.23971

- Tavee J, Zhou L. Small fiber neuropathy: a burning problem. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76(5):297–305. doi:10.3949/ccjm.76a.08070

- Herrmann DN, Griffin JW, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, McArthur JC. Epidermal nerve fiber density and sural nerve morphometry in peripheral neuropathies. Neurology 1999; 53(8):1634–1640. pmid:10563605

- Oaklander AL, Herzog ZD, Downs HM, Klein MM. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain 2013; 154(11):2310–2316. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.001

- Üçeyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain 2013; 136(pt 6):1857–1867. doi:10.1093/brain/awt053

- Stewart JD, Low PA, Fealey RD. Distal small fiber neuropathy: results of tests of sweating and autonomic cardiovascular reflexes. Muscle Nerve 1992; 15(6):661–665. doi:10.1002/mus.880150605

- Malik RA, Kallinikos P, Abbott CA, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: a non-invasive surrogate of nerve fibre damage and repair in diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2003; 46(5):683–688. doi:10.1007/s00125-003-1086-8

- de Greef BTA, Hoeijmakers JGJ, Gorissen-Brouwers CML, Geerts M, Faber CG, Merkies ISJ. Associated conditions in small fiber neuropathy—a large cohort study and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol 2018; 25(2):348–355. doi:10.1111/ene.13508

- Smith AG. Impaired glucose tolerance and metabolic syndrome in idiopathic neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2012; 17(suppl 2):15–21. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00390.x

- Hoffman-Snyder C, Smith BE, Ross MA, Hernandez J, Bosch EP. Value of the oral glucose tolerance test in the evaluation of chronic idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol 2006; 63(8):1075–1079. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.8.noc50336

- Vincent AM, Hinder LM, Pop-Busui R, Feldman EL. Hyperlipidemia: a new therapeutic target for diabetic neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2009; 14(4):257–267. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2009.00237.x

- Wiggin TD, Sullivan KA, Pop-Busui R, Amato A, Sima AA, Feldman EL. Elevated triglycerides correlate with progression of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes 2009; 58(7):1634–1640. doi:10.2337/db08-1771

- Chin RL, Sander HW, Brannagan TH, et al. Celiac neuropathy. Neurology 2003; 60(10):1581–1585. pmid:12771245

- Gemignani F, Brindani F, Alfieri S, et al. Clinical spectrum of cryoglobulinaemic neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76(10):1410–1414. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.057620

- Bakkers M, Merkies IS, Lauria G, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density and its application in sarcoidosis. Neurology 2009; 73(14):1142–1148. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf05

- Vernino S, Low PA, Fealey RD, Stewart JD, Farrugia G, Lennon VA. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(12):847–855. doi:10.1056/NEJM200009213431204

- Faber CG, Hoeijmakers JG, Ahn HS, et al. Gain of function Nav1.7 mutations in idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. Ann Neurol 2012; 71(1):26–39. doi:10.1002/ana.22485

- Brouwer BA, Merkies IS, Gerrits MM, Waxman SG, Hoeijmakers JG, Faber CG. Painful neuropathies: the emerging role of sodium channelopathies. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2014; 19(2):53–65. doi:10.1111/jns5.12071

- Samuelsson K, Kostulas K, Vrethem M, Rolfs A, Press R. Idiopathic small fiber neuropathy: phenotype, etiologies, and the search for Fabry disease. J Clin Neurol 2014; 10(2):108–118. doi:10.3988/jcn.2014.10.2.108

- de Greef BT, Hoeijmakers JG, Wolters EE, et al. No Fabry disease in patients presenting with isolated small fiber neuropathy. PLoS One 2016; 11(2):e0148316. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148316

- Souayah N, Ajroud-Driss S, Sander HW, Brannagan TH, Hays AP, Chin RL. Small fiber neuropathy following vaccination for rabies, varicella or Lyme disease. Vaccine 2009; 27(52):7322–7325. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.077

- Nolano M, Provitera V, Manganelli F, et al. Loss of cutaneous large and small fibers in naive and l-dopa–treated PD patients. Neurology 2017; 89(8):776–784. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004274

- Zis P, Grünewald RA, Chaudhuri RK, Hadjivassiliou M. Peripheral neuropathy in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci 2017; 378:204–209. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2017.05.023

- Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes: an acute, iatrogenic complication of diabetes. Brain 2015; 138(pt 1):43–52. doi:10.1093/brain/awu307

- Look AHEAD Research Group. Effects of a long-term lifestyle modification programme on peripheral neuropathy in overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes: the Look AHEAD study. Diabetologia 2017; 60(6):980–988. doi:10.1007/s00125-017-4253-z

- Culver DA, Dahan A, Bajorunas D, et al. Cibinetide improves corneal nerve fiber abundance in patients with sarcoidosis-associated small nerve fiber loss and neuropathic pain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017; 58(6):BIO52–BIO60. doi:10.1167/iovs.16-21291

- Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, et al; American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine; American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM R 2011; 3(4):345–352.e21. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.03.008

- Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Jackson AC, Houlden RL. Nortriptyline and gabapentin, alone and in combination for neuropathic pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet 2009; 374(9697):1252–1261. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61081-3

- Ellis RJ, Toperoff W, Vaida F, et al. Smoked medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009; 34(3):672–680. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.120

- Wallace MS, Marcotte TD, Umlauf A, Gouaux B, Atkinson JH. Efficacy of inhaled cannabis on painful diabetic neuropathy. J Pain 2015; 16(7):616–627. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.008

- Hoffman EM, Watson JC, St Sauver J, Staff NP, Klein CJ. Association of long-term opioid therapy with functional status, adverse outcomes, and mortality among patients with polyneuropathy. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74(7):773–779. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0486

- Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of tramadol for the treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy. Neurology 1998; 50(6):1842–1846. pmid:9633738

- Sima AA, Calvani M, Mehra M, Amato A; Acetyl-L-Carnitine Study Group. Acetyl-L-carnitine improves pain, nerve regeneration, and vibratory perception in patients with chronic diabetic neuropathy: an analysis of two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2005; 28(1):89–94. pmid:15616239

- Ziegler D, Hanefeld M, Ruhnau KJ, et al. Treatment of symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy with the anti-oxidant alpha-lipoic acid. A 3-week multicentre randomized controlled trial (ALADIN Study). Diabetologia 1995; 38(12):1425–1433. pmid:8786016

- Scarpini E, Sacilotto G, Baron P, Cusini M, Scarlato G. Effect of acetyl-L-carnitine in the treatment of painful peripheral neuropathies in HIV+ patients. J Peripher Nerv Syst 1997; 2(3):250-252. pmid: 10975731

- Hershman DL, Unger JM, Crew KD, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of acetyl-L-carnitine for the prevention of taxane-induced neuropathy in women undergoing adjuvant breast cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(20):2627-2633. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8738

- Amara S. Oral glutamine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ann Pharmacother 2008; 42(10):1481-1485. doi:10.1345/aph.1L179

- Huang JS, Wu CL, Fan CW, Chen WH, Yeh KY, Chang PH. Intravenous glutamine appears to reduce the severity of symptomatic platinum-induced neuropathy: a prospective randomized study. J Chemother 2015; 27(4):235-240. doi:10.1179/1973947815Y.0000000011

- Banafshe HR, Hamidi GA, Noureddini M, Mirhashemi SM, Mokhtari R, Shoferpour M. Effect of curcumin on diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: possible involvement of opioid system. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 723:202-206. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.11.033

- Mendonça LM, da Silva Machado C, Teixeira CC, de Freitas LA, Bianchi MD, Antunes LM. Curcumin reduces cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity in NGF-differentiated PC12 cells. Neurotoxicology 2013; 34:205-211. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2012.09.011

- Wagner K, Lee KS, Yang J, Hammock BD. Epoxy fatty acids mediate analgesia in murine diabetic neuropathy. Eur J Pain 2017; 21(3):456-465. doi:10.1002/ejp.939

- Lewis EJ, Perkins BA, Lovblom LE, Bazinet RP, Wolever TMS, Bril V. Effect of omega-3 supplementation on neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: a 12-month pilot trial. Neurology 2017; 88(24):2294–2301. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004033

- Hu D, Wang C, Li F, et al. A combined water extract of frankincense and myrrh alleviates neuropathic pain in mice via modulation of TRPV1. Neural Plast 2017; 2017:3710821. doi:10.1155/2017/3710821

- Tavee J, Rensel M, Planchon SM, Butler RS, Stone L. Effects of meditation on pain and quality of life in multiple sclerosis and peripheral neuropathy: a pilot study. Int J MS Care 2011; 13(4):163–168. doi:10.7224/1537-2073-13.4.163

- Khoshnoodi MA, Truelove S, Burakgazi A, Hoke A, Mammen AL, Polydefkis M. Longitudinal assessment of small fiber neuropathy: evidence of a non-length-dependent distal axonopathy. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73(6):684–690. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0057

Peripheral neuropathy is the most common reason for an outpatient neurology visit in the United States and accounts for over $10 billion in healthcare spending each year.1,2 When the disorder affects only small, thinly myelinated or unmyelinated nerve fibers, it is referred to as small fiber neuropathy, which commonly presents as numbness and burning pain in the feet.

This article details the manifestations and evaluation of small fiber neuropathy, with an eye toward diagnosing an underlying cause amenable to treatment.

OLDER PATIENTS MOST AFFECTED

The epidemiology of small fiber neuropathy is not well established. It occurs more commonly in older patients, but data are mixed on prevalence by sex.3–6 In a Dutch study,3 the overall prevalence was at least 53 cases per 100,000, with the highest rate in men over age 65.

CHARACTERISTIC SENSORY DISTURBANCES

Sensations vary in quality and time

Patients with small fiber neuropathy typically present with a symmetric length-dependent (“stocking-glove”) distribution of sensory changes, starting in the feet and gradually ascending up the legs and then to the hands.

Commonly reported neuropathic symptoms include various combinations of burning, numbness, tingling, itching, sunburn-like, and frostbite-like sensations. Nonneuropathic symptoms may include tightness, a vise-like squeezing of the feet, and the sensation of a sock rolled up at the end of the shoe. Cramps or spasms may also be reported but rarely occur in isolation.7

Symptoms are typically worse at the end of the day and while sitting or lying down at night. They can arise spontaneously but may also be triggered by something as minor as the touch of clothing or cool air against the skin. Bedsheet sensitivity of the feet is reported so often that it is used as an outcome measure in clinical trials. Symptoms can also be exacerbated by extremes in ambient temperature and are especially worse in cold weather.

Random patterns suggest an immune cause

Symptoms may also have a non–length-dependent distribution that is asymmetric, patchy, intermittent, and migratory, and can involve the face, proximal limbs, and trunk. Symptoms may vary throughout the day, eg, starting with electric-shock sensations on one side of the face, followed by perineal numbness and then tingling in the arms lasting for a few minutes to several hours. While such patterns may be seen with diabetes and other common etiologies, they often suggest an underlying immune-mediated disorder such as Sjögren syndrome or sarcoidosis.8–10 Although large fiber polyneuropathy may also be non–length-dependent, the deficits are usually fixed, with no migratory component.

Autonomic features may be prominent

Autonomic symptoms occur in nearly half of patients and can be as troublesome as neuropathic pain.3 Small nerve fibers mediate somatic and autonomic functions, an evolutionary link that may reflect visceral defense mechanisms responding to pain as a signal of danger.11 This may help explain the multisystemic nature of symptoms, which can include sweating abnormalities, bowel and bladder disturbances, dry eyes, dry mouth, gastrointestinal dysmotility, skin changes (eg, discoloration, loss of hair, shiny skin), sexual dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and palpitations. In some cases, isolated dysautonomia may be seen.

TARGETED EXAMINATION

History: Medications, alcohol, infections

When a patient presents with neuropathic pain in the feet, a detailed history should be obtained, including alcohol use, family history of neuropathy, and use of neurotoxic medications such as metronidazole, colchicine, and chemotherapeutic agents.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C infection are well known to be associated with small fiber neuropathy, so relevant risk factors (eg, blood transfusions, sexual history, intravenous drug use) should be asked about. Recent illnesses and vaccinations are another important line of questioning, as a small-fiber variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome has been described.12

Assess reflexes, strength, sensation

On physical examination, particular attention should be focused on searching for abnormalities indicating large nerve fiber involvement (eg, absent deep tendon reflexes, weakness of the toes). However, absent ankle deep tendon reflexes and reduced vibratory sense may also occur in healthy elderly people.

Similarly, proprioception, motor strength, balance, and vibratory sensation are functions of large myelinated nerve fibers, and thus remain unaffected in patients with only small fiber neuropathy.

Evidence of a systemic disorder should also be sought, as it may indicate an underlying etiology.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Although patients with either large or small fiber neuropathy may have subjective hyperesthesia or numbness of the distal lower extremities, the absence of significant abnormalities on neurologic examination should prompt consideration of small fiber neuropathy.

Electromyography worthwhile

Nerve conduction studies and needle electrode examination evaluate only large nerve fiber conditions. While electromyographic results are normal in patients with isolated small fiber neuropathy, the test can help evaluate subclinical large nerve fiber involvement and alternative diagnoses such as bilateral S1 radiculopathy. Nerve conduction studies may be less useful in patients over age 75, as they may lack sural sensory responses because of aging changes.13

Skin biopsy easy to do

Skin biopsy for evaluating intraepidermal nerve fiber density is one of the most widely used tests for small fiber neuropathy. This minimally invasive procedure can now be performed in a primary care office using readily available tools or prepackaged kits and analyzed by several commercial laboratories.

Reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density on skin biopsy has been described in various other conditions such as fibromyalgia and chronic pain syndromes.16,17 The clinical significance of these findings remains uncertain.

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing (QSART) is a noninvasive autonomic study that assesses the volume of sweat produced by the limbs in response to acetylcholine. A measure of postganglionic sympathetic sudomotor nerve function, QSART has a sensitivity of up to 80% and can be used to diagnose small fiber neuropathy.18 In a series of 115 patients with sarcoidosis small fiber neuropathy,9 the QSART and skin biopsy findings were concordant in 17 cases and complementary in 29, allowing for confirmation of small fiber neuropathy in patients whose condition would have remained undiagnosed had only one test been performed. QSART can also be considered in cases where skin biopsy may be contraindicated (eg, patient use of anticoagulation). Of note, the study may be affected by a number of external factors, including caffeine, tobacco, antihistamines, and tricyclic antidepressants; these should be held before testing.

Other diagnostic studies

Other tests may be helpful, as follows:

Tilt-table and cardiovagal testing may be useful for patients with orthostasis and palpitations.

Thermoregulatory sweat testing can be used to evaluate patients with abnormal patterns of sweating, eg, hyperhidrosis of the face and head.

INITIAL TESTING FOR AN UNDERLYING CAUSE

Glucose tolerance test for diabetes

Diabetes is the most common identifiable cause of small fiber neuropathy and accounts for about a third of all cases.5 Impaired glucose tolerance is also thought to be a risk factor and has been found in up to 50% of idiopathic cases, but the association is still being debated.21

While testing for hemoglobin A1c is more convenient for the patient, especially because it does not require fasting, a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test is more sensitive for detecting glucose dysmetabolism.22

Lipid panel for metabolic syndrome

Small fiber neuropathy is associated with individual components of the metabolic syndrome, which include obesity, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Of these, dyslipidemia has emerged as the primary factor involved in the development of small fiber neuropathy, via an inflammatory pathway or oxidative stress mechanism.23,24

Vitamin B12 deficiency testing

Vitamin B12 deficiency, a potentially correctable cause of small fiber neuropathy, may be underdiagnosed, especially as values obtained by blood testing may not reflect tissue uptake. Causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include reduced intake, pernicious anemia, and medications that can affect absorption of vitamin B12 (eg, proton pump inhibitors, histamine 2 receptor antagonists, metformin).

Testing should include:

- Complete blood cell count to evaluate for vitamin B12-related macrocytic anemia and other hematologic abnormalities

- Serum vitamin B12 level

- Methylmalonic acid or homocysteine level in patients with subclinical or mild vitamin B12 deficiency, manifested as low to normal vitamin B12 levels (< 400 pg/mL); methylmalonic acid and homocysteine require vitamin B12 as a cofactor for enzymatic conversion, and either or both may be elevated in early vitamin B12 deficiency.

Celiac antibody panel

Celiac disease, a T-cell mediated enteropathy characterized by gluten intolerance and a herpetiform-like rash, can be associated with small fiber neuropathy.25 In some cases, neuropathy symptoms are preceded by the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms, or they may occur in isolation.25

Inflammatory disease testing

Sjögren syndrome accounts for nearly 10% of cases of small fiber neuropathy. Associated neuropathic symptoms are often non–length-dependent, can precede sicca symptoms for up to 6 years, and in some cases are the sole manifestation of the disease.10 Small fiber neuropathy may also be associated with vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue disorders.

Testing should include:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and antinuclear antibodies: though these are nonspecific markers of inflammation, they may support an immune-mediated etiology if positive

- Extractable nuclear antigen panel: Sjögren syndrome A and B autoantibodies are the most important components in this setting5,11

- The Schirmer test or salivary gland biopsy should be considered for seronegative patients with sicca or a suspected immune-mediated etiology, as the sensitivity of antibody testing ranges from only 10% to 55%.10

Thyroid function testing

Hypothyroidism, and less commonly hyperthyroidism, are associated with small fiber neuropathy.

Metabolic tests for liver and kidney disease

Renal insufficiency and liver impairment are well-known causes of small nerve fiber dysfunction. Testing should include:

- Comprehensive metabolic panel

- Gamma-glutamyltransferase if alcohol abuse is suspected, since heavy alcohol use is one of the most common causes of both large and small fiber neuropathy.

HIV and hepatitis C testing

For patients with relevant risk factors, HIV and hepatitis C testing should be part of the initial workup (and as second-tier testing for others). Patients who test positive for hepatitis C should undergo further testing for cryoglobulinemia, which can present with painful small fiber neuropathy.26

Serum and urine immunoelectrophoresis

Paraproteinemia, with causes ranging from monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance to multiple myeloma, has been associated with small fiber neuropathy. An abnormal serum or urine immunoelectrophoresis test warrants further investigation and possibly referral to a hematology-oncology specialist.

SECOND-TIER TESTING

Less common treatable causes of small fiber neuropathy may also be evaluated.

Copper, vitamin B1 (thiamine), or vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency testing. Although vitamin B6 toxicity may also result in neuropathy due to its toxic effect on the dorsal root ganglia, the mildly elevated vitamin B6 levels often found in patients being evaluated for neuropathy are unlikely to be the primary cause of symptoms. Many laboratories require fasting samples for accurate vitamin B6 levels.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels for sarcoidosis. Small fiber neuropathy is common in sarcoidosis, occurring in more than 30% of patients with systemic disease.27 However, screening for sarcoidosis by measuring serum levels is often falsely positive and is not cost-effective. In a study of 195 patients with idiopathic small fiber neuropathy,11 44% had an elevated serum level, but no evidence of sarcoidosis was seen on further testing, which included computed tomography of the chest in 29 patients.12 Thus, this test is best used for patients with evidence of systemic disease.

Amyloid testing for amyloidosis. Fat pad or bone marrow biopsy should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

Paraneoplastic autoantibody panel for occult cancer. Such testing may also be considered if clinically warranted. However, if a patient is found to have low positive titers of paraneoplastic antibodies and suspicion is low for an occult cancer (eg, no weight loss or early satiety), repeat confirmatory testing at another laboratory should be done before embarking on an extensive search for malignancy.

Ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody testing for autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. This should be ordered for patients with prominent autonomic dysfunction. The antibody test can be ordered separately or as part of an autoantibody panel. The antibody may indicate a primary immune-mediated process or a paraneoplastic disease.28

Genetic mutation testing. Recent discoveries of gene mutations leading to peripheral nerve hyperexcitability of voltage-gated sodium channels have elucidated a hereditary cause of small fiber neuropathy in nearly 30% of cases that were once thought to be idiopathic.29,30 Genetic testing for mutations in SCN9A and SCN10 (which code for the Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 sodium channels, respectively) is commercially available and may be considered for those with a family history of neuropathic pain in the feet or for young, otherwise healthy patients.

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal disorder characterized by angiokeratomas, cardiac and renal impairment, and small fiber neuropathy. Treatment is now available, but screening is not cost-efficient and should only be pursued in patients with other symptoms of the disease.31,32

OTHER POSSIBLE CAUSES

Guillain-Barré syndrome

A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant has been reported that is characterized by ascending limb paresthesias and cerebrospinal fluid albuminocytologic dissociation in the setting of preserved deep tendon reflexes and normal findings on EMG.12 The clinical course is similar to that of typical Guillain-Barré syndrome, in that symptoms follow an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, reach their nadir at 4 weeks, and then gradually improve. Some patients respond to intravenous immune globulin.

Vaccine-associated

Postvaccination small fiber neuropathy has also been reported. The nature of the association is unclear.33

Parkinson disease

Small fiber neuropathy is associated with Parkinson disease. It is attributed to a number of proposed factors, including neurodegeneration that occurs parallel to central nervous system decline, as well as intestinal malabsorption with resultant vitamin deficiency.34,35

Rapid glycemic lowering

Aggressive treatment of diabetes, defined as at least a 2-point reduction of serum hemoglobin A1c level over 3 months, may result in acute small fiber neuropathy. It manifests as severe distal extremity pain and dysautonomia.

In a retrospective study,36 104 (10.9%) of 954 patients presenting to a tertiary diabetic clinic developed treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy with symptoms occurring within 8 weeks of rapid glycemic control. The severity of neuropathy correlated with the degree and rate of glycemic lowering. The condition was reversible in some cases.

TREATING SPECIFIC DISORDERS

For patients with an identified cause of neuropathy, targeted treatment offers the best chance of halting progression and possibly improving symptoms. Below are recommendations for addressing neuropathy associated with the common diagnoses.

Diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, and metabolic syndrome. In addition to glycemic- and lipid-lowering therapies, lifestyle modifications with a specific focus on exercise and nutrition are integral to treating diabetes and related disorders.

In the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study,37 which evaluated the effects of intensive lifestyle intervention on neuropathy in 5,145 overweight patients with type 2 diabetes, patients in the intervention group had lower pain scores and better touch sensation in the toes compared with controls at 1 year. Differences correlated with the degree of weight loss and reduction of hemoglobin A1c and lipid levels.

As running and walking may not be feasible for many patients owing to pain, stationary cycling, aqua therapy, and swimming are other options. A stationary recumbent bike may be useful for older patients with balance issues.

Vitamin B12 deficiency. As reduced absorption rather than low dietary intake is the primary cause of vitamin B12 deficiency for many patients, parenteral rather than oral supplementation may be best. A suggested regimen is subcutaneous or intramuscular methylcobalamin injection of 1,000 µg given daily for 1 week, then once weekly for 1 month, followed by a maintenance dose once a month for at least 6 to 12 months. Alternatively, a daily dose of vitamin B12 1,000 µg can be taken sublingually.

Sjögren syndrome. According to anecdotal case reports, intravenous immune globulin, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants help painful small fiber neuropathy and dysautonomia associated with Sjögren syndrome.10

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis-associated small fiber neuropathy may also respond to intravenous immune globulin, as well as infliximab and combination therapy.9 Culver et al38 found that cibinetide, an experimental erythropoetin agonist, resulted in improved corneal nerve fiber measures in patients with small fiber neuropathy associated with sarcoidosis.

Celiac disease. A gluten-free diet is the treatment for celiac disease and can help some patients.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

For all patients, regardless of whether the cause of small fiber neuropathy has been identified, managing symptoms remains key, as pain and autonomic dysfunction can markedly impair quality of life. A multidisciplinary approach that incorporates pain medications, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications is ideal. Integrative holistic treatments such as natural supplements, yoga, and other mind-body therapies may also help.

Pain control

Mexiletine, a voltage-gated sodium channel blocker used as an antiarrhythmic, may help refractory pain or hereditary small fiber neuropathy related to sodium channel dysfunction. However, it is not recommended for diabetic neuropathy.39

Combination regimens that use drugs with different mechanisms of action can be effective. In one study, combined gabapentin and nortriptyline were more effective than either drug alone for neuropathic pain.40

Inhaled cannabis reduced pain in patients with HIV and diabetic neuropathy in a number of studies. Side effects included euphoria, somnolence, and cognitive impairment.41,42 The use of medical marijuana is not yet legal nationwide and may affect employability even in states in which it has been legalized.

Owing to the opioid epidemic and high addiction potential, opioids are no longer a preferred recommendation for chronic treatment of noncancer-related neuropathy. A population-based study of 2,892 patients with neuropathy found that those on chronic opioid therapy (≥ 90 days) had worse functional outcomes and higher rates of addiction and overdose than those on short-term therapy.43 However, the opioid agonist tramadol was found to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain and may be a safer option for patients with chronic small fiber neuropathy.44

Integrative, holistic therapies

PROGNOSIS

For many patients, small fiber neuropathy is a slowly progressive disorder that reaches a clinical plateau lasting for years, with progression to large fiber involvement reported in 13% to 36% of cases; over half of patients in one series either improved or remained stable over a period of 2 years.5,57 Long-term studies are needed to fully understand the natural disease course. In the meantime, treating underlying disease and managing symptoms are imperative to patient care.

Peripheral neuropathy is the most common reason for an outpatient neurology visit in the United States and accounts for over $10 billion in healthcare spending each year.1,2 When the disorder affects only small, thinly myelinated or unmyelinated nerve fibers, it is referred to as small fiber neuropathy, which commonly presents as numbness and burning pain in the feet.

This article details the manifestations and evaluation of small fiber neuropathy, with an eye toward diagnosing an underlying cause amenable to treatment.

OLDER PATIENTS MOST AFFECTED

The epidemiology of small fiber neuropathy is not well established. It occurs more commonly in older patients, but data are mixed on prevalence by sex.3–6 In a Dutch study,3 the overall prevalence was at least 53 cases per 100,000, with the highest rate in men over age 65.

CHARACTERISTIC SENSORY DISTURBANCES

Sensations vary in quality and time

Patients with small fiber neuropathy typically present with a symmetric length-dependent (“stocking-glove”) distribution of sensory changes, starting in the feet and gradually ascending up the legs and then to the hands.

Commonly reported neuropathic symptoms include various combinations of burning, numbness, tingling, itching, sunburn-like, and frostbite-like sensations. Nonneuropathic symptoms may include tightness, a vise-like squeezing of the feet, and the sensation of a sock rolled up at the end of the shoe. Cramps or spasms may also be reported but rarely occur in isolation.7

Symptoms are typically worse at the end of the day and while sitting or lying down at night. They can arise spontaneously but may also be triggered by something as minor as the touch of clothing or cool air against the skin. Bedsheet sensitivity of the feet is reported so often that it is used as an outcome measure in clinical trials. Symptoms can also be exacerbated by extremes in ambient temperature and are especially worse in cold weather.

Random patterns suggest an immune cause

Symptoms may also have a non–length-dependent distribution that is asymmetric, patchy, intermittent, and migratory, and can involve the face, proximal limbs, and trunk. Symptoms may vary throughout the day, eg, starting with electric-shock sensations on one side of the face, followed by perineal numbness and then tingling in the arms lasting for a few minutes to several hours. While such patterns may be seen with diabetes and other common etiologies, they often suggest an underlying immune-mediated disorder such as Sjögren syndrome or sarcoidosis.8–10 Although large fiber polyneuropathy may also be non–length-dependent, the deficits are usually fixed, with no migratory component.

Autonomic features may be prominent

Autonomic symptoms occur in nearly half of patients and can be as troublesome as neuropathic pain.3 Small nerve fibers mediate somatic and autonomic functions, an evolutionary link that may reflect visceral defense mechanisms responding to pain as a signal of danger.11 This may help explain the multisystemic nature of symptoms, which can include sweating abnormalities, bowel and bladder disturbances, dry eyes, dry mouth, gastrointestinal dysmotility, skin changes (eg, discoloration, loss of hair, shiny skin), sexual dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and palpitations. In some cases, isolated dysautonomia may be seen.

TARGETED EXAMINATION

History: Medications, alcohol, infections

When a patient presents with neuropathic pain in the feet, a detailed history should be obtained, including alcohol use, family history of neuropathy, and use of neurotoxic medications such as metronidazole, colchicine, and chemotherapeutic agents.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C infection are well known to be associated with small fiber neuropathy, so relevant risk factors (eg, blood transfusions, sexual history, intravenous drug use) should be asked about. Recent illnesses and vaccinations are another important line of questioning, as a small-fiber variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome has been described.12

Assess reflexes, strength, sensation

On physical examination, particular attention should be focused on searching for abnormalities indicating large nerve fiber involvement (eg, absent deep tendon reflexes, weakness of the toes). However, absent ankle deep tendon reflexes and reduced vibratory sense may also occur in healthy elderly people.

Similarly, proprioception, motor strength, balance, and vibratory sensation are functions of large myelinated nerve fibers, and thus remain unaffected in patients with only small fiber neuropathy.

Evidence of a systemic disorder should also be sought, as it may indicate an underlying etiology.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Although patients with either large or small fiber neuropathy may have subjective hyperesthesia or numbness of the distal lower extremities, the absence of significant abnormalities on neurologic examination should prompt consideration of small fiber neuropathy.

Electromyography worthwhile

Nerve conduction studies and needle electrode examination evaluate only large nerve fiber conditions. While electromyographic results are normal in patients with isolated small fiber neuropathy, the test can help evaluate subclinical large nerve fiber involvement and alternative diagnoses such as bilateral S1 radiculopathy. Nerve conduction studies may be less useful in patients over age 75, as they may lack sural sensory responses because of aging changes.13

Skin biopsy easy to do

Skin biopsy for evaluating intraepidermal nerve fiber density is one of the most widely used tests for small fiber neuropathy. This minimally invasive procedure can now be performed in a primary care office using readily available tools or prepackaged kits and analyzed by several commercial laboratories.

Reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density on skin biopsy has been described in various other conditions such as fibromyalgia and chronic pain syndromes.16,17 The clinical significance of these findings remains uncertain.

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing (QSART) is a noninvasive autonomic study that assesses the volume of sweat produced by the limbs in response to acetylcholine. A measure of postganglionic sympathetic sudomotor nerve function, QSART has a sensitivity of up to 80% and can be used to diagnose small fiber neuropathy.18 In a series of 115 patients with sarcoidosis small fiber neuropathy,9 the QSART and skin biopsy findings were concordant in 17 cases and complementary in 29, allowing for confirmation of small fiber neuropathy in patients whose condition would have remained undiagnosed had only one test been performed. QSART can also be considered in cases where skin biopsy may be contraindicated (eg, patient use of anticoagulation). Of note, the study may be affected by a number of external factors, including caffeine, tobacco, antihistamines, and tricyclic antidepressants; these should be held before testing.

Other diagnostic studies

Other tests may be helpful, as follows:

Tilt-table and cardiovagal testing may be useful for patients with orthostasis and palpitations.

Thermoregulatory sweat testing can be used to evaluate patients with abnormal patterns of sweating, eg, hyperhidrosis of the face and head.

INITIAL TESTING FOR AN UNDERLYING CAUSE

Glucose tolerance test for diabetes

Diabetes is the most common identifiable cause of small fiber neuropathy and accounts for about a third of all cases.5 Impaired glucose tolerance is also thought to be a risk factor and has been found in up to 50% of idiopathic cases, but the association is still being debated.21

While testing for hemoglobin A1c is more convenient for the patient, especially because it does not require fasting, a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test is more sensitive for detecting glucose dysmetabolism.22

Lipid panel for metabolic syndrome

Small fiber neuropathy is associated with individual components of the metabolic syndrome, which include obesity, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Of these, dyslipidemia has emerged as the primary factor involved in the development of small fiber neuropathy, via an inflammatory pathway or oxidative stress mechanism.23,24

Vitamin B12 deficiency testing

Vitamin B12 deficiency, a potentially correctable cause of small fiber neuropathy, may be underdiagnosed, especially as values obtained by blood testing may not reflect tissue uptake. Causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include reduced intake, pernicious anemia, and medications that can affect absorption of vitamin B12 (eg, proton pump inhibitors, histamine 2 receptor antagonists, metformin).

Testing should include:

- Complete blood cell count to evaluate for vitamin B12-related macrocytic anemia and other hematologic abnormalities

- Serum vitamin B12 level

- Methylmalonic acid or homocysteine level in patients with subclinical or mild vitamin B12 deficiency, manifested as low to normal vitamin B12 levels (< 400 pg/mL); methylmalonic acid and homocysteine require vitamin B12 as a cofactor for enzymatic conversion, and either or both may be elevated in early vitamin B12 deficiency.

Celiac antibody panel

Celiac disease, a T-cell mediated enteropathy characterized by gluten intolerance and a herpetiform-like rash, can be associated with small fiber neuropathy.25 In some cases, neuropathy symptoms are preceded by the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms, or they may occur in isolation.25

Inflammatory disease testing

Sjögren syndrome accounts for nearly 10% of cases of small fiber neuropathy. Associated neuropathic symptoms are often non–length-dependent, can precede sicca symptoms for up to 6 years, and in some cases are the sole manifestation of the disease.10 Small fiber neuropathy may also be associated with vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue disorders.

Testing should include:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and antinuclear antibodies: though these are nonspecific markers of inflammation, they may support an immune-mediated etiology if positive

- Extractable nuclear antigen panel: Sjögren syndrome A and B autoantibodies are the most important components in this setting5,11

- The Schirmer test or salivary gland biopsy should be considered for seronegative patients with sicca or a suspected immune-mediated etiology, as the sensitivity of antibody testing ranges from only 10% to 55%.10

Thyroid function testing

Hypothyroidism, and less commonly hyperthyroidism, are associated with small fiber neuropathy.

Metabolic tests for liver and kidney disease

Renal insufficiency and liver impairment are well-known causes of small nerve fiber dysfunction. Testing should include:

- Comprehensive metabolic panel

- Gamma-glutamyltransferase if alcohol abuse is suspected, since heavy alcohol use is one of the most common causes of both large and small fiber neuropathy.

HIV and hepatitis C testing

For patients with relevant risk factors, HIV and hepatitis C testing should be part of the initial workup (and as second-tier testing for others). Patients who test positive for hepatitis C should undergo further testing for cryoglobulinemia, which can present with painful small fiber neuropathy.26

Serum and urine immunoelectrophoresis

Paraproteinemia, with causes ranging from monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance to multiple myeloma, has been associated with small fiber neuropathy. An abnormal serum or urine immunoelectrophoresis test warrants further investigation and possibly referral to a hematology-oncology specialist.

SECOND-TIER TESTING

Less common treatable causes of small fiber neuropathy may also be evaluated.

Copper, vitamin B1 (thiamine), or vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency testing. Although vitamin B6 toxicity may also result in neuropathy due to its toxic effect on the dorsal root ganglia, the mildly elevated vitamin B6 levels often found in patients being evaluated for neuropathy are unlikely to be the primary cause of symptoms. Many laboratories require fasting samples for accurate vitamin B6 levels.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels for sarcoidosis. Small fiber neuropathy is common in sarcoidosis, occurring in more than 30% of patients with systemic disease.27 However, screening for sarcoidosis by measuring serum levels is often falsely positive and is not cost-effective. In a study of 195 patients with idiopathic small fiber neuropathy,11 44% had an elevated serum level, but no evidence of sarcoidosis was seen on further testing, which included computed tomography of the chest in 29 patients.12 Thus, this test is best used for patients with evidence of systemic disease.

Amyloid testing for amyloidosis. Fat pad or bone marrow biopsy should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

Paraneoplastic autoantibody panel for occult cancer. Such testing may also be considered if clinically warranted. However, if a patient is found to have low positive titers of paraneoplastic antibodies and suspicion is low for an occult cancer (eg, no weight loss or early satiety), repeat confirmatory testing at another laboratory should be done before embarking on an extensive search for malignancy.

Ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody testing for autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy. This should be ordered for patients with prominent autonomic dysfunction. The antibody test can be ordered separately or as part of an autoantibody panel. The antibody may indicate a primary immune-mediated process or a paraneoplastic disease.28

Genetic mutation testing. Recent discoveries of gene mutations leading to peripheral nerve hyperexcitability of voltage-gated sodium channels have elucidated a hereditary cause of small fiber neuropathy in nearly 30% of cases that were once thought to be idiopathic.29,30 Genetic testing for mutations in SCN9A and SCN10 (which code for the Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 sodium channels, respectively) is commercially available and may be considered for those with a family history of neuropathic pain in the feet or for young, otherwise healthy patients.

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal disorder characterized by angiokeratomas, cardiac and renal impairment, and small fiber neuropathy. Treatment is now available, but screening is not cost-efficient and should only be pursued in patients with other symptoms of the disease.31,32

OTHER POSSIBLE CAUSES

Guillain-Barré syndrome

A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant has been reported that is characterized by ascending limb paresthesias and cerebrospinal fluid albuminocytologic dissociation in the setting of preserved deep tendon reflexes and normal findings on EMG.12 The clinical course is similar to that of typical Guillain-Barré syndrome, in that symptoms follow an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, reach their nadir at 4 weeks, and then gradually improve. Some patients respond to intravenous immune globulin.

Vaccine-associated

Postvaccination small fiber neuropathy has also been reported. The nature of the association is unclear.33

Parkinson disease

Small fiber neuropathy is associated with Parkinson disease. It is attributed to a number of proposed factors, including neurodegeneration that occurs parallel to central nervous system decline, as well as intestinal malabsorption with resultant vitamin deficiency.34,35

Rapid glycemic lowering

Aggressive treatment of diabetes, defined as at least a 2-point reduction of serum hemoglobin A1c level over 3 months, may result in acute small fiber neuropathy. It manifests as severe distal extremity pain and dysautonomia.

In a retrospective study,36 104 (10.9%) of 954 patients presenting to a tertiary diabetic clinic developed treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy with symptoms occurring within 8 weeks of rapid glycemic control. The severity of neuropathy correlated with the degree and rate of glycemic lowering. The condition was reversible in some cases.

TREATING SPECIFIC DISORDERS

For patients with an identified cause of neuropathy, targeted treatment offers the best chance of halting progression and possibly improving symptoms. Below are recommendations for addressing neuropathy associated with the common diagnoses.

Diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, and metabolic syndrome. In addition to glycemic- and lipid-lowering therapies, lifestyle modifications with a specific focus on exercise and nutrition are integral to treating diabetes and related disorders.

In the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study,37 which evaluated the effects of intensive lifestyle intervention on neuropathy in 5,145 overweight patients with type 2 diabetes, patients in the intervention group had lower pain scores and better touch sensation in the toes compared with controls at 1 year. Differences correlated with the degree of weight loss and reduction of hemoglobin A1c and lipid levels.

As running and walking may not be feasible for many patients owing to pain, stationary cycling, aqua therapy, and swimming are other options. A stationary recumbent bike may be useful for older patients with balance issues.

Vitamin B12 deficiency. As reduced absorption rather than low dietary intake is the primary cause of vitamin B12 deficiency for many patients, parenteral rather than oral supplementation may be best. A suggested regimen is subcutaneous or intramuscular methylcobalamin injection of 1,000 µg given daily for 1 week, then once weekly for 1 month, followed by a maintenance dose once a month for at least 6 to 12 months. Alternatively, a daily dose of vitamin B12 1,000 µg can be taken sublingually.

Sjögren syndrome. According to anecdotal case reports, intravenous immune globulin, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants help painful small fiber neuropathy and dysautonomia associated with Sjögren syndrome.10

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis-associated small fiber neuropathy may also respond to intravenous immune globulin, as well as infliximab and combination therapy.9 Culver et al38 found that cibinetide, an experimental erythropoetin agonist, resulted in improved corneal nerve fiber measures in patients with small fiber neuropathy associated with sarcoidosis.

Celiac disease. A gluten-free diet is the treatment for celiac disease and can help some patients.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

For all patients, regardless of whether the cause of small fiber neuropathy has been identified, managing symptoms remains key, as pain and autonomic dysfunction can markedly impair quality of life. A multidisciplinary approach that incorporates pain medications, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications is ideal. Integrative holistic treatments such as natural supplements, yoga, and other mind-body therapies may also help.

Pain control

Mexiletine, a voltage-gated sodium channel blocker used as an antiarrhythmic, may help refractory pain or hereditary small fiber neuropathy related to sodium channel dysfunction. However, it is not recommended for diabetic neuropathy.39

Combination regimens that use drugs with different mechanisms of action can be effective. In one study, combined gabapentin and nortriptyline were more effective than either drug alone for neuropathic pain.40

Inhaled cannabis reduced pain in patients with HIV and diabetic neuropathy in a number of studies. Side effects included euphoria, somnolence, and cognitive impairment.41,42 The use of medical marijuana is not yet legal nationwide and may affect employability even in states in which it has been legalized.

Owing to the opioid epidemic and high addiction potential, opioids are no longer a preferred recommendation for chronic treatment of noncancer-related neuropathy. A population-based study of 2,892 patients with neuropathy found that those on chronic opioid therapy (≥ 90 days) had worse functional outcomes and higher rates of addiction and overdose than those on short-term therapy.43 However, the opioid agonist tramadol was found to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain and may be a safer option for patients with chronic small fiber neuropathy.44

Integrative, holistic therapies

PROGNOSIS

For many patients, small fiber neuropathy is a slowly progressive disorder that reaches a clinical plateau lasting for years, with progression to large fiber involvement reported in 13% to 36% of cases; over half of patients in one series either improved or remained stable over a period of 2 years.5,57 Long-term studies are needed to fully understand the natural disease course. In the meantime, treating underlying disease and managing symptoms are imperative to patient care.

- Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Callaghan BC, Kerber KA. Choosing Wisely: highest-cost tests in outpatient neurology. Ann Neurol 2013; 73(5):679–683. doi:10.1002/ana.23865

- Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, Oglesby A, Tobian JA. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the US. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(6):1790–1795. pmid:12766111

- Peters MJ, Bakkers M, Merkies IS, Hoeijmakers JG, van Raak EP, Faber CG. Incidence and prevalence of small-fiber neuropathy: a survey in the Netherlands. Neurology 2013; 81(15):1356–1360. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a8236e

- Periquet MI, Novak V, Collins MP, et al. Painful sensory neuropathy: prospective evaluation using skin biopsy. Neurology 1999; 53(8):1641–1647. pmid:10563606

- Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain 2008; 131(pt 7):1912–1925. doi:10.1093/brain/awn093

- Lacomis D. Small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2002; 26(2):173–188. doi:10.1002/mus.10181

- Lopate G, Streif E, Harms M, Weihl C, Pestronk A. Cramps and small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2013; 48(2):252–255. doi:10.1002/mus.23757

- Khan S, Zhou L. Characterization of non-length-dependent small-fiber sensory neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2012; 45(1):86–91. doi:10.1002/mus.22255

- Tavee JO, Karwa K, Ahmed Z, Thompson N, Parambil J, Culver DA. Sarcoidosis-associated small fiber neuropathy in a large cohort: clinical aspects and response to IVIG and anti-TNF alpha treatment. Respir Med 2017; 126:135–138. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.03.011

- Berkowitz AL, Samuels MA. The neurology of Sjogren’s syndrome and the rheumatology of peripheral neuropathy and myelitis. Pract Neurol 2014; 14(1):14–22. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2013-000651

- Lang M, Treister R, Oaklander AL. Diagnostic value of blood tests for occult causes of initially idiopathic small-fiber polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2016; 263(12):2515–2527. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8270-5

- Seneviratne U, Gunasekera S. Acute small fibre sensory neuropathy: another variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72(4):540–542. pmid:11909922

- Tavee JO, Polston D, Zhou L, Shields RW, Butler RS, Levin KH. Sural sensory nerve action potential, epidermal nerve fiber density, and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex in the healthy elderly. Muscle Nerve 2014; 49(4):564–569. doi:10.1002/mus.23971

- Tavee J, Zhou L. Small fiber neuropathy: a burning problem. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76(5):297–305. doi:10.3949/ccjm.76a.08070

- Herrmann DN, Griffin JW, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, McArthur JC. Epidermal nerve fiber density and sural nerve morphometry in peripheral neuropathies. Neurology 1999; 53(8):1634–1640. pmid:10563605

- Oaklander AL, Herzog ZD, Downs HM, Klein MM. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain 2013; 154(11):2310–2316. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.001

- Üçeyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain 2013; 136(pt 6):1857–1867. doi:10.1093/brain/awt053

- Stewart JD, Low PA, Fealey RD. Distal small fiber neuropathy: results of tests of sweating and autonomic cardiovascular reflexes. Muscle Nerve 1992; 15(6):661–665. doi:10.1002/mus.880150605